Abstract

The current transformation of global energy systems has been the subject of a multi-faceted scientific discourse for years. Researchers focus on technical and technological aspects, seeking new and improved alternatives to current solutions. They also analyse formal and legal frameworks of the changes and evaluate their economic aspects or environmental effects. The public’s attitude towards the changes in light of demanding environmental conditions is investigated the least. In particular, little heed is paid to the opinions of rural populations, especially in Poland. In light of the above, this paper aims to analyse the issue of Poland’s energy transition and the public’s perception of the challenges of environmental protection and the resulting need to improve energy solutions to promote the dissemination of renewable energy sources. The research area was Poland, and detailed research was conducted in five districts (Małopolska region), where the age of the respondents was taken as the differentiating feature. The study was based on a literature review and, at a detailed level, on a diagnostic survey among residents of Wadowicki, Miechowski, Krakowski, Limanowski, and Tarnowski Districts. The 2024 CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing) survey involved 300 randomly selected interviewees. The study employed a qualitative and quantitative approach, utilising statistical tools such as Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis, the Kruskal–Wallis rank test, and the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. The statistical analysis was supported by IBM’s SPSS v.25. The results show that the majority of the population understand and agree with the need for an energy transition in Poland towards renewable energy. Indications of no opinion or in favour of non-renewable energy in the Polish energy system are distinct. This class of indications is determined by the interviewees’ age and suggests potential for improving public awareness of the matter in the group of mature respondents.

1. Introduction

The transformation of the energy systems of the world’s economies is oriented towards increasing the share of green energy sources in the energy mix. Green energy markets are growing strongly, offering an ever-widening choice of solutions for responsible energy production. The socio-economic and environmental importance of this issue is crucial to the expected socially secure development of the world [1]. A secure future growing out of this creates a new socially expected value. In line with this, the energy transition is now regarded as one of the most important global challenges. Emphasis is placed on it by individual countries, regions and continents, and the real needs in this area are related to the ongoing climate change [2].

The world’s energy transition is proceeding unevenly. This is based on the availability of energy resources, the economic policies pursued and the economic condition of individual countries. Within the economies themselves, there are areas in which the transformation process is taking place at different speeds. As a rule, highly urbanised, modern conurbations are subject to strong development, while rural areas are subject to relatively limited development. Research interest can be observed in similar proportions. The literature is most concerned with the formal and legal aspects of the changes taking place, aspects of existing and future technical and technological solutions, and evaluations of the economics of these solutions and the environmental consequences of their application. The research literature is least focused on the area of assessing social attitudes towards the challenges in question, with particularly little research into the attitudes of rural residents in this regard, particularly in Poland. In response to this research gap, the aim of this paper is to analyse and evaluate social perception of environmental challenges and the resulting need to improve energy solutions to enhance renewable energy sources in these areas. Due to the particular topicality of the challenges in question for the energy system in Poland, five counties in the Małopolska region were selected as the study area to explore this issue, with the analytical process referencing the age of the respondents (differential cohort).

The realisation of the above-stated main objective of this study is supported by explaining the mechanics of energy transformation in the world and in Poland. The purpose of the supplementary objective, which is to present the idea, scope and pace of transformational changes taking place, is to provide a cognitive reference for the research conducted within the framework of the main objective.

With this in mind, this study was based on the results of the literature survey conducted to achieve the supplementary objective. The realisation of the primary objective of the study was based on the findings of the diagnostic survey, aimed at determining rural residents′ social awareness of sustainable development, as well as assessing the expected outcomes of the ongoing energy transition process. The object of interest of this paper is solely to capture the issues of energy transformation in the study area. The adopted scope of the study is its limitation. The other aspects of the study are the subject of separate papers; the present paper is part of the authors’ series of publications, arranged thematically.

For the purposes of this study, this paper is structured as follows:

- Abstract,

- Introduction,

- Literature survey,

- Presentation of research results,

- Dissertation,

- Conclusion.

The study was conducted using qualitative and quantitative methods. In-depth research was carried out using statistical instruments. The choice of methods was determined by the nature and scope of the research, and the necessity to ensure comparability of results developed at different levels of research (scope of separate works).

2. Literature Review

Energy transition ‘aims to convert the global economy from a high-emission system into a diversified and sustainable mechanism’ [3] This means a substantial restriction or abandonment of coal and other fossil fuels in the economies of most countries. This goal requires an increased share of renewable energy [3] and improved energy efficiency [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The objective is critical because greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), which drive the planet’s violent heating, must be reduced. It is also a requirement for expediting economic growth and development [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Today’s global energy sector is dominated by fossil fuels and accounts for 73% of anthropogenic GHG emissions [9,15,16,17].

The coming years and decades will be a time of intense energy transition efforts for entire regions and individual countries alike [18,19,20]. The activities will be founded on energy policy, which is part of climate policy, i.e., changes in energy supply and demand, innovations, technological progress, and securing funding [9,21,22,23,24]. Importantly, the energy transition should be implemented quickly and involve a radical overhaul of the system. It is particularly relevant for furthering SDG7, which ‘is about ensuring access to clean and affordable energy, which is key to the development of agriculture, business, communications, education, healthcare and transportation’ [25] and decarbonisation of the energy system by 2050 [26,27]. A decline in renewable energy technology costs has opened up new opportunities in this regard [28,29,30,31].

These goals align with the premises pursued by European Union institutions. This includes Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources. It has set EU goals for 2030 and ‘modified the methods for calculating shares of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption from 2021 on’ [31]. In 2023, the European Parliament proposed a new 2030 goal for 42.5% of the energy consumed in member states to be renewable energy [32,33,34,35,36]. Simultaneously, countries are encouraged by the REPowerEU Initiative to aim for 45% to expedite the transition [37]. The plan involves furthering the shift to clean energy, including a phase-out of energy imports from Russia [38,39]. This should lead to an increasing share of renewable energy generation in strategic sectors, like industry, construction, and transport. The ambitious plan promoted by European Union institutions intends for Europe to be the first climate-neutral continent by 2050 [40,41,42].

The share of renewable energy is growing in EU member states [36,43,44]. It increased from 23% in 2022 to 24.5% in 2024. Note that it is over twice as much as 9.6% in 2004. Green energy has grown in transport as well: from 9.6% in 2022 to 10.8% in 2023.

According to Eurostat, more than two-thirds of the total electricity from renewable sources in the EU in 2023 was wind and hydropower energy (38% and over 28%, respectively). The remaining energy sources were solar (over 20%), solid biofuels (approximately 6%), and other renewables (nearly 7%). Note that solar energy is the fastest-growing renewable energy source; in 2008, it accounted for only 1% of renewable energy. Data for 2023 indicate impressive growth in photovoltaic energy, increasing from 7.4 TWh in 2008 to 252.1 TWh in 2023 [45].

The global trend towards renewable energy is accelerating. Micro-installations are a strongly marked trend in the development of energy systems [46]. Their development is determined by a number of factors [47,48] and supported by a specific set of expectations in relation to such an investment [49].

