Abstract

This study presents a fairness-aware framework for modeling the Probability of Default (PD) in individual credit scoring, explicitly addressing the trade-off between predictive accuracy and fairness. As machine learning (ML) models become increasingly prevalent in financial decision-making, concerns around bias and transparency have grown, particularly when improvements in fairness are achieved at the expense of predictive performance. To mitigate these issues, we propose a model-agnostic, post-processing threshold optimization framework that adjusts classification cut-offs using a tunable parameter, enabling institutions to balance fairness and performance objectives. This approach does not require model retraining and supports a scalarized optimization of fairness–performance trade-offs. We conduct extensive experiments with logistic regression, random forests, and XGBoost, evaluating predictive accuracy using Balanced Accuracy alongside fairness metrics such as Statistical Parity Difference and Equal Opportunity Difference. Results demonstrate that the proposed framework can substantially improve fairness outcomes with minimal impact on predictive reliability. In addition, we analyze model-specific trade-off behaviors and introduce diagnostic tools, including quadrant-based and ratio-based analyses, to guide threshold selection under varying institutional priorities. Overall, the framework offers a scalable, interpretable, and regulation-aligned solution for deploying responsible credit risk models, contributing to the broader goal of ethical and equitable financial decision-making.

1. Introduction

The financial sector is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by technological advancements such as Data Science (Dhar, 2013; Donoho, 2017; Han et al., 2011) and ML (Bishop, 2006; Mitchell, 1997; Vapnik, 1995), alongside an increasing emphasis on risk management. These developments enable institutions to optimize decision-making processes, particularly in credit risk assessment, which is crucial for managing loan defaults and complying with regulatory frameworks.

PD modeling plays a central role in credit risk management by estimating the likelihood that a borrower will fail to meet their financial obligations. Accurate PD models help institutions minimize financial risk, allocate capital efficiently, and enhance transparency in decision-making.

While traditional approaches (Gietzen, 2017; Hanea et al., 2021; Izzi et al., 2012) and statistical methods (Cox, 2018) are interpretable and well-established, they often struggle to capture complex patterns in data, making them less suitable for dynamic and high-dimensional environments. In contrast, ML models offer greater flexibility and predictive power to address these challenges. However, their adoption raises critical concerns regarding fairness, transparency, and bias (Pagano et al., 2022; Rabonato & Berton, 2025).

Bias in ML models can arise from various sources (de Vargas et al., 2022; Hort et al., 2024; Jafarigol & Trafalis, 2023; Jiang & Nachum, 2020; Robinson et al., 2024; Y. Zhang et al., 2024). For example, underrepresented groups in training data may experience disproportionately high error rates, leading to discriminatory outcomes (Borza et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2022; Langbridge et al., 2024). Addressing such biases requires robust methodologies to evaluate fairness and mitigate inequities without compromising model performance. This is particularly important in financial applications, where fairness violations can have legal, ethical, and reputational consequences.

Thus, fairness is a critical requirement in PD modeling because PD estimates directly influence credit allocation decisions. Unfair or biased PD models may systematically disadvantage certain socio-demographic groups, reinforcing structural inequalities and exposing institutions to regulatory, legal, and reputational risks. ML models may unintentionally replicate past discrimination unless fairness is explicitly measured and monitored. Therefore, incorporating fairness metrics into PD modeling is essential to ensuring equitable access to credit and compliance with modern regulatory frameworks.

In this context, we propose a fairness-aware framework for modeling the PD of individual borrowers by explicitly addressing the trade-off between predictive accuracy and fairness. While traditional scoring systems have primarily emphasized predictive accuracy, growing evidence shows that these models may inadvertently introduce or amplify biases, systematically disadvantaging certain groups of applicants. These biases raise ethical and regulatory concerns and risk undermining public trust in financial institutions. As ML methods become more prevalent, the pursuit of higher predictive performance must be balanced against fairness considerations. To this end, we introduce a threshold optimization framework (see Section 5) that adjusts the decision boundary of classification models using a tunable parameter, offering a practical and interpretable mechanism for managing fairness–performance trade-offs without retraining the underlying model. This approach enables institutions to implement credit scoring systems that are not only effective but also socially responsible.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. After highlighting the key contributions, Section 3 introduces both traditional and ML techniques for PD modeling. Section 4 explores different types of biases and fairness notions in credit risk assessment, along with corresponding mitigation strategies. Section 5 presents an optimization framework for selecting an appropriate threshold for PD classification, balancing model performance and fairness. Section 6 describes the dataset and variable selection process. Experimental results, including model performance, bias analysis, and the decision boundary adjustment framework, are presented in Section 7. Legal and ethical considerations are discussed in Section 8. Section 9 outlines the limitations of this study and suggests directions for future research. Finally, Section 10 summarizes the main findings and discusses their practical implications.

2. Key Contributions

This study contributes a threshold optimization framework for credit risk modeling, with a specific emphasis on post-processing decision boundaries in probabilistic classifiers. The approach is particularly tailored to credit scoring applications, when predictive accuracy and fairness conflict and must be transparently managed. Our key contributions are as follows:

First, we examine the intrinsic tension between predictive accuracy and algorithmic fairness in PD modeling across several machine learning classifiers. Our analysis incorporates established fairness metrics (see Section 4.2), and reveals model-specific behaviors under fairness constraints. This sheds light on how post-processing interventions can meaningfully influence the fairness–performance balance in credit scoring scenarios. Hence, this work contributes to the development of responsible credit risk models by providing a transparent and auditable post-processing method to control group-level disparities, aligning fairness adjustments with major regulatory frameworks, enabling interpretable fairness–performance trade-offs consistent with supervisory expectations, and promoting more inclusive credit access by mitigating disparate impacts in PD estimation.

Second, we propose a post-processing threshold optimization strategy based on a scalarized objective function that jointly considers fairness and performance losses. A single, interpretable parameter (Equation (9)) governs this trade-off, enabling continuous control without modifying the underlying models or requiring retraining. This design supports transparent and flexible deployment in regulated financial environments.

Third, to better understand the effect of optimized thresholds (Equation (15)), we introduce a dual-reference comparison strategy relative to both the default threshold and the minimax-optimal threshold (Equation (13)). We further develop a diagnostic ratio-based visualization () (Equations (16)–(18)) in quadrant form to evaluate fairness–performance gains, providing intuitive support for threshold selection in operational settings.

Last, we conduct comprehensive experiments on both synthetic data and the German Credit dataset, applying the framework to multiple classifiers. We analyze the sensitivity of the optimized thresholds to different fairness–performance preferences, evaluate generalization to real data, and quantify trade-offs across settings. These results provide insights for institutions seeking to implement fairness-aware decision rules with minimal loss in predictive power.

3. Modeling the Probability of Default

The modeling of PD has been extensively studied, with techniques evolving from traditional approaches to more advanced ML methods. On the one hand, the traditional methods for estimating PD include both qualitative and quantitative approaches. For example, expert judgment-based techniques (Gietzen, 2017; Hanea et al., 2021; Izzi et al., 2012) rely mainly on the intuition and experience of credit officers to assess the likelihood of default. While flexible, these methods often suffer from subjectivity and inconsistency, making them less reliable in modern regulatory contexts. On the other hand, the advent of ML introduced a paradigm shift in credit risk modeling. For example, algorithms such as Logistic Regression (LR) (Cox, 2018), Random Forests (RF) (Breiman, 2001), or XGBoost (T. Chen & Guestrin, 2016) enable the modeling of complex, non-linear relationships and are well-suited for high-dimensional data, offering greater predictive accuracy and robustness.

Advancements in fairness-aware ML aim to mitigate bias in financial decision-making. Despite their predictive strength, ML models can unintentionally reinforce systemic discrimination, especially when trained on biased datasets. To address this issue, a range of fairness-aware techniques has been developed. Bias mitigation typically occurs across three stages:

Pre-processing refers to techniques applied to the data before training a ML model. The aim is to reduce or eliminate bias present in the dataset, which often stems from historical or societal inequalities. During this phase, one can normalize and balance the dataset to remove biases before training. Methods such as reweighting (Harris, 2020; Stevens et al., 2020; Y. Zhang & Ramesh, 2020), optimized pre-processing (Calmon et al., 2017), or modifying features to reduce disparate impact, or resampling (Puyol-Antón et al., 2021; Y. Zhang & Sang, 2020) could be suitable. The later includes generating synthetic data, to augment underrepresented class (oversampling) (Koziarski, 2021; Puyol-Antón et al., 2021; Rajabi & Garibay, 2021; Vairetti et al., 2024), or to reduce the number of samples from the majority class to balance it with the minority class (undersampling) (Koziarski, 2021; Sharma et al., 2020; Smith & Ricanek, 2020; Vairetti et al., 2024). These approaches at at this stage are model-agnostic, meaning they can be used regardless of the algorithm chosen, and they tackle bias at its root, within the data itself.

Subsequently, in-processing involves modifying the learning algorithm during the model training phase to incorporate fairness constraints or objectives. During the training stage, this can be performed by adding regularization terms that penalize unfair outcomes (Harris, 2020; Zheng et al., 2021) or using adversarial training to remove information about protected attributes (Abbasi-Sureshjani et al., 2020; B. H. Zhang et al., 2018). For example, methods such as Fairness Through Unawareness ensures that protected attributes are excluded during model training to avoid discriminatory predictions; however, this approach may be ineffective if proxies for sensitive attributes remain within the dataset (Dwork et al., 2012). Causal Inference-based methods provide a more nuanced solution by identifying and addressing indirect biases arising from latent relationships between variables (Kilbertus et al., 2017).

