Active Battery Balancing System for High Capacity Li-Ion Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A high-current active balancing topology suitable for large-capacity battery packs is proposed, enabling efficient energy redistribution among multiple cells.

- (2)

- A control-oriented model and dual closed-loop control strategy for the balancing circuit are established to enhance system dynamic response and control accuracy.

- (3)

- A hybrid balancing mechanism is introduced to improve system safety and versatility while maintaining high energy efficiency.

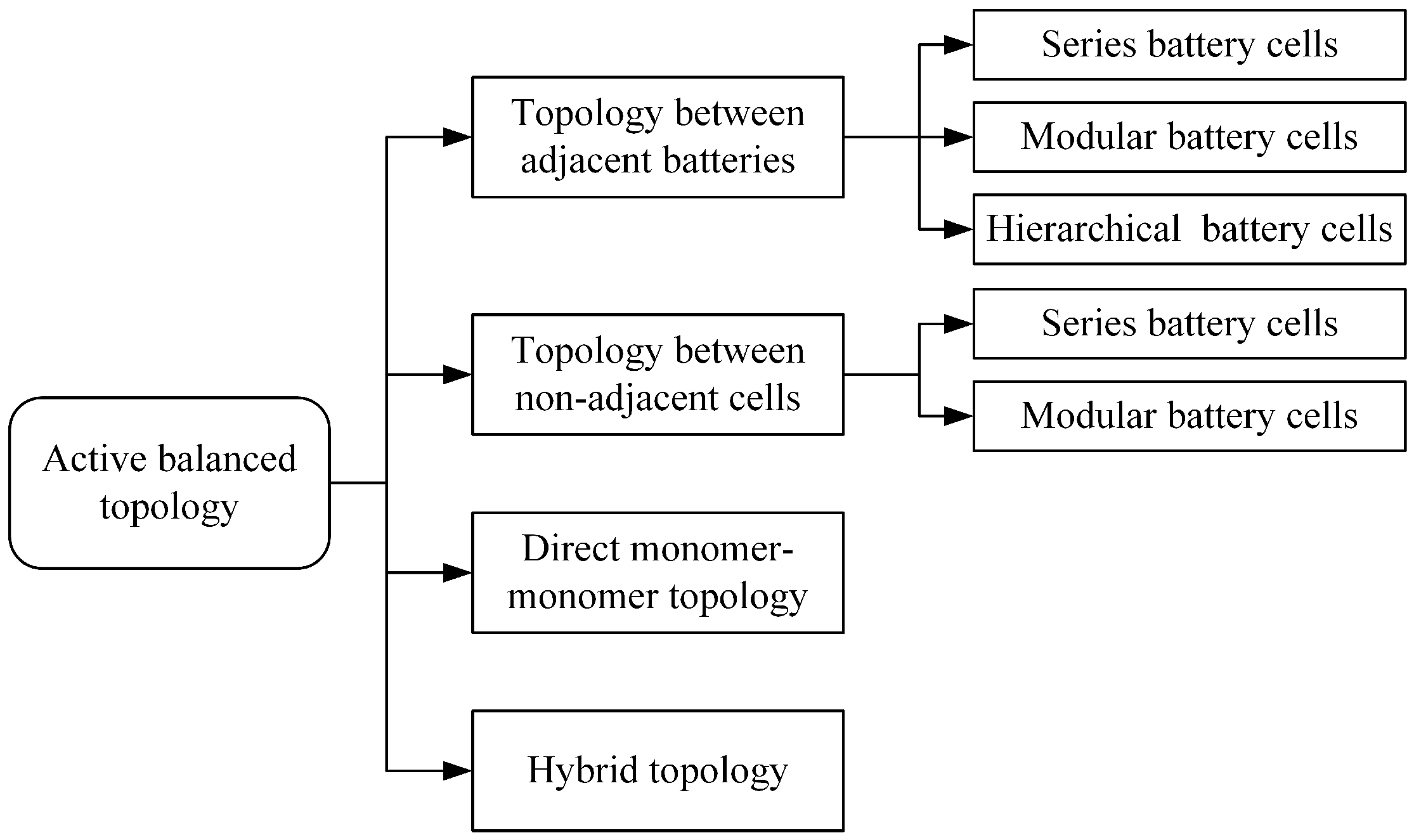

