Abstract

By 2050, global population growth will lead to a significant increase in demand for animal-based products, including seafood. Aquaculture is a key solution to meet these needs while reducing pressure on wild aquatic stocks. However, its environmental footprint and energy demand remain open concerns. This study explores the co-location of offshore aquaculture with a wave energy converter—WaveRoller—as a renewable power source. Using a 44-year dataset from the Portuguese coast near Peniche, the analysis evaluates the survivability and operation of the WaveRoller, long-term percentile trends, seasonal energy production, extrapolated extreme events using probabilistic modeling, and confidence intervals for energy costs. A scenario-based range of energy demand is constructed from a baseline blue mussel production of over 400 tons/yr. The K-Means clustering method is applied to reduce data size while maintaining its representativeness. Results show that a 600 kW WaveRoller is similarly suited to operational wave conditions compared to a 1000 kW device, though it excels when aquaculture energy demand peaks in Summertime. The probability that a single WaveRoller fails to meet annual aquaculture energy needs is nearly zero, though, during Summer, it can become statistically significant. The opposite is verified on survivability during Winter, under harsher wave conditions. The Levelized Cost of Energy is calculated for different expenditure scenarios, with minimum values slightly under 200 EUR/MWh being reported only under ideal conditions. Future work should include climate change scenarios and life cycle assessments to better evaluate environmental impacts and techno-economic viability.

1. Introduction

By 2050, the global population is expected to reach 9.2 billion, increasing the demand for animal-based products by 95% compared to 2010 [1]. However, commercial marine populations have been declining, particularly due to climate change (CC) and overfishing [2,3]. Aquaculture has, therefore, emerged as an alternative to meet food requirements while avoiding overexploitation of wild aquatic ecosystems. It is estimated that global aquatic animal production could reach 205 million tons by 2032, of which 111 million would come from aquaculture [4]. Nevertheless, aquaculture can be controversial due to issues such as inadequate wastewater treatment, which leads to environmental pollution [5,6]. On the other hand, integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) and certain cultivated species, such as algae and bivalves, can mitigate eutrophication and restore habitats for various marine species [7]. To limit negative impacts, European legislation imposes strict standards, particularly concerning the use of antibiotics, waste discharge, and farming density [8,9,10]. In the context of increasing seafood demand and the need to develop sustainable practices, offshore aquaculture in Europe appears as a promising solution. It also helps avoid the saturation of coastal and onshore areas already heavily used for other activities [5,11]. Nonetheless, to enhance animal welfare and reduce environmental impacts, it is necessary to select species adapted to the aquaculture site. Many factors influence species viability, including temperature, salinity, and chlorophyll content [12,13]. Selecting species acclimated to the aquaculture location would amplify their viability. Offshore infrastructures, though, face additional technical, environmental, and economic challenges. They also require energy to operate [12], making it relevant to explore renewable energy sources.

Global electricity demand was estimated at around 31,153 TWh in 2024, a 4.3% increase compared to 2023 [14], and is expected to continue growing with population growth and the arrival of energy-intensive technologies like Artificial Intelligence. It becomes essential to consider energy input from renewable sources [15], and developing co-located offshore aquaculture and marine renewable energy could limit CC impacts on these sectors [15]. Oceans and seas represent a significant renewable energy resource due to thermal and salinity gradients, currents, tides, and waves, which could theoretically provide over 90,000 TWh/yr (thermal and salinity gradients), along with an additional 26,000 TWh/yr (tides/currents) and 29,500 TWh/yr (waves) [16,17]. Wave Energy Converters (WECs) are not yet fully technologically mature [18,19,20], but companies such as Oscilla Power (Triton), CorPower Ocean (C4), Wave Dragon ApS (WaveDragon), and AW-Energy (WaveRoller) have reached a high Technology Readiness Level. These WECs can typically be located at intermediate depths where a relevant wave energy resource is present that can coincide with aquaculture zones (e.g., the coasts of Penghu, Puerto Rico, or Peniche [12,21,22]).

The energy produced by WECs could power aquaculture farms, but it should be verified whether it is sufficient to meet aquaculture needs throughout the seasons. CC and local variability could also affect WEC performance, making it relevant to study the long-term evolution at the deployment site [23]. WECs also face technical challenges, as they must withstand storms. Hence the need to analyze extreme waves [24] and compare them with the converter’s design tolerances, as recommended by international standards [25,26]. Additionally, studying the distribution of wave heights and frequencies is important to schedule maintenance activities [27]. Given the economic challenges faced by WECs, one must also estimate their Levelized Cost of Energy (LCoE) [28]. Considering the uncertainties of both expenditures and energy output, the introduction of scenarios and probabilistic modeling (e.g., confidence intervals) provides better insights toward decision-making processes than deterministic approaches, as seen in other fields of research—from coastal protection to offshore wind [29,30]. Recently, Bru et al. [31] also employed probabilistic modeling to LCoE estimates of solar photovoltaic for the North Sea. A stochastic definition of the LCoE terms was employed alongside Monte Carlo simulations, detailing their variability, sensitivity, and contributions toward the final energy costs. As such, there is a risk that the wave energy sector can lag behind this mindset change, making it less competitive and reliable. Finally, to reduce dataset size for simulations—particularly for farm optimization with wave propagation models (WPMs)—, clustering algorithms can be used, with the resulting data being checked for statistically significant differences [32,33].

In existing wave energy literature, deterministic approaches are still prevalent, while statistical/probabilistic techniques are somewhat fragmented across distinct studies. Works on co-located wave energy and offshore aquaculture are gaining traction [12,34,35] but remain limited. Hence, conjugating the aforementioned techniques and exploring synergetic opportunities between the two sectors can provide frameworks for other researchers to systematically replicate in their studies. Though guidelines for WEC development, such as those provided by DNV and Ocean Energy Systems, exist [26,36], they assume a somewhat generic profile, which can be consolidated by implementing the techniques applied in this paper.

In detail, this paper applies advanced statistical and probabilistic techniques to a case study of a co-located Mytilus edulis aquaculture facility with an AW-Energy WaveRoller device off the coast of Peniche, Portugal. This coastal nation has an intensive wave energy resource [37] and is one of the largest consumers of seafood—including bivalves—averaging 60 kg/yr per capita [38]. This makes offshore aquaculture powered by WECs particularly interesting for the country, as it could meet local needs while mitigating emissions. This work also extends beyond the limited number of local case studies found in the literature [39], as well as those that address co-located offshore aquaculture with wave energy in Portugal. Uncertainty-based estimates of energy supply, demand, and costs are provided in detriment of more rigid deterministic ones, while co-location opportunities and limitations for the Peniche site are also discussed. Being a realistic case study area, it yields a dual contribution toward the development of these strategic “Blue Economy” markets, which can assist decision-making processes by involved stakeholders. Furthermore, the proposed approach not only leverages dispersed yet consolidated techniques that incorporate uncertainty—a matter of increasing importance in modern industries, but lacking in the wave energy sector—but also employs recent/novel methods, such as K-Means and confidence intervals (CI), respectively. As a result, an innovative approach is implemented based on a combination of probabilistic and statistical methods, and its potential is demonstrated for an equally promising case study: co-location of offshore aquaculture with wave energy.

The aims of this paper are to (i) compare the energy output of a WEC with aquaculture energy requirements for the Peniche case study, where both sectors operate; (ii) analyze the local wave climate to estimate survivability, operation, and long-term trends, based on robust statistical and probabilistic techniques; (iii) propose a dataset reduction approach to facilitate follow-up WPM studies while maintaining representativeness; and (iv) estimate the LCoE of energy produced under various capital (CapEX) and operational (OpEX) expenditure scenarios while accounting for uncertainty.

The paper is structured as follows:

- Section 2 describes the methodologies applied to the case study, the marine species considered, and the aquaculture energy demand scenarios.

- Section 3 presents the results obtained, including the survivability assessment, dataset reduction, energy production estimation, comparison with energy needs, and economic evaluation.

- Section 4 concludes the study, summarizes the main outcomes, and proposes future study paths.

This study not only provides insightful outcomes for co-located offshore aquaculture with wave energy, particularly for the involved stakeholders at the Peniche site, but also provides an in-depth probabilistic analysis to be reproduced by other researchers. Though the work finds that achieving competitive LCoE for the Peniche site can be difficult, it also demonstrates the need for further verifying clustering techniques upon the selection of representative sea-states. It also showcases the sensitivity to “worst-case scenarios”, such as the Summer (peak demand, low energy production). Furthermore, it highlights the importance of long-term trends, which can affect the productivity of a WEC; in this study, the lower percentiles of significant wave height and wave energy period exhibit an increasing trend, which can lead to an enhancement of the energy yield of the WaveRoller.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Case Study

In this paper, the maritime area around the city of Peniche, located in Western Portugal (Figure 1), was studied. This site was ideal for the study, as it hosts a Mytilus edulis aquaculture facility [40] south of Peniche, and the ONDEP project north of the city [41] (Figure 2). AW-Energy aims to install a 2 MW wave energy farm with four WaveRoller converters, and a first 350 kW prototype was successfully tested on this site in 2019 during the FOAK project [42] (Figure 3). This extends from Portugal’s investments in marine renewables, with an expected installed capacity of 2 GW by 2030, according to the Allocation Plan for Offshore Renewable Energy, or PAER [43].

