1. Introduction

The clean energy transition supports a global shift from fossil fuel-based energy systems to renewable and sustainable sources such as solar, wind and biomass. This transformation is driven by the urgent need to mitigate climate change, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, enhance energy security and build a more resilient, sustainable energy infra-structure that supports long-term economic growth [

1].

In fact, the switch from energy systems based predominantly on the use of fossil fuels to new, more efficient and environmentally sustainable models based on the use of renewable energy sources is mandatory to mitigate climate change and increase energy security.

Promoting a clean energy transition represents a priority for the European Union (EU), which is strongly engaged in the fight against climate change, with the ambitious goal set out in the European Green Deal to become climate-neutral by 2050, setting an intermediate 55% target for CO

2 emissions by 2030 [

2]. Considering the enormous efforts required from all European countries to move to a climate-neutral economy by 2050, a complex set of laws has been defined to accelerate the energy transition. In particular, the Clean Energy for all Europeans Package [

3] sets out the European energy policy framework to facilitate a clean energy transition towards a more sustainable, decentralized and consumer-oriented system. The Clean Energy Package (CEP), based on four Directives [

4,

5,

6,

7] and four Regulations [

8,

9,

10,

11], focuses on the energy performance of buildings, renewable energy, energy efficiency, governance and electricity market design, updating the EU targets for 2030 as follows:

A 40% reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions compared to 1990 levels;

A share of 32% for renewable energy sources in the EU energy mix;

An energy efficiency target of 32.5%, compared to a baseline scenario set in 2007.

Another important initiative is the REPowerEU plan, launched in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which aims to reduce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas (−18% of gas consumption) by promoting energy efficiency, diversifying energy supplies and producing clean energy by accelerating the adoption of renewable sources [

12,

13,

14]. By 1 March 2026, EU Member States must submit national plans containing strategies for diversifying energy supplies, with detailed measures and milestones for phasing out direct and indirect imports of Russian gas and oil. These measures will accelerate the EU’s energy transition and diversify energy supplies to eliminate risks to security of supply and market stability [

15]. The RePower plan also supports citizen-driven energy actions to contribute to the clean energy transition, advancing energy efficiency within local communities [

16].

As far as Italy is concerned, European regulatory frameworks have been transposed into national legislation, in line with the country’s ambitious decarbonization targets and providing financial incentives for community-based energy projects.

The Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan 2030 (PNIEC) [

17] defines Italy’s policies and measures for achieving its energy and climate targets for 2030 and is the main instrument for implementing a new energy policy that guarantees the full environmental, social and economic sustainability of the Italian national territory and supports the energy transition. It addresses decarbonization, energy efficiency and energy security in an integrated way through the development of the internal energy market, research, innovation and competitiveness [

17]. The updated version of the 2023 PNIEC sets the goals of a 43.7% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, compared to 2005, and of increasing electricity production from renewable sources to exceed 65% [

18].

Although, unlike other European countries, Italy does not yet have a “framework law on climate”, numerous provisions deriving from decrees and sectoral laws also contribute to implementing the EU guidelines. For example, budget laws and several ministerial decrees have introduced incentives to promote renewable energy sources, including the “Conto Termico” [

19], tax benefits aimed at promoting the replacement of obsolete air conditioning systems [

20], the 110% “Super bonus” [

21] and other financial incentives to increase energy efficiency and reduce the energy demand of buildings [

22]. Furthermore, Decree No. 414 of 7 December 2023 of the Minister of the Environment and Energy Security (REC Decree), in force since 24 January 2024, introduces a new participatory model of energy management represented by Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) [

23]. In particular, the REC Decree defined the new methods of granting incentives, aimed at promoting the local share of energy by installing plants powered by renewable sources included in configurations of energy communities, groups of self-consumers and remote self-consumers.

However, as Lv [

24] also points out, the energy transition is not a straightforward process, as there are several factors that could hinder and slow down its progress. In fact, the high cost of investing in infrastructure for renewable energy sources, the political influence of the fossil fuel industry in some countries and local communities’ concerns about noise pollution and the impact on the landscape are all factors that need to be considered in the governance of this process. In this context, the local dimension is becoming increasingly important due to its significant contribution to greenhouse gas emissions (cities are responsible for almost 70%), high energy consumption and the even greater impact of climate change on the population and infrastructure [

25]. Municipalities are therefore taking on a central role in the implementation of energy and climate policies, facing challenges such as high energy costs, public funding and investment payback times, the reliability of energy services provided, public acceptance and technical and managerial skills.

Taking advantage of the composite legislative framework aimed at promoting a clean energy transition at the local level within the achievement of the 2030 targets, several projects have been presented to implement energy production from renewable sources. Ronchetti et al. analyzed project proposals in the authorization phase for electricity production from renewable sources to assess the achievement of the intermediate decarbonization targets set for 2030. They highlighted an imbalance in the location of projects in Southern Italy, which could lead to future problems if not properly aligned with the infrastructure development planned by the national government [

26].

From a methodological point of view, taking into account that energy and climate issues are intertwined and should be integrated into a common planning framework that support the energy transition, as also underlined by the sustainable energy and climate action plans (SECAPs) [

27], it is necessary to adopt scalable and comparable analytical approaches based on widely used models capable of representing technological progress and performing energy–environmental scenario analyses to devise the energy technology roadmaps. Among the most used models that support policy assessment and energy planning at the local level [

28], The Integrated MARKAL-EFOM System (TIMES) model generator, developed as part of the International Energy Agency’s Energy Technology Systems Analysis Programme (ETSAP-IEA), ensures compliance with all requirements as it allows us to perform energy and environmental analyses and devise robust policies [

29]. A study by Gupta and Ahlgren [

30] demonstrated that the TIMES platform is the most widely used for energy systems optimization over a long time horizon to support energy planning at the local scale. The TIMES-NE model was set up to analyze the energy system of the city of Gothenburg considering the end-use demands of the residential and transport sectors. In the study, the City Energy Plan scenario was defined as an exploratory strategic scenario by incorporating the policy measures outlined in the city energy plan with the aim of describing the possible consequences of strategic decisions [

31]. The TIMES-Oslo model is another example of the TIMES application at the local scale to assess how the implementation of energy and climate policies can contribute to low-carbon cities [

32]. The TIMES_EVORA model was implemented to analyze the energy system of the Portuguese city in 2030 by introducing constraints for the reduction of CO

2 emissions and considering the household incomes to verify their investment capacity for the acquisition of more efficient technologies, from household appliances to private vehicles [

33]. Di Leo et al. implemented the TIMES-Basilicata model to analyze the energy system of the Basilicata region in Southern Italy. They focused their study on the construction of two low-carbon scenarios to identify development trajectories for the energy system in the Basilicata region: imposing an 85% reduction in CO

2 emissions by 2050 and introducing several combinations of energy efficiency measures. The modeling platform has proven to be effective and useful in supporting energy and climate strategic planning in the medium-to-long term on a regional/local scale [

34]. Another local application of the ETSAP-TIMES model generator involved the implementation of the TIMES Land-WEF model to investigate the interactions and interrelations between water, energy, food and land in the agricultural system of the Basilicata region. In this application, the scenario analysis carried out to support the achievement of some of the objectives set out in the European Farm to Fork Strategy, such as a reduction in pesticides or fertilizers from 2030 onwards, showed the evolution of the system under consideration in terms of land use, energy consumption and water use [

35]. Di Leo et al. used the ETSAP-TIMES model generator to analyze the automotive manufacturing industry and identify the most efficient and sustainable solutions for the production system. In this study, scenario analysis was applied to evaluate the system’s responses to the introduction of energy and material recovery measures and the introduction of alternative energy production technologies [

36].

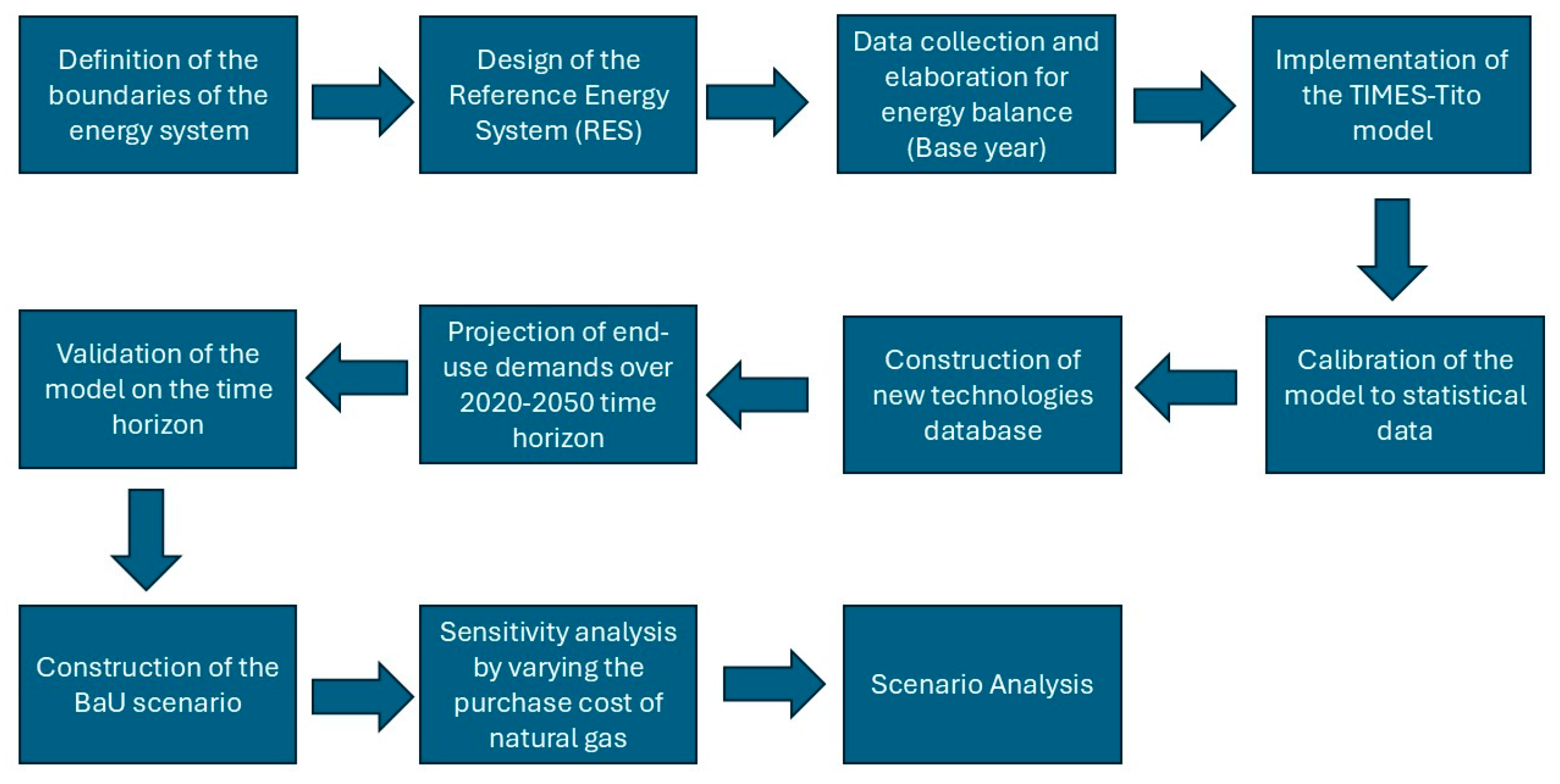

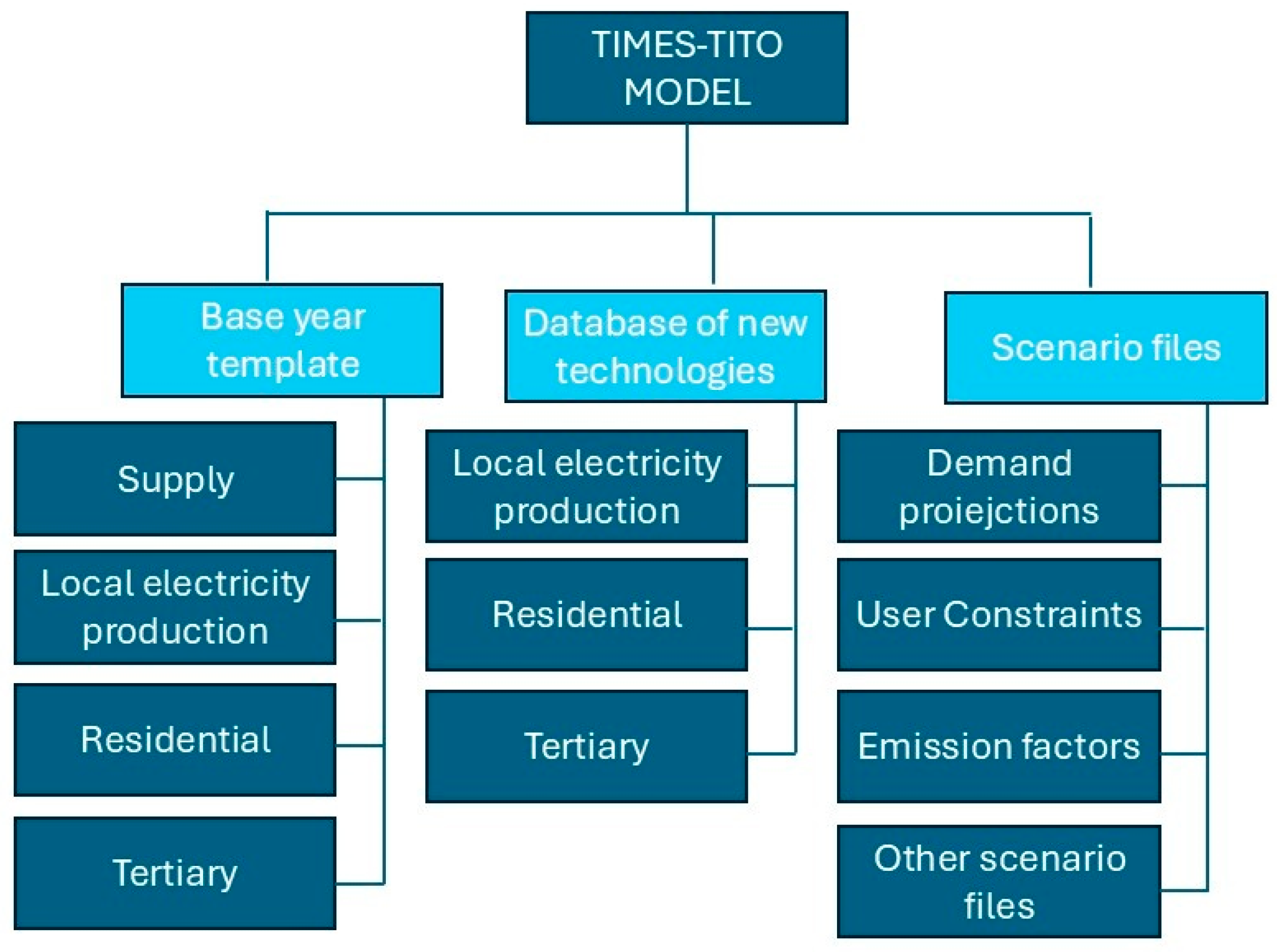

In this study, the ETSAP-TIMES model generator is applied to model the energy system of the municipality of Tito, in Southern Italy, to analyze its evolution over a 30-year time horizon (2020–2050) under a Business-as-Usual (BaU) scenario. The structure of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 outlines the methodology and its application to local energy systems modeling;

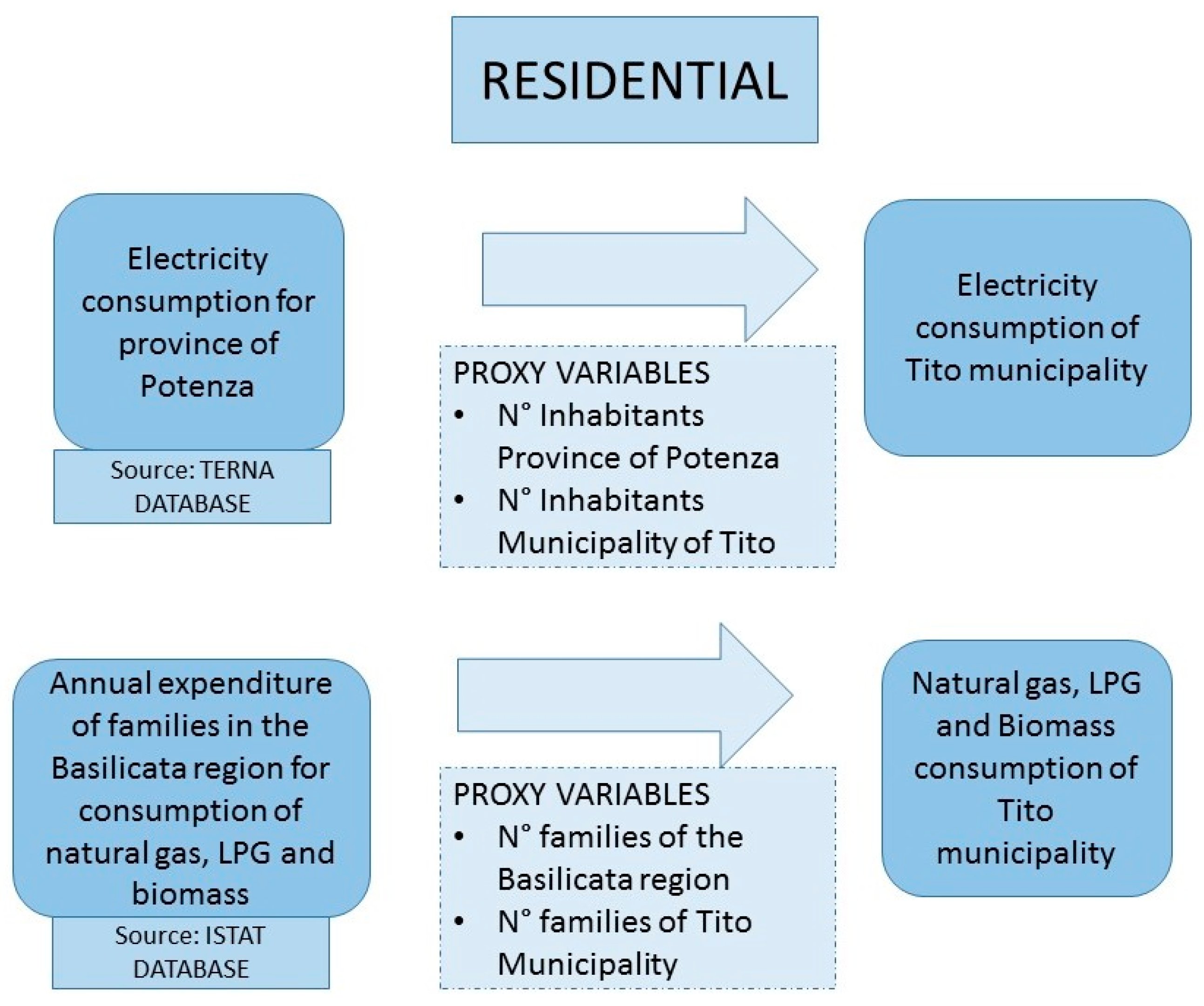

Section 3 provides an in-depth description of the energy system in the municipality of Tito, with reference to the statistical data for characterizing the demand profiles, the technologies in use and those available in the modeling time horizon and the projections of future energy requirements;

Section 4 and

Section 5 present the results of the optimization of a BaU scenario and its possible implications in terms of energy policies.

