Abstract

The large-scale integration of renewable energy has reduced power system flexibility and exacerbated supply–demand imbalances. In industrial parks, the combined variability of high energy-consuming industrial loads and photovoltaic (PV) generation further complicates the energy management challenge. Aiming to enhance the operational flexibility of industrial parks and mitigate supply–demand imbalances, this paper proposes a multi-time-scale stochastic energy management strategy that accounts for the uncertainty associated with PV generation. First, a conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) is employed to generate the representative PV generation scenarios, thereby enabling the modeling of PV generation uncertainty within the optimal dispatch model. Considering the coupling mechanisms and control characteristics of various regulation resources within the industrial park, a multi-time-scale dispatch model is developed. In the day-ahead dispatch phase, the operational costs are minimized by optimizing the production plans of industrial loads. In contrast, in the intraday phase, the more flexible measures, such as adjusting the tap positions of arc furnaces and controlling the charge/discharge of energy storage systems, are employed to smooth power fluctuations within the park. A case study validated the effectiveness of the proposed approach, demonstrating a 7.56% reduction in power fluctuations and a 4.34% decrease in daily operating costs. These results highlight the significance of leveraging industrial loads in park-level systems to enhance cost efficiency and renewable energy integration.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Context

With the increasing penetration of renewable energy, the inherent uncertainty and intermittency of its output have reduced the power system flexibility and posed significant challenges to maintaining energy balance [1,2]. Consequently, the secure operation of power systems requires more flexible resources [3,4,5]. In industrial parks, the high energy-consuming loads, characterized by large electricity demand, high load utilization, and flexible production processes, represent a promising source of dispatchable flexibility. By implementing the optimized energy management strategies for industrial parks that incorporate multiple high energy-consuming loads, it is possible to effectively mitigate the uncertainties associated with renewable generation and enhance the overall flexibility of system operations [6,7].

1.2. Literature Review

The production processes in energy-intensive industries involve a wide range of equipment, where regulating different sectors and production stages essentially depends on controlling the operational states of these devices. Recent research has placed growing emphasis on leveraging process-level flexibility and multi-energy system coordination to enhance large-scale demand response capabilities in such industries. The variational mode decomposition method has been applied to disaggregate net-load forecasts into frequency-specific components, which are subsequently assigned to high-energy loads and thermal units for coordinated peak-shaving, contributing to reduced renewable energy curtailment [8]. In the iron and steel sector, mixed-integer linear programming models integrate the scheduling of by-product gases, steam networks, and electricity procurement with flexible production processes-such as interruptible rolling lines, transferable air separation units, and shiftable electric arc furnaces-demonstrating the potential for significant peak-load reduction without compromising productivity [9,10]. In the cement industry, a robust min–max self-scheduling framework optimizes key sub-processes, including crushing, kiln-feed preparation, clinker production, and finish grinding, while utilizing silo storage to buffer variability and mitigate electricity price uncertainty [11]. Additionally, dynamic energy-balancing strategies for steel enterprises adopt rolling-horizon optimization and primal-dual interior-point algorithms to maintain operational equilibrium under real-time disturbances [12]. In summary, these research highlights the essential role that coordinated optimization between process flexibility and multi-energy systems plays in enabling scalable and reliable industrial demand response.

Recent advancements in optimization-based energy management have explored the integration of renewable energy, flexible industrial loads, and market mechanisms. These studies demonstrate that the coordinated scheduling strategies can effectively enhance system flexibility, economic performance, and renewable utilization. A bi-level model links industrial load scheduling with peak regulation requirements, employing a fuzzy AHP pricing strategy to incentivize participation [13]. photovoltaic (PV)-tracking configurations in hybrid microgrids are evaluated under different dispatch modes, showing the significance of environmental factors in renewable performance [14]. Process-aware demand response is enabled by modeling smelting stages and coordinating storage to absorb surplus renewable generation without extra investment [15]. A virtual power plant framework aggregates diverse assets for real-time ancillary services, significantly reducing costs while enhancing response accuracy [16]. To address renewable uncertainty, a hybrid PSO-Search-and-Rescue algorithm optimizes economic-emission dispatch, validated through scenario analysis and statistical testing [17]. Despite progress in coordinating diverse industries within industrial parks, existing energy management strategies remain limited in several key aspects. Most methods rely primarily on the on/off control of production equipment, failing to exploit the fine-grained regulation potential of devices with adjustable set-points, such as arc furnaces in steel plants. Furthermore, current research often fails to account for the uncertainty of internal PV generation and its impact on electricity trading costs.