The growing availability of techniques and technologies [50] in the field of renewable energy sources is leading to an increase in the number of electricity producers. The global trend of interest in these solutions contributes to the continuous strengthening of the role of micro-installations in the energy transition of economies. This implies the need for an in-depth analysis of the current direction of change and an assessment of its suitability for the current challenges of responsible global development. The available studies generally address this issue at the general national level, without reference to the level of the region concerned [51]. This motivates research at the level of the country and region under study and constitutes their distinguishing feature. The above is of particular importance in relation to the level of research in rural areas, where the pace of transformation is generally slow. The outlined background provides the basis for establishing the following research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

The transformation of the energy system in Poland towards renewable energy sources is progressing, and micro-installations are an important element of this process.

Hypothesis 2.

The development of micro-installations in the transformation of the Polish energy system requires further promotion and continued financial support in order to maintain the momentum of strengthening renewable energy sources in the country’s energy system, including in rural areas in Małopolska.

When analysing the issue of energy transition, it is impossible not to draw attention to the theme emphasised in the literature of inequality in access to solutions in rural and urban areas and the need to ensure a just transition [52]. In this regard, a number of barriers faced by rural areas are pointed out [53,54,55,56], while on the other hand, the multidimensional benefits that this process can bring to rural areas are emphasised. However, the individual attitudes of rural residents towards the energy transition process, particularly in Poland, are not explored in sufficient depth. The impact of the age of rural residents on their individual attitudes towards the challenges of transformation is not analysed sufficiently. This is particularly important in relation to the level of research in rural areas. The background outlined above provides the basis for establishing further research hypotheses that fall within the scope of in-depth research:

Hypothesis 3.

The awareness of rural residents in the Małopolska region regarding the transformation of the country’s energy system needs to be strengthened.

Hypothesis 4.

The position of rural residents in Małopolska regarding the transformation of the energy system in Poland towards renewable energy sources is determined by age.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Concept and Hypotheses

The paper aims to analyse the public perception of environmental protection challenges and the ensuing need to improve energy systems to promote the expansion of renewable energy sources. Considering the particular relevance of these challenges to the Polish energy system, the study area comprises five districts representing rural Małopolskie Voivodeship. The analytical process considered the age of the interviewees to identify the results that are determined by this discriminant feature, providing a more accurate insight into the investigated public opinion.

The paper’s structure is guided by the research objective. The introduction defines the scope and lays out the structure of the work. The background, based on a literature review and relevant reports, is provided in the next section. The literature for the review was compiled mostly using databases of indexed journals, like Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, etc. The review was based primarily on relevant keywords. The empirical part of the study in the introductory section was based on a general review of research findings and reports in order to verify the assumptions contained in the first two hypotheses. At the detailed study stage (Hypotheses 3 and 4), qualitative and quantitative research was conducted. The preliminary analysis was based on economic analysis mechanisms, while the in-depth study methodology, in addition to the rules of economic analytics, took into account statistical inference, necessary for substantive reasoning. The results of the findings were discussed in the context of alternative studies. The research tools used ensured substantive reasoning in the process of verifying the accepted hypotheses.

3.2. Sample Profile and Methods

The first step of the study, a review of the literature on the topic, provided the necessary insight into the existing knowledge of the energy transition in Poland towards renewable energy. A particular focus was necessary on the diagnosis of the advancement of the energy transition towards renewable energy in Poland and the role of microgeneration in this process. These aspects determine the deliberation on Hypotheses 1 and 2. The process of establishing the hypotheses also served to confirm the gap addressed by the paper, justifying the research effort.

The study scope drove the focus towards the specific inputs from the rural population of Małopolskie Voivodeship, Poland. In pursuit of the goal, the authors conducted a CAPI (Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing) survey in 2024 among 300 randomly selected interviewees residing in rural areas of Małopolskie Voivodeship, Poland, specifically in Krakowski, Wadowicki, Tarnowski, Limanowski, and Miechowski Districts, all of which are located within the voivodeship. Each district was represented by 60 people. The results obtained refer only to the sample of people covered by the study and cannot be applied to the entire rural population in Poland.

The sampling technique was chain-referral. Survey participation was completely voluntary and anonymous (informed consent).

The interviewees ranged in age from 15 to 86, and the sample consisted of 58.3% women and 41.7% men (M = 42.30, SD = 17.59). Age was assumed to be the discriminant feature.

In terms of education, 25% of the sample reported vocational education, 44% secondary education, and less than 25% higher education, with 63%confirming they were trained professionals. The results of the χ2 test did not reveal significant differences in education among the districts: χ2(12) = 9.79, p = 0.635 or in the acquired profession: χ2(4) = 7.03, p = 0.134.

The interviews covered 27 questions: 21 topic questions, of which only five concerned energy transition in Poland and were analysed in the study, and six questions related to interviewee profiling. The other questions were linked to different research areas of interest to the authors [57]. The problem investigated in the paper generally concerns sustainable development in the context of climate change and corresponds with the framework defined in the EIB Climate Survey Report [58]. Still, the arrangement and scope of the present study align with Polish constraints, particularly for rural areas.

The diagnostic survey results were analysed with techniques appropriate for in-depth analysis and statistical measurements. To this end, the authors employed Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient analysis for quantitative data and dichotomous (0–1, yes-no) questions, a ranked-based Kruskal–Wallis test for comparing variable distributions across groups, and a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test for verifying sample values across populations. The analyses were supported by the IBM SPSS v.25 suite. Each district was analysed independently.

The methods were selected appropriately as the study involves comparing proportions of survey results among groups.

The methodology employed facilitated the objective. In addition, the methodology and formula used to present the results have been standardised for the cycle of publications by authors presenting research results in thematic areas. This is to ensure multi-faceted comparability of results.

The results obtained refer only to the sample of people covered by the study and cannot be applied to the entire rural population in Poland.

The results may help inform the design of Poland’s energy transition policy, particularly in rural Małopolskie Voivodeship, regarding the growth of microgeneration. Findings regarding age-determined public awareness of renewable energy are particularly relevant to the process. They may be used to design renewable energy educational and promotional programmes dedicated to specific age groups, particularly in rural areas of Małopolskie Voivodeship.

4. Energy Transition in Poland

4.1. Results of the General Study

Poland’s energy transition is linked to the notification of the National Energy and Climate Plan 2021–2030 (NECP) to the European Commission on 30 December 2019. It was an obligation stipulated in Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 December 2018 on the Governance of the Energy Union and Climate Action. The national plan includes premises and goals for five dimensions of the energy union: energy security, internal energy market, energy efficiency, decarbonisation, and research, innovation and competitiveness [59,60].

The 2030 climate and energy objectives Poland set in the NECP are:

- -

- 7% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in sectors not covered by the ETS compared to the 2005 levels,

- -

- 21–23% share of renewable energy in gross final energy consumption (the 23% target would be feasible if Poland were granted additional EU funds, with funds for fair transformation), including 14% share of renewable energy in transport and an average annual increase of renewable energy in heating and cooling of 1.1 pp,

- -

- a 23% increase in energy efficiency compared to PRIMES2007 forecasts,

- -

- 56–60% reduction in electricity from coal [59].

