Abstract

As the global imperative to decarbonize infrastructure intensifies, wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are emerging as critical nodes for implementing circular and energy-positive solutions. Among these, thermal energy recovery from sewage sludge presents a transformative opportunity to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, enhance energy self-sufficiency, and valorize waste streams. While anaerobic digestion remains the dominant stabilization method in large-scale WWTPs, it often underutilizes the full energy potential of sludge. Recent advancements in thermal processing, including pyrolysis, gasification, hydrothermal carbonization, and incineration with energy recovery, offer innovative pathways for extracting energy in the form of biogas, bio-oil, syngas, and thermal heat, with minimal carbon footprint. This review explores the physicochemical variability of sewage sludge in relation to treatment processes, highlighting how these characteristics influence thermal conversion efficiency and emissions. It also compares conventional and emerging thermal technologies, emphasizing energy yield, scalability, environmental trade-offs, and integration with combined heat and power (CHP) systems. Furthermore, the paper identifies current research gaps and outlines future directions for optimizing sludge-to-energy systems as part of net-zero strategies in the water–energy nexus. This paper contributes to a paradigm shift toward sustainable, decarbonized wastewater management systems by reframing sewage sludge from a disposal challenge to a strategic energy resource.

1. Introduction

The decarbonization pathways for the water and wastewater sector, involving wastewater and sludge processing and the recovery of valuable raw materials and energy from them, depend on the nature of the disposal technology used and are therefore significantly complex. Therefore, at the current stage of development of processes aimed at decarbonizing the water and wastewater sector, there is a need to implement a range of solutions from other sectors of the economy, including the energy sector [1].

Sewage sludge is a valuable “raw material” for energy production and a biochemically stabilized product that can be used in agriculture, land reclamation, or construction in accordance with the principles of the circular economy. A concept consistent with sustainable development is the construction of biorefineries, which are a technologically and economically promising solution. However, they require optimization on a larger scale to obtain a product that maximizes the profitability of the installation [2,3,4].

Sewage treatment plants, like any other enterprise, generate waste in the form of sewage sludge. Sewage sludge undergoes a processing based on different technological processes, the nature of which depends on the type of sludge subjected to treatment. As a result, stabilized and dewatered sludge undergoes a potential management process. For many sewage treatment plants, sewage sludge is a significant problem, mainly due to high hydration and a serious sanitary hazard [5]. The complexity and time-consuming sludge processing means that meeting the requirements for sludge management requires large financial outlays exceeding 50% of all costs incurred by the treatment plant [6].

Sewage sludge, being waste, is a valuable source of energy. Depending on the sewage treated, treatment methods and unit processes used for its processing, sewage sludge is characterized by different physicochemical properties and structural features. The selection of sewage sludge conversion methods is based on its hydration, the expected type of energy, the applicable environmental conditions, and the financial outlays for both investment and operation of the installation [7]. According to literature data, the global production of excess sludge, characterized by a hydration of approximately 80%, will reach approximately 103 million tons by 2025 [8]. The variable chemical composition and properties of sewage sludge are the reason for implementing different technological solutions during its processing and disposal [9]. In the era of searching for waste-free technologies that do not pollute the natural environment, thermal waste processes are a promising ecological and economic solution [10].

Hydrogen is considered a key energy carrier of the future due to its unique properties. It is characterized by a high energy density of 122 kJ/g, about 2.75 times higher than hydrocarbon fuels. Its combustion does not cause harmful emissions—the only by-product is water. However, about 95% of hydrogen currently is produced from fossil fuels such as coal, natural gas, and crude oil, which poses a challenge for its ecological production [11,12].

Decarbonizing of the wastewater sector involves reducing greenhouse gas emissions by reducing energy consumption in treatment processes, increasing energy efficiency and using wastewater as a renewable energy source [13,14]. The introduction of thermal sewage sludge processing technologies allows for energy recovery from the organic matter contained in wastewater. Allows treatment plants to become positive energy facilities that meet their energy needs and supply surplus energy to the energy system, contributing to sustainable energy transformation [15,16,17,18]. Such solutions can reduce energy costs and emissions at the energy system scale. Obaideen et al. (2022) [17] concluded that wastewater treatment can play a significant role in achieving sustainable development goals.

Legal frameworks introduced by decision-makers should determine actions to increase energy efficiency, including innovative technologies and concepts aimed at significantly reducing energy consumption. Complete decarbonization of the wastewater sector should be based on accounting for electricity consumption, estimating N2O emissions and methane release, and emissions related to the use of chemicals and fuels necessary to transport sludge for storage outside the production unit. Utilizing the carbon and thermal energy resources contained in wastewater and sludge to offset fossil energy consumption in other sectors [19].

This review was prepared in a narrative-thematic format, whose structure was developed on a rigorous methodological approach, ensuring high transparency and insightful insights. The source analysis included peer-reviewed scientific articles and technical reports, in English and Polish. The selection of sources was selective and based on qualitative criteria. Publications focusing exclusively on types of sludge treatment other than thermal processing were excluded from further analysis, as were those duplicating previously identified data or failing to meet substantive requirements. Data were extracted from selected publications concerning the use and processing of sewage sludge in the context of energy and environmental solutions. The results were summarized in tabular form and then subjected to critical thematic analysis, which allowed for identifying dominant research trends, significant methodological limitations, and potential directions for future research. The literature selection process was multi-stage and included analysis of titles, abstracts, and full texts. Although this review was not formally registered (e.g., in databases such as PROSPERO). The search strategy was developed before the analysis began, documented internally, and consistently applied across all databases, ensuring consistency and transparency in the research process.

This article aims to review and analyze literature data on processes leading to the decarbonization of wastewater systems, including the recovery of thermal energy from sewage sludge. The assessed thermal sludge methods and processes provide a renewable energy source as an alternative to fossil fuels, while ensuring energy independence.

2. Sustainable Development

Implementing thermal treatment of sewage sludge aligns with the principle of sustainable development. In recent years, the imperative to implement sustainable economic development that supports environmental integrity and ensures intergenerational equity has gained substantial attention [20,21].

Meeting the challenges facing the biofuels market in Poland, aimed at reducing the carbon footprint and broadly understood environmental protection, requires appropriate legislative changes while simultaneously raising public awareness of the potential for widespread use of biofuels and biocomponents. Achieving a 14% share of renewable energy sources in transport by the end of 2030 requires implementing solutions implemented in Europe and globally, such as maximizing the blending of biocomponents in standard fuels and using biocomponents in accordance with quality standards.

Sustainable sewage sludge management is currently essential to address the challenges of a circular economy, the “zero waste” concept, and sustainable development. Sewage sludge is a valuable waste product whose multifaceted use is a crucial element of the bioeconomy due to its valuable energy and raw material properties.

Based on Annex IX of the RED II Directive (Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council, 2018) [22], sewage sludge can be included as a feedstock for the production of biogas for transport and advanced biofuels. The share of this biogas in the final energy consumption in the transport sector (hereinafter referred to as the “minimum share”) referred to in Article 25 (1), first and fourth subparagraphs of the Directive, can be considered equivalent to twice its energy content. The Directive also assumes that by 2030, the total greenhouse gas reduction in the domestic road and rail transport sector will be at least 13%.

Furthermore, pursuant to Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/996 of 14 June 2022, entities covered by the EU ETS are required to demonstrate sustainability criteria and reduce greenhouse gas emissions for biomass [23]. As defined in the Regulation (Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/996 of 14 June 2022), “sustainability and greenhouse gas emissions saving properties” means a set of information describing a batch of raw material or fuel required to demonstrate compliance of the batch with the sustainability and greenhouse gas emissions saving criteria for biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels or with the greenhouse gas emissions-saving requirements applicable to renewable liquid and gaseous transport fuels of non-biological origin and recycled carbon fuels.

The European Commission’s Communication “The European Green Deal” of 11 December 2019, highlights the European Commission’s commitment to addressing climate and environmental challenges. According to the Communication, the goal of the adopted strategy is to “transform the EU into a fair and prosperous society with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy that achieves net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and decouples economic growth from the use of natural resources” [24].

In accordance with the RED II Directive and the provisions of Article 29, paragraphs 2–7 and 10, energy from biofuels, bioliquids and biomass fuels is considered to meet the obligation of the percentage share of renewable energy in the final energy consumption in the energy sector thus, energy production is eligible for financial support in the case of implementation of the so-called sustainable development criterion (SDC) and the criterion of reducing greenhouse gas emissions [23,25].

