Abstract

The transition to electric vehicles (EVs) plays a pivotal role in achieving decarbonization within the transportation sector. However, the widespread adoption of EVs faces multifaceted challenges, particularly concerning infrastructure development. This paper investigates the intersection of sustainability, decarbonization, and EV adoption, with a focus on identifying and analyzing the challenges associated with infrastructure deployment. Strictly adhering to the methodological principles and process of systematic literature reviews, this paper analyzes research spanning the fields of engineering, energy, computer science, environmental science, social sciences, and others to elucidate the barriers hindering EV adoption, ranging from technological limitations to regulatory complexities and market dynamics. Furthermore, it examines the critical role of infrastructure, encompassing charging networks, grid integration, and supportive policies, in facilitating EV uptake and maximizing environmental benefits. The findings are finally used to present the implications for theory, practice, and policies and to highlight the avenues for future research.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Context

Sustainable development stands as a contemporary global challenge, requiring an intricate balance between economic growth, environmental preservation, and social well-being [1,2]. The demand from the population for sustainable business practices is increasingly significant as environmental and social considerations gain prominence in the corporate landscape [3]. Consequently, companies are swiftly adapting and integrating sustainable practices to align with these evolving priorities [4]. Ecosystem damage, a pervasive issue, significantly hinders progress across various domains. It exacerbates climate change and destabilizes both economic and social systems, thereby impeding the overall trajectory towards sustainable development [5]. One of the most pressing environmental concerns linked to ecosystem damage is the emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs). The effects of GHG emissions on the environment are profoundly impactful [6]. When GHGs, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2), accumulate in the atmosphere, this process involves trapping additional heat within the Earth’s atmosphere, leading to a gradual increase in global temperatures—a phenomenon known as global warming [7].

The pressing need for sustainable solutions to mitigate climate change has propelled the transportation sector into a pivotal role in global decarbonization efforts. According to World Bank [8], it is a significant contributor to GHG emissions, thereby playing a considerable role in climate change. The transportation sector is responsible for a quarter of global CO2 emissions and approximately 16% of total GHG emissions. World Bank projections indicate that if transportation networks continue to expand while relying on fossil fuels, emissions from this sector could surge by nearly 60% by 2050. Moreover, Gadonneix et al. projected that, by 2050, there would be a substantial increase in total fuel demand across all transport modes, ranging from 30% to 82% above 2010 levels [9]. Despite this growth, the transport sector’s fuel mix will continue to rely heavily on traditional fuels like gasoline, diesel, fuel oil, and jet fuel comprising 80% to 88% of the market. The demand for these major fuels is expected to rise significantly, with diesel and fuel oil seeing growth rates of 46% to 200% and jet fuel demand projected to increase by 200% to 300%. For this reason, scholars agree that the adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is a critical solution for sustainable development, particularly in terms of reducing GHG emissions and mitigating climate change [10,11,12]. In addition, as a response to this problem, in 2015, 197 parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) agreed on a new strategy for sustainability [13], and, after that, in the frame of this convention, a number of nations have started incorporating EVs into their transportation systems to lower emissions from this sector [14,15].

Indeed, among a number of strategies, the adoption of EVs emerges as a cornerstone for reducing GHG emissions and decreasing dependence on fossil fuels [16]. EVs offer a promising pathway for lowering the carbon footprint of transportation, aligning with international climate goals and national decarbonization targets [17,18]. Unlike traditional internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) that rely on gasoline or diesel, EVs run on electricity, which can be sourced from renewable energy [19,20]. This transition from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources is essential for achieving significant reductions in GHG emissions [21].

However, the journey towards widespread EV adoption is fraught with challenges that span technological, economic, regulatory, and infrastructural dimensions [22]. According to Hachem [23], collaboration across these domains is crucial for the smooth implementation of EVs. While much of the literature highlights the positive environmental impact of EV adoption, the transition from ICEVs to EVs presents significant concerns, primarily due to the need for a robust and efficient infrastructure to support the unique demands of EVs [24,25]. The technological challenges include advancing battery technology to improve range, upgrading the electrical grid, reducing charging times, and lowering costs [26,27]. Economically, significant investments are required to develop charging infrastructure and to incentivize consumers to switch to EVs [28]. In addition, this cost varies greatly based on the placement and the state of the electrical grid [29]. On the other hand, the development of an extensive charging network is essential to alleviate range anxiety and ensure convenient access to charging facilities in both urban and rural areas [30]. Mobile charging stations can be highly beneficial, particularly in areas where permanent charging infrastructure is not yet available [31]. Additionally, there are several regulatory hurdles that involve creating and enforcing policies supporting EV adoption, such as emissions standards, subsidies, and incentives for both manufacturers and consumers [32,33,34,35].

1.2. Aims and Contribution

This paper investigates EV adoption, focusing on the complexities, barriers, and possible solutions associated with infrastructure deployment. Therefore, the research question is defined as follows: What are the key challenges and potential solutions in developing the infrastructure necessary for the widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) to achieve sustainable decarbonization in the transportation sector? Through a comprehensive review of literature across engineering, energy, computer science, environmental science, social sciences, and other fields, this research aims to elucidate the multifaceted challenges that impede the progress of EV adoption.

Furthermore, this study highlights the critical role that infrastructure plays in facilitating the transition to EVs. Effective charging networks, seamless grid integration, and supportive policies are paramount to enhancing the viability and attractiveness of EVs. By examining these components, this paper seeks to provide a holistic understanding of the current landscape and propose actionable strategies to overcome the barriers to sustainable decarbonization through electric vehicle adoption.

To systematically address these challenges and propose viable solutions, this paper is structured as follows: The next section details the materials and methods employed in this study, providing a comprehensive overview of the research design and data collection techniques. This is followed by the results and discussion section, which includes an in-depth document analysis and content analysis to interpret the findings. This paper concludes with a section on recommendations, offering practical suggestions based on the research outcomes, and closing remarks that highlight the implications of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

To comprehensively investigate the challenges and opportunities associated with electric vehicle (EV) adoption and infrastructure development, this study employed a systematic literature review (SLR) methodology. An SRL collects, evaluates, and synthesizes all existing evidence on a specific topic, aiming to harmonize and interpret the findings [36]. It involves compiling and analyzing empirical clues to address a specific research matter, ensuring the process is transparent and replicable. Meanwhile, this method aims to incorporate all relevant, quality studies published on the subject [37]. The SLR approach allows for a thorough, structured examination of existing research across multiple disciplines, including engineering, energy, computer science, environmental science, social sciences, and others. Indeed, SLR studies focus on searching for pertinent primary research, extracting necessary information, and then analyzing and synthesizing the findings to achieve a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of the subject area [38]. By systematically identifying, selecting, and analyzing relevant studies, this method ensures a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge and highlights critical gaps [39]. This helps to define the areas for future research in order to fill the gaps [40].

2.2. Database Identification

The literature search was conducted through the “worlds’ largest abstract and citation database of scientific literature”—Scopus [41]. It is true that the Web of Science (WoS) is the oldest international and multidisciplinary database first introduced in 1964 as a tool for data search—Science Citation Index (SCI) [42]—and the only one in 2004, but then Elsevier introduced Scopus [43], which excels in breadth, encompassing a greater number of journals, including those with more recent publications [44]. It includes content from more than 5000 publishers globally, while a rigorous content selection strategy guarantees that solely high-quality resources are listed [41,45]. Martín-Martín et al. compared WoS and Scopus to Google Scholar [46], and they found that Google Scholar impressively retrieves a substantial portion of citations identified by both Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, capturing 95% and 92% of their citations, respectively, however, the unique citations detected by Google Scholar tend to exhibit lower scientific impact on average compared to those identified by WoS or Scopus, and approximately half of them originate from sources other than journals. This suggests that while Google Scholar offers a vast array of sources and languages, researchers may need to exercise caution in assessing the quality and relevance of the information retrieved. Moreover, for a study investigating the relatively new topic of EV adoption, Scopus offers a distinct advantage due to its expansive and current journal coverage, ensuring access to the latest research and developments in the field.

2.3. Keyword Definitions

The process of defining keywords and their combination is a critical step in conducting academic research [47,48]. By carefully selecting terms that are both precise and comprehensive, it is possible to effectively identify, retrieve, and evaluate relevant literature, ultimately enhancing the quality and rigor of research findings [49].

In selecting keywords for the search, terms that directly address the research topic of EV adoption and infrastructure development within the context of sustainable transportation and decarbonization efforts were carefully considered. Keywords and phrases used in the search included “electric vehicle adoption”, “challenges”, “EV infrastructure”, “charging infrastructure”, “charging networks”, and “grid integration”. Boolean operators (AND, OR) were employed to refine the search and ensure the inclusion of relevant studies. They define the link between queries and broaden or narrow the search [50].

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Defining inclusion and exclusion criteria that serve as guidelines for selecting studies to understand if they meet the specific requirements of the research question or topic of interest is another crucial step in literature-review-based academic research [51,52]. They prove that a literature review is conducted in a rigorous, transparent, and methodologically sound manner [53].

Inclusion criteria ensure that the selected studies are directly relevant to the research question or topic under investigation. The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

- ✓

- Studies published in peer-reviewed journals or reputable conference proceedings.

- ✓

- Publications dated from 2015 (after the Paris Agreement, the international treaty on climate change [54]) to 2024 in order to ensure the review includes the most recent and relevant research.

- ✓

- Research articles, reviews, case studies, books, and chapters that specifically address EV adoption, infrastructure development, or associated policy and economic implications.

- ✓

- Studies available in English.

The exclusion criteria included the following:

- ✗

- Articles that did not focus on the specified topics or lacked empirical data or theoretical analysis.

- ✗

- Publications such as opinion pieces, editorials, and non-peer-reviewed sources.

