Abstract

The subject of this publication is an analysis of the sentiment of stock exchange investors in terms of making investment decisions in the energy sector of the Polish stock exchange. The investment mood is considered in the context of the possible impact of weather factors on investment decisions. Possible effects are verified in relation to the rates of return and the volume of trading of energy sector entities. The analysis is carried out both in terms of co-integration analyses as well as in econometric terms, in the cross-section of classic OLS models or causality analysis using VAR vector autoregression models. The main purpose of the issues discussed is the problem of indicating (illustrating) the presence or absence of mutual relations between weather factors and the stock market in terms of the methods considered.

1. Introduction

The traditional theory of finance assumes that market participants are rational, and the goal they all pursue is profit maximization, which translates into high market efficiency. However, since the 1980s, many studies have suggested the existence of behavioral aspects of the market that are difficult to explain on the basis of traditional financial theory. The examples include the research conducted by Rajnish Mehr and Edward C. Prescott [1]. They noticed that there was a 6% gap between the return on the S&P 500 index and the risk-free interest rates, which is difficult to explain in a rational way. Of course, there are many more examples of this type. Consequently, this leads to certain market disturbances caused by the lack of complete market information. As suggested by Daniel Kahneman, Jack L. Knetsch and Richard Thaler [2], people are concerned about phenomena, situations that are not described by traditional financial theory.

As a result, contemporary research is mainly related to the analysis of the impact of non-economic factors on financial markets and the mechanisms governing them. Consequently, this translates into an analysis of the behavior of investors as basic market participants. An important element of the analyses carried out in this area is an attempt to determine the possible impact of weather factors on the stock exchanges. According to psychologists, the weather has a significant impact on people’s moods and, therefore, on their decision-making processes. This state of affairs may cause changes in, for example, share prices. According to many [3,4], climate change has a significant psychological impact on people, prompting them to behave in certain ways. However, in order for the factors under consideration to influence the decisions made, decision makers must be exposed to their influence [5].

Weather factors and natural biorhythms can be described as non-economic variables in terms of traditional equity pricing models. Differences in these variables have been shown to have a significant impact on people’s moods [6]. This is important because, as argued by Loewenstein G. [7], feelings experienced during decision making “often direct behaviors in different directions from those dictated by balancing the long-term costs and benefits of different actions”. As capital valuation relates essentially to the risk of future cash flow of capital and net cash flow participation rights of capital, an increasing number of behavioral finance scientists are investigating whether and to what extent mood swings, mainly caused by weather changes, affect or may affect the stock market.

Based on studies that have found a relationship between weather and sentiment, investors tend to price stocks higher (optimistically) when they are in a good mood due to the weather and lower (pessimistic) for negative weather influences. Saunders E.M. [8], who analyzed the relationship between cloudiness in New York and returns on the US stock market, moved towards this direction. In his research, he indicated the importance of cloud cover, and, thus, also insolation, for the percentage changes in share prices. Several years after these studies, Hirshleifer D. and Shumway T. [9], extending their scope, additionally analyzed the impact of rainfall and snow on returns in the Irish Datastream market index. Others, in turn, such as Floros C. [10], checked in their analyses the relationship between the temperature factor and market returns. The possible impact of weather on the variability of Korean KOSPI200 options was analyzed by Shim H. et al. [11] concluding that the volatility tends to increase on windless days. Subsequent research extended the study of the relationship between weather and stock prices to include different weather phenomena (i.e., temperature, precipitation, humidity, wind speed) and different countries [12,13,14,15]. These studies additionally confirm the theses that changes in mood caused by a number of weather phenomena are related to changes in stock prices.

There is really a lot of research indicating the significant impact of weather factors on stock market investments or those of slightly less importance in this respect, and it is impossible to list them all here. Nevertheless, a number of them document a strong link between weather patterns and stock index returns, providing indirect evidence of the impact of investor sentiment on asset prices.

Investigating the impact of weather patterns on the actual perception of investors is important, for instance, to establish the credibility of the weather effect from existing evidence. Therefore, in order to assess the significance of the possible impact of weather factors, research in this area should be continued.

Thus, the motivation of the considerations presented in the paper is not so much influenced by the traditional financial theory, but by the emotional reactions caused by the change in weather conditions affecting the performance of the quotations of the energy sector companies. Its content consists of considerations on weather factors as causative elements in the context of the investment sentiment analysis. Therefore, the research hypothesis is based on the assumption that in the case of quotations measured by the rate of return and the trading volume, the above-mentioned meteorological factors are an important causal element. The entire analysis is carried out both in terms of co-integration as well as formal causality in the Granger sense.