Finally, the post-processing techniques are applied after a model has been trained. These methods adjust the model’s predictions to ensure fairer outcomes without altering the model or the training data. Examples of this situation include the evaluation of the equalized odds or reject option classification (Alam, 2020; Harris, 2020; Stevens et al., 2020; Y. Zhang & Ramesh, 2020). The other approach includes adjusting the decision threshold, rather than relying on the standard threshold . For example, the advanced three-way decision frameworks for credit risk prediction addresses the limitations of traditional binary (default, or non-default) classification models (Li et al., 2024; Li & Sha, 2024; Pang et al., 2024). By introducing an additional uncertain or deferment category, these methods allow for deferred decisions, optimizing decision thresholds and improving decision accuracy by incorporating more information before classifying borrowers (Pang et al., 2024). Each approach optimizes decision thresholds, often using techniques like particle swarm optimization (Li & Sha, 2024) or support vector data descriptions (Li et al., 2024), and applies these methods to real-world datasets.

Recent studies have increasingly focused on fairness and performance trade-offs for financial applications, particularly in credit risk modeling. Among others, Das et al. (2021) provides a comprehensive overview of fairness metrics and legal considerations, highlighting threshold adjustment as a post-processing technique. Hardt et al. (2016) introduced the concept of equalized odds, proposing post-processing methods to adjust predictors for fairness. Building on this, Woodworth et al. (2017) analyzed the statistical and computational aspects of learning predictors that satisfy equalized odds, suggesting relaxations to address computational intractability. Diana et al. (2021) proposed a minimax group-fairness framework, aiming to minimize the maximum loss across groups, thereby directly addressing the worst-case group performance. Lahoti et al. (2020) tackled fairness without access to demographic data by introducing adversarially reweighted learning, optimizing for Rawlsian max–min fairness. In the realm of natural language processing, Resck et al. (2024) explored the trade-off between model performance and explanation plausibility, employing multi-objective optimization to balance these aspects. Similarly, Bui and Von Der Wense (2024) examined the interplay between performance, efficiency, and fairness in adapter modules for text classification, underscoring the complexity of achieving fairness alongside other objectives.

In contrast to all such prior works, our approach, as introduced in Section 5, presents a mathematically grounded, model-agnostic framework for optimizing decision thresholds through a weighted trade-off between fairness and performance. We introduce a formal objective function with a tunable parameter that allows institutions to navigate this trade-off, offering a practical tool for aligning predictive accuracy with regulatory and ethical fairness standards. By analyzing how the optimal threshold shifts across different weight values, our contribution complements previous works, and our method advances from conceptual fairness guidance to insights into implementation in credit risk modeling where balancing fairness and performance are important.

4. Biases and Fairness in PD Modeling

Bias can emerge in ML modeling even when the data used is considered entirely accurate and with many different sources. In this section we describe the types of bias often encountered in PD modeling.

4.1. Types of Biases and Fairness

Firstly, we comment on examples of biases expected in the modeling process. Exhaustive reviews on bias can be found in (Ferrara, 2023; Hort et al., 2024; Mehrabi et al., 2021; Mikołajczyk-Bareła & Grochowski, 2023).

- Representation Bias: It arises when the training dataset does not adequately represent all groups in the population (Borza et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2022; Langbridge et al., 2024). In credit default risk modeling, it can occur because historical loan datasets contain a disproportionately high number of non-defaulting applicants, which can negatively affect model performance (Y. Chen et al., 2024; Namvar et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2024; S. Zhang et al., 2024). Techniques such as resampling, balanced metrics or decision threshold adjustments can help reduce the impact of imbalanced data.

- Label Bias: This bias arises when the labels used for training a model reflect existing discriminatory practices, potentially perpetuating biases, an example of when past loan approvals were influenced by discriminatory practices. This issue can be addressed, for example, through re-labeling, debiasing algorithms to correct skewed labeling patterns (Diao et al., 2024; Guo et al., 2025; Xia et al., 2024), or re-weighting data points without altering labels (Jiang & Nachum, 2020). Other example of techniques include post-processing steps to adjust model outputs (Doherty et al., 2012; Feldman, 2015; Hardt et al., 2016).

- Algorithmic Bias: This type arises from the design of ML algorithms, often leading to disproportionate misclassifications of certain groups. This can occur due to overfitting to majority groups, where models trained on imbalanced datasets fail to generalize to minority groups. To mitigate these biases, bias-conscious algorithms can optimize fairness metrics (Langbridge et al., 2024), or hyperparameter tuning can help balance accuracy and fairness (Weerts et al., 2020; Yu & Zhu, 2020).

- Selection and Evaluation Bias: Selection bias arises when the training data are not representative of the target population, such as when credit models only analyze approved loans, ignoring rejected applicants. This can be mitigated by incorporating denied loan applications or using synthetic data generation. Evaluation bias, on the other hand, occurs when model performance metrics fail to consider fairness across different groups. To address this, fairness metrics like disparate impact ratio, equal opportunity, and group-specific precision and recall should be included alongside traditional evaluation metrics to ensure equitable performance.

Types of Fairness include:

- Demographic Parity: This ensures that the model’s predictions are independent of sensitive attributes, such as gender, race, or age (Dwork et al., 2012; Kusner et al., 2017). For example, the proportion of approved loans should be similar across all demographic groups. Among the possible mitigation strategies, one could modify the decision threshold or re-weight the training data to achieve parity in predictions or applying post-processing techniques to adjust outcomes to align with fairness criteria.

- Equal Opportunity: This criterion (Hardt et al., 2016) ensures that true positive rates are equal across all groups (default and non default). In credit risk, it means that applicants who are genuinely creditworthy have an equal chance of being approved, regardless of group membership. Using fairness constraints during model training to balance true positive rates or applying adversarial debiasing techniques (Grari et al., 2023; B. H. Zhang et al., 2018) could reduce disparities.

- Individual Fairness: This requires that individuals with similar characteristics receive similar predictions. In credit risk modeling, two applicants with comparable financial profiles should have similar default probabilities. Possible mitigation technics could include the implementation of distance-based fairness regularization (Gouk et al., 2021) during training to ensure similar inputs produce consistent outputs.

- Fairness Through Awareness: This approach explicitly incorporates sensitive attributes to correct biases, rather than ignoring them (Dwork et al., 2012). In this case, using sensitive attributes during pre-processing to reweigh or adjusting data distributions, ensuring fairer outcomes for historically disadvantaged groups could help.

It is worth commenting that the bias and fairness mitigation methods are not limited to the ones mentioned in this paper, and also that they can be applied alone or in combination with others to improve the performance.

4.2. Metrics for Evaluating Performance, Biases and Fairness

Mitigating bias and ensuring fairness in ML-based modeling of the PD requires a multifaceted approach, combining technical adjustments with ethical considerations. This requires us to evaluate both predictive performance and fairness to achieve equitable and reliable outcomes in credit risk assessment. In this work, we use several metrics to evaluate the biases and fairness discussed in Section 4.1.

Firstly, the performance of the models will be accessed via the Balanced Accuracy (BA) metric (Brodersen et al., 2010). BA is particularly useful for imbalanced classification problems. Unlike standard accuracy, which can misrepresent performance when one class dominates, and is calculated as the average of sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity represents the true positive rate, that is the percentage of positive cases the model is able to detect, and the specificity, the true negative rate, measures the proportion of correctly identified negatives over the total negative predictions made by the model. This metric ensures a fairer assessment across both majority and minority classes. By definition, , with a high BA indicating effective model performance across all classes, while a low BA highlighting difficulties in correctly identifying positive or negative cases, signaling potential issues such as high false positive or false negative rates. Thus, its ideal value is .

Secondly, concerning the biases, we focus on a set of metrics to assess fairness and bias in ML models. These metrics, denoted as m, along with their corresponding ideal values , are as follows:

- -

- Average Odds Difference (AOD) (Hardt et al., 2016) measures the difference between the sensitivity and specificity of privileged and non-privileged groups. It balances true and false positive rates to avoid unfair denials and risky loans. Thus, the ideal value is . Positive or negative values indicate biases favoring one group or the other.

- -

- Disparate Impact (DI) (Feldman et al., 2015) compares favorable outcome rates between protected groups. It detects indirect discrimination in credit scoring models. A value of indicates perfect fairness, while values below or above 1 suggest bias.

- -

- Statistical Parity Difference (SPD) (Corbett-Davies et al., 2017) assesses the difference in favorable outcomes between groups. It helps identify imbalances in loan approval rates across demographics. A score of indicates equal benefit, while positive or negative values highlight disparities.

- -

- Equal Opportunity Difference (EOD) (Hardt et al., 2016; Pleiss et al., 2017) examines sensitivity differences between groups, ensuring equally creditworthy individuals are treated fairly. A score of means equal opportunity, while positive or negative values indicate bias.

- -

- Theil Index (TI) (Speicher et al., 2018), also known as the entropy index, measures fairness at individual and group levels. Lower values indicate equitable outcomes (), while higher values signal disparities, accounting for prediction errors and their distribution across decisions.

5. Threshold Adjustment Framework

In conventional PD modeling, the decision threshold used to classify observations as default or non-default is typically fixed at a default value, denoted by . A common choice is , corresponding to the point where the predicted PD exceeds 50%. This convention implicitly assumes symmetric mis-classification costs and balanced class distributions, conditions that rarely hold in real-world credit risk applications, where default events are relatively rare. As a result, may not provide an optimal balance between model performance and fairness. Moreover, biases across protected groups can further exacerbate disparities, as a fixed threshold may disproportionately affect certain subpopulations.

