1. Introduction

In Japan, it is common practice for banks to require personal guarantees for loans to small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

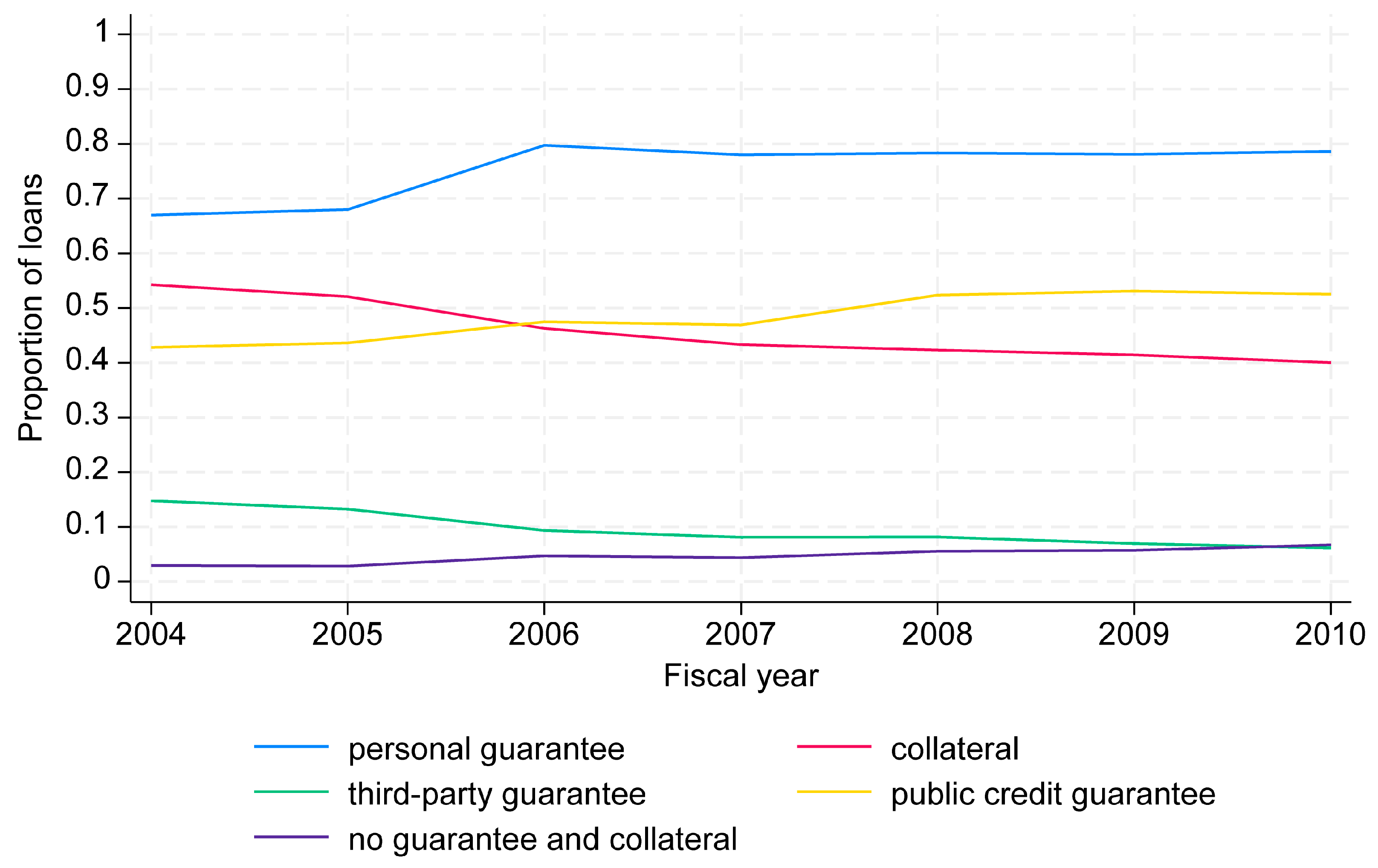

Figure 1 illustrates the percentage of companies that met the relevant conditions for loans from their main banks, based on the “Basic Survey on SMEs”

1. Between 2004 and 2010, the percentage of companies with collateral-backed loans declined from 50% to 40%. Conversely, nearly 80% of respondent companies continued to provide personal guarantees.

Meanwhile, Japanese banks have faced increasing pressure to expand lending due to declining profitability, partly driven by the Bank of Japan’s monetary easing measures, including prolonged low interest rates. Financial authorities in Japan have promoted cash-flow-based lending that does not rely on collateral or personal guarantees. In its Financial Monitoring Policy published in September 2013, the Japan Financial Services Agency (JFSA) stated that it “will try to identify obstacles behind banks’ cautious approaches for taking credit risks without collaterals and guarantees” (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2013b). Since then, the JFSA has sought to strengthen the capacity of regional banks, particularly their ability to evaluate the profitability and risks of local businesses with the aim of revitalizing regional economies and stabilizing bank profitability.

In December 2013, the Japanese Bankers Association and the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry issued the “Guidelines on Business Owners’ Personal Guarantee,” establishing voluntary rules to facilitate lending without personal guarantees (

Japan Study Group on Guidelines for Personal Guarantee Provided by Business Owners, 2013). Despite these efforts, the JFSA observed substantial variation in the efforts and effectiveness of business evaluations conducted across banks. In 2016, official benchmarks were established to evaluate financial intermediation functions using objective evaluation criteria (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2016). Furthermore, in 2019, the JFSA encouraged financial institutions to actively disclose selected indicators, such as “the percentage of new loans without personal guarantees,” to promote transparency (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2019). Consequently, most regional banks began disclosing these indicators as key performance indicators (KPIs).

Prior studies suggest that personal guarantees function similarly to collateral by helping mitigate problems arising from information asymmetry. However, they are generally less effective in transferring risk from borrower to lender (

Cadot, 2013;

Ono et al., 2012;

Ono & Uesugi, 2009). Prior studies have reported that non-performing loan (NPL) ratio, bank size, cost-to-income ratio, equity-to-assets ratio, and non-interest income determine bank profitability (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

Dietrich & Wanzenried, 2011;

Kumar et al., 2020,

2022;

Liu & Wilson, 2010). While much of the existing literature focuses on the loan contract level, few studies have examined the broader impact on bank profitability. This study fills that gap by analyzing the effect of loans without personal guarantees on bank profitability. This study employs three types of bank profitability measures: return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and return on loans. This is in light of the Japanese financial authorities’ continued efforts to promote cash-flow-based lending as a means to enhance both financial intermediation and the long-term profitability of banks.

This study addresses two main research questions. The first is whether loans without personal guarantees significantly affect bank profitability. The second concerns the role of bank management quality. Specifically, it examines whether the positive impact of such loans on profitability is more pronounced in banks with high-quality management, which are better equipped to conduct effective screening and monitoring.

To investigate these questions, the study employs two-way fixed effects models that control for both bank-specific and year-specific effects, using bank-clustered robust standard errors. Additionally, two-step Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimators are applied to address potential endogeneity issues. These methodological approaches enhance the robustness and credibility of the findings.

The empirical findings indicate that the statistical significance of the effects of the concerned loans on bank profitability is not robust. The findings also show that their average effects are less than the standard deviations of the profitability, indicating that economically insignificant. Although the effects vary slightly based on non-performing loan ratios, the marginal effects remain limited. These findings suggest that some banks may be hesitant to expand such lending due to potential credit risks, as the JFSA identified differences in financial intermediation efforts across banks (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2016).

This study contributes to literature in two ways. First, it extends prior research by examining the aggregate impact of loans without personal guarantees on bank profitability, rather than focusing solely on individual loan contracts. This study is the first to empirically examine the impact of such loans on bank profitability in the Japanese context. Second, this study offers practical insights for policymakers. Despite over a decade of promotion by Japanese financial authorities, such loans do not appear to enhance bank profitability. While reducing personal guarantees may support SMEs’ succession, their effectiveness as a KPI for bank performance remains questionable.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows.

Section 2 outlines the recent institutional background in Japan.

Section 3 reviews previous studies and presents the research questions.

Section 4 describes the research design.

Section 5 reports empirical results, and

Section 6 examines the robustness of the findings with respect to endogeneity.

Section 7 concludes.

2. Institutional Background

This section outlines key initiatives introduced by financial authorities to promote cash-flow-based lending and encourage Japanese financial institutions, particularly regional banks, to offer loans without personal guarantees from business owners.

2.1. Types of Commercial Banks and Activities of Regional Banks

Traditionally, Japanese commercial banks have three core services: deposits, lending, and exchange. Under Japanese law, including the Banking Act, financial institutions that manage deposits are classified as “deposit-taking financial institutions,” and are subject to strict supervision and regulation. This category includes ordinary banks and cooperative financial institutions, such as Shinkin banks and credit cooperatives.

2 Ordinary banks, as defined under the Banking Act, include city banks, regional banks (including regional banks II

3), foreign banks, and other types of banks.

This study focuses on regional banks, given their significant role in domestic lending to SMEs, particularly in local cities.

Table 1 shows lending and deposit trends by bank type.