1.3. Contributions and Organization

The existing stochastic optimization techniques fail in dealing with correlated renewable uncertainties and flexible industrial demand response. To address these challenges, this paper proposes a multi-time-scale stochastic energy management strategy for industrial parks that incorporates PV generation uncertainty. Therefore, the contributions can be summarized as: (1) PV generation scenarios are generated based on the conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN). (2) A multi-time-scale dispatch model that incorporates time-of-use (TOU) pricing and electricity trading costs is developed. (3) The flexibility of industrial loads is used to enhance park-level cost efficiency and renewable energy integration.

The remainder of this manuscript is structured as follows: Section 2 introduce the energy management framework. Then, Section 3 presents the CGAN-based PV scenario generation method. In Section 4, the multi-time-scale optimization model is established. A case study is conducted in Section 5. Finally, conclusions and discussions are provided in Section 6.

2. Energy Management Framework for Industrial Parks with PV Generation

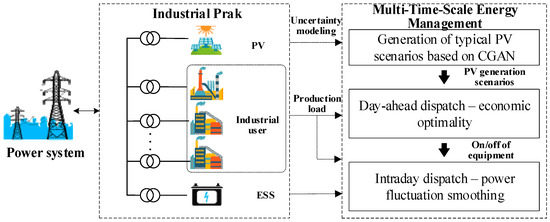

The overall framework of the proposed multi-time scale optimal dispatch strategy for industrial parks with PV generation is illustrated in Figure 1. Targeting parks that host typical energy-intensive industries such as cement and steel, this strategy is designed to enhance economic performance and minimize power fluctuations at the grid interconnection point. This is achieved by coordinating adjustable production loads with on-site energy storage systems (ESSs), while explicitly addressing PV generation uncertainty.

Figure 1.

Framework of multi-time-scale energy management framework for industrial parks.

The strategy consists of three main components: modeling of PV uncertainty, day-ahead energy management, and intraday energy management. A conditional generative adversarial network (CGAN) is used to generate representative PV generation scenarios, enabling accurate characterization of uncertainty. Based on these scenarios, a multi-time -scale optimization model is established to optimize the production scheduling and energy storage operations.

In the day-ahead dispatch phase, the model optimizes the on/off status of key industrial equipment. For steelworks, this includes electric arc furnaces and rolling mills. For cement plants, it includes crushers and grinders. The dispatch respects process constraints while improving the overall economic efficiency of the park. In the intraday dispatch phase, the strategy fine-tunes the energy management by adjusting the tap positions of electric arc furnaces and regulating the charge/discharge power of energy storage systems, ultimately aiming to reduce regulation costs and smooth power fluctuations at the grid interface.

3. CGAN-Based PV Generation Scenario

PV generation scenarios are typically generated using statistical methods such as time series analysis, scenario tree methods, and Markov chain models [18]. A key limitation of existing methods lies in their reliance on predefined statistical models of PV uncertainty. Although these models are trained on historical data to produce representative power scenarios, their inherent lack of expressiveness often allows them to capture only singular features of the generation data, failing to provide a comprehensive uncertainty representation. To address this, this paper introduces a CGAN-based approach for scenario generation. This method accurately learns the nonlinear mapping from forecasted conditions to actual power outputs and, by injecting random noise, produces a diverse and realistic set of PV scenarios that more reliably quantify uncertainty for optimal dispatch.

3.1. Conditional Generative Adversarial Network

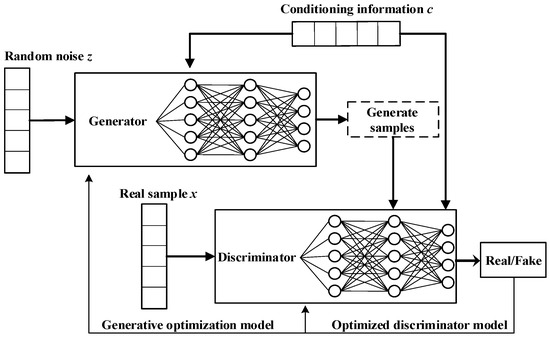

The generative adversarial networks (GAN) are a class of unsupervised deep learning models inspired by game theory. A GAN comprises two independent components: a generator and a discriminator. The generator learns the underlying distribution of real data to produce synthetic samples that closely mimic the authentic data. In turn, the discriminator, which functions as a binary classifier, is trained to differentiate between these generated samples and the real ones. In practice, both components are typically implemented as deep neural networks and are jointly optimized through an adversarial training process, which progressively enhances the realism of the generator outputs [19,20].

In contrast to conventional GANs, the CGAN incorporates a supervised mechanism by introducing additional conditional information, such as labels or predicted values, into the training process. This conditional guidance mitigates the excessive randomness inherent in standard GANs and enhances the goal-directed nature of sample generation [21].

