Abstract

Latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES) using inorganic salt hydrates is a promising technology for buffering renewable energy fluctuations; however, phase-dependent heat transfer remains insufficiently understood for design optimization. In this study, a shell-and-tube storage module with a circular-finned tube was constructed and filled with 13.17 kg of barium hydroxide octahydrate (BHO). Discharge tests were conducted with heat transfer fluid (HTF) inlet temperatures ranging from 20 °C to 50 °C and flow rates of 10–25 L/min, while charging was performed at 90 °C. The overall heat transfer coefficient () was derived using the logarithmic mean temperature difference method, the inside coefficient (hi) was calculated by the Petukhov correlation, and the outside coefficient (ho) was obtained via thermal-resistance network. Results show that the average discharge energy was approximately 1.027 kWh (except 0.859 kWh at 50 °C inlet), with a mean utilization efficiency of 79.25%. The was consistently highest in the liquid phase, followed by the latent and solid phases, with ranges of 0.257–0.863, 0.025–0.072, and 0.015–0.044 kW/m2·°C, respectively. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the HTF flow rate strongly influenced Uo across all phases, whereas inlet temperature played only a minor role. The outside coefficient was 0.033–0.162 kW/m2·°C in the latent regime and 0.018–0.064 kW/m2·°C in the solid regime, with a notable peak around Reynolds number 1.3 × 104 in the latent phase. These findings provide detailed phase-resolved and data for inorganic salt hydrate storage and highlight design insights such as the diminishing returns of flow rate increase beyond a threshold, offering valuable guidelines for sizing and operation of LHTES in Power-to-Heat applications.

1. Introduction

The global transition toward carbon-neutral energy systems, driven by the urgent need to address climate change and enhance energy security, has led to a rapid expansion of renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that by 2030, the world’s installed renewable energy capacity will increase by over 90% compared to 2023 levels. In response to this trend, nations are implementing ambitious long-term energy strategies. For instance, South Korea’s “11th Basic Plan for Long-term Electricity Supply and Demand (2024–2038)” aims to increase renewable energy capacity from 31.4 GW in 2023 to 125.9 GW by 2038, constituting approximately 47% of the total power generation infrastructure [1].

This fundamental shift in the energy landscape introduces significant technical challenges. The inherent intermittency of renewable energy sources, which fluctuate with weather conditions and time of day, creates a temporal mismatch between energy generation and demand. To ensure grid stability and reliably utilize this variable output, energy storage systems are indispensable [2,3]. Among the various enabling technologies, Power-to-Heat (P2H) has emerged as an effective strategy for sector coupling. P2H converts surplus renewable electricity into thermal energy, which can be stored to alleviate grid congestion and improve the overall efficiency of renewable energy utilization. The viability of P2H is critically dependent on an associated Thermal Energy Storage (TES) technology. TES systems are broadly categorized as sensible, latent, or thermochemical storage. Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage (LHTES) is particularly attractive due to its high energy storage density and its ability to store and release heat at a nearly constant temperature during the phase transition of a Phase Change Material (PCM).

LHTES systems operate on a simple principle: during the charging process, a high-temperature Heat Transfer Fluid (HTF) melts the solid PCM, storing latent heat [4]. During discharging, the liquid PCM releases this stored heat to a low-temperature HTF, causing it to solidify. However, a major impediment to the widespread application of PCMs is their typically low thermal conductivity, which limits the rates of heat charging and discharging. To overcome this limitation, various thermal enhancement techniques have been investigated, including the dispersion of highly conductive nanoparticles and the use of porous media. Among these, the integration of fins into the heat exchanger is one of the most practical and effective methods due to its simple structure, low cost, high durability, and proven reliability [5,6]. Agyenim et al. demonstrated through extensive experiments that various fin structures can significantly improve heat transfer rates compared to unfinned tubes [7]. Moreover, Esapour et al. numerically confirmed that fin structures accelerate the movement of the phase-change interface and markedly improve the system’s response time [8]. In addition to these methods, microencapsulation strategies, the incorporation of nanofillers, and the use of metal foams represent other promising approaches for enhancing the effective thermal conductivity of PCM. Rolka et al. suggested adding 1 wt% graphene nanoparticles to PCM, which increased its thermal conductivity by approximately threefold in the solid stability reduction of about 6–9% [9]. Chen et al. reported that a PCM integrating SA and MF reduced the melting time by 61.42% compared with pure PCM [10]. Anfas Mukram et al. evaluated the performance of microencapsulated PCM embedded in specially fabricated cement bricks. Their results indicated that, relative to conventional bricks, the modified bricks effectively reduced heat ingress and lowered indoor temperatures by 1.2 °C [11].