4 The total amount of loans extended by regional banks rose from 185 trillion yen in 2000 to 303 trillion yen in 2025, with their share of total lending increasing from 33.9% to 47.8%. Although their share of total deposits declined marginally, from 40.9% to 39.0%, the absolute amount of deposits increased from 234 trillion yen in 2000 to 414 trillion yen in 2025.

Table 2 illustrates the trends in the number of insured financial institutions under Japanese Deposit Insurance Act.

5 In the wake of active mergers and acquisitions in the banking sector, the number of city banks and Shinkin banks has declined by approximately 54.5% and 38.9%, respectively, over the past 30 years. In contrast, the number of regional banks decreased by only about 24.8%. This relatively modest decline suggests that regional banks have maintained a stable presence by building strong relationships with high-quality local clients in their respective regions.

2.2. Policy Initiatives from Financial Authorities in Japan Since 2013

Regional banks have traditionally sustained their profitability by offering core banking services to local businesses and individuals.

6 Conversely, local cities have been experiencing a marked decline in working-age population, a trend expected to reduce the number of employees and business establishments, thereby shrinking the regional market for banking services.

Furthermore, Japanese regional banks have been facing declining lending profitability driven by narrowing interest margins under prolonged low interest rates. In April 2013, Bank of Japan introduced the “Quantitative and Qualitative Monetary Easing” at its Monetary Policy Meeting, including the adoption of monetary base control, followed by a series of additional monetary easing measures.

7 These policies are aimed at stimulating domestic demand and achieving the 2% target inflation rate; however, banks often struggle with declining profitability driven by low interest rates.

Given a low interest-rate environment, how can Japanese regional banks sustain profitability? The JFSA encourages the promotion of cash-flow-based lending, supported by proper credit assessments of businesses, to better meet potential funding needs. In September 2013, the JFSA published its annual policy report titled “New Financial Monitoring Policy.” For the first time, it integrated insights from both on-site inspections and off-site supervision of financial institutions (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2013b). In this report, the JFSA emphasized the importance of banks’ loan screening skills and expressed a strong commitment to engaging in discussions with banks on key issues. Specifically, these issues include banks’ internal factors that hinder appropriate risk-taking without over-reliance on collateral and guarantees, as well as the effective promotion of cash-flow-based lending. The JFSA further emphasized that this initiative helps strengthen banks’ own management foundations by fostering the sustainable growth of borrowers (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2025), which can be expected to improve bank profitability.

2.3. Guidelines for Personal Guarantee Provided by Business Owners

In the same year, a study group on the provision of personal guarantees for SMEs was established (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2013a). This study examines the role of personal guarantees in supporting SMEs. The central issue is exploring alternative lending practices that reduce reliance on personal guarantees and collateral. In May 2013, the group published its final report, noting that personal guarantees in lending can be beneficial, as they strengthen governance through managerial discipline, facilitate financing for SMEs, and reduce capital costs. The report also highlights the potential drawbacks of personal guarantees, including reduced borrower motivation to disclose timely and appropriate financial and management information to banks, and diminished incentives for conducting judicious screening of loans. The report proposes specific measures to address these issues and facilitate loan contracts more effortlessly, without requiring personal guarantees.

To implement the measures outlined in the final report, the Japanese Bankers Association and the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry established a study group in August 2013 (

Japan Study Group on Guidelines for Personal Guarantee Provided by Business Owners, 2013). The group published the “Guidelines for Personal Guarantee Provided by Business Owners” in December 2013, establishing voluntary rules between financial institutions and business owners to facilitate lending without personal guarantees. The guidelines contributed to a significant increase in loans without personal guarantees (

Uesugi et al., 2018).

2.4. Benchmark Indicators on Financial Intermediation

In 2016, the JFSA introduced the “Benchmark Indicators on Financial Intermediation” to objectively evaluate the role of banks in financial intermediation (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2016). Through inspections and supervision, the JFSA has sought to understand how banks promote smooth financial intermediation, including cash-flow-based lending. However, the JFSA found substantial variation in “the extent to which banks implemented financial intermediation practices.” During interviews, SMEs expressed strong concerns that banks continued to rely excessively on collateral and guarantees, with little change in their lending approach. Therefore, the JFSA recognized the need for an objective evaluation of banking practices and established benchmarks.

The JFSA proposed two types of benchmark indicators: common and optional (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2016). Common benchmarks are designed to assess banks’ efforts in promoting cash-flow-based lending. For instance, these benchmarks assess the number and amount of such loans relative to total lending. Meanwhile, optional benchmarks enable banks to conduct more appropriate and detailed self-assessments, considering differences in their business characteristics and management strategies. For instance, one of the optional benchmarks is the proportion of loans without personal guarantees of local SMEs, which constitute the bank’s main clientele. The JFSA also encourages banks to develop and disclose customized benchmarks to support more accurate self-assessment.

2.5. Data Availability of Two KPIs in Japan

Regional banks have published both common and optional benchmarks since FY 2017. However, as disclosure was not legally mandated and lacked a standard method, banks adopted various methods of disclosure. Some banks posted data on designated sections of their specified websites, while others included it in their digital publications. This inconsistency made it difficult to access and compare data across banks.

In June 2019, the Cabinet in Japan approved the document “Follow up on the Growth Strategy” and defined two KPIs to assess the effectiveness of financial intermediation (

Japan Cabinet Secretariat, 2019). The first KPI is the percentage of guarantee requests during business succession, while the second captures the proportion of new loans that do not rely on business owner guarantees (

Japan Cabinet Secretariat, 2019). As the document also emphasized the importance of visualizing both KPIs, the JFSA published detailed definitions (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2019). It also expressed its expectation that both major and regional banks would voluntarily disclose trends in these KPIs to the greatest extent possible (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2019). Subsequently, many regional banks began disclosing the two KPIs through their publications rather than as part of common and optional benchmarks. Furthermore, the JFSA began publishing semi-annual data on both KPIs for major and regional banks on its website, starting from the second half of FY 2019. It later began disclosing annual data from FY 2023 (

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2024).

At the time of writing, time-series data on both KPIs of regional banks in Japan are publicly available online.

8 This study focuses on the second KPI, the percentage of new loans that do not rely on business owner guarantees. Annual data for FY 2023 published by the JFSA were obtained, along with disclosure materials, such as disclosure reports and integrated reports available on the websites of 100 regional banks as of FY 2023. 87.4% (437 of 500 observations) of the second KPI data from FY 2019 to FY 2023 were found to be available. These data have been archived in a data repository to ensure public accessibility and transparency (

Yoshinaga & Onishi, 2025).

3. Literature Review and Research Questions

This section reviews prior studies on the role of personal guarantees in lending and identifies key determinants of bank profitability discussed in the literature. Building on these insights, the research questions of this study are formulated.

3.1. The Role of Personal Guarantees

Personal guarantees provided by business owners in loan contracts serve a direct role similar to collateral, transferring a portion of default risk from the lender to the borrower. In the presence of information asymmetry, personal guarantees also play an indirect role in mitigating adverse selection and moral hazards. Creditworthy borrowers offer collateral or personal guarantees to signal their reliability (

Bester, 1985;

Manove et al., 2001). Both collateral and personal guarantees offer borrowers an incentive to impose financial discipline on management to gain the trust of banks (

Boot & Thakor, 1994).

Jimenez et al. (

2006) utilize Spanish data to demonstrate that reliable borrowers are more likely to offer collateral when lenders cannot directly observe borrowers’ creditworthiness.

Ono et al. (

2012) examine the impact of collateral on borrower performance after loan contracts, reporting that collateralized loans improve borrowers’ profitability and reduce risk. These findings support the view that collateral helps mitigate both adverse selection and moral hazard.

However, heavy reliance on collateral and personal guarantees tends to reduce banks’ efforts to review loan applications, resulting in inefficient lending practices.

Manove et al. (

2001) theoretically show that the use of collateral in loan contracts can reduce the screening efforts of banks below the socially optimal level under information asymmetry. This could potentially lead to the financing of unviable projects.

Cadot (

2013) analyzes bank lending to wine farmers in France. He empirically demonstrates that loans secured by both collateral and bank monitoring are associated with an increased risk of repayment delays, whereas loans involving either collateral or monitoring alone reduce the risk. This suggests that the presence of collateral diminishes banks’ monitoring efforts.

Meanwhile, as personal guarantees are less effective than collateral in transferring risk from the borrower, previous studies have found their impact to be relatively weaker.

Ono and Uesugi (

2009) report no significant relationship between credit scores and the use of personal guarantees. Similarly,

Ono et al. (

2012) find that pledging personal guarantees does not significantly enhance borrowers’ profitability.

Peltoniemi and Vieru (

2013) demonstrate that personal guarantees are more likely to be required in transaction-based loans characterized by high information asymmetry. They also report that such loans carry significantly higher interest rates compared to relationship-based loans when personal guarantees are included.

Cadot (

2013) finds that personal guarantees have no significant impact on repayment delays.

Uesugi et al. (

2018) find that borrowers who obtain loans without personal guarantees, such as those with lower debt ratios and higher internal ratings from lenders, tend to be financially sound. Furthermore, they determined that borrowers using such loans after 2011 improved their creditworthiness and reduced default risks. These findings suggest that personal guarantees are not necessarily effective in preventing adverse selection or moral hazard.