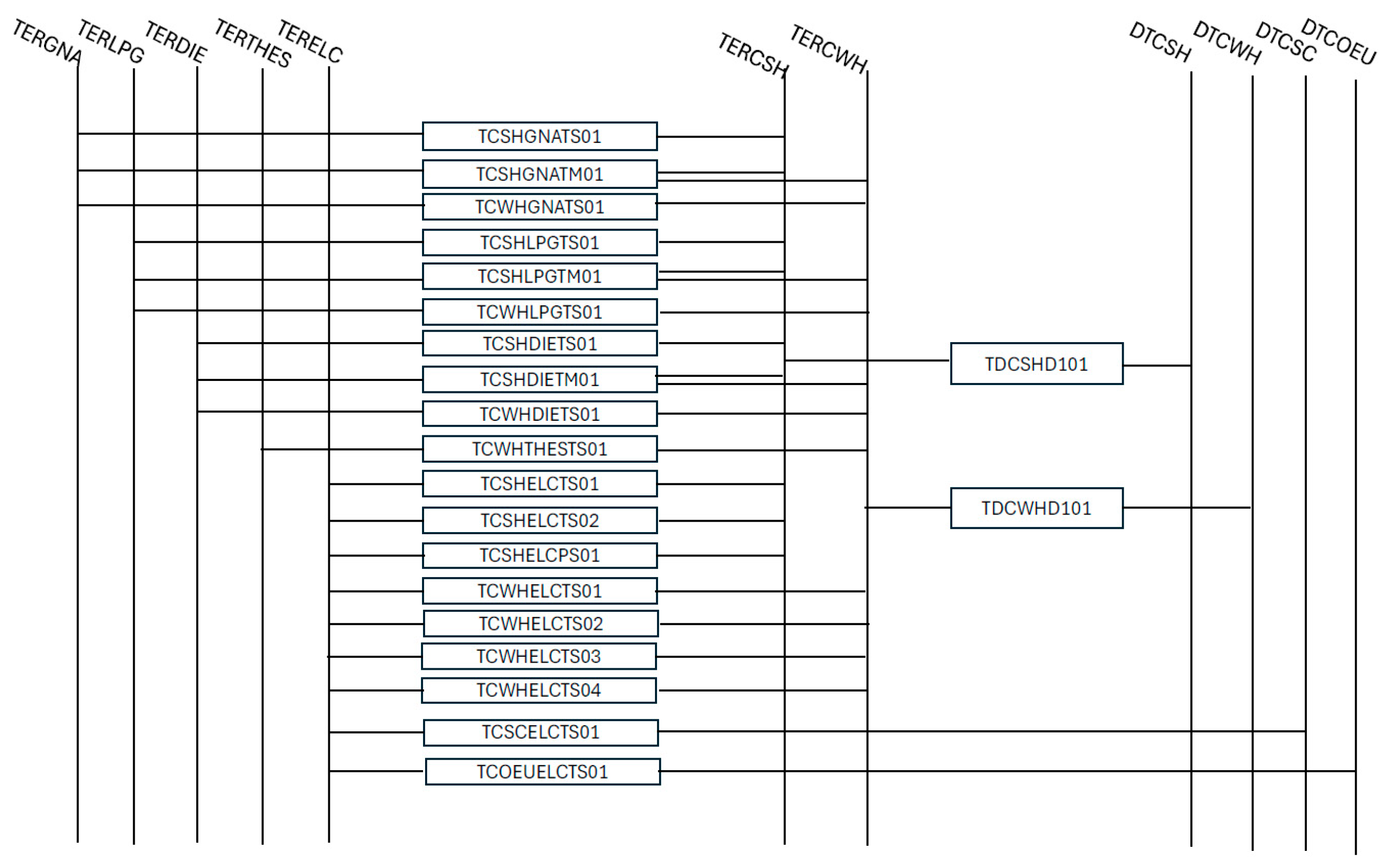

4. Business-as-Usual Scenario

The Business-as-Usual scenario represents the “status quo” development of the energy system of the municipality of Tito, taking into account the statistical data and the demand projections for the reference energy system (benchmark scenario). The exogenous assumptions concerned the costs of energy commodities, which were set to be constant over the time horizon, and the revenues from environmental compensation paid on gas consumption, subject to the exploitation of oil fields, which were considered unchanged until 2050. The electricity produced by ground-mounted photovoltaic systems and those serving industrial buildings is not considered in this scenario. In fact, in the first case, the electricity produced is fed into the national electricity grid, while in the second case, the electricity produced and self-consumed is related to a non-modeled sector. For the tertiary and residential sectors, the electricity produced and fed into the grid is considered an export. As concerns the technologies included in the file “database of new technologies”, photovoltaic systems for both the residential and tertiary sectors were duplicated to allow their activation in the examined time horizon and to make their contribution explicit. In the tertiary sector, a minimum increase of 10% in the use of technologies with combined outputs (e.g., space heating and hot water) was assumed with respect to the base year.

Furthermore, category-specific drivers were identified to estimate demand trends over the time horizon (2020–2050) through a statistical approach. For the residential sector, population and household projections at municipal level were used. The 20-year demographic trend provided by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) was used, which estimates a population decline from 7147 in 2022 to 6389 in 2042 [

63]. This assumption was also used to project the demographic trend to 2050 by identifying an appropriate mathematical function for extrapolation. The negative population trend shown in

Table 10 is typical of small municipalities in Southern Italy and in the internal areas of the Italian Apennines. On the contrary, the number of families residing in Tito in the last twenty years has recorded an increase from 2003 to 2023 (from 2323 to 2873), with a decrease in the average number of members per family (from 2.81 in 2003 to 2.45 in 2023) [

52]. Based on the statistical data of the period 2003–2023, the trend of the average number of members per family in the period 2024–2050 was estimated and, consequently, so was the trend of the number of families in the period 2020–2050 (obtained as the ratio between the population and the average number of members per family).

For space heating, the number of heated square meters per household was assumed to be constant over the entire 2020–2050 time horizon and, using the estimated number of households as the main driver, the number of heated square meters from 2024 to 2050 was calculated.

Water heating demand, on the contrary, is directly linked to population trends, assuming an increase in daily demand for hot water per capita from the current 40 L to 50 L from 2030 to 2050.

Like space heating, the number of households is the main driver of space cooling, lighting and other electricity consumption demand over the time horizon. For space cooling, the share of households using air conditioning is assumed to increase from 50% in the base year to 60% in 2030–2040 and to 70% by 2040. Demand projections for lighting and other electrical uses were estimated, assuming an average household demand of 150 lumens for lighting and 290 MJ for other electrical obliged uses.

Table 11 summarizes the end-use demand projections for the period 2020–2050 in the residential sector.

In the tertiary sector, the trend of energy demand for different end-uses is not directly related to demographic parameters. Based on the available statistical data, a trend line was identified for each subsector and, using this information, the demand projection over the 2020–2050 time horizon was obtained. For the public sector (Schools and Public Buildings), energy demand was considered constant over the time horizon, assuming that there is no increase in the volumes of Public Buildings and that the decrease in population does not affect consumption.

Table 12 summarizes the energy demand projections of the different tertiary sectors.

5. Results

The subsequent sections present the results of the BaU scenario, focusing on electricity production, energy supply, total energy consumption and air pollutant emissions.

5.1. Electricity Production and Energy Supply

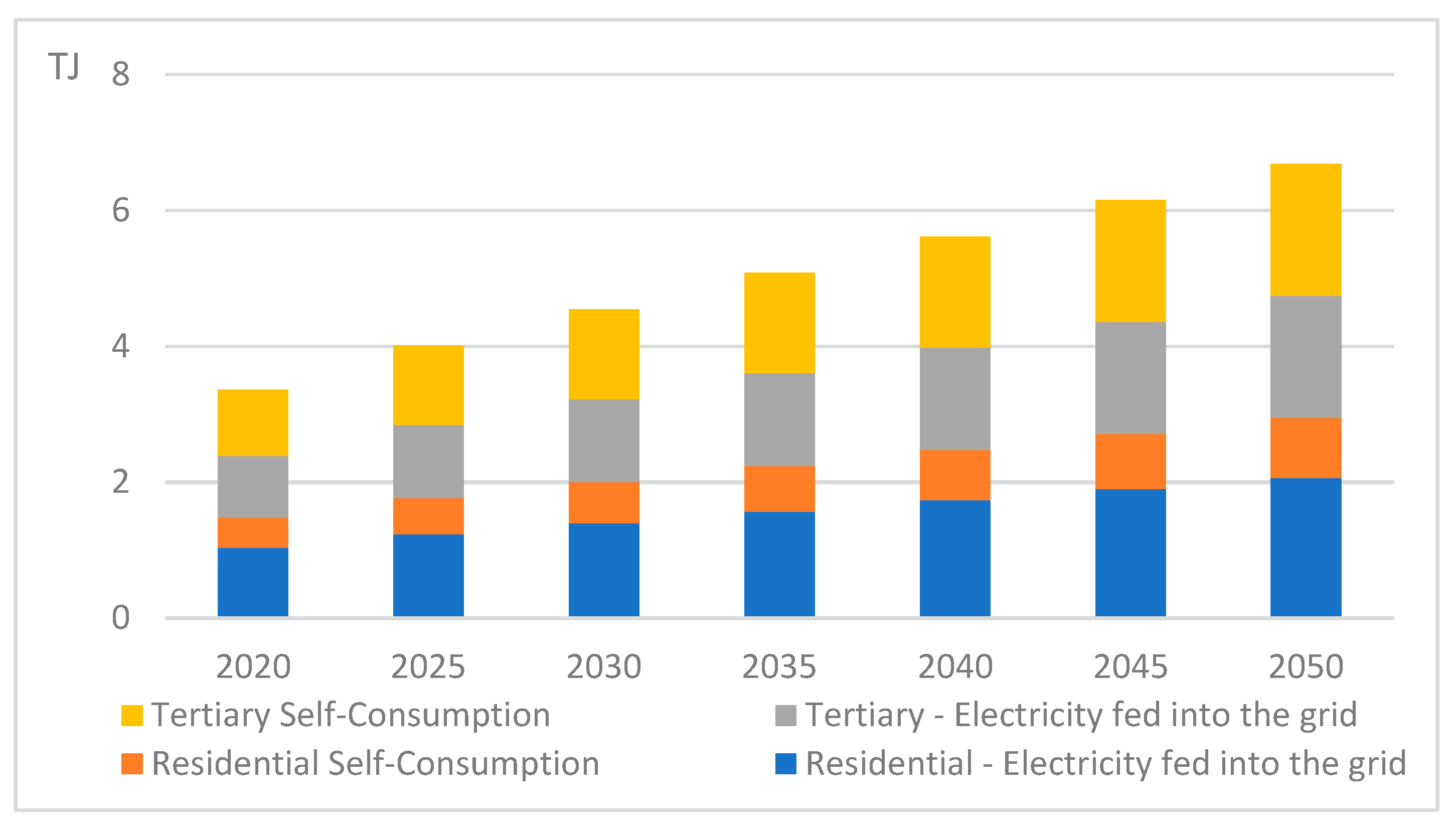

Electricity production from PV (

Figure 4) increases by 99% in the considered time horizon, going from 3.4 TJ in 2020 to 6.7 TJ by 2050, highlighting a strong commitment to the development of solar power, which is essential to meet energy needs and, at the same time, support the achievement of sustainability goals.

A total of 56% of photovoltaic electricity is produced by the tertiary sector and 44% by the residential sector, demonstrating the equal importance of both sectors in the development of photovoltaic energy.

Investing in photovoltaics is a measure that, on the one hand, provides electricity from renewable sources and, on the other, reduces CO

2 emissions, objectives contained in the PNIEC [

14]. In the year 2020, 42% of the electricity produced by photovoltaic is self-consumed (1.4 TJ), while the remaining 58% (1.9 TJ) is sent to the national distribution grid.

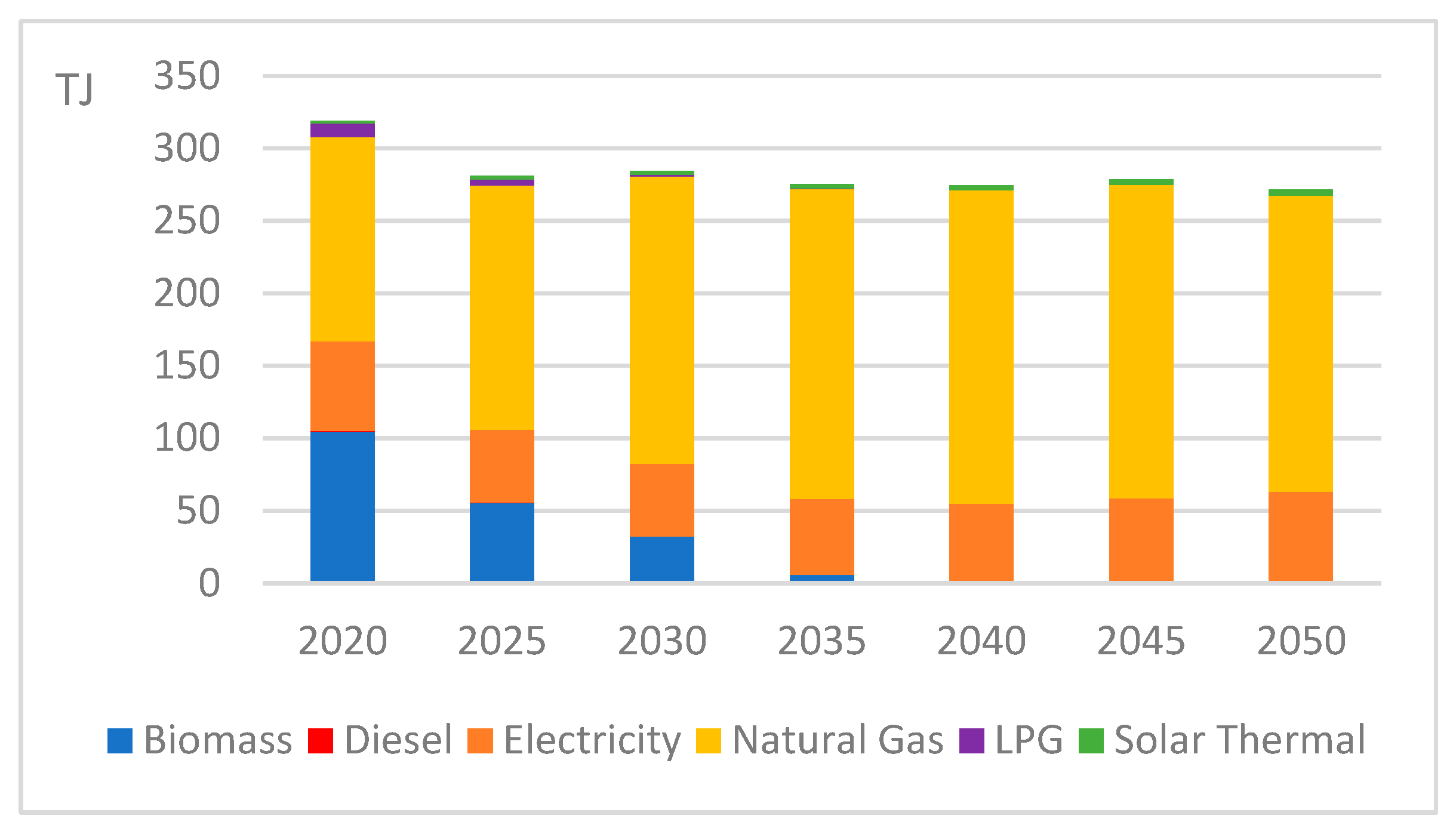

Figure 5 shows the energy mix from 2020 to 2050, highlighting the important role of natural gas and electricity, which, in the long term, substitute all fuels. In particular, natural gas reaches its maximum in 2035 (214 TJ), while biomass, diesel and LPG are gradually phased out by 2040, replaced by electricity, which increases to 6.4 TJ in 2050, representing 24% of the energy supply.

5.2. Energy Consumption

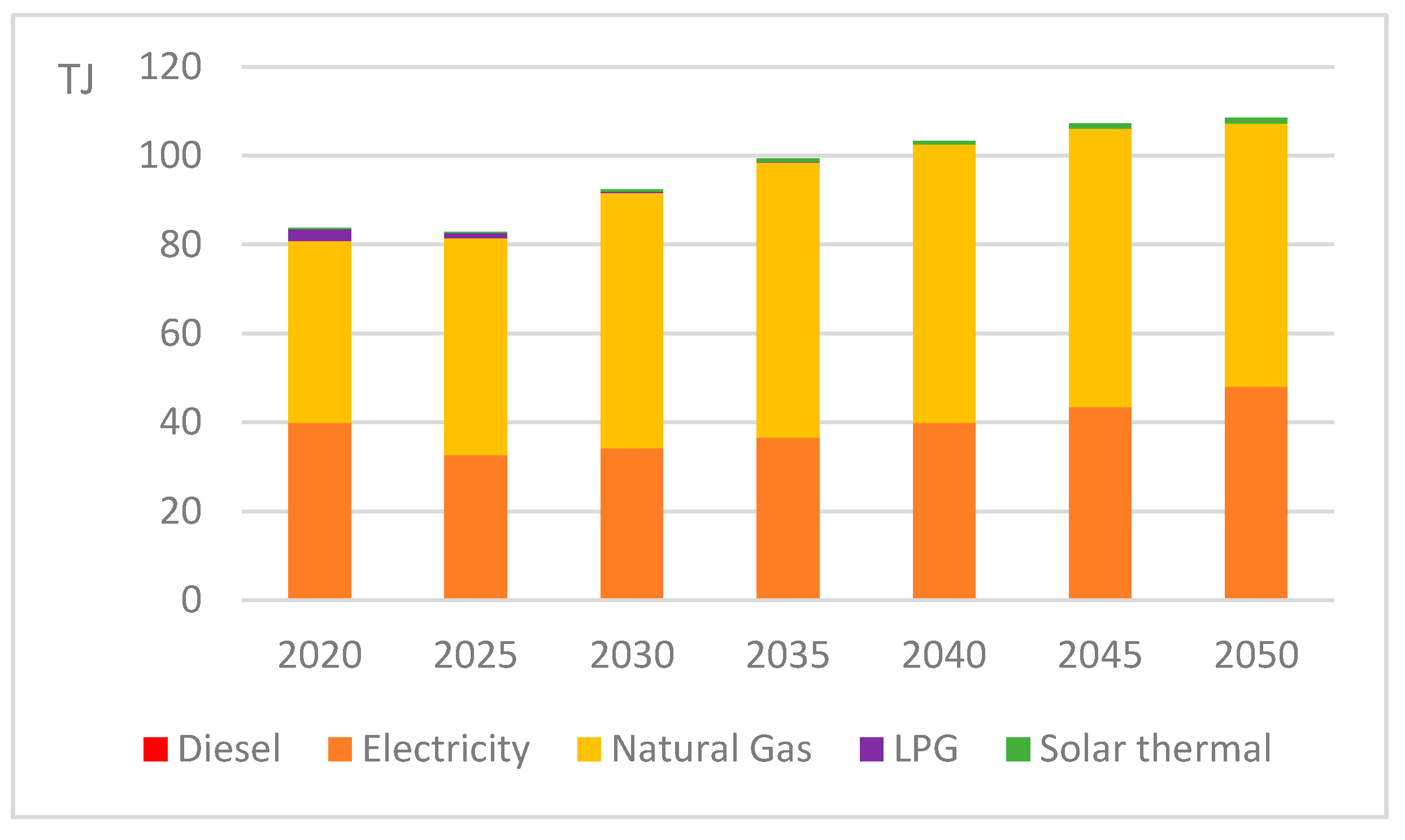

Total energy consumption from 2020 to 2050 (

Figure 6) decreases by 15% and shows a significant change in energy use patterns, driven by the decline in biomass and the increase in natural gas consumption (+44% in 2050 compared to 2020). Biomass is used only in the residential sector and, together with LPG, is gradually phased out by 2040.

