Abstract

Countries have turned to developing renewable energy production, avoiding the risks posed by the disruptions in global energy trade, the high volatility in energy prices, and the remarkable environmental impairment. Numerous economic, environmental, institutional, and social factors have been put forward as driving factors toward renewable energy. The goal of this research article is to study the causal nexus among energy dependency, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy of the 27 EU members between 2000 and 2020 through Emirmahmutoglu and Kose causality test. The results of the panel-level causality tests demonstrate feedback interplay among energy dependency, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy use. However, the results of the country-level causality analysis unveil that the interplay among renewable energy utilization, energy dependency, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and human capital remarkably varies among EU members. The results of this study suggest that renewable energy investments are significant instruments to make progress in energy security, human capital, real GDP per capita, and CO2 emissions. Furthermore, energy security, human capital, real GDP per capita, and CO2 emissions are significant drivers of renewable energy development.

1. Introduction

Energy is one of the essential inputs of all economic and non-economic activities. Therefore, energy security, which is commonly defined as the uninterrupted and continuous access to energy by a country [1], is required for a country to maintain its economic and social development. In this context, the shares of non-renewable energy use and renewable energy use of global energy consumption in 2023 were, respectively, 81.5% and 14.6% [2]. That is, non-renewables continue to dominate the global energy markets.

However, instability and conflicts in the regions with concentrated fossil energy reserves, such as instability in the Middle East and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, negatively impact energy markets and energy trade. Furthermore, energy use accounts for more than three-quarters of the total greenhouse gas emissions in the world [3]. Concerns related to energy security and the environment have directed countries to improve their renewable energy production with low-carbon emissions. However, the effects of renewable energy on economic growth can be different depending on the higher costs of renewable investments, higher energy security, and lower greenhouse gas emissions [4].

Given the positive economic and environmental implications of renewable energy use, the drivers of renewable energy production and use have been explored extensively in the relevant literature, and numerous institutional, economic, environmental, technological, and social factors have been set forth as the drivers of renewable energy utilization, as outlined in Table 1. But the related recent literature has mainly focused on the nexus among income, environmental factors, and renewable energy. For this reason, we intend to analyze the bilateral nexus among energy dependence, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy utilization in this research.

Table 1.

The recent literature on the determinants of renewable energy.

An empirical analysis is performed on a sample of European Union (EU) members, because the EU is already heavily dependent on the import of fossil fuels. The import dependency rate was 63% in 2022, but energy dependency changes remarkably among EU members [16]. Furthermore, the share of renewables of the total energy use was 18%, but this also considerably differs among EU states [16]. Therefore, increasing the renewable energy capacity is one of the main principles of the EU’s energy policy to address energy import dependency and environmental sustainability [17].

Energy dependency is expected to impact the development of renewable energy and increase energy security. On the other hand, increases in renewable energy utilization are anticipated to decrease energy dependency. Consequently, a bilateral nexus between energy dependency and renewable energy is theoretically expected.

Human capital can also affect the development of renewable energy through diverse channels. First, human capital is one of the essential factors underlying the development of renewable energy technologies; a higher human capital level makes renewable energy technologies more affordable and increases energy accessibility by reducing costs [18]. Secondly, a higher level of human capital development usually leads to higher environmental awareness and, in turn, preference for energy sources with low-carbon emissions, such as renewable energies [19]. The utilization of renewable resources increases environmental quality and improves the health of human capital [20]. Furthermore, the utilization of renewable energy can impact human capital through improvements in living standards and education, resulting from increases in economic growth and development [21]. Consequently, a bilateral nexus between renewable energy use and human capital is anticipated in theory.

The nexus between real GDP per capita and renewable energy has remained inconclusive. On the one hand, increases in real GDP per capita enable countries to finance the development of renewable energies [22]. On the other hand, improvements in renewable energy development can foster real GDP per capita via economic growth [23]. In conclusion, a two-way causal nexus between real GDP per capita and renewable energy utilization seems possible in light of these theoretical considerations. Lastly, the utilization of renewable energy with low-carbon emissions can decrease total carbon emissions [24]. Therefore, higher levels of carbon emissions may encourage countries to develop their renewable energy capacity.

This research article aims to substantiate the existing empirical literature from three perspectives. In the relevant literature, Gökgöz and Güvercin [25], Liu et al. [26], Azzuni et al. [27], Rios-Ocampo et al. [28], Carfora et al. [29], and Ürkmez and Okyar [30] examined the impact of renewable energy on energy dependency. Conversely, Chu et al. [31] and Chu [32] investigated the correlation between energy security and renewable energy utilization. Only Cergibozan [33] and Erdemir [34] delved into the mutual interaction between energy dependence and renewable energy. Therefore, this study represents one of the initial empirical papers exploring the bilateral relationship between energy dependency and renewable energy, distinct from the aforementioned literature. Secondly, scholars have predominantly focused on the influence of human development or human capital on total energy and renewable energy, neglecting the impact of renewable energy utilization on human capital. In this context, only Jamshid et al. [35], Fatima et al. [36], and Sasmaz et al. [37] investigated the reciprocal relationship between renewable energy and human capital, while Alvarado et al. [38] and Fang et al. [39] scrutinized the causal connection among total energy, non-renewable energy, and human capital. As such, the secondary contribution of this article is to conduct a dual analysis between renewable energy utilization and human capital concerning the implications of renewable energy advancement on human capital. Lastly, this research adds to the inconclusive literature on the relationship between renewable energy and real GDP per capita.

In the subsequent sections of this article, the related empirical studies are reviewed in Section 2. Section 3 provides a brief explanation of the methodology approach and dataset. Section 4 presents the econometric tests and discussions on the results of the causality test, and Section 5 outlines the conclusions and policy suggestions.

2. Literature Review

The environmental and energy security issues stemming from instability and conflicts in regions abundant in oil, coal, and natural gas have prompted nations to enhance the integration of renewable energy sources in their overall energy consumption. Consequently, a considerable body of literature has delved into the factors driving the production and adoption of renewable energy. Various institutional, economic, environmental, technological, and social elements have been identified as key drivers of renewable energy deployment.

This study explores the bilateral relationship among renewable energy utilization, energy dependency, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and human capital in a sample of EU members, given the limited literature and high import energy dependence in the EU region. Only Cergibozan [33] and Erdemir [34] conducted a bilateral causal analysis between renewable energy and energy dependence. Cergibozan [33] examined the impact of energy security in 23 OECD economies from 1985 to 2016 using the Durbin–Hausman cointegration test and Dumitrescu–Hurlin panel causality test. The findings revealed that total renewable energy, wind, and hydroelectric power reduced energy security risk, while solar and biomass energy sources had no significant impact on energy security. Additionally, the results of the causality test showed a one-way causal relationship from hydroelectricity and biomass to energy security risk and a two-way causal relationship between wind and energy security risk.

Erdemir [34] conducted a study examining the impact of non-renewable and renewable energy sources, as well as GDP, on energy imports in Turkey from 1990 to 2018. The study utilized the Toda-Yamamoto causality test and quantile regression analysis. The findings revealed a mutual causal relationship between energy imports and renewable energy sources, with a positive influence of renewable energy production on reducing net energy imports.

