Abstract

Between 2018 and 2025, alternative finance expanded while micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises in emerging economies continued to face a substantial funding gap. This study examines how entrepreneurial frugality articulates frugal ecosystems, access to alternative finance, resilience and SME performance within a single explanatory framework. Following PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S, we conduct a systematic review of Scopus, Web of Science and Cairn; out of 1483 records, 106 peer-reviewed studies are retained and assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and a narrative synthesis approach. The findings show that frugal ecosystems characterized by pooled assets, norms of repair and modularity, and lightweight digital tools reduce experimentation costs and develop frugal innovation as an organizational capability. This capability enhances access to alternative finance by generating readable quality signals, while non-bank channels provide a financial buffer that aligns liquidity with operating cycles and strengthens entrepreneurial resilience. The article proposes an operationalized conceptual model, measurement guidelines for future quantitative surveys, and public policy and managerial implications to support frugal and inclusive innovation trajectories in emerging contexts.

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurial frugality refers to designing solutions that remain as simple as possible while still robust enough to create value in contexts where access to resources, skills, and capital is structurally constrained. In emerging economies, this logic is not an ascetic minimalism. It materializes in ecosystems that pool assets, normalize repairability and modularity, and rely on support organizations such as incubators and innovation hubs to translate local ingenuity into measurable performance trajectories. In this article, we use the term frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems to denote meso-level arrangements in which shared infrastructures, norms of repair and modularity, and support organizations and collective learning under constraint jointly lower the cost of experimentation and make innovation accessible and robust for resource-constrained entrepreneurs.

Two current signals are reshaping the landscape. On one side, the European Union has completed the operationalization of the ECSP framework, which harmonizes crowdfunding rules and introduces a European passport allowing licensed platforms to operate cross-border under a single authorization. This reduction in frictions in alternative capital markets opens new windows for co-financing projects originating from incubators and hubs connected to Euro-African innovation chains (European Commission, 2023). On the other side, the African Continental Free Trade Area continues to scale up. Despite uneven execution, intra-African flows are rising, while payment interconnection through the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System, already linked to several central banks, aims to reduce settlement frictions in third currencies, a decisive lever for small- and medium-sized enterprises and startups that mobilize alternative channels (Reuters, 2025). These dynamics overlay two structural facts: a global financing gap for micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises estimated at about 5.7 trillion US dollars, higher if the informal sector is included, and a venture capital market in 2024 to 2025 marked by a rebound in total amounts but a sectoral concentration, notably in artificial intelligence, alongside a decline in the number of deals, which heightens the relevance of non-bank channels for less courted sectors and territories (International Finance Corporation, 2024), and calls for a better understanding of how frugal ecosystems, capabilities, and support architectures condition access to such finance.

Our argument follows a simple line. First, frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems composed of shared assets, norms of frugality, and support infrastructures are not mere institutional backdrops. Evidence suggests they lower the marginal cost of experimentation and activate exploration capabilities at the level of organizations. Second, at the micro level, frugal innovation is less a one-off outcome than an organizational capability. Focus on essentials, cost discipline, and good enough robustness express routines of learning and reconfiguration. Third, access to alternative finance depends strongly on the readable signals sent by projects such as proof of use, prototyping, traction, and controlled costs, and on the quality of intermediation provided by incubators and hubs. Finally, entrepreneurial resilience, processual and multi-level, converts these resources and capabilities into financial and nonfinancial performance, acting both as a buffer against shocks and as a catalyst for learning.

However, despite a growing body of work on frugal innovation, entrepreneurial ecosystems, and alternative finance, three gaps remain. First, most studies conceptualize frugality at the level of products or individual firms rather than at the meso-level of entrepreneurial ecosystems, which limits our understanding of how shared infrastructures and norms of use shape experimentation under resource constraints. Second, research on alternative finance and entrepreneurial resilience rarely integrates frugal innovation as an organizational capability that generates credible quality signals for non-bank investors. Third, the roles of incubators and innovation hubs as support architectures for non-bank bankability are still fragmented across separate studies. As a result, we lack an integrative view of how frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems, frugal innovation, access to alternative finance, resilience, and performance are connected in emerging economies.

From this, the research question emerges: in emerging economies, how do frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems shape access to alternative finance, entrepreneurial resilience, and SME performance? In other words, what mechanisms link meso-level frugal ecosystems to micro-level frugal innovation capabilities? How does frugal innovation enhance access to alternative finance for SMEs and startups? In what ways does access to alternative finance contribute to entrepreneurial resilience and performance? How do incubators and innovation hubs strengthen or hinder these mechanisms?

Our objectives are fourfold. Clarify conceptually frugality at the ecosystem scale and frugal innovation as a capability, specifying measurement anchors. Map, in the 2018 to 2025 literature, the mechanisms of access to alternative finance that matter for small and medium sized enterprises and startups in emerging economies. Analyze the role of incubators and hubs as support architectures oriented toward nonbank bankability. Propose an integrative model linking mechanisms, capabilities, and families of indicators, resilience and performance, and derive managerial and public policy implications.

We adopt an exploratory design based on a systematic review consistent with PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA S, covering 2018 to 2025 and drawing on Scopus, Web of Science, and Cairn in French, English, and Spanish. The protocol was prespecified: structured queries, double screening of titles and abstracts, deduplication by identifiers, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for critical appraisal, and a pretested extraction grid distinguishing metadata, methodological characteristics, substantive dimensions including frugal ecosystem, frugal innovation, alternative finance, resilience, performance, and quality of support, theoretical frameworks, and families of indicators. Thematic analysis from the meso-level to the micro level informs a mechanism outcome framework and the development of testable hypotheses that align with the corpus.

We begin by laying the conceptual foundations through a structured literature review of the core constructs, then presenting the review methodology and data extraction protocol. The results are discussed along the causal chain of frugal ecosystems, frugal innovation, alternative finance, resilience, and performance, with the transversal role of incubators and hubs. We conclude by proposing an integrative conceptual model, drawing managerial and public policy implications, and outlining the main limitations and avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Frugal Ecosystems

2.1.1. Definitions and Conceptual Refinement

Frugality is no longer approached as a simple product attribute grounded in doing more with less. It is now conceived as a territorial organizing principle that connects shared resources, sober usage norms, and support infrastructures to make innovation affordable, robust, and contextual. Research published between 2018 and 2025 converge toward a triptych identifying frugal innovation based on essential functionalities, substantial cost reduction, and performance judged sufficient for intended uses, and then extend this reading to the meso-level of the ecosystem (Dima et al., 2022). From 2021 onward, research shifts the analytical focus from the firm to the multi-level entrepreneurial ecosystem, measuring frugal innovation as an organizational capability through validated scales and situating it in configurations where public policy, networks, infrastructures, and support actors co produce the conditions of frugality (Fuentes et al., 2024).

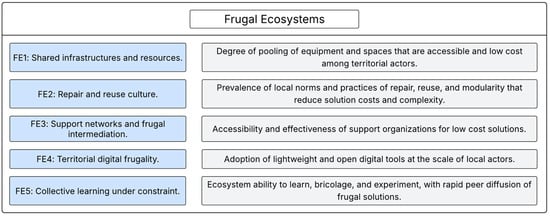

From this perspective, a frugal ecosystem can be defined as a territorial configuration of actors, assets, and rules that facilitates pooled access to design, manufacturing, and learning resources, institutionalizes norms of sobriety such as repair, reuse, and modularity, and orchestrates supports including hubs, incubators, public schemes, and lightweight digital tools in order to lower experimentation costs and diffuse solutions considered sufficient for local needs. This definition is consistent with four structural pillars (shared infrastructures and resources; repair and reuse culture; support networks and frugal intermediation; territorial digital frugality) and with a fifth, transversal latent dimension—collective learning under constraint, that reflects the ecosystem’s emergent learning-and-diffusion capacity. This definition aligns with research linking frugality and sustainability, with recent frameworks on entrepreneurial ecosystems, and with multi-level measurement toolkits (Prokopenko et al., 2025).