3.2. Determinants of Bank Profitability

Previous studies have identified multiple factors influencing bank profitability.

9 The first factor is the NPL ratio, which reflects higher credit risk and lower management quality (

Louzis et al., 2012;

Podpiera & Weill, 2008), thereby reducing the bank’s overall profitability. Therefore, this factor is expected to have a negative impact on bank profitability. Consistent with this expectation, previous studies in Japan find a negative impact of NPLs on bank profitability (

Kumar et al., 2022). Similarly, the significantly negative relation between NPLs and bank profitability is reported in South Asian countries (

Nisar et al., 2018), Middle East and North Africa regions (

Alnabulsi et al., 2022) and Bangladesh (

Akhter, 2023). Conversely, studies from New Zealand and Italy indicate that the relation between NPLs and bank profitability is statistically insignificant or positive (

Kumar et al., 2020;

Pancotto et al., 2024).

The second factor is bank size. Larger banks are generally expected to achieve higher profitability based on economies of scale. However, smaller banks may also be profitable by lending to higher-risk customers. Therefore, previous studies have reported mixed results regarding the relationship between bank size and profitability (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

Kumar et al., 2020;

Liu & Wilson, 2010;

Mehzabin et al., 2023). Recently, bank size has been regarded as an indicator of a bank’s ability to adapt to changes in the regulatory environment. The implementation of Basel III has reportedly had a positive impact on the profitability of large banks, while exerting a negative impact on the profitability of smaller banks (

Gržeta et al., 2023).

Equity-to-assets ratio has been identified as the fourth factor influencing bank profitability, although prior studies reported mixed results regarding its effect. A high equity-to-assets ratio enables banks to pursue business opportunities more effectively and absorb unexpected losses, potentially increasing profitability (

Athanasoglou et al., 2008;

O’Connell, 2023). In contrast,

Dietrich and Wanzenried (

2011) report a significantly negative relationship between the equity-to-assets ratio and bank profitability. They argue that safer banks attracted additional savings deposits during the financial crisis but were unable to convert them into significantly higher earnings due to reduced lending demand during this period.

Liu and Wilson (

2010) report mixed findings regarding the relationship between equity ratio and profitability.

The fifth factor is non-interest income. In the United States, deregulation has enabled banks to offer non-traditional services and increase non-interest income. While non-interest services can improve bank profitability (

Mehzabin et al., 2023), they also tend to increase risk significantly, resulting in less favorable risk-return trade-offs on average (

DeYoung & Rice, 2004;

Stiroh & Rumble, 2006). In Europe, non-interest income is associated with a decline in profitability and increased risk among small banks, a trend attributed to their limited experience in generating such income (

Mercieca et al., 2007). However, evidence from Japanese regional banks shows mixed effects of revenue diversification on profitability (

Liu & Wilson, 2010). When the ratio of non-interest income is low, it tends to have a positive effect on profitability (

Gambacorta et al., 2014). Higher levels of non-interest income have been linked to both higher profitability and reduced risk, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic (

Li et al., 2021). Furthermore, the impact on profitability varies between fee and commission income and other forms of non-interest income (

Nisar et al., 2018).

3.3. Research Questions

For over a decade, Japanese financial authorities have encouraged lending practices that do not rely on personal guarantees. However, the impact of loans without personal guarantees on bank performance remains underexplored. This study examines the impact of such loans on bank profitability, considering the recent advances in disclosure among Japanese regional banks.

If banks can appropriately evaluate borrowers’ creditworthiness without relying on personal guarantees, they may enhance profitability by charging higher interest rates. Since companies that do not provide personal guarantees tend to achieve higher profitability after loan agreements, compared to those that do (

Uesugi et al., 2018), they are likely to afford the higher interest rates. Meanwhile, loans without personal guarantees are also expected to involve higher screening and monitoring costs to mitigate adverse selection and moral hazard, which could negatively affect bank profitability. Moreover, if the impact of such loans is negligible, no significant impact will be observed. Accordingly, this study poses its first research question (RQ1) without hypothesizing the direction of the effect:

RQ1. Do loans without personal guarantees have a significant impact on bank profitability?

The impact of such loans on bank profitability is influenced by the quality of bank management. Banks with high-quality management are more likely to benefit from such loans through effective screening and monitoring. Several studies have shown that bank profitability is significantly affected by non-performing loan ratio (

Kumar et al., 2022;

Nisar et al., 2018), indicating higher credit risks and lower management quality (

Louzis et al., 2012;

Podpiera & Weill, 2008). Accordingly, this study poses the second research question (RQ2):

RQ2. Is the positive impact of loans without personal guarantees on bank profitability significant in banks with high-quality management?

4. Materials and Methods

This section presents the research design to address the research questions, describing the regression models employed, the data sources used, and the definitions of all variables.

4.1. Models

The statistical analyses in this study are conducted using Stata version 19.5. To explore the research questions, this study employs two-way fixed effects models that incorporate both bank-specific and year-specific fixed effects, with bank-clustered robust standard errors.

10 Equations (1) and (2) are used to evaluate RQ1 and RQ2, respectively.

Details of the variables are provided in

Appendix A.

represents bank profitability. This study employs three distinct measures of profitability:

,

and

.

is the return on loans, directly reflecting the profitability of loans.

and

represent ROA and ROE, respectively. These two indicators reflect the bank’s overall profitability.

represents the proportion of new loans not contingent upon personal guarantees. RQ1 focuses on the coefficient of

in Equation (1), which captures the relationship between loans without personal guarantees and bank profitability.

represents the proportion of non-performing loans. A high non-performing loan ratio is considered to reflect poor management quality in the literature (

Louzis et al., 2012;

Podpiera & Weill, 2008). Banks with high-quality management are more likely to conduct effective screening and monitoring, enabling them to lend to creditworthy borrowers even without requiring personal guarantees. Therefore, this study focuses on the coefficient of the interaction term

in Equation (2) to explore RQ2.

Both models contain control variables based on the prior studies on bank profitability stated in

Section 3.2.

is the bank size and

denotes the cost-to-income ratio.

represents the equity-to-assets ratio.

is lending services ratio of revenue.

4.2. Data and Variables

This study uses data from 100 regional banks listed in the 2023 annual data on the utilization of the guidelines on personal guarantees, published by the JFSA, to calculate

(

Japan Financial Services Agency, 2024). All of these banks have fiscal year-ends in March.

is the proportion of new loans not contingent upon personal guarantees. Given the improvements in disclosure practices among regional banks since FY 2019, this study manually collects data concerning

from the JFSA data and publications by regional banks from FY 2019 to 2023. The manually collected dataset is archived in a public data repository for reproducibility (

Yoshinaga & Onishi, 2025).

Other variables are calculated using annual non-consolidated financial data obtained from NEEDS Financial Quest 2.0 for each bank. is the ratio of interest on loans and discounts (FINFSTA’D11023) to loans and bills discounted (FINFSTA’B11053). is the ratio of ordinary income (FINFSTA’D11115) to total assets (FINFSTA’B11098). is the ratio of net income (FINFSTA’D11145) to equity capital (FINFSTA’C11113). The deflators of the profitability variables are the averages of previous and current periods. is the non-performing loans ratio (FINFSTA’K11179). is calculated as the natural logarithm of total assets (FINFSTA’B11098). is the ratio of ordinary expenses (FINFSTA’D11060) to ordinary revenue (FINFSTA’D11021). is calculated as the ratio of equity capital (FINFSTA’C11113) to total assets (FINFSTA’B11098). is the ratio of interest on loans and discounts (FINFSTA’D11023) to ordinary revenue (FINFSTA’D11021).

After constructing these variables for each observation, those with missing values were excluded. Observations with values corresponding to the upper and lower 1% of each variable were excluded as outliers. Descriptive statistics for the final sample are presented in

Table 3, encompassing 352 bank/year observations from FYs 2019 to 2023. The average of

suggests that the loan interest rate of Japanese regional banks is approximately 1%. On average,

is more than 15 times greater than

driven by the high financial leverage of commercial banks. The average value of

is 38.8%, whereas the minimum and maximum values are 14.8% and 78.4%, respectively. This variation suggests that the implementation of loans without personal guarantee varies substantially across banks. Descriptive statistics for

are also presented. The mean value of

indicates that the proportion of such loans increased by an average of 6.4% annually.