Despite these advancements, inorganic salt hydrates, which offer attractive properties such as high latent heat capacity, superior thermal conductivity, and lower cost, have faced delayed practical implementation due to inherent material challenges, including supercooling, phase segregation, and corrosiveness [12,13]. To address these limitations, numerous studies have focused on developing effective strategies for mitigating supercooling, stabilizing phase behavior, and preventing corrosion. Zhang et al. found that 4 wt% NaCl reduced the supercooling degree to 1.1 °C, while adding 0.8 wt% nano-Cu particles further lowered it to approximately 0.5 °C [14]. Cui et al. demonstrated that the incorporation of 3 wt% carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) into nano-CU/SAT composite phase change materials effectively suppressed phase separation and preserved the latent heat of fusion even after 50 repeated heating-cooling cycles [15]. Moreno et al. investigated the corrosion behavior of eleven salt hydrates on four metallic substrates (copper, aluminum, carbon steel, stainless steel) classifying the PCMs according to their applicability in cooling or heating systems [16]. Barium Hydroxide Octahydrate (BHO), the PCM utilized in the present study, has likewise attracted research interest aimed at resolving issues such as supercooling, phase segregation, and corrosion. Nevertheless, investigations that implement BHO in actual thermal storage modules and rigorously evaluate their performance are still limited. Advancing the practical deployment of BHO in thermal energy storage applications therefore requires precise experimental determination of its thermo-physical characteristics, accompanied by structured methodologies for system design and performance optimization.

In particular, most finned-tube LHTES studies to date have examined paraffin-based PCMs combined with straight or longitudinal fin geometries, whereas the present work focused on a single circular-finned tube module filled with the inorganic salt hydrate BHO operating in a high-temperature range relevant to P2H applications. Furthermore, previous studies on BHO and similar salt hydrates have mainly reported material-level thermophysical properties and bulk charging/discharging behavior, rather than detailed module-scale heat transfer characteristics. In contrast, the present study experimentally determines phase-resolved overall and outside heat transfer coefficients ( and ) for the solid, latent, and liquid regimes in a practical finned-tube LHTES module, thereby addressing this specific deficiency in the existing literature.

This study investigated the heat transfer characteristics of an LHTES module specifically designed for an inorganic PCM. A shell-and-tube module featuring circular fins was designed and fabricated to maximize the heat transfer area between the HTF and the PCM. BHO, an inorganic salt hydrate with a phase change temperature suitable for medium-temperature applications, was selected as the storage medium. A dedicated experimental apparatus was constructed to perform a quantitative analysis of the module’s charging and discharging characteristics under a range of operating conditions. The primary objectives are to determine the phase-dependent heat transfer performance by calculating the overall and outside heat transfer coefficients and to identify the key operational parameters influencing the module’s efficiency, thereby providing essential data for the design and optimization of LHTES systems for P2H and other industrial applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. LHTES Module and Phase Change Material

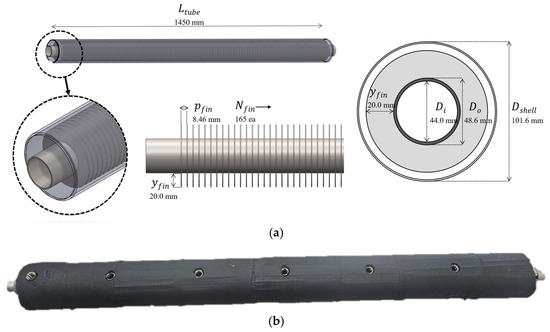

The LHTES module for this study was designed as a shell-and-tube heat exchanger with a target thermal energy storage capacity of approximately 1 kWh, based on established heat transfer correlations and prior research [17]. The module consists of a single heat transfer tube with external circular fins, all enclosed within an outer shell. A detailed schematic and a photograph of the manufactured module are shown in Figure 1, and its specifications are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Latent heat thermal storage module with PCM mass of 13.17 kg: (a) Design drawing including a cross-sectional view and dimensions, and (b) photograph of the manufactured module.