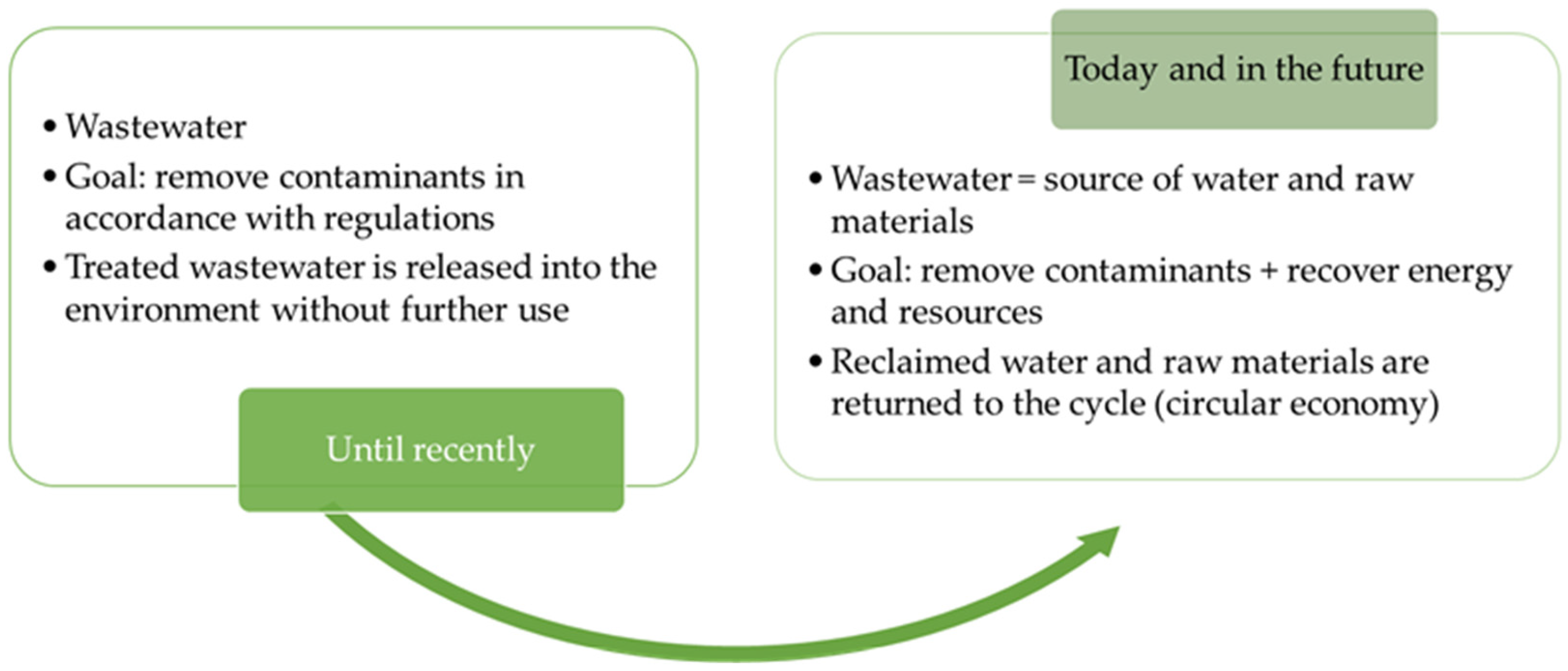

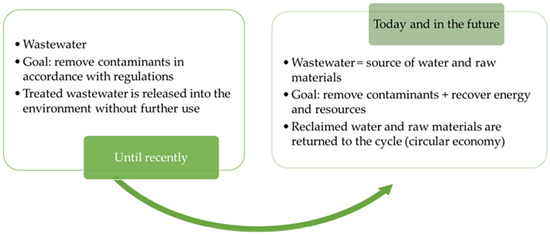

Demographic changes, growing environmental pollution and the resulting climate change, and the need for sustainable water and wastewater management development were the basis for the formulation of the Nutrient-Energy-Water (NEW) Paradigm. This paradigm, introduced in 2012 and initiated by the United States, applies to the water and wastewater sector and is now becoming a guide for the operation of modern wastewater treatment plants, especially in the aspect of using sewage sludge as a renewable energy source. The principles of a circular economy can be successfully implemented in wastewater treatment plants through the intensification of energy production and optimization of its consumption, as well as the recovery or production of wastewater and sludge, which are important raw materials for the economy and the environment [26,27]. Figure 1 compares of the principles of operation of the treatment plant according to the old and new paradigms, emphasising the possibility of energy recovery [28].

Figure 1.

Comparison of the old and new wastewater treatment paradigms.

The English-language concept of “4R-reduce-reuse-recycle-recovery” reflects the aspirations for rational management of raw materials, products, resources, as well as sustainable use of waste in a circular economy, through minimization, reuse, recycling and recovery [29,30]. These assumptions can be met by wastewater treatment plants based on modern, energy-efficient technologies, which, while fulfilling their priority role of adequate wastewater treatment, also utilize technologies aimed at maximum resource and energy recovery.

It should be noted, however, that most production processes and energy production currently rely on conventional materials (fossil fuels). Therefore, it is advisable to undertake and continue existing efforts aimed at the widespread introduction of renewable raw materials into the economy and the diversification of energy sources, with particular emphasis on green energy.

Wastewater, and as a result, sewage sludge from its treatment, are not only major consumers of energy, materials, and chemicals, but also significant emitters of greenhouse gases, mainly methane. There is a need to develop dedicated solutions specifically for the water and wastewater sector, aligned with sustainable development goals, i.e., zero-emission solutions, the ultimate result of which will be water recovery and highly advanced wastewater treatment, which directly determine the effective decarbonization of this sector.

3. Characteristics of Sewage Sludge

Sewage sludge is an organic-mineral solid phase, isolated from sewage [31]. Sludge production increases with the use of highly effective methods of biological and chemical sewage treatment. Primary sludge is produced in the sedimentation process, and the solid fraction is separated from wastewater at the first stage of mechanical treatment in primary settling tanks. Excess sludge is activated sludge consisting of a biomass of bacteria and protozoa, produced during biological wastewater treatment, returned to biological reactors or disposed of. The amount of raw sludge (primary and excess) generated in municipal sewage treatment plants depends on the composition of sewage and the technology used for its treatment [32,33,34]. The size of the treatment plant and its location are also important factors [35].

Depending on the type of sewage treatment plant, municipal and industrial sludge can be distinguished, such as [36,37]:

- primary sludge—these are sludge separated in primary settling tanks in the process of mechanical sewage treatment. They contain organic solids of a greasy consistency. The water content in primary sludge reaches 93–97%;

- secondary sludge—these are sludge generated in biological sewage treatment processes, separated in secondary settling tanks. Secondary sludge is divided into recirculated (returned to the treatment cycle) and excess (removed from the cycle). A homogeneous, flocculated structure characterizes them;

- chemical precipitation sludge—formed as a result of the chemical precipitation of pollutants, e.g., phosphorus compounds. They are formed in different places in the technological chain, which is related to the place of application of chemicals;

- mixed sludge—formed after mixing primary and secondary sludge.

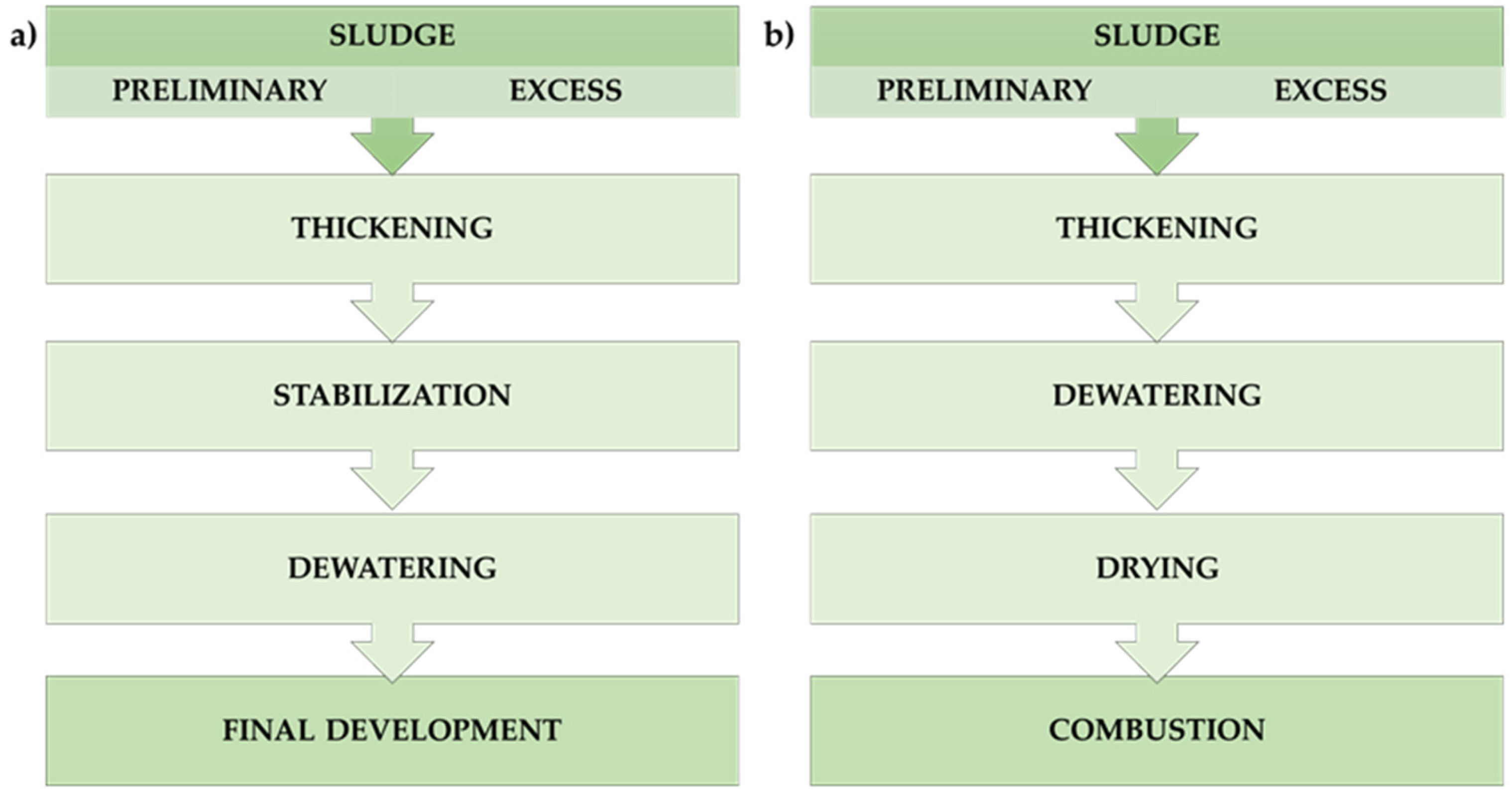

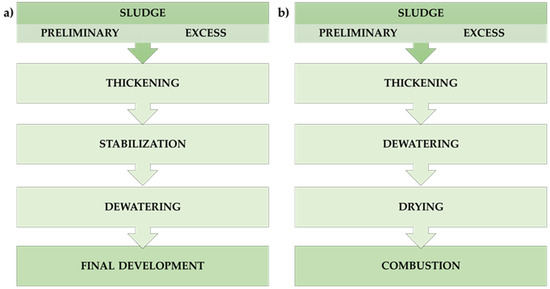

A sample diagram of sludge processing technology in sewage treatment plants is shown in Figure 2a. In recent years, attention has been paid to thermal sludge processing methods. The diagram of technology using these processes is shown in Figure 2b [23]. The above methods consist of successive stages of removing water from sludge, which is associated with high implementation costs.

Figure 2.

Technology of sewage sludge processing using (a) the stabilization process, and (b) thermal processes.

The characteristics of sewage sludge are determined by the content of organic and mineral substances in dry mass, hydration and technological features, which are derived from the chemical composition of the sludge—calorific value, dewatering ability, rheological properties. The above parameters determine the susceptibility of sludge to thermal conversion by determining the potential carbon content and susceptibility to water addition. Sludge can be characterized by appearance, smell or color. For example, raw sludge from municipal sewage is grey or yellowish, has a foul odor and is difficult to dewater. Fermented sludge is black and has a tarry smell. In turn, sludge after oxygen stabilization is characterized by a brown color and a soil smell [38].

Characteristic features of sewage sludge are [39,40]:

- high hydration, approx. 99% in the case of excess sludge and 96–98% for primary sludge;

- high (approx. 75%) content of organic compounds susceptible to biological decomposition;

- high content of nitrogen compounds (2–7% TS);

- varied content of heavy metals;

- generally low content of organic hazardous substances (PAHs, chlorinated compounds—PCBs);

- varied degree of sanitary hazard, the highest for primary raw sludge, the lowest for stabilized and hygienized sludge.

The susceptibility of sludge to the process of biochemical decomposition can be estimated based on the BOD5/COD quotient and BOD5/TS. It was found that with decreasing values of the BOD5/COD quotient and BOD5/TS, the susceptibility of sludge to biodegradation decreases [41].