2. Emotions–Weather–Market

Psychological literature considers how emotions and moods influence people’s decision making. People who are in a good mood seem to be more optimistic about their own choices. A very strong effect in this regard is that people in a positive mood have many kinds of positive assessments, such as satisfaction with life, with past events, with people or even consumer products [16,17]. There is a mood-compatible effect in which people with a bad or good mood tend to find that negative or positive material, respectively, is more accessible or more pronounced [18,19]. More importantly, it is stated that mood most strongly influences relatively abstract judgments about which no specific information is available [20,21].

Research also shows that in a good mood, we are more likely to use simplified heuristics to aid our decision-making process [22,23]. There is an ongoing debate as to whether this type of use of heuristics reflects possible cognitive deficiencies associated with good mood, or is it more the effective use of measures to simplify complex data.

Some of the studies conducted so far indicate that a bad mood induces investors to undertake analytical activities to a large extent, while a good mood refers to less critical methods of information processing [24,25,26]. As reported, for example, by Bless H. et al. [27] good moods result in greater reliance on information about the category and, thus, simplify stereotypes. Thus, in their view, good moods make people rely more on “pre-existing structures of knowledge”, which does not necessarily result in a general decline in motivation or the ability to think effectively. Positive moods also have their advantages. In a good mood we often tend to create unusual associations, we become better at creative problem solving, and we show much greater mental flexibility. Moreover, being in a good mood, we tend to work out more detailed tasks with neutral/positive (at least not negative) stimulus material [23].

Emotions influence assessments of both the favorable outlook for the future [28,29] and risk assessments [30,31]. The direction of the influence of mood on the perception of risk is a complex process depending primarily on the task itself and the situation in which we are.

An important thread of emotions or moods (the so-called affective states theory) is that they provide individuals with information about the environment [24,32]. A significant amount of research confirms the informative role of the effect, as in [24,33] and [20]. The feelings-based decision-making procedure was named by Slovic P. et al. [31] as “Affect Heuristics”.

We very often attribute our feelings to the wrong source, leading to wrong judgments. An example of this is that people are happier on sunny days and are less positive on cloudy days. The influence of sunlight on their perception of happiness is much weaker when we ask about the weather [34]. Presumably, this is due to the fact that they attribute the good mood to the sun and not to long-term considerations.

Psychology has long documented the relationship between weather and behavior, focusing its research mainly on the effect of insolation. The vast majority of analyses suggest that we feel better when we are directly exposed to sunlight. Therefore, we are more optimistic on sunny days and more likely to buy stocks. Thus, a positive correlation is very often seen between insolation and rates of return. Moreover, information (as in the weather forecast) that a particular day will be sunny should not trigger an immediate and full positive response from stock prices. Only the exposure to sunlight itself should cause the price movement of financial instruments. However, it should be remembered that insolation in one specific place is not representative of weather conditions in the entire economy. It is also important that sunlight is a transient variable. The amount of the expected insolation today is not strongly correlated with the amount that will occur in a few days, weeks, or months.

As was shown much earlier, there is evidence that the sun influences markets. The confirmation of this can be found in the research of Saunders E.M. Jr. [8], which was mentioned in the introduction. In his research, apart from showing a negative dependence between cloud cover and returns from the New York Stock Exchange, he also proves that this correlation is resistant to various stock index selections and regression specifications.

As one can see, bad weather can complicate the market situation, communication or other activities. Hence, it seems reasonable to analyze the possible impact of other weather factors on the stock market as not only the right amount of sun can cause significant changes in the stock markets. There are a number of studies showing the importance of other weather determinants, such as temperature or atmospheric pressure (Table 1). Therefore, further research in this area may turn out to be extremely interesting and possible observations will give a new look at some dependencies.

Table 1.

Review of literature research on the emotions–weather–stock market relationship.

3. Materials and Methods

The research sample in these analyses are energy companies listed on the Warsaw Stock Exchange in 2015–2021. Possible causes of weather factors were analyzed in relation to the rates of return and the value of their trading volumes. The meteorological data were taken from the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management and concerned such weather factors as temperature, daily rainfall, sunshine duration, rainfall duration, average daily cloud cover, average daily wind speed, average relative humidity and average daily pressure at sea level. The location of the weather station was consistent with the seat of a given company listed. The research was limited to the Polish capital market due to the fact that there are no potential analyses of this type for the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. The cases of world studies concern either Asian markets, the American market or European countries with strong economies and well-functioning financial markets.