Table 1.

Specifications of latent heat thermal storage module.

The central heat transfer tube, made of SUS304 stainless steel, had an outer diameter of 48.6 mm, an inner diameter of 44.0 mm, and a total length of 1450 mm. To enhance heat transfer, 165 circular fins made of SUS316 stainless steel were installed on the tube’s outer surface using an interference fit. Each fin had a height of 20.0 mm, and the fins were spaced with a pitch of 8.46 mm. This finned-tube assembly is housed within a shell with an outer diameter of 101.6 mm. The effective internal volume within the shell available for the PCM is 0.0076 m3, which was filled with 13.17 kg of the selected PCM.

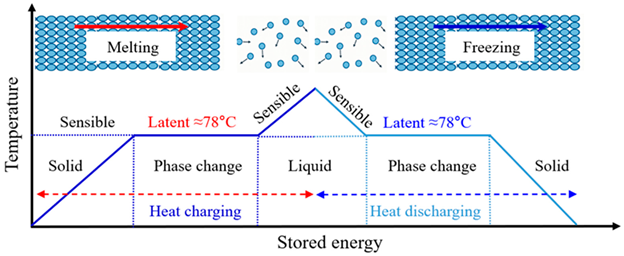

The PCM selected in this study was barium hydroxide BHO, an inorganic salt hydrate. The thermophysical properties of BHO and the phase-change regimes illustrated in the above schematic are summarized in Table 2, indicating that BHO is suitable for high-temperature thermal energy storage applications. The temperature–stored-energy (enthalpy) behavior of the PCM during heat charging and discharging can be described as follows: starting from the solid state, sensible heating increases the stored energy approximately in proportion to temperature. When the phase-change temperature is reached, a nearly isothermal latent region forms around 78 °C. In this regime, melting (during charging) or freezing (during discharging) proceeds while a large amount of energy is absorbed or released at almost constant temperature. Once the phase change is completed, the PCM enters the liquid sensible region, where the stored energy again increases (or decreases) almost linearly with temperature. With a phase-change temperature of about 78 °C and a high latent heat of fusion in the range of 233–332 kJ/kg, BHO provides a substantially higher energy storage density than many organic PCMs [18]. BHO was selected for this study due to its high density, making it suitable for high-density thermal storage applications. Furthermore, its specific heat capacities in both solid and liquid states contribute to its overall effective sensible heat storage.

Table 2.

Thermophysical Properties of Barium Hydroxide Octahydrate (BHO) * [18,19].

2.2. Experimental Apparatus and Procedure

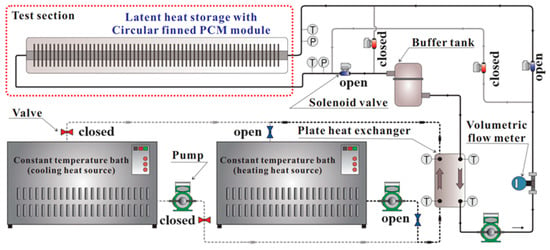

To quantitatively evaluate the thermal performance of the LHTES module, a dedicated experimental apparatus was constructed, as shown schematically in Figure 2. The setup was designed to precisely control and monitor the charging and discharging processes. The HTF (water) temperature was regulated using high- and low-temperature constant-temperature baths connected via a plate heat exchanger. An inverter pump and a volumetric flow meter (accuracy: ±0.03%) were used to control and measure the HTF flow rate circulating through the module.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of experimental setup.

To capture the thermal behavior and phase change dynamics of the PCM, T-type thermocouples (±0.1 °C) were strategically placed within the module. The HTF inlet and outlet temperatures were measured to determine the heat transfer rate. Inside the shell, thermocouples were installed at five equidistant points along the module’s length. At each point, sensors were positioned at the tip of a fin and in the space between fins to monitor the temperature distribution and track the solid–liquid interface during phase change. All sensor signals were collected and recorded in real-time by a data acquisition system for subsequent analysis.