2. Design of Lithium Battery Balancing Circuit Topology

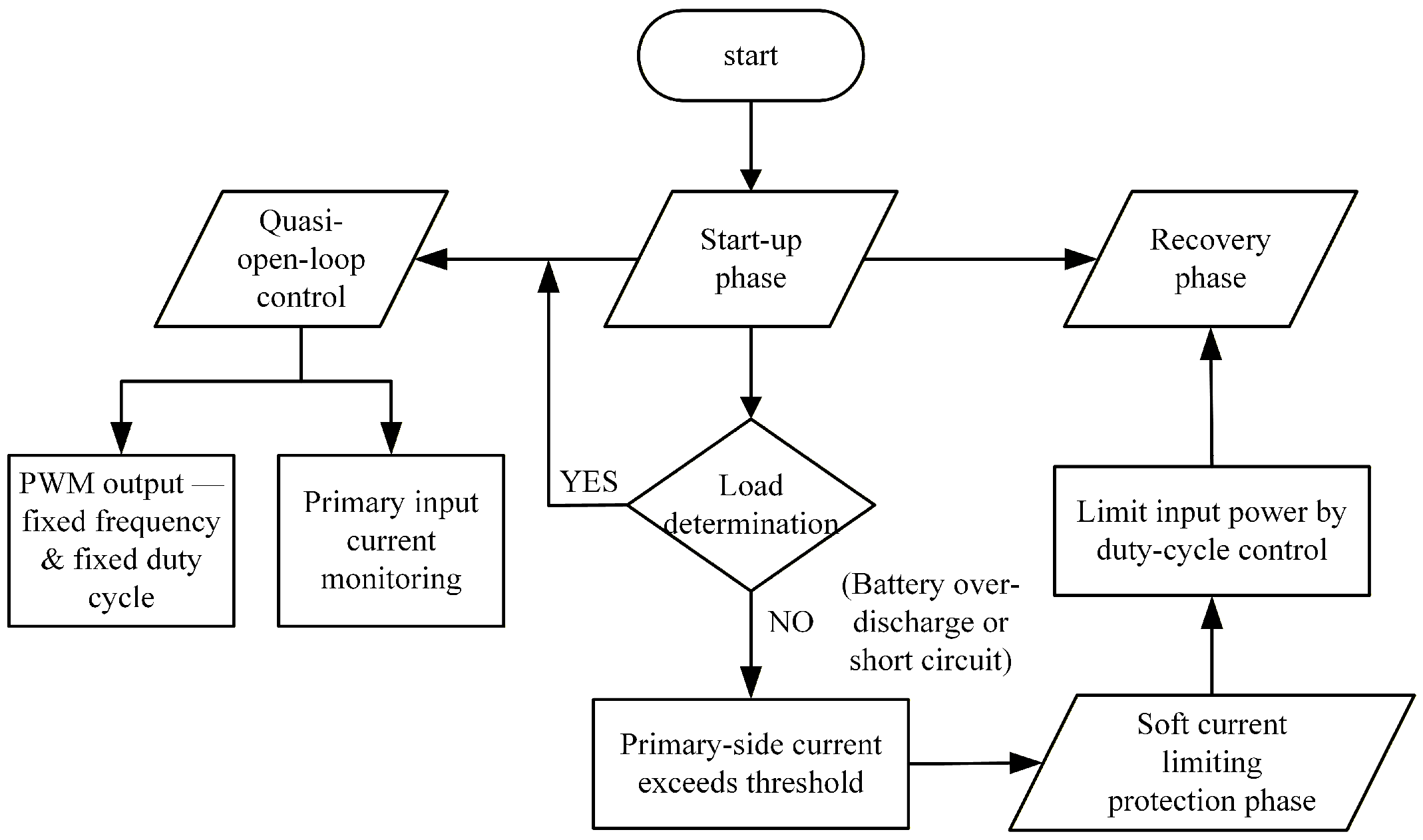

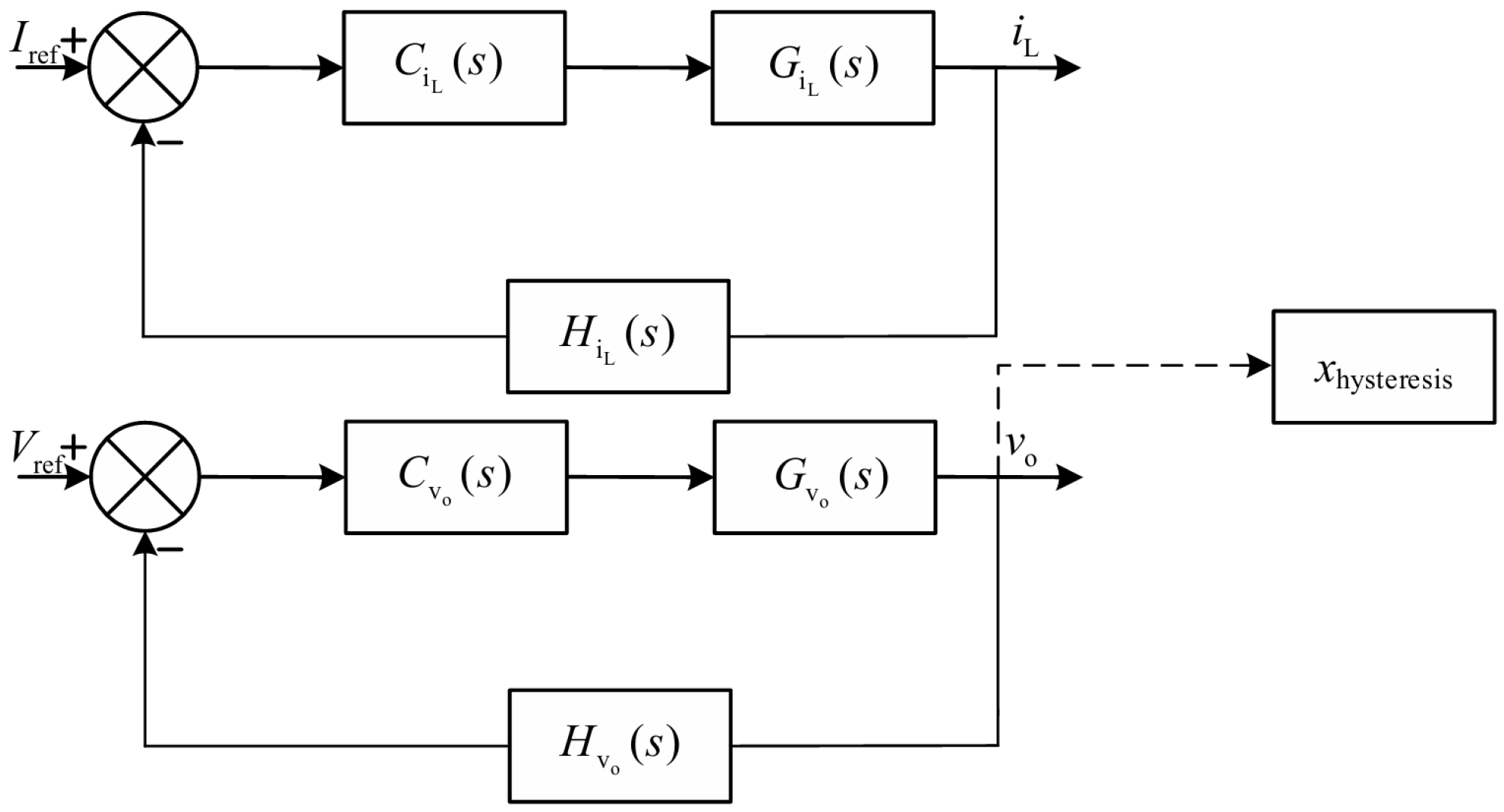

3. Modeling and Control Strategies of Balancing Circuits

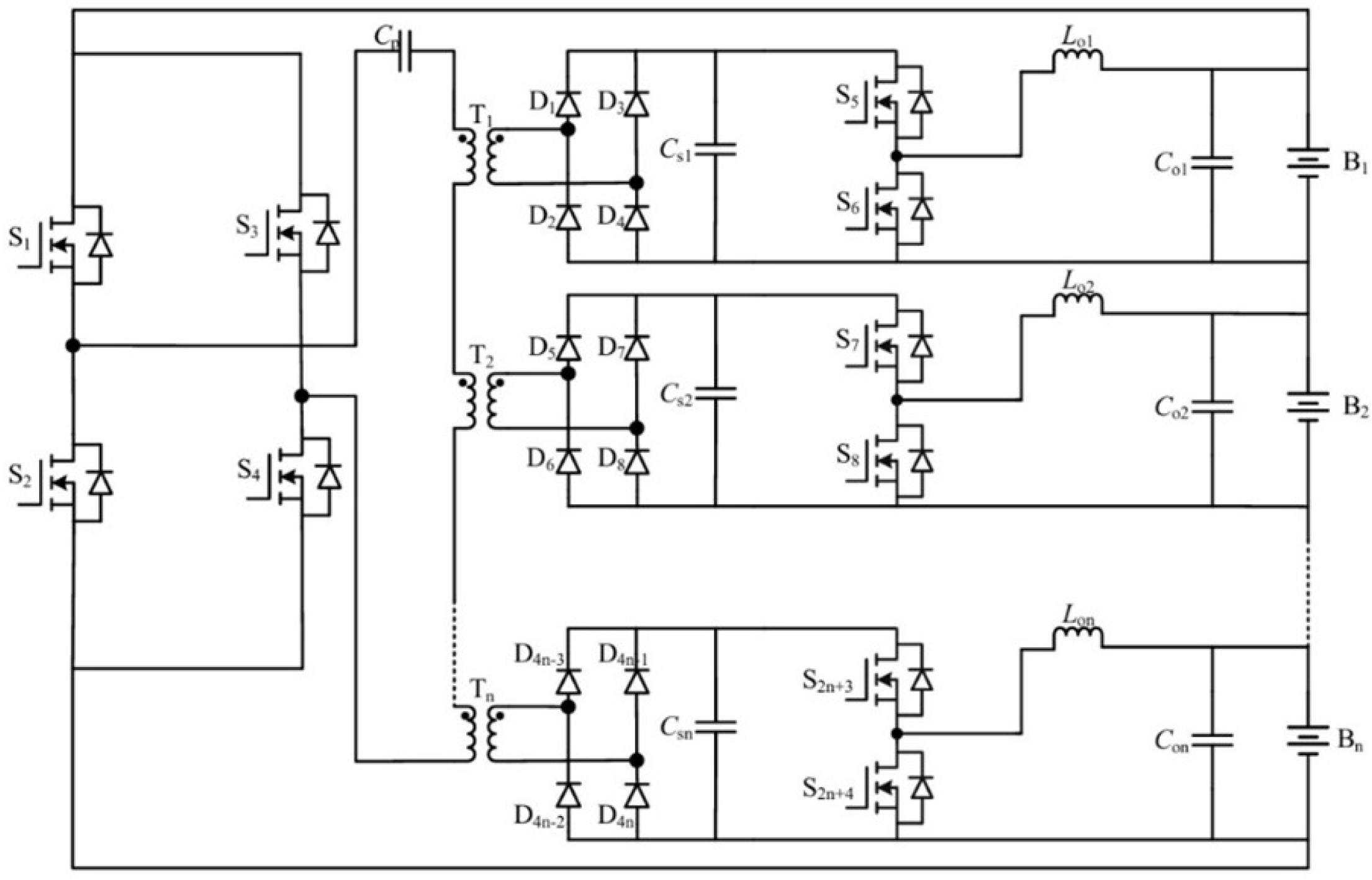

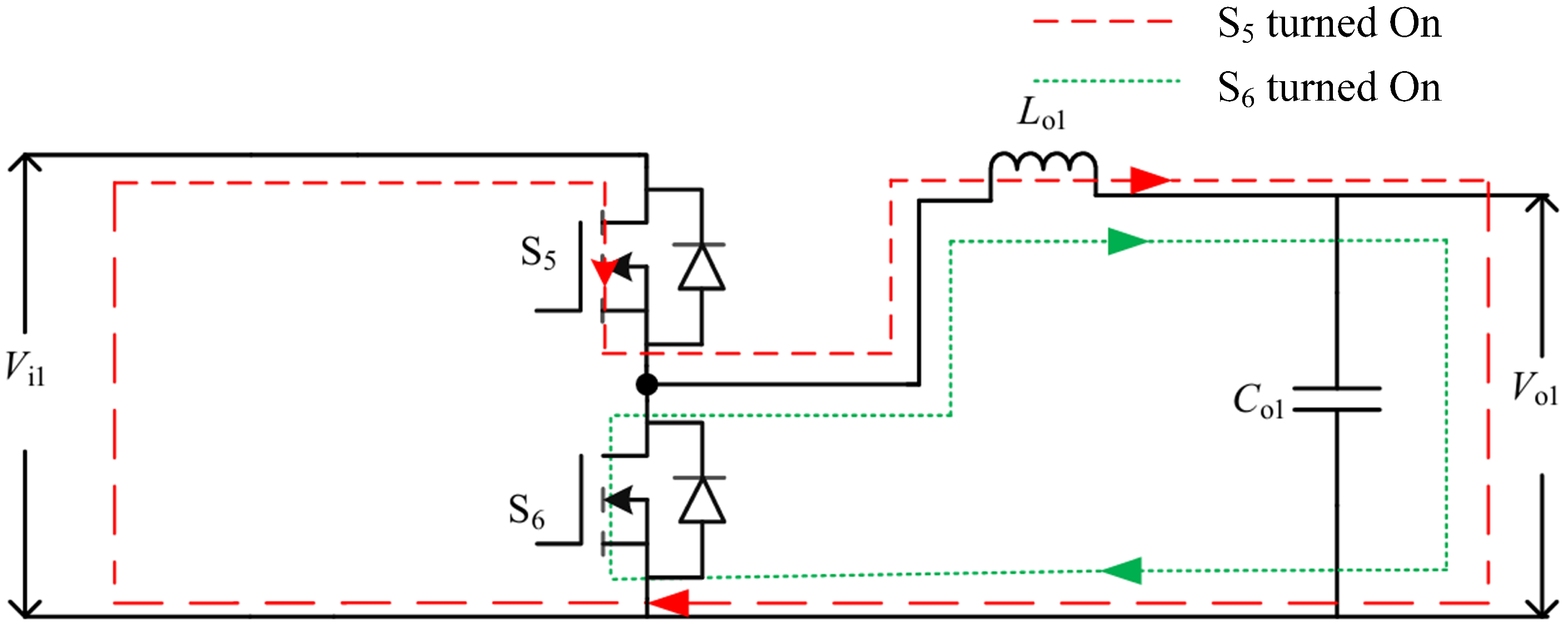

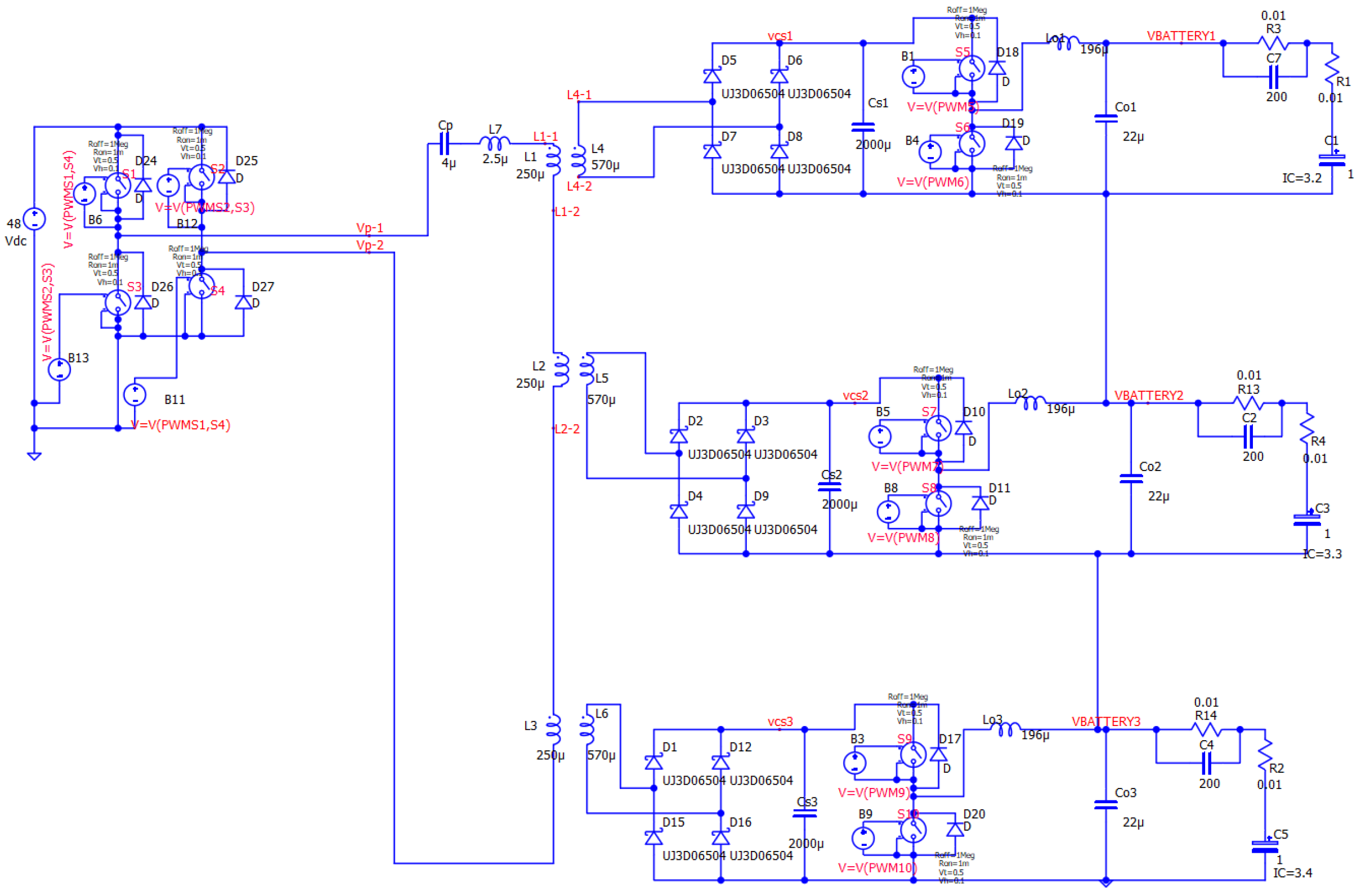