The analysis of the possible impact of meteorological factors on the stock market of energy companies should begin with the study of the phenomenon of co-integration. In this case, the correlation study did not bring satisfactory results as it did not talk about the long-term interdependence of the series. Thus, the correlation coefficients were not a suitable measure to rate the effect in question. Importantly, the co-integration effect may also occur when a low correlation is identified.

The most common approaches used to test the phenomenon are the Engle–Granger method [49] and the Johansen method [50]. The authors of the first proposed a relatively simple approach to the estimation of the degree of co-integration, namely the use of least squares regression and its application to the studied series. Then they proposed to perform a stationarity test (unit root test) for the residuals of the estimated regression model. However, both presented approaches are applicable in the case of non-stationary time series.

Therefore, initially, the stationarity of time series is analyzed using the most commonly used tests in this area, i.e., ADF (Augmented Dickey–Fuller test) and KPSS (Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt and Shine test) [51]. In the former, the null hypothesis is that the series is non-stationary. Thus, the alternative hypothesis is its negation. In the case of the KPSS test, we deal with the reverse system of hypotheses.

The use of these tests is also recommended by Hamulczuk, Grudkowska, Gędek, Klimkowski and Stańko [52] as the so-called confirming analysis. According to this, one deals with “strong” stationarity when it is found by both tests. In another variant, we talk about the lack of stationarity of the time series.

The possible finding of stationarity (or lack thereof) for dependent and independent variables generates two approaches to the causality analysis. In the case of a pair of doubly stationary variables, it is used in the classic OLS regression analysis (ordinary least squares). This approach allows the study of two-dimensional relationships between variables. Thus, this method is limited to model estimation

where xti is the independent variable (regressor) for the i-th measurement.

yt = α0 + α1xti + ξt,

In turn, in the variant when one of the variables analyzed or both are non-stationary, the best approach is VAR modeling (vector autoregressive model). In this case, assuming the same delays for both variables k, a test of the total significance of the delays of a given variable is applied in the equation explaining the second variable

The Akaike (AIC), Schwartz–Bayesian (BIC) or Hannan–Quinn (HQC) criteria are most often used when selecting lags. In this case, it is worth emphasizing that a one-way analysis showing the impact of meteorological variables on the stock market is substantively justified. The analysis in the reverse direction is pointless in terms of possible inference.

4. Results

The aforementioned analysis of the occurrence of the unit root in the context of the dependent variables (rate of return, trading volume) is illustrated by the results of Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of stationarity tests of the analyzed stock market time series.

The analysis of the values of individual test statistics allows the conclusion that the rate of return of the instruments considered is a stationary value in the “strong” sense. On the other hand, slightly different results are obtained when verifying the time series in the form of the trading volume. They are not homogeneous for both the tests. The KPSS test clearly excludes the stationary effect in this case. With a critical value of 0.743 for α = 0.01 in three cases, Kogeneracja, PGE and Polenergia, one could assume that the series is stationary. However, if we take the classical significance level of 0.05 (critical value 0.462), the occurrence of the unit root is common. Therefore, it is assumed that the trading volume is a non-stationary series. A possible increase in the number of delays does not significantly improve the value of the KPSS test statistics.

A similar analysis for weather variables requires a breakdown into individual weather stations (depending on the location of a given listed company) across the analyzed meteorological factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results of stationarity tests of the analyzed weather time series.

The data presented in the table above confirm to a large extent the non-stationarity of weather time series. Of course, there are cases of stationarity but they mainly relate to variables such as the daily sum of precipitation or the duration of rainfall. This is in some ways due to the nature of the data. One could assume some kind of “dichotomy” here. In ranks of this type, there are many observations when we deal with the lack of a phenomenon, hence, many values are just null.

Therefore, by making a distinction between stationary and non-stationary variables, one can perform the causality analysis in accordance with the principles presented a little earlier. Thus, in the case of a pair of double-stationary variables (explained and explanatory), the analysis of the influence of the weather factor on the market variable is carried out using classical econometric modeling (OLS). The results of this type of analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

OLS estimation results for the rate of return depending on the stationary weather factor along with testing the properties of the residual component.

Modeling, by means of regression equations, presented in Table 3 does not indicate the existence of a cause and effect relationship between the rate of return and the weather instrument of a stationary nature. However, it should be remembered that this type of analysis indicates linear relationships but nonlinear relationships may take place here as well. Since the presented analysis is based on a direct relationship at the same moment, it would be worth considering whether it is better to carry out similar tests but in relation to the shifted values of a given weather factor. After all, signals from a given meteorological regressor may have consequences on the next day, and, thus, affect the behavior of rates of return with a certain delay. There is little logical justification for examining a larger scale of delays than one. Hence, Table 5 presents the results of OLS estimation for the rates of return of the companies in question depending on the one-period lag of the stationary weather factor.