The change over the decade from 2013 to 2023 indicates an increase in renewable energy’s share of gross final energy consumption in Poland. In 2023, the rate was 16.5%, which is 5 pp higher than in 2013. Still, it was 0.4 pp less than in 2022 [32].

According to Statistics Poland, the increase between 2022 and 2023 covers the share of renewable electricity in the gross final electricity consumption of 4.8 pp. The share of renewable energy in final energy consumption for transport was 6.0% in 2023 and is expected to reach 14% by 2030. The largest increase in renewable energy in 2023, over 20%, was identified for heating and cooling [61].

The latest report by the Polish Energy Regulatory Office (ERO) characterises changes in renewable microgeneration systems. Its authors primarily used annual reports of electricity distributors, which report the number of renewable microgeneration systems connected to the grid [62]. A renewable microgeneration system is a power-generating system with a capacity of up to 50 kW. Over 98% of microgeneration systems belong to prosumers who generate renewable energy for their internal consumption. A prosumer ‘may be a natural person, farmer, housing cooperative, or a business owner as long as electricity production is not their primary activity. Prosumers in Poland generate energy mainly from photovoltaic systems [63].

According to the ERO report, the number of registered microgeneration systems exceeded 1.5 million in 2024, whereas in 2019, it was just over 155,000. Nearly the entire energy fed to the grid from microgeneration systems (99.7%) was generated by photovoltaics. Nevertheless, compared to previous years, the increase in the count and capacity of microgeneration systems is slowing down.

Data for late 2024 indicate that over a million prosumer microgeneration systems (two-thirds of the total number) were connected to the grids of the two largest operators in Poland, Tauron Dystrybucja and PGE Dystrybucja. Their networks receive over two-thirds of their energy from the smallest renewable energy systems. Additionally, in 2024, three microgeneration systems were registered by collective prosumers for the first time in Poland’s history. ‘Their total capacity was 0.113 MW, while the aggregate electricity introduced to the grid was 87.768 MWh’ [62]. This shows that the transformation of the Polish energy system is evolving towards renewable energy sources, with microgeneration systems playing an important role.

The ERO’s report offers another interesting insight related to the dynamics of growth in the number of microgeneration systems and the energy they contribute to the network. There was a substantial slowdown in the increase in microgeneration systems and the amount of energy they fed back to the grid in 2024. According to the data, the number of microgeneration systems grew by a mere 10% in 2024, while in 2023, it was 41%. As the authors summarised, ‘Considering the amount of energy fed into the system, the increase was 110% in 2022, 26% in 2023, and 17% in 2024. The increase in microgeneration system capacity is also slower: in 2022, the total capacity grew by 52%, in 2023, by 22%, and in 2024, by 12%.’ [63].

Renewable energy sources can also be larger than microgeneration systems. In that case, they are referred to as small-scale systems. A small-scale energy generation system is defined in the 2021 regulations as a system of a capacity of 50 kW to 1 MW [64]. Recent years have seen a clear increase in the electricity generated in such systems. To quote the ERO’s report, ‘Last year, the capacity of small-scale systems grew over 24% compared to 2023, and their output approached 4.8 TWh’ [65]. The data show that the number of energy-generating entities grew from 3025 in 2023 to 3761 in 2024, while the number of systems increased from 5620 to 6977. The total capacity of renewable small-scale systems surpassed 5 GW at the end of 2024, compared to 4 GW in 2023.

The 2024 mix of small-scale systems in Poland consisted of solar-powered power stations in over 82%. In 2023, they accounted for 78% of all small-scale systems. The second most numerous and largest-capacity technology was wind power. It is followed by hydropower and biogas stations. Their case is slightly different because, although the number and capacity of hydropower and biogas stations increased, their 2024 output was below the 2023 levels. Biomass systems account for a minuscule 0.3% of the renewable small-scale system mix. Interestingly, the first small-scale renewable hydrogen system in Poland was registered in 2024. However, it was reported not to generate any electricity that year.

As a final note, ‘In 2024, all renewable energy systems (including hydropower stations) accounted for 27% of the total energy generation in Poland’ [65].

The results of the presented literature review provide grounds for positive verification of the first of the adopted hypotheses, which states that the transformation of the energy system in Poland towards renewable energy sources is progressing, and that micro-installations are an important element of this process.

4.2. Energy Policy of Małopolskie Voivodeship

The energy transition in Małopolskie Voivodeship is aimed at mitigating climate change, primarily through efforts to reduce GHG emissions. They bear fruit. Measurements over the last three decades indicate a clear reduction in GHG emissions of 18% compared to 1990 and over 9% compared to the 2018 levels (data for 2022). The sectors with the most significant decline in GHG emissions in the voivodeship are power (over 43%), economy (nearly 40%), and agriculture (over 32%). However, such sectors as forestry and land use or transport saw GHG emission increases of +51.75% and over 300%, respectively [66].

Note the significant differences in average GHG emissions per capita among voivodeships, countries, and the EU. The averages for 2021 were 6.55 t CO2eq per capita, 10 t CO2-eq per capita, and 7.5 t CO2-eq per capita (according to Eurostat). The data show that the average GHG emissions per capita in Małopolskie Voivodeship were over 34% lower than the aggregate result for Poland and more than 12% below the EU average [66,67,68].

The current development policy of Małopolskie Voivodeship focuses primarily on energy policy. It provides for the expansion of renewable energy sources based on local potential, which is and will be a catalyst for the regional economic development [60,69,70].

The recent 2025 report of the Strategic Programme for Environmental Protection in Małopolskie Voivodeship for 2022–2023 includes an assessment of the voivodeship’s climate policy, and thus its energy policy. It was drafted for the Małopolskie Voivodeship Board and offers the latest data on the region’s energy transition, focusing on new renewable energy systems. Between 2020 and 2023, 31,613 new renewable energy systems were built in Małopolskie Voivodeship, specifically 10,191 in 2020, 9480 in 2022, and 11,942 in 2023 [62]. The estimated number of renewable energy systems in the voivodeship in 2022 was 550,000, providing 10,380 MW of installed capacity. The most common systems were biomass boilers (47%), photovoltaic systems (40%), solar water heating systems (8.7%), and heat pumps (4.5%) [66].

The differences among individual types of renewable energy systems were clear-cut in 2022 and 2023 (Table 1). Many more renewable energy projects were completed in 2022, especially regarding the installation of photovoltaics (1.7 times more in 2022 than in 2023) and solar water heating (over five times more in 2022) [69,70,71,72].

Table 1.

Count of new renewable energy systems in Małopolskie Voivodeship in 2022–2023 by technology.

Goal 4.1 of the Strategic Programme for Environmental Protection in Małopolskie Voivodeship for 2022–2023 was to prevent climate change and protect air quality. The programme report for 2025 lists completed achievements. Their aggregate cost amounted to PLN 2,598,658,402.87 (USD 697,220,000) in 2022 and PLN 3,067,493,460.57 (USD 822,395,000) in 2023.