As shown in Figure 2, the CGAN extends the standard framework by feeding the same conditional input to both the generator and the discriminator. This enables the generator to map random noise into realistic, condition-specific samples that closely match the target data distribution.

Figure 2.

Structure diagram of CGAN.

The CGAN is selected over traditional techniques like Gaussian mixture or Markov models due to its fundamental strength as a generative model. Unlike these methods, which often struggle to capture the complex, high-dimensional, and nonlinear nature of meteorological dependencies in PV output, the CGAN can directly learn and simulate the underlying data distribution. This allows it to generate realistic, high-resolution PV scenarios that are conditional on weather forecasts, a capability beyond the scope of the mentioned alternatives.

3.2. PV Scenario Generation Based on CGAN

In a CGAN, the PV generation forecast data is used as the conditional input c, while a sequence sampled from the distribution of power prediction errors serves as the random noise z. These two inputs are concatenated and fed into the generator. The generator, composed of specialized neural layers, produces PV generation scenarios that satisfy the conditional constraints, with the objective of making the generated samples as close as possible to real PV generation data. The discriminator evaluates both the generated and real samples, outputs a classification result, and provides feedback to update both the generator and discriminator through backpropagation. Its training goal is to maximize the ability to distinguish between real and generated samples. During training, the parameters of the generator and discriminator are updated iteratively and synchronously until the generator is able to produce PV scenarios that are indistinguishable from real data [22,23].

The overall training objective of CGAN is defined as:

where PG and PR are the generated PV power and the real PV power, respectively, V(PG, PR)is the difference between PG and PR, p(PG) is the distribution of the generated PV generation samples, pr(PG) is the distribution of the real data, E(∙) is the expectation over the data inside the parentheses, and D(∙) is the discriminator function.

To address common training challenges such as non-convergence and vanishing gradients and to ensure the generator effectively learns the distribution mapping for day-ahead scenarios, this study employs the Wasserstein distance to quantify the discrepancy between the distributions of real and generated samples [24]. The application of the Wasserstein distance in the CGAN framework is expressed as:

where ‖fD‖L ≤ 1 is a black-box function fD constructed by the discriminator, which satisfies 1-Lipschitz continuity with its derivative bounded by 1 in absolute value, and sup(∙) is the least upper bound.

By introducing a gradient penalty term ∇D(∙) for the discriminator function over its domain in Equation (1), the objective function of the CGAN can be reformulated using the Wasserstein distance:

where λ is the gradient penalty coefficient.

With the introduction of the Wasserstein distance, the discriminator not only distinguishes between real and generated samples but also accurately captures the distribution difference by computing the Wasserstein distance between sample sets. When this distance is sufficiently small, the generator can produce PV generation scenarios that reflect the characteristics of historical data distributions. After generating a large number of PV scenarios based on CGAN, a backward scenario reduction method is applied to select Ns typical scenarios. This approach ensures precise representation of PV uncertainty while reducing the computational complexity of optimal dispatch in high energy consumption industrial parks.

4. Multi-Time-Scale Optimization Model for Energy Management

As a widely adopted solution method, the scenario-based approach approximates the underlying probability distribution using a finite set of discrete scenarios. Accordingly, the PV scenarios generated by the CGAN are employed to solve the proposed stochastic optimization model. The proposed multi-time-scale energy management strategy explicitly addresses PV generation uncertainty. In the day-ahead stage, economic operation is optimized by scheduling the on/off status of flexible production equipment. In the intraday stage, power fluctuations at the grid interface are further mitigated through fine-grained adjustments of electric arc furnace tap positions and precise control of the energy storage system operation power [25].

4.1. Optimization of Day-Ahead Dispatch Phase

4.1.1. Model of Typical Flexible Loads

The flexible industrial loads can be broadly categorized into two types. The first type, represented by rolling mills in steel plants and crushers/grinders in cement plants, is regulated through on/off switching control. The second type, exemplified by electric arc furnaces in steel plants, enables continuous adjustment of power demand by varying transformer tap positions. Let Si(T) denote the operating status of flexible equipment. If the device i is operating during time period T, then Si(T) = 1; otherwise, Si(T) = 0. The power consumed during period T due to on/off scheduling of the equipment can then be expressed as:

where and are the power consumption of flexible production equipment during time period T and its rated power, respectively.

The power of electric arc furnace-type loads, which are regulated by adjusting transformer tap positions, can be expressed as:

where is the rated power of the flexible device when the tap position is at its initial level, and are the tap position of the device during time period T and the maximum tap level, respectively, and ci is the percentage change in power caused by tap position variation.