Table 5.

OLS estimation results for the rate of return depending on the one-period stationary lag of the weather factor together with testing the properties of the residual component.

The regression analysis illustrated in the table above does not show any clear relationships between the delayed weather factor and the rate of return.

The analysis of causality for pairs of non-stationary variables or those in which at least one variable is non-stationary is much more interesting. Essentially, it is the analysis of the dependent variable in terms of trading volume but not limited to this. Vector autoregression analysis (VAR) with co-integration tests has already been described in the methodological section. The results of the research are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

VAR causality test results for trading volume and weather factors with co-integration analysis.

In the causal analysis, using the VAR test, some dependencies of the trading volume on weather factors are noticed, but it is difficult to clearly identify the essential determinants in this respect. The most positive indications are from the variable wind speed. However, this is not a spectacular result because it only occurred in three cases out of nine analyzed entities. Other significant variables in this respect are average temperature, a daily sum of precipitation, duration of precipitation and, in a single case, humidity. Although the aforementioned relations are not very clear, they illustrate, to some extent, the impact of weather variables on the trading volume.

In order to complete the analysis, a causality study between the rate of return, stationary factor and non-stationary meteorological components should also be carried out (Table 7). The hitherto analysis of the rate of return concerned the regression analysis where a few factors were characterized by the lack of the unit root (Table 4 and Table 5). Therefore, the remaining weather factors for which the series stationary was excluded were omitted. The table below supplements the considerations so far.

Table 7.

VAR causality test results for the rate of return and non-stationary weather factors along with co-integration analysis.

