Coupled Electromagnetic–Thermal Modeling of HTS Transformer Inrush Current: Experimental Validation and Thermal Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Enhancing the reliability of HTS transformers by improving the understanding of the conditions for superconductivity loss initiation and the dynamics of this phenomenon.

- Designing more efficient cryogenic cooling systems capable of compensating temporary thermal overloads.

- Optimizing winding design through the selection of appropriate geometries and improvements in HTS conductor architecture.

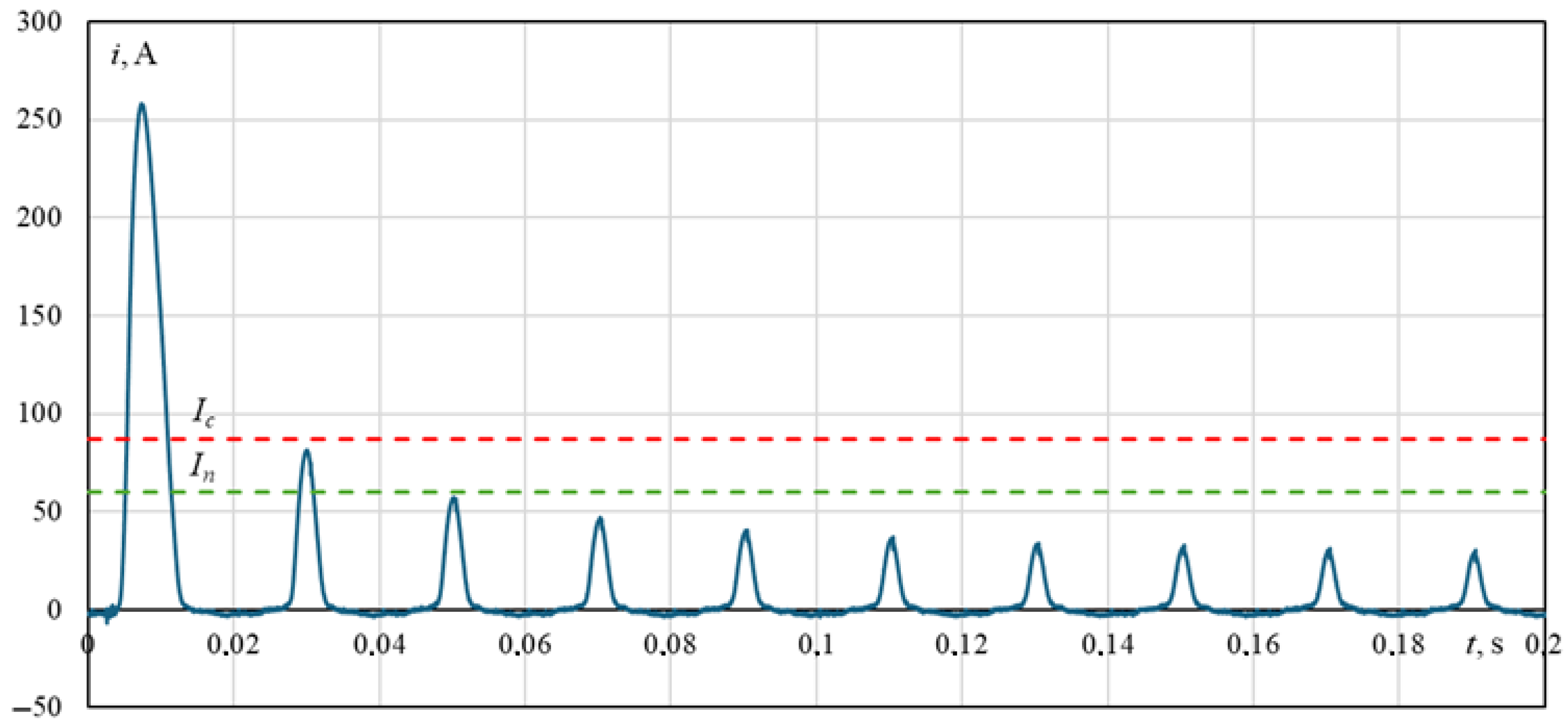

- Developing new methods for inrush current limitation that minimize the risk of exceeding the permissible temperature of HTS windings.

