Abstract

This study investigates the valuation dynamics of 30 publicly listed fintech firms across six Asian economies from January 2021 to December 2025. It examines how intrinsic firm-level scale (market capitalization) and extrinsic macroeconomic conditions (GDP growth) jointly influence fintech valuation ratios, as reflected in price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-book (P/B), and price-to-sales (P/S) measures. It also identifies significant structural heterogeneity and distributional asymmetries in valuation outcomes by implementing a multi-method empirical strategy that includes a Panel Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) framework, two-way fixed-effects models with interaction terms, and quantile regression. The findings reveal a robust, positive long-run relationship between market capitalization and valuation multiples across all ratios, confirming that firm-level scale as reflected in market capitalization is the primary driver of market value. Critically, the analysis identifies a dual-regime landscape in the Asian fintech sector: developed markets (South Korea, Japan, and Singapore) are fundamentally firm-scale driven, where intrinsic scale is the superior predictor of valuation. In contrast, developing markets (China, India, and Indonesia) are primarily macro-growth driven, exhibiting high sensitivity to GDP growth as a macroeconomic indicator of market expansion. The quantile regression results demonstrate a winner-takes-all effect, where the impact of scale on valuation is significantly more pronounced for highly valued firms in the 75th percentile. These results challenge the efficacy of universal valuation models and provide a context-dependent navigational framework for investors, analysts, and policymakers to distinguish between structural scale and cyclical growth in the rapidly evolving Asian fintech ecosystem.

1. Introduction

The emergence of fintech in Asia has been nothing short of revolutionary that has transformed traditional financial services by using innovations in the space of digital payments, peer-to-peer lending, and blockchain technologies. Fintech companies are the disruptive force that has challenged the status quo and offered greater convenience, accessibility, and affordability. It has also fulfilled the growing demands of the burgeoning middle class of the region (Arnaut & Bećirović, 2023). The increase in fintech activity is driven by several interconnected factors, including rapid economic growth, increasing mobile penetration, supportive government policies, and the technological advancements. Rapid economic growth in Asia has created a strong foundation for fintech innovations. The expanding middle class in countries like China and India has led to an increase in disposable incomes, which has resulted in a higher demand for financial services. This demographic is constantly looking for more sophisticated financial products and services that are often more efficient. These are effectively delivered by fintech companies rather than traditional banks (Xia et al., 2023). The convenience and accessibility offered by these fintech solutions have made them appealing to this underserved market segment. The popularity of internet connectivity and smartphone use has been instrumental in the development of fintech in Asia. The mobile phone penetration rate in this region is one of the highest in the world and therefore it opens up digital financial services to millions of people. Consequently, this has allowed the proliferation of mobile banking, digital wallets, and other fintech solutions that serve the interests of various customer groups due to the increased connectivity. As an example, over half of the population in China and India has access to smartphones and the internet, making them the most suitable markets for mobile-based fintech solutions. Despite this rapid expansion, there remains limited empirical clarity on how fintech firms are valued across heterogeneous Asian market environments, especially with respect to the relative roles of firm-level scale and macroeconomic conditions.

Many governments in Asia have embraced supportive policies to encourage development in the fintech sector and support innovation. Countries like Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, India, China, and Indonesia have established regulatory sandboxes that allow fintech companies to test their products and services in a controlled environment before launching them in the broader market. These sandboxes effectively lower the regulatory burden on startups and promote innovation. Governments are also increasingly investing in infrastructure projects in order to support fintech growth. These investments include focusing on the improvement of internet connectivity and easing access to funding for fintech startups. Advancements in technologies driven by blockchain, artificial intelligence, and big data have enabled the creation of new and innovative fintech products and services. Blockchain technology has the potential to revolutionize payment systems by the way of providing faster, more secure, and transparent transactions (Weerawarna et al., 2023). Artificial intelligence, on the other hand, is being used to develop advanced algorithms for credit scoring, fraud detection, and personalized financial advice (Adhikari et al., 2024). Similarly, big data analytics is helping fintech companies understand customer behavior and preferences, which enables them to tailor their products and services more effectively (Mhlanga, 2024).

As fintech companies continue to grow and mature, understanding their valuation dynamics becomes increasingly crucial for investors, analysts, and policymakers. Asia provides a uniquely suitable empirical setting for this analysis, as it simultaneously hosts some of the world’s most mature fintech ecosystems (Japan, South Korea, Singapore) alongside large, fast-growing emerging markets (China, India, Indonesia), allowing a structured comparison across distinct stages of financial and institutional development. Traditional valuation metrics are often used by established financial institutions, but they may not be entirely suitable for valuing fintech companies due to their innovative business models, rapid growth trajectories, and the intangible assets that they often hold. The valuation of fintech companies has unique challenges compared to traditional financial institutions. Many fintech companies accumulate significant intangible assets, like intellectual property, brand value, and customer data. These assets can be difficult to quantify and value using traditional accounting methods. Intellectual property may include proprietary algorithms or software that are critical to the operations of fintech companies. For companies that have successfully built a strong reputation and customer base, their brand value can also be substantial. Customer data is another important intangible asset, as it can provide valuable insights into consumer behavior and preferences (Patterson, 2023; D. Liu et al., 2009). Fintech companies often experience rapid growth, which makes it challenging to predict future earnings and cash flows accurately. This can lead to uncertainty in valuation models. Rapid growth can be both an advantage and a disadvantage. On the one hand, it can lead to high valuations due to the potential for significant future profits. On the other hand, it can also increase the risk of overvaluation if the growth trajectory of the company does not materialize as expected (Moro-Visconti et al., 2020). The regulatory landscape for fintech companies varies significantly across different Asian countries. These differences can impact the valuation of fintech firms operating in different jurisdictions. In some countries, fintech companies may face stricter regulations and compliance requirements, which can increase operating costs and reduce profitability. In other countries, regulations may be more favorable and support fintech companies with greater opportunities for growth and expansion (Noviantoro et al., 2020). Fintech companies often have innovative business models that may not fit traditional valuation frameworks. This requires analysts to develop new approaches for the valuation of these companies. For instance, some fintech companies operate on a platform-based model that connects borrowers and lenders directly, as contrast to them acting as intermediaries. This model can provide significant cost savings and efficiency gains, but its valuation can be difficult using traditional metrics (Moro-Visconti, 2020).