To address these limitations, this section introduces a threshold-adjustment framework, applied as a post-processing step for bias and fairness mitigation. The approach generalizes the standard practice by treating the threshold T as an optimization variable rather than a fixed constant. For a given balance between performance and fairness preferences, an optimal threshold (Equation (15)) is determined to achieve the best trade-off between the two objectives. When the relative importance of performance and fairness is uncertain, or when a robust and weight-independent decision rule is preferred, a single threshold (Equation (11)) can be identified to ensure stability across all possible weighting scenarios. Together, these thresholds provide a flexible and principled way to adjust model decisions, balancing predictive accuracy with fairness considerations while extending the conventional fixed-threshold paradigm. The performance and bias/fairness metrics considered in this work are discussed in Section 4.2.

Concerning the strategy, we will assess the performance using BA, and analyze disparities between protected groups (see Section 6.2) using group fairness metrics introduced in Section 4.2. For this, we employ the AIF360 library (Bellamy et al., 2018; Blow et al., 2023), which offers robust tools for quantifying group-based bias. It uses a weighted resampling procedure, a pre-processing technique that adjusts the relative influence of samples without modifying their labels, to examine fairness in model outcomes.

5.1. Definition and Normalization of Metrics Functions

The first step involves defining and normalizing the metric functions, each of which depends on the decision threshold value T. The normalization ensures that all metrics are expressed on a comparable scale, facilitating their combined optimization. The goal is to construct a scalarized objective function combines both performance and fairness metrics, which naturally operate on heterogeneous numerical scales. To ensure commensurability, each metric will be normalized with respect to theoretically or empirically bounded intervals. These bounded intervals provide stable reference points that align with the interpretability requirements of financial risk governance.

Let denote the function corresponding to a given metric m, and its ideal value. The normalized metric function, denoted , maps values into the interval according to:

where and are the minimum and maximum observed values of across the admissible range of T. The goal is to bring all metric values to a common scale, allowing meaningful aggregation of performance and fairness measures that may originally have different units or ranges.

The normalization process requires determining the lower and upper bounds and for each metric . These bounds are defined empirically as:

where represents the range of threshold values considered in this study. The values are typically obtained by computing each metric over a discrete grid of thresholds.

It is worth noting that we adopted the empirical min–max normalization approach because it is simple, model-agnostic, and directly grounded in the operational threshold space used by practitioners. Unlike dataset-dependent standardization methods, this approach yields normalized metrics that remain interpretable for credit risk committees and consistent with threshold-based decision rules. Since the normalization depends solely on the achievable range of metric values under threshold variation, it avoids injecting subjective assumptions or model-specific scaling factors.

5.2. Definition of the Objective Function

Once normalized, the metrics are combined into a single objective function using a weighted Tchebycheff scalarization approach (Dächert et al., 2012; Helfrich et al., 2023; Hwang et al., 1980; Silva et al., 2022). This approach enables balancing trade-offs among multiple objectives while allowing different priorities through weighting. The aggregated objective function is given by:

where is the weight assigned to metric m, and . Here, represents the normalized reference or ideal value of metric m, as discussed subsequently in Section 5.3.

This formulation minimizes the weighted deviation in each normalized metric from its ideal value. The term measures how far each metric lies from its desired target, and the weights control the influence of each metric in the optimization.

5.3. Reference Value Adjustment

In practical post-processing applications, the adjustment of the decision threshold does not modify the underlying predictive distribution of the model. Consequently, the theoretical ideal value of a metric may not be empirically attainable. To ensure numerical stability and interpretability, it is therefore reasonable to define the reference value as the best observed (empirical) value of the metric over the threshold domain . Specifically, one may set for maximization-oriented metrics and for minimization-oriented ones, leading, respectively, to or . For instance, assigning and yields and . This choice guarantees that the ideal point is attainable within the observed range and contributes to stabilizing the optimization process.

Nevertheless, to maintain consistency between the normalized metric functions and their corresponding reference (ideal) values in Equation (3), each can also be normalized using the same transformation:

This ensures that both the metric functions and their ideal targets are expressed on the same scale. For example, if a fairness metric has and an empirical range , the normalized reference value becomes , which remains consistent with the desired direction of improvement (lower values correspond to better fairness).

When assessing the quality of normalization, the position of the normalized reference value relative to the normalized interval provides an indication of the consistency between the empirical and theoretical scales. Ideally, , meaning that the empirical and adequately capture the attainable domain of the metric. When lies outside this range, it implies that the theoretical ideal cannot be reached within the observed data distribution. To quantify this discrepancy, we define the deviation magnitude:

The quantity measures how far the normalized ideal lies beyond the empirical normalized range, providing a direct indicator of potential normalization-induced bias.

Previous studies (e.g., Wang et al., 2017) have shown that the choice of normalization scheme significantly affects the stability of multi-objective optimization and the convergence of scalarization-based methods. Although there is no universal consensus on strict numerical tolerances for , we adopt heuristic bounds based on the magnitude of deviation relative to the normalized interval :

- : negligible deviation; the empirical range sufficiently captures the theoretical target.

- : moderate deviation; partial misalignment; but the normalization remains acceptable for optimization purposes.

- : substantial deviation; the theoretical ideal lies significantly outside the attainable domain, and the normalization may bias the optimization process. In such cases, the reference should be adjusted to the empirical bound ( or ) to ensure numerical stability, implying or .

These tolerance levels provide a pragmatic guideline for assessing normalization reliability and ensuring robustness of the optimization process.

5.4. Decomposing the Objective Function and Trade-Off Parameter

To better understand and control the trade-off between predictive performance and fairness, the total objective function, defined in Equation (3), can be decomposed into two components:

The first term, , captures model accuracy, while the second, , aggregates fairness and bias-related metrics. They are expressed as:

where denotes the weight assigned to performance, and are the individual weights for the fairness metrics .

This step is important since it allows us to efficiently weight the performance and bias in the objective function. In other words, it permits to access the trade-off between performance and bias via a proper assignment of weights.

Assuming for simplicity that the bias metrics weights are all equal to in this work, that is,

the relationship between the weights for the bias metrics and is given by:

The parameter is the number of bias and fairness metrics contributing to the objective function. Notice that in this work. The parameter determines the trade-off between performance and fairness.

By adjusting , the objective function becomes a function of two parameters: the threshold T and the performance weight . For example, means an equal contribution of both performance and bias, however less (more) than would mean the importance of the fairness (performance) over the performance (fairness) in the objective function. Notice that the choice of would depend on business objectives, whether the performance of the models is more, less, or equally important than the bias. Thus, by tuning , practitioners can emphasize either predictive accuracy or fairness mitigation, depending on application needs and ethical requirements.

5.5. Threshold Optimization

The goal is to identify the threshold that minimizes F, while ensuring that the result is robust to variations in . The optimal threshold balances performance and fairness, aligning with the desired objectives of the loan decision-making process. As such, they are indicative of how each model balances the trade-off between predictive accuracy and fairness in the context of the loan decision-making process. The approach described in this section is effective in achieving the goal of simultaneously minimizing the maximum weighted deviation in the metrics functions from their ideal values.

In our formulation, the objective function depends on a threshold parameter T and a weight parameter . Assuming Equation (9), the expression of Equation (5) can be written as:

where captures one aspect of the system we wish to align with a reference value , and are a set of metric functions (Equation (1)) we aim to align with target values for each index j. The parameter thus modulates the trade-off between optimizing for and the collective alignment of the .

It could be worth examining the behavior of as the threshold T approaches 0 or 1, across different values of the performance weight :

- Case (bias only): As , the objective function converges to , where . This reflects the importance of the DI, as all other normalized bias metrics vanish in this limit. For , the function converges to , where , since TI would be maximal.

- Case (performance only): As , the function converges to , since BA is minimized, making the normalized performance metric to vanish, . Same limit as , that is , since the performance metric continues to reflect low classification quality under extreme thresholds, as expected for a performance-centric objective.

- Case (mixed bias and performance): In this intermediate regime, as (or ), the function converges to (or ). This reflects a weighted trade-off between fairness and performance penalties in the extreme threshold limits.

It is important to comment that because fairness metrics are often correlated, there is a legitimate concern that one indicator could dominate the optimization. Empirically, however, correlations are only moderate, and the optimization does not collapse onto a single fairness dimension. This is because the framework aggregates normalized deviations from parity rather than raw metric values, ensuring that each metric contributes proportionally within its predefined range. Furthermore, the trade-off parameter explicitly controls the relative influence of performance versus fairness, preventing fairness metrics from overwhelming the objective and vice versa.

Also, the numerical stability of the scalarized objective can be argued from the boundedness of all normalized metrics. Since thresholds vary in and fairness metrics change smoothly with respect to threshold shifts, the resulting optimization surface remains well-behaved. Empirically, the optimization does not exhibit explosive gradients or oscillations, and multiple initialization points would converge to consistent minima. Hence, the normalization strategy we used balances interpretability, regulatory alignment, and optimization stability, ensuring that the scalarized objective remains meaningful and robust.

5.5.1. Independent Threshold

At first, we wish is to find the suitable threshold, , independently of . Thus, we frame the problem as a minimax optimization (see Du & Pardalos, 1995; Razaviyayn et al., 2020 and references therein). The goal is to minimize the objective function with respect to one variable, and to maximize the objective function with respect to another. In this case, we seek a value of T that performs well regardless of the specific weighting:

Since is a convex combination (Ref. Rockafellar, 1997) of two absolute-value terms and linear in , the inner maximum over occurs at one of the endpoints of the interval. Therefore, the worst-case scenario for a given T can be rewritten as:

The parameter thus minimizes the worst deviation between and its target value 1, and and its target value . The optimization problem simplifies to:

This formulation identifies the value of T that remains robust to variations in , rather than optimizing for a specific weighting configuration by minimizing the worst-case value of the objective function over all possible within . In this sense, can be interpreted as a robust or weight-independent solution, ensuring stable performance across different weighting preferences. In practice, this ensures that neither component dominates the error disproportionately and is particularly suited for applications requiring robustness against imbalanced weighting.