Diesel follows a similar trend, being phased out by 2035. Electricity consumption, after an initial decrease from 63 TJ in 2020 to 52 TJ in 2025, increases 5% over the time horizon reaching 66 TJ in 2050.

Solar thermal energy shows a significant growth (+187% by 2050), even though it still represents a minimal part of the energy consumption, driven by investment in renewable energy to meet climate goals [

64]. Electricity consumption overall is about 20% in 2020 and 24% in 2050 with a minimum of 52 TJ (18%) in 2030; it is mainly used in the tertiary sector (62% in 2020 and 73% in 2050 of the total electricity available). Natural gas consumption remains constant over the period considered in both the residential (71%) and tertiary (29%) sectors. The distribution of LPG consumption, which also remains constant until 2040, accounts for 73% in the residential sector and 27% in the tertiary sector, before being phased out by 2040.

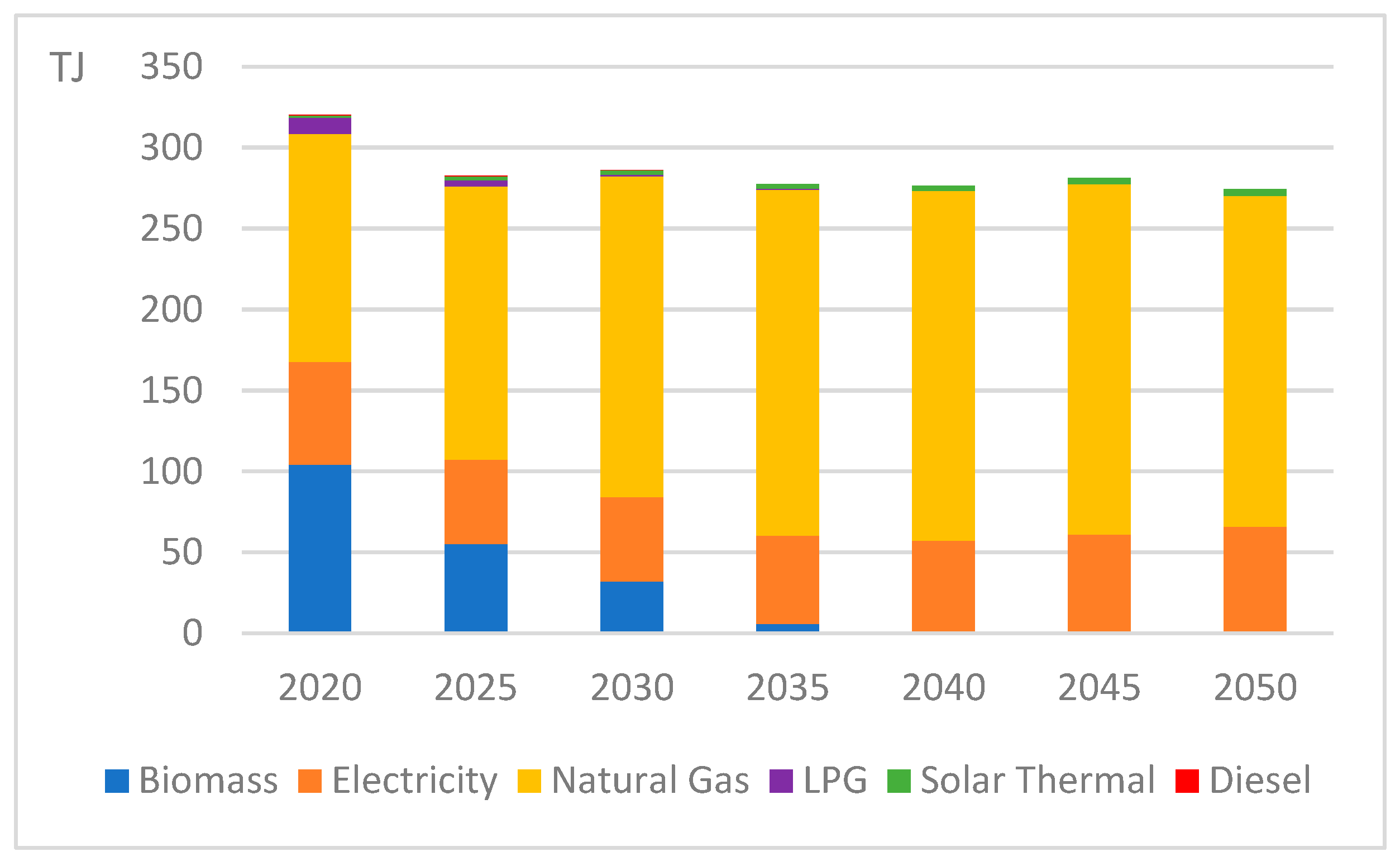

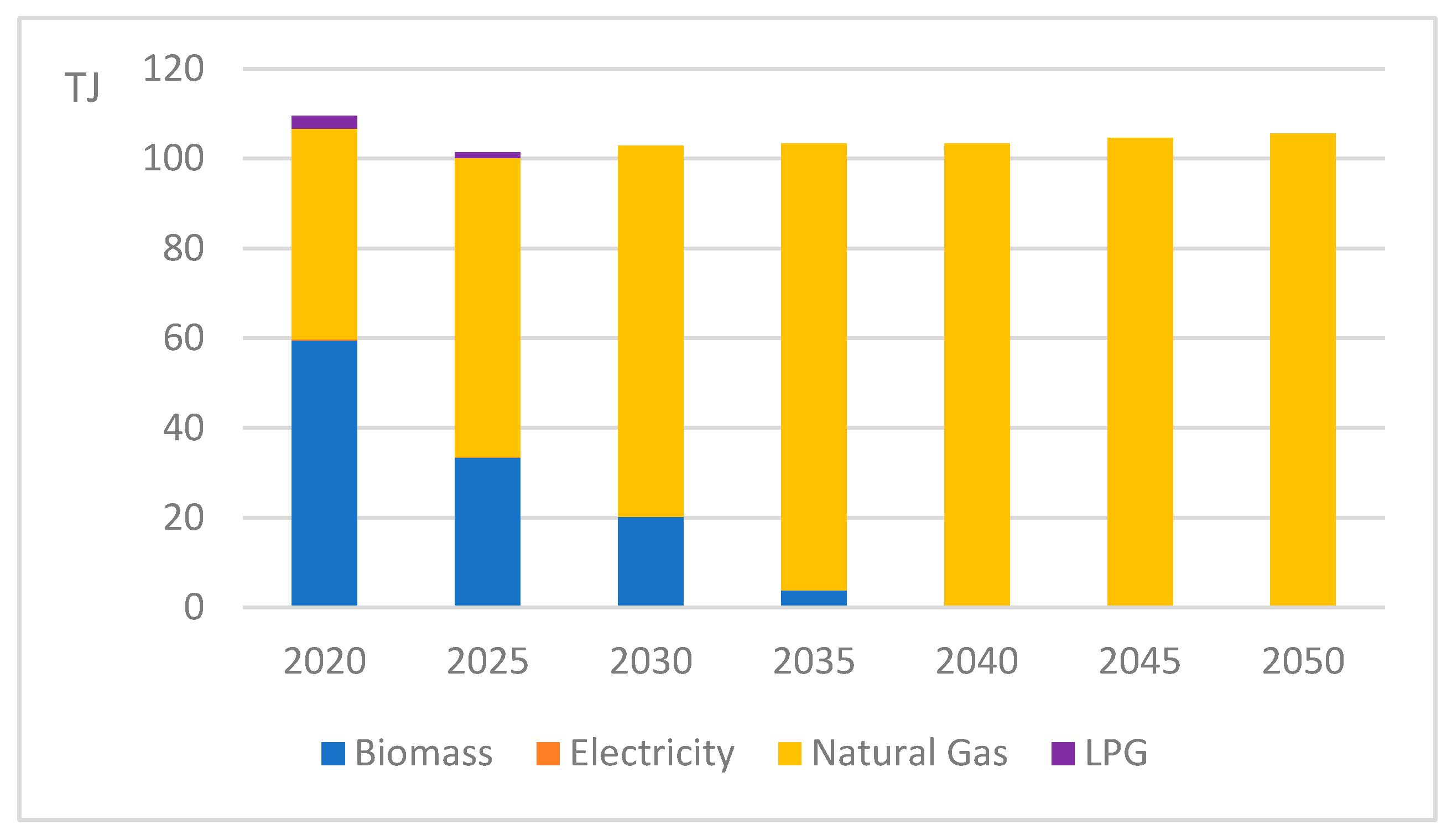

Energy consumption in the residential sector decreases 30% by 2050 due to the replacement of base year technologies with more efficient ones. Biomass, the prevailing fuel in 2020 (44%), is phased out by 2040, having been entirely substituted by natural gas (88%). Electricity consumption decreases by 6 TJ in 2050 compared to the base year, while its percentage contribution to total residential consumption is almost constant (around 10% on the whole time horizon). Solar thermal increases from 1.2 TJ in 2020 to 3 TJ by 2050) contributing around 2% of the energy demand of the residential sector in 2050 (

Figure 7).

The demand for space heating, initially met by natural gas, biomass and LPG (52%, 45% and 3%, respectively), is entirely covered by natural gas from 2040 onwards, decreasing by about 4% on the time horizon (

Figure 8). Over the 2020–2050 time horizon, energy demand remains stable, despite a 6% increase in heated surface area. This is due to improved energy efficiency, with a reduction in specific energy consumption (energy per unit area).

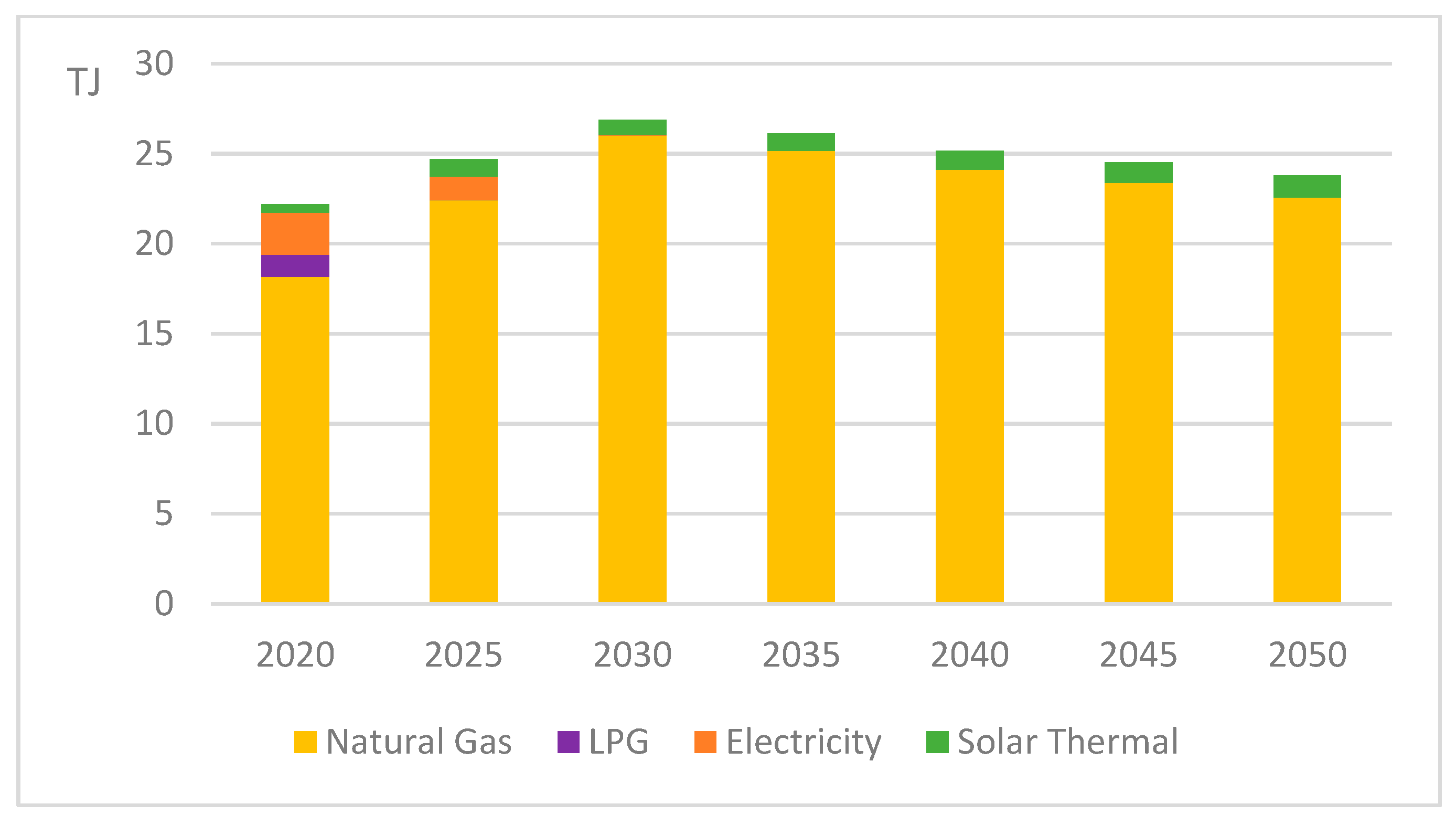

Water heating demand increases by 7% over the time horizon; in 2020, it is fulfilled by natural gas (82%), electricity (11%), LPG (5%) and solar thermal (2%), while in 2050, natural gas and solar thermal are the only fuels (95% and 5%, respectively) (

Figure 9). In the 2020–2030 decade, an increasing volume of water is heated without significantly increasing energy consumption. After 2030, the amount of heated water decreases, while energy demand remains virtually unchanged; this implies a slight increase in specific energy requirements.

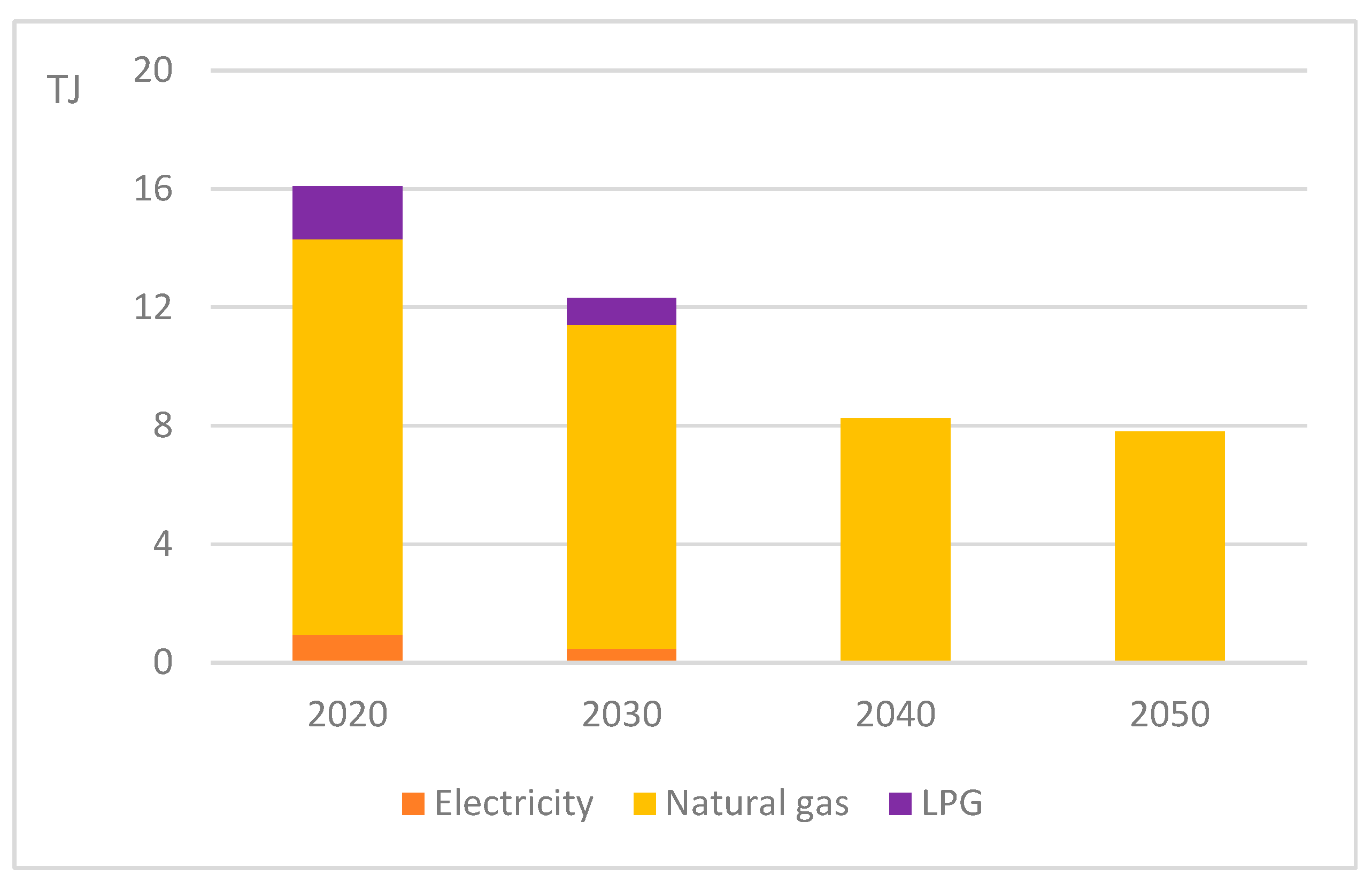

Cooking demand, initially fulfilled by natural gas (83%), LPG (11%) and electricity (6%), is fully met by natural gas by 2040, with a decrease of 51% in total fuel consumption (

Figure 10). This is due to the replacement of the technologies used in the base year with new, more efficient natural gas technologies.