3.1. SIMO Active Balancing Topology

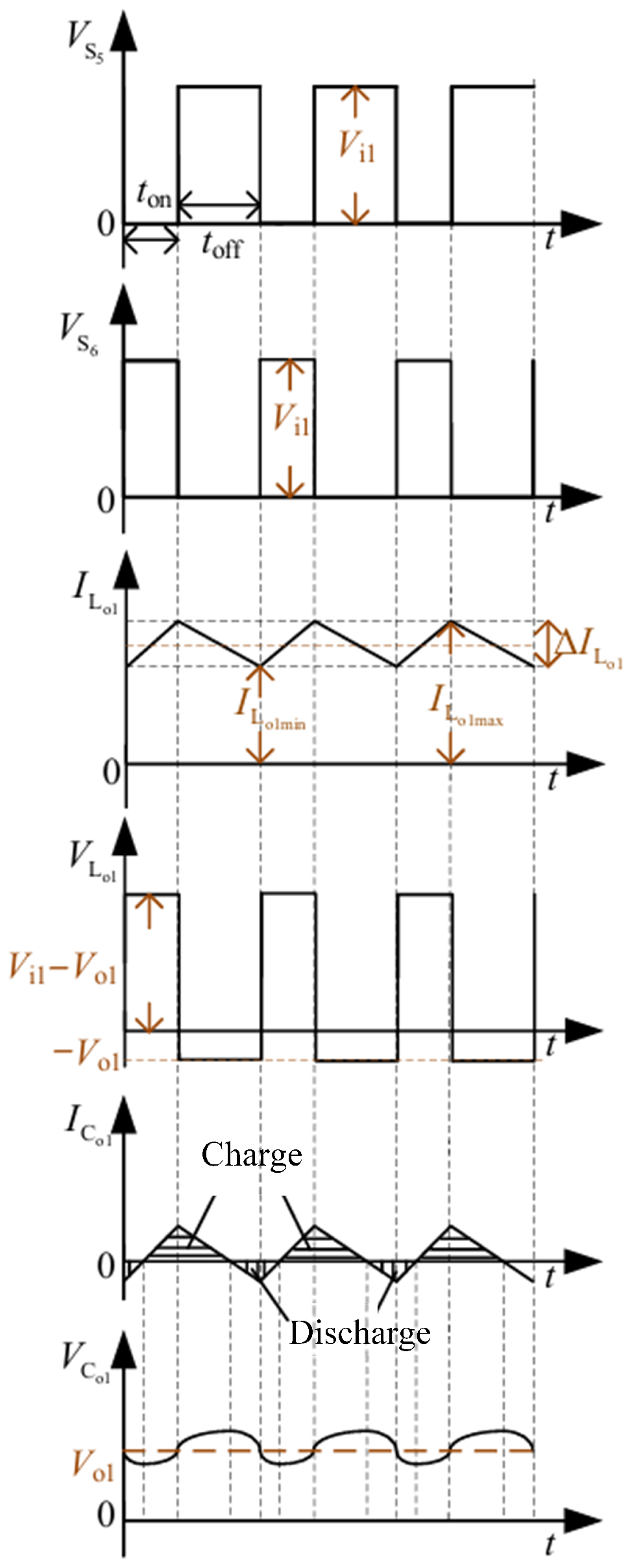

3.2. Small-Signal Modeling of Active Balancing Circuits

3.3. Control Design of Active Balancing System

4. System Simulation Verification and Analysis

4.1. Simulation Model Development and System Design

