Abstract

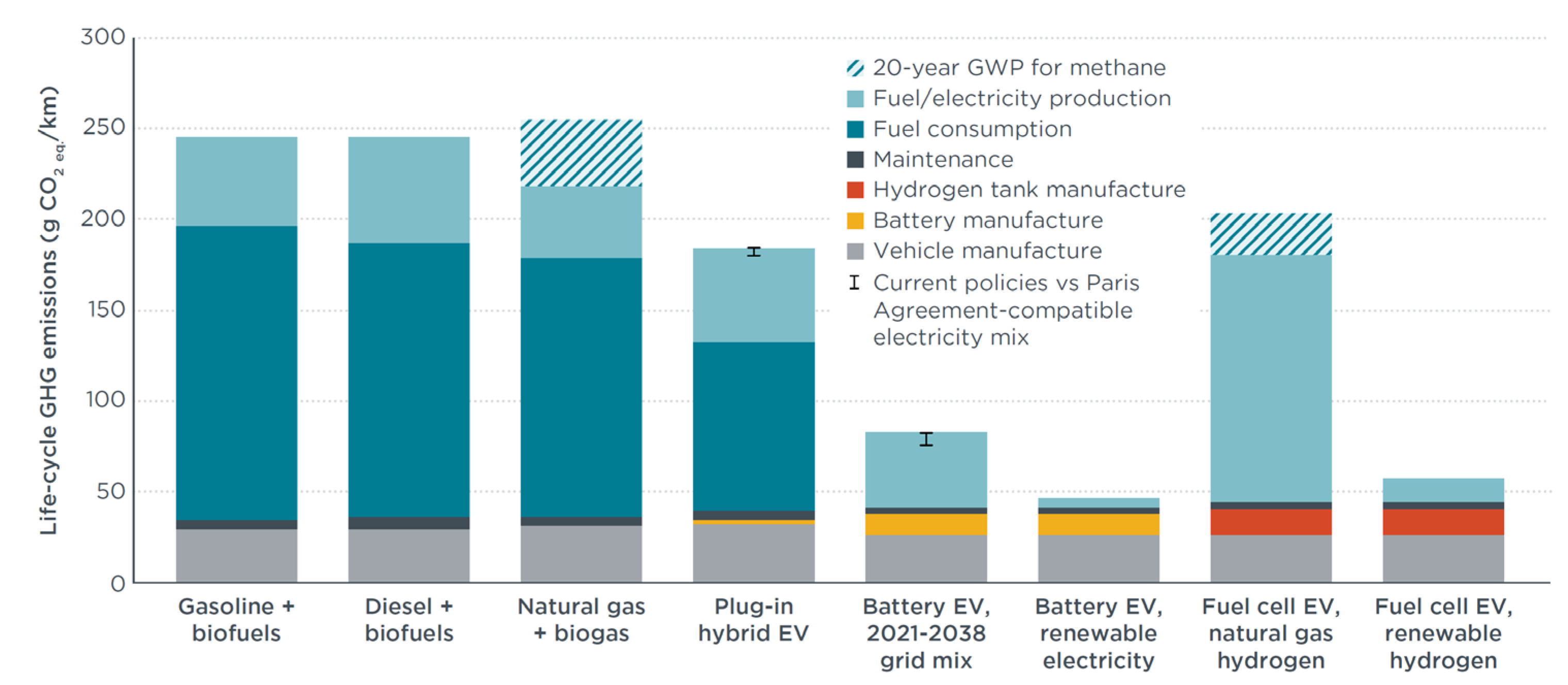

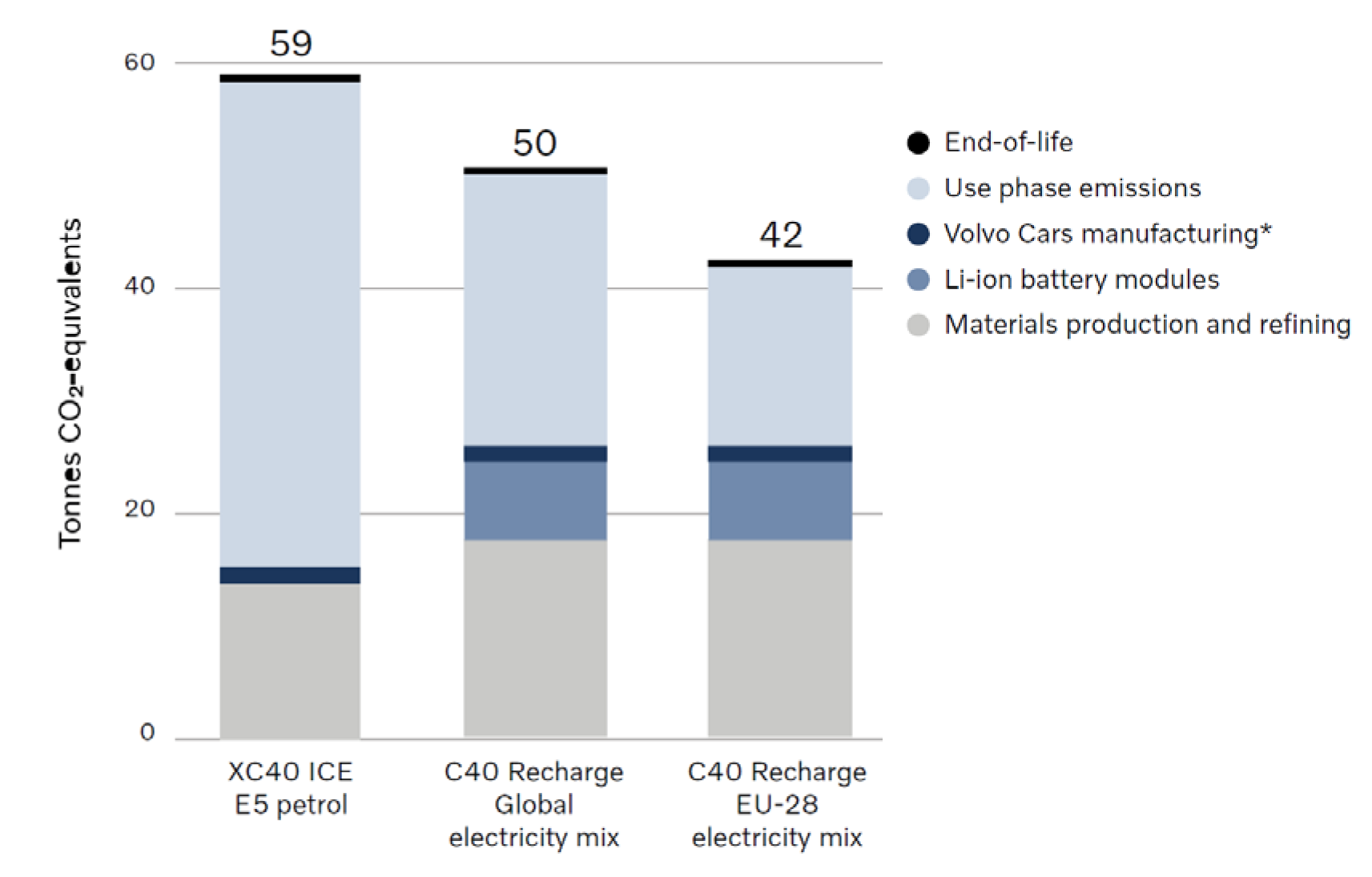

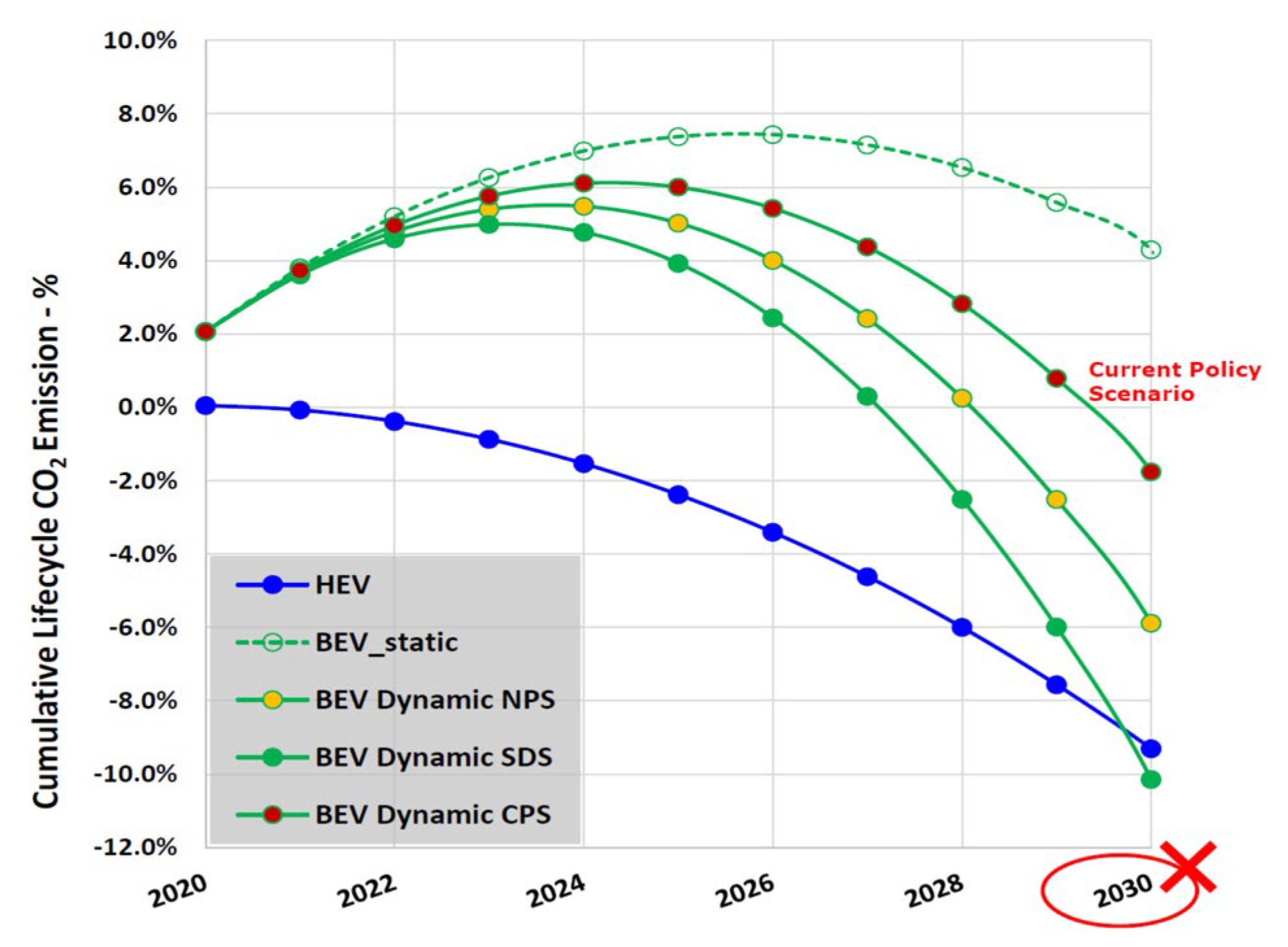

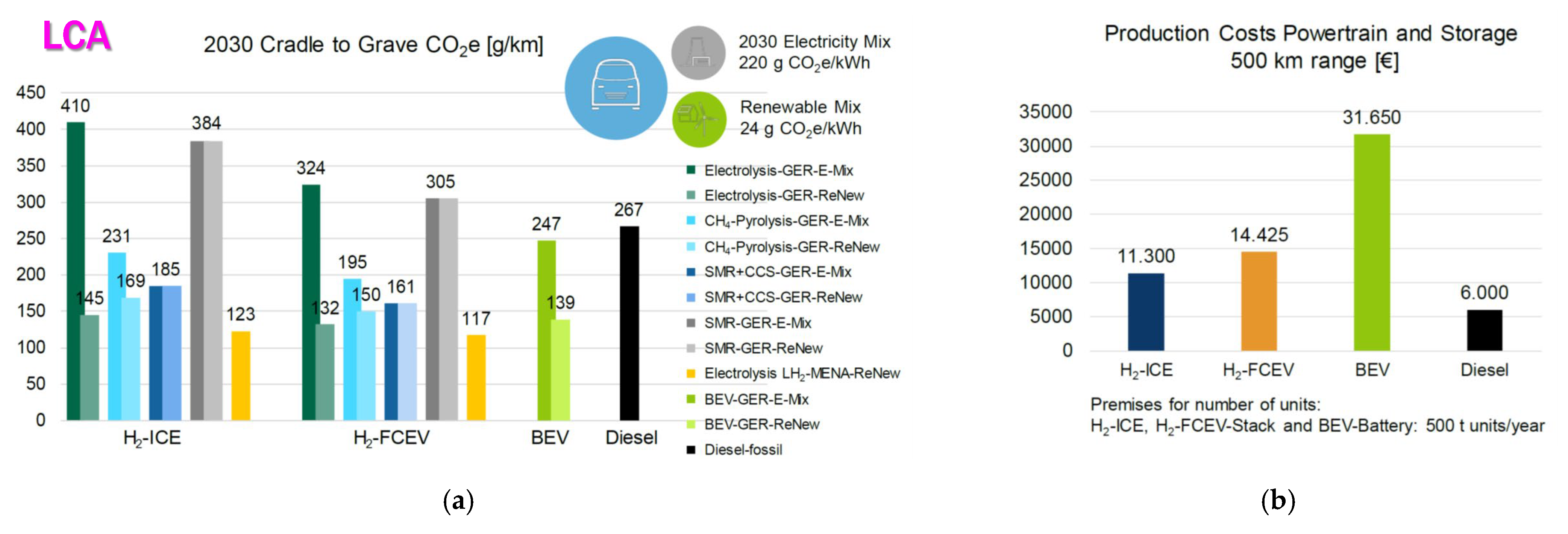

An overview of the Common Rail (CR) diesel engine challenges and of the promising state-of-the-art solutions for addressing them is provided. The different CR injector driving technologies have been compared, based on hydraulic, spray and engine performance for conventional diesel combustion. Various injection patterns, high injection pressures and nozzle design features are analyzed with reference to their advantages and disadvantages in addressing engine issues. The benefits of the statistically optimized engine calibrations have also been examined. With regard to the combustion strategy, the role of a CR engine in the implementation of low-temperature combustion (LTC) is reviewed, and the effect of the ECU calibration parameters of the injection on LTC steady-state and transition modes, as well as on an LTC domain, is illustrated. Moreover, the exploitation of LTC in the last generation of CR engines is discussed. The CR apparatus offers flexibility to optimize the engine calibration even for biofuels and e-fuels, which has gained interest in the last decade. The impact of the injection strategy on spray, ignition and combustion is discussed with reference to fuel consumption and emissions for both biodiesel and green diesel. Finally, the electrification of CR diesel engines is reviewed: the effects of electrically heated catalysts, electric supercharging, start and stop functionality and electrical auxiliaries on NOx, CO2, consumption and torque are analyzed. The feasibility of mild hybrid, strong hybrid and plug-in CR diesel powertrains is discussed. For the future, based on life cycle and manufacturing cost analyses, a roadmap for the automotive sector is outlined, highlighting the perspectives of the CR diesel engine for different applications.

1. Introduction

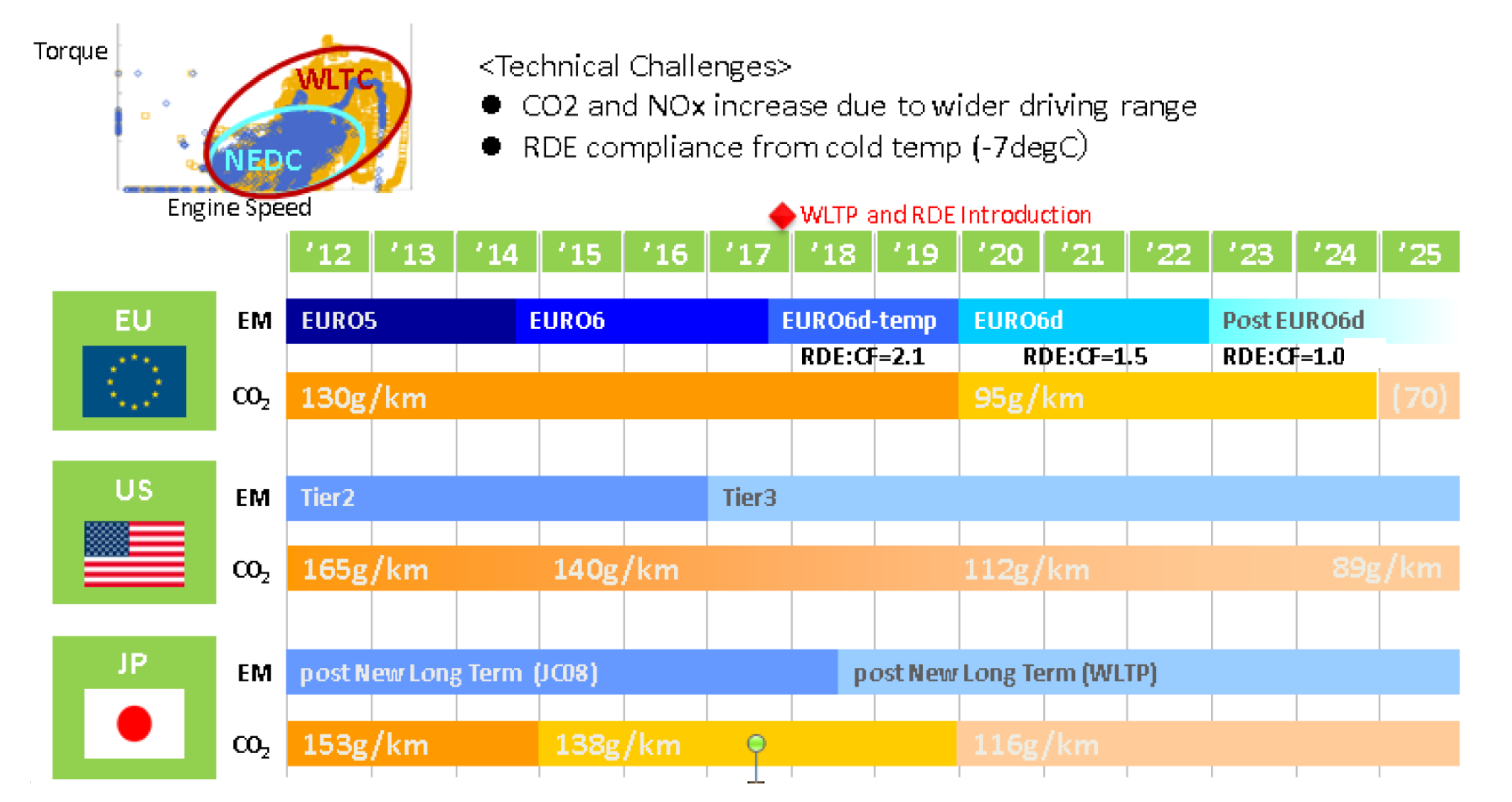

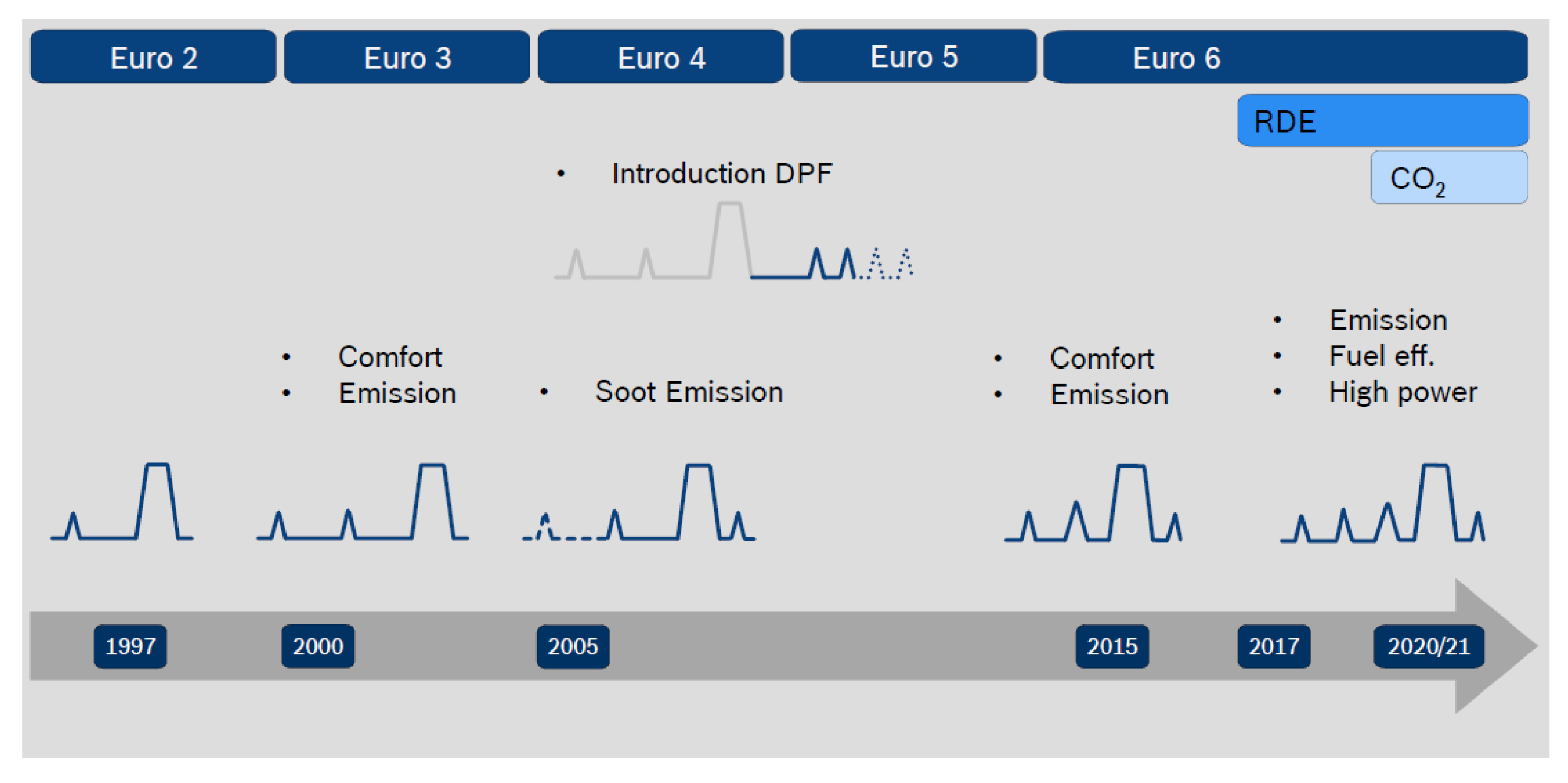

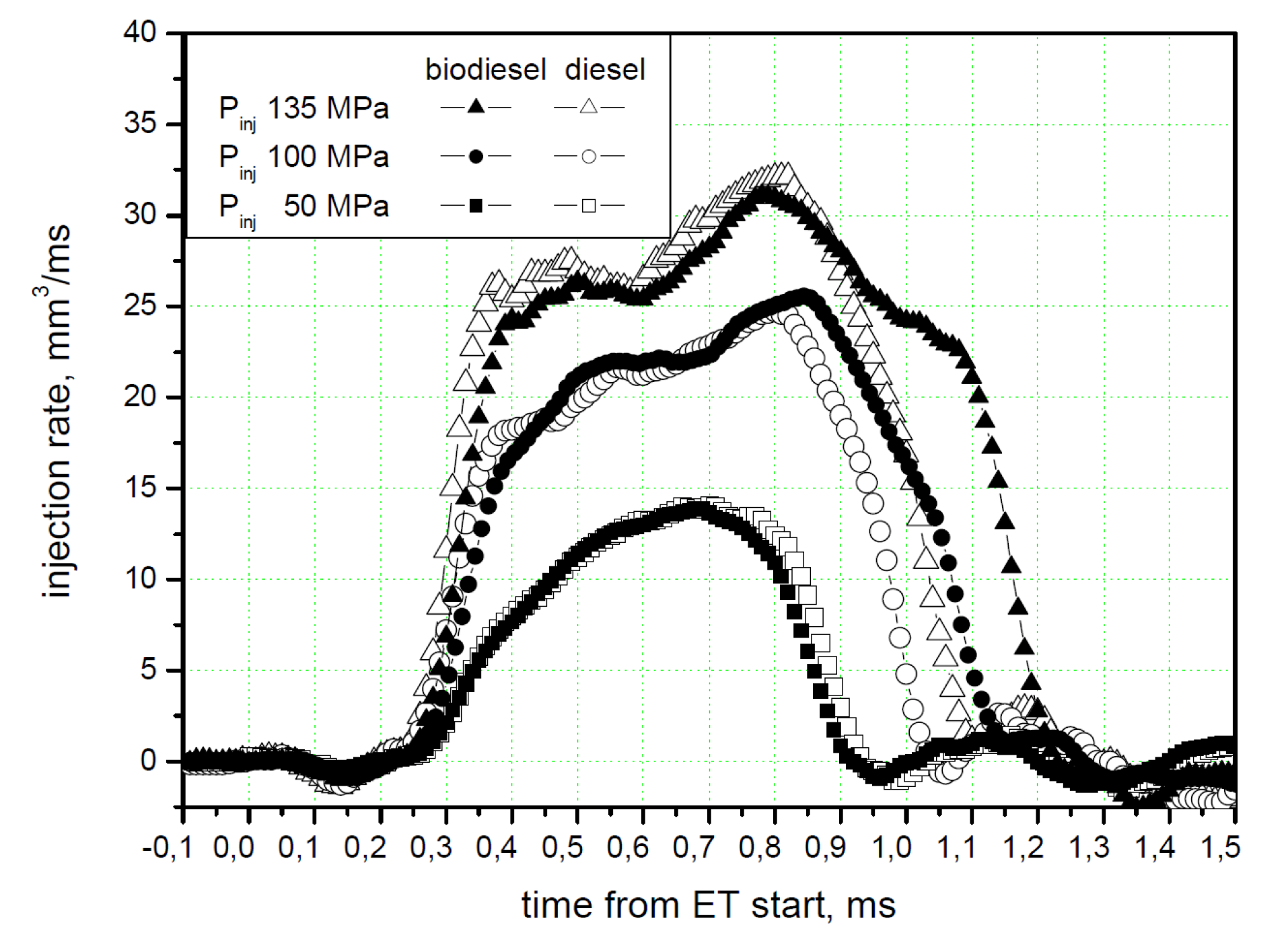

The combustion processes that take place inside a compression ignited (CI) engine are essentially dependent on the way in which the fuel is injected into the combustion chamber. The most important criteria to characterize and evaluate an injection event are the timing and the duration of injection and their variations with respect to the engine working conditions, the degree of atomization, the penetration and the scattering or diffusion of the injected fuel inside the combustion chamber, the injected mass flow rate pattern with respect to the crankshaft angle and the total amount of fuel injected related to the engine load.

