Abstract

This study investigates the influence of major regulatory interventions on decentralised finance (DeFi) token markets by conducting an event study of six high-profile announcements issued between 2023 and 2025. The analysis reveals that these interventions primarily lead to risk-sensitive, token-specific price adjustments rather than systemic disruptions across the broader DeFi ecosystem. While enforcement actions trigger asymmetric and delayed volatility effects, legal clarity alone does not stabilise liquidity conditions. Notably, governance and decentralised exchange (DEX) tokens exhibit heightened sensitivity to enforcement actions and policy signals, underscoring the role of protocol function in regulatory risk transmission. These results contribute to the literature on market microstructure in decentralised ecosystems and offer practical insights into liquidity formation, volatility persistence, and differentiated risk management within emerging fintech infrastructures.

1. Introduction

Decentralised Finance (DeFi) represents a fundamental transformation in the provision of financial services, enabling lending, trading, derivatives, and asset management through smart contracts deployed on public blockchains. By eliminating traditional intermediaries, DeFi protocols allow users to retain direct control over their assets while interacting through algorithmic mechanisms such as automated market makers, collateralised lending pools, and decentralised governance systems. These features have positioned DeFi as a prominent component of the broader digital asset ecosystem, offering efficiency gains but also introducing novel sources of financial and operational risk.

Driven by the promise of openness and efficiency, DeFi markets have experienced rapid growth. Total Value Locked (TVL) surged from approximately USD 700 million in 2020 to over USD 150 billion by April 2022 (Werner et al., 2022). As of 12 August 2025, DeFi’s market capitalisation remained resilient at USD 149.84 billion, despite broader downturns in the cryptocurrency sector post-May 2022 (Raynor, 2025). This proliferation, however, has not been without consequences. The features that enable DeFi’s openness also introduce new forms of risks. In addition to conventional financial volatility, DeFi presents additional risks such as smart contract vulnerabilities, oracle manipulation, liquidity crises, flash loan attacks, and governance deficiencies (Adamyk et al., 2025; Weingärtner et al., 2023). His expansion has intensified regulatory scrutiny, as authorities seek to address risks related to consumer protection, market integrity, financial stability, and illicit activity. Regulatory responses have taken multiple forms, including binding legislative frameworks, targeted enforcement actions, and non-binding policy guidance issued by domestic and international authorities.

Existing research has largely examined regulation in the context of cryptocurrencies more broadly, with most work focusing on Bitcoin and Ethereum. Auer and Claessens (2018) focus primarily on Bitcoin and a select group of major cryptocurrencies, demonstrating that adverse regulatory news results in a 3.12% decline in Bitcoin’s 24 h return, whereas favourable news is associated with a 1.52% increase over the same period. Shanaev et al. (2019) conclude that tight regulation reduces cryptocurrency valuations, while hands-off or pro-innovation stances are positively received, indicating that regulation is generally perceived as value-destroying rather than risk-reducing. Feinstein and Werbach (2021) discover that cryptocurrency trading volumes remain largely unaffected by regulatory announcements, while modest but statistically significant price declines are observed in response to anti-money laundering enforcement actions, particularly for Bitcoin and Ethereum. However, we still know relatively little about how regulation affects DeFi tokens in particular. DeFi tokens serve distinct roles within protocol ecosystems, including governance, liquidity provision, price discovery, collateralisation, and stability maintenance. These functional differences imply heterogeneous exposure to regulatory risk, as regulatory actions may affect protocol governance rights, trading activity, or operational feasibility in markedly different ways.

Moreover, regulatory interventions themselves are not uniform. Regulatory events vary in legal force, scope, geographic reach, and degree of enforcement. Legislative frameworks may provide clarity and reduce uncertainty, while enforcement actions may signal heightened compliance risk or legal exposure. Policy guidance may influence expectations without imposing immediate constraints. Treating these diverse interventions as operating through a single, uniform channel risks obscuring important variation in market responses. A coherent analytical framework therefore requires recognising both the heterogeneity of regulatory instruments and the differentiated structure of DeFi token categories.

This study adopts a regulatory transmission perspective, conceptualising regulation as a signal that alters the information environment, perceived compliance costs, and risk profiles of decentralised protocols. Governance and decentralised exchange tokens, which are closely tied to protocol control and trading activity, are expected to be more sensitive to regulatory signals affecting legal accountability and market conduct. In contrast, stablecoins and lending tokens, which rely more heavily on over-collateralisation mechanisms and predefined contract logic, may exhibit greater insulation from short-term regulatory news unless core design features are directly challenged. These transmission channels provide a theoretical basis for anticipating heterogeneous price, volatility, and liquidity responses across token categories.

At the same time, regulatory events cannot always be treated as fully exogenous. In particular, enforcement actions may be influenced by prior market behaviour, protocol growth, or risk accumulation, introducing potential endogeneity. In addition, protocol-level characteristics such as leverage structures, liquidity pool composition, or oracle update frequency may simultaneously affect returns, volatility, and liquidity but are not fully observable at the token level. While the empirical design mitigates these concerns through pre-event windows, robustness checks, and fixed effects, residual endogeneity and omitted variable bias cannot be entirely ruled out and are acknowledged as limitations.

Against this background, this research is guided by the following central question: “How do regulatory announcements and enforcement actions affect price, volatility, and liquidity in DeFi token markets, and do these effects differ by token category and regulatory clarity?” To address this question, we construct a novel dataset covering six major regulatory events between 2023 and 2025 and examine their effects on ten leading DeFi tokens representing decentralised exchanges, lending protocols, governance tokens, stablecoins, oracle providers, and derivatives platforms. The empirical strategy combines event study analysis, GARCH and EGARCH volatility models, and two-way fixed effects panel regressions to capture both short-term market reactions and longer-term risk adjustments.

This study makes three principal contributions. First, it systematically distinguishes between different types of regulatory interventions and demonstrates that regulatory effects are not uniform across DeFi markets. Second, it provides evidence of pronounced heterogeneity across token categories, with governance and decentralised exchange tokens exhibiting stronger and more immediate responses than stablecoins and lending tokens. Third, by integrating return-based event studies with volatility modelling, liquidity analysis, placebo simulations, and structural stability tests, the paper offers a comprehensive and robust assessment of how regulatory risk is transmitted within decentralised financial systems.

The remainder of our paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses relevant literature and develops our hypotheses. Section 3 describes our data sample selection, variable definitions, and study methodology. Section 4 discusses our main empirical findings. Section 5 concludes the paper and proposes recommendations for further studies.

2. Background and Literature Review

2.1. Background

Compared to traditional finance, DeFi presents a distinct set of potential risks that are different in kind and magnitude, requiring the needs for regulations. These are primarily technological vulnerabilities resulting in systems exposed to fraud, security breaches, and systemic failures. These vulnerabilities include smart contract issues, oracle manipulation, and blockchain protocol cracks (Weingärtner et al., 2023). The 2016 DAO attack that resulted in the theft of USD 50 million in Ether (Mehar et al., 2017). Over USD 600 million was stolen from Poly Network in August 2021, in one of the biggest DeFi attacks to date. This included USD 253 million on Binance Smart Chain, USD 266 million in Ethereum tokens, and USD 85 million in USDC on Polygon (Locke, 2021). The lack of regulatory protections frequently makes DeFi more vulnerable to serious financial and market risks like excessive leverage, counterparty failures, liquidity crises, and high volatility (Bertomeu et al., 2024; Carter & Jeng, 2021). According to Bertomeu et al. (2024), DeFi lending protocols demonstrated extreme fragility during times of heightened stress, particularly in mid-2021 and November 2022. Even slight price declines (10–30%) could lead to widespread liquidations and collateral shortages, and lenders frequently faced residual losses due to the imperfection of liquidation mechanisms. This underscores the fact that over-collateralisation and algorithmic safeguards cannot completely eliminate systemic risk, and that vulnerabilities similar to traditional banking fragility still exist, underscoring the need for stronger risk management and governance structures (Adamyk et al., 2025; Zetzsche et al., 2020; Wronka, 2021). This also raises the issue for governance bodies of promoting financial innovation while protecting investors from potential risks.