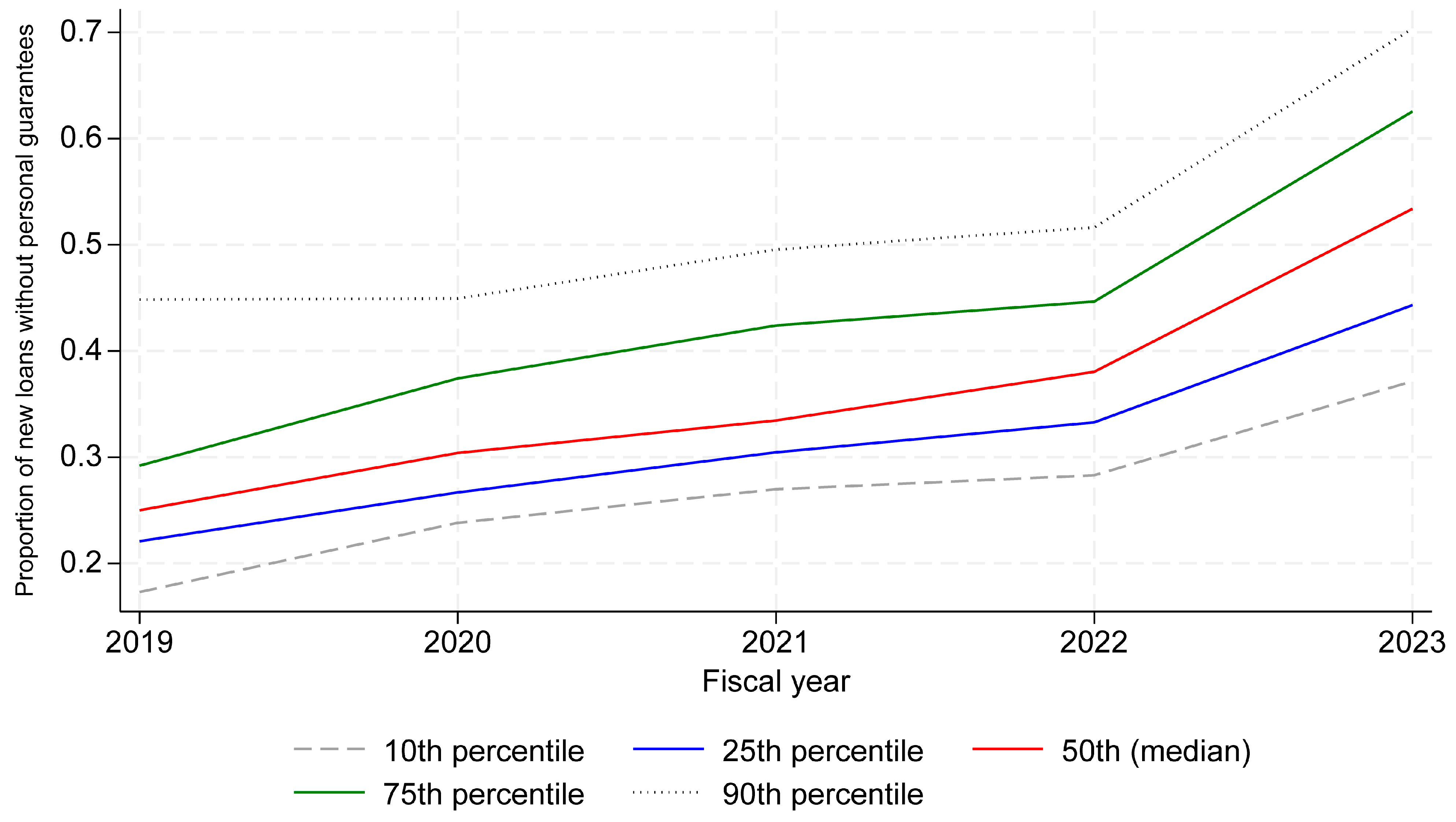

Figure 2 illustrates the time-series trend of

, showing a consistent upward trajectory over time.

Table 4 presents the correlation matrix for the variables.

and the profitability variables (

,

and

) are not strongly correlated.

does not show a strong correlation with

and

, suggesting that higher loan interest rates do not necessarily translate into greater overall bank profitability. Furthermore,

shows a positive correlation with

and a negative correlation with

, whereas

and

are negatively correlated. This suggests that regional banks that are more active in lending to high-risk borrowers tend to charge higher interest rates, whereas larger banks tend to lend to lower-risk borrowers.

and

are strongly negatively correlated with

, aligning with previous studies.

5. Results

Table 5 presents empirical results. Columns (1) and (2), (3) and (4), and (5) and (6) present the results with

,

and

as the dependent variable, respectively. The consistently high adjusted R-squared values across all columns indicate that the models are well-specified and include sufficient control variables.

Based on Columns (1), (3) and (5), which address RQ1, the coefficient of is statistically significantly positive when is used as a dependent variable. However, based on the coefficient values, an average change in the ratio of (6.4%) is associated with a 0.013% (=0.002 × 6.4%) increase in the return on loans, a 0.000% (=0.000 × 6.4%) increase in ROA, and a 0.064% (=0.010 × 6.4%) increase in ROE. These values are substantially lower than the standard deviations of (0.3%), (0.1%), and (1.8%). Therefore, the results suggest that the economic impact of the proportion of loans without personal guarantee on bank profitability is minimal.

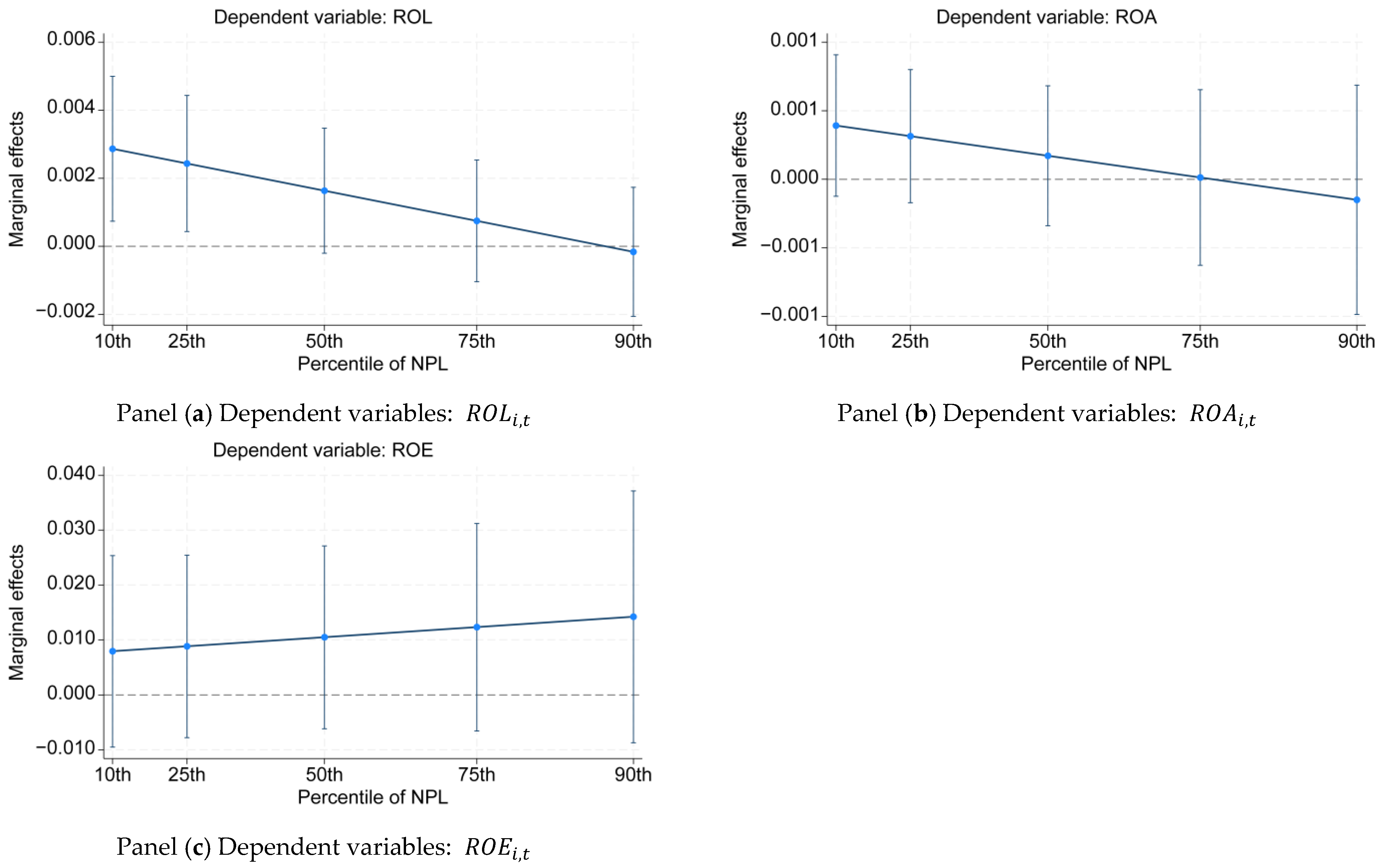

In Columns (2), (4) and (6), where

is used as the dependent variable, only the coefficient of the interaction term

is significantly negative. This finding may suggest that the positive impact of such loans on loan interest rates is more pronounced in banks with high-quality management. Accordingly, the marginal effects of

are examined in

Table 6.