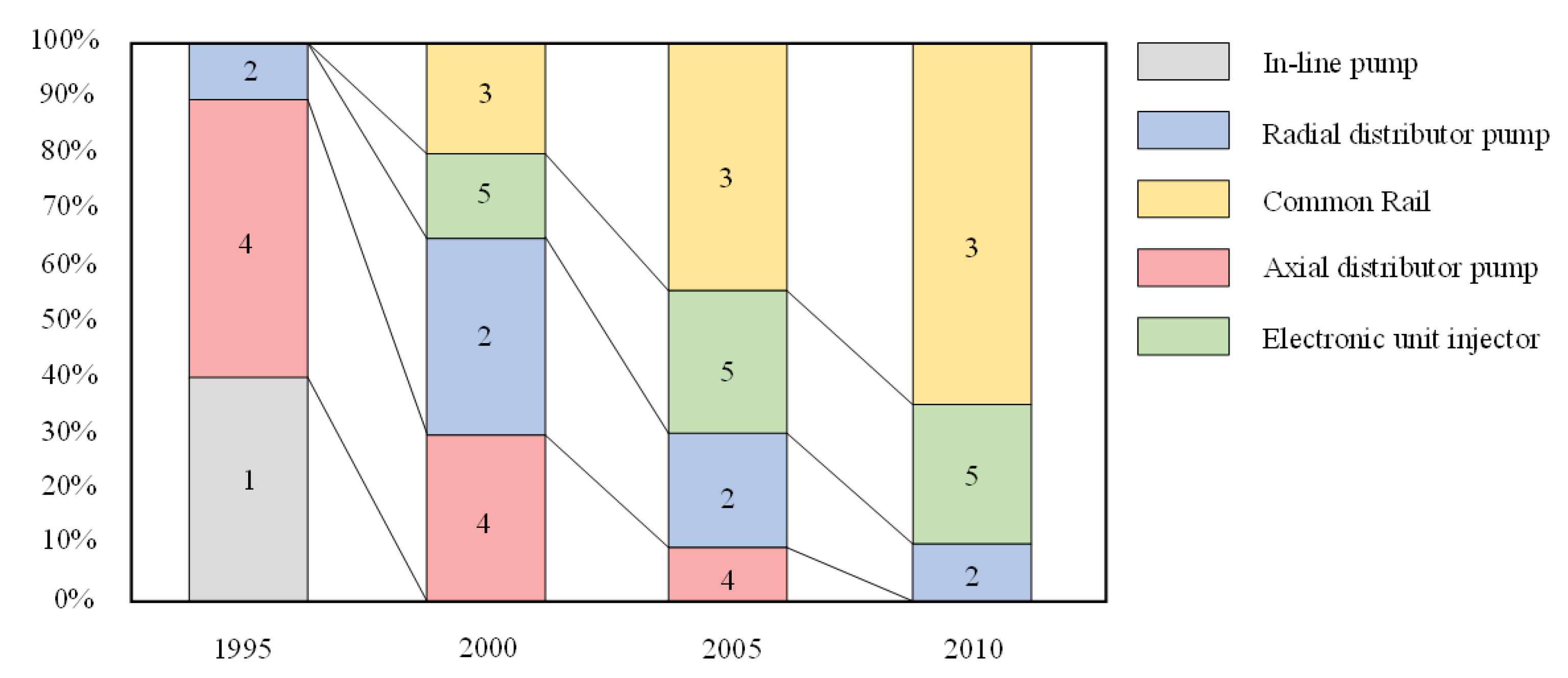

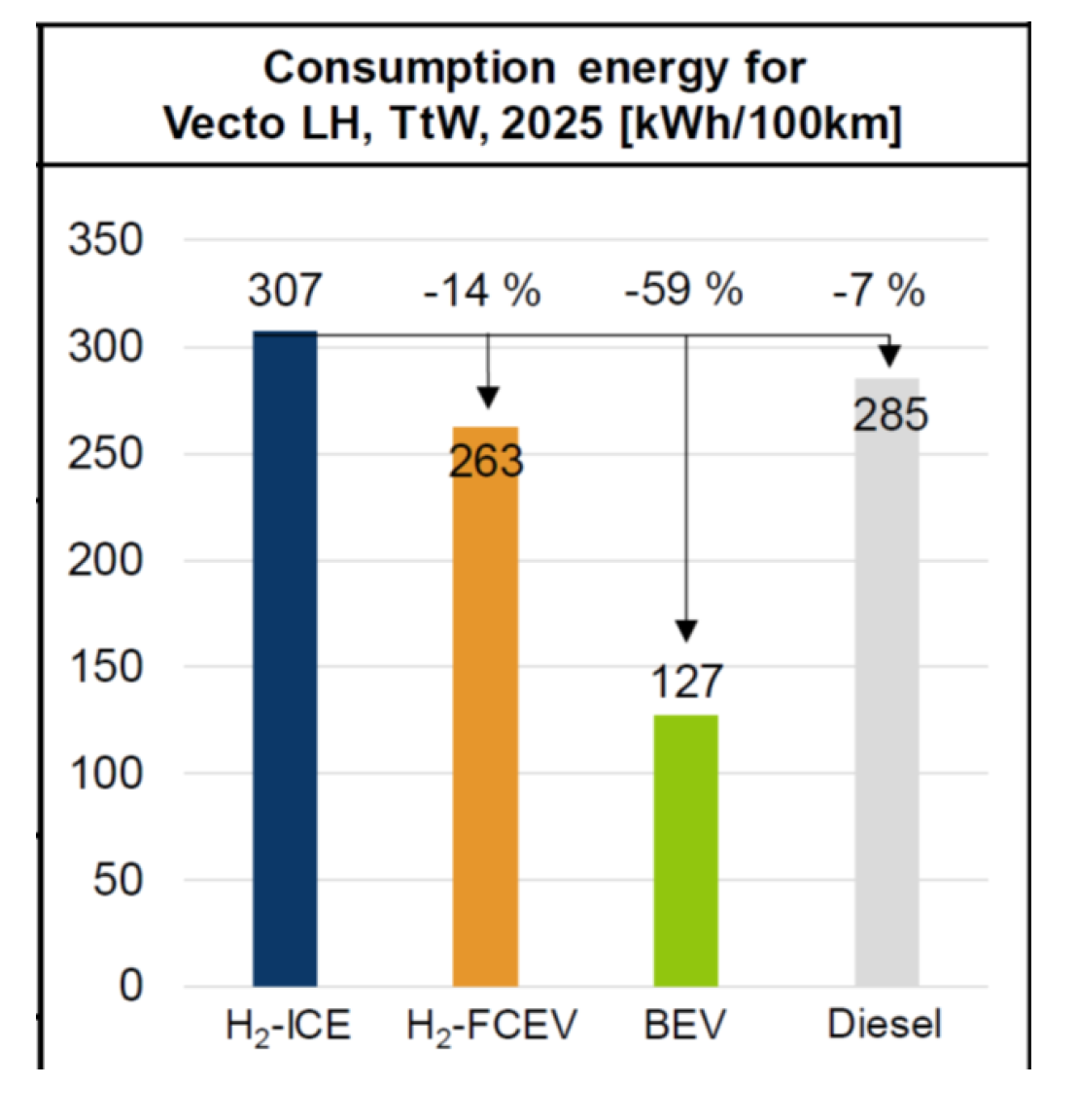

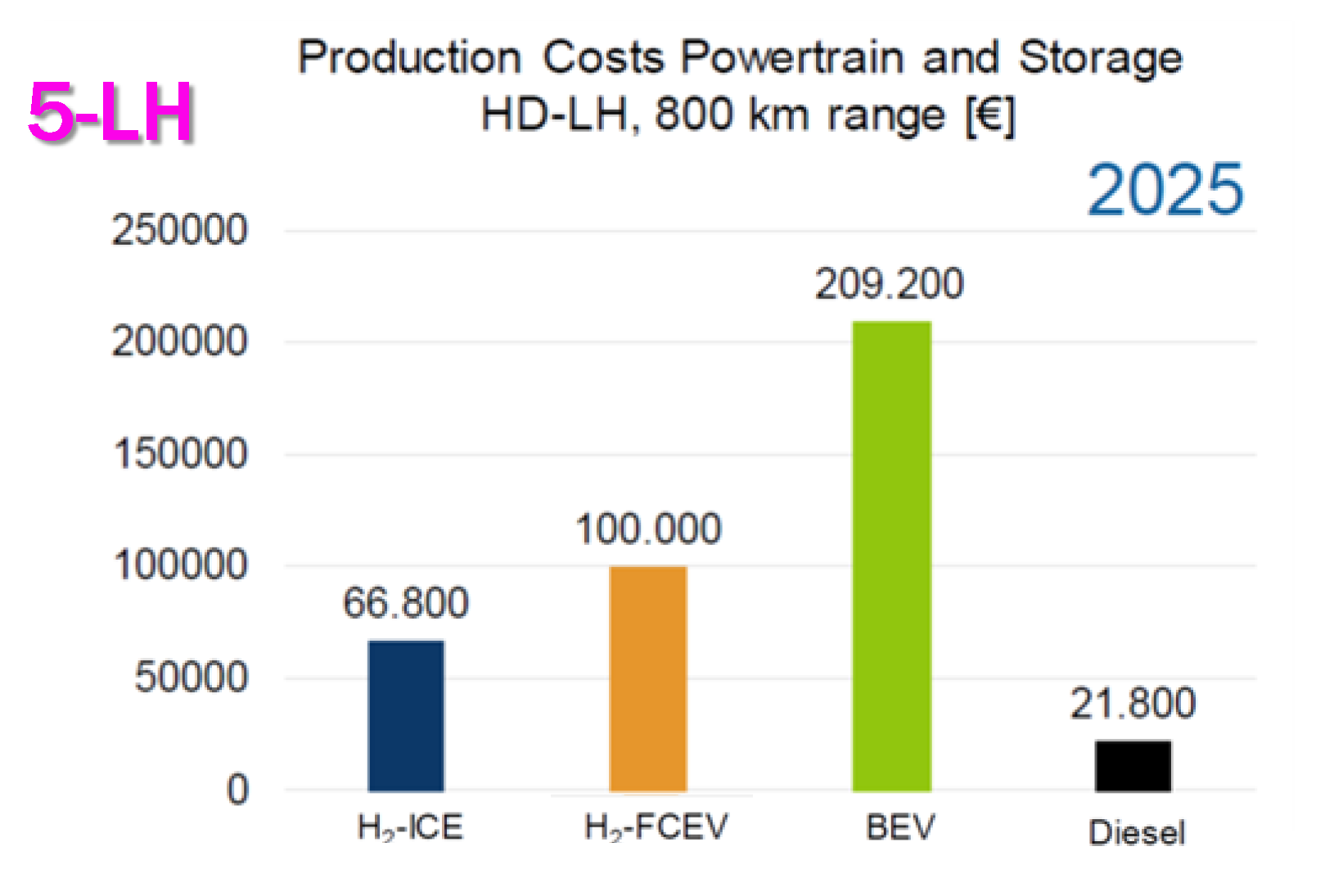

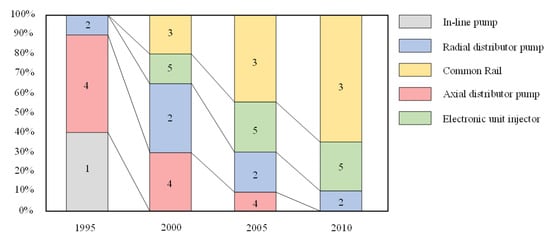

Different fuel injection system technologies have been employed in traction systems for obtaining the planned objectives. Figure 1 reports the European, US and Japan automotive market of popular injection systems in the period from 1995 to 2010: 1 is the in-line pump, 2 is the radial distributor injection pump, 3 is the CR, 4 is the axial distributor injection pump and 5 is the electronic unit injector (EUI). The introduction of more stringent emission standards during the late 1990s and the early 2000s in Europe, the USA and Japan required a new evolution of injection system technologies applied to direct-injection diesel engines. Injection timing delay had been the primary means by which NOx emissions were reduced up until the late 1990s, and the available electronically controlled fuel injection pumps could guarantee improved flexibility in the management of SOIs, compared to previous mechanical systems. However, there was a practical limit to injection timing delays due to an excessive increase in soot and HC increase or due to misfire [1]. The EGR fractions backing into the cylinder had been modest up to the late 1990s for both passenger cars and trucks, but higher demands on EGR systems were created with the emission standards introduced in the early 2000s, which triggered the introduction of sophisticated electronically controlled cooled EGR systems. Since either injection timing delays or EGR increases worsened soot emissions, an augmentation in the injection pressure or in the swirl level within the cylinder was essential to contain the PM. Larger injection pressures, combined with higher compression ratios, could also decrease the fuel economy penalty associated with delayed injection timings because they significantly reduced ignition delays [2]. Furthermore, an augment in the injection pressure allowed the rotational speed of a diesel engine to be increased because the raised injection pressure accelerated fuel evaporation and thus the combustion process. Finally, with high injection pressures, air swirl could be reduced, and this in turn diminished both the energy consumed in producing swirl and the heat loss to the coolant. In-line pumps and axial-piston fuel distributor pumps for passenger cars could not go beyond 550 bar and 700 bar, respectively, and these injection pressures could only be reached at high loads and speeds; for heavy-duty engines, the maximum injection pressures for these two injection systems could reach 1150 bar and 1300 bar, respectively. Electronically radial fuel distributor pumps and electronic unit pump systems were introduced in the mid-1990s and were able to provide a maximum pressure of 1500 bar for car applications and beyond for heavy-duty applications. However, both these systems enabled only simplified pilot–main injection patterns, due to the presence of significant lag and residual pressure wave dynamics along the long pump-to-injector piping system after the end of the injection. Instead, the EUI allowed for injection pressure levels to be raised up to 2000 bar [3,4,5] because of its reduced hydraulic capacitance, which was caused by the small high-pressure circuit volume between the pumping plunger and nozzle, and allowed multiple injections to be performed. From the late 1990s to the late 2000s, the EUI was the technology competing with the CR for application to diesel passenger cars and diesel light-duty commercial vehicles, although the final success of the CR system was unavoidable. This was primarily due to its general superior flexibility in the management of the injection train parameters in order to adapt combustion to the demands of the engine operating points in terms of performance, pollutant emissions and noise [6]. CR systems allow for flexible control of the injection pressure, independently of load, speed and injection hole diameter, whereas the injection pressure was affected by the cam profile, the working condition and the hole diameter in EUI systems. Another fundamental difference of the CR system compared to EUI systems is the constant fuel pressure at the nozzle during the injection period. In addition to this, although EUI systems are characterized by limited combustion noise, they generate much more mechanical noise than CR systems, due to the mechanical contact between the cam, rocker-arm and follower. It has been proved in [7] that any modification in the EUI system design leading to a higher injection pressure and to steeper pressure gradients in the plunger cavity induces an increase in the mechanical noise and vice versa. This trade-off between mechanical noise and hydraulic performance represented a dramatic and unsolved dilemma of the EUI. Furthermore, EUI systems could not perform more than three shots per engine cycle because only the central portion of the pumping plunger stroke could be exploited for programming injections [8]. The implementation of multiple injections with reduced dwell time between the subsequent shots was another challenge for the EUI. In fact, the key to performing multiple injections with reduced dwell time resides in the two-stage layout of the CR injector (pilot stage and main stage): among all the examined fuel injection systems, the CR injector is the only one equipped with an integrated pilot valve. Finally, the introduction of the diesel particulate filters for limiting PM required efficient regeneration strategies. One of the simplest strategies consisted of the application of one or more shots close to exhaust valve opening [9]: this was an easy solution for the CR but was not practicable for the EUI [10,11]. Since 2010, CR systems have practically become the only universally applied injection technology for passenger cars and light-duty commercial diesel vehicles: they progressively spread even in the fields of trucks, tractors and off-road vehicles for reasons related to scale economy. During the early 2010s, the diesel engine passenger cars sold in Europe were able to overcome those fueled by gasoline, and the diesel engine appeared as the primary resource to satisfy the progressively stringent fleet-wide targets on CO2 for passenger cars, established as a mandatory regulation in Europe since 2009. Furthermore, the Paris Agreement that was drawn up during the Conference of the Parties in 2015 (COP21), the European Green Deal and the outcomes of the COP26 held in Glasgow in 2021 affirmed the ambition to limit global warming to below 1.5 °C, compared to pre-industrial levels, and to achieve carbon neutrality by around 2050. These events, in conjunction with the effects of the Dieselgate scandal, increased attention on climate changes and on CO2 vehicular emissions. Hence, after a first phase from the late 1990s up to Dieselgate, in which both pollutant criteria and performance (especially power density and combustion noise) mainly guided the design of the CR diesel engine, a second phase started, ongoing since 2016, in which CR engine development for automotive applications has been primarily conducted with new pollutant criteria, which include both laboratory emission cycles and real driving emission (RDE) tests conducted on public roads with the application of conformity factors, and based on CO2 targets. The decision of the European community in 2019 (Europan regulations 2019/631 and 2019/1242) to reduce the average CO2 emissions of passenger car fleets by 37.5% in 2030 compared to the levels in 2021, the average CO2 emissions of light-duty commercial vehicle fleets by 31% compared to the levels in 2021 and those of heavy-duty commercial vehicles by 30% (the last target has been updated to 45% in 2024 with European Regulation 2024/1610) compared to 2020 (there are also mandatory short-term targets for all types of vehicles to reduce CO2 emissions by 15% in 2025–2027 compared to either 2021 or 2020, depending on the vehicle type) has encouraged the development of electrification as well as the use of alternative fuels in diesel engines. Figure 2 reports recent pollutant emissions standards as well as CO2 targets in the EU, the US and Japan: it is impressive how the CO2 limits have become stricter in recent years (values on the figure refer to NEDC).

Figure 1.

Penetration of the different injection systems on the market.

Figure 2.

Emission standards and CO2 targets.

The current historical period, which is characterized by a slowdown in the technological progress of CR engines after almost 25 years of convulsive development, is suitable for performing a balance of such an engine breakthrough and to provide a possible scenario for the future of CI combustion engines. The present work assesses the CR system potentialities in the efficient design of conventional and innovative CI combustion concepts as well as in the management of biofuels and e-fuels. The state of the art of electrification in CR diesel engines is provided, and feasible solutions for sustainable on-road mobility are discussed. An original aspect of this review is related to the simultaneous treatment of conventional and innovative combustion concepts, alternative fuels and electrification, which depicts an exhaustive scenario of CR applications and opens up the discussion to cross-correlations between the topics.

2. Fuel Injection Technologies and Conventional Diesel Combustion

2.1. Comparison Between Solenoid and Piezoelectric CR Engines

CR injection system technologies developed for conventional diesel combustion, which consists of an initial reduced premixed phase (about 30% of the fuel heat release) and of a subsequent predominant diffusive phase (about 70% of fuel het release), have been of two types, solenoidal or piezoelectric technology, depending on the driving system (either a solenoid or a piezo stack) used to actuate the two-stage injector. Two-stage piezoelectric CR injectors, in which the pilot valve solenoid is replaced by a piezoelectric stack, have often been offered by injection system suppliers as a possible premium solution for their prompt dynamic response, flexibility and superior performance [12]. Great attention was therefore paid to the benchmark between piezoelectric and solenoid technologies especially in the early 2010s. The solenoid technology was traditionally reliable and cost-effective, and the unit was physically smaller than piezo units. However, solenoid injectors tend to vibrate more than piezo units, thus creating more noise [13]. Furthermore, piezoelectric injectors consume less power and require a lower electrical current than solenoid injectors because the latter are operated by the peak and hold method, which needs a boosted high operating current for a fast response [14]. Finally, as already mentioned, since the fuel pressure tends to close the pilot valve in piezoelectric injectors, but tends to open this valve in solenoid injectors, the leakage through the pilot valve is larger for solenoid injectors, and this represents a limit to the increase in the maximum rail pressure [15], which is useful for better managing the demands on emissions and performance. Another claimed advantage of piezo-driven injectors is the enhanced dynamic response of the needle [16,17,18]: a piezo-stack could generate forces of 800 N [19], while conventional solenoid systems usually show lower values than 140 N [20]. The solenoid force arises at a distance, and its intensity is at a minimum when the air gap between the magnet and the pilot-valve armature is at a maximum, that is, at the start of the energizing time [21]. Furthermore, the force on the pilot valve increases with the square of the current to the solenoid, and the exponential increase in the current with respect to time needs about 100–150 μs before it is able to move the pilot valve [22]. This could lead to a reduction in the nozzle opening delay (NOD) of indirect-acting piezo injectors, with respect to solenoid ones, that can range from 100 to 150 μs [17,18], to a more rapid opening of the injector nozzle and to higher flow rates [23]. The time required to close the nozzle, that is, the nozzle closure delay (NCD), is usually less for piezoelectric injectors than for solenoid ones: the average velocity of the needle during the downstroke of piezoelectric injectors is about 0.7 m/s, whereas it reduces to 0.5 m/s in solenoid samples [24]. Finally, the multiple injection performance of piezoelectric injectors is generally more flexible, with a minimum interval between fusion-free consecutive injections that is less than the minimum interval pertaining to standard solenoid injectors [25].

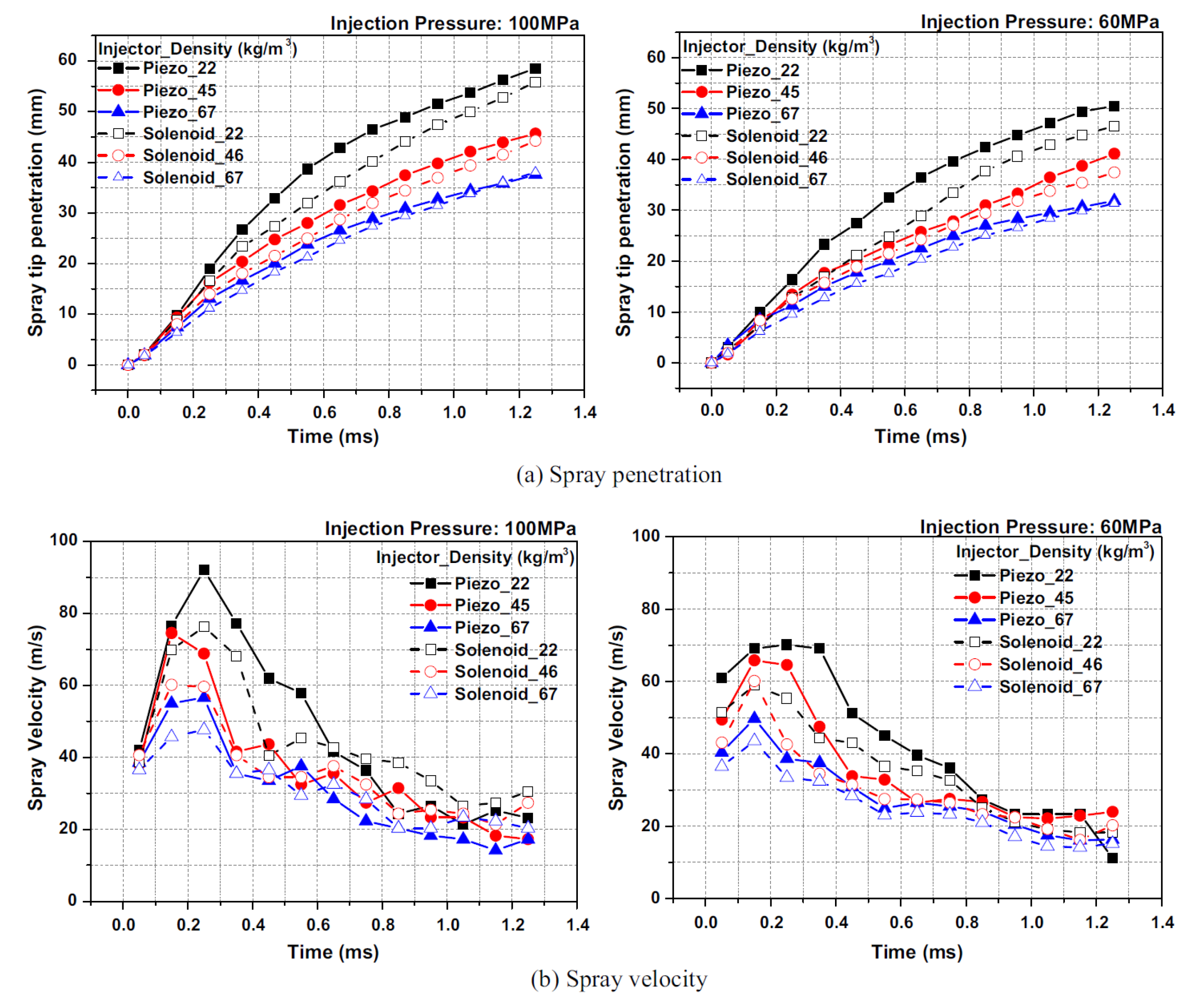

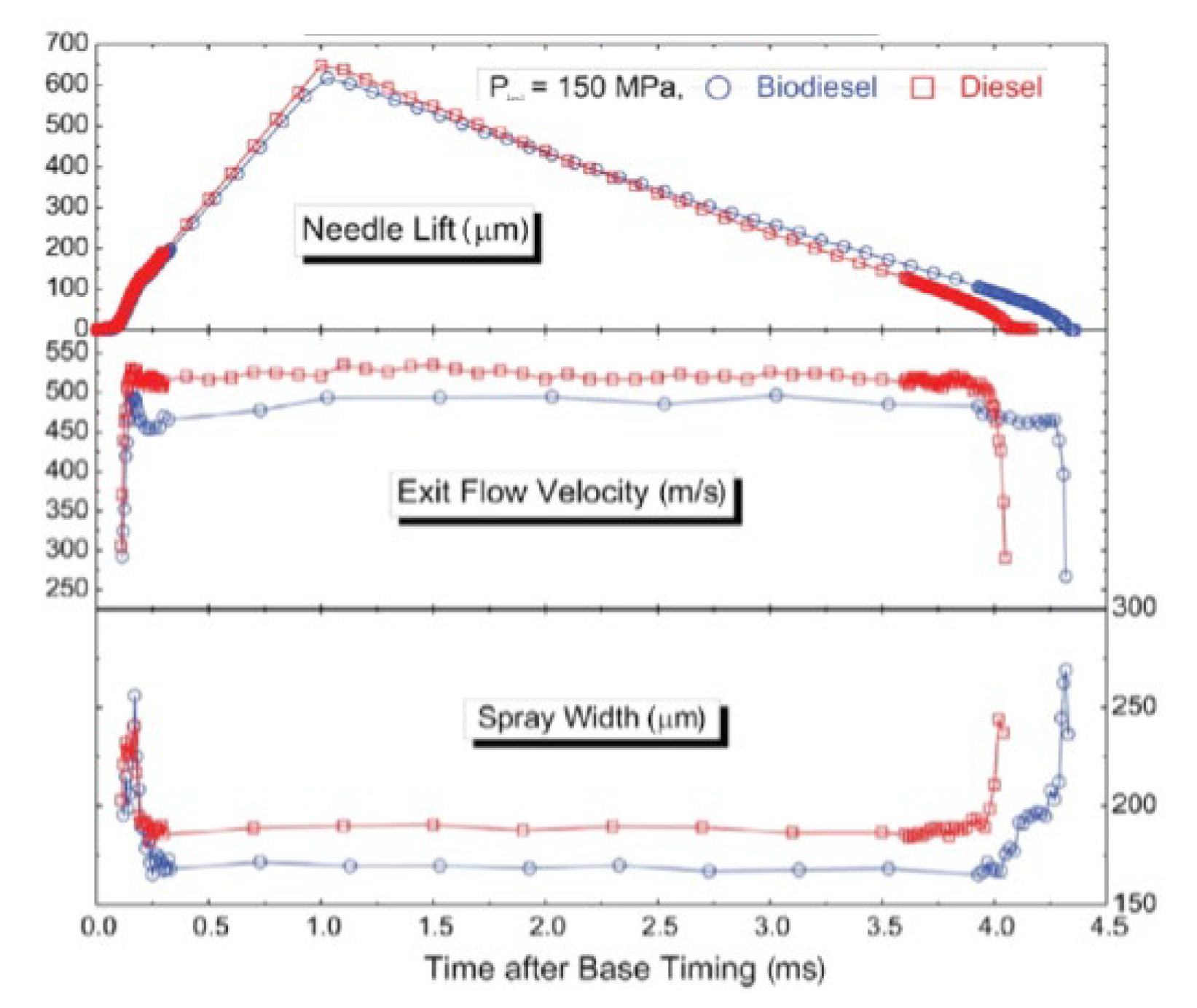

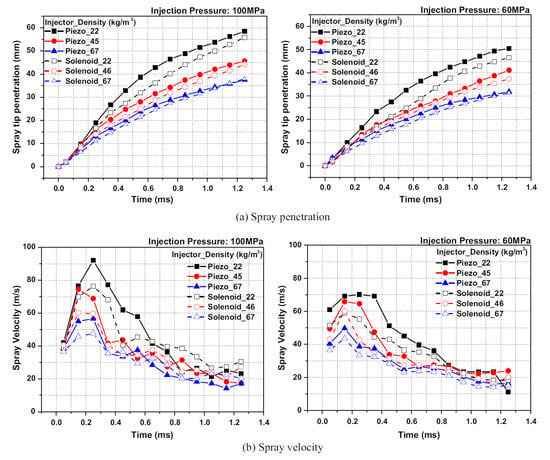

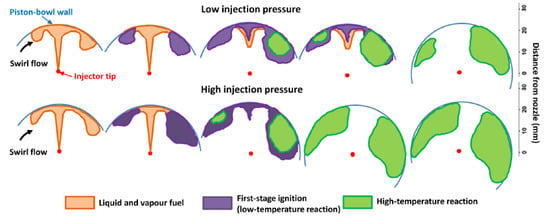

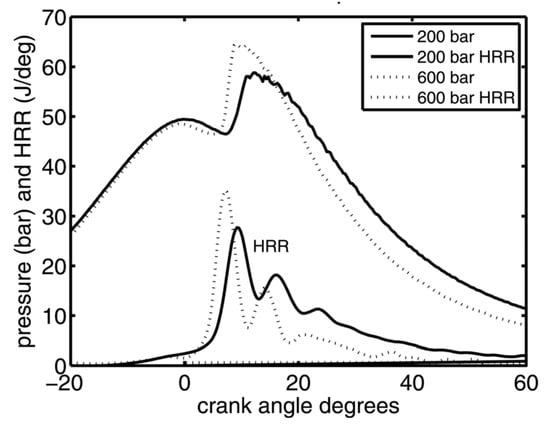

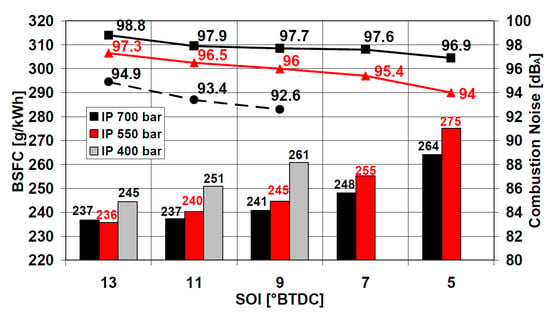

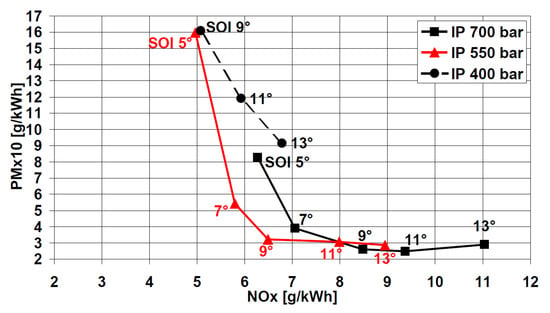

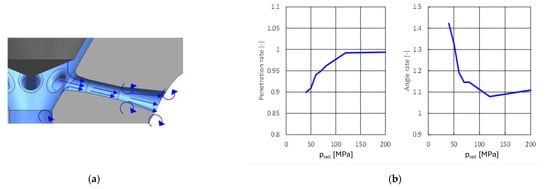

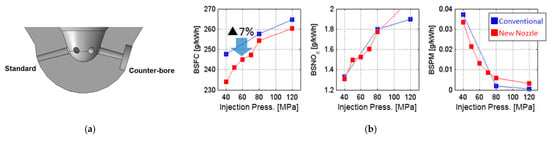

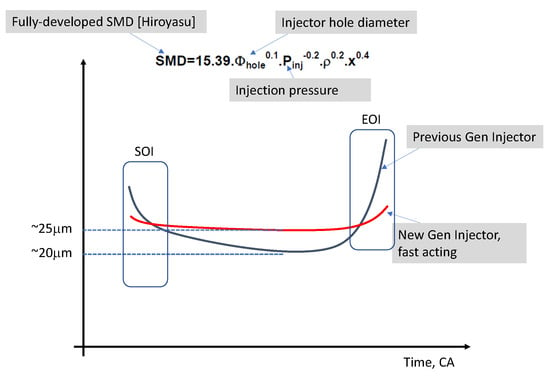

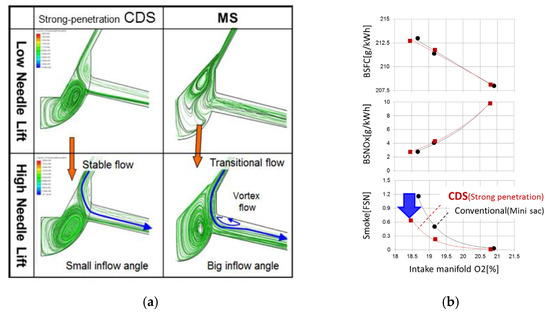

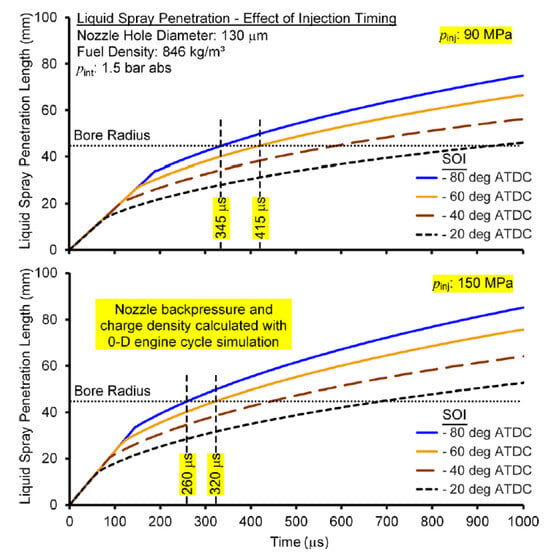

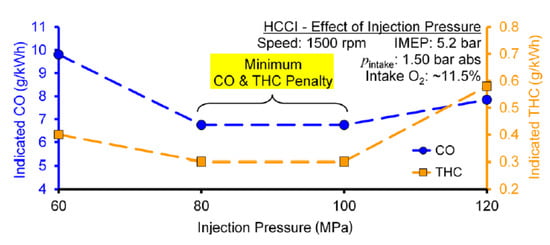

Figure 3a [17] shows the spray penetration, which is the distance from the nozzle tip to the farthest spray zone from the nozzle tip, and fuel droplet velocity, respectively, for 60 and 100 MPa and three air densities (22 kg/m3, 45 kg/m3 and 67 kg/m3) in the injector discharge environment of the bomb. The sprays injected from the holes of the piezoelectric injector grow faster at the beginning of injection (the solenoid and piezoelectric injectors have the same hole diameter). When the charge density is lower, due to smaller resistance for the sprays, the difference between the two injectors in terms of spray penetration and velocity are more obvious.

Figure 3.

Macroscopic spray characteristics for different injectors [17].

The higher spray velocity of piezoelectric injectors (cf. Figure 3b [17]) leads to smaller fuel droplet sizes. More effective vaporization of the fuel spray improves the spatial distribution of the fuel and flame in the combustion chamber and is therefore desirable. Other experimental results showed that spray tip penetration was not influenced significantly by the injector driving system [23]. In fact, although the liquid jet penetration of piezo injectors was higher than that of solenoid injectors [25], the quicker vaporization of the liquid fuel for the piezo injector can compensate for the previous effect since the penetration of a liquid spray is more effective than that of a vaporous one. The results in Figure 3a also show that the penetration differences significantly decrease as time passes.

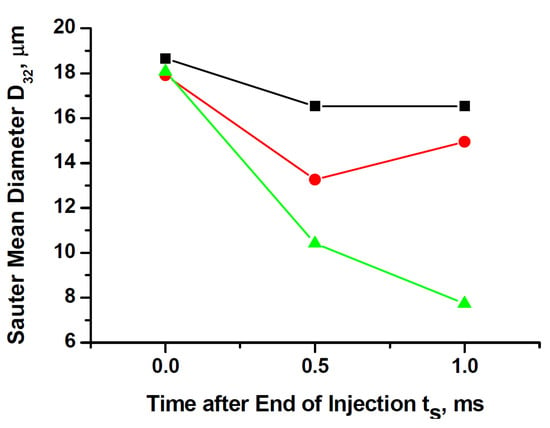

In general, in the comparisons between solenoid and piezoelectric injector performance, one critical aspect that can affect the final results and can explain apparent inconsistencies in the literature concerns the presence of differences in some fundamental sizes (hole A and Z diameters, control chamber and delivery chamber volumes, number and diameter of holes, nozzle layout and needle sizes) between the two injector types. Another fundamental point is related to the technology of piezoelectric and solenoid injectors that are compared. In fact, solenoid CR injectors have witnessed important developments that partially solved some of their main weak points. It was possible to achieve high-speed solenoids, which featured a faster dynamic response than conventional ones, by optimizing some of the magnetic and electric circuit parameters [26]. Solenoid-driving voltages of up to 80 V can be applied to obtain a sharp current rise, which in turn minimizes the needle valve opening delay. In addition to this, the layout of the pilot valve of solenoid injectors, which can be either pressure-balanced or pressure-unbalanced, has a remarkable influence on the final performance. A solenoid injector endowed with a pressure-balanced pilot-valve layout can feature a static leakage about 25% lower than those of solenoid injectors equipped with a standard pilot valve, even though it remains significantly higher than that the typical one pertaining to a piezoelectric injector. When the pressure-balanced pilot-valve layout is coupled to an integrated minirail injector (the minirail could also be applied to piezoelectric injectors), the leakage could decrease to 50%, compared to a more conventional solenoid injector. A supplementary benefit of the pressure-balanced pilot valve is that it represents an efficient way of further improving solenoid injector promptness [27]. In fact, the stroke-end of the pilot valve can be reduced for a fixed flow area because the typical values for the diameter of the flow-area can be set up to about three times higher than those pertaining to the pressure-unbalanced pilot valve because of the lower tendency to static leakage of the balanced playout; this induces a more rapid opening of the injector. Furthermore, the reduced weight of the pressure-balanced pilot valve leads to a decrease in the required magnetic force of about 35%, compared to standard solenoid injectors with unbalanced pilot valves [27]: consequently, less electrical energy is required to activate the injector. Finally, the pressure-balanced pilot valve permits an increase in the number of injections with a reduced dwell time, due to the faster dynamic response of the pilot valve, which affects the injector needle dynamics. Moreover, both indirect-acting piezo (IAP) and solenoid (IAS) injectors can be endowed with a three-way pilot valve [28] and indirect-acting piezoelectric injectors can feature a bypass-circuit that directly connects delivery and control chambers [24]. These design solutions give injectors a prompter dynamic response (above all, the three-way pilot valve reduces the dynamic leakage) and contribute to reducing the Sauter mean diameter of the fuel drops, which is the ratio of the average volume to average surface area of the spray droplets, averaged over the entire droplet size distribution range, during the nozzle opening and closure phases (needle-seat throttled phases).

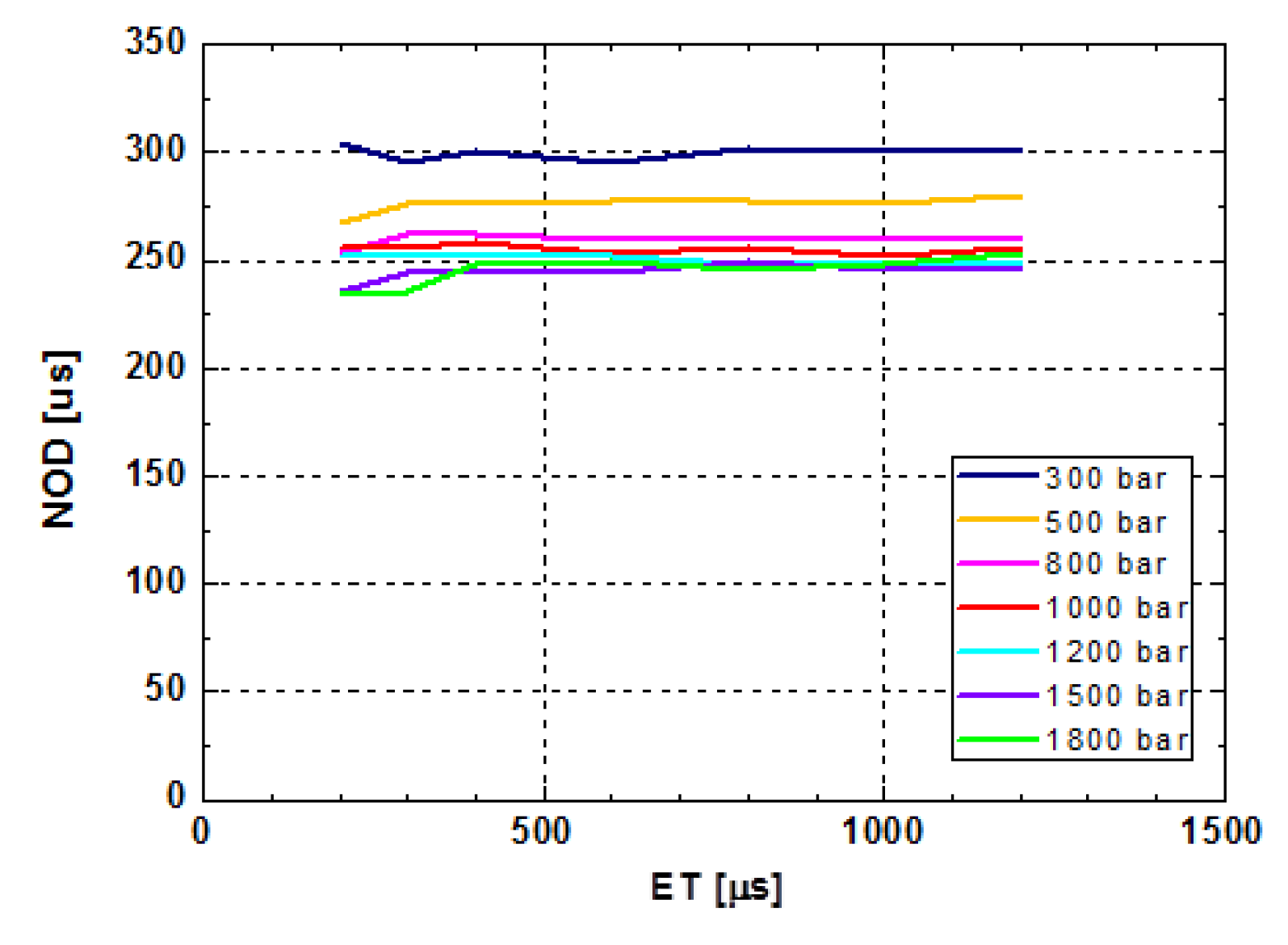

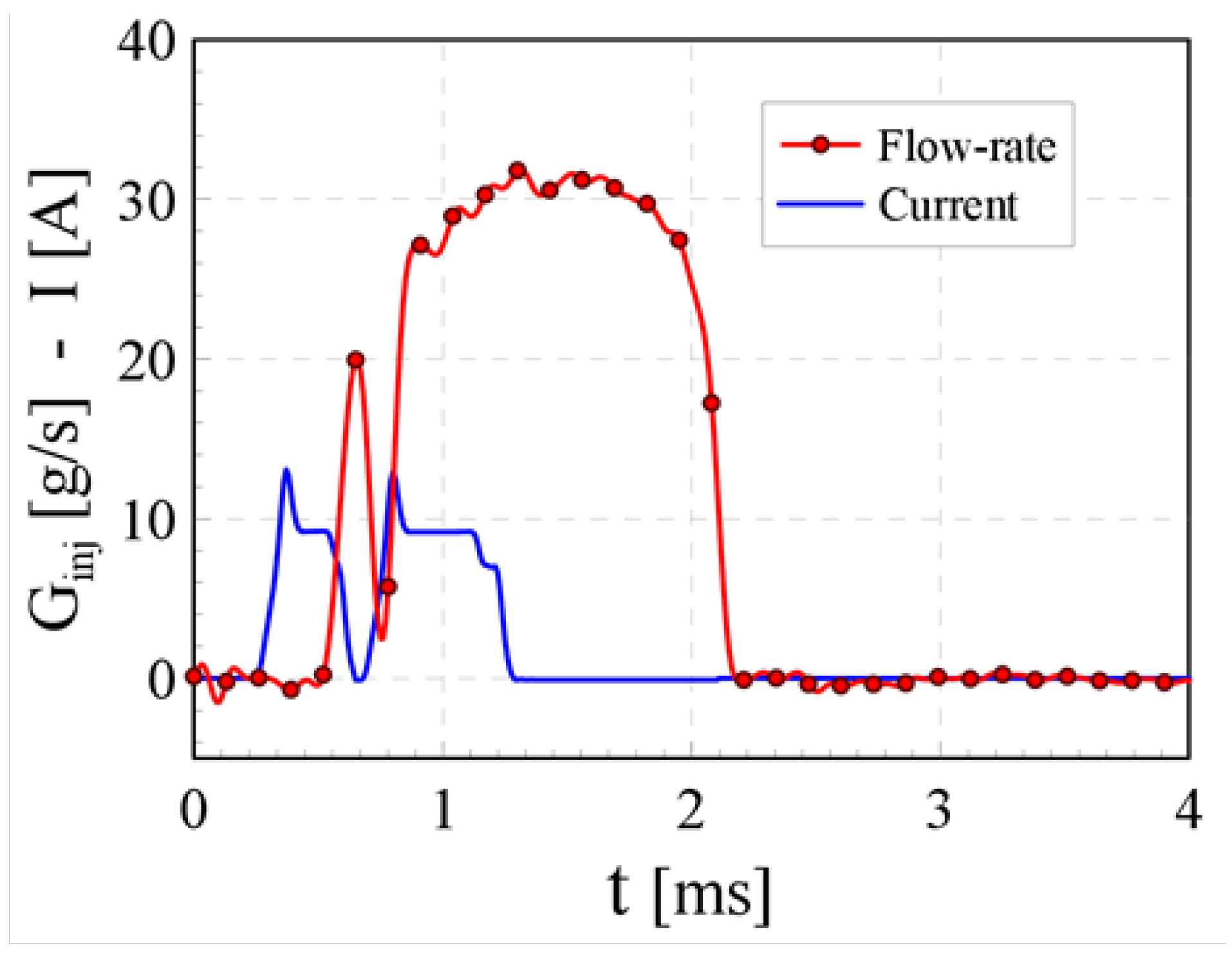

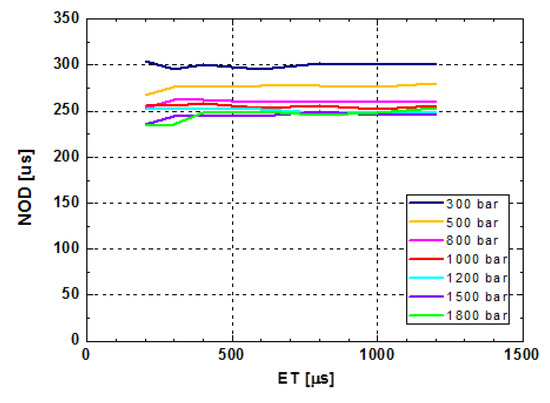

Figure 4 reports the nozzle opening delay for an IAP injector. The nozzle opening delay is the time interval between the start of electrical current signal increase and the instant at which fuel injection begins.

Figure 4.

Nozzle opening delay for an IAP injector [15].

Tests were made with IAS injectors featuring the same control chamber volume, diameters of the A and Z holes, needle spring preload, as well as the geometry and material of the needle, as those of the IAP injectors in Figure 4. The NOD values of such IAS injectors also ranged from 250 μs to 300 μs and decrease when increasing the rail pressure. This definitely proved that the driving system itself did not play a major role in influencing the dynamic response of the injector. The inconsistencies found in the literature about the differences in NOD values between solenoid and piezoelectric injectors (they range from 100 to 150 μs) [17] are mainly ascribed to differences in hydraulic and mechanical parameters between the two injectors.