To assess the value of fintech companies, investors frequently use valuation ratios such as price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-book (P/B), and price-to-sales (P/S). However, there remains limited empirical clarity on how firm-level scale and macroeconomic growth jointly shape fintech valuation ratios, and on whether these relationships systematically differ between developed and developing market contexts. There is a need to bridge this knowledge gap in order to enable investors, companies, and policymakers to make informed decisions in the fintech sector, especially while evaluating decisions that involve fintech companies across different global markets. Therefore, this study aims to investigate how market capitalization and GDP growth affect fintech valuation ratios and whether market type (developed vs. developing) moderates these relationships. It integrates dynamic panel methods, cross-market interaction models, and distributional analysis to contribute to the fintech valuation literature by identifying regime-specific valuation drivers across Asian markets and illustrating the limitations of universal valuation frameworks in capturing structural market heterogeneity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

One of the recurring themes in the fintech valuation literature is the complexity of accurately valuing fintech startups due to their unique business models and reliance on digital intangibles. Digital intangibles play a crucial role in determining the valuations of fintech firms, especially in early-stage startups, where traditional financial metrics may not fully capture the value potential (Moro-Visconti, 2020). This notion is supported by Patterson (2023), who emphasizes the need to distinguish between valuation and pricing while analyzing fintech firms. The difficulty in establishing clear valuation metrics is further compounded by the rapid pace of technological change in the industry, which leads to the use of both traditional and innovative valuation techniques. While these studies contribute to a broader understanding of the valuation methods for fintech companies, they also highlight the lack of a standardized approach across the industry, with many valuations being highly context-specific. The rapidly evolving fintech landscape necessitates a more adaptive approach to valuation, underscoring the potential of technology-driven approaches like neural networks for predicting stock prices, indicating a future direction for fintech valuation methods (Han & Kim, 2021).

Technological innovation is integral to fintech, which influences not only the services offered but also how these firms are valued. The integration of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning has changed traditional approaches to valuation. The use of machine learning in stock price prediction highlights its potential in fintech valuations in frontier markets (Chowdhury et al., 2020). This technological shift allows for the consideration of non-traditional metrics, which include customer data usage and intellectual property, in determining firm value. Technology is becoming increasingly relevant in assessing fintech firms because their reliance on data and intellectual capital is becoming more pronounced. Kabulova and Stankevičienė (2020) supports this by pointing out the importance of intellectual property, such as patents, in fintech valuations. The growing role of technology-based assets thus represents a significant departure from traditional valuation models that predominantly focus on tangible assets.

The fintech sector operates in a highly dynamic market where regional variations play a significant role in valuation practices. Li and Zhang (2024) and Noviantoro et al. (2020) contribute to the understanding of how local market conditions in China and Indonesia shape fintech valuations. Regional market characteristics such as regulatory environments, economic conditions, and investor sentiment all influence how fintech firms are perceived and valued. These findings are relevant to the present study, as we analyze fintech firms across Asian markets, recognizing that regional differences can affect both the valuation methodologies and outcomes. The cross-market comparison between developed and developing economies provides valuable insights into how fintech firms’ valuations vary in different regulatory and economic contexts. Although developing markets such as India and China present higher growth potential, they also carry greater risks, which can be reflected in more volatile valuation ratios.

Sustainability factors, environmental, social, and governance (ESG), have emerged as the key considerations in fintech valuation and the firms are increasingly held accountable for their broader societal impact. Moro-Visconti et al. (2020) examines the role of sustainability in fintech valuation and emphasizes the growing importance of incorporating ESG factors into valuation frameworks. This is also pertinent in light of global trends towards more socially responsible investment practices, which favor firms that demonstrate a commitment to sustainable growth. The inclusion of sustainability metrics in fintech valuation aligns with broader shifts in investor preferences among institutional investors who prioritize long-term value creation over short-term financial performance. However, the integration of ESG factors remains a challenge, as these intangibles are difficult to quantify, which makes it harder to assess their impact on firm value in a consistent manner (Christofi et al., 2024).

Intellectual capital, including human resources, patents, and proprietary technologies, is becoming a critical factor in fintech valuations. According to D. Liu et al. (2009) Intellectual capital plays a pivotal role in value creation for firms operating in highly innovative sectors like fintech. Di Marcantonio et al. (2015) supports this by demonstrating the link between intellectual capital and financial performance and also highlights how intangible assets such as patents and proprietary technologies can significantly enhance the valuation of the firms. The increasing importance of intellectual capital in fintech firms underscores the shift from traditional tangible assets to knowledge-based resources, which are the key drivers of firm value. This aligns with the broader trend in the fintech industry, where innovation and technological advancement are central to competitive advantage and long-term growth.

Fintech firms often face unique challenges in securing funding due to their reliance on intangible assets, innovation, and cutting-edge technology. The traditional valuation models are inadequate to address this challenge. Emerging literature highlights the growing importance of innovative financing mechanisms that align with the distinctive nature of fintech firms. For instance, Wang (2024) discusses contingent options for value appreciation, presenting new funding mechanisms that are tailored specifically to fintech startups. This allows for greater flexibility in financing, which is crucial in the rapidly evolving fintech sector. Sushil (2016) adds to this by emphasizing the importance of strategic flexibility within fintech ecosystems, noting that firms that can adapt to changing market conditions often have higher valuations. Risk management strategies in fintech valuations are important because high risks associated with technological innovation and regulatory uncertainty must be balanced against their growth potential. Effective risk management, including innovative hedging techniques, can thus play a significant role in fintech valuations. This highlights the integral role of financing flexibility and risk management in fintech valuation, underscoring the need for models that reflect the unique risk and growth dynamics of the industry (Cui et al., 2021).

2.2. Theoretical Framework

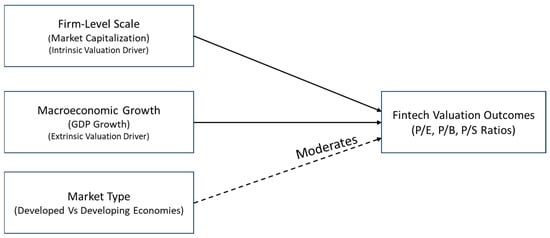

This study is grounded in valuation theory, which posits that both intrinsic factors and extrinsic factors influence a company’s value (Damodaran, 2012). The firm-level scale is operationalized using market capitalization as a proxy for intrinsic valuation factors, while macroeconomic growth is captured through GDP growth as a proxy for extrinsic market conditions. The valuation ratios, price-to-earnings (P/E), price-to-book (P/B), and price-to-sales (P/S) reflect future growth expectations and perceived risks of the company (J. Liu et al., 2002). Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework used in this study.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework based on Valuation Theory.

The following hypotheses were formulated based on the theoretical framework:

Hypothesis 1.

There is a significant positive relationship between market capitalization and the valuation ratios (P/E, P/B, P/S) of publicly listed fintech companies.

Hypothesis 2.

There is a significant positive relationship between GDP growth and the valuation ratios (P/E, P/B, P/S) of publicly listed fintech companies.

Hypothesis 3.

The effects of market capitalization and GDP growth on valuation ratios differ between developed and developing markets.

