Abstract

Feldstein and Horioka in 1980 estimated (I/GDP)i = α + β(S/GDP)i where “i” is for a given country over time, “I” is domestic investment, and “S” is domestic savings. Feldstein and Horioka found βs that were insignificantly different from one and significantly different from zero. According to Feldstein and Horioka, these results conflict with an assumption of perfect capital mobility because, if capital were perfectly mobile, then β should be zero. We estimated (I/GDP)it = α + β(S/GDP)it using data from 22 countries from 1970 to 2023, where i denotes the country and t denotes the year. We found βs to be significantly less than 1 but greater than 0. We then used Reiterative Truncated Projected Least Squares, which was designed to solve the omitted variable problem (and helps a researcher visualize the effects of heteroscedasticity), to estimate a βit for every observation. We find that βit decreases for countries that export capital and increases for countries that import capital. We argue that the Feldstein-Horioka “puzzle” is based on a confusion—when the effect of both exporting and importing capital is considered, β should equal approximately one. Feldstein and Horioka focus on single countries, but when pairs of savings exporters and importers are considered, their “puzzle” disappears. However, the fact that βit is now much less than 1 and falling over time suggests that a global glut of savings is worsening.

1. Introduction

Economists want to believe that markets work perfectly. It took the Great Depression, during which unemployment rates rose to twenty-five percent, to convince some economists to consider the possibility that labor markets might not work perfectly. Then, in 1980, Feldstein and Horioka argued that the international capital market must not work perfectly, as evidenced by the strong correlation between a country’s investment (as a percent of GDP) and domestic savings (as a percent of GDP). Unwilling to accept the conclusion that international capital markets do not operate perfectly, the economics profession labeled the Feldstein–Horioka result “one of economics’ greatest puzzles.”

Apergis and Tsoumas (2009) and Coakley et al. (1998) surveyed the extensive literature responding to Feldstein and Horioka (1980). These surveys showed that (1) the correlation that Feldstein and Horioka (1980) found between a country’s investments and savings is exceptionally robust, (2) proposed “solutions” to the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle tried to explain how capital can be perfectly mobile while domestic savings and investment are highly correlated, and (3) the Feldstein and Horioka (1980) result was due to the use of an inappropriate theoretical model or statistical technique.

This paper relates to these three points as follows. Like the first point, this paper finds that there continues to be a strong correlation between domestic savings and domestic investment as percentages of GDP; however, we find that the value for d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) has fallen over time for almost all the countries studied. This general fall in d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) suggests the existence of a global glut of savings.

Some scholars, who have proposed solutions to the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle (the second point), argue that frictions in the international market for goods and services (transport costs, tariffs, quotas, costs of regulatory compliance, etc.) can explain the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle (Horioka, 2024; Ford & Horioka, 2017). If these scholars are correct, then one would expect that the correlation between domestic savings and investment would be weaker for countries in a common market like the eurozone. Contrary to this expectation, this paper finds that the correlation between domestic savings and domestic investment (as percentages of GDP) is not notably different between euro-using and non-euro-using countries after 1999 when the euro was established.

Consider the third point that the model or statistical technique used by Feldstein and Horioka (1980) was inappropriate. In a different context, Cogan et al. (2010) shows that applying different Keynesian models to the same set of data produces extremely different results. However, Feldstein and Horioka (1980) did not use a specific model; instead, they simply regressed the ratio of investment to GDP on the ratio of savings to GDP. Feldstein and Horioka’s (1980) approach has been criticized for omitted-variable bias, simultaneous-equation bias, and for not testing for cointegration and unit roots (Coakley et al., 1998). This paper is not subject to these criticisms because we use reiterative truncated projected least squares (RTPLS), which was designed to solve the omitted variable problem of regression analysis. RTPLS produce a unique total derivative estimate for each observation, where differences in these total derivative estimates are due to omitted variables. Furthermore, RTPLS is not model-dependent. Moreover, since RTPLS estimates are total derivatives, simultaneous equation bias is not a problem. RTPLS estimates help a researcher visualize the effects of heteroskedasticity.

2. Statistical Technique Used

Reiterative truncated projected least squares (RTPLS), a statistical technique designed to solve the omitted variables problem of regression analysis, was used to generate the estimates of this paper. In Equations (1)–(3), the αs and βs are coefficients to be estimated, X is the known independent variable, Y is the dependent variable, q represents the combined influence of all omitted variables, and u is random error. If only Equation (1) is estimated by itself, thus ignoring Equation (2), the resulting estimate of β1 is a constant when in truth β1 varies with qi. This constitutes an “omitted variable” problem (Leightner, 2015; Leightner et al., 2021).

Yt = α0 + β1Xt + u

β1 = α1 + α2qt

One way to incorporate the influence of omitted variables (q) on β1 is to substitute Equation (2) into Equation (1) to create Equation (3).

Yt = α0 + α1Xt + α2 Xt qt + ut.

Equation (7) can be derived from Equation (3) as shown below (Leightner, 2015).

(dYt/dXt)True = α1 + α2qt Derivative of (3)

Yt/Xt = α0/Xt + α1 + α2qt + ut/Xt (3) divided by X

α1 + α2qt = Yt/Xt − α0/Xt − ut/Xt (5) rearranged

(dYt/dXt)True = Yt/Xt − α0/Xt − ut/Xt From (4) and (6)

Once an estimate for α0 is found, it can be used to calculate a unique slope estimate for each observation using Equation (8).

(dYt/dXt)^ = Yt/Xt − α0^/Xt

The slope estimate for one observation would differ from the slope estimates of other observations because different observations are associated with different values of the omitted variables (q) which in turn affect β1 (Equation (2)). Equation (9) shows the error due to using Equation (8) to calculate β1.

(dYt/dXt)True − (dYt/dXt)^ = (α0^ − α0)/Xt − ut/Xt From (7) and (8)

In Equation (9), the ut/Xt term will usually be extremely small because random error (ut) is usually tiny relative to the size of Xt, making ut/Xt even smaller (if Xt > zero). Thus, the accuracy of using Equation (8) to calculate a separate slope estimate for each observation depends primarily on the accuracy of the α0 estimate.

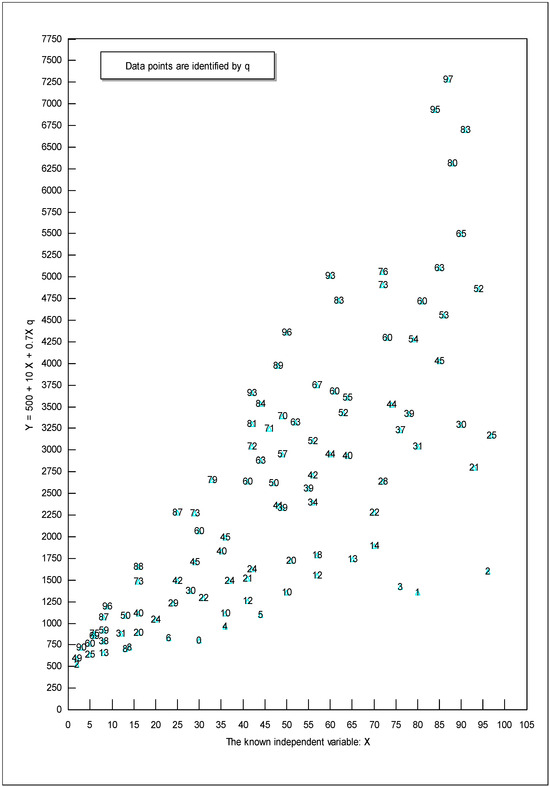

The easiest way to explain the intuition behind RTPLS is to use a diagram like Figure 1 (see next page). To construct Figure 1, we generated two series of random numbers, X and q, which ranged from 0 to 100 (for increased clarity, in this example, we set ut = 0). We then calculated the dependent variable Y = 500 + 10 X + 0.7 q X.