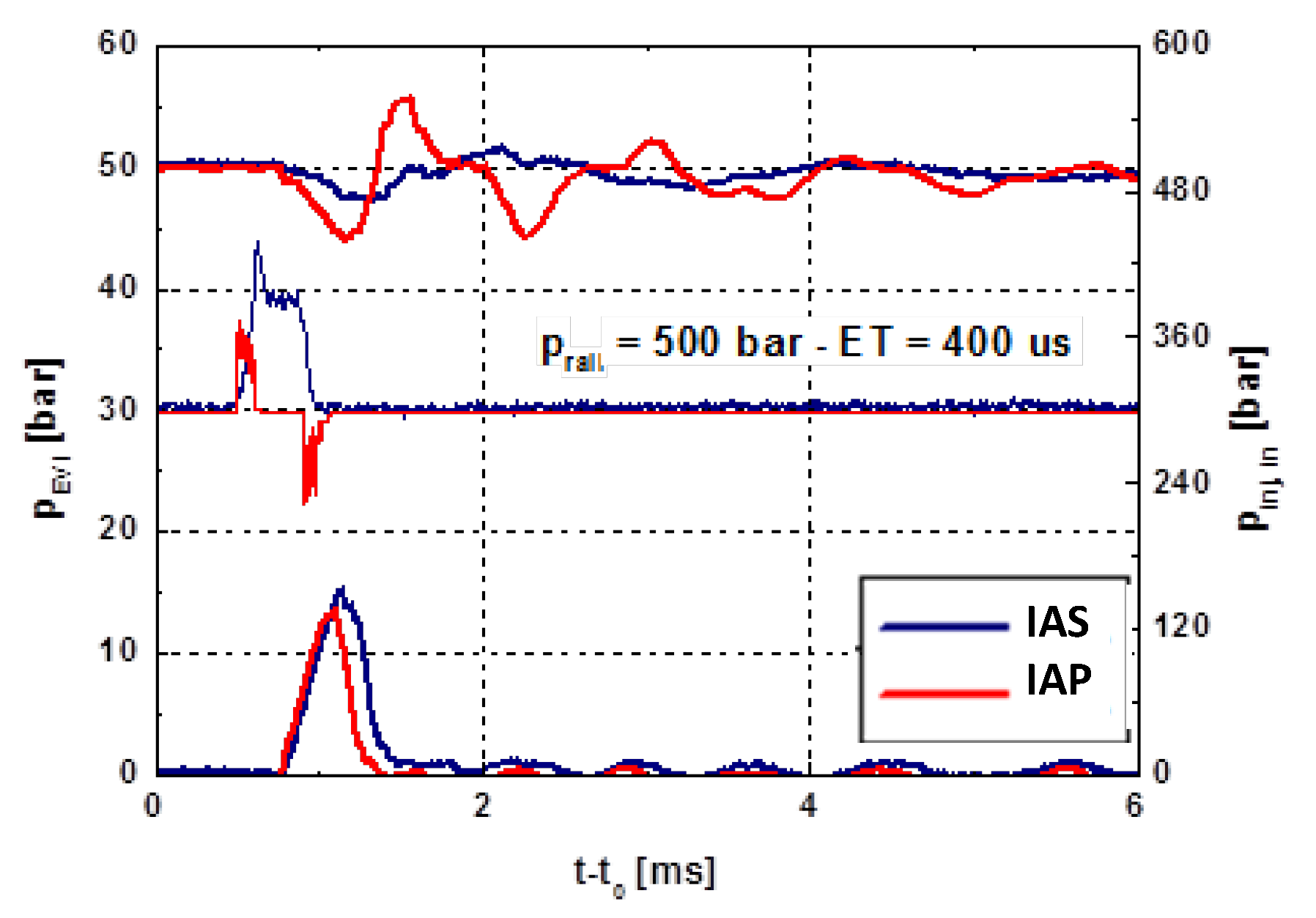

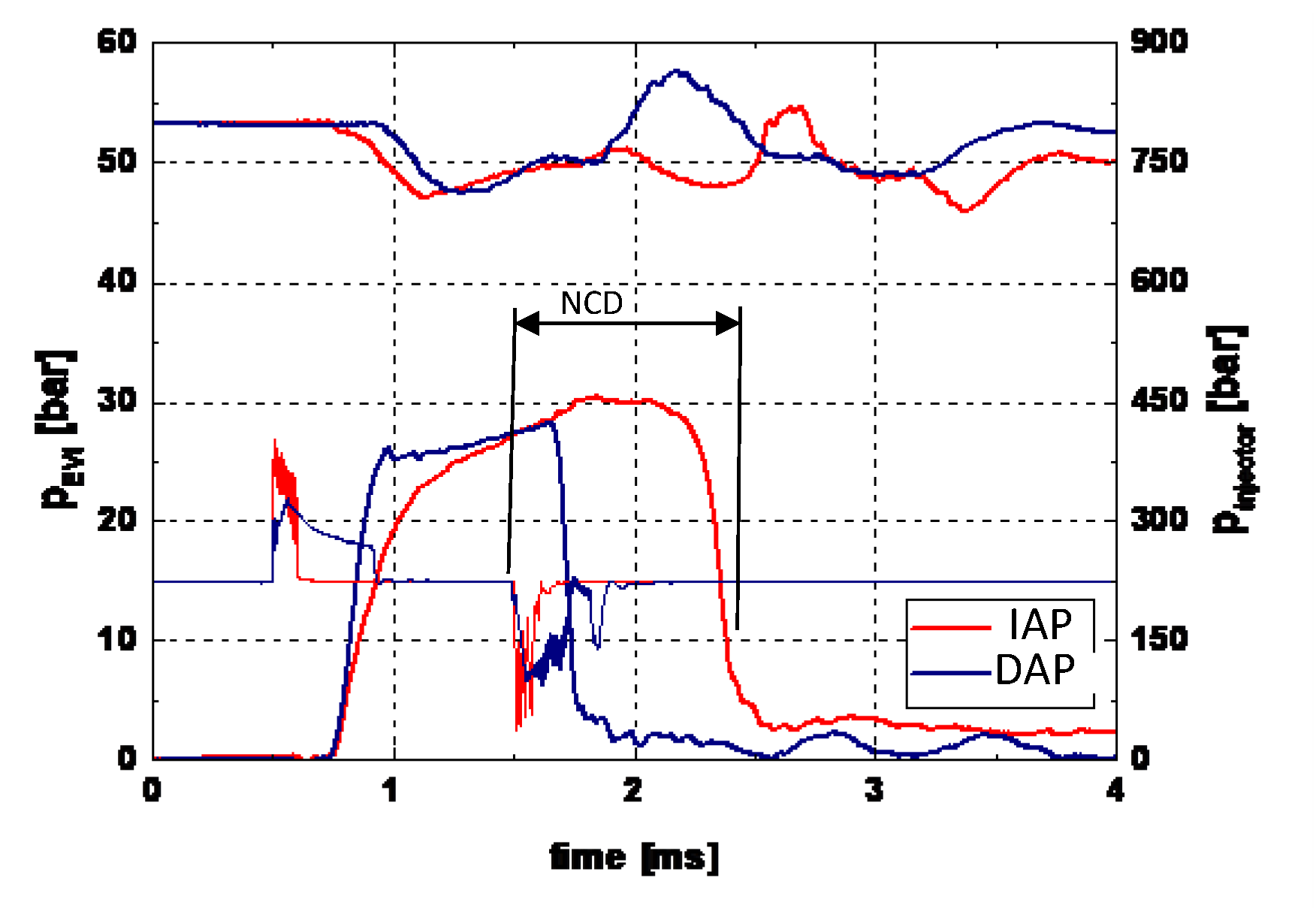

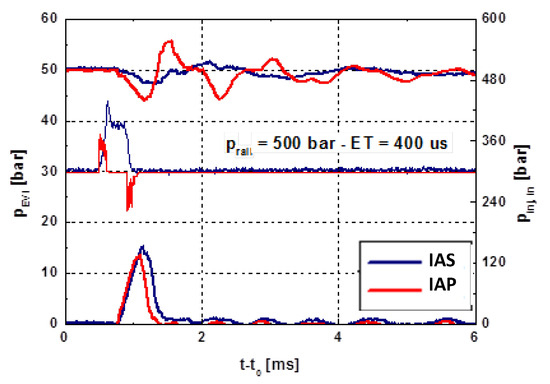

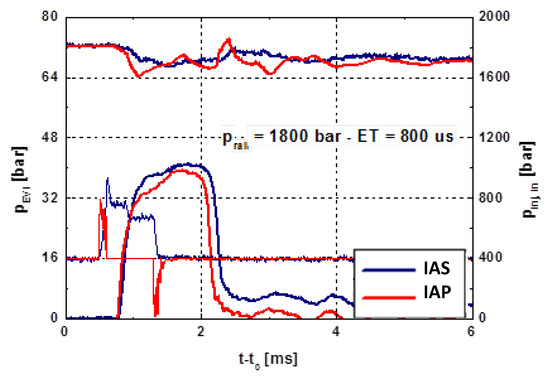

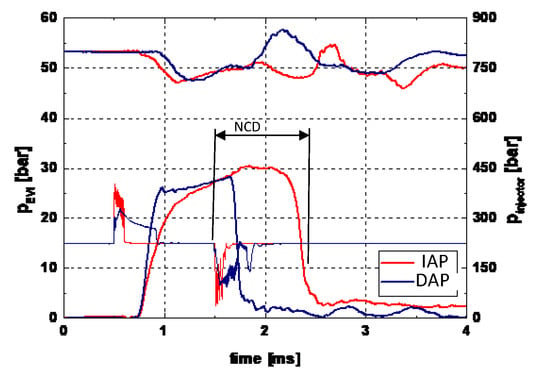

Figure 5 and Figure 6 plot the injection rate (measured as pEVI) and injector-inlet pressure (pinj,in is measured along the rail-to-injector pipe) time histories of the IAP and IAS injectors for two different ET and prail; furthermore, the current time history is also reported. The flow rate shape is generally almost rectangular for the IAS injector for medium and high ET values (cf. Figure 6); in particular, the flow rate values that occur in correspondence with the final portion of ET are slightly higher for the IAS injector. Furthermore, the triangular flow rate time histories plotted in Figure 5, under a low ET value, show a higher peak value for the IAS injector. All these differences are due to the presence of the integrated minirail in the IAS injector. The needle velocity and the needle-lift peak value always increase in the presence of the minirail for fixed prail and ET values because the opening pressure force on the needle is higher during the upstroke [29]. In fact, the delivery chamber pressure decrease that follows fuel injection is smaller when a minirail is integrated in the injector hydraulic circuit, and this allows the pressure force acting on the needle to be intensified. On the other hand, the fuel injection finishes later for the IAS injector in Figure 5 and Figure 6, due to the absence of the bypass. The higher NCD of IAS is also the cause for its higher tendency to injection fusion when the dwell time is reduced [30]. In fact, the minimum value of DT that does not cause any fusion between consecutive injection shots, namely the injection fusion threshold, increases proportionally with the NCD of the former shot.

Figure 5.

Time histories of pinj,in and pEVI (prail = 500 bar) [15].

Figure 6.

Time histories of pinj,in and pEVI (prail = 1800 bar) [15].

