Abstract

This paper examines the sustainability of photovoltaic (PV) panel recycling through a case study in Greece. It traces the evolution of PVs and outlines the main construction characteristics, emphasizing that although PV systems reduce greenhouse gas emissions, they also generate substantial end-of-life (EoL) waste containing both valuable and potentially hazardous materials. The study estimates Greece’s annual PV waste generation and evaluates its environmental, social, and economic impacts. It focuses on advanced disassembly and recycling methods by PV types and calculates material-recovery rates. Using national installation data from 2009–2023, the analysis quantifies the potential mass of recoverable materials and assesses the sustainability of PV recycling in terms of environmental protection, public health, and economic feasibility. Results show high recovery rates: silicon (85%), aluminum (100%), silver (98–100%), glass (95%), copper (97%), and tin (32%). Although current recycling economics remain challenging, the environmental and health benefits are significant. This research contributes to the existing literature by providing the first detailed quantification of recoverable raw materials embedded in Greece’s PV stock and by highlighting the need for technological innovation and supportive policies to enable a circular and sustainable solar economy.

1. Introduction

Renewable energy sources (RES) are at the core of global strategies for mitigating climate change and achieving energy security. Among them, solar energy, particularly through PV systems, has evolved into one of the most mature and widely deployed technologies for producing electricity without direct emissions. PVs transform sunlight into electricity using semiconductor materials, enabling clean, decentralized, and scalable energy generation. Yet, while PV systems substantially reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during operation, their environmental footprint extends across their entire life cycle. Once PV modules reach their end of life (EoL), typically after 25–30 years, they become a rapidly growing waste stream containing valuable but also potentially hazardous materials [1,2]. If improperly managed, this waste can undermine the environmental integrity of renewable energy systems and hinder the transition toward a circular economy [3].

The global scale of PV deployment highlights the urgency of addressing EoL management. Global installed capacity surpassed 239 GW in 2023, with China leading expansion, while Europe added a record 56 GW that year alone [4,5]. Forecasts predict that the global PV recycling market will grow from approximately USD 384–492 million in 2025 to over USD 900 million–2.5 billion by 2030–2034 [6,7,8]. This anticipated growth reflects not only the increasing quantity of aging PV systems but also the recognition that recycling is an essential phase of the PV life cycle, supporting resource efficiency and circular-economy objectives.

At the European level, renewable energy deployment and decarbonization policies have accelerated under the European Green Deal, which aims for climate neutrality by 2050 and at least 42.5% renewable energy share by 2030. PV installations are expanding rapidly across EU Member States, supported by national energy and climate plans (NECPs). However, the corresponding growth of PV waste represents a new category of large electrical and electronic equipment waste (WEEE) requiring coordinated infrastructure and regulation. According to Kastanaki and Giannis [5], the EU-27 is expected to generate between 14.3 and 18.5 million tons of PV waste by 2050, with recoverable material value estimated at USD 22–27 billion. Their work highlights that the establishment of economically viable recycling industries in Europe depends on the timely development of EoL systems and reliable projections of material flows. The Renewable Energy and WEEE Directives provide the legislative backbone for EoL PV management, mandating a minimum recycling rate of 80% and a recovery rate of 85% of module weight. Nonetheless, practical implementation remains uneven, and several authors point to significant infrastructure gaps and regulatory fragmentation across Mediterranean and southeastern European countries [9,10].

In the Mediterranean region, where solar irradiance is among the highest in Europe, PV expansion has been remarkable since 2007. Spain, Italy, and Greece experienced rapid growth during 2009–2013 due to generous feed-in-tariff programs and government incentives. As these early-generation systems approach obsolescence, the region faces a looming wave of PV waste. Diez-Suárez et al. [9] emphasized that by 2030–2050, Mediterranean countries will generate hundreds of thousands of tons of PV waste, primarily from crystalline silicon modules installed during the 2000s. The authors underline that recycling these systems is essential not only to prevent environmental pollution but also to recover critical raw materials such as silicon, silver, and aluminum, contributing to a circular and resource-efficient solar economy.

Greece exemplifies this trajectory. National installed PV capacity expanded from only 1 MW in 2000 to 6.2 GW in 2023, with particularly rapid growth between 2009 and 2013 [1]. Following a period of stagnation during the 2014–2018 economic crisis, the Greek solar market has recovered strongly, driven by cost reductions and updated climate policy targets. However, as first-generation modules near the end of their designed lifetime, Greece will soon face a substantial influx of decommissioned PV panels. Several studies [3,11] emphasize that planning sustainable recycling infrastructure now is essential to manage this upcoming waste stream responsibly. Sagani et al. [11] analyzed building-integrated PV systems in Athens and confirmed both the economic viability and environmental benefits of solar energy under Greek conditions, but also stressed the need to include EoL impacts in life cycle assessments (LCA) to ensure full sustainability.