Figure 1.

The intuition behind RTPLS.

The true value for dY/dX equals 10 + 0.7 q. Since q ranges from 0 to 100, the true slope will range from 10 (when q = 0) to 80 (when q = 100). Thus, q makes an 800 percent difference to the slope. In Figure 1, we identified each point with that observation’s value for q. Notice that the upper edge of the data corresponds to relatively large qs—90, 96, 96, and 97. The lower edge of the data corresponds to relatively small qs—2, 0, 1, and 2. This makes sense since Y increases as q increases for any given X. For example, when X approximately equals 8, reading the values of q from top to bottom of Figure 1 produces 96, 87, 59, 38, and 13. Likewise, when X is approximately 42, the values for q, reading from the top to the bottom, are 93, 81, 72, 60, 21, and 12. Thus, the relative vertical position of each observation is directly related to the values of q. If, instead of adding 0.7 qX in Equation (3), we had subtracted 0.7 qX, the smallest qs would be on the top and the largest qs on the bottom of Figure 1. Either way, the relative vertical position of observations captures the influence of q. In Figure 1, the true value for dY/dX equals 10 + 0.7 q; thus, the slope, dY/dX, will be at its greatest numerical value along the upper edge of the data where q is largest, and the slope will be at its smallest numerical value along the bottom edge of the data where q is smallest.

Now imagine that you do not know what q is and that you have to omit it from your analysis. In this case, OLS produces the following estimated equation: Y = 468.43 + 43.57X with an R-squared of 0.564 and a standard error of the slope of 3.87. On the surface, this OLS regression looks successful, but it is not. Remember that the true equation is Y = 500 + 10 X + 0.7 q X. Since q ranges from 0 to 100, the true slope (true derivative) ranges from 10 to 80, and OLS produced a constant slope of 43.57. OLS did the best it could, given its assumption of a constant slope; OLS produced a slope estimate of approximately 10 + 0.7E(q) = 10 + 0.7(46.79) = 42.75 (where “E(q)” is the expected, or mean value, for q), which is close to the estimated 43.57. However, OLS is hopelessly biased by its assumption of a constant slope when, in truth, the slope is varying.

Although OLS is hopelessly biased when there are omitted variables that interact with the included variables, Figure 1 provides an important insight—even when researchers do not know what the omitted variables are, even when they have no clue how to model the omitted variables or measure the omitted variables, and even when there are no proxies for the omitted variables, Figure 1 shows researchers that the relative vertical position of each observation contains information about the combined influence of all omitted variables on the true slope. For example, if there are 400 omitted variables that increase Y and 500 that decrease Y, the observations that are on the upper frontier will correspond to when the 400 omitted variables are at their highest levels and the 500 at their lowest.

Reiterative Truncated Projected Least Squares (RTPLS) produce separate slope estimates for layers of the data by peeling the data down layer by layer and then peeling the data up, after which Equation (10) is used with the resulting layer slopes ((dYt/dXt)^) to estimate α0.

(dYt/dXt)^ − Yt/Xt = − α0^/Xt (8) rearranged

Leightner (2015) explains the math that underlies RTPLS. The first peeling down layer is constructed by drawing a line between all the points on the upper left side of the data. For Figure 1, this line would connect the upper points identified with qs of 90, 96, 96, and 97. This line would go horizontal after the topmost 97. The rest of the data is then projected to this line, the upper right-hand horizontal part of the line is then truncated off, and an OLS regression is run through the remaining points to produce a dY/dX estimate when the omitted variables are at their most favorable (highest level of Y). The points that determined that layer are then deleted, and the next layer is estimated. This process is repeated until there are fewer than 10 observations left. Each layer has no thickness, but the gap between each layer would vary in thickness as determined by the position of observations.

Once the data has been peeled down, the process starts over and peels the data upwards from the bottom. The first peeling up layer for Figure 1 would draw a line between the lower right points identified with q values of 2, 0, 1, and 2. The rest of the data is projected to this line, any vertical section of the line is truncated off, and an OLS regression is run to determine a dY/dX estimate when the omitted variables are at their least favorable (lowest level of Y). The slope estimates from peeling both down and up are then used, along with the values for X and Y, to estimate an α0 (via Equation (10)), which is then plugged into Equation (8) to calculate a separate slope estimate for each observation.

When Equation (1) is estimated using OLS, while ignoring the omitted variables problem created by Equation (2), the resulting estimate for β1 is approximately α1+ α2E[qt], which leaves an “error” for the t = ith observation of approximately α2Xi(qi − E[qi]) + ui (Leightner et al., 2021). RTPLS is better than ignoring the omitted variables problem if |(α0^ − α0)/Xi − ui/Xi| from Equation (9) is less than |α2{qi − E[qi]}|.

RTPLS imposes no restrictions on q: q can represent forces that affect the slope in a continuous or discontinuous fashion, in a linear or log-linear way, in a simple or complex manner, or in any other way. Moreover, q represents the combined influence on the slope of all omitted variables, where some omitted variables could be positively related, some negatively related, some squared, some quadrupled, some logged, etc. What is essential for these methods (as it is for standard regression analysis) is that the relationship between the known independent variable (X) and the dependent variable (Y) must be correctly modeled. However, the omitted variables (q) do not need to be modeled.

RTPLS utilizes strategies that underlie Two Stage Least Squares (2SLS) and Instrumental Variable Estimation (IV). 2SLS regresses the dependent variable on all exogenous variables, then plugs the data into the resulting equation to calculate the modified dependent variable used in the second stage estimation. This process purges the dependent variable of any variation not explained by the exogenous variables. Likewise, when RTPLS projects all the remaining data to a given layer, RTPLS is purging from the data the influence of less favorable omitted variables to produce a layer that corresponds to the most favorable omitted variables values.

RTPLS uses an “instrumental variable” estimation strategy where the instrument is the relative vertical position of observations. To correctly use IV estimation, the researcher needs to find an instrument that is strongly correlated to the omitted variable, correctly model how the omitted variable is related to the dependent variable and how the instrument is related to the omitted variable and use an instrument that does not have an independent influence on the dependent variable. This last condition is not testable (Labrecque & Swanson, 2018). However, since the relative vertical position of observations is solely determined by omitted variables and by random error, it would have no independent effect on the dependent variable. The relative vertical position of observations is an ideal instrument for capturing the combined influence of all omitted variables.