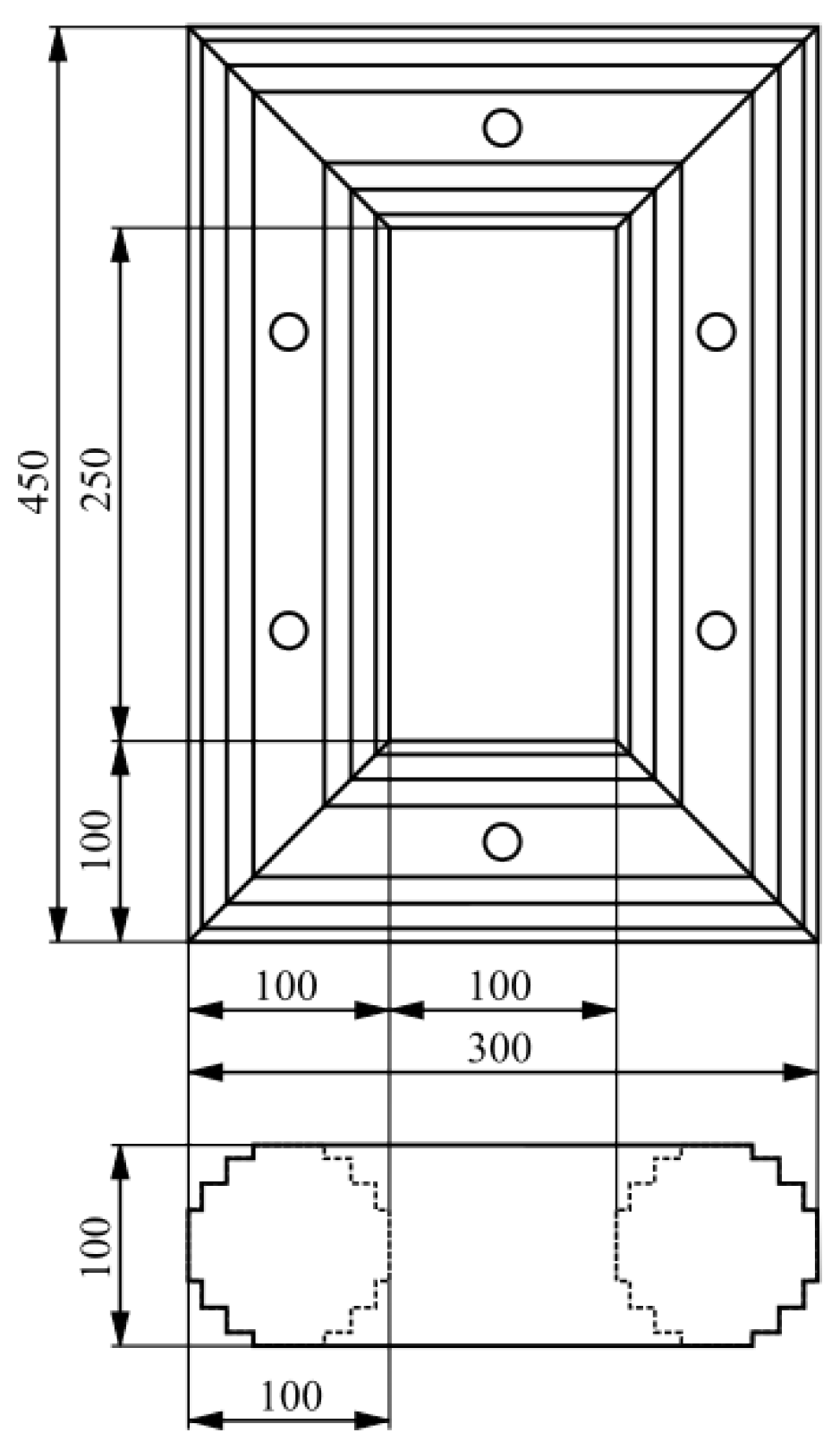

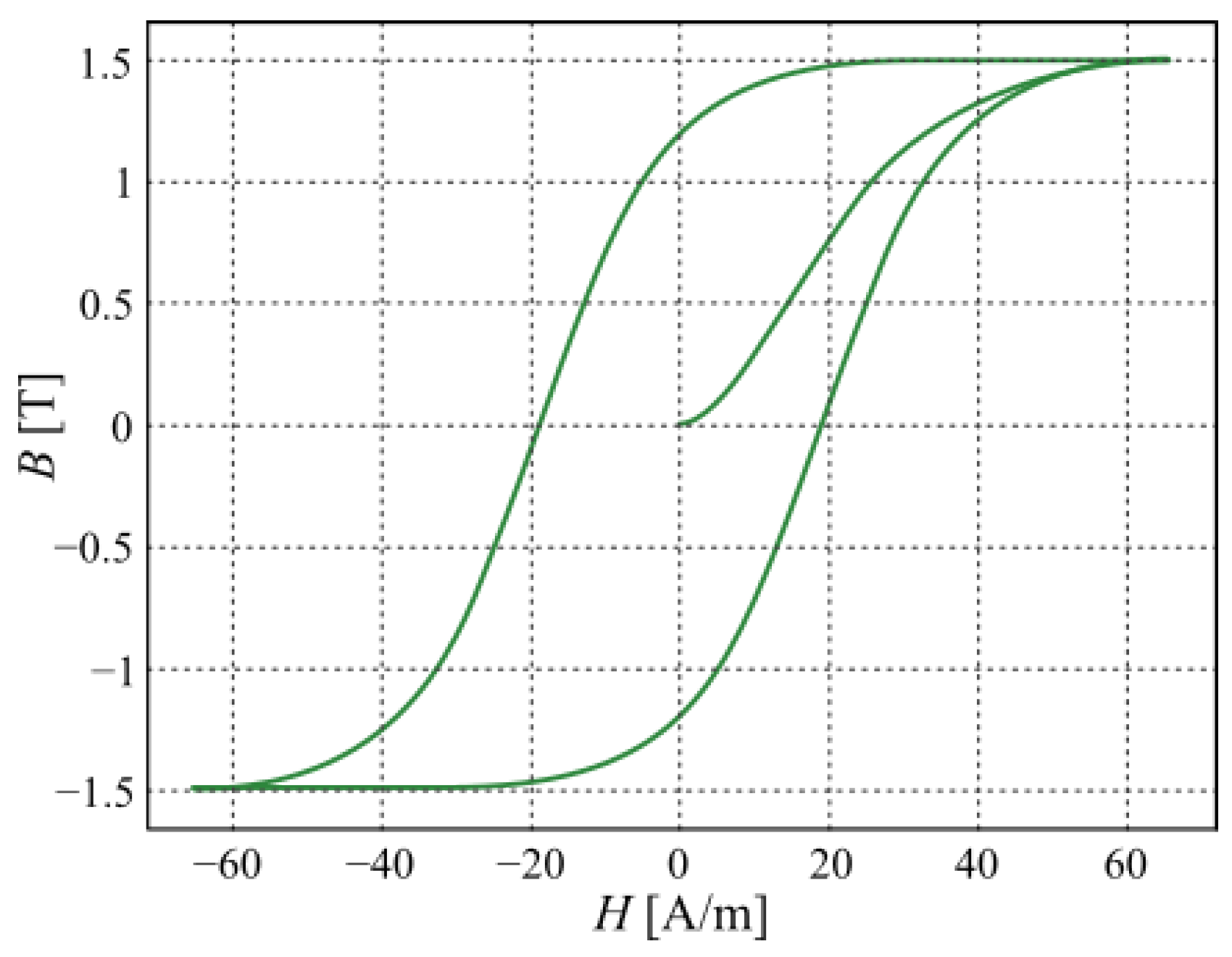

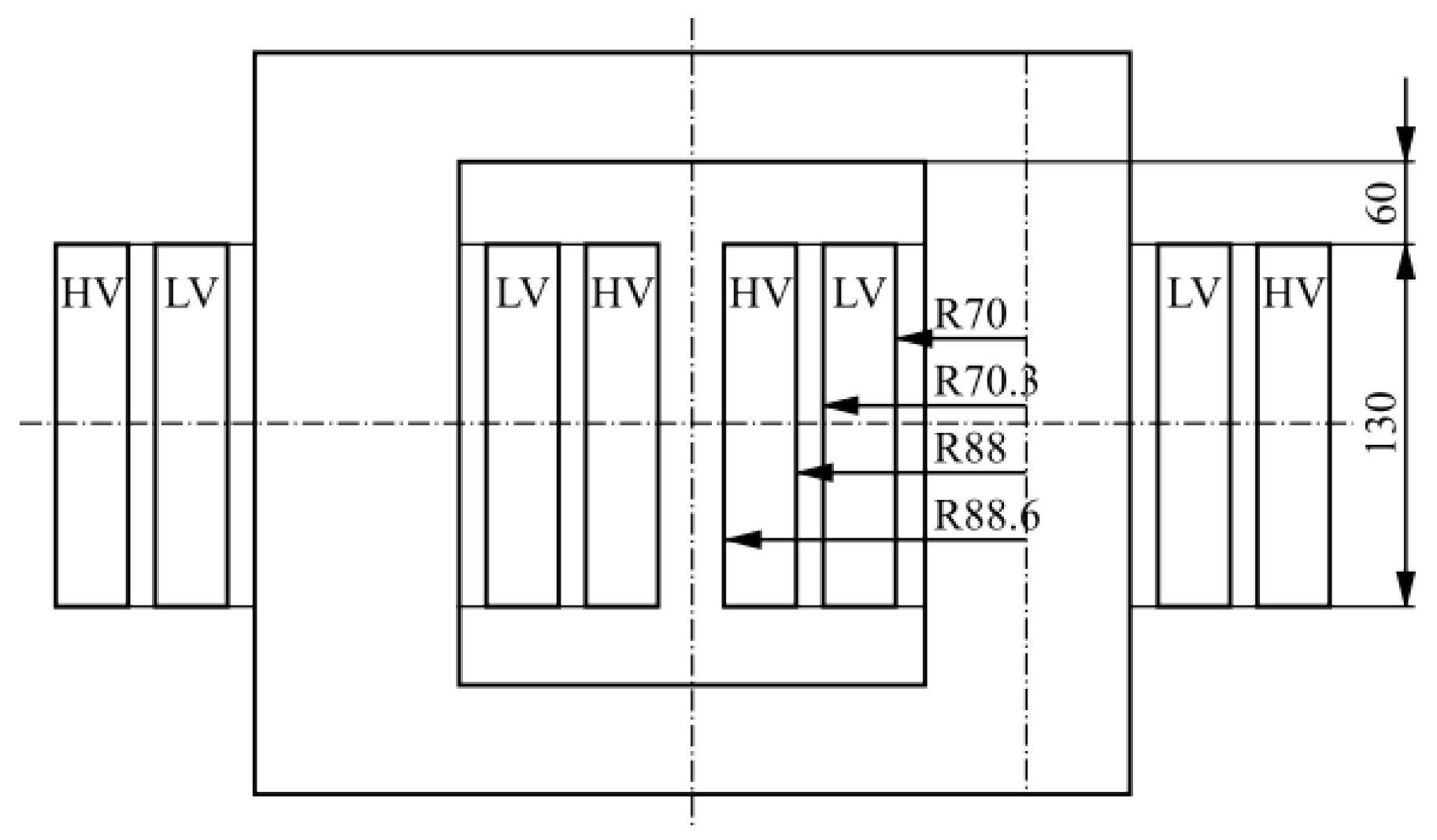

2. Object of the Study

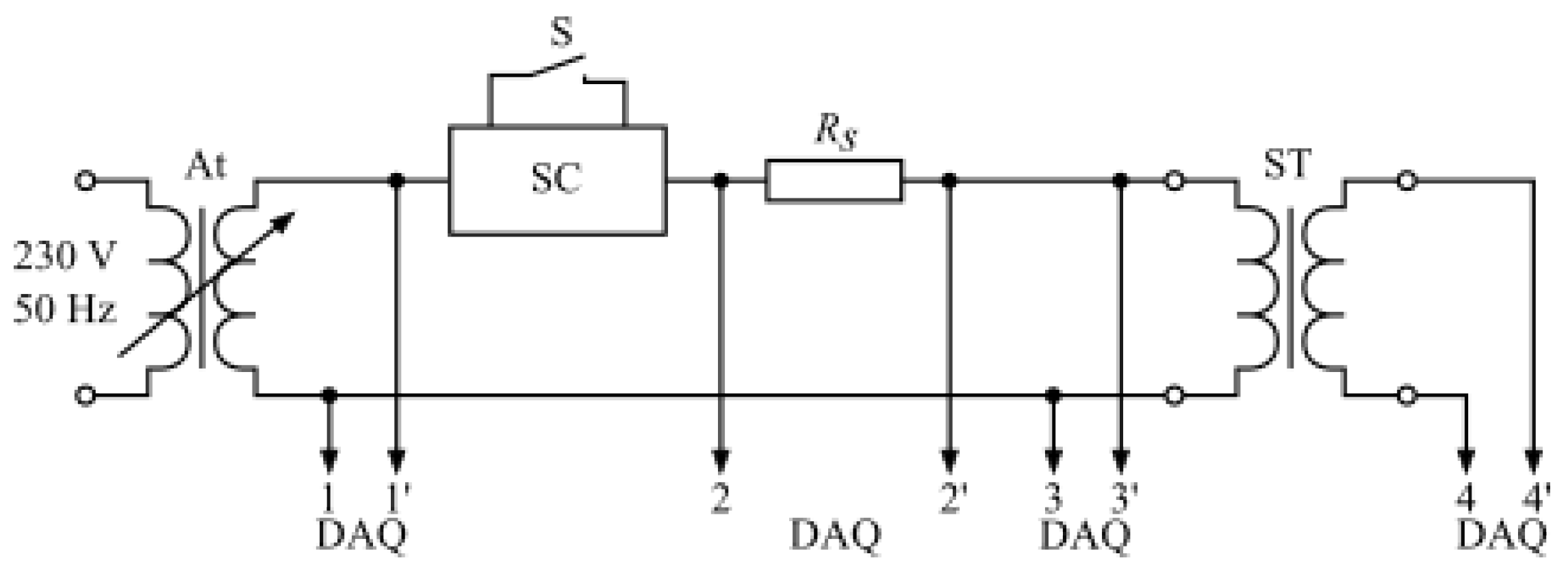

3. Experimental Setup and Results

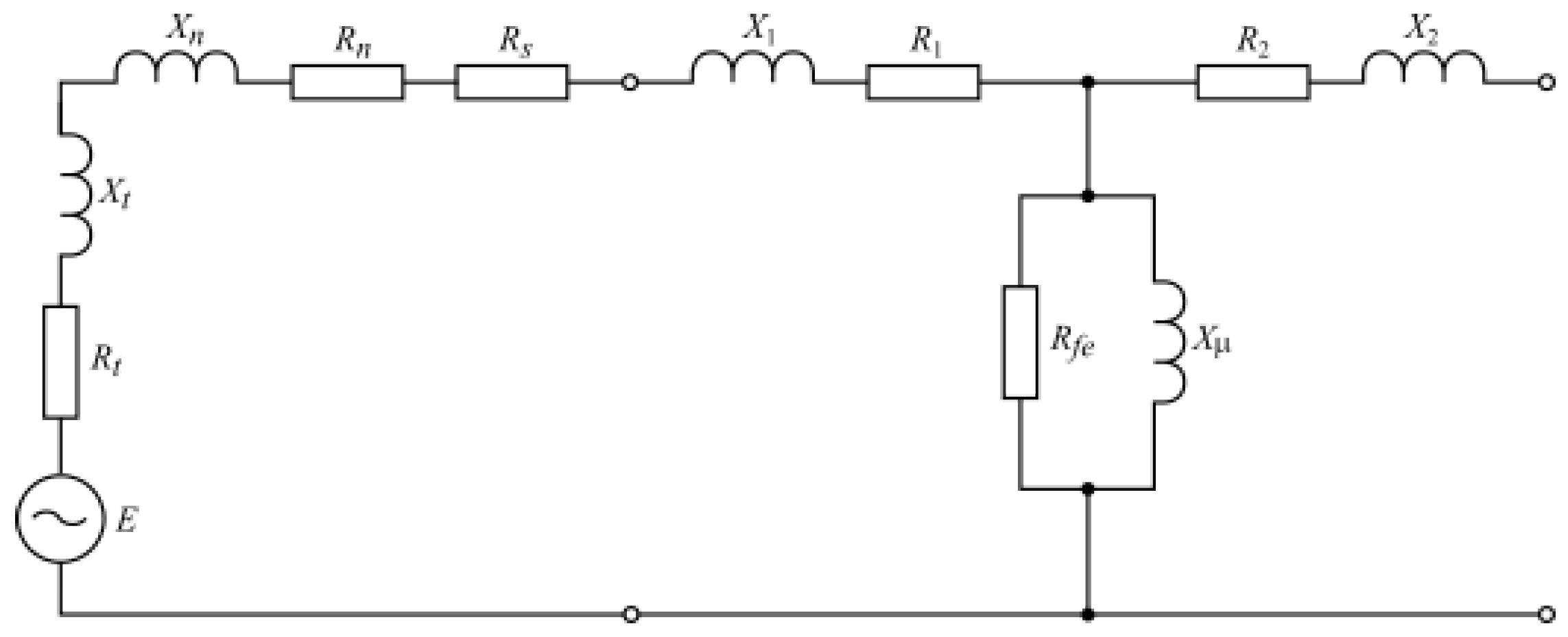

4. Mathematical Model

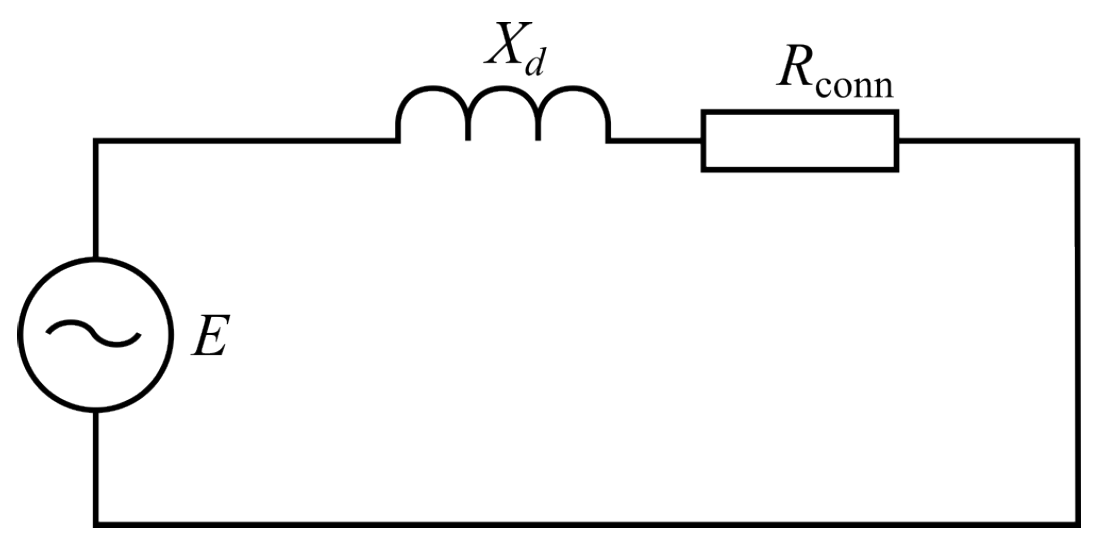

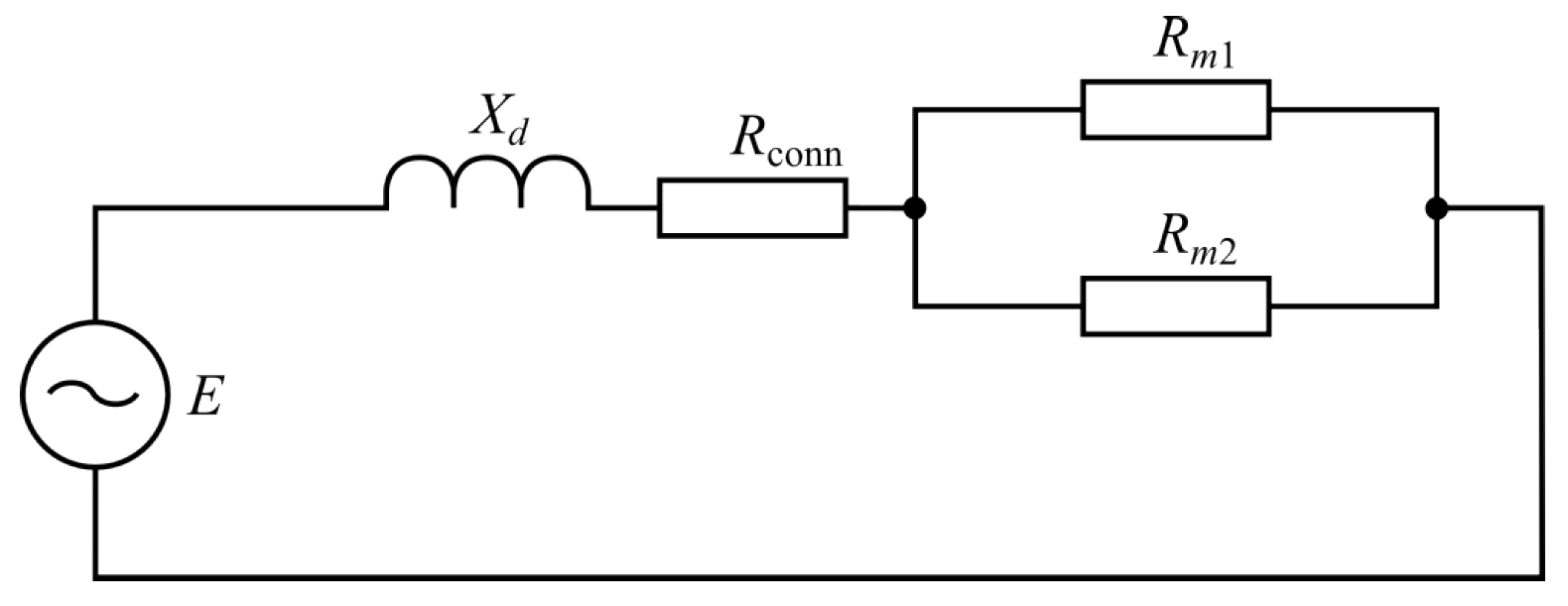