The technical and environmental complexity of PV recycling stems from the diversity of module designs and materials. PV technologies are broadly divided into three generations: (i) first-generation crystalline silicon (c-Si), including monocrystalline (Mono-Si) and polycrystalline (Poly-Si); (ii) second-generation thin-film modules such as amorphous silicon (a-Si), cadmium telluride (CdTe), and copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS); and (iii) third-generation and emerging technologies such as organic and perovskite solar cells [3,9,12]. Crystalline silicon dominates global and Greek markets, accounting for over 85% of installations. These modules typically comprise about 70–75% glass, 10–18% aluminum, 5–6% polymers (mainly ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA)), 3–5% silicon, and small fractions of silver, copper, lead, and tin [2,10]. Thin-film modules, while containing higher shares of glass and smaller material quantities overall, include rare and toxic metals such as indium, gallium, cadmium, and tellurium, which require specialized handling during recycling [3].

The environmental significance of proper EoL treatment has been extensively documented. The International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) projected that global PV waste will increase from 45,000 tons in 2016 to 8 million tons by 2030 and up to 78 million tons by 2050 [13]. The International Energy Agency (IEA) further identified performance degradation, junction-box failures, and glass breakage as the main causes of premature retirement [14]. Improper disposal risks leaching of heavy metals and polymer degradation byproducts, posing hazards to ecosystems and human health [3,9]. Conversely, efficient recycling allows the recovery of valuable resources, aluminum, glass, silicon, copper, and silver, while reducing the energy demand and emissions associated with virgin material production [15].

Recent advances in PV recycling technologies reveal both progress and challenges. Recycling processes are typically classified as mechanical, thermal, chemical, or solvothermal/hybrid. Mechanical separation enables recovery of glass and aluminum frames, achieving rates of up to 95% and 100%, respectively [10]. Thermal processes, often involving pyrolysis at 450–600 °C, decompose encapsulants (EVA) and release intact silicon wafers, recovering about 85% of silicon [16]. However, traditional thermal methods can cause wafer breakage due to gas buildup, prompting the development of hybrid processes such as solvothermal swelling with thermal decomposition (SSTD), which combine controlled heating with organic solvents to preserve wafer integrity [17].

Innovative recovery methods have emerged from both chemical and bioelectrochemical research. Kanellos et al. [2] demonstrated the use of microbial fuel cell (MFC) technology for recovering silver from hydrometallurgically treated PV waste, achieving up to 100% recovery with high purity while simultaneously removing other metals. Such bioelectrochemical systems (BES) represent promising low-energy alternatives for metal recovery within circular-economy frameworks. In parallel, Pavlopoulos et al. [16] investigated the stabilization of EoL PV residues using Portland cement, confirming through toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (TCLP) tests that solidification effectively prevents heavy-metal release, ensuring safe disposal when recycling is not feasible.

Thin-film recycling has also received attention, particularly for managing toxic constituents. Savvilotidou et al. [3] examined amorphous silicon and CIGS panels, developing chemical treatment methods using lactic and sulfuric acids that dissolve EVA and recover critical materials such as indium and gallium while minimizing hazardous emissions. Their findings align with recent circular-economy analyses showing that even partial recovery of these elements can offset environmental impacts and improve resource efficiency. Similarly, Suarez et al. [9] highlighted the urgent need for harmonized recycling systems across Mediterranean countries to prevent the loss of valuable materials and to mitigate pollution risks from cadmium and lead compounds.

Beyond technical considerations, the sustainability of PV recycling depends on economic and policy dimensions. Recycling costs for crystalline modules currently range between USD 0.8–1.7 per kg, compared with USD 0.1–0.6 per kg for landfill disposal [7,10]. Despite the unfavorable short-term economics, several studies emphasize that the long-term environmental and health benefits outweigh costs, especially when accounting for energy savings and avoided raw material extraction [9,10]. The European Commission’s Ecodesign and Energy Efficiency Directives already provide a framework for improving product circularity [18], and extending these principles to PV modules could further reduce lifecycle impacts. Similar lessons emerge from other sectors: for example, research on upcycling agricultural waste [19] and wind-turbine recycling in Greece [20] demonstrates how industrial symbiosis and circular design can transform waste into new resources, enhancing both environmental and economic performance. These cross-sectoral analogies underscore that PV recycling should not be viewed in isolation but as part of an integrated circular economy.

The literature also reveals an emerging convergence between technological innovation and life-cycle thinking. Studies stress the need for standardized LCA frameworks that capture rapidly evolving materials and architectures [10,21]. Likewise, research on advanced manufacturing and 3D printing for sustainable product design shows how modularity and repairability can enhance resource efficiency and resilience during crises [22]. Together, these insights point toward a broader paradigm shift, from energy transition to material circularity, where renewable technologies must also be renewable in their material flows.

Given this context, Greece faces both a challenge and an opportunity. Current domestic infrastructure for PV waste management remains limited, though integration with the emerging European recycling network is under discussion. The national implementation of the EU WEEE Directive mandates producer responsibility for collection and recycling, but the system’s effectiveness depends on developing dedicated facilities, economic incentives, and public–private collaboration. Recent studies emphasize that linking PV recycling with local industries, such as glass, aluminum, and metallurgical sectors, could yield significant economic and employment benefits while closing material loops at the regional level [5,9].

