Abstract

As part of the environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ecosystem, this paper evaluates fundamental success factors that influence external auditors and relevant stakeholders to be proactive and efficacious in sustaining corporate governance practices in emerging economies. The study presents a preliminary and conceptual policy framework aimed at enhancing sustainable corporate governance, to ensure effective auditing in the public sector, by applying an extensive approach based on agency and corporate risk management theories. Applying an online qualitative technique, exploratory focus groups were held in three countries. The participants were selected by their respective Supreme Audit Institutions, based on their experience and proficiency in public sector auditing. Among the fundamental success factors identified were capacity building for auditors. Validation interviews were conducted to confirm the conceptual government auditor capacity policy framework that is presented. Executive governments, legislatures, and legislative oversight bodies can benefit greatly from the empirical segment of this study to enhance sustainable corporate governance in emerging economies and obtain greater contributions from government auditors.

1. Introduction

In Westminster democracies, the interplay between public sector auditing, legislation, and sustainable corporate governance practices has long been acknowledged by the relevant stakeholders. According to scholars, a government (public sector) auditor is a crucial component of transparent and accountable corporate governance in the public sector (Funnell et al., 2016; De Widt et al., 2022; Younas, 2022). The government auditors contribute to the concept of responsible governance, just like every other stakeholder of the Westminster democracy’s governmental apparatus. The stakeholders include, among others, the government, citizens, legislatures, oversight bodies, investors, and donors. Therefore, when the Legislature or Parliament has the authority to hold the Executive branch, including state-owned enterprises (SOEs), accountable to the people through government auditors, then such a configuration of governance is considered responsible. In a nutshell, Parliament is the vehicle through which government auditors represent the public, or citizens. Thus, in theory, the Executive’s capacity to meet the Parliament’s accountability requirements will determine whether it continues to function as the government. Some scholars believe that this was the best style of governance since it ensures that every component of good governance worked in tandem to support one another (Funnell, 1994; Funnell et al., 2016; Younas, 2022). Therefore, sustainable corporate governance arrangements should apply to stakeholders’ interests regarding the management of state institutions.

To increase productive capacities and promote economic development as well as global expansion, several advanced and emerging economies, including South Africa and Ghana, have embraced the establishment of SOEs since the 1970s (World Bank, 2014). Today, many emerging economies provide essential services in significant industries such as finance, utilities, and natural resources through SOEs. In some emerging economies, state ownership of extensive production and services in aggressive industries persists. For instance, SOEs are responsible for 5% of job creation and 20% of investment worldwide. In certain nations, SOEs make up as much as 40% of total output (World Bank, 2014).

Supporting the notion of accounting being the language of business, corporate governance is a structure that manages and controls conflicts of interest between management and stakeholders (Younas, 2022). Thus, corporate governance offers the framework for establishing an organisation’s goals, whether they are private or public, as well as deciding how to achieve them and track its progress, including performance monitoring (OECD, 2015). Scholars confirmed that government auditors, boards of directors, management of SOEs, and public accounts committees (PACs) are essential actors of corporate governance sustainability (Yasin et al., 2016). The configuration of these actors not only strengthens but also solidifies public support for ESG. Therefore, it makes logical sense that the Legislature or Parliament would always prefer to have government auditors to inform them (providing assurance) about the sustainability of corporate governance (Funnell, 1994; Alabede, 2012). For this reason, the impact of government auditors remains a fundamental success factor for sustaining corporate governance practices both in advanced and emerging economies (Hannes, 2010; AGSA, 2019; Audit Service Sierra Leone, 2020). For Samanta and Das (2009) and Alabede (2012), a significant responsibility rests on government auditors to sustain corporate governance practices, as effective auditing often exposes corporate governance weaknesses and makes practical recommendations for its sustainability.