Table 6 presents and

Figure 3 illustrates the marginal effects of

at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles of

, based on Equation (2). Similar to

Table 5,

Table 6 shows that a statistically significant and positive marginal effect of

is observed when

is used as the dependent variable. Panel A indicates that the effect on

becomes stronger as

decreases. However, between the 10th and 90th percentiles of

, an average change in

results in only a modest improvement in

: 0.020% (=0.003 × 6.4%) at most. In Panel B, the marginal effects of

on

are approximately zero across the same percentile range. Panel C shows that the positive marginal effect of

on

is not statistically significant within the 10th to 90th percentile range of

Additionally, within this percentile range, an average change in

leads to only a modest improvement of 0.090% (=0.014 × 6.4%) in

, at most. Overall, all marginal effects are substantially smaller than the standard deviations of the respective profitability measures. When

falls within the 10th to 90th percentiles, the marginal effects of

on bank profitability are not economically significant.

In summary,

Table 5 and

Table 6 indicate that the marginal effects of loans without personal guarantees remain economically insignificant regardless of the management quality of banks. Prior studies report that, in Japan, personal guarantees have an insignificant effect on borrowers’ profitability (

Ono et al., 2012) and credit scores (

Ono & Uesugi, 2009). Given these weaker effects, their impact on bank profitability is also likely to be insignificant. Alternatively, another plausible explanation is that personal guarantees are discontinued only for clients whose business performance is sufficiently stable, so that risk and interest of lending do not increase even without personal guarantees. These findings challenge the intended policy outcomes promoted by Japanese financial authorities. Japanese financial authorities have encouraged such loans, with one of the primary objectives being the stabilization of bank profitability. However, the results indicate that even if the proportion of such loans increases, the resulting improvement in bank profitability appears to be negligible.

As

Table 4 shows, the control variables used in the models exhibit significant correlations, potentially introducing bias owing to multicollinearity. To address this issue, a robustness check was conducted by re-estimating the models using only the main principal components of the control variables. The untabulated results confirm that the coefficients and significance levels of the variables of interest remain largely consistent with those reported in

Table 4 when the models incorporate the first through third principal components in place of the original control variables.

6. Robustness to Endogeneity

The results from the fixed-effects model presented in

Section 5 may be biased due to endogeneity. To address this potential problem, this study also estimates a dynamic panel data model using the two-step system GMM estimator (

Blundell & Bond, 1998), consistent with research on bank profitability (

Alnabulsi et al., 2022;

Dietrich & Wanzenried, 2011;

Gržeta et al., 2023;

Kumar et al., 2020,

2022;

Liu & Wilson, 2010;

Pancotto et al., 2024). The empirical analysis is based on Equations (3) and (4)

11:

The lagged dependent variable (

) and other potentially endogenous variables—specifically, all explanatory variables except the year dummies in Equations (3) and (4)—are treated as GMM-style instruments. Following

Blundell and Bond (

1998) and

Roodman (

2009a,

2009b), only the second lag of these endogenous variables is used as instruments to avoid weak instruments and mitigate instrument proliferation. To further address the issue of instrument proliferation and ensure estimation stability, the instrument set is collapsed (

Roodman, 2009b). Year dummies (

) are included as exogenous instruments in levels to control for time-specific effects

12. Robust standard errors with Windmeijer’s correction are employed to address heteroskedasticity and finite-sample bias in the two-step estimation. Model validity is assessed using the Hansen test for overidentifying restrictions and the Arellano–Bond test for the second-order autocorrelation (AR(2)) in first differences (

Roodman, 2009b).

Table 7 reports the results of this robustness check. The number of observations is smaller than in

Table 5 due to the inclusion of lagged dependent variables. The

p-values from the Arellano–Bond test for AR(2) in the first-differenced residuals are consistently insignificant across all specifications, supporting the validity of the moment conditions. The

p-values from the Hansen test, excluding Column (4), are also insignificant, supporting the validity of the instrument specification. In Column (4) only, the

p-value from the Hansen test is slightly significant at the 10% level, which may indicate the instrument specification in this column is not valid. Therefore, to further assess the robustness of the results, the two-step difference GMM estimator is also employed as discussed in the final paragraph in this section (untabulated).

In contrast to

Table 5, all coefficients of

and

are statistically insignificant. This finding suggests that the statistical significance of the positive effect of

is not robust even when accounting for bank management quality.

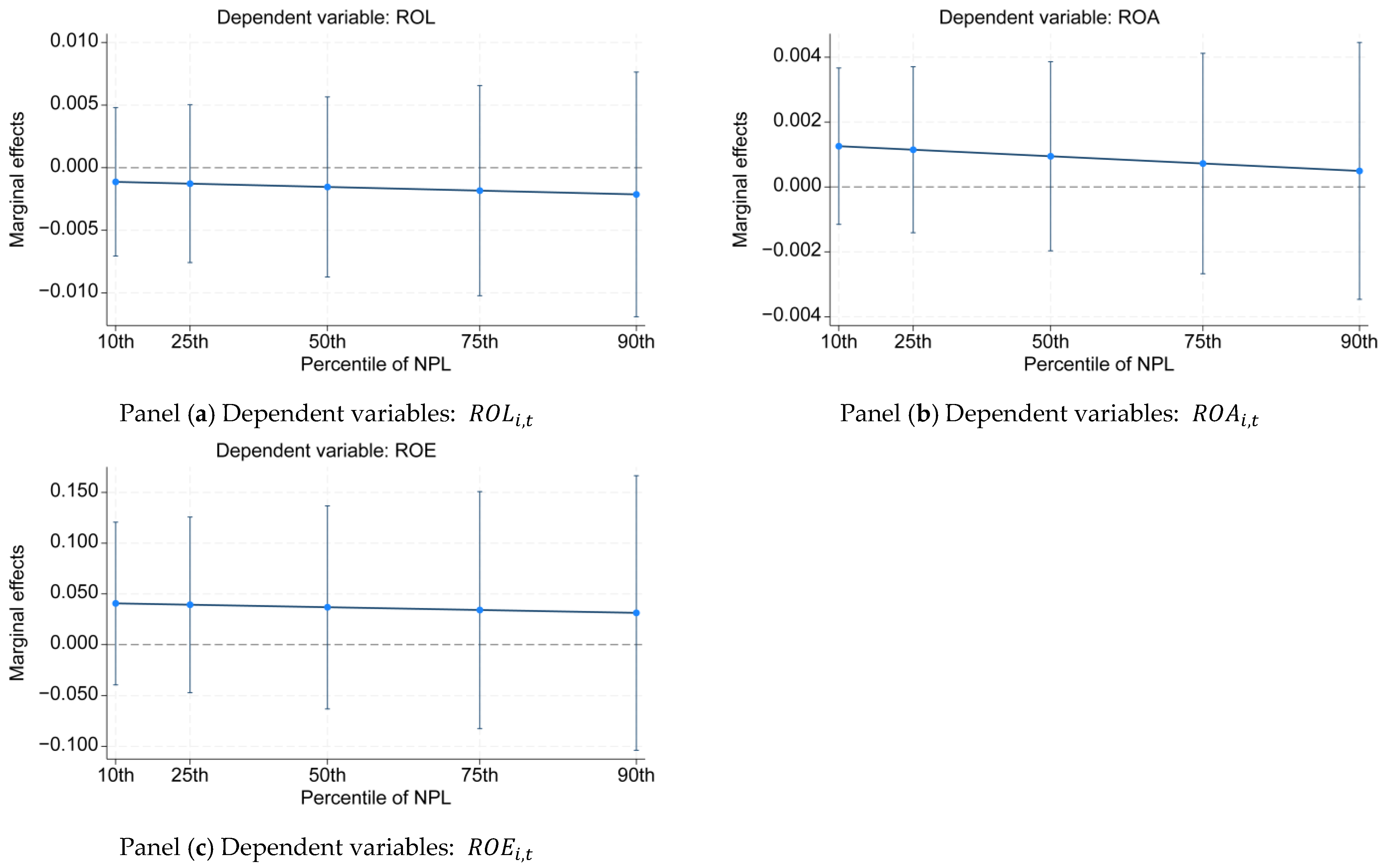

Table 8 reports and

Figure 4 illustrates the marginal effects of

at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of

, based on Equation (4). Across these percentiles, all marginal effects of

are statistically insignificant, consistent with

Table 7. Within the 10th to 90th percentiles of

, an average change in

leads to an increase of −0.006% (=−0.001 × 6.4%) in

, 0.006% (=0.001 × 6.4%) in

, and 0.262% (=0.041 × 6.4%) in

at most. All of their absolutes are substantially smaller than the standard deviations of the respective profitability measures. These results support the conclusion that the effect of loans without personal guarantees on bank profitability is economically insignificant.

To ensure the robustness of the results obtained from the two-step system GMM estimator, an alternative specification, the difference GMM estimator, is also employed (untabulated)

13. The

p-values from the Hansen test and the Arellano–Bond test for AR(2) in the first-differenced residuals are consistently insignificant across all specifications, supporting the validity of the moment conditions. Consistent with the findings from the system GMM specifications, the coefficients of

and

remain statistically insignificant, and their economic significance is minimal. These results reinforce the robustness of the overall conclusion.

7. Conclusions

This study empirically investigates the impact of loans without personal guarantees on the profitability of regional banks. The findings confirm that the statistical significance of the impact is not robust and that such loans have no economically significant impact on overall bank profitability, despite the level of non-performing loan ratios of the banks. Therefore, even as the proportion of the concerned loans increases, it does not significantly influence bank profitability.