On the other hand, Chu et al. [31] and Chu [32] conducted research on the impact of energy security on the utilization of renewable energy. Chu et al. [31] examined the influence of energy security risks and economic complexity on renewable energy in the top 23 energy consumers from 1997 to 2017, utilizing cointegration tests and quantile regression. Their findings revealed that energy security risks had a positive impact on renewable energy production, although this relationship was found to be unstable for middle-income economies. Chu [32] investigated the relationship between energy security and renewable energy in G7 economies from 1980 to 2017 using quantile regression analysis. The results indicated that energy insecurity served as a catalyst for the adoption of renewable energy sources.

Gökgöz and Güvercin [25], Liu et al. [26], Azzuni et al. [27], Rios-Ocampo et al. [28], Carfora et al. [29], and Ürkmez and Okyar [30] conducted studies analyzing the impact of renewable energy on energy security. Gökgöz and Güvercin [25] specifically investigated the relationship between energy security and renewable energy in 14 EU member states from 2005 to 2014 using data envelopment analysis and the Malmquist–Luenberger productivity index. Their research revealed that investments in renewable energy led to a decrease in energy import dependency and an enhancement in energy security. On the other hand, Liu et al. [26] studied the effects of renewable energy, economic integration, and energy efficiency on energy security using data from 222 energy-importing countries and 218 energy-exporting countries spanning the years 1995 to 2016. Utilizing a gravity model, their findings highlighted the significance of renewable energy and energy efficiency in enhancing energy security.

Azzuni et al. [27] investigated the impact of transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable sources on energy security in Jordan. The study proposed that adopting renewable energy would enhance energy security in the country. Rios-Ocampo et al. [28] examined the role of renewable energy sources in reducing energy dependency using a system dynamics model and recommended that greater utilization of renewable energy would strengthen energy security.

Carfora et al. [29] conducted a study on the determinants of energy imports and the impact of renewable energy on energy dependence in 26 EU member countries from 2007 to 2016 using input–output tables. Their findings suggested that renewable energy production has the potential to reduce energy dependence and enhance energy security and sustainable development, particularly in cases where there is a substitution between energy imports and renewable energy sources. Additionally, Ürkmez and Okyar [30] examined the impact of renewable energy on energy dependence in Turkey from 1990 to 2018 using an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) approach. Their research revealed a negative correlation between renewable energy production and energy dependence.

Human capital represents a fundamental input in renewable energy development, and scholarly research extensively examines the relationship between human capital, human development, and the use of renewable and non-renewable energy sources. However, empirical studies have yielded inconclusive results, as illustrated in Table 2. Within this context, Jamshid et al. [35], Fatima et al. [36], and Sasmaz et al. [37] investigated the intricate relationship between human capital and renewable energy. Jamshid et al. [35] and Fatima et al. [36] identified a unidirectional causal link from human capital to the utilization of renewable energy, while Sasmaz et al. [37] revealed a mutual interaction between these two variables. Conversely, Alvarado et al. [38] observed a negligible causal connection between the use of non-renewable energy and human capital, whereas Fang and Wolski [39] recognized a one-way causal link from human capital to energy utilization.

Table 2.

The interaction amongst human development, human capital and renewable energy.

However, the majority of studies have raised questions about the impact of human capital on total/renewable and non-renewable energy. Akram et al. [40], Yao et al. [41], Shahbaz et al. [42], and Pegkas [43] revealed a negative correlation between human capital and total or non-renewable energy consumption, while Hoa and Hoang [44] identified a positive relationship between human capital and non-renewable energy. Wang et al. [45] presented mixed results regarding the connection between human capital and energy usage. Conversely, Yao et al. [41], Shahbaz et al. [42], Pegkas [43], Hoa and Hoang [44], Adepoju et al. [46], Ozcan et al. [47], and Wiredu et al. [48] found a positive impact of human capital on renewable energy, whereas Achuo et al. [49] reported an insignificant relationship between human capital and energy transition. Additionally, Wang et al. [20], Basri et al. [50], Azam et al. [51], and Karimi Alavijeh et al. [52] examined the influence of renewable energy consumption on human development and identified a positive effect of renewable energy on human development.

Various studies examining the relationship between renewable energy and economic growth have presented diverse findings, supporting theories, such as the growth hypothesis (Tang et al. [53]), conservative hypothesis (Armeanu et al. [54], Minh and Van [55]), feedback hypothesis (Kahia et al. [56], Gyimah et al. [57], Dilanchiev et al. [58]), and neutrality hypothesis (Maji et al. [59]). Likewise, studies investigating the connection between CO2 emissions and renewable energy have produced mixed results. Furthermore, Dilanchiev et al. [58] identified a unidirectional causality from renewable energy to CO2 emissions, while Saidi and Omri [60] and Hao [61] revealed a feedback relationship between renewable energy and CO2 emissions.

In summary, the existing empirical literature reveals that researchers have primarily focused on analyzing the relationship between renewable energy and energy dependence, as well as the correlation between human capital and renewable energy. However, there has been limited attention given to examining how energy dependence impacts renewable energy and how renewable energy affects human capital. Additionally, despite numerous studies on the subject, the causal relationship between real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy remains inconclusive. This study aims to investigate the mutual causal relationships among energy dependence, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy through causality testing. Building on the literature review, this research article establishes the following research hypotheses:

H1.

A bilateral causal interplay between renewable energy utilization and energy dependency exists.

H2.

A bilateral causal interplay between renewable energy and human capital exists.

H3.

A bilateral causal interplay between renewable energy and real GDP per capita exists.

H4.

A bilateral causal interplay between renewable energy and CO2 emissions exists.

3. Data and Methods

This study examines the causal relationship among energy dependency, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy in EU member states from 2000 to 2020. Emirmahmutoglu and Kose’s causality test is employed to determine the presence of causal direction (CD) and heterogeneity in the panel dataset. The variables used in the econometric analysis are displayed in Table 3. In this context, renewable energy (RENENG) is defined as the percentage of total energy use derived from renewable sources, sourced from the World Bank [62] database. Energy dependency (ENGDEP) is calculated as follows:

Energy dependence = (imports–exports)/gross available energy

Table 3.

Definition of the dataset.

The data were sourced from the Eurostat database [63]. A positive dependency rate indicates a net energy importer, and a dependency rate exceeding 100% suggests that energy products have been stored. The human capital index, a subcomponent of the productive capacities index calculated by UNCTADSTAT [64], serves as a proxy for human capital (HUMCAP), reflecting the education, skills, and health levels of individuals in society, as well as expenditures on research activities and the number of researchers. Real GDP per capita is approximated by GDP per capita based on constant 2015 USD (United States dollars), while CO2 emissions are measured in metric tons per capita and sourced from the World Bank [65] and Climate Watch [66], respectively.