Building upon these insights, the present study investigates the sustainability of PV panel recycling in Greece through a combined technical, environmental, and economic assessment. It (i) analyzes the evolution and construction of photovoltaic technologies to identify their material compositions; (ii) reviews advanced recycling and recovery methods (mechanical, thermal, chemical, solvothermal, and biological) and their recovery rates; (iii) quantifies, using national installation data (2009–2023), the potential weight of recoverable raw materials; and (iv) evaluates the sustainability of recycling across three key dimensions; environmental protection, public health, and economic feasibility. The overarching aim is to determine whether PV recycling in Greece is currently sustainable and to identify the technological and policy measures required to make it so. Ultimately, the findings aim to support national and European strategies that enable responsible PV waste management, enhance resource efficiency, and advance a truly circular and sustainable solar economy.

2. Methodology

This study aims to quantify the potential quantities of materials recoverable from PV panels installed in Greece and to evaluate the sustainability of their recycling. All data were obtained through the Greek Center for Renewable Energy Sources (CRES) to ensure accuracy under local economic, environmental, and technological conditions. The methodological framework follows a stepwise, data-driven approach based on national installation statistics, as outlined below:

All assumptions regarding panel characteristics, material composition, recovery efficiencies, and installation data are explicitly detailed in the following steps to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility.

- Identification of annual installed capacity: The total PV capacity installed each year in Greece was collected from CRES records and verified with data from national and European statistical sources.

- Determination of the average panel power per year: For each year, the typical power rating of the most widely used PV modules was identified to reflect prevailing market technologies and efficiency levels. The annual values of average panel power were obtained directly from the CRES database, which documents the PV modules most commonly installed in Greece each year, and were cross-checked using manufacturer datasheets. This approach ensures that the selected values represent actual market conditions and the dominant technologies used during 2009–2023.

- Estimation of the number of panels installed annually: The annual installed capacity (MW) was divided by the average power output per module (kW) to calculate the number of panels installed each year.

- Establishment of the weight-to-power ratio: The ratio of panel weight to power rating (kg/kW) was determined for each year to represent technological evolution and improvements in design efficiency. These ratios were derived using CRES market data and corresponding datasheets of the most widely deployed panels each year, ensuring consistency with real-world module characteristics.

- Calculation of the total mass of PV panels installed annually: The number of panels was multiplied by the average panel weight to estimate the total mass of PV panels (in tons) installed each year in Greece.

- Determination of raw-material composition: Based on the typical composition of crystalline-silicon PV modules, approximately 76% glass, 10% plastic (mainly EVA), 8% aluminum, 5% silicon, and 1% other metals (silver, copper, tin, etc.), the corresponding mass fraction of each material per ton of PV waste was calculated. The composition percentages of silver, copper, and tin were based on published characterizations of crystalline-silicon modules [3,6,10], which consistently report small but significant fractions of these metals in PV panels.

- Estimation of recoverable materials: Recognized recovery efficiencies were applied to each material: aluminum (100%), glass (95%), silicon (85%), copper (97%), silver (98–100%), and tin (32%). The annual quantities of recoverable materials were obtained by multiplying these recovery factors by the material content of the installed panels.

The analysis covers the Greek national territory and the period 2009–2023, corresponding to the most significant phase of PV deployment. The calculations provide a theoretical estimate of the quantities of recoverable materials assuming complete recycling of all panels installed in each year once they reach the end of their 25–30-year operational lifespan. This stepwise framework also functions as a forward-projection model: because each installation year is mapped to a representative lifespan of 25–30 years, the calculated material flows represent predicted end-of-life waste quantities expected to arise in future decades based on existing installation data. Thus, the methodology provides not only a retrospective quantification but also a theoretical prediction of future material volumes embedded in Greece’s PV stock.

All data were organized and processed using Microsoft Excel for statistical computation and chart generation. Annual capacity data and module specifications were cross-checked for consistency, and proportional formulas were applied to derive the number of panels, total installed mass, and recoverable material quantities.

The calculations are based on the average characteristics of crystalline-silicon panels, which account for more than 95% of the Greek PV market. Thin-film technologies were excluded due to their limited market share and differing chemical composition. The results represent theoretical potential values and do not account for collection, transport, or processing losses. Recovery rates were assumed constant, reflecting typical industrial-scale performance.

This methodology provides a transparent and reproducible framework for linking national installation data with material composition and recycling efficiencies to estimate the potential volumes of recyclable materials within Greece’s PV stock. The resulting dataset forms the basis for the subsequent assessment of environmental, public-health, and economic sustainability.