2.2. Event Study

The analysis of regulatory events in financial markets relies fundamentally on the Event Study methodology, which measures the impact of public information on asset prices by isolating the effect around the event date. This technique allows for the empirical determination of whether an event, such as regulatory announcements or enforcement actions, elicit statistically significant market reactions. Importantly, this technique has been increasingly adapted to the digital asset domain, offering a rigorous means to evaluate how regulatory signals influence cryptocurrency and DeFi token valuations (Guseva & Hutton, 2023; Puławska, 2025).

Furthermore, our analysis of liquidity and trading volume requires grounding in Market Microstructure theory. Traditional finance literature establishes that market efficiency and information asymmetry affect transaction costs, often proxied by the bid-ask spread or trading volume. Higher transaction costs deter market participation (Amihud & Mendelson, 1986). Conversely, models of information asymmetry and speculative trading suggest that price uncertainty and return shocks are often positively correlated with volume, as traders increase activity in response to new, often high-risk, information (Easley & O’Hara, 1987). This microstructural framework validates our approach of not only measuring price reactions (CARs) but also modelling liquidity dynamics to assess the depth and resilience of the market under regulatory stress.

2.3. GARCH and EGARCH Models

Prior research has widely employed Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) models to capture the dynamics and persistence of financial market volatility, beginning with foundational contributions by Engle (1982) and Bollerslev (1986). In the context of cryptocurrency markets, GARCH models have proven effective in modelling volatility clustering, wherein large price movements tend to be followed by similarly large fluctuations, regardless of direction (Katsiampa, 2017). Cumming et al. (2025)further suggest that clearer regulatory regimes can dampen volatility, while Dyhrberg (2016) highlights the asymmetric nature of volatility responses to market shocks. Collectively, these findings underscore that regulatory interventions can destabilise markets in the short term while potentially contributing to longer-term systemic stability.

To account for such asymmetries in volatility behaviour, we also employ the Exponential GARCH (EGARCH) model introduced by Nelson (1991). EGARCH is particularly well-suited to modelling volatility responses that differ depending on the sign and magnitude of return shocks. Prior studies including Aliyev et al. (2020), Dyhrberg (2016), and Alim et al. (2024) demonstrate the model’s effectiveness in capturing the asymmetric and event-driven volatility patterns across financial assets. Building on this literature, our study applies the EGARCH framework specifically to DeFi tokens, aiming to assess whether regulatory announcements induce short-term volatility spikes and whether these effects vary by the type and tone of the announcement. In line with the above discussion, we test the following hypotheses:

H1a.

Regulatory enforcement actions increase short-term return volatility in DeFi tokens.

H1b.

Negative regulatory events produce stronger volatility shocks than positive events.

H1c.

Enforcement actions reduce liquidity in DeFi markets.

2.4. Policy Uncertainty Theory

Policy Uncertainty Theory posits that financial markets respond not only to underlying fundamentals but also to the broader regulatory and policy environment. Previous research in traditional finance shows that regulatory uncertainty tends to elevate market volatility in the short term, while greater clarity can reduce uncertainty and improve market stability over time (Pastor & Veronesi, 2012; Chiang, 2020). In the context of cryptocurrency markets, research by Corbet et al. (2018) provides empirical support for this view, finding that regulatory announcements often trigger volatility spikes, whereas Auer and Claessens (2018) demonstrate that the introduction of clear and coherent frameworks enhances investor confidence and reduces risk premia. This theoretical framework is relevant to the DeFi sector, where uncertainty regarding jurisdictional scope, compliance obligations, and legal classifications can increase perceived risk and discourage participation. Conversely, the introduction of structured and transparent regulatory regimes has the potential to anchor investor expectations and promote market maturity. To operationalise this theory, our study categorises regulatory announcements based on their substance and legal clarity. We then evaluate whether market responses differ between events that introduce broad regulatory frameworks and those that contribute to piecemeal or uncertain legal environments. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2.

Regulatory clarity reduce volatility and improve liquidity in DeFi token markets over medium-term windows.

H3.

The effects of regulatory announcements varies across DeFi token categories, with stablecoins exhibiting lower sensitivity in terms of volatility and liquidity response than governance tokens, DEX tokens, or lending protocols.

2.5. Behavioural Finance

Behavioural finance refers to the psychology of investors and its function in financial investment decisions (Kapoor & Prosad, 2017). The theory argues that such decisions can be inefficient and irrational, potentially driving bubbles and contagion effects in financial market, featuring dramatic fluctuations in prices, volumes and volatility (Ballis & Verousis, 2022). Given the expansion of blockchain ecosystem, market participants often respond swiftly and emotionally to the antifraud actions, triggering shifts in volatility, liquidity, and asset returns. Cumming et al. (2025) that cryptocurrency investors exhibit short-term negative reactions to regulatory announcements, with significant cumulative abnormal returns (CAR), suggesting behavioural overreactions and market inefficiency. Investors can overreact to policy news due to limited rationality and noise trading, leading to aggregate mispricing and bubble behaviour (Al-Mansour, 2020). Under the lens of behavioural finance, we aim to examine whether the initial market reaction to different event classifications is driven by fear and overreaction or by a rational assessment of the policy’s long-term benefit. This leads to our following hypothesis:

H4.

Regulatory announcements induce significant spikes in volatility consistent with investor overreaction and behavioural noise.

2.6. Empirical Context and Contribution

Recent event studies have begun to map the regulatory landscape surrounding digital assets. Puławska’s (2025) analysis measures abnormal changes in blockchain and market indicators around regulatory and non-regulatory milestones. The results show that Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) events in 2023 produced significant negative price reactions and mixed transactional effects, while broader anomalies confirm that crypto markets remain highly sensitive to regulatory, macroeconomic, and sentiment-driven shocks, reflecting fragility rooted in behavioural rather than structural dynamics. U.S. financial regulation of crypto-assets is fragmented between the SEC, which enforces securities laws, and the CFTC, which oversees commodities and derivatives. Using an event study of 116 enforcement actions between 2017 and 2021, Guseva and Hutton (2023) examine abnormal returns around announcement dates to assess market reactions. They find that enforcement actions generally depress crypto-asset prices, with SEC actions triggering significantly stronger negative reactions than CFTC actions, while antifraud cases elicit more positive responses by improving market integrity. The results highlight that regulatory interventions exert heterogeneous effects, with enforcement actions generally depressing prices but antifraud cases improving confidence, underscoring the dual role of regulation as both a source of short-term disruption and a mechanism for long-term market integrity.