2.5. Scheme

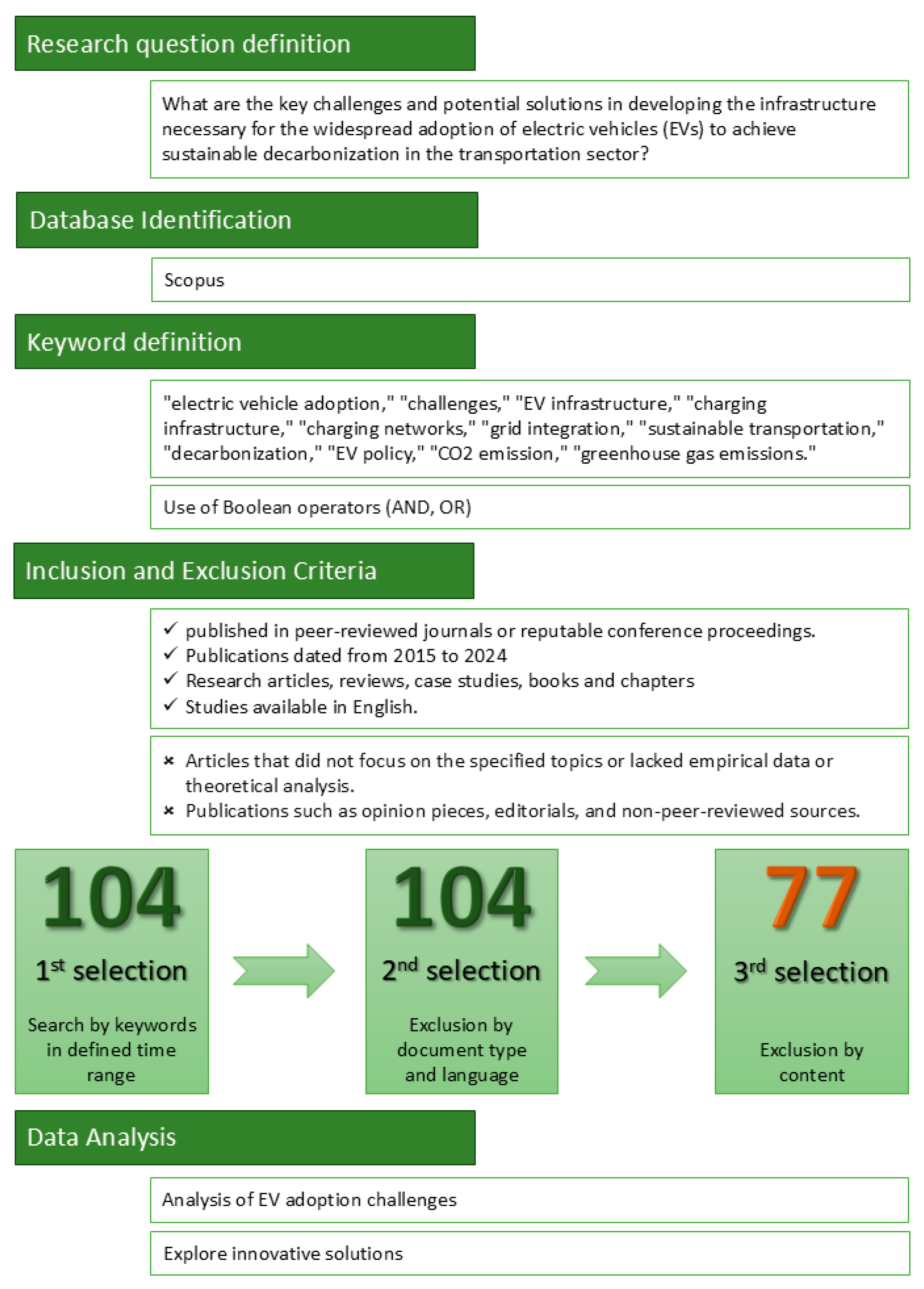

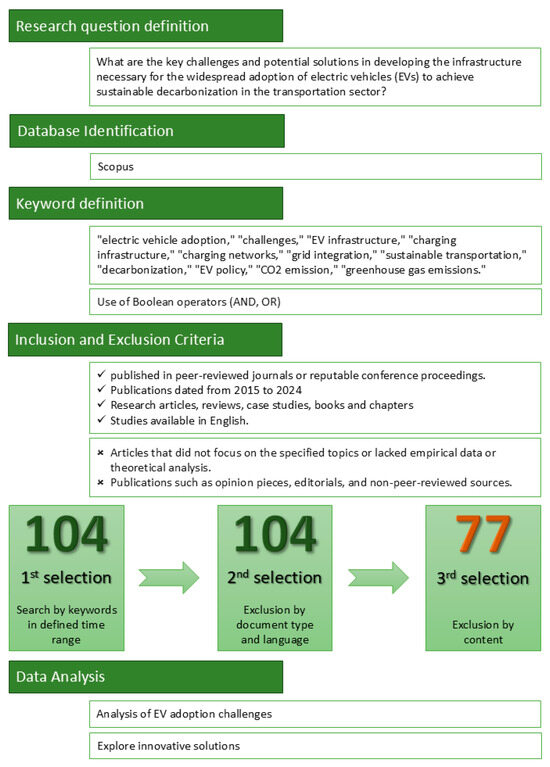

Figure 1 illustrates the methodology steps undertaken for this research. Initially, the research question formulated was the foundation for keyword structuring [55]. Subsequently, a suitable database was identified to ensure the inclusion of high-quality works.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of methodology.

Next, the selected keywords were integrated into the search string as follows: TITLE-ABS-KEY (“EV adoption” AND challenges AND (infrastructure OR “charging networks” OR “grid integration”)) AND PUBYEAR > 2014 AND PUBYEAR < 2025. Here, TITLE-ABS-KEY specifies that the search should look for the search terms in the title, abstract, and keywords of the articles; Boolean operators ensure that the search includes articles mentioning EV adoption and related challenges, specifically focusing on infrastructure, charging networks, or grid integration, thereby covering a wide range of relevant topics; the last part of the string already applies the inclusion criterion of articles published after 2014 and until 2024. This time frame was chosen to ensure the inclusion of recent and consistent research following the 2015 Paris Agreement.

This structured approach guaranteed a comprehensive search, capturing the most relevant studies in the field. As a result, 104 documents in total were obtained, including 45 articles, 36 conference papers, 18 reviews, and 5 book chapters. All 104 documents satisfied all inclusion criteria: they are high-quality, original research studies published in English.

2.6. Data Analysis

The extracted data underwent a detailed analysis. Initially, titles, abstracts, and keywords were reviewed to identify the most relevant studies. Five works were excluded due to restricted access to the full text. Subsequently, a full reading of these papers was conducted to exclude any items not directly or tightly related to this study’s objectives, narrowing the number of pertinent works to 77. The remaining works were analyzed to answer the defined research question. The analysis was organized into thematic categories that correspond to the primary challenges of EV infrastructure development and possible solutions.

2.7. Snowball Searching Strategy

Additional relevant papers were incorporated based on references and citations found within the initially identified literature [56]. These papers were considered crucial for enhancing the depth of the review, as they expanded on key concepts and provided further insights into emerging themes aligned with the study objectives. This extended inclusion contributed to a more comprehensive and well-rounded analysis.

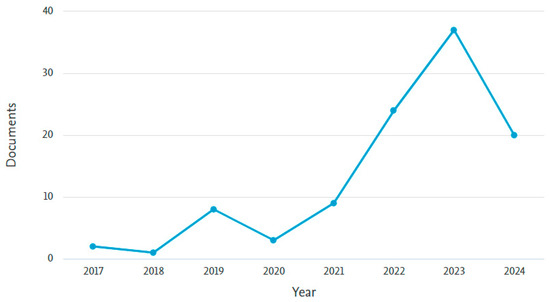

3. Results and Discussion: Document Analysis

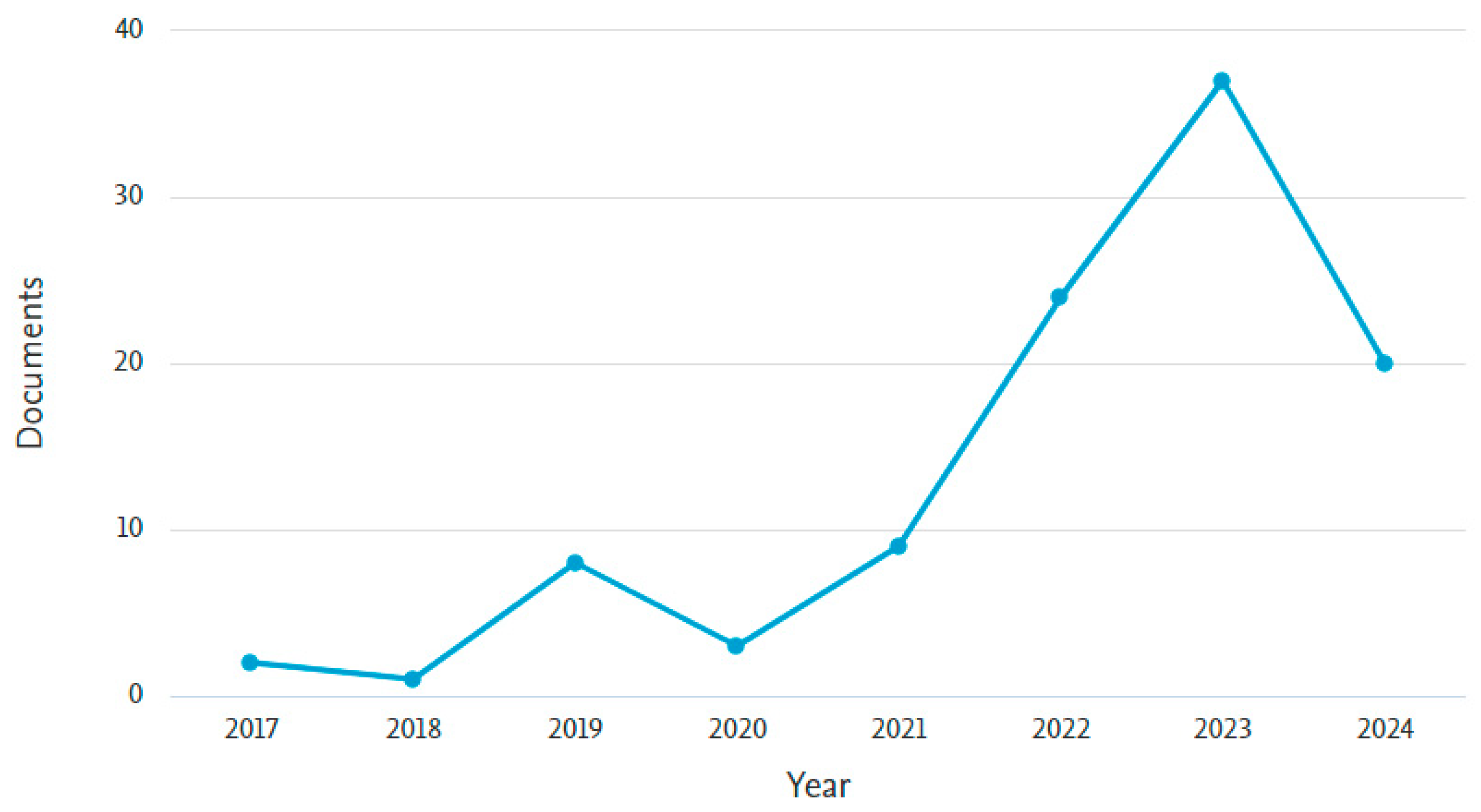

The analysis of publication trends over the years reveals a steady increase in research output related to electric vehicle (EV) adoption and infrastructure development. As illustrated on the Figure 2, in 2017, there were two publications, which slightly decreased to one in 2018. The number of publications saw a more significant rise in subsequent years, with eight in 2019, three in 2020, and nine in 2021. The upward trend continued, with 24 publications in 2022 and a substantial jump to 37 in 2023. By May 2024, there were already 20 publications, indicating a sustained interest and growing body of research in this field. This trend suggests that the topic of EV infrastructure is gaining momentum, likely driven by increasing global emphasis on sustainable transportation and decarbonization goals [15].