2.3. Data and Methodology

This study uses a multi-method empirical strategy to examine how firm-level scale and macroeconomic conditions jointly shape the valuation of publicly listed fintech firms, while allowing for dynamic adjustment, structural heterogeneity, and distributional asymmetries in valuation outcomes. Fintech valuations are inherently forward-looking and evolve through the interaction of persistent long-run fundamentals and short-run market responses to economic signals. Consequently, a single static estimation framework is insufficient to capture the full valuation process, and the empirical design therefore combines panel ARDL to identify long-run relationships, fixed-effects interaction models to formally test cross-market heterogeneity, and quantile regression to assess whether these relationships vary across different segments of the valuation distribution. This layered methodological approach ensures that the hypotheses are tested in a manner consistent with valuation theory, the institutional diversity of fintech markets, and the empirical properties of the data, while also providing a coherent foundation for the interpretation of results.

The analysis is based on a balanced panel of 30 publicly listed fintech firms drawn from six Asian economies, with five firms selected from each country. The country set is deliberately constructed to include both developed and developing markets, enabling a structured comparison of valuation dynamics across different stages of financial and institutional development. Specifically, South Korea, Japan, and Singapore are classified as developed markets (Market Type = 1), while China, India, and Indonesia represent the developing market cohort (Market Type = 0). This ex-ante classification is used consistently throughout the analysis and forms the basis for the market-type variable used in heterogeneity testing. The developing market sample includes specific entities such as China Life Insurance (2318) and HDFC Bank (HDFCB), alongside others like CAMS, CDSL, and IEX to ensure a representative mix of fintech business models. The sample composition containing company information is given in Appendix A.

The firms were selected on the basis of continuous listing over the study period, availability of monthly valuation and market capitalization data, and clear identification as fintech entities engaged in digital payments, platform-based financial services, or technology-driven banking solutions. The inclusion of firms from multiple institutional environments introduces potential cross-country heterogeneity, which is explicitly modeled rather than treated as a source of bias. The study covers the period from January 2021 to December 2025 using monthly observations, a timeframe that encompasses the post-pandemic acceleration of digital services and episodes of global monetary tightening. Monthly frequency is appropriate for valuation ratios, which adjust more rapidly to performance and macroeconomic expectations than annual accounting measures. The final dataset comprises a balanced panel with 30 cross-sectional units observed over 60 months, yielding a total of 1800 firm-month observations.

One of the significant challenges in analyzing data from multiple countries is the inconsistency in the scale of financial metrics when reported in different currencies. To address this problem and ensure comparability across different currencies and scales, all continuous variables, including valuation ratios, market capitalization, and GDP growth, are standardized using Z-score transformation prior to estimation. This normalization mitigates distortions arising from currency denomination and scale effects, improves numerical stability in models involving interaction and terms, and allows coefficients to be interpreted in standardized terms as the effect of a one standard deviation change. Standardization does not affect the existence or direction of long-run relationships in the Panel ARDL framework but facilitates comparability across firms and countries with heterogeneous scales.

The empirical framework is constructed around market-based valuation measures that capture investors’ expectations about firm performance, growth prospects, and risk. Three alternative valuation ratios are used as dependent variables: the price-to-earnings ratio (P/E), the price-to-book ratio (P/B), and the price-to-sales ratio (P/S). Using multiple valuation metrics allows the analysis to capture different dimensions of market valuation, with the P/E ratio reflecting expectations about profitability, the P/B ratio capturing accounting net worth value, and the P/S ratio being particularly relevant for high-growth fintech firms with volatile earnings. Market capitalization (MC) is used as the primary firm-level explanatory variable, serving as a proxy for firm size and market dominance. At the macroeconomic level, GDP growth is included to capture the broader economic conditions. To examine cross-market heterogeneity, a binary market-type indicator and its interaction with key explanatory variables are introduced to test whether valuation effects differ across market contexts. The description of variables is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Variables.

Throughout the analysis, firm-level scale and firm size are used interchangeably to denote market-based scale as proxied by market capitalization.

2.3.1. Panel ARDL Framework

The core analysis for Hypotheses 1 and 2 applies a panel autoregressive distributed lag (Panel ARDL) framework, which is well-suited for a setting where the time dimension is relatively long. The Panel ARDL methodology allows the simultaneous estimation of short-run dynamics and long-run equilibrium relationships between valuation ratios and their determinants. For each valuation ratio, the baseline long-run relationship is expressed as:

In this equation, the variables represent standardized values of the valuation ratios, market capitalization, and GDP growth at firm-level (), time (), and country-level (). To capture dynamics explicitly, this long-run relationship is embedded within an ARDL structure where lag orders are selected using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to balance model fit and parsimony, with a maximum lag order of 4 capturing both short-term fluctuations and long-term equilibrium relationships. Mean Group (MG) was adopted as the baseline Panel ARDL estimator because it permits heterogeneous short-run adjustments and heterogeneous long-run coefficients across firms, which is appropriate in a cross-country fintech sample where valuation formation may differ by market structure and institutional setting. A Hausman-type specification test was then used to assess whether a more restrictive pooled long-run specification (Dynamic Fixed Effects (DFE)-type restriction) is empirically admissible; where the restriction is not rejected, results are interpreted as broadly consistent with pooled long-run behavior, but MG estimates are retained for inference given their consistency under slope heterogeneity.

2.3.2. Testing Cross-Market Heterogeneity (H3)

To formally examine whether the valuation effects differ across market types, Hypothesis 3 is tested using a single-equation fixed-effects framework with interaction terms. While the Panel ARDL approach identifies long-run relationships, a two-way fixed-effects (FE) static panel model is better structured for conducting formal coefficient comparison tests. This model isolates the moderating impact of market type by classifying firms where the market-type variable takes the value zero for developing markets and one for developed markets. Market type classification is based on an exogenous, standard market development categorization. Fintech firms operating in Japan, South Korea, and Singapore are classified as belonging to developed markets, while firms operating in China, India, and Indonesia are classified as belonging to developing markets. This classification is time-invariant over the sample period and is implemented through a binary indicator (). The interaction equation used to test Hypothesis 3 is defined as:

This specification denotes firm fixed effects and captures time fixed effects to control for common shocks. Estimation is conducted using the feols function, and standard errors are clustered at the country level. Clustering at this level is essential because GDP growth is a macro-regressor repeated across firms within the same country, and the presence of a country variable in the data allows for this robust clustering approach.

2.3.3. Distributional Analysis

To further refine the understanding of fintech valuation dynamics, the analysis is extended to Quantile Regression techniques. While mean-based models focus on average relationships, quantile regression assesses whether these relationships vary across different segments of the valuation distribution. By estimating models at the τ = 0.25, 0.50, and 0.75 quantiles, the study can determine whether the impact of market capitalization or GDP growth differs between firms with lower values and firms with higher values. This distributional perspective is vital for fintech firms, as investor sentiment may exert disproportionate influence depending on the firm’s position in the valuation hierarchy. Statistical inference in these models is based on bootstrapped robust standard errors with 500 iterations to ensure the reliability of the quantile-specific coefficients.

