Abstract

Over the last decade, there has been a significant increase in banks’ investment in technology, alongside a substantial rise in CEO compensation. Research on executive compensation has primarily focused on traditional performance metrics, such as return on assets and return on equity, as well as governance factors. Investigating the nexus between fintech adoption and CEO compensation introduces a new perspective on the determinants of CEO pay and how technological transformation influences executive remuneration structures. This study investigated the relationship between Chief Executive remuneration and fintech adoption among banks listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. There is a lack of literature on the impact of technology adoption on CEO compensation in developing and emerging economies. The quantitative longitudinal study, conducted over 15 years from 2010 to 2024, collected secondary data from the annual reports of six banks and the IRESS database. A panel data fixed effects regression analysis was employed to analyze the data. CEO compensation included both salary and total compensation. Fintech variables used for the study included automated teller machines, mobile banking, and internet banking. The findings revealed a positive relationship between CEO salary and the rollout of ATMs and mobile banking, while an inverse relationship was noted between salary and internet banking. Similarly, total compensation showed an inverse relationship with the adoption of ATMs and internet banking, whereas mobile banking had a positive effect on total compensation. Understanding how technology impacts CEO compensation can help remuneration committees ensure that CEO pay is linked to the value that infrastructure investments bring to an organization, rather than simply the number of innovations introduced. This understanding will also help solve the principal-agent problem, as it will ensure technology innovations that enhance firm performance are rewarded. In the context of emerging markets, the study’s findings suggest that organizations should recognize and formalize pay linked to digital transformation, rather than focusing solely on short-term financial metrics. This also suggests the need to develop guidelines for executive remuneration disclosure related to the technology sector. The close connection between fintech adoption and technological and regulatory risks highlights the need to balance incentive structures that reward innovation with risk-adjusted performance measures.

1. Introduction

The topic of executive compensation is increasingly attracting attention from scholars. Lee and Pati (2024) argue that the disparity between a CEO’s pay and the average employee’s salary makes this subject particularly interesting. Blanes et al. (2020) note that the excessive nature of CEO compensation and instances where it appears to reward failure rather than performance have prompted researchers to investigate the factors influencing executive remuneration. The interest in examining determinants of CEO compensation has been exacerbated by the failure of scholars to reach a consensus on the reasons behind the surge in CEO compensation (Luijsterburg, 2024).

Exorbitant pay discrepancies between the CEO and the average employee have been cited among JSE companies (Deysel & Kruger, 2015). Teuteberg (2025) emphasizes that CEO salaries in South Africa, especially among Johannesburg Stock exchange (JSE) listed companies, are disproportionately high; in some cases, the CEO to minimum wage ratio reaches 700, which is vastly higher than the recommended range of 20:1 to 60:1. Similarly, Khumalo and Masenge (2015) argue that the gap between CEO remuneration and that of average employees in South Africa is the largest in the world. This disparity has led various scholars (Khumalo & Masenge, 2015; Coetzee & Bezuidenhout, 2019; Deysel & Kruger, 2015) to seek a deeper understanding of the determinants of CEO compensation and the relationships between these factors in the South African context.

CEOs in the banking industry are among the top-paid CEOs in South Africa. Libera (2024) indicates that the CEOs of the six top commercial banks in RSA earned between R475,425 and R87,485 per day, compared to the average monthly salary of a South African worker, which is R26,894. Scholars such as Deysel and Kruger (2015) and Kieviet et al. (2024) investigated the influence of bank performance on CEO compensation among JSE-listed banks, and both studies found a positive relationship. Coetzee and Bezuidenhout (2019) examined the relationship between CEO pay and performance in state-owned companies in South Africa and found an inverse relationship, despite positive relationships in the banking industry. This connection between company performance and CEO pay has led CEOs to adopt various innovative strategic decisions aimed at enhancing organizational performance.

One of the innovative strategic decisions organizations and banks have made to enhance performance is the adoption of Fintech. Various service providers are increasingly embracing technology to improve stakeholder satisfaction. Fintech is a crucial component of banks’ business strategies, fundamentally transforming their operations (Dwivedi et al., 2021). This transition has enabled banks to streamline their processes and services, resulting in substantial increases in profitability (Gyau et al., 2024). The impact of Fintech on the banking sector is profound, especially regarding its effect on competitiveness and overall bank performance.

A considerable amount of research has been conducted to investigate the implications of Fintech adoption in the banking industry (Pham & Nguyen, 2025). There is limited integration of technology adoption and executive compensation. Fintech research has emphasized operational efficiency, customer experience, and financial inclusion, but has not examined how the adoption of fintech influences executive pay. Conversely, research on CEO compensation primarily focuses on performance metrics and corporate governance, with limited evidence linking technological transformation, particularly fintech, to CEO pay. Emerging markets have been underexplored in terms of executive compensation. These markets are unique, characterized by institutional gaps, regulatory uncertainty, and rapid digitalization driven by necessity. The impact of these conditions on the relationship between fintech and CEO pay remains unknown. Although fintech adoption may be a key strategic goal in banking, it is unclear whether CEO pay packages reflect this priority. This study will provide a definitive investigation into the effects of Fintech on CEO compensation, thereby filling a critical gap in knowledge. Data from six JSE-listed banks will be used to investigate the relationship between Fintech adoption and CEO compensation of these banks. The study aims to answer the following research questions:

What effect does Fintech adoption have on CEO fixed pay?

What is the relationship between fintech adoption and CEO total compensation?

Based on the above research questions, the study’s objectives are as follows:

To determine the relationship between Fintech adoption and CEO fixed compensation.

To investigate the relationship between Fintech adoption and CEO total compensation.

The banking industry is crucial to a nation’s economic development, as it directly reflects a country’s economic and financial strength (Murinde et al., 2022). Mhlongo et al. (2025) assert that the banking sector in South Africa is a key driver of national sustainability and economic growth. The study’s findings provide insights into understanding the role of FinTech or innovation in executive compensation. The following section provides a literature review on executive remuneration, Fintech, and the theoretical framework underpinning the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CEO Compensation

Executive compensation is structured with a fixed pay component and a variable element. The variable element includes cash bonuses and equity-based remuneration (Siwendu & Ambe, 2024). According to Fabrizi (2021), CEO compensation is defined by four essential components: base salary, annual bonus, equity compensation, and long-term incentive plans. The base salary is the fixed component, while the annual bonus is a variable component based on performance. Equity compensation, generally the largest share, is awarded in stock options or restricted stock. Long-term incentive plans, which function similarly to annual bonuses, evaluate performance over 3- to 5-year periods. Watto et al. (2023) opine that executive compensation is categorized into fixed and performance-based components. The fixed component safeguards executives against factors they cannot control. At the same time, performance-based compensation, typically in the form of options and shares, motivates executives to align their interests with those of shareholders (Watto et al., 2023). This study adopts Bussin and Carlson (2020) conceptualization of fixed pay as the basic salary plus benefits, and total compensation as the sum of fixed pay and short-term incentives. Several critical factors influence CEO compensation, including board structures, company size, the influence of institutional investors, and the presence of outside directors (Manuere & Hove, 2018).