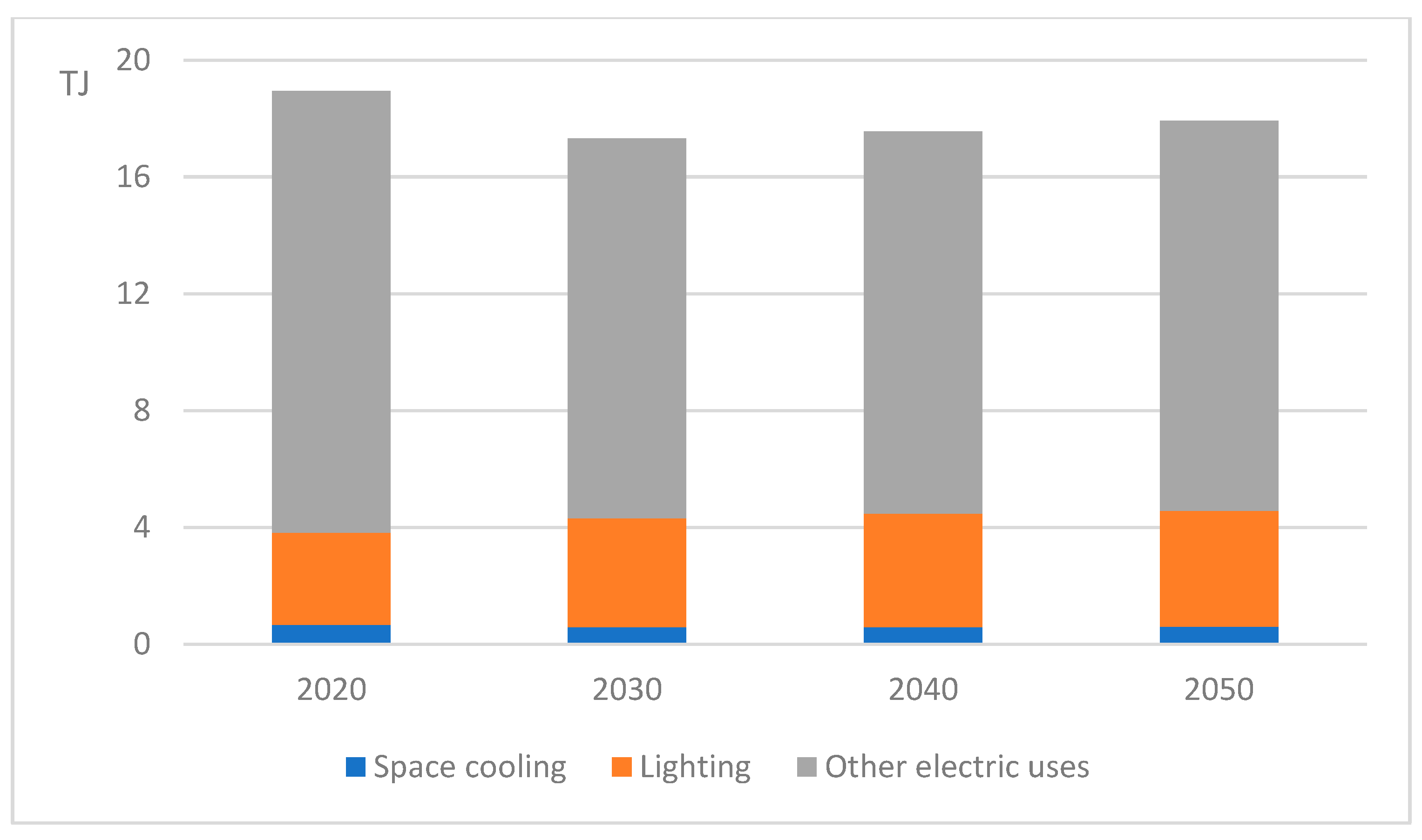

Space cooling is entirely fulfilled by electricity, accounting for 3% of electric uses including lighting and other electric appliances, with a 25% increase for lighting in 2050 compared to the base year (

Figure 11). In the case of space cooling, the cooled surface grows by 5.7% from 2020 to 2050, while the share of electricity used for cooling remains very low and almost constant over time. This indicates that the efficiency of air conditioning systems has improved significantly. In the case of lighting, the end-use demand increases slightly from 0.063 to 0.067 GLumen, but the energy used remains almost unchanged, especially due to the introduction of LED technologies.

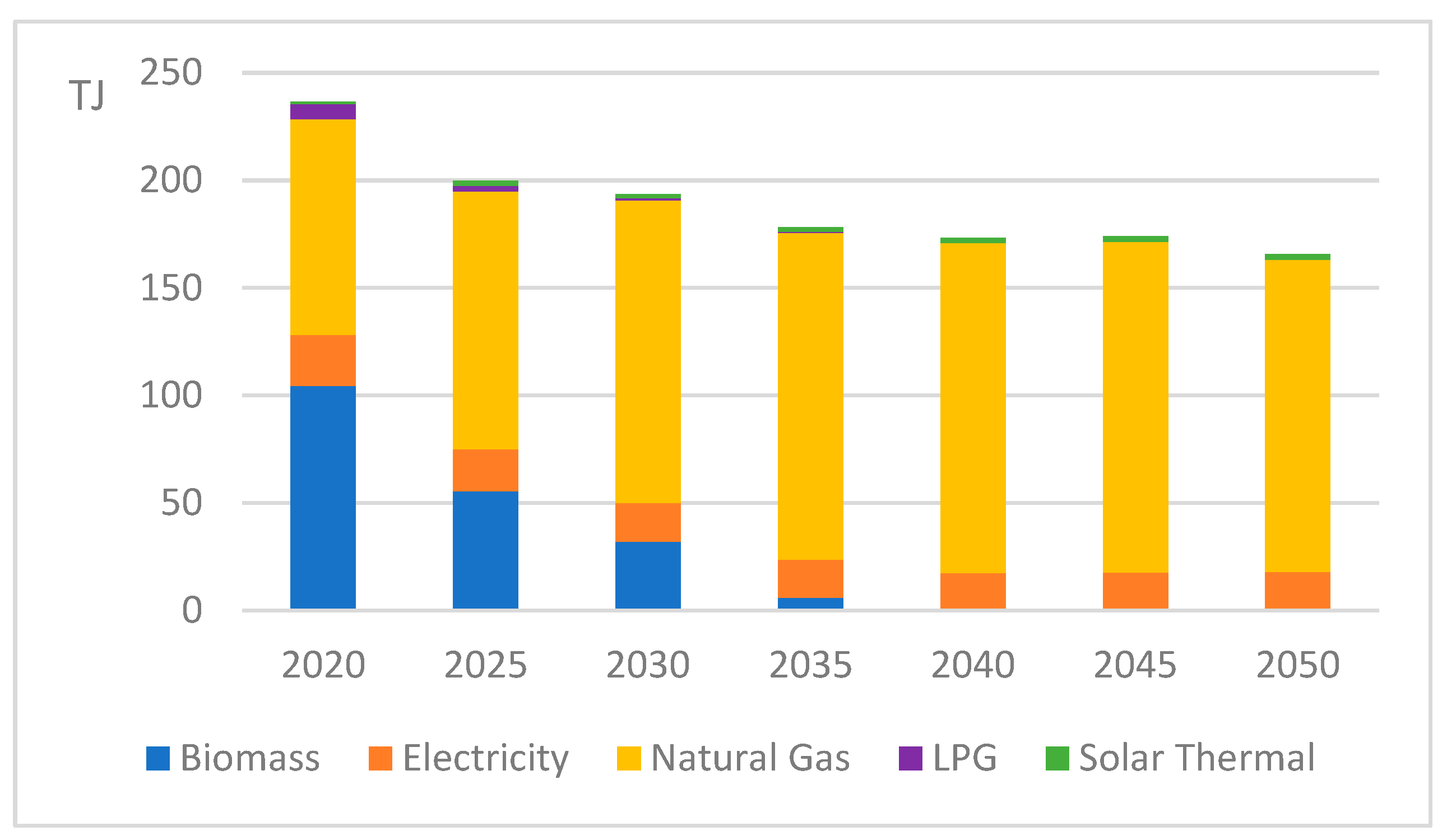

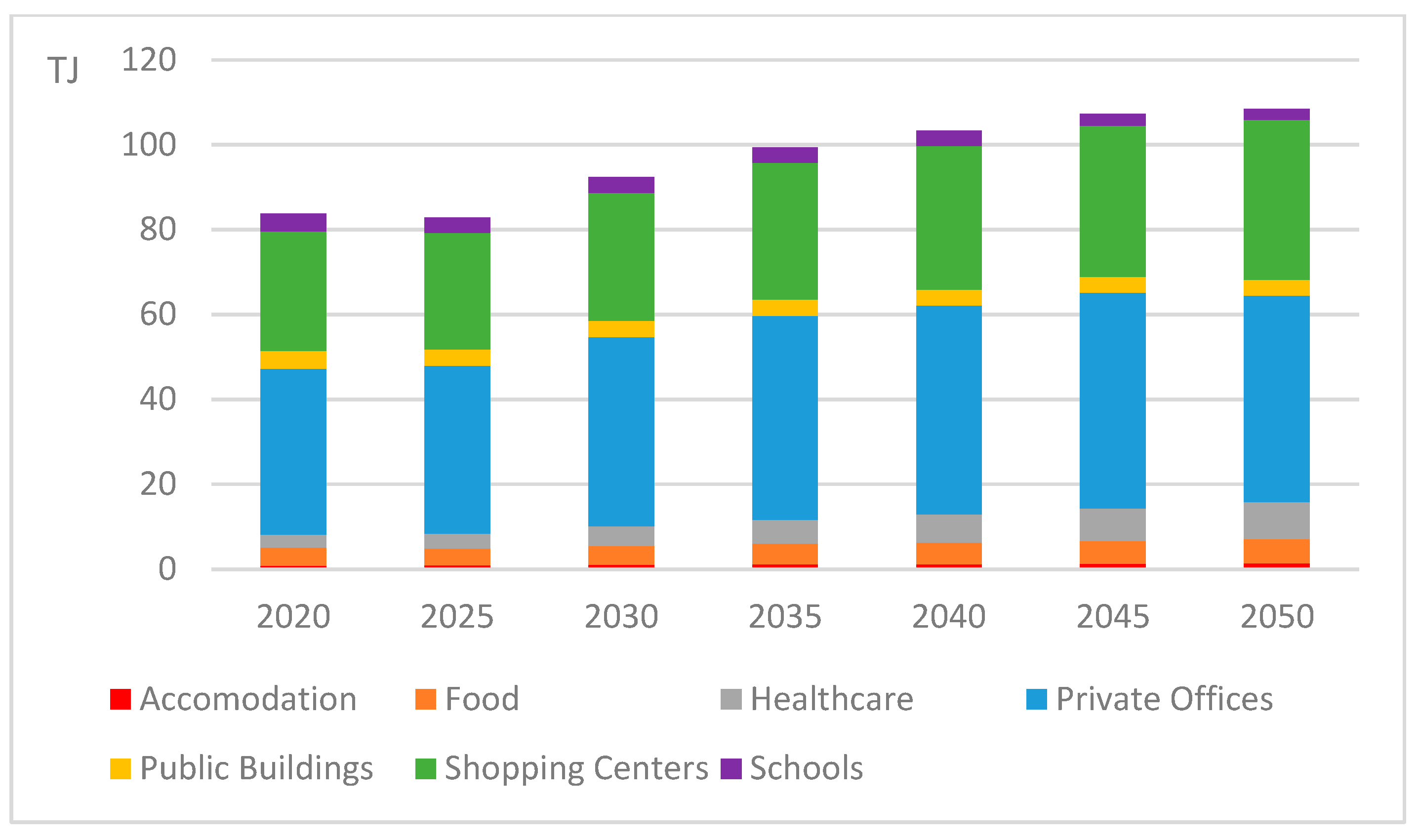

Energy consumption in the tertiary sector increases by 30% over the period considered, i.e., +22% for electricity, +45% for natural gas and a significant increase in solar thermal energy (from 0.2 to 1.3 TJ), which replaces LPG and diesel, gradually phased out from 2030 onwards. In 2050, tertiary energy demand is fulfilled by natural gas (55%), electricity 44% and solar thermal (1%) (

Figure 12).

Total energy consumption by subsector provides further insights, as shown in

Figure 13. Energy consumption in the tertiary sector increases by 30% over the time horizon. In 2020, Private Offices and Shopping Centers accounted for 47% and 34%, respectively, followed by Food, Public Buildings and Schools (around 5% each). In 2050, a remarkable increase in the Healthcare and Accommodation subsectors is expected (+190% and +78%, respectively), while Schools and Public Buildings will consistently reduce their consumption (−37% and −12%, respectively) due to efficiency interventions in building structures. Food shows a 30% increase over the time horizon, in line with the expected growth in the number of employees, accounting for about 5% on entire time horizon.