Figure 1.

Map of Portugal showing the location of Peniche, followed by a map of Peniche showing the aquaculture site (red, south) and the FOAK project site (yellow, northeast).

Figure 2.

Mytilus edulis [44].

Figure 3.

WaveRoller wave energy farm installation in Peniche, Portugal (2019) [45].

In order to analyze the wave data for the site where the farm is located, a study point was established at longitude 9.3081° W, latitude 39.3896° N, and bathymetry 15.23 m based on the coordinates delimiting the space occupied by the WaveRoller during the FOAK project [46]. This point provides information on the incident wave before the data is significantly altered by bathymetry while remaining close enough to the WEC to have limited propagation. Using these coordinates and a pre-validated high-resolution SWAN numerical model [37], 44 years of data were obtained and analyzed for this study.

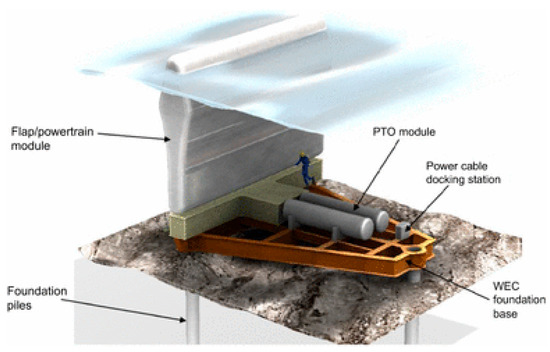

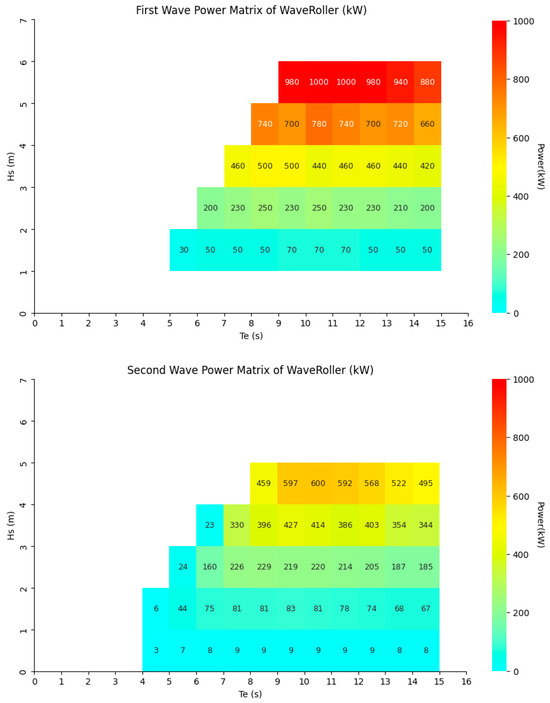

Furthermore, one of the main objectives of this paper is to determine whether the energy output can meet the needs of offshore aquaculture (see first aim in the Section 1). To do this, it is necessary to know the power matrix of the WaveRoller. It uses an articulated panel, anchored to the seabed, which is moved by the movement of the waves. The power rating ranges from 350 kW to 1000 kW [47], thus justifying the selection of (two) distinct power matrices (Figure 4). Both correspond, originally, to a 1000 kW WaveRoller [48], but the second matrix [49,50] was downscaled to 600 kW to correspond to the FOAK project.

Figure 4.

Representation of the two matrices with a colorimetric index ranging from 0 to 1000 kW, with the significant wave height Hs (m) as a function of the wave energy period Te (s) and peak wave period Tp (s).

For the downscaling, Froude similarity was used, following the methodology proposed in [19,50]:

where is the Froude number as a function of gravity , flow velocity , and characteristic length .

Then, the second matrix was adjusted to an axis identical to the original one by linearly interpolating the values (2) and adding a correction factor to avoid loss of information:

To validate this transformation, the overall and relative bias and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) were calculated. However, since it is expected to observe some error given that the objective is to reduce the power levels, the normalized values of the two matrices were also compared to verify the fidelity of the 600 kW model compared to the 1000 kW model. For this purpose, the power values of both matrices were scaled to a dimensionless scale (3).

where is the normalized value, is the power, and is the maximum reference power.

2.2. Aquaculture: Species Selection and Energy Requirements

The selected species was Mytilus edulis, with an ideal temperature range between 11 °C and 18 °C. This tends to correspond to the temperature of the site, which generally fluctuates between 13 °C and 18 °C. Furthermore, this is also an area with a sufficient silicate concentration for this species (0.5–0.9 μmol/L), since the marine area studied near Peniche has a rate of 0.72 μmol/L. However, the chlorophyll-a concentration is quite low (0.36 μg/L) compared to the needs of mussels (6.3–10 μg/L) [13]. This is clarified in Section 3. The energy requirements also need to be known in order to be compared with the WEC’s energy output. To ensure more generalizable results applicable to different farms, several cases with varying energy demands were analyzed. These requirements were determined based on the estimated order of magnitude of the studied farm’s consumption, as well as on a 2012 SARF study [51].

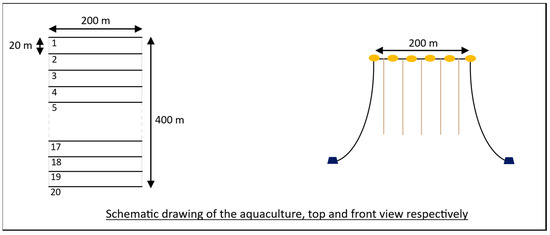

In order to obtain the magnitudes and value range, publicly available details on the Peniche aquaculture farm [52] and the literature related to the operation of mussel farms [53,54,55,56,57] were used, as well as technical documentation of commercialized products necessary for the operation of the aquaculture farm. Figure 5 shows the dimensions of the mussel farming sector studied in this paper.

Figure 5.

Representation of mussel farming in the sector studied, according to the parameters indicated by Portugal’s Directorate-General for Natural Resources, Safety and Maritime Services, or DGRM.

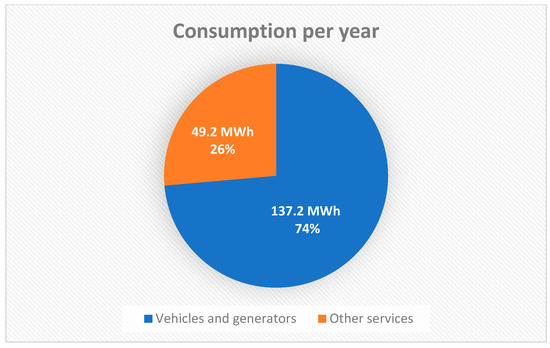

Based on this data, a reference annual consumption of 186.4 MWh for a production of 432 tons/yr of mussels was obtained. However, annual energy consumption can vary greatly depending on the level of mechanization, operation, remoteness of the site (offshore aquaculture), and type of aquaculture [58,59]. Thus, and based also on the magnitudes surveyed in the SARF report [51], a range of 100 to 500 MWh/year was chosen. Figure 6 and Table 1 show the distribution of energy expenditure calculated for the case study. Figure 6 was presented in this way to facilitate visualization and comparison with other studies, particularly the SARF study [51].

Figure 6.

Representation of the distribution of annual energy requirements for the blue mussel farming.

Table 1.

Details of estimated energy expenditure for the blue mussel farming.

To analyze seasonal differences, the various activities contributing to annual consumption were associated with the seasons according to the operational calendar. Components related to harvesting (including purification, classification, packaging, storage, washing, lighting, and part of the sea trips) were grouped together and then divided between May and July, which was considered the harvesting period [53]. Interventions requiring the winch were shared between the different seasons according to the reason for the trip. For example, 40% of the energy expenditure of these trips was exclusively distributed between Autumn and Winter (non-harvest interventions). The other items were assigned to the remaining seasons according to their frequency. Then, the seasonal shares obtained were applied to different annual consumption scenarios (100 to 500 MWh) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated energy expenditure for mussel farming for different annual requirements.

2.3. Selection of Methods for Analyzing Wave Energy Converters

2.3.1. Survivability and Operationality

Starting with survivability at sea, it is essential to have detailed information about the local wave climate. , , and wave direction , obtained from the SWAN WPM for the period between 1 January 1979 (00:00) and 31 December 2022 (22:00) were used. Each measurement was taken at bi-hourly intervals. However, data from 1 January 1979 was truncated due to the presence of potential outliers in the data attributed to the original calibration from buoy data. Given the size of the dataset, their removal has a negligible impact on non-survivability aspects.

Using a Python script (Version 3.13) and relying on the 44-year dataset, resource matrices corresponding to the expected annual average resources were generated. These indicate the number of hourly occurrences per sea-state ( − bins) and were combined with the corresponding WEC power matrices. By calculating the theoretical converted energy per sea-state, the annual energy production (AEP) can be computed.