2.2. Determinants of CEO Compensation

Ramaswamy et al. (2000) clearly identify that the determinants of CEO pay fall into two distinct categories: human capital variables and governance variables. Human capital variables are rooted in Becker’s (1975) human capital theory, which emphasizes that factors such as training, experience, tenure, and career path play a critical role in shaping CEO compensation. Empirical studies, such as those by Lee and Pati (2024), have been conducted to examine the relationship between these variables and the remuneration of CEOs. On the other hand, governance variables highlight the significant influence of shareholder composition and the board of directors on determining CEO pay (Ramaswamy et al., 2000). In the South African context, Coetzee and Bezuidenhout’s (2019) study supports the idea that industry and the size of an organization are determinants of CEO compensation.

2.3. CEO Pay and Performance

Linking CEO pay to performance is crucial for ensuring that shareholders receive returns that reflect market conditions (Deysel & Kruger, 2015). Company performance is measured using various indicators and is a critical determinant of CEO compensation. Company performance is measured by metrics such as Return on Assets (ROA) and Return on Equity (ROE). Among the various indicators of company performance, Return on Assets (ROA) stands out as the most effective. Kayed et al. (2025) note that ROA is measured as net income divided by total assets and indicates profitability. ROA assesses how well an organization utilizes its assets to generate income (Kamruzzaman, 2019). Zainuddin et al. (2017) affirm that ROA is the most suitable indicator for evaluating bank performance, as it focuses on an organization’s profitability derived from its business activities. Similarly, Akhigbe et al. (2017) assert that a bank’s performance is directly tied to ROA, which also serves as an alternative proxy for controlling bank size. Jensen and Murphy (1990) clearly establish that ROA is crucial in determining executive compensation.

Nulla (2013) examined the relationship between CEO compensation and ROA in firms listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange, revealing no significant correlation. Conversely, Sikawa et al.’s (2020) study on determinants of CEO compensation among FSTE 100 companies found no relationship between return on assets and CEO compensation. Similar results were found by Ngwenya (2016) in a study among listed Platinum mines in South Africa. Given the undeniable importance of ROA as a key performance indicator for bank profitability, this study decisively employs ROA as a control variable to explore the relationship between CEO compensation and fintech adoption.

2.4. CEO Compensation and Growth Rate of Gross Domestic Product (RGDP)

While micro factors largely influence CEO compensation, it is essential to recognize that macro factors also play a significant role in determining CEO compensation. Macroeconomic fluctuations have an impact on the performance-linked compensation of CEOs (Oxelheim et al., 2008). The Gross Domestic Product is one of the macro factors that determine CEO compensation (Oxelheim et al., 2008). Similarly, Luijsterburg (2024) suggests that GDP is considered an exogenous factor influencing CEO compensation. GDP growth indicates an increase in economic growth, firm profitability, and average income; hence, CEOs will be awarded more in relation to GDP growth (Khursheed & Sheikh, 2022). A study by Wijst (2018) confirmed a positive relationship between GDP and CEO compensation. Conversely a study by Luijsterburg (2024) covering an eighteen-year time frame for 43,350 CEOs in Europe found a negative relationship between CEO compensation and GDP.

2.5. Fintech

Fintech is an abbreviation for financial technology, and it has transformed the DNA of banks, offering novel solutions that address gaps in the provision of financial services (Murinde et al., 2022). Mhlongo et al. (2025) note that Fintech in the banking industry relates to technological innovations in financial services, enabling banks to develop new business models, products, and procedures. The authors note that in the South African context, these innovations include M-Pesa, FNB eWallet, and ABSA Cash Send. Such innovations enhance profitability in regions with limited banking infrastructure (Mhlongo et al., 2025). Kayed et al. (2025) argue that fintech adoption mitigates risk-taking behaviors.

Mhlongo et al. (2025) note that Fintech offers efficient, personalized, and cost-effective banking solutions, impacting the banking sector’s competition and performance. In the South African context, Murinde et al. (2022) highlight that Fintech has made it difficult for banks to remain competitive, as it has allowed the entry of new competitors into the industry. On the other hand, Fintech has enhanced financial inclusion, presented banks with reduced costs, and enabled banks to customize financial services, making the banking industry more competitive (Cele & Mlitwa, 2024). Fintech enhances bank competition through its ability to offer alternative financial services, and such competitiveness positively impacts bank performance (Dwivedi et al., 2021). In other words, fintech impacts the performance of banks. Organizational Performance determines CEO payments; the higher the performance, the higher the compensation (Bouteska et al., 2024).

Variables such as phone banking services, internet banking, and automated machines are used to measure Fintech adoption among banks (Kayed et al., 2025). A systematic literature review on Fintech variables by Tarawneh et al. (2024) highlighted that the commonly used variables for Fintech in the banking industry include Money transfer, mobile banking, and ATMs. Empirical findings on the impact of fintech on bank performance contradict. A study by Phan et al. (2020) found an adverse effect of Fintech on bank performance. Similarly, Mugabe (2022) found a negative relationship between fintech and bank performance, while Dwivedi et al. (2021) found a positive relationship between fintech adoption and bank performance in AUE. A study by Kayed et al. (2025) indicated that Fintech adoption enhanced bank profitability among 13 listed banks in Jordan.

In the context of CEO compensation, it is observed that CEOs heavily invest in technology, expecting it to provide a competitive advantage and enhance productivity (Zhou et al., 2021). According to Kim and Brynjolfsson (2009), investments in technology have a positive impact on both firm size and firm value. Numerous studies (Anne et al., 2021; Coetzee & Bezuidenhout, 2019; Hashmi et al., 2020) have demonstrated a positive correlation between company size and CEO compensation. Research conducted by (Li et al., 2024) confirmed that companies that significantly invest in information technology tend to have higher market values and typically offer their CEOs larger salaries. Given the positive impact of technology on company performance, size, and value, this study is based on the following two hypotheses.

H1.

Fintech adoption has a positive and significant effect on CEO salary.

H2.

Fintech adoption positively and significantly affects CEO’s total compensation.

While existing research provides extensive evidence on the factors influencing CEO compensation, such as firm performance, governance structures, risk-taking behavior, and market conditions, few studies specifically examine the impact of strategic technological transformation on executive remuneration. Furthermore, the growing body of fintech literature primarily focuses on its effects on bank performance, customer experience, operational efficiency, and competitive positioning, without addressing how the adoption of fintech influences internal governance mechanisms, such as executive remuneration. This creates a notable gap at the intersection of fintech innovation and compensation policy. There is limited empirical research on whether and how boards reward CEOs for leading digital transformation initiatives or how fintech-driven organizational changes affect the structure or size of CEO pay. This lack of research is especially significant in emerging markets like South Africa, where banks are quickly adopting fintech solutions and CEO compensation remains a topic of public and academic interest. Therefore, this study aims to fill an important gap by examining the relationship between fintech adoption and CEO compensation in JSE-listed banks, a connection that has been largely overlooked in the current literature.