2.3.4. Diagnostic Tests and Model Validity

To ensure the credibility of the findings, a comprehensive set of diagnostic checks is conducted the results are summarized in Table 2. For the Panel ARDL estimations, panel unit root tests based on the Im–Pesaran–Shin (IPS) procedure are used. The IPS results confirm that all variables, including PE Ratio (Wtbar = −3.313), PB Ratio (Wtbar = −3.421), PS Ratio (Wtbar = −4.1525), Market Capitalization (Wtbar = −2.6763), and GDP Growth (Wtbar = −25.883), are stationary with p-values significantly below the 0.01 threshold. These results satisfy the core precondition for the ARDL framework. The choice between MG and DFE estimators is guided by Hausman-type tests. The Hausman test results for P/E (p = 0.7801), P/B (p = 0.1092), and P/S (p = 0.3035) ratios indicate that the models are consistent, supporting the use of the MG estimator. For the fixed-effects interaction models, the explanatory power is assessed using within R-squared values, which for the H3 tests were reported as 0.0863 for P/E, 0.6680 for P/B, and 0.5688 for P/S. The relatively low within R-squared of 0.0863 for the P/E ratio in the H3 interaction model is acceptable given that the empirical objective is hypothesis testing regarding market heterogeneity rather than predictive modeling. Because the two-way fixed-effects specification absorbs a substantial portion of the total variation through firm and time intercepts, the within R-squared only reflects the marginal explanatory power of the standardized interaction terms. Given that P/E ratios are inherently driven by volatile market expectations of future profitability, the presence of individually significant interaction coefficients provides sufficient empirical grounds for interpreting the structural differences between developed and developing fintech markets, regardless of the model’s total predictive power.

Table 2.

Panel ARDL Diagnostic and Goodness-of-Fit Summary.

3. Results

The empirical analysis begins with an assessment of the distributional and stationarity properties of the data to ensure the validity of the subsequent econometric estimations. Following the methodology outlined in Section 2.3, Panel Unit Root Tests using the Im-Pesaran-Shin (IPS) procedure were conducted for all primary variables. The results, as detailed in the diagnostic summary, provide strong evidence that the variables are stationary. Specifically, the P/E ratio (Wtbar = −3.313, p < 0.01), P/B ratio (Wtbar = −3.421, p < 0.01), and P/S ratio (Wtbar = −4.1525, p < 0.01) all reject the null hypothesis of a unit root. Similarly, the independent variables, Market Capitalization (Wtbar = −2.6763, p < 0.01) and GDP Growth (Wtbar = −25.883, p < 0.01), exhibit high levels of stationarity. These findings satisfy the fundamental prerequisite for applying the Panel ARDL framework, ensuring that the estimated long-run relationships are not spurious and that the dynamic adjustments are modeled on stable data series.

3.1. Long-Run Dynamic Analysis (Hypotheses 1 and 2)

The core objective of the first phase of analysis was to test Hypothesis 1 (intrinsic factors) and Hypothesis 2 (extrinsic factors) across the full sample using the Panel ARDL framework. The results of the Mean Group (MG) estimator, selected based on its consistency under slope heterogeneity, reveal a robust and significant positive relationship between firm-level scale and market valuation. As shown in Table 3, Market Capitalization exerts a statistically significant positive effect on all three valuation ratios. Specifically, a one standard deviation increase in standardized market capitalization is associated with a 0.393 unit increase in the P/E ratio (p < 0.001), a 0.788 unit increase in the P/B ratio (p < 0.001), and a 0.712 unit increase in the P/S ratio (p < 0.001). These results provide strong empirical support for Hypothesis 1, suggesting that larger fintech firms with greater market dominance and visibility command significantly higher valuation multiples across the Asian markets studied.

Table 3.

Panel ARDL Long-Run Estimates (Mean Group).

In contrast, the impact of macroeconomic conditions, proxied by GDP Growth (Hypothesis 2), appears more nuanced and less uniform. In the aggregate long-run models, GDP Growth does not reach conventional levels of statistical significance for the P/E and P/B models, with coefficients of −0.0558 (p = 0.334) and 0.0489 (p = 0.278), respectively. However, it shows a weakly significant (p = 0.076) positive relationship with the P/S ratio (coefficient = 0.075), indicating that top-line sales valuations may be more sensitive to general economic expansion than earnings or book-value-based metrics. The goodness-of-fit for these models is substantial, with within R-squared values of 0.340 for P/E, 0.756 for P/B, and 0.684 for P/S, confirming that the selected intrinsic and extrinsic factors capture a significant portion of the variance in fintech valuations.

3.2. Testing Cross-Market Heterogeneity (Hypothesis 3)

The second phase of the analysis addressed Hypothesis 3, which posits that the drivers of valuation differ fundamentally between developed and developing markets. To test this, two-way fixed-effects models with interaction terms were implemented, utilizing country-level clustering for standard errors. The results reported in Table 4 provide compelling evidence of structural heterogeneity, as indicated by the significance of the interaction terms between market type and the key valuation drivers. To facilitate economic interpretation of these interaction effects, Table 5 reports the implied marginal effects of market capitalization and GDP growth by market type, calculated from the estimated coefficients. In the developing market cohort, GDP Growth is a primary driver of valuation, showing significant positive coefficients of 0.156 for P/E (p < 0.05), 0.234 for P/B (p < 0.01), and 0.183 for P/S (p < 0.001). This suggests that in emerging economies like China, India, and Indonesia, fintech valuations are highly pro-cyclical and sensitive to the overall economic growth trajectory.

Table 4.

Market Heterogeneity and Interaction Effects (Two-Way FE).

Table 5.

Marginal Effects by Market Type.

However, the interaction term for GDP Growth and Market Type (GDP_x_MT) is significantly negative across all models—−0.219 for P/E (p < 0.05), −0.222 for P/B (p < 0.05), and −0.133 for P/S (p < 0.01). This negative interaction indicates that the positive influence of GDP growth on valuation ratios is significantly attenuated or even neutralized in developed markets. Also, the interaction between Market Capitalization and Market Type (MC_x_MT) is positive, reaching statistical significance in the P/S model (0.816, p < 0.05) and showing a strong marginal effect in the P/B model. These findings confirm Hypothesis 3, revealing that while developing market fintechs are driven by extrinsic economic growth, developed market fintechs (in South Korea, Japan, and Singapore) are more heavily influenced by intrinsic scale and firm size.

The marginal effects analysis further clarifies these structural differences. As summarized in Table 5, the impact of market capitalization on the P/B ratio jumps from 0.095 in developing markets to 0.787 in developed markets, and for the P/S ratio, it moves from −0.119 to 0.696. Conversely, the marginal impact of GDP growth on the P/E ratio is 0.156 in developing markets but becomes slightly negative (−0.062) in developed contexts. This suggests that investors in developed markets prioritize firm-specific winner-takes-all scale advantages, whereas investors in developing markets view fintech as a broader bet on national economic expansion.