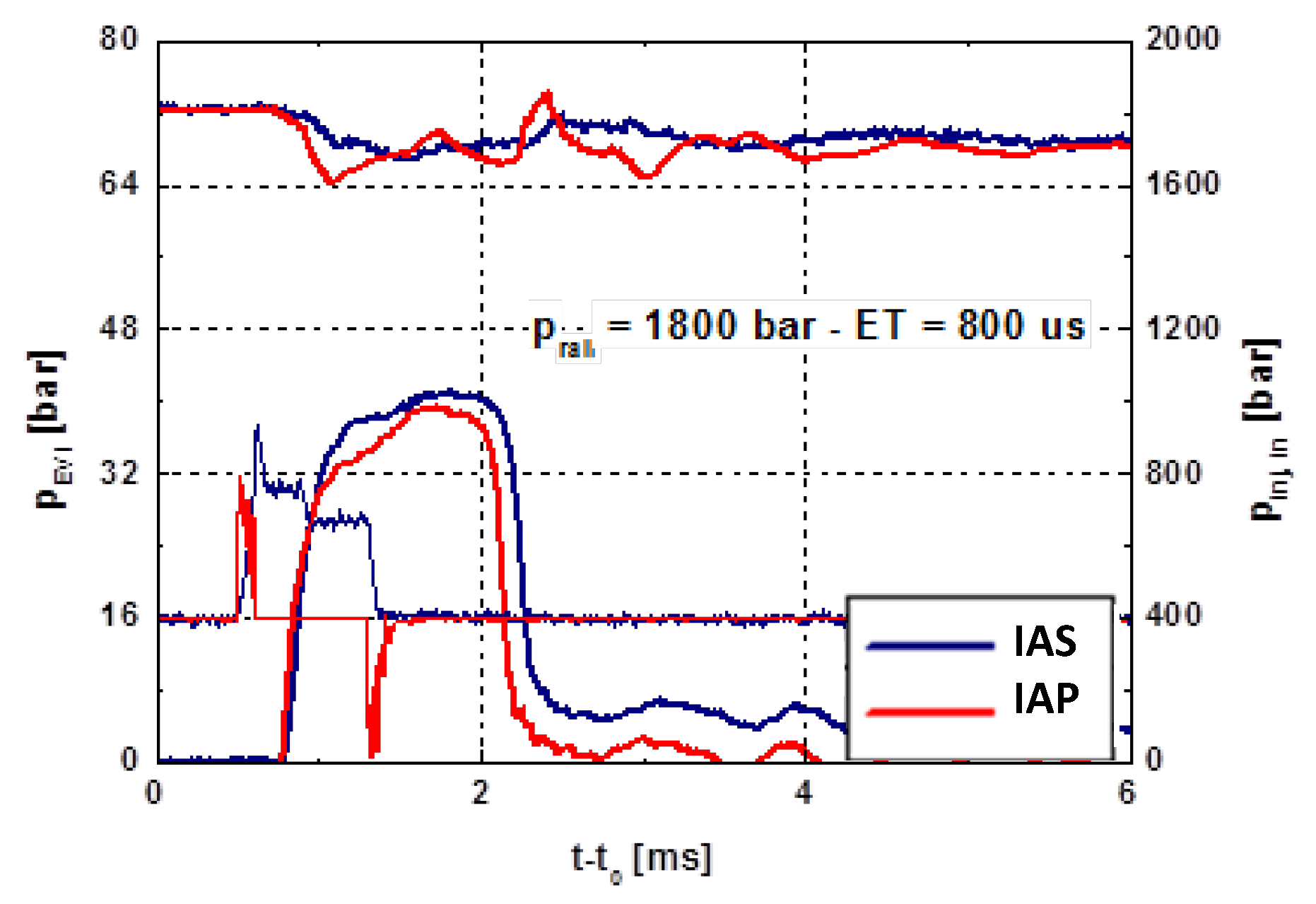

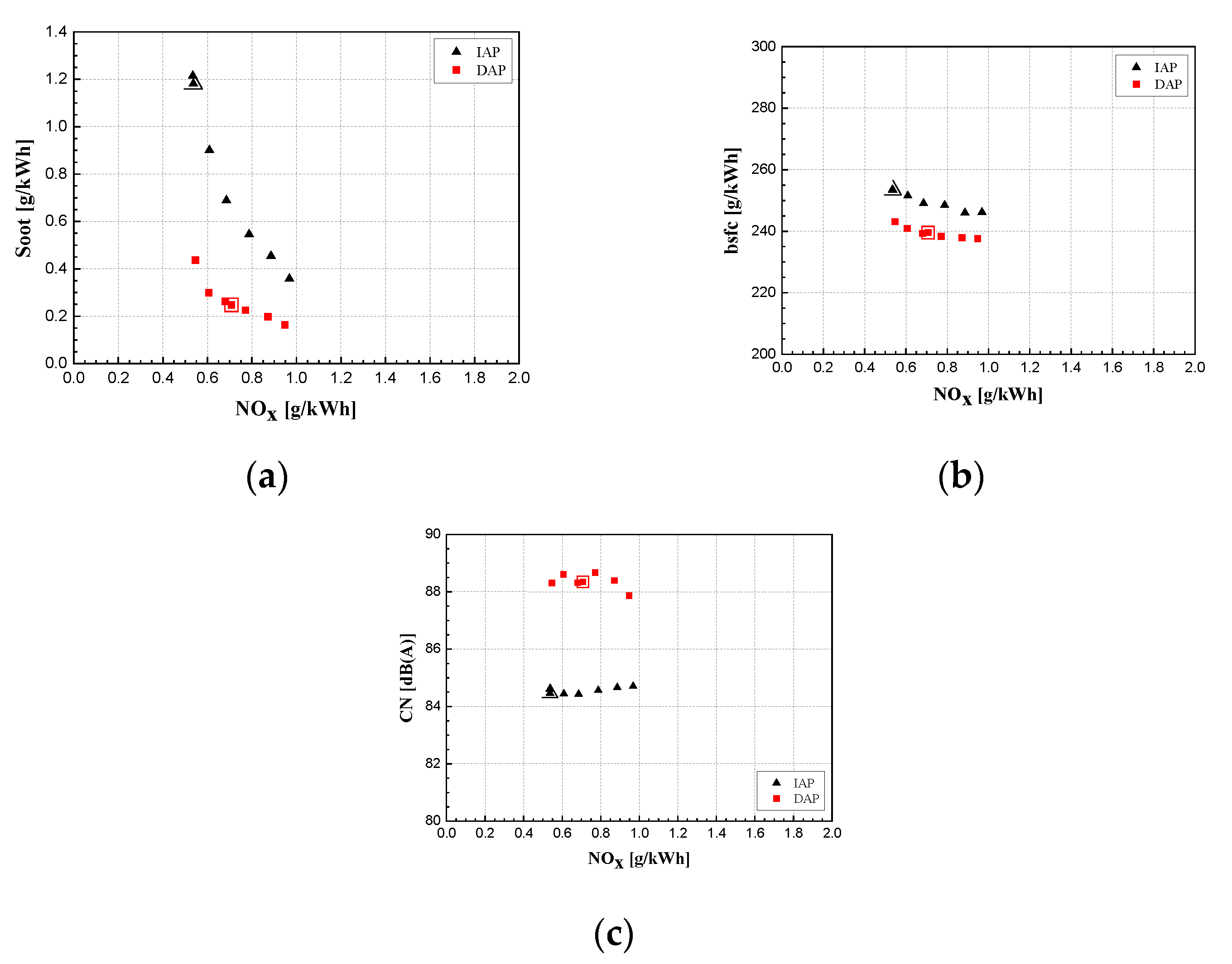

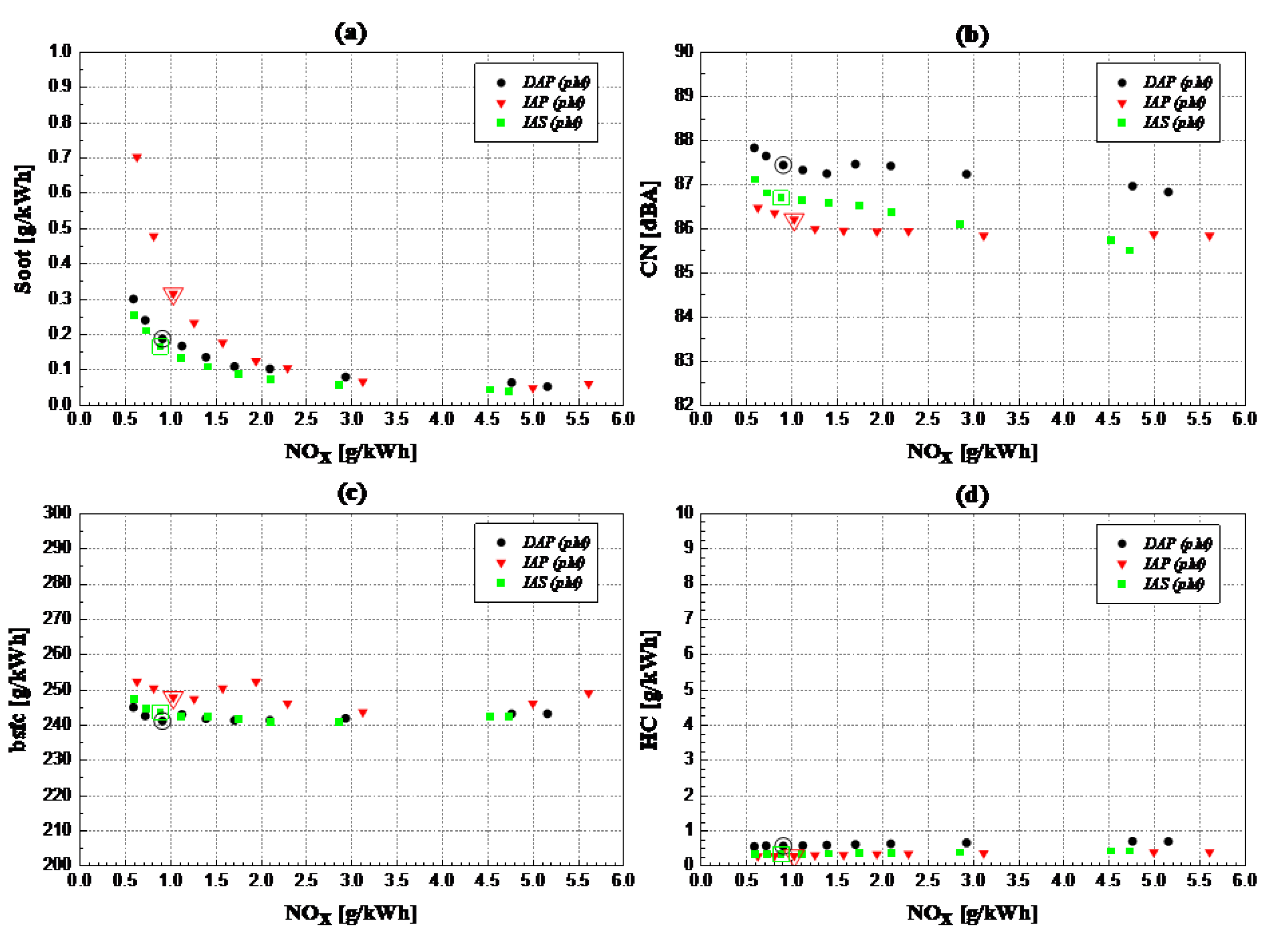

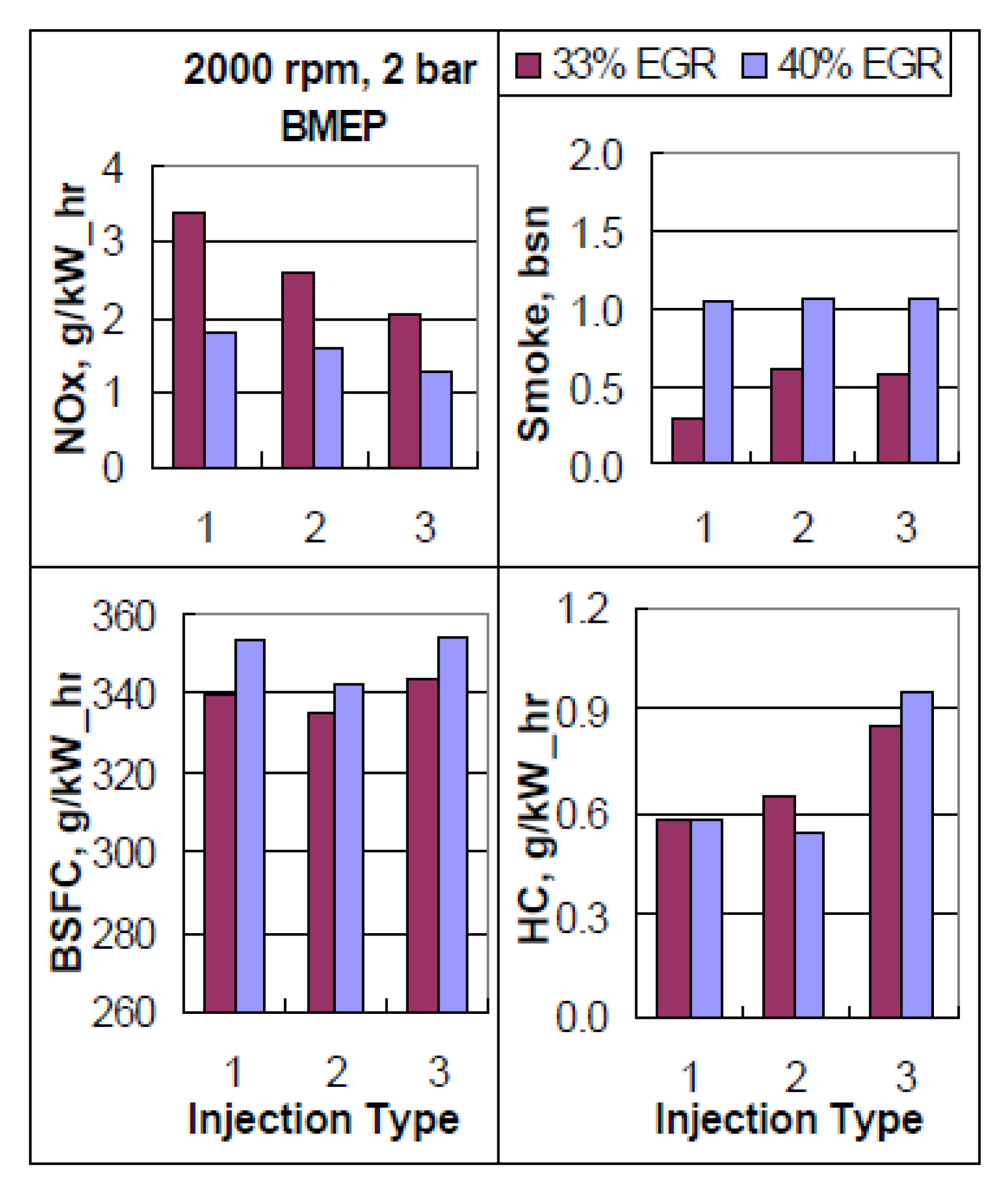

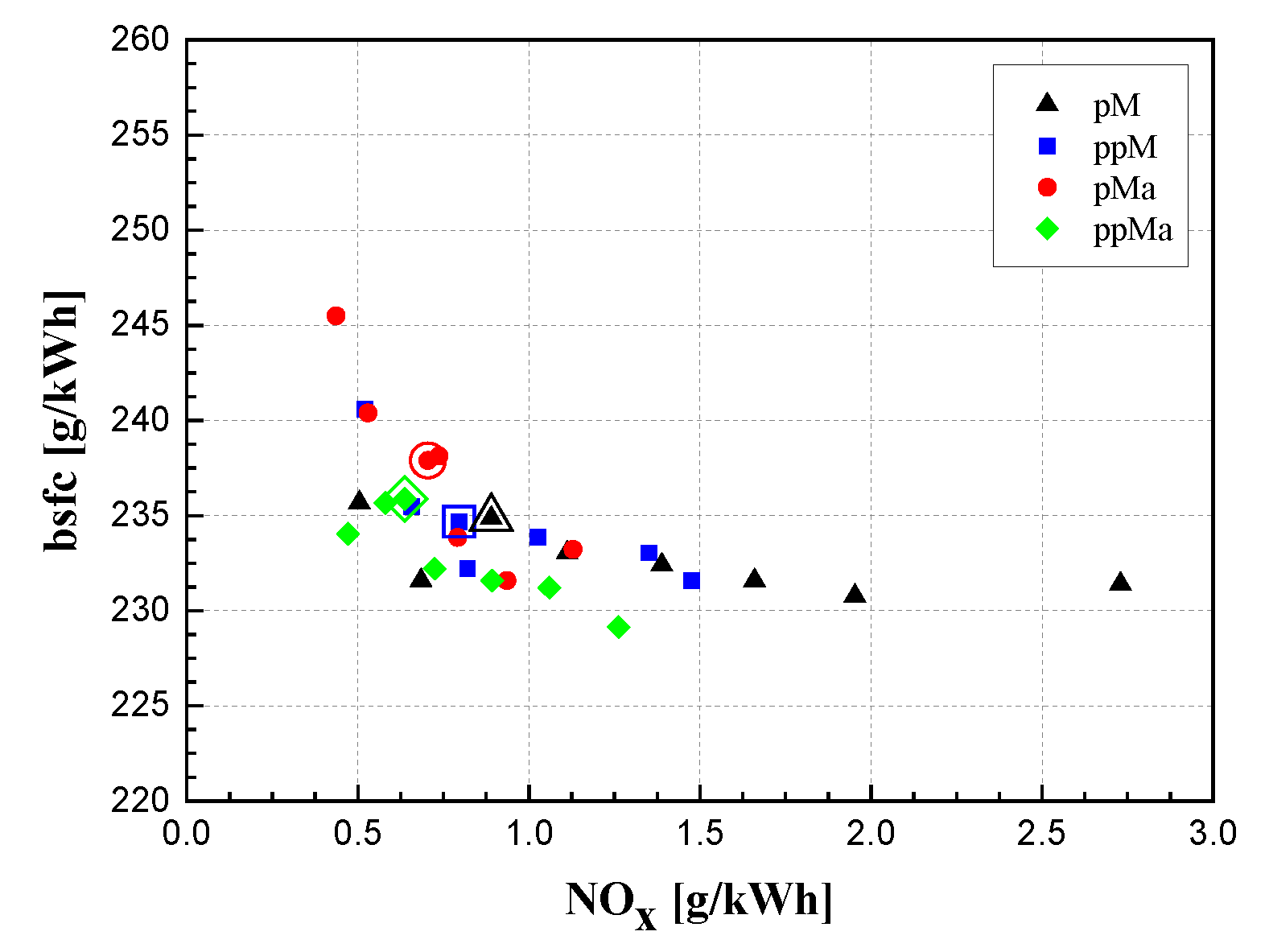

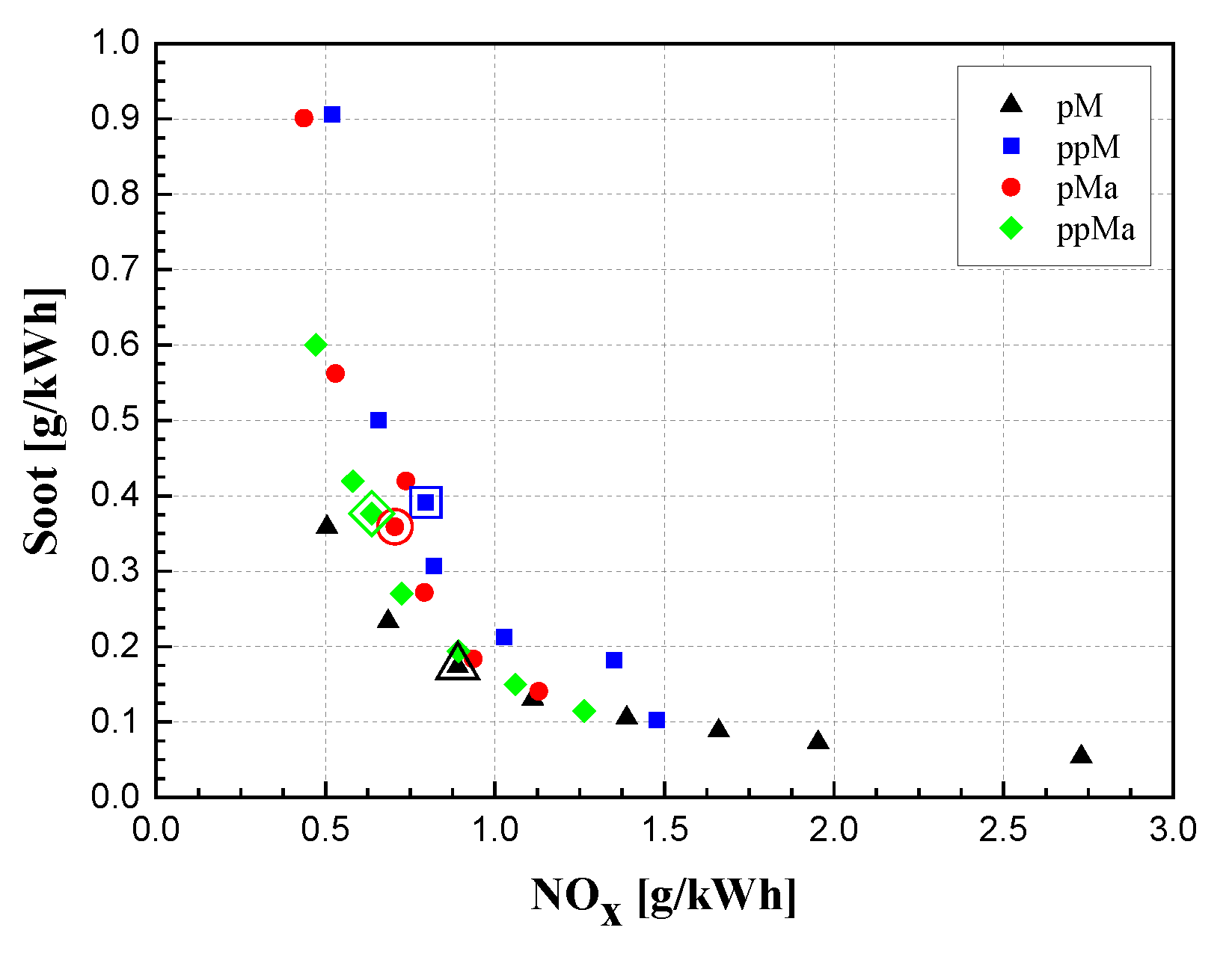

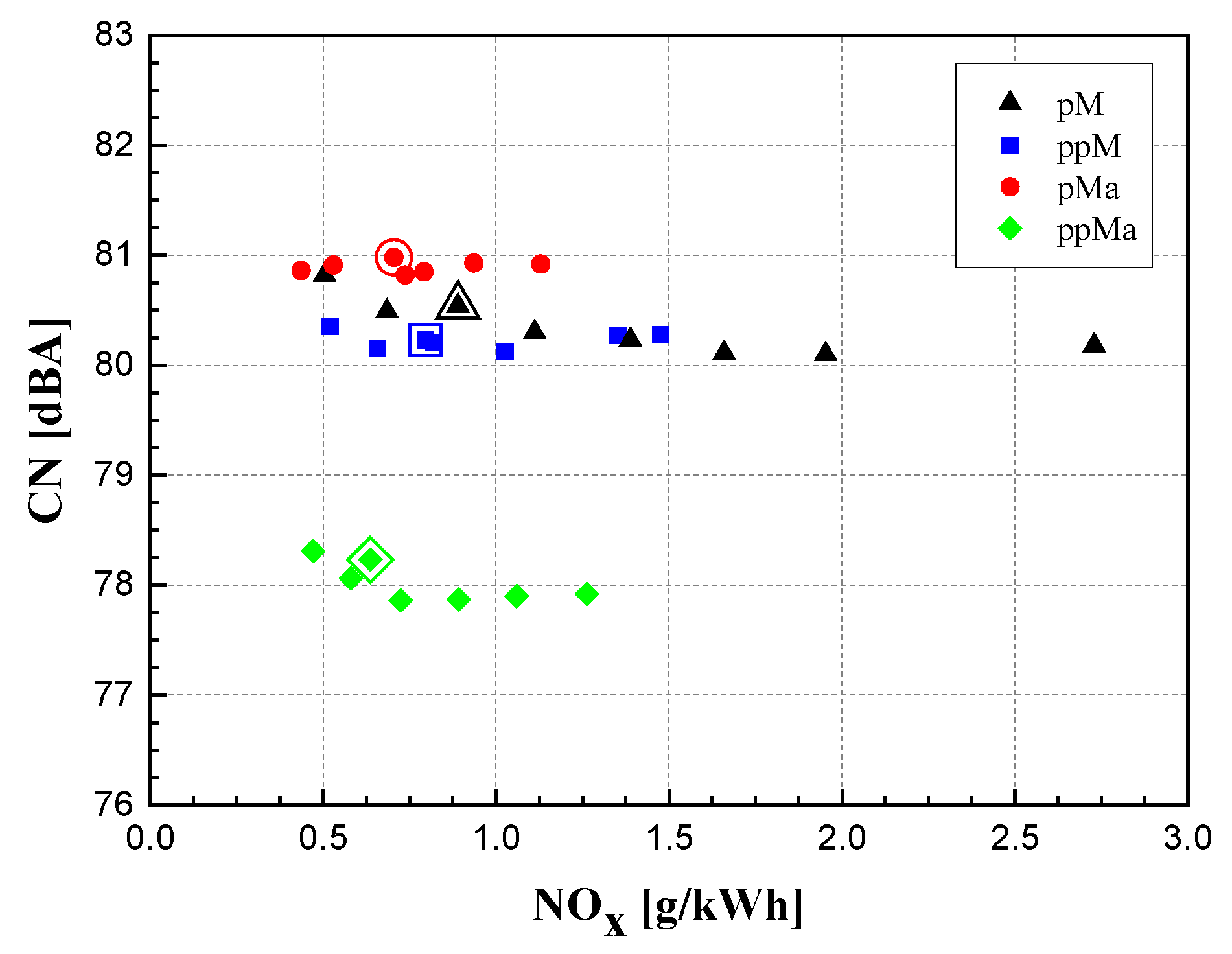

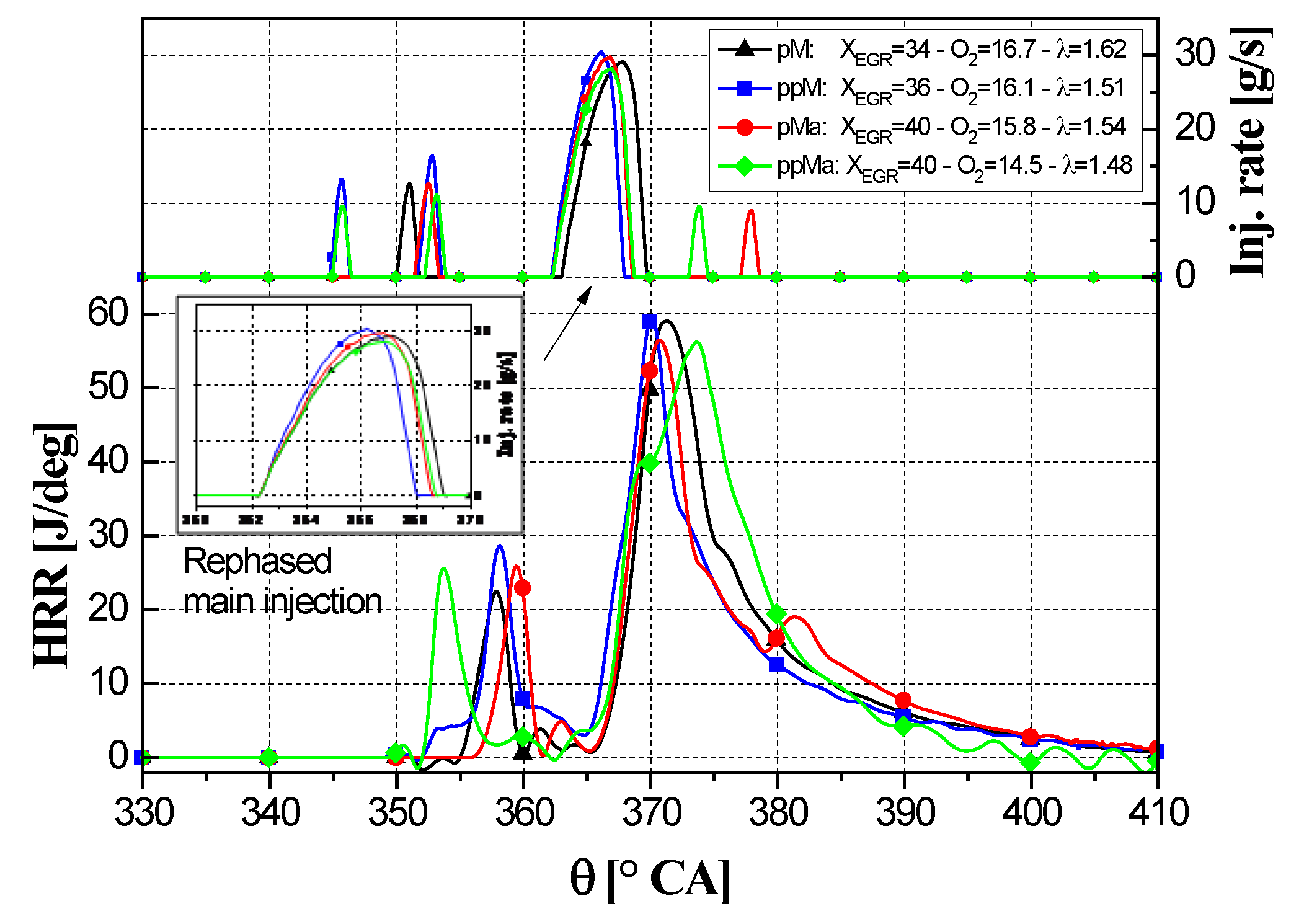

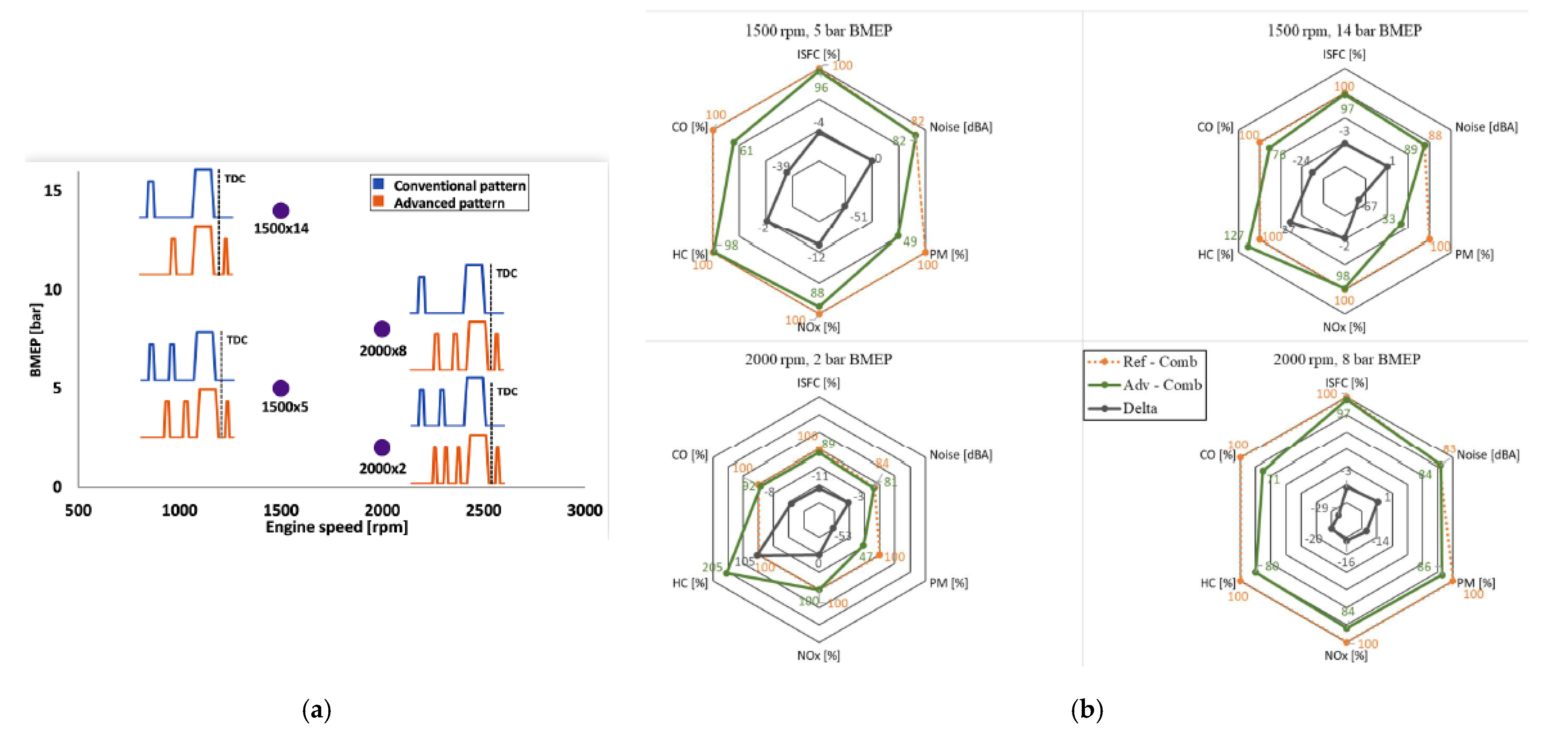

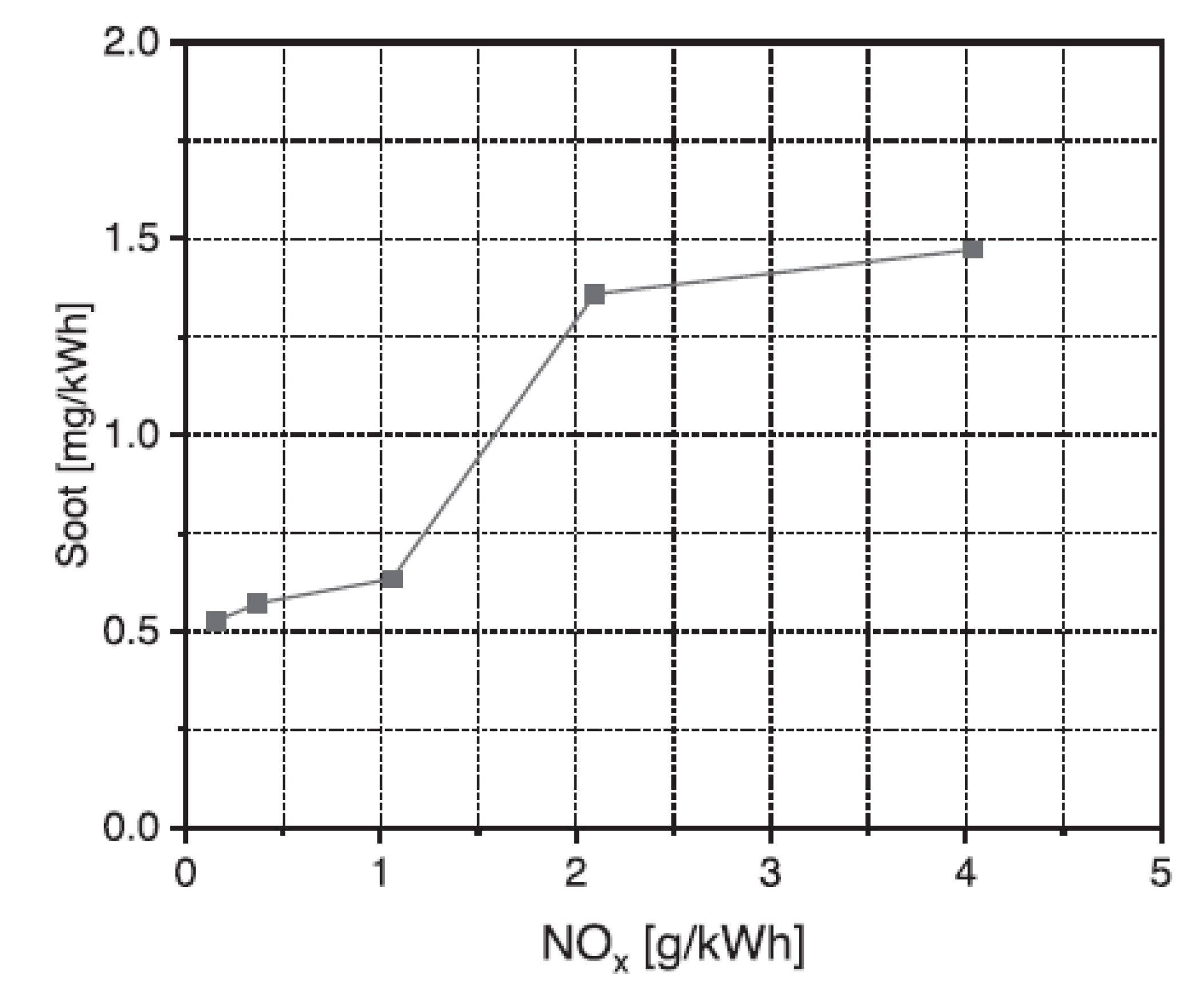

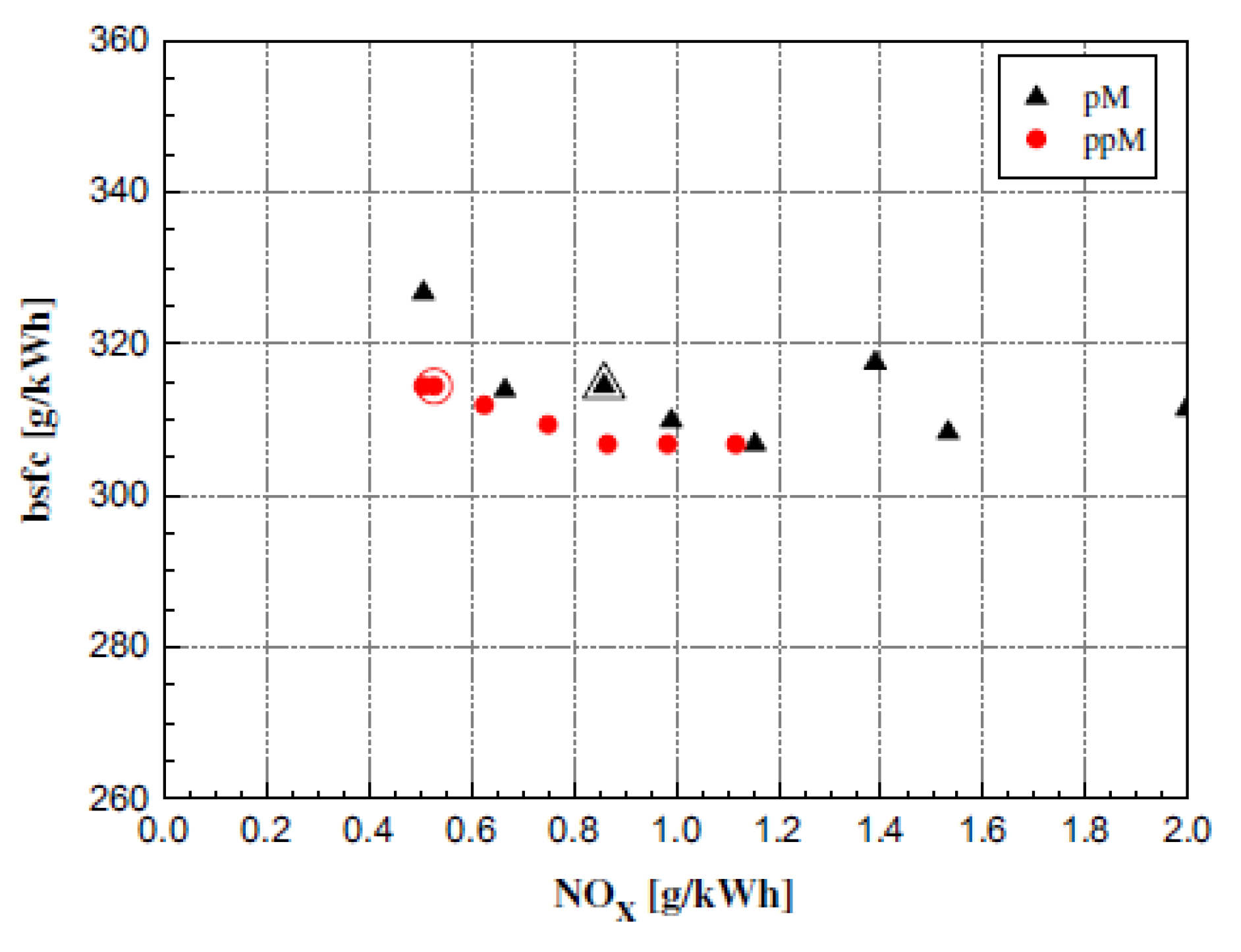

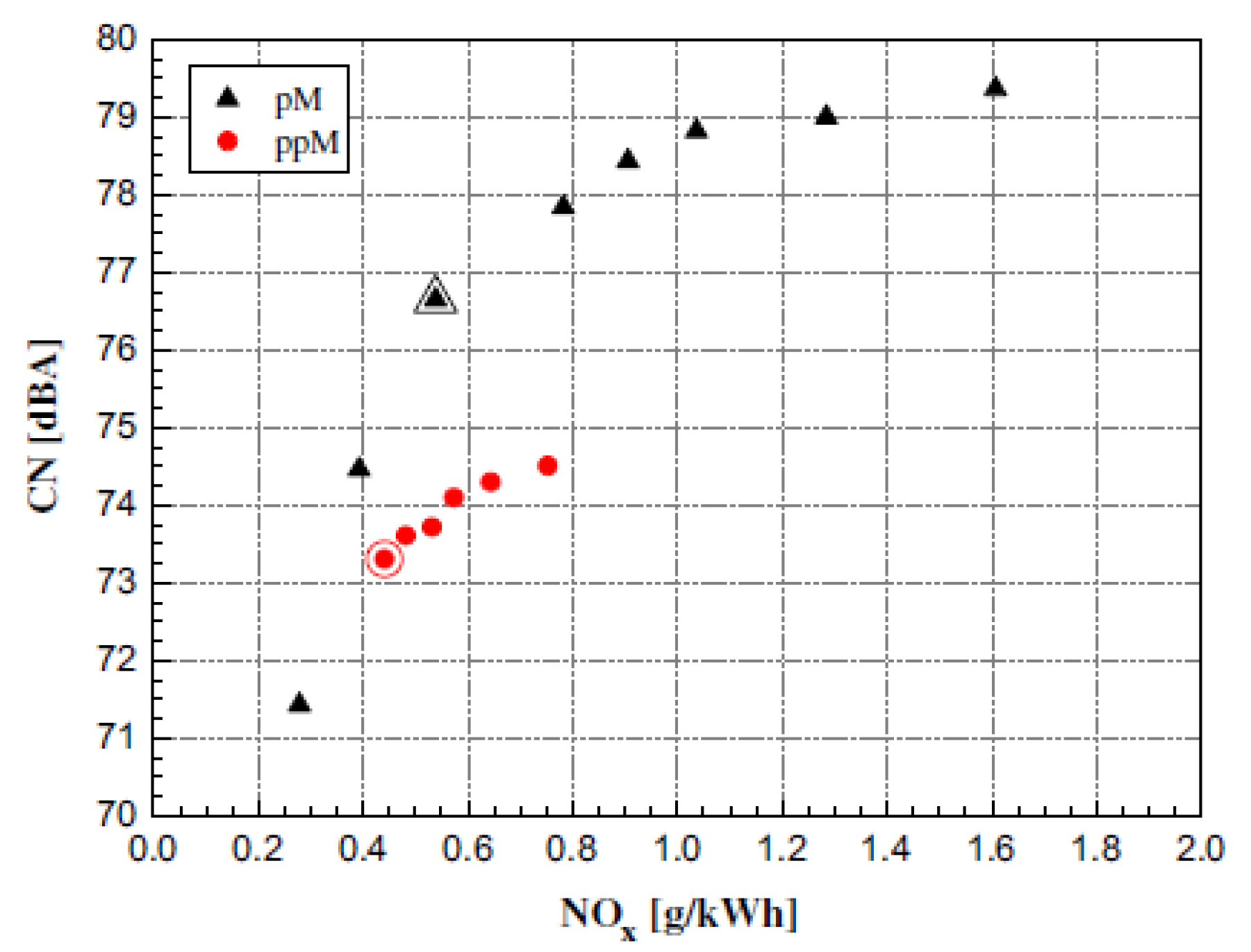

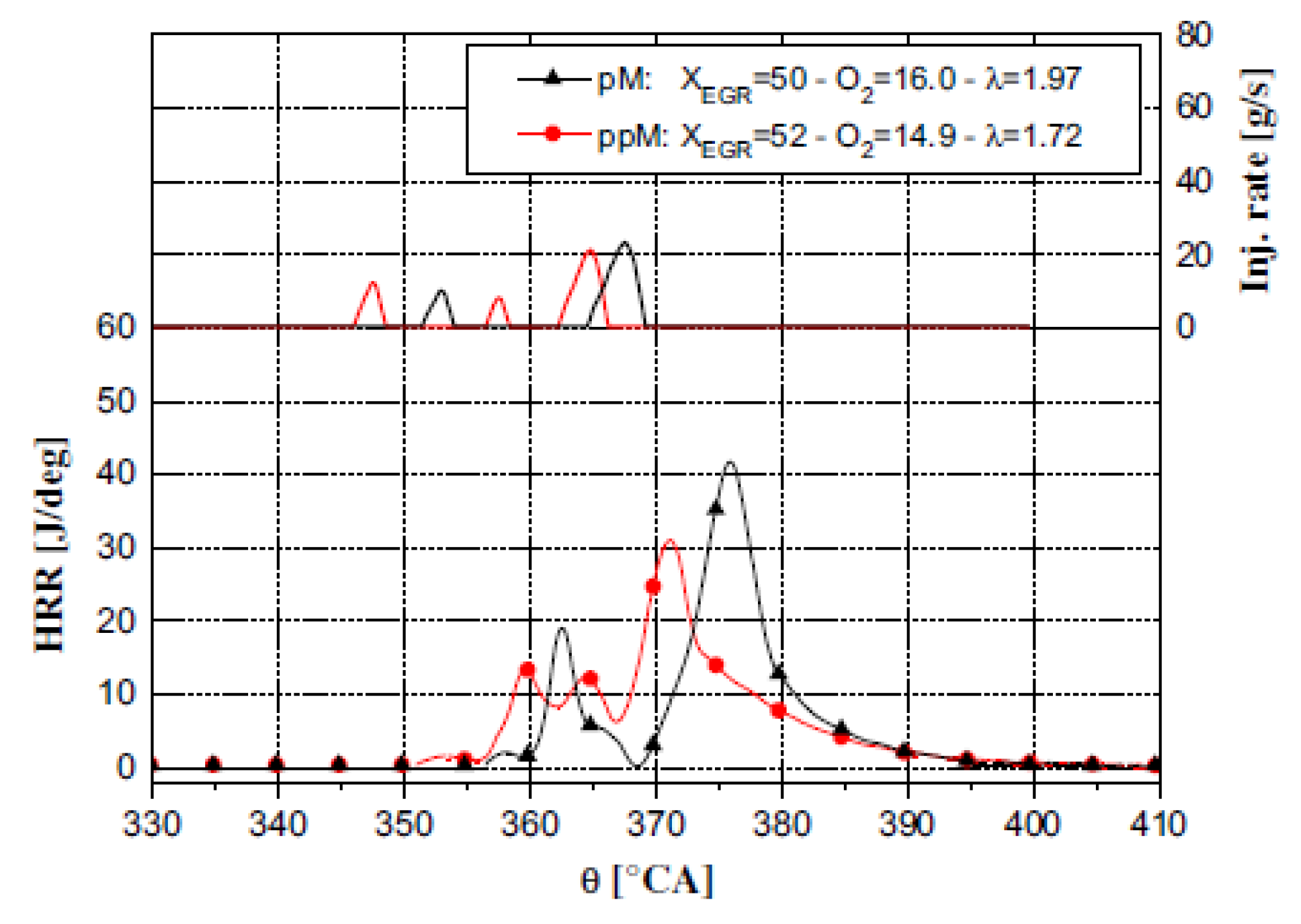

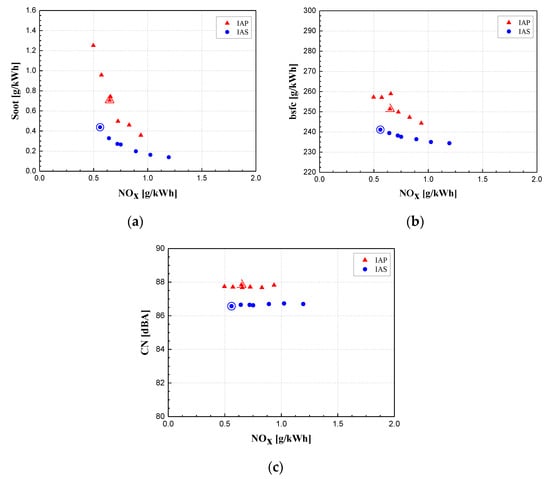

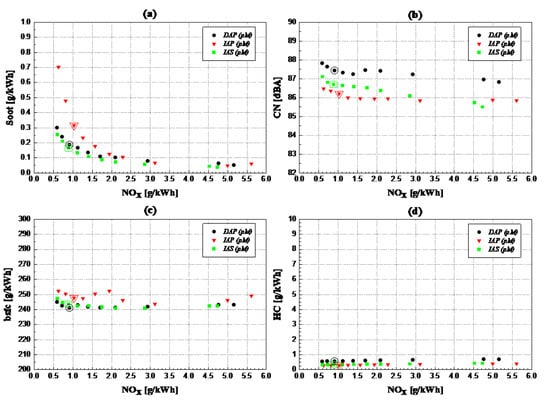

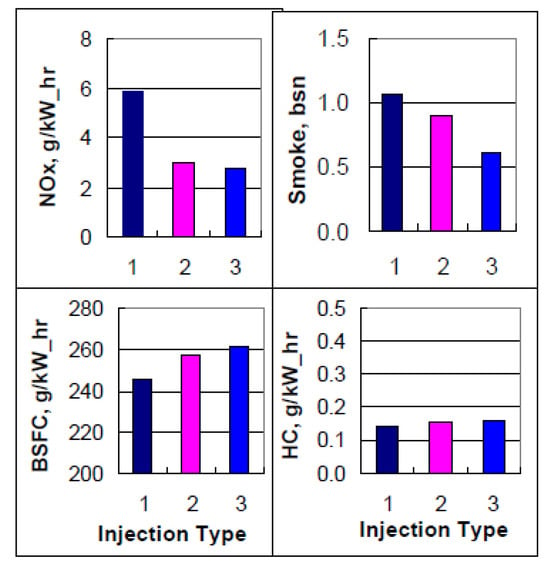

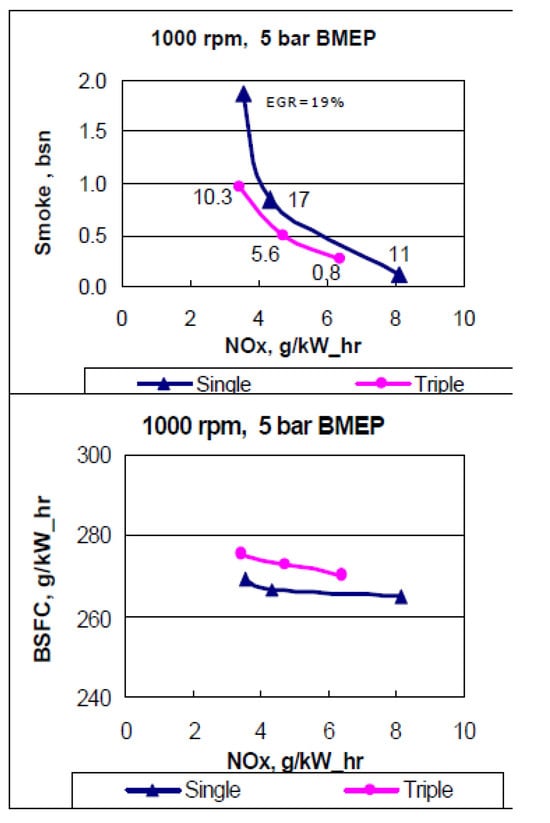

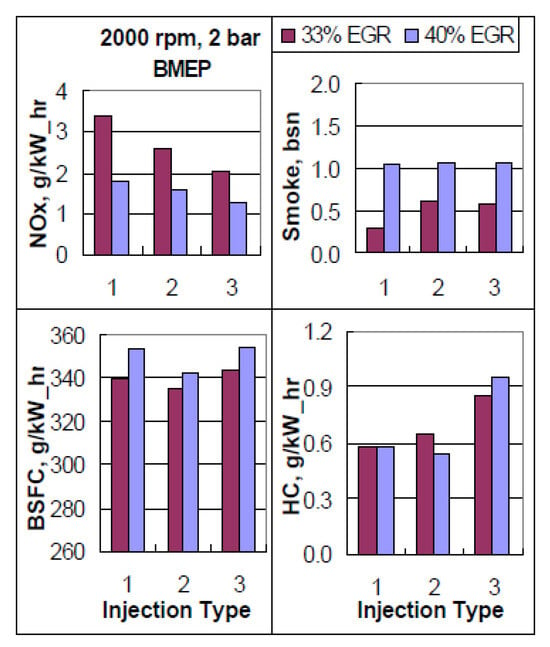

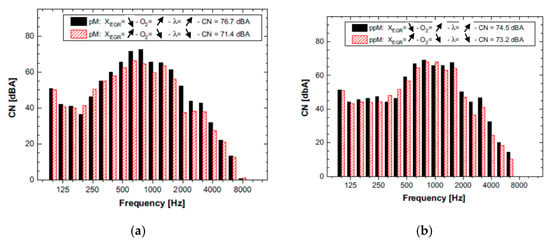

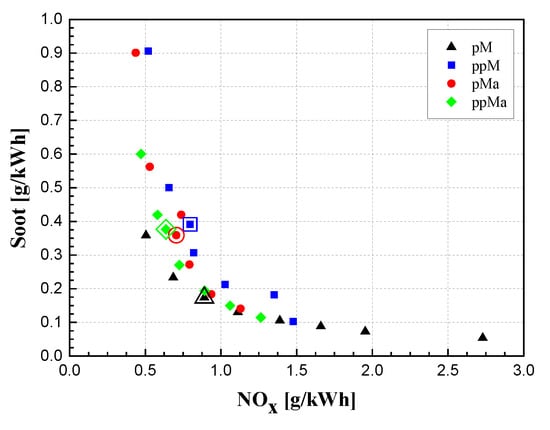

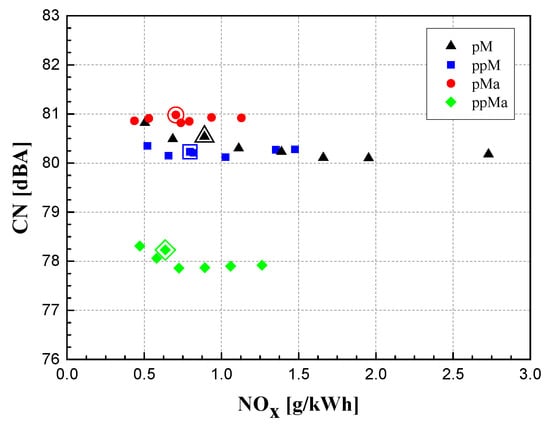

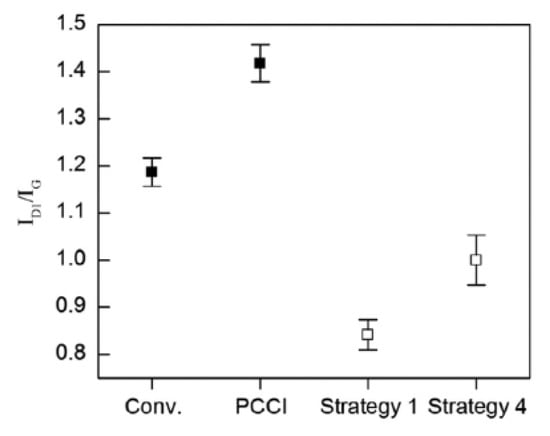

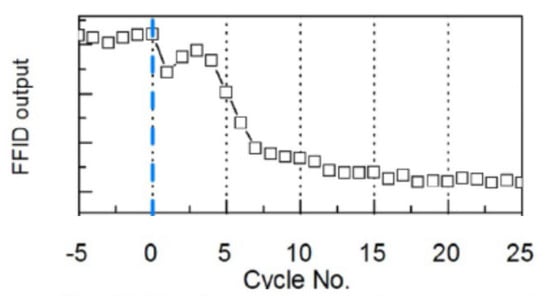

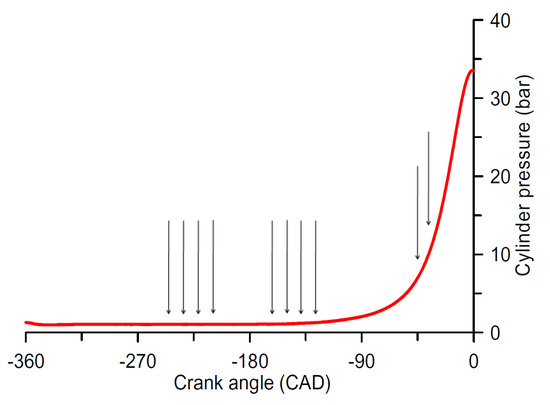

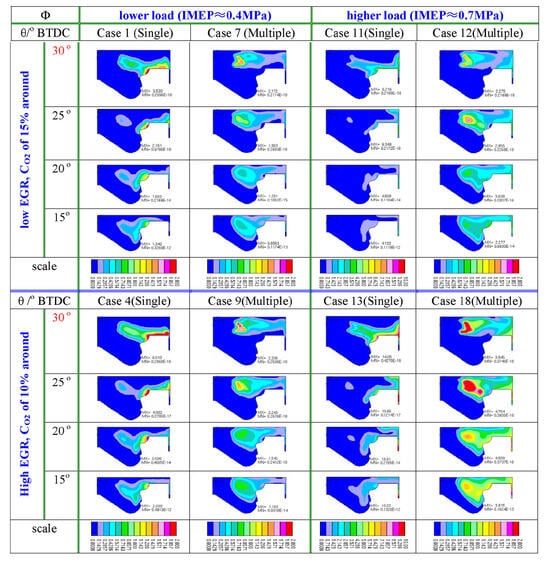

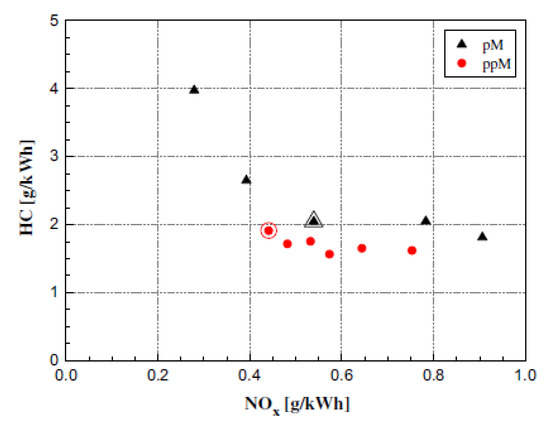

In [15], the effects of the injector driving system on the emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise of an automotive engine have been demonstrated. The considered solenoid injector featured a pressure-balanced pilot valve and was equipped with an integrated minirail of 2.5 cm3, whereas the selected piezo-injector was endowed with a bypass circuit: both the injectors shared the same other hydraulic and mechanical setups (number and diameter of injection holes, needle and nozzle sizes, injector spring preload, etc.). Figure 7 compares the emissions, CN and bsfc of the two injector typologies along an EGR sweep for the 2000 × 5 key point and for a pilot–main–after (pMa) injection strategy. The NOx are always reported as horizontal abscissa in the graphs, and higher NOx emissions always correspond to lower EGR fractions [31]. The ordinate axis of the graphs reports the soot engine-out emissions in Figure 7a, the bsfc in Figure 7b and the CN in Figure 7c.

Figure 7.

Emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise at 2000 × 5: (a) Soot-NOx trade-off; (b) bsfc-NOx trade-off; (c) CN-NOx curve [15].

The optimization of the triple injection strategies with a statistical technique has been carried out for either the IAP or IAS injectors under the same constraints. The combustion mode is the conventional one for the diesel engine equipped with both the IAP and the IAS injectors because a clear soot-NOx trade-off with respect to EGR can be observed for the considered working condition (cf. Figure 7a). The IAP injectors feature a worsened soot-NOx trade-off and an increased bsfc, compared to the IAS injectors. The IAP injectors lead to an augment in the engine-out soot emissions for fixed NOx under the considered pMa injection. The NOx engine-out emissions are also higher for the baseline calibration point (contoured symbol) of the IAP injector. The mean penalty introduced by the IAP injectors on bsfc is around 4%: the differences in injector leakages between the IAP and IAS injectors equipped with a pressure-balanced pilot valve and minirail therefore play a negligible role on bsfc since a 100% reduction in injector leakage generally leads to a bsfc improvement of only around 1% (in the considered tests, the leakage of the IAS injectors was less than double that of the IAP samples). Finally, the CN is about 1.5 dB higher for the engine equipped with the IAP injector in Figure 7c.

In-cylinder analyses show that the peak HRR value is smaller for the IAS injector, probably due to the leaner mixture during the main combustion, and as a result, the combustion noise is lower for the engine equipped with this kind of injector. Furthermore, the globally faster combustion development pertaining to the IAS injector has also been ascribed to the earlier phasing of the after injection in the optimized calibration and is responsible for the improved bsfc. Finally, a critical increase emerges in the numerical soot emission time histories (calculated with a three-zone combustion model) for the engine setup with the IAP injectors during the main combustion because of a possible increase in the Sauter diameter of the fuel droplets during the main injection. The better atomization of the fuel and the leaner mixture at the beginning of the main combustion are both due to the higher needle velocity (cf. the higher injected flow rate values and more rectangular shape of the injected flow rate in Figure 6) of the IAS injector during the initial part of the injection. In fact, since the minirail is able to sustain the injection pressure in the sac, especially during the first part of the injection event, the needle velocity increases in this phase and reduces the droplet mean Sauter diameter. On the basis of the engine results at different engine working conditions, indirect-acting piezoelectric injectors do not show any significant advantages with respect to the solenoid ones when injectors featuring similar hydraulic and mechanical setups are taken into account. Other results can be found in the literature that seem to be contradictory to those found in [15], but this is ascribed to the differences in the hydraulic and mechanical setups of the considered injectors, while the role played by the injector driving technology (piezoelectric or solenoidal) is not pivotal. The conclusion is that in the context of indirect-acting injectors, solenoid injectors remain a preferred solution because of their reduced manufacturing costs, although the costs of piezoelectric injectors have continued to decrease since their introduction on the market.

2.2. Comparison Between Indirect-Acting and Direct-Acting CR Engines

The direct-acting Common Rail technology probably represents the best perspective of piezoelectric actuation. It is a way of obtaining enhanced control of heat release modulation during combustion as well as of providing the functionality required by any used aftertreatment device [32]. The direct-acting technology has already been implemented in production CR systems and its claimed hydraulic benefits are major control of the injected quantities, improved dynamics, accurate and flexible multiple injections, reduction in injector leakage, very high injection pressure levels and flow-rate-shaping capabilities.

In principle, direct-acting injectors generally allow for better control of the injected quantity, mainly because of the possibility of developing accurate feedback control strategies based on the analysis of the current and voltage signals provided to the piezo-stack. Nozzle opening, start of the needle downstroke and end of hydraulic injection can be monitored, and this improves the control of both the injection timing and injected mass. A similar strategy cannot be implemented in indirect-acting injectors: in fact, the electrical commands act on the pilot valve, and it is very difficult to find an accurate spectral transfer function between pilot-valve lift and needle-lift time histories. Furthermore, direct-acting piezoelectric (DAP) injectors are characterized by a very prompt dynamic response with reduced nozzle opening and closure delays.

The demand for higher nozzle pressure levels (up to and beyond 2000 bar) in indirect-acting CR injectors [33] is often curbed by the simultaneous need for reduced injector leakages, that is, the fuel flow rates that occur through the injector when the pilot valve is either open (dynamic leakage) or closed (static leakage). Since there is no pilot valve in direct-acting injectors, the dynamic leakage is null, the static leakage is significantly reduced, and the rail pressure can be increased to very high levels [34] without affecting the hydraulic efficiency of the injection system to any great extent. Obviously, the no return flow also enables the CR high-pressure pump to be downsized and eliminates the need for a recirculated-fuel cooler, at least for fuel-metering valve-controlled injection systems [35].