To achieve linearization of the model, the integer variables are introduced to reformulate the constraint [26]:

Therefore, the power consumption of flexible production loads such as electric arc furnaces can be expressed as:

4.1.2. Objective Function

The day-ahead dispatch model accounts for the impact of PV generation uncertainty and aims to minimize the total operating cost of the industrial park while ensuring the normal production:

where is the number of generated typical scenarios, is the probability of occurrence for scenario s, and are the electricity purchase price and selling price in time period T, respectively, and represent the purchased and sold power in scenario s during time period T, respectively, is the operation and maintenance cost of Flexible production load i, is the total number of time periods in a complete day-ahead scheduling cycle, △T is the time step, and is the set of flexible production loads.

4.1.3. Constraints

The power balance constraint is:

where is the output power of PV generation, is the total power consumption of all inflexible electrical loads in the system, and is the set of PV units.

In practical operation, the tap positions of electric arc furnace-type flexible devices cannot be changed by skipping levels:

To ensure the required production output, the total power consumed by flexible production equipment of during the scheduling period must meet the minimum energy demand:

where is the minimum energy demand of load i.

Additionally, considering the continuity of industrial processes, once a device is started, its operating duration must exceed the minimum required continuous working time:

where is the minimum continuous operating duration for a single operation of flexible production load i.

The frequent start–stop operations of production equipment may affect product quality and even impose stress on the power grid. Therefore, the number of start–stop cycles for production loads must be constrained, which can be expressed as:

where and represent the start-up state variable and the upper limit of the number of start-up operations for the unit, respectively, and and represent the shutdown state variable and the upper limit of the number of shutdown operations for the unit, respectively.

The upper limit on the number of devices that can be started up or shut down simultaneously at time T is given by:

where and are the upper limit on the number of devices that can be started up and shut down, respectively.

Given the potential coupling between industrial production processes, it is necessary to introduce additional operational constraints that coordinate the start-up and shutdown of flexible loads exhibiting sequential dependencies:

4.2. Optimization of Intraday Dispatch Phase

4.2.1. Objective Function

Building upon the day-ahead dispatch, the intraday scheduling further optimizes flexible but relatively small-capacity control resources within the industrial park, such as tap position adjustments of electric arc furnace loads and the charge and discharge power of energy storage systems, to smooth short-term power fluctuations while maintaining economic efficiency. This paper proposes a dual-objective optimization model that combines economical cost and power fluctuation reduction. For the solution process, the linear weighted method transforms the multi-objective problem into a single objective function through the introduction of a penalty term [26]. And the coefficient can be determined by the Delphi method and entropy weight method [27].

The optimization aims to minimize the total operational cost, comprising electricity transaction expenses, device control costs, and penalties for power fluctuations at the grid connection point, which can be expressed as:

where and are the charge/discharge power of energy storage devices within the industrial park and their operation and maintenance cost, respectively, is the set of energy storage devices in the industrial park, is the set of flexible loads, is the penalty coefficient, and Nt is the total number of time periods in a complete intraday scheduling cycle.

4.2.2. Constraints

The power balance constraint is:

where and is the power consumption of flexible production loads determined in the day-ahead dispatch phase.

The energy storage systems deployed in the industrial park are also subject to the following constraints:

where and are the lower and upper bounds of the charge/discharge power of energy storage systems, respectively, and are the energy level of storage at time t and the initial energy level, respectively, and are the lower and upper bounds of the energy level, respectively, and are the charging and discharging efficiencies of the energy storage system, respectively, and Δt is the time step, which must remain consistent throughout the model.

5. Case Study

5.1. Case Description

This study analyzes an industrial park comprising two representative energy-intensive industries: steel and cement, with the objective of validating the proposed multi-time scale dispatch strategy. The flexible resources include ten steel production units, eight cement production units, and an energy storage system. Key parameters of these flexible loads are provided in Table 1, with the steel units 1, 2, and 3 specified as electric arc furnace-type loads.

Table 1.

Parameter of flexible industrial loads.

In addition, the following process coupling constraints are introduced: the steels 1 and 4 must start simultaneously. The steel 6 can only start one hour after the steel 4 starts and the steel 10 must be shut down two hours after the steel 3 is turned off. The energy storage system in the park includes three types: the steel-side storage, cement-side storage, and PV-coupled storage. The detailed parameters are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of energy storage system.