Leightner et al. (2021) test RTPLS using simulations. They ran sets of 5000 simulations each for the 27 combinations of 500 observations, 250 observations, and 100 observations with the omitted variable making a 1000 percent difference to the slope, a 100 percent difference to the slope, and a 10 percent difference to the slope, and with random error being ten percent, one percent, and zero percent of the variation in the independent variable. RTPLS outperformed using OLS while ignoring the omitted variables problem, except for the case where the omitted variable makes only a ten percent difference to the slope, and random error is ten percent. When the importance of the omitted variable was 100 times as big as the random error, using OLS while ignoring omitted variables produced approximately 35 times the error of RTPLS. When the importance of the omitted variable was 10 times as big as the random error, using OLS while ignoring omitted variables produced approximately 3.8 times the error of RTPLS.

The central limit theorem can be used to create confidence intervals for RTPLS estimates.

Confidence interval = mean ± (s/√n)tn−1, α/2

In Equation (11), ‘s’ is the standard deviation, ‘n’ is the number of observations, and tn−1, α/2 is taken off the standard t table for the desired level of confidence. Leightner et al. (2021) used an estimate along with the 4 estimates before it to create a moving 95% confidence interval (much like a moving average) for a given set of RTPLS estimates. This confidence interval means that there is only a five percent chance that the next RTPLS estimate will lie outside of this range if omitted variables maintain the same amount of variability that they recently have.

RTPLS produces total derivative estimates, not partial derivative estimates. Traditional regression analysis produces partial derivatives that show how the dependent variable (Y) is affected by each independent variable (X) while holding all other included independent variables constant. RTPLS produces total derivative estimates that capture all the ways that the dependent and independent variables are related, holding nothing else constant. Therefore, RTPLS estimates are not substitutes for traditional regression estimates; instead, RTPLS estimates are complements of traditional estimates in that these methods produce different sets of useful information. One of the major advantages of RTPLS applied to time series or panel data is that RTPLS estimates can be plotted over time to show how omitted variables have affected the estimated relationship over time.

3. The Data

Feldstein and Horioka (1980) used data from 1960 to 1974 for the following 16 countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, the UK, and the USA. The data for our paper was from 1970 to 2023 for the same list of countries minus Greece plus Israel, Korea, Mexico, Portugal, Spain, Singapore, and South Africa. Our paper used data from all countries listed in the OECD data website that had the required data that started no later than 1970. Thus, we included Singapore and South Africa even though they are not OECD countries.

The OECD data website clearly indicated which numbers were estimates, which were preliminary, and which were final numbers. No numbers were provided for 2023 for New Zealand and Japan. The numbers for Germany were preliminary for 2020 to 2023, and for New Zealand for 2022. The numbers given for 2023 were preliminary for Belgium, Korea, the Netherlands, and Portugal. The numbers provided for 1970 to 1994 were labeled as “estimates” for Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, and Portugal. The numbers for Ireland, Spain, and the UK were listed as estimates for 1970 to 1998. OECD’s numbers were estimates for Canada from 1970 to 1980, for Japan from 1970 to 1993, for Korea from 1970 to 1999, for Mexico from 1970 to 2002, for New Zealand in 1970, and for Sweden from 1970 to 1992. Belgium was listed as having a change in accounting methods in 2009, but a plot over time of the numbers needed for this study before 2009 looks consistent with the numbers needed after 2009.

Table 1 provides the means and standard deviations for the data used in this study divided between before 1999 and after 1999. We split the data into these two time frames because the euro was established in 1999, and the freer capital and trade that supposedly came with the euro might affect our results. The top half of Table 1 presents mean values, and the bottom half presents standard deviations.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for the Data.

The OECD data website lists net domestic savings, gross fixed capital formation (hereafter called investment), and depreciation. Depreciation was added to net domestic savings to calculate gross domestic savings. Depreciation was subtracted from gross fixed capital formation to calculate net domestic investment. For Singapore, the OECD data website provided data on gross savings (instead of net savings) and did not provide data on depreciation; this limited the Singapore analysis to only gross investment versus gross savings.

Table 1 reveals that the mean (net Savings)/GDP fell between before 1999 and after 1999 for the non-euro-using group by 25.5 percent ((0.0648–0.0870)/0.0870) and for the euro-using group by 29.2 percent. Meanwhile, (net Investment)/GDP fell by 39.3 percent for the non-euro-using group and for the euro-using group by 47.3 percent. All of these declines are statistically significant at a 99 percent confidence level using a two sample t test. Net investment as a percent of GDP is falling for both groups much faster than net savings as a percent of GDP. This asymmetry between the fall in savings and investment could be the result of a worsening global glut of savings. Similarly, (gross savings)/GDP rose by 0.08 percent for non-euro-using countries and fell by 0.02 percent for euro-using countries between before 1999 and after 1999. However, (gross investment)/GDP fell by 12.3 percent for non-euro-using countries and by 8.97 percent for euro-using countries.

4. The Results

Feldstein and Horioka (1980) produced the estimates shown in Equation (12) where “i” is for a given country, “I” is domestic investment, “S” is domestic savings, and “GDP” is Gross Domestic Product. The numbers in parentheses below the estimates are standard errors for those estimates.

((net I)/GDP)i = 0.017 + 0.938((net S)/GDP)i

(0.014) (0.091)

((gross I)/GDP)i = 0.035 + 0.887((gross S)/GDP)i

(0.018) (0.074)

(0.014) (0.091)

((gross I)/GDP)i = 0.035 + 0.887((gross S)/GDP)i

(0.018) (0.074)

Feldstein and Horioka (1980) averaged a given country’s I/GDP and S/GDP over time. Neither of Feldstein and Horioka’s βs (0.938 and 0.887) were significantly different from one, and both were significantly greater than zero. According to Feldstein and Horioka (1980) these results conflict with an assumption of perfect capital mobility because, if capital were perfectly mobile, then β should be zero.

We will show below that several countries experienced large inflows and then outflows of foreign capital during the time interval we studied. Taking average values over time (like Feldstein and Horioka did) would eliminate some very interesting results over time. Thus, we produced the estimates shown in Equation (13) where the “i” is for a given country and the “t” is for a different year.

((net I)/GDP)it = 0.0282 + 0.717((net S)/GDP)it

(0.0378) (0.0213)

((gross I)/GDP)it = 0.124 + 0.498((gross S)/GDP)it

(0.040) (0.017)

(0.0378) (0.0213)

((gross I)/GDP)it = 0.124 + 0.498((gross S)/GDP)it

(0.040) (0.017)

Both of our estimates for β (0.717 and 0.498) are significantly different from both zero and one.

The estimates reported in Equations (12) and (13) can be criticized for omitted variable bias. To avoid this criticism, we will estimate Equation (14) using Reiterative Truncated Projected Least Squares (RTPLS), which produced estimates of βit that capture the influence of omitted variables.