The amount of excess sludge produced depends on the age of the activated sludge, as well as on the ratio of the concentration of total suspended solids TSS to BOD5 in sewage flowing into the biological treatment stage. Excess sludge is activated sludge separated in secondary settling tanks, i.e., clusters of microorganisms bound in flocs. Living organisms, dead organisms, and spore forms form them. Excess sludge is characterized by high hydration, reaching about 98%, as well as a significant content (at the level of 65–75%) of dry organic matter [36]. The amount of sludge in sewage treatment plants is usually determined based on the results of measuring equipment. The exact amount should be determined based on the sludge balance in a specific treatment plant.

Sewage sludge also contains heavy metals, synthetic organic substances, pathogenic organisms, significant amounts of bacteria, viruses, protozoa, and helminth eggs. Phenols, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), organochlorine pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dioxins and furans, and other persistent toxic organic compounds present in sewage sludge can pose a threat to the environment, as well as the health and life of higher organisms. Contaminants introduced with sludge can be released during sludge storage and leaching by rainwater. The main source of PAHs in sludge is industrial wastewater, with less domestic sewage. The diversity of chemical composition and distinct properties of sewage sludge necessitate using different technological solutions during sewage sludge disposal and processing. Given that sewage sludge is characterized by a high degree of hydration, it is first subjected to a thickening process. Primary sludge is most often subjected to gravity thickening, while the mixture of primary and excess sludge is thickened using mechanical or flotation thickeners. Good results are achieved using mechanical devices assisted by flocculation using polyelectrolytes for the thickening of excess sludge. Stabilization processes are applied to sludge with a high content of easily degradable organic substances, while mineral sludge can be neutralized, among other methods, by dewatering [7,42].

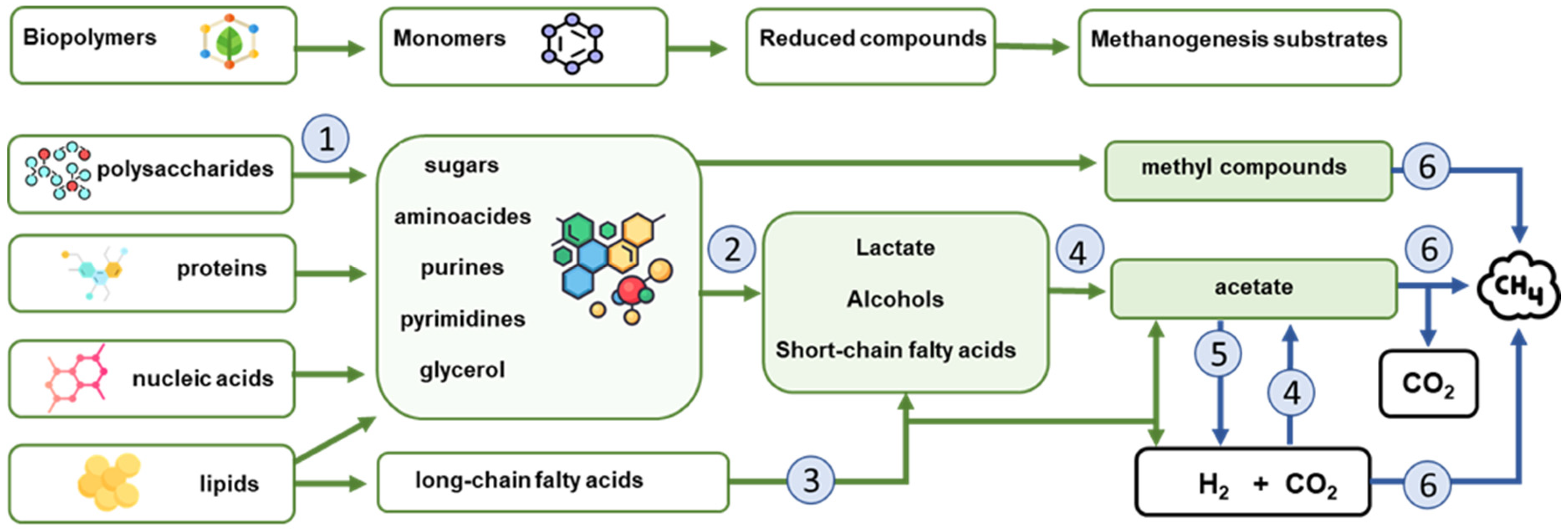

4. Characteristics of Selected Technologies for Thermal Treatment of Sewage Sludge

4.1. Anaerobic Stabilization of Sewage Sludge

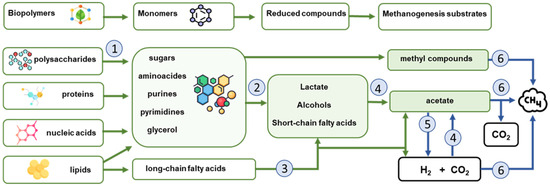

During methane fermentation, more than 50% of the reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD) and methane production occurs due to fat decomposition. The decomposition rate of most components of the fat fraction can be used to determine the residence time of sludge in the fermentation chamber [43]. Initially, some scientists considered methanogenesis the rate-limiting phase of the entire process of anaerobic stabilization. However, current studies’ results indicate that the anaerobic process’s transformation rate depends on the stabilized substrate type and availability [44]. According to Zawieja (2024) [7], increasing the availability of organic substances subject to biochemical decomposition is a factor influencing the efficiency of anaerobic stabilization. According to Neczaj and Bohdziewicz (2003) [45], Eastman and Ferguson (1981) [46], the decomposition rate of organic compounds in fermentation chambers results from partial reactions of transformations occurring in the individual phases of the process. According to the acid phase model given by Eastman and Ferguson (1981) [46], hydrolysis of solids to dissolved substrates is a process that limits the rate of decomposition of organic substances to fatty acids. Bacteria use hydrolysis products in subsequent stages of fermentation. With the increase in the concentration of dissolved organic compounds in the sludge, the susceptibility to biodegradation of organic matter increases. According to Zawieja et al. (2017) [47], the more advanced the decomposition of organic substances, the greater the number of fine particles in the sludge. Research was conducted on the hydrolysis phase as the rate-limiting phase of biochemical decomposition of organic substances [48,49,50,51,52,53]. As reported by Kim et al. (2003) [54], the main by-product of biological wastewater treatment is excess sludge, the amount of which is still growing due to the expansion of sewage. The introduction of regulations concerning the necessity of removing biogenic compounds from sewage required modification of the sewage treatment process using the activated sludge method. New technological parameters of the sewage treatment process mean that already during nitrogen removal in the activated sludge chambers, partial oxygen stabilization of sludge occurs, leading to a reduction in excess easily decomposable substances in the sludge, which significantly reduces the BOD5/COD and BOD5/TS ratios. It was found that with a decrease in the BOD5/COD and BOD5/TS ratios, the susceptibility of sludge to biodegradation decreases [55]. An increase in the concentration of dissolved organic substances means greater availability for microorganisms responsible for the biochemical decomposition of organic compounds, resulting in a shorter time for subsequent phases of the fermentation process. It should be noted, however, that the course of the methane stabilization process is also conditioned by the presence of compounds inhibiting the process, such as heavy metals, oxygen, ammonia, and hydrogen sulphide. The acceleration of the acetogenic phase (which can be evidenced by the shorter time needed to obtain a significant increase in the concentration of volatile fatty acids) is accompanied by a significant increase in the effect of obtaining products of this phase, i.e., short-chain carboxylic acids, called volatile fatty acids (VFA) [56]. These acids are one of the intermediate products of anaerobic decomposition of organic substances, and the acetic acid present in their composition is the primary, easily assimilable source of organic carbon for many anaerobic and facultative microorganisms [57]. A good indicator of the proper course of the fermentation process is the value of the ratio of volatile acids to alkalinity [58]. The alarming level is the ratio value of 0.3—its increase means disturbances during the process. The increase in this ratio precedes a rapid decrease in pH over time [32]. Figure 3 shows the phases of the anaerobic stabilization process, considering the changes occurring at each stage. Table 1 presents a summary of conventionally used process conditions for anaerobic stabilization.

Figure 3.

The course of stabilization of anaerobic organic matter with consideration of the stages occurring in the absence of inorganic electron acceptors other than H2 and CO2: (1) depolymerization-hydrolysis, (2) acidogenesis, (3) ẞ-oxidation, (4) acetogenesis, (5) acetate oxidation, (6) methanogenesis [59,60].

Table 1.

Mesophilic vs. thermophilic fermentation conditions [61].

The main product of methane fermentation is biogas, a gas mixture consisting primarily of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2). It also contains trace amounts of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H2), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), oxygen (O2), nitrogen (N2), and ammonia (NH3) [62]. Methane is a gas commonly found in nature. Methane is produced as a result of fermentation involving microorganisms, mainly in the process of reducing carbon dioxide with hydrogen.

and from the metabolic breakdown of acetic acid:

CO2 + 4H2 = CH4 + 2H2O,

CH3COOH = CH4 + CO2 + energy,

Carbon dioxide and water are produced during methane combustion. This reaction is highly exothermic; therefore, methane mixed with air in a ratio of 5–15:100 creates a dangerous explosive mixture (the lower explosive limit is 5, and the upper explosive limit is 15). During combustion, 1 m3 of methane produces approximately 1.6 kg of water in the form of steam. Combusting 1 m3 of methane requires approximately 10 m3 of air [63]. The heat of combustion of methane is 55.53 MJ/t, and its calorific value is 50.05 MJ/t. According to Skorek-Osikowska (2020) [64], biogas’s calorific value is 18–24 MJ/m3. From anaerobic decomposition, it is theoretically possible to obtain [65]:

- from 1 kg of carbohydrates—453 dm3 CH4 + 456 dm3 CO2;

- from 1 kg of protein—547 dm3 CH4 + 516 dm3 CO2;

- from 1 kg of lipids—1095 dm3 CH4 + 449 dm3 CO2.

Despite some common properties with natural gas, injecting biomethane into the gas grid requires adapting its properties. This is due to significant differences between these potentially high-energy gases.

Biogas, characterized by a high methane content (40–70%), produced during the biological conversion of biomass, is a particularly attractive energy source for cogeneration systems (CHP—Combined Heat and Power), i.e., the simultaneous production of electricity and heat [66]. Combustion of biogas produces fewer harmful nitrogen oxides than combustion of fossil fuels. Another important benefit is the reduction of carbon dioxide and methane emissions into the atmosphere, which in turn contributes to reducing the greenhouse effect.

Considering methane’s energy properties, the share of biomethane and biogas in the European Union’s total energy mix should be approximately 32%, significantly reducing the energy sector’s dependence on natural gas and fossil fuels. Based on this assumption, biogas plants have an electricity production capacity of up to 9985 GW, with an annual production of approximately 48–50 billion Nm3 of biomethane [67,68].

It should be noted that the implementation of co-fermentation technology based on the stabilization of two different substrate streams in a series of large wastewater treatment plants would enable the increase in decarbonization of wastewater treatment by increasing the efficiency of biogas production, increasing the buffering capacity of the co-fermentate mixture, diluting toxic substances such as heavy metals and other compounds inhibiting the process [69].