Despite these contributions, the existing body of literature lacks a comprehensive, multi-faceted exploration of how different regulatory enforcements or actions, coupled with the precise classification of regulatory events, influence the combined reaction of price, volatility, and liquidity specifically for DeFi tokens. By applying a unique combination of Event Study Methodology (for price), GARCH and EGARCH modelling (for risk/volatility), and a Market Microstructure model (for liquidity), our research addresses three primary gaps. First, by rigorously classifying events as either clarity-enhancing (such as framework announcements and legislative proposals) or integrity-enforcing (such as targeted enforcement actions), our study allows for a more nuanced analysis of the differential effects anticipated by both Policy Uncertainty Theory and Behavioural Finance. Second, DeFi tokens vary widely in their structure and functionality; thus, we disaggregate our sample into distinct categories to assess whether market sensitivity is conditioned by token utility and risk profile. Finally, we provide an integrated empirical framework that simultaneously examines abnormal returns (ARs/CARs), conditional volatility (GARCH/EGARCH), and liquidity dynamics (volume, bid–ask spreads, Amihud illiquidity), offering a comprehensive view of how regulation affects DeFi markets across multiple dimensions. Given the above argument, we test the following hypothesis:

H5:

Consistent and predictable regulation reduces systemic risk in DeFi token markets.

3. Research Design

3.1. Event Study Methodology

This study employs the event study methodology to investigate the impact of key regulatory announcements on the behaviour of decentralised finance (DeFi) token markets. The event study framework is a well-established econometric tool for assessing how public information influences asset prices, volatility, and liquidity, by isolating abnormal market movements around the timing of discrete, exogenous events. Given the speculative nature of DeFi markets, their reliance on emerging technologies, and the evolving legal uncertainty surrounding them, such markets are particularly sensitive to regulatory announcements. As decentralised financial assets continue to gain traction among retail and institutional investors, they increasingly operate within a complex and fragmented legislative environment that presents both opportunities and significant risks (Ozili, 2022). Analysing how these markets respond to policy signals thus offers timely insights into investor sentiment and the signalling effects of regulation, particularly as financial authorities consider the integration of digital assets into traditional financial infrastructure.

The event windows selected for this analysis consist of symmetric periods around the regulatory event dates: ±1, ±5, ±10, ±15, ±20, ±25, and ±30 trading days. The shorter windows (±1 to ±5 days) are designed to capture immediate and short-term market reactions to information disclosure, reflecting behavioural responses such as speculative trading, panic selling, or heightened caution. In contrast, the medium and longer windows (±10 to ±30 days) are employed to capture persistent or delayed reactions, including price stabilisation, reversion effects, or structural liquidity shifts following regulatory shocks. This stratified window design allows us to assess the temporal dynamics of market response and the degree to which regulation produces transient versus enduring effects on market functioning.

The identification of regulatory events is based on high-impact developments between 2023 and 2025, selected according to their legal significance, market relevance, and international spillover potential. These include the European Union’s Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation, enforcement actions and policy statements by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the proposed U.S. Digital Asset Market Structure and Investor Protection Act, global regulatory guidance issued by the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), and thematic enforcement actions targeting DeFi derivatives and leveraged retail commodities. These events are chosen because they represent distinct types of regulatory engagement, ranging from clarity-enhancing frameworks to market integrity-focused enforcement, and because they originate from jurisdictions with substantial influence over global digital asset markets.

Expected returns in this study are not modelled using a separate pre-event estimation window. Instead, we focus on observed return behaviour across the event windows themselves, using a comparison of token performance before and after each regulatory event. Cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) are calculated within symmetric event windows of ±1, ±5, ±10, ±15, ±20, ±25, and ±30 trading days surrounding each announcement. The calculation is described in detail in Section 3.3.1.

3.2. Sample Selection

The sample comprises ten leading DeFi tokens observed across six high-impact regulatory events occurring between June 2023 and July 2025. This period captures a critical phase in the evolution of digital asset regulation, marked by a growing emphasis on legal clarity, consumer protection, and the supervision of decentralised financial services. It also reflects heightened policy attention on the risks and resilience of emerging fintech markets.

Token selection follows a purposive sampling strategy grounded in both academic classification and empirical relevance. Specifically, we draw on the DeFi typologies proposed by Maia and Vieira dos Santos (2021) and Aramonte et al. (2021) to ensure that the selected tokens represent a broad cross-section of functional categories within the DeFi ecosystem. These include decentralised exchanges (DEXs), lending protocols, governance tokens, stablecoins, oracles, and derivatives platforms. We prioritise tokens with significant market capitalisation, sustained trading activity, and representation in multiple major exchanges to ensure liquidity and data consistency. Illiquid tokens, or those with irregular trading histories, were excluded to avoid distortions in return or volatility calculations. The final sample period, is between 1st January 2023 and 30th September 2025, consists of the following tokens: UNI and CRV (DEXs), AAVE and COMP (Lending Protocol), MKR and SUSHI (Governance), DAI (Stablecoin), LINK and BAND (Oracle), and SNX (Derivatives). These tokens were selected due to their high transaction frequency, inclusion in prior academic literature, and diverse representation across DeFi verticals. Price, volume, and market capitalisation data are retrieved from CoinGecko (2025), while high-frequency trading data, bid, ask, and bid-net spreads, are obtained via the LSEG Workspace (Refinitiv, 2025) database. Daily closing prices are used to compute returns.

We focus on six high-impact regulatory events between June 2023 and July 2025. These events are selected based on three criteria: (1) their legal significance, such as the introduction or enforcement of binding regulatory frameworks; (2) their market relevance, particularly where they affect core DeFi operations; (3) their jurisdictional influence, with emphasis on the United States and European Union, which together account for a substantial share of global crypto activity. The events along with their classification into categories include the following:

- (1)

- Regulatory Framework Announcement: The publication of the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation in the Official Journal of the European Union on 9 June 2023;

- (2)

- DeFi Derivatives Enforcement: Enforcement actions by the United States Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) against DeFi derivatives providers (Opyn, ZeroEx, and Deridex) on 7 September 2023 for offering illegal derivatives;

- (3)

- Global Framework/Guidance: The release of “Final Report with Policy Recommendations for Decentralised Finance (DeFi)” by the International Organisation of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) on 19 December 2023;

- (4)

- Retail Commodity Leverage Enforcement: A CFTC action in ordering Uniswap Labs to pay a civil monetary penalty of USD 175,000 and cease offering leveraged/margined retail commodity transactions on 4 September 2024;

- (5)

- Regulatory Clarity/Implementation: Full applicability of MiCA for many crypto-asset services and issuers on 30 December 2024;

- (6)

- Regulatory Clarity: The introduction of the U.S. Digital Asset Market Clarity Act of 2025—a system of regulation of the offer and sale of digital commodities by the SEC & CFTC, as well as for other purposes, on 17 July 2025.

3.3. Models and Measurements

3.3.1. Cumulative Abnormal Returns (CARs)

To assess the market response of DeFi tokens to regulatory events, we employ an event study framework that computes abnormal returns (ARs) and then cumulative abnormal returns (CARs). First, we estimate expected returns using a market model in which each token’s return is regressed on the returns of Bitcoin (BTC) and Ethereum (ETH), the two most systemically significant cryptocurrencies. The model is specified as follows:

where

- is the daily return of token i on day t, computed as the log difference in closing prices;

- and are the daily log returns of Bitcoin and Ethereum, respectively;

- , , and are token-specific regression coefficients;

- is the residual, representing the abnormal return.

The abnormal return is extracted as the regression residual:

Then, we compute cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) by aggregating ARs over various symmetric event windows around each regulatory announcement date:

where refers to the event window before and after the event date (e.g., , , ). These CARs capture the total impact of the event on token returns over the specified period.

Statistical significance of CARs is tested using t-statistics and corresponding p-values. For each token and event window, we calculate the mean, standard deviation, standard error, and t-statistic of the CARs:

where is the mean cumulative abnormal return, is the sample standard deviation, and is the number of observations in the event window.