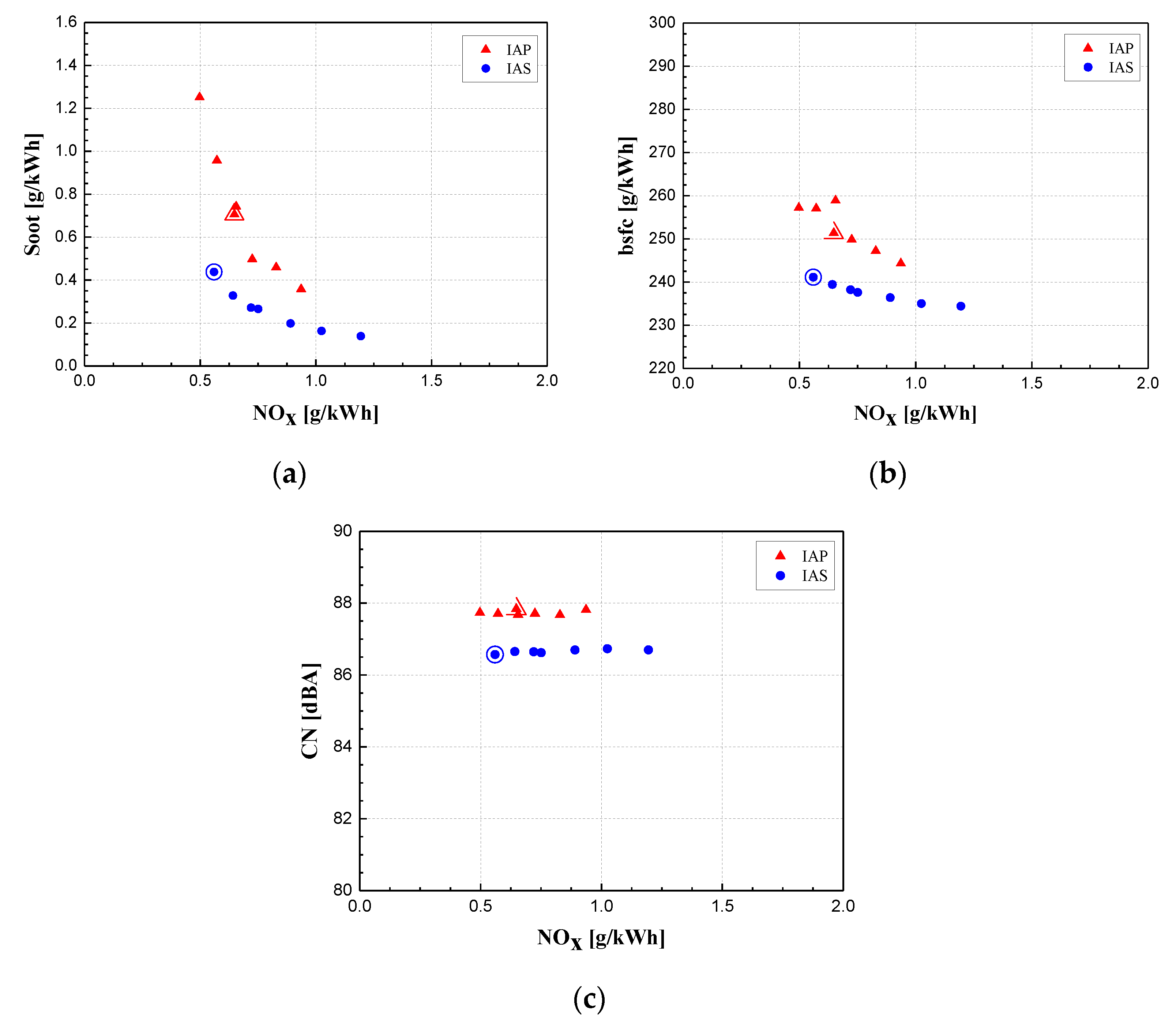

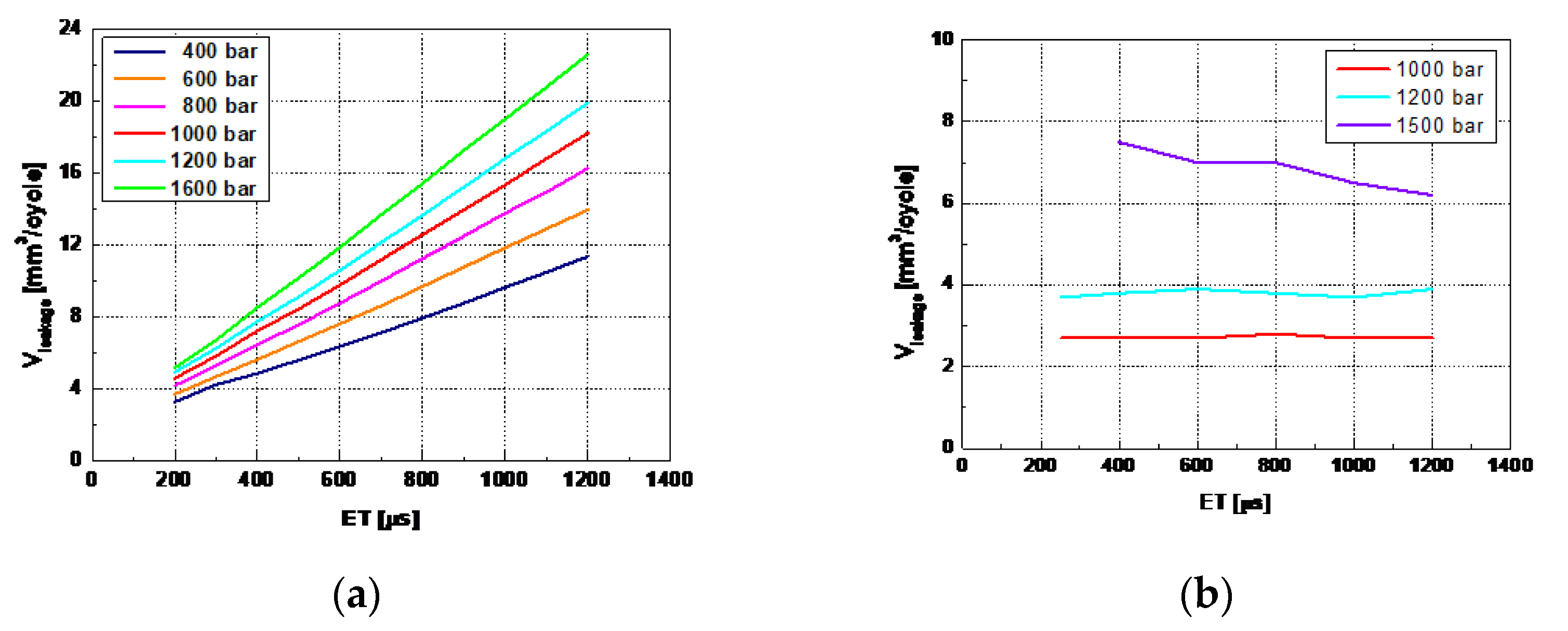

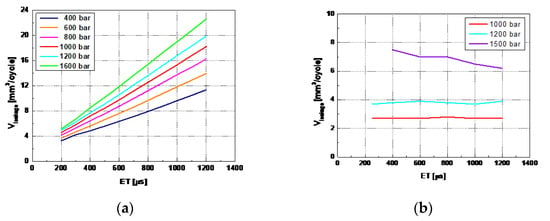

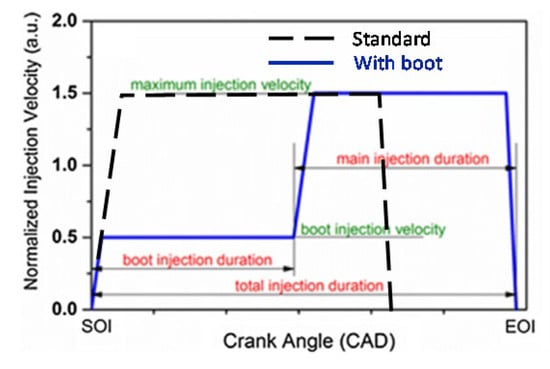

Finally, variable shaping of the injected flow rate in direct-acting piezo-injectors is guaranteed by the possibility of performing a boot injection (cf. Section 2.2.1), which offers additional degrees of freedom for more efficient management of the complex trade-off between emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise [36,37]. All this explains the great attention that has been paid to direct-acting injectors by the automotive scientific community. Despite all the studies on hydraulic performance and fuel spray, which illustrated the features and the potentiality of direct-acting piezoelectric injectors [38,39], there are only a few works that tried to reveal the real benefits of the direct-acting technology of the injector on engine-out emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise. In [40], the hydraulic and engine performances of indirect-acting and direct-acting piezo-driven injectors have been compared under various working conditions with reference to a Euro 5 diesel engine for a passenger car. Figure 8 reports the volumetric injector leakage measured at 30 °C (Vleakage). In the case of the IAP injector, Vleakage is the sum of the static and dynamic leakages per engine cycle. Dynamic leakage increases with the value of ET, whereas static leakage mainly depends on pnom. For the DAP injector, only the static leakage has to be taken into account since there is no pilot valve.

Figure 8.

Emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise at 2000 × 5: (a) IAP; (b) DAP [40].

The total leakage of the IAP injector is generally much higher than that of the DAP injector because of the presence of the dynamic leakage. When ET is low, the total leakage of the IAP injector is mainly due to the static leakage contribution, and its values in Figure 8a become similar to or lower than the corresponding ones of the DAP injector in Figure 8b. The previously mentioned three-way pilot valve layout has been developed to limit the dynamic leakage, thus solving the weak point for the IAP leakage. Figure 9 plots the injection rate (measured as pEVI) and injector-inlet pressure (pinj,in is measured along the rail-to-injector pipe) time histories of the IAP and DAP injectors at pnom = 800 bar, ET = 1000 μs; furthermore, the current time history is also reported. Although ET and the nozzle are the same for the two injectors, the injected mass differs significantly. The DAP injector tends to inject less fuel than the IAP one for fixed ET, due to its reduced needle lift values (this feature is related to the small elongation of the piezo-stack). The injected flow rate of the DAP injector increases with a higher time derivative because the direct mechanical actuation of the needle causes a higher velocity during the upstroke. The nozzle opening delay is similar for the two injectors, and this reveals that modern indirect-acting injectors have a similar responsiveness to that of direct-acting injectors.

Figure 9.

Injected flow rate and injector-inlet pressure time histories (prail = 800 bar, ET = 1000 µs) [40].

For the DAP injector, even though the pinj,in oscillations are significant in Figure 9, the injected mass fluctuations with respect to DT in multiple injections virtually disappear since the needle is not ballistic: the maximum needle lift is always reached, independently of the pilot-injection-induced pressure wave dynamics [30].

Tests made with the DAP injector without the active control strategy of the injected mass proved that the role played by this strategy on the fluctuations of the injected mass with respect to DT was negligible.

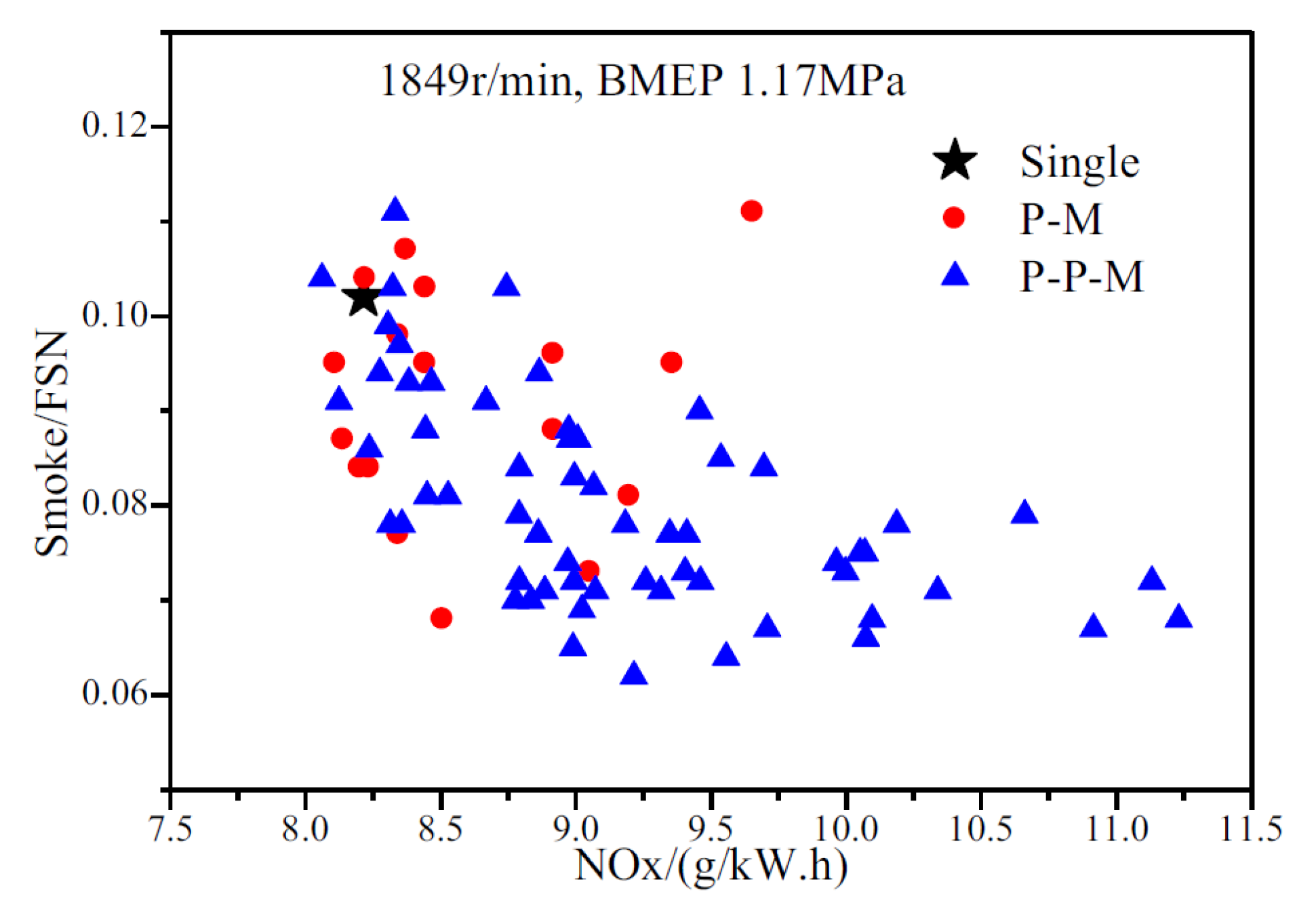

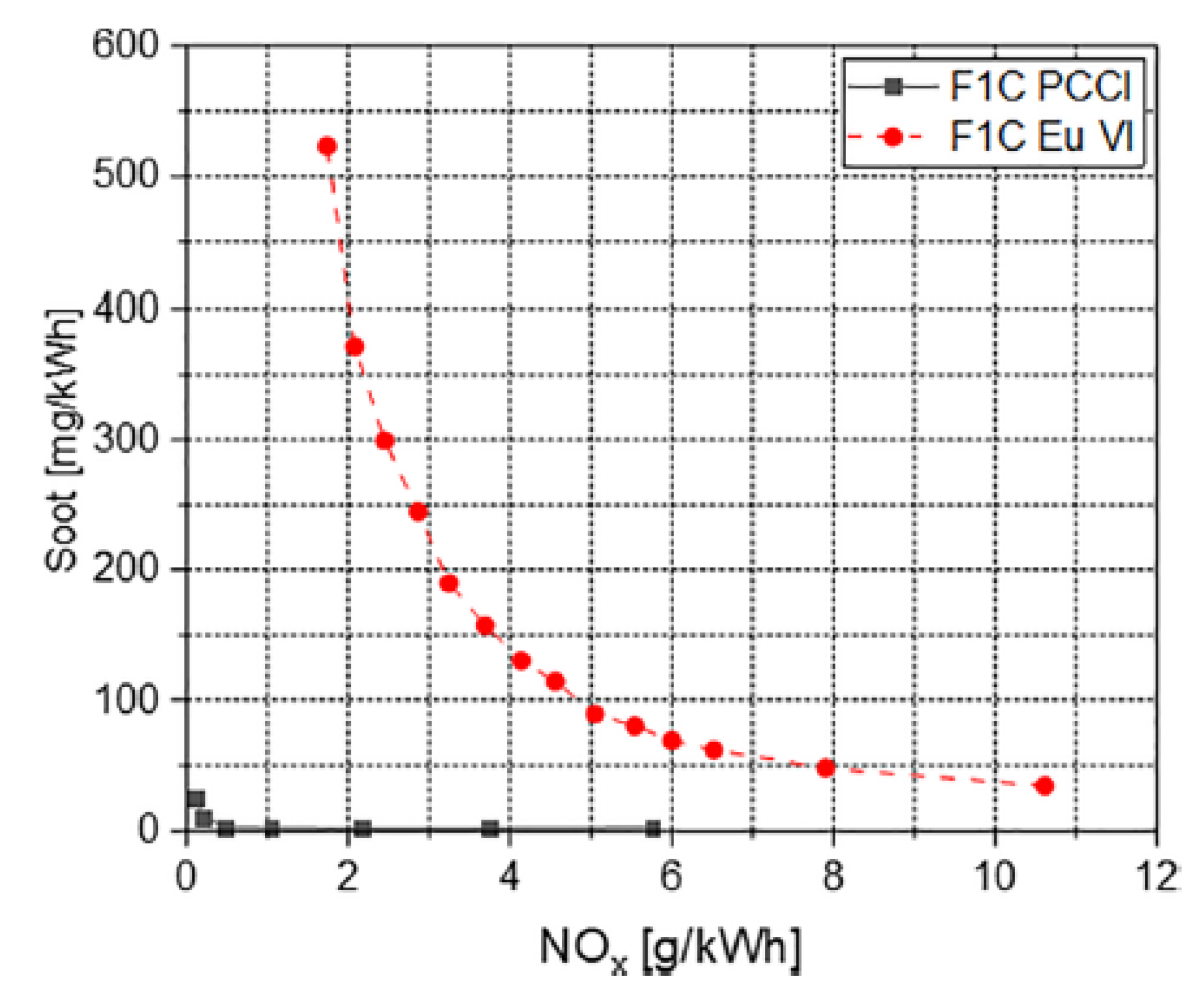

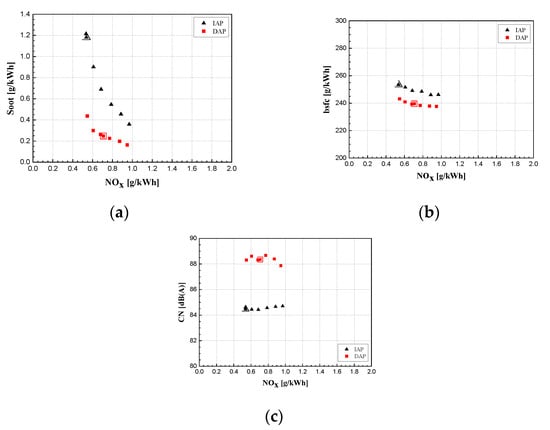

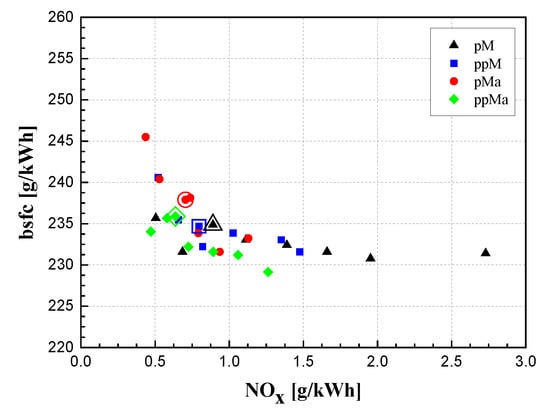

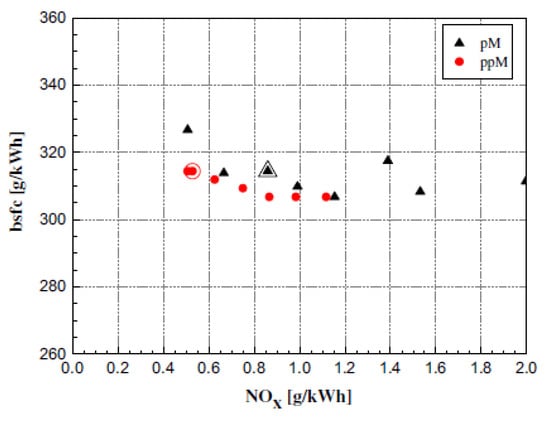

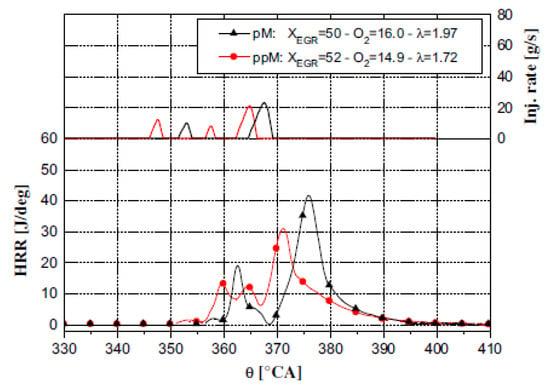

Figure 10 reports the soot, bsfc and CN as functions of the NOx for an EGR sweep performed at 2000 × 5 in the presence of a pilot–pilot–main (ppM) injection strategy, which has been optimized with a statistical technique for either the DAP or IAP injectors under the same constraints The DAP injector improves emissions, bsfc and CN. The significant differences in leakage between the IAP and DAP injectors, which are shown in Figure 8, have an appreciable effect on the bsfc. Indeed, the IAP injector leakage in Figure 8 is more than twice that of the DAP injector for the pnom range and the ET values, which refer to the selected key point in the medium load and speed NEDC zone: this can be responsible for a penalty of 1–2% in bsfc. However, as already mentioned, the application of a three-way pilot valve to the IAP injectors would solve the penalty on bsfc, due to the leakage. The better atomization of the fuel is due to the higher needle velocity (i.e., higher real injected flow rate) of the DAP injector during the initial part of the main injection event [40]. This tends to improve the soot emissions and intensifies the premixed phase of combustion, thus leading to faster combustion with subsequent worsening of combustion noise and improvement in bsfc.

Figure 10.

Emissions, fuel consumption and combustion noise at 2000 × 5: (a) Soot-NOx trade-off; (b) bsfc-NOx trade-off; (c) CN-NOx curve [40].

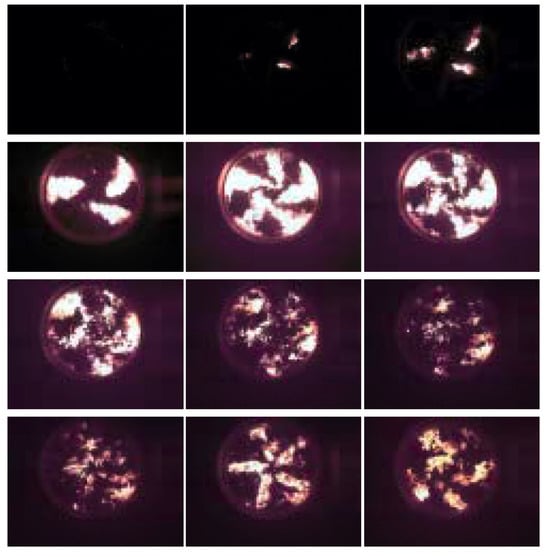

2.2.1. Analysis of the Boot Injection Performance

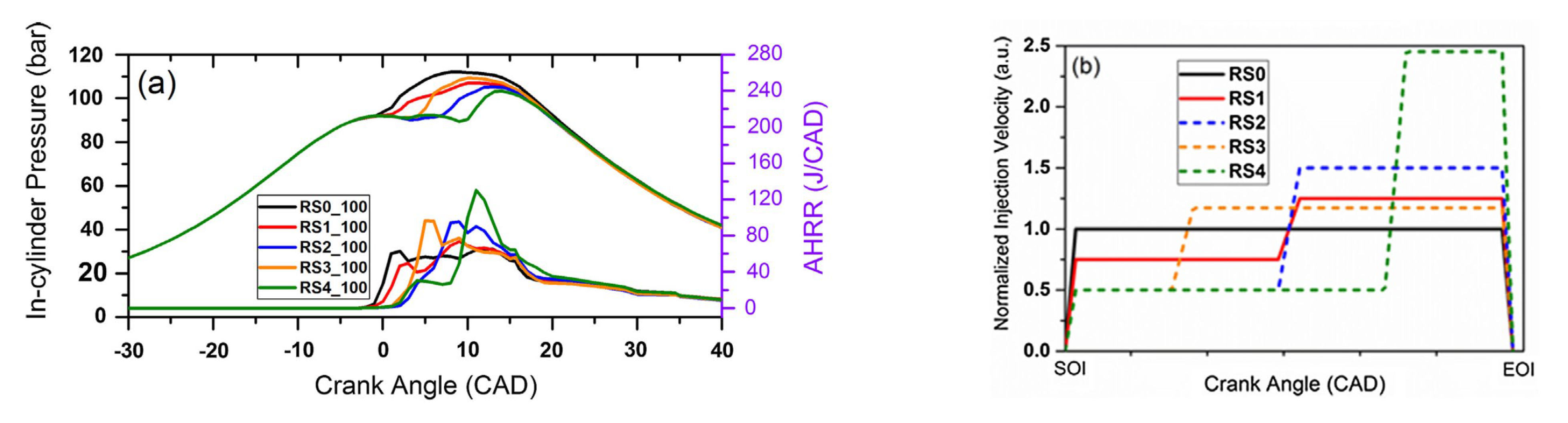

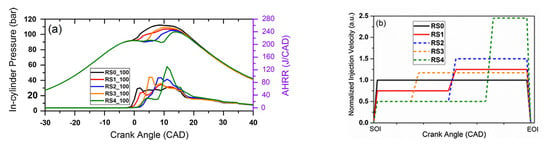

Studies on the effects of injection rate shaping on engine combustion and emissions have been limited. Figure 11 [36] reports, with reference to full load and 2400 rpm, numerical fuel velocities for a rate-shaped injection event (Figure 11b) featuring a boot phase, i.e., an initial phase with reduced constant injection rates, and the corresponding in-cylinder pressure and HRR traces (Figure 11a). Injection velocity is one of the parameters that have the most influence on all of the emissions because it controls both the mixing process and heat release rate. Since the injection pressure in the nozzle is reduced during boot injection because of throttling at the needle-seat passage, lower hole–exit velocities of the fuel droplets occur.

Figure 11.

Simulation results: in-cylinder pressure and HRR traces (a) and corresponding injection rate profiles (b) [36].

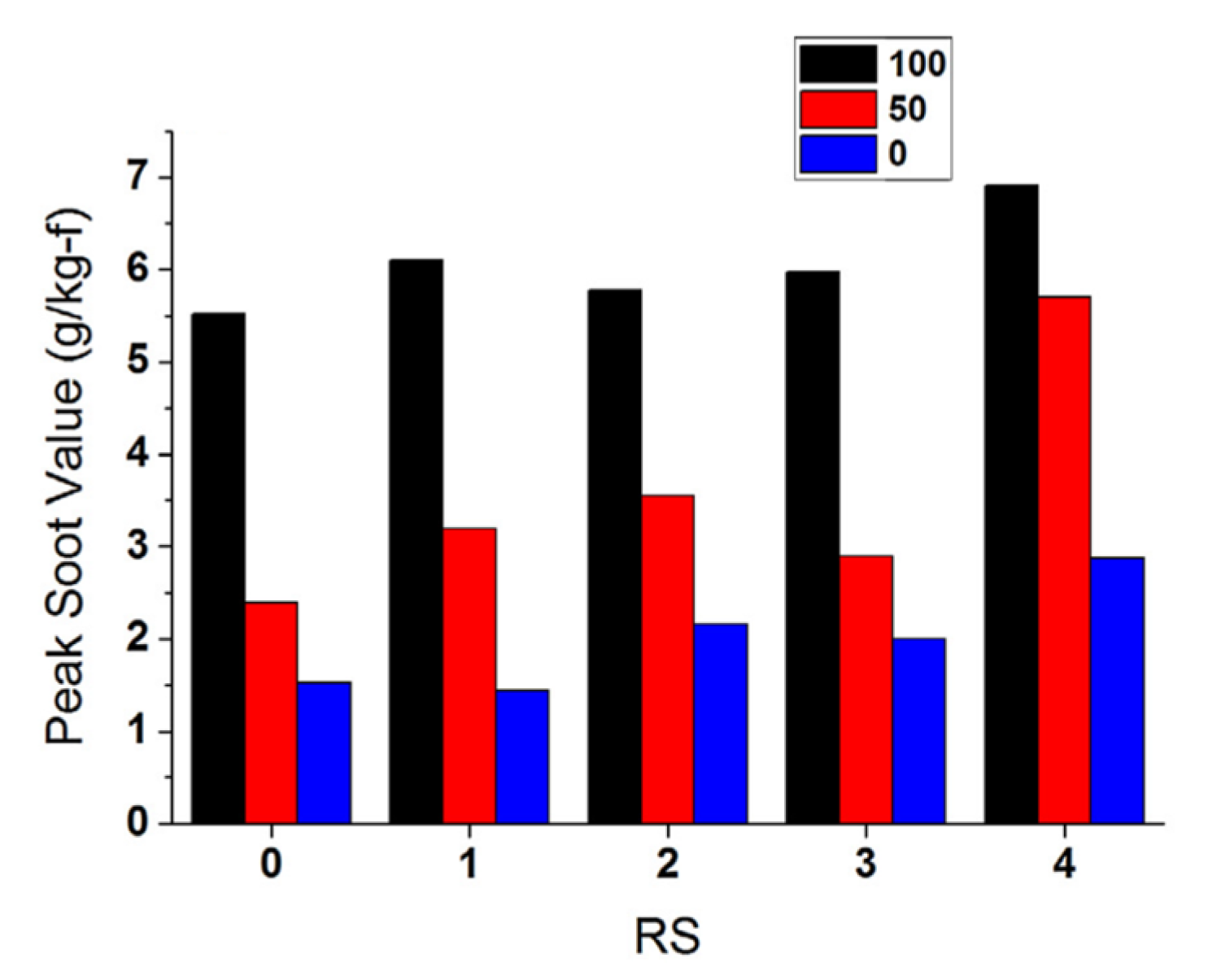

As the boot injection velocity decreases (RS0 to RS1 to RS2) or the boot injection duration increases (RS3 to RS2 to RS4), the ignition delay period increases. Although the reduction in both injection pressure and velocity could extend the autoignition delay, which could lead to a greater amount of fuel being injected before combustion starts, this event has only been shown to exert an influence of secondary importance [41]. In fact, it is the effect of the reduced flow rate over the boot injection period that prevails: hence, the injected mass prior to autoignition reduces in the presence of the boot injection, and atomization is also poorer. As more fuel is injected subsequently, combustion intensifies during the later stages and the peak heat release is seen to shift in the presence of the boot injection rate shapes. In other words, heat released during the premixed combustion phase diminishes, thus determining a significant reduction in combustion noise, while heat released during the mixing-controlled combustion phase increases [38,41].

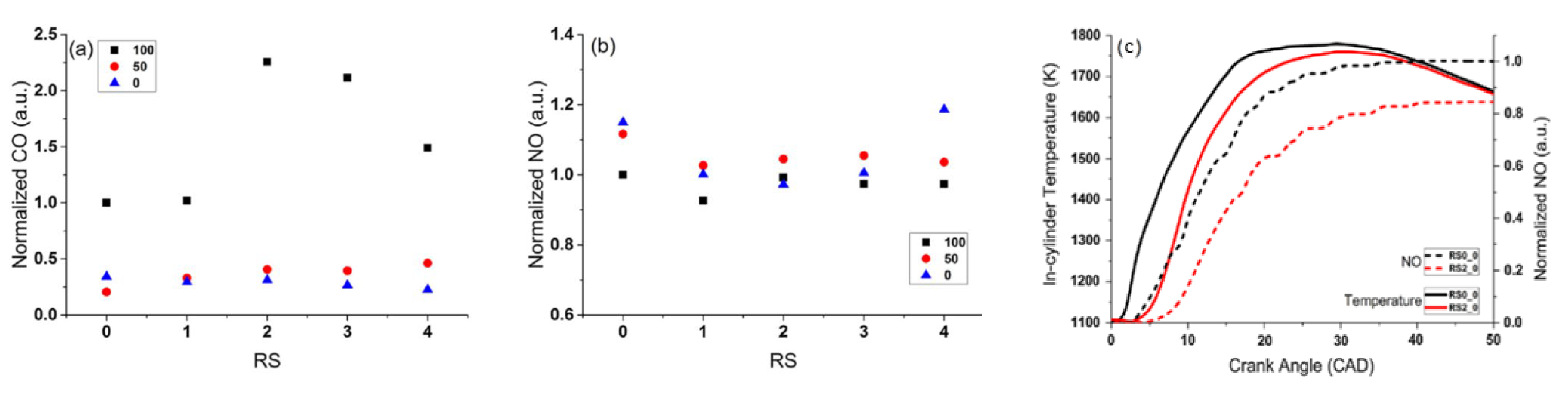

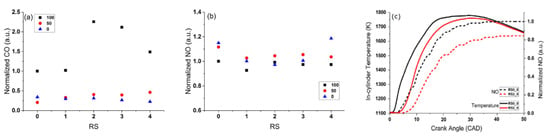

Figure 12a,b shows the simulation results for the normalized CO and NO emissions of all the injection velocity profiles in Figure 11b (only black symbols are of interest because they pertain to pure diesel fuel) and also includes the in-cylinder temperature and NO crank angle evolutions for the RS0 and RS2 cases (cf. Figure 12c), which however refer to kerosene as a fuel (the differences, compared to petrodiesel, show lower kinematic viscosity, by 35%; lower density, by around 4%; lower surface tension, by 8%; lower cetane number, by around 20%; and lower volumetric fraction of aromatics, by around 60%). NOx emissions are generally seen to decrease slightly when boot injection rate shapes are used in place of the conventional rectangular injection rate, i.e., RS0. Boot injection should determine lower injected flow rates and thus lower local temperatures in the initial premixed combustion, which in turn influence the subsequent maximum temperature values in correspondence with the diffusion flames, thus limiting NOx emissions. Figure 12c shows that the RS2 case has an overall lower in-cylinder temperature than the RS0 case, which may imply that there are fewer local high-temperature regions during the combustion of the RS2 case, as compared to the RS0 one. The lower overall in-cylinder temperatures determined by the boot injection are also the cause for the higher CO emissions of the boot-shaped profiles.

Figure 12.

Simulation results on the effect of different injection rate profiles on emissions and in-cylinder temperatures [36].

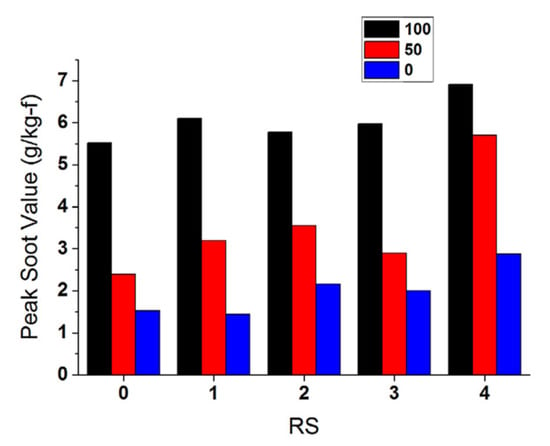

Figure 13 reports the numerical soot peak values for the rectangular injection rate and boot injection rate shapes (cf. black bars). More soot is generally generated when the boot injection is implemented. The diminished injection pressure and velocity of the fuel droplets under early-injection conditions decreases the depth of the spray penetration [42], leading to reduced air-to-fuel mixing, although the reduced fuel momentum during the initial stage of the injection can avoid liquid fuel wall impingement and flame quenching [38]. Once fuel ignition has occurred, the feeding of more fuel to the combustion process, that is, the passage from boot injection to the subsequent injection phase, in which the needle is completely open and the injection pressure increases (in Figure 11b, during this phase, the fuel velocity is larger for the case with the boot than for that without it), allows for the mixing of fuel with air to be enhanced and soot to be contained [43]. In fact, the temperature levels rise in the late burn out phase, and this leads to good oxidation of soot, even though the peak temperature during premixed combustion is lower than in the absence of boot injection. On the other hand, the increase in the fuel pressure during the last part of injection augments the risk of interaction between the injected fuel and the combustion flames, thus increasing the probability of soot formation.

Figure 13.

Simulation results on the effect of different injection rate profiles on soot peak values [36].

As far as the particle sizes are concerned, when boot injection rate shapes are used, it is reported in [36] that larger soot particles are formed at the beginning of the injection for the boot injection profiles as compared to that of RS0 (cf. Figure 11b), due to the lower boot injection velocity. On the other hand, in the final part of the profile, the boot injection rate shapes corresponding to Figure 11b give relatively smaller soot particle sizes than the RS0 profile, due to the higher main injection velocity. As a result, the soot mass distribution with respect to the particle size is narrower for RS0 than for the flow rates with boot injection in Figure 11b.

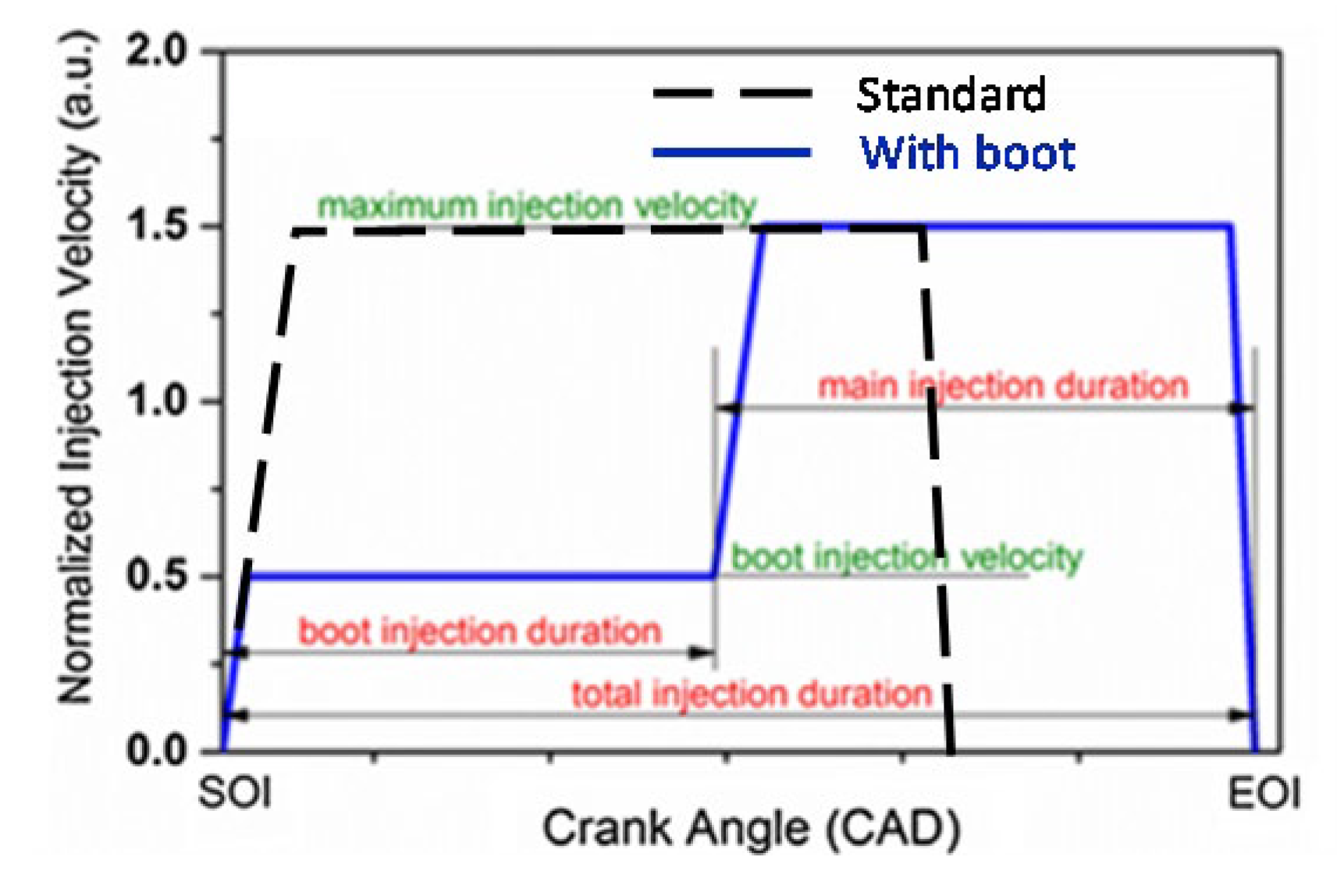

Although the injection velocity profiles reported in Figure 11b and the corresponding numerical analysis made in Figure 11a, Figure 12 and Figure 13 are interesting as an explanation, the comparison between boot injection rate shapes and original injection should be made according to the scheme in Figure 14 in order to reproduce the real conditions. In particular, there is only one level for the main injection, which corresponds to the needle at the stroke-end and the injection duration cannot be the same for the injection flow rate with and without boot if the comparison is made at constant load. Since the difference between the fuel injection velocities of the profiles with and without boot is maximized during the early injection phase in Figure 14, the corresponding reduction in NOx emissions and the penalty in the soot emissions, compared to the case without shaping, are expected to be significantly higher than in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Furthermore, NOx, smoke emissions and bsfc generally vary more significantly at low and medium loads than at full load when a boot injection is added [44]. The experimental results reported in [45] show that the addition of the boot phase at part load leads to a reduction in NOx emissions of about 50% and in CN of 6dB (boot injection reduces the fuel spray momentum in the initial injection phase and this lowers combustion noise) with an increase of only 1% in bsfc. The latter is due to the increase in the injection duration and thus in the combustion time when the rate-shaping strategy is applied. Although the entity of benefits and penalties related to the introduction of the rate shaping depends on the engine working point and on the difference between boot injection and main injection flow rates, it can generally be concluded [46] that the boot injection reduces NOx without a huge detriment to soot formation and fuel consumption in most cases. In general, actions should be taken to avoid any excessive lengthening of the injection, due to injection rate shaping, in order to limit both engine-out soot emissions and bsfc from becoming too much worse [47].