5.2. PV Scenario Generation

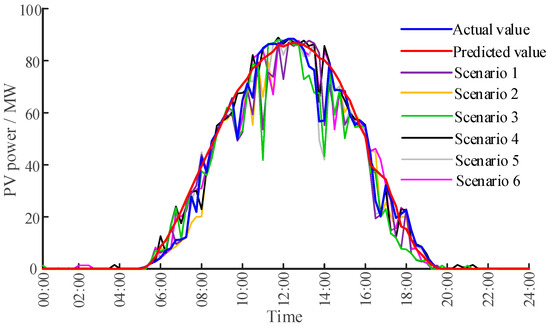

The rated capacity of PV generation in the industrial park is 105 MW. One year of day-ahead PV forecast data and actual measurements is used to construct the dataset, with 260 days selected as the training set. The data has a 15 min interval. The CGAN adopted in this study consists of a generator and a discriminator. Both the generator and the discriminator are optimized using the Adam optimizer. The CGAN model is trained using the PyTorch 2.3 framework. The epochs are set to 200, and the batch size is set to 128. The data are normalized to [−1,1] through linear transformation. After training, the forecast and actual PV data from a randomly selected day in the test set are used for performance analysis. The trained generator receives both the day-ahead forecast and sampled noise as input, producing 300 equally probable scenarios. A backward scenario reduction method is then applied to extract six representative PV generation scenarios [28].

Since the actual PV generation on the target day is unknown during the day-ahead dispatch phase, it is used as a benchmark to assess the accuracy of the proposed scenario generation method compared to deterministic forecasting. The six typical PV scenarios generated by the CGAN and backward reduction method are shown in Figure 3, and their associated probabilities are listed in Table 3. The results indicate that the generated scenarios closely follow the actual output trends and provide a more accurate representation of PV uncertainty.

Figure 3.

PV generation scenarios.

Table 3.

Probability of different PV scenarios.

5.3. Comparative Analysis of Energy Management Strategies

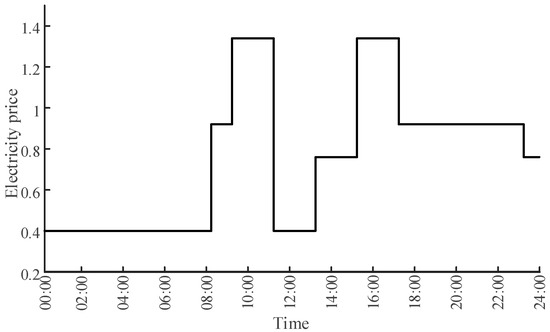

The TOU pricing mechanism adjusts electricity prices based on the operational status of the power system, providing price signals to guide users in optimizing their electricity consumption and activating demand-side flexibility. In this study, the TOU price curve is adopted to guide electricity usage behavior of industrial loads, as shown in Figure 4. Considering the presence of PV generation and energy storage systems within the industrial park, electricity may also be sold back to the grid. Accordingly, the electricity selling price is set at 50% of the purchase price shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

TOU price curve.

The day-ahead dispatch interval is set to 1 h with , and the intraday dispatch interval is 15 min with . The operation and maintenance cost of controllable production equipment in the industrial park is denoted by , that of the energy storage system by , and the penalty coefficient for power fluctuations by . All simulations are carried out in MATLAB 2021a, and the optimization models are solved using the Gurobi 12.0. The tolerance and MIP gap are both set as 10−4. In addition, the max time is set as 120 s. To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed multi-time scale energy management strategy, four strategies are compared: Strategy 1 aims for economic optimality and only schedules the start and stop of flexible loads in the day-ahead stage. Strategy 2 builds upon Strategy 1 by incorporating intraday control of electric arc furnace tap positions and energy storage systems. Strategy 3 performs multi-time-scale scheduling based on day-ahead PV forecasts but does not consider PV uncertainty. Strategy 4 is the method proposed in this paper, which integrates PV uncertainty and coordinates multiple resources within a multi-time-scale framework.

The operational costs of the industrial park under different dispatch strategies are shown in Table 4. The results indicate that strategies 2, 3, and 4, which implement multi-time-scale optimization through both day-ahead and intraday dispatch, result in significantly lower total costs compared to strategy 1, which only considers day-ahead optimization. Strategies 2 and 4, which account for PV uncertainty, achieve better economic performance than strategy 3, which is based solely on deterministic forecasts. The operation and maintenance costs of industrial loads are the same across all four strategies. This is because the industrial park must meet the minimum energy requirement for normal production, and under the objective of economic optimality, the total energy consumption of these devices remains unchanged.

Table 4.

Operational costs under different energy management strategies.