3.3. Distributional Asymmetries (Quantile Regression)

To explore whether the drivers of valuation vary across firms with different valuation levels, Quantile Regression was performed at the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles. The results given in Table 6 indicate that the importance of intrinsic scale (Market Capitalization) remains robustly positive across all quantiles for all three ratios, but its magnitude often increases at the upper end of the distribution. For instance, in the P/B ratio model, the coefficient for Market Capitalization rises from 0.615 at the 25th quantile to 0.911 at the 75th quantile (p < 0.001 for both). This suggests that for highly valued fintech firms (those in the 75th percentile), increasing firm size and market dominance yield a disproportionately larger boost to their valuation multiples compared to firms in the lower valuation quantile.

Table 6.

Quantile Regression Results.

The impact of GDP growth and market interactions also shows distributional sensitivity. In the P/E ratio model at the 25th quantile, GDP growth has a significant negative effect (−0.075, p < 0.001), but its interaction with market type is positive and significant (0.107, p < 0.001), suggesting that for firms in the lower valuation quantile, the market context significantly alters the impact of macroeconomic shocks. In the P/S ratio model, the interaction between GDP and Market Type remains positive and highly significant across all quantiles (0.210 at τ = 0.25; 0.205 at τ = 0.50; 0.237 at τ = 0.75), emphasizing that the differential sensitivity to economic conditions between market types is a persistent feature of fintech sales-based valuations, regardless of whether a firm is currently in the lower or upper valuation quantile.

The results provide a comprehensive validation of the proposed hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 is confirmed by the consistently positive and significant impact of market capitalization across all models. Hypothesis 2 is partially supported, with its significance appearing more prominently in developing markets and sales-based ratios. Hypothesis 3 is strongly supported by the interaction and marginal effects analysis, which demonstrates that developed markets are more firm-scale driven while developing markets are macro-growth driven. These findings suggest that the fintech valuation landscape in Asia is not monolithic; rather, it is characterized by distinct regional regimes where investors weigh intrinsic and extrinsic information differently based on the stage of economic and market development.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide a comprehensive understanding of the valuation landscape for fintech firms in Asia, reinforcing the notion that these entities are not valued in a vacuum but are subject to a complex interplay of internal scale and external economic environments. The results broadly validate the proposed theoretical framework, confirming that market capitalization (intrinsic) and GDP growth (extrinsic) are fundamental drivers of fintech valuation, though their influence is significantly moderated by the stage of market development. This section reconciles these empirical outcomes with existing literature, explores the underlying reasons for observed patterns, and contextualizes the results through specific firm-level examples from the developed and developing market cohorts.

4.1. Intrinsic Drivers and the Scale-Valuation Link

The study identified a robust, positive relationship between market capitalization and valuation ratios (P/E, P/B, and P/S) across the entire sample, confirming Hypothesis 1. This aligns with classical valuation theory, which suggests that larger firms often command higher multiples due to their perceived stability, lower risk premiums, and greater informational visibility. Our findings are consistent with previous research by Fan and Liu (2005), who show that market capitalization reflects more than mechanical firm size, embedding market expectations associated with growth opportunities and risk. It also aligns with Jreisat et al. (2021), who highlighted the challenges of applying traditional valuation methods to fast-growing and innovative fintech firms, suggesting that scale initially enhances valuation but may exhibit diminishing effects as growth opportunities mature.

The agreement with traditional literature is interesting because fintech firms are often characterized by high intangible assets and rapid, non-linear growth trajectories. Within our sample, market capitalization continues to exhibit a strong and statistically significant association with valuation stability, suggesting that scale remains a central valuation signal even in digital-first financial services. This pattern is especially evident for firms such as DBS Group Holdings (Singapore) and Shinhan Financial Group (South Korea). As large, digital-first universal banks in developed markets, their significant market capitalization correlates with high valuation stability because investors view their massive digital infrastructure and customer bases as a competitive advantage that protects future earnings. This winner-takes-all effect is further supported by our quantile regression results, which showed that the positive impact of scale is even more pronounced for firms in the 75th valuation percentile.

4.2. Extrinsic Drivers and the Macroeconomic Sensitivity of Developing Markets

A pivotal finding of this study is the pronounced sensitivity of fintech valuations to GDP growth in developing markets, which contrasts with the more attenuated relationship found in developed economies. While previous studies, such as those by Ha (2021) and Ampedu et al. (2025), generally posit that GDP growth signals macroeconomic expansion and improved profitability, our results show that this transmission is highly context-dependent. Although this is consistent with prior evidence that economic growth influences firm valuation through digital intangibles and intellectual capital accumulation rather than uniformly across valuation metrics (D. Liu et al., 2009; Di Marcantonio et al., 2015). In emerging economies like China, India, and Indonesia, fintech is often viewed as a complementary force to traditional banking, driving financial inclusion and capturing the benefits of a growing middle class.

For instance, Central Depository Services Ltd. (CDSL) in India and Bank Neo Commerce in Indonesia have valuations that are deeply intertwined with national economic expansion. In these markets, rapid GDP growth correlates with a surge in retail investor participation and digital transaction volumes, directly boosting valuation multiples. This contrasts with developed markets like Japan, where fintech may act as a substitute for traditional services in a more saturated environment, leading to a weaker link between general GDP growth and fintech-specific valuations. The disagreement with universal positive GDP-valuation models in developed contexts likely stems from the fact that these markets are driven more by global financial factors and institutional stability rather than local cyclical fluctuations.

4.3. Structural Heterogeneity: Developed vs. Developing Market Regimes

The confirmation of Hypothesis 3 that market type moderates the relationship between valuation drivers is perhaps the most significant contribution of this study. Our results demonstrate a clear regime split: developed markets are firm-scale driven, whereas developing markets are macro-growth driven. This finding is supported by the research of Cevik (2025) and Sarkar (2020), who show that in emerging economies, valuation outcomes are dominated by local economic dynamics and heightened macro-financial risk rather than firm-specific fundamentals. Noviantoro et al. (2020) similarly emphasize that regional and institutional dynamics play a decisive role in shaping fintech valuations, reinforcing the presence of distinct valuation regimes across markets.

In developed markets like Singapore and Japan, firms like GMO Payment Gateway and OCBC Bank operate within stable institutional frameworks and mature capital markets. Here, the cost of capital is lower, and valuations reflect long-term earnings expectations rather than immediate economic shocks. Consequently, the intrinsic scale of a firm like GMO Payment Gateway is a far better predictor of its P/S ratio than the prevailing GDP growth rate in Japan. Conversely, in the developing market cohort, firms like Sunline Technology (China) or Infibeam Avenues (India) are highly responsive to extrinsic growth. For these firms, GDP growth serves as a proxy for the speed of digital transformation and the expansion of the addressable market, which is the primary driver of their valuation multiples.