2.6. Conceptual Framework

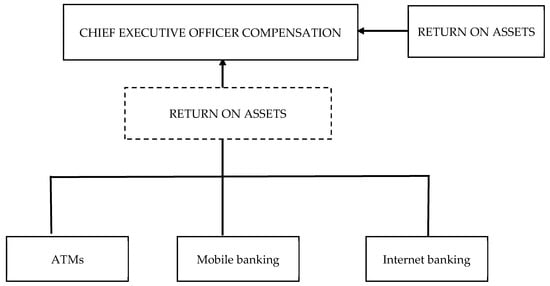

The framework assumes that fintech proxies such as ATMs, Internet banking, and mobile banking are positively linked to CEO compensation through anticipated increased organizational performance resulting from Fintech Adoption. However, the moderating effects of the performance were not put into perspective in this article. The effects of performance, as measured by return on assets, were tested as a control variable. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual framework of the study.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Agency Theory

The agency theory emphasizes the CEO’s crucial role in aligning the interests of shareholders (the principals) with their own, highlighting the importance of company performance in determining executive compensation. Lee and Pati (2024) argue that agency theory examines the relationship between CEO compensation and company performance by aligning the interests of the agent with those of the shareholders. The theory emphasizes the need for the interests of the CEO (the agent) to be aligned with those of the shareholders (Bouteska et al., 2024). According to Jensen and Meckling (1976), an agency problem arises when the agent has an agenda that is contrary to that of the principals, and incentives such as bonuses are used to ensure that the agent’s agenda aligns with that of the principals. Agency theory explains the effect of FinTech adoption on CEO compensation by emphasising how digital transformation intensifies information asymmetry, risk, and monitoring challenges between shareholders and executives. In banking, FinTech investments involve long-term uncertainty, technological complexity, and regulatory exposure, making managerial effort and decision quality harder to observe (Holmström, 1979). As a result, boards use CEO compensation as a governance tool to align managerial incentives with shareholder interests by adjusting both fixed and performance-based pay to encourage commitment, risk-bearing, and long-term value creation (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991; Murphy, 1999).

3.2. Human Capital Theory

Human capital theory explains executive compensation by positing that remuneration reflects the value of executives’ skills, experience, and knowledge that contribute to firm performance and long-term value creation. Awu et al. (2025) note that the theory emphasise that individual specific characteristics such as education, training and work experience enhance CEOs’ ability to perform and generate economic value to an organisation. In this view, CEOs possess heterogeneous and often scarce competencies such as strategic decision-making ability, industry specific expertise, and leadership skills that enhance organisational productivity and justify higher compensation (Becker, 1964). In the context of modern organisations, particularly in technology intensive industries, managerial resources such as ability to make strategic decisions are critical and have practical implications on executive remuneration (Castanias & Helfat, 2001). Consequently, boards design compensation contracts that reward accumulated managerial expertise and capability rather than short-term outcomes alone, leading to higher fixed and long-term compensation components (Gabaix & Landier, 2008). Empirical evidence further supports the human capital perspective by showing that executive pay increases with firm size, complexity, and skill intensity, reflecting the premium placed on distinguished managerial talent and expertise (Frydman & Saks, 2010).

3.3. Managerial Power Theory

Managerial power theory can be used to explain the effect of FinTech adoption on CEO compensation, especially the executive’s influence in the pay-setting process. The theory argues that CEO compensation does not always reflect optimal contracting outcomes, it may be shaped by the relative power of executives over boards, particularly in instances where monitoring is weak or information asymmetries are high (L. Bebchuk & Fried, 2004). In the context of FinTech adoption, the complexity of digital transformation initiatives like mobile banking platforms increase information gaps between CEOs and remuneration committees which strengthens managerial power. CEOs who control critical technological knowledge and strategic direction may leverage this advantage to secure higher and more stable compensation, especially in the form of fixed salaries that are less sensitive to performance (Core et al., 1999). For JSE-listed banks, where FinTech is central to competitiveness, innovation, and financial inclusion, managerial power theory suggests that successful digital leadership can translate into enhanced bargaining leverage and upward pressure on executive pay, independent of short-term financial outcomes (L. A. Bebchuk et al., 2010).

3.4. Disruption Innovation Theory

The disruption innovation theory was advanced by Christen in 1997 (Dan & Chieh, 2008). The theory identifies two types of innovation: sustaining and disruptive, and how simple and affordable products, such as Fintech, can disrupt existing markets. Innovative sustaining improves existing products or services, while disruptive innovation offers affordable and straightforward solutions to underserved customers. Fintech disrupts traditional financial processes and introduces operational efficiency, which reduces costs and enhances customer experience, positively impacting customer retention and revenue growth, which all enhance company performance. Disruptive technologies are characterized by high levels of uncertainty and strategic risk, yet they create long-term value for an organization. This creates an agency problem and necessitates aligning shareholder interests with managerial actions.

4. Methodology

A quantitative research approach was employed, specifically utilizing panel data analysis. The same method was adopted by Kieviet et al. (2024) and Deysel and Kruger (2015) when they investigated the relationship between company performance and CEO compensation of JSE-listed banks. The study sample comprised six commercial banks listed on the JSE, and data were collected from 2010 to 2024. Choi and Lam (2017) note that a minimum of 10 observations per variable is sufficient to produce statistically sound results. The data was sourced from the Bank’s financial statements and the IRESS database.

The researchers carefully selected credible and relevant datasets, assessing their completeness, comparability, and statistical appropriateness. They prepared the data by cleaning, coding, and verifying it to enhance the study’s validity and methodological rigor. An appropriate analytical framework was then constructed by defining variables, choosing suitable quantitative techniques, and specifying models that align with the study’s theoretical foundation. During the analysis, the researchers conducted diagnostic tests to identify and address potential biases present in the secondary data, such as missing values, measurement inconsistencies, and limited variable options. Finally, they interpreted the empirical findings objectively, placing them in the context of existing literature. The following section discusses the sample description, as well as the dependent and independent variables.

4.1. Variables

The dependent variable data were sourced from the annual integrated reports of the banks, IRESS as well as the Reserve Bank of South Africa’s website. Exploratory variables were also sourced from the Annual integrated reports of the banks and verified on the Reserve Bank of South Africa website. Control variables were also sourced from the integrated annual reports and the Reserve Bank of South Africa website. Table 1 summarises variables for the study

Table 1.

Definition of variables.