The experiments were conducted under various operating conditions, as detailed in Table 3, to simulate a range of real-world scenarios. For all tests, the charging process was performed with a fixed HTF inlet temperature of 90 °C and continued until the average PCM temperature reached 85 °C. The discharging process was investigated by varying both the HTF inlet temperature (20, 30, 40, 50 °C) and the HTF flow rate (10, 15, 20, 25 L/min). The discharging tests were terminated when the average PCM temperature dropped to 45 °C, except for the case with a 50 °C HTF inlet, where the termination temperature was set to 55 °C.

Table 3.

Experimental Conditions for Charging and Discharging Tests.

2.3. Procedure Data Reduction and Analysis

The experimental data were processed using a set of established thermodynamic and heat transfer equations to quantify the module’s performance. The instantaneous heat transfer rates for charging () and discharging () were calculated from the HTF’s mass flow rate (), specific heat (), and the temperature difference between the inlet () and outlet (), as shown in Equation (1). To address measurement accuracy and uncertainty, the HTF and PCM temperatures were measured using thermocouples calibrated against a reference sensor prior to the experiments, yielding an accuracy of approximately ±0.1 °C for each sensor. Since the data reduction in this study is based on the HTF-side heat transfer rate, the uncertainty of the HTF temperature difference was evaluated using the concept of uncertainty propagation. For a representative operating condition with an HTF inlet temperature of 20 °C, the resulting relative uncertainty of the HTF-side heat quantity was found to be on the order of 10.52% on average. In the late part of discharging, during the solid phase, the HTF inlet–outlet temperature difference becomes very small, so including this region in the evaluation would further increase the relative uncertainty. However, in the liquid and latent regimes, the relative uncertainty remains on the order of a few percent, which we considered sufficient for discussing the phase-dependent heat transfer characteristics.

The total accumulated heat stored () or released () over a process was determined by integrating the instantaneous heat transfer rate from the start time () to the final time (), as given by Equation (2).

The thermal utilization efficiency (), representing the ratio of total energy discharged to total energy charged, was calculated using Equation (3).

For practical comparison, the total accumulated energy was converted to an hourly energy rate in kilowatt-hours () using Equation (4).

The overall heat transfer coefficient based on the outer surface area () was calculated using the Log Mean Temperature Difference (LMTD) method, as shown in Equations (5) and (6), where is the total outer heat transfer area and is the average PCM temperature.

The outside heat transfer coefficient () was determined from the total thermal resistance () by subtracting the resistances due to internal convection and tube wall conduction, as expressed in Equation (7), and should therefore be interpreted as an effective, lumped outside coefficient that includes the effects of fin efficiency and fin–tube contact resistance. Here, and (0.2214 m2) are the inner and outer surface areas, is the inside heat transfer coefficient, and is the thermal conductivity of the tube material.

The inside heat transfer coefficient () was calculated using the Nusselt number (), as shown in Equation (8).

For the turbulent flow regime within the tube, the Nusselt number was calculated using the Petukhov correlation (Equation (9)), which is highly regarded for its accuracy.

The friction factor (f) required for the Petukhov correlation was calculated using the Gnielinski correlation for fully developed turbulent flow in smooth tubes, given by Equation (10) [20].

3. Results

3.1. Transient Thermal Dynamics of Charging and Discharging

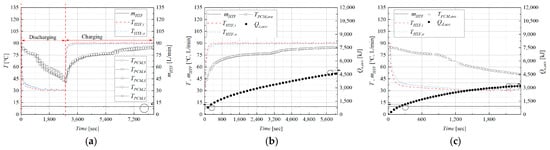

The dynamic thermal behavior of the LHTES module was characterized through detailed time-series analysis of temperature and energy data. Figure 3 illustrates a representative experimental cycle, specifically for a discharge process with an HTF inlet temperature of 30 °C and a flow rate of 10 L/min, followed by a charging process. The discharge phase lasted 47 min, while the subsequent charging phase required 105 min. This difference in duration reveals an inherent asymmetry in the heat transfer dynamics. Charging is driven by a larger and more stable temperature difference between the 90 °C HTF and the cooler PCM, leading to a relatively consistent heat transfer rate. In contrast, during discharging, the temperature of the PCM continuously decreases, which in turn reduces the LMTD and slows the rate of heat extraction over time.