2.1.2. Components and Types of Frugal Ecosystems and Theoretical Anchors

This body of work conceptualizes frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems as meso-level configurations structured around four interdependent pillars. First, shared infrastructures and makerspaces reduce access costs to equipment, support learning by doing and operate as community innovation nodes that generate knowledge externalities and support circularity (Rahman & Best, 2024; Schroder et al., 2024). Second, cultures of repair and circularity, organized through local repair networks, extend product lifetimes, diffuse technical skills and consolidate sobriety norms at scale, thereby linking frugality to circular models (Parajuly et al., 2024). Third, organizational support structures and public policy instruments, hubs, incubators and programs, densify social capital, structure service provision and lower transaction costs for innovation under constraint (Wurth et al., 2023). Fourth, digital frugality and open data rest on lightweight, open-source or pay-per-use tools that extend SMEs’ exploratory capacity and enable low-cost innovation trajectories while diffusing “good enough” solutions across the ecosystem (Jie et al., 2025). Taken together, these pillars give frugality a systemic, territorial character and underpin the latent dimensions of frugal ecosystems used in our model. These four pillars jointly generate an emergent, transversal capability, collective learning under constraint, which captures peer diffusion, bricolage, and rapid experimentation dynamics across the ecosystem.

Empirical studies in emerging economies show how structural constraints, access to resources, family networks and local institutions shape frugality (Chaudhary et al., 2024). Theoretically, these configurations are anchored in resource-based and dynamic capabilities approaches that view frugality as a capability articulating sensing, seizing and reconfiguring, supported by learning, networks and data availability, with scales linking mechanisms to frugal innovation outcomes (Rossetto et al., 2023). The entrepreneurial bricolage lens complements this view by explaining the conversion of scarcity into opportunity through recombination and by clarifying boundaries between frugality, cost innovation and grassroots initiatives, which require locally grounded referential (Sarkar & Mateus, 2024). Recent frameworks on entrepreneurial ecosystems stress interdependence mechanisms and multi-level indicators needed to capture frugality as a systemic rather than firm-level property (Wurth et al., 2023). These theoretical anchors jointly support the idea that frugal ecosystems constitute a meso-level capability base from which frugal innovation can emerge and be sustained.

2.1.3. Expected Relationship with Frugal Innovation and Mechanisms for H1

The literature points to three mechanisms through which a frugal ecosystem increases frugal innovation. The first concerns the catalysis of dynamic capabilities by the ecosystem. Access to shared resources, mentors, and data accelerates sensing, facilitates low-cost seizing through rapid prototyping, and eases organizational reconfiguration, thereby being associated with higher rate and quality of frugal innovations, with established links between dynamic capabilities and process or product innovations (Jiraphanumes et al., 2023).

The second mechanism is bricolage and distributed experimentation. Makerspaces and local networks reduce trial and error costs, normalize modularity and repair, and diffuse routines of resource recombination that the literature identifies as antecedents of frugal innovation (Mateus & Sarkar, 2024). The third mechanism is the institutionalization of sobriety and circularity. Repair norms and an orientation toward circular trajectories calibrate expected functions, confer legitimacy on solutions considered sufficient, and facilitate their local financing, which aligns actor preferences with the frugal logic (Parajuly et al., 2024). Overall, meta syntheses and configurational studies report that ecosystem conditions combining resources, intermediation, and norms are associated with the emergence and diffusion of frugal innovation, especially in emerging economies (Fu et al., 2024). These mechanisms provide empirical support for H1, which posits that stronger frugal ecosystems are positively associated with higher levels of frugal innovation.

2.2. Frugal Innovation

2.2.1. Conceptual Clarification and Evolution of Definitions

Since 2018, the definition of frugal innovation has stabilized around a core that combines focus on essential functionalities, substantial cost reduction, and performance levels that are sufficient and robust. Scoping reviews confirm the extension of this logic beyond the product to processes and business models, with explicit linkages to sustainability and inclusion (Albert, 2022). Recent research clarified that frugality is not synonymous with degraded low cost. It corresponds to constrained, value-oriented optimization that targets accessibility and robustness in resource limited environments, while interfacing with artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and digital transformation (Escudero-Cipriani et al., 2024; Qin, 2024).

From 2022 onward, a conceptual shift has taken shape. Frugal innovation is increasingly approached as an organizational capability rather than only an outcome. This move is supported by a validated scale of frugal innovation capabilities that formalizes focus on essentials, cost reduction, and a shared commitment to sustainability, thereby embedding frugal innovation within the Resource-Based View and the Dynamic Capabilities View (Rossetto et al., 2023). Configurational studies highlight its antecedents, notably resource bricolage, external relational anchoring, market responsiveness, opportunity iteration, and cognitive flexibility, which is consistently associated with frugal innovation results from specific organizational and ecosystemic combinations (Fu et al., 2024).

2.2.2. Typologies and Operational Dimensions

The recent literature describes three complementary planes. At the level of action, frugal innovation concerns product, process, and business model, with modular design schemes, repairability, and pay per use service forms, including in marginalized contexts and in sectors such as industry, energy, and health (Mourtzis et al., 2019; Upadhyay & Punekar, 2023). At the level of measurement, the frugal innovation capabilities scale provides a robust operational basis with three dimensions, namely focus on essentials, cost discipline, and sustainability commitment, which enables firm level surveys and tests of convergent and discriminant validity (Rossetto et al., 2023). At the technological level, lightweight solutions in artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things reduce exploration and prototyping costs, facilitate usage monitoring, and strengthen the capacity of small and medium sized enterprises to design and iterate at low cost, which directly supports the implementation of frugal innovation (Qin, 2024).

Taken together, these results lead to a convergent interpretation. Frugal innovation is not a mere austere design. It expresses an organizational capacity to arbitrate among value, cost, and robustness, to institutionalize low cost and eco efficient exploration routines, and to build relevant partnerships with clients, nongovernmental organizations, and digital platforms (Dabić et al., 2022). These properties are consistent with the latent dimensions retained in this review for frugal innovation.

2.2.3. Link with Access to Alternative Finance and Mechanisms for H2

The relationship between frugal innovation and access to alternative finance rests first on the reduction in information asymmetry through the production of quality signals. Research on crowdfunding and alternative finance shows that technological credibility, feasibility evidence, prototyping, prior success, and intangible assets increase success rates and amounts raised (Bernardino & Santos, 2020). These factors structure analytical frameworks of crowd attraction and signal combinations associated with overfunding (Geiger & Moore, 2022; Sendra-Pons et al., 2024). By construction, frugal innovation generates readable cues for alternative financiers through functional simplicity, demonstrable robustness, and a disciplined value cost profile, which raises the probability of acceptance and reduces evaluation costs. This mechanism is consistent with H2, which posits that stronger frugal innovation capabilities improve access to alternative finance.

The second mechanism is alignment with the impact preferences of platforms and investors. Analyses of innovative campaigns indicate that the presence of environmental, social, and governance objectives, sobriety, and clarity of use can strengthen funder engagement, provided that complementary signals are coherent. This compatibility among frugal innovation, sustainability, and inclusion acts as a legitimacy signal in non-bank channels that increasingly internalize these criteria, notably in reward and equity crowdfunding and in peer-to-peer lending (Barone, 2025).

2.3. Access to Alternative Finance

2.3.1. Emergence and Recomposition of Alternative Finance

The expression alternative finance refers here to the set of non-bank channels and digital financing arrangements outside traditional bank credit. Since 2018, the joint rise in crowdfunding, peer-to-peer lending, digital supply chain finance, dematerialized microfinance, and embedded finance supported by open banking has widened access to capital for SMEs and startups (Marak & Pillai, 2018; Sharma et al., 2024). Scoping reviews confirm that the diffusion of fintech models is reshaping the small business financing ecosystem and diversifying the menu of available instruments beyond bank loans alone.