It is important to distinguish between the threshold defined in Equation (13) and the equilibrium threshold obtained when the deviations between performance and fairness are equal, that is,

The threshold corresponds to the point where the normalized deviations in performance and fairness metrics are balanced in magnitude, representing an equal-deviation condition. As such it can be interpreted as the point at which the optimization landscape transitions from being dominated by one objective to a balanced regime, where further improvements in one dimension necessarily entail trade-offs in the other. In contrast, minimizes the maximum of these deviations, yielding the smallest possible worst-case imbalance between performance and fairness objectives. While may coincide with in monotonic or well-behaved cases, in general provides a more robust solution by explicitly controlling the dominant deviation rather than merely equalizing them.

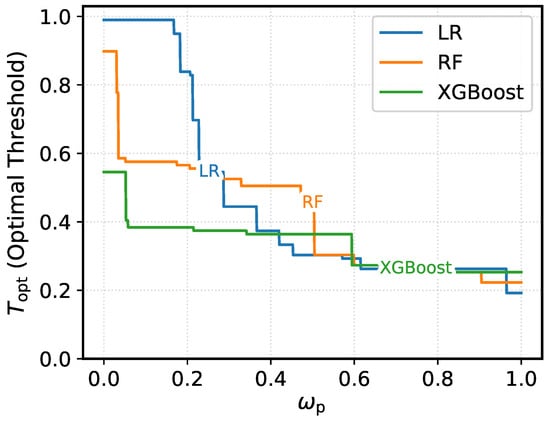

5.5.2. Influence of : Threshold

While is chosen to be independent of , it is still interesting to examine how different values of affect the behavior of , especially when a particular application might favor one objective over the other.

Recall that the parameter explicitly controls the emphasis placed on minimizing the error in versus : when , the objective prioritizes minimizing , potentially at the cost of a larger deviation in . Alternatively, when , the focus shifts towards minimizing . The intermediate values of provide a tunable trade-off between the two objectives.

This flexibility may be beneficial in settings where domain knowledge or context dictates a preference toward one function over the other. In such cases, the parameter can be selected to reflect that preference and T may be optimized accordingly:

where is given by Equation (10). The Equation (15) defines the optimal decision threshold as the value of T that minimizes the composite objective function for a given performance weight . This formulation reflects the balance between model performance and fairness objectives: a higher value of emphasizes performance-oriented metrics, whereas a lower value prioritizes bias and fairness mitigation. Accordingly, represents the optimal trade-off threshold corresponding to a specific choice of weight configuration. By varying within the range , one can explore the sensitivity of the optimal threshold to the relative importance assigned to performance and fairness, thereby characterizing the full trade-off curve between these competing objectives.

In sum, while captures the best trade-off for a chosen set of priorities, identifies a threshold that performs consistently even when the exact balance between performance and fairness is uncertain or difficult to specify.

Practical Guidance for Choosing the Trade-Off Parameter

A central component of the proposed framework is the trade-off parameter , which controls the relative influence of performance and fairness in the scalarized objective function. We acknowledge that practitioners may require more explicit guidance on its selection. In practice, should be interpreted as a policy-driven knob rather than a purely statistical hyperparameter. When the institutional objective prioritizes predictive accuracy, such as in environments with strict risk-based capital constraints, values of close to 1 will favor thresholds that maximize the performance while still accounting for fairness. Conversely, when regulatory, ethical, or reputational considerations place fairness at the forefront, choosing close to 0 yields thresholds that minimize disparities across protected groups, even at the expense of some predictive performance. Intermediate values (e.g., ) provide a controlled compromise and are appropriate when institutions aim to balance both objectives rather than optimize one exclusively.

To support practitioners, our experiments illustrate the empirical effects of varying through ratio-based plots and quadrant analyses, as discussed in Section 5.5.3, that make fairness–performance trade-offs visually interpretable. We therefore recommend a calibration procedure in which institutions (i) define acceptable tolerance ranges for both fairness and performance metrics, (ii) compute the corresponding values of across a grid of values, and (iii) select the smallest that satisfies performance constraints or the largest that satisfies fairness constraints, depending on the institutional priority. This policy-aligned calibration strategy allows the choice of to be transparent, documented, and compatible with internal model governance processes.

5.5.3. Insights into the Selection of Threshold

In the following, we give intuitive insights into the effects of threshold selection, and discuss practical decisions about when and how to adjust classification thresholds. To summarize, we distinguish:

- is the standard threshold used in binary classification, assuming calibrated probabilities and no explicit fairness correction. It’s simple and interpretable, but may perpetuate existing biases in the data.

- (defined in Equation (13)) is a fixed, model-specific threshold computed independently of the fairness–performance weight . It minimizes the maximum deviation between ideal performance and average fairness deviations.

- (given in Equation (15)) is dynamic threshold optimized to minimize the objective function that combines performance and fairness losses based on a tunable weight . This could allow institutions to explicitly tune the trade-off depending on policy priorities or regulatory requirements.

Each threshold offers different strengths. is operationally simple; would provide a robust, model-specific compromise; and allows for a tuning, context-sensitive optimization aligned with institutional priorities.

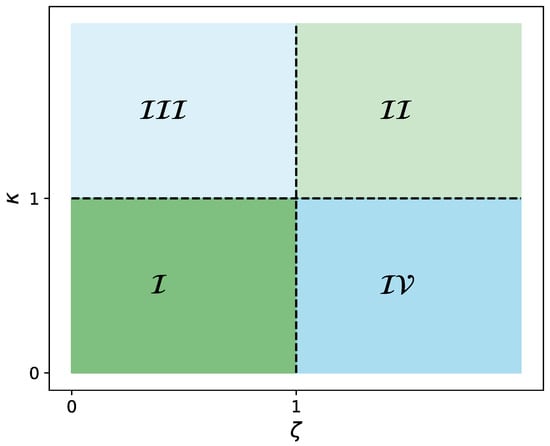

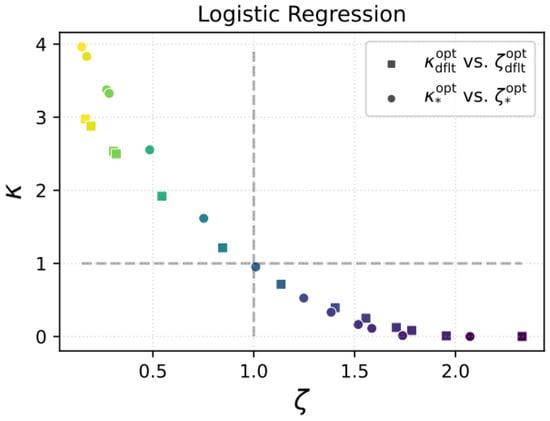

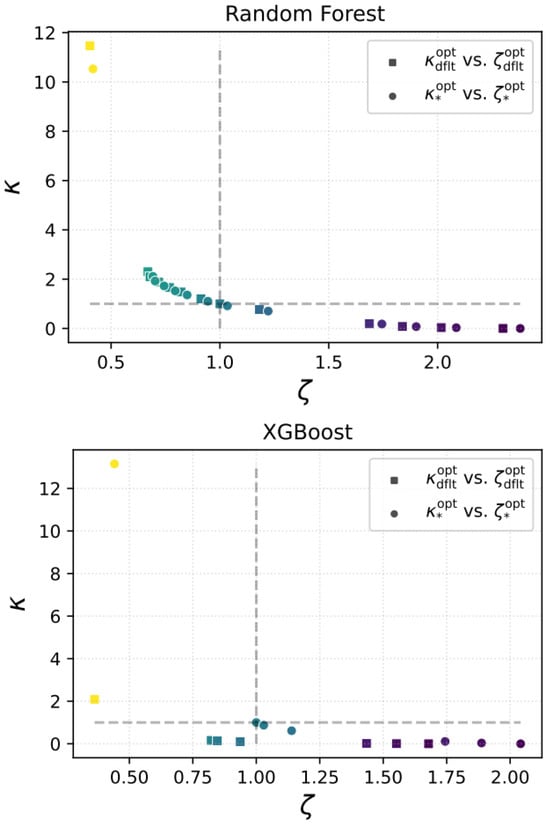

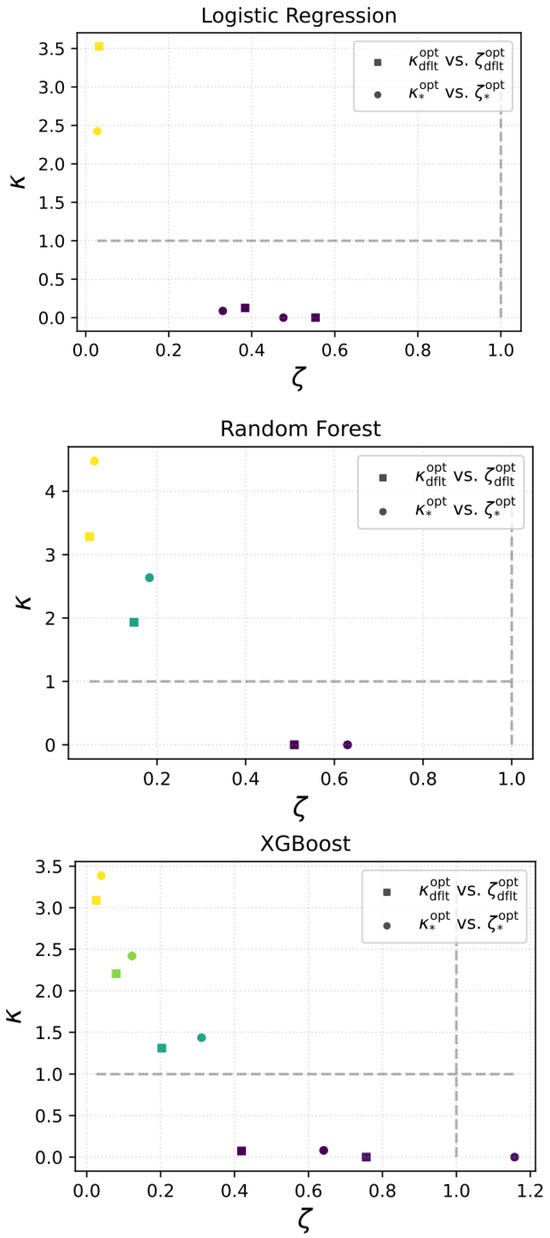

To complement the theoretical distinctions presented earlier, we now analyze threshold selection empirically through ratio-based comparisons of the objective functions. These comparisons are visualized in Figure 1, where each point corresponds to a specific value of the parameter .