(I/GDP)it = α + βit(S/GDP)it

However, before turning to RTPLS, we test the robustness of our estimates in Equation (13) using the System GMM estimator (Arellano & Bover, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998; Roodman, 2009; Holtz-Eakin et al., 1988; Arellano & Bond, 1991). The System GMM framework accounts for the dynamic nature of investment by including the lagged dependent variable and addresses potential endogeneity between savings and investment through internally generated instruments. The System GMM estimates are presented in Equation (15).1

((net I)/GDP)it = 0.716(net I/GDP)it-1 + 0.424((net S)/GDP)it

(0.064) (0.094)

((gross I)/GDP)it = 0.861(gross I/GDP)it-1 + 0.221((gross S)/GDP)it

(0.060) (0.053)

(0.064) (0.094)

((gross I)/GDP)it = 0.861(gross I/GDP)it-1 + 0.221((gross S)/GDP)it

(0.060) (0.053)

The estimation was implemented in STATA using the xtabond2 command with a two-step system GMM estimator, collapsed instruments, and lag windows chosen to satisfy diagnostic criteria. Both coefficients on the lagged investment percentages are large and statistically significant, indicating strong persistence in investment percentages. The coefficients on savings percentages are positive and significant but lower than those shown in Equations (12) and (13), suggesting that while domestic savings still matter, their explanatory power is weaker once dynamic adjustment and endogeneity are taken into account.

Several scholars have argued that friction in the international market for goods and services (tariffs, quotas, transport costs, regulatory compliance costs, etc.) can explain the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle even if capital is perfectly mobile (Horioka, 2024; Ford & Horioka, 2017). If these scholars are correct, then capital should be much more mobile between countries that face no exchange rate risk, no tariffs, no quotas, and that allow the free movement of factors of production (including capital); all of which are supposedly true for the euro-using countries since 1999.

To investigate whether monetary integration altered the savings–investment relationship, we re-estimated the System GMM model separately for euro-using and non-euro-using countries, dividing the sample into pre- and post-1999 periods. This approach captures the structural break associated with the introduction of the euro, which eliminated exchange-rate risk and facilitated the free movement of goods, services, and capital within the eurozone. The eurozone subsamples capture changes associated with the introduction of the euro, while the non-euro group serves as a benchmark.

Table 2 reports two-step System GMM estimates of the investment equation, with lagged net investment percent and net savings percent as regressors. Across all models, the lagged investment term remains highly significant and close to 0.7–0.75, confirming strong persistence in investment behavior. The coefficient on the savings percent is positive and significant in the pre-euro period, indicating a tight domestic savings–investment link before monetary union. After 1999, this coefficient declined markedly, especially within the eurozone sample (from 0.35 to 0.19), suggesting that greater financial integration and capital mobility weakened the domestic relationship between savings and investment.

Table 2.

System GMM Estimates for Sub-Periods2.

The System GMM estimates complement the descriptive evidence by confirming a weakening of the savings–investment link. As Table 1 shows, in euro-using countries, average net savings as a percent of GDP declined by about 29% between 1970–1998 and 1999–2023, while net investment as a percent of GDP fell more sharply by 47%. The GMM results indicate that this relationship also weakened dynamically, consistent with the observed data. Non-euro countries exhibit smaller but parallel declines.

Overall, the System GMM results reinforce the conclusion that the domestic savings–investment link has weakened over time, particularly within the eurozone after monetary integration. Both the lagged investment and savings coefficients remain significantly greater than zero, indicating persistent adjustment dynamics and a continuing, though diminished, role for domestic savings in financing investment. By accounting for dynamic adjustment and endogeneity, the GMM framework provides robust evidence that greater capital mobility and financial integration, rather than merely lower savings or investment levels, help explain the decline in the Feldstein–Horioka correlation for the euro-using countries.

While the System GMM approach addresses dynamic endogeneity, it assumes homogeneous slope coefficients across countries. To capture potential heterogeneity and further mitigate omitted-variable bias, we next employ the Reiterative Truncated Projected Least Squares (RTPLS) method and present the corresponding estimates for Equation (14).

Recall from Section 2 that we show that the true value for βit can be calculated as (dY/dX)itTrue = (Y/X)it − α0/Xit − uit/Xit. (Equation (7)). RTPLS produces an estimate of this true β as (dY/dXt)it^ = (Y/X)it − α0^/Xit (Equation (8)). The RTPLS estimates for Equation (8) are given in Equation (16).

Net: βit = {[(net I)/GDP] ÷ [(net S)/GDP]}it − {0.0708 ÷ [(net S)/GDP]it}

Gross: βit = {[(gross I)/GDP] ÷ [(gross S)/GDP]}it − {0.1321 ÷ [(gross S)/GDP]it}

Gross: βit = {[(gross I)/GDP] ÷ [(gross S)/GDP]}it − {0.1321 ÷ [(gross S)/GDP]it}