This recomposition rests on two dynamics. First, fintech platforms and lenders mobilize so called alternative data including transaction traces, payment flows, and nonfinancial signals to produce internal scores that speed up underwriting, lower collateral requirements, and open credit to historically underserved borrowers. Second, instruments tied to business-to-business transactions, in particular supply chain finance and its digital variants, align working capital needs with real cycles by transforming receivables and inventories into financeable assets. Empirical studies from 2024 to 2025 document easing of financial constraints, better synchronization between cash and operations, and strengthened supply chain resilience (He & Liu, 2025; P. Li et al., 2025).

2.3.2. Access Mechanisms and Effects on Entrepreneurial Resilience

Access cannot be reduced to the mere availability of channels or the volume of loans. Work in development economics and financial inclusion shows that fully digital journeys, payment interoperability, and the use of digital accounts and wallets lower entry frictions and transform the relationship of small businesses to formal financial services. Globally, the spread of digital payments and mobile channels is associated with measurable extensions of inclusion and with improved capacity of households and micro enterprises to absorb shocks, providing a robust interpretive frame for the gains observed on the firm side.

Causally, effective access to alternative finance operates through three complementary mechanisms. It reduces vulnerability in cash flows, diversifies funding sources, and shortens time to funds. Analyses on firm level data indicate that, other things equal, exposure to fintech options and to digital SCF schemes is associated with fewer financial constraints and with a higher probability of business continuity following adverse shocks, which supports the hypothesis of a buffering effect from alternative finance toward resilience (He & Liu, 2025; P. Li et al., 2025). This buffering role provides empirical support for H3, which links access to alternative finance with higher entrepreneurial resilience.

2.3.3. Signals, Governance, and the Structuring of Broadened Capital Access

The effectiveness of these channels also depends on the signals emitted by projects and their intermediaries. In crowdfunding, meta-analyses and expert surveys confirm the impact of observable quality signals including prior success, entrepreneurial experience, intangible assets such as patents, and offer clarity on success rates and amounts raised (Xu et al., 2025). This reading clarifies linkage with frugal innovation and with the quality of entrepreneurial support. Well-designed hubs and incubators manufacture these signals and ultimately improve access to alternative channels (Xu et al., 2025).

Finally, regulatory frameworks and public policies condition the scaling up of these markets while maximizing the inclusion resilience effect. Recent evaluations underline that complementarity between public support and fintech innovations mitigates SME constraints, provided that data quality, platform transparency, and incentive alignment are ensured (Abu et al., 2025; Sanga & Aziakpono, 2023). This perspective argues for a relational approach to access to alternative finance that articulates technical architecture, market governance, and support arrangements.

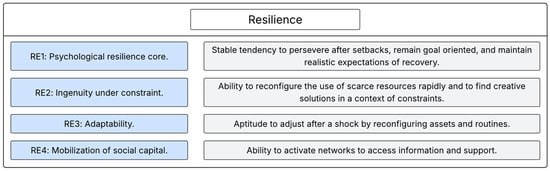

2.4. Resilience

2.4.1. Conceptual Evolution and Levels of Analysis in Entrepreneurial Resilience

In entrepreneurship, resilience is no longer conceived as a simple return to a prior state. It is approached as a process of regulation, adaptation, and transformation in the face of shocks, activated over time by mechanisms of anticipation, coping, and learning (Garrett & Zettel, 2021). This orientation is corroborated by a systematic review that clarifies the components of the construct and its operationalization in recent work (Hartmann et al., 2022).

The levels of analysis are now more clearly delineated. At the individual level, psychological resilience draws on positive resources such as hope, optimism, and self-efficacy, often grouped under psychological capital, and it is grounded in Conservation of Resources theory, which emphasizes protection and accumulation under constraint (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021). At the organizational level, resilience appears as a developable property of SMEs, supported by routines of anticipation, reconfiguration, and learning. Studies in crisis contexts and scoping reviews corroborate this capability based character, with a key role for internal and interorganizational arrangements (Ozanne et al., 2022).

Articulation with the Dynamic Capabilities View has become more firmly established. Sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring strengthen resilience, and resilience converts these capabilities into observable outcomes in uncertain environments (Dejardin et al., 2023). Empirical tests reveal partial or full mediations by resilience in the relationship between dynamic capabilities and performance, which aligns with its function as a transformation mechanism rather than a mere state (Biswakarma & Bohora, 2025).

2.4.2. Effects on Performance and Conditions for Effectiveness

The positive link between resilience and performance is now well supported. Higher levels of entrepreneurial resilience increase the probability of survival aftershocks, support innovation, and foster continuity of operations (Isichei et al., 2024). Other studies show a moderating role in the relationship between innovation and performance, indicating that resilience operates both as a final resource and as an orchestration capability (Ozanne et al., 2022; Pilav-Velic et al., 2024).

In our context, the use of transactional data and internal fintech scores reduces collateral requirements, accelerates disbursements, and enables countercyclical credit allocation to fragile areas. Large scale analyses associate the adoption of financial technologies with higher odds of SME survival in adverse contexts, which suggests both a liquidity effect and diversification of funding sources (Divya et al., 2025; Zhou & Sun, 2024). These effects are reinforced by digitized SCF, which aligns working capital financing with real flows and cushions supply disruptions, with gains in operational resilience evidenced in recent studies (Bani Atta, 2025).

Downstream, the relationship between resilience and performance operates through three complementary levers. Absorbing shocks in demand, prices, and lead times preserves cash flow and service quality, which are immediate determinants of outcomes. Post shock learning and business model reconfiguration support rapid adjustment, as illustrated by longitudinal studies using the dynamic capabilities perspective. Innovative behaviors and workplace well-being, encouraged by resilient forms of leadership, contribute to productivity and substantiate hypothesis whereby resilience exerts a positive effect on performance (Long et al., 2025; Prayag et al., 2024). Taken together, these mechanisms are consistent with H4, which posits that higher levels of entrepreneurial resilience are positively associated with SME performance.

Conditions for effectiveness finally include relational and territorial resources. Social capital mobilized from peers, suppliers, and entrepreneurial communities activates dynamic capabilities and facilitates access to information. This relational dimension justifies the integration of contextual variables in empirical tests (Ozanne et al., 2022).

Resilience stabilizes as a processual, multi-level construct embedded in resource based and dynamic capabilities theories. It clarifies its effects on performance and its interconnections with access to alternative finance, which legitimizes its central role in the studied causal chain. This conceptual and empirical consolidation provides a basis to operationalize resilience as a mediating capability and as a lever that converts financial and organizational resources into durable outcomes.

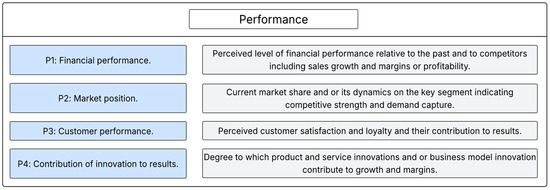

2.5. Performance

2.5.1. Conceptual Frameworks and the Multidimensionality of Performance

In entrepreneurship and SME management research, performance is now approached as a multidimensional and contextualized construct that goes beyond a purely financial focus. Recent work shows that relevant assessment aggregates financial dimensions such as profitability and growth, market dimensions such as share and customer access, as well as indicators of liquidity, operational efficiency, and innovation, to which are added extra-financial objectives related to sustainability and ESG effects (S. Kumar et al., 2024). This consolidation builds on integrative models, notably the Sustainability BSC and its sustainability-oriented variants, and on empirical syntheses that structure performance into correlated families rather than isolated indicators. A frequent scheme combines profitability, liquidity, growth, and competitive performance (Prayag et al., 2024). These frameworks have been reinterpreted for SMEs and for the twin digital and ecological transition, which has fostered the emergence of performance measurement systems that integrate ESG factors alongside traditional outcomes (Hillmann & Guenther, 2021).