Figure 1.

Visualization-based interpretation of threshold comparisons. Each point represents a comparison between thresholds, either vs. , vs. , or vs. . The x-axis denotes the fairness objective ratio, and the y-axis denotes the performance objective ratio, where values below 1 indicate improvement. Points in the bottom-left quadrant (Region I) signify that enhances both fairness and performance. The top-right quadrant (Region II) indicates deterioration in both. Region IV (bottom-right) reflects performance gains at the expense of fairness, while Region III (top-left) shows improved fairness with reduced performance. This visualization serves as a practical diagnostic tool for informed threshold selection beyond abstract optimization metrics.

To evaluate the performance of the optimized threshold relative to the default threshold , we consider the following ratios:

Points falling in the lower-left quadrant (region I) of Figure 1, where both ratios are below 1, indicate that improves both performance and fairness compared to the default threshold. Conversely, points in the upper-right quadrant (region II) suggest that remains preferable due to its simplicity or stability.

To assess whether the dynamically optimized yields benefits beyond the static fairness-optimal threshold , we define:

Here, points with both ratios below 1 again indicate simultaneous improvements. If instead they fall in region II, it implies limited added value from optimizing beyond .

For completeness, we also report the relative advantage of over the default threshold:

which are independent of and provide baseline context for interpreting the relative utility of thresholding strategies.

More generally, points in the bottom-right quadrant (region IV) signify improved performance at the cost of fairness, which may be acceptable in risk-sensitive applications. In contrast, the top-left quadrant (region III) reflects gains in fairness with a loss in predictive accuracy, a trade-off often relevant in regulated or equity-focused settings.

Finally, while this framework centers on balancing a scalarized fairness–performance trade-off, it is worth noting that competing fairness metrics may themselves be in tension. Exploring such multi-metric trade-offs is a promising direction for future research.

5.6. Positioning of the Proposed Framework Within Fairness Mitigation Strategies

We emphasize that the framework introduced above operates solely at the post-processing stage, and the threshold adjustment is model-agnostic, computationally efficient, and compatible with institutional settings where models cannot be retrained or modified once validated. However, post-processing acts only on the final model outputs and therefore cannot correct deeper structural biases arising from imbalanced data, label biases, or model design choices. For this reason, the proposed method should be viewed as a complementary tool within the broader family of fairness mitigation strategies. In settings where structural or data-driven biases are present, post-processing can be combined with pre-processing approaches and with in-processing methods that introduce fairness constraints directly during model training.

It is worth noting that incorporating fairness metrics does not increase the complexity of the underlying ML model. The proposed fairness-aware threshold optimization operates entirely at the decision layer, leaving the model’s structure intact. Rather than reducing interpretability, the approach enhances it by providing transparent, measurable indicators of fairness, as well as diagnostic tools, such as ratio curves and quadrant plots, that help practitioners understand and justify fairness–performance trade-offs.

5.7. Choice of Machine Learning Models

In this study, we illustrate this framework using some commonly used ML models. The selection of these models was guided by their complementary methodological strengths, and their balance between interpretability and predictive power. LR (Cox, 2018) is included due to its long-standing role in credit risk modeling, ease of implementation, and transparency, which make it well suited for regulatory compliance. RF (Breiman, 2001) were selected as a representative ensemble method capable of capturing non-linear feature interactions and providing robustness against noise and overfitting. XGBoost (T. Chen & Guestrin, 2016), a gradient-boosting technique, was chosen for its state-of-the-art performance on structured tabular data and its interest in financial risk management (Feng et al., 2025; Qin, 2022). Together, these three models span a spectrum from traditional interpretable methods to advanced ensemble approaches, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of our threshold optimization framework across different levels of model complexity. Importantly, this diversity enables us to analyze how fairness–performance trade-offs manifest differently between linear and non-linear classifiers.

Other models and classes of models were not considered in order to maintain clarity and focus. For example, Support Vector Machine (Cortes & Vapnik, 1995) can be computationally expensive on large datasets. More complex deep learning architectures (Mowbray, 2025), such as neural networks, were also not employed because the dataset is static and tabular, where gradient boosting and ensemble methods typically outperform. Similarly, unsupervised (Tyagi et al., 2022) or semi-supervised (Chapelle et al., 2006) approaches were not explored, since this study focuses explicitly on supervised classification with known default outcomes. By restricting the analysis to three representative and practically relevant models, we ensure that our evaluation remains methodologically rigorous, computationally tractable, and aligned with industry practices in credit risk assessment. Expanding the analysis to include these families of models constitutes a promising direction for future work, particularly for exploring whether the fairness–performance trade-offs identified in this study generalize to more complex learning systems.

5.8. Operational Deployment in Financial Institutions

Although the proposed threshold optimization framework is model-agnostic and relatively lightweight to implement, practical adoption in a financial institution requires a clear operational roadmap. This subsection outlines the key steps and governance mechanisms needed for deployment.

- Threshold Calibration Procedure: Institutions may calibrate the decision threshold using three reference values: (i) the baseline threshold , (ii) the minimax fairness-oriented threshold , and (iii) the scalarized threshold that balances performance and fairness. Calibration can be performed on a validation dataset, and thresholds be selected based on institution-specific criteria such as minimizing disparities, maximizing balanced accuracy, or meeting regulatory constraints. The choice of could be documented in model governance files in a manner similar to hyperparameter selection.

- Governance of Fairness–Performance Trade-offs: Financial institutions typically rely on established governance structures to approve model design choices. The trade-off parameter provides a clear and interpretable mechanism for documenting the tolerance for fairness versus performance deviations. Governance bodies can define acceptable fairness ranges or maximum disparities, and recalibrate the threshold periodically through back-testing, monitoring, or stress-testing exercises. This aligns naturally with existing model governance requirements, for example under Basel II/III (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, 2004, 2009, 2011, 2017), or the EU AI Act (Kelly et al., 2024; EU AI Act, 2024).

- Integration into Existing Credit-Scoring Systems: Because the proposed approach operates exclusively at the post-processing stage, it can be integrated without modifying the underlying model or retraining pipelines. The threshold adjustment can be embedded into batch scoring systems (e.g., IFRS9 staging), real-time credit decision engines, or web-based advisory tools. Furthermore, the fairness and performance metrics can be monitored through dashboards, enabling continuous supervision and documentation for compliance and audit purposes.

- Operational Considerations: The interpretability of threshold adjustment facilitates communication with loan officers and allows for human-in-the-loop decision-making. Overrides, manual reviews, and escalation mechanisms can coexist with the optimized threshold, preserving transparency and explainability. Finally, because the method affects only the final decision rule, it remains compatible with data privacy and non-discrimination requirements under GDPR (Parliament of the European Union, 2016).

Overall, this operational roadmap demonstrates that the framework is not only theoretically sound but also readily deployable within modern credit risk governance infrastructures.

6. Dataset

This study initially employs a synthetic dataset from the Kaggle platform (Kaggle, 2020), which simulates historical loan application records, and contains 32,581 observations. Although not derived from real bank data, the dataset was specifically constructed to reflect realistic credit risk scenarios. It includes a wide range of features commonly found in actual lending contexts, such as income, loan amount, interest rate, and credit history. Crucially, it reproduces structural properties often observed in production environments: class imbalance, inter-feature correlations, and the presence of proxy-sensitive attributes. These characteristics make it a suitable and controlled environment for systematically evaluating the behavior of fairness-aware decision thresholds under imbalanced and biased conditions. Given that the proposed framework is model-agnostic, post hoc, and interpretable, the synthetic data allows for insights into fairness–performance balance across different classifiers.

To further assess real-world applicability, we complement this analysis in Section 7.4 with experiments on the German Credit dataset. This serves to validate the framework’s robustness and generalizability in realistic settings. This dataset contains 1000 observations with balanced protected attributes (gender and foreign status). The list of variables is provided in Table A1.

6.1. Exploratory Analysis

The synthetic dataset includes both applicant-specific and loan-specific features, as summarized in Table 1. Variables range from demographic and financial characteristics (e.g., age, income, home ownership) to loan attributes (e.g., amount, purpose, interest rate, grade). The target variable, Loan Status, indicates whether the applicant eventually defaulted (value 1) or not (value 0).