4.2. Combustion

Sewage sludge incineration involves thermal oxidation in the presence of oxygen at high temperatures [70,71,72]. This process leads to the complete oxidation of organic matter, the reduction in pathogens, and a drastic reduction in the weight and volume of the sludge. The heat obtained is used to generate steam, which is then used to produce electricity or for heating purposes (cogeneration). A sludge incinerator usually involves the following stages:

- preliminary drying of the sludge (to reduce the water content to <50%);

- combustion of gases and slag in the combustion chamber;

- cooling and cleaning of exhaust gases.

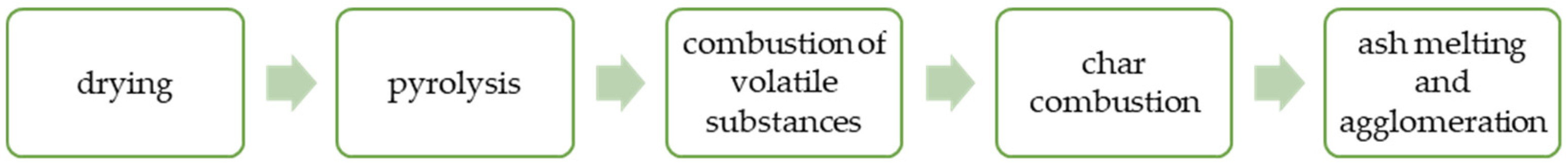

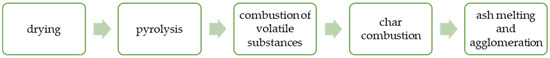

The combustion of sewage sludge is a complex physicochemical process. The pro-cess is carried out in stages, with each phase following the previous one. This depends on the conditions in the reactor and the properties of the fuel itself. The general principle of solid fuel combustion is described in the diagram below (Figure 4) [70,73,74].

Figure 4.

The key stages of the combustion system.

The main problem in the combustion process of sewage sludge is its high moisture and ash content, which significantly affects the thermal characteristics of the fuel and determines the design requirements of combustion chambers. Excessive moisture reduces the calorific value of the sludge, limits the bulk density of the fuel, and promotes incomplete oxidation. Furthermore, it requires increased energy input and oxidants necessary for drying. High moisture also promotes the formation of erosive sulfur compounds, which can negatively impact combustion system components [75].

Various combustion reactors, such as multi-hearth, rotary, and fluidized bed, have different fuel feeding modes, operating modes, and advantages and disadvantages [76]. A comparison of the process conditions of sludge combustion technologies is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of selected parameters for the sewage sludge combustion process.

In practice, circulating fluidized bed (CFB) furnaces and multi-stage furnaces (MHF) are primarily used [80]. Circulating fluidized bed furnaces have gained popularity, especially for wet sludge (35–59% moisture content), thanks to their simpler design and uniform temperature distribution in the chamber. They ensure high combustion efficiency with relatively low CO and NOx emissions (CO and NOx content in flue gas <50% compared to traditional technologies). Multi-stage furnaces were once dominant (in the US, ~80% of installations). However, modern installations increasingly choose fluidized bed technology due to better sludge mixing and easier process control [70].

The combustion temperature is maintained at 850–900 °C, guaranteeing complete combustion of organic substances. The supply of excess air (or pure oxygen) ensures complete decomposition of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur from the sludge; the resulting gases (mainly CO2, H2O, NOx, SO2) are passed through a heat recovery system (heat/steam exchanger) and advanced purification systems (bag filter, desulfurization, denitrification, metal chemisorption) [70]. The incineration of sewage sludge enables the recovery of energy contained in organic matter. Despite high moisture content, sewage sludge has a moderate calorific value (approx. 16–16.8 MJ/kg dry matter), which means it can be used as an energy source in thermal conversion processes [81]. This means that, after drying, it can be used as a fuel similar to biomass. In practice, part of the heat generated is used to dry the sludge or power the dryer. The excess energy can be converted into electricity (typically, the electrical efficiency of a CFB installation with heat recovery is several to several dozen percent, and together with heat, it is possible to cover a significant part of the plant’s demand). The combustion technology is characterized by a significant reduction in the weight and volume of sludge (sludge incinerators reduce its volume by up to 90%), translating into a reduction in the amount of waste disposed of. In addition, mineral ash from sludge contains concentrated phosphorus, which, after appropriate treatment, can be recovered as fertilizer, although this requires control of phosphate release (risk of eutrophication) [70].

From an economic point of view, however, sludge incineration plants are characterized by high investment and operating costs. A sludge dewatering station and an extensive exhaust gas treatment system (NOx and SOx reduction systems, desulfurization and denitrification installations, filters, and toxic substance treatment devices) are necessary. The high moisture content and low calorific value of sludge increase the demand for auxiliary fuels (gas, oil) during combustion’s start-up and stabilization phases. Nevertheless, energy recovery can partially offset the costs (e.g., by selling heat or electricity). The specific cost of thermal conversion of 1 ton of dry sludge using combustion technology is in the medium range (according to older sources, several hundred euros per ton of dry matter) (approximate value based on national data and EU reports) [82]. Another advantage is independence from weather conditions and constant availability of the process regardless of seasonality, which contrasts with biogas plants.

During combustion, gaseous pollutants such as nitrogen, chlorine, sulfur, dioxins, furans, and other compounds in sewage sludge are released. Therefore, thorough flue gas treatment is necessary to meet the strict emission limits typically imposed on waste incineration processes [76]. Intensive exhaust gas cleaning enables compliance with strict standards: for example, in the EU, the maximum concentration of dioxins and furans in incinerator exhaust gases is limited to 0.1 ng I-TEQ/m3 (1 × 10−13 kg I-TEQ/m3 in accordance with the SI system (mass/volume)), and detailed permissible levels of NOx, SOx, dust, and heavy metals are regulated by the IED Directive (2010/75/EC) [83]. It is important that ‘I-TEQ’ is not a physical unit, but a conventional toxicity value based on TEF (Toxic Equiva-lency Factors) coefficients—therefore, it has no SI equivalent. According to the SI system, only the mass-to-volume ratio of the tested samples of exhaust emissions from the waste incinerator was recorded. In practice, bag filters, chemical absorbers (NaOH, lime), and other emission reduction installations are necessary. Residuals are also removed from combustion systems: fly ash and bottom ash must be disposed of (e.g., deposited in special landfills or recovered). In general, this process releases waste components of the deposits into the atmosphere; therefore, environmental safety depends on the effectiveness of flue gas cleaning.

Sludge incineration enables effective disinfection (destruction of pathogens and organic contaminants) and a significant reduction in waste volume (an incinerator can reduce sludge volume by up to ~90%). A heat obtained improves the energy balance of the treatment plant, and the mineral residues (ashes) can be useful, especially as a source of phosphorus. Since incineration completely destroys organic materials, the sludge is de facto sterile and stable, facilitating the transport and storage of residues [84]. Modern incineration plants also have very high furnace energy efficiency and heat recovery [85].

Unfortunately, the main disadvantages are high investment, operating costs, and pollutant emissions. A sludge dryer is required—high moisture content reduces the calorific value and hinders combustion. In addition, the exhaust gases contain toxic components: nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, dust, heavy metals (e.g., Hg, Cd, Pb), and organic compounds (dioxins, furans, phenols) [86]. Multi-stage exhaust gas treatment is necessary to meet strict environmental standards. The risk of undesirable phenomena (e.g., slagging or sintering of chloride-containing ash) requires adequate process control. Ash disposal is also a problem—ash can be reused (e.g., in cement or as fertilizer), but its contamination with metals or toxins limits these possibilities.

For sewage sludge incineration plants, the typical net electrical efficiency is around 20–28%, while thanks to heat recovery, the total CHP efficiency reaches 80–85% of the lower heating value (LHV). Burning one ton of dry sludge mass can produce approximately 0.5–0.7 MWh of electricity and an additional 1.5–2 MWh of heat (e.g., for the district heating network or the treatment plant/incinerator’s needs). These are theoretical data compiled based on the Implementing Decision 2019/2010, establishing the best available techniques (BAT) conclusions under Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and the Council regarding waste incineration. According to an industry report, constructing a WtE plant with an annual capacity of 40,000 tons of sludge costs approximately $41 million. Annual operating costs (OPEX) are typically 5–7% of CAPEX [31].

However, treating sewage sludge as a resource—a potential source of fuels, fertilizers, and CO2 that can be utilized in various processes. Therefore, to reduce CO2 emissions during the sewage sludge incineration process, the application of CO2 capture technology has been proposed [87].

4.3. Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis is considered an effective method of processing sewage sludge, as it converts sludge into bio-oil, bio-char, and syngas (containing hydrogen and carbon monoxide, among others), while reducing the emission of pollutants. This process occurs in an inert atmosphere, at low or medium temperatures. Pyrolysis consists of the thermal decomposition of sewage sludge at temperatures ranging from 400 to 600 °C, using inert gases such as nitrogen (N2) or carbon dioxide (CO2), which allows obtaining the desired end products [88,89]. Examples of sewage sludge pyrolysis conditions are presented in Table 3.

Thermal analysis of the dried sewage sludge shows that three main mass loss stages occur during heating at different temperature ranges. The first stage is an endothermic reaction, in which the absorbed water evaporates, causing a mass loss of 5–10% at 180–200 °C. Followed by an exothermic reaction, leading to a maximum mass loss of 40% to 70%, due to the decomposition of volatile compounds. The last stage is a further endothermic reaction, in which the organic and inorganic contents decompose at 300–700 °C, causing an additional mass loss of 9–40% [90].

Table 3.

Summary of selected parameters for the sewage sludge pyrolysis process.

Table 3.