The heterogeneity of SME contexts has revived the debate between subjective measures grounded in the perception of the owner manager and objective measures drawn from financial statements. Reviews in accounting and management recommend construct coherence rather than an a priori preference. Subjective measurement is valid when formulated relatively to competitors and when supported by reliable psychometric scales, which explains its substantial correlations with objective metrics when both are observable (Alves & Lourenço, 2023). Conversely, strictly objective measures are sometimes incomplete in unlisted or low transparency SMEs, which justifies the combined use of financial and nonfinancial indicators, as well as subjective scales when accounting data are missing. These methodological choices should be accompanied by validity procedures, notably confirmatory factor analyses and tests of invariance (Otoo, 2024).

Integration of sustainability has accelerated under the effect of regulation and stakeholder expectations. Syntheses show that next generation measurement systems incorporate ESG indicators explicitly linked to strategic objectives, with tangible effects on indicator design, dashboards, and managerial trade-offs, including in SMEs (S. Kumar et al., 2024). The literature identifies material ESG factors that need to be articulated with overall performance, while revisions of the Sustainability BSC converge toward configurations of the Sustainability BSC type. This reconfiguration is both conceptual and empirical and changes how the links between performance and organizational antecedents are analyzed (Dauerer, 2025). This multidimensional view is consistent with our operationalization of SME performance through several complementary latent dimensions.

2.5.2. Dynamic and Financial Drivers, the Role of Resilience, and Implications for Operationalization

The theoretical grounding in the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities has strengthened. Performance no longer appears as an independent terminal outcome, but as the translation, in uncertain environments, of the capacity to sense, seize, and reconfigure opportunities and resources. Tests conducted during and after recent shocks confirm that these capabilities predict SME performance through organizational mechanisms that regulate uncertainty (Clampit et al., 2022).

This framework clarifies the link with resilience and support that the organizational resilience converts resources and capabilities into observable outcomes by securing continuity of operations, absorbing shocks, and enabling post crisis learning. Several studies confirm partial or full mediations by resilience between dynamic capabilities and performance, which means that without resilient arrangements capabilities do not fully translate into results (Biswakarma & Bohora, 2025).

The financial chains that support this conversion have also been documented and inform the downstream reading of performance in our model. Alternative finance arrangements, particularly SCF and fintech channels, mitigate liquidity constraints and reduce the cash conversion cycle, which improves the resistance capacity of SMEs and ultimately their operational and commercial results (Al-Nimer et al., 2021). Causal analyses based on bank and market data show that SCF programs ease constraints, accelerate collections, and are accompanied by increases in sales, employment, and investment among suppliers. In the short term, the effect on margins may remain neutral, which is consistent with a performance profile oriented towards growth and survival before efficiency (Hu, 2025).

Overall, the recent period establishes performance as a multidimensional construct measurable through combinations of objective and subjective indicators, generated by dynamic mechanisms that couple capabilities, resilience, and financial supports rather than by static factors. For operationalization in our study, it is pertinent for SMEs to retain competitor relative measures such as sales growth, profitability, and market share, combined with nonfinancial indicators of customer orientation and innovation. This configuration takes into account the mediating role of resilience in converting resources and financial access into durable outcomes (Alves & Lourenço, 2023). These insights substantiate the hypothesis that resilience acts as a key mechanism through which resources and alternative finance are translated into improved performance.

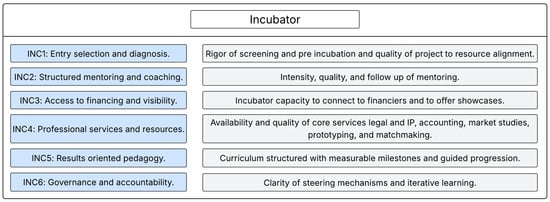

2.6. Quality of Entrepreneurial Support

The quality of entrepreneurial support is emerging as a higher order construct that articulates two complementary sets. On one side, the incubator is a programmatic arrangement focused on selection, diagnosis, sequenced accompaniment, and financing readiness. On the other, the innovation hub operates as a relational and cognitive node that orchestrates knowledge flows and interactions within the ecosystem (Sohail et al., 2023). This evolution shifts attention from a material view of infrastructures to a procedural and mechanistic reading, in which intermediation, capability building, and legitimation transform projects into credible candidates for financing. Reviews of incubation show that the CIMO approach, namely context, intervention, mechanism, and outcome, clarifies the heterogeneity of effects across intervention configurations (Caloffi et al., 2023). In parallel, work on innovation intermediaries reframes hubs as knowledge brokers and catalysts of sharing, including tacit knowledge, which stabilizes support quality as an operational architecture rather than a mere inventory of services (Feser, 2023).

2.6.1. Incubator

Conceptual Evolution of the Incubator

On the incubator side, the literature emphasizes the orchestration of intervention blocks that include selection and diagnosis, individualized mentoring, technical and market expertise, progression milestones, and investment preparation, as well as their causal effects. Quasi experimental evidence from acceleration programs shows that entrepreneurial schooling and intensive mentoring, combined with core services, significantly improve startup performance, confirming the role of managerial capital inculcated through structured accompaniment (Gonzalez-Uribe & Leatherbee, 2018). More recent results indicate that mentoring quality constitutes the active core of high performing arrangements, which explains observed impact differentials across programs and consolidates a processual reading of incubation design (Rechter & Avnimelech, 2025).

Since 2018, the definition of the incubator has shifted from a conception centered on hosting and access to physical resources to a procedural conception in which the incubator orchestrates accompaniment processes that include selection, diagnosis, interventions, and follow up, with verifiable outcomes on projects. A co citation analysis published in the Journal of Technology Transfer isolates business incubation, university incubators, social capital, evaluation, and survival or failure as the cores of a stabilized field, and emphasizes that the incubator should be understood as a node that produces knowledge, connections, and legitimacy rather than as a simple catalogue of services (Hausberg & Korreck, 2020).

Formalization Through the CIMO Framework and Updated Typologies

This rereading has been consolidated by work mobilizing the CIMO logic, that is context, intervention, mechanism, and outcome, in order to finely model the incubation process. Syntheses published between 2023 and 2025 propose prescriptive frameworks that articulate the context, the bundle of interventions such as coaching, expertise, networking, and compliance, the mechanisms activated including capabilities, social capital, and quality signals, as well as expected results such as graduation, financing, and performance. They provide a common language and comparable evaluation anchors, which embeds the incubator in an evidence informed organizational design perspective and explains the diversity of trajectories according to the combinations of interventions retained (Sohail et al., 2023).

The updated typology more clearly distinguishes forms including university, public, private, thematic, and social, as well as the phases of pre incubation, incubation, and post incubation or acceleration. Recent comparative studies highlight the sustainability orientation of some programs with arrangements dedicated to responsible innovation and impact, and document variability in operating models according to mission. This granularity helps explain why, given equivalent resources, programs produce differentiated effects on project maturation and on their visibility to external financiers (Rosado-Cubero et al., 2024).

Empirical Effects and Mechanisms Toward Access to Alternative Finance

Regarding effects, the empirical evidence available for 2018–2025 indicates that incubation increases the probability of measurable economic outcomes, with heterogeneity linked to design. Quasi experimental and longitudinal studies associate structured accompaniment, whether in the form of full incubation or intensive mentoring, with gains in revenue and employment and with higher short term survival rates, which foregrounds the role of managerial capital transmitted through structured support (Assenova, 2020). Other analyses distinguish the relative effects of support formats and suggest that content oriented and intensive coaching is correlated with greater private and federal public financing than lighter incubation formats, which strengthens the view of the incubator as a capabilities platform rather than a simple space provider (Clayton, 2024).

The link with access to alternative finance rests on three complementary mechanisms. The first is a signaling mechanism in which affiliation with a recognized incubator plays a certification role with investors and increases the probability of financing, notably venture capital. Recent work shows that collaborations with state accredited incubators reinforce this probability, which illustrates a legitimation channel (Du et al., 2025). The second is an intermediation mechanism in which incubators structure connections with business angels, funds, crowdfunding platforms, and fintech lenders, and prepare projects for the capital market by working on the pitch, due diligence, and compliance, which reduces information asymmetry (Svetek, 2022). The third is a capability building mechanism in which coaching and expertise generate verifiable evidence such as prototypes, usage traction indicators, and intangible assets, recognized as determinants of success in the literature on crowdfunding and early-stage equity (Manconi et al., 2022).