In addition, the proposed strategy 4 yields the same total operating cost as strategy 2. This is attributed to the small penalty coefficient assigned to the power smoothing term, which ensures that economic efficiency is prioritized while smoothing power fluctuations is treated as a secondary goal. Table 5 presents the impact of different penalty coefficients on the total operational cost. As the penalty increases, the total cost rises accordingly, reflecting a shift in the dispatch strategy toward mitigating power fluctuations within the industrial park.

Table 5.

Operational costs under different penalties.

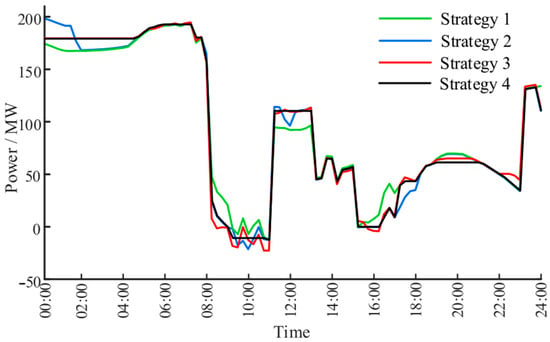

Figure 5 illustrates the transmission power on the tie line between the industrial park and the external grid under different energy management strategies. The results show that the proposed strategy 4 significantly reduces power fluctuations compared to other strategies, especially during the period from 08:00 to 13:00. Combining the observations from Figure 5 and Table 4, it can be concluded that strategy 4 effectively smooths the power fluctuations on the tie line while maintaining optimal economic performance. In detail, the results show a 7.56% reduction in power fluctuations of Strategy 4.

Figure 5.

Transmission power with different strategies.

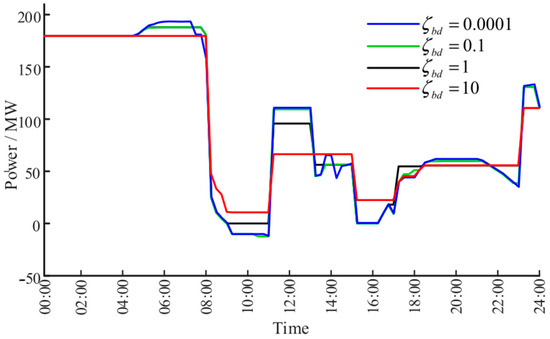

Figure 6 depicts the impact of different penalty coefficients on the transmission power fluctuations under strategy 4, showing that the fluctuations decrease as the penalty coefficient increases. Considering both economic efficiency and power smoothing, the penalty coefficient is set to 0.0001 in this study.

Figure 6.

Transmission power with different penalties.

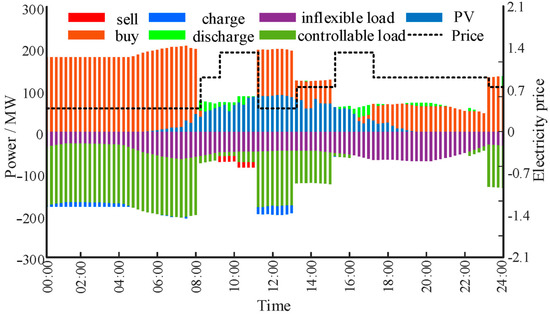

Figure 7 illustrates the power allocation of all resources within the park. Combined with the electricity price curve, it is observed that the park concentrates electricity consumption during low-price periods, including 00:00–08:00, 11:00–15:00, and 23:00–24:00, reduces consumption during high-price periods, and even sells electricity back to the grid during the PV peak generation hours from 09:00 to 11:00, thereby ensuring optimal economic operation of the entire park.

Figure 7.

Power curve of industrial park of proposed strategy.