Summary of selected parameters for the sewage sludge pyrolysis process.

| Pyrolysis | Batch | Temperature | Reactor | Syngas Heating Value | Liter. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flash pyrolysis | thickened excess activated sludge | 500 °C | semi-continuous lab scale reactor | 15.7 MJ/kg | [91] |

| Inert gas—nitrogen | Sewage sludge + Rice husk | 900 °C | vacuum fixed bed reactor | 3.30 MJ/m3 | [92] |

| Slow pyrolysis | biosolids | 300–800 °C | batch pyrolysis—stainless steel | 14% | [93] |

| Slow pyrolysis | Sewage sludge | 450 °C | auger type reactor | 32.3 MJ/kg | [94] |

| High temperature pyrolysis | domestic sewage | 450 °C, 600 °C, 850 °C | electrically heated rotary kiln pyrolysis system | 19.598 kJ/m3 18.054 kJ/m3 17.422 kJ/m3 | [95] |

Hydrogen produced in the pyrolysis process is one of the principal gaseous components, reaching a concentration of 30–36.04% by volume. The sewage sludge pyrolysis process proceeds according to the following equation [96]:

SS → CO(g) + H2(g) + CO2(g) + CnHm(g)+ Tar(l) + char

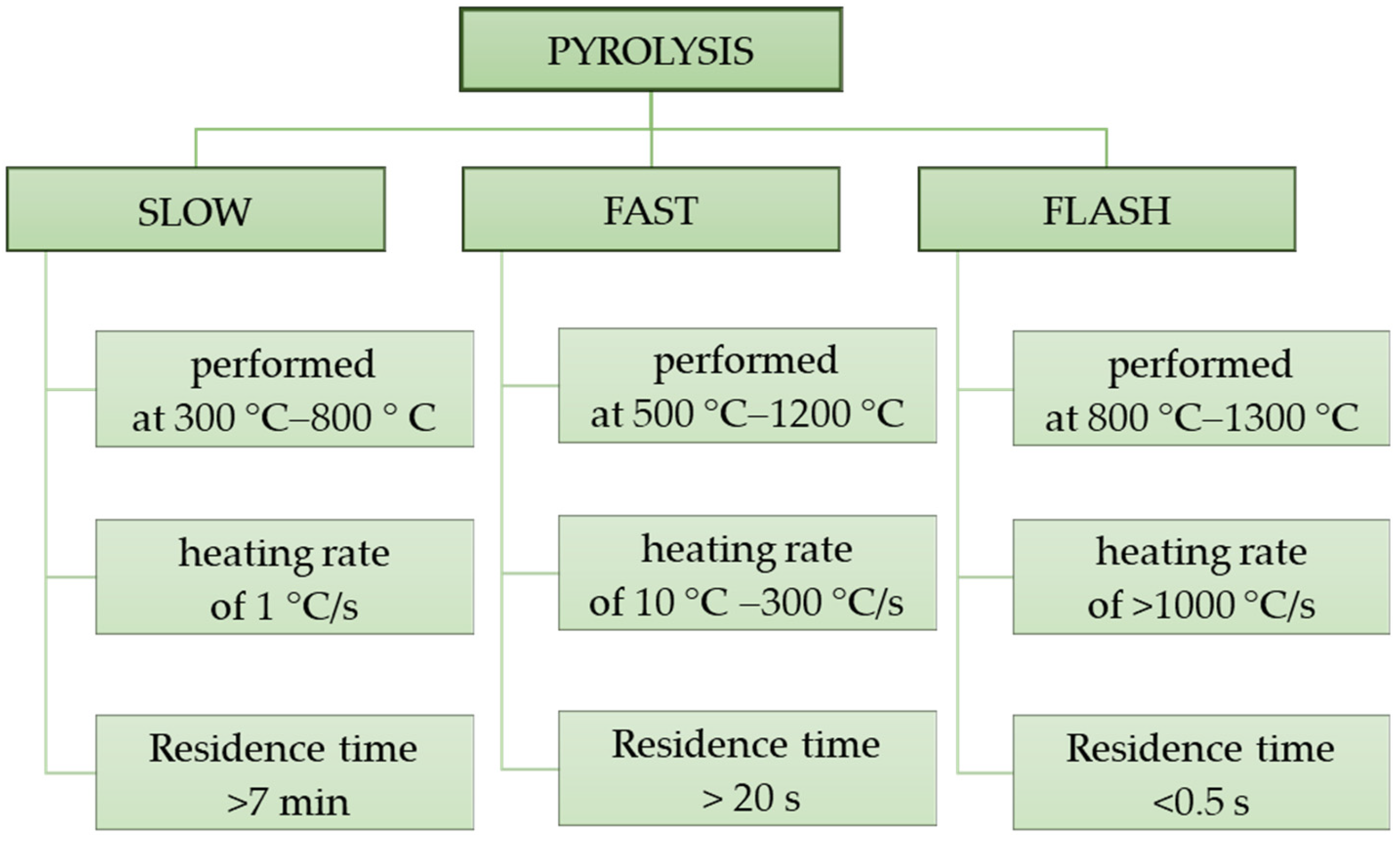

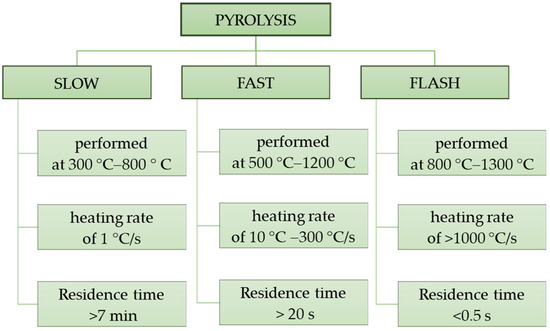

Pyrolysis processes that recover energy from sewage sludge can be divided into slow, fast, and flash pyrolysis. Pyrolysis is considered an environmentally friendly technology, as it contributes to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and concentrates heavy metals in the solid residue. In the case of sewage sludge, the pyrolysis process can be implemented in three variants (Figure 5) [97,98,99].

Figure 5.

Types of pyrolysis used to process sewage sludge.

A slow heating rate and a long residence time of the material in the reactor characterize slow pyrolysis. This process is most often used to produce biochar or activated carbon. On the other hand, rapid pyrolysis occurs at a high heating rate and higher temperature, resulting in the dominant products being bio-oil and pyrolysis gas. In flash pyrolysis, the main component is the liquid phase, i.e., bio-oil. The type and composition of the end products obtained from sewage sludge pyrolysis depend primarily on the process parameters, particularly the temperature and heating rate [89,97,100].

Analysing the effect of temperature on the pyrolysis process of sewage sludge, three main reaction zones were distinguished: below 200 °C, in the range of 200–600 °C, and above 600 °C. In the first zone, the dominant processes are the evaporation of water remaining after drying and the breakdown of bonds in hydrated compounds. The second zone encompasses the main pyrolysis reactions. In 201–380 °C, biodegradable substances depolymerize, while at temperatures of 380–550 °C, secondary decomposition of primary degradation products and poorly biodegradable compounds occurs. In the third zone, mainly inorganic materials decompose at temperatures above 600 °C, forming ash and carbon residues [101].

It should be emphasized that the products of the pyrolysis process (biochar, bio-oil, syngas) have the potential to generate heat and electricity. Additionally, bio-oil can be used to produce transportation fuels [102], while biochar can be used as an adsorbent or to improve soil quality [103]. However, it should be emphasized that bio-oil obtained from sewage sludge cannot be used directly as fuel, as it requires a refining process to improve its physicochemical properties. Requires implementing appropriate modernization processes to improve the bio-oil’s parameters to levels typical of motor fuels such as gasoline or diesel [102].

Efforts to decarbonize thermal sewage sludge management processes, focusing on energy recovery, stem from the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions generated in wastewater management. Using processes such as pyrolysis reduces the carbon footprint associated with sludge management. It recovers energy that can replace fossil fuel consumption and support the transition to a low-emission economy [104].

Integrating anaerobic digestion and pyrolysis enables efficient use of resources—pyrolysis of processed residues not only reduces waste management costs but also enables their optimal use in producing bioenergy and bioproducts [105].

4.4. Gasification

Thermochemical technologies provide an effective solution for sewage sludge management, enabling energy and resource recovery, significant volume reduction, and effective elimination of pathogens [106,107].

The primary purpose of gasification is to produce syngas, which can be directly used for heating or further converted into methanol, dimethyl ether, and other chemical compounds using the Fischer–Tropsch method [108]. The calorific value of syngas is low compared to other types of fuel, and it must be cleaned and compressed to be used in gas turbines and gas engines [109]. It also powers combustion engines to produce combined heat and power [110].

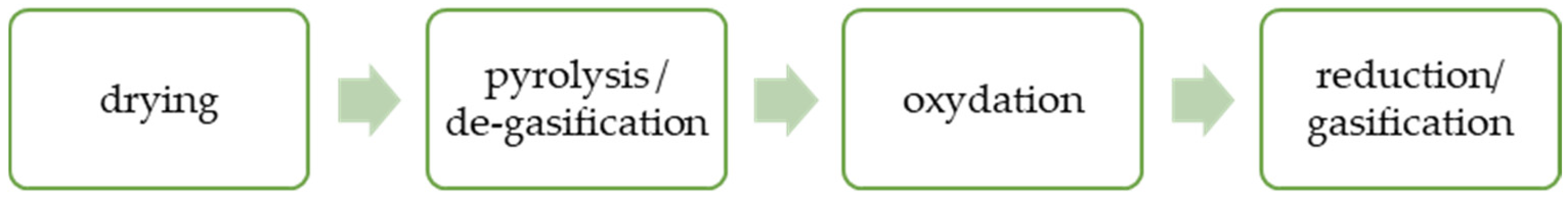

When heated, the sludge first undergoes a drying process and then pyrolysis (degassing), whereby volatile substances are released and the solid residue becomes carbon. In the gasifier, further reactions occur between the gaseous and gas–solid phases involving the gasifying agent and the products of drying, pyrolysis, and cracking, resulting in a high yield of combustible light gases. Gasification is therefore an extension of the pyrolysis process. It most commonly uses air as the gasification agent. However, the literature has also described using of steam air/steam mixtures, steam with CO2, steam with O2, and CO2 [111,112,113] alone as a gasification medium for sewage sludge. Table 4 presents example conditions for the sewage sludge gasification process.

Table 4.

Summary of selected parameters for the sewage sludge gasification process.

Gasification is a well-known thermochemical method used to produce synthesis gas. This gas consists primarily of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, but may also contain carbon dioxide, methane, tar, water, and other light hydrocarbons [123].

The gasification system consists of four main stages, which are shown in Figure 6. In the drying zone (70–200 °C), the sludge loses moisture through evaporation. This process’s rate depends on the feedstock’s surface area, the drying gas’s relative humidity, the sludge’s internal moisture diffusivity, and the temperature difference between the feedstock and the hot gases. Wastewater with less than 15% moisture dries completely in this zone. The pyrolysis zone is responsible for the thermal degradation of sewage sludge in the temperature range of 350–600 °C. At the same time, the thermal decomposition of dried sewage sludge occurs in this zone. The carbon remaining after this process is oxidised in the next zone, leading to a rapid rise in temperature to around 1100 °C. The heat generated by the exothermic reactions drives the drying, pyrolysis, and coal gasification processes. In the reduction (gasification) zone, coal is converted into a gaseous mixture, mainly carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen (H2), known as syngas. This process occurs by partial oxidation, Boudouard reaction, steam gasification, and hydrogasification. Homogeneous formation of gas phases also occurs, affecting the gas composition produced [106,107,123].

Figure 6.

The key stages of the gasification system.