3.3.2. Placebo Simulation Procedure (Monte Carlo Robustness Check)

To assess the statistical robustness of observed cumulative abnormal returns (CARs), we implement a placebo-based Monte Carlo simulation using 500 iterations. This procedure evaluates whether regulatory events induce return patterns distinguishable from random market fluctuations. For each iteration , we randomly sample a placebo date from a pool of clean dates, excluding ±45 trading days around all regulatory events. Then, for each event window , we compute the pooled market CAR as follows, where denotes the number of token categories:

One token is randomly sampled from each DeFi category . For each sampled token, a placebo CAR is computed over the window :

To assess robustness at the event–category level, observed CARs are compared to their corresponding placebo distributions. The pseudo p-value is computed as

where N = 500. CARs are classified as statistically robust when .

3.3.3. Volatility Modelling and Structural Stability Tests

Prior to estimating the volatility responses of DeFi tokens to regulatory events, we evaluate the relative performance of four widely used conditional heteroskedasticity models: the standard GARCH(1,1), EGARCH(1,1), GJR-GARCH(1,1), and APARCH(1,1) specifications. Each model is estimated under a Student’s t-distribution using maximum likelihood estimation. For each token, all four models are fit individually, and only those that converge successfully are retained for comparison. Model selection is guided by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which balance model fit against complexity (as described in Mitchell & McKenzie, 2003, citing Akaike, 1973, and Schwarz, 1978). The selection criteria are computed as follows:

where is the maximised log-likelihood, is the number of parameters, and is the sample size. To ensure robustness, we compute the average AIC and BIC values across all tokens and select the model with the lowest mean score.

The Generalised Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (GARCH) framework is widely used in financial econometrics for modelling time-varying volatility, capturing persistence and clustering effects commonly observed in cryptocurrency markets (Bollerslev, 1986). We first estimate a standard GARCH(1,1) model for each token, incorporating regulatory event dummies as exogenous regressors in the variance equation:

where

- is the conditional variance of token returns at time t;

- is a constant;

- captures the short-term impact of past return shocks (ARCH term);

- reflects the persistence of volatility over time (GARCH term);

- is the squared residual from the mean equation;

- is a dummy variable equal to 1 on specific days pre-post each regulatory event (day 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30), and 0 otherwise;

- measures the impact of the regulatory event at each horizon on volatility.

To account for asymmetric effects, we also estimate the exponential GARCH (EGARCH(1,1) model), which models volatility in logarithmic form and captures differences in how positive and negative shocks affect conditional variance:

where

- captures the leverage effect, showing the asymmetry in response to positive vs. negative shocks;

- measures the magnitude effect of shocks;

- is the expected value of a standardised normal distribution (e.g., );

- Other terms are as previously defined.

Regulatory event dummies are created relative to each event. This setup allows us to trace the trajectory of volatility following the initial policy shock and to test whether effects are concentrated or persistent over time. All models are estimated using maximum likelihood with a standardised Student’s t-distribution to account for the heavy tails typical of crypto return series. Estimation is performed per token and per event using the rugarch package in RStudio 2025.09.2+418 (Posit Software). Following model estimation, we extract the conditional variance series and the estimated event shock coefficients () to evaluate the statistical significance and direction of volatility effects.

We employ two complementary diagnostic procedures to assess the robustness of the estimated volatility dynamics and address concerns regarding potential structural instability during the 2023–2025 period: the Nyblom (1989) parameter constancy test and the Bai and Perron (1998) multiple structural breakpoint test. These methods allow us to evaluate both gradual parameter variation and discrete regime shifts in the return and volatility processes.

The Nyblom (1989) test examines whether model parameters remain constant over time by evaluating the cumulative score process of the likelihood function. In line with our implementation, the test is applied to each EGARCH(1,1) model estimated for every token–event pair. We focus on individual parameter statistics, and following standard practice, a token is classified as stable if the maximum individual statistic does not exceed the 5% critical value (0.47). This approach allows for event-specific assessment of parameter stability while accommodating heterogeneous volatility dynamics across tokens. Formally, the test statistic is constructed as

where

- represents the cumulative sum of the scores (the derivatives of the log-likelihood function) up to time t;

- (The Information Matrix): This is the estimated covariance matrix of the scores for the full sample;

- is the sample size.

To detect potential discrete structural changes in the return-generating process, we apply the Bai and Perron (1998) multiple breakpoint test. This framework estimates linear models with an unknown number of breakpoints by minimising the residual sum of squares subject to a penalty for model complexity. The Bai–Perron test is applied to token-level return series, and breakpoint configurations with up to five potential breaks are evaluated. This procedure allows us to distinguish between genuine regime shifts and spurious improvements in fit arising from over-segmentation. Model selection is computed as follows:

where

- is the residual sum of squares for a model with breakpoints;

- is the number of estimated parameters;

- is the sample size.

3.3.4. Panel Analysis: Two-Way Fixed Effects

To investigate how regulatory announcements influence liquidity in DeFi markets, we implement a series of panel regression models using a two-way fixed effects (FE) specification. This framework allows us to account for unobserved heterogeneity both across tokens and over time, addressing idiosyncratic token traits and broader market-wide developments that could confound the regulatory effect.

Liquidity is measured using three complementary indicators. First, we use the natural logarithm of daily trading volume to capture depth and market participation. Second, we examine the bid–ask spread, a traditional microstructural proxy for trading frictions. Third, we employ the Amihud illiquidity ratio, which reflects the price impact of trades and is commonly used to assess illiquidity in less mature or fragmented markets.

Each model incorporates lagged explanatory variables to capture the delayed effect of information and to mitigate endogeneity concerns. Specifically, we include the absolute value of the previous day’s abnormal return, five-day rolling standard deviation of returns, bid-ask spread, price level, and log volume (as appropriate). We also control for broader market conditions through lagged Bitcoin returns and two macro-financial variables: a log-transformed global crypto index (IDX) and the daily change in the VIX, both standardised prior to estimation. To identify the temporal effects of regulatory events, we introduce dummy variables capturing both pre- and post-event windows. Specifically, we include binary indicators for trading days –30, –15, –10, –5, 0, +5, +10, +15, and +30 relative to each announcement. This structure enables us to model both anticipatory effects—where market participants may react before formal publication—and lagged responses, reflecting adjustment dynamics in DeFi liquidity and pricing. The use of symmetric event windows allows for the examination of potential information leakage, front-running behaviour, and delayed market assimilation of regulatory signals. All models are estimated using the plm package in R, applying robust standard errors clustered at the token level to correct for heteroskedasticity and serial correlation. The general model specification is as follows:

where

- is the liquidity outcome (log volume, spread, or Amihud illiquidity) for token i at time t;

- are lagged control variables;

- denotes event-day dummies relative to regulatory announcements;

- and are token and time fixed effects, respectively;

- is the idiosyncratic error term.

The three models are specified as follows:

Model A (Log Volume):

where

- is the log-transformed trading volume;

- is the absolute abnormal return;

- is the 5-day rolling volatility;

- is the bid–ask spread;

- is the log token price;

- is lagged Bitcoin return;

- , are standardised macro controls;

- are event dummies for days –30 to +30;

- and denote token and time fixed effects.

Model B: Bid–Ask Spread

where all variables are defined as above, with the dependent variable being the raw bid–ask spread.

Model C: Amihud Illiquidity Ratio

where

- .