Studies published since 2024 provide direct evidence of this link between financing and incubation. Analyses on large samples and cohort follow ups show that participation in recognized programs increases the probability of raising private and public funds, and that these effects are partly mediated by network creation and by the production of evidence valued by platforms and alternative financiers. These results align with reviews on financial digitization that highlight a reduction in evaluation costs and increased use of alternative data that favor the inclusion of projects prepared by incubators (Bollaert et al., 2021; Panakaje et al., 2024).

Evaluation of incubators has intensified. Recent work recommends aligning impact indicators with the CIMO chain in order to identify which bundles of interventions produce which results in which contexts. For our study, support quality should be operationalized as a construct measured by observable dimensions that include selection and diagnosis, coaching and mentoring, specialist services, financing bridges, and milestone based governance, then empirically tested for their effect on access to alternative finance. This framing connects program design to observed financial outcomes and makes it possible to discuss the conditions under which incubation transforms frugal projects into credible candidates for non-bank channels while avoiding hasty generalizations (Sohail et al., 2023). This operationalization is directly consistent with our hypothesis that higher-quality entrepreneurial support improves access to alternative finance.

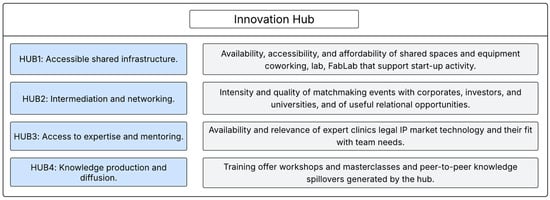

2.6.2. Innovation Hub

Mechanistic Redefinition and Intermediary Role

The recent literature defines the innovation hub as a meso-level intermediary that orchestrates knowledge flows, densifies networks and coordinates support arrangements. It brings together physical spaces and digital platforms where institutions, ideas and actors converge to enable open collaboration and the exploitation of knowledge beyond organizational boundaries, which differentiates it from a mere hosting or coworking logic (Chou et al., 2024; Schnell & Berger, 2025).

Existing studies identify three main forms: community hubs, corporate hubs and territorial hubs, governed, respectively, by communities, large firms or public–academic coalitions. They are analyzed as innovation intermediaries responsible for cognitive brokerage, alignment of stakeholder expectations, reduction in partner search costs and orchestration of communities. Research on intermediaries and on start-up–large firm collaboration units confirms this role of knowledge broker, inter-organizational mediation and circulation of tacit knowledge, which distinguishes hubs from the sequenced and programmatic logic of incubation (Caloffi et al., 2023; Feser, 2023).

Coworking spaces are described as micro-ecosystems regulated by routines of sharing, mutual aid and coopetition that support the emergence of skills and the attraction of talent. Within this configuration, hubs function as talent magnets that transform spatial aggregation into mobilizable social capital and structure entrepreneurial communities (Orel et al., 2022; Wei et al., 2025). From a governance perspective, they interlock with living labs, university platforms and transfer centers, relying on use-based experimentation and co-creation. Scholarship in innovation management shows that these arrangements articulate physical and digital resources and sustain the mobilization of knowledge, including in emerging economies where international organizations support local hubs that connect entrepreneurs, financiers and markets, with observable effects on upskilling and integration into innovation chains (Haukipuro et al., 2024).

Mechanisms and Operationalization of Support Quality in Access to Alternative Finance

Building on recent work, hypothesis H6 specifies a causal relationship between the quality of entrepreneurial support and access to alternative finance through three intertwined mechanisms carried jointly by incubators and innovation hubs. First, an information-brokerage mechanism: by filtering, formatting and referring relevant information on problems and solutions, proof of use, market fit and governance readiness, hubs and incubators reduce search costs and information asymmetries between project holders and financiers, whether crowdfunding platforms, fintech lenders, corporate investors or supply-chain finance providers.

This intermediation improves matching quality and accelerates agreements such as proofs of concept, purchasing contracts and corporate venture deals, which open gateways to alternative or adjacent financial channels (Corvello et al., 2023). Second, a capability-building mechanism: support organizations structure routines of collective learning, communities of practice and technology showcases, strengthen entrepreneurial pedagogy and generate verifiable evidence that make projects legible and bankable for nonbank financiers, consistent with meta-analyses on crowdfunding success and investment decisions. Third, a mechanism of territorial legitimation: affiliation with recognized hubs and incubators and their integration into regional innovation networks contribute to organizational thickness, entrepreneurial culture and reputation effects that act as certification signals and improve financing prospects for young firms, while hubs operate as relational infrastructures that connect entrepreneurs, funders and markets and steer access to nonbank instruments (Frimanslund & Nath, 2024).

Methodologically, these mechanisms justify modeling support quality as a second-order construct with two dimensions: incubation quality, which reflects CIMO-inspired design through selective entry, diagnostic depth, intensive mentoring, milestone-based monitoring and financing readiness, and hub quality, which captures intermediation and brokerage roles, collective capability building and territorial anchoring through events, communities and network integration (Rechter & Avnimelech, 2025; Sohail et al., 2023). Taken together, this architecture of mechanisms produces credible signals, pertinent connections and demonstrable capabilities that are priority targets for alternative financiers, thereby accelerating access to funds and, within our model, setting the conditions for downstream effects on organizational resilience and SME performance; support quality thus appears not as an auxiliary attribute but as a central causal lever of entrepreneurial financial inclusion in emerging economies (Feser, 2023; Sohail et al., 2023). This reading directly underpins H6, which posits that higher-quality entrepreneurial support improves access to alternative finance.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design and Scope

This study adopts a systematic review structured in accordance with the reporting standards set out in PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA-S and guided by the recommendations of Snyder (2019) and Tranfield et al. (2003). Following Page et al. (2021) for PRISMA 2020 and Rethlefsen et al. (2021) for PRISMA-S, we opted for a protocoled review because the evidence on frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems, alternative finance, resilience and performance in emerging economies is fragmented across disciplines, methodologies and geographical settings, and thus requires a transparent and reproducible synthesis rather than a narrative overview.

The research question was formulated using the Population Concept Context (PCC) model developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Peters et al., 2020) in order to operationalize how frugal ecosystems and entrepreneurial support structures shape access to alternative finance, resilience and performance in emerging economies. The population encompasses SMEs, startups, entrepreneurs, and entrepreneurial ecosystems operating in emerging economies, with international comparisons included when data pertaining to emerging economies are clearly identifiable. The conceptual scope covers six core constructs and their interrelations. These are frugal ecosystems, frugal innovation, access to alternative finance, resilience, performance, and the quality of entrepreneurial support through incubators and hubs considered as a lever for access to alternative finance. This configuration-oriented perspective is consistent with Snyder (2019) and Tranfield et al. (2003) directives, which emphasize the need to connect heterogeneous empirical findings to higher-level conceptual models.

3.2. Search and Screening

The contextual frame spans 2018 to 2025, a period marked by the progressive consolidation of frugality concepts and the rise in alternative finance channels. Publications in French, English, and Spanish were included to limit language bias and to broaden the scope of synthesis. The documentary sources comprise Scopus, Web of Science, and Cairn, selected for their multidisciplinary coverage and the reliability of their bibliometric metadata. The time window extends from 1 January 2018 to 1 July 2025. Searches were executed on 7 July 2025 in Scopus, 13 July 2025 in Web of Science, and 18 July 2025 in Cairn. The last search update was 20 July 2025. Only peer-reviewed journal articles were retained in line with the methodological guidance of Booth et al. (2016). In line with PRISMA-S, we additionally report the exact search execution dates and the full reproducible search strings for each database in Table 1.

Table 1.