Figure 2.

Documents by year.

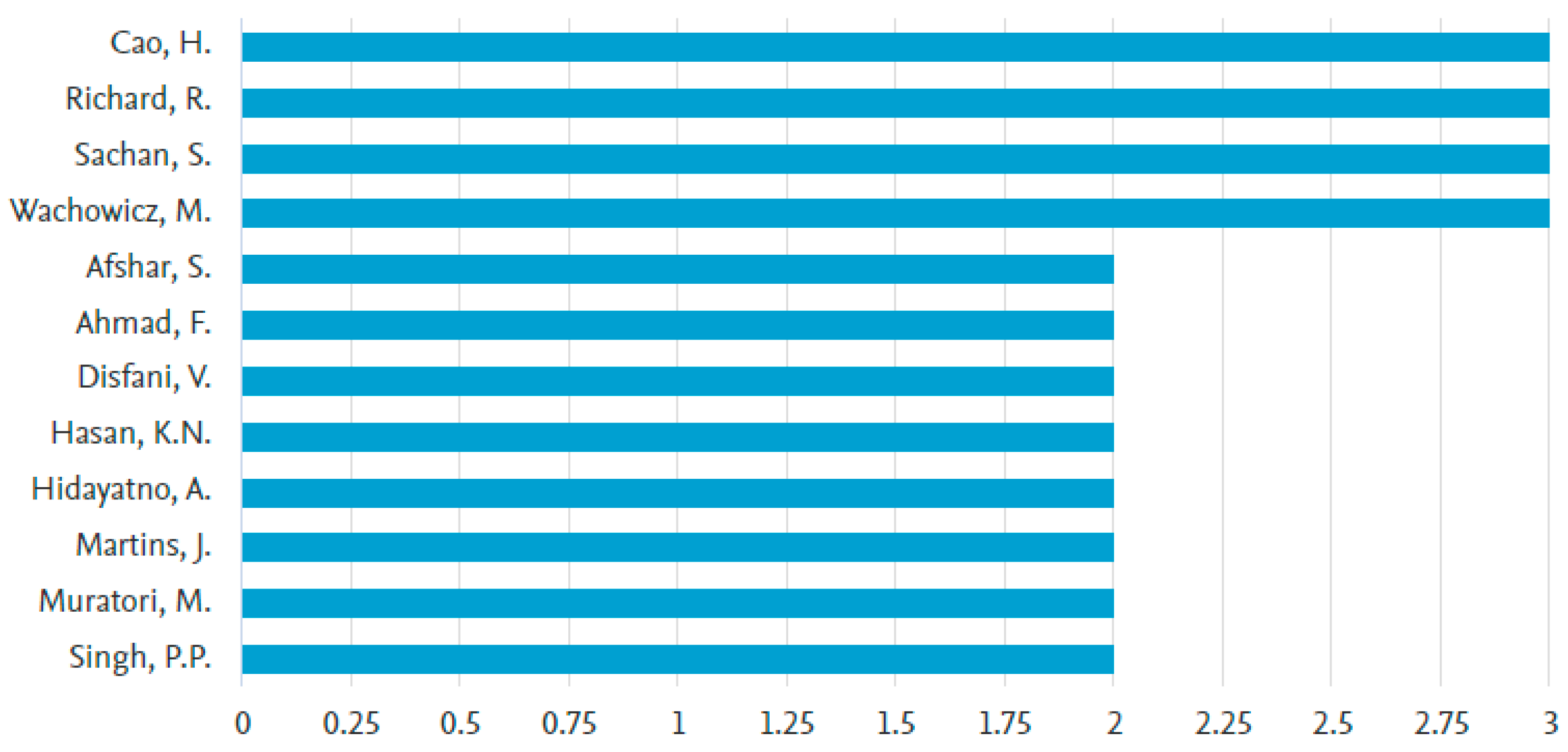

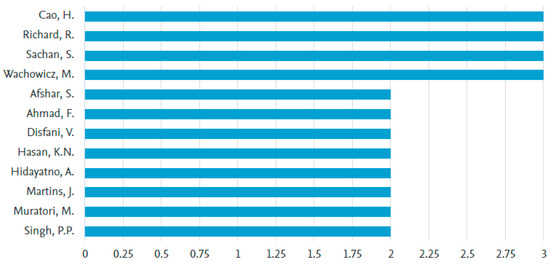

Examining the distribution of publications by authors reveals a diverse and collaborative research landscape, with no single author dominating, out of a total of 160 authors. As shown on the Figure 3, four authors have contributed three publications each, representing a geographically diverse cohort. Notably, two of these authors are affiliated with institutions in Canada, while the other two hail from Australia and India, respectively. Additionally, eight authors authored two publications each, spanning locations such as the United States, Australia, Qatar, Indonesia, Portugal, and Estonia. The remaining documents are authored by 148 individuals with a single publication. This dispersion of authorship underscores the inclusive and cooperative nature of the research community, showcasing a collective effort to advance knowledge in the field.

Figure 3.

Documents by author.

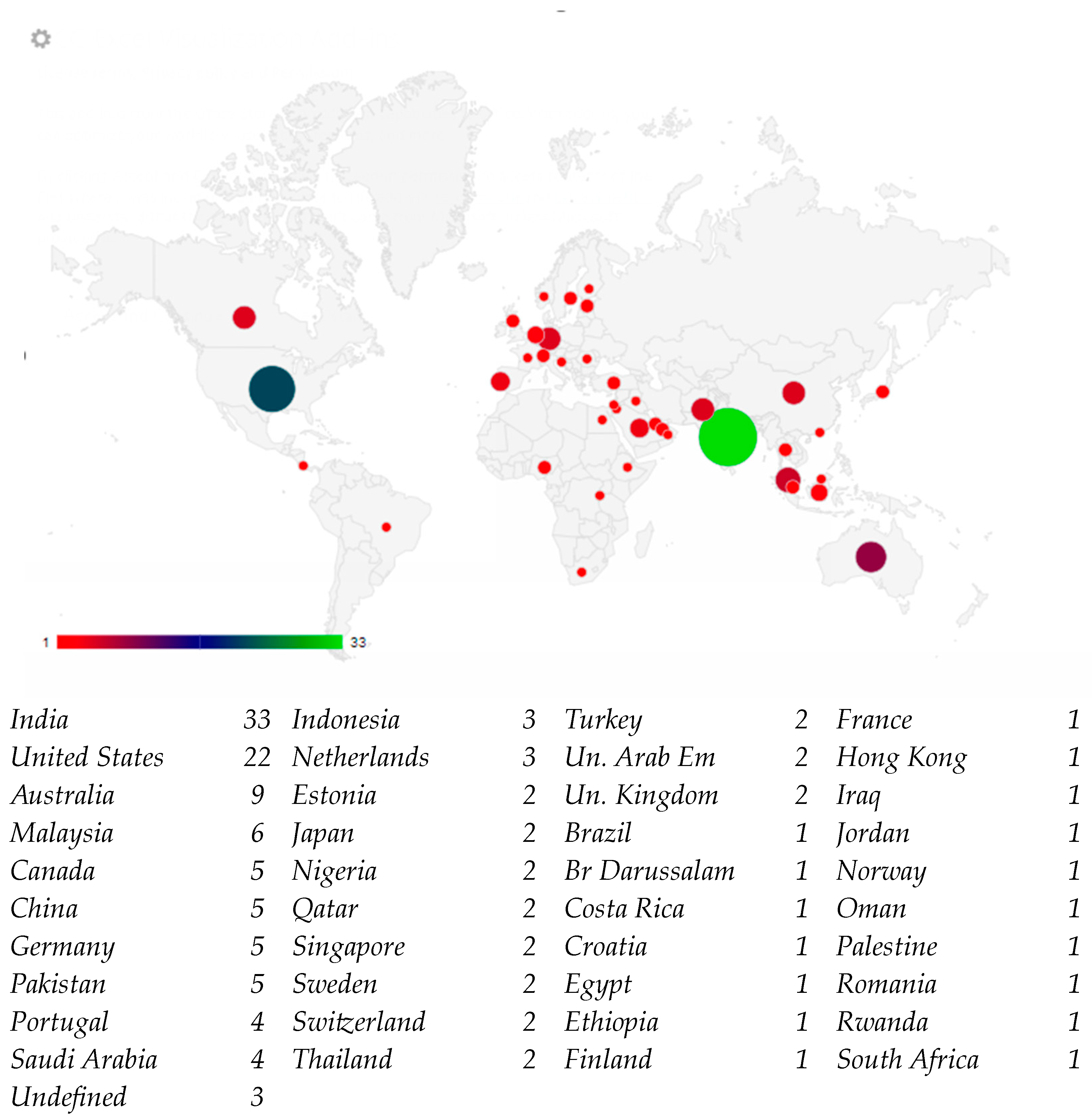

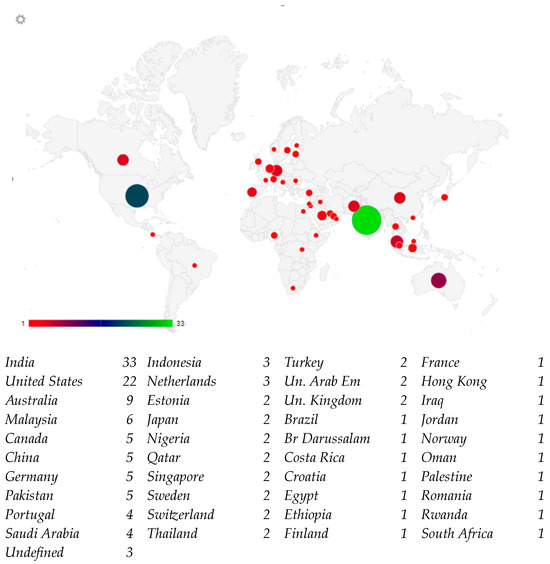

The geographical distribution of publications reveals a diverse global interest in EV adoption and infrastructure development. Figure 4 illustrates that India leads with 33 documents indicated with the largest circle on the map, followed by the United States with 22. Australia has contributed nine documents, while Malaysia has six. Canada, China, Germany, and Pakistan each have five publications. Portugal and Saudi Arabia have four documents each. Indonesia and the Netherlands have each contributed three documents. Several countries, including Estonia, Japan, Nigeria, Qatar, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom, have each contributed two documents. Other countries, such as Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Costa Rica, Croatia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Finland, France, Hong Kong, Iraq, Jordan, Norway, Oman, Palestine, Romania, Rwanda, and South Africa, have each contributed one document. There are also three documents where the country of origin is undefined.