- The remaining variables and structure are consistent with Models A and B.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Cumulative Abnormal Returns Around Regulatory Events

4.1.1. CAR-1st Event—Mica Publication

The release of the Markets in Crypto-Assets (MiCA) Regulation on 9 June 2023 triggered a statistically significant but transitory negative market response among DeFi tokens. As shown in Table 1, cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) reached −8.7% at t = −20 (p < 0.01) and −7.0% at t = −15 (p < 0.01), indicating strong anticipatory effects. Although post-event CARs turned positive by t = +25 (+10.1%), these were not statistically significant, suggesting limited informational impact at the time of release. Category-level analysis (Table 2) reveals that Decentralised Exchange (DEX) and Oracle tokens primarily drove the negative pre-event response. DEX tokens exhibited CARs of −8.2% (p < 0.05) at t = −15 and −5.8% (p < 0.05) at t = −10, while Oracle tokens experienced a notable decline of −10.2% at t = −25 (p < 0.05). These results suggest heightened sensitivity to regulatory developments among infrastructure-related protocols.

Table 1.

Cumulative Abnormal Returns across all DeFi tokens Response to Key Regulatory and Enforcement Actions.

Table 2.

Cumulative Abnormal Returns by DeFi Category in Response to Key Regulatory and Enforcement Actions.

4.1.2. CAR-2nd Event—CFTC Enforcement

The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)’s enforcement actions against Opyn, ZeroEx, and Deridex on 7 September 2023 elicited a more subdued market response compared to the MiCA announcement. Pooled CARs remained largely insignificant across event windows (Table 1), indicating muted market-wide effects. However, token-specific reactions diverged significantly. As shown in Table 2, DEX tokens experienced a significant pre-event decline, with CARs of −13.8% at t = −30 (p < 0.05), suggesting early anticipation of enforcement. Conversely, Oracle tokens recorded a significant post-event gain of +7.3% at t = +15 (p < 0.05), possibly reflecting a reassessment of enforcement risk among non-targeted protocols. These asymmetric effects point to differentiated regulatory exposure across token categories.

4.1.3. CAR-3rd Event—IOSCO Guidance

The publication of the IOSCO Final Report on DeFi on 19 December 2023 generated a selective market response. While pooled CARs remained statistically insignificant across all windows (Table 1), disaggregated results (Table 2) indicate a positive reaction among governance tokens. Specifically, governance tokens recorded CARs of +9.8% at t = +10 (p < 0.10) and +7.3% at t = +15 (p < 0.05), suggesting that the report was perceived as providing favourable or clarifying guidance. DEX and Oracle tokens did not exhibit statistically significant responses, although modest anticipation effects were observed among governance tokens at t = −5 (−2.8%).

4.1.4. CAR-4th Event—CFTC Uniswap

The CFTC’s enforcement action against Uniswap Labs on 4 September 2024 resulted in a muted but asymmetric market reaction. Pooled CARs were modestly positive, with a statistically significant gain of +10.8% at t = +25 (p < 0.05) (Table 1), suggesting a market perception of reduced regulatory uncertainty. As Table 2 shows, DEX tokens experienced a notable post-event rebound, with CARs of +12.3% at t = +5 (p < 0.05), +12.8% at t = +15 (p < 0.10), and +4.7% at t = +20 (p < 0.05). Oracle tokens also recorded a marginally significant gain of +7.7% at t = +10 (p < 0.10). These findings indicate that the enforcement action, while targeted, may have enhanced clarity for core DeFi protocols.

4.1.5. CAR-5th Event—Mica Implementation

The full implementation of the EU MiCA regime on 30 December 2024 elicited a differentiated response across DeFi token categories. Pooled CARs remained statistically insignificant (Table 1); however, Table 2 reveals a significant post-event appreciation among DEX tokens, with CARs of +4.2% at t = +5 (p < 0.05) and +10.8% at t = +25 (p < 0.05). The absence of significant responses among governance and oracle tokens suggests that only trading-centric protocols perceived regulatory implementation as beneficial. These gains likely reflect market relief over transitional provisions and regulatory certainty.

4.1.6. CAR-6th Event—US Act

The passage of the Digital Asset Market Clarity Act in 2025 generated mixed and category-specific market responses. Pooled CARs were largely insignificant, except for a decline of −12.3% at t = +30 (p < 0.05), as reported in Table 1. However, disaggregated results (Table 2) show that governance tokens responded positively, with a CAR of +9.8% at t = +10 (p < 0.05), whereas DEX tokens recorded a marginal decline of −2.7% at t = +15 (p < 0.10). These results suggest that while governance-focused protocols welcomed legislative clarity, decentralised trading platforms remained more vulnerable to perceived legal risk under the new regime.

4.1.7. Placebo Event Tests and Robustness

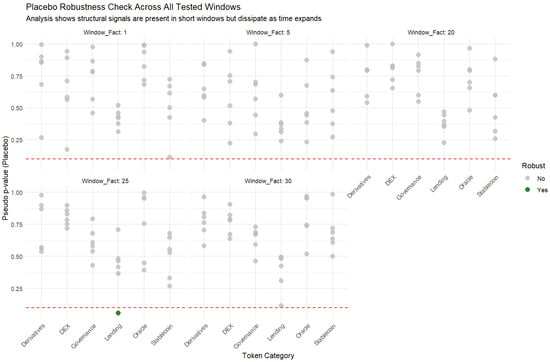

To assess the statistical robustness of the empirical findings and account for the high volatility endemic to DeFi markets, we conduct a series of placebo event simulations using Monte Carlo methods. Specifically, Panel B presents the empirical distribution of placebo CARs derived from 500 Monte Carlo simulations. The placebo distributions confirm that random timing does not induce systematic return drift, as the median (50th percentile) CAR remains close to zero across all event windows. However, the dispersion of the placebo CARs widens considerably with longer windows, reflecting greater exposure to unrelated market fluctuations. Specifically, the upper tail of the placebo distribution expands with the event window: the 95th percentile increases from 4.6% at ±1 day to 21.7% at ±30 days, whereas the mean CAR decreases modestly from −0.3% to −3.7% over the same interval (see Panel B of Table 1). This widening distribution illustrates that longer windows capture a higher degree of background volatility, emphasising the importance of using narrow windows for event attribution in highly dynamic DeFi environments. Figure 1 complements this analysis by plotting pseudo p-values derived from the same 500 placebo simulations, grouped by token category and event window. Consistent with the placebo distributions, the vast majority of event-category pairs fall well above the significance threshold across all windows, suggesting that observed CARs largely reflect normal market variation rather than event-driven reactions. Notably, a single statistically significant response is detected in the Lending token category during the MiCA publication event within the ±25-day window with a pseudo p-value of 0.056. This isolated result indicates a localised sensitivity rather than a systemic market reaction. Taken together, these placebo-based robustness checks reinforce the central conclusion: regulatory announcements in the DeFi sector do not produce broad or persistent abnormal returns. Instead, market responses appear selective, category-specific, and contingent on the perceived regulatory exposure of individual token classes.

Figure 1.

Placebo Robustness Check by Token Category and Event. Notes: This figure shows pseudo p-values derived from 500 placebo simulations in which CARs are computed around randomly selected non-event dates. Results are shown by token category and event window. Green dots represent statistically significant effects at the 10% level. The red dashed line denotes the p = 0.10 threshold.

4.2. Volatility Effects: GARCH and EGARCH Models

Before estimating the volatility responses to regulatory events, we compare four standard conditional volatility models: GARCH(1,1), EGARCH(1,1), GJR-GARCH(1,1), and APARCH(1,1). Model selection is based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC; Akaike, 1973) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC; Schwarz, 1978), which are widely used for evaluating competing GARCH-type specifications (Mitchell & McKenzie, 2003). As shown in Table 3, the eGARCH(1,1) specification yielded the lowest average AIC (−4.97) and BIC (−4.94) across the token sample, followed closely by the standard GARCH specification, indicating a marginally superior fit. Given these results, we employ GARCH(1,1) as the baseline model to capture overall volatility dynamics, while EGARCH(1,1) is used to assess potential asymmetries in volatility responses to regulatory and enforcement events. This dual specification allows us to distinguish between general volatility persistence and asymmetric reactions to regulatory shocks, which are particularly relevant in downside-risk-sensitive DeFi markets.