3. Results

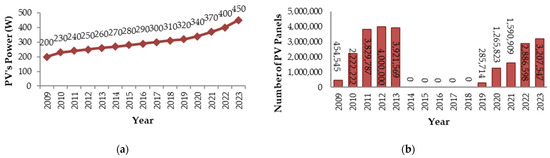

Figure 1a illustrates the evolution of the power rating of the most common PV modules installed in Greece between 2009 and 2023. Module capacity increased steadily from 200 W in 2009 to 450 W in 2023, reflecting technological improvements and global trends toward higher-efficiency crystalline-silicon panels. Considering these data together with national installation records, the annual number of PV panels installed (Figure 1b) shows a sharp rise between 2009 and 2013, reaching about 4 million units in 2012, the highest annual addition. This rapid growth corresponds to the implementation of generous feed-in-tariff schemes and renewable-energy incentives. From 2014 to 2018, installations stagnated almost completely due to the national economic crisis and suspension of feed-in-tariff programs. The very low installation figures during this period reflect actual market conditions rather than missing or unavailable data. After 2019, the market recovered strongly, culminating in approximately 3.2 million panels installed in 2023, driven by renewed investment and declining system costs.

Figure 1.

(a) Evolution of the power rating of the most commonly used photovoltaic panels in Greece (2009–2023); (b) Number of photovoltaic panels installed annually in Greece, derived from national capacity data (2009–2023).

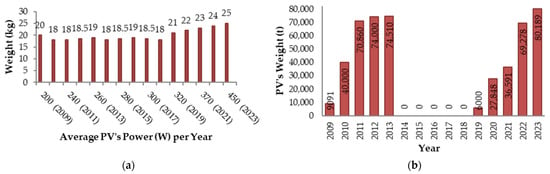

The relationship between panel weight and power output (Figure 2a) reveals gradual design optimization. While module power nearly doubled, average weight increased modestly from 20 kg to 25 kg per panel, showing that modern modules achieve higher output without proportional mass increases. Based on these parameters, the annual total weight of PV panels installed in Greece (Figure 2b) increased from around 9000 tons in 2009 to about 80,000 tons in 2023. The highest yearly additions occurred in 2012–2013 and again from 2021 onwards, paralleling policy-driven growth.

Figure 2.

(a) Average weight-to-power ratio of PV panels (kg/kW) indicating design efficiency improvements over time; (b) Total weight of PV panels installed per year in Greece (2009–2023).

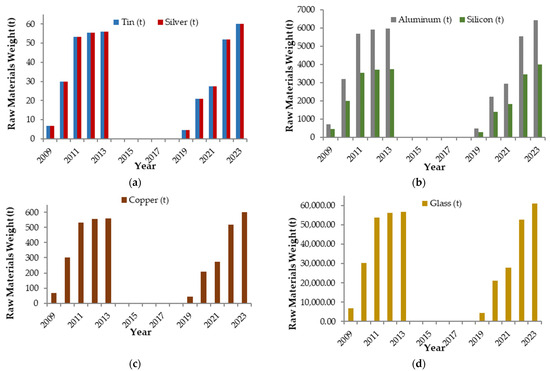

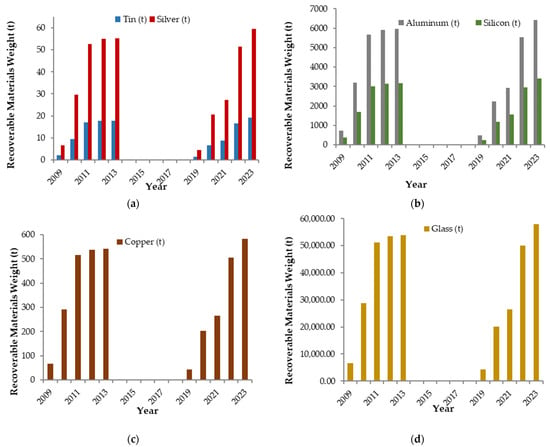

Using the mean material composition of crystalline-silicon panels, 76% glass, 10% plastic (EVA and backsheet polymers), 8% aluminum, 5% silicon, and 1% other metals, the total content of key raw materials was estimated (Figure 3a–d). Glass and aluminum dominate the mass, whereas silicon, copper, silver, and tin appear in smaller yet economically valuable quantities. Applying representative recovery efficiencies (aluminum 100%, glass 95%, silicon 85%, copper 97%, silver 98–100%, tin 32%), the theoretical weight of recoverable materials per installation year was determined (Figure 4a–d). The results confirm that aluminum, glass, and silicon constitute the largest potential recovery streams.

Figure 3.

(a) Estimated annual quantities of tin and silver contained in the PV panels installed in Greece; (b) Estimated annual quantities of aluminum and silicon contained in installed PV panels; (c) Estimated annual quantity of copper contained in installed PV panels; (d) Estimated annual quantity of glass contained in installed PV panels.

Figure 4.

(a) Recoverable quantities of tin and silver per installation year; (b) Recoverable quantities of aluminum and silicon per installation year; (c) Recoverable quantities of copper per installation; (d) Recoverable quantities of glass per installation year; all calculated by applying standard industrial recovery efficiencies.