Nonetheless, considering the persistent systemic corporate governance failures and underperforming SOEs in both advanced and emerging economies (Soltani, 2014; AGSA, 2019; Pooe & Stlhalogile, 2023; Mchavi, 2025), the capacity of government auditors as critical mechanisms for sustaining democratic corporate governance has been questioned by stakeholders. Over the years, Ghana’s SOEs have seen terrible corporate performance and business failures due to full disregard for corporate governance, even with independent boards of directors and audit committees (Isshaq et al., 2009; Ministry of Finance Ghana, 2018; Maxwell et al., 2021). Therefore, the interplay between government auditors’ capacity and legislation, and how they influence sustainable corporate governance in emerging economies, deserves more investigation. In the context of emerging economies, sustainable corporate governance practices are either uneconomical or have diminished (Ayandele & Isichei, 2013; Chigudu, 2018), fueling speculation about the capacity of government auditors. Many SOE challenges are the result of corporate governance failures caused by the board of directors and shareholders, which are government agencies overseeing SOEs (UNECA, 2021; Mchavi, 2025). Perhaps the frameworks designed for the effective operations of SOEs are either extraneous or obsolete.

For stakeholders, good corporate governance and the capacity of external auditors are interconnected since auditing guarantees the accuracy and dependability of financial reporting, which fosters accountability, transparency, and probity. Regrettably, limited studies have been conducted to develop solutions for corporate governance sustainability in emerging economies’ SOEs (Owiredu & Kwakye, 2020; Mchavi, 2025). To reduce corporate failure, it is not surprising that many emerging economies have commenced extensive, sustainable corporate governance reforms without paying attention to the significance of external auditors’ capacity (INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; AGSA, 2019, 2024). Additionally, several researchers grapple to find convincing evidence on the fundamental success factors of government auditors (Hay & Cordery, 2018; INCOSAI, 2014), as studies on corporate governance advancement are negligible in emerging economies. There is, therefore, a dearth of meticulous research that investigates how government auditors in democratic systems contribute to corporate governance sustainability in emerging economies. In summary, a formal research question for the study was formulated as follows:

A deficiency in legislation and corporate governance frameworks, with specific reference to efficiency in SOEs arrangements, has encouraged executives and government appointees to act with impunity, leading to a disregard of the government auditor’s functions and unsatisfactory public service delivery, resulting in a corrosion of public trust in state institutions, hence the need to present a preliminary and conceptual policy framework aimed at augmenting sustainable corporate governance, through effective auditing in the public sector, by applying a comprehensive approach based on agency and corporate risk management theories.

To constrict these gaps, the present study utilised an exploratory chronological qualitative design to discover specific fundamental factors that impact the effectiveness of government auditors. Also, this study examined whether prevailing theories on auditing in the public sector and corporate risk management contribute to the body of knowledge.

In the context of contributions, this study considered aspects of auditors’ capacity, legislation, and sustainable corporate governance as significant requirements of the ESG ecosystem in emerging economies. Yet, in the debate over democratic theories, national audit institutions, including SAIs, have not been acknowledged as an effective risk management mechanism that may impact the improvement of sustainable corporate governance in emerging economies. Designing a conceptual policy framework with principles and recommendations for auditors’ capacity, legislation, and sustainable corporate governance was the overarching goal of the research. In countries such as Ghana, Sierra Leone, and South Africa, there is a substantial need for improved public sector auditing and sustainable corporate governance in the wake of massive corporate governance failures. Weaknesses of existing policies, legislative frameworks, and regulations for public sector auditing and corporate governance were identified for the attention of the scholarly literature, policy and lawmakers, regulators, and other key stakeholders in emerging economies.

Consequently, the application of online focus groups and validation interviews was significant and may be expanded upon in future comparative studies on the impact of auditors’ capacity on sustainable corporate governance in other contexts and economies, especially in emerging countries. For important stakeholders, such as legislative bodies, executive governments, public audit institutions, and investors, the empirical segment of this exploratory study offers unique insights. To prevent unforeseen corporate governance failures in the administration of SOEs and other public organisations in emerging economies, these stakeholders might use the study’s advice when fashioning policies and implementation instructions.

The subsequent sections include the literature review, theoretical framework, research design, and conclusion.