Table 3.

Models’ comparison.

4.2.1. GARCH(1,1)

The GARCH(1,1) estimates reported in Table 4 provide insight into the volatility dynamics of DeFi tokens surrounding six major regulatory and enforcement events. The results indicate that volatility is predominantly driven by endogenous market mechanisms, with limited evidence of discrete policy-induced volatility shifts once conditional heteroskedasticity is accounted for.

Table 4.

GARCH(1,1) Estimation Results for all tokens and all events.

The short-term shock coefficients (α1), which capture the influence of recent return innovations on volatility, are statistically significant (p < 0.05) across most tokens and events. Tokens such as CRV (α1 ≈ 0.087), MKR (α1 ≈ 0.113), COMP, and SNX consistently exhibit elevated α1 values, indicating heightened sensitivity to immediate news and return surprises. This pattern is especially pronounced during the MiCA publication, CFTC enforcement actions, and the passage of the U.S. Digital Asset Market Clarity Act. By contrast, tokens like UNI (α1 ≈ 0.017) and BAND (α1 ≈ 0.014) display relatively low shock coefficients, suggesting that their volatility is more influenced by volatility persistence rather than abrupt price movements. This is confirmed by the consistently high β1 values (typically > 0.90), reflecting a strong autoregressive component in conditional variance. The shape parameters of the Student-t distribution are also significant across most tokens, underscoring the presence of fat tails and the departure from normality in DeFi return distributions. Furthermore, the combined persistence of volatility (α1 + β1) exceeds 0.90 in nearly all cases, highlighting the long memory of volatility and the gradual decay of shocks over time.

Despite the inclusion of dummy variables representing event-day effects (capturing t = −30 to t = +30), none of the event-related coefficients were statistically significant across any token or event. This suggests that, regulatory announcements do not produce statistically distinguishable volatility shifts once endogenous dynamics are accounted for. Instead, regulatory news appears to be absorbed through the usual process of volatility clustering and market adaptation, without introducing structural breaks or regime shifts.

These findings suggest that imply that regulatory news influences returns but not volatility spikes (as shown in the CAR analysis). Instead, they act as catalysts within the broader framework of endogenous market volatility, reinforcing rather than disrupting the existing volatility process.

4.2.2. EGARCH(1,1)

The EGARCH(1,1) estimation results, presented in Table 5, provide further insight into the asymmetric volatility dynamics of DeFi tokens around major regulatory and enforcement events. Across all events, the core model parameters, α1 (shock sensitivity), β1 (volatility persistence), and γ1 (leverage effect), are statistically significant for most categories, indicating that DeFi token volatility exhibits strong conditional heteroskedasticity, persistence, and asymmetry. Notably, DEX, Lending, and Stablecoin tokens consistently show high β1 values (typically above 0.96), underscoring a high degree of volatility persistence, while the uniformly positive γ1 coefficients imply that volatility in DeFi tokens responds more strongly to positive shocks than to adverse news. This asymmetric response pattern suggests that optimistic signals, such as enhanced regulatory certainty or market expansion prospects, intensify volatility, reflecting speculative adjustments and heightened investor sensitivity to favourable developments.

Table 5.

EGARCH(1,1) Estimation Results for all tokens and all events.

The inclusion of event-day dummy variables allows for a granular assessment of whether regulatory announcements coincide with abnormal volatility shifts. The results reveal category-specific and time-lagged effects, rather than systemic or immediate volatility spikes at the announcement date. For instance, the publication of the MiCA regulation (Panel A) was followed by statistically significant volatility reductions in Oracle and Governance tokens in the pre-event period (i.e., t = −20 to t = −10), possibly reflecting anticipatory positioning or reduced uncertainty. In contrast, the CFTC’s enforcement action on Uniswap (Panel D) produced significant post-event volatility increases among DEX and Lending tokens (t = +10 to +25), suggesting renewed regulatory risk reassessment. Similar delayed volatility effects are observed following the U.S. Digital Asset Market Clarity Act (Panel F), particularly in Governance and Lending categories, where conditional variance increases significantly in the post-event period.

Interestingly, not all regulatory events produced strong volatility reactions. The IOSCO DeFi guidance (Panel C) and MiCA implementation (Panel E) were associated with relatively modest or statistically insignificant volatility shifts, suggesting that non-binding guidance or well-telegraphed regulatory rollouts may not materially disrupt conditional variance. These findings support the view that DeFi markets incorporate regulatory information asymmetrically and over time, with volatility adjustments more prominent in token categories directly exposed to compliance or enforcement risk.

EGARCH(1,1) results highlight that regulatory developments do not uniformly trigger discrete volatility shocks across the DeFi ecosystem. Instead, conditional variance evolves through endogenous dynamics, with event-related effects manifesting in select token categories and often with a lagged response. This reinforces the earlier event study findings and underscores the importance of disaggregated analysis when assessing the market implications of financial regulation in decentralised systems.

4.3. Structural Stability Tests of Volatility Models

To address concerns regarding potential structural instability in DeFi token volatility over the 2023–2025 period, we employ two complementary diagnostic procedures: the parameter constancy test of Nyblom (1989) and the multiple structural breakpoint test of Bai and Perron (1998). The Nyblom test examines whether model parameters remain stable over time by evaluating the cumulative score process, while the Bai–Perron framework detects unknown structural breaks in the return-generating process, balancing improvements in model fit against parsimony through information criteria. These approaches provide a comprehensive assessment of both gradual parameter drift and discrete regime shifts in volatility dynamics.

4.3.1. Nyblom Parameter Stability Test

The Nyblom test displayed in Table 6 reveals heterogeneous stability outcomes across regulatory events. The MiCA Publication event exhibits the highest degree of stability, with 66.7% of tested tokens maintaining constant volatility parameters at the 5% significance level. In contrast, the U.S. Digital Asset Act displays the lowest stability rate (16.7%), indicating elevated structural uncertainty and greater reparameterization of volatility dynamics during this legislative episode. Notably, certain tokens, including UNI and SNX, consistently pass the Nyblom test across almost all events, suggesting that their volatility structures are comparatively resilient to regulatory shocks. These findings imply that parameter instability is event-contingent rather than systemic, aligning with the notion that regulatory interventions generate differentiated and localised effects within DeFi markets.

Table 6.

Proportion of Stable Tokens by Regulatory Event.

4.3.2. Bai-Perron Structural Break Test

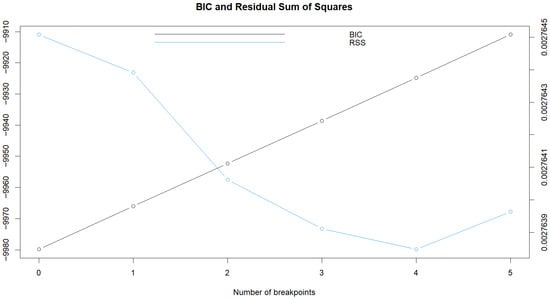

The diagnostic results of Bai-Perron test shown in Figure 2 indicate that the specification with zero breakpoints minimises the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which attains its lowest value (approximately −9980) when no structural breaks are introduced. Although the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS) declines monotonically as additional breakpoints are added, the corresponding increase in BIC suggests that these improvements in fit are not sufficient to justify the added model complexity. Following Bai and Perron (1998), this pattern supports the conclusion that no statistically significant structural break is present in the primary return process. Consequently, the long-run volatility coefficients estimated in the subsequent GARCH-type models are not undermined by unaccounted-for regime shifts, and the conditional variance dynamics can be considered structurally stable over the sample period.