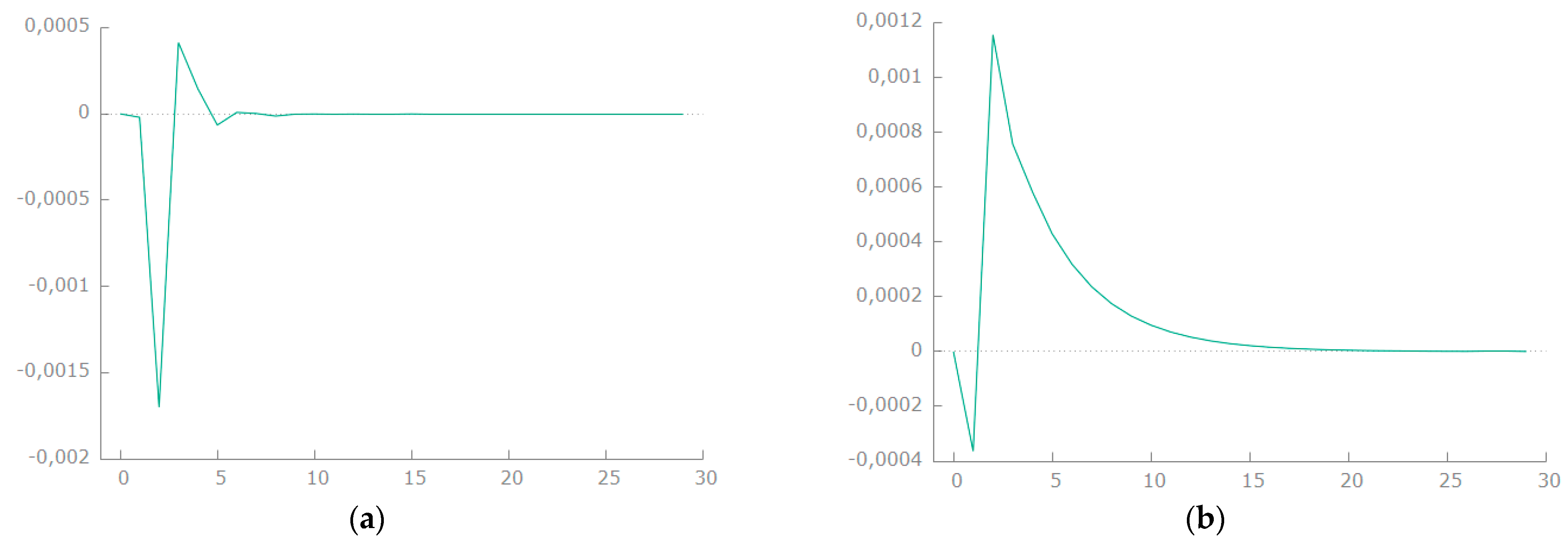

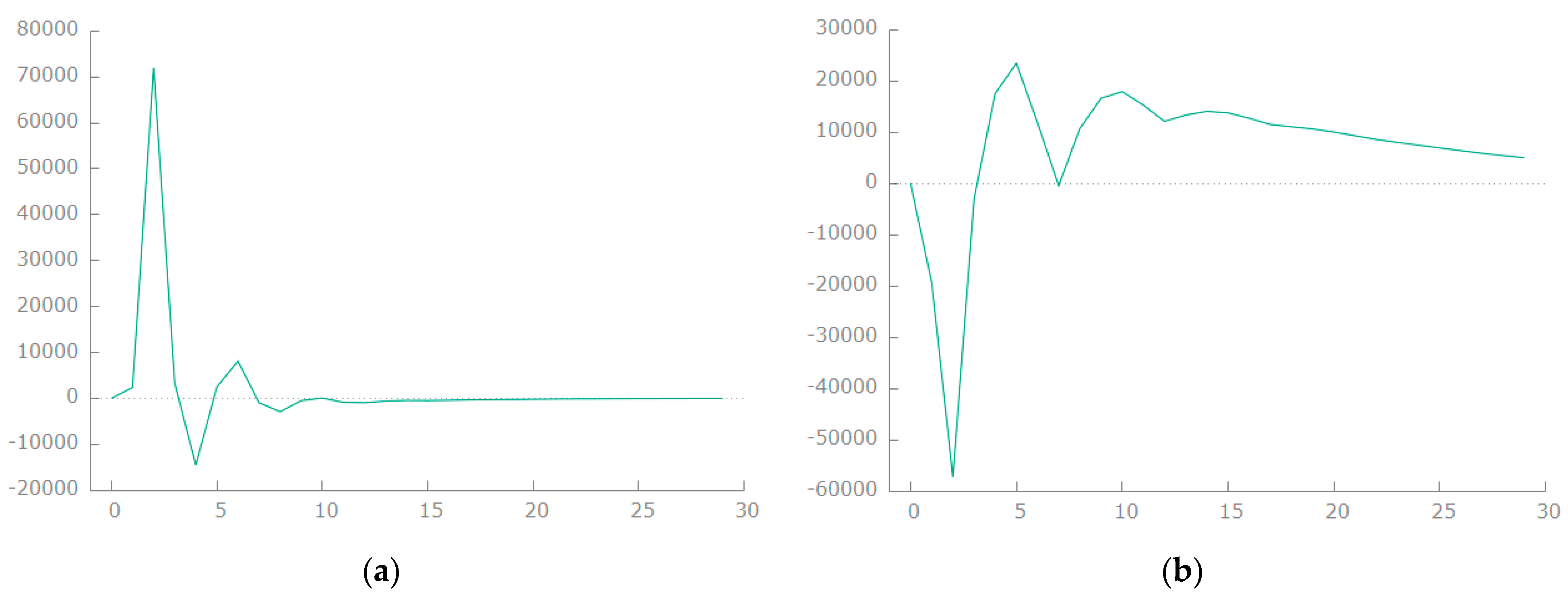

The occurrence of simultaneous covariance between the random components of individual equations included in the VAR model allows the creation of the so-called structural models [53]. Structural VAR models enable the construction of the impulse response function (IRF), which allows the description of the time dependence. It illustrates the time distribution of changes in the magnitude of one variable in response to disturbances in the other’s residuals. Most often, the IRF is presented graphically. The analysis of the impulse response function relates to three components: the direction of the impulse’s interaction, the strength of the impulse as well as the time distribution and the rate of decay [52]. An example of the IRF function is shown in Figure 1. In the case under consideration, the structure of the graph is as follows: the value of the rate of returns caused by a change in a given weather factor is placed on the graph’s ordinate, and the abscissa shows the time horizon of this impulse expressed in days. It is clear that changes in some weather variables trigger reactions in the percentage price changes (in this case, the Tauron company) in the first few periods. The decay of the pulses in both cases occurs fairly quickly, so the main reactions take place in the first few periods. The situation is similar in the case of impulse responses in relation to the trading volume (Energa case—Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Examples of functions of the rate of return reaction for Tauron, Katowice to an impulse: (a) insolation; (b) average daily relative humidity.

Figure 2.

Examples of the response functions of the trading volume for Energa, Gdańsk to the impulse: (a) average daily wind speed; (b) average daily relative humidity.