Figure 3.

Heat transfer characteristics during charging and discharging of the latent heat thermal storage module: (a) Temperature and flow rate profiles during heat charging and discharging process (at: 10 L/min, = 90 °C (Charging), = 30 °C (Discharging)). (b) Heat charging process (at: L/min, 90 °C). (c) Heat discharging process (at: = 10 L/min, 30 °C).

During the charging process, the average PCM temperature rises steadily. This rise is characterized by three distinct stages: a rapid increase when the PCM is in its solid state (sensible heating), followed by a much slower temperature rise or plateau near 78 °C as the PCM absorbs latent heat during melting, and finally another period of rapid temperature increase once the PCM is fully in the liquid state. Correspondingly, the accumulated stored energy increases almost linearly with time, indicating a relatively stable heat charging rate.

Conversely, during the discharging process, the average PCM temperature decreases. A similar three-stage pattern is observed: a period of sensible heat release from the liquid PCM, a prolonged period of nearly isothermal heat release at the phase-change temperature (latent heat), and a final stage of sensible heat release from the solid PCM. The temperature difference between the HTF inlet and outlet diminishes as the PCM cools, causing the rate of heat discharge to decrease over time. This results in a non-linear, decelerating curve for the accumulated discharged energy. For this specific case, the total discharged energy was 3330 kJ, compared to a stored energy of 4665 kJ, yielding a thermal utilization efficiency of 71.37%.

3.2. Heat Transfer Performance and Efficiency

As shown in Figure 4a, across all experimental conditions, excluding those with a 50 °C HTF inlet temperature, the module demonstrated consistent performance, delivering an average heat discharge of 1.027 kWh. The average thermal utilization efficiency for these conditions was calculated to be 79.25%, and under the same discharging end condition, it reached a maximum of 89.97%. This value represents a practical, system-level efficiency that accounts not only for the thermodynamic processes but also for real-world factors such as ambient heat loss from the module’s exterior and piping.

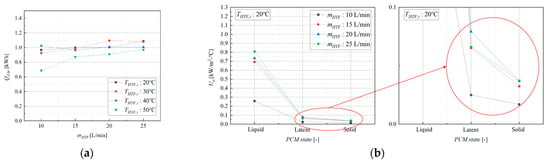

Figure 4.

Heat transfer rate and overall heat transfer coefficient of a latent heat storage module: (a) Heat transfer rate (discharging case), and (b) overall heat transfer coefficient (at: = 20 °C).

A notable deviation was observed for tests conducted with an HTF inlet temperature of 50 °C, where the average discharged energy was significantly lower at 0.859 kWh. This reduction is directly attributable to the experimental termination condition for this specific case, which was set at a PCM temperature of 55 °C instead of 45 °C. This higher cut-off temperature meant that a substantial portion of the PCM’s latent heat, and some of its sensible heat in the solid phase, was not extracted before the test concluded. This finding underscores that the operational cut-off temperature is not merely a procedural detail but a critical control parameter that directly dictates the achievable energy recovery and round-trip efficiency of the system. Setting this temperature too high strands a significant portion of the stored energy within the module, while setting it too low may be impractical if the application requires a certain minimum output temperature.

A central finding of this study is the profound dependence of the overall heat transfer coefficient () on the physical state of the PCM. As shown in Figure 4b and summarized in Table 4, the heat transfer performance varies dramatically across the three phases. The highest values, ranging from 0.257 to 0.863 kW/m2·°C, were observed when the PCM was in the liquid state. In the latent phase, where both solid and liquid coexist, the values were an order of magnitude lower, ranging from 0.025 to 0.072 kW/m2·°C. The lowest performance was recorded in the solid state, with values between 0.015 and 0.044 kW/m2·°C.

Table 4.

Heat transfer rate and overall heat transfer coefficient during discharge process.