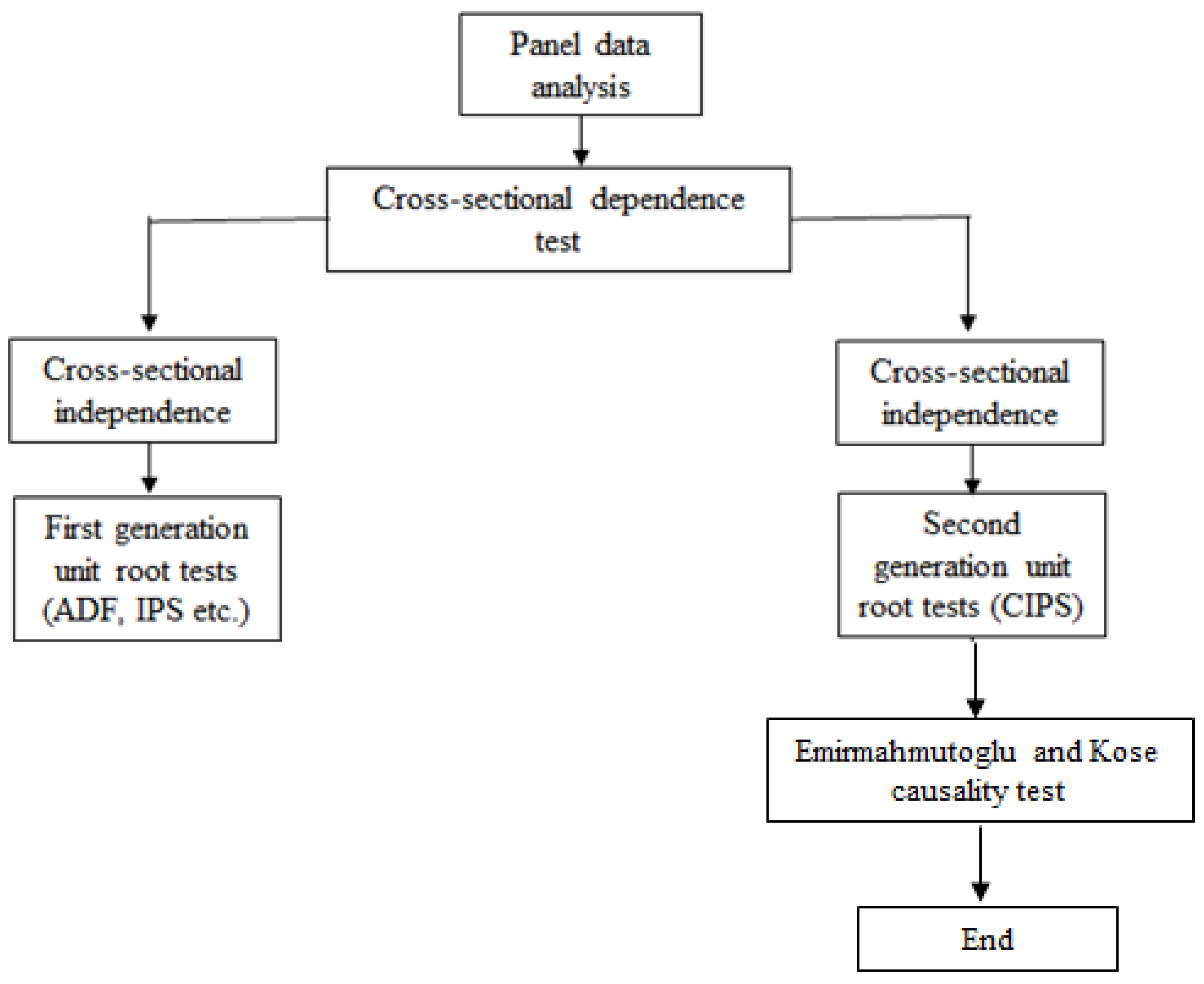

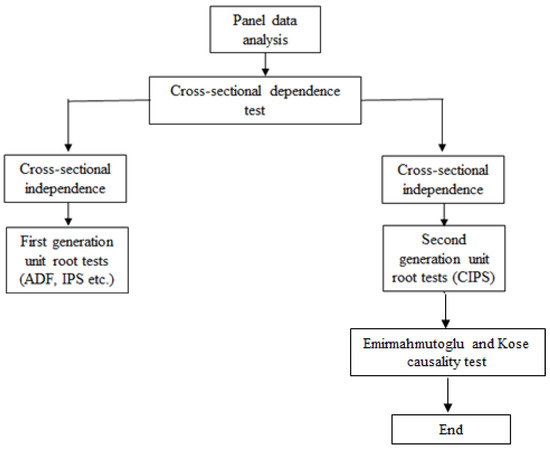

The empirical analysis encompasses 27 EU member states over the period 2000–2020. The human capital index has been annually calculated by UNCTADSTAT since 2000, with the latest data available for annual energy dependence and renewable energy up to 2020. Therefore, the empirical analysis is conducted for the period 2000–2020. The econometric analyses are undertaken utilizing Stata 16.0 and EViews 12.0. The methodological approach is illustrated in Chart 1, involving CD and heterogeneity tests initially, followed by unit root and causality tests in accordance with the preceding results.

Chart 1.

Methodological approach of the study.

Emirmahmutoglu and Kose [67] developed a causality test that is a modified panel version of the Toda-Yamamoto [68] causality test, accounting for cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The estimated VAR model for each cross-section is as follows:

where yit is endogenous variable vector, δi is fixed effects vector with p dimensions, pi is the optimal length, and di is the maximum integration level of the variables under consideration [67]. Furthermore, the causality test allows for the lag length to vary across different cross-sections, thereby minimizing long-term information loss resulting from modeling the series using level values [67].

4. Results and Discussion

In the empirical analysis section, the first heterogeneity and coefficient of determination (CD) of the variables RENENG, ENGDEP, GDP, COEMS, and HUMCAP are analyzed using CD and delta tilde tests. The results of the CD and heterogeneity tests are presented in Table 4. The p-values of the CD tests for LM, LM CD, and LMadj.. are all less than 0.05, leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis of CD independence. Consequently, it can be inferred that there is collinearity among the variables RENENG, ENGDEP, GDP, COEMS, and HUMCAP. Furthermore, the p-values of the delta tilde () and adjusted delta tilde () tests are also less than 0.05, indicating the rejection of the null hypothesis of homogeneity and confirming the presence of heterogeneity. Therefore, incorporating a causality test that considers both CD and heterogeneity would enhance the robustness of the results.

Table 4.

Consequences of CD and heterogeneity tests.

The Pesaran [69] CIPS unit root test is utilized to analyze the stationarity of ENGDEP, HUMCAP, GPD, COEMS, and RENENG by virtue of CD, and the consequences of the CIPS unit root test are demonstrated in Table 5 and show us that RENENG, ENGDEP, GDP, COEMS, and HUMCAP are I(1). In other words, these series include unit root at their levels but become stationary at taking their first-differenced values.

Table 5.

Consequences of CIPS test.