- —Total resistance of the circuit elements (wires, connectors) [];

- —Differential (local) inductance of the magnetizing circuit, dependent on the operating point on the B–H magnetization curve [], as well as on the inductances of the circuit elements.

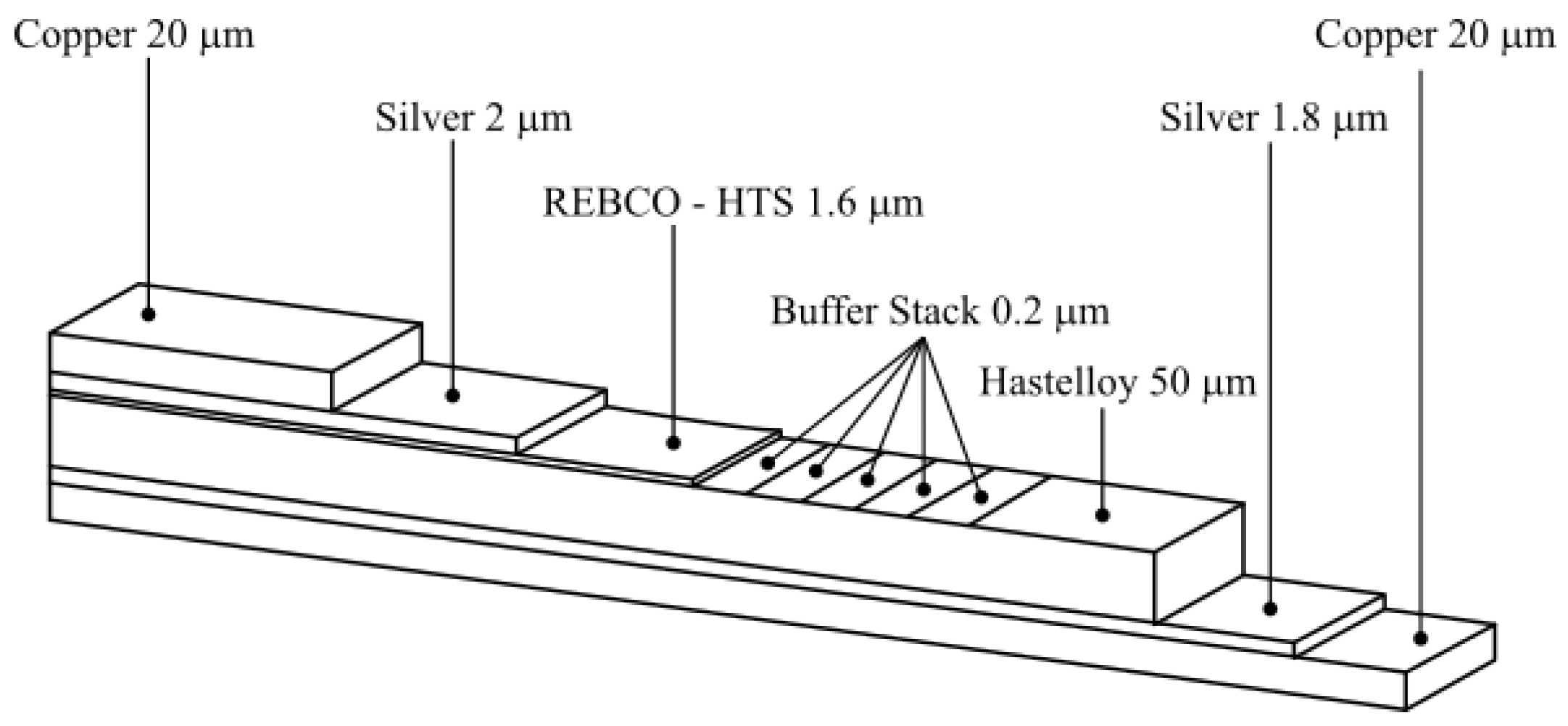

4.1. Superconducting Tape Model

4.2. Superconducting State

- —Supply voltage applied to the transformer winding at time t [];