This significant variation is governed by the dominant heat transfer mechanisms in each phase. In the liquid phase, natural convection currents develop within the molten PCM, creating fluid motion that significantly enhances heat transfer from the finned surface, resulting in a high . During solidification, a layer of solid PCM begins to form on the cooler tube and fin surfaces. Since heat transfer through this solid layer is dominated by pure conduction, which is limited by the PCM’s low thermal conductivity, it introduces a substantial thermal resistance. As this solid layer thickens, the overall heat transfer coefficient progressively decreases. Once the PCM is entirely solid, conduction becomes the sole mechanism for heat transfer on the shell side, leading to the lowest observed values. This phase-dependent behavior is a critical characteristic of LHTES systems; it implies that performance is not static but changes dynamically throughout an operational cycle. Consequently, traditional heat exchanger design methods that assume a constant U-value are inadequate for LHTES modules and can lead to significant errors in performance prediction and system sizing. A dynamic or phase-averaged approach is essential for accurate engineering design.

3.3. Analysis of the Outside Heat Transfer Coefficient

To isolate the performance on the PCM side, the outside heat transfer coefficient (ho) was calculated. An analysis of the heat capacity distribution during the discharge process from 85 °C to 45 °C showed that the latent phase accounted for the majority of the heat transfer (72.94%), followed by the solid phase (22.62%), while the liquid phase contribution was minimal (4.44%). Therefore, the analysis of focused on the dominant latent and solid phases.

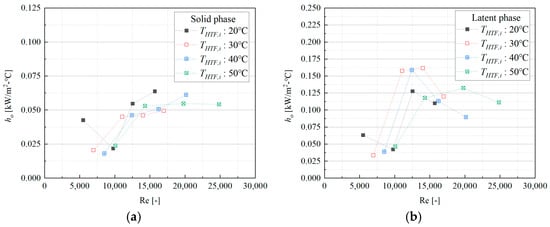

As shown in Figure 5, ho varied with the HTF Reynolds number (ReHTF). In the latent phase, ranged from 0.033 to 0.162 kW/m2·°C. For all discharging inlet temperatures considered (20–50 °C), a similar non-monotonic trend was observed: increased with ReHTF in the low-Re region, reached a local maximum in the range ReHTF ≈ 1.2 × 104–1.4 × 104, and then tended to level off or slightly decrease at higher ReHTF. This behavior reveals a critical trade-off. Initially, as the HTF flow rate and Reynolds number increase, the internal convective heat transfer () improves, reducing the dominant thermal resistance on the tube side and allowing more heat to be extracted, which increases the calculated . However, beyond the optimal point, the higher heat flux accelerates the formation of an insulating layer of solid PCM on the finned surface. The conductive thermal resistance of this growing solid layer eventually becomes the dominant limiting factor, causing the effective outside heat transfer performance to decline. This non-monotonic behavior indicates that simply maximizing the HTF flow rate is not an optimal strategy for enhancing the discharge rate; an optimal flow rate exists that balances internal convection with external solidification dynamics.

Figure 5.

Outside heat transfer coefficient of a latent heat storage module: (a) latent phase, and (b) solid phase.

In the solid phase, values ranged from 0.018 to 0.064 kW/m2·°C, which is, on average, 56.4% lower than in the latent phase. This confirms that once the PCM is fully solidified, the system’s performance is severely limited by the poor thermal conduction through the solid PCM layer.

3.4. Statistical Analysis of Influencing Parameters

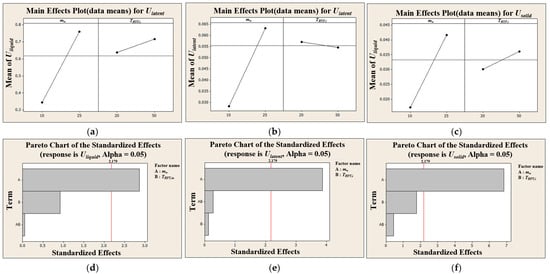

In this study, response surface methodology (RSM) was applied using Minitab (Release 14.12.0) to analyze key response variables obtained from the discharging experiments, which characterize the thermal performance of the module, with the HTF flow rate and inlet temperature treated as the main factors. In particular, the overall heat transfer coefficient for each of the three PCM phases (solid, latent, and liquid) was taken as a primary response. Main effects plots and Pareto charts were generated to assess the influence of HTF flow rate and HTF inlet temperature on the overall heat transfer coefficient () of each of the three PCM phases.