The schemes pursued under the programme included:

- -

- Compliance with the obligations imposed by smog-prevention resolutions and the Małopolskie Voivodeship Air Protection Programme, mostly through replacement of solid-fuel boilers;

- -

- Investments in renewable energy, particularly in strategic sectors like energy production, transport, industry, agriculture, and construction (including residential-related projects);

- -

- Improving the energy effectiveness of existing buildings (including public buildings) and investments in modern, integrated built structures with renewable energy systems;

- -

- Adaptation of industrial pollution sources to legal requirements, including IED, MCP, NEC, and international conventions;

- -

- Growth of cogeneration, or combined heat and electricity production;

- -

- Energy transition in mining and coal power areas, along with energy-intensive industries: steelmaking, cement, chemical, and papermaking;

- -

- Promotion of environmentally friendly transport: ‘zero-emission public transport’, electromobility, pedestrian and bicycle mobility, etc.;

- -

- Construction of an integrated and modern zero-emission transport system as the central component in building economic, territorial, and social cohesion of the voivodeship based on safe and reliable public transport [69].

In the long term, the climate and energy policy of Małopolskie Voivodeship is guided by the Regional Action Plan for Climate and Energy for Małopolskie Voivodeship. The plan covers the period from 2021 to 2030. It is aligned with the National Energy and Climate Plan and the European Green Deal strategy. The strategy’s long-term goal is for EU member states to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

The regional action plan has three basic goals:

- -

- ‘to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by not less than 40% compared to 1990 levels, including to 30% compared to 2005 levels for non-ETS sectors (mainly transport, residential, and agriculture);

- -

- to increase the share of renewable energy to at least 32% of the gross final energy consumption;

- -

- to improve energy efficiency to at least 32.5%’ [73].

Currently, the energy transition in Małopolskie Voivodeship is focusing on a strategic call for applications in the western part of the region. This recruitment scheme is part of European Funds for Małopolskie Voivodeship 2021–2027 and covers Chrzanowski, Olkuski, Oświęcimski, and Wadowicki Districts. This region is undergoing an intense energy transition to abandon traditional energy sources in favour of renewable systems.

European Funds for Małopolskie Voivodeship 2021–2027’s Priority 8 ‘European Funds for Fair Transformation of Western Małopolskie Voivodeship’ contains Action 8.11 ‘Energy Transformation’, project type A (Increased Use of Renewable Energy) and project type B (Development of Energetically Sustainable Areas and Energy Communities). Applications can be filed from 29 May 2025 and will be evaluated in December 2025. The fund pool is PLN 50,092,275.16 (USD 13,444,766.65), and the maximum funding threshold is 95% of the project cost.

Increase in renewable energy sources, the A-type project covers the construction and redevelopment of renewable energy systems and battery storage with energy management systems. The funding is available to local governments, various institutions and organisations, micro, small, and medium enterprises, churches and religious associations, non-governmental institution partnerships, social economy enterprises, etc. Moreover, local governments can pursue funding for umbrella projects, that is, the construction and redevelopment of renewable energy sources on single-family residential houses. The B-type project targets energy associations, including energy clusters and energy cooperatives [74].

The energy transition of Małopolskie Voivodeship is underway. Microgeneration systems play an important role in the process and in the energy transition in Poland in general. The need to maintain this development, revealed in the presented literature review, provides grounds for positive verification of the second of the adopted research hypotheses, which states that the development of micro-installations in the transformation of the Polish energy system requires further promotion and maintenance of financial support in order to maintain the momentum of strengthening renewable energy sources in the country’s energy system, including in the rural areas in Małopolska.

It can therefore be assumed that the effectiveness of the transformation process in the studied area is largely determined by the social attitude towards the changes taking place and openness to renewable energy solutions. Hence, the assessment of social openness to renewable energy sources was considered an important topic. Particular attention was paid to the age-determined approach of rural residents in the studied region to aspects of safe development, taking into account the conditions of energy transition. It is assumed that the process of energy transition in rural areas in Małopolska requires education and promotion tailored to the age of the residents, as well as the maintenance and development of financial support programmes, in order to ensure an adequate level of renewable energy in the energy system in rural areas in Małopolska. The search for answers in this area fills the rest of the study and is justified, as relatively little research has been devoted to this issue.

4.3. Detailed Research Based on the Results of the Diagnostic Survey

It is vital for the pursued research concept to identify the age-determined attitude of rural populations towards preventing climate change. It serves as the starting point for any evaluation of the potential challenges linked to the energy transition in Poland, particularly in rural areas, as exemplified by the investigated districts of Małopolskie Voivodeship. This way, it is possible to diagnose the awareness among various age groups and define room for improvement in a way aligned with the age of rural residents.

Interviews with the sample representative of rural areas in Małopolskie Voivodeship, Poland (Krakowski, Wadowicki, Tarnowski, Limanowski, and Miechowski District) in terms of diagnosing climate change prevention attitudes revealed that technological innovations and radical behavioural changes can significantly curb negative trends. In quantitative terms, technological innovations are more frequently reported across the groups, primarily in Tarnowski District (34 people) and the least often in Miechowski District (20 people). In comparison, behavioural changes were the most common in Wadowicki District (31 indications) and the least popular in Limanowski and Tarnowski Districts (24 people each). Statistical tests did not uncover any significant age-related associations in this regard. Therefore, the results can be considered averaged representations of attitudes in individual districts. Detailed results in this regard are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Age-determined attitude towards climate change prevention by district.

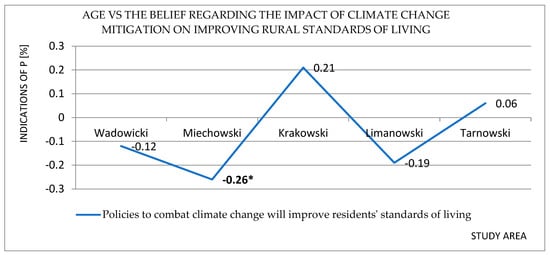

The results above demonstrate that climate change prevention requires action under adopted practices and solutions that reinforce functional security in the countryside, which may suggest openness to changes in the implementation of green power technologies (microgeneration). In this regard, it is worth investigating the distribution of age-determined answers regarding whether climate prevention policies help improve functional standards in the countryside. The relevant results show that rural standards of living are improved by efforts to counteract climate change. Still, only Miechowski District exhibited an age-dependent association in this regard. With increasing age, respondents in this group tended to disagree more and more with the proposal that climate change policy improves rural standards of living. However, the association strength is low for the area (p: −0.26). The distribution of associations for the districts is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Influence of age on the belief regarding the impact of climate change mitigation on improving rural standards of living by district. Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