The reasons for this disagreement in drivers lie in the maturity of the financial infrastructure. In developing markets, fintech adoption is transformative, creating new value where none existed before (e.g., through financial inclusion), making it hyper-sensitive to the broader economic environment. In developed markets, fintech is often an incremental improvement in efficiency, making its valuation more dependent on the firm’s specific competitive position and scale.

4.4. Distributional Insights and Investor Strategy

Our quantile regression analysis provided additional granularity, revealing that the drivers of valuation shift as a firm moves up the valuation hierarchy. For fintech firms in the lower valuation quantile (25th percentile), macroeconomic indicators like GDP growth can sometimes have a negative initial impact, possibly reflecting the high transitional costs or the distress associated with economic shifts in less stable markets. However, for fintech firms in the upper valuation quartile (75th percentile), market capitalization becomes a powerful force for valuation expansion.

This reflects the market’s tendency to reward scalability and digital intangibles in firms that have already proven their model. Firms like Ping An Insurance (China), which maintains a massive integrated finance + healthcare model, demonstrate how scaling diverse digital services can sustain high valuation multiples even when facing regulatory or margin pressures. This aligns with the work of Moro-Visconti (2020), who highlighted that the valuation of digital intangibles, such as the proprietary algorithms used by firms like Douzone Bizon (South Korea) for SME finance, becomes a critical component of value as firms mature and scale.

The valuation of Asian fintech firms is characterized by a fundamental duality. Investors in developed markets (Singapore, Japan, South Korea) adopt a scale-centric lens, placing greater weight on firm size and valuation stability, as reflected in the relatively steady multiples of firms such as DBS Group Holdings and Shinhan Financial Group. Meanwhile, investors in developing markets (China, India, Indonesia) use a growth-centric lens, where the valuation of firms like CDSL or Bank Neo Commerce acts as a leveraged bet on the country’s economic trajectory.

These findings suggest that a universal valuation model for fintech is likely to be flawed. Instead, market participants must calibrate their expectations based on the market’s development status, which focuses on firm-specific scale and innovation in developed contexts, as well as macroeconomic health and financial inclusion potential in developing regions. By reconciling these differences, this study provides a robust empirical foundation for navigating the diverse and rapidly evolving fintech landscapes of Asia.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive empirical investigation into the valuation dynamics of the Asian fintech sector, examining the intricate relationship between intrinsic firm-level scale and extrinsic macroeconomic growth. By analyzing 30 leading fintech firms across six diverse Asian economies, our research reconciles traditional valuation theory with the unique characteristics of digital-first entities. The findings validate a fundamental transition in how market participants evaluate technology-driven financial services, moving away from a one-size-fits-all approach toward a more nuanced, regime-specific understanding of value creation.

The primary contribution of this study lies in identifying the structural duality that defines the Asian fintech landscape. Our application of the Panel ARDL framework and two-way fixed-effects models confirms that while intrinsic scale, proxied by market capitalization, is a robust long-run anchor for valuation multiples across all markets. Its influence is particularly dominant in developed economies like South Korea, Japan, and Singapore. In these mature markets, investors prioritize a scale-centric lens, rewarding firms that have established significant perceived digital dominance and platform scale reflected in their market capitalization and institutional stability. Conversely, in developing markets such as China, India, and Indonesia, valuations are profoundly macro-growth driven. In these contexts, fintech firms like CDSL and Bank Neo Commerce are valued by the market as leveraged exposures to national economic expansion, with their valuation multiples exhibiting high sensitivity to GDP growth.

Further, our quantile regression analysis unveils critical distributional asymmetries, revealing a winner-takes-all phenomenon. The positive impact of firm scale on valuation ratios like P/B and P/S is significantly more pronounced for firms in the 75th valuation percentile compared to those at the 25th percentile. This suggests that once a fintech firm achieves market dominance, its ability to scale digital intangibles, such as proprietary algorithms and customer data, yields disproportionately higher market rewards. These insights are vital for investors who must distinguish between the cyclical growth of emerging firms and the structural scale of market leaders.

From a policy perspective, the study highlights that effective scaling is the most critical driver of sustainable market value. To maintain regional competitiveness, policymakers should prioritize regulatory frameworks that facilitate capital market access and promote digital infrastructure, especially in developing economies where fintech acts as a catalyst for financial inclusion. Additionally, the emerging relevance of ESG factors and intellectual capital, including patents and human resources, must be integrated into future valuation frameworks to reflect the holistic value of fintech innovation.

Despite its rigorous multi-method approach, this study acknowledges limitations concerning sample size and sub-sector diversity. Future research should extend this longitudinal analysis to include emerging fintech hubs in Africa and Europe, while also exploring the specific valuation impact of disruptive technologies like blockchain and decentralized finance.

Ultimately, this study signals a shift away from purely speculative narratives in fintech valuation, demonstrating that fintech is not merely a digital extension of traditional banking but a structural economic shift with distinct regional regimes. By demonstrating that valuation drivers are context-dependent, shifting from macro-sensitivity in emerging markets to scale-dominance in developed ones, this study provides the navigational map necessary for global stakeholders to move from speculative hype to fundamental financial clarity in the digital age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.P. and R.S.; data curation, A.J.; formal analysis, A.J. and P.S.; investigation, A.J. and S.B.; methodology, N.P. and A.J.; project administration, A.J.; resources, N.P.; software, A.J. and S.B.; supervision, N.P.; validation, N.P., R.S., P.S., A.J. and S.B.; visualization, A.J. and S.B.; writing—original draft, N.P., R.S. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, A.J. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Ayushi Mehta and Bhavna Yadav, MBA students (2024–2026), Symbiosis School of Banking and Finance, Symbiosis International (Deemed University), Pune, India, in coordinating the research study. During the preparation of this work, the authors used OpenAI ChatGPT 4o in order to brainstorm ideas and harmonize text. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| Country | Company | Ticker | Primary Business | Key Metrics | Insights |

| China | Ping An Insurance | 2318.HK (HKEX) | Integrated insurance–banking conglomerate | Q1 2025 revenue ¥256.6 B and net income ¥35.2 B; serves >220 M customers. | Pursues an “Integrated Finance + Healthcare” model to cross-sell insurance and health-care services, maintaining strong capital buffers. |

| China | Hundsun Technologies | 600570.SH (SSE) | Core trading, asset-management and banking software provider | Serves >2000 financial institutions; Q3 2025 revenue ¥1.063 B (down vs. expectations) with 71.67% TTM gross margin. | Transitioning toward SaaS subscriptions to stabilize earnings despite slower license sales. |