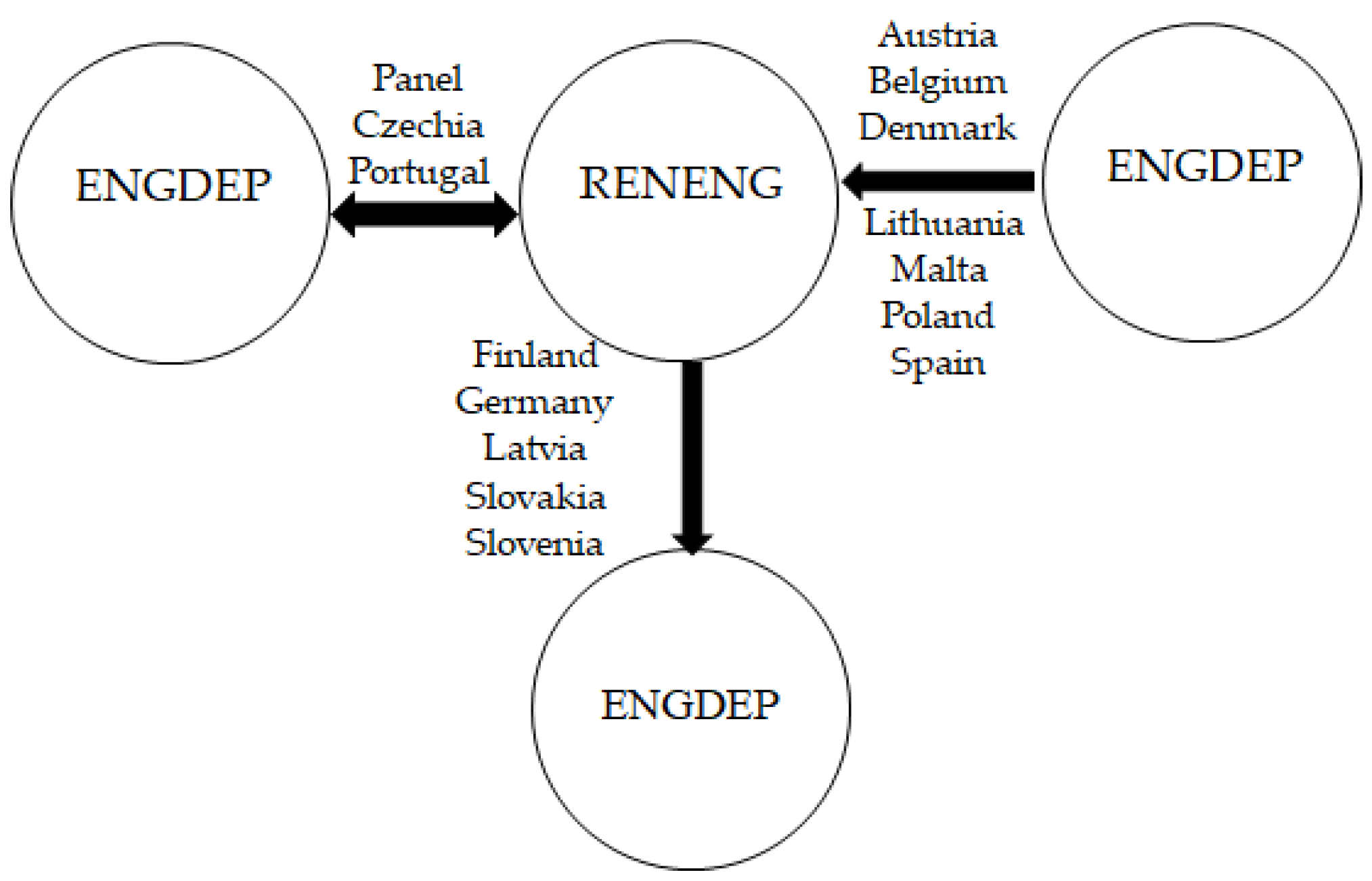

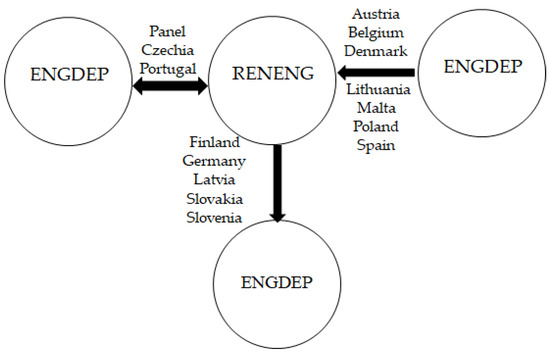

The study conducted by Emirmahmutoglu and Kose [67] examined the causal relationships among energy dependency, human capital, GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy use using the causality test. The analysis takes into account the presence of cross-sectional dependence (CD) and heterogeneity among the variables ENGDEP, HUMANCAP, GDP, COEMS, and RENENG. The results of the causality test are presented in Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9. The panel-level causality analysis between ENGDEP and RENENG in Table 6 and Chart 2 reveals a bilateral causal relationship between the two variables. However, the country-level causality analysis shows bilateral causality in Czechia and Portugal; a unilateral causal relationship from ENGDEP to RENENG in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, and Spain; and a unilateral causal relationship from RENENG to ENGDEP in Finland, Germany, Latvia, Slovakia, and Slovenia.

Table 6.

Consequences of causality test between ENGDEP and RENENG.

Table 7.

Consequences of causality test between HUMCAP and RENENG.

Table 8.

Consequences of causality test between GDP and RENENG.

Table 9.

Consequences of causality test between COEMS and RENENG.

Chart 2.

Consequences of causality between ENGDEP and RENENG.