Figure 4.

Documents by country.

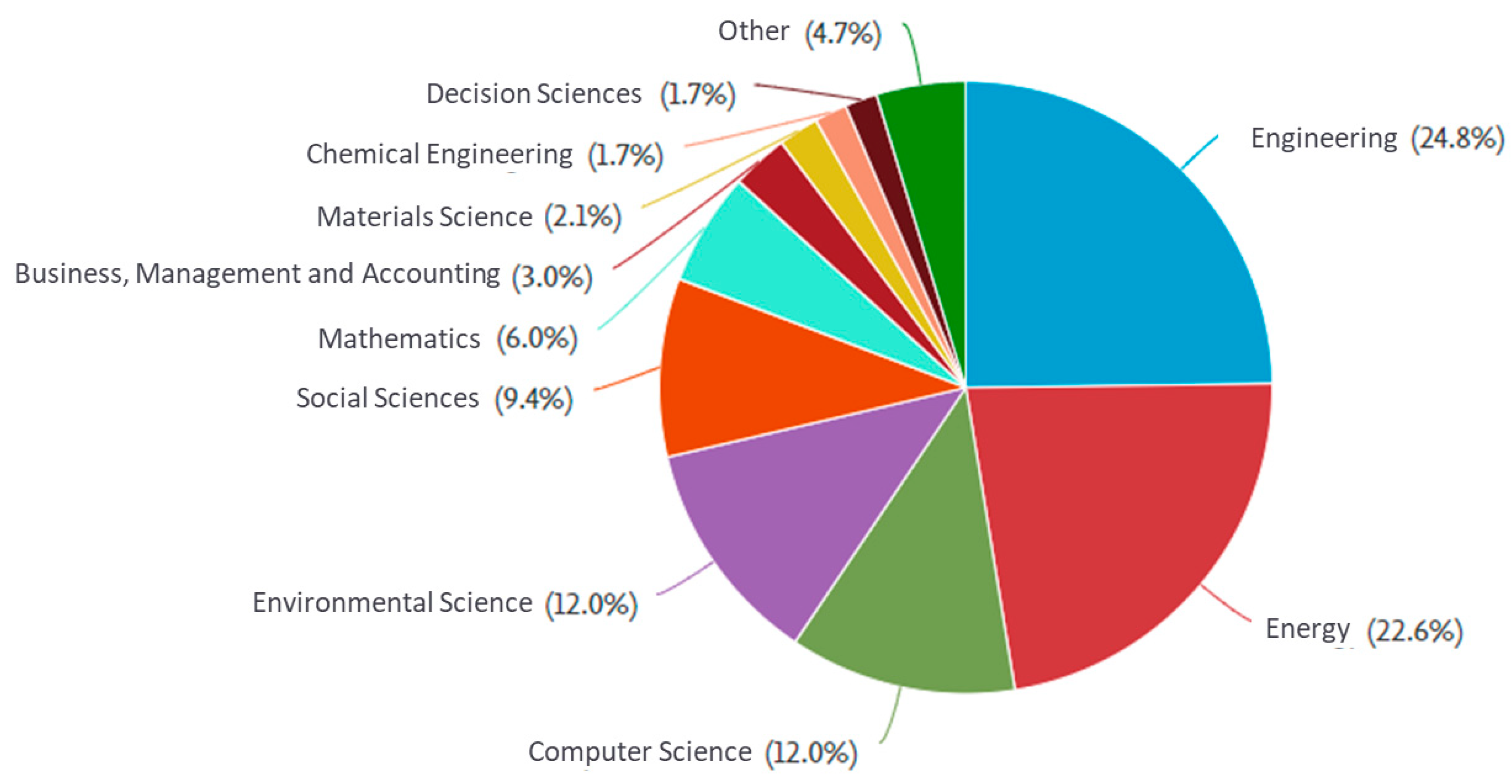

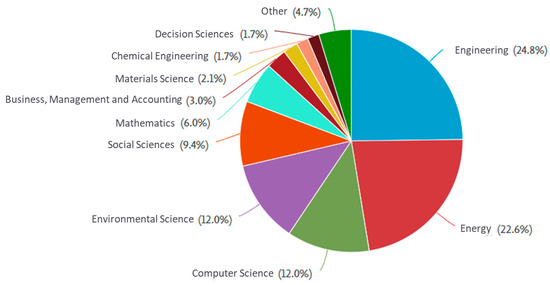

The subject areas of the documents illustrated on Figure 5 indicate the interdisciplinary nature of EV adoption and infrastructure research. The largest proportion of documents falls within Engineering (58 documents, 24.8%), followed by Energy (53 documents, 22.6%), Computer Science (28 documents, 12%), Environmental Science (28 documents, 12%), and Social Sciences (22 documents, 9.4%). This distribution highlights that the challenges and opportunities associated with EV infrastructure span multiple fields, requiring a multidisciplinary approach to address them comprehensively. The significant representation of engineering and energy studies underscores the technical and practical aspects of EV infrastructure, while the inclusion of social sciences points to the importance of policy, societal acceptance, and behavioral factors.

Figure 5.

Documents by subject area.

Overall, the increasing number of publications over recent years reflects the growing importance and urgency of developing effective EV infrastructure to meet sustainability and decarbonization targets. The absence of a dominant author suggests a collaborative field with contributions from a wide range of researchers, which can enhance the diversity of perspectives and solutions proposed. The interdisciplinary nature of the research underscores the complexity of the challenges involved, necessitating integrated approaches that combine technical, environmental, economic, and social considerations.

The substantial representation of engineering and energy-related documents highlights the critical technical and infrastructural challenges, such as the development of efficient charging networks and grid integration. The presence of computer science research points to the role of digital technologies and innovations in optimizing EV infrastructure. Environmental science contributions emphasize the broader ecological implications, while social sciences highlight the need for supportive policies and societal engagement to drive adoption.

4. Results and Discussion: Content Analysis

4.1. Are EVs Sustainable No Matter What?

The investigated literature consistently emphasizes the convenience and necessity of adopting EVs primarily due to their significant benefits in terms of sustainability, CO2 emission reduction, and environmental protection. The reduction in GHG emissions and air pollutants from the widespread adoption of EVs is seen as a key strategy in combating climate change and promoting sustainable development.

However, while the literature strongly advocates for the environmental benefits of EVs, some studies [14,57,58,59] highlight the critical role of renewable energy sources in the overall effectiveness of EV adoption. Barker et al. argue that merely transitioning to EVs is not sufficient to achieve the desired environmental outcomes unless the electricity used for charging these vehicles is derived from renewable and sustainable sources [60]. Without the integration of renewable energy, the environmental benefits of EVs could be undermined by the continued reliance on fossil-fuel-based electricity generation.

Moreover, Pamidimukkala et al. argue that renewable energy integration into the electrical grid is not enough to achieve the full sustainability of EVs since their principal component, the battery, is harmful to the environment, and this fact needs to be taken into consideration [61]. Similarly, Qadir et al. highlight the harmful impact of EV batteries on the environment due to their raw materials [62]. On the other hand, Galati et al. found that in the long run, EVs are more sustainable than ICEVs of the same category [63]. Authors argue that as the distance traveled increases, the environmental impact of electric vehicles diminishes, ultimately surpassing that of internal combustion vehicles, especially in the case of renewable energy usage.

Additionally, Sathyan et al. assert that besides the harmful impact of disposed batteries on the environment, EVs present further challenges since the heavy battery causes faster wear on tires, which are often discarded prematurely [64].

4.2. Scope of Inquiry: Road Transport Dominance in Electric Vehicle Studies

From the comprehensive analysis of the extant literature, a discernible trend emerges: the corpus of published works predominantly concentrates on the domain of road transport within the EV paradigm. The most common type of EV investigated across the literature is the passenger car. A notable subset of studies extends the investigation beyond passenger cars to encompass commercial vehicles. This category includes rental vehicles, fleet vehicles, taxis, buses, and trucks. Beyond passenger and commercial vehicles, several studies explore a broader spectrum of EV types. These include buses, industrial vehicles, medium and heavy-duty vehicles, agricultural machinery, riverboats, and even public transport systems. Some studies adopt a broader approach, investigating EV adoption across various vehicle types without specific categorization. These studies contribute valuable insights into the overarching challenges and solutions within the EV domain (see Appendix A for details).

Despite this categorical variance in the scope of EV types under investigation, a unifying thread pervades these scholarly endeavors: an exclusive focus on road transport. This discernible thematic homogeneity underscores the scholarly community’s collective preoccupation with elucidating the multifaceted dimensions of EV integration within terrestrial transportation frameworks. Consequently, while the modalities of EV analysis may diverge in terms of vehicular typologies, the overarching investigative purview remains steadfastly centered on the challenges and solutions germane to road-bound transportation modalities.

4.3. EV Adoption Challenges

Through an analysis of the literature, it became evident that widespread adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) presents distinct challenges in various countries and on a global scale. However, the literature also illuminates potential solutions aimed at facilitating the transition to EVs. This exploration seeks to streamline the process of transitioning to EVs by identifying and addressing these challenges while advocating for effective solutions.

This study is focused on the technical barriers to EV adoption. It delineates three primary categories of barriers: those linked to batteries, issues surrounding charging infrastructure and the grid, and EV users’ concerns regarding technical matters.