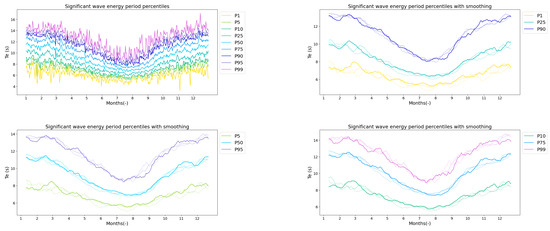

As previously mentioned, aquaculture energy needs are not constant over the year, with mussel farming showing a peak consumption during Summer harvest. Hence the need to analyze the resources available per season, especially since Portuguese waters show a seasonal trend, where Summer is generally the least favorable season for wave energy production [37]. For this purpose, another Python script was used to split the data by meteorological seasons: December–February for Winter, March–May for Spring, June–August for Summer, and September–November for Autumn.

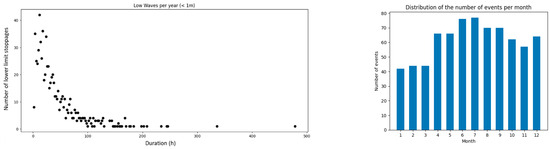

To further assess WEC survivability, extreme event exceedances that could damage the device were analyzed. The average number and duration of extreme event occurrences, which were defined as waves with heights or periods exceeding the upper matrix limits (see Figure 4), were determined. To check for seasonal patterns, a histogram of the number of events per month was plotted in Python.

Another key aspect is the occurrence of weather windows, allowing safe access to the device for maintenance operations. These were defined, in a simplified format, as periods with waves below 1.5 m for at least 120 consecutive hours [27]. A similar Python script was used to determine their duration and seasonality. Still, waves below 1.5 m may also indicate conditions too calm for the WaveRoller to produce energy (lower limits of the power matrices). Therefore, the number of events with < 1 m was also analyzed in order to obtain additional information on WEC availability.

To study WEC survivability over time, data was sampled using the Block Maxima (BM) and Peaks-Over-Threshold (PoT) methods. The extreme events were then extrapolated according to distinct return periods using a Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution and a Generalized Pareto Distribution (GPD), respectively. These are reliable probabilistic approaches often used in coastal engineering, including in wave energy conversion [24,60]. To use them, the Python libraries pyextremes and scipy.stats were employed [61]. For sampling extreme heights using PoT, a limit of 5 m was imposed, which corresponds to the minimum that could damage the WaveRoller and, as seen in Section 3, ensures GPD parameter stability. The minimum temporal interval between each peak was defined based on the analysis of extreme events (about 70 h). For sampling by BM, the maxima for each year were taken. Note that for BM, the last maximum was disregarded, given its likelihood of being an outlier ( near 2.5 m). Its removal improved the distribution fitting and provided more realistic and conservative extrapolated values.

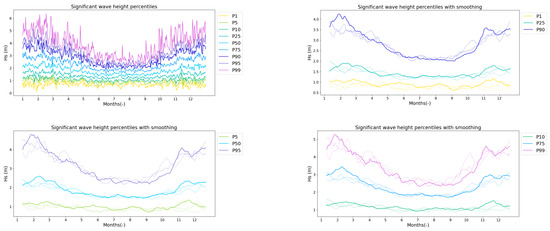

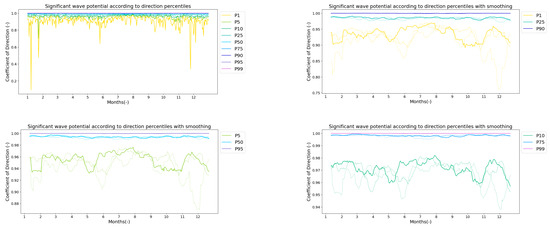

Since long-term effects, like CC, could influence the frequency and/or intensity of extreme events and the WEC’s energy production, monthly, seasonal, and annual trends in wave characteristics were investigated. Dir, and were analyzed by dividing the data into three periods: 1979–1993, 1994–2008, and 2009–2022. For each period, percentiles (P1, P5, P10, P25, P50, P75, P90, P95, P99) were compared. Graphs were smoothed using Pandas DataFrame.rolling with a 15-point window. Because Dir is circular data, it was necessary to convert it into sine and cosine components to enable percentile analysis. A directional efficiency coefficient was assigned, ranging from 1 for the optimal direction—wave front parallel to the WaveRoller—to 0—wave front perpendicular to the device (i.e., fully misaligned with the single rotational degree of freedom). The reference direction was considered to be 323° (mean Dir) or its opposite, 143°, assuming that the WaveRoller would be optimally oriented. Finally, to verify whether these characteristics changed over time, temporal trends in percentiles were analyzed using the Mann–Kendall hypothesis test to assess the presence or absence of trends on annual, monthly, and seasonal scales.

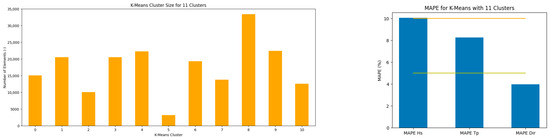

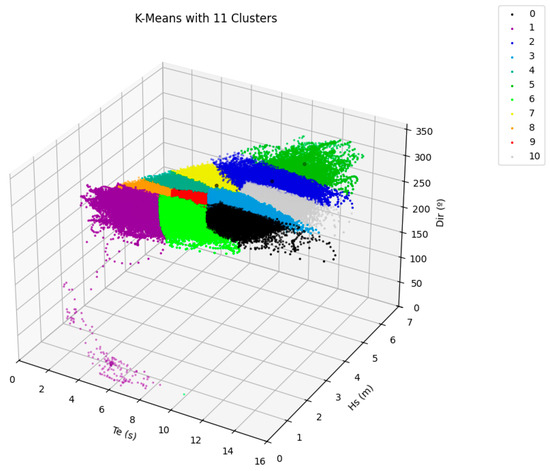

2.3.2. Dataset Reduction Approach

Another objective is to propose a reduction in the dataset which would diminish the computational effort in WPM simulations while maintaining sea-state representativeness. For this study, the data was clustered with a K-Means clustering algorithm. The goal was to find the minimum number of clusters that would yield a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) (4) under 5–10% for all three sea-state parameters [32,62]:

where n is the data size, K the number of clusters, the set of points belonging to cluster k, R the actual value, and O the cluster centroid value.

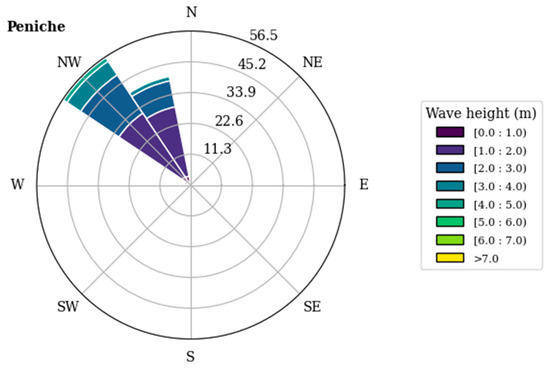

Since the K-Means clustering algorithm is not well-suited for circular data such as Dir, a similar transformation as previously described for the percentile-based analysis was used: the direction was converted into its sine and cosine components. However, unlike the percentile method, a directional efficiency coefficient was not applied here. The directional profile of the clusters was plotted on a wave rose diagram to show that the directional values are well aligned with those of the site directions. To improve the clustering performance, the data were standardized through division by the respective means of and , depending on the chosen power matrix, as well as the means of the cosine and sine of the Dir. This standardization method yielded better clustering results than other approaches tested, including standardization using the median, normalization to the [0, 1] range, and pre-processing with StandardScaler, RobustScaler, and MinMaxScaler.

The clustering algorithm was run using the K-Means tool from the Scikit-learn library, and the parameters chosen included initialization by k-means++, a variable number of clusters, and a “seed” of 0. This yielded the cluster centroids and a new dataset based on them, after reversing the standardization and reconstructing the angles from the Dir cosines and sines. In order to verify this reduction in the dataset, the estimated AEP and its confidence intervals were compared with the original data for the two power matrices. To do this, a paired Student’s t-test (5) was performed at a confidence level of 95%:

where is the average difference and the standard deviation of differences.

In addition, the AEP averages and confidence intervals were calculated using the z and t distributions, and the percentage error was analyzed. To verify that the distribution can be approximately normal, histograms, Q-Q plots, and P-P plots were created. Furthermore, to improve the results of the AEP calculation for the reduced data, values outside the limits of the power matrix studied were truncated, in line with the survivability assessment. The method proposed above was then used for clustering. Yet, even without this removal, the MAPEs remained below 10%.

2.3.3. Formulation for Energy Production and Costs Estimates

Finally, the final objective required estimating the AEP and its cost, in order to determine whether the energy needs of aquaculture are covered and the LCoE is competitive. As such, the AEPs per matrix were calculated, both for the original and K-Means reduced data. Then, for each case and based on the sample of 44 AEPs, an average AEP and its confidence interval were estimated, assuming a standard normal distribution. Additionally, the probability that a WaveRoller unit cannot meet the mussel farm’s needs was calculated, namely by computing the AEP distribution z-score and comparing it with the energy demands.