This study contributes to literature in both academic and practical terms. First, although previous studies have analyzed the effects of loans without personal guarantees at the loan contract level, the broader impact on lenders’ overall profitability has remained unexplored. This study addresses the gap by demonstrating the insignificant impact of the ratio of such loans on bank profitability. Considering that both previous Japanese studies (

Ono et al., 2012;

Ono & Uesugi, 2009) and non-Japanese studies (

Cadot, 2013;

Peltoniemi & Vieru, 2013) highlight the limited impact of personal guarantees at the contract level, the concerned loans will not have a significant impact on lenders’ profitability outside Japan.

Second, financial authorities in Japan have been actively promoting lending without relying on personal guarantees for over a decade, while enhancing transparency through the introduction of KPIs. In 2019, the JFSA shifted its focus from flexible benchmarks, allowing banks to select multiple indicators for financial intermediation, to the standard disclosure of two selected KPIs. One of these KPIs is the percentage of new loans that do not rely on business owner guarantees. However, the findings of this study indicate that an increase in the proportion of such loans does not contribute significantly to bank profitability. This suggests that the proportion of such loans may not serve as an effective KPI for improving banks’ financial performance and management stability.

This study has several limitations and suggestions for future research. The first limitation is that the modest sample size and short sample period may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to data constraints regarding the loans examined, the sample comprises 352 bank/year observations and spans five years from 2019 to 2023, which includes the COVID-19 pandemic period. Although the results are robust under both the two-way fixed effects and GMM approaches, they may still be subject to distortion. Future research could address this limitation: reanalyzing the effects once longer-term data become available, conducting similar analyses in other countries, and utilizing international datasets.

The second limitation is that this study does not answer the question of why such loans do not significantly impact bank profitability. One possible explanation is that many new loans without personal guarantees are rollovers of existing loans extended to dependable borrowers, rather than credit extended to unfamiliar clients. Collateral and personal guarantees play a key role in mitigating lenders’ risk. When banks extend loans to new borrowers without collateral or personal guarantees, they face higher screening and monitoring costs, along with increased credit risk. However, new loans to existing reliable borrowers entail lower costs and risks for banks, reducing the need to significantly increase interest rates. Consequently, it is plausible that banks primarily issue such loans to existing reliable borrowers, which may explain why these loans do not have a significant impact on bank profitability. Addressing the mechanism is one of the promising future research projects.

As the third limitation, this study does not investigate the other social benefits of loans without personal guarantees, because it focuses on their effects on bank profitability.

Hoshi and Shibuya (

2023) report that reducing reliance on personal guarantees facilitates business succession in SMEs. Investigating the other social benefits of reducing personal guarantees is a possible future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Y. and K.O.; methodology, Y.Y.; software, Y.Y.; validation, Y.Y. and K.O.; formal analysis, Y.Y.; investigation, Y.Y.; resources, Y.Y.; data curation, Y.Y. and K.O.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Y. and K.O.; writing—review and editing, Y.Y. and K.O.; visualization, Y.Y.; supervision, Y.Y.; project administration, Y.Y. and K.O.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. and K.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, grant number: 25K16768. The APC was funded by Tohoku University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We thank anonymous reviewers for the time and effort spent to provide us with useful comments. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepL translator Pro and Copilot to improve the readability and language of the text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FY | Fiscal year |

| GMM | Generalized Method of Moments |

| JFSA | Japan Financial Services Agency |

| KPIs | key performance indicators |

| NPL | non-performing loan |

| ROA | Returns On Assets |

| ROE | Returns On Equity |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variable definitions and calculations.

Table A1.

Variable definitions and calculations.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|

| A variable on bank profitability which represents three distinct measures of profitability: , and |

| The return on loans, calculated as the ratio of interest on loans and discounts (FINFSTA’D11023) to the average balance of loans and bills discounted (FINFSTA’B11053) across the current and previous periods. |

| Returns on assets, calculated as the ratio of ordinary income (FINFSTA’D11115) to the average balance of total assets (FINFSTA’B11098) across the current and previous periods. |

| Returns on equity, calculated as the ratio of net income (FINFSTA’D11145) to the average balance of equity capital (FINFSTA’C11113) across the current and previous periods. |

| The proportion of new loans not contingent upon personal guarantees, sourced from the JFSA data and online publications of regional banks. |

| The proportion of non-performing loans, as represented by the non-performing loans ratio (FINFSTA’K11179). |

| Bank size, calculated as the natural logarithm of total assets (FINFSTA’B11098). |

| Cost-to-income ratio, calculated as the ratio of ordinary expenses (FINFSTA’D11060) to ordinary revenue (FINFSTA’D11021). |

| Equity-to-assets ratio, calculated as the ratio of equity capital (FINFSTA’C11113) to total assets (FINFSTA’B11098). |

| Lending services ratio of revenue, calculated as the ratio of interest on loans and discounts (FINFSTA’D11023) to ordinary revenue (FINFSTA’D11021). |

| The first difference of , defined as . |

Notes

| 1 | |

| 2 | Deposit-taking financial institutions in Japan include: (1) ordinary banks, governed by the Banking Act, (2) trust banks, which are authorized to engage in trust business under the Banking Act and the Act on Concurrent Operation of Trust Business by Financial Institutions, (3) long-term credit banks, formerly governed by the Long-Term Credit Bank Act, (4) Shinkin banks established under the Shinkin Bank Act, (5) credit cooperatives, governed by the Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Cooperative Act and the Act on Financial Business by Cooperatives, (6) agricultural, forestry and fishery financial institutions, based on the Agricultural Cooperatives Act and the Fishery Cooperatives Act, and (7) labor banks, regulated by the Labor Bank Act. |

| 3 | Regional banks II emerged from mutual banks, which were established under the Mutual Bank Act of 1951. Currently, regional banks I and II can be differentiated by their respective industry associations. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | Similar to regional banks, Shinkin banks and credit cooperatives also operate within a specific region. However, under related laws and regulations, these institutions are founded on the principle of mutual assistance among local businesses and residents who are also their members. While these institutions are benefited from preferential tax treatment, they are subject to restrictions on eligible clients and operational areas. Moreover, many of these institutions do not disclose enough data necessary for the analysis. Therefore, this study excludes them from the sample. |

| 7 | The main policies of Bank of Japan at the time included (1) expansion of easing (October 2014), (2) introduction of complementary measures (December 2015), (3) implementation of quantitative and qualitative monetary easing with a negative interest rate (January 2016), (4) strengthening of easing measures (July 2016), and (5) introduction of yield curve control through short- and long-term interest rate operations (September 2016). |

| 8 | Nevertheless, the following challenges remain regarding the disclosure of data for the two KPIs: (1) limited availability of historical data in some cases, (2) lack of standardization in disclosure formats, and (3) the fact that while many banks publish full-year data, some continue to disclose only semi-annual figures. |

| 9 | Several studies have observed that macroeconomic factors such as monetary policy impact bank profitability ( Alnabulsi et al., 2022; Pancotto et al., 2024). However, this section reviews bank-level determinants of bank profitability because time-specific effects are controlled in fixed effect models in this study. |

| 10 | Although GMM has been employed in previous studies on bank profitability, this study adopts a fixed effects model for the main analysis due to the limited number of observations ( Liu & Wilson, 2010). The following STATA command is adopted: areg depvar varlist, cluster(firmcode) a(firmcode year). |

| 11 | Specifically, this study adopts the following STATA command to estimate Equations (3) and (4): xtabond2 depvar varlist i.year, gmm(varlist, lag(2 2) collapse) iv(i.year, eq(level)) twostep robust. |

| 12 | The model does not include bank dummies, because bank-specufic fixed effects are accounted for through first-differencing in the system GMM estimator ( Roodman, 2009b). |

| 13 | The following STATA command is adopted: xtabond2 depvar varlist i.year, gmm(varlist, lag(2 2) collapse) twostep robust. |