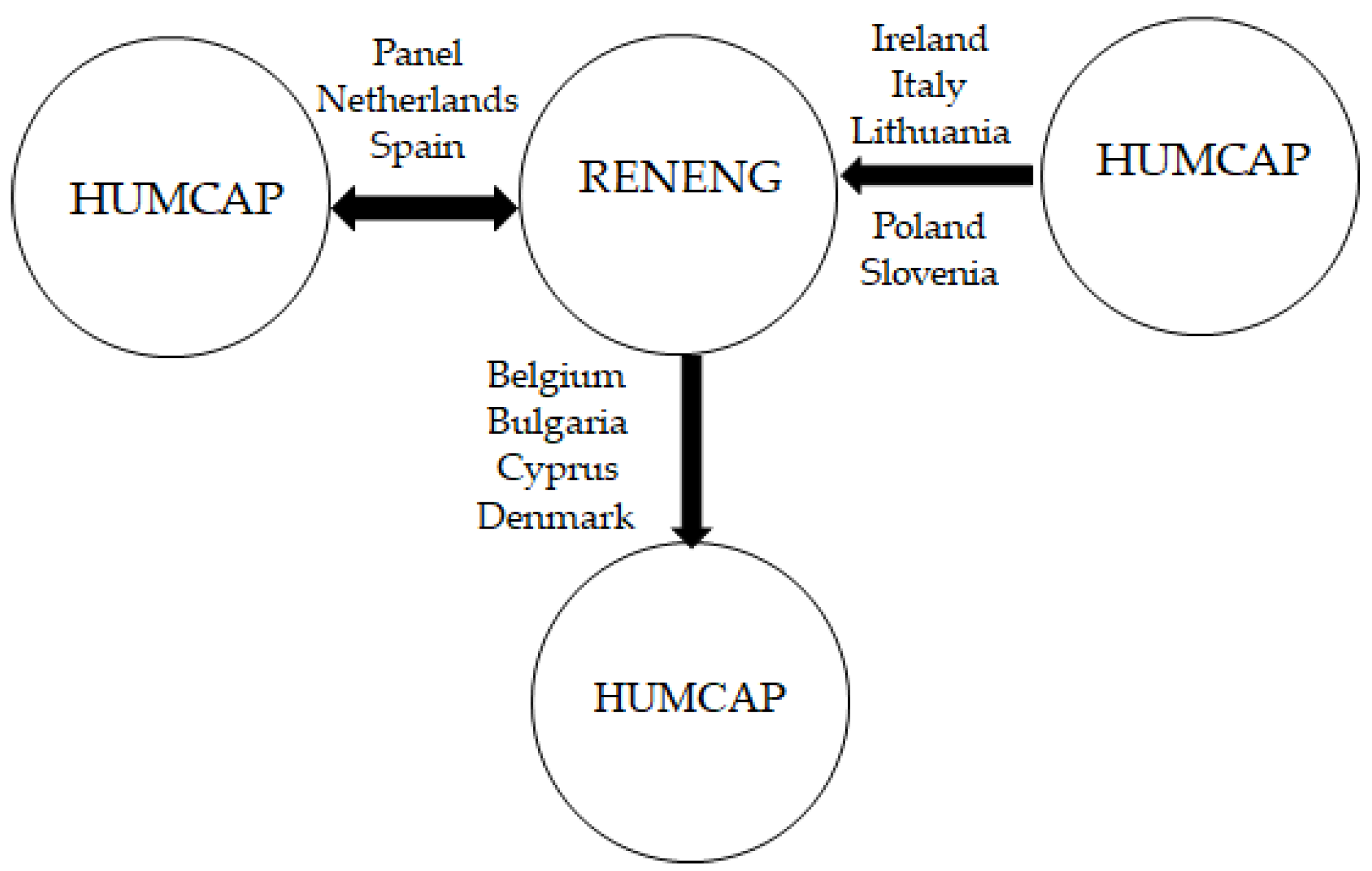

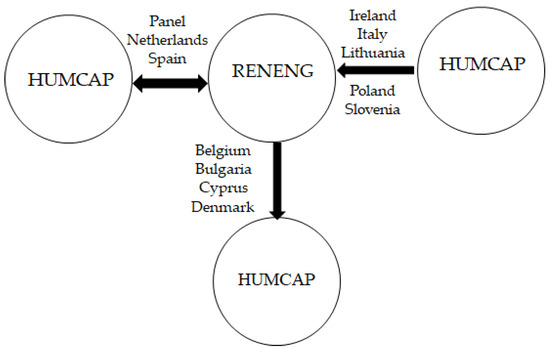

The panel-level causality analysis conducted on the relationship between HUMCAP and RENENG, as presented in Table 7 and Chart 3, reveals a bilateral causal connection between the two variables. However, the results of country-level causality analysis suggest a bilateral causality in the Netherlands and Spain; a unidirectional causal link from HUMCAP to RENENG in Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovenia; and a unidirectional causal link from RENENG to HUMCAP in Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, and Denmark.

Chart 3.

Consequences of causality between HUMCAP and RENENG.

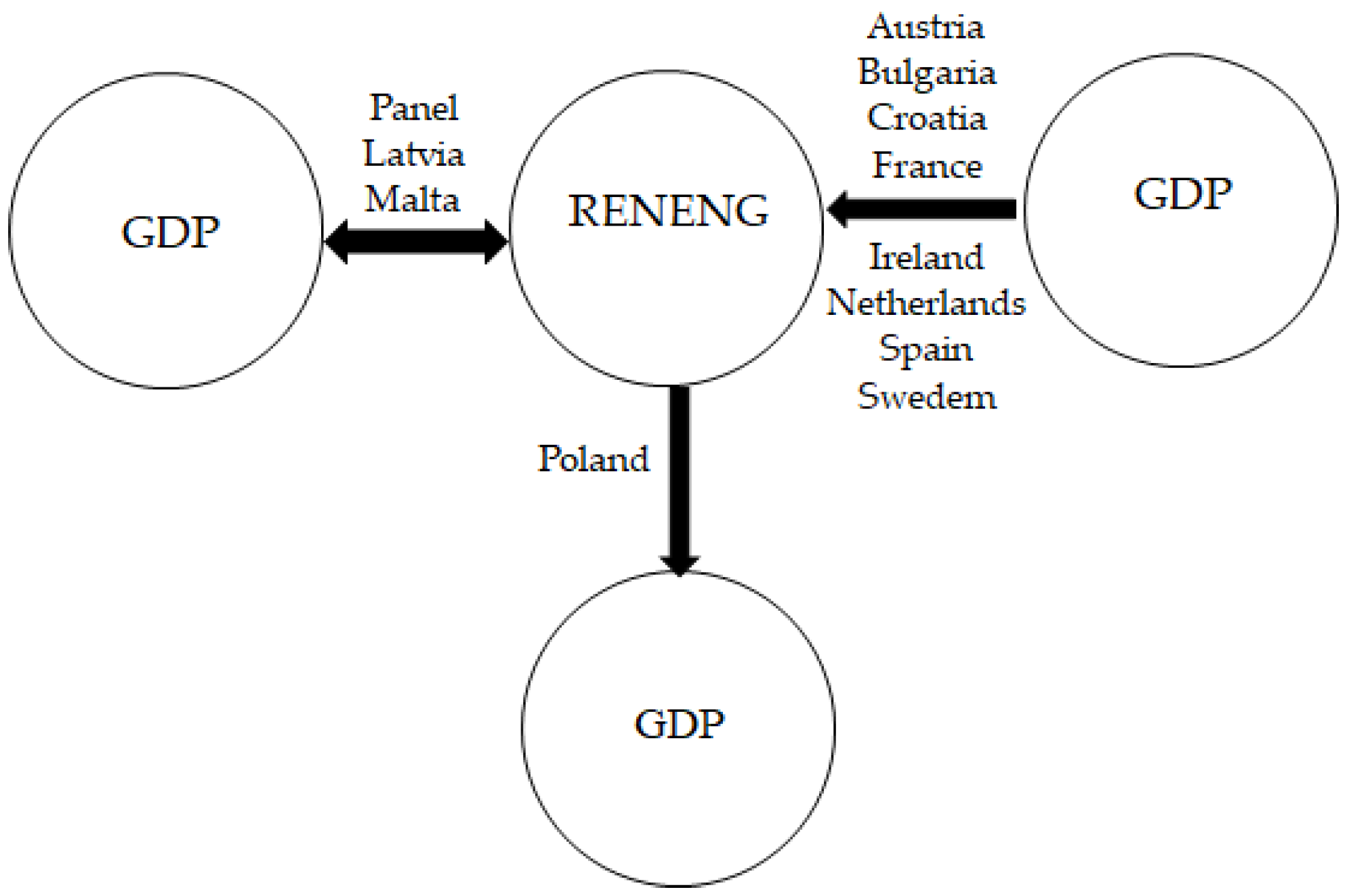

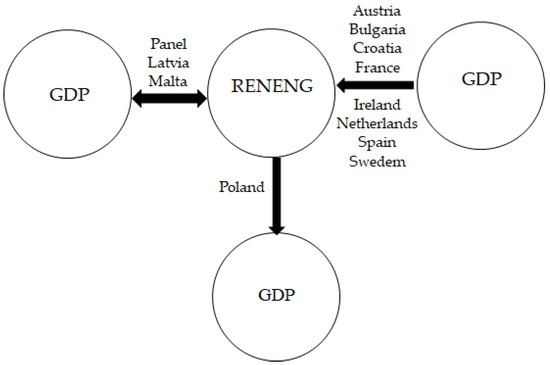

The panel-level causality analysis between GDP and RENENG in Table 8 and Chart 4 shows a bilateral causal relationship between GDP and RENENG. However, the results of the country-level causality analysis indicate a bilateral causality in Latvia and Malta; a unidirectional causal relationship from GDP to RENENG in Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden; and a unidirectional causal relationship from RENENG to GDP in Poland.