In the case of the VAR analysis for the relation rate of return ← the meteorological variable with the highest frequency of impact is relative humidity (33%). The variables insolation or cloudiness level have unitary indications in this regard. Thus, it is hard to define a tendency here. In this respect, it seems reasonable to make a summary list, which is a kind of compilation of the indications obtained so far in the section of the applied methodology. The results are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

The frequency of occurrence of the weather factor in the case of modeling the rate of return and the volume of trading in the cross-section of the methods used.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Summarizing the conclusions drawn, it can be stated that:

- not all analytical methods are equally effective. This can be clearly seen in the example of the VAR analysis. The number of positive indications obtained in this case significantly exceeds the relevance of weather factors in the OLS modeling. The limitations of the OLS methodology are described earlier;

- co-integration analysis with the use of the Engle–Granger and Johansen tests is in a sense unjustified as it always indicates relationships between variables. It, therefore, disrupts the general view of causal relationships;

- determining the direction of the relationship weather factor → rate of return may be based only on the values of the tangent of the angle of inclination in the regression analysis;

- the most common determinants of the rate of return and the volume of trading include the weather factor in the form of average daily relative humidity and average wind speed. The first of these weather variables is the cause of the percentage changes in stock prices, the second is responsible for changes in the trading volume. The results in this case are different from those obtained in the studies of the team of Tarczyński et al. [54] with the use of ARCH class models. Then, the variable with a clear influence was atmospheric pressure. Therefore, it can be assumed that the considered causality depends on the methodology used;

- the trading volume seems to be much more susceptible to possible influences from independent variables;

- impulse response functions turn out to be extremely useful in VAR analyses, allowing additional inference in the case of dependence from meteorological time series;

- it would be advisable to continue research in the causality area and to verify the effectiveness of indications in the context of the distribution of the analyzed variables. Perhaps the nature of the distribution itself (convergence or divergence with the normal distribution) may affect the final indications;

- in the case of some weather variables, consideration should also be given to take into account the phenomenon of seasonality over a longer period of time;

- in general, it can be said that the indications depend on the type of method used and the nature of the test itself. Hence, weather variables play a role in modeling the mood of stock market investors investing in the energy sector, mainly in the context of Granger causality analysis.

Summarizing all of the research conducted, it is impossible to notice that there is no unique systematic and permanent correlation in the weather–stock market relationship. While in the case of one study we have confirmation of a certain state and assumptions, when studying subsequent studies we may have a different opinion, or previous beliefs may not be so important. Therefore, when summarizing the information presented in this paper, it should be noted that there are many potential reasons for the lack of this consensus.

Time is a factor that must certainly be considered. As already stated, Chang S.C. et al. [55] proved the influence of changes in weather factors during the market opening. On the other hand, Akhtari M. [56] discovered that there was not only the time of day that needed to be considered but also specific moments of time. Additionally, he noticed a certain cyclical nature of the whole process over the years. Trombley M.A. [57] and Lee Y.M and Wang K.M. [58] additionally stated that the analyzed relationships tended to fluctuate somewhat throughout the year.

Location may be another important element in this regard. For instance, Keef S.P. and Roush M.L [44] showed that the significance of various weather factors depends to a large extent on the analyzed (specific) location. In their opinion, it is one of the most critical factors in this type of analysis as climatic conditions vary from place to place. Moreover, there is a certain degree of heterogeneity with regard to individuals as well as their psychological characteristics in different cultures and regions; therefore, it is very likely that this could trigger different market reactions in response to the same weather conditions depending on the location of the stock markets. This fact was also confirmed by Simeonidis L., Daskalakis G. and Markellos R. [39]. The team of Loughran T. and Schultz P. [35] indicated that the volume of trading in shares differs depending on the place of residence of stock investors, which also confirms the previous thesis. Therefore, different conclusions from similar studies can be explained by the significant variation in variables and locations.

Moreover, attention should be paid to the definitions and hypotheses used. They often turn out to be crucial. It is not only the way of formulating the null hypothesis that is important but also the definitions [59]. This has a direct impact on the final conclusions.

In addition, the type of investors is important. Levy O. and Galili I. [60] and Shu H. [61] proved that the significance of the meteorological determinant largely depends on the type of investors. Moreover, the test procedures and statistics applied may give erroneous results [57,60].

Generally, whether a given weather factor is significant or not depends on many components: time, place, weather definition, formulation of hypotheses, type of investor, the procedure used and test statistics used in the research.