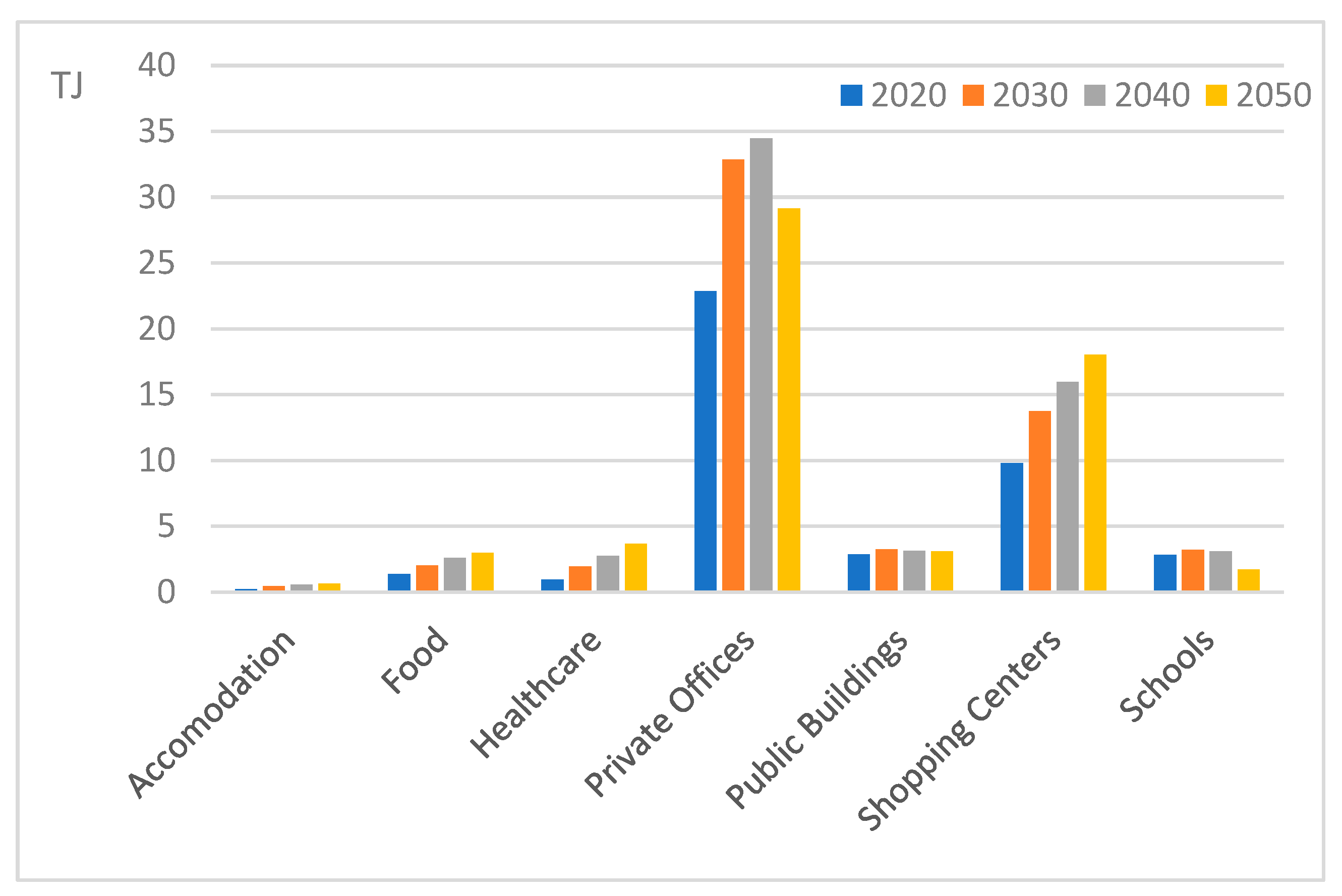

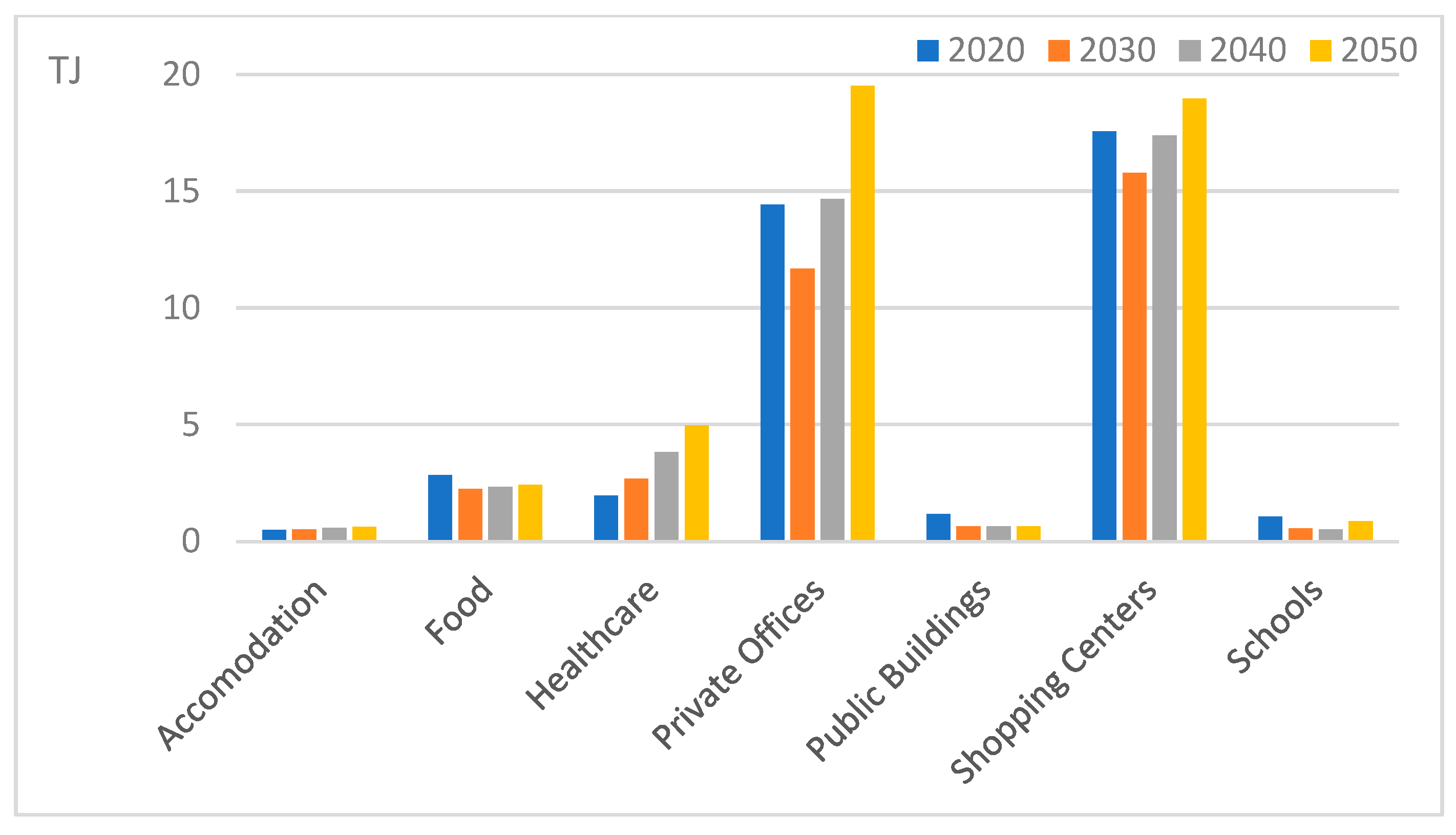

Figure 14 and

Figure 15 show natural gas and electricity consumption by subsector over the time horizon. For both fuels, Private Offices and Shopping Centers have the highest consumption. In 2020, Private Offices account for 56% of natural gas consumption and 37% of electricity consumption, while Shopping Centers account for 24% of natural gas and 44% of electricity consumption, respectively. In 2050, Private Offices see a 7% decrease in their share of total natural gas consumption (from 56% in 2020 to 49% in 2050), while their share of total electricity consumption increases by 4% (from 37% in 2020 to 41% in 2050). On the other hand, Shopping Buildings show a 6% increase in their share of natural gas consumption (from 24% in 2020 to 30% in 2050) and a 4% decrease in their share of electricity consumption (from 44% in 2020 to 40% in 2050). In the same period, for this subsector, electricity consumption increases from 18 TJ to 19 TJ. Analyzing the breakdown of natural gas consumption for all subsectors (

Figure 14), an increase is observed for Food and Healthcare (2% and 4%, respectively), while the share of School consumption decreases by 4% (from 7% in 2020 to 3% in 2050).

As concerns electricity, Healthcare and Private Offices increase their share by +5% and 4%, respectively, while other subsectors decrease their share from 5% to 1% (

Figure 15).

Important considerations can be obtained by analyzing the trends in natural gas and electricity consumption and the trend in demand for use for each subsector. In Accommodation, the growth in presences leads to increased energy demand. However, natural gas consumption increases more rapidly than electricity, indicating greater thermal dependence and poor electrification. Food demand remains nearly stable, but natural gas consumption grows significantly, and the subsector becomes more energy intensive. The reduction in electricity and the increase in gas consumption indicate a shift toward thermal uses. School demand is constant, while the decline in consumption indicates improvements in energy efficiency, characterizing it as the subsector with the most advanced transition. In Public Buildings, characterized by unchanged demand, electricity consumption is reduced due to system optimization, but gas remains predominant for heating. In Private Offices, electricity and gas consumption both increase, but less so than end-use demand, implying an improvement in specific energy efficiency. Shopping centers are characterized by an increase in consumption, especially of natural gas, in a percentage higher than the growth in end-use demand. Finally, in healthcare, consumption growth follows that of end-use demand, but with a strong increase in natural gas

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

A sensitivity analysis was carried out by gradually increasing the purchase cost of natural gas to assess the behavior of the energy system in terms of fuel uses and technology configuration. A progressive increase (+20%, 30%, 50% and 100%) in the cost of natural gas of the reference year along the time horizon was therefore considered to assess the response to both moderate changes and extreme conditions that could occur in the event of geopolitical instability.

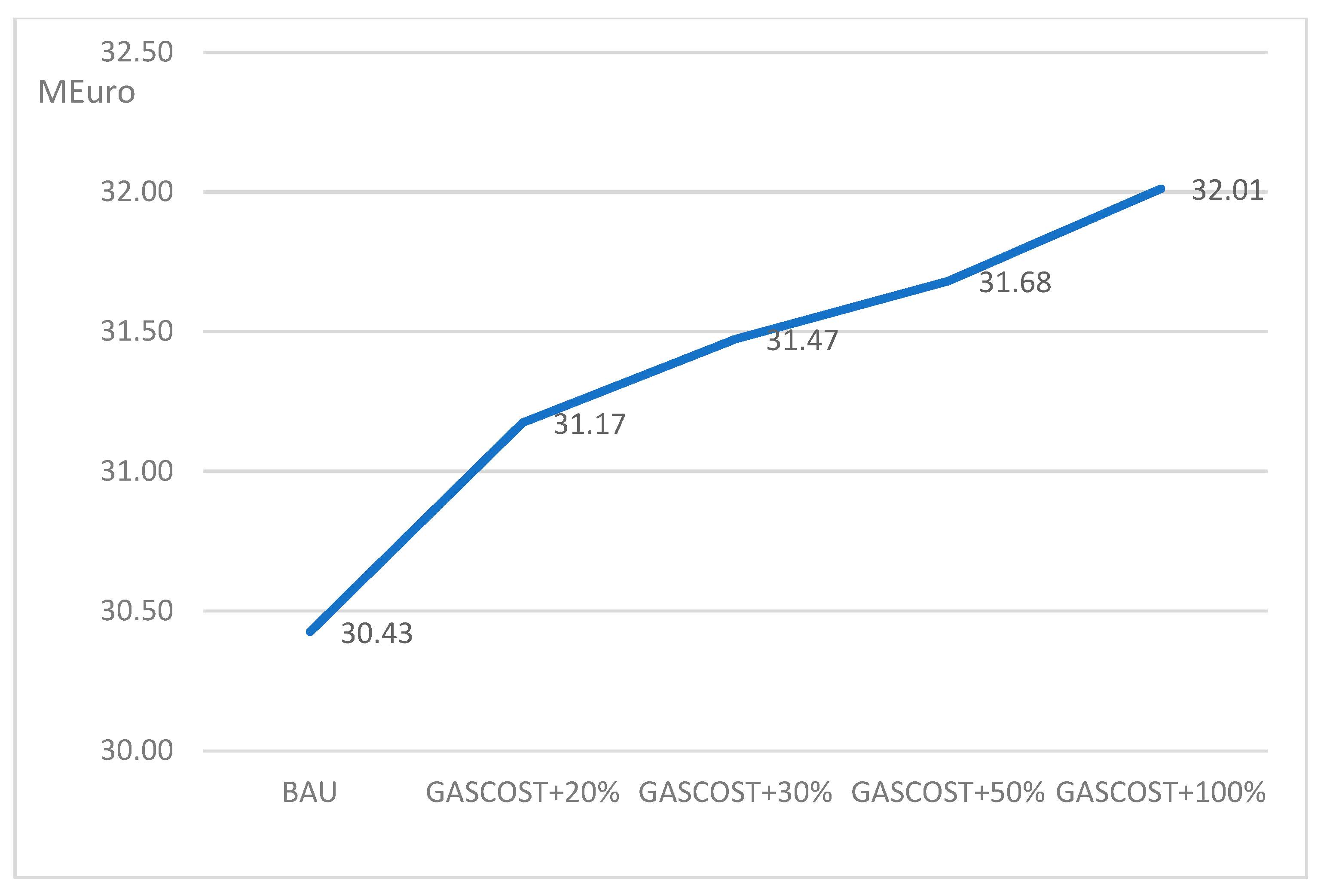

The total cost of the energy system represents the total amount of energy production and consumption expenditure over a 30-year period discounted to the base year. It includes fuel purchase costs, investment costs for new technologies, operating and maintenance costs for infrastructure and conversion and end-use technologies, minus any profits from energy sales or incentives.

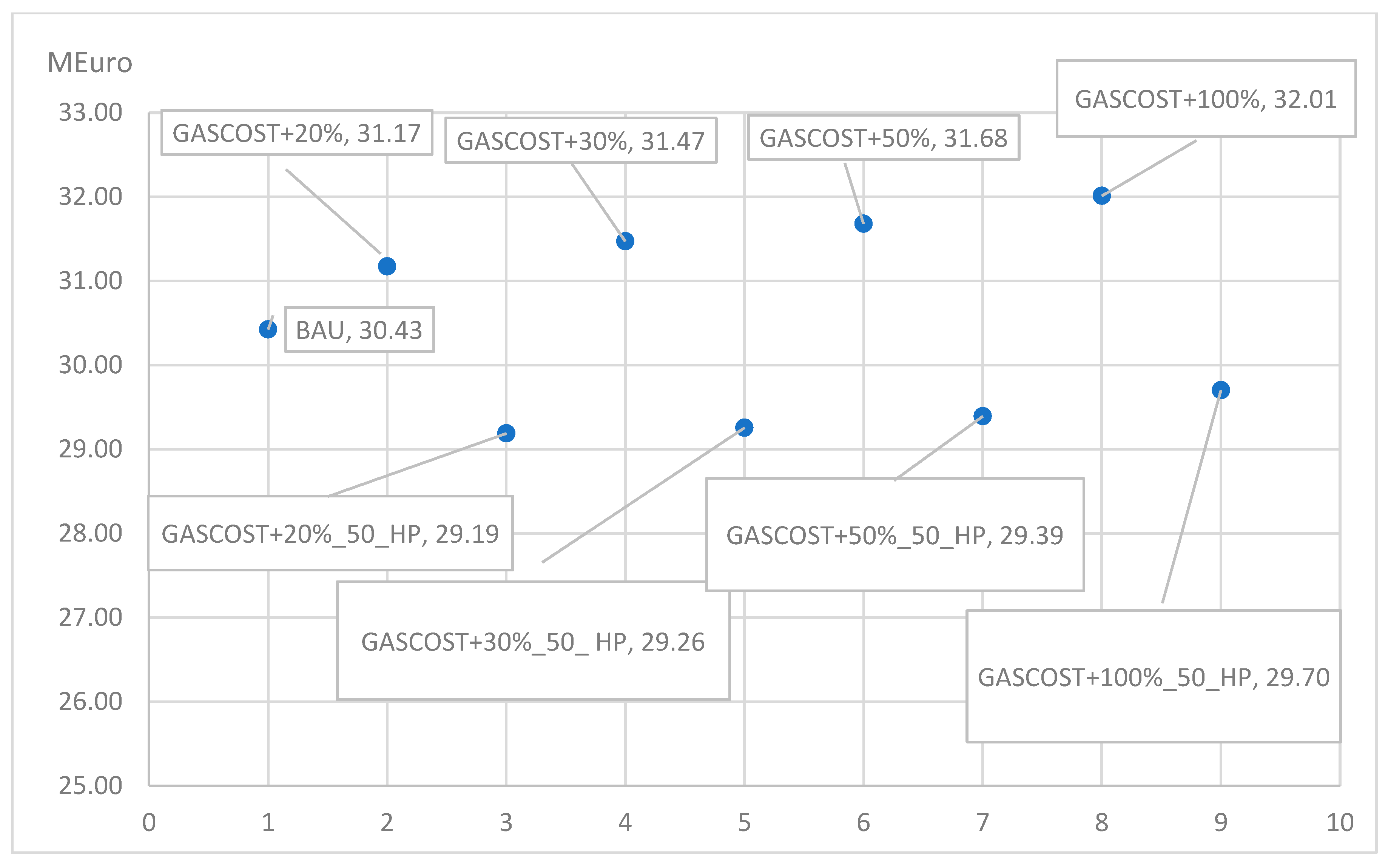

Figure 16 shows the increase in the total energy system cost due to the variations in natural gas prices. The cost increase goes from 2.5% to 5.2% compared to the BAU scenario. The variation between +2.5% and +5.2% in total system costs suggests that, despite a sharp increase in gas costs (up to 100%), the energy system has a good adaptive capacity and is not excessively vulnerable to such market shocks.