Chart 4.

Consequences of causality between GDP and RENENG.

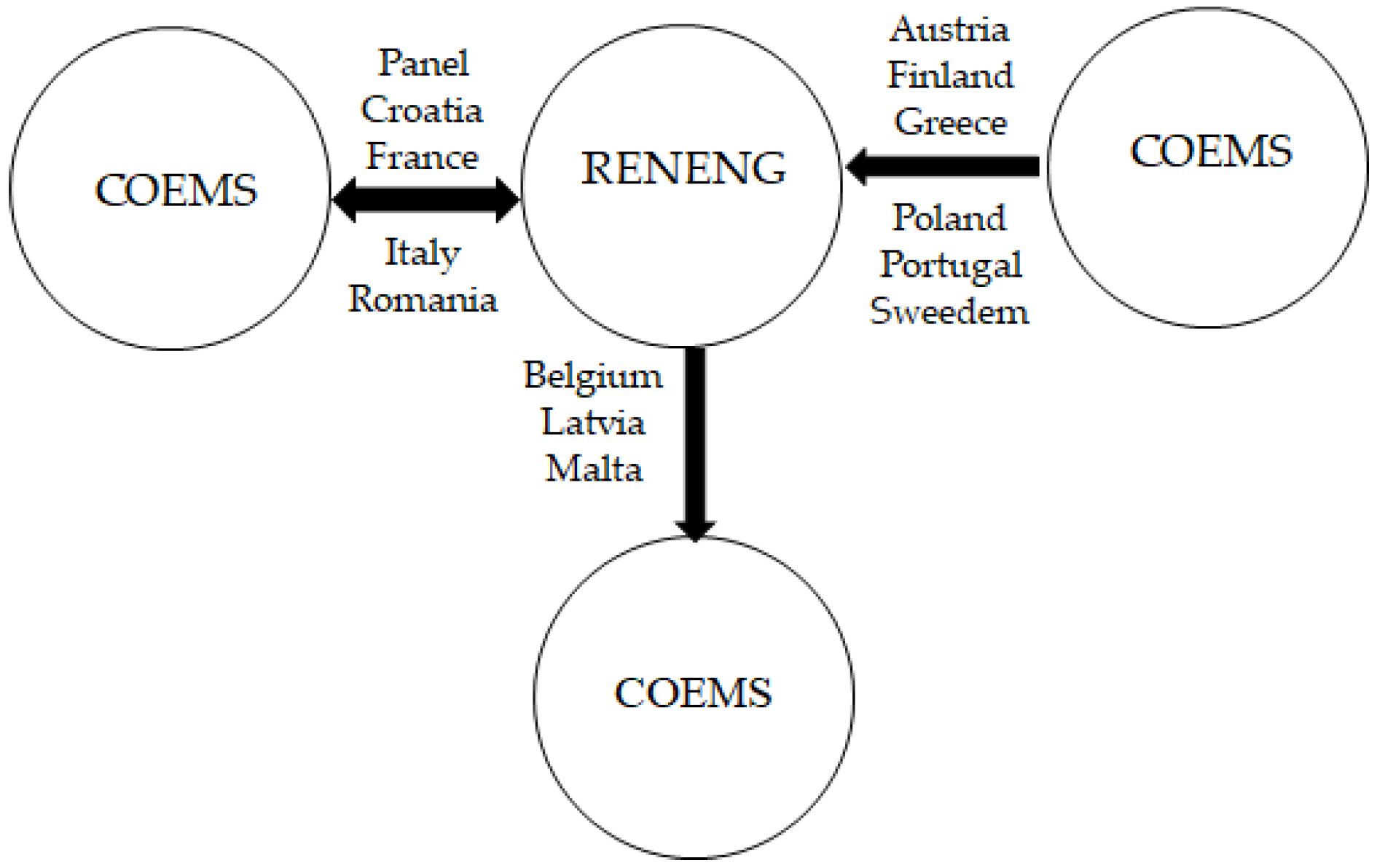

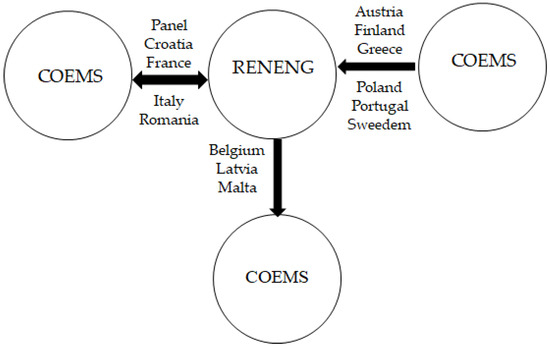

The panel-level causality analysis presented in Table 9 and Chart 5 reveals a reciprocal causal relationship between COEMS and RENENG. Moreover, the results of the country-level causality analysis suggest a mutual causal connection in Croatia, France, Italy, and Romania. Additionally, there is a unidirectional causal link from COEMS to RENENG in Austria, Finland, Greece, Poland, Portugal, and Sweden, as well as a unidirectional causal link from RENENG to COEMS in Belgium, Latvia, and Malta.

Chart 5.

Consequences of causality between COEMS and RENENG.

Numerous economic, environmental, institutional, and technological factors have been proposed as key drivers of renewable energy development. This study examines the causal relationships among energy dependency, human capital, real GDP, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy, aiming to address a gap in the existing empirical literature.

The significant rise in energy insecurity among countries with high energy dependency is primarily due to the volatile nature of energy markets and trade. This trend is expected to drive these nations towards investing in renewable energy development to reduce their dependency. Increasing renewable energy capacity is projected to lessen this dependency. However, the current energy dependence levels and development status of countries will play a crucial role in determining the relationship between energy dependence and the utilization of renewable energy. The existing literature, as highlighted by Cergibozan [33] for OECD members and Erdemir [34] for Turkiye, demonstrates a causal connection between certain renewable energy sources and energy security. Our findings align with these theoretical considerations and empirical results, emphasizing the intricate relationship between energy dependence and the adoption of renewable energy sources.

The interaction between renewable energy and human capital can manifest in various ways. Human capital is a crucial factor in renewable energy production and can enhance access to renewable energy sources. Additionally, regions with higher levels of human capital tend to favor renewable energy options with lower carbon footprints. Conversely, renewable energy can impact human capital through improvements in environmental quality, economic growth, and overall development. The relationship between renewable energy and human capital can vary depending on country-specific economic and social conditions. Studies by Jamshid et al. [35], Fatima et al. [36], and Sasmaz et al. [37] provide evidence supporting these theoretical assertions. Sasmaz et al. [37] identified a mutual relationship between renewable energy and human development, while Jamshid et al. [35] and Fatima et al. [36] highlighted a one-way causal link from human capital to the adoption of renewable energy. In conclusion, our findings align closely with these theoretical frameworks and empirical findings.