2. Literature Review

2.1. An Overview of Government Auditors and Legislation

Between 1785 and 1832, government auditors did not possess independent authority and held no direct connection to legislation (Funnell, 1994). Government auditors were deemed representatives of the Executive and, as such, functioned under the direct control of the Executive (Hart, 1960). The main purpose of government auditors, then, was fraud detection and the encouragement of integrity in dealing with government institutions through activities known as public sector audits. Subsequently, government audits in close connection to legislation emerged from 1832 to 1866. In Funnell’s (1994) view, a series of fragile governments during the middle decades of the nineteenth century motivated the redirection of the allegiances of government auditors to Parliament. Notwithstanding the significance accorded to the government auditors by the Westminster parliamentary government, the development of public sector audits in the UK during the nineteenth century did not receive critical attention. However, the expectations of financial accountability, transparency, probity and auditing in the public sector, as key machineries of good governance, were witnessed in the nineteenth century, where the UK Parliament exhibited curiosity concerning the expenditure and accountability of the military and other state-spending departments, leading to an Audit Act in 1866 for public sector auditing (Funnell, 1994, 2003; Avci, 2015; Funnell et al., 2016). The promulgation of this statute was largely attributable to the lack of eagerness by the UK Parliament—following the 1688 revolution—to establish mechanisms to control military spending (Funnell, 1994). In effect, these transformations in government auditing were a result of the extravagance of the Royal Navy and its conceited indifference to accountability for its expenditure.

From this perspective, government auditing and accounting practices can be traced to apathy in military accountability, which continued until it was opposed by the new public management (NPM) reforms in the twentieth century (Funnell, 1994; Bateman, 2018). The acceptance and promotion of NPM reforms in advanced and emerging economies have been the agenda of international financial institutions, including the World Bank, International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the African Development Bank (AfDB) (Adikara, 2014). The reforms were meant to render government auditors’ function more efficient, and promote expenditure management, transparency, and accountability, by adopting private sector practices (Guthrie et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the government auditors’ functions became an indispensable ingredient of the nineteenth-century constitutional reforms of the UK Legislature and of administration accountability, which eventually fashioned precedent for the modern practice of government auditing, across the globe (Bunn et al., 2018). Thus, the establishment of oversight-independent authorities, such as public audit institutions headed by independent government auditors with clear legislation, is deemed fundamental to democratic accountability, where audits are conducted to authenticate how public resources are expended and how officials working in the public institutions, including SOEs, adhere to the rules and regulations. This layout is seen as cementing the sustainability of corporate governance and stakeholders’ desire for ESG. Already, ESG standards are becoming more important in sustainability and evaluations of public organisations by government auditors in emerging economies (Hock, 2025; Profile, 2025). Certainly, the foundation of sustainable corporate governance continues to be the strong relationship between the independence of the board of directors, the capacity of external auditors, and the institutional ownership of both SOEs and private companies (Bunn et al., 2018; AFROSAI-E, 2021). In the context of emerging economies, there remains a gap in the literature on the critical functions of independent government auditors and legislation, creating the need for an in-depth study on the fundamental success factors of government auditors (Johnsen, 2019).

2.2. The Practice and Framework for Government Auditors’ Function

As deliberated in the previous sections, the nineteenth-century developments, particularly, led to the design of supreme audit institutions (SAIs) or national audit offices, mostly headed by independent government auditors known as Auditors-General, and the advancement of the practices and principles of government auditing. Following the Declarations of Lima and Mexico (in 1977), the Beijing Declaration (in 2013) recognised the universal goals of SAIs as the promotion of good governance and strengthening of citizens’ trust in public institutions (INTOSAI, 2014). These declarations emphatically underscored success factors such as government auditors’ independence, competency (capacity), fundamental ethical principles, and utilisation of technology tools and support (Funnell, 1994; Dye & Stapenhurst, 1998; OECD, 2012; Escobar Rivera et al., 2017).