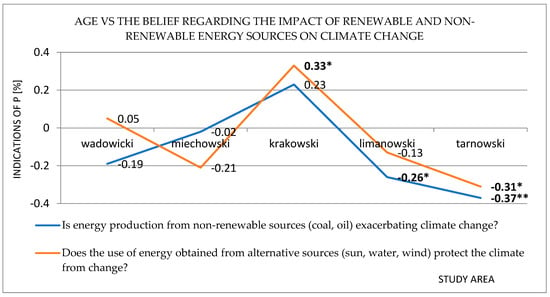

The sentiment towards climate change policy is crucial for analysing attitudes towards Poland’s renewable energy transition. In this regard, it is valuable to identify the age-determined attitude towards non-renewable energy sources in the context of their climate effects. It has been demonstrated that non-renewable energy sources exacerbate climate change, while green energy sources contribute to climate protection. The discriminating variable was found to affect the results in the context of the problem at hand. In Kraków District, the older the interviewee, the more likely they were to indicate that the use of renewable energy sources (solar, hydro, wind) mitigates climate change. The association’s strength was moderately significant. A similar relationship was found in Tarnowski District, where age was clearly associated with agreeing that energy from fossil fuels (coal, oil) intensifies climate change and that green energy sources (solar, hydro, wind) help protect the climate against adverse changes. Both the associations exhibited moderate strengths. Conversely, the older the interviewees in Limanowski District, the less they agreed that energy from conventional sources (coal, oil) adds to climate change. This association was weak. This means that a significant part of the mature population of rural areas appreciates the need to shift the energy system to renewable energy sources. Furthermore, there is room for improvement in the attitude, as demonstrated in Limanowski District (−p: −0.26). The distribution of associations for the districts is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Influence of age on the belief regarding the impact of renewable and non-renewable energy sources on climate change by district. Note: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

The attitude of rural residents to energy sources by district reflects the overall respondent attitude towards Poland’s energy transition. Therefore, the question arises whether the attitude towards the development strategy for the Polish energy system (traditional or renewable energy sources) is determined by the participant’s age. Quantitatively, the orientation towards renewable energy sources was indicated in all the districts. The strongest support was found in Krakowski District (42 people), while the lowest was in Miechowski District (27 people). Hence, the results can be considered a diagnosis of the interviewees’ attitude regarding the expected trend in Poland’s energy transition in the coming decades as favouring renewable energy. Detailed results in this regard are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Age-determined attitude towards Poland’s energy transition by district.

The Tarnowski District sample demonstrated an association between the public’s attitude toward the investigated problem and age. The older the interviewees, the more they were convinced of the transition towards renewable energy, particularly in rural Małopolskie Voivodeship. Answers in favour of coal exhibited a relation of p = 0.029, while indeterminate opinions (‘It’s hard to say’) reached p = 0.023 (results of detailed research).

An investigation into the specific attitudes of the rural population towards energy transition in Poland based on different energy sources revealed that renewable energy sources were the preferred direction. In quantitative terms, residents of Krakowski District chose renewable energy most often (36 people), while the Wadowicki District population was the least in favour of RES (24 people). Another popular choice was nuclear energy. Detailed results in this regard are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Detailed analysis of rural preferences for focusing Poland’s energy transition on specific sources by districts.

Interestingly, all the districts offered voices in support of using fossil fuels in Poland’s energy transition. The declarations reached a relatively similar, if rather low, level, with natural gas outweighing coal. Age dependency was identified for this domain in two districts. In Limanowski District, those in favour of natural gas were older than the individuals advocating for renewable energy (p = 0.002). In Tarnowski District, the people who preferred coal were older than those who chose renewable energy (p = 0.002) and nuclear energy (p = 0.005). Similarly, interviewees who picked natural gas were older than people who leaned towards renewable energy (p = 0.040). This suggests that a substantial part of rural residents from the western Małopolskie voivodeship favour green energy as their age decreases. Considering the sample age interval (15–86), the conservative views of the older participants are relatively predictable. Openness to change in this regard involves a significant commitment, whether organisational, financial, or otherwise, which may be a barrier for older people.

The presented results confirm the hypothesis that age influences the attitude of the interviewed rural population in Małopolskie Voivodeship regarding Poland’s energy transition towards renewable energy. However, the strength of the association remains moderate and pertains to isolated cases in the context of the entire study. This reveals room for improving the awareness of energy transition among the rural population of Małopolskie Voivodeship, as proposed in the second hypothesis. Note that the challenge involves mainly seniors.

5. Discussion

Energy transition is one of the most pressing global challenges. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor public awareness of the matter and sentiments [2,75] regarding the promotion of renewable energy sources [76] in individual countries.

The Energy Regulated Report offers insights into the opinions of energy consumers regarding the use of electricity in Poland. The survey for the Energy Regulatory Office on a representative sample of 1001 households was completed in 2023. Its results indicate that it is not only necessary but also urgent to instigate informational and educational efforts to improve public awareness of energy matters. Among the most critical conclusions was that education should be targeted at the youngest age groups, as their knowledge and awareness were insufficient [77]. The authors of the present study identified a similar association based on their research. The present results show that a significant portion of the older population in rural Małopolskie Voivodeship appreciated the need for a transition towards renewable energy, while younger interviewees exhibited poorer knowledge and less interest in the issue. This is an important aspect that should be taken into account when designing information campaigns about the changes being made.

Results of a 2021 survey by the Centre for Public Opinion Research (CPOR) also confirm that adult Poles are in favour of phasing out coal-based energy systems [78]. Report Energy Transition. Expectations and Demands indicates that most Poles accept green energy, although they differ in terms of the pace of the transformation. Rural residents, those with a lower socioeconomic status, and the oldest age groups are much more interested in a slower deployment of renewable energy sources. Still, the overall expectations regarding the long term of 2050 are clear. The respondents believe renewable energy sources should be the primary source of electricity in Poland by then. A survey on Poles’ position on energy transition that the CPOR repeated in 2023 offered a slightly different view [79]. At that time, the respondents assessed energy transition needs in completely different circumstances. The war in Ukraine and its impact on the energy sector clearly affected their mindset. First, the group in favour of using Poland’s coal reserves for energy purposes grew (particularly among the oldest respondents and in rural settings). Still, there was a significant focus on nuclear energy, with less emphasis on renewable energy sources. The 2024 CPOR’s report, Public Opinion on Energy Policy was published during a time of controversy linked to the European Green Deal [80]. The debate directly affected respondents’ opinions on energy policy. Poles expressed their concerns with the belief that the optimal energy policy should consider renewable and non-renewable sources (Poland’s coal reserves). Moreover, although the level of advocacy for nuclear power stations declined slightly after reaching a historical high in 2022, the technology remains supported by nearly two-thirds of respondents.

In relation to the CPOR’s reports quoted above, the present study addressed a relevant question regarding the attitude of the rural population of Małopolskie Voivodeship towards Poland’s energy strategy, focusing on the use of conventional or renewable energy sources. Acceptance of renewable energy was indicated in all the districts. The strongest support was found in Krakowski District (42 people), while the lowest was in Miechowski District (27 people). Therefore, similarly to the CPOR’s surveys for the entire Poland, residents of rural areas in southeastern Poland also approve of Poland’s energy transition towards renewable energy in the coming decades. This is an important observation in the context of alternative studies, as the assessment of the perception of energy policy is usually generalised and not directly related to rural residents [68].