4.2. Model Specification

The study evaluates the hypotheses using a fixed effects model. The baseline panel regression model was specified as follows:

where the subscript i denotes the bank (i = 1, 2, …, 6), and t represents the fiscal year (2009, 2010, …, 2024). Accordingly, , β, and ε denote the intercept, the coefficient estimates, the individual fixed effects, and the error term, respectively. CEO compensation is measured using two proxy variables: total CEO compensation and CEO salary, hence the two equations.

The study employed a fixed effects model rather than the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) approach, as the number of time periods (T), 15 years, exceeded the number of entities (N), six. GMM is generally preferred when N exceeds T. Additionally, the F-test for poolability or individual effects yielded significant results, indicating that fixed effects were the most appropriate method for this analysis. Moreover, the Hausman test was also significant, further confirming the suitability of the fixed effects model for the study.

4.3. Preliminary Analysis

Table 2 shows the descriptive summary of the study.

Table 2.

Descriptive results.

Table 2 summarises the descriptive statistics of the study. The findings indicate that the highest total compensation earned by a CEO in the banking sector during the research period was R77.3 million, with an average compensation of R24.5 million and a minimum of R6.3 million. The maximum salary, which encompasses both basic salary and benefits, reached R23.1 million. The average salary was R9.1 million, with a minimum of R3.5 million. The analysis reveals that the number of mobile bank accounts per 1000 adults peaked at 670, with an average of 428.5 and a minimum of 200. The ATM explanatory variable demonstrated a maximum of 15, an average of 10.3, and a minimum of 5 during the investigated period. Internet banking (IB), another crucial explanatory variable, saw a maximum of 980 accounts, an average of 716.2, and a minimum of 1 account. The control variables included RGDP, which reached a maximum of R7.2 trillion, averaged R4.6 trillion, and had a minimum of R3.1 trillion. Lastly, ROA, another important control variable, showed a maximum of 62.34, an average of 1.88, and a minimum of 0.42.

4.4. Correlation Analysis

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix, which indicates the strength and direction of the relationships between pairs of variables and whether any multicollinearity exists among the variables. Mobile banking exhibited a significantly strong correlation with total compensation, while the correlation was positive with the fixed salary. The relationship between ATMs and total compensation, as well as the fixed salary, was inverse. This implies that ATMs, as an innovation, did not impact CEO compensation, both the Fixed Salary and the total compensation. The correlation between internet banking and fixed salary was negative and significant. A positive and significant correlation was also evident between RGDP and salary, with the impact on the fixed salary remaining positive, although not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis Summary.

5. Empirical Results and Discussion

A series of diagnostic tests were performed on the pooled OLS, fixed effects, and random effects models to identify the most appropriate model specification, as reported in Table 4 and Table 5. These included tests for the joint validity of cross-sectional individual effects, the Breusch–Pagan Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test for random effects (Breusch & Pagan, 1980), the Hausman specification test for heterogeneity (Hausman, 1978) and cross-sectional independence. The Hausman test produced a statistically significant result, indicating that the regressors were not exogenous; therefore, the fixed effects model was deemed the most appropriate specification. Furthermore, the Chow test (F-test) assessing poolability and the presence of individual effects was also significant, further supporting the robustness of the fixed effects approach. The Breusch–Pagan LM test was additionally employed to examine the presence of homoscedasticity and serial correlation. Although the results suggested no evidence of serial correlation, the residuals were found to be heteroscedastic. To address this issue, the fixed effects model was estimated using Driscoll and Kraay’s robust standard errors, which are robust to heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional dependence. All the diagnostic statistics are presented in the Appendix A as Table A3, Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6. Also, for robustness the same models were rerun with lagged variables and the results were presented in Table A1 and Table A2 in the Appendix A.

Table 4.

The effects of FinTech on Chief Executive Officer Fixed Salary.

Table 5.

Effects of FinTech on Banks’ Total Executive Compensation.

There is a significant relationship between mobile banking and the fixed salary of CEOs. Holding all else constant, an additional mobile banking account per 1000 adults is associated with approximately 0.427% increase in executive fixed compensation. The significant relationship between mobile banking and CEOs’ fixed salaries indicates that the expansion of mobile banking is associated with positive adjustments in guaranteed executive pay, reflecting the long-term and strategic nature of this technology. Mobile banking represents a core digital transformation that expands banks’ customer reach, supports financial inclusion, and requires sustained investment in digital infrastructure, cybersecurity, and regulatory compliance (Balogun, 2024). These structural changes increase organisational complexity and the scope of managerial oversight (Ojonugwa et al., 2023), leading boards to compensate CEOs through higher fixed salaries that recognise permanent increases in responsibility rather than short-term performance outcomes.

This is in line with the human capital perspective, successful mobile banking strategies demand specialised executive skills in digital leadership, innovation management, and platform governance, which enhance the scarcity and firm-specific value of CEOs and justify higher base compensation (Becker, 1964; Castanias & Helfat, 2001). In addition, optimal contracting theory suggests that remuneration committees adjust fixed pay to reflect heightened risk exposure and effort associated with managing long-term digital transformation, particularly where outcomes are uncertain and not immediately observable (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991; Murphy, 1999). Overall, the result underscores mobile banking as a determinant of CEO fixed salaries, signaling that boards reward sustained strategic and technological oversight rather than transient financial performance, consistent with evidence that executive pay responds to increases in firm complexity and technological intensity (Frydman & Saks, 2010).

The results demonstrate a positive and significant relationship between the rollout of ATMs and the CEO’s fixed salary. Assuming all other factors remain constant, adding one ATM per 100,000 adults is linked to an approximate 5.94% increase in fixed compensation. As banks innovate through the introduction of ATMs, the CEOs’ salaries correspondingly increase. The positive and significant relationship between the rollout of automated teller machines (ATMs) and CEOs’ fixed salaries suggests that the expansion of ATM networks is associated with increased managerial responsibility and organisational complexity, which is reflected in higher fixed salary payments. Although ATMs represent a relatively mature banking technology, their rollout and maintenance like other bank innovations require strategic leadership (Ojonugwa et al., 2023). From a human capital perspective, overseeing geographically dispersed delivery channels and integrating physical infrastructure with digital banking systems increases the value of CEO expertise and experience in strategic leadership, justifying higher fixed remuneration (Becker, 1964; Castanias & Helfat, 2001). In addition, agency and optimal contracting theories suggest that boards may adjust CEOs’ guaranteed pay to compensate for the long-term commitment and risk-bearing associated with the rollout and managing extensive ATM networks, particularly where returns accrue gradually rather than immediately (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991). Overall, the result indicates that fintech in the form of ATM rollout is a structural determinant of executive compensation, reflecting persistent increases in operational scale and strategic complexity rather than short-term performance effects (Frydman & Saks, 2010). Alomari et al. (2020) emphasize that ATMs are critical innovations that banks utilize to enhance their performance and profitability. Furthermore, the utilization of ATMs directly contributes to cost efficiency for banks, as highlighted by Oboke et al. (2022). This efficiency is vital, as it has a direct positive impact on bank profitability and overall performance. Research conducted by Mutiso and Senelwa (2017) on 11 listed banks in Kenya confirms a significant positive relationship between the rollout of ATMs and Return on Assets (ROA). Additionally, Shaw and Zhang (2010) affirm that there is a positive correlation between the CEO’s cash compensation and ROA. Ahamed (2022) also reinforces this by demonstrating a strong correlation between bank performance and the fixed salaries of CEOs in Bangladesh. The findings indicate that the positive and significant relationship arises from the influential impact of ATM rollout on bank performance and profitability, evidenced by enhanced ROA and improved cost efficiency. The increase in managerial responsibility and the importance of strategic leadership from CEOs to ensure the success of innovations such as strategic leadership positively affect CEO fixed salary. Consequently, boards and regulators need to reassess whether remuneration policies prioritize value creation over asset growth.