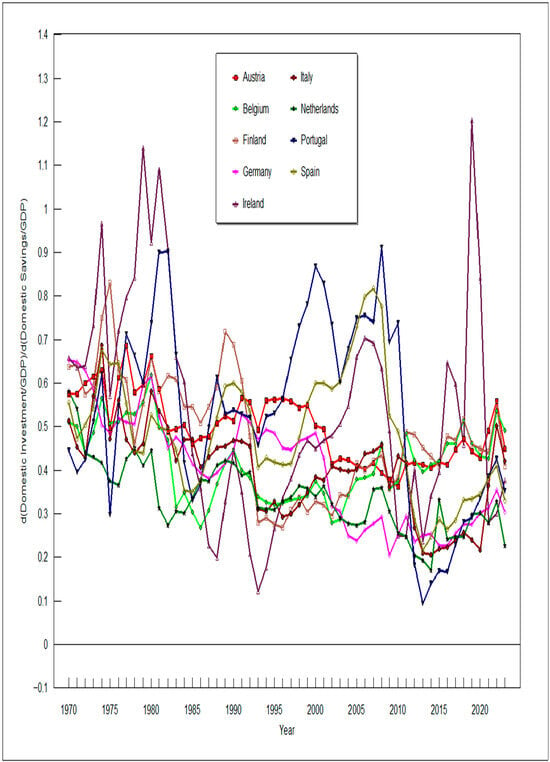

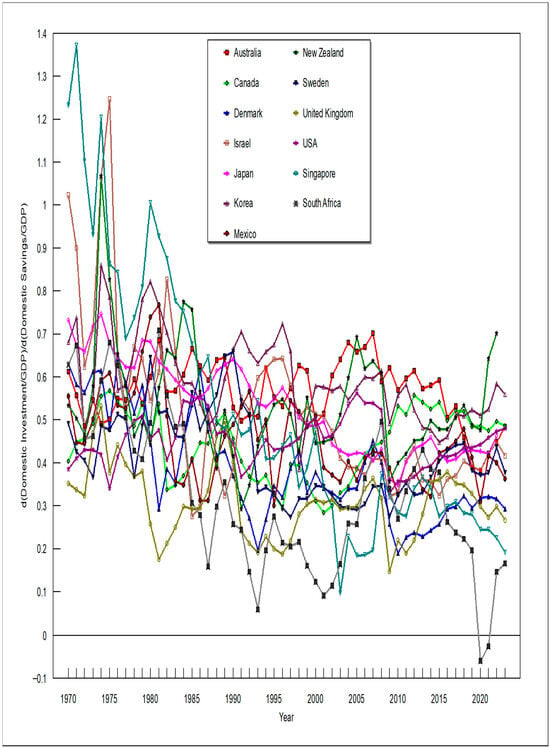

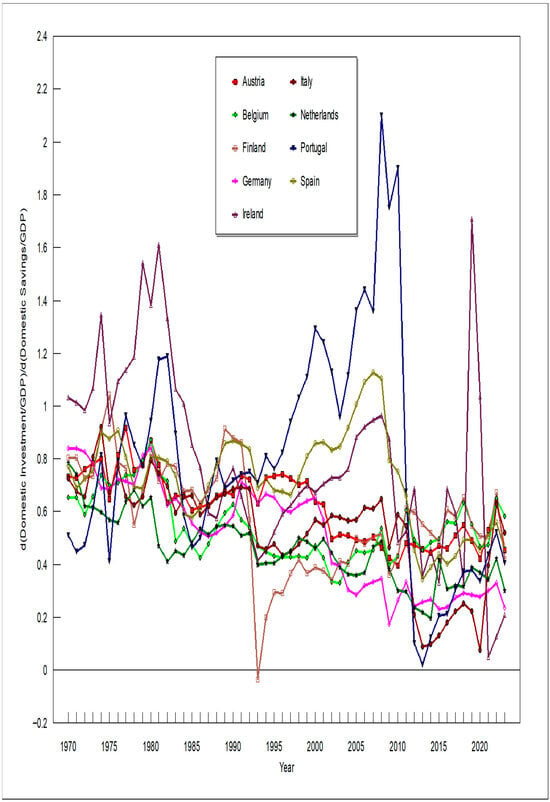

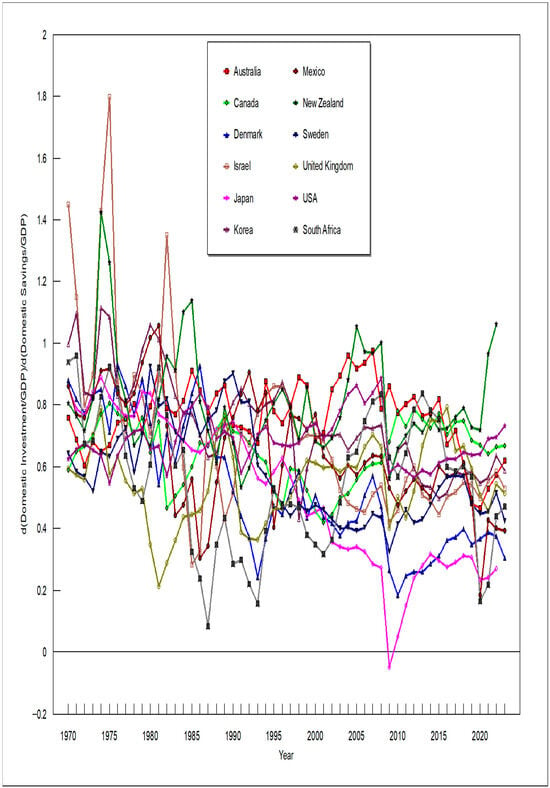

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 depict how the RTPLS estimates for β have evolved over time. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the results when gross investment and gross savings are used, and Figure 4 and Figure 5 show the results when net investment and net savings are used. Figure 2 and Figure 4 are for the euro-using countries, and Figure 3 and Figure 5 are for the non-euro-using countries. Any reader can reproduce the relationships depicted in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 merely by plugging the appropriate data into Equation (16). Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 show that, on average, β has fallen over time.

Figure 2.

d(Gross Domestic Investment)/d(Gross Domestic Savings) for euro-using countries.

Figure 3.

d(Gross Domestic Investment)/d(Gross Domestic Savings) for non-euro-using countries.

Figure 4.

d(Net Domestic Investment)/d(Net Domestic Savings) for euro-using countries.

Figure 5.

d(Net Domestic Investment)/d(Net Domestic Savings) for non-euro-using countries.

Confidence intervals can be created for RTPLS estimates using Equation (11). The RTPLS estimates for β, [d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP)], remained significantly greater than zero except for South Africa between 2021 and 2023 when gross investment and gross savings were used and Finland in 1995, Ireland in 2022–2023, Japan 2010–2013, and Portugal 2013–2016 when net investment and net savings were used. Even after correcting for omitted-variable bias, the vast majority of the estimated βs are statistically greater than zero but less than one. According to Feldstein and Horioka (1980) this implies that capital is still not perfectly mobile.

At the very least, those who argue that trade restrictions explain the Feldstein and Horioka puzzle (e.g., Horioka, 2024; Ford & Horioka, 2017) would expect RTPLS to show a noticeable change in β for euro-using countries before 1999 (when the euro was first used for accounting purposes) and after 2002 (when the euro was used for all internal transactions). However, the most noticeable change in the βs that occurred around the 1999 to 2002 time period for the Eurozone is not a fall in their values; the most noticeable change is that the variance of the different βs between different euro-using countries increased after 1999.

Perhaps the European Union is a “myth” as claimed by Ip (2025). Indeed, Ip (2025) notes that Europe does not have large cross-continent banks that can facilitate the transfer of capital across all of Europe (in contrast to the USA, which has 4 dominating banks). Ip (2025) makes some valid points. However, if the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle is correctly conceptualized, then one would still expect euro-using countries to have lower βs than non-euro-using countries solely due to euro-using countries having relatively freer movement of goods and factors of production.

Perhaps the establishment of the euro in 1999–2002 raised the β for some countries and lowered it for others. Indeed, the βs shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4 for euro-using countries diverge more after the euro was established (1999) than before. This increased variance in the βs for the euro-using countries after 1999 fits with the standard deviations for the data shown in the bottom half of Table 1. For the euro-using countries as a group, the standard deviation for (net savings)/GDP rose by 12.18 percent, (net investment)/GDP fell by 1.85 percent, (gross savings)/GDP rose by 14.18 percent, and (gross investment)/GDP rose by 2.76 percent. In contrast, after 1999, the standard deviation for non-euro using countries as a group for (net savings)/GDP fell by 20.5 percent, (net investment)/GDP fell by 41.22 percent, (gross savings)/GDP rose by 11.14 percent, and (gross investment)/GDP fell by 36.62 percent.

This increased variance in both the data (shown in the bottom half of Table 1) and the estimated βs for euro-using countries (shown in Figure 2 and Figure 4) after 1999 is possible because euro-using countries into which capital flows would have rising d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP), which is β, and countries out of which capital flowed would have falling d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP). To see if this hypothesis fits the historical record, the experiences of Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Germany were considered. (Space and time limitations prevent us from examining all 22 countries used in our data analysis.) Table 3 lists the RTPLS estimates when net investment and net savings were used, along with the 95% confidence intervals for these four countries.

Table 3.

d(Net Investment)/d(Net Savings) and 95% Confidence Intervals for Select Countries.

Consider Ireland, which Figure 2 and Figure 3 show had the most unstable d(Gross I)/GDP/d(Gross S)/GDP of all the countries analyzed. Ireland’s β was the most unstable probably because Ireland is a major international financial center with multinational corporations playing an unusually large role in Ireland’s tradeable sector (Lane, 2014), and both traits would facilitate the relatively rapid inflow and outflow of foreign capital. The first β peak for Ireland in Figure 2 occurred in 1979. Ireland’s (Gross I)/GDP rose from 0.285 in 1978 to 0.324 in 1979 before falling to 0.273 in 1980 and staying close to constant at 0.278 in 1981; meanwhile, Ireland’s (Gross Savings)/GDP were 0.182 in 1978, fell to 0.169, then to 0.153, and then to 0.134 in 1979, 1980, and 1981, respectively. Ireland was able to maintain a relatively high (Gross Investment)/GDP ratio during these years of a declining (Gross Savings)/GDP precisely because foreign capital inflows filled the resulting gap. Consequently, Ireland’s estimated β for the gross analysis rose from 0.840 in 1978 to 1.138 in 1979, fell to 0.922 in 1980, and rose again to 1.090 in 1981.