In addition, modeling the impact of weather factors should also take into account other aspects that may often result in complex, often contradictory, results of research on analyzed weather–investor behavior relations:

- many studies of this type do not take into account the phenomenon of the seasonality of twists. This may cause a distortion of the causal relationships between investor behavior and meteorological factors;

- some analyses did not investigate whether variables take into account other weather indicators. For instance, the effect of a certain temperature level on mood may depend on whether or not it is raining;

- as a rule, this type of analysis does not take into account the behavior of investors at different times of the year. There may be a dependence that higher winter/summer temperatures may positively/negatively affect decision-making processes;

There are many questions and possible doubts. Therefore, there remains the issue of seeking answers that will actually confirm the relations considered. Thus, any question marks appearing in the article constitute the background for further research on the analyzed problem.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.M.; methodology, W.T. and U.M.; validation, U.M.; formal analysis, U.M.; investigation, U.M.; resources, U.M.; data curation, U.M.; writing—original draft preparation, U.M.; writing—review and editing, W.T., G.M. and U.S.; visualization, W.T., G.M. and U.S.; supervision, W.T., U.M., G.M. and U.S.; project administration, W.T. and U.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is part of the research carried out by Urszula Mentel in her doctoral dissertation entitled ‘Weather conditions as a determinant of volatility in the stock market. Behavioral quantitative analysis’.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mehra, R.; Prescott, E.C. The equity premium: A puzzle. J. Monet. Econ. 1985, 15, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R. Fairness as a constraint on profit seeking: Entitlements in the market. Am. Econ. Rev. 1986, 76, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.A.; Fischer, G.J. Ambient Temperature Effects on Paired Associate Learning? Ergonomics 1978, 21, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.-Y.; Xie, X.; Li, J. Negative or positive? The effect of emotion and mood on risky driving. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 16, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.C.; Fredrickson, B.L.; Ybarra, O.; Cote, S.; Johnson, K.; Mikels, J.; Conway, A.; Wager, T. A Warm Heart and a Clear Head: The Contingent Effects of Weather on Mood and Cognition. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, E.; Hoffman, M.S. A multidimensional approach to the relationship between mood and weather. Br. J. Psychol. 1984, 75, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loewenstein, G. Emotions in Economic Theory and Economic Behavior. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, E.M. Stock prices and the Wall Street weather. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, D.; Shumway, T. Good Day Sunshine: Stock Returns and the Weather. J. Financ. 2003, 58, 1009–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floros, C. Stock market returns and the temperature effect: New evidence from Europe. Appl. Financ. Econ. Lett. 2008, 4, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Ryu, D. Weather and stock market volatility: The case of a leading emerging market. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2014, 22, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Valor, E. Spanish stock returns: Where is the weather effect? Eur. Financ. Manag. 2003, 9, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wei, J. Stock market returns: A note on temperature anomaly. J. Bank. Financ. 2005, 29, 1559–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Nieh, C.-C.; Yang, M.J.; Yang, T.-Y. Are stock market returns related to the weather effects? Empirical evidence from Taiwan. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2005, 364, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, M.; Lucey, B.M. Robust global mood influences in equity pricing. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2008, 18, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, W.F.; Bower, G.H. Mood effects on subjective probability assessment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1992, 52, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Gopinath, M.; Nyer, P.U. The Role of Emotions in Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A.M.; Shalker, T.E.; Clark, M.; Karp, L. Affect, accessibility of material in memory, and behavior: A cognitive loop? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1978, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgas, J.P.; Bower, G.H. Mood effects on person-perception judgments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clore, G.L.; Schwarz, N.; Conway, M. Affective causes and consequences of social information processing. In Handbook of Social Cognition: Basic Processes; Applications; Wyer, W.R.S., Srull, T.K., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 323–417. [Google Scholar]

- Forgas, J.P. Mood and judgment: The affect infusion model (AIM). Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 39–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bless, H.; Schwarz, N.; Kemmelmeier, M. Mood and Stereotyping: Affective States and the Use of General Knowledge Structures. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 7, 63–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A. Positive affect and decision making. In Handbook of Emotions; Lewis, W.M., Haviland-Jones, J., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 261–277. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, N. Feelings as information: Informational and motivational functions of affective states. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition; Sorrentino, W.R., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guildford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 2, pp. 527–561. [Google Scholar]