As of 1983, the capacity of government auditor functions for sustaining progressive requirements in terms of state institutions’ operations between the Legislature and government could not be ignored (Funnell, 1994). In response to stakeholders’ demand for public sector governance and sustainable corporate governance, most emerging economies have developed their audit institutions, mandated by their respective jurisdictions to audit public institutions (IPU & UNDP, 2017) and, as such, have independent auditors professionally trained for various audit activities. The establishment of SAIs, where a qualified workforce is subjected to guiding principles and continuous capacity building in technology usage, is deemed a premise for effective auditing in the public sector, ensuring sustainable corporate governance in public institutions (UN, 2007; IPU & UNDP, 2017). Thus, a capacity-building framework for government auditors and SAIs, from this perspective, plays a key role in ensuring accountable governance and proper behaviour by managers of public institutions (Dutzler, 2013; INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; AFROSAI-E, 2021). It is recognised that sustainable corporate governance will be enhanced where government auditors frequently conduct performance audits and other audit types to assess public fund stewardship (INTOSAI, 1998; Hakeem, 2010). For instance, a violation of corporate governance practices in SOEs resulting from a culture of ignoring the independent government auditors’ recommendations in South Africa was captured by the 2019 audit report on local government institutions (AGSA, 2019). For Makwetu (2017), due to oversight weaknesses and a lack of monitoring, the audit findings of South African SOEs have continued to deteriorate.

In order to enhance the effectiveness of government auditors and render their functions more relevant in emerging economies, auditing in the public sector requires, inter alia, organisational independence, prosecution power, a formal mandate, capacity building, sufficient funding, competent leadership, competent staff, audit quality, stakeholders support, and professional training (Visser & Erasmus, 2002; DeFond & Francis, 2005; Octavia & Widodo, 2015; Asmara, 2016). Consequently, the independence of government auditors and corporate governance in the public sector is deliberated by several studies (Schelker, 2013; Gustavson, 2015; IPU & UNDP, 2017; Hay & Cordery, 2018; ICBC, 2018; Boakai & Phon, 2020). In most emerging economies, government auditors face several obstacles, including financial and logistical constraints, and an absence of relevant legislative mandates (World Bank, 1989; Visser & Erasmus, 2002), political interference, auditees’ resistance, and inability to follow audit recommendations that contribute to poor audit success and impact negatively on sustainable corporate governance (AGSA, 2019; Matlala & Uwizeyimana, 2020). This study also explored significant theoretical epitomes that boost the success factors of independent government auditors and their impact on sustainable corporate governance.

3. Theoretical Framing—Corporate Governance and Risk Management

Important theories such as agency and corporate risk management have always been linked to the origins of auditing and corporate governance. Since risk assessment buttresses a critical function of government auditors (Palermo, 2014; Barrett, 2022), it is impossible to ignore capacity-building strategies for government auditors and SAIs in corporate governance arrangements (OECD, 2012; Vergotine & Thomas, 2016). It ultimately boils down to the interests of stakeholders regarding the substantive tests of auditors and corporate risk assessments. Most organisations, including SOEs, are confronted with complex risks (Padovani, 2005; Cienfuegos Spikin, 2013), particularly those operating with a large number of employees and resources. These risks could include unpredictability, competition, technology threats, insufficient workforce training, financial reporting fraud, errors, and irregularities. Nonetheless, managers (agents) and business owners (principals) are the key actors in many organisations. Thus, the interaction between principals and agents, as well as the costs associated with keeping an eye on the agents’ actions, are explained by the agency theory (Ross, 1973). Agency hindrances and risk-sharing hindrances are the two main concerns in the principal–agent relationship that are addressed by the agency theory (Eisenhardt, 1989; Cordery & Hay, 2017). A conflict of interest between the principal and the agent creates an agency dilemma, which makes it costly for the principal to keep an eye on the agent’s behaviour. The fact that the principal and agent view risk differently also contributes to a risk-sharing issue. According to Yusoff and Alhaji (2012), agency costs encompass the expenditures associated with drafting, overseeing, and upholding agreements between disputing parties. These expenses or costs are related to employing assurance providers (external auditors) to stop agents from acting selfishly because of knowledge asymmetry. To mitigate the costs of the principal–agent relationship (Cordery & Hay, 2017), an auditing system or an external auditor capacity can assist in reducing these agency costs (Hay & Cordery, 2018). According to Bunn et al. (2018) and Funnell (1994), agency theory is applicable to parliamentary governance systems in many countries. Therefore, the government auditors, who are appointed to offer assurance on public institutions, including SOEs, represent the Legislature and citizens as principals (Boakai & Phon, 2020; Bunn et al., 2018; Cordery & Hay, 2017).