Database queries for Scopus, Web of Science, and Cairn.

In keeping with the PCC framework, the search strategy focused on three thematic blocks and was systematically intersected with population related terms referring to SMEs, startups and entrepreneurs. The first block covered frugal ecosystems and frugal innovation. The second concerned alternative finance instruments. The third addressed entrepreneurial and organizational resilience and performance. Entrepreneurial support structures were captured transversally by embedding these terms in the population filter across the three query families.

Across databases, the three thematic blocks were operationalized through standardized Boolean query families adapted to each platform’s syntax while preserving the same conceptual logic. Table 1 reports the database-ready search strings together with the applied filters. The searched fields were defined as follows: Scopus (TITLE-ABS-KEY), Web of Science (TS, topic field), and Cairn (platform search over metadata and full text when available).

In Scopus and WoS, the three thematic query families were run separately to avoid excessively complex strings and were then merged prior to deduplication; and in Cairn, filters were applied via the platform facets after running the query. Emerging and developing economies were not restricted ex ante by country filters but were treated as a contextual inclusion criterion at the screening stage in order to avoid omitting multi-country or comparative studies where the data for emerging economies can be isolated.

For transparency and replicability, Table 1 reports the exact fields queried in each database, the applied filters.

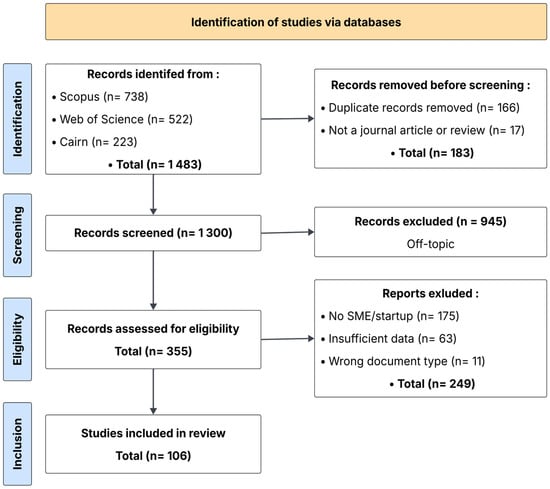

Eligibility criteria were defined operationally to ensure a coherent and pertinent selection of studies. To be included, an article had to meet four conditions. It reported empirical findings, whether qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods, based on primary or secondary data. It focused on SMEs, startups, entrepreneurs or entrepreneurial ecosystems, and did not examine large firms or purely corporate settings. It was situated in emerging or developing economies or provided disaggregated evidence on these contexts. It addressed at least one of the six core constructs (frugal ecosystems, frugal innovation, alternative finance, resilience, performance, incubators or hubs) with an explicit link to entrepreneurial outcomes. We excluded purely conceptual papers and editorials. We also excluded book chapters, theses, conference abstracts, and studies whose empirical context could not be clearly attributed to emerging economies or to entrepreneurial actors. References were centralized in Mendeley, with automated deduplication (DOI, title, author, and year) complemented by meticulous manual verification as recommended by Briner and Denyer (2012). This process enabled precise documentation of the volumes screened and retained, as illustrated in the figure below (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process.

Study selection followed a step-by-step workflow aligned with PRISMA 2020 from identification through database searches to standardized extraction followed by synthesis. Screening proceeded in two stages. First, two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, classifying records as “include”, “exclude” or “uncertain”. Disagreements and “uncertain” cases were resolved through discussion, and, where necessary, by consulting the full text. Before formal screening, the two reviewers conducted a calibration exercise on a pilot subset of records to harmonize the interpretation of eligibility criteria and reduce decision drift.

Second, the same reviewers independently assessed the full texts of potentially eligible articles. At this stage, papers were excluded when they did not concern SMEs/startups or entrepreneurial ecosystems, when the empirical context did not involve emerging or developing economies, when the constructs of interest were only tangentially addressed, or when key methodological information was missing. The numbers at each step of this process, from the 1483 initial references identified to the final corpus of 106 studies, are reported in Figure 1.

3.3. Quality Appraisal, Extraction, and Synthesis

Each included study was appraised independently by the two reviewers using the MMAT criteria corresponding to its design. MMAT scores served to document methodological strengths and weaknesses of the corpus; no automatic exclusion was applied on the basis of MMAT alone, but findings from lower-quality studies were interpreted with greater caution in the synthesis (Booth et al., 2016; Hong et al., 2018). Two reviewers independently assessed the retained studies, and disagreements were resolved by consensus, consistent with the recommendations of Boell and Cecez-Kecmanovic (2015). MMAT appraisal was recorded criterion-by-criterion and used to qualify confidence in evidence patterns rather than to mechanically filter studies.

The data extraction structure was specified ex ante using a pretested extraction sheet inspired by Kitchenham et al. (2010) to ensure uniformity and comparability of extracted information. It comprises five analytical blocks: metadata, methodological characteristics, substantive dimensions, mobilized theoretical frameworks, and contributions mapped to resilience pillars and to performance and sustainability dimensions. The extraction sheet was pilot-tested and refined prior to full extraction, and extracted entries were cross-checked to ensure consistency across reviewers. In addition to bibliographic metadata, extraction covered study design and sample, country/context classification, focal construct(s) and operationalization, key results, and mechanism statements linking frugality, alternative finance, resilience, and performance.

On this basis, we conducted a narrative, configuration-oriented synthesis in which studies were grouped according to the dominant construct they informed (frugal innovation, frugal ecosystems, alternative finance, resilience, performance, incubators/hubs) and then examined comparatively to identify recurring mechanisms linking frugality, access to alternative finance, resilience and performance, as well as the enabling roles of incubators and innovation hubs within frugal entrepreneurial ecosystems. Table 2 catalogs the primary articles retained for the review and, for each, reports the construct to which it is mapped, based on the main outcome or focal construct of the study. Given the heterogeneity of designs and outcomes, the synthesis was structured following SWiM-oriented principles by grouping studies into comparable mechanism blocks, summarizing results by convergence or divergence of evidence, and explicitly distinguishing supportive versus mixed or contradictory patterns before deriving the integrative propositions reported in Section 4. Given the heterogeneity of designs and outcomes, hypotheses H1–H6 are not statistically tested; rather, we assess whether the synthesized evidence is consistent with each hypothesized relationship and derive propositions for future empirical testing.

Table 2.

Selected primary articles for review.

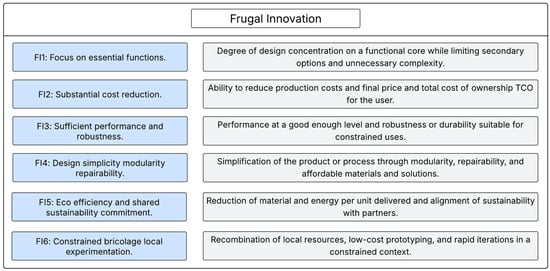

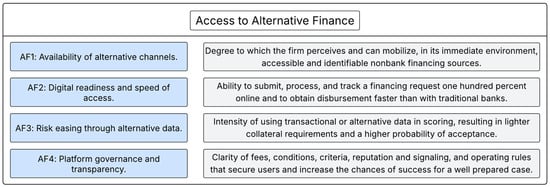

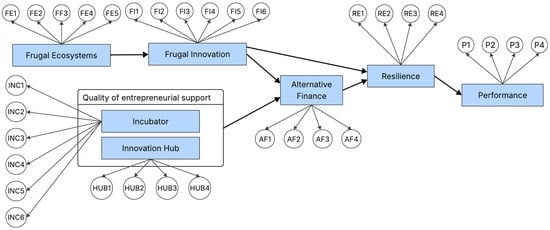

Building on this coding and mapping work, we derived a set of latent dimensions and operational definitions for each core variable, which are summarized in the figures below.

4. Results

The conceptual model distinguishes six main constructs. To enhance transparency and facilitate interpretation, each construct is operationalized through a set of latent dimensions derived from the synthesis. The sixth construct, quality of entrepreneurial support, is captured through two complementary components (incubators and innovation hubs) each specified by its own dimensions. Taken together, these figures provide the operational lens used to organize the causal mechanisms reported below.