A statistically significant negative relationship exists between internet banking and the CEO’s fixed salary. Holding everything else constant, adding one more internet banking account for every 1000 adults is associated with a reduction of approximately 0.0209% in fixed compensation. The statistically significant negative relationship between internet banking and CEOs’ fixed salaries indicates that greater adoption of internet banking is associated with lower guaranteed executive compensation, suggesting that this form of digitalisation may reduce, rather than increase, the long-term structural demands placed on top management. Internet banking platforms tend to automate routine transactions, lower marginal operating costs, and streamline branch-based and back-office processes, thereby reducing organisational complexity and managerial oversight requirements at the executive level (DeYoung et al., 2007). From an optimal contracting perspective, when technology improves efficiency and predictability of operations, boards may perceive a reduced need to compensate CEOs through higher fixed salaries, instead favoring performance linked incentives (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991).

Furthermore, internet banking is generally a more standardised and widely diffused technology compared to newer FinTech innovations, limiting the extent to which CEOs can leverage specialised human capital or informational advantages in compensation negotiations (Becker, 1964; Gabaix & Landier, 2008). As digital processes become institutionalised and less CEO specific, managerial power on pay setting may weaken, leading to downward pressure on fixed compensation (L. Bebchuk & Fried, 2004). Overall, the negative relationship suggests that internet banking functions as an efficiency enhancing technology that substitutes for managerial input at the strategic level, thereby reshaping executive pay structures by lowering fixed salaries while potentially shifting remuneration toward variable or performance-based components (Frydman & Saks, 2010).

The study’s findings also reveal a positive and significant relationship between ROA and both fixed salary and total compensation. With everything else held constant, a 1% increase in return on assets results in a 1.21% rise in fixed salary, while the same increase in return on assets correlates with a 23.5% increase in total compensation. The findings of the study are in line with Zandi et al.’s (2019) study, which found a positive correlation between CEO compensation and ROA. A similar study by Ndofirepi (2015) in South Africa found a positive and significant relationship between ROA and CEO compensation, both the fixed salary and total compensation.

There is a positive and significant relationship between mobile banking and total compensation. Keeping other factors constant, adding one more internet banking account for every 1000 adults is associated with an approximate 10.6% increase in fixed compensation. The positive and significant relationship between mobile banking and total CEO compensation indicates that the expansion of mobile banking is strongly associated with higher overall executive pay, reflecting the strategic importance of this technology in modern banking. Mobile banking represents a core FinTech innovation that reshapes customer acquisition, financial inclusion, revenue diversification, and competitive positioning, thereby increasing the strategic responsibilities and risk exposure borne by CEOs (Frame & White, 2014). From an optimal contracting and agency perspective, boards may respond to these heightened demands by increasing total compensation to align managerial incentives with shareholder interests and to reward sustained effort in overseeing complex digital transformation initiatives (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991; Murphy, 1999).

This is also in line with the human capital theory thatsuggests distinct CEO characteristics and abilities determine CEO compensation. Mobile banking intensifies demand for CEOs with specialized digital leadership, platform management, and innovation capabilities, which enhances executive market value and justifies higher overall remuneration (Becker, 1964; Castanias & Helfat, 2001). Mobile banking strategies also often involve long-term investments, partnerships with fintech firms, and exposure to cybersecurity and regulatory risks, making performance outcomes uncertain and strengthening the case for higher total compensation that combines fixed pay and long-term incentives (Edmans & Gabaix, 2016). Moreover, from a managerial power theory perspective CEOs who successfully champion mobile banking initiatives may gain greater influence on compensation setting processes due to increased informational asymmetries and organisational dependence on their technological expertise (L. Bebchuk & Fried, 2004). Overall, the result underscores mobile banking as a key determinant of total executive compensation, capturing its role in driving strategic complexity, innovation-led growth, and long-term value creation in the banking sector (Frydman & Saks, 2010).

There is a negative and significant relationship between ATMs and TC and IB. This indicates that as the number of ATMs increased and the banks intensified IB, the CEO’s TC decreased. Maintaining all other factors constant, adding one more internet banking account for every 1000 adults is associated with an approximate 3.96% decrease in total compensation, while an additional ATM for every 100,000 adults leads to a 1.61% decline in total compensation. This suggests that the adoption of ATMs and IBs did not have a positive impact on the compensation of CEOs tied to long-term performance. Internet banking and ATMs automates routine transactions, reduces dependence on physical branches and labour, and lowers operational costs, thereby diminishing organisational complexity and the intensity of strategic oversight required from top management (DeYoung et al., 2007). From an optimal contracting perspective, when technological adoption improves operational efficiency and predictability, boards may rationally restrain total compensation especially performance-based compensation because managerial effort and risk exposure linked to innovation are perceived to be lower (Holmström & Milgrom, 1991; Murphy, 1999). In addition, from a human capital theory standpoint internet banking does not substantially increase the scarcity or firm-specific value of CEO skills, as it represents a conventional and widely diffused technology across the banking sector (Becker, 1964; Gabaix & Landier, 2008). As digital processes become institutionalised and embedded within standard operating systems, managerial discretion and informational advantages decline, weakening CEOs’ bargaining power on pay structures (L. Bebchuk & Fried, 2004). Overall, the negative association implies that internet banking and ATMs function primarily as a cost-saving and efficiency enhancing innovation rather than a strategic growth catalyst, prompting remuneration committees to moderate total CEO compensation and align pay more closely with efficiency gains rather than technological expansion (Frydman & Saks, 2010).

6. Limitations

The study was limited to JSE-listed commercial banks and excluded the other 10 banks operating in South Africa. Although the use of panel data produced 90 observations, this amount is adequate but only marginally so. The study only used traditional fintech instruments due to the unavailability of data on unconventional fintech instruments. The total compensation variable used in the study included fixed pay and short-term incentives, excluding long-term incentives such as equity pay. The study also used purposive sampling, which is prone to researcher bias.