Lastly, the LCoE (6) was estimated according to different CapEX and OpEX costs.

CapEX between EUR 1.5 million/MW and EUR 5 million/MW was assumed in increments of EUR 500,000/MW and OpEX between 6% and 10%. To calculate the capital recovery factor (CRF) (7), an interest rate r of 5%, 7.5%, and 10% has been set over a period of 20 years. This followed on the approach used in [63]:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Converter Survivability and Production over Time

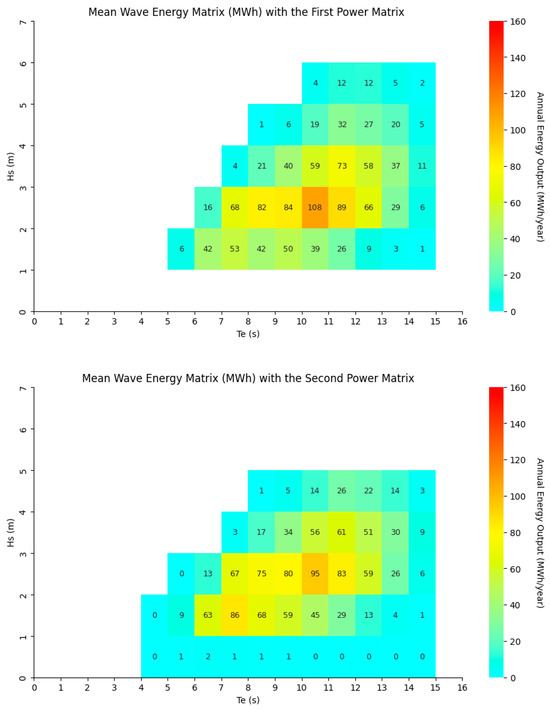

Starting with the energy yield estimates, by combining the resource and power matrices, the average AEP converted by the WEC (Figure 7) was obtained. This combined matrix also allows the identification of the sea-states for which the energy conversion is greater. As explained previously, the second power matrix was obtained through Froude similarity and a correction factor. In order to verify this transformation, the bias and RMSE were calculated and reported in Table 3. Finally, the normalized bias of −2.3% shows that the 600 kW model is well-calibrated and exhibits only a small overall offset, and the overall bias indicates that the 600 kW model tends to underestimate reality. However, the normalized RMSE shows that local variations may exist, particularly for significant power levels. Thus, while the 600 kW model accurately reproduces the overall trend of the 1000 kW matrix and allows for a comparison of the two matrices proposed in this article, the RMSE reveals the existence of local discrepancies that may reflect dynamic effects not captured by Froude similarity, which could be addressed in future research. Still, the RMSE discrepancies exhibit their own limitations here, and a fairer basis of comparison should be done with commercial equivalents. The scaling approach was employed precisely to circumvent the absence of a 600 kW variant, so a direct comparison with the 1000 kW variant is not as fair as it would be with an actual commercial variant of equal rating.

Figure 7.

Mean annual energy produced, calculated from 44 years of data for each of the two power matrices.

Table 3.

Table showing the bias, the RMSE, and the relative RMSE between the initial power matrix of 1000 kW and the reduced power matrix of 600 kW for overall and standardized values.

Despite the fact that the theoretical power absorbed by the WEC is greater for waves above 4 m, the converter generates more energy for between 1 m and 4 m, which can be explained by the prevalence of waves within this range.

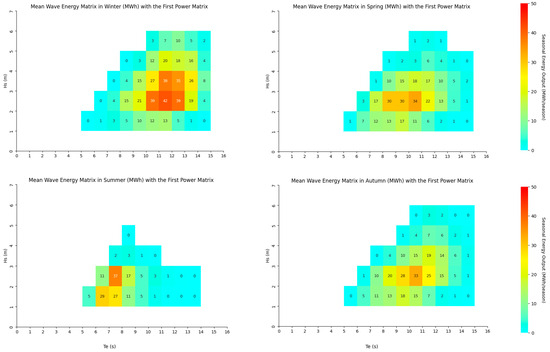

As expected, there is also a disparity between seasons, with a wider range of heights and periods in Winter. above 5 m and around 14 s are more frequent than in other seasons (Figure 8). Conversely, in Summer, the majority of waves are less than 3 m high, with a mostly under 9 s. Thus, an increase in energy production was expected in Winter, given the enhanced overlap with higher values of the WEC power matrix. These seasonal disparities can be observed for each power matrix (Supplementary Materials S1), which, although expected, raise concerns regarding excess energy storage, demand coverage and operational efficiency.

Figure 8.

Average seasonal energy produced, calculated from 44 years of data for the first power matrix studied.

While a WEC designed for smaller waves may be able to convert sufficient energy, it may also be more sensitive to extreme waves. From a survivability perspective, while the first power matrix shows that the converter appears to be designed for waves reaching 6 m, the 600 kW converter could be affected by beyond 5 m, which warrants an investigation into the occurrence frequency of such “extreme” events.

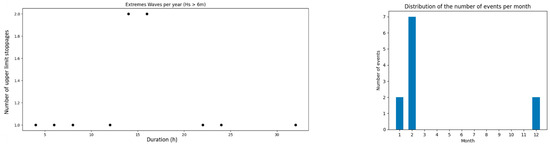

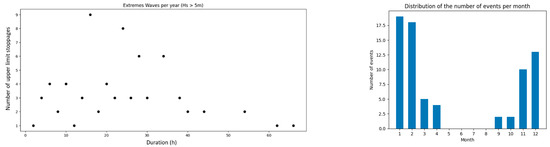

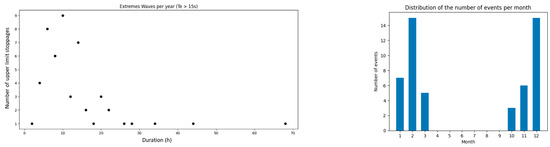

Considering extreme waves as above 6 m, 168 h spread over 11 exceedance events were observed (Figure 9), suggesting that these are rare events with a low probability of being observed several times per year (average of about one event per 4 years). However, these waves could damage the 1000 kW converter (Figure 4), which is not designed for these wave heights. Furthermore, some occurrences last more than 24 h, resulting in prolonged extreme loads on the WEC and requiring suitable durability. As for beyond 5 m (second matrix), there were 1724 h (Figure 10), with some events lasting several days. Furthermore, these are mainly observed during the Winter, though some recordings exist in early Spring and late Autumn. Therefore, the 600 kW variant should be more susceptible to extreme events, given their greater frequency.

Figure 9.

Graph showing the number of events where Hs exceeded 6 m, according to their duration—associated with a histogram illustrating the distribution of these events throughout the year.

Figure 10.

Graph showing the number of events where the Hs exceeded 5 m, according to their duration—associated with a histogram illustrating the distribution of these events throughout the year.

Despite the major role of , waves with a high period could also affect the WaveRoller, as it is not designed to produce energy beyond 15 s. Yet, there were 692 h where the site was exposed to such wave periods, namely between October and March (Figure 11). Nevertheless, it is likely that some of these waves are coupled with extreme heights, which can be evaluated by more complex approaches, such as copulas or environmental contours, as recommended in international standards [25].

Figure 11.

Graph showing the number of events where the Te exceeded 15 s, according to their duration—associated with a histogram illustrating the distribution of these events throughout the year.

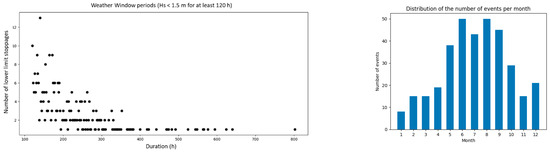

Using the same threshold exceedance process, weather windows required for installation, access, and maintenance operations were determined. There were 3154 suitable days for these activities, spread throughout the year but mostly concentrated around the Summer (Figure 12), as expected from the more moderate wave climate during this season. Furthermore, as the WaveRoller produces almost no energy at heights below 1 m, approximately 32,000 h during which this lower threshold was not exceeded were identified. This can last several days and occur at any time of the year, though less often in late Winter and early Spring, given the harsher wave climate (Figure 13).

Figure 12.

Graph showing favorable weather windows, based on their duration—associated with a histogram illustrating the distribution of these windows throughout the year.

Figure 13.

Graph showing the number of events where the Hs was less than 1 m, according to their duration—associated with a histogram illustrating the distribution of these events throughout the year.

In order to further study WEC survivability, the probability and intensity of future events have been modeled. To do this, using the methods described in Section 2, the expected maximum for the and over 10, 50, and 100-year return periods after 2021, the last year used from the dataset, was extrapolated.

To determine the , necessary for parameterizing the PoT method, the preceding results were used. However, the graphs showed that these extreme events did not last more than 70 h. Therefore, to promote event uniqueness, the parameter = 70 h was imposed. This also promotes statistical independence, in order to adjust the model and obtain a better extrapolation.