Equation (4) shows the basic gasification reaction [124]:

SS → CO(g) + H2(g) + CO2(g) + CH4(g)+ Tar(l) + H2O(l)+ H2S(g)+ NH3(g)+ C(s) + trace species

The steam gasification is an alternative to traditional sludge treatment methods, which convert sewage sludge into valuable fuels. It is a highly efficient energy conversion method in which most organic fractions are converted into gaseous fuels through thermochemical reactions [114]. Steam gasification improves syngas quality compared to conventional air gasification by eliminating the dilution caused by nitrogen. High-temperature steam gasification of sewage sludge was investigated to obtain valuable syngas. The focus was on the chemical kinetics of syngas generation and feedstock decomposition in the batch process. The rates of syngas production and concentrations of syngas components were measured. After analysis of the results, it was concluded that the chemical reaction rate can be controlled and thus optimal operating conditions can be achieved. Could reduce processing time and steam consumption while maximizing the syngas yield [114].

In order to obtain better quality synthesis gas, research is also being carried out on co-gasification and catalytic gasification of sewage sludge. In situ steam co-gasification of wet sewage sludge with pine sawdust, which was added to reduce moisture and improve the volatile content, was investigated. Automatically generated steam from wet sewage sludge promoted the syngas production, and using NiO/MD catalyst reduced the amount of tar and significantly increased the dry gas yield. When using the optimum content of pine sawdust and a temperature of 900 °C with a tar yield of 2.19 wt.%, dry gas yields of 1.23 Nm3 /kg and H2 yields of 14.44 mol/kg were obtained [115]. Co-gasification of sewage sludge with wood, using a sorbent for in situ CO2 sorption, allows for a significant increase in the hydrogen content in the resulting gas. In order to analyze this process, the authors developed an equilibrium model, taking into account wood and sewage sludge as model compounds and calcium oxide (CaO) as the sorbent. The influence of reactor temperature ranging from 600 to 900 °C and sludge content in the feed from 0 to 100 wt.% at 700 °C on the efficiency and composition of syngas was assessed. The highest gas efficiency of 0.526 kg/h was achieved at 30 wt.% sludge at 900 °C, while the lowest CO2 content was observed at 700 °C [124]. Also, steam co-gasification of sewage sludge and horticultural waste was studied using different mass ratios at different temperatures. The research showed that the syngas yield increased with the increase in temperature and the ratio of horticultural waste in the mixtures. During the co-gasification process, there was a synergistic interaction at higher temperature due to the catalytic effect of Na and the steam reduction and oxidation of Fe compounds, which affected the syngas yield and H2 production [118]. The research was carried out on a fluidized bed by gasifying sewage sludge, where the gasification agent was air and steam, with air; the process was carried out at a temperature of 750 °C. It was found that gasification of sewage sludge is possible, but the syngas produced must be purified for later use. The heating value of the synthesis gas from sewage sludge was obtained at ~4 MJ·Nm−3 [117]. One of the studied methods of producing syngas was microwave-assisted gasification of sewage sludge and the influence of gasification agents: steam and CO2. An increase in the efficiency of syngas in a steam-CO2 mixed atmosphere was demonstrated. At a temperature of 700 °C with a steam to CO2 ratio of 36, an H2 concentration of 63.73% by volume was obtained. The authors calculated that microwave-assisted gasification of 1 kg of sewage sludge can convert into 7801 kJ of electrical energy using solid oxide fuel cells [120].

Carotenuto et al.’s (2023) [125] research, conducted using Aspen Plus V8.8 (Bedford, MA, USA) simulation software, showed that sewage sludge gasification using combined heat and power production can reduce CO2 emissions compared to natural gas combustion. This process allowed obtaining up to 2.54 kW/kg of dry solids and 0.81 kW of electrical power, with specific parameters, where the CO2 emission reduction reaches 0.59 kgCO2/kg of sewage sludge, making gasification competitive with conventional natural gas combustion in the context of heat and power generation.

The tar produced during gasification can lead to problems such as coke formation and filter and pipe blockage, which results in serious system downtime. The data show that the tar content in syngas from a circulating fluidized bed biomass gasifier with air injection was around 10 g/m3, and could vary from 0.5 to 100 g/m3, depending on the type of device. However, the required tar level in most syngas applications should not exceed 0.05 g/m3, and often even lower [126].

5. Prospects for the Development of Thermal Methods of Sewage Sludge Processing

Sewage sludge is a valuable “raw material” for energy production and a biochemically stabilized product that can be used in agriculture, land reclamation, and construction per the principles of a circular economy. Thermal treatment of sewage sludge is a technological concept consistent with the idea of sustainable development. Thermal treatment of sewage sludge is a technologically and economically promising solution. However, optimisation is required to achieve a product that maximises the plant’s profitability.

To achieve carbon neutrality by the mid–21st century, several actions must be taken in research areas, introducing solutions based on innovative technologies.

When considering the development prospects for the broadly defined field of sludge management, it is important to note that thermal treatment of sewage sludge requires a holistic approach to the technology used and its optimization to eliminate environmental threats and acquire additional resources and energy simultaneously.

Local solutions ensure biomass is valorised as close to its production site as possible, eliminating the financial costs associated with transporting potentially lower-quality raw materials or the threat of having to import biomass to ensure the continued operation of the installation. This local approach to installing using thermal processing methods is closely linked to their sustainable development, ensuring the potential feasibility of the installations and the development of innovative and ecological solutions in the region, based on technologies that require lower financial outlays than conventional technologies. Lamers et al. (2008), assuming that cost reductions occur at the system level, reported cost reductions per unit biogas area ranging from −0.46 to −0.21 USD for biochemical conversion pathways, and from −0.32 to −0.12 USD for thermochemical conversion pathways [127].

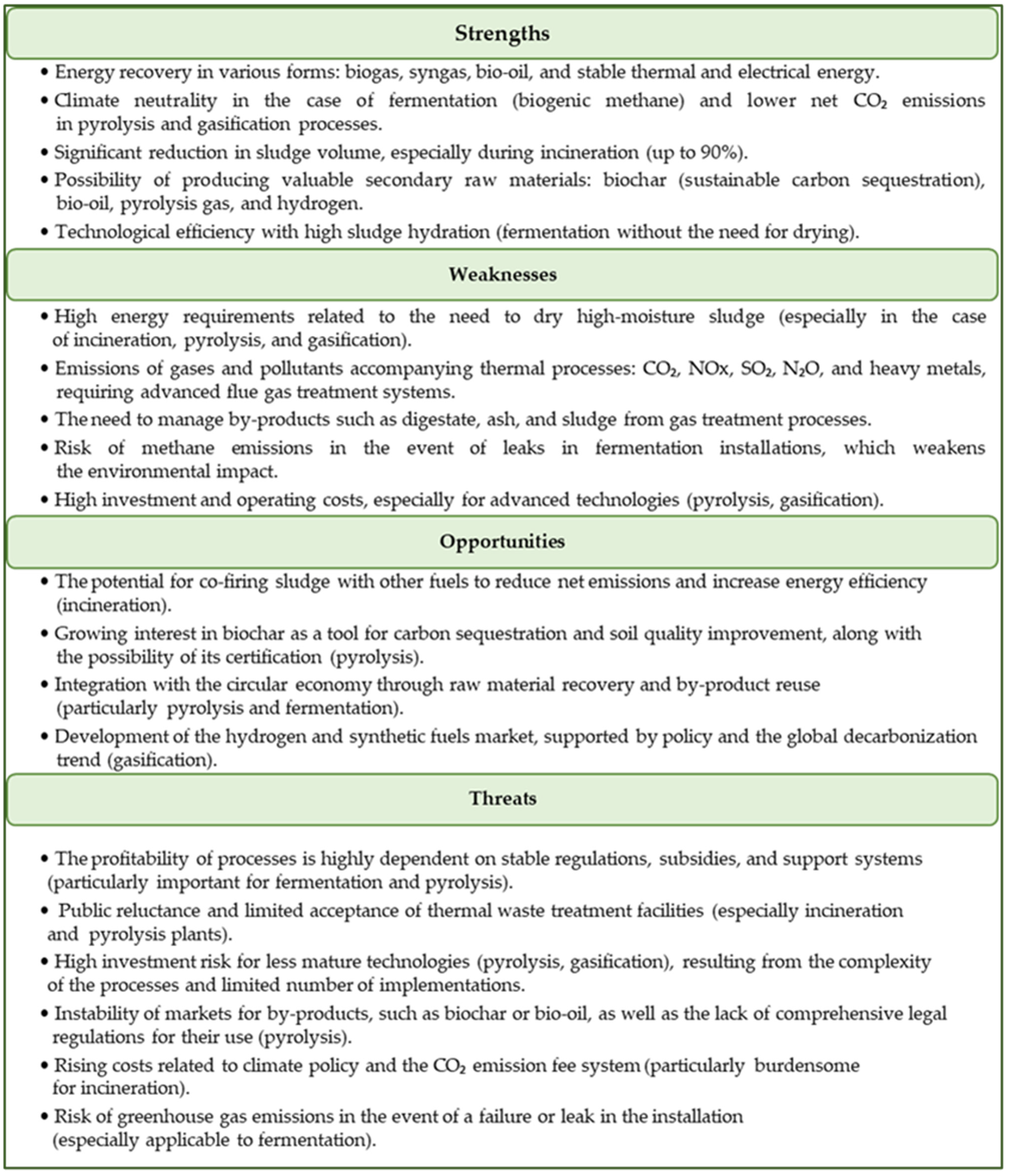

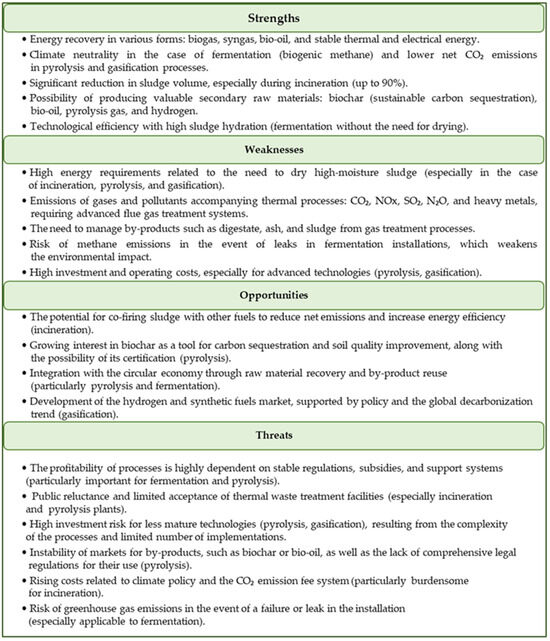

The appropriate technology for thermal conversion of sewage sludge depends on its properties and variability, which simultaneously impacts emissions. A brief SWOT analysis compares technologies emphasizing energy efficiency, environmental trade-offs related to the decarbonization imperative, and sustainable development strategies. The SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) framework allowed for a systematic assessment of internal and external factors influencing individual methods’ feasibility and long-term sustainability. This analysis aimed to demonstrate the potential of thermal sludge conversion technology and identify key challenges and strategic implications for future sludge management efforts (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

SWOT Analysis of Thermal Sludge Conversion Technology.