7. Recommendations

Future research can focus on examining the mediating role of company size in the relationship between CEO compensation and Fintech adoption. Future research can also investigate Fintech adoption in other financial organizations, beyond banks, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of Fintech adoption on CEO compensation. A comparative study between developed and developing economies can add more value to understanding the role of technology in CEO compensation, as Fintech adoption can be influenced by regulations found in different economies. Future studies can focus on investigating Fintech adoption on CEO long term incentives.

8. Conclusions

The study aimed at investigating the effect of Fintech adoption on CEO Compensation and total compensation. The findings of this study highlight a complex connection between banking innovation and CEO compensation. Mobile banking and ATM rollout are both positively and significantly associated with the fixed salaries of CEOs, primarily due to their immediate and substantial impact on profitability, as measured by ROA. The relationship confirmed the first hypothesis, which predicted a positive relationship between fintech adoption and CEO fixed salary. Additionally, mobile banking has a positive impact on the CEO’s total compensation, likely because it enhances bank profitability through revenue from small transactions and increased operational efficiency. This finding was also in line with the second hypothesis, which predicted a positive relationship between CEO total compensation and fintech adoption. On the other hand, Internet banking exhibits a negative and significant correlation with CEO fixed pay, which contradicts the study’s first hypothesis. The expansion of ATMs, along with increased Internet banking, also demonstrates a significant negative relationship with total compensation, which is contrary to the second hypothesis of the study, which predicted a positive relationship between fintech adoption and CEO total compensation. This suggests that innovations with high fixed and operating costs can delay or diminish performance-based incentives emanating from fintech adoption.

The study’s findings suggest that boards and remuneration committees should carefully design CEO compensation packages that reflect which innovations truly enhance value. The high costs and negative impacts associated with ATMs and Internet banking indicate that simply expanding physical or digital infrastructure should not be automatically rewarded. Instead, compensation should be based on measurable net returns rather than just gross scale. The negative relationships observed with ATMs and Internet banking underscore the importance of effective cost management. Banks should not only invest in digital infrastructure but also manage their operating costs, including maintenance and other overhead costs. They should strive to improve efficiencies in these innovations to potentially contribute positively to compensation or profitability.

The study broadens agency theory by incorporating the role of Fintech innovation dynamics into executive compensation design. Traditional agency theory focuses on aligning CEO incentives with shareholder wealth through performance-based pay; however, the rise of Fintech brings new strategic challenges and risk factors that challenge traditional metrics, thus shifting the pay-performance link in the era of digital disruption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R.M. and F.M.; methodology, R.R.M. and F.M.; software, R.R.M.; validation, R.R.M. and F.M.; formal analysis, R.R.M. and F.M.; investigation, R.R.M. and F.M.; resources, R.R.M. and F.M.; data curation, R.R.M. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.M. and F.M.; writing—review and editing, R.R.M. and F.M.; visualization, R.R.M. and F.M.; supervision, F.M.; project administration, F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in IRESS database and bank financial statements [IRRESS] [https://www.iress.com/]. Access date: 16 June 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The effects of lagged FinTech on Chief Executive Officer Salary (Robustness).

Table A1.

The effects of lagged FinTech on Chief Executive Officer Salary (Robustness).

| Models | Pooled Effects | Fixed Effects | Random Effects | FGLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sal | Sal | Sal | Sal | |

| L.MB | 0.000540 | 0.00234 *** | 0.000540 | −0.000237 |

| (0.000391) | (0.000665) | (0.000391) | (0.000167) | |

| L.ATMs | 0.0194 | 0.0683 *** | 0.0194 | −0.0130 * |

| (0.0112) | (0.0148) | (0.0112) | (0.00530) | |

| L.IB | −0.000188 * | −0.00122 *** | −0.000188 * | −0.000234 ** |

| (0.0000772) | (0.0000707) | (0.0000772) | (0.0000805) | |

| ROA | −0.00255 | −0.00156 | −0.00255 | −0.00300 |

| (0.00174) | (0.00157) | (0.00174) | (0.00184) | |

| LRGDP | 0.800 ** | 0.0734 | 0.800 ** | 1.020 *** |

| (0.246) | (0.398) | (0.246) | (0.150) | |

| COVID_19 | −0.00197 | −0.0377 | −0.00197 | 0.0150 |

| (0.0306) | (0.0292) | (0.0306) | (0.0319) | |

| _cons | −1.676 | 1.856 | −1.676 | −2.447 * |

| (1.514) | (2.394) | (1.514) | (0.974) | |

| N | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 |

Robust Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A2.

Effects of lagged FinTech on Banks’ Total Executive Compensation (Robustness).

Table A2.

Effects of lagged FinTech on Banks’ Total Executive Compensation (Robustness).

| Pooled Effects | Fixed Effects | Random Effects | FGLS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | TC | TC | TC | TC |

| L.MB | 0.00127 ** | −0.00137 | 0.00127 ** | 0.00149 *** |

| (0.000437) | (0.00111) | (0.000437) | (0.000257) | |

| L.ATMs | 0.0372 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.372 *** | 0.468 *** |

| (0.0133) | (0.0248) | (0.0133) | (0.00819) | |

| L.IB | 0.0972 *** | 0.0350 *** | 0.00972 *** | −0.0122 *** |

| (0.000122) | (0.000118) | (0.000122) | (0.000124) | |

| ROA | 0.00257 | 0.00181 | 0.00257 | 0.00315 |

| (0.00276) | (0.00263) | (0.00276) | (0.00284) | |

| LRGDP | 0.282 | 2.077 ** | 0.282 | 0.117 |

| (0.301) | (0.666) | (0.301) | (0.232) | |

| COVID_19 | −0.0719 | −0.0305 | −0.0719 | −0.0733 |

| (0.0482) | (0.0489) | (0.0482) | (0.0493) | |

| _cons | 1.928 | −9.128 * | 1.928 | 2.992 * |

| (1.884) | (4.004) | (1.884) | (1.506) | |

| N | 84 | 84 | 84 | 84 |

Robust Standard errors in parentheses * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table A3.

Diagnostic Statistical Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO Salary.

Table A3.

Diagnostic Statistical Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO Salary.

| Test | Test Statistic | p-Value | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint validity of cross-sectional individual effects H0: α 1 = α2 = ⋯ αN−1 = 0 HA: α1 ≠ α2 ≠ ⋯ αN−1 ≠ 0 | F = 12.44 | 0.0000 | Cross-sectional individual effects are valid. |

| Breusch and Pagan (1980) LM test for random effects H0: δμ2 = 0 HA: δμ2 ≠ 0 | LM = 1.92 | 0.2106 | Random effects are not present. Random effects model is not preferred. |

| Hausman (1978) specification test H0: E(μit|Xit) = 0 HA: E(μit|Xit) ≠ 0 | Chi2 = 47.93 | 0.0000 | Regressors not exogenous. Hence the Fixed effects specification is valid. |

| Heteroscedasticity H0: δi2 = δ for all i HA: δi2 ≠ δ for all i | LM = 9.92 | 0.0016 | The variance of the error term is not constant. Heteroscedasticity is present. The fixed effects model with Driscoll and Kraay Standard Errors estimator was used as the solution to heteroscedasticity problems. |

| Pesaran’s test of cross-sectional independence | CSD = 0.580 | 0.5477 | Cross-sectional independence |

Table A4.