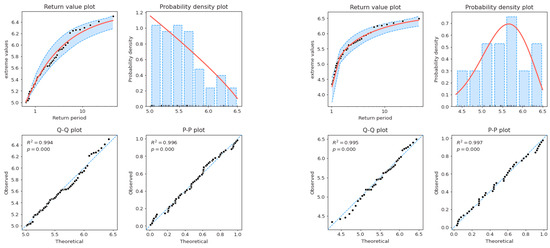

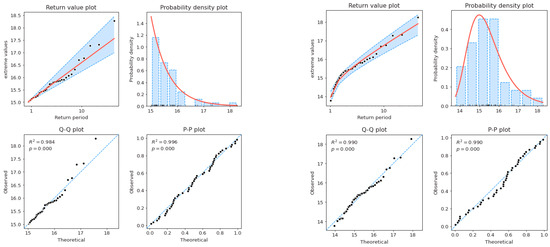

With the GPD, after sampling by PoT, the model predicts a baseline maximum of 6.48 m for a 100-year return period (Table 4). By comparison, over the 44-year dataset, a maximum of 6.50 m was observed. Though plausible, this model may be providing a low estimate, which is corroborated by visualizing the observed values. Despite the good agreement seen in the Q-Q and P-P plots, the actual values are on the upper end of the CI, leaving a small margin of error (Figure 14).

Table 4.

Summary table showing the maximum Hs and CI range estimated using the GPD/GEV models under different return periods.

Figure 14.

Graphs showing the Hs analysis of the models using the GPD (PoT sampling, left) and GEV (BM sampling, right), respectively.

With BM sampling and GEV distribution, a similar model was obtained. Nonetheless, the maximum assumed in a 100-year return period is 6.51 m, slightly higher than the observed value, which is more consistent. In addition, the CI is further from the observed extremes, offering better margins and a more conservative outcome. There is also a slight improvement in Q-Q and P-P plots results.

Overall, both models predict extreme values close to those already observed. Thus, although these extrapolations do not anticipate significant increases, they remain based on historical data. While local wave climate, water depth, and bathymetry may condition the maximum , follow-up studies should integrate RCP CC scenarios and evaluate their impact. Note also that parametrization was done by resorting to the Maximum Likelihood Estimation built into pyextremes, which yielded location, scale, and shape values of 5.35, 0.60, and 0.45 (GEV) and 5.00, 0.86, and −0.55 (GPD), respectively. The shape parameter indicates a Fréchet family for the GEV distribution, but no special case for the GPD.

As with , fitting maximum with GPD and GEV has been studied for identical return periods. Given that the maximum observed period was 18.27 s, the 18.10 s (Table 5) expected over a 100-year return period, as predicted by the GPD, may be underestimating reality. This is confirmed by visualizing the actual values, which shows an underestimation of extreme , particularly above 10 s, in the Q-Q plots, with very wide CIs (Figure 15). The second model, using GEV, seems to better predict an increase in , with an estimate of 18.56 s under a 100-year return period. In addition, the GEV suggests a value between 17.85 s and 19.13 s, a smaller range than that of the previous model. Furthermore, analysis of the Q-Q plot shows that the second model provides better agreement at higher quantiles while retaining a good fit in the P-P plot. Therefore, the GEV is again favored for predicting extreme values.

Table 5.

Summary table showing the maximum Te and CI range estimated using the GPD/GEV models under different return periods.

Figure 15.

Graphs showing the Te analysis of the models using the GPD (PoT sampling, left) and GEV (BM sampling, right), respectively.

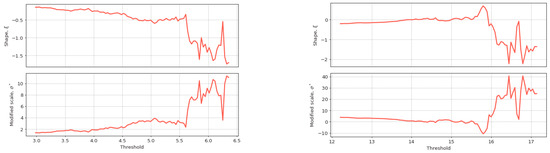

To complement, the stability graphs of and following the GPD were plotted (Figure 16). The observed parameters seem to have become unstable after 5.5 m and 15.5 s. This reinforces the 5.0 m threshold selection, as the GPD extrapolation becomes less accurate for extreme values exceeding these thresholds.

Figure 16.

Stability graph of parameters Hs (left) and Te (right), referring to the GPD.

In order to analyze the evolution of wave parameters in greater detail, different percentiles over three time periods have been studied, as mentioned in Section 2. The results are presented in Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19. When comparing the periods, little variation in during the Summer was observed. However, there are significant differences between January and February, particularly for extreme values, with higher and a concentration around the Winter months, during the latter time period. Changes are also observed between March and April for those values with a lower and between October and November for the highest 25% of values, where a peak of extreme values appears to have moved from October to November. Conjugated with the January–February patterns, this points toward more intense and concentrated extreme events, which can be hazardous for WEC survivability and maintenance. Finally, between November and December, variations were observed in the lowest values with an increase in wave height, which could eventually allow more energy to be produced.

Figure 17.

Hs percentiles over 44 years of data, followed by a smoothed comparison of the percentiles for the three time periods, represented by dotted lines that thicken over time and a solid line for the most recent period.

Figure 18.

Te percentiles over 44 years of data, followed by a smoothed comparison of the percentiles for the three time periods, represented by dotted lines that thicken over time and a solid line for the most recent period.

Figure 19.

Percentiles of Dir coefficients over 44 years of data, followed by a smoothed comparison of percentiles for the three time periods, represented by dotted lines that thicken over time and a solid line for the most recent period.

For , variations are mainly observed for the lowest 25% of values between the second and third months with higher values. Extreme periods appear to undergo little change, but a positive variation can be noted in February and November for the most extreme 1%, which could indicate a future increase in extreme periods. This would be consistent with the predictions made with the BM-GEV. Lastly, the Dir seems to change little overall, with 90% of values having a coefficient greater than 0.9, meaning that the direction does not hinder the WEC’s performance consistently or significantly. However, looking at the P1 and P5 percentiles, a drop in WEC efficiency to 20% caused by the Dir is sometimes observed. Still, when comparing time periods, the tendency is for higher coefficients with lesser variability, which is desirable.

To further investigate long-term trends, the Mann–Kendall hypothesis test is employed, examining annual, monthly, and seasonal variations in . Thus, when comparing years, a general trend was observed where small waves seemed to be gaining strength, with their height and period increasing (Table 6 and Table 7).

Table 6.

Table showing the values obtained with the Mann–Kendall test to determine the presence of annual trends in .

Table 7.

Table showing the values obtained with the Mann–Kendall test to determine the presence of annual trends over the Te.

Overall, p-values were <0.05 up to the median, which may indicate a slight upward trend. The trends are also visible on a monthly and seasonal basis. This is in contrast to the period, which only has its smallest 1% values increasing significantly on a seasonal basis (Supplementary Materials S2). Thus, the trend observed for , which is detected at different scales for the same percentiles, is significant and visible at several scales. By contrast, the trends detected for , which are mainly at the annual scale, show a more diluted evolution over time, masked at smaller scales. These remarks can be impactful in terms of AEP, given the expected shift of occurrences in the wave resource matrix towards higher and, less so, . This may be favorable, should the shift overlap with higher values from the corresponding sea-states of the wave power matrix. It also showcases the potential non-stationary nature of the dataset, though essentially at lower percentiles. For higher ones, no increments were deemed significant, which can also be beneficial from a survivability perspective. These results reinforce the GPD and GEV analyses performed for . In contrast, the GEV model applied to revealed a trend towards increasing extreme values. Furthermore, increases were observed for the most extreme waves (P99) during certain months. Thus, this absence of a significant annual trend for these periods could rather suggest the occurrence of seasonal extreme wave events characterized by increasingly significant values.

In terms of direction, no significant annual change was observed, though P5 to P50 exhibit relatively low p-values (Table 8), which may indicate a slight upward trend. However, for the first half (Supplementary Materials S3), there is a monthly and seasonal upward trend, sometimes very pronounced, particularly for the first percentiles. This shows a more localized evolution over time, masked on an annual scale. This agrees better with the outcomes in Figure 19. These observations suggest that the energy converted by the WEC may increase over time, without any significant extreme value increase. Nevertheless, even if no trend is observed for extreme events, rare and more severe events than those already observed may occur. Still, as also suggested by the GPD and GEV models, their magnitude should not increase considerably.

Table 8.

Table showing the values obtained with the Mann–Kendall test to determine the presence of annual trends in the coefficients of Dir.

3.2. Dataset Reduction

To reduce datasets for a more efficient application of complementary analysis, such as WPMs, a K-Means clustering algorithm was used. In order to obtain a MAPE score ≤ 10% for a minimum number of clusters, an iterative approach was carried out, resulting in 11 clusters (Table 9) with a MAPE of 10.0% for , 8.2% for , and 4.0% for Dir with the raw data that was not adapted to the matrices. Nonetheless, MAPEs can be slightly reduced by removing data corresponding to waves outside the WEC production limits, which are given by the two power matrices (Supplementary Materials S3, Table 9).

Table 9.

Table representing the MAPE (%) obtained after each clustering by K-Means according to the number of clusters, and the associated power matrix in the case of the last two columns (truncated matrix limits).