Additionally, according to a 2024 survey report for the Roadmap to Employment after Carbon programme by UCE RESEARCH and DGA SA, nearly 46% of Poles approved of the ongoing energy transition in Poland towards greater sustainability. Still, the opinions vary significantly by age. Positive attitudes were noted among individuals aged 65–74, while negative attitudes were found in younger generations (35–44). Based on the opinions and attitudes of Poles towards the country’s energy transition, the authors of the report forecast increasing satisfaction with Poland’s participation in the process. They also pointed out an improvement in the environmental awareness of Poles. The latter are primarily convinced by the fact that an economy founded on renewable energy means stable electricity prices, which translates into tangible savings for families [81]. Similar results from the present study, involving the rural population of Małopolskie Voivodeship and their specific attitudes towards energy transition in Poland founded on different energy sources, revealed that renewable energy sources were the preferred direction. Residents of Krakowski District chose renewable energy most often (36 people), while the Wadowicki District population was the least in favour of it (24 people). These are important findings in the context of alternative, regionally generalised studies [68].

Another study confirming the strong support for renewable energy in Poland was a 2024 survey on a representative sample of adult Poles conducted by ARC Rynek and Opinia for the Polish Association of Commercial Cogeneration Plants. A staggering 80% were in favour of green energy, while 56% supported nuclear energy [82]. The present study identified moderate support for nuclear energy in rural Małopolskie Voivodeship. The largest group in favour was in Wadowicki District (22 people), while affirmative attitudes in the other four districts ranged from 11 to 15 interviewees.

Over half of the respondents in a 2024 survey of 1223 adults by SW Research, which controlled for age and size of the place of residence, believed that renewable energy sources could potentially lower electricity bills. About 34% of the respondents considered renewable energy an opportunity for the country’s economic growth, and for over 23%, renewable energy systems could stimulate regional industries [83]. This creates a new dimension of value [84]. In comparison, the present study shows that interviewees from the rural Małopolskie Voivodeship clearly associate climate action (including the expansion of renewable energy) with improved standards of living. Interestingly, only Miechowski District exhibited an age-dependent association in this regard. Respondents in this group, as they grew older, were more likely to disagree with the statement that policies to combat climate change would improve the standard of living of rural residents, which should be a point of reference for raising public awareness in the area under study.

In his research, E. Kochanek points out that the adopted sustainable energy transformation strategy for Poland is characterised by a relatively slow pace of change, while maintaining the assumed level of effectiveness [51]. These realities therefore create space for strengthening public awareness, taking into account the possibility of reaching the widest possible spectrum of Polish residents with thematic knowledge. The design of solutions in this area should be specifically tailored to the target audience, with particular emphasis on rural Poland, as evidenced by this study. These activities should be aimed at overcoming the potential reluctance to change, as emphasised, among others, by I. Lipowska et al., observed in the results of the presented study. Importantly, this reluctance is determined by age [85]. Age, as a variable that differentiates the positions presented by the respondents, provides useful information about the need to adapt the forms of communication to the recipients of information in order to provide tailored information to specific social groups.

As a final note, the valuable qualities of the countryside in Małopolskie Voivodeship are relevant here, as agritourism is a significant part of the country’s tourism industry [86]. Customers’ expectations regarding environmental friendliness, including renewable energy, are clear and may influence tourists’ consumer choices today [87,88]. This is yet another argument for investing in renewable energy systems.

6. Conclusions

The issue of Poland’s energy transition towards renewable energy will remain a priority for the country’s development for years, if not decades, to come. The literature review, including analyses of statistical reports with the latest data on the dynamics of increases in the capacity and number of renewable energy sources, confirms the direction of development of the energy system in Poland towards renewable sources. This is evidenced by two confirmed research assumptions that the transformation of the energy system in Poland towards RES is progressing and that micro-installations are an important element of this process, and that the development of micro-installations in the transformation of the Polish energy system requires further promotion and financial support in order to maintain the momentum of strengthening RES in the country’s energy system, including in rural areas in Małopolska.

Microgeneration is an important component of the renewable energy growth process. Statistics show that there were over 1.5 million microgeneration systems in Poland at the end of 2024, with 98% of these systems held by prosumers. The change in the number of new systems in recent years is particularly interesting. Specifically, there was a substantial slowdown in the increase in microgeneration systems and the amount of energy they fed back to the grid in 2024. The number of new systems declined by over four times compared to in 2023. In light of the above, Poland’s energy policy should include promotion and financial incentives to maintain the dynamics of renewable energy expansion. The above should be reinforced by a just transition process covering areas that, for various reasons, are lagging behind in implementing the necessary changes, including agricultural areas.

Decision-makers in Poland must be aware of the public’s position on the ongoing energy transition. In this regard, both regional and age-specific indications are important. According to the authors, information on the position of Polish rural residents, which creates a set of challenges for the energy transition process, is particularly important. This paper provides knowledge in this area.

Surveys conducted by the authors in rural areas of selected districts of the Małopolska Province allowed for the verification of the remaining research hypotheses, namely that the awareness of rural residents in the Małopolska region in the field of energy transition needs to be strengthened, and that the respondents’ position in this regard is determined by age.

The study demonstrates that action is needed to improve awareness regarding Poland’s energy transition among the rural population of Małopolskie Voivodeship. The educational effort should take into account the various levels of knowledge and the diversity of attitudes towards energy transition among different age groups. Therefore, it is necessary to adapt channels and content to the target age. The effective implementation of state energy policy, including in rural areas, depends on the local population’s knowledge. Considering the above assumptions, it is crucial to take comprehensive promotional and educational measures to support Poland’s energy transition towards renewable energy, reaching the largest possible audience across each age group. A lack of effective action in this area could significantly slow down the pace and effectiveness of the transformation, which would ultimately affect the development of the entire country. This leads to the conclusion that raising public awareness of green technologies may result in increased interest in green technologies and intensified efforts to support the energy transition.

Promoting green energy is central to the effective energy transition in Poland. Consequently, the results aim to complement the existing literature with recent data. Decision-makers can utilise them to devise educational policies aimed at promoting renewable energy awareness and to model support schemes for implementing renewable energy sources in socioeconomic practice, particularly in rural areas.