Figure 14.

Boot injection profile according to real conditions [36].

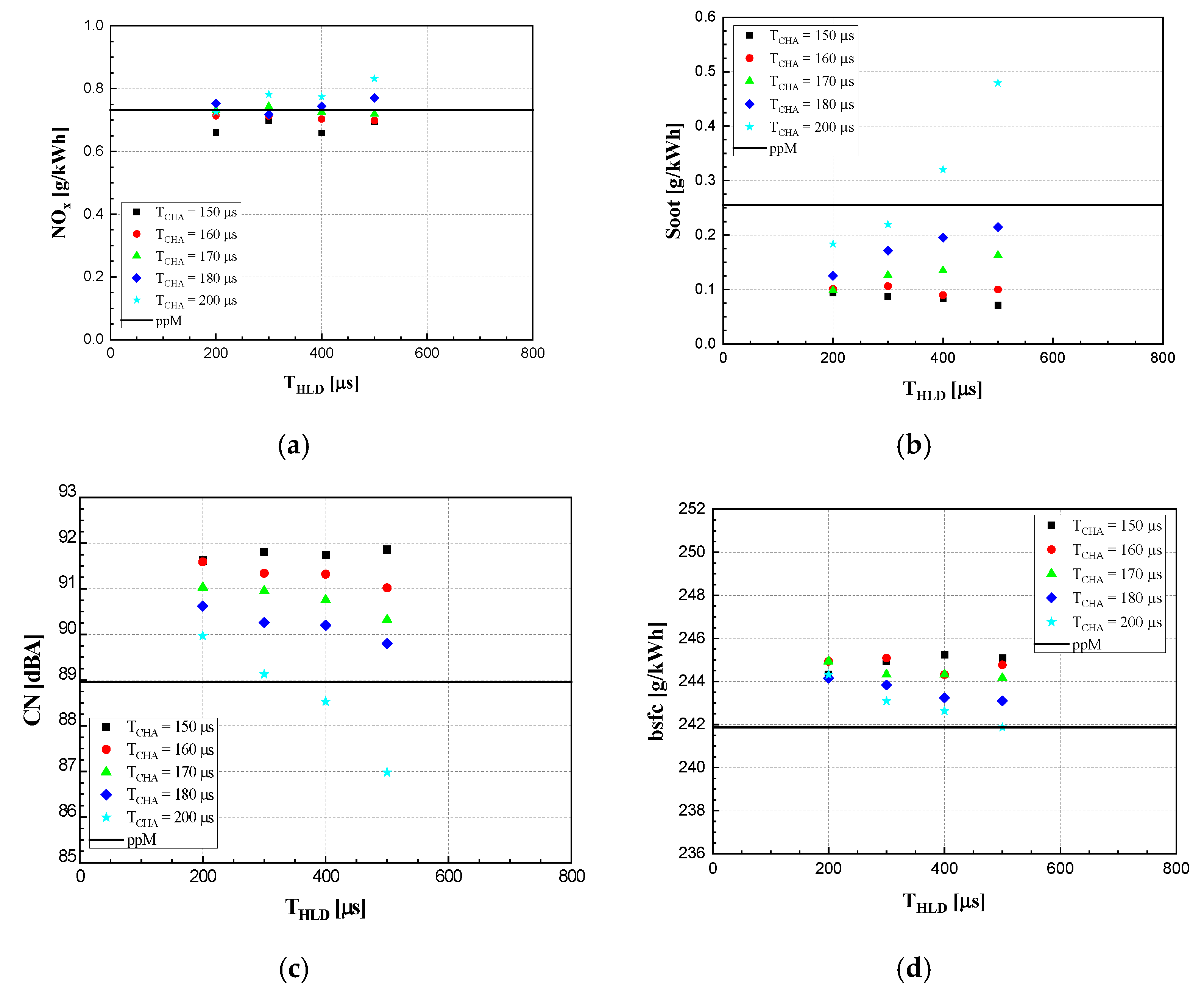

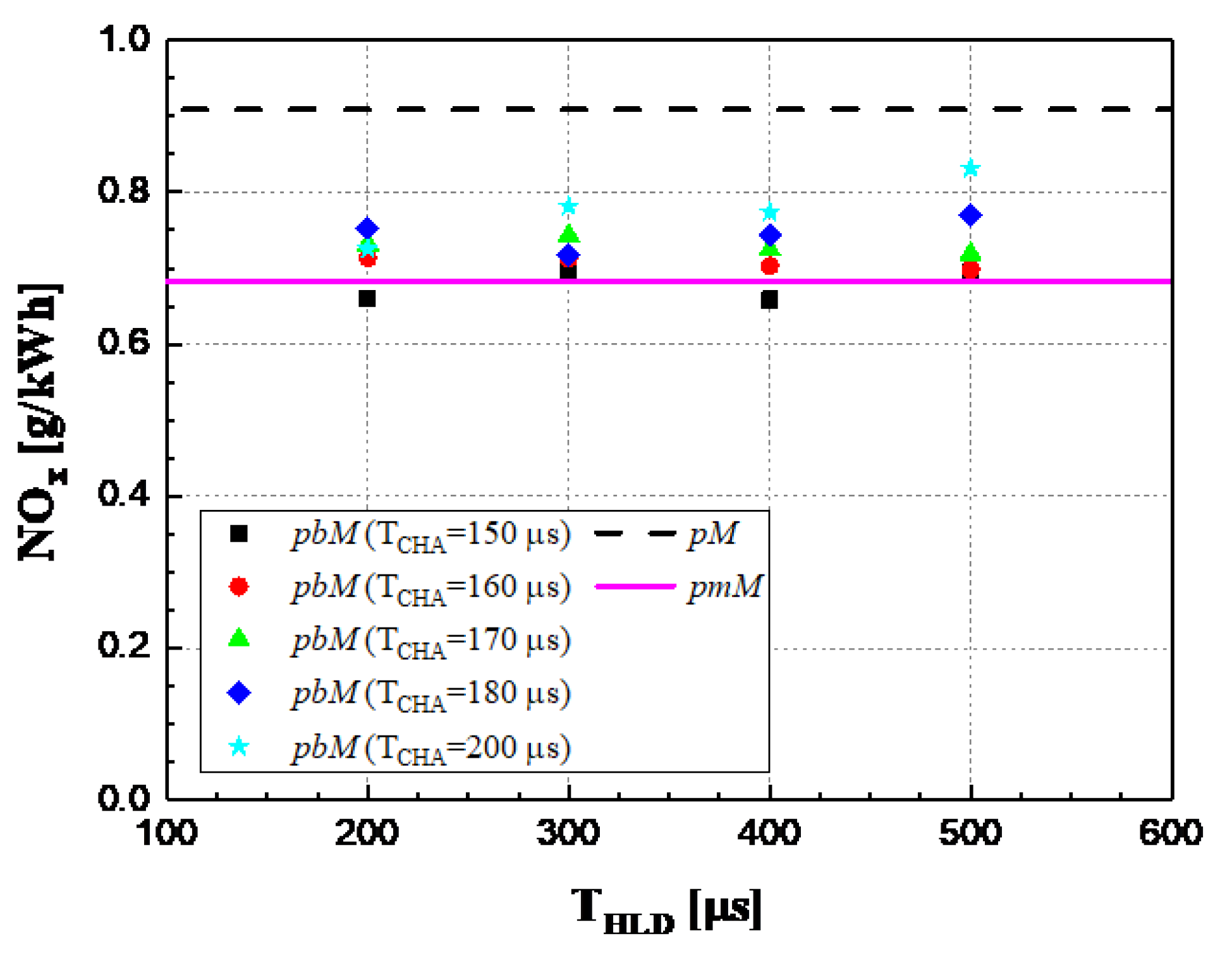

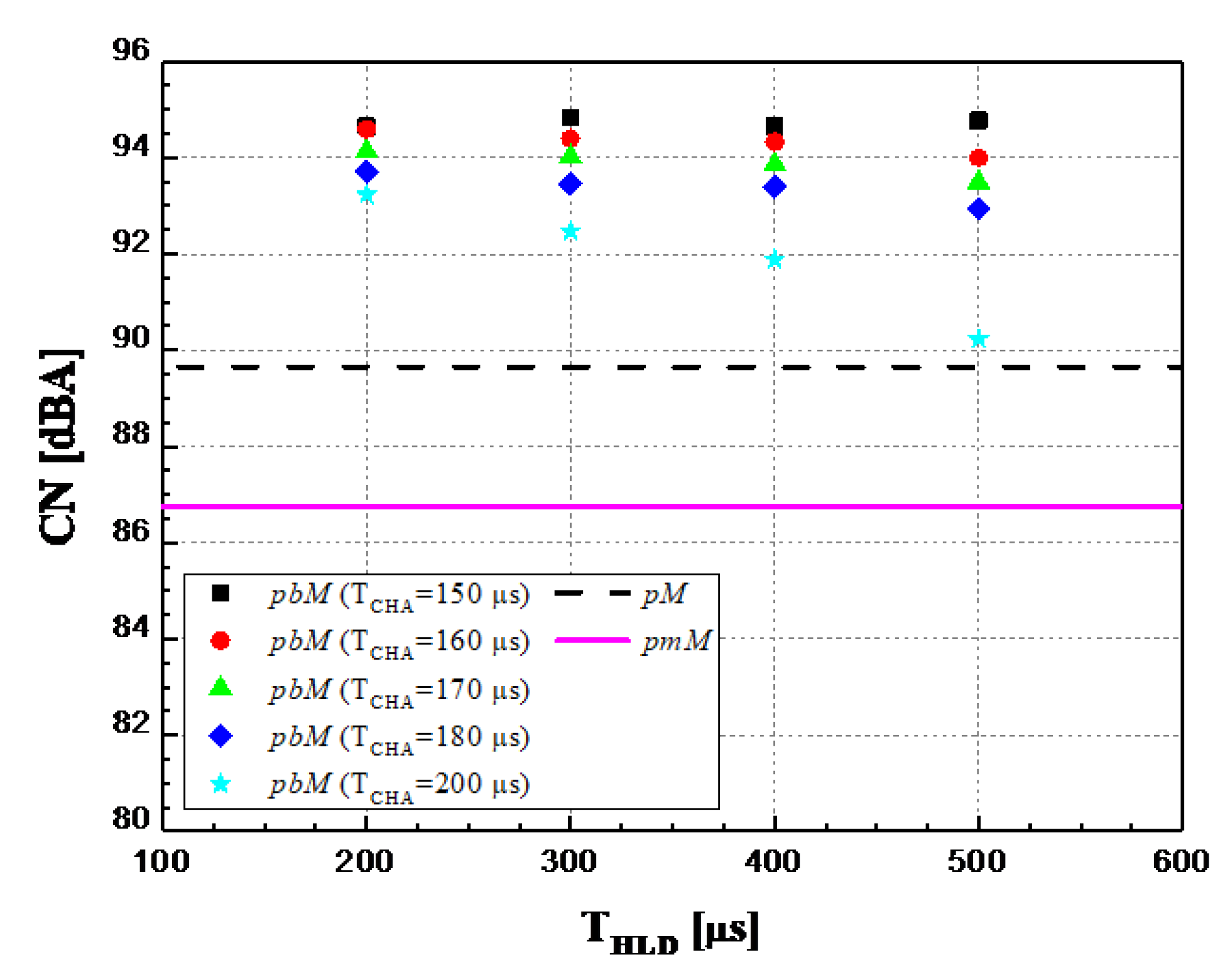

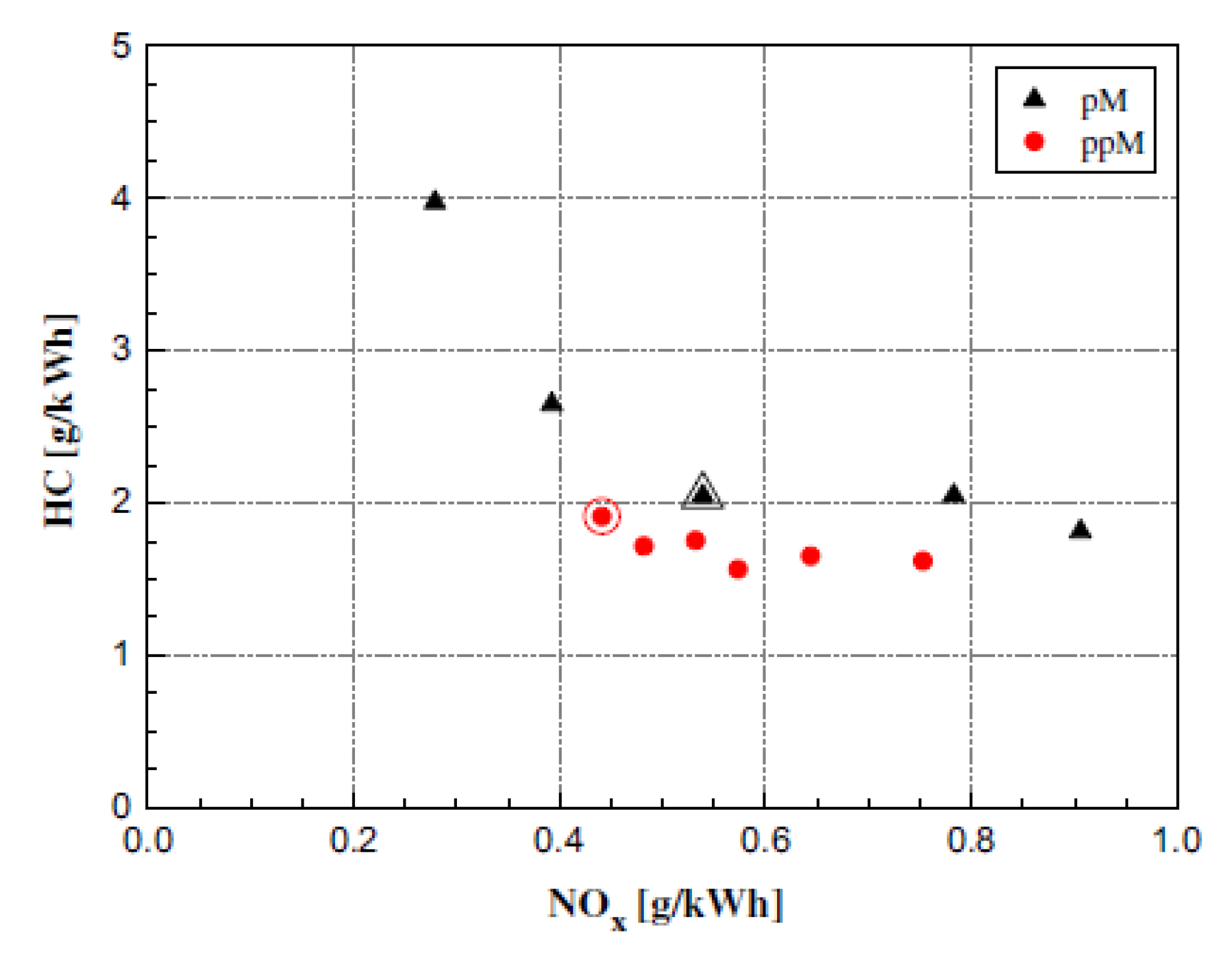

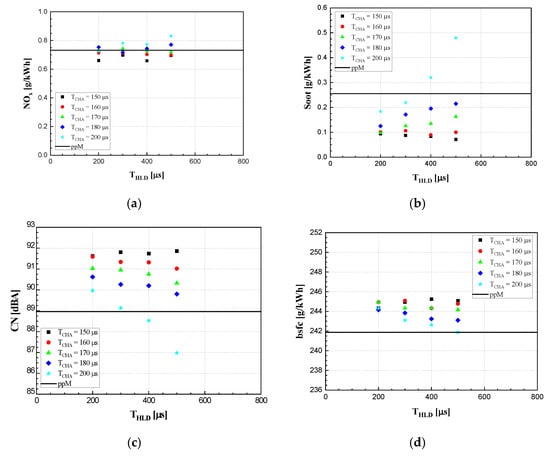

In Figure 15 [40], the engine performance of the pilot–boot–main (pbM) injection schedule, which has been implemented on a DAP injector with different combinations of TCHA and THLD, has been compared with that of the ppM strategy performed on the same injector. The statistically optimized calibration of the DAP injector for the ppM injection schedule has been used as a reference for the implementation of injection rate-shaping strategies. In other words, the boot injection was considered as a pilot shot fused with the main shot and the optimization of the pbM was assumed to be similar to that of the ppM because, in the latter strategy, the later pilot was phased very close to the main injection. When TCHA or THLD are varied, SOImain is also changed in order to maintain the same combustion barycentre (MFB50) as in the original ppM calibration.

Figure 15.

Pilot–boot–main injection profile at 2000 × 5: (a) NOx; (b) soot; (c) combustion noise; (d) bsfc [40].

The different combinations of TCHA and THLD lead to an increase in the bsfc (only in one case bsfc does not worsen) and also in the HC engine-out emissions (not reported) compared to the ppM strategy. Furthermore, the effect of the boot parameters on the NOx engine-out emissions is not significant, and these emission values are similar to those referring to the ppM strategy. Finally, a clear trade-off exists between CN and soot engine-out emissions with respect to the boot-injected quantity.

In short, the benefits of the boot injection are not obvious, compared to an optimized triple injection. The effect of the boot injection is obvious when a single shot is shaped; instead, if the basis is a pilot–main injection, the addition of a boot phase to the main injection (pbM strategy) does not give a clearly better performance than the addition of a second pilot shot between the main and original pilot injections (ppM strategy).

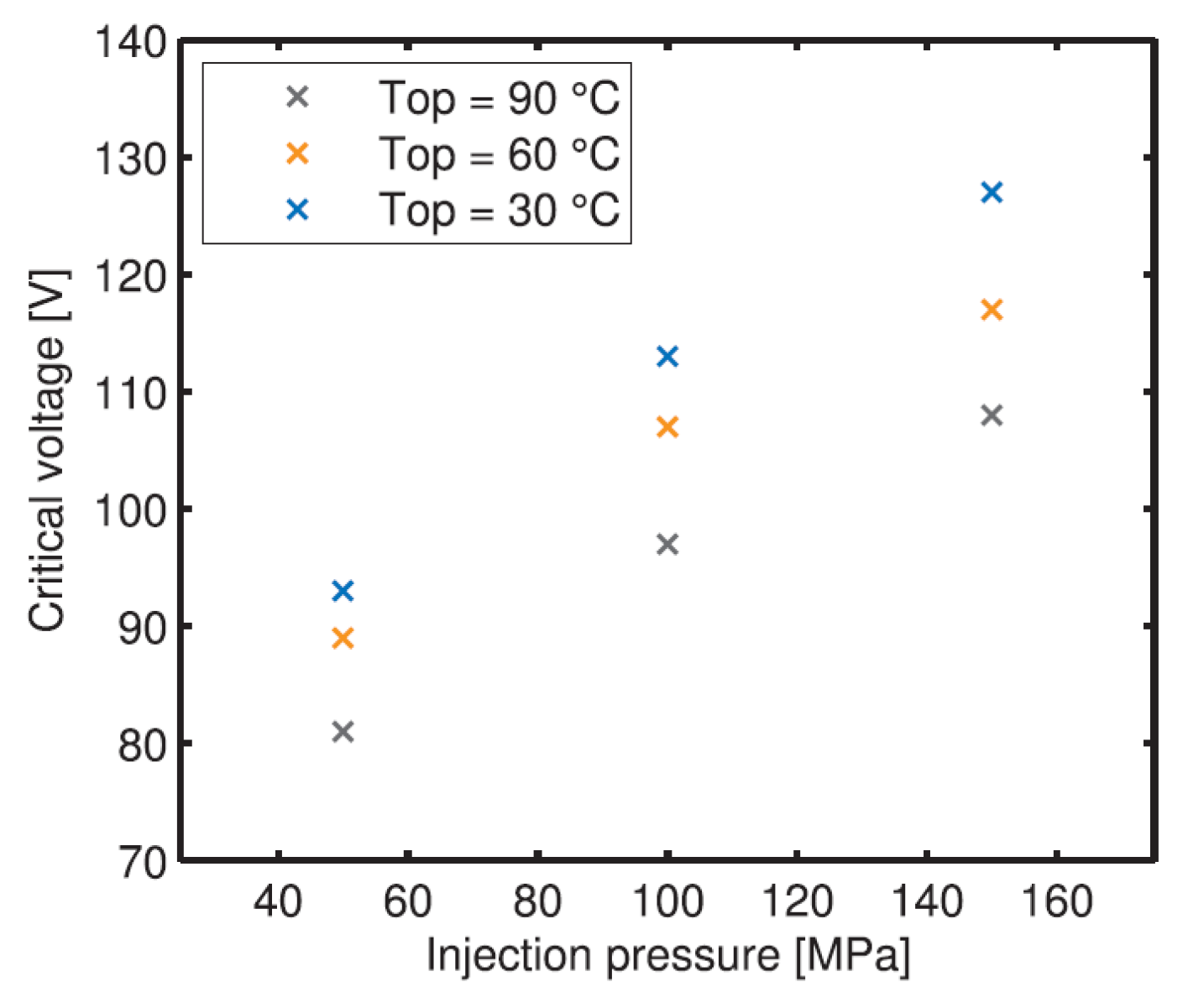

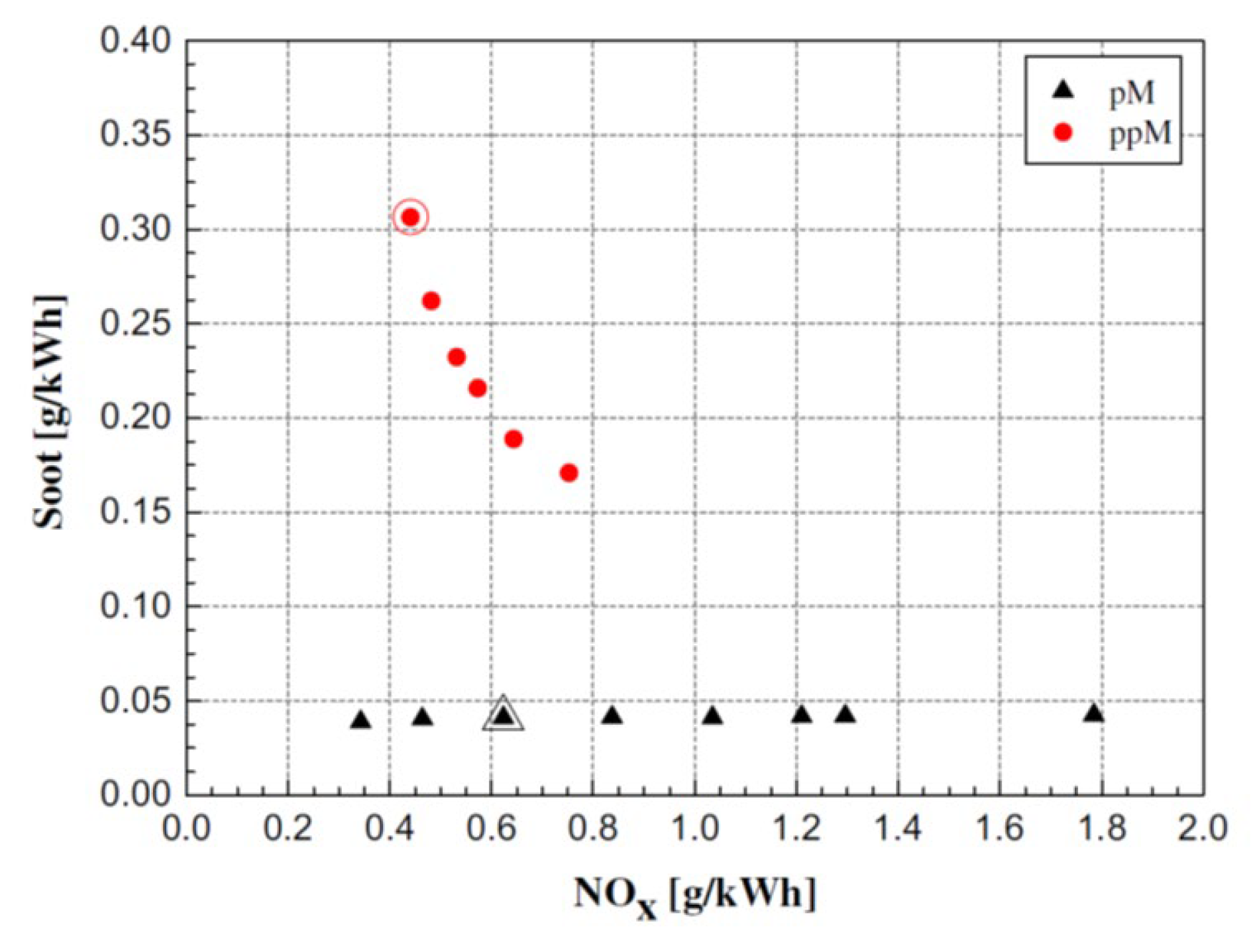

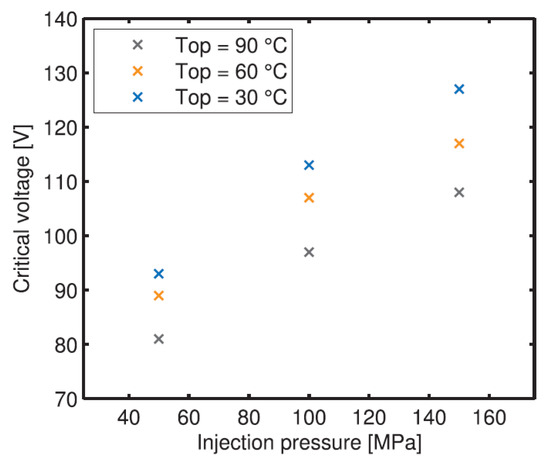

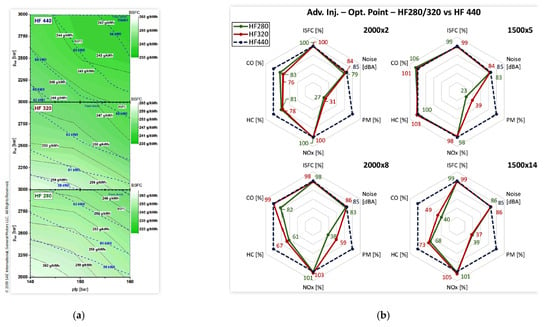

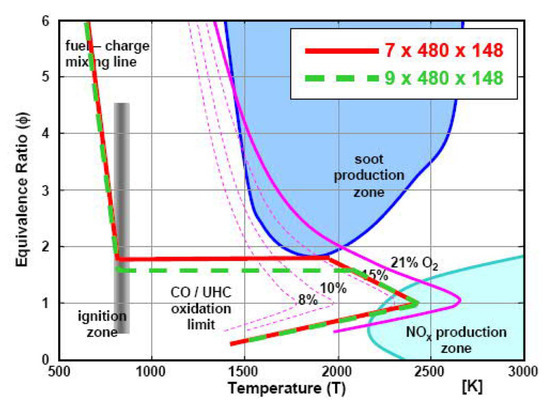

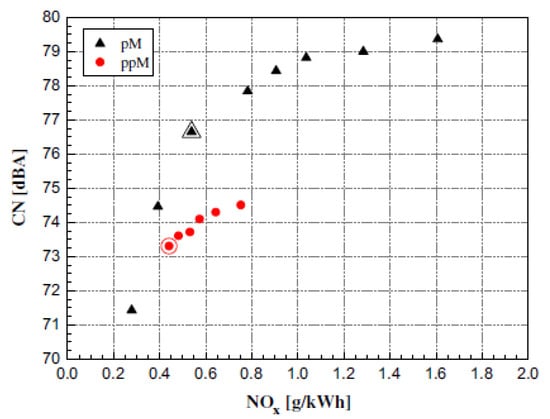

Figure 16 [32] reports the critical voltage of the piezo-stack at different operating conditions. The critical voltage is the level above which the fuel flow rate can be smoothly controlled with the charge sent to the injector: below this value, the cycle-to-cycle variation in the injected mass becomes larger. The boot injection is operated at part lifts and requires reduced charges and reduced voltages below the critical value. The regulation zone of the mass flow rate with the charge is therefore not smooth; the injector performance is affected by temperature and rail pressure; and the compensation is more subjected to errors, largely reducing the effectiveness of the boot injection. In other words, it is challenging to precisely dose the small values of electrical charge that must be provided to the piezo-stack to control the needle at part lifts of tens of micrometers. As a result, there is noticeable cycle-to-cycle and injector-to-injector dispersion in the value of the boot injection rate [48]. These problems do not exist in the management of small pilot injections, the implementation of which therefore is more efficient. It is therefore possible to conclude that at the current stage of the technology, the significant advantage of the DAP injectors consists of an increase in the maximum injection pressure, due to the reduced static leakage and of an improvement in the injected flow rate pattern during the nozzle opening phase (the flow rate steepens). However, the latter change in the injection rate pattern, compared to the standard IAP can also be achieved without introducing the direct-acting technology. In fact, similar improvements as those documented for the DAP injector can be obtained if an indirect-acting injector is equipped with an integrated minirail, that is, with an enlarged delivery chamber of about 2 cm3 [15,49]. This is proved in Figure 17 [50], where soot–NOx trade-off and bsfc of IAS, IAP and DAP injectors have been compared at n = 2000 rpm, BMEP = 5 bar (2000 × 5) with reference to a pilot–main (pM) injection, with the IAS being equipped with a minirail. The engine was originally set up by the OEM with IAP injectors, and a state-of-the-art pM injection calibration was adopted. The experimental tests were then replicated with DAP and IAS injectors, keeping the same fuel injection calibration as that of the IAP injectors. As can be inferred, the emissions and the bsfc of DAP and IAS injectors are similar, whereas the CN of the DAP is the worst. Although the calibration was optimized on the IAP samples, the performance of the IAS injectors with the minirail is globally better than that of the DAP ones.

Figure 16.

Critical voltage at different rail pressure levels [32].

Figure 17.

(a) Soot, (b) CN, (c) bsfc; (d) HC versus NOx (EGR sweeps) at 2000 × 5 for IAS, IAP and DAP injectors [50].

2.3. Basic Double-Injection Schemes

A multiple-injection strategy adopted to replace a single fuel injection shot with multiple discrete fuel injection events of reduced sizes, can easily be implemented using Common Rail systems, equipped with modern injectors. These injectors can control small injected fuel quantities, despite pressure waves, and guarantee superior flexibility in the management of the dwell time between subsequent shots, in order to fulfil the recent and new emission standards. The multiple injection technique is very attractive because it allows for better control of combustion without significantly increasing the engine complexity and costs. In diesel engines, combustion basically starts with a premixed phase and then develops into a diffusive one. Fractioning the injected fuel affects the ignition delay and the durations of the premixed and diffusive stages; this, in turn, strongly affects pollutant formation, engine efficiency and combustion noise [3].

Three fundamental modes of multiple injections can be distinguished, namely pilot, after and split. A pilot injection is a short injection that precedes a longer main injection; an after injection is a short shot that comes after a main injection; and a split injection is simply a main injection divided into two or more parts, none of which can be classified as a pilot or after injection since all the shots inject large masses and have typical timings of main injections [51]. One definition of a pilot or after injection found in the literature is that it contains less than about 20% of the total fuel injected in the double injection [52].

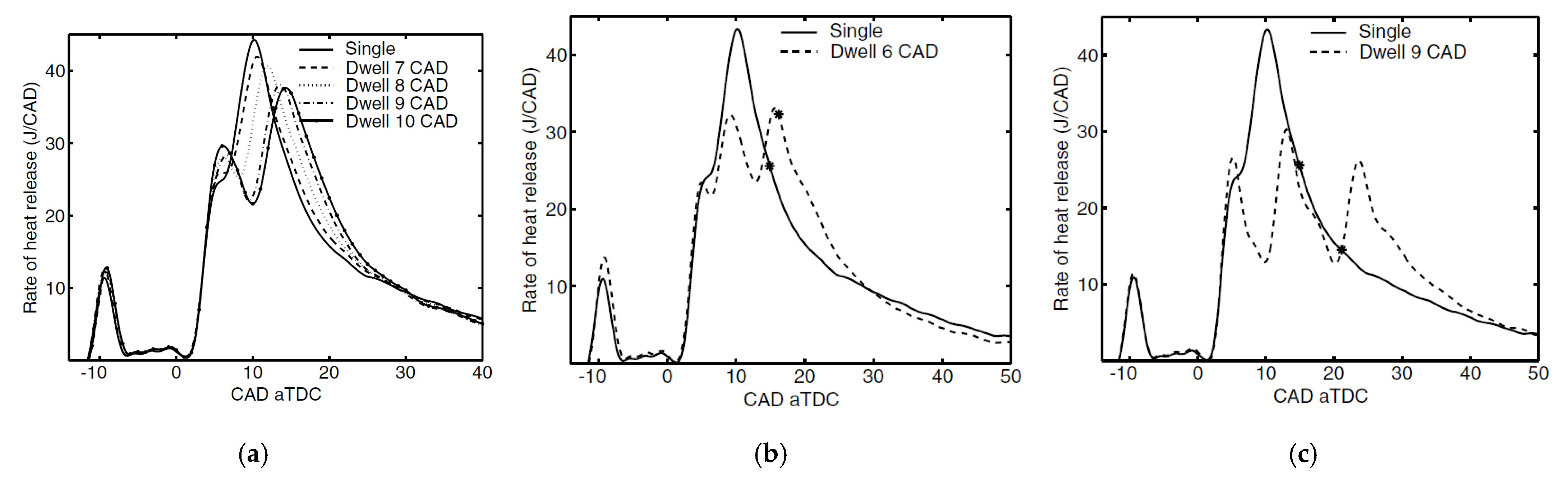

2.3.1. Pilot–Main Injection Mode

The combustion of the pilot injected fuel causes a slight increase in the in-cylinder gas pressure and temperature before the main injection has occurred and therefore leads to a considerable reduction in the ignition delay of the main injection [53]. This reduction in the fuel ignition delay limits the impact of the premixed combustion and generates a less rapid heat release rate [51] during the main injection than in a single-injection schedule [54]. The last effect is also related to the oxygen quantity consumed during the pilot combustion and to the consequently reduced oxygen availability during the main combustion. Furthermore, the high thermal capacity products of the pilot combustion can be entrained in the main fuel spray and play the role of an internal EGR, thus lowering the HRR peak. As a result, the main combustion becomes predominantly mixing-controlled [51] and the entire amount of fuel chemical energy is released over a prolonged time interval, thus determining a longer combustion than for the single-injection case.

Pilot injections are effective in decreasing combustion noise, especially at idle, low and medium loads, by lowering the HRR peak of the main combustion, and this is often referred to as their primary benefit [55]: reductions of up to 5–8 dB are generally obtained in the CN value, compared to single-injection strategies, over the whole engine working area, even though the most obvious benefits are obtained at low loads and at idle [56], where the fuel ignition delay is larger. Combustion noise normally decreases if the pilot injected mass increases, whereas the dependence of CN on the pilot–main dwell time is more complex because this trend is affected by the entity of the pilot injected mass, even though a decrease in combustion noise is generally observed as the dwell time is reduced [57].

The discussed effects of the pilot injection, i.e., diminution in the ignition delay and reduction in CN, are typically achieved at low and medium loads when the pilot injection is performed with SOIpil in the 5–25 CA BTDC range. When SOIpil is in the 25–40 CA BTDC range, it is referred to as an early pilot in the context of conventional diesel combustion (these injection timings were traditionally typical of low-temperature combustion): the fuel fraction burned in the premixed phase is greater than in the case without an early pilot. This can help to obtain more homogeneous air–fuel ratios and temperature distributions within the combustion chamber, thus limiting the NOx and soot production, according to a milder approach than that of LTC. Hence, two opposite effects can be ascribed to the pilot injection, depending on SOIpilot.