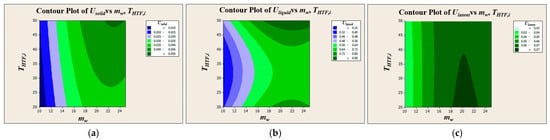

As shown in Figure 6, the HTF flow rate had a large, positive, and statistically significant effect on for all phases. This is visually represented by the steep upward slope in the main effects plots and the large bars for flow rate in the Pareto charts, which far exceeded the threshold for statistical significance. This is because increasing the flow rate enhances turbulence inside the tube, reducing the internal convective thermal resistance and thereby improving the overall heat transfer. In contrast, the HTF inlet temperature was found to have a minimal and statistically insignificant effect on across all phases. This is evident from the nearly flat lines for temperature in the main effects plots and the very small bars in the Pareto charts. This finding is further supported by the contour plots in Figure 7, where the contour lines for constant are nearly vertical, indicating strong dependence on the x-axis (flow rate) and weak dependence on the y-axis (temperature). This robust statistical confirmation has a critical implication for system design and control. It is far more effective to modulate the HTF flow rate (i.e., pumping power) to control the charge and discharge rates than it is to alter the operating temperature of the thermal source or sink. This is particularly relevant for applications such as waste heat recovery, where the source temperature may be fixed, as it demonstrates that performance can still be effectively controlled via the HTF flow.

Figure 6.

Main effects and pareto charts of overall heat transfer coefficient for different PCM states: (a) main effects of Uliquid, (b) main effects of Ulatent, (c) main effects of Usolid, (d) Pareto chart of Uliquid, (e) Pareto chart of Ulatent, and (f) Pareto chart of Usoild.

Figure 7.

Contour plots of overall heat transfer coefficient according to PCM phase state: (a) Usolid, (b) Uliquid, and (c) Ulatent.

4. Conclusions

In this study, an LHTES module using circular-finned tubes and an inorganic PCM (BHO) was fabricated and experimentally tested to analyze its phase-dependent heat transfer characteristics. Based on the experimental results and statistical analysis, the following conclusions were drawn:

- (1)

- The LHTES module demonstrated a reliable average heat discharge capacity of 1.027 kWh and a thermal utilization efficiency of 79.25% under the tested conditions, confirming the viability of the design.

- (2)

- The discharge termination temperature was identified as a critical operational parameter that directly influences the total amount of energy recovered and the overall system efficiency. Incomplete phase change due to a high cut-off temperature can lead to significant reductions in performance.

- (3)

- Statistical analysis confirmed that the HTF flow rate is the dominant factor influencing the overall heat transfer coefficient across all PCM phases (liquid, latent, and solid). In contrast, the effect of the HTF inlet temperature was found to be statistically insignificant.

- (4)

- The overall heat transfer coefficient is highly dependent on the PCM’s phase, following the order: Liquid > Latent > Solid. The coefficient in the liquid state (up to 0.863 kW/m2·°C) can be more than an order of magnitude greater than in the solid state (as low as 0.015 kW/m2·°C), highlighting the necessity of using phase-aware models for system design.

Analysis of the outside heat transfer coefficient revealed that the latent and solid phases dominate the discharge process. The coefficient in the solid phase was, on average, 56.4% lower than in the latent phase, indicating that conduction through the solid PCM is the primary performance bottleneck. These two phases should be the priority for design optimization.