Modern sewage sludge processing technologies possess several strengths that make them attractive in the context of a circular economy and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Analysis has shown that their common advantage is the ability to recover energy from waste in various forms—biogas, syngas, bio-oil, or stable thermal and electrical energy—which contributes to increasing the share of renewable energy sources [58,62,102,103,114]. A significant element, particularly combining pyrolysis and gasification, is the potential to reduce CO2 emissions compared to conventional combustion, and in the case of fermentation, additionally, climate neutrality resulting from the use of methane in a cogeneration system as a source of energy and heat. Despite their many advantages, sewage sludge processing technologies also have significant limitations. Common weaknesses include high energy consumption, particularly related to the need to dry high-moisture sludge, which significantly increases the operating costs of combustion, pyrolysis, and gasification [82,107,128]. Thermal processes also pose a problem with emissions of pollutants such as CO2, NOx, SO2, N2O, and heavy metals, which require costly and advanced flue gas treatment systems [86,128,129]. A common challenge is the management of byproducts—ash, digestate, and gas treatment residues—which are not always used commercially [130,131].

Sewage sludge processing technologies face several market, regulatory, and social factors threats. One of the main threats common to most methods is intense competition from other, cheaper, and more developed renewable energy sources, which may limit the profitability of investments in such installations. Furthermore, the still limited social acceptance of thermal waste treatment facilities, such as incinerators or pyrolysis plants, may pose a barrier to implementing new solutions [132].

In the case of anaerobic stabilization, future efforts should be focused on improving the quality and specific production of biogas, accelerating kinetic reactions to shorten detention times, implementing various techniques for pre-disintegration of sewage sludge, and ultimately reducing costs. In the case of combustion, solving problems related to ash slag, sintering, and corrosion is crucial, emphasizing ash reuse, while simultaneously eliminating heavy metals, preceded by effective pre-drying techniques. For the pyrolysis process, optimization of experimental conditions to improve the quality of extracted crude oil and gas, and the effective use of generated coal waste, preceded by the implementation of economical and energy-efficient pre-drying methods, are key to further development. For the development of the gasification process, it is important to optimize the process conditions in order to effectively obtain gas and reduce emissions, minimize and remove tar, solve technological problems related to ash slag, sintering, and corrosion, and implement effective pre-drying techniques [70,133,134,135,136,137].

From the perspective of the development of broadly understood sludge management, it should be noted that the processing of sewage sludge using thermal methods requires a holistic approach to the technology used and its optimization, i.e., simultaneous elimination of environmental threats and obtaining, in the form of “added value”, an alternative energy source.

6. Summary

Issues concerning the processing of sewage sludge, which poses a serious sanitary hazard, are a significant research problem, the solution of which is the implementation of new or technologically modified methods of its processing into a valuable source of energy. The idea of research conducted by many scientists over the years was to create new technological solutions that would ensure the recovery of valuable materials contained in sewage sludge and, at the same time, guarantee compliance with restrictive conditions regarding the deposition of sludge in landfills. In the sludge processing chain, the need to introduce technologies for obtaining energy from sludge is an important and open issue, especially in large sewage treatment plants, where the dominant method of sludge stabilization is anaerobic fermentation. In the process of anaerobic fermentation conducted conventionally, an environmentally safe product is obtained in the form of stabilized sludge, and biogas, a valuable energy source. An important element of scientific experiments conducted in many research centers is the focus on obtaining energy from sewage sludge in the form of biogas, biohydrogen, biodiesel, or its transformation in CHP modules into electricity and heat, in relation to other methods of management, such as their agricultural and natural use.

The high content of organic substances and the appropriate low final hydration of sewage sludge from large sewage treatment plants create the possibility of their combustion or co-combustion, but also predispose them to processing in the process of composting and anaerobic fermentation, and, as a result, obtaining various forms of energy.

The growing demand for fossil raw materials, the reduction in their deposits, and the progressive degradation of the environment are a premise for the search for new sources of resources and energy. To sum up, it should be stated that from an economic point of view, it is justified to subject biomass to integrated processing methods leading to the acquisition of biofuels, heat, electricity, and chemicals. The essence of these methods is the acquisition of specific groups of so-called compounds. Precursors are most often used using physical or physicochemical methods. The obtained semi-finished products are subjected to further processes based on biochemical, chemical, and thermal transformations.

An iterative approach to the currently used thermal sludge processing technologies is recommended, which, in addition to obtaining valuable raw materials and energy from sludge, would aim to decarbonize this sector of the economy completely.

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, M.M. and I.Z.; validation, M.M., I.Z. and M.R.; formal analysis, M.M.; resources, M.M., I.Z. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., I.Z. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the statute subvention of Czestochowa University of Technology, Faculty of Infrastructure and Environment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| BOD5 | Biochemical Oxygen Demand, mg O2/L |

| CAPEX | Capital Expenditures |

| CFB | Circulating Fluidized Bed |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CHP | Combined Heat And Power |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand, mg O2/L |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| H2 | Hydrogen |

| H2S | Hydrogen Sulfide |

| I-TEQ | International Toxic Equivalent |

| LHV | Lower Heating Value |

| MGF | Moving Grate Furnace |

| MHF | Multiple Hearth Furnace |

| N2 | Nitrogen |

| NaOH | Sodium Hydroxide |

| NEW | Nutrient–Energy–Water |

| NH3 | Ammonia |

| NiO | Nickel Oxide |

| NiO/MD | Nickel(II) Oxide Catalyst Supported On A Mineral-Derived Material |

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides |

| O2 | Oxygen |

| OPEX | Annual Operating Costs |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| PCBs | Polychlorinated Biphenyls (Chlorinated Compounds) |

| SDC | Sustainable Development Criteria |

| SO2 | Sulfur Dioxide |

| SOx | Sulfur Oxides |

| SWOT | Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, And Threats |

| TS | Total Solids |

| VFA | Volatile Fatty Acids |

| WWTPs | Wastewater Treatment Plants |

References

- Rani, A.; Snyder, S.W.; Kim, H.; Lei, Z.; Pan, S.-Y. Pathways to a net-zero-carbon water sector through energy-extracting wastewater technologies. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asunis, F.; Cappai, G.; Carucci, A.; De Gioannis, G.; Dessì, P.; Muntoni, A.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Rossi, A.; Spiga, D.; et al. Dark fermentative volatile fatty acids production from food waste: A review of the potential central role in waste biorefineries. WMR J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2022, 40, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, I.; Gaudet, N.; Lask, J.; Maier, J.; Tchouga, B.; Vargas-Carpintero, R. Bioeconomy: Shaping the Transition to a Sustainable, Biobased Economy; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, S.; Kumar, A.N.; Sravan, J.S.; Chatterjee, S.; Sarkar, O.; Mohan, S.V. Food Waste Biorefinery: Sustainable Strategy for Circular Bioeconomy. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 248, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grübel, K.; Machnicka, A.; Nowicka, E.; Wacławek, S. Mesophilic–thermophilic fermentation process of waste activated sludge after hybrid disintegration. Proc ECOpole 2013, 7, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Toja, Y.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Amores, M.J.; Termes-Rifé, M.; Marín-Navarro, D.; Moreira, M.T.; Feijoo, G. Benchmarking wastewater treatment plants under an eco-efficiency perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zawieja, I. Sewage Sludge as a Source of Energy and Resources in the Aspect of Sustainable Development; Częstochowa University of Technology Publishing House: Częstochowa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Xin, X.; Ai, X.; Hong, J.; Wen, Z.; Li, W.; Lv, S. Synergic role of ferrate and nitrite for triggering waste activated sludge solubilisation and acidogenic fermentation: Effectiveness evaluation and mechanism elucidation. Wat. Res. 2022, 226, 119287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieja, I.; Brzeska, K. Effect of Fenton’s reagent on the Intensification of the hydrolysis phase of methane fermentation of excess sludge and microbiological indicators. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 263, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, J.; Worwąg, M.; Wystalska, K.; Zawieja, I.; Gałwa-Widera, M. Potential Possibilities of Processing Excess Sludge Generated in the Technological Line of a Municipal Sewage Treatment Plant. Gas Water Sanit. Technol. 2013, 6, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Renewable and Low-Carbon Hydrogen—State of Play and Outlook. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/767227/EPRS_BRI (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Hydrogen. Updated 27 February 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/hydrogen (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Du, R.; Li, C.; Liu, Q.; Fan, J.; Peng, Y. A review of enhanced municipal wastewater treatment through energy savings and carbon recovery to reduce discharge and CO2 footprint. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 364, 128135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maktabifard, M.; Al-Hazmi, H.E.; Szulc, P.; Mousavizadegan, M.; Xu, X.; Zaborowska, E.; Li, X.; Mąkinia, J. Net-zero carbon condition in wastewater treatment plants: A systematic review of mitigation strategies and challenges. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2023, 185, 113638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neczaj, E.; Grosser, A. Circular economy in wastewater treatment plant–challenges and barriers. Proceedings 2018, 2, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandiglio, M.; Lanzini, A.; Soto, A.; Leone, P.; Santarelli, M. Enhancing the energy efficiency of wastewater treatment plants through co-digestion and fuel cell systems. Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, K.; Shehata, N.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Mahmoud, M.S.; Olabi, A.G. The role of wastewater treatment in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs) and sustainability guideline. Energy Nexus 2022, 7, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea Vivas, M.A.; Seguí-Amórtegui, L.; Guerrero-García-Rojas, H. Analysis of greenhouse gas production at the El Prat del Llobregat wastewater treatment plant, Spain: The decarbonization challenge. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 22, 10415–10432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.J.; Pagilla, K. Pathways to Water Sector Decarbonization, Carbon Capture and Utilization; IWA Publishing: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Faber, A.; Jarosz, Z. Characteristics of Sustainable Development of Bioeconomy in Poland-Ecological Dimension. Sci. J. Warsaw Univ. Life Sci.—World Agric. Probl. 2023, 23, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neczaj, E.; Grosser, A.; Częstochowa University of Technology. Environmental Safety of Biowaste in the Circular Economy: Monograph; Publishing Office of Czestochowa University of Technology: Częstochowa, Poland, 2022; ISBN 8371938500. [Google Scholar]

- The European Parliament; The Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, 2018, 82–209. [Google Scholar]

- Lubowicz, J. RED II Directive—Calculation of GHG Emissions for Renewable Fuels. Naft.-Gaz 2023, 79, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal; ESDN Report 2020; ESDN Office: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Przybojewska, I. Forests in the Context of Legal Regulations of Climate Protection. Prawne Problemy Górnictwa I Ochrony Środowiska 2023, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacprzak, M.J.; Kupich, I. The Specificities of the Circular Economy (CE) in the Municipal Wastewater and Sewage Sludge Sector—Local Circumstances in Poland. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2023, 25, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gromiec, M. A New "Nutrition-Energy-Water" Paradigm for Water and Sewage Companies. Water Supply, Water Quality, and Water Protection; Dymaczewski, Z., Walkowiak, J., Urbaniak, A., Eds.; PZITS: Poznań, Poland, 2016; pp. 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Krawczyk, Ł.; Iskra, K.; Przygoda-Kuś, P.; Józefiak, P. Directions of Development of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants: Innovative Solutions in the Face of a Circular Economy: Monograph; Institute of Environmental Protection-National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2022; ISBN 8360312990. [Google Scholar]