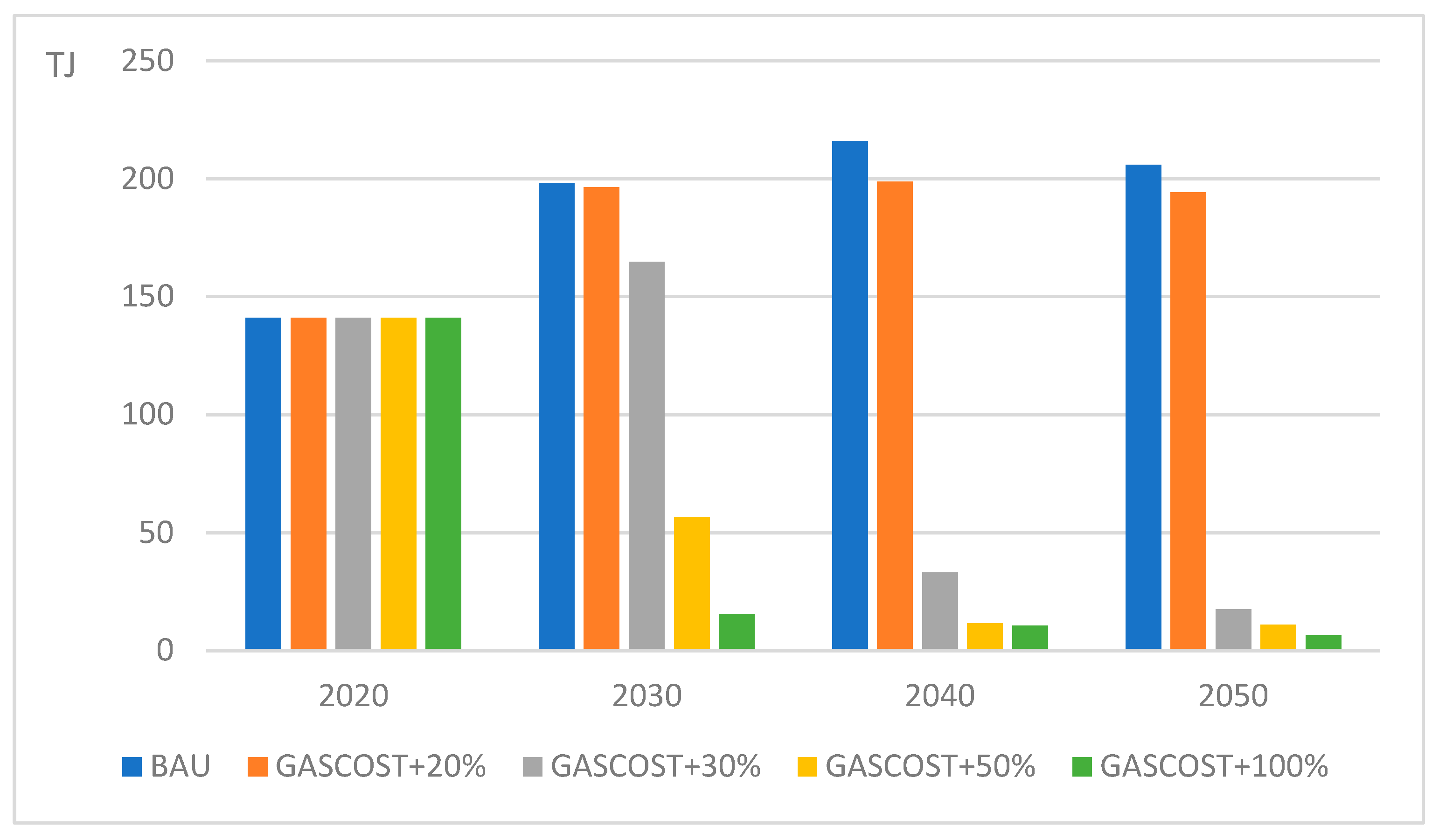

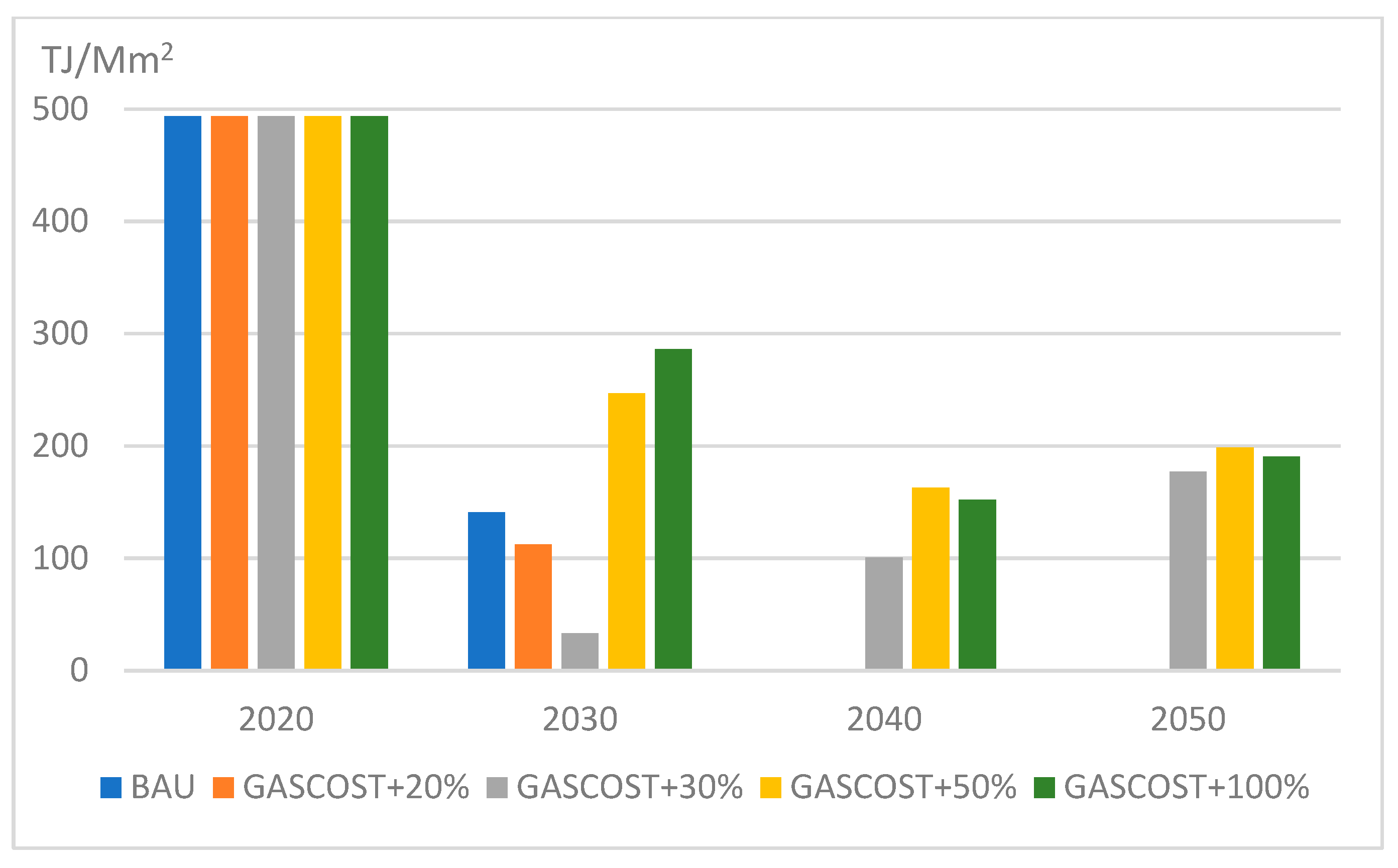

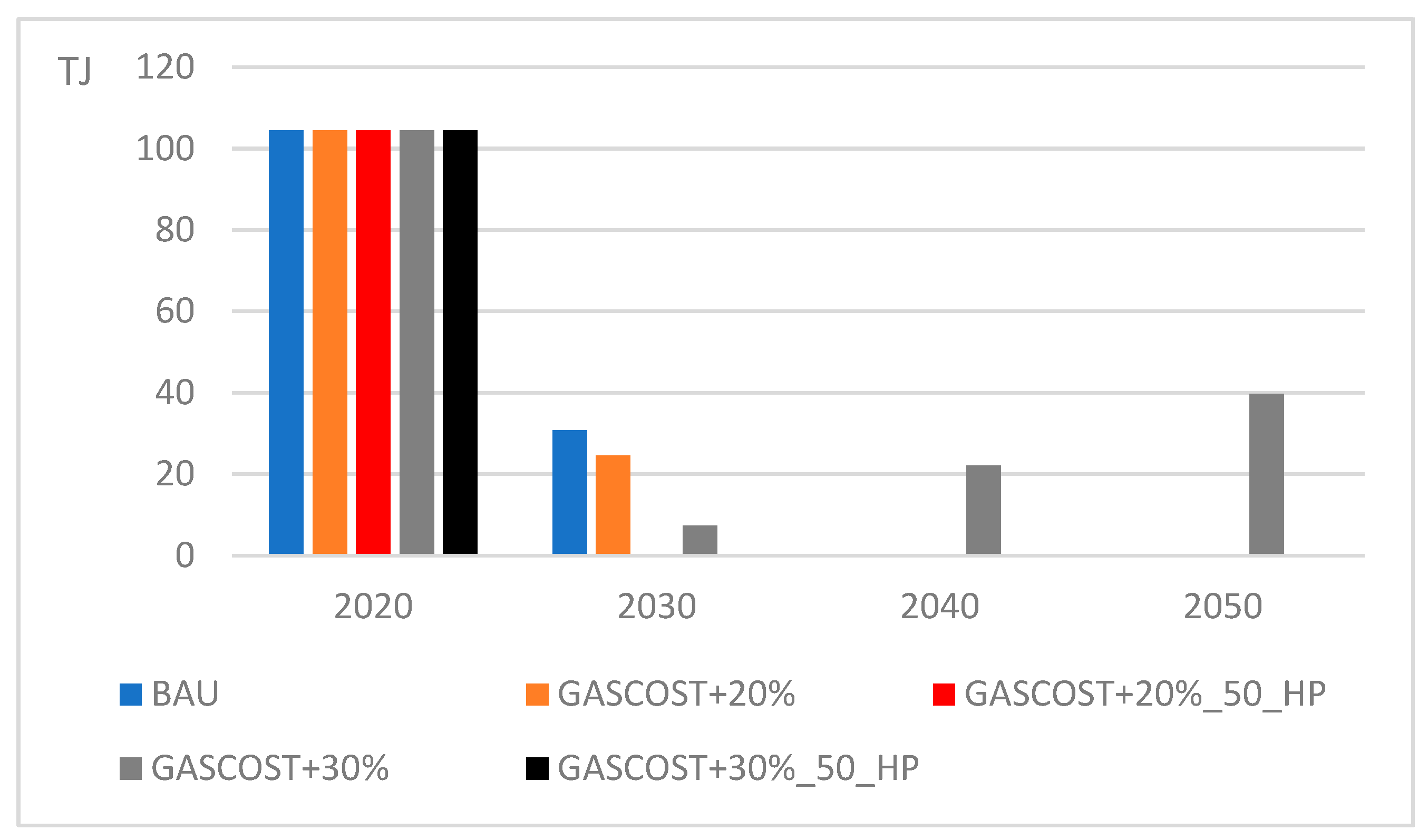

Figure 17 shows the natural gas supply trends, highlighting the decrease due to the increase in purchasing costs, which is more evident in the long term.

A 20% increase in the natural gas price is almost ineffective in terms of consumption, which decreases from 1% in 2030 to 8% in 2040. In the GASCOST + 30% case, the consumption reduction is significant, ranging from −71% to −95% in 2040. Doubling the natural gas costs (GASCOST + 100% case), the reduction in the long term is around −97%. Energy supply variations highlight the effects of the increase in natural gas prices on the fuel mix (

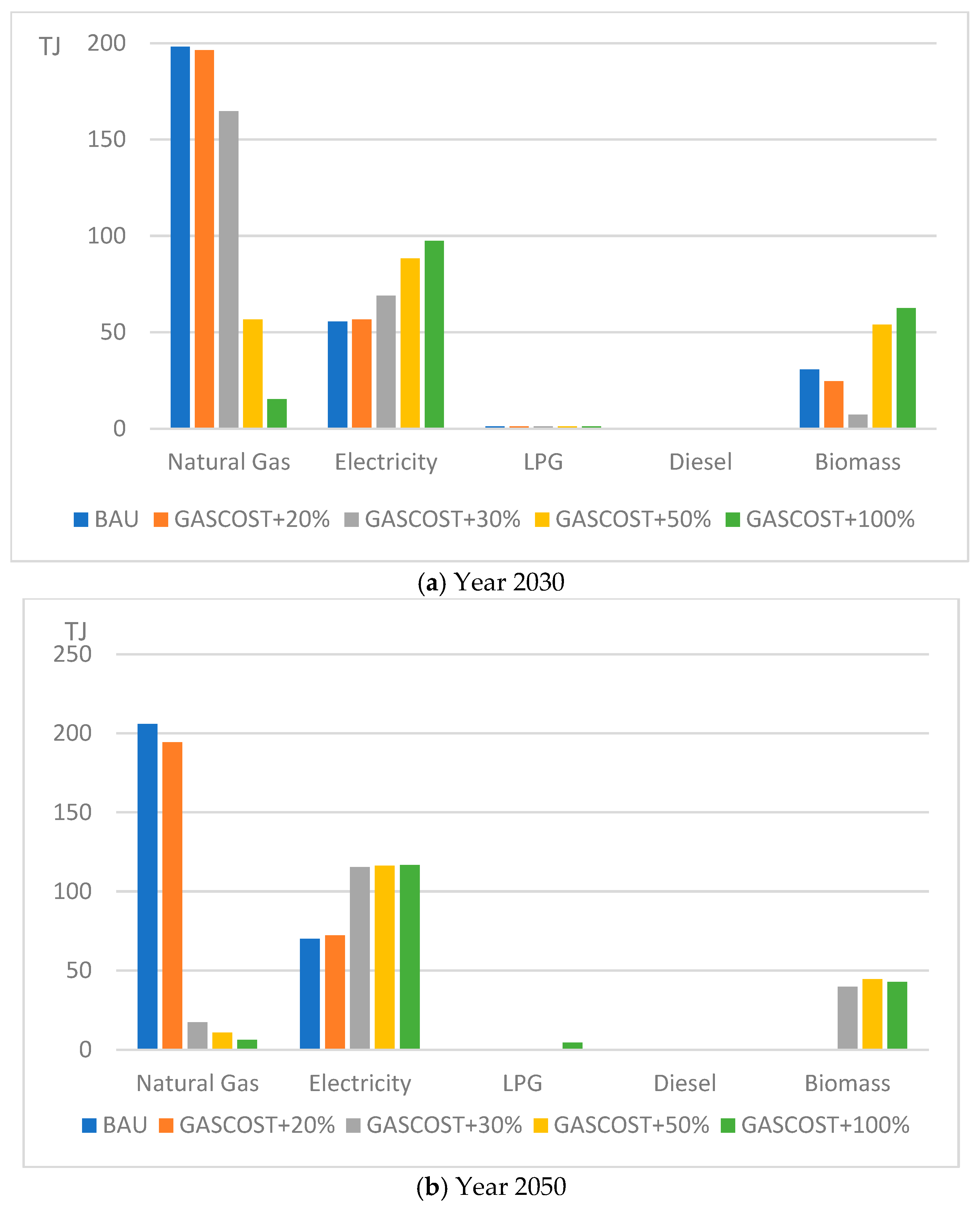

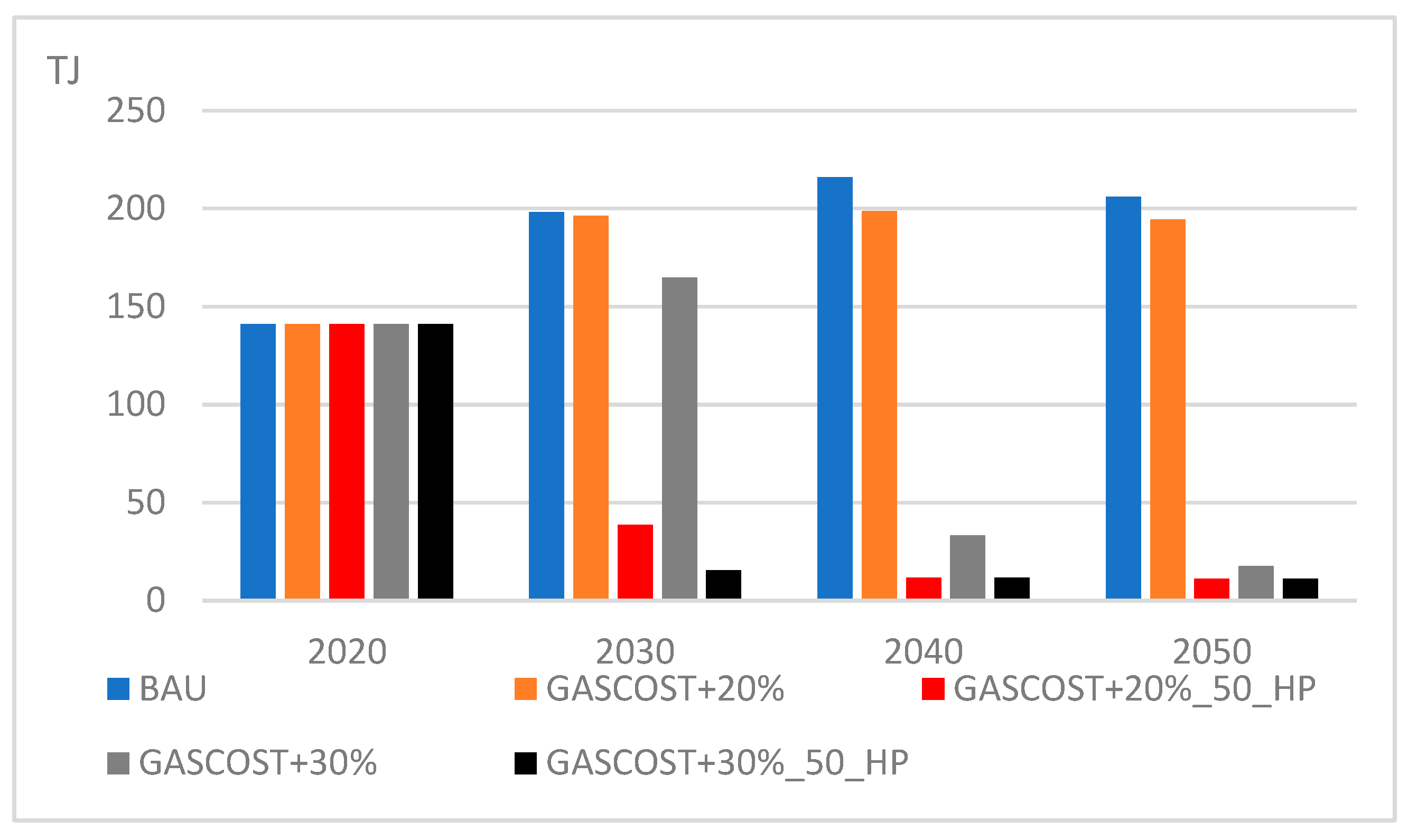

Figure 18).

Natural gas is mainly substituted by electricity and biomass. In particular, in 2030, the electricity increase ranges from 2% to 75%, while biomass decreases in the GASCOST + 20% and GASCOST + 30% cases, increasing up to 103% in the GASCOST + 100% case, achieving 62.5 TJ (

Figure 18a). In 2050, electricity increases from 3% to 67%, while biomass and LPG contributions achieve 43 TJ and 4.5 TJ, respectively, in the GASCOST + 100% case. The fuel mix in the residential sector under increasing natural gas costs is reported in

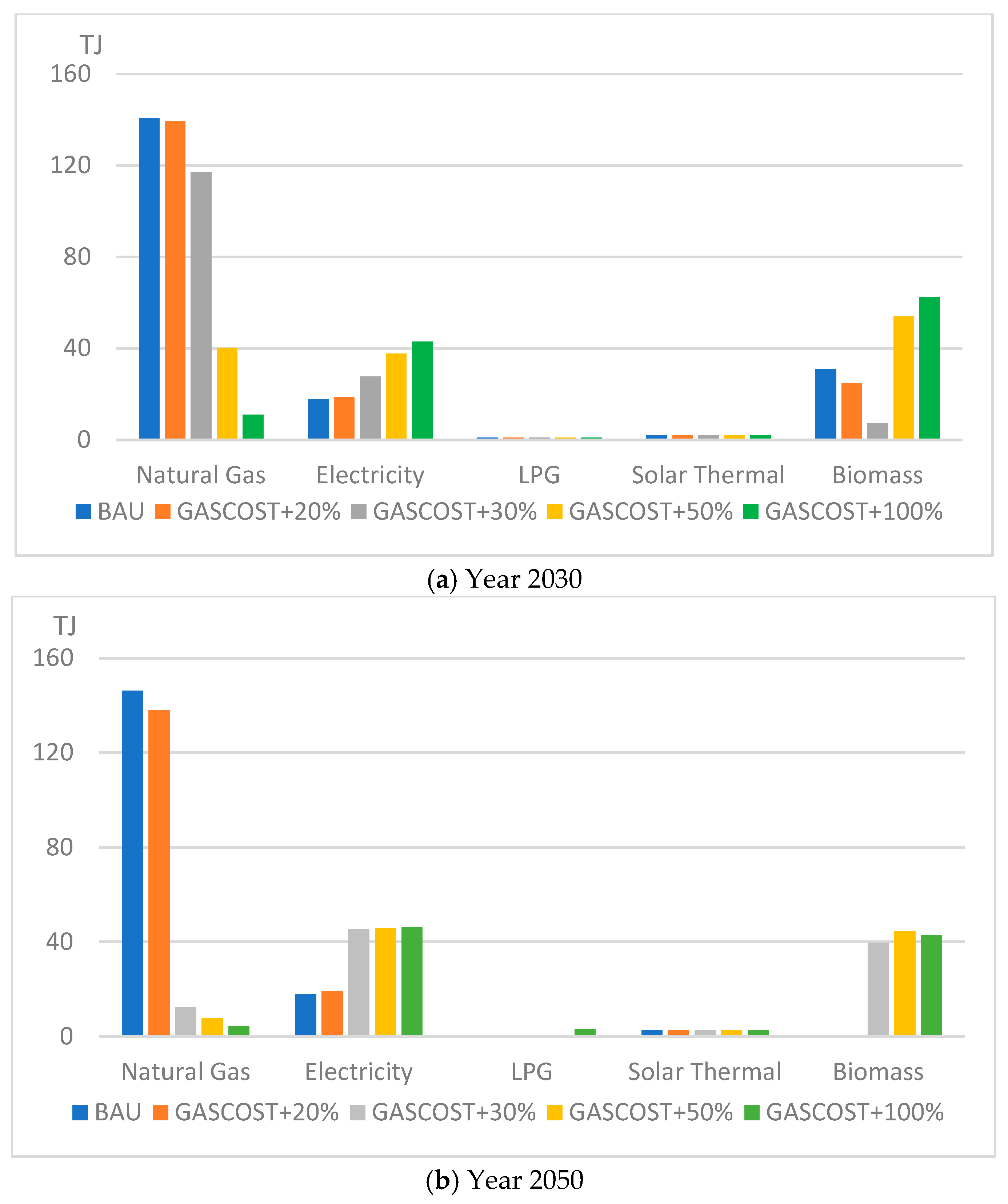

Figure 19.

In 2030 (

Figure 19a), natural gas drops to 92% (GASCOST + 100% case) and is substituted by electricity (+141%) and biomass (+103%). The contributions of LPG and solar thermal are constant, at 10 TJ and 2 TJ, respectively. In 2050, electricity consumption increases by +157% and that of biomass by 138%. Solar thermal consumption is constant (around 3 TJ) and LPG consumption is zero in all cases except GASCOST + 100%, which achieves 3 TJ, contributing 3% to the total residential energy consumption.