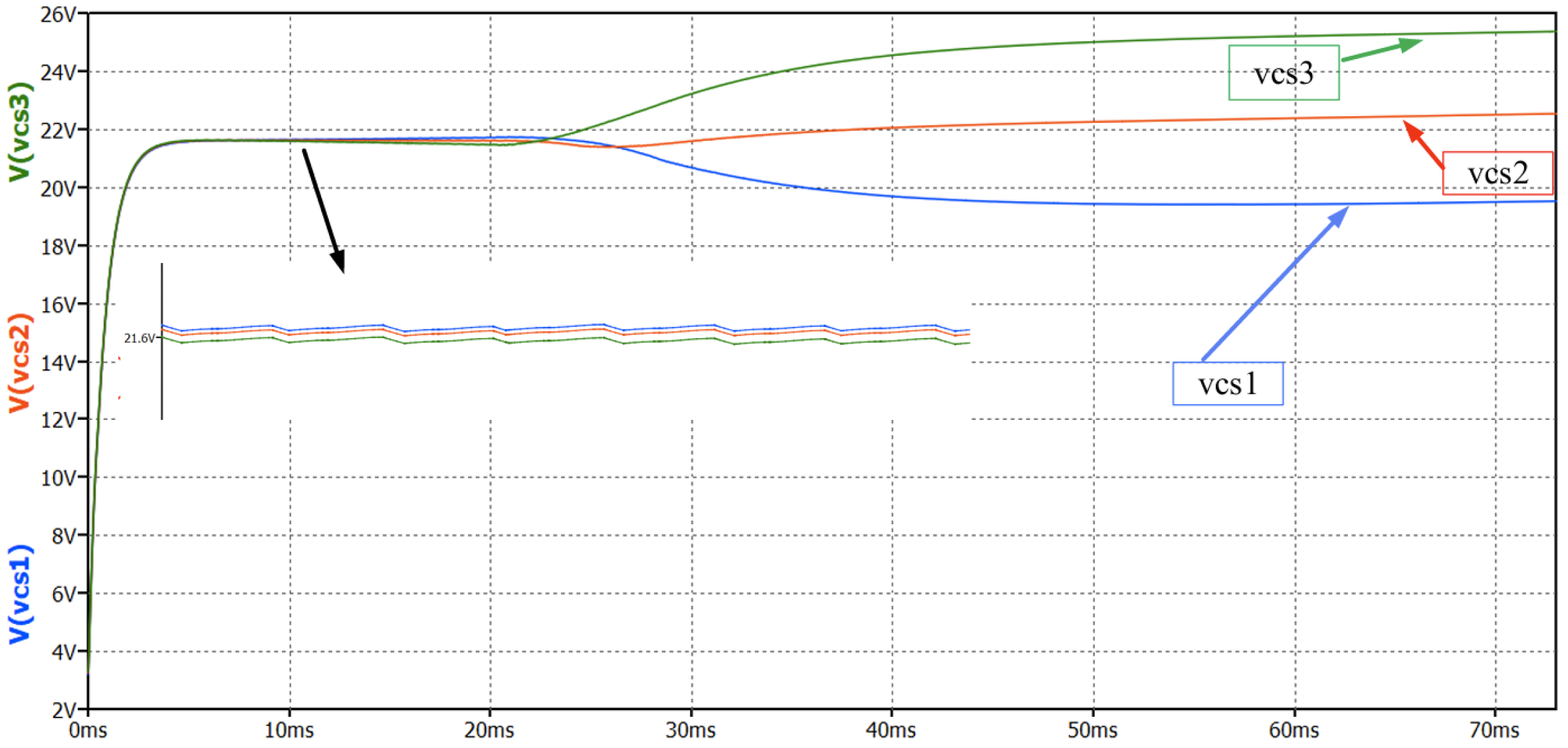

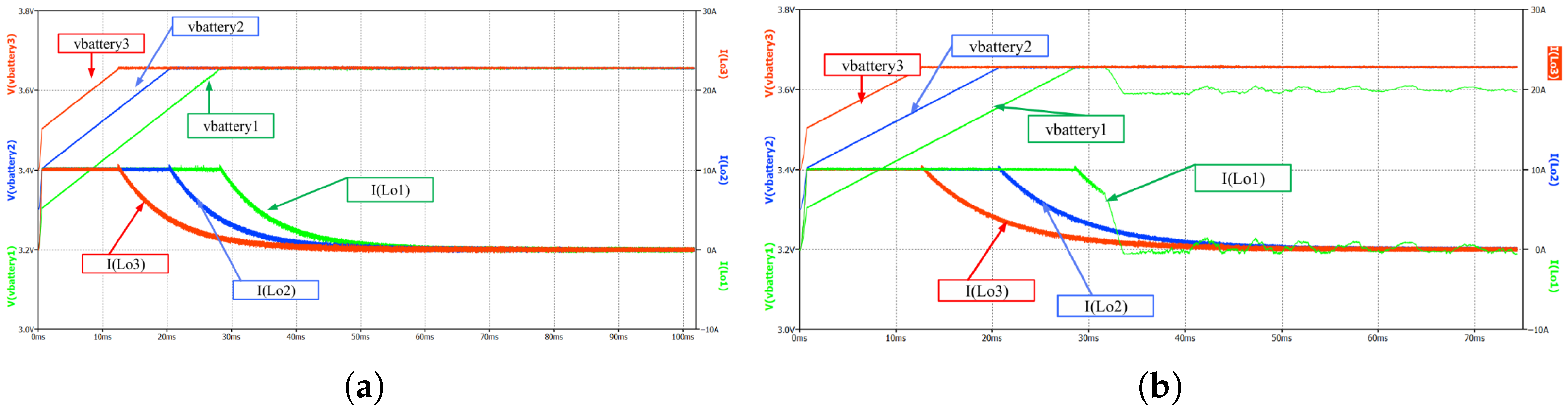

4.2. Analysis of Battery Balanced Charging Process and Control System

5. System Experimental Verification and Analysis

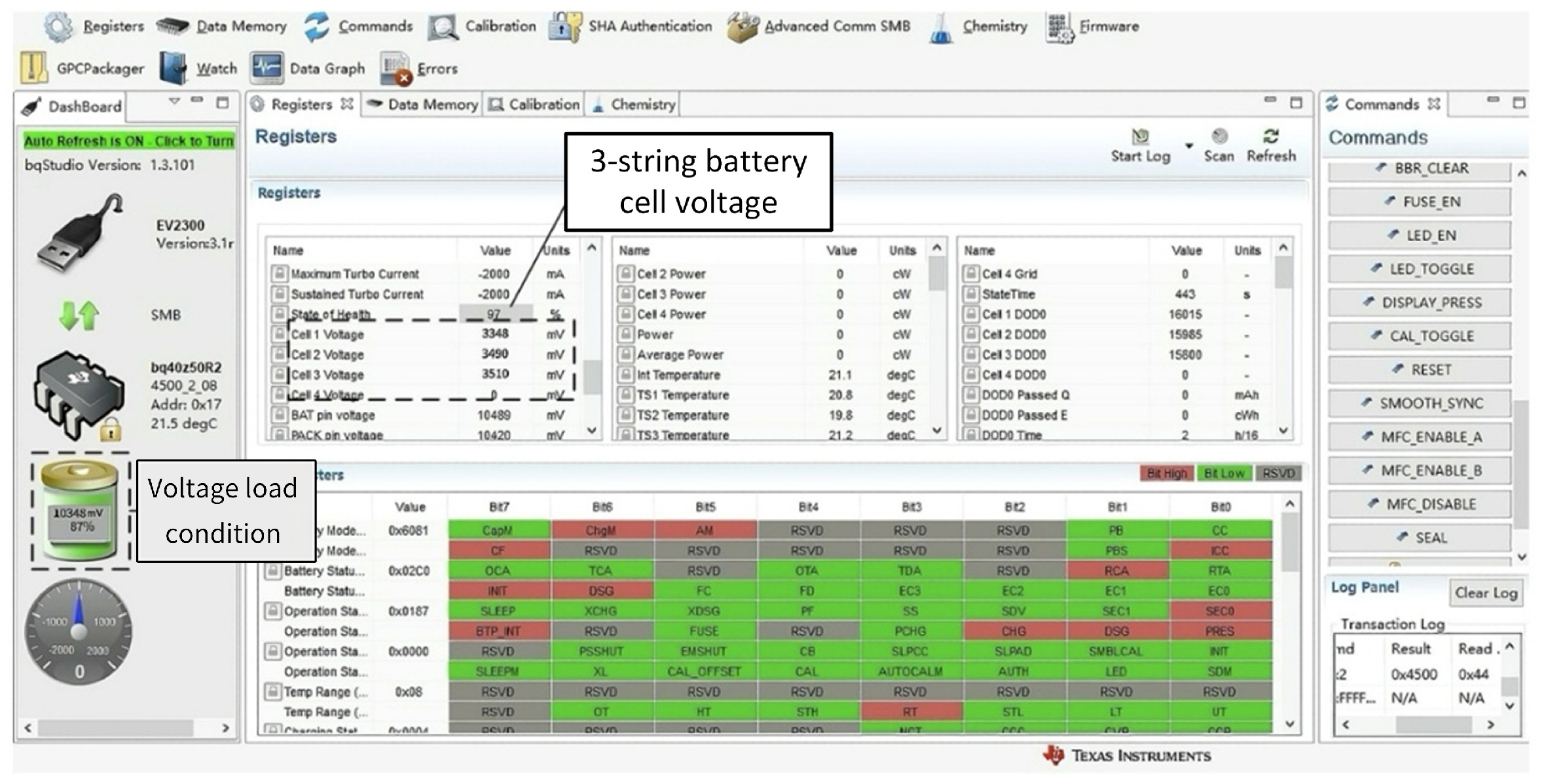

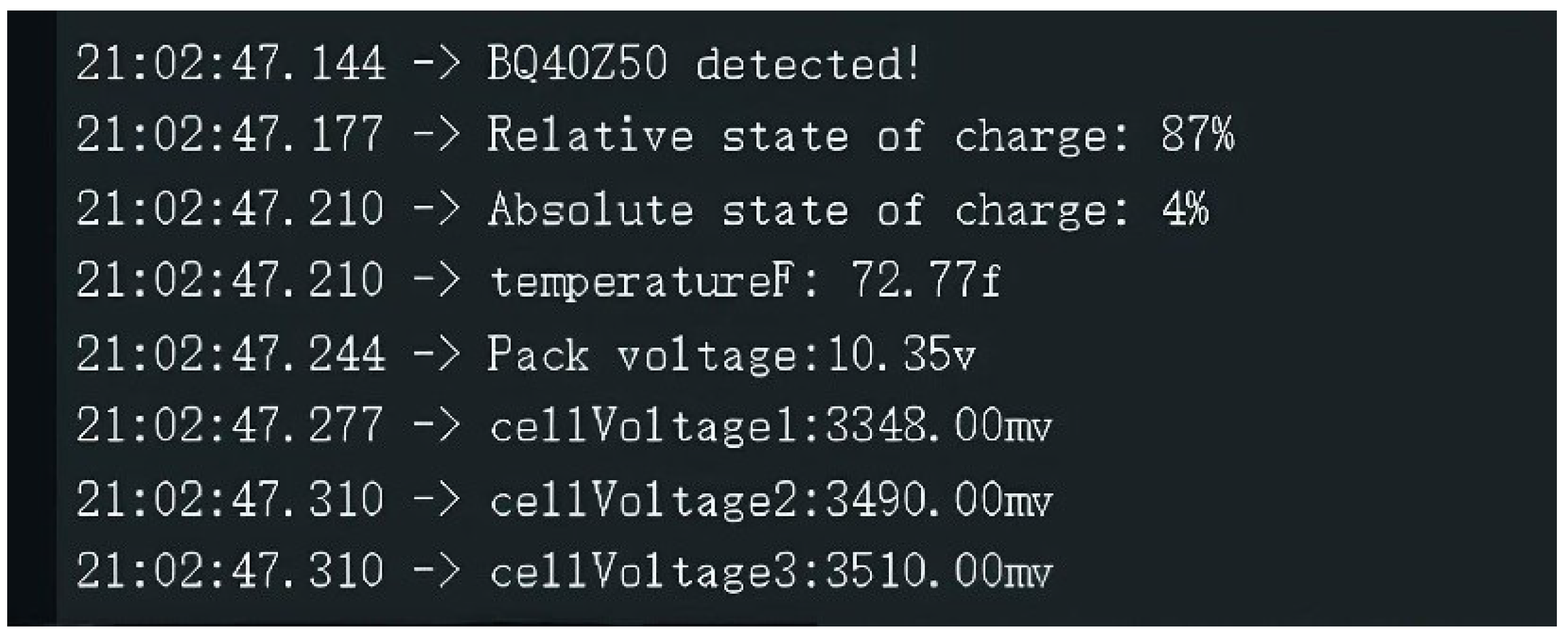

5.1. Lithium Battery Management System Performance Test