- —Magnetizing current of the HTS transformer winding at time t [];

- —Magnetic flux in the transformer core at time t [];

- —Resistance of electrical connections and additional circuit elements (terminals, supply leads, connectors) [];

- N—Number of turns of the transformer winding [–];

- —Time derivative of the magnetic flux, corresponding to the electromotive force induced in the winding [].

- —Initial value of the magnetic flux in the transformer core, corresponding to the residual flux [].

- A—Cross-sectional area of the transformer core through which the magnetic flux passes [];

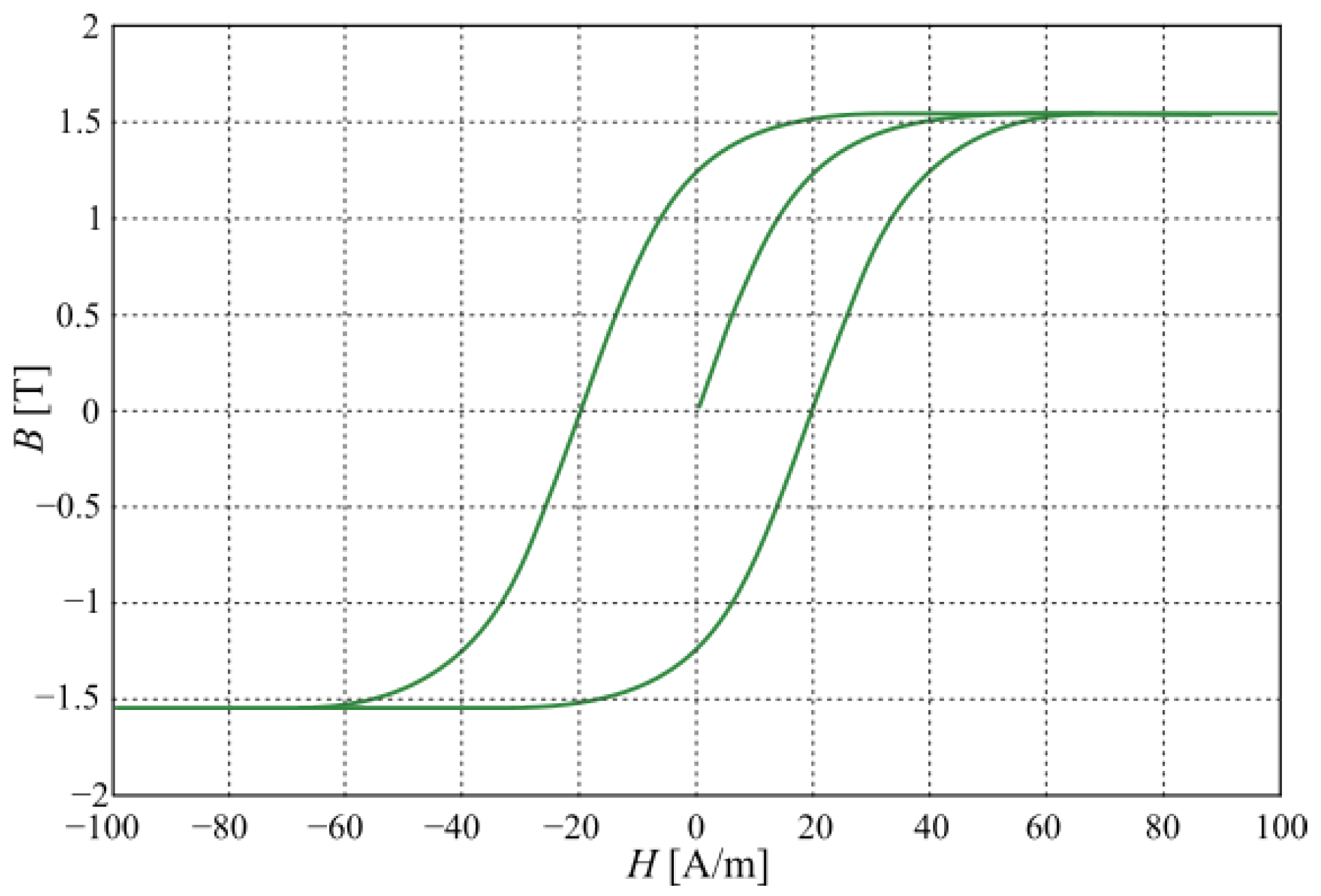

- —Magnetic flux density in the core as a function of the magnetic field strength [];

- —Instantaneous magnetic field strength in the core [];

- N—Number of turns of the primary winding [–];

- —Mean length of the magnetic path in the core [].

- —Differential (local) inductance of the magnetizing circuit, dependent on the operating point on the B–H curve [H];

- N—Number of turns of the winding [–];

- A—Cross-sectional area of the core through which the flux passes [m2];

- —Mean length of the magnetic path in the core [m];

- B—Magnetic flux density in the core material [T];

- H—Magnetic field strength in the core material [A/m];

- —Differential permeability (local slope of the magnetization curve), equivalent to [H/m].

- —Saturation flux density of the core material [];

- —Time instant at which the core reaches the saturation state [].

- —Magnetic field strength at which the core enters saturation [];

- —Differential inductance in the linear region of the magnetization curve (before saturation) [];

- —Differential inductance in the saturation region of the core (after reaching ) [].

4.3. Model of the Resistive State of the Windings

- —Time instant at which the superconducting layer transitions from the superconducting to the resistive state [].

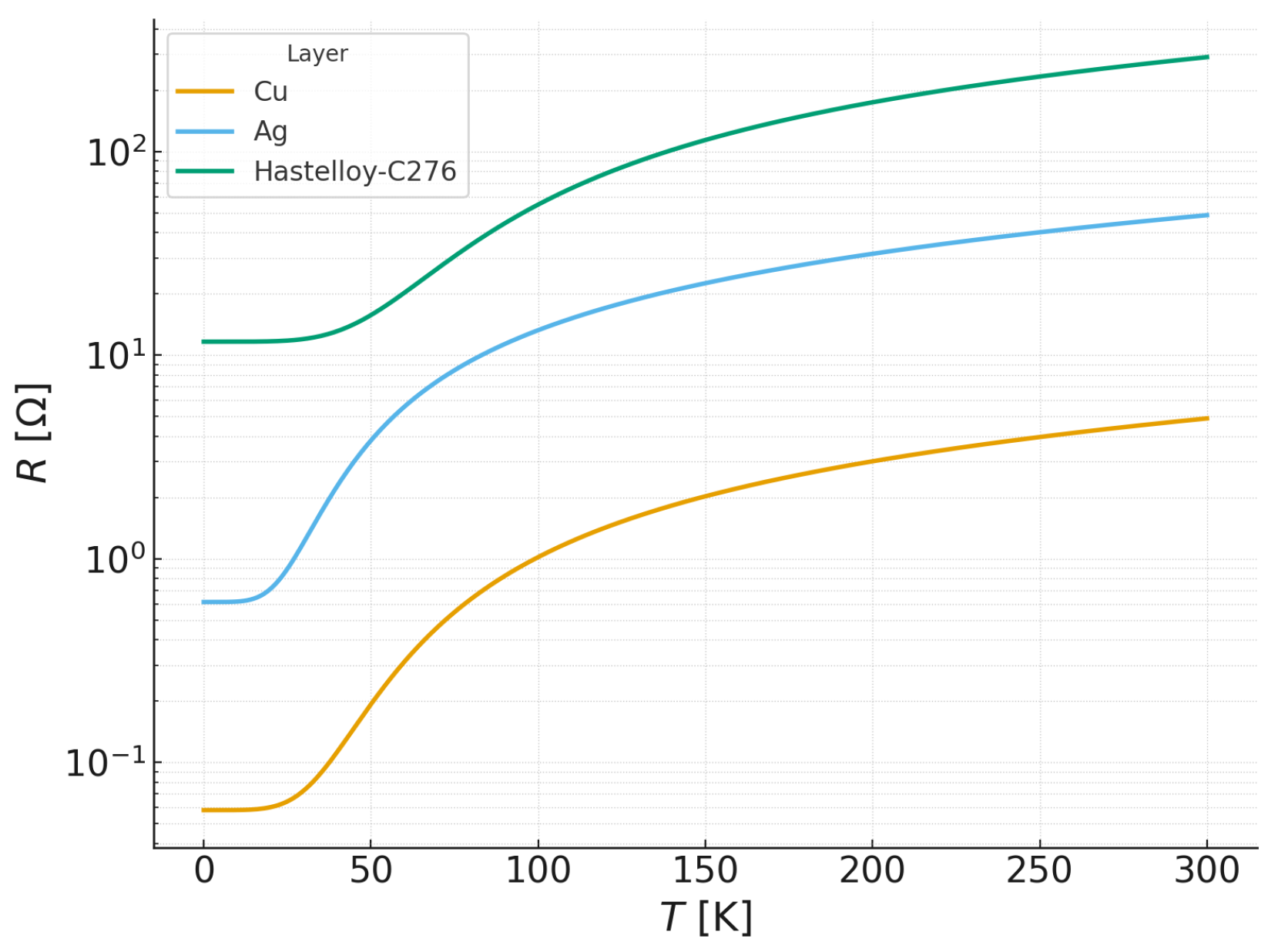

- —Resistance of the upper metallic layer (), dependent on the temperature [];

- —Resistance of the lower metallic layer (), dependent on the temperature [];

- —Average values of the temperature fields and along the y-coordinate at time t; the functions () are determined from the heat conduction model (Section 4.4).