Table 1.

Features and target variables in the synthetic dataset.

The dataset exhibits significant class imbalance, with approximately 78% of instances representing non-default cases, while only 22% correspond to defaults. To reduce the impact of this imbalance, stratified splitting and cross-validation were used during model development. Oversampling methods such as SMOTE (Chawla et al., 2002) were also tested, but yielded minimal improvements. Therefore, evaluations were based on metrics robust to imbalance, including accuracy, recall, f1-score, and AUC-ROC. Note that pre-processing steps were applied to ensure data quality and compatibility with ML models. For example, missing values in employment length were imputed with zero, and median imputation was used for missing interest rates. Numerical features were normalized to the range, and categorical features were encoded with label encoding.

A correlation analysis revealed strong linear relationships between certain features. For example, default history and age were highly correlated (), suggesting potential redundancy. Similarly, credit score and interest rate showed a correlation of , highlighting the impact of creditworthiness on loan conditions. A moderate positive correlation () was observed between interest rate and default history, indicating that applicants with past defaults tend to receive higher interest rates. On the other hand, correlations between loan amount and interest rate were weak (), implying that factors other than amount influence rate determination.

Correlations between most features and the target variable (loan status) were modest, with the highest being between credit score and default status (). Additionally, mutual information scores were low for several categorical features, such as loan purpose and home ownership, suggesting limited predictive utility. These features were retained in this study for completeness but could be excluded in a real-world optimization pipeline.

Note that although strong correlations between certain features (for example, credit score and interest rate) suggest that one of each highly correlated pair could be excluded without significantly affecting classification performance, all features are retained in this study to enable a more comprehensive and controlled comparison across models and thresholds. This choice prioritizes experimental completeness over model parsimony, recognizing that variable selection strategies may differ in production environments where interpretability and efficiency are critical.

6.2. Protected and Proxy Attributes

Distinguishing between protected and proxy attributes is a fundamental step in addressing fairness and bias. On one hand, protected variables represent attributes where discrimination is legally or ethically unacceptable, such as age. Models that rely directly or indirectly on protected variables risk perpetuating discriminatory practices if these features influence predictions in an unjust manner. Proxy, on the other hand, are attributes that are not explicitly sensitive but may correlate with protected variables. The use of proxy in predictive models can lead to unintended bias, as they may inadvertently capture patterns of historical or structural discrimination. Identifying these proxies is essential to ensure that models remain fair and unbiased.

Concerning the dataset we considered in this study, age could be a primary choice for a protected variable. Discrimination in lending practices, such as offering unfavorable terms or denying credit based on age, raises significant concerns about fairness.

Also, while features like income, property ownership and interest rate are not inherently sensitive, they can act as proxies for other sensitive or protected characteristics. Income could act as a proxy for factors such as socio-economic background, property ownership may correlate with demographic characteristics, indirectly reflecting sensitive traits such as age. Regarding the interest rate on a loan, it may be influenced by a combination of borrower-specific factors, economic conditions, and lender policies. Key borrower attributes may include loan grade, income stability, loan amount, and purpose, with for example stable incomes generally leading to lower rates.

However, correlation analysis indicates on the one hand that the target variable is moderately correlated, with interest rate () and income (), while being very low with age (). On the other hand, the default history is moderately correlated, with interest rate while very low with income about and ∼−0.003, respectively.

Therefore, as the approach in this study, we will focus on the interest rate as the protected attribute, and leave the other scenarios or combinations of scenarios for future works.

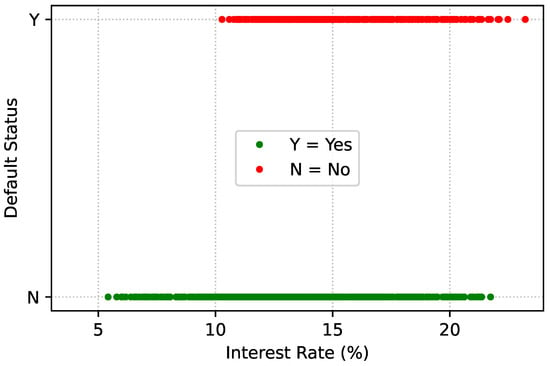

6.3. Definition of Protected Groups

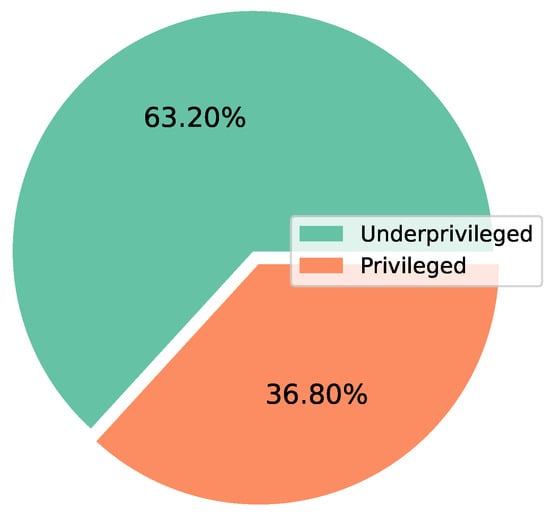

The data suggests that higher interest rates are associated with historical default status, with a critical threshold around (see Figure 2). Applicants receiving rates above this level are more likely to face rejection, possibly due to their higher risk profiles. This trend raises questions about potential systemic biases in loan approvals. If historical trends influence interest rate assignments, some groups may be disproportionately disadvantaged. Thus, there are two groups of the protected attribute: privileged which consists of applicants with an interest rate below , and the otherwise underprivileged. The proportions of these groups in the dataset can be found in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Historical default status versus Interest rates.

Figure 3.

Proportions of two groups of the sensitive variable used to access bias and fairness. Privileged (underprivileged) corresponds to group of applicants with an interest rate lower (higher) than .

7. Experimental Results

7.1. Performance of the Models

Table 2 presents the standard performance metrics for the ML models we considered. All models achieve strong overall accuracy, with RF performing best at 88.95%, followed by XGBoost at 85.58% and LR at 83.53%.

Table 2.

Performance of models. The classes 0 and 1 corresponds to non-defaults and default, respectively.

More informative than raw accuracy, the ROC-AUC scores provide insight into the models’ ability to discriminate between default and non-default cases. XGBoost achieves the highest ROC-AUC at 89.13%, closely followed by RF at 88.98%, while LR records a respectable 84.32%. These results suggest that tree-based models (RF and XGBoost) exhibit stronger discriminatory power relative to the linear baseline. Recall and F1-score values for each class reveal how models handle class imbalance. All models perform well in detecting non-defaults (class 0), with recall values above 0.95. However, performance drops sharply for defaults (class 1), which are the minority class. RF stands out with the highest recall (0.59) and F1-score (0.72) for class 1, suggesting it offers the best balance between sensitivity and precision for identifying high-risk applicants. In contrast, LR and XGBoost exhibit lower recall for class 1 (0.41 and 0.34, respectively), indicating under-detection of defaults.

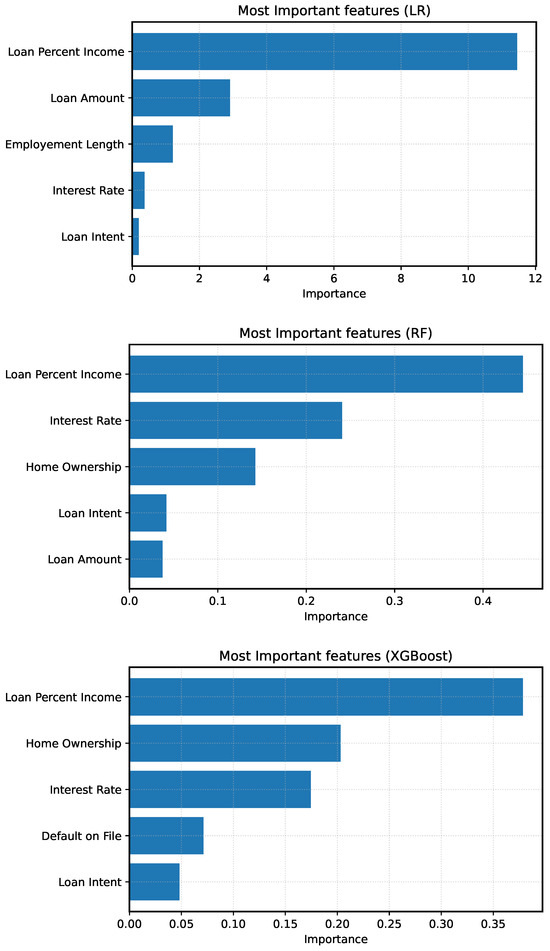

The disparity in class discrimination could come from differences in features reliance. As shown in Figure 4, LR relies most heavily on loan-to-income percent, followed by loan amount, employment length, and interest rate. Due to its linear structure, LR applies uniform penalties to high-risk indicators and lacks the nuance to account for mitigating factors such as extended work history or smaller loan sizes. This rigidity likely contributes to its limited effectiveness in detecting defaulters. In contrast, the RF demonstrates a more distributed reliance on input variables. Key drivers include Loan to Income Percent, interest rate, home ownership, loan intent, and loan amount. Thanks to its tree-based design, RF can capture nonlinear relationships and assess the conditional influence of features like Interest Rate, enhancing predictive accuracy while reducing dependence on sensitive attributes. XGBoost similarly prioritizes loan-to-income percent, with additional emphasis on home ownership, interest rate, default on file, and loan intent. Although its performance in identifying defaults is somewhat lower, its more restrained use of interest rate supports stronger fairness outcomes, as elaborated in Section 7.2.