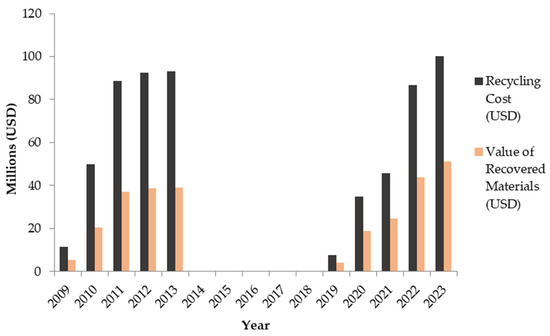

The data indicate that in 2023 alone, recycling could recover approximately 60 t of silver, 19 t of tin, 583 t of copper, 6415 t of aluminum, 3408 t of silicon, and 57,896 t of glass. These values demonstrate the magnitude of secondary resources embedded in Greece’s PV stock. Among these, glass and aluminum recovery provide the greatest mass flow, while silver, though present in much smaller amounts, offers the highest unit value. Figure 5 compares estimated recycling costs (800–1700 USD per ton, average ≈ 1250 USD/t) with the potential value of recovered materials, using 2024 market prices (Table 1). Despite strong environmental and social justification, current economics remain marginal: in 2023, total recycling costs exceeded material revenues, highlighting the need for cost-reducing technological innovation and supportive policy instruments.

Figure 5.

Comparison between total recycling cost and market value of recovered materials (2009–2023), using the average recycling cost of 1250 USD/t and 2024 material prices.

Table 1.

Market value of recoverable materials used to estimate economic returns from PV-panel recycling (values in USD/t).

The recycling-cost values shown in Figure 5 (800–1700 USD/t) refer to processing-stage costs only and do not include transportation, collection, or sorting expenses, which vary significantly by region. Material values correspond to average 2024 market prices and are not adjusted for potential future price fluctuations, which may affect economic feasibility.

From an environmental standpoint, the results emphasize that PV recycling offers substantial resource-efficiency and pollution-prevention benefits. Recovery of aluminum and silicon prevents energy-intensive production of primary materials, while glass recycling reduces landfill volumes. Both environmentally and economically, recycling remains most advantageous when high-value metals (Ag, Cu) are efficiently separated and purified. Overall, these findings establish a comprehensive quantitative baseline for evaluating Greece’s PV-recycling potential over 2009–2023 and provide the foundation for future sustainability-oriented planning and policy development.

4. Discussion

The analysis confirms that Greece’s PV expansion has generated a substantial EoL material stock whose sustainable management will soon become a national priority. The rapid growth during 2009–2013 and the renewed installation wave after 2019 mirror trends reported by Papamichail et al. [10] and Kastanaki and Giannis [5], who project that EU-27 PV waste could reach 14–18 million tons by 2050. In the Greek context, the cumulative material content of PV panels installed between 2009 and 2023 includes approximately 371,000 tons of glass and 39,000 tons of aluminum, demonstrating both the environmental opportunity and logistical challenges involved in closing material loops within the solar sector.

4.1. Environmental and Technological Implications

Athanailidis et al. [15] performed a LCA of PV recycling in Greece and found that integrating recovery processes into the module life cycle could reduce overall environmental burdens by 30–40%, consistent with the present results showing major gains from aluminum and glass reuse. Theocharis et al. [23] advanced this understanding by experimentally validating an integrated thermal and hydrometallurgical process capable of recovering high-purity silicon and silver under moderate conditions (550 °C delamination followed by H2SO4/HNO3 leaching). Their results, showing quantitative recovery of Ag and Al and >80% Si purity, align closely with the recovery efficiencies applied in this study. Combining such processes with the microbial silver recovery route developed by Kanellos et al. [2], which achieved ~100% Ag recovery in bioelectrochemical cells, could drastically improve circularity and energy performance in future recycling plants.

The findings also correlate with Sagani et al. [11], who analyzed small-scale building-integrated PV systems in Greece and emphasized that EoL impacts can offset operational benefits if recycling is neglected. In contrast, the successful delamination and material reuse observed in other studies demonstrate that sustainable EoL management substantially enhances the net environmental profile of PV power [15,23]. Savvilotidou et al. [3] further highlighted that effective chemical treatment of thin-film CIGS and a-Si modules can mitigate cadmium and indium emissions, reinforcing the environmental necessity of controlled recycling even for minority technologies.

From a technological standpoint, the progressive increase in module efficiency observed in Figure 1a and the stable weight ratios (Figure 2a) indicate ongoing design optimization, reducing the mass of materials required per kW. This trend parallels European observations by Bozjagovic et al. [24], who noted that eco-innovation and lightweighting are essential to achieving EU Circular Economy Action Plan targets. However, while lighter modules ease installation, they also reduce absolute recoverable mass per unit capacity, challenging recyclers’ economies of scale.