5.2. Experimental Analysis of CV and CC Function

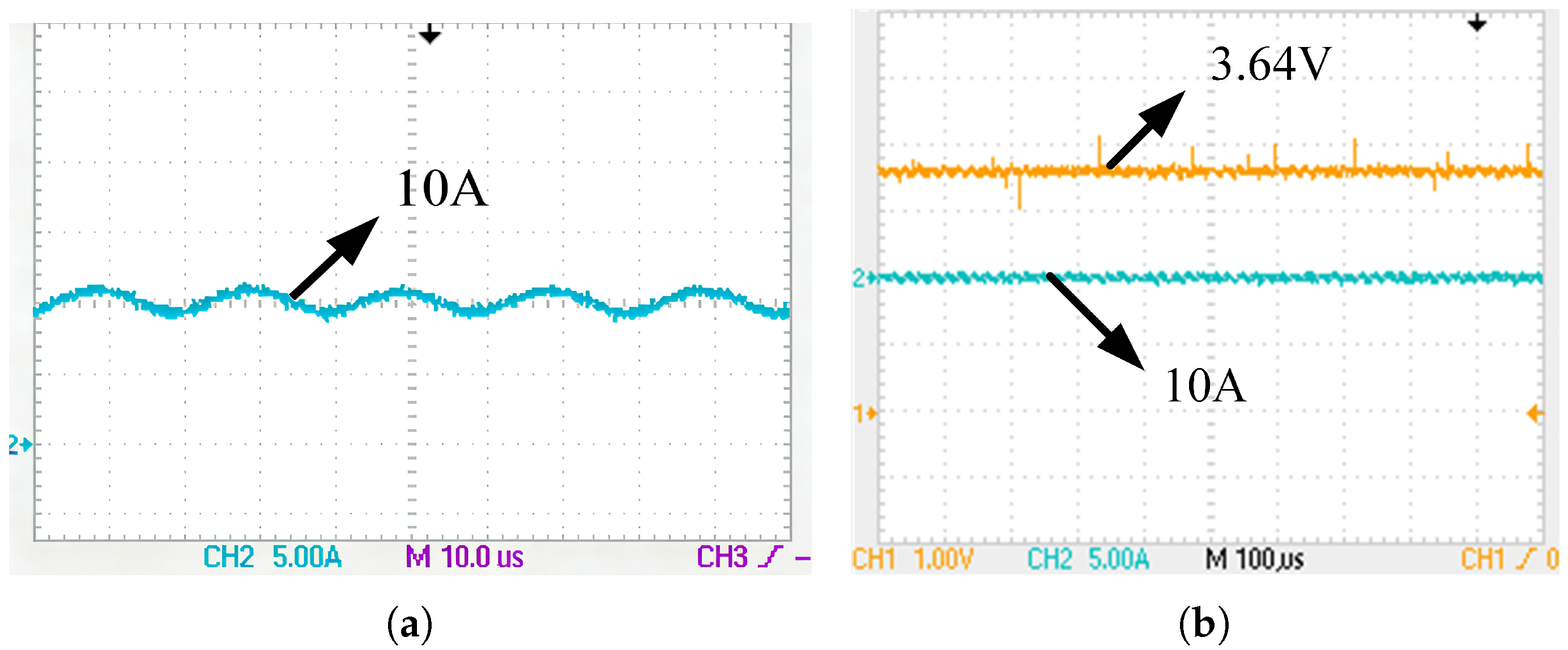

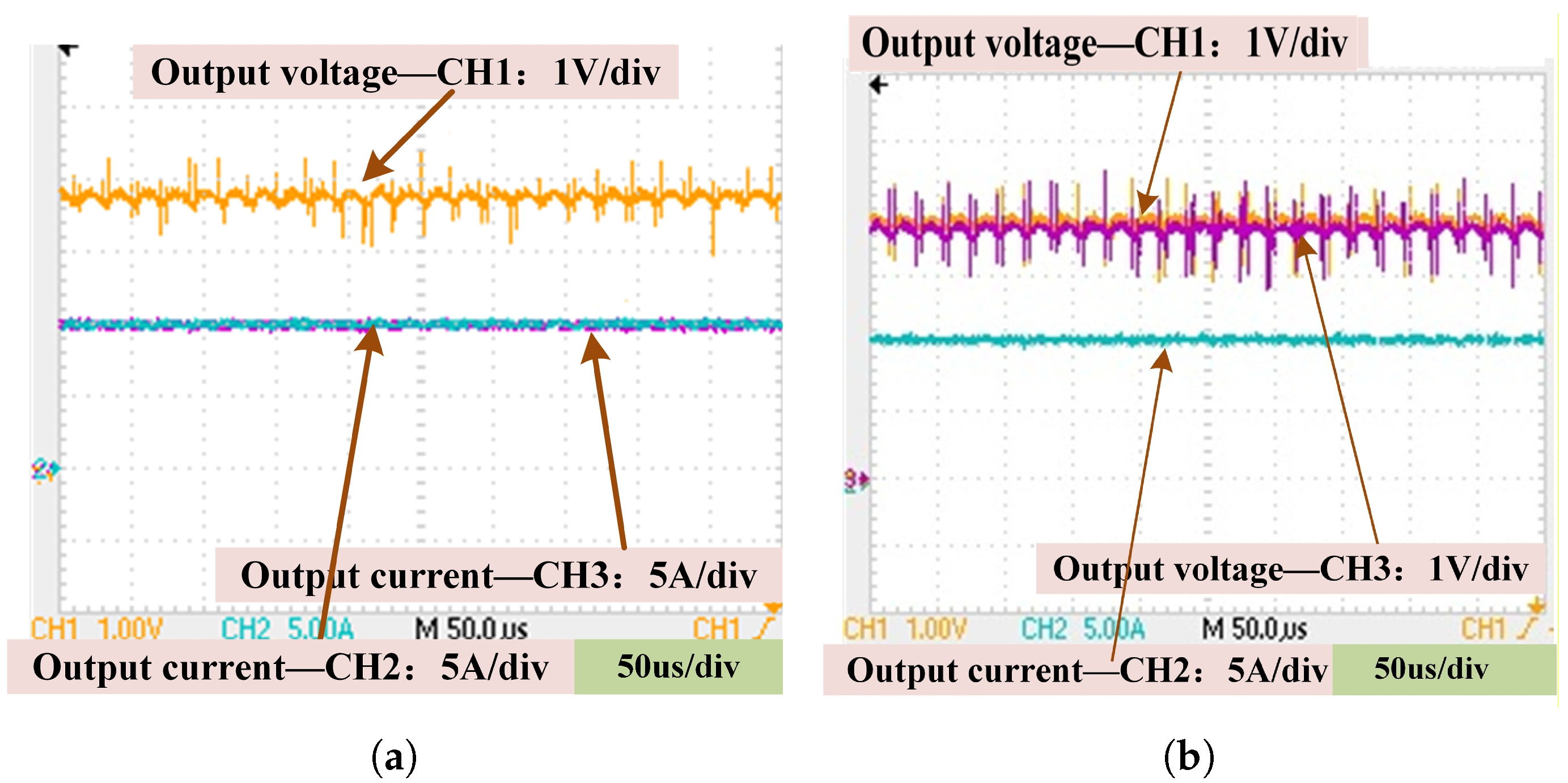

- (1)

- In CV mode, the load voltage was gradually varied from 3.0 to 3.65 V to emulate a battery CC charging process. As shown in Figure 22a, the module output current remained stable at approximately 10 A, meeting the design specifications.

- (2)

- In CC mode, the load current was adjusted from 0 to 10 A to simulate a battery CV charging process. As depicted in Figure 22b, the module output voltage stayed around 3.64 V, satisfying the design requirements.