Figure 4.

Feature importance plots for LR, RF, and XGBoost. Feature contributions highlight model reliance patterns, which may influence bias levels, especially when dominant features correlate with protected attributes.

The BA reported in Table 3, supports this interpretation. While all models achieve a BA above 0.5, suggesting meaningful prediction beyond majority class guessing, only RF scores near 0.79. LR and XGBoost trail at 0.68 and 0.67, further reflecting their weaker class discrimination performance.

Table 3.

Performance (BA) and bias & fairness (SPD, AOD, EOD, DI, TI) metrics evaluated at decision default threshold , with respect to the protected attribute interest rate. All the models considered are displayed.

7.2. Evaluation of Fairness and Bias

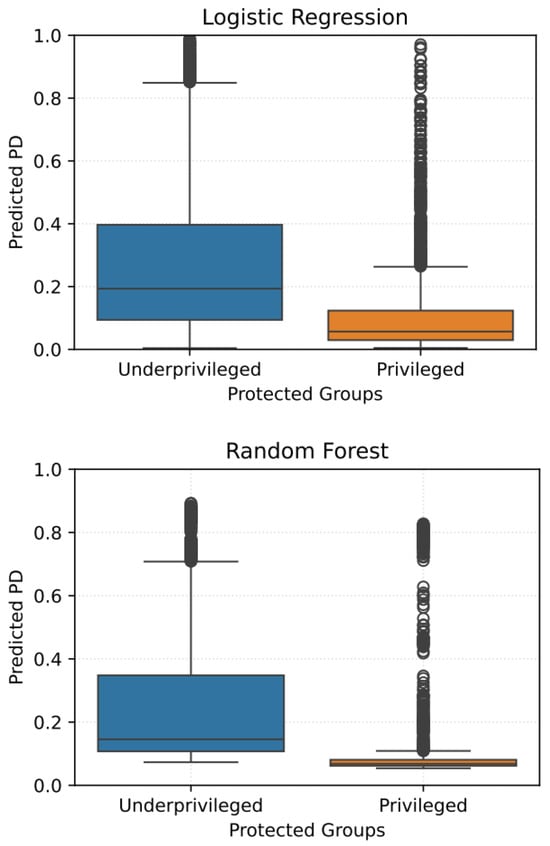

While model performance metrics highlight how well each classifier distinguishes between defaults and non-defaults, a fairness evaluation at decision default threshold reveals substantial disparities in how these predictions are distributed across protected and unprotected groups. Using interest rate as the protected attribute to define fairness groups (see Section 6.3), we observe substantial disparities in how the models treat underprivileged versus privileged individuals (Figure 5, Table 3).

Figure 5.

Distribution of predicted loan approval probabilities across protected groups (privileged vs. underprivileged). Illustrates disparities in classification rates that drive fairness metrics such as SPD and EOD.

RF exhibits stronger fairness overall. With an SPD of −0.1297, AOD of 0.0525, EOD of −0.0251, and DI of 0.8565, RF demonstrates more consistent outcomes across groups. Its low TI of 0.04057 reflects equitable probability distributions and supports its position as a reliable compromise between performance and fairness. The probability plots (Figure 5) show that RF produces relatively less severe separation between privileged and underprivileged groups compared to LR.

XGBoost remains the fairest model, with the most favorable fairness metrics: SPD = −0.02269, AOD = 0.12135, EOD = 0.0, DI = 0.975, and TI = 0.040. The almost perfect parity in positive classifications and true positive rates across groups stems from its controlled use of interest rate and heavier reliance on home ownership and default history instead. The predicted probability plot (Figure 5) shows well-overlapped distributions between privileged and underprivileged groups, indicating a lack of systemic preference toward one group over the other.

LR, on the other hand, performs poorly on fairness dimensions. It yields SPD = −0.141, AOD = 0.1286, EOD = −0.0637, DI = 0.851, and TI = 0.073. Its reliance on highly weighted features like loan to income percent and the lack of nuanced interaction of feature results in significant disadvantages for underprivileged individuals. As shown in the predicted probability graph (top left plot of Figure 5), LR separates groups, resulting in disproportionately negative outcomes for those with high interest rates.

It is worth commenting that some metrics, shown in Table 3, such as SPD, AOD, and EOD, exhibit negative values for certain models. They indicate the direction of bias rather than its magnitude. For example, a negative SPD value means that the protected group has a lower positive classification rate compared to the unprotected group. Similarly, negative AOD suggests that false positive and true positive rates are lower for the protected group. Negative values highlight that bias can disproportionately disadvantage the protected group, a critical consideration when evaluating the fairness of the model.

These results show that the selected models exhibit distinct bias profiles before any adjustment: LR displays smooth score distributions but tends to amplify disparities in SPD and EOD, while RF and XGBoost reduce some disparities yet introduce others due to their non-linear decision boundaries. When such biases are present, relying solely on the raw PD estimates can lead to systematic differences in approval rates or error rates across protected groups. The proposed threshold optimization framework directly addresses this issue by providing an interpretable and model-agnostic mechanism for mitigating disparities at the decision stage. By tuning the scalarization trade-off parameter and adjusting the decision threshold, institutions can explicitly reduce unfair group-level differences while controlling the loss in BA. This offers a practical and transparent corrective measure when baseline model outputs are biased.

7.3. Optimization of the PD Threshold

7.3.1. Performance-Based Threshold

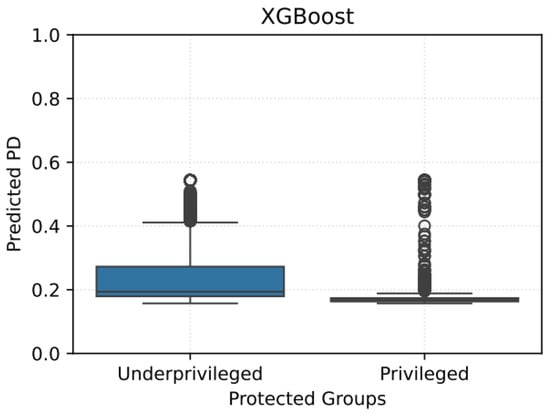

The BA of the models is analyzed across different classification thresholds for the predicted PD. For each model, the respective threshold () that maximizes performance (denoted as ) was identified, as illustrated in Figure 6. Notice that is same as setting in Equation (15).

Figure 6.

Performance of the models versus the PD decision threshold. Different colors correspond to different models. The stars indicate the points where the maximum balanced accuracy (BA+) with its corresponding threshold () are attained.

At its highest BA, LR achieved an threshold of , with moderate BA compared to the other models. RF demonstrated good performance, with a threshold of and consistently higher BA in a wide range of thresholds. Its BA curve remained stable, highlighting the model’s robustness and relative balanced classification ability for both majority and minority classes. XGBoost performed comparably to RF, with a threshold of . Its BA curve closely followed RF’s, maintaining high values across various thresholds. Despite having the largest , the shape of the curve reflects the less effectiveness of XGBoost in identifying the minority class in the dataset.

Notice that the thresholds corresponding to maximum performance for all models are below the standard . This is not surprising, since there is a class imbalance in the dataset, where the defaults cases are significantly underrepresented compared to the non-defaults cases. In this case, models are naturally biased toward predicting the majority class, often resulting in higher predicted probabilities for non-defaults class. To counter this bias and improve classification of the minority class, a lower threshold is required to increase sensitivity (recall) for defaults. The need to lower thresholds can also be explained by the objective of maximizing BA. Since it equally weighs sensitivity and specificity, it encourages a trade-off where both classes are fairly represented in the classification. By setting the threshold below , models improve recall for the minority class while maintaining reasonable specificity for the majority class.

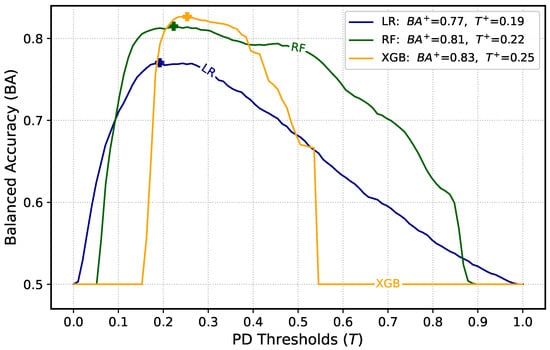

7.3.2. Trade-Offs Between BA and Fairness

We investigated the trade-off between fairness and performance across the classification models considered, by analyzing how performance BA varies with the decision threshold, and how bias & fairness metrics behave across this spectrum. For example Figure 7 presents this relationship, where BA is plotted against threshold, and SPD is encoded using a sequential color map. Lighter tones indicate SPD values closer to zero (i.e., fairer predictions), while darker tones indicate more negative SPD (greater disparity between protected groups). A black dot marks the default threshold , and a blue cross indicates the threshold that yields the maximum BA for each model.

Figure 7.

BA versus classification threshold across all models. The background color scale represents SPD, using the color map. Lighter tones (yellow-green) indicate lower disparity (SPD closer to 0), and darker tones (purple) indicate greater disparity (more negative SPD). The dot (•) indicates the default threshold ; the cross (+) denotes the threshold at which BA is maximized.

As the threshold varies from 0 to 1, we observe that BA generally improves as the threshold moves away from the default value , particularly toward lower values. This shift reflects the class imbalance present in the dataset, where the defaults class is underrepresented. Lowering the threshold increases the sensitivity toward this minority class, enhancing overall BA. However, this improvement in performance is often accompanied by increased group disparity, as indicated by rising SPD values. For example, in LR, maximum BA of 0.77 is achieved at , but with a corresponding increase in SPD.