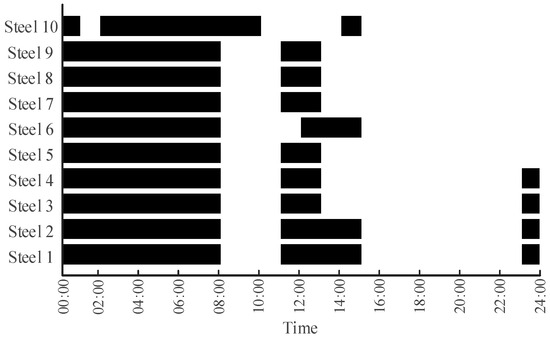

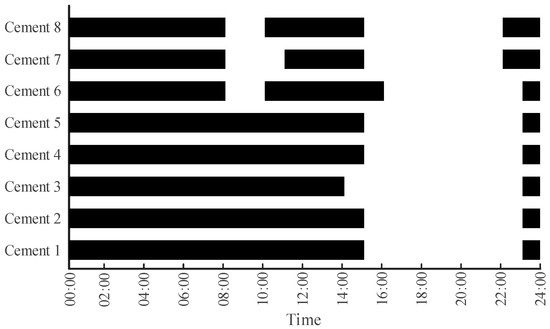

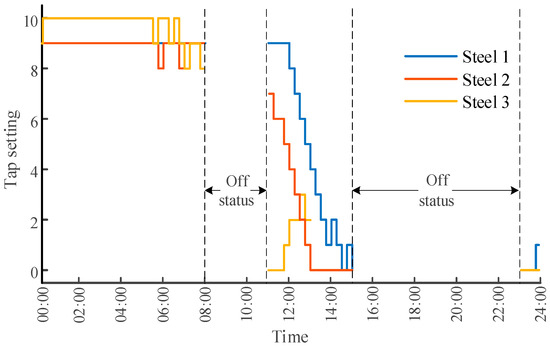

Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the day-ahead dispatch results of steel and cement production equipment, respectively. The results indicate that the scheduling of flexible devices achieves economic optimality based on the TOU electricity prices while ensuring normal production. The dispatch process also satisfies key operational constraints, including minimum continuous operating duration, maximum switching frequency, minimum required energy consumption, and process coupling relationships.

Figure 8.

Day-ahead dispatch results of steel production equipment.

Figure 9.

Day-ahead dispatch results of cement production equipment.

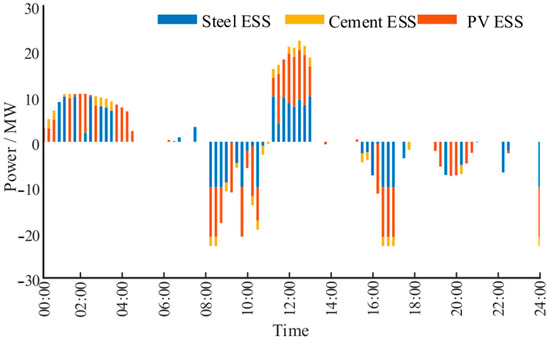

Building upon the day-ahead dispatch, the proposed strategy further optimizes the tap positions of electric arc furnace loads and the charge/discharge power of the energy storage system during the intraday dispatch phase. The corresponding dispatch results are shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11. It is observed that the storage system charges during low-price periods and discharges during high-price periods, indicating that intraday scheduling still primarily targets economic optimality. For time intervals with identical electricity prices, the allocation of storage power and tap position adjustments are influenced by the objective of smoothing power fluctuations. As evidenced by the results in Figure 5, the proposed strategy can significantly smooth the power fluctuations at the grid interface through the coordinated intraday control of energy storage systems and flexible industrial loads.

Figure 10.

Tap position adjustment of electric arc furnace equipment.

Figure 11.

Dispatch results of the energy storage system.