- —Time instant at which the superconducting layer transitions from the superconducting to the resistive state [];

- —Critical current of the superconductor at temperature at time [];

- —Initial current in the upper metallic layer after entering the resistive state [];

- —Initial current in the lower metallic layer after entering the resistive state [];

- —Electrical resistances of the upper () and lower () metallic layers at the liquid nitrogen bath temperature [];

- —Liquid nitrogen bath temperature [].

4.4. Heat Conduction Model

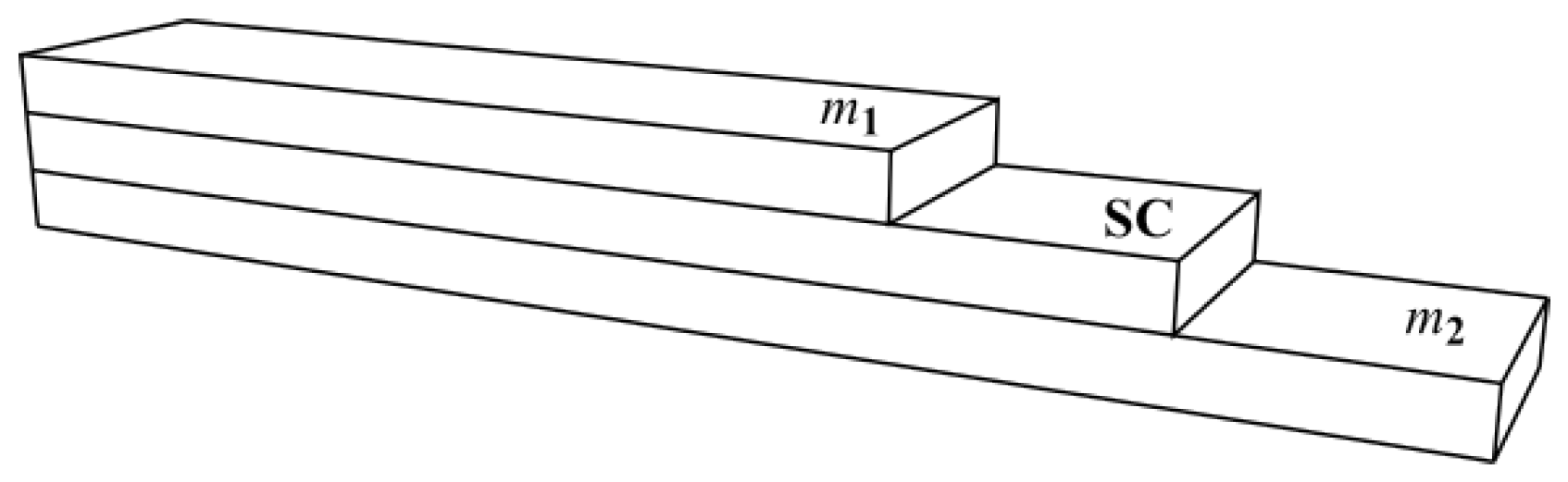

- Upper metallic layer , :

- Superconducting layer SC, :

- Lower metallic layer , :

- y—Coordinate along the thickness axis of the HTS tape [];

- d—Total thickness of the composite tape [];

- —Thickness of the upper metallic layer [];

- —Thickness of the superconducting (SC) layer [];

- —Temperature distribution in the upper metallic layer [];

- —Temperature distribution in the superconducting (SC) layer [];

- —Temperature distribution in the lower metallic layer [];

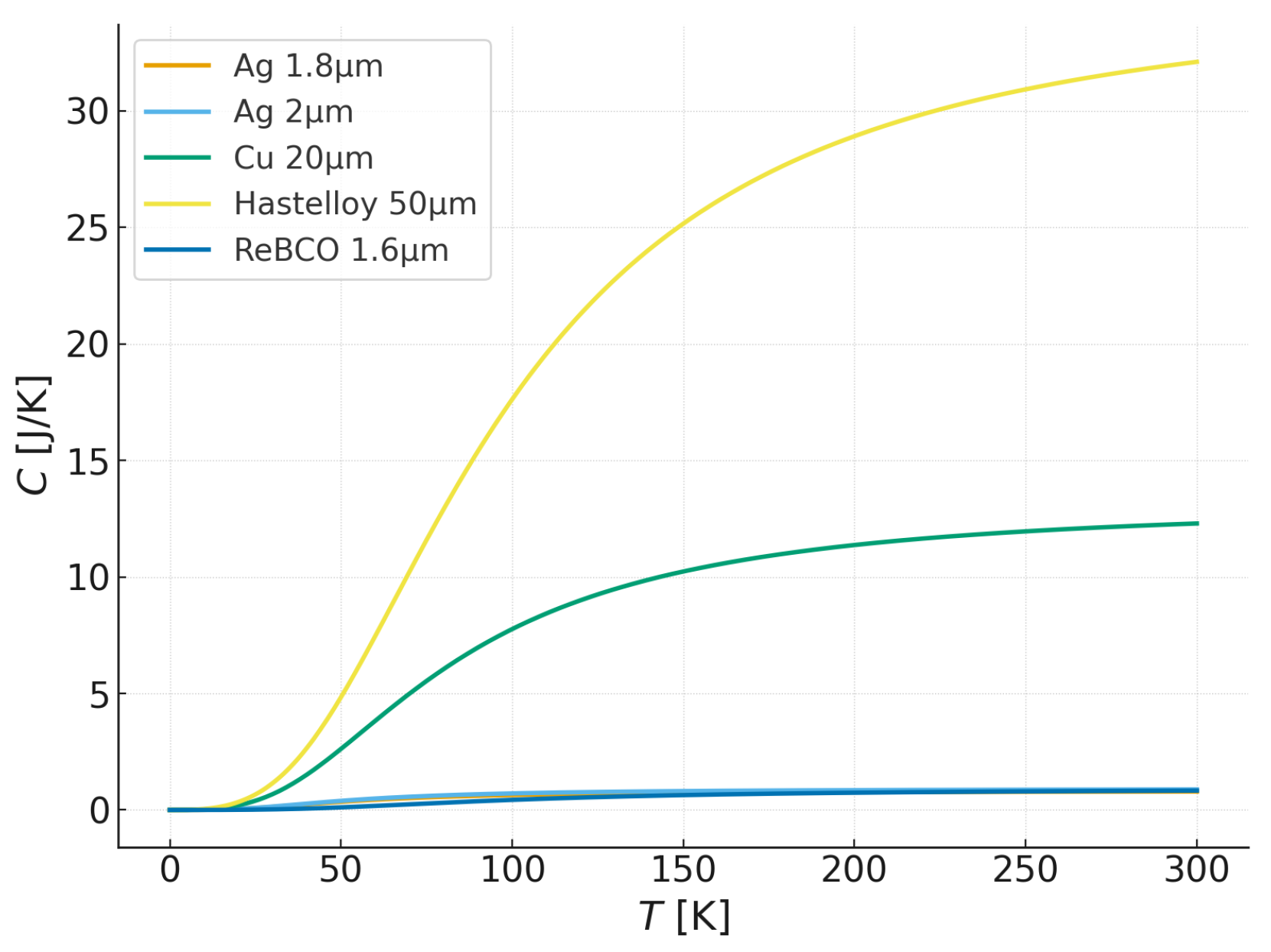

- —Densities of layers , SC, and , respectively, [];

- —Temperature-dependent specific heats of the respective layers [];