References

- Akhter, N. (2023). Determinants of commercial bank’s non-performing loans in Bangladesh: An empirical evidence. Cogent Economics & Finance, 11(1), 2194128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnabulsi, K., Kozarević, E., & Hakimi, A. (2022). Assessing the determinants of non-performing loans under financial crisis and health crisis: Evidence from the MENA banks. Cogent Economics & Finance, 10(1), 2124665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasoglou, P. P., Brissimis, S. N., & Delis, M. D. (2008). Bank-specific, industry-specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 18(2), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, H. (1985). Screening vs. rationing in credit markets with imperfect information. The American Economic Review, 75(4), 850–855. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, A. W. A., & Thakor, A. V. (1994). Moral hazard and secured lending in an infinitely repeated credit market game. International Economic Review, 35(4), 899–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadot, J. (2013). Collateral, bank monitoring and firm performance: The case of newly established wine-farmers. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 57(3), 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, R., & Rice, T. (2004). Noninterest income and financial performance at U.S. commercial banks. Financial Review, 39(1), 101–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A., & Wanzenried, G. (2011). Determinants of bank profitability before and during the crisis: Evidence from Switzerland. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 21(3), 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambacorta, L., Scatigna, M., & Yang, J. (2014). Diversification and bank profitability: A nonlinear approach. Applied Economics Letters, 21(6), 438–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gržeta, I., Žiković, S., & Tomas Žiković, I. (2023). Size matters: Analyzing bank profitability and efficiency under the Basel III framework. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T., & Shibuya, Y. (2023). Breaking the barrier: How personal guarantees on small business loans impede CEO succession [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Tokyo Center for Research and Education in Program Evaluation DP-138, University of Tokyo Center for Advanced Research in Finance F-554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Cabinet Secretariat. (2019). Follow-up on the growth strategy. Available online: https://www.cas.go.jp/jp/seisaku/seicho/pdf/fu2019en.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2013a). Chūshō kigyō ni okeru kojin hoshō-tō no arikata kenkyūkai [The study group on the role of personal guarantees in small and medium enterprises]. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/singi/chushoukigyou/index.html (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2013b). Summary of the financial monitoring policy in the program year 2013. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/en/refer/measures/20130927-1/02.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2016). Kin’yū chūkai kinō no benchimāku ni tsuite: Jikotenken, hyōka, kaiji, taiwa no tsūru to shite [Benchmarks for financial intermediation functions: As tools for self-assessment, disclosure, and dialogue]. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/28/sonota/20160915-3.html (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2019). Kin’yū chūkai no torikumi jōkyō o kyakkanteki ni hyōka dekiru shihyō-gun (KPI) ni tsuite [The KPIs to objectively reflect the efficiency of financial intermediation]. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r1/ginkou/20190909.html (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2024). Shuyōkōtō oyobi chiiki ginkō no “keieisha hoshō ni kansuru gaidorain” no katsuyō jisseki-tō ni tsuite (kobetsukō no jisseki oyobi torikumi hōshin no kōhyō jōkyō) [Utilization of the “guidelines for personal guarantee provided by business owners” by major banks and regional banks]. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/policy/hoshou_jirei/jisseki_kobetsu.html (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Financial Services Agency. (2025). 2025 Jimunendo Kinyū Gyōsei Hōshin [FSA strategic priorities: July 2025–June 2026]. Available online: https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r7/20250829/strategic_priorities_2025_main.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Japanese).

- Japan Study Group on Guidelines for Personal Guarantee Provided by Business Owners. (2013). Keieisha hoshō ni kansuru gaidorain [Guidelines for personal guarantee provided by business owners]. Available online: https://www.jcci.or.jp/file/chusho/202403/guideline_keiho.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025). (In Japanese).

- Jimenez, G., Salas, V., & Saurina, J. (2006). Determinants of collateral. Journal of Financial Economics, 81(2), 255–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Acharya, S., & Ho, L. T. H. (2020). Does monetary policy influence the profitability of banks in New Zealand? International Journal of Financial Studies, 8(2), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V., Thrikawala, S., & Acharya, S. (2022). Financial inclusion and bank profitability: Evidence from a developed market. Global Finance Journal, 53, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Feng, H., Zhao, S., & Carter, D. A. (2021). The effect of revenue diversification on bank profitability and risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters, 43, 101957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., & Wilson, J. O. S. (2010). The profitability of banks in Japan. Applied Financial Economics, 20(24), 1851–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzis, D. P., Vouldis, A. T., & Metaxas, V. L. (2012). Macroeconomic and bank-specific determinants of non-performing loans in Greece: A comparative study of mortgage, business and consumer loan portfolios. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(4), 1012–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manove, M., Padilla, A. J., & Pagano, M. (2001). Collateral versus project screening: A model of lazy banks. The Rand Journal of Economics, 32(4), 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehzabin, S., Shahriar, A., Hoque, M. N., Wanke, P., & Azad, M. A. K. (2023). The effect of capital structure, operating efficiency and non-interest income on bank profitability: New evidence from Asia. Asian Journal of Economics and Banking, 7(1), 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca, S., Schaeck, K., & Wolfe, S. (2007). Small European banks: Benefits from diversification? Journal of Banking & Finance, 31(7), 1975–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S., Peng, K., Wang, S., & Ashraf, B. (2018). The impact of revenue diversification on bank profitability and stability: Empirical evidence from South Asian countries. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(2), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, M. (2023). Bank-specific, industry-specific and macroeconomic determinants of bank profitability: Evidence from the UK. Studies in Economics and Finance, 40(1), 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A., Sakai, K., & Uesugi, I. (2012). The effects of collateral on firm performance. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26(1), 84–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, A., & Uesugi, I. (2009). Role of collateral and personal guarantees in relationship lending: Evidence from japan’s SME loan market. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 41(5), 935–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancotto, L., ap Gwilym, O., & Williams, J. (2024). The evolution and determinants of the non-performing loan burden in Italian banking. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 84, 102306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltoniemi, J., & Vieru, M. (2013). Personal guarantees, loan pricing, and lending structure in Finnish small business loans. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(2), 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podpiera, J., & Weill, L. (2008). Bad luck or bad management? Emerging banking market experience. Journal of Financial Stability, 4(2), 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009a). A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 71(1), 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. (2009b). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiroh, K. J., & Rumble, A. (2006). The dark side of diversification: The case of US financial holding companies. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30(8), 2131–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uesugi, I., Uchida, H., & Iwaki, H. (2018). Muhoshōnin kashidashi no dōnyū to kigyō no shikin chōtatsu pafōmansu (in Japanese) [Loans without personal guarantees and financing and performance of borrower firms]. Kin’yū Keizai Kenkyū [Review of Monetary and Financial Studies], 40, 1–25. Available online: https://www.jsmeweb.org/ja/journal/pdf/vol.40/full-paper-40jp-uesugi.uchida.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Yoshinaga, Y., & Onishi, K. (2025). Manually collected data on loans without personal guarantees from Japanese Banks [Data set]. Zenodo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Loan requirements of SMEs in Japan from 2004 to 2010. Note: This figure is based on the Basic Survey on Small and Medium Enterprises. It illustrates the percentage of companies with loans from their main bank that are subject to collateral or guarantees.

Figure 1.

Loan requirements of SMEs in Japan from 2004 to 2010. Note: This figure is based on the Basic Survey on Small and Medium Enterprises. It illustrates the percentage of companies with loans from their main bank that are subject to collateral or guarantees.

Figure 2.

The time-series distribution of . Note: This figure is based on the JFSA data and publications of regional banks. It illustrates the time-series distribution of the proportion of new loans without personal guarantees across the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles.

Figure 2.

The time-series distribution of . Note: This figure is based on the JFSA data and publications of regional banks. It illustrates the time-series distribution of the proportion of new loans without personal guarantees across the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles.

Figure 3.

Marginal effect of on bank profitability: fixed effect approach. Note: Panels (a–c) shows the estimated marginal effect of on , , and across selected percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th) of , based on Equation (2), respectively. Bold lines represent point estimates of the marginal effect. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals based on bank-clustered robust standard errors. The horizontal dashed line denotes zero effect.

Figure 3.

Marginal effect of on bank profitability: fixed effect approach. Note: Panels (a–c) shows the estimated marginal effect of on , , and across selected percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th) of , based on Equation (2), respectively. Bold lines represent point estimates of the marginal effect. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals based on bank-clustered robust standard errors. The horizontal dashed line denotes zero effect.

Figure 4.

Marginal effect of on bank profitability: GMM approach. Note: Panels (a–c) show the estimated marginal effect of on , , and across selected percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th) of , based on Equation (4), respectively. Bold lines represent point estimates of the marginal effect. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals based on Windmeijer-corrected robust standard errors. The horizontal dashed line denotes zero effect.

Figure 4.

Marginal effect of on bank profitability: GMM approach. Note: Panels (a–c) show the estimated marginal effect of on , , and across selected percentiles (10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 90th) of , based on Equation (4), respectively. Bold lines represent point estimates of the marginal effect. Shaded areas indicate 95% confidence intervals based on Windmeijer-corrected robust standard errors. The horizontal dashed line denotes zero effect.

Table 1.

Trends in domestic loans and deposits by type of financial institutions.

Table 1.

Trends in domestic loans and deposits by type of financial institutions.

| Panel A: Loans, average amounts outstanding |

| | Major banks | Regional banks | Shinkin-banks |

| Amounts | Share (%) | Amounts | Share (%) | Amounts | Share (%) |

| May 2000 | 291 | 53.4 | 185 | 33.9 | 69 | 12.7 |

| May 2005 | 206 | 46.9 | 172 | 39.2 | 61 | 13.9 |

| May 2010 | 203 | 44.2 | 193 | 42.1 | 63 | 13.6 |

| May 2015 | 203 | 41.8 | 220 | 45.2 | 63 | 13.0 |

| May 2020 | 232 | 41.2 | 259 | 46.2 | 71 | 12.6 |

| May 2025 | 253 | 39.9 | 303 | 47.8 | 78 | 12.3 |

| Panel B: Deposits, average amounts outstanding |

| | City banks | Regional banks | Shinkin-banks |

| Amounts | Share (%) | Amounts | Share (%) | Amounts | Share (%) |

| May 2000 | 235 | 41.2 | 234 | 40.9 | 102 | 17.9 |

| May 2005 | 256 | 42.2 | 243 | 40.0 | 108 | 17.8 |

| May 2010 | 275 | 41.5 | 269 | 40.7 | 118 | 17.8 |

| May 2015 | 317 | 41.4 | 316 | 41.3 | 132 | 17.3 |

| May 2020 | 416 | 45.3 | 356 | 38.7 | 147 | 16.0 |

| May 2025 | 484 | 45.7 | 414 | 39.0 | 162 | 15.3 |

Table 2.