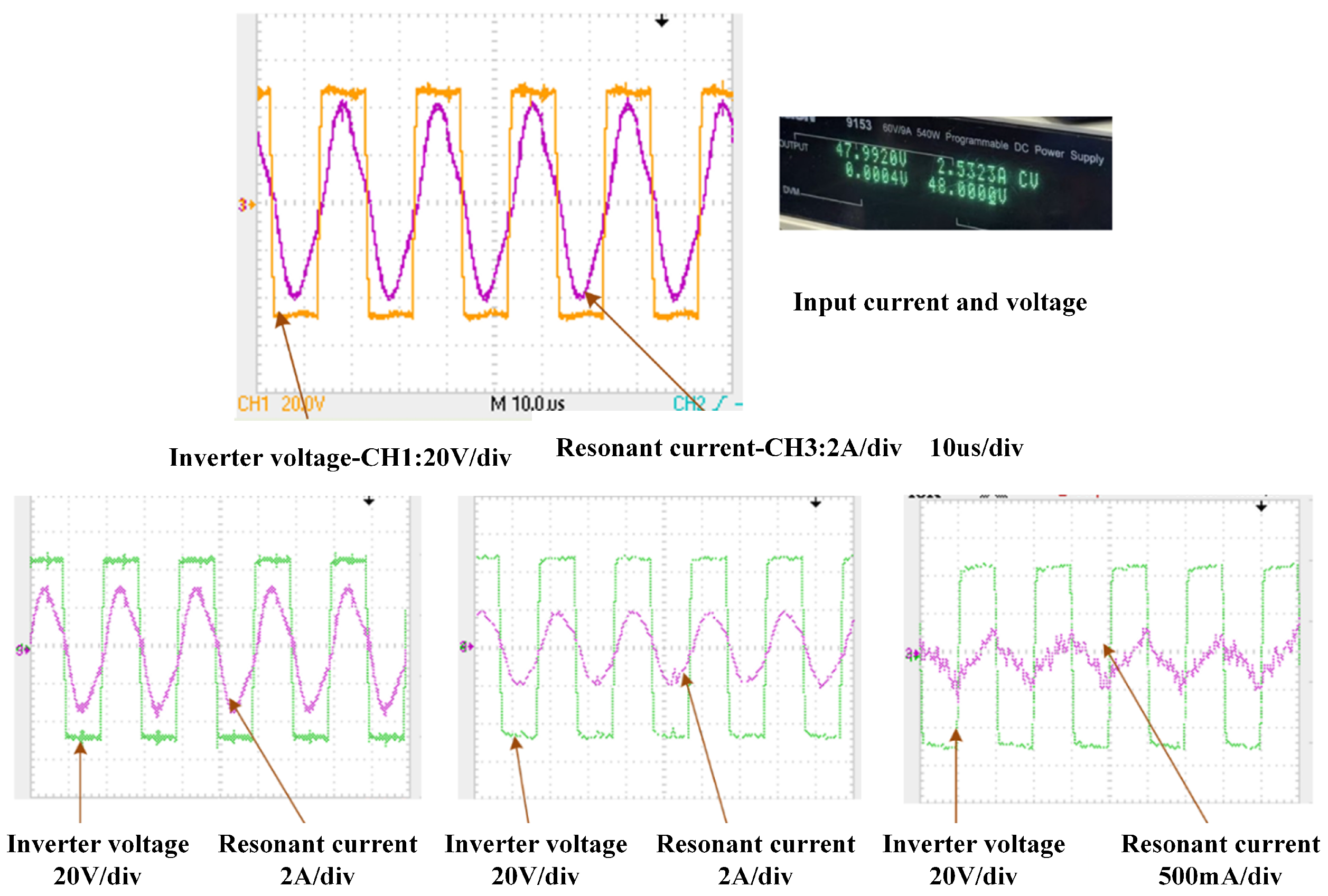

5.3. Experimental Analysis of Battery Balancing System

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devi, B.; Kumar, V.S.; Leelavathi, M. Innovations in Battery Technologies of Electric Vehicle: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Energy, Materials and Communication Engineering (ICEMCE), Madurai, India, 14–15 December 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Liaw, B. Impact of Battery Cell Imbalance on Electric Vehicle Range. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2022, 1, 100025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, F.S.J.; Bergveld, H.J.; Donkers, M.C.F. Range Maximisation of Electric Vehicles through Active Cell Balancing Using Reachability Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2019 American Control Conference (ACC), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 10–12 July 2019; pp. 1567–1572. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Bharatiraja, C.; Udhayakumar, K.; Devakirubakaran, S.; Sekar, K.S.; Mihet-Popa, L. Advances in Batteries, Battery Modeling, Battery Management System, Battery Thermal Management, SOC, SOH, and Charge/Discharge Characteristics in EV Applications. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105761–105809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacap, J.; Park, J.W.; Beslow, L. Development and Demonstration of Microgrid System Utilizing Second-Life Electric Vehicle Batteries. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, T.; Liu, B.; Wang, C.J.; Ye, J.L.; Liu, S. Novel Hybrid Thermal Management System for Preventing Li-Ion Battery Thermal Runaway Using Nanofluids Cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 201, 123652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T.; Ni, M. Battery Thermal Management System with Heat Pipe Considering Battery Aging Effect. Energy 2023, 263, 126116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Bae, S. Estimating Battery State-of-Charge with a Few Target Training Data by Meta-Learning. J. Power Sources 2023, 553, 2323–4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Mei, X.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, J. A Relative State of Health Estimation Method Based on Wavelet Analysis for Lithium-Ion Battery Cells. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 6973–6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, D.F.; Howey, D.A. Completely Decentralized Active Balancing Battery Management System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, T.; Wang, Q. Experimental Study on the Influence of Different Heating Methods on Thermal Runaway of Lithium-Ion Battery. J. Energy Storage 2021, 42, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaeminezhad, N.; Ouyang, Q.; Hu, X.; Xu, G.; Wang, Z. Active Cell Equalization Topologies Analysis for Battery Packs: A Systematic Review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 9119–9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Smadi, M.K.; Abu Qahouq, J.A. Evaluation of Current-Mode Controller for Active Battery Cells Balancing with Peak Efficiency Operation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeber, M.; Heinzelmann, A.; Abdeslam, D.O. Analysis of an Active Charge Balancing Method Based on a Single Nonisolated DC/DC Converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2257–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, S.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y. A New Kind of Balancing Circuit With Multiple Equalization Modes for Serially Connected Battery Pack. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 2142–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. Isolated Bidirectional DC–DC Converter With Quasi-Resonant Zero-Voltage Switching for Battery Charge Equalization. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 4388–4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Peng, S.E. Lithium-Ion Battery Charge Equalization Algorithm for Electric Vehicle Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 2541–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Peng, F.; Wang, H. An LCC-Based String-to-Cell Battery Equalizer With Simplified Constant Current Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, P.H.; Choi, S.J. Direct Cell-to-Cell Equalizer for Series Battery String Using Switch-Matrix Single-Capacitor Equalizer and Optimal Pairing Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 8625–8639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gui, H.; Gu, D.J.; Yang, Y.; Ren, X. A Hierarchical Active Balancing Architecture for Lithium-Ion Batteries. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 2757–2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Horstkötter, I.; Bäker, B. A Novel Approach for Modelling Voltage Hysteresis in Lithium-Ion Batteries Demonstrated for Silicon Graphite Anodes: Comparative Evaluation Against Established Preisach and Plett Model. J. Power Sources Adv. 2024, 26, 100139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyushin, Y.V.; Novozhilov, I.M. Methodology of Inspection of Absolute Stability of Pulse Distributed Control System. In Proceedings of the 2019 XXII International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements (SCM), St. Petersburg, Russia, 23–25 May 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Topology | Current | Efficiency | Scalability | For ≥100 Ah |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | Capacitor switched | 0.5–1.2 A | 68–78% | Medium | Limited |

| [20] | MOSFET matrix C2C | 1–2 A | 75–82% | Low | Moderate |

| [19] | Resonant inductor | 3–5 A | 85–90% | Medium | Good |

| This Work | SIMO + SR buck | 10 A | 90–94% | High | Excellent |

| Design Parameters | Parameter Values |

|---|---|

| Input Voltage | 48 V |

| Switching Tube Operating Frequency | 50 kHz |

| Coupling Capacitor | 4 µF |

| Transformer Primary Inductances L1, L2, L3 | 250 µH |

| Transformer Secondary Inductances L4, L5, L6 | 570 µH |

| Transformer Leakage Inductance L7 | 2.5 µH |

| Filter Capacitors Cs1, Cs2, Cs3 | 2000 µF |

| Output Inductances Lo1, Lo2, Lo3 | 196 µH |

| Output Capacitors Co1, Co2, Co3 | 22 µF |

| Parameter Name | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Nominal Capacity | 100 Ah |

| Nominal Voltage | 3.2 V |

| Battery Internal Resistance (1 kHz) | 0.5 m |

| Charge Cut-off Voltage | 3.65 V |

| Discharge Cut-off Voltage | 2.5 V |

| Maximum Charge C-rate | 1 C |

| Maximum Discharge Current | 1 C |

| Operating Temperature | 0–55 °C |

| Sampling No. | Battery 1 | Battery 2 | Battery 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFE | Fluke | Error | AFE | Fluke | Error | AFE | Fluke | Error | |

| 1 | 3348 | 3349 | 1 | 3490 | 3490 | 0 | 3510 | 3511 | 1 |

| 2 | 3422 | 3425 | 3 | 3530 | 3531 | 1 | 3547 | 3547 | 0 |

| 3 | 3525 | 3525 | 0 | 3605 | 3606 | 1 | 3617 | 3618 | 1 |

| 4 | 3572 | 3572 | 0 | 3625 | 3628 | 3 | 3638 | 3636 | 2 |

| 5 | 3621 | 3621 | 0 | 3639 | 3640 | 1 | 3646 | 3646 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, W.; Zhou, F. Active Battery Balancing System for High Capacity Li-Ion Cells. Energies 2025, 18, 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236371

Jiang W, Zhou F. Active Battery Balancing System for High Capacity Li-Ion Cells. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236371

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Wei, and Feng Zhou. 2025. "Active Battery Balancing System for High Capacity Li-Ion Cells" Energies 18, no. 23: 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236371

APA StyleJiang, W., & Zhou, F. (2025). Active Battery Balancing System for High Capacity Li-Ion Cells. Energies, 18(23), 6371. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236371