The relationship among real GDP, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy has been extensively explored compared to other drivers of renewable energy. Empirical studies have revealed that this relationship significantly varies depending on countries’ development levels in terms of education, infrastructure, and human capital. Kahia et al. [56], Gyimah et al. [57], and Dilanchiev et al. [58] identified a feedback loop between economic growth and renewable energy, while Tang et al. [53], Armeanu et al. [54], Minh and Van [55], and Maji et al. [59] found results supporting the growth hypothesis, conservative hypothesis, and neutrality hypothesis. Our panel-level results confirm the feedback hypothesis, while cross-sectional results support the other hypotheses on the relationship between renewable energy and economic growth. Similarly, the limited existing literature on the relationship between CO2 emissions and renewable energy has revealed diverse outcomes. Saidi and Omri [60] and Hao [61] have reported a feedback loop between renewable energy and CO2 emissions, while Dilanchiev et al. [58] unveiled a unidirectional causality from renewable energy to CO2 emissions. In conclusion, our results align with the findings of these studies.

5. Conclusions

Renewable energy has emerged as a critical tool for environmental protection, energy supply diversification, and reducing dependence on traditional energy sources. It plays a key role in achieving various sustainable development goals, such as promoting affordable and clean energy, improving public health, ensuring access to clean water and sanitation, fostering sustainable urban development, and combating climate change and its effects on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. As a result, many countries are ramping up their efforts to boost renewable energy production. The drivers of renewable energy adoption have been extensively investigated in existing empirical studies. This research article examines the complex relationships among energy dependency, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy in a sample of 27 EU member states with high energy dependency. The study employs causality tests to analyze these relationships while accounting for cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, empirical analyses were conducted for the period 2000–2020 due to a lack of relevant data. Secondly, the causality test allows for a two-way analysis between two variables, providing insight into the direction of their relationship. Lastly, this study did not account for the impacts of external factors other than the variables considered within the specified timeframe.

The outcomes of the panel-level causality test reveal a mutual causality among energy dependence, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy utilization. However, the country-level findings notably vary across EU member states due to specific social and economic characteristics. Our empirical results align closely with relevant theoretical perspectives and prior empirical research.

A notable causal relationship among energy dependence, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy carries substantial policy implications for nations. It is evident that investments in renewable energy play a crucial role in addressing energy dependence, enhancing human capital, boosting real GDP per capita, and improving environmental quality. Conversely, advancements in human capital, real GDP per capita, energy security, and CO2 emissions can stimulate the development of renewable energy sources. This reciprocal relationship between energy dependence, human capital, real GDP per capita, CO2 emissions, and renewable energy is essential for sustainable development. Future research endeavors could delve into exploring the ways in which human capital and renewable energies interact.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; methodology, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; formal analysis, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; data curation, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; writing—review and editing, G.S., H.Ö., M.D., L.A. and Y.B.; supervision, H.Ö and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data utilized in the econometric analyses were obtained from the open access databases Eurostat, UNCTADSTAT, Climate Watch, and World Bank.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Acronyms

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| CD | Cross-sectional dependence |

| CIPS | Cross-sectionally augmented Im-Pesaran-Shin test |

| CS-ARDL | Cross-Sectionally augmented Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| EU | European Union |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| LM | Lagrance Multiplier |

| LM CD | LM Cross-sectional dependence |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| UNCTADSTAT | United Nations Conference on Trade and Development Statistics |

| USD | United States dollar |

References

- Speight, J.G. 10—Energy security and the environment. In Natural Gas, 2nd ed.; Speight, J.G., Ed.; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2019; pp. 361–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Institute. 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy, 73rd ed.; Energy Institute: London, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- IEA Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Energy Data Explorer. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/greenhouse-gas-emissions-from-energy-data-explorer (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Hoa, P.X.; Xuan, V.N.; Thu, N.T.P. Determinants of the Renewable Energy Consumption: The Case of Asian Countries. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayale, N.; Ali, E.; Tchagnao, A.F.; Nakumuryango, A. Determinants of Renewable Energy Production in WAEMU Countries: New Empirical Insights and Policy Implications. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.-X.; Kubatko, O.; Piven, V.; Sotnyk, I.; Kurbatova, T. Determinants of Renewable Energy Development: Evidence from the EU Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Colantonio, E. The Institutional and Socio-technical determinants of Renewable Energy Production in the EU: Implications for Policy. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 2022, 49, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, U.; Agyekum, E.B.; Tariq, S.; Ul Haq, Z.; Uhunamure, S.E.; Edokpayi, J.N.; Azhar, A. Socio-Economic Drivers of Renewable Energy: Empirical Evidence from BRICS. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmassah, S. Determinants of Renewable Energy Production in Emerging and Developed Countries. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024, 18, 1014–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Wang, Y.; Ali, S.; Amin, N.; Kausar, S. Asymmetric Determinants of Renewable Energy Production in Pakistan: Do Economic Development, Environmental Technology, and Financial Development Matter? J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 4097–4114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, M.; Karimi, M.S.; Mamkhezri, J.; Ghazal, R.; Blank, L. Assessing the Impact of Selected Determinants on Renewable Energy Sources in the Electricity Mix: The Case of ASEAN Countries. Energies 2022, 15, 4604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Determinants of Renewable Energy Consumption: Importance of Democratic Institutions. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khribich, A.; Kacem, R.H.; Bazin, D. The Determinants of Renewable Energy Consumption: Which Factors are Most Important? GREDEG Working Papers 2024-08; Groupe de REcherche en Droit, Economie, Université Côte d’Azur: Nice, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chishti, M.Z.; Dogan, E. Analyzing the Determinants of Renewable Energy: The Moderating Role of Technology and Macroeconomic Uncertainty. Energy Environ. 2024, 35, 874–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, S.; Lee, C.C.; Zhou, D. Effects of Trade Openness on Renewable Energy Consumption in OECD Countries: New Insights from Panel Smooth Transition Regression Modelling. Energy Econ. 2021, 104, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Shedding Light on Energy in Europe—2024 Edition. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/interactive-publications/energy-2024 (accessed on 26 June 2024).