Ireland’s β hit its lowest value of 0.122 in 1993 when Ireland’s (Gross I)/GDP was 0.155 and (Gross S)/GDP was 0.184. Ireland’s β hit another peak in 2019 of 1.203 when Ireland’s (Gross I)/GDP was 0.537, and (Gross S)/GDP was 0.337, where inflows of foreign capital financed the gap.

Portugal’s β was the most unstable β when net investment and net savings are used as depicted in Figure 4. Unlike Ireland, Portugal does not have a major international financial center and did not experience a major housing boom (Reis, 2013). However, foreign capital did pour into Portugal starting in the year 2000. Table 3 shows that Portugal’s estimated β for the net analysis rose from 1.03 in 1998 to 1.29 in 2000. Reis (2013) argues that Portugal’s 2008 crisis was due to Portugal having “underdeveloped credit markets” which “caused foreign capital to go to unproductive firms in the non-tradable (services) sector, in turn causing productivity to fall and the real exchange rate to appreciate, taking away resources away from the tradable (manufacturing) sector.” When the worldwide crisis hit, foreign capital exited Portugal with “devastating” consequences. In 2008, Portugal’s estimated β for the net analysis was 2.10, but fell to 1.75 in 2009.

Portugal’s (net I)/GDP was 0.071 in 2007, while (net S)/GDP was negative 0.026, where the gap was made up by foreign capital inflows. As a result, Portugal’s estimated β in 2007 was 1.358. In 2011, Portugal’s (net I)/GDP was 0.010 and (net S)/GDP was negative 0.043, resulting in an estimated β of 0.676. For 2012 through 2014, both Portugal’s (net I)/GDP and (net S)/GDP were negative, causing Portugal’s estimated β to plummet to values lower than 0.125 (specifically, β was 0.101 in 2012, then 0.021 in 2013, and then 0.123 in 2014).

Veld et al. (2014) analyzed the Spanish economy between 1995 and 2013. They argue that, between 1995 and 2007, a falling risk premia, a loosening of collateral constraints, and a falling interest rate spread between Spain and the rest of Europe led to a boom in Spanish output and a “persistent rise in foreign capital flows to Spain.” In our Table 3, this corresponds to a rise in β for the net analysis, rising from 0.68 in 1995 to 1.13 in 2007. Veld et al. (2014) explain that during and after the Great Recession (2007–2009), falling home prices, tightening collateral constraints, and a credit crunch contributed to “a sharp reduction in capital inflows.” This reduction in foreign capital inflows shows up in Table 3 as β for the net analysis falling from 1.13 in 2007 to 0.39 in 2014.

Germany makes an interesting case study. East and West Germany were reunited by the end of 1990 on terms that were very favorable to the East. For example, the East German Mark was exchanged 1 to 1 for West German Marks in spite of the East German Mark’s true value being a lot less. Also, significant efforts were made to equalize wage rates between the East and the West. These favorable-to-the-East reunification efforts led to Bundesbank (Germany’s central bank) being concerned about future inflation. Thus, the Bundesbank drove up Germany’s interest rate. Meanwhile the rest of Europe was in a recession putting pressure on the rest of Europe to drop interest rates. The rising gap between German interest rates and interest rates in the rest of Europe (ROE) caused capital to flow from the ROE to Germany, putting downward pressure on ROE exchange rates. These events “precipitated the worse crisis in the thirteen-year history of the European Monetary System, resulting in the ejection of the sterling and the lira from the ERM,” European Exchange rate mechanism (Sevilla, 1995).

The inflow of foreign capital to Germany shows up in Table 3 as Germany’s β for the net analysis rising from 0.58 in 1990 to 0.71 in 1991. In the decades after the turn of the century, Germany became a major exporter of capital (which fits with her large trade surplus) and Germany’s β ranged between 0.35 and 0.17 between 2004 and 2023.

Figure 3 and Figure 5 show that none of the non-euro-using countries experienced the dramatic changes in β that Ireland and Portugal experienced. The inflows and outflows of foreign capital reveal itself in Figure 3 and Figure 5 by the divergence of β estimates, not by β falling towards zero for all countries—when foreign capital flows into a country, that country’s β rises and when capital flows out of that country, it’s β falls.

What Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Germany illustrate is that d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) rises when countries import foreign capital and it falls when countries export capital. Briefly, for this paragraph only and solely for illustration purposes, consider if (1) all countries have the same GDP and (2) all savings is used to fund investment, then capital moving from country A to country B (with the requisite change in trade flows) would cause d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) to rise for country B exactly as much as d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) would fall for country A. Thus, if you plotted (I/GDP)/(S/GDP), this would put an observation above the best fit line the exact same distance it would put another observation below the best fit line. If this is true for all observations, the slope of the best fit line would have to be numerically one.

If the capital receiving country has a lower GDP than the capital giving country, then d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP) would rise more for the capital receiving country than it would fall for the capital giving country which could push the slope above one, especially if most capital flowed from countries with higher GDPs to countries with lower GDPs. The opposite, of course, could also be true. The fact that capital flowing into a country would cause (I/GDP)/(S/GDP) to rise and capital flowing out of a country would cause (I/GDP)/(S/GDP) to fall seems to imply that the conceptualization of the Feldstein and Horioka (1980) puzzle is flawed. Feldstein and Horioka (1980) seem to be thinking in terms of one country—if capital is perfectly mobile, then there would be no relationship between a given country’s investment (I) and savings (S), but this way of thinking does not consider that the flow of capital involves at least two countries and the one that imports capital will have a rising (I/GDP)/(S/GDP) while the one that exports capital will have a falling (I/GDP)/(S/GDP).

If we are correct, then the establishment of the euro in 1999 causing increased capital flows would show up as greater variance of β, not as falling β as supposed by Feldstein and Horioka. To statistically test for changes in variance, we used the classical F-test and robust Levene-Brown-Forsythe tests which are shown in Table 4 for the net analysis and in Table 5 for the gross analysis.

Table 4.

Tests of Variance of net β estimates Pre- and Post- 1999, and Euro versus Non-euro.

Table 5.

Tests of Variance of gross β estimates Pre- and Post- 1999 and Euro versus Non-euro.

Table 4 shows that within the Eurozone, the volatility of the net β estimates rises markedly after 1999: the standard deviation increases from 0.200 to 0.305, and both the classical F-test and robust Levene–Brown–Forsythe tests strongly reject equality of variances (p < 0.01). In contrast, non-euro countries show no comparable change, with net β variances statistically indistinguishable before and after 1999.