- Smol, M. Green Deal Implementation Strategies; Institute of Environmental Protection-National Research Institute: Warsaw, Poland, 2021; ISBN 9788396196033. [Google Scholar]

- Vu, M.T.; Nguyen, L.N.; Zdarta, J.; Mohammed, J.A.H.; Pathak, N.; Nghiem, L.D. Wastewater to R3–Resource Recovery, Recycling, and Reuse Efficiency in Urban Wastewater Treatment Plants. In Clean Energy and Resource Recovery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Błaszczyk, W.; Siatecka, A.; Tlustoš, P.; Oleszczuk, P. Occurrence and Dissipation Mechanisms of Organic Contaminants during Sewage Sludge Anaerobic Digestion: A Critical Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 945, 173517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymaczewski, Z.; Oleszkiewicz, J.A.; Sozański, M.M. Sewage Treatment Plant Operator’s Guide; PZITS: Poznań, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Podedworna, J.; Heidrich, Z. Characterization of Sludge from Selected Sewage Treatment Plants with a View of Their Use for Non-Industrial Purposes. Environ. Eng. Prot. 2001, 4, 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kijo-kleczkowska, A.; Otwinowski, H.; Środa, K. Properties and Production of Sewage Sludge in Poland with Reference to the Methods of Neutralizing. Arch. Waste Manag. Environ. Prot. 2012, 14, 59–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, B.J.; Rodrigues, E.; Gaspar, A.R.; Gomes, Á. Energy Performance Factors in Wastewater Treatment Plants: A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 322, 129107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, J.; Bień, J.D.; Wystalska, K. Problems of Sludge Management in Environmental Protection; Częstochowa University of Technology Publishing House: Częstochowa, Poland, 1998; ISBN 8371930313. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, D.; Feng, P.; Hao, B.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S. Municipal Sewage Sludge Incineration and Its Air Pollution Control. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietraszek, P.; Podedworna, J. Laboratory Exercises in Sewage Sludge Technology; Publishing House of the Warsaw University of Technology: Warsaw, Poland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bien, J.B. Sewage Sludge. Theory and Practice; Częstochowa University of Technology: Częstochowa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zawieja, I.; Wolny, L. Generation of Volatile Fatty Acids from Thickened Excess Sludge Subjected to the Disintegration of High Acoustic Power Ultrasonic Field. Pol. J. Environ. Stud 2011, 20, 346–350. [Google Scholar]

- Płuciennik-Koropczuk, E.; Myszograj, S. New Approachin COD Fractionation Methods. Water 2019, 11, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyens, E.; Baeyens, J. A Review of Thermal Sludge Pre-Treatment Processes to Improve Dewaterability. J. Hazard. Mater. 2003, 98, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, J.T.; Carlson, D.A. The Kinetics of Anaerobic Long Chain Fatty Acid Degradation. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1970, 42, 1932–1943. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Kuninobu, M.; Kakimoto, K.; Ogawa, H.I.; Kato, Y. Upgrading of Anaerobic Digestion of Waste Activated Sludge by Ultrasonic Pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 68, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neczaj, E.; Bohdziewicz, J. Anaerobic Stabilisation of Excess Sludge Thickened with the Ultrafiltration Process. Inz. I Ochr. Sr. 2003, 6, 313–324. [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J.A.; Ferguson, J.F. Solubilization of Particulate Organic Carbon during the Acid Phase of Anaerobic Digestion. J. Water Pollut. Control Fed. 1981, 53, 352–366. [Google Scholar]

- Zawieja, I.; Lidia, W.; Marta, P. Impact of the Excess Sludge Modification with Selected Chemical Reagents on the Increase of Dissolved Organic Substances Concentration Compounds Transformations in Activated Sludge. Environ. Res. 2017, 156, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, D.; Han, X.; Chen, H.; Yuan, R.; Wang, F.; Zhou, B. New Insights into Impact of Thermal Hydrolysis Pretreatment Temperature and Time on Sewage Sludge: Structure and Composition of Sewage Sludge from Sewage Treatment Plant. Environ. Res. 2020, 191, 110122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; He, P.; Lü, F.; Shao, L.; Wang, P. Extracellular Enzyme Activities during Regulated Hydrolysis of High-Solid Organic Wastes. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4468–4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, J.; Lehne, G.; Schwedes, J.; Battenberg, S.; Näveke, R.; Kopp, J.; Dichtl, N.; Scheminski, A.; Krull, R.; Hempel, D.C. Disintegration of Sewage Sludges and Influence on Anaerobic Digestion. Water Sci. Technol. 1998, 38, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T.; Kudo, K.; Nasu, Y. Anaerobic Waste—Activated Sludge Digestion—A Bioconversion Mechanism and Kinetic Model. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1993, 41, 1082–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Noike, T. Upgrading of Anaerobic Digestion of Waste Activated Sludge by Thermal Pretreatment. Water Sci. Technol. 1992, 26, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohányos, M.; Zábranská, J.; Jenícek, P. Enhancement of Sludge Anaerobic Digestion by Using of a Special Thickening Centrifuge. Water Sci. Technol. 1997, 36, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Park, C.; Kim, T.H.; Lee, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J. Effects of Various Pretreatments for Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion with Waste Activated Sludge. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2003, 95, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukas-Płonka, Ł.; Zielewicz-Madej, E. Stabilization of Excess Sludge in the Methane Fermentation Process. Environ. Prot. Eng. 2000, 3, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zielewicz, E. Ultrasonic Disintegration of Excess Sludge in the Extraction of Volatile Fatty Acids; Scientific Silesian University of Technology: Gliwice, Poland, 2007; pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, G.P.B.; Santiañez, W.J.E.; Trono Jr, G.C.; Montaño, M.N.E.; Araki, H.; Takeuchi, H.; Hasegawa, T. Seaweed Biomass of the Philippines: Sustainable Feedstock for Biogas Production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 38, 1056–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawieja, I. Influence of Ultrasonic Field on Methane Fermentation Process: Review. Chem. Process Eng. New Front. 2023, 44, e35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momčilović, A.J.; Stefanović, G.M.; Rajković, P.M.; Stojković, N.V.; Milutinović, B.B.; Ivanović, M.P. The Organic Waste Fractions Ratio Optimization in the Anaerobic Co-Digestion Process for the Increase of Biogas Yield. Therm. Sci. 2018, 22, S1525–S1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, K.; Wang, H.; Hua, Y.; Dai, X. Modulating Interspecies Electron and Proton Transfer by Conductive Materials toward Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion: A Review. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrel, L. Methodology for Evaluating the Efficiency of the Methane Fermentation Process of Selected Sewage Sludge; PB Publishing House: Warszawa, Poland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nwokolo, N.; Mukumba, P.; Obileke, K.; Enebe, M. Waste to Energy: A Focus on the Impact of Substrate Type in Biogas Production. Processes 2020, 8, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, T.; Gogolek, P.; Hughes, P. Application of Waste Heat Recovery in Biomass-Fired Systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 73, 982–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorek-Osikowska, A.; Martín-Gamboa, M.; Iribarren, D.; García-Gusano, D.; Dufour, J. Thermodynamic, Economic and Environmental Assessment of Energy Systems Including the Use of Gas from Manure Fermentation in the Context of the Spanish Potential. Energy 2020, 200, 117452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Publications Office of the EU. EU Bioeconomy Strategy Progress Report; European Bioeconomy Policy: Stocktaking and Future Devel-Opments; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022; ISBN 978-92-76-50201-2. [Google Scholar]

- Zawieja, I.; Wolski, P.; Wolny, L. Recovering of Biogass from Waste Deposited on Landfills. Ecol. Chem. Eng. A 2011, 18, 923–932. [Google Scholar]

- Prussi, M.; Padella, M.; Conton, M.; Postma, E.D.; Lonza, L. Review of Technologies for Biomethane Production and Assessment of Eu Transport Share in 2030. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlat, N.; Fahl, F. Heat and Power from Biomass: Technology Development Report; Joint Research Centre (JRC), European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; ISBN 9276124322. [Google Scholar]

- Hagos, K.; Zong, J.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Lu, X. Anaerobic Co-Digestion Process for Biogas Production: Progress, Challenges and Perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 76, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladejo, J.; Shi, K.; Luo, X.; Yang, G.; Wu, T. A Review of Sludge-to-Energy Recovery Methods. Energies 2019, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, B.; Dienemann, C.; Kabbe, C.; Brandt, S.; Vogel, I.; Roskosch, A. Sewage Sludge Management in Germany; Umweltbundesamt: Berlin, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mosko, J.; Pohořelyý, M.; Zach, B.; Svoboda, K.; Durda, T.; Jeremias, M.; Šyc, M.; Vaclavkova, S.; Skoblia, S.; Beňo, Z. Fluidized Bed Incineration of Sewage Sludge in O2/N2 and O2/CO2 Atmospheres. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 2355–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogada, T.; Werther, J. Combustion Characteristics of Wet Sludge in a Fluidized Bed: Release and Combustion of the Volatiles. Fuel 1996, 75, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urciuolo, M.; Solimene, R.; Chirone, R.; Salatino, P. Fluidized Bed Combustion and Fragmentation of Wet Sewage Sludge. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2012, 43, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Niu, M.; Jiang, X.; Liu, J. Combustion Characteristics of Sewage Sludge in a Fluidized Bed. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 10565–10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werther, J.; Ogada, T. Sewage Sludge Combustion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 1999, 25, 55–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamyab, H.; Yuzir, A.; Ashokkumar, V.; Hosseini, S.E.; Balasubramanian, B.; Kirpichnikova, I. Review of the Application of Gasification and Combustion Technology and Waste-to-Energy Technologies in Sewage Sludge Treatment. Fuel 2022, 316, 123199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untoria, S.; Rouboa, A.; Monteiro, E. Hydrogen-Rich Syngas Production from Gasification of Sewage Sludge: Catalonia Case. Energies 2024, 17, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śpiewak, K. Gasification of Sewage Sludge—A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, A.; Iwasaki, T.; Noto, T.; Hashimoto, H.; Sugiyama, N.; Hattori, M. Application of CFB (Circulating Fluidized Bed) to Sewage Sludge Incinerator. NKK Tech. Rev. 2002, 86, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski, Z.; Wzorek, Z.; Jodko, M.; Gorazda, K. Properties of Sewage Sludge and of the Thermally Processed Sewage Sludge Ash. Przem. Chem. 2003, 82, 1034–1036. [Google Scholar]

- ISWA Working Group on Sludge and Waste. Sludge Treatment and Disposal: Management Approaches and Experiences; Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1998; ISBN 9291670812. [Google Scholar]