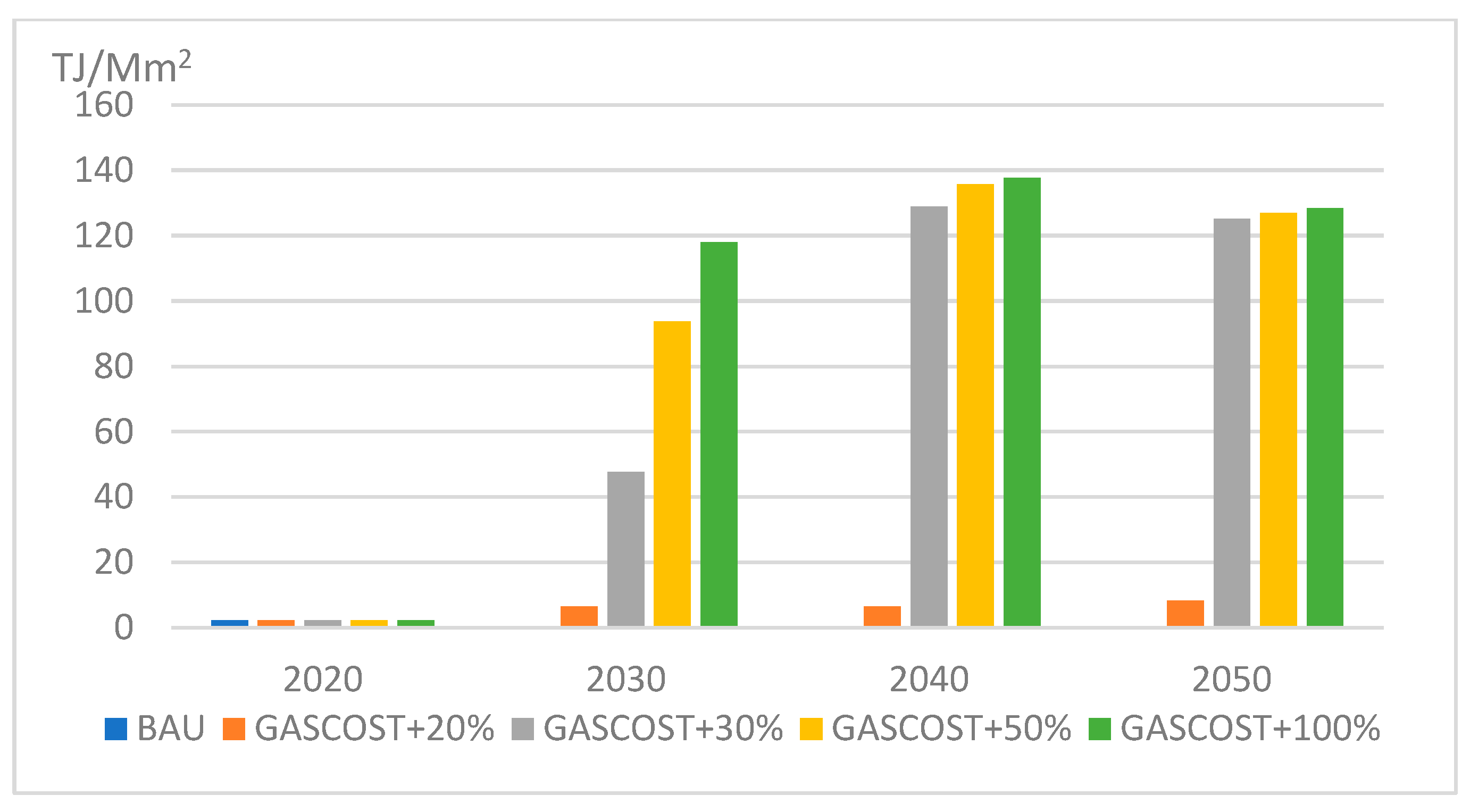

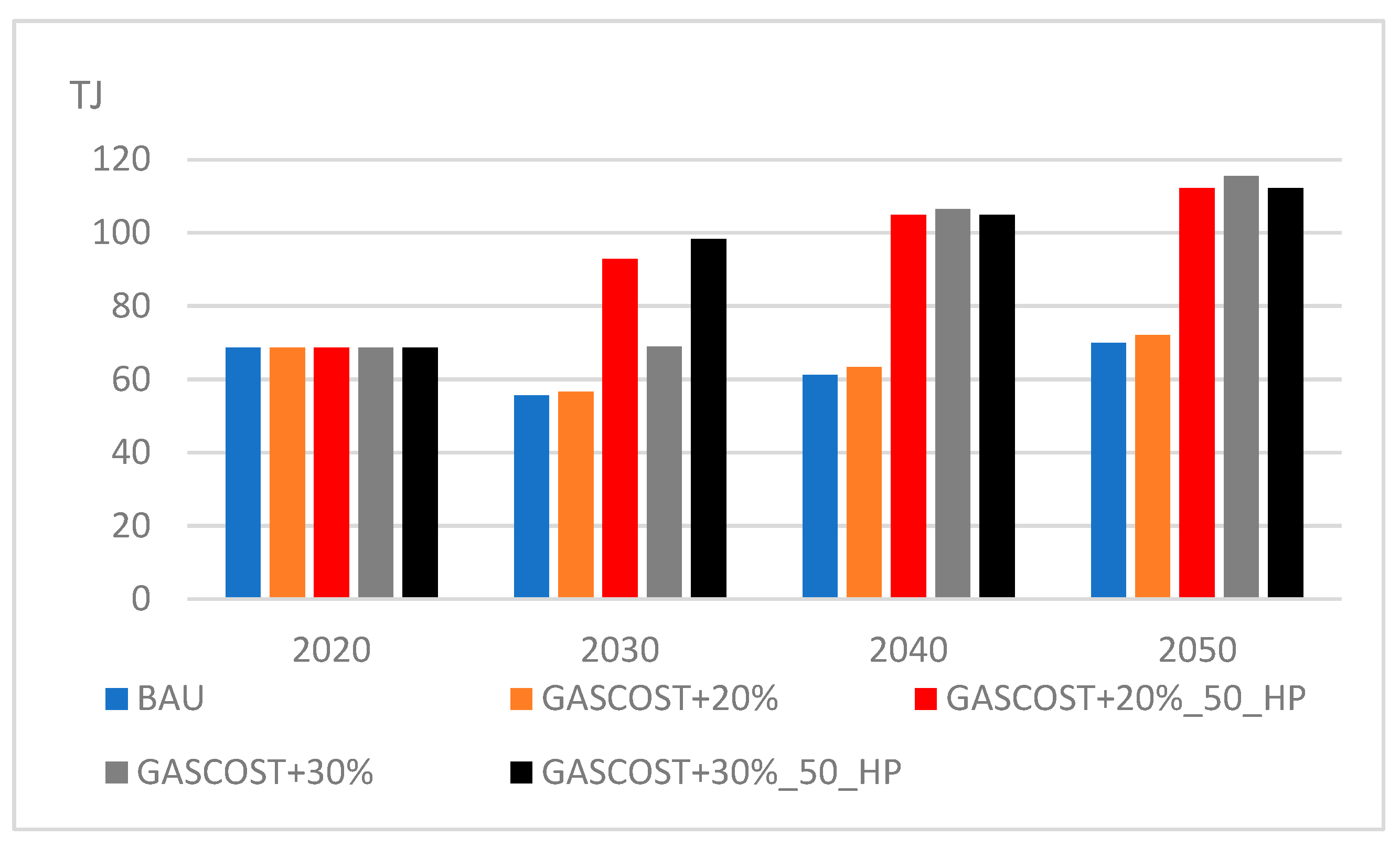

The increase in electricity consumption, which compensates for the decline in natural gas consumption, is linked in particular to the use of heat pumps for space and water heating, as also demonstrated by the increase in space electricity consumption per square meter, which goes from 2.3 TJ (BaU) to a maximum of 140 TJ (GASCOST + 100% case, year 2040) (

Figure 20).

Biomass also contributes to meeting space heating demand, showing a downward trend and gaining importance in 2040 and 2050, when the price of gas increases by at least 30% (

Figure 21).

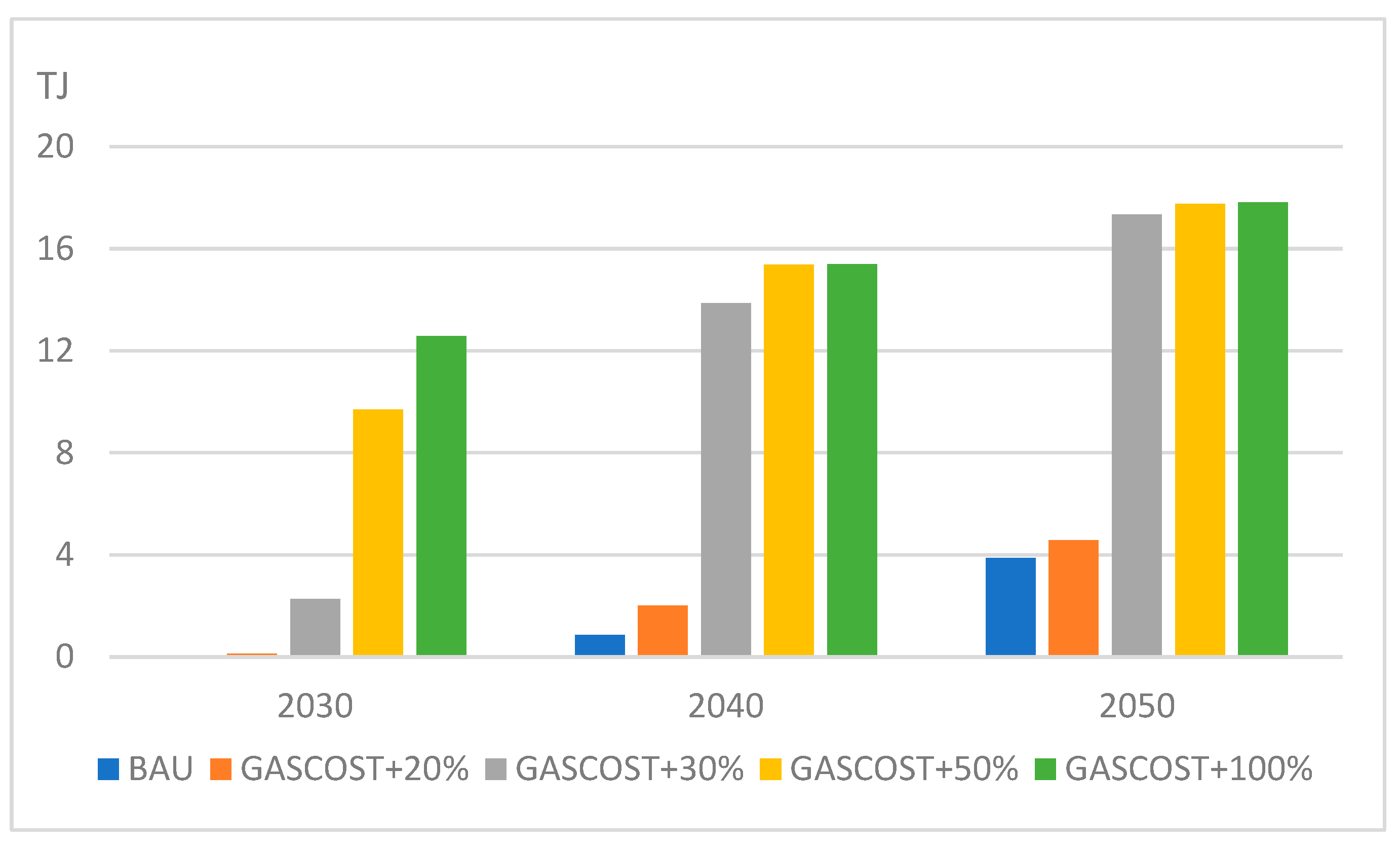

In the tertiary sector, the increase in electricity consumption driven by the rise in natural gas prices is lower than in the residential sector, achieving +29% in 2050, when the natural gas price is doubled (GASCOST + 100% case) (

Figure 22).

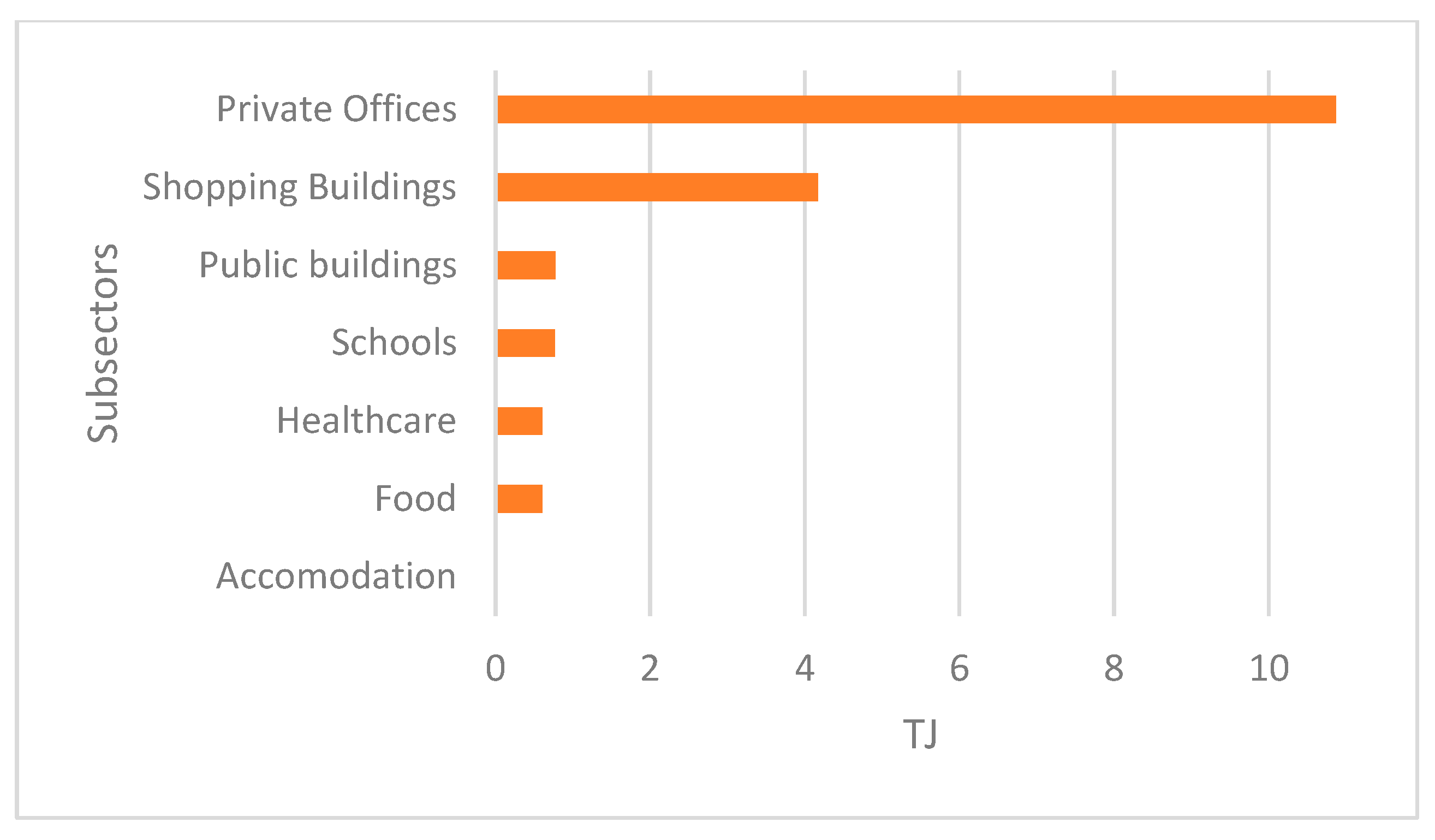

Figure 23 shows the expected distribution among subsectors in 2050. Private Offices and Shopping Buildings still account for the largest share (84%), while Schools and Public Buildings account for about 4% each, Food and Healthcare about 3% each and Accommodation 0.15%.

Considering the results of the sensitivity analysis, further investigation was conducted under the assumption of a 50% non-repayable grant for the purchase of heat pumps in both the residential and tertiary sectors, alongside a gradual increase in natural gas purchase costs (

Table 13).

Figure 24 shows the trend in total system costs considering a 50% reduction in investment costs of heat pumps and a gradual increase in the purchase cost of natural gas. In all four cases, the system’s total cost is lower than the cost of the BaU scenario. The lowest total system cost (29.19 MEuro) is obtained in the GASCOST + 20%_50_HP case, corresponding to a 50% reduction in heat pumps investment cost and a 20% increase in the purchase cost of natural gas. The total cost of the system reaches 29.70 MEuro in the GASCOST + 100%_50_HP case, corresponding to a 100% increase in the purchase cost of natural gas and a 50% reduction in the heat pumps investment cost.

The 50% incentive on the purchase of heat pumps is an effective solution to mitigate the economic impact of an increase in the cost of natural gas, bringing the total cost of the system to be even lower than the BAU scenario. The 50% incentive on the purchase of heat pumps is an effective solution for mitigating the economic impact of an increase in the cost of natural gas, resulting in total system costs that are even lower than in the BAU scenario. The results suggest that incentives for energy efficiency technologies, such as heat pumps, can reduce overall energy system costs, even in unfavorable scenarios of rising gas prices. This provides a strong argument for public policies that promote energy efficiency improvements at various scales.

The following figures show the results of the GASCOST + 20%_50_HP and GASCOST + 30%_50_HP cases, in which the cost of natural gas increased by 20% and 30%. The results obtained with a further increase in the cost of gas are comparable to those obtained in the GASCOST + 50% and GASCOST + 100% cases, with no reduction in the purchase cost of heat pumps. When the investment cost of heat pumps is halved, biomass boilers, formerly selected as the most economical technology without any reduction in the price of heat pumps, from a 30% increase in the cost of natural gas, are discarded. Biomass is therefore no longer used for space heating in the residential sector, as illustrated in

Figure 25.

The reduction in heat pump investment costs leads also to a more rapid reduction in natural gas consumption, as shown in

Figure 26, which shows the trend in gas consumption considering a 20% and 30% increase in natural gas purchase costs with and without the reduction in heat pump investment costs (GASCOST + 20%, GASCOST + 20%_50_HP, GASCOST + 30%, GASCOST + 30%_50_HP cases). In the GASCOST + 20%_50_HP case, natural gas consumption is reduced by 80% in 2030 and by 94% in 2040 and 2050 compared to the GASCOST + 20% case. In the GASCOST + 30%_HP case, the reduction is 91% in 2030, 65% in 2040 and 37% in 2050 compared to the GASCOST + 30% case. In the GASCOST + 30% case, natural gas consumption is lower than in the BaU scenario as early as 2040.

Concerning electricity, the GASCOST + 20%_HP case, in which the cost of natural gas increases 20% and the investment cost for heat pumps is halved, shows a significant increase in electricity consumption (64% in 2030, 65% in 2040 and 55% in 2050) compared to the GASCOST + 20% case, whose consumption is very similar (almost identical) to that of the BAU scenario (

Figure 27). In 2030, the increase in electricity consumption in the GASCOST + 30%_HP case is 42% compared to the GASCOST + 30% case. This difference is not evident in 2040 and 2050, where the trends for the GASCOST + 30% and GASCOST + 30%_HP cases are very similar. In the GASCOST + 30%_HP case, there is a slight reduction in consumption of 1.6% in 2040 and 2.8% in 2050 compared to the GASCOST + 30% case, due to the use of more efficient heat pumps than in the GASCOST + 30% case, promoted by lower investment costs.