4.2. Policy and Economic Perspectives

Economically, the results confirm the cost gap previously identified in recent studies, which reported recycling costs of 800–1700 USD/t versus landfill costs of 100–600 USD/t [16]. Although the cost–benefit ratio remains unfavorable, the long-term market outlook is positive. Analyses indicate that material-criticality pressures and policy mandates will soon render recovery economically necessary rather than optional [5,25]. Mediterranean nations are also expected to face a rapid increase in PV waste after 2030, underscoring the need for shared recycling infrastructures [9].

A comparative perspective across the European Union underscores the specific challenges faced by Greece. Leading Member States such as Germany, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands already generate sufficient annual PV-waste volumes to support economically viable, dedicated recycling facilities, often surpassing the minimum 20 kt/yr threshold identified as necessary for profitability [5,26,27]. These countries also benefit from early and robust implementation of the WEEE Directive, well-established national collection networks, and strong producer-responsibility enforcement, all of which help reduce processing costs and increase recovery efficiency [5]. Southern countries such as Italy and Spain occupy an intermediate position: although they have fast-growing PV markets and increasingly organized waste-collection systems, they still rely partially on general WEEE streams [28,29].

In contrast, Greece remains at an earlier stage of PV-waste accumulation and will reach the 20 kt threshold only after 2040 under conservative scenarios, as highlighted in the EU-wide analysis by Kastanaki and Giannis [5]. This delay limits the financial feasibility of establishing standalone PV-recycling plants domestically. Findings from recent EU-wide assessments emphasise that harmonised waste-management rules, strong WEEE-compliance mechanisms, and targeted recycling requirements are essential for developing circular-economy supply chains across the EU’s renewable-electricity infrastructure [30]. The absence of such structured incentives in Greece contributes to higher logistical costs, fragmented collection streams, and slower market formation for secondary materials [5,30].

In Greece, implementing producer-responsibility mechanisms under the EU WEEE Directive, together with subsidies and green-procurement schemes, could transform recycling into a viable industrial sector. Integrating hydrometallurgical and bio-electrochemical steps with energy recovery (e.g., combustion heat from EVA decomposition) can significantly reduce operational costs [10,23]. Additionally, coupling with existing metallurgical and glass industries could facilitate economies of scale, a strategy consistent with recent analyses of EU resource-efficiency networks [24]. Emerging artificial-intelligence and self-organizing frameworks could further enhance this transformation by enabling predictive waste-flow management, dynamic cost optimization, and real-time coordination across recycling networks, supporting a more adaptive and resilient circular economy [31].

4.3. Social and Health Dimensions

Public-health benefits observed in this study, reductions in toxic-metal exposure and improved air quality, echo the conclusions of other studies [3,16]. Preventing leachate from cadmium, lead, and tin components avoids soil and groundwater contamination, while minimizing open-pit mining reduces occupational health risks. These synergies demonstrate that PV recycling contributes to both environmental sustainability and social well-being in accordance with SDG 12 and SDG 13 [15].

4.4. Toward a Circular-Economy Framework

The circular-economy perspective connects PV recycling to broader industrial ecology paradigms [24]. Material-flow accounting and resource criticality assessments can guide national policies for renewable-energy technologies [25]. Technological pathways for urban mining of silver and silicon have been demonstrated [2,23]. Governance instruments essential for market uptake have also been identified [5,16]. Comparable advances in other sectors, such as the regeneration of renewable materials from agricultural by-products, highlight how waste valorization and closed-loop resource recovery are becoming central to sustainable manufacturing [19]. Integrating these insights shows that material recirculation is not technology-specific but a systemic approach requiring cross-sector collaboration.

Developing a complete recycling industry chain in Greece will require strengthening linkages between PV-recycling processes and existing domestic manufacturing sectors. Recovered glass, which represents the highest mass fraction of PV modules, can be readily absorbed by the flat-glass and packaging-glass industries, following practices already implemented in mature PV recycling markets where cullet from processed modules is reintegrated into industrial glass production [32]. Similarly, recovered aluminum fractions can be directed to national extrusion and metallurgical plants, consistent with established recycling workflows in Europe in which aluminum, copper, and semiconductor fractions feed downstream material industries [32]. In parallel, reverse-logistics analyses show that creating synergies with existing transportation hubs, metal-processing infrastructure, and glass-melting facilities can significantly reduce logistical costs and accelerate the emergence of circular supply chains for renewable-energy technologies [33]. Establishing these industrial connections would enhance material circularity, support domestic economic activity, and red.