Building on this structure, the results of the synthesis show the following causal mechanisms. We present the results and their discussion by moving from the meso-level to the micro-level, and then by examining how resources are converted into observable performance.

4.1. From Frugal Ecosystems to Frugal Innovation (H1)

Frugal territorial configurations first constitute a low-cost exploration infrastructure where the pooling of assets, norms of repair, and modularity render legitimate a design judged good enough for local uses (Figure 2). This environment is not a mere institutional backdrop, since it lowers the marginal costs of experimentation, stabilizes iteration routines, and translates systemic territorial properties into design capabilities within organizations. In addition, collective learning under constraint accelerates peer-to-peer diffusion of frugal solutions and reinforces shared experimentation routines, strengthening the capability-building pathway toward frugal innovation. The frugal ecosystem therefore appears as a direct determinant of the emergence and consolidation of frugal innovation (Figure 3), which is consistent with hypothesis (H1), suggesting that stronger frugal ecosystems are associated with higher levels of frugal innovation.

Figure 2.

Operational dimensions of frugal ecosystems.

Figure 3.

Operational dimensions of frugal innovation.

Having established how frugal ecosystems translate into frugal innovation capabilities, we next examine how these capabilities shape access to alternative finance.

4.2. From Frugal Innovation to Access to Alternative Finance (H2)

At the micro level, frugal innovation is expressed through a value proposition centered on essentials, a substantial reduction in costs, and robustness proven in real use (Figure 3). This triad generates clear signals of quality and feasibility that are easily readable by actors in alternative finance (Figure 4). In non-bank channels these signals reduce information asymmetry, speed up case processing, and broaden the investor base, all the more so when the design demonstrates functional simplicity, control of total cost of ownership, and proof of use. In this logic, frugal innovation functions as a vector of eligibility and credibility, which is consistent with hypothesis (H2), suggesting that stronger frugal innovation capabilities are associated with improved access to alternative finance.

Figure 4.

Operational dimensions of access to alternative finance.

This credibility mechanism becomes consequential once it converts into improved access to alternative finance, which we then link to resilience outcomes.

4.3. From Alternative Finance to Entrepreneurial Resilience (H3)

Access to alternative channels is not only a source of substitute capital (Figure 4). It acts as a financial buffer that aligns liquidity with operating cycles, eases collateral requirements, and shortens time to funding. Through the diversification of flows and procedural flexibility, shock absorption capacity increases and facilitates rapid adjustments to the business model. Consequently, financial accessibility is converted into entrepreneurial resilience (Figure 5) through the reduction in cash flow vulnerability and the creation of managerial slack under uncertainty, which is consistent with hypothesis (H3), suggesting that improved access to alternative finance tends to be associated with stronger entrepreneurial resilience.

Figure 5.

Operational dimensions of entrepreneurial resilience.

We therefore move from financing flexibility to the set of resilience mechanisms it enables under constraints.

4.4. From Resilience to Performance (H4)

Resilience then occupies a nodal position in the causal chain because it secures the translation of capabilities into outcomes (Figure 5). It preserves service continuity during disruptions, accelerates process reconfiguration, and catalyzes post crisis learning. The gains materialize in improvements in financial and nonfinancial indicators (Figure 6), especially when organizations operate under strong constraints. Adaptation and learning thus appear as immediate drivers of performance and benefit from flexible financial resources originating in alternative finance, which is consistent with hypothesis (H4), suggesting that higher levels of entrepreneurial resilience are associated with better SME performance.

Figure 6.

Operational dimensions of perceived performance.

We then examine how these resilience mechanisms are converted into observable performance outcomes.

4.5. The Mediating Role of Frugal Innovation and Access to Finance (H5)

The link between frugal innovation and resilience operates through two complementary paths. On the one hand, routines of simplification, modularity, and continuous improvement that are intrinsic to frugal innovation directly increase organizational agility and the capacity to recombine resources. On the other hand, the rise in bankability induced by these same routines indirectly broadens access to alternative finance and again strengthens resilience. Overall, the synthesis suggests a plausible partial mediation pathway in which frugal innovation relates to resilience both directly and indirectly via access to alternative finance, which is consistent with hypothesis (H5) and should be tested in future empirical studies.

4.6. Quality of Entrepreneurial Support and Access to Alternative Finance (H6)

The quality of entrepreneurial support completes and amplifies this mechanism (Figure 7 and Figure 8). We finally show how incubators and innovation hubs strengthen signaling and case preparation, thereby improving access to alternative finance.

Figure 7.

Operational dimensions of incubator quality.

Figure 8.

Operational dimensions of innovation hub quality.

Incubators structure selection, diagnosis, mentoring, and milestone-based governance that produce tangible and credible evidence, while hubs densify networks, broker knowledge, and strengthen the territorial legitimacy of projects. Together these arrangements transform ideas into financeable cases, reduce search and verification costs for financiers, and direct more efficiently toward relevant non-bank channels. When the support architecture and the ecosystem are aligned, effects cumulate at both micro- and meso-levels, which is consistent with hypothesis H6, suggesting that higher-quality entrepreneurial support is associated with improved access to alternative finance.

4.7. Overall Architecture of the Causal Chain

To link the constructs to their theoretical foundations, Table 3 summarizes the main frameworks mobilized in the literature for each core variable.

Table 3.

Main theoretical frameworks associated with the core variables.

This theoretical grounding underpins the ordered causal sequence described below and clarifies the position of each construct in the conceptual model. Several conditions for effectiveness finally specify the perimeter of application. The maturation of measurement instruments at territorial and organizational levels remains necessary to enable robust comparisons across emerging contexts. Digital and informational infrastructures must support rapid and fine-grained risk assessment so that alternative finance preserves its countercyclical function. The coupling between internal capabilities and local norms produces the clearest effects when simplicity, repairability, and proof of use resonate with the rules, networks, and support structures of the territory. In this perspective, these mechanisms jointly consolidate hypotheses H1 to H6 within a meso and micro architecture oriented toward value creation in emerging contexts.

To clarify the underlying logic of the conceptual model, we adopt an ordered causal sequence that links, in turn, the frugal ecosystem, frugal innovation, access to alternative finance, entrepreneurial resilience, and SME performance. This choice is first based on a theoretical and temporal hierarchy. The properties of the frugal ecosystem are treated as relatively stable meso-level characteristics that frame exploration trajectories, while frugal innovation is understood as an organizational capability at the micro level, developed within this context. Access to alternative finance then results from the quality and bankability signals generated by these capabilities and can be seen as a flow of resources that is mainly external to the organization. Entrepreneurial resilience reflects, over a longer time horizon, how these resources and capabilities are mobilized to absorb shocks, reorganize, and learn, which is ultimately reflected in financial and nonfinancial performance indicators.

By combining the resource-based view, dynamic capabilities, signaling theory, and the literature on alternative finance, this linear structure appears to be the most parsimonious and coherent architecture with the current empirical evidence on SMEs in emerging economies. Other configurations are of course theoretically possible, such as feedback relationships between performance and access to finance, a moderating role of resilience or alternative finance in some relationships, or iterative loops between capabilities and context. However, we treat these as natural extensions of this basic framework and explicitly refer them to future research avenues and to the limitations of the study. This ordered sequence is reflected in the conceptual model presented in figure below (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Conceptual model.

5. Conclusions

This article sets out to provide, for the period 2018–2025, an integrated reading of entrepreneurial frugality in emerging economies by linking the meso- and micro-levels of action within a single explanatory chain. The systematic review conducted in line with PRISMA 2020 and PRISMA S using Scopus, Web of Science, and Cairn in French, English, and Spanish enabled the assembly of a robust corpus and a SWiM-based narrative synthesis centered on six hypothetical relations. In doing so, the review directly addresses three gaps highlighted at the outset. A key gap is the fragmented evidence base, which seldom connects territorial frugality to firm-level capability building. A second gap is the limited explanation of how alternative finance transforms innovation signals into resilience and performance outcomes. A third gap is the insufficient theorization of entrepreneurial support organizations as mechanisms, beyond their treatment as contextual background.