The presented research results have the potential for further exploration through analysis of specific government actions in the field of public education and financing energy solutions dedicated to prosumers. Of particular interest in this area may be activities targeting rural areas in Poland, where the potential for such activities has been identified and confirmed in this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.C.-P., M.K. and K.C.; Methodology, E.C.-P. and M.K.; Validation, K.C.; Formal analysis, E.C.-P., M.K. and K.C.; Resources, M.K. and K.C.; Writing—original draft, E.C.-P. and M.K.; Writing—review & editing, E.C.-P. and K.C.; Visualization, E.C.-P.; Supervision, E.C.-P. and M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Economic, Environmental and Social Security in accordance with the Concept of Sustainable Development. Stud. Adm. Bezpieczeństwa 2025, 18, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kęsy, I.; Godawa, S.; Błaszczak, B.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Human Safety in Light of the Economic, Social and Environmental Aspects of Sustainable Development—Determination of the Awareness of the Young Generation in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardaś, S. Od Węgla do Konsensusu: Wyzwania i Perspektywy Transformacji Energetycznej Polski; Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, E.; Cole, W.; Frew, B. Valuing variable renewable energy for peak demand requirements. Energy 2018, 165, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MISTRA Report. Carbon Exit. The Swedish Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research (Mistra). 2023. Sveden. Available online: https://mistra.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Annual-Report-2023-Carbon-Exit.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Aid, R.; Pang, X.; Tan, X. Exit Incentives for Carbon Emissive Firms. 2025. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5244706 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Zink, J. Which investors support the transition toward a low-carbon economy? Exit and Voice in mutual funds. J. Asset. Manag. 2024, 25, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firtescu, B.N.; Bostan, I.; Grosu, M.; Droj, L.; Mihalciuc, C.C. Increasing the share of renewable energy sources (RESs) in the specific portfolio by using the taxation mechanism: Study at the level of EU states. Econ. Anal. Policy 2025, 85, 1534–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Theme Report on Energy Transition Towards the Achievement of SDG 7 and NET-Zero Emissions. 2021. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021-twg_2-062321.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Zeng, Q.; Li, C.; Magazzino, C. 2024. Impact of green energy production for sustainable economic growth and green economic recovery. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, T.L.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. Strategies to make renewable energy sources compatible with economic growth. Energy Strategy Rev. 2017, 18, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guliyev, H.; Tatoğlu, F.Y. The relationship between renewable energy and economic growth in European countries: Evidence from panel data model with sharp and smooth changes. Renew. Energy Focus 2023, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firlej, K.A.; Mierzejewski, M.; Stanuch, M. Economic Growth in the European Union: The Importance of Renewable Energy Consumption. Ann. Univ. Mariae Curie-Skłodowska Lub. Pol. 2024, 58, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Innovation as an Attribute of the Sustainable Development of Pharmaceutical Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy. Database Documentation. 2022. International Energy Agency. IEA, Paris. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/f535fcce-abe8-49ff-9cc9-5c1d9d6eec07/WORLD_GHG_Documentation.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Sakata, S.; Aklilu, A.Z.; Pizarro, R. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data: Concepts and Data Availability; OECD Statistics Working Papers; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, C.; Treyer, K.; Heck, T.; Hirschberg, S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Systems, Comparison, and Overview, Reference Module in Earth Systems and Environmental Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backović, N.; Ilić, B.; Radaković, J.A.; Mitrović, D.; Milenković, N.; Ćirović, M.; Rakićević, Z.; Petrović, N. Towards 2050: Evaluating the Role of Energy Transformation for Sustainable Energy Growth in Serbia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroń, A.; Borucka, A. Analysis of Energy System Transformations in the European Union. Energies 2024, 17, 6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusin, A.; Wojaczek, A. Safe Path for the Transformation of the Polish Energy System Leading to Its Decarbonization and Reliable Operation. Energies 2025, 18, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. A New World The Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation. In Global Commission on the Geopolitics of Energy Transformation; International Renewable Energy Agency: Masdar City, Abu Dhabi, 2019; ISBN 978-92-9260-097-6. [Google Scholar]

- Envall, F.; Rohracher, H. Technopolitics of future-making: The ambiguous role of energy communities in shaping energy system change. Environ. Plan. E Nat. Space 2023, 7, 765–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgan, J.D.; Hinthorn, M. International Energy Politics in an Age of Climate Change. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2023, 26, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.J. The global politics of the renewable energy transition and the non-substitutability hypothesis: Towards a ‘great transformation’? Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2022, 29, 1766–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/energy/#:~:text=Goal%207%20is%20about%20ensuring,targets%20%E2%80%93%20but%20not%20fast%20enough (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Lotze, J.; Moser, M.; Sittaro, P.; Sun, N. Energy System 2050—Towards a decarbonised Europe; Transnet BW: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Pastore, L.M.; de Santoli, L. 100% renewable energy Italy: A vision to achieve full energy system decarbonisation by 2050. Energy 2025, 317, 134749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenk, G.; Meier, R.; Reichelstein, S. Cost Dynamics of Clean Energy Technologies. Schmalenbach J. Bus Res. 2021, 73, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhoff, K.; May, N.; Richstein, J.C. Financing renewables in the age of falling technology costs. Resour. Energy Econ. 2022, 70, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheatley, M.C. Advancements in Renewable Energy Technologies: A Decade in Review. Prem. J. Sci. 2024, 1, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñeiro, T.B.; Müsgens, F. Pay-back time: Increasing electricity prices and decreasing costs make renewable energy competitive. Energy Policy 2025, 199, 114523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy from Renewable Sources in 2023, Report Statistics Poland. 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/environment-energy/energy/energy-from-renewable-sources-in-2023,9,3.html (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Europeane Parliament: Renewable Energy: Setting Ambitious Targets for Europe. 2024. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20171124STO88813/renewable-energy-setting-ambitious-targets-for-europe (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- European Environment Agency, Share of Energy Consumption from Renewable Sources in Europe. 2025. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/share-of-energy-consumption-from (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Relich, M. Renewable Energy in the European Union: The State of the Art and Directions of Development. WSEAS Trans. Bus. Econ. 2024, 21, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taušová, M.; Mykhei, M.; Culkova, K.; Tauš, P.; Petráš, D.; Kanuch, 2025. Development of the Implementation of Renewable Sources in EU Countries in Heating and Cooling, Transport, and Electricity. Sustainability 2025, 17, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plan REPowerEU 2022. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. European Commission. Brussels. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0230 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Zetterberg, L.; Johnsson, F.; Elkerbout, M. Impacts of the Russian Invasion of Ukraine on the Planned Green Transformation in Europe. IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, 2 Chalmers University of Technology. 2022. 3 Centre for European Policy Studies. Available online: https://www.ivl.se/download/18.147c3211181202f18d11ca4e/1657867472879/Ukraine%20PolicyBrief_6%20July%202022.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- European Commission. Commission Proposes Gradual Phase-Out of Russian Gas and Oil Imports into the EU. 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_25_1504 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Bäckstrand, K. Towards a Climate-Neutral Union by 2050? The European Green Deal, Climate Law, and Green Recovery. In Routes to a Resilient European Union; Bakardjieva Engelbrekt, A., Ekman, P., Michalski, A., Oxelheim, L., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douša, M. Sustainable environment futures: European green deal striving to be the first climate-neutral continent. Veřejná Správa A Sociální Polit. 2024, 4, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rządkowska, A.E. Quantitatively estimating the impact of the European Green Deal on the clean energy transformation in the European Union with a focus on the breakthrough of the share of renewable energy in the electricity generation sector. Polityka Energetyczna–Energy Policy J. 2022, 25, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarczyk, B.; Lis, K.; Bogucka, A. Renewable Energy Management in European Union Member States. Energies 2023, 16, 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevičius, R.; Noga, G.; Petraškevičius, V.; Žemaitis, E.; Novotný, M. Assessing Renewable Energy Growth in the European Union. Energies 2025, 18, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Renewable Energy Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Renewable_energy_statistics#Share_of_renewable_energy_more_than_doubled_between_2004_and_2020 (accessed on 18 July 2025).