VIF Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO Salary.

Table A4.

VIF Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO Salary.

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 2.48 | 0.4027 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| LGDP | 1.90 | 0.5270 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| ATMs | 1.75 | 0.5705 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| ROA | 1.23 | 0.8159 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| COVID_19 | 1.20 | 0.8367 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| IB | 1.18 | 0.8458 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| Mean VIF | 1.62 | No problem of multicollinearity |

Table A5.

Diagnostic Statistical Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO’s Total Compensation.

Table A5.

Diagnostic Statistical Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO’s Total Compensation.

| Test | Test Statistic | p-Value | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint validity of cross-sectional individual effects H0: α1 = α2 = ⋯ αN−1 = 0 HA: α1 ≠ α2 ≠ ⋯ αN−1 ≠ 0 | F = 4.62 | 0.0010 | Cross-sectional individual effects are valid. |

| Breusch and Pagan (1980) LM test for random effects H0: δμ2 = 0 HA: δμ2 ≠ 0 | LM = 0.44 | 0.4733 | Random effects are not present. Random effects model is not preferred. |

| Hausman (1978) specification test H0: E(μit|Xit) = 0 HA: E(μit|Xit) ≠ 0 | Chi2 = 22.01 | 0.0000 | Regressors not exogenous. Hence the Fixed effects specification is valid. |

| Heteroscedasticity H0: δi2 = δ for all i HA: δi2 ≠ δ for all i | LM = 14.31 | 0.0002 | The variance of the error term is not constant. Heteroscedasticity is present. The fixed effects model with Driscoll and Kraay Standard Errors estimator was used as the solution to heteroscedasticity problems. |

| Pesaran’s test of cross-sectional independence | CSD = −0.701 | 0.4830 | Cross-sectional independence |

Table A6.

VIF Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO’s Total Compensation.

Table A6.

VIF Tests for Assessing FinTech Effects on CEO’s Total Compensation.

| Variable | VIF | 1/VIF | Verdict |

|---|---|---|---|

| MB | 2.48 | 0.4027 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| LGDP | 1.90 | 0.5270 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| ATMs | 1.75 | 0.5705 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| ROA | 1.23 | 0.8159 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| COVID_19 | 1.20 | 0.8367 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| IB | 1.18 | 0.8458 | No problem of multicollinearity |

| Mean VIF | 1.62 | No problem of multicollinearity |

References

- Ahamed, F. (2022). CEO compensation and performance of banks. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 7(1), 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhigbe, A., McNulty, J. E., & Stevenson, B. A. (2017). Does the form of ownership affect firm performance? Evidence from US bank profit efficiency before and during the financial crisis. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 64, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, M. W., Bashayreh, A., & Abdelhadi, S. (2020). Jordanian banking system: An analysis of technical efficiency and performance. Financial Studies, 24(3), 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Anne, O., K’obonyo, P., & Muindi, F. (2021). Influence of firm size on CEOs’ compensation. Journal of Business and Economic Development, 6(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awu, E., Darius, B., & Chimele, P. (2025). Human Capital Theory: Viewing Employees as Organizational Asset. International Journal of Academic Management Science Research, 9(3), 370–375. [Google Scholar]