In general, the pilot injection helps to better modulate the energy release over a longer time interval and, although it burns under premixed conditions, it reduces the premixed phase of the main combustion and therefore makes the highest flame temperature diminish. As a consequence, the NOx emissions generally also reduce, compared to the single-injection case. In general, a larger pilot injected mass with an earlier SOIpil has almost the same shortening effect on the ignition delay of the main injection as a smaller pilot injection with a more delayed injection timing. The benefits also depend on the adopted engine calibration and on the EGR rates: when higher EGR rates are employed (up to 30–40% for conventional combustion), SOIpil and pilot mass influence the NOx emissions to a lower extent because NOx emissions are smaller [58]. Since the pilot injection, almost independently of its timing, burns with long ignition delay and under premixed combustion conditions [55], the pilot injected fuel combustion could constitute an additional source of NOx emissions, which is negligible for small pilot injected masses. However, when large pilot injected quantities are applied, the increase in NOx, due to pilot combustion, can prevail over the decrease in the main combustion NOx, due to the shortened ignition delay and less intense premixed main combustion [59]; as a result, NOx emissions can globally increase for the strategy that implements the pilot shot. Furthermore, the earlier SOIpil, which corresponds to a fixed pilot injected mass, the lower the HRR peak of the pilot injection, and thus, the more moderate the pilot combustion. Indeed, the presence of a large number of leaner mixture zones in the pilot injected fuel spray at more advanced pilot injection timings causes a slow combustion, which in turn leads to lower pilot injection NOx emission levels (NOx is not produced with an equivalent ratio of 1.2 or smaller [60]). This suggests that an earlier SOIpil in conventional combustion limits the generation of NOx caused by pilot combustion [61], although this strategy aggravates the NOx emissions in the main combustion.

The smoke emissions of the pilot–main injections generally tend to increase, compared to the single injection, in the classic theory of emissions [62]. In fact, the pilot injection increases the in-cylinder temperature and decreases the oxygen concentration in the gases before the main injection has occurred. Both of these effects generally make the smoke emission formation grow; in particular, the increased temperature mainly acts by reducing the lift-off length (this is defined as the shortest distance between the nozzle tip and the stabilized combustion flame, cf. Section 4.2.4), which pertains to the main injection, with a subsequent increase in the equivalence ratios close to the nozzle. The insufficient mixing of fuel with air, which is due to the shortened ignition delay of the main injection, augments the percentage of diffusion combustion in the main combustion, and as a result, the amount of engine-out soot can grow significantly [61]. The pilot injected quantity should be below a certain threshold (a general value of 4–5 mg is normal) in order to contain the amount of smoke [63], and a small mass of pilot injected fuel will not vary the PM emissions appreciably [64].

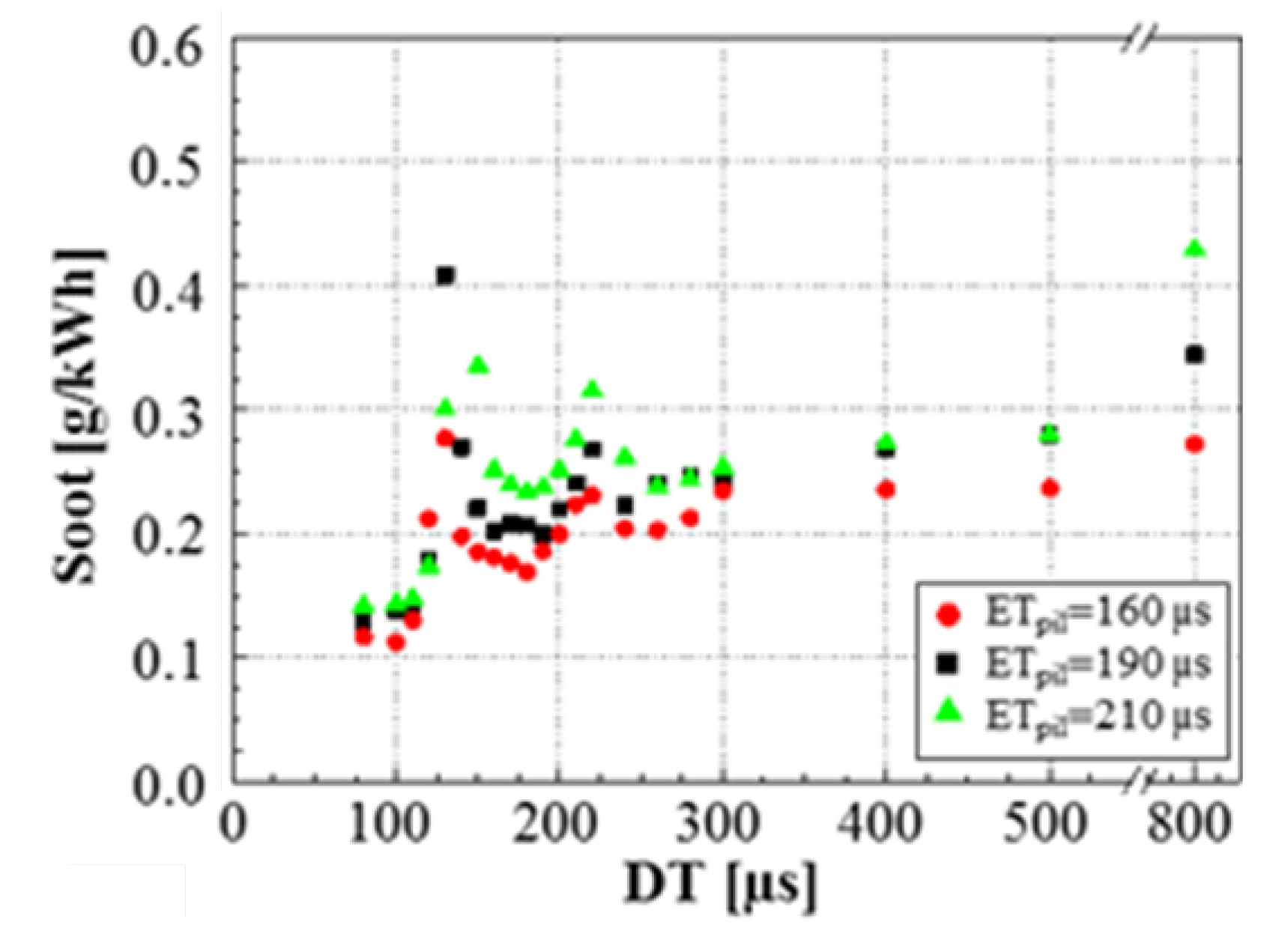

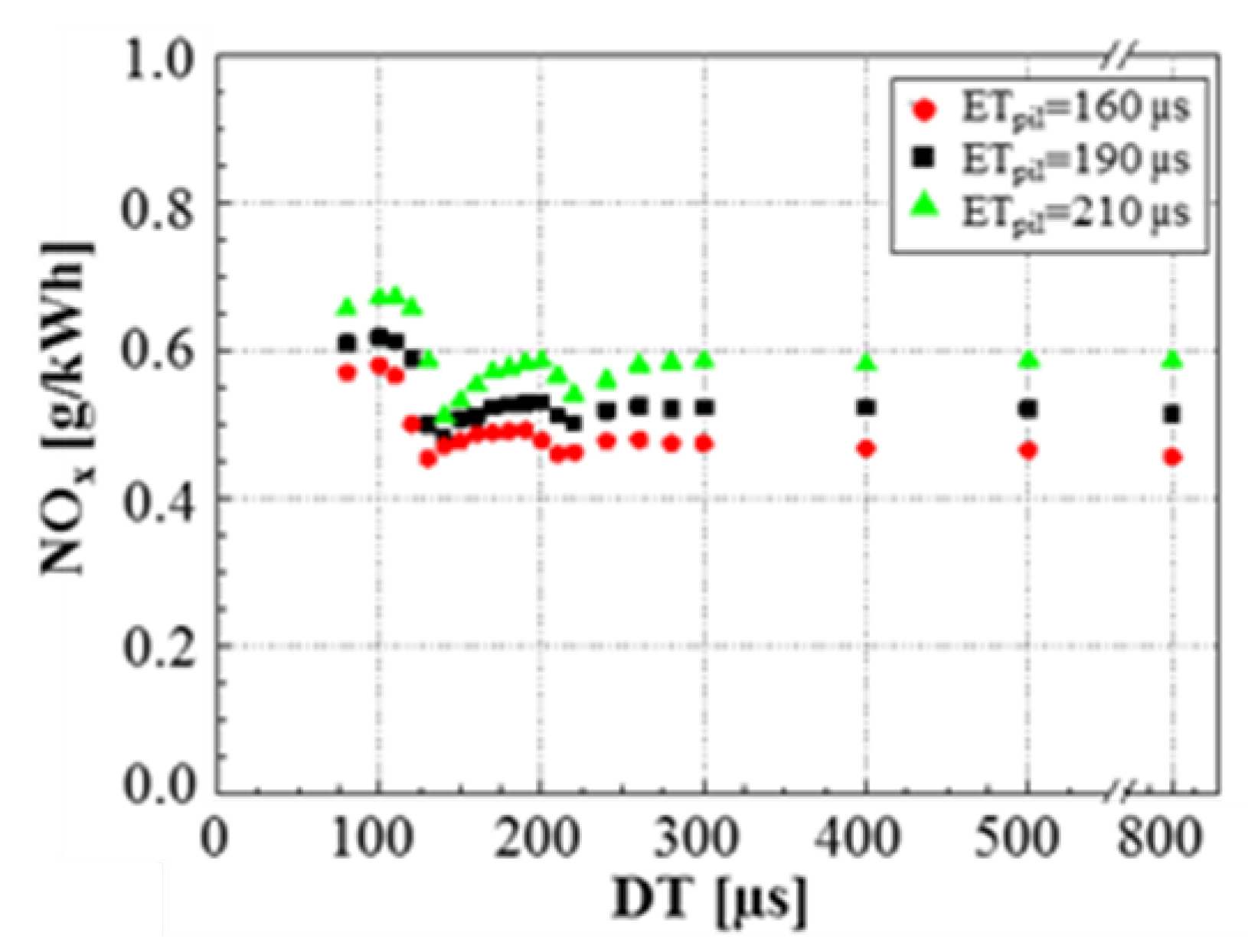

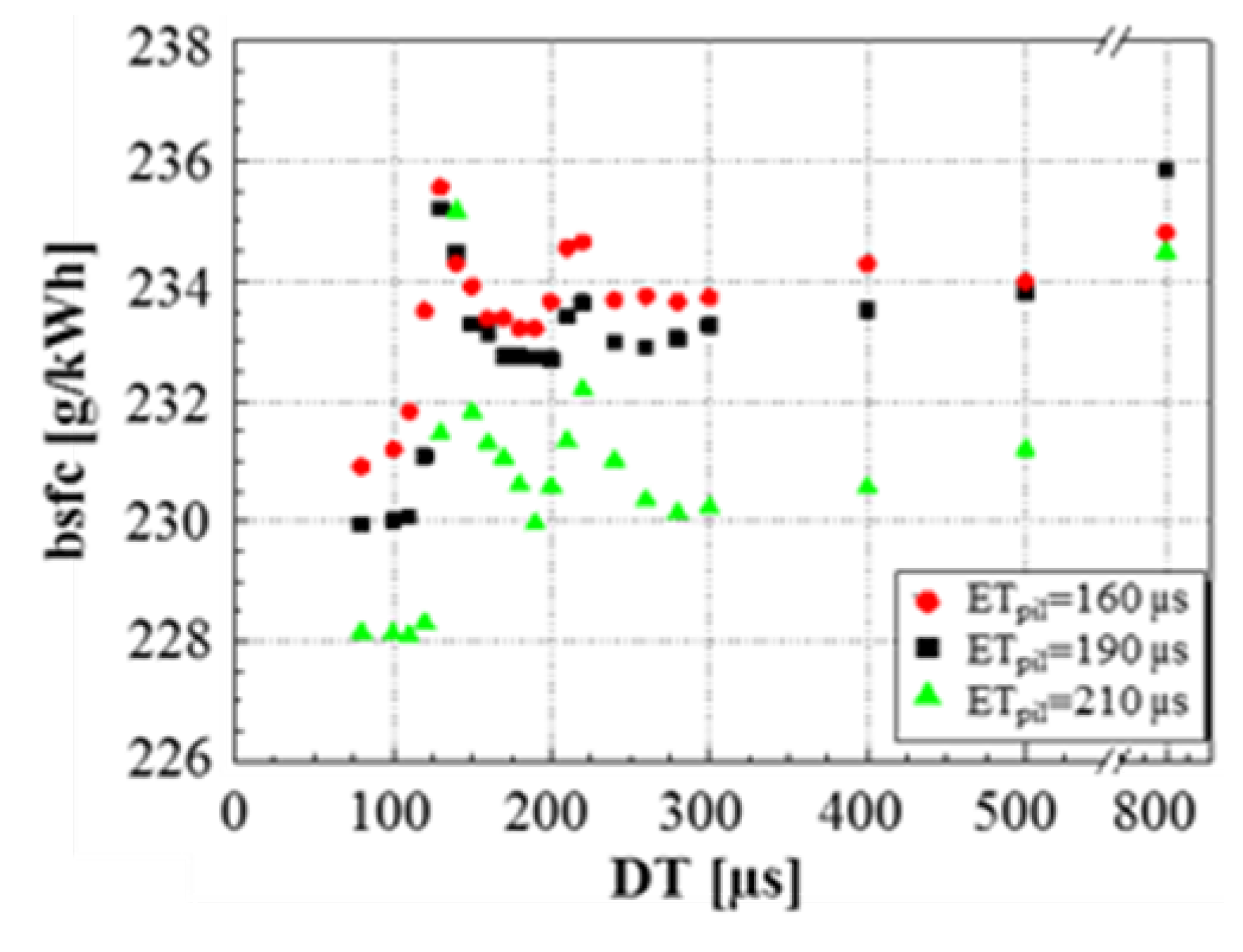

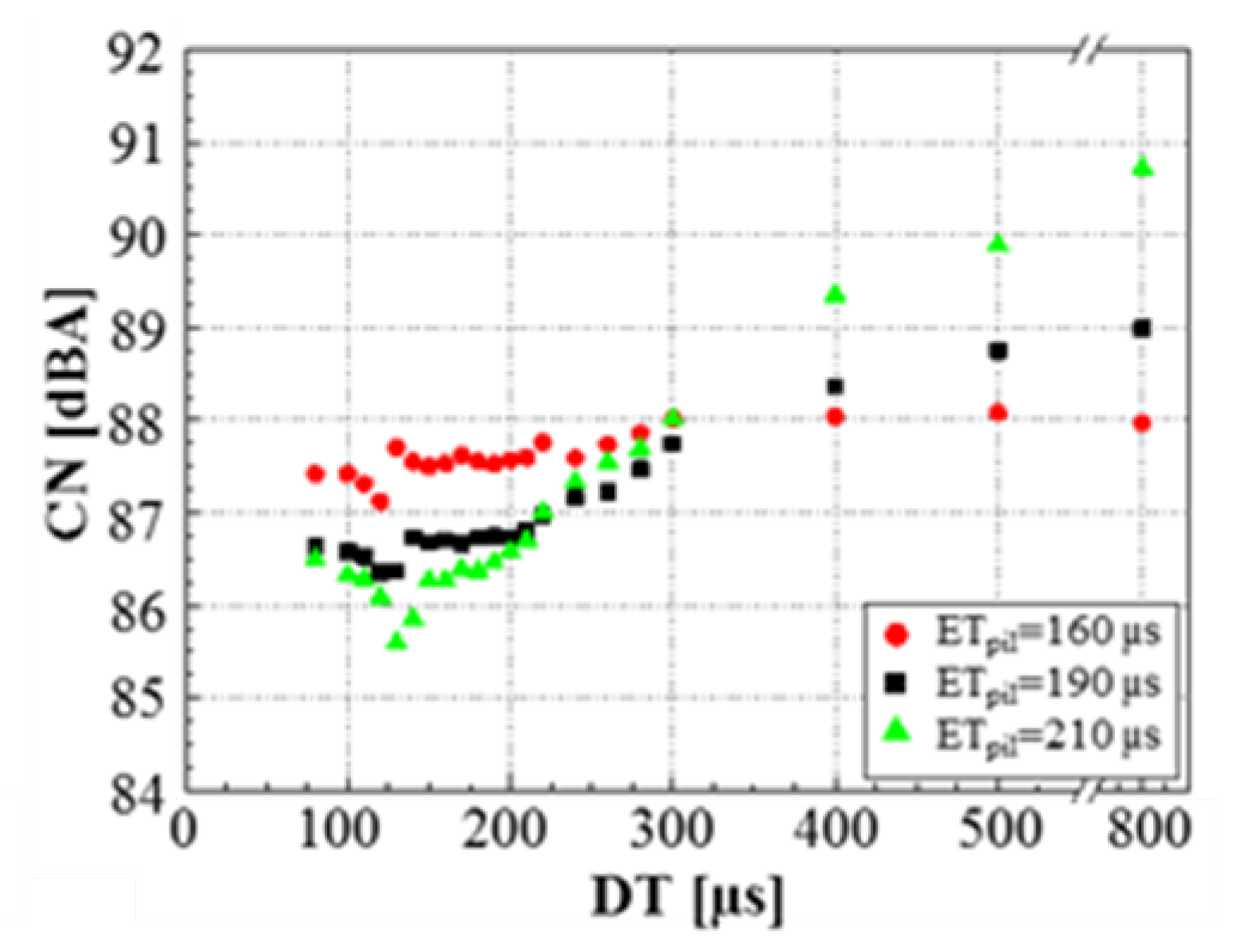

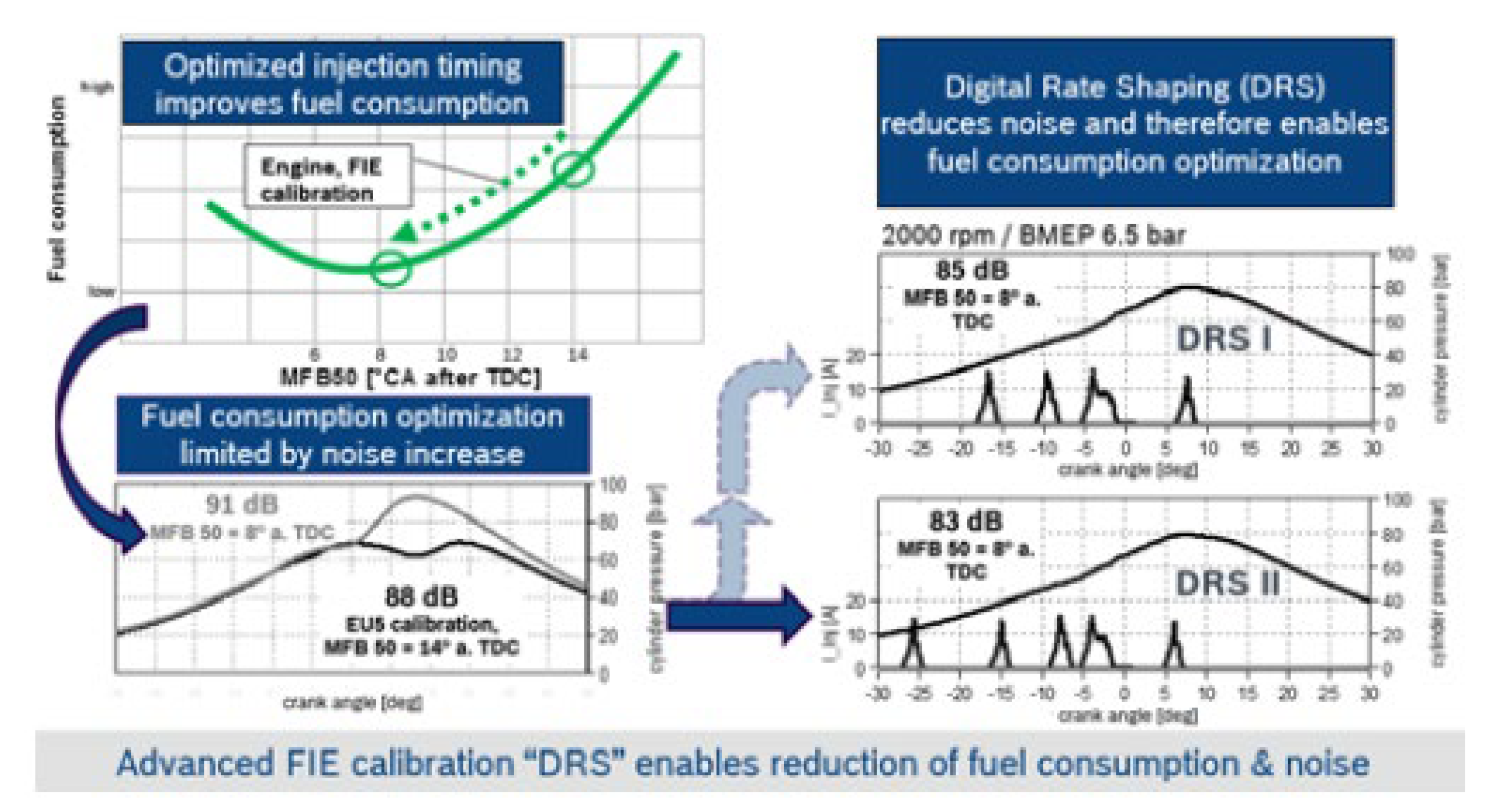

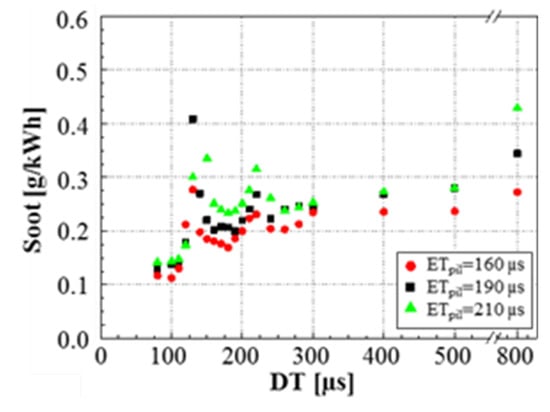

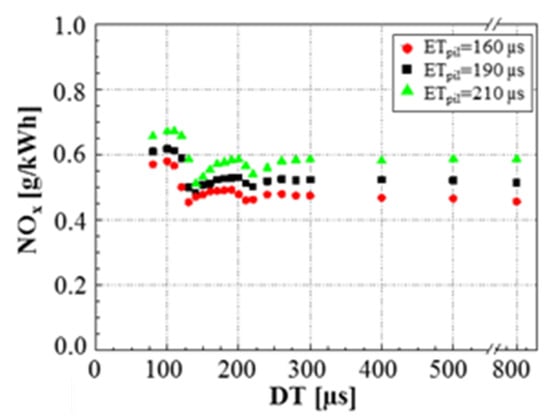

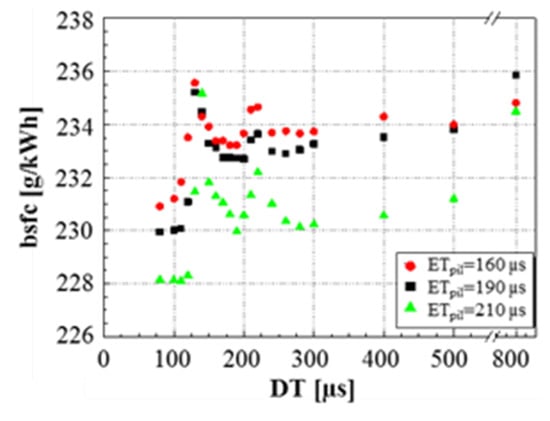

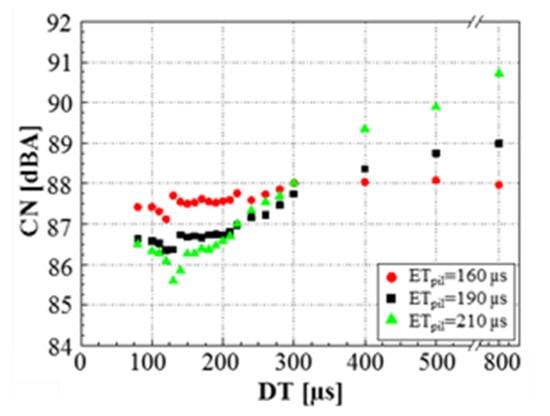

Soot emissions generally increase as the dwell time (DT) between pilot and main injections is reduced according to the classic theory. When the pilot injection is in an early phase, the ignition delay of the pilot spray is long and the heat release rate exhibits two-stage ignition with lower peaks. This indicates that the earlier pilot injection provides a leaner mixture in the pilot spray and burns mainly in a premixed mode with lower soot production. When the main spray entrains such a leaner gas, it would escape from rich combustion and would provide lower soot emissions compared with the later pilot injection case [65]. However, in [66], soot emissions increase as DT grows for different ETpil values at n = 2000 and BMEP = 5 bar, although soot emissions continue to increase with the value of ETpil according to the classic theory. As a consequence, due to the presence of the soot–NOx trade-off, the NOx emissions tend to reduce slightly with increasing dwell time between the pilot and main shots. A possible explanation for the presence of peaks or apparently anomalous trends in the soot emission distributions with respect to dwell time can be related to the swirl motion. In contrast to heavy-duty engines with relatively quiescent conditions, the swirl can govern fuel–air mixing to a greater extent in light-duty engines. The burned gas spots, which originate from pilot combustion, rotate due to the swirl motion, and the fuel plumes, which are injected through the injection holes during the main injection, can impinge on them. When the swirl ratio is fixed, a change in DT modifies the corresponding rotational angle of the pilot combustion-burned gases that drift by via the swirl, and such partial products of combustion can directly interact with the main injection fuel spray, thus producing a peak in the soot emissions. The main cause of a peak or of an anomalous trend in the soot emissions with respect to DT can therefore also be ascribed to the interaction between the burned gas clouds pertaining to the pilot combustion and the main injection fuel plumes. In fact, an oscillating pattern of the soot emissions, with respect to the swirl actuator position, can be observed in these conditions, whereas the soot should decrease monotonically as the value of the swirl ratio increases because turbulence improves the air–fuel mixing. The oscillations are ascribed to the variable interaction between the burned gas clouds pertaining to the pilot combustion and the main injection fuel plumes as Sw is varied.

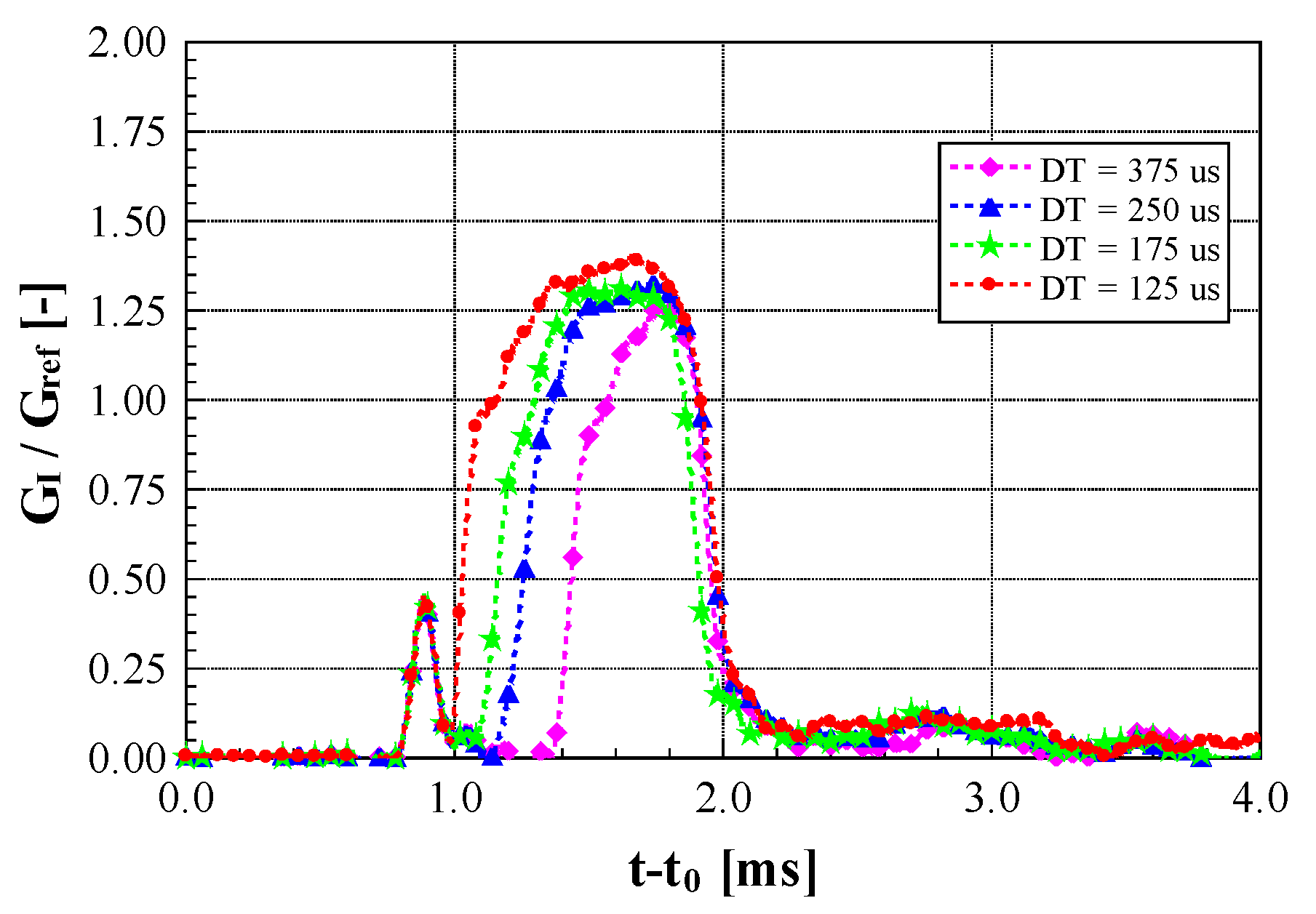

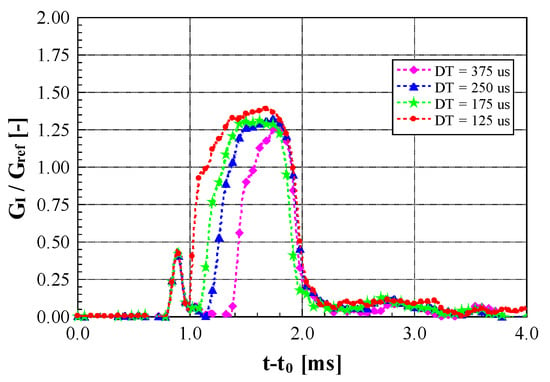

When the dwell time is very short, that is, DT ≤ 400 μs, the pilot injection is closely coupled to the main injection [67]. The fuel of the main shot is injected slightly before the burning of the pilot injection, and as a result, a lower rise in the temperature of the in-cylinder charge can occur due to main injected fuel evaporation, and the ignition delay of the main injection tends to increase compared to the case of a more conventional DT. Furthermore, a small pilot injection, closely coupled to the main injection, can cause an increase in the velocity of the injector needle during the nozzle opening phase of the main injection. In fact, the refilling phase of the pilot valve control chamber after the end of the pilot injection is not finished when the main injection starts: this reduces the nozzle opening delay significantly and accelerates the needle lifting up. As a result, the injected flow rate steepens in Figure 18 during the nozzle opening phase of the main injection as DT is reduced. This can improve the fuel atomization significantly during the first part of the main injection [68] and outlines a potential means for soot emission reduction. Furthermore, the increase in the flow rate at the beginning of the main injection due to the higher instantaneous values of the needle seat passage restricted flow area allows the rail pressure level to be reduced in order to maintain the same injected mass, and this strategy can also be used to counteract combustion noise, which becomes worse as the rail pressure level increases [69]. In [70], it is stated that a pilot injection, which is closely coupled to the main injection, minimizes smoke. On the other hand, the possible interference between the pilot combustion event and the main injection, which is more likely to occur for short DT values, can mask the benefits of both the increased ignition delay and the higher velocity of the needle at the beginning of the main injection and can lead to an augmentation in the soot emissions. Therefore, the potential of a pilot shot closely coupled to the main injection is relevant, but the dwell time must be accurately optimized.

Figure 18.

Injected flow rate for a pilot–main injection with DT ≤ 400 µs [30].

As far as the HC and CO engine-out emissions are concerned, at low BMEP values, they generally decrease if a pilot injection is implemented because the occurrence of overmixing during the main injection is less likely [62]. In particular, the CO conversion rate improves during the main combustion because of the relatively high in-cylinder temperature and the shorter ignition delay of the fuel injected in the main injection [54]. Instead, at medium BMEP values, the introduction of the pilot injection does not generally improve the HC and CO emissions, compared to the single-injection case, and this is confirmed in many investigations [71]. HC and CO emission characteristics show quite similar tendencies with respect to SOIpil and pilot mass: the levels of both emissions generally increase with earlier SOIpil or when the pilot mass increases excessively. These phenomena can be explained based on two mechanisms. The first is that the amount of fuel wetted on the cylinder wall, crevice and boundary layers can increase because fuel over-penetration occurs, due to low ambient temperature and pressure conditions during early pilot injection (SOIpil up to around 40 CA bTDC); this wetted fuel is then emitted in the form of HC emissions. Moreover, injecting more fuel during pilot injection generally results in more fuel wall wetting. In particular, HC and CO emissions drastically increase with an SOIpil earlier than 30° BTDC and a pilot injection quantity greater than 5 mg (this cannot be the case at low loads). In [72], the fuel spray injected at 40° BTDC reaches the cylinder wall: this results in combustion in the quench zone and adhesion of part of the fuel on the cylinder walls, causing an increase in HC and CO emissions. Even though the fuel does not impinge on the walls, the mixture can reach the vicinity of the chamber wall and, due to the relatively lower in-cylinder temperature and pressure near the chamber walls, this fuel–air mixture may not burn, resulting in increased HC and CO emissions. The second mechanism is based on the fact that higher HC emissions may originate from locally lean regions becoming even leaner and thus too cold for complete reactions [73]. While the first mechanism gives increased HC and CO emissions as either DT (let us suppose that SOImain is fixed) or ETpil grows, the second mechanism makes HC and CO emissions rise with either increasing DT or reducing ETpil since the occurrences of overmixing are more likely if the pilot injected mass diminishes or DT grows. Therefore, when CO and HC emissions grow with increasing ETpil, the first mechanism prevails over the second; instead, when CO and HC emissions augment with reducing ETpil [66], the opposite occurs.

Finally, the indicated specific fuel consumption (isfc), which refers to the indicated mean effective pressure without pumping losses included, generally worsens at medium loads and speeds when a pilot injection is added to the main shot, although the variation is not remarkable: the penalty is ascribed primarily to larger heat losses, due to earlier combustion phasing, to larger blow-by masses (higher in-cylinder pressures occur for a larger time interval), to lower values of the polytropic exponent through the whole expansion phase and also to the increase in compression work. However, as DT is reduced, the pilot and main combustions are more concentrated and linked smoothly, and this can even have the potential to enhance combustion efficiency [74], thus mitigating the isfc penalty. Fuel consumption worsens at early SOIpil, that is, where HC emissions also increase because these emissions have a strong relationship with combustion efficiency.

In general, the pilot injection can be exploited in different ways to improve engine-out emissions, CN and fuel consumption, depending on the working point [75]. Soot emissions are not relevant at low engine speeds and loads, and NOx and noise are usually controlled, at these conditions, by means of adequate EGR rates (up to 40% for conventional combustion). Hence, the pilot injection is typically optimized, on the basis of the EGR rate, in order to reduce HC and CO emissions, which tend to be high, due to the presence of lean and cool regions. In particular, the HC and CO emission situation becomes worse at engine cold-start and warm-up, when the oxidation catalyst has less conversion efficiency. Soot, NOx, noise and bsfc are the dominant problems at medium-load conditions, i.e., in the higher-load zone of the NEDC region, whereas HC and CO are not of great concern. Pilot injections are therefore used in these conditions to improve PM-NOx and bsfc-NOx trade-offs and, above all, CN performance. At high loads, the total fuel mass per cycle is large. Although pilot injected fuel could improve the fuel–air mixture environment, the combustion is predominantly diffusive; the pilot fuel is relatively small, compared to the main injected fuel mass; and hence, it does not appreciably change the main combustion features. Therefore, at high loads, pilot injection cannot generally be applied to reduce the emissions significantly. Only when pilot–main injection intervals and pilot injected masses are large (an early big pilot is used) can appreciable smoke reduction be achieved because the main injection is shortened, although there is a penalty on CO emissions (there is no significant impact on NOx and bsfc) [76]. In particular, when the maximum torque is smoke-limited, an early big pilot injection can increase the full load torque by improving the utilization of the air within the cylinder, compared to the case of a single injection with a longer energizing time and in the presence of EGR [77]. In this case, pilot injection also improves combustion efficiency. Moreover, pilot injection can be used at full load to limit the peak in-cylinder pressure and the engine exhaust temperature. The pilot injection therefore allows for either the fuel rate to be increased or the mechanical and thermal stresses in the engine to be reduced, thus providing possible weight savings or simplifications of the cooling circuit. Although pilot injection has generally been applied to improve pollutant emissions, noise or maximum torque, it can also be used for other purposes and offers other benefits. An early pilot injection can be applied to increase the in-cylinder pressure at the end of the compression stroke during engine cranking, thus reducing the engine start time. Furthermore, pilot–main injection patterns reduce the cycle-to-cycle variability of the torque, compared to single injections [54], and this induces more stable engine operations after the engine crank phase, especially during a cold-start. It can also improve combustion noise during engine start [70], but, at these engine working conditions, other sources of noise (gas flow and mechanical noises) dominate in the vehicle.

2.3.2. Main-After Injection Mode

The amount of soot in the combustion chamber typically increases until around the end of fuel injection or shortly after it, at which time the main soot formation period concludes and the “burnout” phase begins [78]. The vast majority (more than 90%) of the soot formed is oxidized before combustion has ended, but a small fraction coming from the main combustion is not consumed and is the source of tailpipe soot emissions.

After injections are characterized by a very short ignition delay and primarily aimed at reducing the soot emissions. Unlike pilot injections, which do have major impacts on the main injection combustion process, after injections seldom have an impact on pilot injections and on the first part of main injection combustion processes. In this sense, after injections are almost “independent” of pilot and main injections. In particular, applying pilot injections or not will not markedly affect after injection’s effects on emissions [76].

There are two ways of quantifying the effectiveness of an after injection in reducing engine-out soot: comparison to a single injection at the same load, but with the main injection duration of the main–after strategy shorter than the single-injection duration, or comparison with a single injection of the same duration as the main injection of the main-after strategy, but at a lower load. The constant-load perspective is relevant for practical engine operations, where it is desirable to achieve a particular load point, whereas the constant main injection perspective is relevant for some fundamental fluid–mechanics considerations because a constant in-cylinder environment is maintained at the start of the after injection (e.g., penetration and diffusion of the main injection jet are almost the same). Both perspectives are considered in what follows.