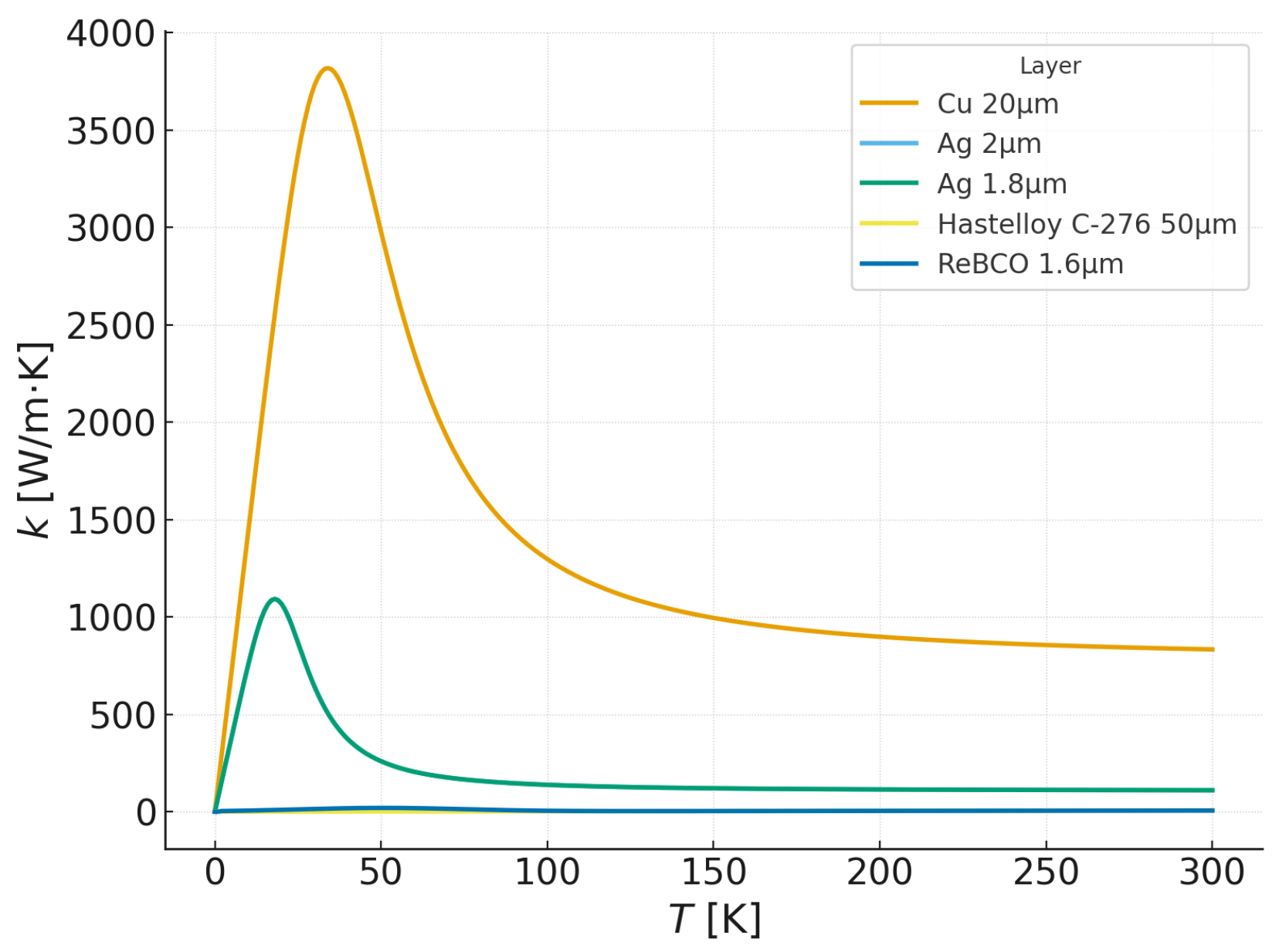

- —Temperature-dependent thermal conductivities of the respective layers [];

- —Volumetric Joule heat generation in metallic layers and [], produced by current flow after the loss of superconductivity,

- t—time [];

- —Liquid nitrogen bath temperature [].

- —Electrical resistivity of the metallic layer (), temperature-dependent [];

- —Effective cross-sectional area of the metallic layer [m2];

- —Volumetric power density of Joule losses in the metallic layer [W/m3].

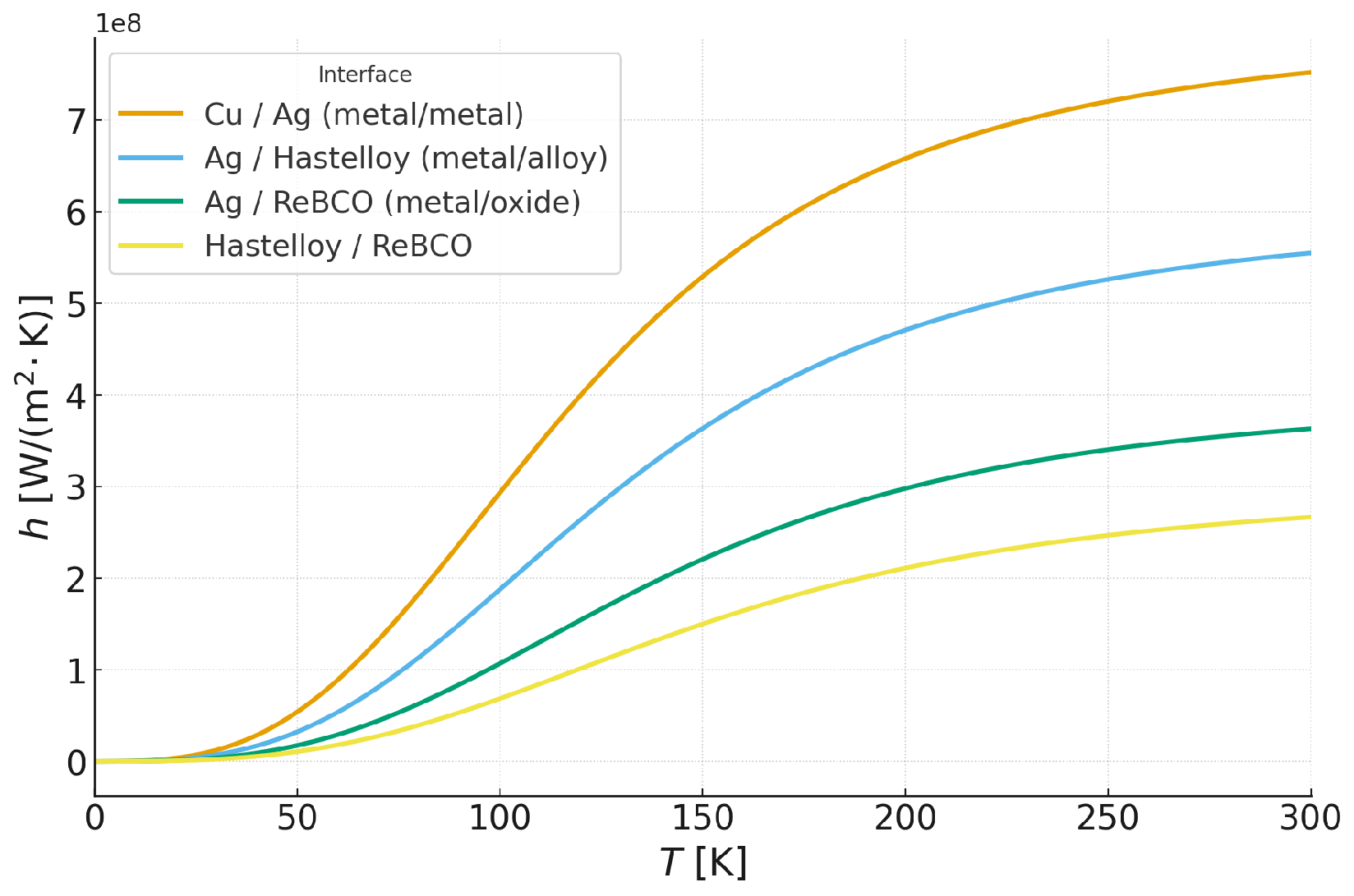

- At the –SC interface, for :

- At the SC– interface, for :

- At the –SC interface, for :

- At the SC– interface, for :

- —temperature gradients along the y-axis in the respective layers [].

- Upper surface of the layer ():

- Lower surface of the layer ():

4.5. Recovery of the Windings to the Superconducting State

- —Critical temperature of the superconductor [];

- —Critical current of the superconductor, dependent on the maximum temperature of the SC layer [].