- Petty, R.E.; Gleicher, F.; Baker, S.M. Multiple roles for affect in persuasion. In International Series in Experimental Social Psychology. Emotion and Social Judgments; Forgas, W.J.P., Ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1991; pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, R.C.; Mark, M.M. The effects of mood state on judgemental accuracy: Processing strategy as a mechanism. Cogn. Emot. 1995, 9, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bless, H.; Clore, G.L.; Schwarz, N.; Golisano, V.; Rabe, C.; Wolk, M. Mood and the use of scripts: Does being in a happy mood really lead to mindlessness? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 665–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.J.; Tversky, A. Affect, generalization, and the perception of risk. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkes, H.R.; Herren, L.T.; Isen, A.M. The role of potential loss in the influence of affect on risk-taking behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1988, 42, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewenstein, G.F.; Weber, E.U.; Hsee, C.K.; Welch, N. Risk as feelings. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P.; Finucane, M.L.; Peters, E.; MacGregor, D.G. The affect heuristic. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 177, 1333–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H. The laws of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1988, 43, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T.D.; Schooler, J.W. Thinking too much: Introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 60, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T.; Schultz, P. Weather, Stock Returns, and the Impact of Localized Trading Behaviour. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2004, 39, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamstra, M.J.; Kramer, L.A.; Levi, M.D. Losing sleep at the market: The daylight saving anomaly. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, S.H.; Jiang, Z.; Yoon, S.M. Weather Effects on the Returns and Volatility of Hong Kong and Shenzhen Stock Markets. 2010. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.466.5379&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Dowling, M.; Brian, M.L. Weather, Biorhythms, Beliefs and Stock Returns Some—Preliminary Irish Evidence. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2005, 14, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, L.; Daskalakis, G.; Markellos, R.N. Does the weather affect stock market volatility? Financ. Res. Lett. 2010, 7, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goetzmann, W.N.; Zhu, N. Rain or Shine: Where is the Weather Effect? Eur. Financ. Manag. 2005, 11, 559–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Kubik, J.D.; Stein, J.C. Social Interaction and Stock-Market Participation. J. Financ. 2004, 59, 137–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vlady, S.; Tufan, E.; Hamarat, B. Causality of Weather Conditions in Australian Stock Equity Returns. Rev. Tinerilor Econ. 2011, 1, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, A. An Empirical Note on Weather Effects in the Australian Stock Market. Econ. Pap. A J. Appl. Econ. Policy 2009, 28, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keef, S.P.; Roush, M.L. Daily weather effects on the returns of Australian stock indices. Appl. Financ. Econ. 2007, 17, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-T.; Lin, J.D. Does weather impact the stock market? Empirical evidence in Taiwan. Qual. Quant. 2011, 46, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, G. Analyzıng Weather Effect on Istanbul Stock Exchange: An Empırıcal Analysıs for 1987–2006 Period. Econ. Financ. Rev. 2014, 3, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.; Almeida, L. Weather and Stock Markets: Empirical Evidence from Portugal; MPRA Paper 54119; University Library of Munich: Munich, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zadorozhna, O. Does Weather Affect Stock Returns Across Emergıng Markets? Master’s Thesis, Kyiv School of Economics, Kyiv, Ukraine, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Engle, R.F.; Granger, C.W.J. Co-Integration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation, and Testing. Econometrica 1987, 55, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. Statistical analysis of cointegration vectors. J. Econ. Dyn. Control. 1988, 12, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddala, G.S. Ekonometria; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hamulczuk, M.; Grudkowska, S.; Gędek, S.; Klimkowski, C.; Stańko, S. Essential Econometric Methods of Forecasting Agricultural Commodity Prices; Institute of Agricultural and Food Economics—National Research Institute: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kusideł, E. Dane Panelowe i Modelowanie Wielowymiarowe w Badaniach Ekonomicznych; Absolwent: Łódź, Poland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tarczyński, W.; Majewski, S.; Tarczyńska-Łuniewska, M.; Majewska, A.; Mentel, G. The Impact of Weather Factors on Quotations of Energy Sector Companies on Warsaw Stock Exchange. Energies 2021, 14, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Chen, S.-S.; Chou, R.; Lin, Y.-H. Weather and intraday patterns in stock returns and trading activity. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1754–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtari, M. Reassessment of the Weather Effect: Stock Prices and Wall Street Weather. Undergrad. Econ. Rev. 2011, 7, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Trombley, M.A. Stock Prices and Wall Street Weather: Additional Evidence. Q. J. Bus. Econ. 1997, 36, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Wang, K.-M. The effectiveness of the sunshine effect in Taiwan’s stock market before and after the 1997 financial crisis. Econ. Model. 2011, 28, 710–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, W.; Runde, R. Stocks and the Weather: An Exercise in Data Mining or Yet Another Capital Market Anomaly? Empir. Econ. 1997, 22, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, O.; Galili, I. Stock purchase and the weather: Individual differences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 67, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.-C. Investor mood and financial markets. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2010, 76, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).