| China | Sunline Technology | 300348.SZ (SZSE) | Core banking systems and cloud-native IT solutions | Q3 2025 net profit ¥7.71 M, up 259.7% YoY; expanding into Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. | Captures demand for cloud-native core banking as smaller lenders replace legacy mainframes. |

| China | Lakala Payment | 300773.SZ (SZSE) | Third-party payment and merchant services provider | 9M 2025 net profit ¥339 M, down 33.9% YoY. | To offset margin pressure it plans asset sales and a Hong Kong listing to fund international expansion. |

| China | PAX Global Technology | 327.HK (HKEX) | Manufacturer of Android-based POS terminals and payment software | H1 2025 revenue HK$2.716 B and net profit HK$391.4 M; gross margin 46.9%. | Future-proofing terminals by adding stablecoin settlement capabilities in response to new HK/US regulations. |

| South Korea | Shinhan Financial Group | 055550.KS (KRX) | Universal banking group offering retail, corporate and investment services | H1 2025 net profit ₩3.04 T (+10.6% YoY) and Q3 net profit ₩4.46 T; Super SOL app unifies banking, card and brokerage. | Leads digital banking; its “AX-Ignition” strategy uses AI for credit scoring and plans AI/stablecoin wealth management. |

| South Korea | KG Inicis | 035600.KQ (KOSDAQ) | Payment-gateway operator and account-to-account transfer provider | FY 2024 revenue ₩1.354 T with ROE 8.67%; 12-month net profit ₩33.7 B. | Dominates Korean online payments and is expanding A2A transfer technology to lower card costs. |

| South Korea | Danal Co., Ltd. | 064260.KQ (KOSDAQ) | Mobile-payment and carrier-billing services | TTM revenue ₩226 B and net loss ₩43.8 B. | Pivoting to quantum-secure and crypto-asset payments after carrier-billing profits decline. |

| South Korea | Hecto Financial | 234340.KQ (KOSDAQ) | Provider of virtual accounts and bulk-transfer payment services | FY 2024 revenue ₩159.31 B; TTM revenue (Sep 2025) ≈ US$128 M with net income US$5.5 M. | Key cash-payment alternative for gig-economy platforms; enables large-scale bulk transfers. |

| South Korea | Douzone Bizon | 012510.KS (KOSPI) | SME ERP vendor turned cloud-based financial-intelligence platform | FY 2024 revenue ₩402.33 B (+13.45% YoY); Q3 2025 revenue ₩114.67 B (+18.17% YoY). | Partnering with AWS and Anthropic to integrate AI; expanding globally via Gennolab to provide AI-driven SME finance. |

| India | HDFC Bank | HDFCBANK.NS (NSE) | Large private-sector bank providing retail and corporate banking | Q2 FY26 standalone PAT ₹18,640 Cr (+10.8% YoY); half-year revenue ₹1.90 L Cr; CASA deposits ₹8.77 L Cr (+8.5%) and CD ratio 98.5%. | Post-merger strategy focuses on mobilizing low-cost deposits and managing credit-deposit ratio while expanding SME lending. |

| India | CAMS (Computer Age Management Services) | 543232.BSE (BSE) | Mutual-fund transfer agent and fintech infrastructure provider | Q2 FY26 revenue ₹376.74 Cr; handles 68% of India’s MF RTA market and serviced AUM ₹52 L Cr; non-MF revenue >14%. | Dominant mutual-fund infrastructure player; expanding payment-aggregator arm CAMSPay. |

| India | Central Depository Services Ltd. (CDSL) | CDSL.NS (NSE) | Securities depository; maintains demat accounts and settlement systems | >16.51 Cr demat accounts by late 2025, adding 65 L accounts in Q2 FY26; Q2 net profit ₹140.21 Cr. | Monopolistic depository benefiting from retail investor boom, ensuring stable cash flows. |

| India | Indian Energy Exchange (IEX) | 540750.BSE (BSE) | Power and gas trading exchange | Q2 FY26 PAT ₹123.35 Cr, up 13.9%, with EBIT margin ≈85%. | Maintains monopoly in energy trading and is expanding into gas and carbon trading. |

| India | Infibeam Avenues | INFIBEAM.NS (NSE) | AI-powered payment and commerce platform (CCAvenue) | Q2 FY26 gross revenue ₹1964.9 Cr (+93% YoY); adjusted EBITDA +10%; PAT ₹65 Cr (+18%). | Transforming into an AI-driven fintech; launching CCAvenue CommerceAI; scaling internationally and preparing GIFT City operations. |

| Japan | SBI Holdings | 8473.T (TSE) | Diversified financial conglomerate with banking, brokerage, asset management and crypto businesses | FY 2025 revenue ¥1.443 T (+19.3%) and profit attributable to owners ¥162.12 B (+85.8%); crypto-asset division revenue ¥80.79 B (+41.4%). | Pursuing integrated finance and blockchain investments; benefiting from retail uptake via the new NISA scheme. |

| Japan | GMO Payment Gateway (GMO-PG) | 3769.T (TSE) | Online payment gateway processing credit-card and BNPL transactions | FY 2025 revenue ¥82.499 B and operating profit ¥31.34 B with 20.2% ROE and 38% operating margin. | High-margin SaaS-based payment processor scaling with Japan’s e-commerce and BNPL boom. |

| Japan | GMO GlobalSign Holdings | 3788.T (TSE) | Digital trust and cybersecurity services (SSL/TLS, e-signature) | Q2 2025 sales reached a record high; the “GMO Sign” e-contract service grew 40.3%. | Pivoting to digital trust and post-quantum cryptography, ensuring secure identity and signature solutions. |

| Japan | Monex Group | 8698.T (TSE) | Online brokerage and asset-management group | Q2 FY 2026 pre-tax income ¥4.719 B with AUM ¥10 T. | Recovering from restructuring; partnership with NTT DOCOMO attracts younger investors via “Easy Asset Management”. |

| Japan | Mercari, Inc. | 4385.T (TSE) | Peer-to-peer marketplace with integrated payments (Merpay & BNPL) | FY ended 30 June 2025 revenue ¥192.633 B and core operating profit ¥27.574 B; Merpay processes >US$4 B GMV. | Embedding credit and BNPL into its marketplace via Merpay, turning C2C commerce into a fintech ecosystem. |

| Singapore | DBS Group Holdings | D05.SI (SGX) | Digital-first universal bank offering retail, corporate and wealth services | 9M 2025 total income S$17.6 B (+5% YoY); five-year total return 166% and forecast dividend yield 6.1%. | Continues to outperform due to strong fee and deposit growth; digital transformation remains a competitive moat. |

| Singapore | OCBC Bank | O39.SI (SGX) | Universal bank with major wealth-management and insurance operations | 9M 2025 net profit S$5.68 B; wealth management AUM S$336 B accounting for 43% of total income. | Leveraging Great Eastern insurance franchise; strong non-interest income growth and record wealth AUM. |