6. Conclusions

To enhance the flexibility and alleviate the supply–demand imbalance caused by the large-scale integration of renewable energy, this paper proposes a stochastic multi-time-scale energy management strategy for industrial parks, which accounts for the uncertainty of PV generation and leverages the regulation potential of flexible industrial loads. The proposed strategy incorporates PV uncertainty and dynamic electricity pricing. Compared with deterministic prediction-based approaches, the PV generation scenarios generated by CGAN better match the actual output trends, resulting in lower operating costs for the industrial park. By coordinating equipment on/off scheduling, electric arc furnace tap adjustments, and energy storage control across the day-ahead and intraday dispatch phases, the proposed approach effectively utilizes multiple regulation resources within the park and achieves better economic performance than strategies that only optimize equipment operation. Introducing a power fluctuation penalty term into the objective function, along with proper tuning of its coefficient, allows the method to further optimize intraday energy storage dispatch and tap position adjustments. This not only ensures economic optimality but also smooths power exchange fluctuations between the industrial park and the external grid. These results underscore the effectiveness of utilizing industrial loads in park-level systems to improve cost efficiency and renewable energy integration. This paper operates under the assumptions of perfect price curve knowledge, negligible communication delays, and ideal ESS efficiency. To enhance practicality, future work will incorporate multi-energy coupling systems and account for actual communication delays.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y. and Y.C.; methodology, X.L. and Y.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y. and B.L.; writing—review and editing, P.C. and Z.J.; supervision, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2025TSGCCZZB0081).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dong Yang, Pingping Chen and Zhihua Jiang were employed by the company Shandong Chongshi Electric Power Science and Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Ma, R.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Liu, R.; Zou, S. Renewable scenario generation based on the hybrid genetic algorithm with variable chromosome length. Energies 2023, 16, 3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, C. Optimal sizing of hybrid energy storage system considering power smoothing and transient frequency regulation. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 142, 108227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, H.; Sarwar, S.; Kirli, D.; Shek, J.K.H.; Kiprakis, A.E. A survey of second-life batteries based on techno-economic perspective and applications-based analysis. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Li, B.; Li, C. A coordinated control strategy of multi-type flexible resources and under-frequency load shedding for active power balance. Symmetry 2024, 16, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, T.; Liu, C.; Xu, Y.; Ding, M.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Dou, X. Optimal dispatching strategy for textile-based virtual power plants participating in GridLoad interactions driven by energy price. Energies 2024, 17, 5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Yan, J.; Tian, X.; Xue, X.; Zhao, Y. Progress in thermal energy storage technologies for achieving carbon neutrality. Carbon Neutrality 2023, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Xia, Y.; Wei, W. Self-Optimization Control for Alkaline water electrolyzers considering electrolyzer temperature variations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 2700–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Ning, L.; Liu, Y.; Liang, K.; Du, L.; Lu, J.; Yang, B. Dispatching method of high energy consuming load participating in peak shaving based on variational modal decomposition. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Gan, L.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Yu, K. Dispatching potential evaluation of purchased power load in iron and steel plant considering production process optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Chengdu, China, 18–21 July 2021; pp. 592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, L.; Yang, T.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Yu, K. Purchased power dispatching potential evaluation of steel plant with joint multienergy system and production process optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 1581–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golmohamadi, H.; Keypour, R.; Bak-Jensen, B.; Pillai, J.R.; Khooban, M.H. Robust self-scheduling of operational processes for industrial demand response aggregators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y. Research and system design of energy dynamic balance and optimal scheduling of iron and steel enterprises. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 983, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; He, T.; Shen, Y.; Qian, L.; Li, D.; Li, F. Bilevel optimal dispatch model for a peak regulation ancillary service in an industrial park of energy-intensive loads. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 230, 110272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaei, R.; Ting, D.S.-K.; Carriveau, R. Comparative analysis of energy dispatch strategies in PV-integrated renewable energy systems. Next Energy 2025, 7, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Zhou, B.; Ning, L.; Zheng, W.; Liu, H.; Hu, D.; Sun, J. Optimal dispatch of industrial loads considering process constraints for renewable energy consumption. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2025, 166, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, B.; Ma, H.; Li, Z. Optimal dispatch strategy for virtual power plants with adjustable capacity assessment of high-energy-consuming industrial loads participating in ancillary service markets. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Shaik, A.G.; Mahela, O.P. Swarm intelligent search and rescue method for economic emission load dispatch of renewable integrated power system considering uncertainty. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 95, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Y.; Yu, X.; Hou, Y. Quantitative analysis of power system flexibility based on k-means method and copula function. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Shanghai, China, 8–11 July 2022; pp. 1394–1398. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, L.; Lin, C. Matrix Wasserstein distance generative adversarial network with gradient penalty for fast low-carbon economic dispatch of novel power systems. Energy 2024, 298, 131357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, D.; Yan, P.; Liu, S.; Lin, Q.; Cui, P.; Li, Q. Optimization of in-motion EV charging infrastructure for power systems using generative adversarial network-based distributionally robust techniques. Energies 2025, 18, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.H.; Li, W.; Zomaya, A.Y. Enhancing Building-Integrated Photovoltaic Power Forecasting with a Hybrid Conditional Generative Adversarial Network Framework. Energies 2024, 17, 5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zheng, H.; Li, X. A Novel Hybrid Model for Multi-Step Ahead Photovoltaic Power Prediction Based on Conditional Time Series Generative Adversarial Networks. Renew. Energy 2022, 199, 560–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dong, B.; Qiu, Y. Conditional Generative Adversarial Network for Generating Building Load Profiles with Photovoltaics and Electric Vehicles. Energy Build. 2025, 335, 115584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xuan, L.; Gong, D.; Xie, X.; Zhou, D. A long short-term memory–Wasserstein generative adversarial network-based data imputation method for photovoltaic power output prediction. Energies 2025, 18, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zu, G.; Ji, W.; Huang, P.; Ding, Q. Data-driven distributionally robust day-ahead dispatch for active distribution networks based on improved conditional generative adversarial network. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, J.; Hou, J.; Zhao, X. Joint grid-storage planning considering the operational flexibility of carbon capture power plants. High Volt. Technol. 2024, 50, 5164–5173. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Zhang, X. Chance-constrained optimal configuration of BESS considering uncertain power fluctuation and frequency deviation under contingency. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 2291–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Cheng, C. A mid-term scheduling method for cascade hydropower stations to safeguard against continuous extreme new energy fluctuations. Energies 2025, 18, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).