Before monetary integration, net β volatility is similar across Eurozone and non-euro economies. After 1999; however, Eurozone members exhibit substantially greater dispersion than non-euro countries, a difference confirmed by both classical and robust variance tests (p < 0.01). Taken together, these net results indicate that the introduction of the euro is associated with a significant increase in cross-country heterogeneity in the saving–investment relationship among member states.

Table 5 shows that gross βs for the Eurozone did not significantly change pre- and post-1999, but that the gross βs for the non-euro-using countries significantly declined after 1999. Non-euro zone gross βs were more volatile pre-1999 than were Eurozone βs but the opposite is true after 1999–Eurozone volatility of gross βs exceeded non-Eurozone βs volatility. Considered together, the statistical tests for the variance of βs provide evidence that freer movement of capital and goods leads to rising variance of βs, not falling βs.

Given that (I/GDP)/(S/GDP) would rise for countries that import capital and fall for countries that export capital, the Feldstein and Horioka (1980) slope estimate that was insignificantly different from one is not surprising. But our finding a slope of 0.5 (standard error = 0.017) when gross investment and savings are used and a slope of 0.717 (standard error = 0.0213) when net investment and savings are used is surprising (see Equation (13)). We believe that we are finding slopes much less than numerically one due to not all savings being used to finance fixed capital formation (I). We believe that there currently is a global glut of savings that is simply not being used to fund production-expanding investment because there is insufficient consumption to justify production-expanding investment to occur. Instead, lots of savings are now sitting idle or being used in ways that do not increase production-expanding investment (like purchasing gold, land, or real estate).

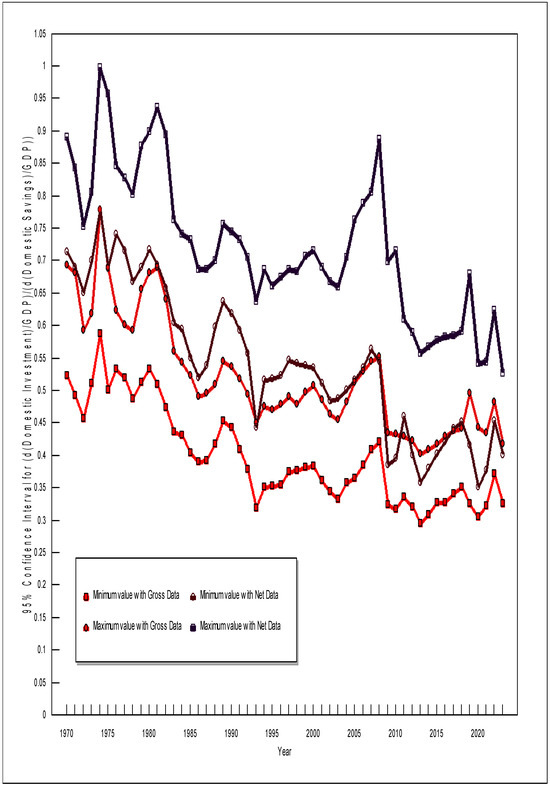

Figure 6 shows 95% confidence intervals for each year of the data for the RTPLS estimations when both gross and net data are used. When calculating confidence intervals for a particular observation, we used Equation (11) with that observation’s RTPLS estimate and the RTPLS estimates for the four observations preceding it for that country. For Figure 6, we used Equation (11) and all the RTPLS estimates for all the countries each year. Figure 6 clearly shows that d(Gross I)/GDP/d(Gross S)/GDP and d(Net I)/GDP/d(Net S)/GDP are falling over time. Furthermore, this fall is statistically significant as shown by these confidence intervals not overlapping in all years. These results suggests that the global glut of savings has worsened over time—when all 22 countries in the data set are considered, the amount of production-expanding investment as a percent of GDP is falling relative to the amount of savings as a percent of GDP.

Figure 6.

Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for each year.

To further test the statistical significance of the fall in βs, we did a two sample t test on the euro-using and non-euro using countries pre- and post- 1999. We found a statistically significant (at a 99% confidence level) fall in mean βs between pre- and post-1999 for both euro-using and non-euro-using countries and for both the gross and net analyses.

While indicative, the evidence for a global savings glut would be more comprehensive if data from all countries were available. Unfortunately, the data to do that is unavailable. We included all the countries for which the needed data was available on the OECD website.

To formalize in a statistical fashion what Figure 6 visually shows, we regressed our estimated βs on a trend term (1970 = 1, 1971 = 2, etc.) and report the results in Equation (17).

The statistically significant negative coefficients for the trend terms show that we can be more than 99% confident that β is declining over time. When economists run regressions like those shown in Equation (17), the “trend” term is usually used as a proxy (albeit an imperfect one) for omitted variables that are related to time. We believe that at least one important omitted variable related to the trend term in Equation (17) is a worsening global glut of savings.

Net β = 0.801 − 0.00610(trend)

(0.213) (0.000407)

(0.213) (0.000407)

Gross β = 0.582 − 0.00438(trend)

(0.148) (0.000276)

(0.148) (0.000276)

One might wonder if rising depreciation could explain the falling βs. However, depreciation would only affect the net analysis and not affect the gross analysis. If rising depreciation is part of the explanation for the falling βs, then one would expect the net βs to fall further than the gross βs, but they did not.

Consider again the System GMM results. It is tempting to argue that greater goods and factor mobility under the euro led to savings having a weakened effect on investment in Europe after 1999; however, why then did the impact of savings on investment in non-euro-using countries fall even more than it did for the euro-using countries (74.6 percent fall for non-euro-using countries versus a 45.3 percent fall for euro-using countries)? A worsening global glut of savings is a reasonable explanation for the System GMM results for the non-euro-using countries.

Nadler (2025) attributes this global glut of savings to rising worldwide inequality. Leightner (2015) agrees with Nadler and explains that for production-expanding investment (the I of this paper) to occur, two things are required: (1) there must be enough savings to fund the investment, and (2) there must be the belief that what the investment produces will sell. In other words, there must be sufficient consumption to justify investment. In a world with rising inequality and a declining population, the global glut of savings is only going to worsen if the world’s governments do not take drastic measures.

All the regressions reported in this paper—Ordinary Least Squares (OLS), System GMM, and RTPLS—assume that the relationships between the dependent variable and the included independent variables are correctly specified. In this paper, those relationships are modeled as linear. If linearity does not hold, the resulting misspecification error would invalidate all parameter estimates and associated statistics.

The OLS estimates reported in Equations (12), (13), and (17) also rely on the standard assumptions that the error term has a zero conditional mean, is normally distributed, is homoscedastic (i.e., not autocorrelated), and is uncorrelated with the independent variables. The last requirement implies that no omitted variables systematically influence the slope coefficients. System GMM likewise assumes the absence of slope-affecting omitted variables, but its main advantage is its ability to address endogeneity arising from simultaneity or dynamic feedback.

The only estimator used in this paper that can accommodate omitted variables that affect slope coefficients is Reiterative Truncated Least Squares (RTPLS). A key advantage of applying RTPLS to panel or time-series data is that its estimated slopes can be plotted over time, allowing the researcher to visualize how omitted variables influence the underlying relationships. The RTPLS estimates reported here indicate that omitted variables have had a statistically significant impact on the estimated slopes (the 95% confidence intervals shown in Figure 6 do not overlap for all years).