The literature analysis implied running the algorithm iteratively, with different parameters and numbers of clusters. After selecting the parameters, different numbers of clusters were tested. The results and method presented in this paper correspond to the parameters that yielded the best results. As the MAPE fell below 10% for each parameter between 10 and 15 clusters, 11 clusters yielded the best result with the fewest clusters. Furthermore, the clustering on Dir was very stable, with the MAPE changing very little and remaining below 5%. Since most directions were grouped around 323° with limited variability, this was expected. Also, even when clustering is performed only on sea-states within the power matrix range, the Dir MAPE varies slightly, decreasing (11-1 and 11-2). This could be explained by the removal of outlying values that deviate far from the average ones, though with a negligible impact. This consistency in Dir is reassuring for energy production, as it allows the WEC to be placed in a fixed direction while ensuring a high and consistent direction-bound conversion coefficient.

In order to verify the directional profile of the clusters compared to that of the original dataset, the cluster values were superimposed on a wave rose diagram, Figure 20. The centroids revolved around a direction of 324°, being well aligned with the site’s wave rose diagram.

Figure 20.

Wave rose diagram at the Peniche site.

In the clustering obtained, group 5 (Figure 21) has few elements compared to the other groups. However, it remains necessary, since it represents sea-states with extreme wave heights (Figure 22).

Figure 21.

Distribution of clusters obtained with the K-Means clustering algorithm and representation of MAPEs for each parameter relative to the 5% (green) and 10% (orange) limits.

Figure 22.

Data distributed among the 11 clusters, after using the K-Means clustering algorithm.

In order to verify the significance of this clustering, a Student’s t-test was performed by comparing the AEPs obtained from the K-Means clustering with those calculated from the original data. For a confidence level of 95%, a critical t-value of 2.017 was obtained, while for the AEPs in both power matrices scores well above it were obtained (Table 10). Thus, there are statistically significant differences between the K-Means adjusted and original data AEPs. From a practical point of view, though, for the first matrix, the effect is moderate (≈4% difference), while for the second, the significance is stronger (16% difference).

Table 10.

Results obtained for the mean of the differences between the AEP obtained with the initial and reduced data , the standard deviation of the differences sd, the t-score and the p-value.

The CIs are similar with the z (or normal/Gaussian) and t distributions (Table 11), which suggests a sufficient sample size for assuming a normally distributed AEP. The good agreement of the Q-Q and P-P curves supports this hypothesis. Regardless, significantly different results are observed between the studied matrices. In detail, K-Means tends to overestimate the AEP—mainly for the 600 kW variant—which suggests sensitivity to the wave power matrix and warrants caution upon using K-Means instead of the original data. Even so, this can be attributed to the cumulative discrepancies inherited from the and MAPEs, as reported in [32] and given the physical relationship between wave power, height and period. Lastly, the initial data AEP ranges are similar for both WaveRoller variants, though slightly benefiting the first matrix. Nevertheless, for a fairer basis of comparison, the LCoE estimates are addressed next.

Table 11.

Results obtained for the average AEP, with the initial and reduced data , and the confidence intervals from the z and t distributions.

3.3. Energy Production and Levelized Cost of Energy

The final objectives of this paper involve estimating the WEC’s capacity to meet the energy demand of the offshore aquaculture site, assuming that a single WaveRoller is sufficient. This was evaluated based on Section 2’s assumptions, and seasonal needs were calculated according to the stages of mussel development, equipment used, and the different annual expenditures (Table 2). Summer expenditures are higher due to the harvesting period. Then, for each power matrix and scenario, the AEP was calculated using the initial and K-Means reduced data. Based on the AEPs, the normal distribution’s z-score (Supplementary Materials S6) was calculated to determine the probability that a single WaveRoller would not meet the aquaculture energy needs. The ensuing results showed that, for each case, the probability of the energy demand exceeding the WEC’s output tends towards 0 (Table 12, Supplementary Materials S4). For this probability to be 2.5%, the demand must be at least 954 MWh/yr (first power matrix), almost double the range maximum value.

Table 12.

Probability that the AEP of a WaveRoller unit, with the first power matrix, will be less than the annual energy requirements of mussel farming for different scenarios and based on initial (zi and pi) and reduced data (zk and pk).

Recalling that demand is higher in Summer, during the harvest season, it became pertinent to estimate the same probability adapted to the Summertime. For the second matrix, a p-value of up to 0.27 is observed (Supplementary Materials S4), becoming significant for the highest needs. As for the first matrix, the demand exceedance probability increases, with a p-value of 0.76 for seasonal needs of 180.5 MWh (Table 13). Consequently, while a single unit is likely to cover the annual energy demands, the Summer season may require additional units for a full coverage—mainly if the first WEC variant is selected—or assume a partial demand coverage.

Table 13.

Probability that the Summer energy production of a WaveRoller unit, with the first power matrix, will be less than the Summer energy requirements of mussel farming, for different scenarios.

Thus, while the average AEP of the 1000 kW WaveRoller is slightly greater than that of the 600 kW variant, the latter would produce more, in Summer, than the first variant. This can be explained by the presence of smaller waves during this season, which overlap better with the second power matrix. By contrast, the first matrix yields more power at higher sea-states, which are less frequent in Summer.

Adding to the outcomes of the percentiles and Mann–Kendall test analysis, it becomes evident that resource variability should not be ignored for a device such as the WaveRoller. Firstly, its power matrix has limits which can be surpassed either at its upper or lower thresholds. This relates to availability, as in some periods the WEC may not be converting any energy due to extreme conditions or insufficient wave-induced motions. As these periods can vary between years and seasons, for example, it is pertinent to develop a system that mitigates consistently these threshold exceedances (e.g., by promoting a good overlap between the wave power matrix and the wave resource matrices throughout the years/seasons, as feasible). Secondly, the percentiles and Mann–Kendall point toward a potential increase of the AEP through a better overlap between future sea-states, at lower percentiles, and higher wave power matrix values. This would not be detected in a deterministic approach, by default. Another positive trend comes from the Dir, as there seems to be no consistent trend. For a device like the WaveRoller, which is sensitive to the orientation of waves given its rotational single mode of oscillation, having a limited dispersion of the Dir attenuates eventual energy conversion losses due to misalignment between the WEC and the incoming waves. Thirdly, the seasonal variability can cause “worst-case scenario” situations with reduced AEP and increased energy demand, as seen for the Summer. Consequently, should a single unit exhibit a significant risk of not meeting the energy requirements, it may be necessary to either develop a more suitable variant, re-scaling it, or consider a second unit, as a backup system and to increase the probability that the energy demand targets will always be met.

It is equally insightful to compute the LCoE values associated with the different power matrices examined in order to assess the economic interest of incorporating the WaveRoller. To do this, the main CapEX and OpEX are summarized into scenarios, after which the LCoE values are calculated based on the discount rate and the AEP per matrix, using the initial and reduced data (Table 14 and Table 15 and Supplementary Materials S5).

Table 14.

Table showing the LCoE produced according to the r, CapEX, and OpEX taking into account the average AEP calculated using the initial data for the first matrix.

Table 15.

Table showing the LCoE produced according to the r, CapEX, and OpEX taking into account the average AEP calculated using data reduced by clustering for the first matrix.

First, the LCoE calculation highlights the inherent differences between the initial and reduced AEP data. While the two cost ranges overlap quite well in the first matrix, they show slightly larger deviations for the second matrix (Supplementary Materials S5). Indeed, an average error around 14% was found for the LCoE of the second matrix for different combinations of CapEX, OpEX, and r, compared to an error between 3% and 4% for the first matrix. This confirms the significant statistical differences discussed before, further illustrating the caution that should be taken when using K-Means. Furthermore, it could show that the first matrix has better data correspondence. Additionally, the highest costs are found with the second matrix (initial data), which is explained by a lower estimated AEP with this matrix (Table 11), thus increasing the LCoE. For the K-Means data, the order is reversed, always in line with the AEP patterns. Still, the magnitudes are similar overall across the two matrices.

More importantly, from an economic viability perspective, only scenarios on the lower end of CapEX, OpEX and r yield promising values (below 200 EUR/MWh), while very few provide LCoE under 150 EUR/MWh. By comparing them with IRENA’s recent report of energy costs [64] and the electricity prices practiced by the Iberian market—MIBEL—the LCoE of the WaveRoller remains likely high.

3.4. Aquaculture: Species Selection

Although temperature is often the most impactful criterion on aquaculture species, and therefore the most decisive aspect for choosing species adapted to the site, there are other important elements to take into account, such as phytoplankton availability (e.g., via chlorophyll-a concentration) [13,65]. In this study, the local waters are oligotrophic, with a chlorophyll-a concentration quite low for mussels (0.36 μg/L). However, bivalves are known for their efficient filtration, which can improve water quality by absorbing nutrients and organic detritus. But they also feed on phytoplankton, which can then further reduce the chlorophyll-a concentration. Therefore, small-scale mussel aquaculture could be considered to avoid large-scale phytoplankton consumption. In fact, the low measured concentrations may already reflect the impact of the identified mussel farm. In addition, mussels excrete (pseudo) feces, which, under intensive production, can increase sedimentation and impact the benthic environment.