5. Numerical Implementation

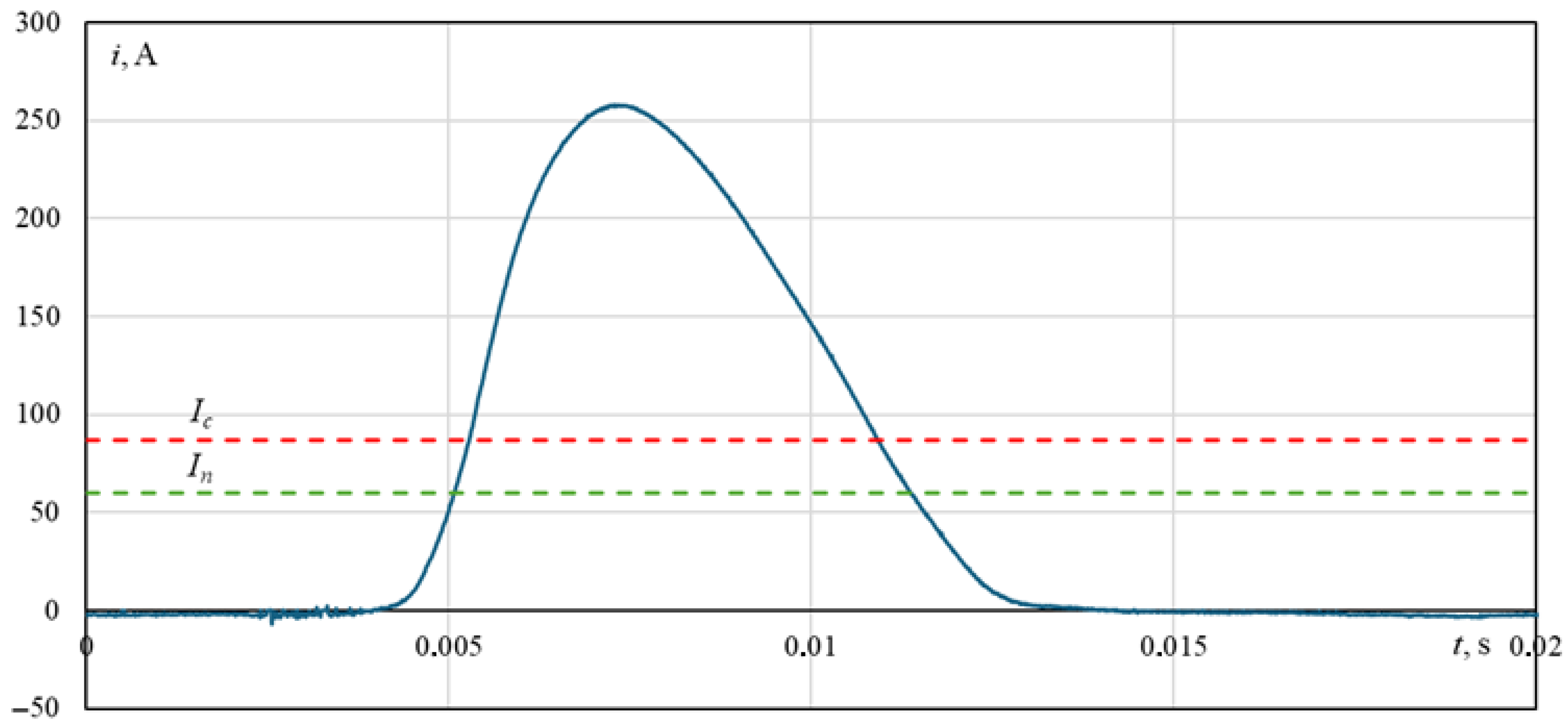

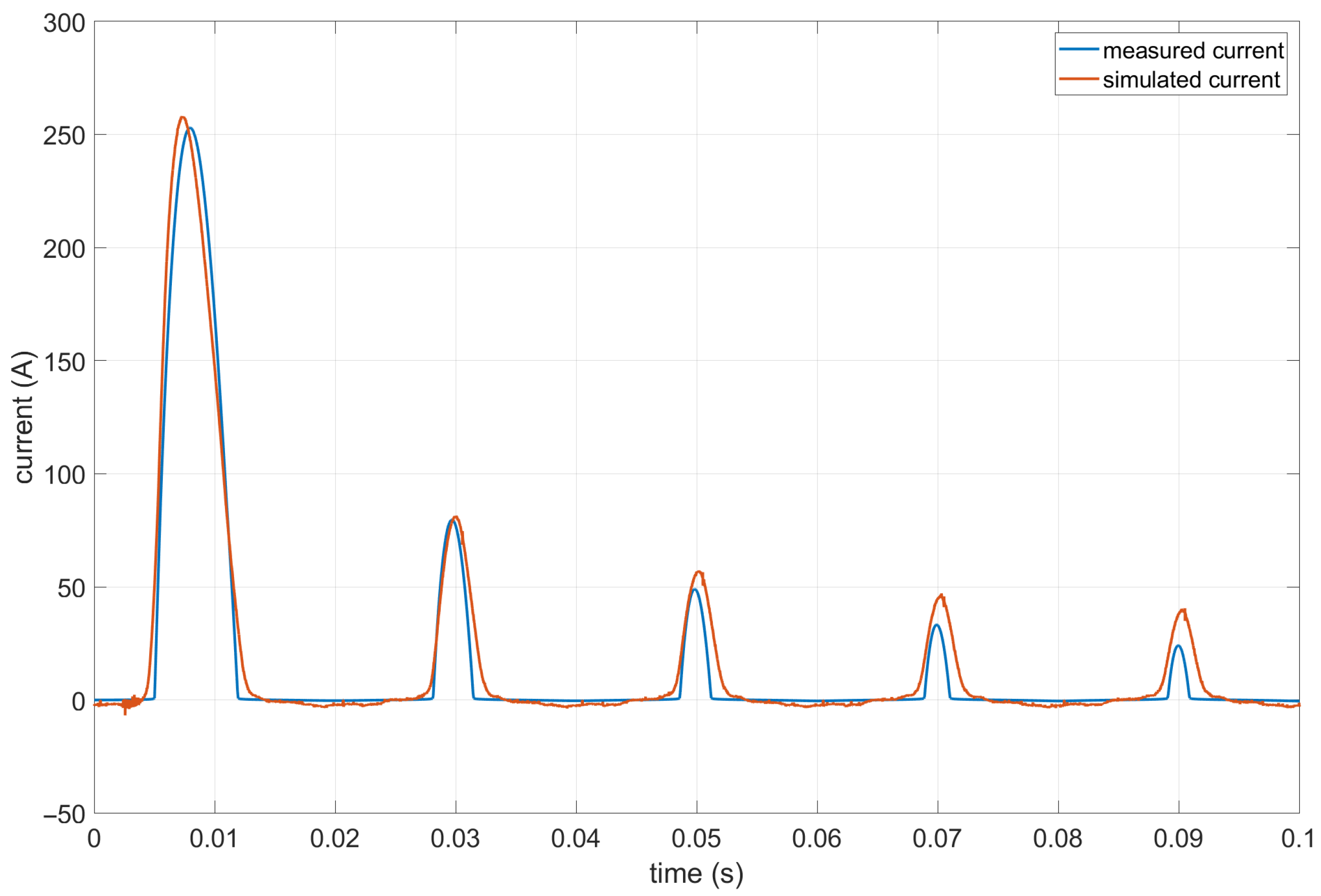

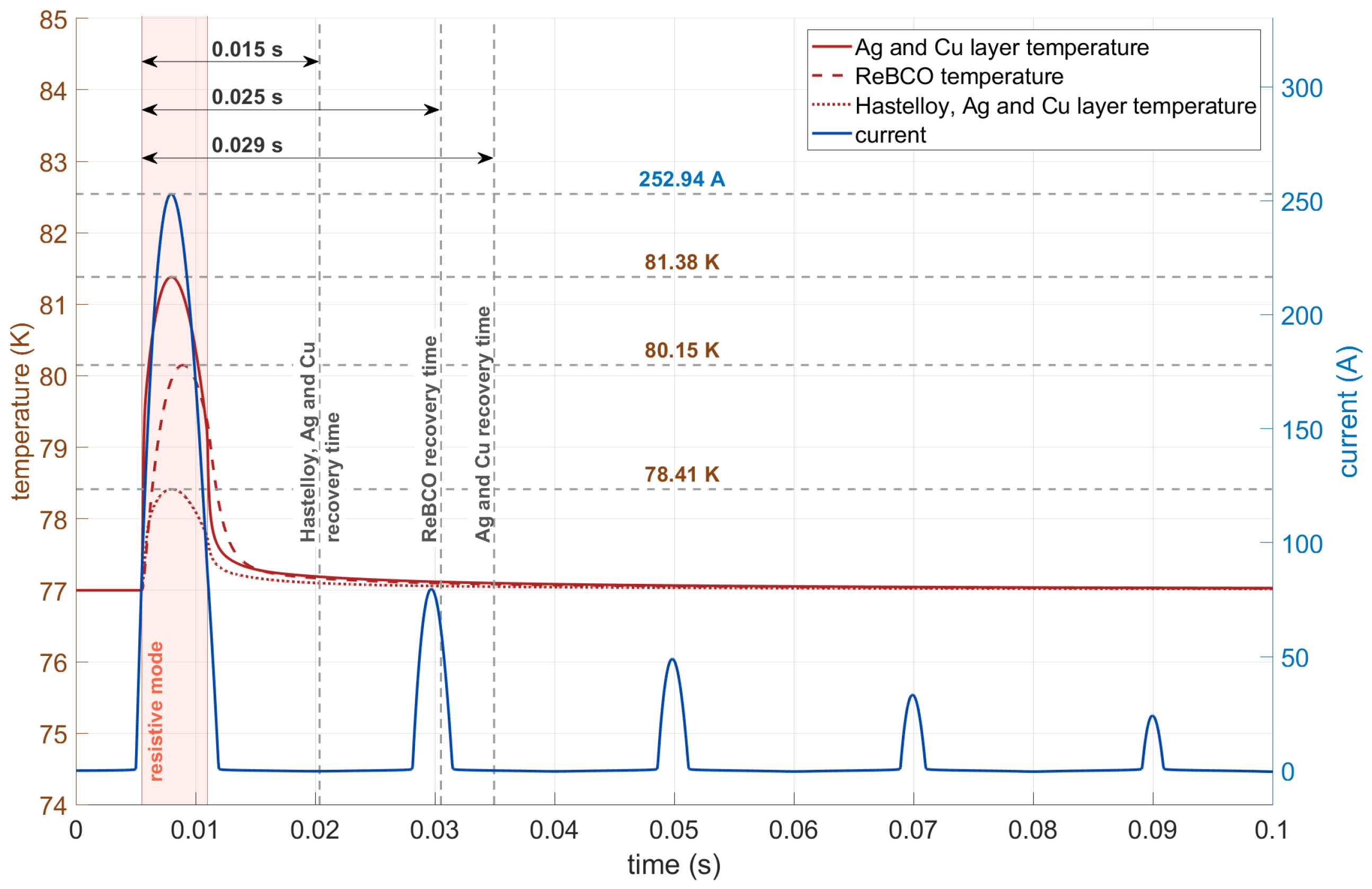

6. Simulation Results

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- Development and validation of a numerical model of the HTS transformer;

- Demonstration of close agreement between simulation results and experimental measurements for the initial inrush current pulses;

- Identification of thermal mechanisms within the HTS tape structure and their influence on winding stability;

- Indication of the highest operational risk associated with the first inrush current pulse;

- Proposal of employing nanomaterials with high thermal conductivity as a solution to enhance cooling efficiency and thermal stability of HTS transformers.