Each model displays a distinct trade-off landscape. LR demonstrates a sharp trade-off. As the threshold decreases and the BA increases, SPD becomes significantly more negative. This suggests that fairness deteriorates rapidly as the model optimizes for performance. RF displays a smoother transition. It achieved its maximum BA of 0.81 at with moderate fairness degradation. Its contour surface suggests a stable region of operation balancing accuracy and equity. XGBoost stands out by achieving both high performance and fairness. Its maximum BA of 0.83 at is achieved within a region of relatively light coloration, indicating lower SPD and minimal fairness loss. This makes XGBoost particularly well-suited for applications requiring a fair yet accurate model.

This implies that enhancing fairness can sometimes come at the expense of accuracy, making it necessary to strike a careful balance between the two. For any given model, it’s important not to consider accuracy or fairness in isolation, but rather to examine how both objectives evolve as thresholds are adjusted.

7.3.3. Optimal Threshold

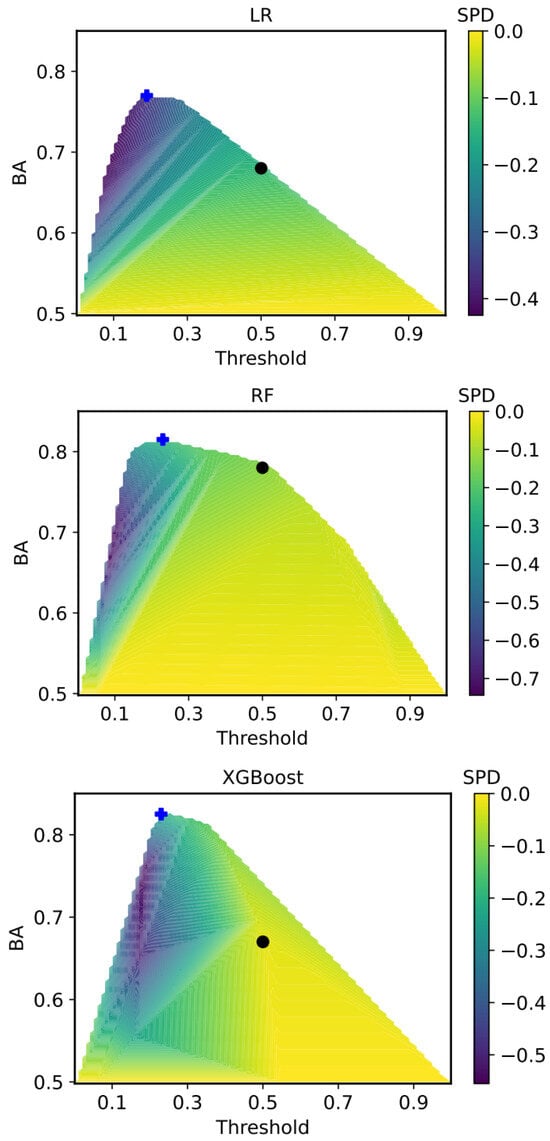

We define as the model-specific threshold that minimizes the maximum deviation between ideal performance and fairness. It corresponds to the minimax solution of the fairness objective and is formally introduced in Equation (13).

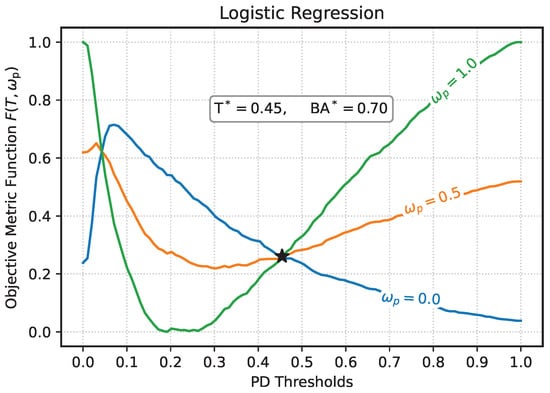

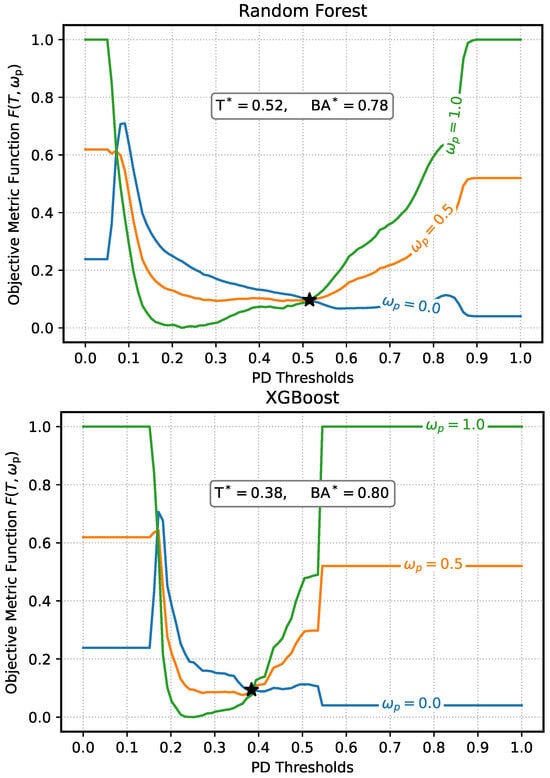

To illustrate the independence of from the trade-off parameter , we analyze the behavior of the objective function for three representative values: (performance only), (fairness only), and (equal weighting). These scenarios are shown in Figure 8 with green, blue, and orange curves, respectively. For , the objective reflects pure performance, aligning with the analysis in Section 7.3. In contrast, focuses exclusively on reducing fairness disparities, while the intermediate case reflects a balanced compromise between both objectives.

Figure 8.

Objective metric function as function of the PD threshold values for the models considered, for different values of . The parameter is given by Equation (5), and stands for the weight of performance in the objective metric function. The star (★) mark represents the point where is achieved. Recall that stands for optimal threshold determined by Equation (13), with the corresponding balance accuracy BA*.

Figure 8 compares these objective curves across models. For LR, the optimal threshold is , yielding a . This central threshold is consistent with the well-calibrated probability outputs typical of LR models. For RF, with , indicating a conservative yet stable decision boundary. XGBoost achieves the lowest threshold () and highest performance (), reflecting its strong optimization capacity and more aggressive decision boundaries.

It is also instructive to consider the limiting behavior of the objective function as or . As discussed in Section 5.5, when (fairness only) and , the objective approaches , dominated by DI term. In contrast, as , the normalized TI term dominates, pushing the objective to . For , which prioritizes performance, the function converges to the same value at both extremes: , since balanced accuracy is minimized at extreme thresholds. For intermediate trade-offs like , the limits reflect convex combinations: and , indicating gradual shifts in the trade-off as fairness and performance weights are balanced.

It is worth noting that, in each plot of Figure 8, in addition to , there exists a threshold value at which the objective function becomes independent of the performance weight . This invariance indicates that the trade-off between performance and fairness has reached a point of balance across the different metrics. Such a threshold corresponds to the equilibrium threshold defined in Equation (14), where the deviations of performance and fairness from their respective reference values are equal in magnitude. Empirically, these equilibrium points occur around , , and for the LR, RF, and XGBoost models, respectively. A closer examination reveals, however, that the value of the objective function at the equilibrium threshold, , is noticeably larger than at the optimal threshold . This observation supports the interpretation that while represents a balance point where performance and fairness deviations are equal, it does not necessarily minimize the overall objective function. In other words, corresponds to a condition of equilibrium rather than optimality. The difference between and therefore quantifies how far the balanced trade-off lies from the true optimum, offering insight into the degree of compromise required to achieve fairness–performance parity across models.

7.3.4. Effectiveness of Minimax Optimization

We examine how the optimal threshold affects both fairness and performance objectives. Table 4 displays, for each model, the relative improvement in the fairness and performance objectives when using compared to the default threshold . Recall that ratios below 1 indicate an improvement (i.e., a reduction in the corresponding objective function), while ratios above 1 indicate a deterioration. Ideally, both fairness and performance ratios should be below 1, meaning the optimized threshold improves both objectives.

Table 4.

Ratios of fairness and performance objective values at the optimized threshold , relative to the default threshold . The parameters , and are defined in Equation (18). Ratios below 1 indicate improvement in the corresponding objective function.

Concerning the model-specific results as displayed in Table 4, for the LR, the performance improves significantly by 25% (ratio = 0.75), while fairness worsens by 12.4% (ratio = 1.124). The optimization favors predictive accuracy at the cost of increased bias. For RF, the fairness improves slightly (ratio = 0.968) by approximately 3.2%, but performance worsens slightly by 8.9% (ratio = 1.089), reflecting a mild trade-off. XGBoost delivers strong gains on both fronts, with fairness ratio = 0.823 by 17.7%, and performance ratio about 0.16 by a substantial 84%. This indicates that the cut-off adjustment substantially reduces both bias and performance-related loss, making it the best dual-gain model among those tested.

This somehow highlights the model-dependent nature of post-processing threshold tuning strategy proposed in this work. While some models exhibit trade-offs between fairness and performance, others like XGBoost benefit significantly on both dimensions.

It is important to note that the minimax threshold can lie either below or above the default threshold . When , the model benefits from a more lenient decision boundary, classifying a larger share of applicants as positive. This shift increases sensitivity, as more true positives from the non-default class are correctly identified. Conversely, when , the model adopts a stricter decision rule, reducing the overall rate of positive classifications across groups. Such a reduction may contribute to narrowing disparities in fairness metrics such as SPD, AOD, or EOD.