The number of financial institutions.

Table 2.

The number of financial institutions.

| | City Banks | Regional Banks | Shinkin Banks |

|---|

| FY 1995 | 11 (+0.0%) | 129 (+0.0%) | 416 (+0.0%) |

| FY 2000 | 9 (−18.2%) | 121 (−6.2%) | 372 (−10.6%) |

| FY 2005 | 6 (−45.5%) | 111 (−14.0%) | 292 (−29.8%) |

| FY 2010 | 6 (−45.5%) | 105 (−18.6%) | 271 (−34.9%) |

| FY 2015 | 5 (−54.5%) | 105 (−18.6%) | 265 (−36.3%) |

| FY 2020 | 5 (−54.5%) | 100 (−22.5%) | 254 (−38.9%) |

| January 2025 | 5 (−54.5%) | 97 (−24.8%) | 254 (−38.9%) |

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

| | Mean | SD | Min | 25% | Median | 75% | Max | N |

|---|

| 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.028 | 352 |

| 0.002 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 352 |

| 0.032 | 0.018 | −0.074 | 0.023 | 0.033 | 0.041 | 0.075 | 352 |

| 0.388 | 0.136 | 0.148 | 0.284 | 0.362 | 0.468 | 0.784 | 352 |

| 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.099 | 352 |

| 14.987 | 0.985 | 12.523 | 14.239 | 15.074 | 15.750 | 16.865 | 352 |

| 0.837 | 0.088 | 0.632 | 0.776 | 0.838 | 0.883 | 1.205 | 352 |

| 0.047 | 0.011 | 0.025 | 0.041 | 0.046 | 0.053 | 0.083 | 352 |

| 0.541 | 0.109 | 0.326 | 0.458 | 0.532 | 0.621 | 0.790 | 352 |

| 0.064 | 0.080 | −0.134 | 0.014 | 0.045 | 0.090 | 0.345 | 253 |

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix.

| | | | | | | | | | |

| | 0.038 | −0.048 | −0.036 | 0.308 | −0.668 | 0.242 | 0.214 | 0.646 |

| 0.089 | | 0.788 | 0.108 | −0.194 | 0.337 | −0.912 | 0.455 | −0.158 |

| −0.004 | 0.831 | | 0.191 | −0.124 | 0.338 | −0.785 | −0.014 | −0.077 |

| 0.028 | 0.143 | 0.215 | | −0.103 | 0.094 | −0.122 | −0.091 | −0.029 |

| 0.586 | −0.079 | −0.044 | −0.048 | | −0.443 | 0.287 | −0.057 | 0.153 |

| −0.645 | 0.309 | 0.297 | 0.097 | −0.433 | | −0.533 | −0.019 | −0.591 |

| 0.165 | −0.924 | −0.840 | −0.142 | 0.206 | −0.474 | | −0.290 | 0.215 |

| 0.242 | 0.461 | 0.035 | −0.075 | 0.054 | 0.004 | −0.313 | | −0.079 |

| 0.674 | −0.119 | −0.075 | −0.001 | 0.300 | −0.614 | 0.186 | −0.070 | |

Table 5.

Loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: fixed effect approach.

Table 5.

Loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: fixed effect approach.

| | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|

| | | | |

| −0.011 | −0.008 | 0.019 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.401 * | 0.394 * |

| | (0.012) | (0.009) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.231) | (0.232) |

| 0.002 * | 0.005 *** | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.003 |

| | (0.001) | (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.008) | (0.014) |

| 0.002 | 0.079 *** | −0.017 | −0.003 | −0.268 | −0.427 |

| | (0.018) | (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.015) | (0.210) | (0.389) |

| | −0.186 *** | | −0.033 | | 0.386 |

| | (0.055) | | (0.027) | | (0.680) |

| 0.001 * | 0.001 * | −0.000 ** | −0.000 ** | −0.011 | −0.010 |

| | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.015) | (0.015) |

| 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** | −0.212 *** | −0.212 *** |

| | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.016) | (0.016) |

| 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.011 | 0.011 | −0.290 | −0.281 |

| | (0.019) | (0.019) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.188) | (0.189) |

| 0.004 * | 0.005 ** | −0.002 *** | −0.002 *** | −0.028 | −0.029 * |

| | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.017) | (0.017) |

| 0.951 | 0.954 | 0.955 | 0.956 | 0.852 | 0.852 |

| 352 | 352 | 352 | 352 | 352 | 352 |

| Year fixed | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| Bank fixed | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

Table 6.

Marginal effect of loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: fixed effect approach.

Table 6.

Marginal effect of loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: fixed effect approach.

| Panel A Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | 0.003 *** | (0.001) |

| 25th | 0.014 | 0.002 ** | (0.001) |

| 50th | 0.018 | 0.002 * | (0.001) |

| 75th | 0.023 | 0.001 | (0.001) |

| 90th | 0.028 | −0.000 | (0.001) |

| Panel B Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | 0.000 | (0.000) |

| 25th | 0.014 | 0.000 | (0.000) |

| 50th | 0.018 | 0.000 | (0.000) |

| 75th | 0.023 | 0.000 | (0.000) |

| 90th | 0.028 | −0.000 | (0.000) |

| Panel C Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | 0.008 | (0.009) |

| 25th | 0.014 | 0.009 | (0.008) |

| 50th | 0.018 | 0.010 | (0.008) |

| 75th | 0.023 | 0.012 | (0.010) |

| 90th | 0.028 | 0.014 | (0.012) |

Table 7.

Loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: GMM approach.

Table 7.

Loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: GMM approach.

| | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|

| | | | |

| −0.011 | −0.011 | 0.027 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.515 *** | 0.463 *** |

| | (0.018) | (0.015) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.125) | (0.170) |

| 1.209 *** | 1.109 *** | | | | |

| | (0.374) | (0.261) | | | | |

| | | −0.042 | −0.053 | | |

| | | | (0.051) | (0.057) | | |

| | | | | −0.057 | −0.045 |

| | | | | | (0.048) | (0.061) |

| 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.047 |

| | (0.004) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.040) | (0.033) |

| −0.014 | −0.001 | −0.024 | 0.015 | −0.376 | 0.337 |

| | (0.040) | (0.086) | (0.023) | (0.035) | (0.534) | (1.008) |

| | −0.061 | | −0.047 | | −0.573 |

| | (0.180) | | (0.074) | | (2.250) |

| 0.001 | 0.000 | −0.001 ** | −0.001 ** | −0.012 *** | −0.010 * |

| | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.006) |

| 0.003 | 0.004 | −0.016 *** | −0.015 *** | −0.268 *** | −0.276 *** |

| | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.002) | (0.004) | (0.045) | (0.081) |

| −0.002 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.004 | −0.799 *** | −0.807 *** |

| | (0.039) | (0.043) | (0.018) | (0.019) | (0.230) | (0.240) |

| −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.004 * | −0.003 * | −0.090 * | −0.065 |

| | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.048) | (0.040) |

| Year dummy | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included | Included |

| N of obs | 253 | 253 | 253 | 253 | 253 | 253 |

| N of group | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 | 79 |

| N of inst | 18 | 20 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 20 |

| Hansen p | 0.385 | 0.238 | 0.128 | 0.071 | 0.501 | 0.326 |

| AR(1) p | 0.396 | 0.387 | 0.159 | 0.254 | 0.018 | 0.120 |

| AR(2) p | 0.425 | 0.383 | 0.678 | 0.489 | 0.886 | 0.851 |

Table 8.

Marginal effect of loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: GMM approach.

Table 8.

Marginal effect of loans without personal guarantee and bank profitability: GMM approach.

| Panel A Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | −0.001 | (0.003) |

| 25th | 0.014 | −0.001 | (0.003) |

| 50th | 0.018 | −0.002 | (0.004) |

| 75th | 0.023 | −0.002 | (0.004) |

| 90th | 0.028 | −0.002 | (0.005) |

| Panel B Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | 0.001 | (0.001) |

| 25th | 0.014 | 0.001 | (0.001) |

| 50th | 0.018 | 0.001 | (0.001) |

| 75th | 0.023 | 0.001 | (0.002) |

| 90th | 0.028 | 0.000 | (0.002) |

| Panel C Marginal effect of on for various levels of |

| percentiles | level | marginal effect | standard errors |

| 10th | 0.012 | 0.041 | (0.041) |

| 25th | 0.014 | 0.039 | (0.044) |

| 50th | 0.018 | 0.037 | (0.051) |

| 75th | 0.023 | 0.034 | (0.060) |

| 90th | 0.028 | 0.031 | (0.069) |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).