Figure 2.

Bai–Perron Test for Multiple Structural Breaks in the Conditional Variance Process. Notes: This figure plots the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC, left y-axis) and Residual Sum of Squares (RSS, right y-axis) for segmentations with 0 to 5 structural breakpoints in the return series. Lower BIC values indicate better model fit with a penalty for added complexity. RSS measures model fit without penalisation. The optimal number of breakpoints is selected based on the minimum BIC.

These structural stability tests are consistent with the earlier GARCH model results. While the GARCH(1,1) framework finds no statistically significant volatility shocks directly attributable to regulatory announcements, the Nyblom test reveals that volatility parameters can evolve gradually in response to certain regulatory episodes. This event-contingent variation does not imply systemic instability. Moreover, the Bai–Perron test confirms the absence of discrete structural breaks in the return-generating process, supporting the robustness of long-run volatility estimates. Taken together, these findings suggest that DeFi markets exhibit structural resilience, with localised parameter shifts reflecting adaptive but stable volatility processes.

4.4. Liquidity Effects

4.4.1. Log-Volume

The two-way fixed effects panel regression results reported in Table 7 indicate that trading volume in DeFi tokens is significantly influenced by market volatility and price dynamics. The model explains approximately 31.4% of the variation in log trading volume, a considerable level of explanatory power given the high-frequency and decentralised nature of the underlying markets.

Table 7.

Two-Way Fixed Effects Panel Regression Results on Token Liquidity and Event Impact.

Lagged abnormal return magnitude (abs(L1_ARm)) and short-term volatility (L1_Vol5d) both exhibit strong, positive, and highly significant coefficients (5.49 and 8.07, respectively; p < 0.001), suggesting that heightened return dispersion and volatility are associated with intensified trading activity. This aligns with theories of risk-motivated trading, where uncertainty attracts speculative capital and short-term arbitrage strategies. Conversely, the lagged bid-ask spread (L1_spread) is negatively associated with trading volume (−0.214, p < 0.001), consistent with classical microstructure models in which higher transaction costs deter participation. The lagged price level (L1_price) has a positive and significant effect (0.648, p < 0.001), implying that tokens with higher nominal values attract greater trading volume—possibly reflecting institutional or algorithmic trading preferences.

The results emphasise that liquidity provision in DeFi is strongly volatility-driven, with transaction costs playing a secondary role. The inclusion of token and time fixed effects controls for unobservable heterogeneity, reinforcing the robustness of these findings. These dynamics highlight the need to monitor risk-based metrics, particularly in evolving regulatory contexts where DeFi markets may become increasingly sensitive to shocks.

4.4.2. Spread

The model specification for bid-ask spreads yields limited explanatory power, with an R2 of just 0.031, and none of the included predictors attaining statistical significance at conventional levels. While the signs of the coefficients are directionally consistent with theoretical expectations, volatility increasing spreads and volume reducing them, the effects are economically and statistically weak. This lack of significance likely reflects the non-traditional liquidity formation mechanisms in decentralised markets, where automated market makers (AMMs) and smart contract-based liquidity provision alter the role of information asymmetry and order flow. In such settings, spreads are often protocol-determined rather than driven by supply-demand imbalances in the traditional sense.

These results suggest that standard microstructure variables are insufficient to capture spread behaviour in DeFi. Future research may benefit from exploring nonlinear specifications, interaction terms, or models incorporating AMM-specific features such as pool depth, slippage functions, and fee structures.

4.4.3. Amihud

The final model examines Amihud illiquidity, a widely used proxy for price impact per unit of trading volume. The panel regression explains approximately 12.2% of the variation, which, while modest, reflects meaningful explanatory power in a decentralised and rapidly evolving market structure.

Both lagged abnormal returns (abs(L1_ARm)) and short-term volatility (L1_Vol5d) have positive and statistically significant effects on illiquidity (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively), indicating that heightened market risk leads to thinner liquidity and greater price impact. These findings are consistent with risk-averse liquidity providers withdrawing capital in response to elevated uncertainty. By contrast, lagged trading volume (L1_log_volume) significantly reduces illiquidity (p < 0.05), reaffirming that deeper liquidity pools mitigate the price effects of trades. Notably, the price level has no significant effect, suggesting that in AMM-driven environments, valuation does not directly govern liquidity risk.

These results support the view that DeFi market illiquidity is predominantly risk-sensitive and volume-dependent. The role of volatility in shaping liquidity conditions highlights the importance of monitoring microstructure resilience in the face of regulatory or market-wide shocks.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study examines how decentralised finance (DeFi) token markets respond to regulatory interventions through a multi-method empirical approach. By combining event study analysis, conditional volatility modelling (GARCH, EGARCH), structural stability diagnostics (Nyblom, Bai-Perron), and panel regressions, we assess six high-impact regulatory events between 2023 and 2025 and their effects on returns, volatility, and liquidity across ten DeFi tokens from key functional categories.

Our results suggest that regulatory news does not trigger systemic disruption in DeFi token markets. Short-term cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) reveal selective and category-specific reactions, particularly in response to the publication of the MiCA Regulation and enforcement actions by the CFTC. These price responses are not uniformly significant across all tokens or windows, placebo simulations confirm that only one category-event pair (lending tokens during the MiCA publication at ±25 days, pseudo p-value = 0.056) exceeds the placebo benchmark. This indicates that observed return movements largely reflect category-specific risk repricing rather than broad market overreaction.

Volatility effects display a high degree of persistence (β1 > 0.90 across tokens), with shock sensitivity (α1) varying by token. EGARCH estimates reveal asymmetric volatility responses to regulatory events, as evidenced by the predominantly positive and statistically significant γ1 coefficients in several categories. This pattern indicates a reverse-asymmetric effect, whereby positive shocks, such as favourable or clarifying regulatory developments, amplify volatility more strongly than negative ones. These effects are delayed and category-specific rather than concentrated on announcement dates. Additionally, structural stability tests indicate that volatility processes are largely stable over the sample period. The Bai–Perron test identifies no statistically significant structural breaks in the return-generating process, while Nyblom tests show that parameter instability is event-contingent rather than systemic. Specifically, 66.7% of tokens remain stable during the MiCA publication, compared with 16.7% during the U.S. Digital Asset Market Clarity Act, suggesting temporary re-parameterisation rather than regime shifts.

Liquidity responses are risk-mediated rather than regulation-driven. Panel regressions show that short-term volatility and return dispersion significantly increase trading volume (coefficients of 8.07 and 5.49, respectively; at 1% significant level), while higher bid-ask spreads reduce activity. Amihud illiquidity increases with volatility and price shocks but decreases with volume, suggesting that trading activity, rather than regulatory news, governs market depth and resilience. The limited explanatory power of spread models further reflects the decentralised nature of liquidity formation in DeFi protocols.

Taken together, these findings suggest that regulatory interventions in DeFi markets do not generate immediate or systemic disruption. Instead, regulatory information is incorporated gradually and unevenly, depending on token function, protocol exposure, and perceived compliance risk. The evidence provides little support for widespread overreaction or transitory volatility shocks; rather, it points to adaptive but resilient market behaviour, where regulatory news interacts with existing volatility and liquidity dynamics.

From a policy perspective, the results suggest that targeted and category-specific enforcement actions may be more effective in shaping DeFi market behaviour than broad, undifferentiated interventions. Infrastructure-related tokens, such as DEX and governance tokens, exhibit stronger volatility and return responses, likely due to their central role in protocol operation and compliance visibility. While the study does not directly test regulatory design features, the observed heterogeneity implies that differentiated enforcement strategies could help mitigate uncertainty without impairing liquidity across the broader ecosystem.