5.4. Greenhouse Gas Emissions

The Kyoto Protocol identified seven greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming: carbon dioxide (CO

2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF

3). Among these, carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide are the main contributors. Carbon dioxide is by far the most important anthropogenic greenhouse gas, as it currently accounts for the largest share of warming associated with human activities. In fact, globally, total CO

2 emissions linked to energy use increased by 0.8% in 2024, contributing to an atmospheric CO

2 concentration of 422.5 ppm, 50% higher than pre-industrial levels. This increase was driven by the rise in natural gas emissions in 2024 (180 Mt CO

2, +2.5%), which was the main contributor to the growth in global carbon emissions [

65,

66].

As concerns the Tito energy system, the analysis focused on CO2 emissions, which are mainly determined by natural gas consumption in residential and tertiary sectors and a contribution associated with the electricity import.

Regarding CO

2 emissions associated with electricity import by the municipality of Tito (

Table 14), taking into account the national fuel mix for electricity production in 2020 [

67] and CO

2 emission factors for each energy fuel, it is possible to estimate first of all the contribution of each fuel to imported electricity and therefore the value of total CO

2 emissions associated with electricity imports emissions in the base year (1.89 kton CO

2). Assuming the national fuel mix constant over the time horizon, the CO

2 emissions associated with electricity import are 1.93 kton CO

2 in 2050.

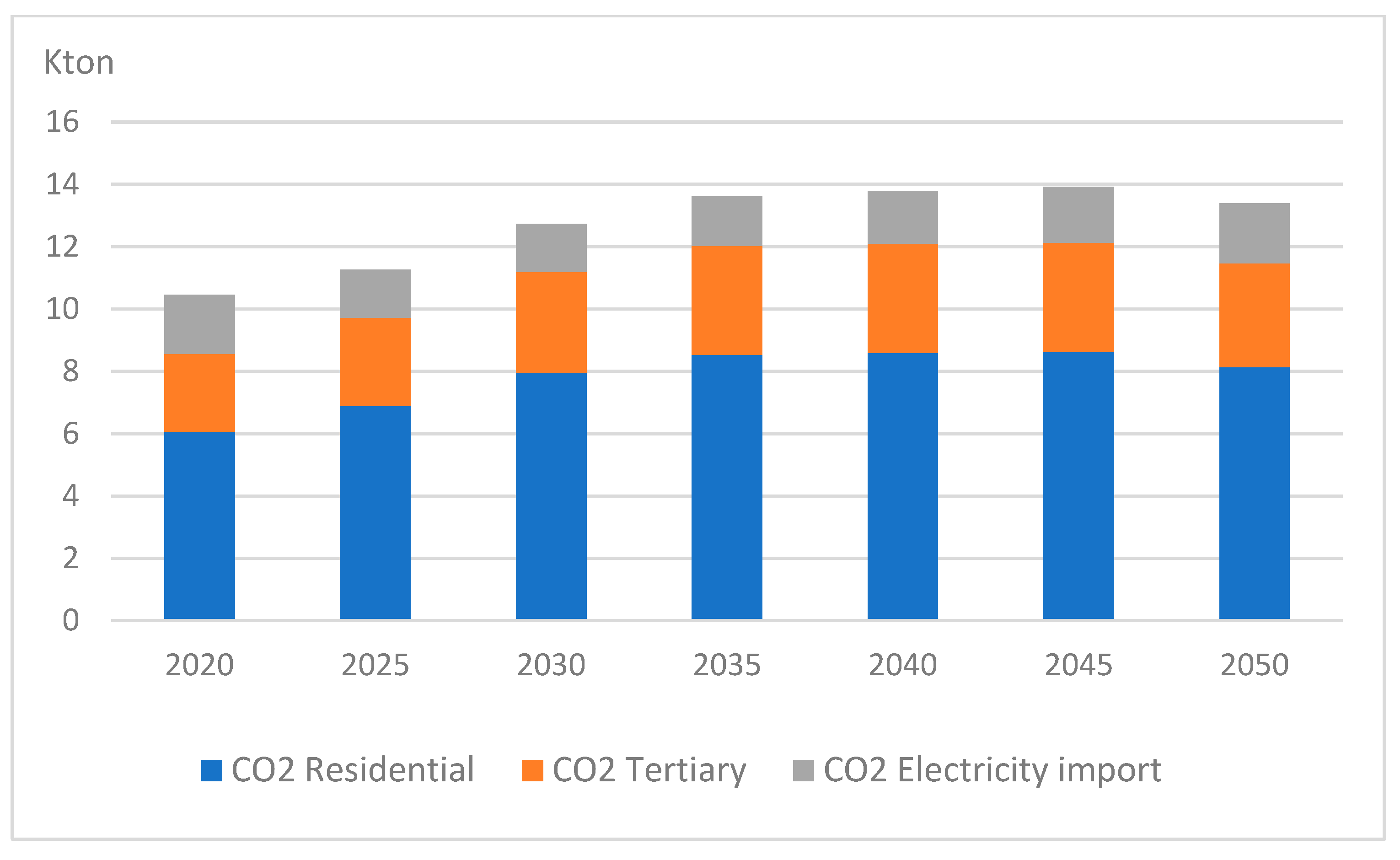

The values obtained are added to CO2 emissions from the residential and tertiary sectors, so that the emissions value in 2050 is 13.4 kton compared to 10.5 kton in the base year.

As shown in

Figure 28, CO

2 emissions increase till 2045 (+33%) and start declining by 2050, with an overall increase of around 28% with respect to 2020. The residential sector accounts for 61%, highlighting its main contribution, while the tertiary sector emits 25% and the electricity supply the remaining 14%. These percentages remain almost constant over the time horizon. The slight decrease in the last time-period is mainly due to a decrease in natural gas consumption.

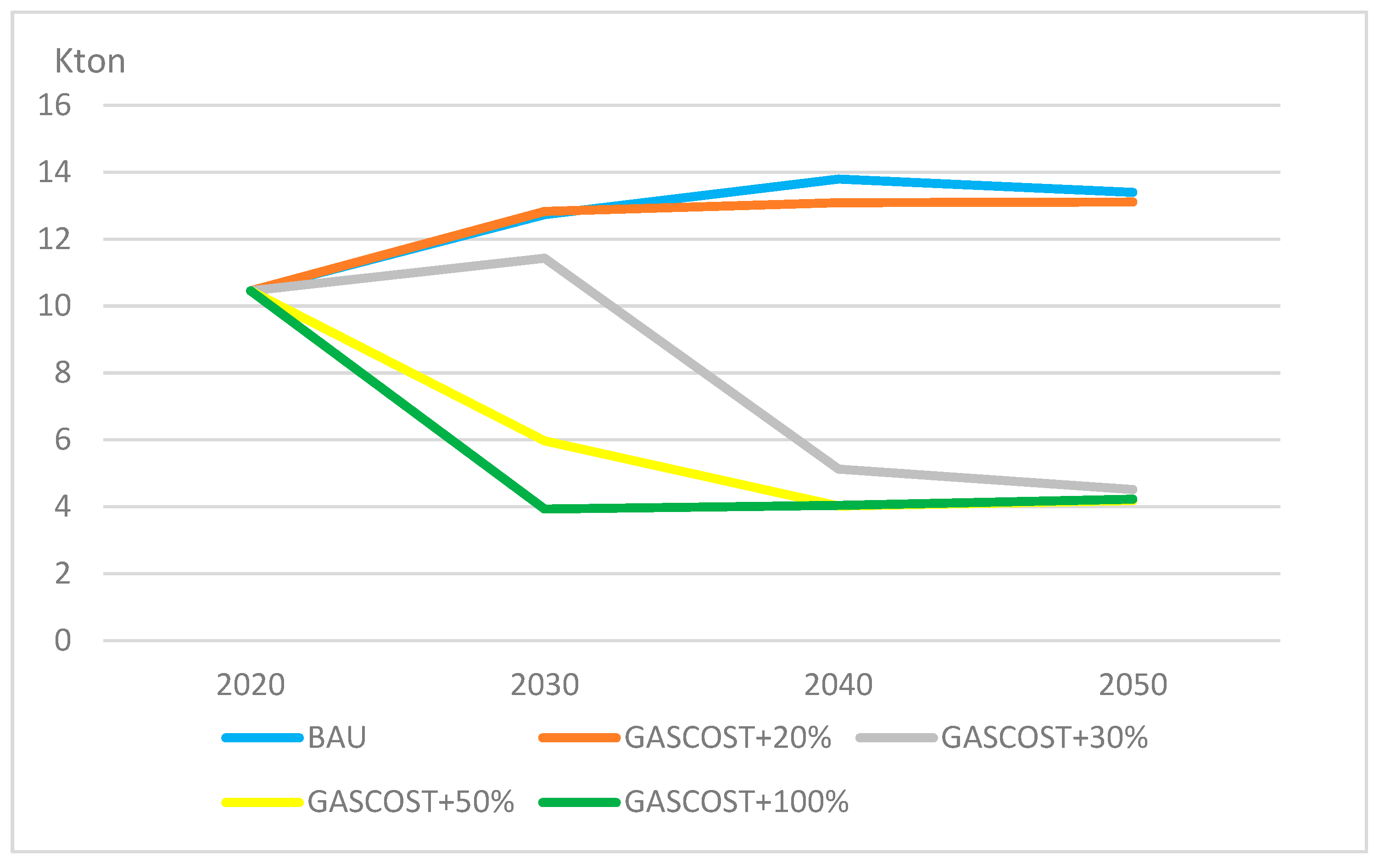

As for the BAU scenario, in the sensitivity analysis, the fuel mix for electricity supply is assumed to be similar to that of the base year in order to estimate the associated CO

2 emissions. The decrease in natural gas consumption due to the increasing gas prices drives a decrease in CO

2 emissions (

Figure 29).

In 2030, the decline will be significant when the price of natural gas is at least 50% higher than the current selling price (−53% compared to emissions in the BaU scenario). By 2040, a 30% increase will already be effective (−63%), while in 2050, the reduction in CO2 emissions will vary from 66% (GASCOST30% case) to 68% (GASCOST50% and GASCOST100% cases). This confirms the effectiveness of a 30% increase in the price of natural gas in the long term in bringing about a steady decrease in CO2 emissions.

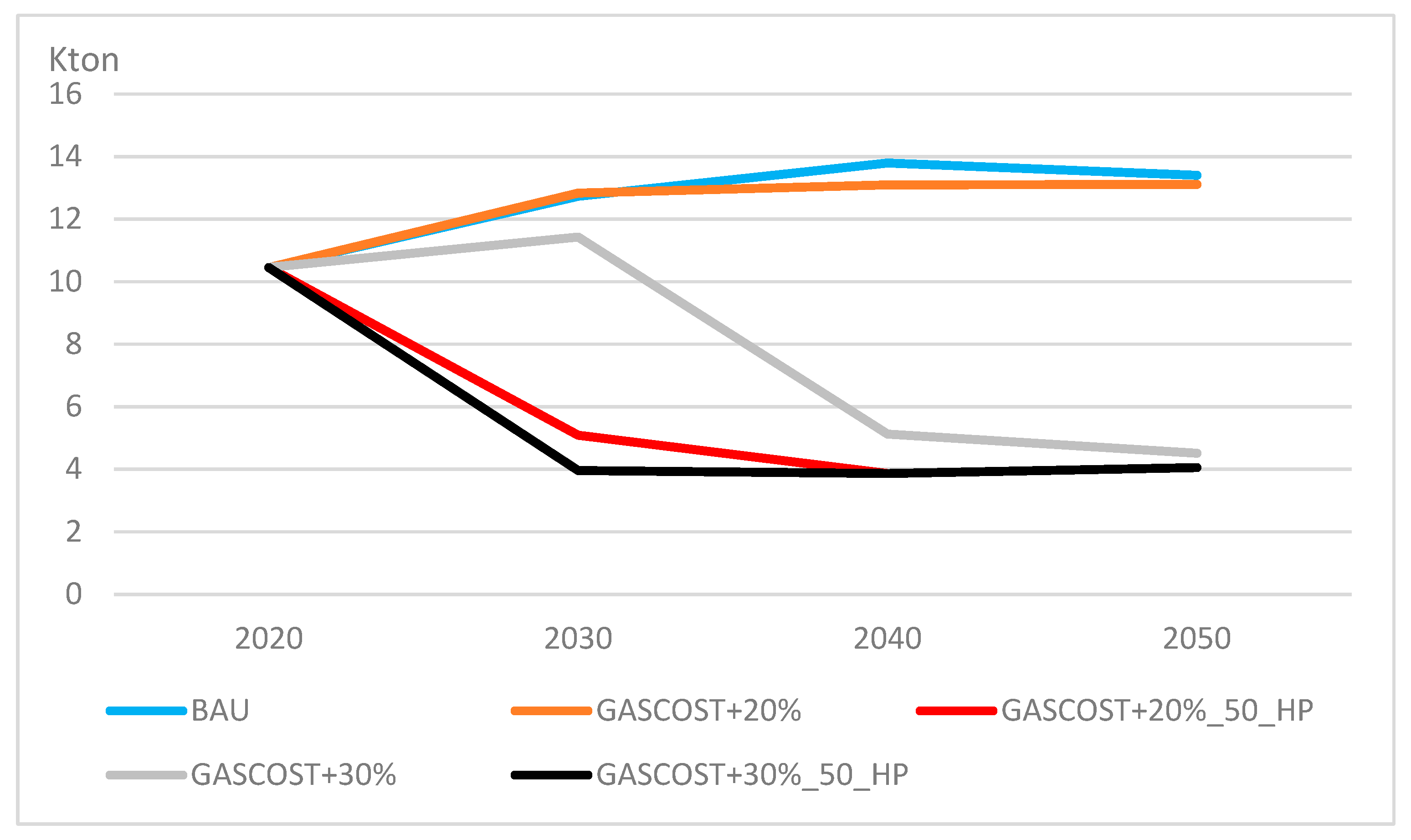

Analyzing the cases with the reduction in heat pump investment costs (

Figure 30), it is possible to see a reduction in CO

2 emissions of 60% by 2030, 70% by 2040 and 69% 2050 in the GASCOST + 20%_HP case compared to the GASCOST + 20% case. In the GASCOST + 30%_HP case, CO

2 emissions are reduced by 65% compared to the GASCOST + 30% case in 2030, while in subsequent periods, values are very similar, with a difference of −1.3 kton in 2040 and −0.5 kton in 2050.

6. Conclusions

The implementation of the municipal energy system model based on the ETSAP-TIMES framework articulated a potential evolution pathway under the BAU scenario, which reflects current national policies and energy consumption trends, paving the way to further investigation of future contrasting scenarios.

The current energy landscape highlights the heavy reliance of Tito’s energy system on fossil fuels in 2020, particularly on natural gas, despite the municipality’s leading position in the Basilicata region for installed PV capacity. Biomass is the most used source for residential heating, followed closely by natural gas.

In the BaU scenario, total energy consumption decreases by 15% by 2050. It is observed that there is a noticeable overall decline in biomass, LPG and diesel use, which are gradually phased out by 2040 and 2035, respectively, driven by regulatory pressures and the phasing out of more carbon-intensive sources. A substantial growth of renewables is also observed. In particular, electricity production from PV systems increases by 99% over the time horizon, going from 3.4 TJ in 2020 to 6.7 TJ by 2050, illustrating a shift towards renewable energy that can help align with national climate goals. Also, solar thermal exhibits encouraging growth, increasing by 187% by 2050, although its overall contribution remains relatively modest in absolute terms. Despite the PV growth, natural gas remains the dominant energy carrier throughout the time horizon. This is mainly due to the financial relief on natural gas bills for households in the Basilicata region due to the presence of oil field exploitation activities. Natural gas consumption increases 44% by 2050 compared to 2020 and is particularly dominant for space heating and cooking demand in the residential sector, indicating a slower transition away from fossil fuels in these critical end-uses. The residential sector trends toward reduced overall energy use by 30% by 2050, reflecting improved efficiency or behavioral shifts, but without a significant reduction in overall emissions. All residential subsectors show progress in efficiency and reduced specific consumption. In this sector, biomass, the prevailing fuel in 2020 (44%), is entirely substituted by natural gas (88% contribution) by 2040. There is limited electrification and integration with renewable sources. The energy transition process to achieve climate neutrality is therefore incomplete.

Energy consumption in the tertiary sector increases by 30% over the time horizon, particularly in the Healthcare and Accommodation subsectors (expected increases of +190% and +78%, respectively, by 2050). The tertiary sector also shows an energy mix with a predominance of natural gas, while electricity grows moderately. Food, Shopping Centers and Healthcare are the most energy-intensive and least efficient over time. These are priority subsectors for efficiency and decarbonization policies. The tertiary sector is not moving toward a real energy transition toward electrification. On the contrary, the increase in gas prices suggests that the tertiary sector is not reducing its dependence on fossil fuels but rather combining it with increased electricity consumption.

The continued reliance on natural gas leads to a 28% increase in CO2 emissions by 2050 compared to 2020, peaking in 2045. The residential sector is the primary contributor, accounting for 61% of these emissions. The slight emissions downturn by mid-century suggests some progress toward decarbonization, potentially aided by improved energy efficiency.

The sensitivity analysis investigates the impact of gas prices and the effectiveness of subsidies to promote technology innovation. Increasing the price of natural gas is highly effective at reducing consumption and the associated CO2 emissions. A 30% price increase reduces long-term consumption significantly, leading to a 66% drop in CO2 emissions by 2050 compared to the BaU scenario. Electricity (powering heat pumps) and biomass emerge as the primary substitutes. Combining a moderate natural gas price increase (+20%) with a 50% non-repayable grant for heat pumps proves to be the most effective policy lever. This approach drastically reduces natural gas consumption and CO2 emissions (a 69% reduction by 2030) while simultaneously lowering the total energy system cost below that of the BaU scenario.

The overall conclusion is that the BaU pathway only partially aligns with decarbonization targets. On the other hand, in 2030, modeled pathways allow the 55% CO2 emissions reduction target to be met and exceeded by 2030, when the price of gas increases by 100% (−69%), while a 20% increase in the price of gas is already effective when combined with 50% reduced investment costs in heat pumps, enabling an 60% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030. This emphasizes the need for more aggressive policy actions and technological innovation to significantly reduce fossil fuel dependency and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon energy system.

The modeling approach can be applied for energy–environmental planning at the municipal scale, and in the case of the Tito municipality, the model constitutes a useful tool to support decision-making.

The next step in this research involves modeling and assessment of the effectiveness of developing a Renewable Energy Community, in accordance with European and Italian directives, under the assumptions of different scenarios. This analysis is particularly relevant for understanding the drivers and barriers in a real case study.