The experimental data and derived heat transfer coefficients obtained in this work provide a crucial foundation for the design, modeling, and operational optimization of LHTES modules. These findings are particularly valuable for integrating such storage systems into P2H applications to support the transition to renewable energy. Future studies will extend this work to investigate the heat transfer characteristics of modules connected in series and parallel, as well as the long-term cycling stability and safety of BHO under practical operating conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.O. and J.H.P.; methodology, J.-W.K.; software and validation, T.H.S., J.-H.L. and J.H.P.; formal analysis, J.-W.K.; investigation, J.-W.K.; resources, S.J.O.; data curation, T.H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-W.K.; writing—review and editing, S.J.O.; visualization, J.-W.K.; supervision, J.H.P.; project administration, S.J.O.; funding acquisition, S.J.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korean Institute of Energy Technology Evaluation and Planning (KETEP), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy (MOTIE) (grant No. 20226210100050).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. The 11th Basic Plan for Long-Term Electricity Supply and Demand (2024–2038); Public Notice No. 2025-169; MOTIE: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2025; pp. 1–82.

- Wang, W.; Xie, X. Flexible Heat and Power Load Control of Heating Units Based on Energy Demand-Supply Balance. SSRN Electron. J. 2024, 4940421, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauko, H.; Braekken, A.; Askeland, M. Flexibility through Power-to-Heat in Local Integrated Energy Systems with Renewable Electricity Generation and Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage. Energy 2024, 313, 134017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.M.; Khudhair, A.M.; Razack, S.A.K.; Al-Hallaj, S. A Review on Phase Change Energy Storage: Materials and Applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2004, 45, 1597–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Tyagi, V.V.; Chen, C.R.; Buddhi, D. Review on Thermal Energy Storage with Phase Change Materials and Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 318–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadheeswaran, S.; Pohekar, S.D. Performance Enhancement in Latent Heat Thermal Storage System: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 2225–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyenim, F.; Hewitt, N.; Eames, P.; Smyth, M. A Review of Materials, Heat Transfer and Phase Change Problem Formulation for Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage Systems (LHTESS). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chueh, C.-C.; Hung, S.-C. Numerical Investigation of Melting of a Phase-Change Material in H-type Shell Tubes. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolka, P.; Przybylinski, T.; Kwidzinski, R.; Lackowski, M. Investigation of low-temperature phase change material (PCM) with nano-additives improving thermal conductivity for better thermal response of thermal energy storage. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 66, 103821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, S.; Khan, S.-Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Kumar, M.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Investigation and optimal design of partially encapsulated metal foam in a latent heat storage unit for buildings. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukram, T.-A.; Daniel, J. Performance evaluation of a novel cement brick filled with micro-PCM used as a thermal energy storage system in building walls. J. Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, B.K.; Sistla, V.S. Inorganic Salt Hydrate for Thermal Energy Storage Application: A Review. Energy Storage 2021, 3, e212. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Ness, R.V.; Chavez, R., Jr.; Banerjee, D.; Muley, A.; Stoia, M. Experimental Analysis of Salt Hydrate Latent Heat Thermal Energy Storage System with Porous Aluminum Fabric and Salt Hydrate as Phase Change Material with Enhanced Stability and Supercooling. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2021, 143, 041801. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Duan, Z.; Chen, D.; Xie, Y.; Cao, X.; Wang, J. Sodium acetate trihydrate-based composite phase change material with enhanced thermal performance for energy storage. J. Energy Storage 2021, 34, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, L.; Cao, X.; Yang, X. Experimental studies on the supercooling and melting/freezing characteristics of nano-copper/sodium acetate trihydrate composite phase change materials. Renew. Energy. 2016, 99, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P.; Miro, L.; Sole, A.; Barreneche, C.; Sole, C.; Martorell, I.; Cabeza, L.-F. Corrosion of metal and metal alloy containers in contact with phase change materials (PCM) for potential heating and cooling applications. Appl. Energy. 2014, 125, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar-Serradilla, V.; Silva, R.; Satchi, C.-S.; Lopez-Pedrajas, D.; Pato-Doldan, B. Multiphysics modeling and economic design of a high-temperature phase-change-material thermal energy storage, for saturated steam generation industrial applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 279, 127678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, C.Y. Experimental Investigation of Barium Hydroxide Octahydrate as Latent Heat Storage Materials. Sol. Energy 2019, 177, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenisarin, M.; Mahkamov, K. Salt Hydrates as Latent Heat Storage Materials: Thermophysical Properties and Costs. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 145, 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incropera, F.P.; DeWitt, D.P. Fundamentals of Heat and Mass Transfer, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 550–553. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).