The synthesized evidence converges toward a coherent architecture consistent with the proposed causal sequence. Frugal ecosystems understood as configurations of actors, pooled assets, and sobriety norms are positively associated with frugal innovation conceived as an organizational capability. Frugal innovation, in turn, increases access to alternative finance by producing quality and feasibility signals that are readable by platforms and lenders. Financial access is associated with stronger entrepreneurial resilience by diversifying sources, reducing collateral requirements, and accelerating the mobilization of liquidity. Resilience then converts these resources and capabilities into performance, both financial and nonfinancial. The synthesis suggests a plausible partial mediation pathway from frugal innovation to resilience, both directly and via access to alternative finance. Finally, the quality of entrepreneurial support, operationalized through incubators and innovation hubs, strengthens signaling and case preparation, thereby improving access to alternative finance and stabilizing the overall chain.

The main theoretical contributions rest on four clarifications. First, frugality is repositioned at its level of effectiveness as a meso property of ecosystems that conditions low-cost exploration trajectories at the firm level, which helps closes the conceptual gap between context and capability and justifies (H1). Second, frugal innovation is treated not as a one-off result but as a measurable capability that articulates essentials, substantial cost reduction, and robustness in use. This shift helps explain its signaling power with respect to nonbank capital markets (H2) and its contribution to entrepreneurial resilience through direct and mediated paths (H5). Third, alternative finance is not viewed as an undifferentiated substitute for bank credit. Rather, it is conceptualized as a financial buffering device that, when aligned with operating cycles, supports resilience (H3). Fourth, entrepreneurial support is theorized as a two-pillar mechanism architecture, incubator sequencing at the project level and hub brokerage/densification at the ecosystem level, clarifying its contribution to non-bank access (H6).

For entrepreneurs, the findings translate into an actionable bankability script: demonstrate essential functionality, total cost of ownership control, and proof of robustness-in-use to increase eligibility in non-bank channels. For support organizations, professionalizing incubation around selection/diagnosis, intensive mentoring, milestone-based governance, and systematic connection to alternative-finance actors increases both the probability of access and the speed of decision. For ecosystem operators, strengthening pooled infrastructures, repair/modularity norms, and brokerage-oriented hubs reduces the marginal cost of experimentation and accelerates the maturation of financeable frugal projects.

Policymakers can strengthen the inclusion–resilience–performance effect by coordinating digital payment and onboarding infrastructure, open banking with responsible governance of alternative data, and pro-supply chain finance measures with certified incubators and innovation hubs that lower verification and search costs for financiers. In emerging contexts, such coordination helps preserve the countercyclical role of alternative finance and scale frugal innovation without excessive reliance on collateral-based banking.

Beyond these contributions, this review has limitations that qualify the scope of inference. First, measurement heterogeneity—especially for meso-level frugal ecosystems and access to alternative finance—reduced cross-study comparability and justified a SWiM narrative synthesis rather than quantitative aggregation. Second, SME performance was often captured through subjective or perceptual indicators, which may inflate common-method bias and limit precision. Third, institutional contexts varied substantially across countries, constraining the transferability of some mechanisms. Finally, despite multilingual coverage, some non-indexed and gray literature may remain under-represented; therefore, findings should be interpreted with caution.

These limits open precise avenues for research. Harmonize scales for example, by systematically deploying validated measures of frugal innovation capabilities and of support quality evaluation. Develop longitudinal and multi-level designs to isolate meso to micro effects. Better instrument access using delays, acceptance rates, and collateral structure. Strengthen causal identification through quasi experiments, tests of invariance, and multi-source triangulations.

In sum, this review offers a double contribution. It proposes an integrative model linking contextual frugality, innovation capabilities, financial access, resilience, and performance. It also provides a replicable methodological protocol for cumulating evidence in a still dispersed field. Incubators and hubs are posited as mechanism-based levers of the bankability and characterizing alternative finance as a resilience buffer. On this basis, the paper offers an actionable evaluation framework for researchers, leaders of support organizations and policymakers in emerging economies. This framework provides a solid basis for further empirical investigations. It also offers guidance for ecosystem policies oriented toward frugal, inclusive, and high-performance innovation trajectories (Supplementary Materials).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jrfm19010055/s1, Table S1. PRISMA checklists.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.; methodology, B.M. and A.A.; software, A.A.; validation, B.M. and A.A.; formal analysis, B.M.; investigation, B.M.; resources, B.M.; data curation, B.M. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.M.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; visualization, B.M.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, B.M.; funding acquisition, B.M. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AF | Alternative Finance |

| BA | Business Accelerator |

| BI | Business Incubator |

| BSC | Balanced Scorecard |

| EE | Entrepreneurial Ecosystem |

| ECSP | European Crowdfunding Service Providers |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESO | Entrepreneurial Support Organization(s) |

| FE | Frugal Ecosystems |

| FI | Frugal Innovation |

| INC | Incubator |

| IP | Intellectual Property |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| P | Performance |

| PCC | Population–Concept–Context |

| PRISMA 2020 | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| R&D | Research and development |

| RBV | Resource-Based View |

| RE | Resilience |

| SCF | Supply Chain Finance |

| SME(s) | Small and Medium-sized Enterprises |

| SWiM | Synthesis Without Meta-analysis |

| TCO | Total Cost of Ownership |

| UTAUT2 | Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 |

| US | United States |

| WoS | Web of Science |

References

- Abbassi, W., Harmel, A., Belkahla, W., & Ben Rejeb, H. (2022). Maker movement contribution to fighting COVID-19 pandemic: Insights from Tunisian FabLabs. R&D Management, 52(2), 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu, N., da Silva, F. P., & Vieira, P. R. (2025). Government support for SMEs in the Fintech Era: Enhancing access to finance, survival, and performance. Digital Business, 5(1), 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agag, G., Durrani, B. A., Shehawy, Y. M., Alharthi, M., Alamoudi, H., El-Halaby, S., Hassanein, A., & Abdelmoety, Z. H. (2023). Understanding the link between customer feedback metrics and firm performance. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 73, 103301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M. (2022). Assessing the sustainability impacts of frugal innovation—A literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 365, 132754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nimer, M., Abbadi, S. S., Al-Omush, A., & Ahmad, H. (2021). Risk management practices and firm performance with a mediating role of business model innovation. Observations from Jordan. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(3), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, K. S., Garcia-Monleon, F., & Mas Iglesias, J. M. (2024). Exploring the interaction between big data analytics, frugal innovation, and competitive agility: The mediating role of organizational learning. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 200, 123188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, I., & Lourenço, S. M. (2023). Subjective performance evaluation and managerial work outcomes. Accounting and Business Research, 53(2), 127–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzolin, G., & O’Sullivan, E. (2025). Innovation intermediaries in the digital transformation process. A comparative case study of research and technology organisations in the US and the UK. Technovation, 142, 103200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assenova, V. A. (2020). Early-stage venture incubation and mentoring promote learning, scaling, and profitability among disadvantaged entrepreneurs. Organization Science, 31(6), 1560–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani Atta, A. A. (2025). Financial technology platforms and enhancing SME financing in Jordan. Discover Sustainability, 6(1), 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S. (2025). Can sustainability disclosure affect crowdfunding success? Business Strategy and the Environment, 34(7), 7961–7979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardino, S., & Santos, J. F. (2020). Crowdfunding: An exploratory study on knowledge, benefits and barriers perceived by young potential entrepreneurs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(4), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A., Morgan, N. A., & Rego, L. L. (2022). Examining why and when market share drives firm profit. Journal of Marketing, 86(4), 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswakarma, G., & Bohora, B. (2025). Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: The mediating role of organizational resilience in IT sector. Future Business Journal, 11(1), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]