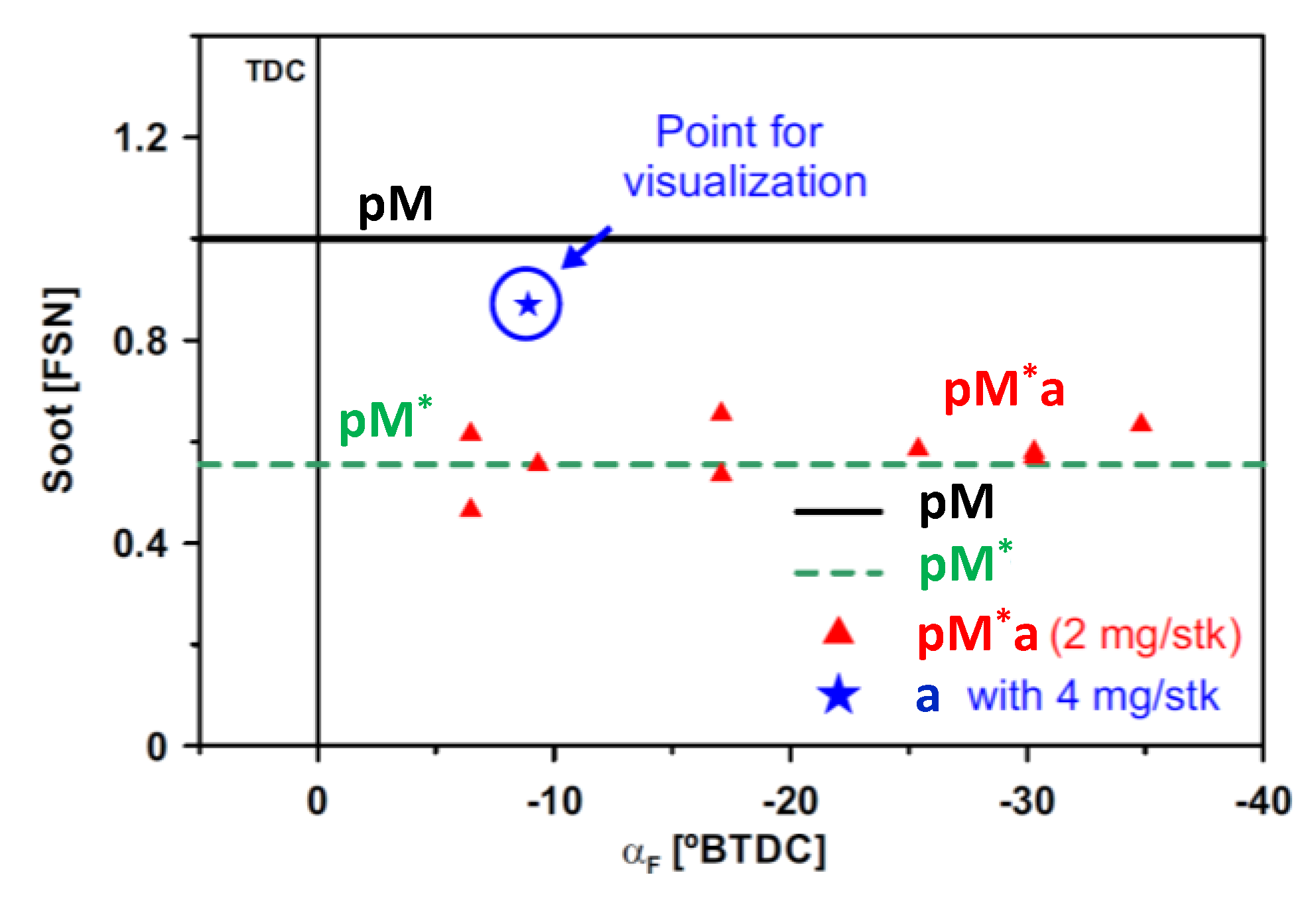

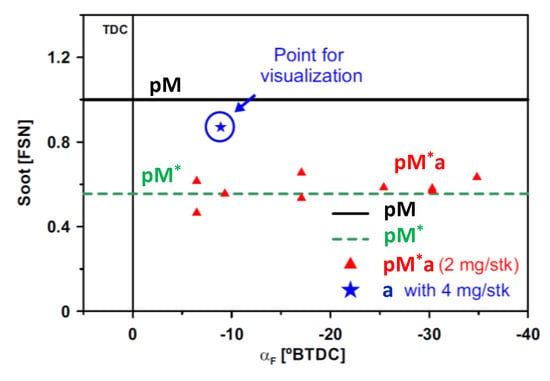

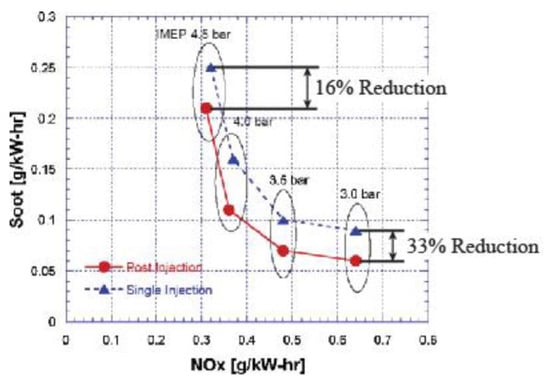

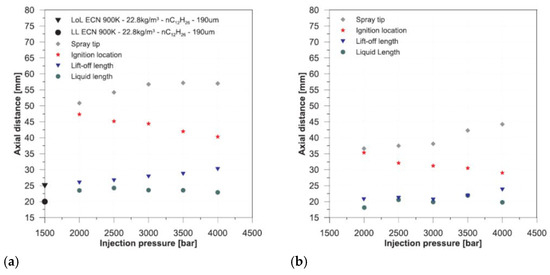

Unlike the pilot injection, the after injection mechanism is not fully understood. Two primary theories can be developed for explaining the effect of the after injection on soot emissions: one is founded on the absence of any interaction between the main and after combustions (this theory generally works for more quiescent combustion chambers), while the other involves the interaction between the two combustion events (this theory generally works for combustion systems with higher turbulence degree). On a broader spectrum, when an interaction between main and after combustions occurs, it can be positive, leading to reduced soot emissions, or negative, giving rise to increased soot emissions, compared to the case without after injections. Figure 19 [79] reports the soot engine-out emissions as a function of the after injection timing: the acronym pM refers to a pilot–main injection, the acronym pM*a to a pilot–main–after injection with the same injected mass as that of the pM (constant-load perspective), and the acronym pM* to a pilot–main injected mass with the same pilot and main energizing times as those of the pM*a strategy. The shortening of the main injection and the introduction of the after shot significantly improve the situation (cf. pM versus pM*a). However, the graph shows that, for any injection timing of a 2 mg after injection, the soot emission levels are the same and also equal to the pM* case, which refers to the absence of the after injection. This means that the effect of the after injection is always neutral: the soot emission levels are the same with or without an after shot, independently of the after injection timing. This explanation is based on the “split-flame” concept: the fuel from the main and after injections burn separately without any interaction, and the reduction in soot stems from splitting the fuel main delivery into two injections to avoid excessively long main injection events.

Figure 19.

Soot emissions as a function of SOIafter [79].

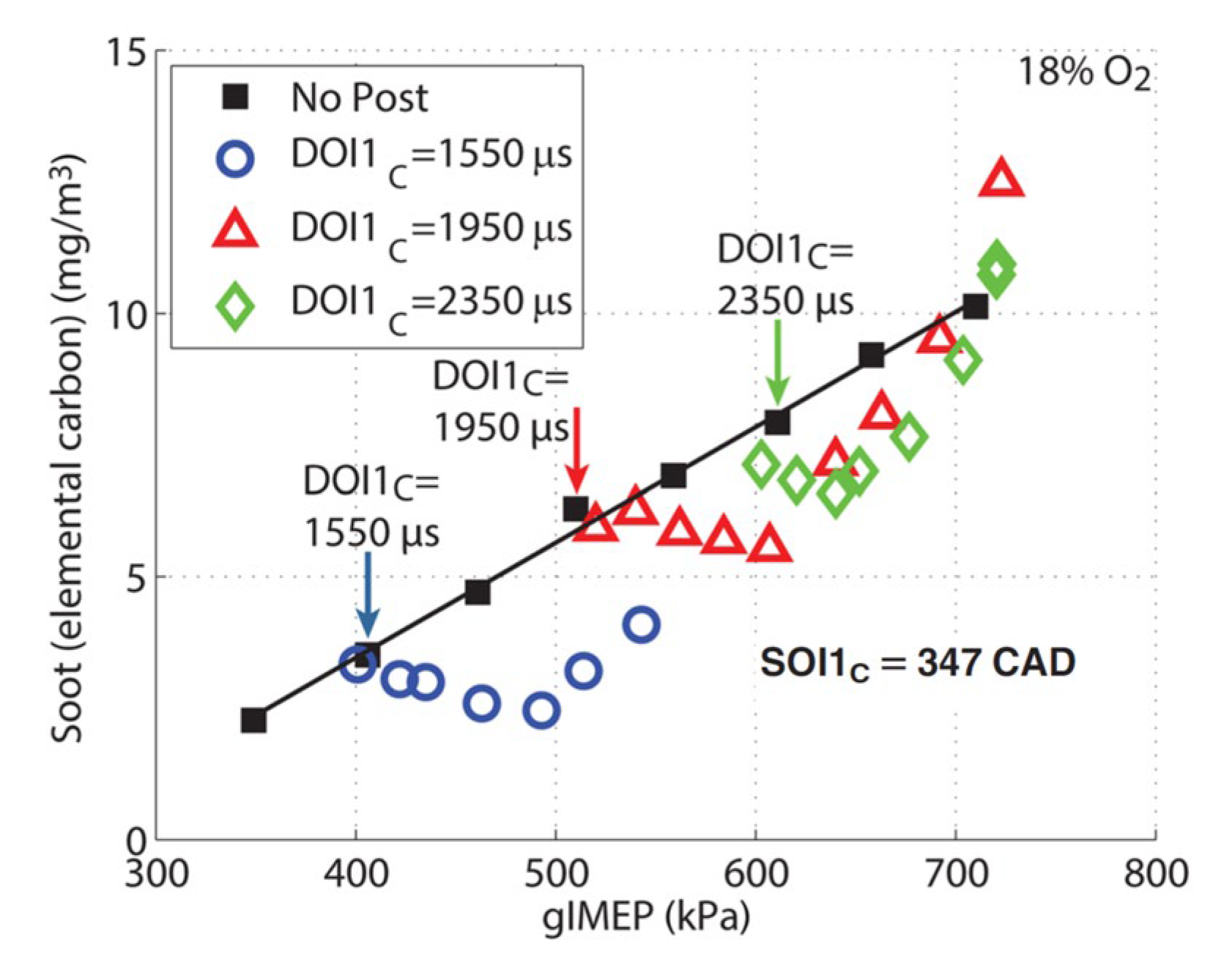

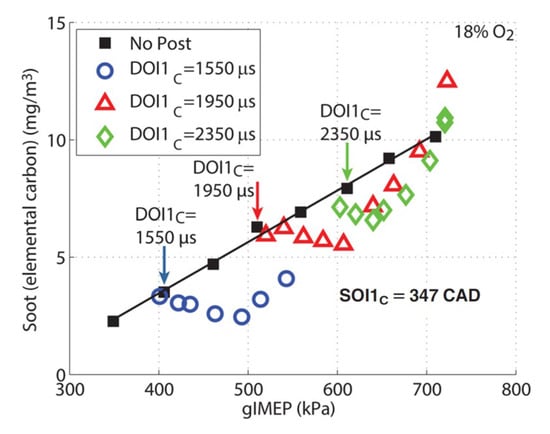

Figure 20 [80] shows the engine-out soot emission for a main shot and a closely coupled after injection (open symbols) as compared to the baseline single injection (filled squares). For each fixed main injection duration (DOI1c), the after injection trend with increasing duration of the command (DOI2C), which produces an increase in load (constant main injection perspective), is similar: the engine-out soot initially slightly decreases or remains similar and then increases dramatically as DOI2C increases beyond a threshold value. The point of abrupt change in the soot emissions coincides with the end of the split-flame regime. There is generally a threshold on the after injected mass, beyond which the split-flame behavior is no longer valid. The more intense the turbulence within the cylinder, the smaller the after injected mass threshold.

Figure 20.

Soot emissions as a function of ETmain and ETafter [80].

The other popular theory which explains the effect of the after injection on soot emissions by means of the interaction between the main and after combustion events is generally based on two mechanisms: enhanced mixing and temperature effect. Several studies have presented the explanation that after injections reduce engine-out soot by enhancing mixing within the cylinder [81]. Turbulence introduced by the after injection fuel jet brings fresh oxygen to the soot from the main injection, enhancing oxidation of this soot, while simultaneously burning the after injected fuel: the after injection redistributes the fuel from the main injection, creating a more well-mixed fuel–air distribution with smaller and less fuel-rich soot-forming zones [82]. In other words, the enhanced mixing by the after injection increases the flame area, thereby increasing the rate at which soot is oxidized. If enhanced mixing is the key, spray/swirl/wall interactions and swirl/squish interactions become important: this is the case of small-bowl light-duty engines, especially in past setups [55]. The disparity in after injection efficacy among studies on interactions between main and after shots may be explained to some degree by differences in spray/flow/wall interactions [52]. Other studies have argued that as the after injection fuel burns, the increased temperature from the additional heat release can enhance the oxidation of soot from the main injection, thereby reducing engine-out soot [9,81,83,84].

There is also a third theory, related to a low intensity interaction, for explaining the after injection effect on soot emissions [85]: it is based on the injection duration effect [86,87] and on the concept of “jet replenishment” and is especially useful in quiescent combustion systems, such those of heavy-duty engines and, more recently, in passenger car engines (the theory based on the jet replenishment can be considered in the middle between those of “split-flame” and “interaction”) [55]. While in the past (up to around 2016), high swirl ratios in the 1.5–2.0 range were applied in passenger cars, the recent tendency is to use swirl ratios around 0.5 in order to maximize the engine volumetric efficiency and reduce thermal exchanges with the walls; therefore, soot is today counteracted more with high injection pressure than with large swirls. Hence, modern passenger cars are often characterized by low turbulence intensity and both the split-flame and the jet replenishment can therefore be useful theories to interpret the results.

While each of the previous mechanisms, namely split-flame, enhanced mixing, temperature effect and jet replenishment, are certainly plausible, insufficient evidence exists to quantify the relative importance among the different mechanisms for the different operating conditions [52]. Enhanced the mixing redistribution mechanism is particularly important when oxygen is limited, that is, at medium to high loads and under high rates of exhaust gas recirculation [82]. Instead, the split-flame mechanism is the most referenced in studies with closely coupled after injections, where hydraulic dwell time between main and after injections is short and in the presence of small after injected masses (cf. Figure 19) because there is no influence of the wall-reflected combustion pertaining to the main injection on the after injection and spray. However, the results in [70] show that the reduction in soot from the closely coupled after injection is attributed to both enhanced mixing and increased temperature. This proves that the split-flame regime is not automatically reached for closely coupled after injections characterized by a small mass.

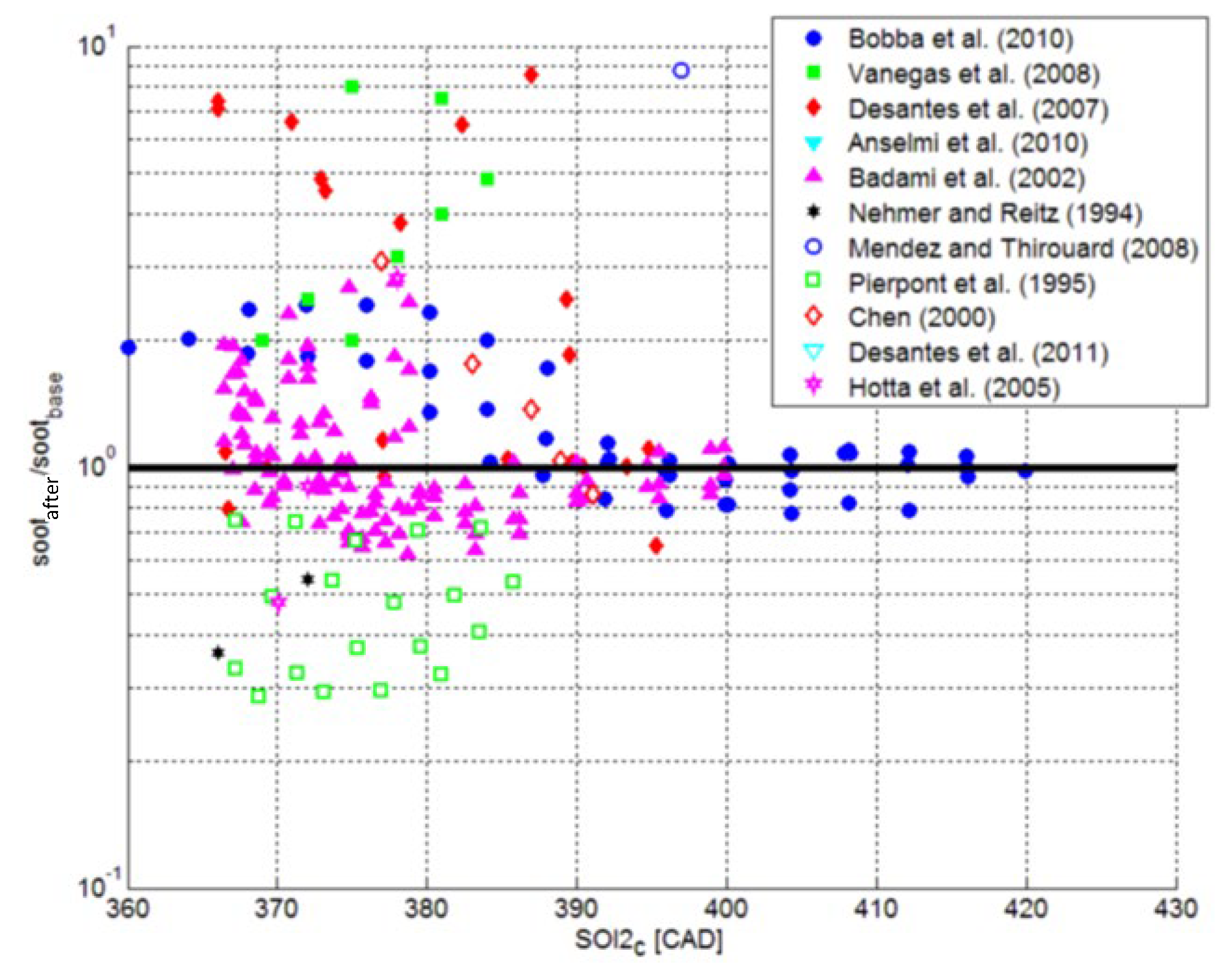

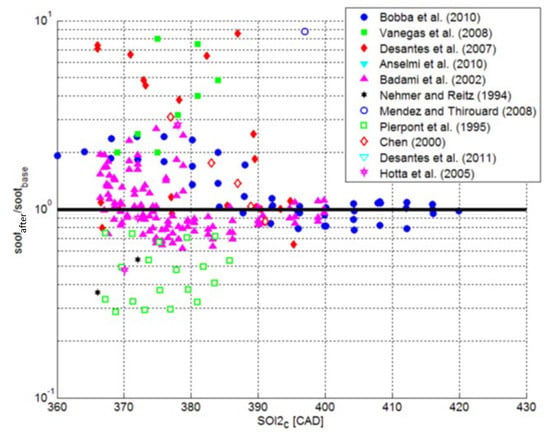

Before considering the question of the premium theory and mechanism for explaining the soot reduction by means of the after injection, it should be considered that the degree to which after injections reduce or even increase soot can vary by nearly an order of magnitude in each direction in the results presented in the literature [52]. The inconsistency in engine-out soot results is evident in Figure 21, which shows a compilation of data from different after injection studies. Here, the ratio of engine-out soot with an after injection to that without an after injection is plotted against the start of the after injection according to a constant-load perspective. Operating conditions such as main injection duration and timing, after injection duration, load, speed, boost and EGR are not held constant across these studies. The distribution of data above and below unity in Figure 21 indicates that after injection efficacy is not universal, but rather highly sensitive to the engine technology and the operating condition. It is important to note that many studies quoted in Figure 21 changed several of these parameters simultaneously, and therefore, the effect of each of these engine operational parameters on after injection efficacy may not be separable.

Figure 21.

Ratio of the soot engine-out emissions with an after shot to those without an after shot as a function of SOIafter [52].

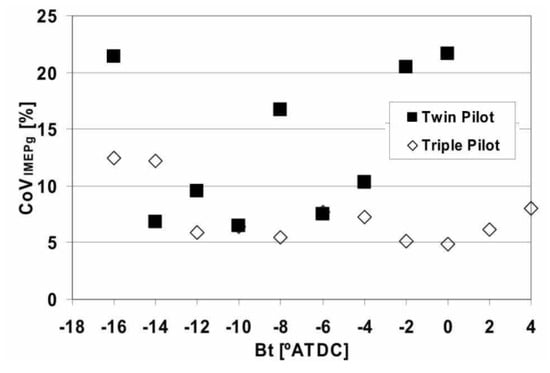

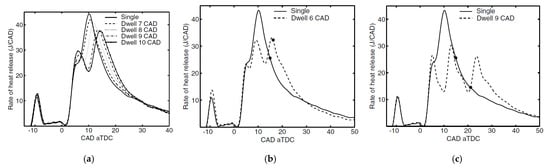

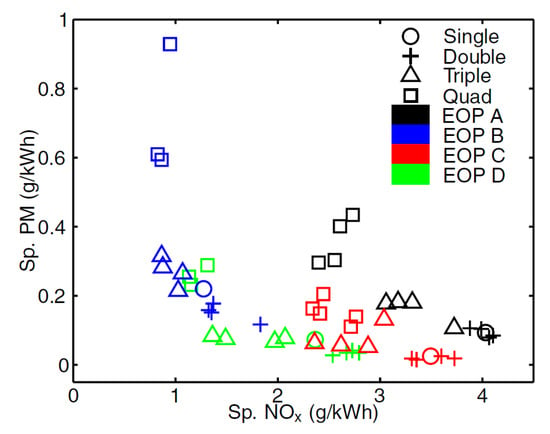

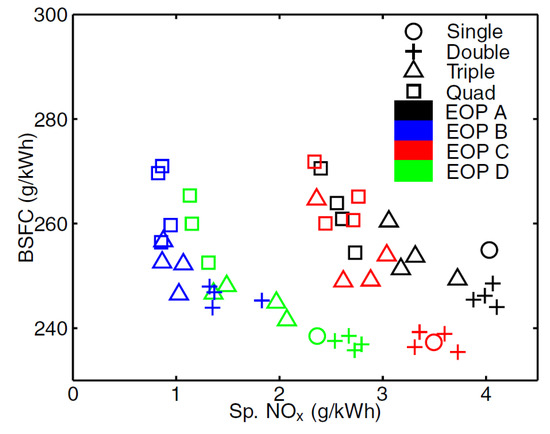

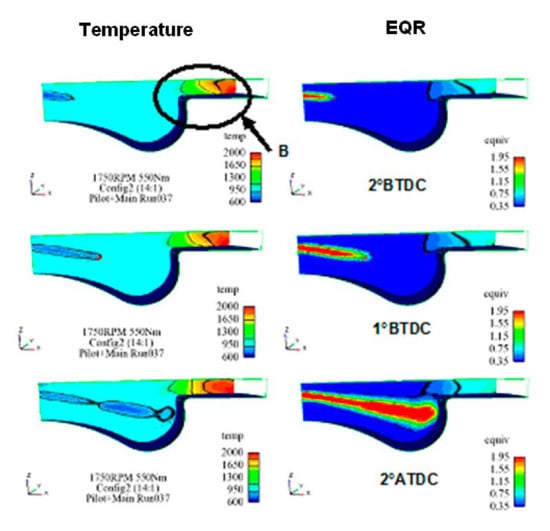

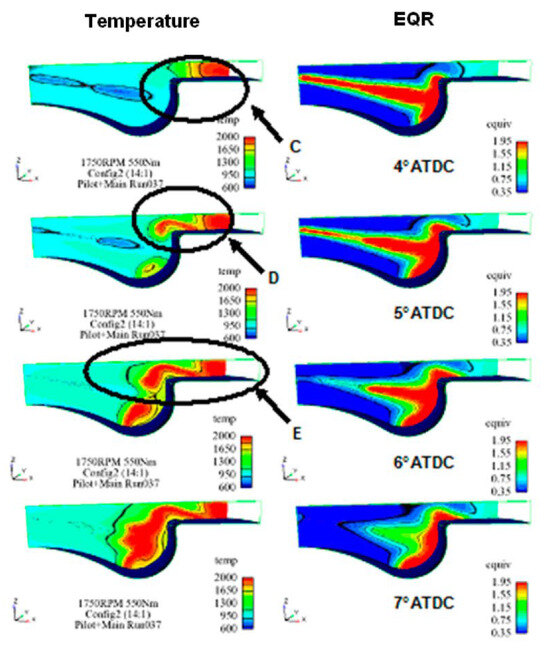

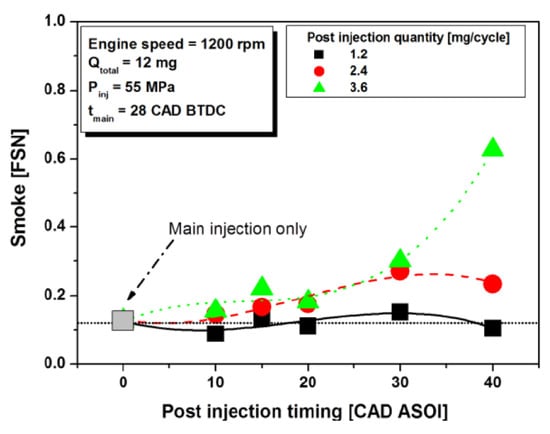

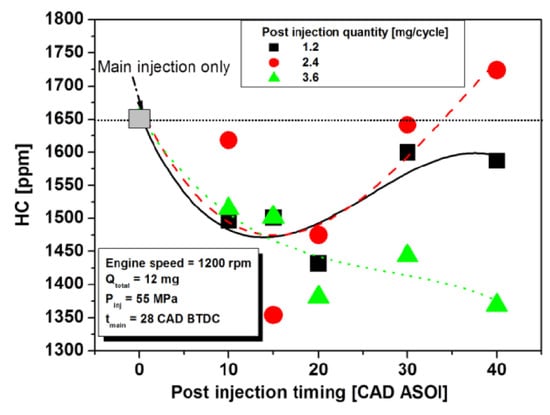

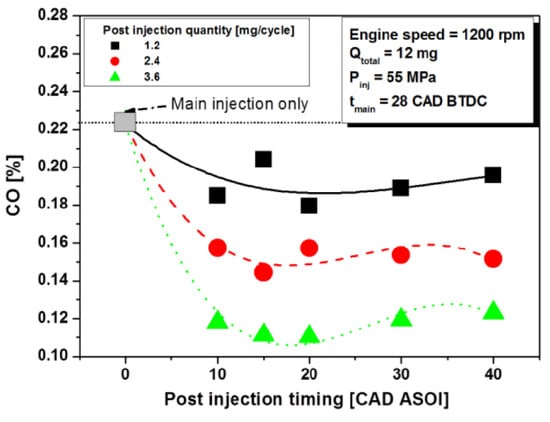

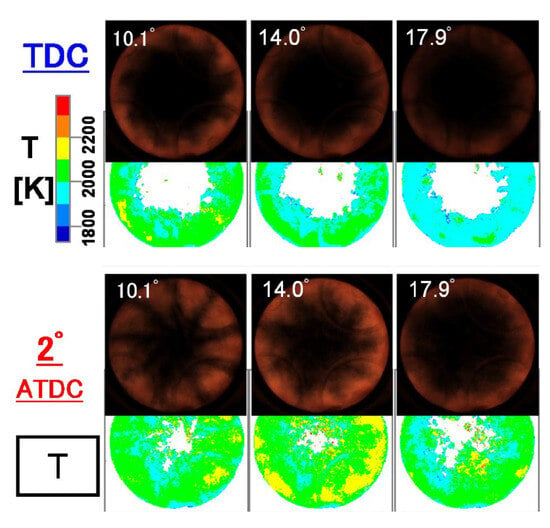

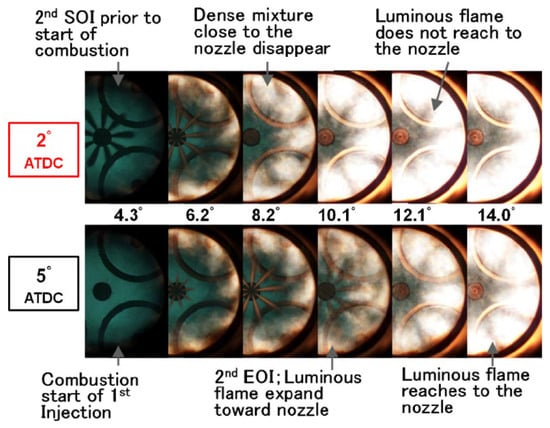

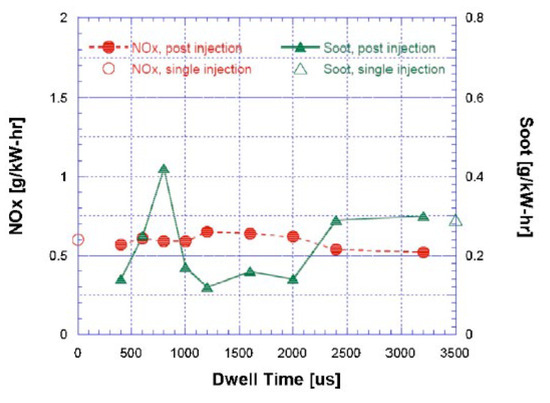

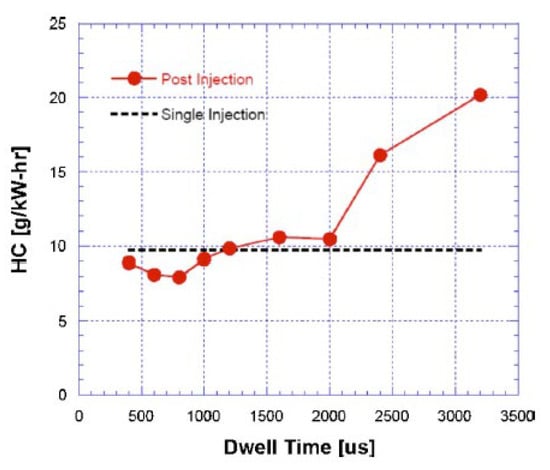

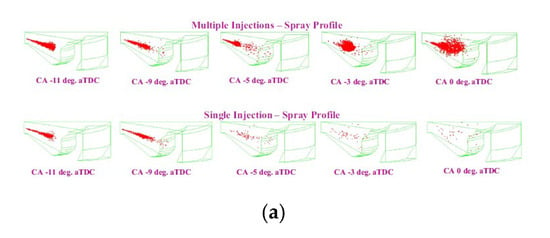

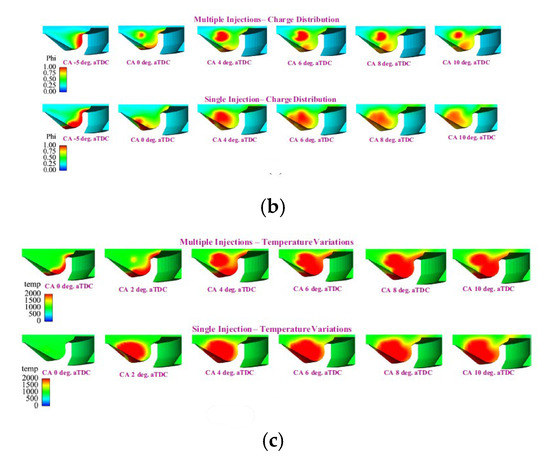

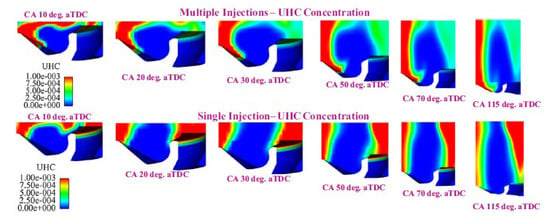

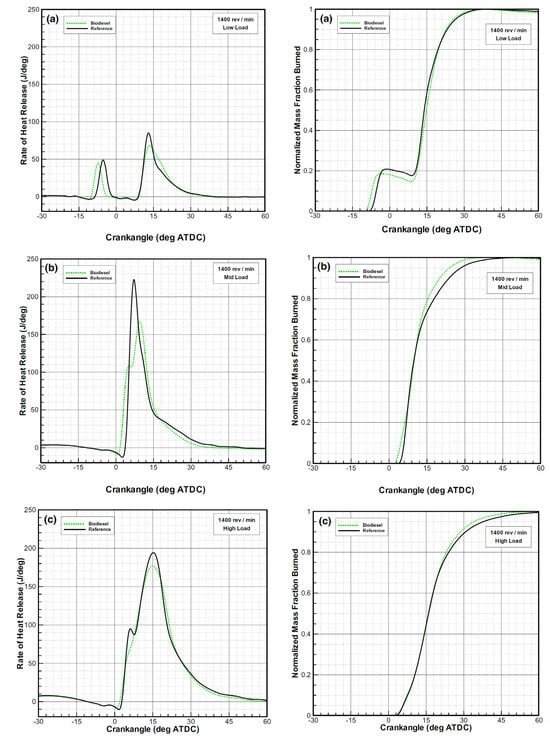

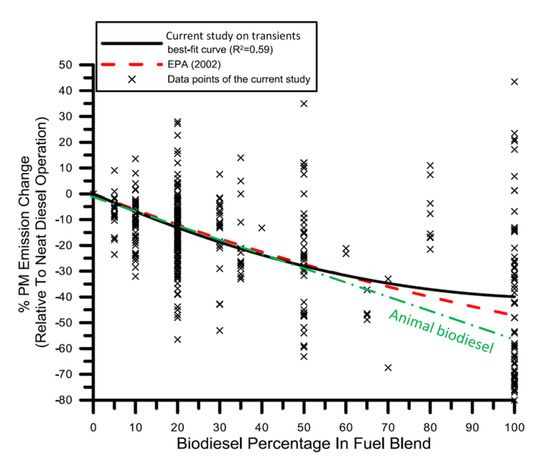

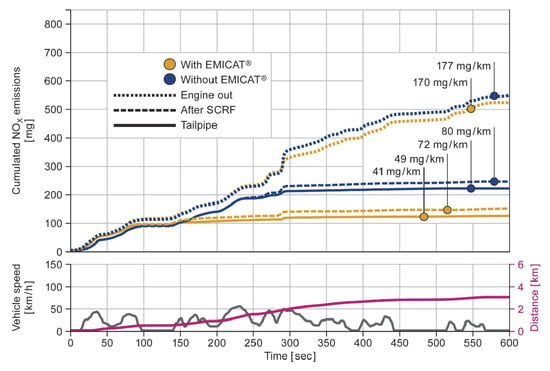

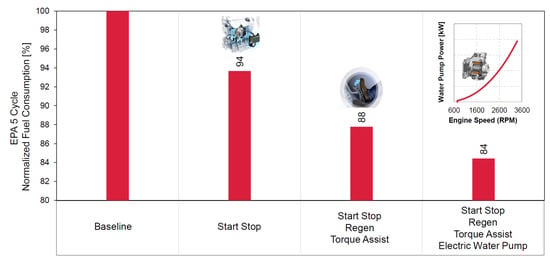

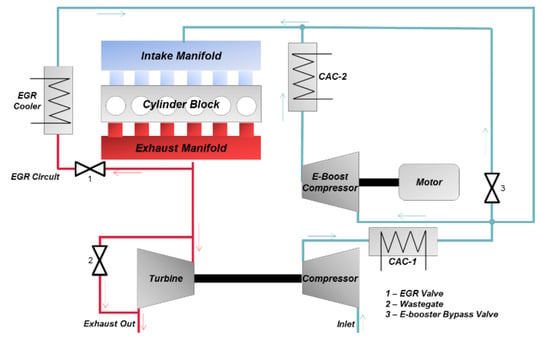

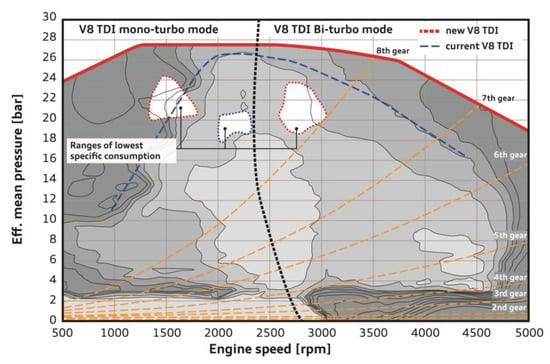

Although there is no after injection dwell time and duration combination that clearly and universally leads to soot reduction [9,83,85,86,87,88], researchers have often reported that a “sweet spot” can be reached, where engine-out soot is minimized [81,86,89]. In particular, two possible scenarios in which an after injection seems to be an efficient strategy to reduce soot emissions have been identified: one is when the after injection is very close to the main injection and the other is when it is much delayed with respect to the main injection, at least 20 CA from the end of the main injection. On the whole, studies have shown that shorter-dwell injection schedules can reduce engine-out soot more than longer-dwell schedules do. Furthermore, the soluble organic fraction (SOF) of the particulate matter increases monotonically as the after injection timing is delayed, which is ascribed to deteriorated in-cylinder thermodynamic conditions at large crank angle intervals [89]. When a closely coupled after injection increases global soot emissions, as in some cases in Figure 21, this can be ascribed to a negative interference between after and main injections [90]. Typically, if the dwell time is too short, the after fuel is injected into regions where the combustion of the main fuel takes place: the atomized fuel spray lacks oxygen because the after injection entrains the burned gases. As a result, combustion progresses gradually, causing a low heat release peak, and the slow combustion rate during the diffusion combustion makes the smoke emissions increase. In these cases, the after injection produces additional soot rather than oxidizing the soot formed as a result of the main injection. It has been claimed [91] that if DTafter is less than 400 μs, the amount of soot can be higher than in the case of the absence of an after injection because of the strong cooling effect of the vaporization heat of the after injected fuel on the oxidation of the main combustion products.