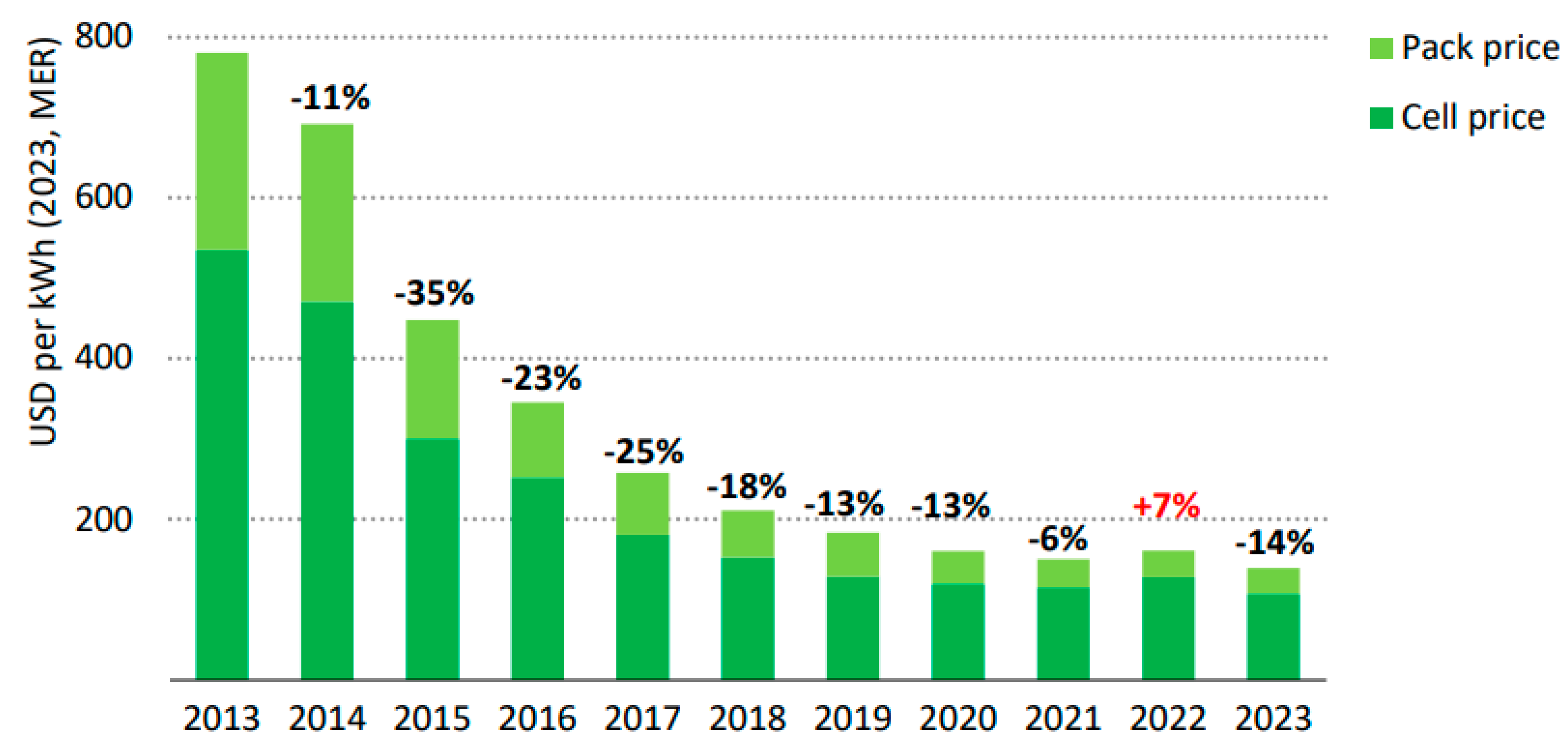

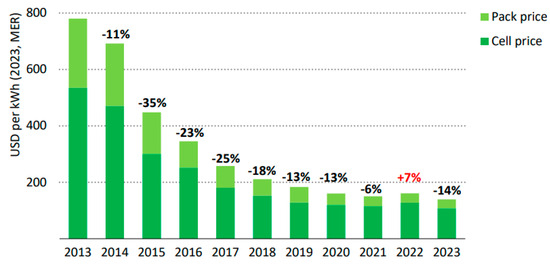

4.3.1. Battery

The development of EVs is heavily influenced by specific battery characteristics, which play a crucial role in determining their viability and market growth. Battery-related challenges present a multifaceted landscape. The most significant characteristics include energy density, charging speed, lifespan, safety, and cost [65,66]. Sachan et al. and Kore and Koul pose the challenge of EV battery prices and reliability that could be solved through local manufacturing in India, but essential materials for battery production are not available in the country [67,68]. In addition, there is a lack of a coordinated network of stakeholders, which further complicates efforts to address this identified issue. Also, associated investment-related risk delays the battery manufacturing development process in the country. On a global landscape, according to Galati and colleagues [69], the high price of the battery, representing 75% of the vehicle cost, is a factor in the disruption of EV adoption. However, recent trends in this industry demonstrated a considerable fall in the prices of lithium-ion batteries, 90% of which are used in transport electrification, due to R&D and technological advancement (Figure 6) [70]. Although prices rose slightly in 2022 (+7%), this increase was not substantial compared to the overall downward trend over previous time spans.

Figure 6.

Lithium-ion battery pack and cell prices, 2013–2023 (source: [70]).

The technical characteristics of a battery, particularly its capacity, emerge as a primary concern within this domain. Delving deeper, the overwhelming majority of the literature (see Appendix A) underscores the critical significance of both range and lifetime limitations of batteries, directly impacting the operational effectiveness of EVs. In addition, when batteries are depleted, there are disposal issues because of their harmful impact on the environment, while recycling batteries faces technical and logistical hurdles, including the efficient extraction of valuable materials and the proper disposal of hazardous components [61,62,64,71,72,73,74,75].

Energy density—how much energy the battery can store relative to its weight—and current limitations in this area present major challenges. The weight of a battery impacts the speed of an EV [76]. Also, factors such as energy density and power also influence battery performance and suitability for EV applications since they directly impact the driving range of EVs [62,77,78,79]. While advancements have been made in lithium-ion batteries, the energy density is still lower than needed for long-distance travel without frequent recharging [80].

Another limiting factor is the charging speed, which is constrained by battery chemistry and infrastructure [26]. Long charging times create a significant barrier to widespread EV adoption, especially compared to the refueling times of internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), and frequent fast charging accelerates battery degradation, reducing the overall lifespan and increasing thermal stress [81]. Ineffective thermal management can lead to overheating, reducing battery efficiency, lifespan, and safety [82]. Lithium-ion batteries are prone to thermal runaway, a hazardous situation triggered by mechanical damage, electrical faults like overcharging or short circuits, or exposure to extreme temperatures [83].

Safety concerns loom large, particularly in scenarios where batteries are subjected to frequent fast charging, which can lead to overheating and, in extreme cases, pose a fire risk. Moreover, the accelerated charging process tends to also accelerate battery degradation, thereby shortening its operational lifespan. These factors collectively compound the apprehensions surrounding battery reliability and safety, underscoring the need for robust solutions in the EV ecosystem [71,84,85,86,87,88].

Estimating the state of charge (SOC) and state of health (SOH) of batteries accurately is critical to maximizing EV performance and safety [89]. However, real-time estimation is challenging due to the complexity of battery chemistry [90]. Other challenges include the inability to apply laboratory-based methods in real-world conditions, difficulties in accounting for environmental factors like temperature and driving conditions, and the limitations of current models in handling dynamic, real-time data during actual vehicle operations [91]. New methods such as machine learning and advanced algorithms, like Kalman filters, are being explored to improve the accuracy and reliability of these estimates, but they require significant computational power and sophisticated sensors [92,93].

4.3.2. Infrastructure

The foremost challenge concerning charging stations, as evidenced by the literature analysis, is their scarcity (see Appendix A). This scarcity exacerbates range anxiety among customers and compounds battery capacity issues, thereby significantly impeding the widespread adoption of electric vehicles. A key barrier to expanding the number of charging stations is the high implementation cost, as highlighted by numerous researchers [14,31,61,68,75,77,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109]. These costs encompass not only the installation of charging stations but also their future maintenance and operational costs, as well as the necessary upgrades to electrical grid infrastructure to support increased demand [14,68,77,94,95,107,109].

Insufficiently deployed charging infrastructure appears no less important for delaying widespread EV adoption [14,62,68,71,78,84,87,99,100,103,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121]. As noted by these authors, the strategic placement of charging stations is crucial for optimizing their utility and ensuring their accessibility to EV owners. If the location of charging stations is not carefully planned to align with the demand for charging, vehicle routes, and the distance between chargers, the effectiveness of the infrastructure may be compromised.

According to Hall and Lutsey [122], a significant issue is the long permitting processes for charging station installation, particularly in urban areas, where regulatory hurdles can delay development. Authors state that simplifying and expediting these processes, alongside streamlining government approvals, could accelerate the deployment of new charging stations.

In addition to the aforementioned challenges, it is crucial to consider the specific characteristics of the charging infrastructure itself. One prominent issue highlighted in the literature is the significant impact of charging time on EV adoption rates and overall user experience. As indicated in Appendix A, charging time emerges as a recurring concern across various studies, reflecting its critical importance in shaping EV demand, since it can disrupt users’ daily routines and limit the flexibility of travel plans, particularly during long-distance trips. On the other hand, batteries have safety issues, such as overheating and catching fire, especially when using fast charging [71,85,86,87,88].

Another challenge is related to the electrical grid. As the number of electric vehicles on the road increases, there is a corresponding rise in demand for electricity to power these vehicles. Without proper management and planning, this surge in demand can lead to grid overloading, where the existing infrastructure struggles to handle the increased load. This can result in power outages, voltage fluctuations, and other disruptions in electricity supply, impacting both the charging process and overall grid reliability. Indeed, electrical grids have operational limits beyond which they may become unstable or unsafe (see Appendix A).

Furthermore, challenges in standardization and compatibility with urban planning further complicate the implementation process [14,31,62,64,68,73,77,99,102,110,111,117,118,121,123,124]. Standardization refers to the establishment of uniform technical specifications, protocols, and interfaces across different components of EV charging infrastructure. These standards are crucial for interoperability, ensuring that EVs from various manufacturers can utilize charging stations seamlessly.

In addition, Lohawala and Spiller highlight the need to address sustainability concerns and integrate renewable energy sources into charging infrastructure [94]. Challenges such as solar intermittencies, energy flow management, and compatibility with energy storage systems underscore the importance of sustainable charging solutions [125].

Some authors highlight the significant issue of the lack of technical assistance for charging and grid infrastructure following their implementation [74,79,85]. This absence of support leads to challenges in maintaining and ensuring the proper functioning of these systems. Consequently, the effectiveness and reliability of the infrastructure are compromised. Consequently, another challenge lies in ensuring grid resilience against fluctuations due to increased EV charging.

Finally, Meyur et al. underscore the risks associated with insufficient personal data protection resulting from the digitalization of charging infrastructure [102]. Moreover, James et al. highlight the heightened cybersecurity threats arising from the integration of charging infrastructure with various digital systems [103].

4.3.3. EV Users

According to the analyzed literature (see Appendix A), the main barriers for potential EV users are range anxiety and high purchasing and maintenance costs. Some authors emphasize the importance of battery price and the need for replacement. Khalid and Khuman argue that the total cost of ownership of EVs is higher than that of corresponding ICEVs, making it difficult for EVs to spread widely [75]. Javadnejad et al. [86], van der Koogh et al. [119], and Trinko et al. contend that high electricity prices and their uncertainty deter customers from purchasing EVs [126].

Additionally, Sathiyan et al. (2022) identify top speed as a critical factor in the EV purchase decision, alongside range capacity and price [79]. Pamidimukkala et al. highlight the issue of insufficient support centers and facilities for EV repair and maintenance [61].