| Singapore | UOB Bank | U11.SI (SGX) | Regional bank focusing on retail and corporate banking | FY 2024 net profit S$6.0 B; Q3 2025 net profit plunged 72.5% due to higher credit provisions. | Integrating Citi ASEAN assets to drive long-term synergies despite short-term credit-loss volatility. |

| Singapore | iFAST Corporation | AIY.SI (SGX) | Digital wealth-management and e-pension platform | Q3 2025 net profit S$26 M (+54.7%); net inflows Jan–Sep 2025 S$3.71 B; iFAST Global Bank profitable for first full year. | High-growth wealth-tech firm; Hong Kong ePension and global bank operations driving profitability. |

| Singapore | Silverlake Axis | 5CP.SI (SGX) | Provider of core banking software and digital banking solutions | FY ended Jun 30 2024 revenue RM 783.5 M and net profit RM 105.2 M. | Focuses on recurring maintenance contracts; faces competition from cloud-native systems like Sunline. |

| Indonesia | Bank Neo Commerce (BNC) | BBYB.JK (IDX) | Mobile-first digital bank offering savings and loans | 9M 2025 net profit IDR 464 B after turnaround from losses; “Neo Loan” lending product grew 139% YoY. | Achieved profitability through high-yield digital lending; benefits from integration with the Akulaku ecosystem. |

| Indonesia | Allo Bank Indonesia | BBHI.JK (IDX) | Digital bank integrated with CT Corp’s retail and Bukalapak platforms | FY 2024 net profit IDR 467.11 B; continued growth through late 2025. | Leverages CT Corp’s retail reach and Bukalapak e-commerce to cross-sell digital banking and credit. |

| Indonesia | Bank Raya Indonesia | AGRO.JK (IDX) | Digital micro-lender and subsidiary of Bank Rakyat Indonesia | 9M 2025 net profit IDR 41.9 B (+23.8%); digital lending outstanding IDR 20.61 T. | Provides digital lending to MSMEs and gig-economy workers; backed by BRI’s distribution network. |

| Indonesia | M Cash Integrasi | MCAS.JK (IDX) | Operator of digital kiosks and app-based payment/voucher services | FY 2024 sales IDR 7.1 T but net loss IDR 35.3 B; invests in start-ups like SiCepat Express. | Building a physical-to-digital bridge for Indonesia’s unbanked via kiosk network; short-term losses reflect expansion costs. |

| Indonesia | Bank Central Asia (BCA) | BBCA.JK (IDX) | Leading private bank with advanced digital channels | First 10 months of 2025 net profit IDR 48.25 T (+4.4%); digital transactions reached 36 B in 2024 and customer base 33.1 M. | Indonesia’s most valuable bank with unmatched digital transaction volume; sets benchmark for mobile and internet banking adoption. |

References

- Adhikari, P., Hamal, P., & Jnr, F. B. (2024). Artificial Intelligence in fraud detection: Revolutionizing financial security. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 13(1), 1457–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampedu, R., Wang, X., & Mensah, R. (2025). Investigating the role of economic factors in shaping stock market trends in Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 13(1), 2555418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaut, D., & Bećirović, D. (2023). FinTech innovations as disruptor of the traditional financial industry. In S. Benković, A. Labus, & M. Milosavljević (Eds.), Digital transformation of the financial industry: Approaches and applications (pp. 233–254). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevik, S. (2025). Is Schumpeter right? Fintech and economic growth. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 34(7), 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R., Mahdy, M. R. C., Alam, T. N., Al Quaderi, G. D., & Arifur Rahman, M. (2020). Predicting the stock price of frontier markets using machine learning and modified Black–Scholes Option pricing model. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications, 555, 124444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christofi, K., Chourides, P., & Papageorgiou, G. (2024). The role of knowledge assets and corporate social responsibility in creating firm value. Knowledge and Performance Management, 7(1), 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z., Kirkby, J. L., & Nguyen, D. (2021). A data-driven framework for consistent financial valuation and risk measurement. European Journal of Operational Research, 289(1), 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, A. (2012). Investment valuation: Tools and techniques for determining the value of any asset. John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Di Marcantonio, M., Laghi, E., & Mattei, M. (2015). Does intellectual capital affect business performance? Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing, 11(10), 515–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X., & Liu, M. (2005). Understanding size and the book-to-market ratio: An empirical exploration of berk’s critique. Journal of Financial Research, 28(4), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N. P. (2021). Impact of macroeconomic factors and interaction with institutional performance on Vietnamese bank share prices. Banks and Bank Systems, 16(1), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. J., & Kim, H.-J. (2021). Stock price prediction using multiple valuation methods based on artificial neural networks for KOSDAQ IPO companies. Investment Analysts Journal, 50(1), 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jreisat, A., Bashar, A., Alshaikh, A., Rabbani, M. R., & Ali, M. A. M. (2021, December 7–8). Is fintech valuation an art of science? Exploring the innovative methods for the valuation of fintech startups. 2021 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA) (pp. 922–925), Sakheer, Bahrain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabulova, J., & Stankevičienė, J. (2020). Valuation of FinTech innovation based on patent applications. Sustainability, 12(23), 10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., & Zhang, X. (2024). Digital finance development in China: A scientometric review. Heliyon, 10(16), e36107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D., Tseng, K., & Yen, S. (2009). The incremental impact of intellectual capital on value creation. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 10(2), 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Nissim, D., & Thomas, J. (2002). Equity valuation using multiples. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1), 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. (2024). The role of big data in financial technology toward financial inclusion. Frontiers in Big Data, 7, 1184444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moro-Visconti, R. (2020). The valuation of digital intangibles: Technology, marketing and internet. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro-Visconti, R., Rambaud, S. C., & Pascual, J. L. (2020). Sustainability in FinTechs: An explanation through business model scalability and market valuation. Sustainability, 12(24), 10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviantoro, R., Fahlevi, M., & Abdi, M. N. (2020). Startup valuation by venture capitalists: An empirical study Indonesia firms. International Journal of Control and Automation, 13(2), 785–796. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, A. (2023). Valuation versus pricing: A conceptual and practical guide to estimate economic value for early-stage companies via DCF. In Contributions to finance and accounting (Vol. Part F1460, pp. 67–102). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A. (2020). Understanding the short run relationship between stock market and growth in emerging economies. Journal of Quantitative Economics, 18(2), 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil. (2016). Strategic flexibility in ecosystem. Global Journal of Flexible Systems Management, 17(3), 247–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. S. (2024). Funding startups using contingent option of value appreciation: Theory and formula. China Finance Review International, 14(1), 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawarna, R., Miah, S. J., & Shao, X. (2023). Emerging advances of blockchain technology in finance: A content analysis. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 27(4), 1495–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H., Gao, Y., & Zhang, J. Z. (2023). Understanding the adoption context of China’s digital currency electronic payment. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.