- European Commission Energy Union. 2024. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/energy-union_en (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Shabani, Z.D. Renewable Energy and CO2 Emissions: Does Human Capital Matter? Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 3474–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibanda, K.; Gonese, D.; Garidzirai, R. Human Capital and Environmental Sustainability Nexus in Selected SADC Countries. Resources 2023, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Phan, G.Q.; Tran, T.K.; Bu, H.M. The Role of Renewable Energy Technologies in Enhancing Human Development: Empirical Evidence from selected Countries. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bui, Q.; Zhang, B.; Nawarathna, C.L.K.; Mombeuil, C. The Nexus between Renewable Energy Consumption and Human Development in BRICS Countries: The Moderating Role of Public Debt. Renew. Energy 2021, 165, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A.; Manso, J.P. Motivations Driving Renewable Energy in European Countries: A Panel Data Approach. Energy Pol. 2010, 38, 6877–6885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotourehchi, Z. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth: A Case Study for Developing Countries. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2017, 7, 61–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Pinar, M.; Stengos, T. Renewable energy and CO2 emissions: New evidence with the panel threshold model. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökgöz, F.; Güvercin, M.T. Energy Security and Renewable Energy Efficiency in EU. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 96, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, Z.; Azhgaliyeva, D. Toward Energy Security in ASEAN: Impacts of Regional Integration, Renewables, and Energy Efficiency; ADBI Working Paper 1041; Asian Development Bank Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2019; Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/toward-energy-security-asean (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Azzuni, A.; Aghahosseini, A.; Ram, M.; Bogdanov, D.; Caldera, U.; Breyer, C. Energy Security Analysis for a 100% Renewable Energy Transition in Jordan by 2050. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Ocampo, J.P.; Arango-Aramburo, S.; Larsen, E.R. Renewable Energy Penetration and Energy Security in Electricity Markets. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 17767–17783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carfora, A.; Pansini, R.V.; Scandurra, G. Energy Dependence, Renewable Energy Generation and Import Demand: Are EU Countries Resilient? Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urkmez, I.; Okyar, M.C. The Effect of Renewable Energy on Energy Import Dependence: An Empirical Analysis in Turkey. SİYASAL J. Political Sci. 2022, 31, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K.; Ghosh, S.; Doğan, B.; Nguyen, N.H. Energy Security as New Determinant of Renewable Energy: The Role of Economic Complexity in Top Energy Users. Energy 2023, 263, 125799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, L.K. The Role of Energy Security and Economic Complexity in Renewable Energy Development: Evidence from G7 Countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 56073–56093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cergibozan, R. Renewable Energy Sources as a Solution for Energy Security Risk: Empirical Evidence from OECD Countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, N.A. Energy Dependence of Turkey: The Role of Renewable Energy Sources. Başkent Üniv. Ticari Bilim. Fak. Derg. 2022, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshid, J.; Villanthenkodath, M.A.; Velan, N. Can Educational Attainment Promote Renewable Energy Consumption? Evidence from Heterogeneous Panel Models. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2022, 16, 1017–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, N.; Li, Y.; Ahmad, M.; Jabeen, G.; Li, X. Analyzing Long-term Empirical Interactions between Renewable Energy Generation, Energy Use, Human Capital, and Economic Performance in Pakistan. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2019, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmaz, M.U.; Sakar, E.; Yayla, Y.E.; Akkucuk, U. The Relationship between Renewable Energy and Human Development in OECD Countries: A Panel Data Analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, R.; Deng, Q.; Tillaguango, B.; Méndez, P.; Bravo, D.; Chamba, J.; Ahmad, M. Do Economic Development and Human Capital Decrease Non-renewable Energy Consumption? Evidence for OECD Countries. Energy 2021, 215, 119147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Wolski, M. Human Capital, Energy and Economic Growth in China: Evidence from Multivariate Nonlinear Granger Causality Tests. Empir. Econ. 2021, 60, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, V.; Jangam, B.P.; Rath, B.N. Does Human Capital Matter for Reduction in Energy Consumption in India? Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2018, 13, 359–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ivanovski, K.; Inekwe, J.; Smyth, R. Human Capital and Energy Consumption: Evidence from OECD Countries. Energy Econ. 2019, 84, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Song, M.; Ahmad, S.; Vo, X.V. Does Economic Growth Stimulate Energy Consumption? The Role of Human Capital and R&D Expenditures in China. Energy Econ. 2022, 105, 105662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pegkas, P. Energy Consumption and Human Capital: Does Human Capital Stimulate Renewable Energy? The Case of Greece. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, L.T.H.; Hoang, P.V.H. The Impact of Human Capital on Energy Consumption in Vietnam. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Cai, X. The effect of human capital on energy consumption: Evidence from an extended version of STIRPAT framework. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 20, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, O.O.; David, L.O.; Nwulu, N.I. Analysing the Impact of Human Capital on Renewable Energy Penetration: A Bibliometric Reviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, B.; Danish Temiz, M. An Empirical Investigation between Renewable Energy Consumption, Globalization and Human Capital: A dynamic Auto-Regressive Distributive Lag Simulation. Renew. Energy 2022, 193, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiredu, J.; Yang, Q.; Inuwa, U.L.; Sampene, A.K. Energy Transition in Africa: The Role of Human Capital, Financial Development, Economic Development, and Carbon Emissions. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 146, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achuo, E.; Kakeu, P.; Asongu, S. Financial Development, Human Capital and Energy Transition: A Global Comparative Analysis. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manag. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basri, R.; Ferdous, J.; Ali, M.R.; Basri, R. Renewable energy use, real GDP, and human development index in Bangladesh: Evidence from simultaneous equation model. Int. J. Manag. Econ. Invent. 2021, 7, 2239–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Khan, F.; Ozturk, I.; Noor, S.; Yien, L.C.; Bah, M.M. Effects of Renewable Energy Consumption on Human Development: Empirical Evidence from Asian Countries. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Alavijeh, N.; Ahmadi Shadmehri, M.T.; Esmaeili, P.; Dehdar, F. Asymmetric Impacts of Renewable Energy on Human Development: Exploring the Role of Carbon Emissions, Economic Growth, and Urbanization in European Union Countries. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, B.W.; Ozturk, I. Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in Vietnam. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1506–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armeanu, D.Ş.; Vintilă, G.; Gherghina, Ş.C. Does renewable energy drive sustainable economic growth? Multivariate panel data evidence for EU-28 countries. Energies 2017, 10, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.B.; Van, H.B. Evaluating the Relationship between Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth in Vietnam, 1995–2019. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahia, M.; Aïssa, M.S.B.; Lanouar, C. Renewable and Non-Renewable Energy Use—Economic Growth Nexus: The Case of MENA Net Oil Importing Countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, J.; Yao, X.; Tachega, M.A.; Sam Hayford, I.S.S.; Opoku-Mensah, E. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth: New Evidence from Ghana. Energy 2022, 248, 123559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilanchiev, A.; Umair, M.; Haroon, M. How Causality Impacts the Renewable Energy, Carbon Emissions, and Economic Growth Nexus in the South Caucasus Countries? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 33069–33085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maji, I.K.; Sulaiman, C.; Abdul-Rahim, A.S. Renewable Energy Consumption and Economic Growth Nexus: A Fresh Evidence from West Africa. Energy Rep. 2019, 5, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, K.; Omri, A. The Impact of Renewable Energy on Carbon Emissions and Economic Growth in 15 Major Renewable Energy-Consuming Countries. Environ. Res. 2020, 186, 109567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y. The Relationship between Renewable Energy Consumption, Carbon Emissions, Output, and Export in Industrial and Agricultural Sectors: Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 63081–63098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Renewable Energy Consumption (% of Total Final Energy Consumption). 2024. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.FEC.RNEW.ZS (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Eurostat. Energy Imports Dependency. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_IND_ID__custom_12901153/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- UNCTADSTAT. Productive Capacities Index, Annual, 2000–2022. 2024. Available online: https://unctadstat.unctad.org/datacentre/dataviewer/US.PCI (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- World Bank. GDP per Capita (Constant 2015 US$). 2023. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Climate Watch. Historical GHG Emissions. 2024. Available online: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Emirmahmutoglu, F.; Kose, N. Testing for Granger Causality in Heterogeneous Mixed Panels. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 870–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, H.Y.; Yamamoto, T. Statistical Inference in Vector Autoregressions with Possibly Integrated Processes. J. Econom. 1995, 66, 225–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross-section Dependence. J. Appl. Econom. 2007, 22, 265–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).