- Balogun, A. Y. (2024). Cybersecurity in mobile fintech applications: Addressing the unique challenges of securing user data. SSRN 5095825. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5095825 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Bebchuk, L., & Fried, J. (2004). Pay without performance (Vol. 29). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bebchuk, L. A., Cohen, A., & Spamann, H. (2010). The wages of failure: Executive compensation at Bear Stearns and Lehman 2000–2008. Yale Journal on Regulation, 27, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G. S. (1975). Investment in human capital: Effects on earnings. In Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (2nd ed., pp. 13–44). NBER. Available online: https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c3733/c3733.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Blanes, F., de Fuentes, C., & Porcuna, R. (2020). Executive remuneration determinants: New evidence from meta-analysis. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 33(1), 2844–2866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouteska, A., Gupta, A. D., Boden, B., & Abedin, M. Z. (2024). Who affects CEO compensation? Firm performance, ownership structure, and board diversity. The Journal of High Technology Management Research, 35(2), 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. The Review of Economic Studies, 47(1), 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussin, M. H., & Carlson, C. (2020). Relationship between executive pay and company financial performance in South African state-owned entities. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), a1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanias, R. P., & Helfat, C. E. (2001). The managerial rents model: Theory and empirical analysis. Journal of Management, 27(6), 661–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cele, S. K., & Mlitwa, N. W. (2024). Fintechs in South Africa: Impact on regulation, incumbents, and consumers. South African Journal of Information Management, 26(1), 1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. W., & Lam, D. M. H. (2017). Regression: How much data do I really need? Anesthesia, 72(8), 1029–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, M., & Bezuidenhout, M. L. (2019). The relationship between chief executive officer compensation and the size and industry of South African state-owned enterprises. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(1), a1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, J. E., Holthausen, R. W., & Larcker, D. F. (1999). Corporate governance, chief executive officer compensation, and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 51(3), 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Y., & Chieh, H. C. (2008, July 27–31). A reflective review of disruptive innovation theory. PICMET’08-2008 Portland International Conference on Management of Engineering & Technology (pp. 402–414), Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R., Lang, W. W., & Nolle, D. L. (2007). How the Internet affects output and performance at community banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(4), 1033–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deysel, B., & Kruger, J. (2015). The relationship between South African CEO compensation and company performance in the banking industry. Southern African Business Review, 19(1), 137–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P., Alabdooli, J. I., & Dwivedi, R. (2021). Role of FinTech adoption for competitiveness and performance of the bank: A study of the banking industry in the UAE. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness, 16(2), 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmans, A., & Gabaix, X. (2016). Executive compensation: A modern primer. Journal of Economic literature, 54(4), 1232–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizi, M. (2021). Determinants and consequences of executive compensation. Padova University Press. Available online: https://www.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/download-count/attachments/2023-09/9788869382857.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Frame, W. S., & White, L. J. (2014). Technological change, financial innovation, and diffusion in banking. In The Oxford handbook of banking (pp. 486–507). OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Frydman, C., & Saks, R. E. (2010). Executive compensation: A new view from a long-term perspective, 1936–2005. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(5), 2099–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaix, X., & Landier, A. (2008). Why has CEO pay increased so much? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(1), 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyau, E. B., Appiah, M., Gyamfi, B. A., Achie, T., & Naeem, M. A. (2024). Transforming banking: Examining the role of AI technology innovation in boosting banks’ financial performance. International Review of Financial Analysis, 96, 103700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, S. D., Gulzar, S., Ghafoor, Z., & Naz, I. (2020). Sensitivity of firm size measures to practices of corporate finance: Evidence from BRICS. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Holmström, B. (1979). Moral hazard and observability. The Bell Journal of Economics, 10, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, B., & Milgrom, P. (1991). Multitask principal–agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 7, 24–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyke, B. N. (2020). Economic Policy Uncertainty during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Asian Economics Letters, 1(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Murphy, K. J. (1990). Performance pay and top-management incentives. Journal of Political Economy, 98(2), 225–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamruzzaman, M. (2019). Impact of the financial factors on return on assets (ROA): A study on ACME. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 12(1), 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayed, S., Alta’any, M., Meqbel, R., Khatatbeh, I. N., & Mahafzah, A. (2025). Bank FinTech and bank performance: Evidence from an emerging market. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting, 23(2), 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, M., & Masenge, A. (2015). Examining the relationship between CEO remuneration and the performance of central commercial banks in South Africa. Corporate Ownership & Control, 13(1), 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khursheed, A., & Sheikh, N. A. (2022). Determinants of CEO compensation: Evidence from Pakistan. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 22(6), 1222–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieviet, S., Scholtz, H. E., & Pietersen, L. A. (2024). The relationship between company performance and CEO remuneration in the South African banking sector. Southern African Journal of Accountability and Auditing Research, 26(1), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. H., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2009). CEO compensation and information technology. International conference on information systems proceedings. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/venue?name=International%20Conference%20on%20Interaction%20Sciences (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Lee, J., & Pati, N. (2024). Benchmarking executive compensations: Exploring fresh perspectives on chief executive officer (CEO) compensation drivers in major US corporations. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 32(8), 2861–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Xie, B., Chen, X., & Fu, Q. (2024). Corporate digital transformation, governance shifts and executive pay-performance sensitivity. International Review of Financial Analysis, 92, 103060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libera, M. (2024). The top-paid CEOs in South Africa. BusinessTech. Available online: https://businesstech.co.za/news/banking/773369/the-top-paid-banking-ceos-in-south-africa/#:~:text=Thanks%20to%20a%20stronger%20currency%2C%20Investec%20CEO%20Fani,double%20that%20of%20the%20next%20closest%20banking%20CEO (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Luijsterburg, M. (2024). The effects of macroeconomic factors on CEO compensation [Master’s thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- Manuere, F., & Hove, P. (2018). A literature review of the perspectives of CEO pay: An analysis of issues and controversies. Journal of Public Administration and Government, 8, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marozva, G., & Makina, D. (2020). Liquidity risk and asset liability mismatches: Evidence from South Africa. Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 44(1), 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, N., Kunjal, D., & Muzindutsi, P. F. (2025). The influence of fintech innovations on bank competition and performance in South Africa. Modern Finance, 3(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugabe, L. M. (2022). The impact of fintech on banking performance in South Africa [Master’s thesis, University of Cape Town]. Available online: https://open.uct.ac.za/server/api/core/bitstreams/562785ad-3521-4f82-85c8-1d256aaae051/content (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Murinde, V., Rizopoulos, E., & Zachariadis, M. (2022). The impact of the FinTech revolution on the future of banking: Opportunities and risks. International Review of Financial Analysis, 81, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. J. (1999). Executive compensation. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 2485–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutiso, C., & Senelwa, A. W. (2017). Effect of automated teller machines on the return on assets of the listed commercial banks in Kenya. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 19, 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ndofirepi, T. P. (2015). The relationship between CEO compensation and various performance indicators in South Africa. University of the Witwatersrand. Available online: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/items/469c2fb0-8907-4b75-acf3-4b311b1365b5 (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- Ngwenya, S. (2016). CEO compensation, corporate governance, and performance of listed platinum mines in South Africa. Corporate Ownership and Control, 13(2), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nulla, Y. (2013). The effect of return on assets (ROA) on the CEO compensation system in TSX/S&P and NYSE index companies. International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 4(2), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Oboke, N. T., Patrick, K., & Daisy, B. (2022). The effect of automated teller machines on the financial performance of commercial banks listed on the Nairobi securities exchange, Kenya. IOSR Journal of Business and Management (IOSR-JBM), 24(4), 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojonugwa, B. M., Adanigbo, O. S., & Ogunwale, B. (2023). Framework for strategic leadership in banking to achieve resilient economic growth. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Growth Evaluation, 1(2), 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxelheim, L., Wihlborg, C., & Zhang, J. (2008). Executive compensation and macroeconomic fluctuations. Markets and Compensation for Executives in Europe, 12(3), 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P. T., & Nguyen, D. T. (2025). The effects of the fintech company growth on bank performance through balanced scorecard—A Delphi study. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 9(2), 240–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D. H. B., Narayan, P. K., Rahman, R. E., & Hutabarat, A. R. (2020). Do financial technology firms influence bank performance? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 62, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, K., Veliyath, R., & Gomes, L. (2000). A study of the determinants of CEO compensation in India. MIR: Management International Review, 40, 167–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, K. W., & Zhang, M. H. (2010). Is CEO cash compensation punished for poor firm performance? The Accounting Review, 85(3), 1065–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikawa, T. O., Lu, Y., & Latif, A. (2020). Determinants of CEO compensation: An Empirical Study of the FTSE 100 Companies. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 22(5), 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Siwendu, T. O., & Ambe, C. M. (2024). A systematic literature review on transparency in executive remuneration disclosures and their determinants. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(10), 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarawneh, A., Abdul-Rahman, A., Mohd Amin, S. I., & Ghazali, M. F. (2024). A systematic review of fintech and banking profitability. International Journal of Financial Studies, 12(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuteberg. (2025). Understanding CEO pay ratios and wage inequalities. Labour Research Services. Available online: https://lrs.org.za/2025/07/24/understanding-ceo-pay-ratios-and-wage-inequality/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Watto, W. A., Fahlevi, M., Mehmood, S., Asdullah, M. A., & Juhandi, N. (2023). Executive compensation: A justified reward or a mis-fortune, an empirical analysis of banks in Pakistan. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 9(3), 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijst, N. (2018). The influence of CEO compensation on firm performance and its relation to economic growth [Masters’s thesis, University of Radboud]. Available online: https://theses.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/123456789/6215/Wijst,_Nick,_van_der_1.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Zainuddin, P., Wancik, Z., Rahman, S. A., Hartati, S., & Rahman, F. (2017). Determinant of financial performance on Indonesian banks through return on assets. International Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 15(20), 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Zandi, G., Mohamad, S., Keong, O. C., & Ehsanullah, S. (2019). CEO compensation and firm performance. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 7(7), 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B., Li, Y. M., Sun, F. C., & Zhou, Z. G. (2021). Executive compensation incentives, risk level and corporate innovation. Emerging Markets Review, 47, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.