In line with sustainable corporate governance, risk management concentrates on decision-makers and resource managers as well as the external auditors (Cienfuegos Spikin, 2013; Barrett, 2022). The process of risk management, even though costly, creates public sector value (Zins & Weill, 2017). The International Organisation of the Supreme Audit Institution (INTOSAI) and audit firms have, over the years, contributed enormously to risk management in the public sector environment (Lim et al., 2017), as organisations and principal stakeholders are subject to sophisticated risks. Moreover, the significance of empirical studies on corporate risk management has increased during recent decades, focusing mainly on organisational management, stakeholders, processes of governance, and institutional economics (Modigliani & Miller, 1958; Williamson, 1998; Klimczak, 2007). Theoretically, risk management, from the standpoint of corporate governance, is often connected to organisations and stakeholders (Padovani, 2005; Cienfuegos Spikin, 2013), and the genesis of risk management is tied to a corporate body, comprising policy makers and those in charge of resources (Cienfuegos Spikin, 2013). As such, several considerations justified the acceptance of risk management and its importance for evaluating value-for-money, accountable and transparent corporate governance, in public sector arrangements (Demek et al., 2018). Thus, the capacity building for external auditors is perceived as a mechanism for evaluating the willingness towards and the monitoring of improved risk management implementation by organisations (Palermo, 2014; INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; AFROSAI-E, 2021). Furthermore, the adoption of risk management practices by the public sector as a principle of good governance for effective service delivery has become progressively dispersed over the years (Audit Commission, 2011; Cienfuegos Spikin, 2013). Consequently, the capacity of auditors is deemed to improve governance processes by examining how objectives and principles of organisations are established to guarantee effective management and control (UN, 2007; Rahmatika, 2014). According to Themsen and Skærbæk (2018), the tax financiers—who are usually the key stakeholders and include the citizens—will benefit once organisations implement risk management practices that guarantee trust in public sector institutions. As signified in the section above, it is still unclear whether current theories are adequate to address those fundamental factors of auditing in the public sector or if a novel theory is required.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

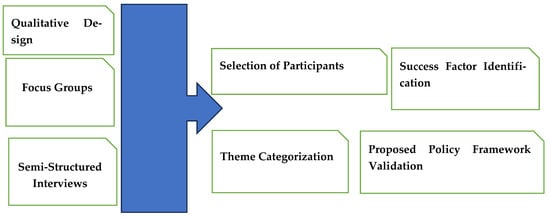

A qualitative methodology was adopted in this study to address the phenomenon. Using sociological viewpoints, communication, and social interface, qualitative research provides an invaluable lens through which to view human experiences, conduct, and social situations. Qualitative research is expected to follow the concept of trustworthiness to the extent that the research is dependable and that the findings are worthy of consideration. Thus, in the collection and analysis of the required data, all the participants enthusiastically constructed their own meaning of reality, derived from their experiences of engaging with the phenomenon in the context, using qualitative online focus groups and validation interviews. Figure 1 shows the qualitative design process used in this study.

Figure 1.

The flow research design.

4.2. Focus Group

To produce descriptive or illustrative data, an exploratory focus group discussion is typically led by a group facilitator in a social setting (du Preez & Stiglingh, 2018; Chand, 2025). Significantly, various scholars view focus groups as a method of group communication that produces substantive information for research and decision making (Duggleby, 2005; Creswell & Poth, 2018). What sets focus groups apart from other forms of data-generating interviews is their explicit use of exploratory group discussions (Krueger & Casey, 2014; Flynn et al., 2018). As a result, focus group conversations may uncover information through participants’ interaction that would be challenging to gather in a one-on-one interview. The acceptance of exploratory focus group discussions has gained a lot of attention in the literature because of growing interest in qualitative research techniques (Lathen & Laestadius, 2021). In their efforts to strengthen public sector governance reform in specific countries, the World Bank used exploratory focus groups as a participation mechanism (Kulshreshtha, 2008; World Bank, 2020). Thus, a significant benefit of adopting focus groups is their ability to obtain diverse perspectives in a distinct session, making them resourceful and valuable in content.