4.4. Identified Solutions for EV Adoption

4.4.1. Government Measures and Financial Interventions

The majority of the literature (see Appendix A) emphasizes the importance of government measures and financial incentives to drive EV adoption. These measures include subsidies for purchasing EVs, tax incentives, and investment in charging infrastructure. Financial interventions are essential to reduce the upfront cost of EVs and make them competitive with ICEVs. Sachan and Singh advocate for stringent policies to shift to EVs [14], which can accelerate adoption rates significantly. Nath et al. suggest mandating EV infrastructure in building bylaws, facilitating land access, and supporting the private sector in the development of the infrastructure [127]. Javadnejad et al. suggest more concrete solutions, such as government intervention for battery warranty, leasing, and exchange programs since the main cost-related problems of EVs are connected to the battery price and maintenance [86]. Mittal et al. argue that investing in battery manufacturing is paramount [71]. Indeed, Templeton et al. (2023) find governmental intervention necessary for improving batteries and increasing their range [106]. Qadir et al. propose R&D grants to improve battery life and efficiency, which can further alleviate range anxiety and reduce the total cost of ownership [62].

In recent years, China accounted for over 40% of the world’s EV sales, making it a pivotal player in the EV transition [128]. This dominance is primarily driven by comprehensive government policies and an aggressive push towards electrification [129]. China’s strategy revolves around a combination of government subsidies and fiscal incentives aimed at reducing the initial cost of EVs for consumers [130]. Programs offering direct consumer subsidies and tax incentives have been a major factor in boosting EV sales. A cornerstone of China’s EV strategy is its investment in charging infrastructure [131]. By 2023, China had built the world’s largest network of charging stations, including fast charging options to reduce downtime for EV users [132]. Furthermore, the battery-swapping technology has gained traction as a solution to long charging times, a significant barrier to adoption [133]. The government’s proactive role in supporting both the development of charging infrastructure and the advancement of battery technologies, such as those incorporating renewable energy sources, has positioned China as a leader in clean transport innovation.

In this line, a number of articles (see Appendix A) support the integration of renewable energy sources into the EV charging infrastructure. By promoting the use of clean energy, governments can ensure a sustainable and environmentally friendly transition to electric mobility, as well as guaranteeing power supply and grid stability.

4.4.2. Improvement of Battery Technology

Battery technology is a critical area for improving EV adoption. Indeed, many researchers (see Appendix A) suggest that advancements in battery technology can enhance the performance and range of EVs, addressing one of the primary concerns of potential EV users. Acharige et al. highlight the importance of improving battery materials and capacity [77]. Ghatikar et al. discuss the need for standardizing battery specifications that simplify battery charging and swapping [134]. Indeed, a lot of works find convenient battery-swapping solutions (see Appendix A). Kumar et al. propose implementing battery energy storage systems (BESSs) for peak times of the day [124].

Jain et al. and Sathiyan et al. highlight innovative solutions such as thermal management systems to prevent battery deterioration, ensuring longer battery life and better performance in varying climates [79,85].

4.4.3. Charging Infrastructure Expansion and Technological Advancements

Expanding the network of charging stations is a recurring solution among various sources. A comprehensive charging infrastructure that includes public, private, and residential charging stations is advantageous. A number of works emphasize strategic planning and optimal placement of charging stations to meet the growing demand effectively (see Appendix A). Babic et al. and Jain et al. suggest transforming some existing parking lots to EV parking with charging possibility [85,118]. The number should increase as EV ownership spreads. Also, EV parking occupancy will need to be monitored to avoid ICEV parking. Pamidimukkala et al. suggest establishing a policy on parking charges to overcome this problem [61]. Behl et al. propose an autonomous robot EV charger, which can navigate parking lots, locate EVs, and charge them while the driver is away [117].

Managed charging systems and innovative business models such as Transportation-as-a-Service (TaaS), EV sharing, or car-pooling are recommended to optimize the utilization of charging infrastructure [62,72,135]. Additionally, Trinko et al. propose the concept of “Charging-as-a-Service” (ChaaS) [126], where third parties manage the design, operation, and maintenance of charging infrastructure. Many works reviewed (see Appendix A) propose incentivizing the installation of fast charging stations in public areas to enhance convenience for EV users. Wireless charging, as a solution, is widely discussed in the literature [14,31,74,76,79,100,104,135,136].

Mo et al. and Mamidala and Prajapati discuss the integration of advanced technologies such as AI, 5G, and smart grids to improve the efficiency and convenience of EV charging [74,100].

4.4.4. Renewable Energy Integration and Smart Charging

Integrating renewable energy sources into the EV charging infrastructure is crucial for sustainability. Lohawala and Spiller suggest the incorporation of solar panels and storage systems at charging stations to reduce reliance on the grid and ensure a stable energy supply [94]. Many works advocate utilizing chargers paired with renewable sources in general for efficient and sustainable charging.

Also, many works (see Appendix A) highlight the potential of vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology, which allows EVs to feed electricity back to the grid, balancing energy demand and supply. V2G technology allows EVs to act as energy storage units that can return electricity to the grid, aiding in energy management and stability. Despite its potential, V2G faces several hurdles, including battery degradation due to frequent charge–discharge cycles, lack of standardization in communication protocols, and the need for bi-directional chargers, which are still costly. Furthermore, large-scale adoption would require new infrastructure investments and regulatory frameworks [137,138]. Sumanasena et al. emphasize the use of AI for optimizing charging demand and supply, making the entire system more efficient and reliable [110].

4.4.5. Stakeholder Collaboration and Policy Support

Collaboration between various stakeholders, including government bodies, private companies, and researchers, is essential for the successful adoption of EVs. Indeed, many works stress the importance of a collaborative approach for developing and implementing effective policies and infrastructure. Van der Koogh et al. (2023) argue that even to achieve the final goal of widespread EV adoption, different stakeholders have different interests in this process, and the authors recommend considering the preferences and needs of all of them, including the general public, to ensure a smooth transition to electric mobility [119].

Appendix A provides a concise summary of the challenges associated with the widespread adoption of EVs as identified in previous literature, along with potential solutions.

4.4.6. Technical Skills Gap

It is observed that there is a substantial lack of expertise in India [67,68,71,85,107,139,140] and in other developing countries [71]. Sachan et al. pointed out the absence of experts in the EV field in India [67], which hampers the development of a robust domestic EV industry. Kore and Koul, Mittal et al., and Jain et al. identified a lack of technical skills among the workforce in India as a critical challenge in India’s EV industry [68,71,85]. The shortage of qualified professionals with expertise in EV technologies can limit the pace of innovation and hinder the development of EV-related infrastructure and services. Haider et al. (2019), Kumar et al. (2020), and Muthulakshmi et al. (2023) discuss the problem of repair, technical assistance, service, and maintenance for EVs that is caused by a lack of local expertise [84,139,140].

Asif et al. highlighted the broader challenge of a lack of technical expertise in developing countries, which include are but is not limited to India [72]. This overarching issue underscores the need for capacity-building and knowledge-transfer initiatives to support the development of sustainable transportation solutions in these regions.

5. Conclusions

The successful adoption of EVs depends not only on the vehicles themselves but significantly on the supporting infrastructure. The extensive review of literature on EV adoption and infrastructure deployment underscores the multifaceted challenges and potential solutions inherent in transitioning towards sustainable transportation systems. The analysis revealed that while EVs offer promising avenues for reducing GHG emissions and mitigating climate change, significant barriers exist.

Further research and action are needed in the battery technology field. Precisely, scientists need to focus on advancing battery technology to enhance energy density, lifespan, and safety, addressing critical concerns that hinder EV adoption. In addition, used batteries pose a significant challenge to the environment when they are discarded. Research into recycling and repurposing battery materials is crucial to mitigate the negative effects on the environment and ensure sustainable lifecycle management.

Additionally, research should explore innovative solutions for integrating renewable energy with EV infrastructure to promote sustainability. It is important to recognize that electricity used for EV charging can also be generated from fossil fuels, which would undermine the environmental benefits of EV adoption. Therefore, prioritizing the use of renewable energy sources for EV charging is essential to maximize the sustainability and climate benefits of EVs.

Companies can also develop new business models, such as car-sharing, battery leasing, battery swapping, and Transportation-as-a-Service (TaaS) or partnerships with renewable energy providers, to make EV ownership more attractive and affordable. Innovative business models can incentivize the use of EVs and optimize the utilization of charging infrastructure.

Equally important is the development of robust charging infrastructure and ensuring the reliability of the electrical grid to meet increasing demand. Governments and businesses should invest in expanding and optimizing charging networks, prioritizing strategic locations to alleviate range anxiety. Furthermore, integrating smart grid technologies can enhance grid resilience and efficiency, accommodating the additional load from widespread EV usage.

The lack of expertise in the field also presents a significant challenge. When customers encounter technical problems with their EVs, resolving these issues can be difficult due to the scarcity of knowledgeable technicians. This expertise gap not only impacts repair and maintenance but also results in higher service costs compared to ICEVs. Addressing this issue requires targeted training programs and educational initiatives to build a skilled workforce capable of supporting the growing EV market.

Government intervention and financial incentives play a crucial role in driving EV adoption by reducing upfront costs and fostering a supportive ecosystem for sustainable transportation. By prioritizing investments in research and development, providing clear regulatory frameworks, and fostering collaboration, stakeholders can pave the way for widespread EV adoption and realize the potential benefits of EVs for environmental sustainability.

6. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Avenues

The implications of this study extend to policymakers, industry stakeholders, researchers, and the general public. By highlighting the challenges and potential solutions associated with EV adoption and infrastructure deployment, this study provides valuable insights for informed decision-making and strategic planning in the transition towards sustainable transportation systems. This paper contributes to the growing body of research on electric vehicle (EV) adoption by offering a multi-dimensional analysis of the challenges involved in infrastructure deployment and presenting integrated solutions. The innovative contributions of this paper include the following: (1) an in-depth analysis of how grid resilience and renewable energy integration can enhance the sustainability of EV charging infrastructure; (2) the identification of novel business models, such as battery leasing, Transportation-as-a-Service (TaaS), and partnerships with renewable energy providers, which can accelerate adoption by reducing consumer costs and mitigating infrastructure challenges; and (3) a strategic framework for public–private collaboration in overcoming regulatory and financial barriers to EV infrastructure development. By emphasizing these aspects, this paper not only contributes to academic discourse but also provides actionable insights for policymakers and industry leaders in their efforts to scale up EV infrastructure for sustainable transportation.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Firstly, the scope of the literature review was primarily focused on academic sources, which may not fully capture industry perspectives and practical insights. Therefore, future research should incorporate a broader range of sources. In addition, the defined keywords might not be sufficient to search for and include all relevant studies in the field. To minimize this limitation, the snowball strategy was used, and extended literature was included, but this is still not a guarantee that all works are covered. Additionally, considering longitudinal studies would provide more comprehensive insights into the evolving landscape of EV adoption and infrastructure deployment.