4.5. Future Outlook

Building upon the technical feasibility shown in previous studies, Greece could pioneer pilot facilities combining thermal delamination, hydrometallurgical leaching, and microbial recovery within a unified process chain [2,23]. Incorporating data-driven planning tools would enable precise forecasting of EoL module flows [15,25]. Investment in such infrastructure would yield environmental returns that far exceed current economic costs, aligning national practice with EU Green Deal objectives. In conclusion, the quantitative analysis presented here establishes the magnitude of recyclable resources within Greece’s PV stock and, when interpreted alongside the cited literature, confirms that technological readiness and policy alignment can transform EoL modules from waste liabilities into strategic secondary-resource assets.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that photovoltaic recycling is both an environmental imperative and a strategic opportunity for sustainable resource management. Greece’s rapidly expanding PV stock already contains substantial quantities of recoverable materials, including glass, aluminum, silicon, copper, and silver, that can significantly offset raw-material extraction if efficient recovery systems are implemented. Recycling these materials prevents hazardous waste accumulation, conserves finite resources, and reduces the environmental burden associated with mining and primary production. While recycling technologies achieve high recovery efficiencies, their economic feasibility remains limited due to high operational and logistical costs. This imbalance underscores the need for coordinated action between policy, industry, and research to establish large-scale, cost-effective recycling infrastructure. Economic incentives, extended-producer-responsibility schemes, and technological innovation, particularly in hybrid thermal, chemical, and biological recovery processes, can bridge the gap between environmental value and financial viability. Moving forward, integrating PV recycling within national and European circular-economy frameworks will be essential to ensure long-term sustainability. The development of dedicated recycling facilities, transparent material-flow monitoring, and collaboration between manufacturers and recyclers will transform EoL PV modules from an environmental liability into a valuable secondary resource. By linking renewable energy production with responsible material recovery, Greece can serve as a model for a solar economy that is not only clean in operation but circular in design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira) and A.L.; methodology, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira) and A.L.; validation, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira), K.K. (Konstantinos Kalkanis) and G.V.; investigation, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira) and A.L.; resources, G.V.; data curation, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira); writing—original draft preparation, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira) and A.L.; writing—review and editing, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira), K.K. (Konstantinos Kalkanis) and G.V.; visualization, K.K. (Kyriaki Kiskira) and A.L.; supervision, K.K. (Konstantinos Kalkanis) and G.V.; project administration, G.V.; funding acquisition, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used for analysis originates from the Greek CRES and is available from the corresponding author, Kyriaki Kiskira, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the Greek CRES for providing the data utilized in this study. Their valuable support ensured the accuracy and contextual relevance of the findings under the specific economic, environmental, and technological conditions of Greece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| a-Si | Amorphous Silicon |

| BES | Bioelectrochemical Systems |

| CdTe | Cadmium Telluride |

| CIGS | Copper Indium Gallium Selenide |

| CRES | Center for Renewable Energy Sources |

| EoL | End of Life |

| EU | European Union |

| EVA | Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| MFC | Microbial Fuel Cell |

| Mono-Si | Monocrystalline |

| NECP | National energy and climate plan |

| Poly-Si | polycrystalline (Poly-Si); |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable energy sources |