It is essential to consider these different aspects and the potential impact that mussel farming could have on the environment. Nevertheless, one could consider the implementation of an IMTA to filter mussel waste in association with organisms such as algae, which would absorb the dissolved elements released by the degradation of this waste [65,66]. Nonetheless, it could be interesting, for a future study, to analyze how to guarantee sufficient availability of phytoplankton for marine mussel farms in open environments, without altering the ecological balance.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents, based on reference studies in the literature, an extensive assessment of co-located offshore aquaculture and WECs, leveraging a case study conducted near Peniche, Portugal. The analysis focused on the WEC survivability and variability of resources over time, as well as a proposal to reduce the sea-state dataset. The LCoE and energy production of the WaveRoller were estimated, and production was compared to the energy demands of mussel farming (annual and Summertime).

It was found that a 1000 kW WaveRoller was more adequate for waves above 6 m, in contrast to the 600 kW variant’s 5 m limit. These extreme waves are sporadic, but they can last for several days and generate large wave loads, leading to a risk of damage. Still, the site offers several weather windows conducive to maintenance work, though mostly in Summer and while being exposed to sea conditions that are too calm for the WEC to produce energy. Calm sea-states can actually lead to greater energy conversion losses due to downtimes, and it would be important to consider further re-scaling or power matrix adjustment through different generators in order to better harness these sea-states.

On extreme events extrapolation, BM sampling combined with a fitted GEV yielded the most plausible results. Under 10-, 50-, and 100-year return periods, the GEV pointed to expected ranges of 6.19–6.45–6.51 m for and 16.74–18.02–18.56 s for . These do exceed the power matrix thresholds of both variants but do not significantly surpass the maximum recorded values. Given the 8 to 20 m operational range of the WaveRoller, these values are in line with the limitations imposed by the local water depth. Therefore, they can serve as initial design values for WEC survivability design. Coupled with a trend analysis based on the Mann–Kendall test on data percentiles, no significant increments of extremes magnitude were identified, though a concentration of occurrences in Winter may exist. The test also pointed toward a growth in the WaveRoller’s energy conversion over time, with an increase in the of the smallest waves. This hints toward a potential non-stationary behavior of the data, at least at lower percentiles, that ought to be investigated in the future (e.g., with specialized software like Marinetools). This is a key finding that should be considered in other WEC studies, given its long-term importance.

In terms of dataset reduction, the K-Means clustering algorithm with 11 clusters resulted in an MAPE of less than 10% for all three sea-state parameters. However, the t-test and difference percentages indicated a significant deviation, ranging from 4% to 16%. Moreover, the AEP and the probability that a WaveRoller unit would be unable to meet aquaculture needs were calculated for each hypothesis: close to 0 for annual needs. By contrast, Summer requires the most energy due to harvesting, and scenarios in which demand coverage may not be assured by a single unit were identified. It is recommended to consider the inclusion of storage systems, a backup WaveRoller unit, and/or partial demand coverage in conjunction with other energy sources (e.g., locally sourced solar or wind, or through the mainland electricity grid). These would incur additional costs but also mitigate energy fluctuations, provide redundancy in wave energy conversion, and enable earnings through excess energy sales to the grid while covering demand in lower production periods. Finally, the LCoE CIs were calculated, indicating rather uncompetitive values as low as 145–152 EUR/MWh. These are also somewhat sensitive to the selected power matrix and the reference data (initial or K-Means reduced), and it will be important to further confirm whether there is a relevant difference between the original and K-Means datasets when estimating the AEP and, afterwards, the LCoE. This also applies to the actual probability distributions of the LCoE and its terms.

Future studies could build on this work to analyze other co-locations. Also, given the divergence of results from the different assumptions made about the WEC, it would be interesting to repeat this analysis with more scenarios and case studies. A promising approach involves incorporating probability distribution functions into the cost and rate variables, followed by a Monte Carlo simulation. This would yield sample values to better assess the actual LCoE distribution (t, Gaussian, Reciprocal Normal, or others) as well as its parameters and CIs. In addition to the survivability and environmental change over time, the use of RCP scenarios could be considered. Finally, if this co-location meets the needs of local operators while reducing the environmental impact caused by offshore aquaculture, it would be pertinent to study in detail the impact these structures would have throughout their life cycle [4].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/en18225934/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and D.C.; Methodology, M.B. and D.C.; Software, M.B. and D.C.; Formal Analysis, M.B. and D.C.; Resources, G.G., D.C., A.G.M. and P.R.-S.; Investigation, M.B. and D.C.; Data Curation, M.B., D.C., G.G. and C.S.; Validation, M.B., D.C., G.G. and P.R.-S.; Investigation, M.B. and D.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, D.C., G.G., C.S., A.G.M. and P.R.-S.; Visualization, M.B. and D.C.; Supervision, D.C., G.G. and P.R.-S.; Project Administration, D.C., G.G. and P.R.-S.; Funding Acquisition, D.C., G.G. and P.R.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