9. Future Prospects of Graphene and CNT Coatings in HTS Transformer Design

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sankhwar, P. Implementation of Superconducting Technology in Power System for Reduction of Transmission and Distribution Line Losses: Review. SSRN Electron. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tabarés, L.; Martínez-Luaces, V.E.; Alegría, F.; Morandi, A.; Pardo, E.; Solovyov, M.; Sánchez, A. Perspectives in Power Applications of Low and Mainly High Temperature Superconductors: Energy, Transport and Industry. Riv. Nuovo Cimento 2025, 48, 71–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, C.; Ma, Y. Superconducting Materials: Challenges and Opportunities for Large-Scale Applications. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2106.02825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manusov, V.; Kharitonov, V.; Kozlov, A.; Belov, A.; Akhmedov, A.; Konovalov, A. The Application of Transformers with High-Temperature Superconducting Windings Considering the Skin Effect in Mobile Power Supply Systems. Mathematics 2025, 13, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, A.B.; Li, X.-F.; Majoros, M.; Sumption, M.D.; Selvamanickam, V. AC Loss Reduction in Multifilamentary Coated Conductors with Transposed Filaments. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017, 27, 5600105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, A.; LeClair, A.; Hartwig, J.; Ghiaasiaan, S.M. Two-Dimensional Network Flow Modeling of No-Vent Tank Filling of a Cryogenic Tank with Thermodynamic Vent System Assisted Injector. Cryogenics 2025, 146, 104004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiri, G.; Berger, K.; Trillaud, F.; Lévêque, J. Electromagnetic-Thermal Finite Element Model Coupled to Reduced Electrical Circuit for Simulating Inductive HTS Coils in Overcurrent Regimes. Cryogenics 2025, 148, 104068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Alipour Bonab, S.; Song, W.; Yazdani Asrami, M. Short Circuit Analysis of a Fault-Tolerant Current-Limiting High Temperature Superconducting Transformer in a Power System in Presence of Distributed Generations. Superconductivity 2024, 9, 100085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nițu, M.-C.; Nicolae, I.-D.; Dina, L.-A.; Mircea, P.-M. Power Transformer Inrush Current Analysis: Simulation, Measurement and Effects. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da S. Fonseca, W.; de S. Lima, D.; Lima, A.K.F.; Soeiro, N.S.; Nunes, M.V.A. Analysis of Electromagnetic-Mechanical Stresses on the Winding of a Transformer under Inrush Currents Conditions. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2016, 50, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrinho, A.M.; Camacho, J.R.; Malagoli, J.A.; Mamede, A.C.F. Analysis of the Maximum Inrush Current in the Optimal Design of a Single-Phase Transformer. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 4706–4714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahamed, M.; Seyyedbarzegar, S. Temperature Reduction of an HTS Transformer under Short Circuit Fault by Modifying the Cryostat Structure: Impact of Perlator and Valve Location. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2024, 618, 1354429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Luo, X.; Chang, S.; Guan, X. A Novel Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Hybrid Energy Ship Power System Based on the Improved NSGA-II Algorithm. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 232, 110385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, E.; Dadhich, A. Electro–thermal Modelling by Novel Variational Methods for Superconductors. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.01673. [Google Scholar]

- Grilli, F.; Pardo, E.; Stenvall, A.; Nguyen, D.N.; Yuan, W.; Gomory, F. Computation of Losses in HTS under the Action of Varying Magnetic Fields and Currents. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 24, 8200433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tsuchiya, K.; Fujita, S.; Muto, S.; Iijima, Y. Experiment and Numerical Simulation on Quench Characteristics of ReBCO Impregnated Coil. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsotsopoulou, E.; Dyśko, A.; Hong, Q.; Elwakeel, A.; Elshiekh, M.; Yuan, W.; Booth, C.; Tzelepis, D. Modelling and Fault Current Characterization of Superconducting Cable with High Temperature Superconducting Windings and Copper Stabilizer Layer. Energies 2020, 13, 6646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manusov, V.Z.; Ivanov, D.M.; Ivanova, E.V. Modeling and Experimental Study of the Inrush Current of a High-Temperature Superconducting Transformer. Probl. Energeticii Reg. 2024, 2, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 10107:2005; Grain-Oriented Electrical Steel Sheet and Strip Delivered in the Fully Processed State. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Belgium, Brussels, 2005.

- SuperPower Inc. SuperPower® 2G HTS Wire Specifications. Available online: https://www.superpower-inc.com/specification.aspx (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Taghikhani, M.A.; Taghikhani, Z. A Novel and Accurate Analytical–Numerical Method for Inrush Current Modeling of Three-Limb Power Transformers. COMPEL—Int. J. Comput. Math. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2020, 39, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarzyniec, G. Calculating the Inrush Current of Superconducting Transformers. Energies 2021, 14, 6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, B.C.; Kim, S. Accurate Transformer Inrush Current Analysis by Controlling Closing Instant and Residual Flux. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 223, 109638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Pan, J.; Guzzomi, A. Modeling the Hysteresis Characteristics of Transformer Core under Various Excitation Level via On-Line Measurements. Electronics 2018, 7, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal, T.; Bussier, L.; Gómez, S.; Espínola, V.; Briolat, L.; Vézé, D. Determination of the Saturation Curve of Power Transformers by Processing Transient Measurements. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 195, 107153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarzyniec, G.; Boiko, O. Effect of HTS Tape Resistive Layers Cross-Sectional Area on the Inrush Current Waveform of a 13.8 kVA Transformer. Cryogenics 2025, 150, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, M.A.; Lie, T.T.; Prasad, K. Computation of the Thermal Effects of Short Circuit Currents on HTS Transformer Windings. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012, 22, 5501211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Zhang, C.; Xie, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, Y. Analysis of the Electromechanical Characteristics of Power Transformer under Different Residual Fluxes. Energies 2021, 14, 8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.F.; Childs, G.E.; Wallace, G.H. Electrical Resistivity of Some Engineering Alloys at Low Temperatures. Cryogenics 1970, 10, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Choi, E.S.; Zhou, H.D. Physical Properties of Hastelloy C-276 at Cryogenic Temperatures. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 103, 064908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matula, R.A. Electrical Resistivity of Copper, Gold, Palladium, and Silver. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1979, 8, 1147–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poker, D.B.; Klabunde, C.E. Temperature Dependence of Electrical Resistivity of Vanadium, Platinum and Copper. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 26, 7012–7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Choi, E.S.; Zhou, H.D. Low Temperature Physical Properties of a Ni–Mo–Cr Alloy (MP35N): Comparison to Hastelloy C-276. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 101, 123710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R.; Fickett, F.R. Low-Temperature Properties of Silver. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 1995, 100, 119–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaviv, R.; Westrum, E.F., Jr.; Brown, R.J.C.; Sayer, M.; Yu, X.; Weir, R.D. The Heat Capacity and Derived Thermophysical Properties of the High TC Superconductor YBa2Cu3O7−δ from 5.3 to 350 K. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 6794–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthil, P. Material Properties at Low Temperature. In CAS–CERN Accelerator School: Superconductivity for Accelerators; Bailey, R., Ed.; CERN Yellow Report CERN-2014-005; CERN: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 77–95. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1501.07100 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Stępień, Ł.; Łagodowski, Z.A. A Stochastic Model of Anomalously Fast Transport of Heat Energy in Crystalline Bodies. Energies 2023, 16, 7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowski, T.; Stępień, Ł. Long Time, Large Scale Limit of the Wigner Transform for a System of Linear Oscillators in One Dimension. J. Stat. Phys. 2012, 148, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lepri, S.; Livi, R.; Politi, A. Thermal Conduction in Classical Low-Dimensional Lattices. Phys. Rep. 2003, 377, 1–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepri, S.; Livi, R.; Politi, A. Universality of Anomalous One-Dimensional Heat Conductivity. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 68, 067102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benenti, G.; Lepri, S.; Livi, R. Anomalous Heat Transport in Classical Many-Body Systems: Overview and Perspectives. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimoradi, H.; Shams, M.; Ashgriz, N. Enhancement in the Pool Boiling Heat Transfer of Copper Surface by Applying Electrophoretic Deposited Graphene Oxide Coatings. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 159, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kumari, P.; Rahul, N.; Sen, D.; Mandal, S.K. Experimental Comparison of Pool Boiling Characteristics between CNT, GO, and CNT+GO-Coated Copper Substrate. Heat Transfer 2024, 53, 2809–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimpour Ahmadi, V.; Guler, T.; Amin, S.; Apak, A.M.; Apak, A.; Parlak, M.; Tastan, U.; Kaya, I.I.; Sadaghiani, A.; Koşar, A. Effect of Graphene Coating on Flow Boiling in a Minichannel at Sub-Atmospheric Pressures. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 229, 125762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salari, S.; Abedini, E.; Sabbaghi, S.; Adibi, P. Pool Boiling Heat Transfer Behavior of Graphene Oxide Coating on Copper Substrate Utilizing Spin Coating Method. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 6611–6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Rated power | |

| HV/LV voltage | 230 /60 |

| Rated frequency | 50 |

| HV/LV current | 60 /230 |

| Maximum magnetic flux density | |

| No-load current | |

| Short-circuit voltage | 3.2% |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Supply voltage E | 230 |

| Supply frequency f | 50 |

| Autotransformer resistance | |

| Autotransformer reactance | |

| Supply line resistance | |

| Supply line reactance | 0 |

| Winding resistances | |

| Leakage reactances | |

| Core loss resistance | |

| Magnetizing reactance |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komarzyniec, G.; Stępień, Ł.; Łagodowski, Z. Coupled Electromagnetic–Thermal Modeling of HTS Transformer Inrush Current: Experimental Validation and Thermal Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225993

Komarzyniec G, Stępień Ł, Łagodowski Z. Coupled Electromagnetic–Thermal Modeling of HTS Transformer Inrush Current: Experimental Validation and Thermal Analysis. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225993

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomarzyniec, Grzegorz, Łukasz Stępień, and Zbigniew Łagodowski. 2025. "Coupled Electromagnetic–Thermal Modeling of HTS Transformer Inrush Current: Experimental Validation and Thermal Analysis" Energies 18, no. 22: 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225993

APA StyleKomarzyniec, G., Stępień, Ł., & Łagodowski, Z. (2025). Coupled Electromagnetic–Thermal Modeling of HTS Transformer Inrush Current: Experimental Validation and Thermal Analysis. Energies, 18(22), 5993. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225993