| SSTD | Solvothermal Swelling with Thermal Decomposition |

| TCLP | Toxicity Characteristic Leaching Procedure |

| WEEE | Waste from Electrical and Electronic Equipment |

References

- Psomopoulos, C.S.; Kalkanis, K.; Chatzistamou, E.D.; Kiskira, K.; Ioannidis, G.C.; Kaminaris, S.D. End-of-Life Treatment of Photovoltaic Panels: Expected Volumes up to 2045 in the EU. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2437, 020084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellos, G.; Tremouli, A.; Tsakiridis, P.; Kakosimos, K.; Vakros, J.; Tekerlekopoulou, A.; Vayenas, D. Silver Recovery from End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels Based on Microbial Fuel Cell Technology. Waste Biomass Valor. 2024, 15, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvilotidou, V.; Antoniou, A.; Gidarakos, E. Toxicity Assessment and Feasible Recycling Process for Amorphous Silicon and CIS Waste Photovoltaic Panels. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SolarPower Europe. EU Market Outlook for Solar Power 2023–2027. 12 December 2023. Available online: https://www.solarpowereurope.org/insights/outlooks/eu-market-outlook-for-solar-power-2023-2027/detail (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Kastanaki, E.; Giannis, A. Energy Decarbonisation in the European Union: Assessment of Photovoltaic Waste Recycling Potential. Renew. Energy 2022, 192, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Shen, Y. Recent Progress in Silicon Photovoltaic Module Recycling Processes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, A.; Adish, T.; Kaustubh, P.; Zade, P.S. Review on Recycling of Solar Modules/Panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 253, 112151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Energy Institute. Solar PV Recycling Market to be Worth $2.7 bn by 2030. New Energy World. 13 July 2022. Available online: https://knowledge.energyinst.org/new-energy-world/article?id=127142 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Diez-Suárez, A.-M.; Martínez-Benavides, M.; Manteca Donado, C.; Blanes-Peiró, J.-J.; Martínez Torres, E.J. Recycling of Silicon-Based Photovoltaic Modules: Mediterranean Region Insight. Energies 2024, 17, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Jeguirim, M.; Argirusis, N.; Jellali, S.; Sourkouni, G.; Argirusis, C.; Zorpas, A.A. End-of-Life Management and Recycling on PV Solar Energy Production. Energies 2022, 15, 6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagani, A.; Mihelis, J.; Dedoussis, V. Techno-Economic Analysis and Life-Cycle Environmental Impacts of Small-Scale Building-Integrated PV Systems in Greece. Energy Build. 2017, 139, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiskira, K.; Kalkanis, K.; Coelho, F.; Plakantonaki, S.; D’onofrio, C.; Psomopoulos, C.S.; Priniotakis, G.; Ioannidis, G.C. Life Cycle Assessment of Organic Solar Cells: Structure, Analytical Framework, and Future Product Concepts. Electronics 2025, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Chen, W.-S.; Lee, C.-H.; Wu, J.-Y. Comprehensive Review of Crystalline Silicon Solar Panel Recycling: From Historical Context to Advanced Techniques. Sustainability 2024, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, J. Degradation Processes and Mechanisms of PV System Adhesives/Sealants and Junction Boxes. In Durability and Reliability of Polymers and Other Materials in Photovoltaic Modules; Yang, H.E., French, R.H., Bruckman, L.S., Eds.; Plastics Design Library, William Andrew Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanailidis, V.I.; Rentoumis, G.M.; Katsigiannis, A.Y.; Bilalis, N. Integration and Assessment of Recycling into c-Si Photovoltaic Module’s Life Cycle. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2018, 11, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlopoulos, C.; Kelesi, M.; Michopoulos, D.; Papadopoulou, K.; Lymperopoulou, T.; Skaropoulou, A.; Tsivilis, S.; Lyberatos, G. Management of End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels Based on Stabilization Using Portland Cement. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2022, 27, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Lai, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y. Nondestructive Silicon Wafer Recovery by a Novel Method of Solvothermal Swelling Coupled with Thermal Decomposition. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtsalas, A.C.; Papadatos, P.E.; Kiskira, K.; Kalkanis, K.; Psomopoulos, C.S. Ecodesign for Industrial Furnaces and Ovens: A Review of the Current Environmental Legislation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakantonaki, S.; Stergiou, M.; Panagiotatos, G.; Kiskira, K.; Priniotakis, G. Regenerated Cellulosic Fibers from Agricultural Waste. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2430, 080006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, K.; Vokas, G.; Kiskira, K.; Ioannidis, G.C.; Psomopoulos, C.S. Investigating the Sustainability of Wind Turbine Recycling: A Case Study—Greece. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2024, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.K.R.; Gemechu, E.; Thakur, U.; Shankar, K.; Kumar, A. Life Cycle Assessment of High-Performance Monocrystalline Titanium Dioxide Nanorod-Based Perovskite Solar Cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, K.; Kiskira, K.; Papageorgas, P.; Kaminaris, S.D.; Piromalis, D.; Banis, G.; Mpelesis, D.; Batagiannis, A. Advanced Manufacturing Design of an Emergency Mechanical Ventilator via 3D Printing—Effective Crisis Response. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, M.; Pavlopoulos, C.; Kousi, P.; Hatzikioseyian, A.; Zarkadas, I.; Tsakiridis, P.E.; Remoundaki, E.; Zoumboulakis, L.; Lyberatos, G. An Integrated Thermal and Hydrometallurgical Process for the Recovery of Silicon and Silver from End-of-Life Crystalline Si Photovoltaic Panels. Waste Biomass Valor. 2022, 13, 4027–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Galović, M.; Kuprešak, J.; Bošnjaković, T. The End of Life of PV Systems: Is Europe Ready for It? Sustainability 2023, 15, 16466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iseri, F.; Iseri, H.; Iakovou, E.; Pistikopoulos, E.N. A Circular Economy Systems Engineering Framework for Waste Management of Photovoltaic Panels. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 14986–14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Huda, N.; Behnia, M. Critical assessment of renewable energy waste generation in OECD countries: Decommissioned PV panels. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobra, T.; Wellacher, M.; Pomberger, R. End-of-life management of photovoltaic panels in Austria: Current situation and outlook. Detritus 2020, 10, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiano, A. Photovoltaic waste assessment in Italy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.D.; Alonso-García, M.C. Projection of the photovoltaic waste in Spain until 2050. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 196, 1613–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastanaki, E.; Giannis, A. Dynamic estimation of future obsolete laptop flows and embedded critical raw materials: The case study of Greece. Waste Manag. 2021, 132, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, V.; Gerolimos, N.; Leligkou, E.A.; Hompis, G.; Priniotakis, G.; Papakostas, G.A. Sustainable Swarm Intelligence: Assessing Carbon-Aware Optimization in High-Performance AI Systems. Technologies 2025, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsanakas, J.A.; van der Heide, A.; Radavičius, T.; Denafas, J.; Lemaire, E.; Wang, K.; Poortmans, J.; Voroshazi, E. Towards a circular supply chain for PV modules: Review of today’s challenges in PV recycling, refurbishment and recertification. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2020, 28, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovou, E.; Pistikopoulos, E.N.; Walzberg, J.; Iseri, F.; Iseri, H.; Chrisandina, N.J.; Vedant, S.; Nkoutche, C. Next-generation reverse logistics networks of photovoltaic recycling: Perspectives and challenges. Sol. Energy 2024, 271, 112329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).