However, RTPLS also has an important limitation: although it can detect whether omitted variables matter, it cannot identify the mechanism through which they affect the slope. RTPLS requires only one assumption about the error structure, i.e., the random noise is small relative to the influence of the omitted variables. Leightner et al. (2021) demonstrate that when random error is as large as the omitted-variable component, RTPLS no longer yields reliable estimates. But when omitted-variable effects are at least ten times larger than random noise, RTPLS produces less than one-third of the estimation error generated by OLS when the omitted-variables problem is ignored.

5. Conclusions

Feldstein and Horioka (1980) estimated (I/GDP)i = α + β(S/GDP)I, where “i” is for a given country, “I/GDP” is the ratio of domestic investment to Gross Domestic Product, and “S/GDP” is the ratio of domestic savings to Gross Domestic Product. This equation was estimated twice–once using gross investment and gross savings, and a second time using net investment and net savings. Feldstein and Horioka (1980) found a β of 0.89 (standard error = 0.07) when gross investment and gross savings were used and a β of 0.94 (standard error = 0.09) when net investment and net savings were used. Neither of these βs was significantly different from one, and both were significantly greater than zero.

According to Feldstein and Horioka (1980) these results conflict with an assumption of perfect capital mobility because, if capital were perfectly mobile, then β should be zero. However, Feldstein and Horioka (1980) were only thinking in terms of individual countries. When one considers that a country that exports capital would have a falling d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP), which is β, and countries that import capital would have a rising d(I/GDP)/d(S/GDP), one realizes that Feldstein and Horioka’s estimates that were insignificantly different from one make sense. Thus, we have argued that the Feldstein–Horioka puzzle disappears when a person considers capital exporter–importer pairs.

However, the above analysis raises another puzzle: why do our 1970 to 2023 estimates using OLS, System GMM, and RTPLS all produce β estimates that are statistically less than one? We believe that the answer to this new puzzle could be that the world is now suffering from a global glut of savings caused by savings sitting idle or being used to purchase assets that do not increase production—assets like gold, land, and real estate. Both intertemporal trade theory and general equilibrium theory would predict that global savings would equal global investment; however, in these theories, investment would include production-expanding investment via increases in fixed capital formation and non-production-expanding investment such as the purchase of gold, land, and real estate. These theories are consistent with our results if investment has shifted from production-expanding forms to non-production-expanding forms. Furthermore, an increasing global glut of savings is consistent with many countries having persistent current account surpluses, sovereign wealth funds growing, and declining real interest rates.

In a world suffering from a worsening global glut of savings, destabilizing capital flows are increasingly a problem. Indeed, Obstfeld and Taylor (2017) argue that countries now face a “financial trilemma” in which they can choose at most two of the following: financial stability, open capital markets, and autonomy over domestic financial policy. Afonso and Rault (2010) use a panel-data diagnostic applied to European data from 1070 to 2006 to show that government solvency is satisfied in fewer than half of the 15 EU countries they analyze: Austria, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and Sweden. Government solvency was not satisfied in Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain. Afonso and Rault’s (2010) results are even more alarming when one considers that they did not account for the effects of aging populations, which require greater government spending.

Author Contributions

A.S. conducted the System GMM analysis, the tests for significant changes in variance reported in Table 4 and Table 5, and the two sample t tests. She also wrote the text that corresponds to all these statistical tests. J.E.L. did everything else. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used on this paper is freely available on the OECD data website.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | For each equation, we selected the smallest lag window that satisfied AR(1) significance, AR(2) insignificance, and a mid-range Hansen p-value, using collapsed instruments to avoid proliferation. This yields lags (4–5) for net rates and (2–2) for gross rates. Net investment rates exhibit stronger short-term correlation with unobserved factors, requiring deeper lag instruments for valid GMM estimation, whereas gross investment can rely on shallower lags. |

| 2 | For the Eurozone regressions, instruments were based on lagged levels (lags 2–4) of the endogenous variables in the differenced equation, using collapsed instruments to prevent proliferation. The lag window was selected to satisfy AR(1) significance, AR(2) insignificance, and a mid-range Hansen p-value. The (2–4) range provides a balance between instrument strength and exogeneity given the shorter sample periods. |

| 3 | For the post-1999 euro subsample, the AR(1) test is slightly above conventional significance levels, likely reflecting small-sample limitations rather than misspecification. |

References

- Afonso, A., & Rault, C. (2010). What do we really know about fiscal sustainability in the EU? A panel data diagnostic. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 145(4), 731–755. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40587839 (accessed on 14 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N., & Tsoumas, C. (2009). A survey of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle: What has been done and where we stand. Research in Economics, 63, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, J., Kulasi, F., & Smith, R. (1998). The Feldstein-Horioka puzzle and capital mobility: A review. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 3, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogan, J. F., Cwik, T., Taylor, J. B., & Wieland, V. (2010). New Keynesian versus old Keynesian government spending multipliers. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 34(3), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldstein, M., & Horioka, C. (1980). Domestic saving and international capital flows. The Economic Journal, 90(358), 314–329. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2231790 (accessed on 11 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ford, N., & Horioka, C. Y. (2017). The ‘real’ explanation of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle. Applied Economic Letters, 24, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtz-Eakin, D., Newey, W., & Rosen, H. S. (1988). Estimating vector autoregressions with panel data. Econometrica, 56(6), 1371–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, C. Y. (2024). The Feldstein-Hoirioka puzzle or paradox after 44 years: A fallacy of composition. The Japanese Economic Review, 75, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, G. (2025, February 1–2). The darkening skies over Europe’s economy. The Wall Street Journal. C1 and C2. [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque, J., & Swanson, S. A. (2018). Understanding the assumptions underlying instrumental variable analyses: A brief review of falsification strategies and related tools. Current Epidemiology Reports, 5, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, P. R. (2014). International financial flows and the Irish crisis. Focus. Available online: https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/forum2-14-focus3.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Leightner, J. E. (2015). The limits of fiscal, monetary, and trade policies: International comparisons and solutions. World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Leightner, J. E., Inoue, T., & de Micheaux, P. L. (2021). Variable slope forecasting methods and COVID-19 risk. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadler, H. (2025). Tax policy and the global savings glut. Cardozo Law Review, 46(5), 3. Available online: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/cir/vol46/iss5/3 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Obstfeld, M., & Taylor, A. M. (2017). International monetary relations: Taking finance seriously, NBER working paper no. 23440. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w23440 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Reis, R. (2013). The Portuguese slump and crash and the euro crisis. Brookings. Available online: http://brookings.edu/articles/the-portuguese-slump-and-crash-and-the-Euro-crisis/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevilla, C. R. (1995, May 11–14). Explaining the September 1992 ERM crisis: The Maastricht bargain and domestic polities in Germany, France, and Britain [Paper presentation]. European Community Studies Association, Fourth Biennial International Conference, Charleston, SC, USA. Available online: https://aei.pitt.edu/7014/1/sevilla_christina.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Veld, J., Kollmann, R., Pataracchia, B., Ratto, M., & Roeger, W. (2014). International capital flows and the boom-bust Cyle in Spain. In Centre for applied macroeconomic analysis working paper 40/2014. The Crawford School of Public Policy at Australian National University. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).