G.G. would like to acknowledge the funding received from the European Research Executive Agency (REA) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101206509. G.G. would like to also acknowledge the financial support received through the Stimulus of Scientific Employment program of the FCT, specifically via an individual grant referenced 2022.04954.CEECIND/CP1728/CT0007. D.C. would like to acknowledge funding in the form of a Doctorate-Initial Level Position within the scope of the Project “HYDEA—Boosting the hydrogen transition in the Atlantic Area ports”, with the reference EAPA_0057/2022, funded by the European Union in the scope of the Interreg ATLANTIC AREA 2021–2027 program.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gouel, C.; Guimbard, H. La demande alimentaire mondiale en 2050. La Lettre du CEPII 2017, 377, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Lamine, E.; Schickele, A.; Guidetti, P.; Allemand, D.; Hilmi, N.; Raybaud, V. Redistribution of fisheries catch potential in Mediterranean and North European waters under climate change scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 879, 163055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.Y.; Brennan, R.S.; Monk, C.T.; Jentoft, S.; Helmerson, C.; Dierking, J.; Hüssy, K.; Kokubun, É.E.; Fuss, J.; Krause-Kyora, B.; et al. Genomic evidence for fisheries-induced evolution in Eastern Baltic cod. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadr9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024: Blue Transformation in Action 2024; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; p. 264. ISBN 978-92-5-138763-4. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Wen, X.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z. A systematic review on aquaculture wastewater: Pollutants, impacts, and treatment technology. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Liang, J.; Huang, X.; Yu, F.; Guo, S. Navigating offshore aquaculture: Efficient strategies for policymakers in transition. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 249, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custódio, M.; Villasante, S.; Calado, R.; Lillebø, A.I. Valuation of Ecosystem Services to promote sustainable aquaculture practices. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. EU Aquaculture Assistance Mechanism. 25. How Does the EU Approach the Use of Antibiotics and Antimicrobial Resistance in Aquaculture? Available online: https://aquaculture.ec.europa.eu/faq/25-how-does-eu-approach-use-antibiotics-and-antimicrobial-resistance-aquaculture (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EC) No 710/2009 of 5 August 2009 Amending Regulation (EC) No 889/2008. EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/710/oj/eng (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 508/2014 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and Repealing Council Regulations (EC). EN-EUR-Lex. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2014/508/oj/eng (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Sun, K.; Zhang, C.; Wu, W.; Teng, F. Numerical assessment of the environmental impacts of deep sea cage culture in the Yellow Sea, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 135752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, D.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Ferradosa, T.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Wave energy conversion energizing offshore aquaculture: Prospects along the Portuguese coastline. Renew. Energy 2023, 204, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueira, M.; Pombo, A.; Borges, C.; Brito, A.C.; Zacarias, N.; Esteves, R.; Palma, C. Potential for Coastal and Offshore Aquaculture in Portugal: Insights from Physico-Chemical and Oceanographic Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Energy Review 2025. IEA Paris. Licence: CC BY 4.0. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Calvin, K.; Dasgupta, D.; Krinner, G.; Mukherji, A.; Thorne, P.W.; Trisos, C.; Romero, J.; Aldunce, P.; Barrett, K.; Blanco, G.; et al. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergov-ernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khojasteh, D.; Shamsipour, A.; Huang, L.; Tavakoli, S.; Haghani, M.; Flocard, F.; Farzadkhoo, M.; Iglesias, G.; Hemer, M.; Lewis, M.; et al. A large-scale review of wave and tidal energy research over the last 20 years. Ocean Eng. 2023, 282, 114995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira-Pinto, F.; Iglesias, G.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Deng, Z.D. Preface to Special Topic: Marine Renewable Energy. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2015, 7, 061601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, G.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Ramos, V.; Taveira-Pinto, F. On the Development of an Offshore Version of the CECO Wave Energy Converter. Energies 2020, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, G.; Temiz, I.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Shahroozi, Z.; Ramos, V.; Göteman, M.; Engström, J.; Day, S.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Wave Energy Converter Power Take-Off System Scaling and Physical Modelling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannini, G.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Ramos, V.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Wave energy converters design combining hydrodynamic performance and structural assessment. Energy 2022, 249, 123641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Wang, Z.; Ding, W.; Sheng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Wang, W. Feasibility of Co-locating wave energy converters with offshore aquaculture: The Pioneering case study of China’s Penghu platform. Ocean Eng. 2023, 288, 116039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavelli, L.; Freeman, M.; Grear, M.; Briggs, C. Co-locating wave energy and offshore aquaculture in Puerto Rico. In Proceedings of the Pan American Marine Energy Conference (PAMEC 2024), Barranquilla, Colombia, 22–24 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, A.G.; Ramos, V.; Giannini, G.; Rosa Santos, P.; das Neves, L.; Taveira-Pinto, F. The impact of climate change on the wave energy resource potential of the Atlantic Coast of Iberian Peninsula. Ocean Eng. 2023, 284, 115451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Iturricastillo, N.; Nic Guidhir, M.; Ulazia, A.; Ringwood, J.V. Extreme wave analysis for marine renewable energies in Ireland. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNV. DNV Rules and Standards for Offshore Units—July 2023 Edition. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/news/2023/dnv-rules-and-standards-for-offshore-units-july-2023-edition-245184/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- DNV. DNV-SE-0120 Certification of Wave Energy Converters and Arrays. Edition 2023-03. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/energy/standards-guidelines/dnv-se-0190-certification-of-wave-energy-converters-and-arrays/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Maldonado, A.D.; Galparsoro, I.; Mandiola, G.; de Santiago, I.; Garnier, R.; Pouso, S.; Borja, Á.; Menchaca, I.; Marina, D.; Zubiate, L.; et al. A Bayesian Network model to identify suitable areas for offshore wave energy farms, in the framework of ecosystem approach to marine spatial planning. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satymov, R.; Bogdanov, D.; Dadashi, M.; Lavidas, G.; Breyer, C. Techno-economic assessment of global and regional wave energy resource potentials and profiles in hourly resolution. Appl. Energy 2024, 364, 123119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, W.; Zang, H.; Yang, H. Wind Power Interval Forecasting Based on Confidence Interval Optimization. Energies 2018, 11, 3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malliouri, D.I.; Memos, C.D.; Soukissian, T.H.; Tsoukala, V.K. Assessing failure probability of coastal structures based on probabilistic representation of sea conditions at the structures’ location. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 89, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru, J.; Seland, T.S.; Dai, J.; Jiang, Z. Life cycle cost analysis of an offshore floating photovoltaic concept in the North Sea. Renew. Energy 2025, 249, 122981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, D.; Ramos, V.; Teixeira-Duarte, F.; Taveira-Pinto, F.V.C.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Assessment of electricity production and coastal protection of a nearshore 500 MW wave farm in the north-western Portuguese coast. Appl. Energy 2025, 379, 124950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobos, M.; Otiñar, P.; Magaña, P.; Lira-Loarca, A.; Baquerizo, A. MarineTools.temporal: A Python package to simulate Earth and environmental time series. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 150, 105359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garavelli, L.; Freeman, M.C.; Tugade, L.G.; Greene, D.; McNally, J. A feasibility assessment for co-locating and powering offshore aquaculture with wave energy in the United States. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2022, 225, 106242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Rusu, E.; Guedes Soares, C. The Effect of a Wave Energy Farm Protecting an Aquaculture Installation. Energies 2018, 11, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OES. An International Evaluation and Guidance Framework for Ocean Energy Technology; IEA-OES: Lisboa, Portugal, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Majidi, A.G.; Ramos, V.; Rosa-Santos, P.; das Neves, L.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Power production assessment of wave energy converters in mainland Portugal. Renew. Energy 2025, 243, 122540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. EIFAAC-Data. FishStat: Global capture production 1950–2022. European Inland Fisheries and Aquaculture Advisory Com-mission (EIFAAC). Available online: https://www.fao.org/eifaac/data/en (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Rusu, E.; Soares, C.G. Coastal impact induced by a Pelamis wave farm operating in the Portuguese nearshore. Renew. Energy 2013, 58, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PSOEM—Plano de Situação Ordenamento do Espaço Marítimo RCM. DGRM Geoportal. Available online: https://webgis.dgrm.mm.gov.pt/portal/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=15c32cf0500c43148f97270db0c1f584# (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Ocean Energy Europe. ONDEP Project Secures €19M EU Funding to Deploy WaveRoller Array in Portugal. Available online: https://www.oceanenergy-europe.eu/industry-news/ondep-project-secures-e19m-eu-funding-to-deploy-waveroller-array-in-portugal/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Marine Energy. AW-Energy Splashes WaveRoller Off Portugal. Offshore Energy 2019. Available online: https://www.offshore-energy.biz/aw-energy-splashes-waveroller-off-portugal/ (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- DGRM. Plano de Afetação para Energias Renováveis Offshore (PAER). Ordenamento do Mar Português (PSOEM). Available online: https://www.psoem.pt/plano-de-afetacao-para-energias-renovaveis-offshore/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Casamajor, M.-N. Moules (Mytilus Edulis)—Ifremer 00567-67875 [Image]. Available online: https://image.ifremer.fr/data/00567/67875/ (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Dias, F.; Renzi, E.; Gallagher, S.; Sarkar, D.; Wei, Y.; Abadie, T.; Cummins, C.; Rafiee, A. Analytical and computational modelling for wave energy systems: The example of oscillating wave surge converters. Acta Mech. Sin. 2017, 33, 647–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGRM. Títulos de Utilização Privativa do Espaço Marítimo N. 13/12/2016/DGRM. 2016. Available online: https://webgis.dgrm.mm.gov.pt/portal/sharing/rest/content/items/6df8794f2c43411f94db39aa3a3f07b4/data (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- AW-Energy. Wave-Roller. 2024. Available online: https://projects.research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/en/projects/success-stories/all/waveroller-turning-waves-electricity (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Morim, J.; Cartwright, N.; Hemer, M.; Etemad-Shahidi, A.; Strauss, D. Inter- and intra-annual variability of potential power production from wave energy converters. Energy 2019, 169, 1224–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Pinto, S.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Taveira-Pinto, F. Electricity supply to offshore oil and gas platforms from renewable ocean wave energy: Overview and case study analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 186, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, V.; Giannini, G.; Calheiros-Cabral, T.; Rosa-Santos, P.; Taveira-Pinto, F. An Integrated Approach to Assessing the Wave Potential for the Energy Supply of Ports: A Case Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, J.M. Carbon Footprint of Scottish Suspended Mussels and Intertidal Roysters; Scottish Aquaculture Research Forum: Pitlochry, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-907266-44-7. [Google Scholar]

- DGRM. Títulos de Utilização Privativa do Espaço Marítimo N. 17/03/2017/DGRM. 2017. Available online: https://webgis.dgrm.mm.gov.pt/portal/sharing/rest/content/items/c9dbbc7f63c044cb895d5a034b0fc6c9/data (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Polo, D.; Álvarez, C.; Díez, J.; Darriba, S.; Longa, Á.; Romalde, J.L. Viral elimination during commercial depuration of shellfish. Food Control 2014, 43, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; EUMOFA. Directorate General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. In Case Study—Mussel in the EU: Price Structure in the Supply Chain: Focus on Spain, France, Italy and Ireland; European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.; Lovatelli, A.; Ababouch, L. Purification des Coquillages Bivalves: Aspects Fondamentaux et Pratiques; FAO Document Technique sur les Pêches; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; ISBN 978-92-5-206006-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bompais, X.; Institut Français de Recherche Pour L’exploitation de la Mer. Les Filieres Pour L’elevage des Moules. Guide Pratique; IFREMER: Plouzané, France, 1991; p. 241. ISBN 2.905434-36-8. [Google Scholar]

- IFREMER. Moule. Aquaculture. Institut Français de Recherche Pour L’exploitation de la Mer (IFREMER). Available online: https://aquaculture.ifremer.fr/les-Filieres/Filiere-Mollusques/Decouverte-mollusques/Moule (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Badiola, M.; Basurko, O.C.; Piedrahita, R.; Hundley, P.; Mendiola, D. Energy use in Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS): A review. Aquac. Eng. 2018, 81, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.T.E.; Ko, H.; Huh, J.-H.; Park, N. Overview of Solar Energy for Aquaculture: The Potential and Future Trends. Energies 2021, 14, 6923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karathanasi, F.; Soukissian, T.; Belibassakis, K. Directional Extreme Value Models in Wave Energy Applications. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George Bouckaert Van. pyextremes: Extreme Value Analysis in Python 2023. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/pyextremes/ (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Wang, D.; Jin, S.; Hann, M.; Conley, D.; Collins, K.; Greaves, D. Power output estimation of a two-body hinged raft wave energy converter using HF radar measured representative sea states at Wave Hub in the UK. Renew. Energy 2023, 202, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- deCastro, M.; Lavidas, G.; Arguilé- Pérez, B.; Carracedo, P.; deCastro, N.G.; Costoya, X.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Evaluating the economic viability of near-future wave energy development along the Galician coast using LCoE analysis for multiple wave energy devices. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 463, 142740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2025/Jun/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2024 (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Batır, E.; Aydın, İ.; Theodorou, J.A.; Rakaj, A. Mytilus galloprovincialis’s role in Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA): A comprehensive review. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2025, 56, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Xu, P.; Huang, L.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Fazhan, H.; Kwan, K.Y. Effects of bivalve aquaculture on plankton and benthic community. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).