For researchers and market participants, the findings underscore the importance of accounting for token function, volatility asymmetry, and risk persistence when analysing DeFi regulatory impacts. Importantly, although the empirical design mitigates endogeneity risks by using event timing, pre-event windows, fixed effects, and placebo simulations, some limitations remain. Certain enforcement actions may be endogenous to prior market conditions, and key protocol-level variables, such as leverage structures, liquidity pool composition, or oracle update frequency, are unobserved at the token level. These unmeasured factors may simultaneously influence returns, volatility, and liquidity, introducing potential omitted variable bias.

Future research should extend this analysis by incorporating decentralised protocol characteristics, exploring algorithmic governance mechanisms, and evaluating alternative regulatory transmission channels. Such extensions would contribute to a more comprehensive causal understanding of policy interventions–decentralised market interactions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study consists of two components: Publicly available data obtained from Coingecko, which can be freely accessed and downloaded. Licensed financial data accessed via LSEG Workspace (Refinitiv) through a student account under Middlesex University’s academic agreement.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the participants of the BAFA South West Area Group (SWAG) online conference, held on 19 November 2025, for their insightful comments and constructive suggestions. The author is also grateful to the anonymous reviewers and the editors for their careful reading of the manuscript and valuable feedback, which have significantly improved the quality of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adamyk, B., Benson, V., Adamyk, O., & Liashenko, O. (2025). Risk management in DEFI: Analyses of the innovative tools and platforms for tracking DEFI transactions. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. (1973). Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In B. N. Petrov, & F. Csaki (Eds.), International symposium on information theory (pp. 267–281). Akademiai Kiado. [Google Scholar]

- Alim, W., Khan, N. U., Zhang, V. W., Cai, H. H., Mikhaylov, A., & Yuan, Q. (2024). Influence of political stability on the stock market returns and volatility: GARCH and EGARCH approach. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyev, F., Ajayi, R., & Gasim, N. (2020). Modelling asymmetric market volatility with univariate GARCH models: Evidence from Nasdaq-100. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 22, e00167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mansour, B. Y. (2020). Cryptocurrency market: Behavioral finance perspective. Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business, 7(12), 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amihud, Y., & Mendelson, H. (1986). Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. Journal of Financial Economics, 17(2), 223–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramonte, S., Huang, W., & Schrimpf, A. (2021, December). DeFi risks and the decentralisation illusion. In BIS quarterly review. Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt2112b.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Auer, R., & Claessens, S. (2018, September). Regulating cryptocurrencies: Assessing market reactions. In BIS quarterly review. Bank for International Settlements. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1809f.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Bai, J., & Perron, P. (1998). Estimating and testing linear models with multiple structural changes. Econometrica, 66(1), 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballis, A., & Verousis, T. (2022). Behavioural finance and cryptocurrencies. Review of Behavioral Finance, 14(4), 545–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertomeu, J., Martin, X., & Sall, I. (2024). Measuring DeFi risk. Finance Research Letters, 63, 105321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollerslev, T. (1986). Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. Journal of Econometrics, 31(3), 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N., & Jeng, L. (2021). DeFi protocol risks: The paradox of DeFi. In “Regtech, suptech and beyond: Innovation and technology in financial services”, riskbooks—Forthcoming Q3. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, T. C. (2020). US policy uncertainty and stock returns: Evidence in the US and its spillovers to the European Union, China and Japan. The Journal of Risk Finance, 21(5), 621–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoinGecko. (2025). Cryptocurrency prices, charts, and crypto market cap [Data set]. CoinGecko. Available online: https://www.coingecko.com/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Corbet, S., Lucey, B., Urquhart, A., & Yarovaya, L. (2018). Cryptocurrencies as a financial asset: A systematic analysis. International Review of Financial Analysis, 62, 182–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, D., Fuchs, J., & Momtaz, P. P. (2025). Market reactions to cryptocurrency regulation: Risk, return and the role of enforcement quality. British Journal of Management, 36(4), 1709–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyhrberg, A. H. (2016). Bitcoin, gold and the dollar—A GARCH volatility analysis. Finance Research Letters, 16, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easley, D., & O’Hara, M. (1987). Price, trade size, and information in securities markets. Journal of Financial Economics, 19(1), 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F. (1982). Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica, 50(4), 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, B. D., & Werbach, K. (2021). The impact of cryptocurrency regulation on trading markets. Journal of Financial Regulation, 7(1), 48–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, Y., & Hutton, I. (2023). Regulatory fragmentation: Investor reaction to SEC and CFTC enforcement in crypto markets. Boston College Law Review, 64, 1555. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, S., & Prosad, J. M. (2017). Behavioural finance: A review. Procedia Computer Science, 122, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsiampa, P. (2017). Volatility estimation for Bitcoin: A comparison of GARCH models. Economics Letters, 158, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, T. (2021, August 11). “Investors must be vigilant and cautious” following the massive $600 million DeFi hack, experts say. CNBC. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/11/over-600-million-dollars-was-stolen-in-a-massive-defi-hack.html (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Maia, G. C., & Vieira dos Santos, J. (2021). MiCA and DeFi (‘proposal for a regulation on market in crypto-assets’ and ‘decentralised finance’). In Blockchain and the law: Dynamics and dogmatism, current and future, forthcoming. Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehar, M. I., Shier, C. L., Giambattista, A., Gong, E., Fletcher, G., Sanayhie, R., Kim, H. M., & Laskowski, M. (2017). Understanding a revolutionary and flawed grand experiment in blockchain: The DAO attack. Journal of Cases on Information Technology (JCIT), 21(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, H., & McKenzie, M. D. (2003). GARCH model selection criteria. Quantitative Finance, 3(4), 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D. B. (1991). Conditional heteroskedasticity in asset returns: A new approach. Econometrica, 59(2), 347–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyblom, J. (1989). Testing for the constancy of parameters over time. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 84(405), 223–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P. K. (2022). Decentralized finance research and developments around the world. Journal of Banking and Financial Technology, 6(2), 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, L., & Veronesi, P. (2012). Uncertainty about government policy and stock prices. The Journal of Finance, 67(4), 1219–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puławska, K. (2025). Impact of the mica regulation on crypto-asset markets activity an event study approach. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5393753 (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Raynor, D. B. (2025). DeFi TVL of multiple blockchains combined as of 12 August 2025. Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1272181/defi-tvl-in-multiple-blockchains/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Refinitiv. (2025). Historical cryptocurrency and decentralised finance market data for selected tokens [Data set]. Refinitiv Workspace. Available online: https://workspace.refinitiv.com/web/browser://newtab/ (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaev, S., Sharma, S., Ghimire, B., & Shuraeva, A. (2019). Taming the blockchain beast? Regulatory implications for the cryptocurrency Market. Research in International Business and Finance, 51, 101080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingärtner, T., Fasser, F., Da Costa, P. R. S., & Farkas, W. (2023). Deciphering DEFI: A comprehensive analysis and visualization of risks in decentralized finance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(10), 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S., Perez, D., Gudgeon, L., Klages-Mundt, A., Harz, D., & Knottenbelt, W. (2022, September 19–21). SoK: Decentralized finance (DeFi). 4th ACM Conference on Advances in Financial Technologies (AFT’22), Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronka, C. (2021). Financial crime in the decentralized finance ecosystem: New challenges for compliance. Journal of Financial Crime, 30(1), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, D. A., Arner, D. W., & Buckley, R. P. (2020). Decentralized finance. Journal of Financial Regulation, 6(2), 172–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.