- Kostecka-Jurczyk, D.; Marak, K.; Struś, M. Economic Conditions for the Development of Energy Cooperatives in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicki, L.; Pietrzykowski, R.; Kusz, D. Factors Determining the Development of Prosumer Photovoltaic Installations in Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleszek, M.; Witorożec-Piechnik, A.; Radzikowski, P.; Matyka, M. Current Status and Prospects for the Develop-ment of Renewable Energy Sources in the Agricultural Sector in Poland. Energies 2025, 18, 4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocur-Bera, K. Are Local Commune Governments Interested in the Development of Photovoltaics in Their Area? An Inside View of Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardal, W.J.; Mazur, K.; Barwicki, J.; Tseyko, M. Fundamental Barriers to Green Energy Production in Selected EU Countries. Energies 2024, 17, 3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanek, E. Evaluation of Energy Transition Scenarios in Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 6058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Energy–Environment–Industry Intersection: Rural and Urban Inequity and Approach to Just Transition. Land 2025, 14, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Baležentis, T.; Volkov, A.; Morkūnas, M.; Žičkienė, A.; Streimikis, J. Barriers and Drivers of Renewable Energy Pen Soussi, A.; Zero, E.; Bozzi, A.; Sacile, R. Enhancing Energy Systems and Rural Communities through a System of Systems Approach: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2024, 17, 4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Wang, S. Energy Transition Consumption, Climate Risk Regulation and Economic Well-Being of Rural Households. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, W. Rural Residents’ Willingness to Adopt Energy-Saving Technology for Buildings and Their Behavioral Response Path. Buildings 2024, 14, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozera, A.; Standar, A.; Stanisławska, J.; Rosa, A. Investments in Renewable Energy in Rural Communes: An Anal-ysis of Regional Disparities in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Sustainable Development Through the Lens of Climate Change: A Diagnosis of Attitudes in Southeastern Rural Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raport The EIB Climate Survey. Citizens Call for Green Recovery; European Investment Bank: Luxembourg, 2022.

- Krajowy Plan na Rzecz Energii i Klimatu na Lata 2021–2030. Założenia i Cele oraz Polityki i Działania; Ministerstwo Aktywów Państwowych: Warszawa, Poland, 2019.

- Michalik, S.; Zieliński, D. Transformacja Energetyczna w Polsce w Świetle Strategicznych Dokumentów Rządowych; Sieć Badawcza Łukasiewicz—ITECH Instytut Innowacji i Technologii: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Energia ze źródeł odnawialnych w 2023 r; Urząd Statystyczny: Rzeszów, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Raport URE: W Polsce Działa Już 1,5 mln Mikroinstalacji OZE. 2025. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/urzad/informacje-ogolne/aktualnosci/12551,Raport-URE-w-Polsce-dziala-juz-15-mln-mikroinstalacji-OZE.html (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Ministerstwo Klimatu i Środowiska, Prosument, Serwis Informacyjno—Edukacyjny MKiŚ. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/prosument (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Małe Instalacje OZE. 2025. Available online: https://www.biznes.gov.pl/pl/portal/ou820 (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Raport URE: W 2024 r. w Małych Instalacjach OZE Wyprodukowano Niemal 4,8 TWh Energii. 2025. Available online: https://www.ure.gov.pl/pl/urzad/informacje-ogolne/aktualnosci/12642,Raport-URE-w-2024-r-w-malych-instalacjach-OZE-wyprodukowano-niemal-48-TWh-energi.html# (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Regionalny Plan Działań dla Klimatu i Energii dla Województwa Małopolskiego. Sprawozdanie za 2022 Rok; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Małopolskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2023.

- Eurostat, Greenhouse Gas Emission Footprints 2025. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/SEPDF/cache/133231.pdf#:~:text=%22%20In%202022%2C%20the%20EU's%20greenhouse%20gas,to%20consumption%20anywhere%20in%20the%20world.%20%22 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- GUS. Wskaźniki Zielonej Gospodarki w Polsce 2024; Analizy Statystyczne: Warszawa, Poland; Białystok, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raport z wykonania Programu Strategicznego Ochrona Środowiska Województwa Małopolskiego za lata 2022–2023, Załącznik do Uchwały Nr 66/25Zarządu Województwa Małopolskiego z Dnia 14 Stycznia 2025 r; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Małopolskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2025.

- Welcher, A. Małopolskie Przedsiębiorstwa w Dobie Transformacji Energetycznej; Województwo Małopolskie Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Małopolskiego Departament Rozwoju Regionu Małopolskie Obserwatorium Rozwoju Regionalnego: Kraków, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- EkoMałopolska, Potencjał OZE. 2023. Available online: https://klimat.ekomalopolska.pl/potencjal-oze/ (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- GUS Energia 2024. Rzeszów. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/srodowisko-energia/energia/energia-2024,1,12.html (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Klimat, Ekomałopolska. Available online: https://klimat.ekomalopolska.pl/inicjatywy/regionalny-plan-dzialan-dla-klimatu-i-energii/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Fundusze Europejskie dla Małopolski. 2025. Available online: https://fundusze.malopolska.pl/nabory/11675-dzialanie-811-transformacja-energetyczna-typ-projektu-i-typ-projektu-b (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Drożdż, W.; Mróz-Malik, O.; Kopiczko, M. The Future of the Polish Energy Mix in the Context of Social Expecta-tions. Energies 2021, 14, 5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupok, S.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E.; Dmowski, A.; Dyrka, S.; Hordyj, A. A Review of Key Factors Shaping the Development of the U.S. Wind Energy Market in the Context of Contemporary Challenges. Energies 2025, 18, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PBS. Badanie Opinii Konsumentów Energii–, Energia UREgulowana; Agencja Badawcza PBS Sp. z o.o.: Sopot, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. Transformacja Energetyczna—Oczekiwania i Postulaty. Nr 70/2021; Centrum Badani Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2021; ISSN 2353-5822. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. Postawy Wobec Transformacji Energetycznej. Nr 30/2023; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; ISSN 2353-5822. [Google Scholar]

- CBOS. Opinia Publiczna o Polityce Energetycznej. Nr 56/2024; Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; ISSN 2353-5822. [Google Scholar]

- UCE/DGA. Droga do Zatrudnienia po Węglu; UCE RESEARCH: London, UK; DGA S.A.: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- PTEZ. Mądry Polak po Fake’u. Polskie Towarzystwo Elektrociepłowni Zawodowych; ARC Rynek: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raport SW Research. 2024. ECO BAROMETR VI edycja. Warszawa. Available online: https://ekobarometr.pl/ekobarometr-6 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Chomać-Pierzecka, E. Value as an economic category in the light of the multidimensionality of the concept ‘value’. Lang. Relig. Identity 2021, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipowska, I.; Lipowski, M.; Dudek, D.; Mącik, R. Switching Behavior in the Polish Energy Market—The Importance of Resistance to Change. Energies 2024, 17, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MSiT. Raport na Temat Podaży Turystyki Wiejskiej po Pandemii COVID-19, Warszawa 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/attachment/ee76b3d3-3355-43f8-bfbd-133eaacdf3a3 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Sobczak, A.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. The Impact of Measures Related to the Sustainable Development of the Tourism Sector in Poland on Tourists’ Opinions. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. ICSIMAT 2024; Kavoura, A., Briciu, V.A., Briciu, A., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, A.; Chomać-Pierzecka, E. The Role of Sustainable Tourism in Local Development. In Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism. ICSIMAT 2024; Kavoura, A., Briciu, V.A., Briciu, A., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).