Building upon the insights from this study, future research could focus on detailed cost analysis and forecasting regarding the infrastructure development of EV charging stations. Specifically, quantitative assessments of different cost types, including installation, maintenance, and operational expenses, could provide a more nuanced understanding of financial challenges. Additionally, exploring the prospective density of charging stations relative to the increasing number of EV users would offer valuable foresight for urban planners and policymakers. Furthermore, future studies could adopt a mixed-method approach, combining literature review with empirical data collection or modeling techniques, to generate more concrete forecasts. This focus on forecasting and cost evaluation would complement our findings and further support effective EV adoption strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and N.A.; methodology, N.A.; formal analysis, N.A.; investigation, N.A.; resources, N.A.; data curation, N.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.; writing—review and editing, A.T.; visualization, N.A.; supervision, A.T.; funding acquisition, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data are provided in Appendix A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Evidence from the literature.

Table A1.

Evidence from the literature.

| Source | Country of Investigation | Type of EV | Problem | Solution | ||

| Battery | Charging Infrastructure | EV Users | ||||

| Sachan et al., 2023 [67] | India | Road transport: passenger car and other vehicles | Limited materials for battery manufacturing; lack of coordinated network of stakeholders; investment-related risk | Scarce charging stations | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | |

| Kore and Koul, 2022 [68] | India | Road transport: not disclosed | Capacity limits: range; imported battery; standardization; limited materials for battery manufacturing | Insufficiently developed and deployed charging infrastructure; weak grid infrastructure; standardization issues; high implementation and maintenance costs | EV purchasing cost; battery cost | Government measures, financial interventions; differentiate energy sources to provide an uninterrupted energy supply |

| Haider et al., 2019 [139] | India | Road transport: passenger cars | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Limited and insufficiently developed stations; electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; high maintenance cost | Improve battery technology; enhance power infrastructure to meet energy demands; invest in expanding charging infrastructure; implement EV-supporting policies and financial interventions |

| Kumar et al., 2020 [140] | India | Road transport: various types | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Scarce charging stations; charging times; electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery) cost | Government financial and policy interventions to support EVs; R&D; develop a network of public and private charging facilities; battery swapping; energy source differentiation (including renewable) |

| Muthulakshmi et al., 2023 [84] | India | Road transport: various types (personal cars, buses, two- and three-wheeled vehicles) | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; safety issues | Limited and insufficiently deployed charging stations; electrical grid limitations; charging times | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery replacement) cost | Improve electrical grid capacity; expand charging infrastructure; subsidize EV adoption; improve battery technology; establish service centers for EV maintenance |

| Mittal et al., 2024 [71] | India | Road transport: various | Capacity limits: range; safety issues; recycling issues | Limited and insufficiently deployed charging stations; electrical grid limitations charging times | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Invest in battery manufacturing; provide financial incentives for EV manufacturing and purchasing; R&D and collaborative approach; support the creation of local charging infrastructure and offer additional incentives based on each state’s unique needs; battery swapping; establishment of EV public transport |

| Jain et al., 2023 [85] | India | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; safety issues | Limited charging stations; electricity grid limitations lack of technical support | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Financial incentives for EV manufacturing and adoption; expand charging stations in parking lots; thermal management systems to prevent battery deterioration |

| Asif et al., 2021 [72] | Developing countries | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: lifetime; efficiency; recycling issues | Limited local manufacturing capabilities; incompatibility of charging infrastructure; charging times | EV purchasing and maintenance cost | Develop suitable business models like battery leasing, battery swapping, and Transportation-as-a-Service (TaaS); implement policies such as subsidies, quotas, penalties, and incentives; invest in charging infrastructure; develop common industry standards for EV technology |

| Çelik and Ok, 2024 [141] | Turkey | Road transport: not specified | Underdeveloped charging infrastructure | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Strategic planning for charging infrastructure distribution | |

| Bitencourt et al., 2023 [135] | Brazil | Road transport: passenger cars and commercial vehicles (renting) | Limited charging stations; investment-related risks | EV purchasing cost | Government incentives—subsidies and discouraging ICEs; innovative business models (EV sharing); move towards smart grids with increased EV usage—wireless charging, battery swapping, home charging; collaboration between stakeholders | |

| Kumar et al., 2021 [59] | India | Road transport: passenger cars and other modes | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; charging times; electrical grid safety issues | EV purchasing cost; battery cost | |

| Elsanabary et al., 2024 [142] | Malaysia | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; instability of energy supply at charging stations due to electrical grid limitations; charging times | Comprehensive approach for hybrid fast charging stations near highways; power management strategy integrating various energy sources; optimized tuning control using improved Snake Optimizer algorithm for high performance of grid-connected VSIs | |

| Richard et al., 2022 [143] | Canada | Road transport: various | Capacity limits: range | Insufficiently developed charging infrastructure | Market-based deployment of charging infrastructure | |

| Patil et al., 2022 [144] | Canada | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; prolonged charging times | Distribution of charging systems in crowded zones | |

| Singh et al., 2023 [145] | China | Road transport: various types | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; instability of energy supply at charging stations due to electrical grid limitations; charging times | Charging station placement; scheduling of charging activity | |

| Afshar et al., 2021 [31] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars and other vehicles | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; charging times; high implementation costs; standardization issues | Range anxiety | Developing mobile charging, fixed charging, and contactless charging technologies (battery-swapping and wireless charging lanes) |

| Sathyan et al., 2024 [64] | India | Road transport: various types | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; recycling issues | Limited charging stations; charging times; standardization issues; energy stability at charging stations due to electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Strategic investment to better plan infrastructure deployment and improve technical components of EVs (such as batteries); collaboration between stakeholders, especially policymakers; smart charging systems to avoid overload on charging stations; using different energy sources to guarantee a stable energy supply |

| Qadir et al., 2024 [62] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars and commercial vehicles (businesses) | Capacity limits: range, energy density; recycling issues | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; charging times; standardization issues energy stability at charging stations due to electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Financial incentives for EV adoption (for businesses and end-users); high-power charging infrastructure; differentiate energy sources; residential charging; advancing battery technology through R&D grants; innovative business models (EV sharing, car-pooling); establishing micro-factories |

| Kumar et al., 2023 [146] | Not specified | Not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; charging times | Power scheduling scheme—balancing the charging demands of EVs with the power supply capabilities | |

| Sumanasena et al., 2023 [110] | Australia and USA | Road transport: passenger cars, commercial vehicles, and industrial vehicles | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; charging times; concerns regarding proper functioning of electrical grids amidst increasing demand and diverse energy sources; standardization issues | Use AI for optimizing charging demand and supply | ||

| Acharige et al., 2023 [77] | Worldwide | Road transport: various types | Capacity limits: range, energy density, lifetime | Limited charging stations; charging times; concerns regarding grid integration, stability, and safety; increased load demand, voltage fluctuations, and power quality issues; standardization issues; infrastructure development costs | Increase the number of stations and decrease charging time; improve battery materials and capacity; use different sources including renewable; contactless charging technologies (wireless charging); smart grid technologies; R&D | |

| Viana et al., 2019 [111] | Not specified | Road transport: passenger cars and other vehicles | Capacity limits: range | Insufficiently deployed stations; charging times; standardization issues; electrical grid safety | Development of integrated charger topologies; implementation of bidirectional power transfer capabilities for vehicle-to-grid (V2G) and vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) applications; R&D of charging infrastructure (integration of fault-blocking capability using body diodes, SPDT contactors for mode reconfiguration, and PI controllers for control system design) | |

| Anwar et al., 2022 [147] | USA | Road transport: not specified | Overloaded grid infrastructure | Managed charging | ||

| Lohawala and Spiller, 2023 [94] | USA | Road transport: medium and heavy-duty vehicles | Challenges in energy generation capacity and renewables integration; significant grid investment required; high costs associated with charging infrastructure, including make-ready infrastructure and fast chargers | Managed charging; vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology; solar panels and storage at charging stations; battery swapping; government intervention | ||

| Panossian et al., 2022 [95] | USA | Road transport: any type | Limited infrastructure capacity considering increasing demand; concerns regarding grid stability and safety; infrastructure upgrade costs | Infrastructure upgrade and relevant allocation; managed charging; vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology; market solutions (e.g., peak use demand charges) | ||

| Martins, 2021 [96] | Portugal | Road transport: passenger cars, public transport vehicles, heavy-duty vehicles, forest machinery; river boats | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; challenges with grid connection; high costs associated with charging infrastructure | Range anxiety | HPEVCS—High-Power Electric Vehicle Charging Station offered by authors |

| Sridhar et al., 2022 [148] | USA | Road transport: passenger cars, with future applications in medium and heavy-duty vehicles | Operational limits of electrical grids; inefficient distribution of charging stations | Forecasting future EV trends and planning infrastructure accordingly; smart charge management | ||

| Umair et al., 2024 [125] | n.d. | Road transport: passenger cars and commercial vehicles | Insufficiently developed charging infrastructure; challenges posed by solar intermittencies and photovoltaic (PV) losses affecting the reliability of solar energy as a charging source; compatibility and energy flow management issues when integrating solar energy, energy storage systems (ESSs), and DC charging | Consideration of renewable energy sources; pair ESS with solar energy for reliable, grid-independent charging; implement MPPT for optimal solar energy harnessing; develop integrated systems combining solar energy, ESS, and efficient charging to promote sustainability and decentralized energy generation | ||

| Rauf et al., 2023 [112] | USA and Australia | Road transport: passenger cars | Limited and insufficiently deployed charging stations; concerns regarding electric grid potential overload; prolonged charging times | Distribution of charging systems in crowded zones and simulation (UrbanEVSim); adoption of residual energy-aware scheduling algorithms to minimize failure rates and optimize charging station occupancy rates; consideration of renewable energy sources | ||

| Patil et al., 2023 [97] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars and commercial vehicles | Capacity limits: range | Risks associated with electric grid load; challenges in charging infrastructure design and deployment; high implementation costs | Range anxiety | Demand (behavioral data)-based distribution of charging infrastructure; managed charging; residential charging |

| Tarar et al., 2023 [98] | Developing countries | Road transport: primarily for passenger cars | Charging infrastructure implementation costs; weaknesses in grid infrastructure | EV purchasing cost | Battery swapping; developing tailored state-of-charge (SOC) strategies | |

| Palomino and Parvania, 2024 [113] | USA | Road transport: passenger cars, public transport (buses) | Insufficiently developed and deployed charging infrastructure; risks associated with grid overloading | Range anxiety | Novel strategies and collaboration among stakeholders; time-of-use strategy for avoiding peak demand | |

| Pamidimukkala et al., 2024 [61] | USA | Road transport: not disclosed | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; recycling issues | Limited charging stations; high installation costs; issues with energy supply; charging times | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery replacement) cost; insufficient support centers and facilities for EV repair and maintenance | Economic incentives (tax reductions, buying subsidies); increased and strategically distributed charging stations; clear policies on parking charges; targeted marketing |

| Dash and Behera, 2019 [149] | India | Road transport: various | Capacity limits: range | Operational challenges due to electrical grid unavailability or unreliability | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Bridging the product cost gap (financial intervention to encourage domestic manufacturing); battery swapping; fast charging; enabling charging infrastructure buildout |

| Rituraj et al., 2022 [99] | Worldwide | Road transport: various | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; high installation costs; standardization issues and compatibility with urban planning; expensive home charging stations; energy grid limitations and upgrade necessity | Seamless charging infrastructure; more attention to off-grid charging systems; use differentiated energy sources; standardize charging connectors; develop high-power charging system prototypes | ||

| Harris et al., 2023 [150] | Worldwide | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Insufficiently developed charging infrastructure; differing interests of stakeholders complicating the implementation of smart charging solutions; charging times; electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; EV purchasing cost | Alternative charging infrastructure: battery swap stations and smart roads; forecasting area development and locating infrastructure accordingly; energy source differentiation; self-charging features of EVs (e.g., photovoltaic panels incorporated into the roof); integration with intelligent transportation systems |

| Nath et al., 2023 [127] | Worldwide | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited charging stations; charging times | EV maintenance cost | Government technical interventions: time-based EV tariffs; focus on fast charging infrastructure; smart charging (V2G); renewable energy integration; facilitation of interoperability; other interventions: mandating EV infrastructure in building bylaws; providing financial support for distribution system upgrades; facilitating land access; creating market support for private investment; promoting awareness about EV benefits |

| Setiawan et al., 2022 [57] | Indonesia | Road transport: passenger cars, trucks, and other vehicles | Capacity limits: range | Electrical grid limitations; power quality issues including voltage stability, current fluctuations, and reactive power characteristics; inadequate charging infrastructure; charging times | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery replacement) cost | Government financial incentives (tax reduction); promoting renewable energy |

| Mamidala and Prajapati, 2024 [100] | India | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; high installation costs | Battery technology improvement; battery swapping; fast charging; smart charging; wireless charging; V2G; grid integration standardization; promoting renewable energy; energy storage; mitigating power quality issues through active and passive filters | |

| Reyasudin et al., 2024 [114] | Malaysia | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; variability in charging demand patterns; optimization needed between transportation and electricity systems | Range anxiety | Reusing electric vehicle batteries as energy storage systems; developing a locally generated, locally used energy model; promoting renewable energy, electric vehicles, and smart houses as part of an eco-island vision; collaboration between stakeholders; offering incentives and subsidies |

| Trinko et al., 2023 [126] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars, commercial vehicles, and business vehicles | Limited charging stations; electrical grid limitations and energy security issues | Uncertainty in charging costs | Charging-as-a-Service (ChaaS), involving a third party mediating between EV users and electricity providers to optimize charging infrastructure design, operation, and management | |

| Wattana and Wattana, 2022 [73] | Thailand | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: lifetime; recycling issues | Limited and insufficiently developed stations; standardization issues | Infrastructure expansion; coordinated charging; time-of-use tariff setting; vehicle-to-everything (V2X) technology in smart grids and renewable energy integration; government intervention to support planning the charging infrastructure | |

| Ali et al., 2021 [101] | Worldwide | Road transport: not specified | Lack of adequate and widespread EV charging stations; high implementation costs; concerns regarding grid reliability | EV purchasing cost | More comprehensive research based on real data; standardizing EV infrastructure, including charging plugs, voltage chargers, safety measures, etc.; following international standards for EV charging and grid integration; implementing smart charging infrastructure; developing efficient connectivity networks; establishing structured charging systems to measure impacts on the power grid; promoting EVs | |

| Pal et al., 2022 [76] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars, public transport (buses), and commercial vehicles (taxis) | Capacity limits: range, energy density; weight | Electrical grid limitations especially during peak times | Range anxiety | Implementing a mix of on-grid, off-grid, and hybrid charging infrastructures; improving battery technology; renewable energy utilization; smart charging (wireless); vehicle-to-grid (V2G); developing smart power management and load management systems to optimize charging processes and minimize grid impacts |

| Meyur et al., 2022 [102] | USA | Road transport: passenger cars | Limited charging stations; high implementation costs; charging times; standardization issues of charging infrastructure interface | Customers’ privacy while working on the users’ data for improvement purposes | Adaptation to specific communities; EV charging scheduling with a distributed optimization framework that protects personal data and increases network reliability in terms of voltages and line loading | |

| Alanazi, 2023 [151] | Worldwide | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Limited charging stations; issues with charging infrastructure implementation; risks associated with electrical grid limitations and overload; cybersecurity risks related to infrastructure connection with different digital systems | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery replacement) cost | Improved battery technology; establishing battery-swapping stations; implementing fast charging stations and diffusing them; use mathematical models to forecast range accuracy and optimize routes; car-sharing; using heat pumps for heating EVs in winter to increase driving range; implementing energy management techniques to regulate energy use; using system configurations that use a traction shaft to clutch the AC compressor motor during braking intervals to reduce energy consumption |

| Das and Bhat, 2022 [115] | India | Road transport: various (personal cars, buses, vans, heavy trucks, small tractors, tractor trucks, rickshaws, car cycles, motorcycles, solar boats) | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; high implementation costs | Range anxiety; EV purchasing and maintenance (battery replacement) cost | Government policies and financial incentives; R&D; development of charging infrastructure and battery manufacturing |

| James et al., 2023 [103] | Australia | Road transport: passenger cars and fleet vehicles | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; high implementation costs | EV purchase and maintenance cost | Consideration of renewable energy sources; managed charging; vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services; incentives to reduce EV purchase and maintenance costs such as electricity bill reductions; customer-demand-based charging price differentiation during peak hours; R&D and collaborative approach |

| Tungom et al., 2023 [152] | Worldwide | Road transport: fleet vehicles | Electrical grid limitations; concerns regarding charging times and peak demands | Range anxiety | Optimize the placement and allocation of charging stations based on factors such as predicted demand, infrastructure costs, driving distance to charging stations, and available space | |

| Banjarey et al., 2021 [116] | India | Road transport: any type | Capacity limits: range, lifetime | Insufficiently deployed stations; charging times | Range anxiety; EV purchase cost and maintenance (battery) cost | Government policy and financial incentives; development of charging infrastructure; renewable energy integration; peak control through mobile apps; battery swapping |

| Paudel et al., 2023 [153] | Thailand | Road transport: passenger cars and other vehicles | Electrical grid limitations; lack of fast charging infrastructure | Development of home, office, and public charging stations; improving charging technology (fast charging); battery swapping; V2G technology; time-of-use pricing and real-time tariffs | ||

| Afshar et al., 2022 [104] | USA | Road transport: not specified | Limited charging stations and absence of related equipment; challenges with infrastructure installation costs; charging times | Range anxiety | Customer demand data-based diffusion of charging infrastructure; managed charging; multi-charger framework with V2G | |

| Mouhy-Ud-Din et al., 2024 [58] | Pakistan | Road transport: passenger cars | Scarce charging stations | Implementing peak time charging rates; fast charging stations; public charging | ||

| Stamatescu et al., 2020 [105] | Romania | Road transport: passenger cars | Capacity limits: range, energy storage, lifetime | Absence of charging infrastructure in parks; high implementation costs; issues with energy supply | Battery price | Development of an optimization model for Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE) deployment in urban areas; optimizing the placement of charging stations; customer demand data-based decisions |

| Venkateswaran et al., 2022 [154] | India | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: lifetime | Charging times; electrical grid limitations; absence of maintenance services | EV adoption and maintenance (battery) cost | Battery swapping technology |

| Templeton et al., 2023 [106] | USA | Road transport: fleet cars (US national parks) | Scarce charging stations; high infrastructure implementation costs; electrical grid limitations, and stability issues; charging times | Government interventions to support increasing battery range and dense public charging infrastructure; R&D and collaborative approach | ||

| Javadnejad et al., 2023 [86] | USA | Road transport: not specified | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; Safety issues | Electrical grid limitations and stability issues | Range anxiety; EV purchase cost and maintenance (battery, electricity) cost | Government intervention for battery warranty, lease, and exchange programs; dense charging station networks; financial incentives; battery advancements—increased range, lifetime, density, and recycling; residential charging |

| Wang et al., 2021 [123] | Singapure | Road transport: primarily passenger cars | Capacity limits: range, energy storage | Inadequate charging infrastructure; lack of standardization of charging outlets | Battery price | Optimizing the locations of charging stations; managed charging; real-time pricing; V2G; integrating renewable energy sources; developing policies promoting EV adoption and installation of charging stations; enhancing grid-connected battery deployment; R&D |

| Kumar et al., 2023 [124] | Worldwide | Road transport: not disclosed | Standardization issues with charging infrastructure; electrical grid limitations | MINLP framework for optimal placement and sizing of fast chargers; consideration of renewable energy sources; V2G; managed charging; implementing battery energy storage systems (BESSs) for peaks | ||

| Li et al., 2023 [155] | Worldwide | Road transport: passenger cars and other vehicles | Electrical grid limitations; concerns regarding energy anxiety; charging times | Flexible distributed energy storage for peak shaving; voltage and frequency regulation; renewable energy integration; smart/managed charging | ||

| Behl et al., 2019 [117] | USA | Road transport: not specified | Limited and insufficiently deployed stations; standardization issues; charging times | Range anxiety | Introducing an autonomous robot electric vehicle charger, which can navigate parking lots, locate EVs, and charge them while the driver is away | |

| Mohammadi et al., 2023 [107] | Worldwide | Road transport: various | Electrical grid limitations; high costs associated with grid upgrade and connection; concerns regarding EV uptake speed and investment risks | Range anxiety | Smart charging and V2G; integration of renewable energy; optimal placement of charging infrastructure; financial incentives | |

| Gopinathan and Shanmugam, 2022 [87] | India | Road transport: passenger cars and other vehicles | Capacity limits: range, lifetime; battery safety issues; recycling issues | Insufficiently developed and deployed charging infrastructure; electrical grid limitations | Range anxiety; battery cost | Decentralized Distributed Generation (DDG) sources allowing renewable energy usage; V2G; smart charging; battery swapping; government financial incentives |