Conventional focus groups might be restricted by logistical issues, including participants’ convenience and geographic limitations, even though they provide insightful information about group dynamics and common viewpoints. However, virtual or online modalities have become a feasible substitute to address these problems, providing more convenience and flexibility for a range of demographics. For Lathen and Laestadius (2021), online or virtual focus group research is necessary to guarantee that qualitative approaches fulfil their maximum capability during times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. This study, therefore, illustrates the application of a focus group approach as part of a qualitative research design to investigate significant success factors that influence effective auditing in sustaining corporate governance practices. As recounted by Bédard and Gendron (2010) and Bevir (2010), issues regarding governance must be thoroughly investigated through the lenses of qualitative research design.

The present study applied an online qualitative technique, as an exploratory group discussion systematised to investigate a particular set of concerns (World Bank, 2020; Lathen & Laestadius, 2021), where participants from their standpoint established numerous fundamental factors that impact effective auditing and sustainable corporate governance in emerging economies. The participants who were knowledgeable about the research subject produced qualitative data, which resulted in factors (affinities) that could influence effective auditing. The findings were successively categorised into themes to determine the relationships among identified factors, leading to the realisation of fundamental success factors shaping the effectiveness of government auditing. Consistent with the objective of this study, constructive reasoning was used by the researchers and the focus group participants to elucidate or decipher the findings (Creswell & Clark, 2018). Following the successful categorisation of factors, a suggested policy framework was developed for effective government auditing in sustaining corporate governance in emerging economies.

Identifying Focus Group Participants

Following the formulation of the research problem, the focus group participants sought to represent their understanding of the phenomenon, its facets of meaning, and their proposed explanations. This approach relates to the interpretive paradigm in that knowledge is socially constructed. Therefore, the participants or constituents were selected based on certain factors, such as the degree of control over the event and how close they were to or how much they were affected by it (Northcutt & McCoy, 2004). In this study, the constituents comprised a purposive sample of 36 experts in public sector accounting/auditing, hailing from Ghana, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. As such, the constituents were selected as closest to the phenomenon under study, and they had the experience and authority to represent their reality regarding the factors that influenced effective auditing.

4.3. Data Collection via Online Focus Group

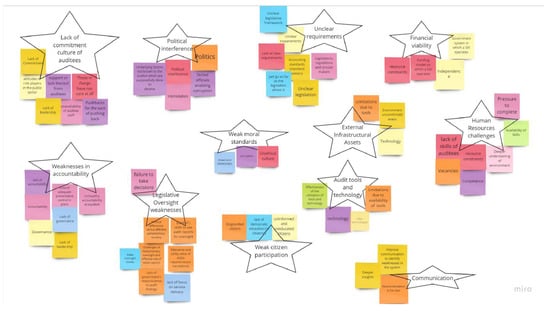

Conventional qualitative research generally recommends 6 to 10 participants in a focus group (De Vos et al., 2009; L. Cohen et al., 2011; Rule & John, 2011); however, according to Northcutt and McCoy (2004), an 8-to-12-member participation is required in an exploratory focus group—as the process does not inspire oral discussion—so as to lessen the likelihood of bias by domineering personalities. However, there is a propensity for participants to be disengaged, or their voices may not be heard in the focus group with many participants (Wyatt, 2010). Hence, during the focus group phase, the constituents’ opinions, insights, and experiences regarding the phenomenon being studied are explored via silent brainstorming to generate data. In this study, the focus group discussions were conducted via an online platform, using the Miro application to simulate the notecards and Zoom for the meeting, as online voice-based group discussions are prevalent in qualitative research (Gray et al., 2020; Lathen & Laestadius, 2021). The researchers gathered information or data in accordance with compliance-approved protocols to ensure trustworthiness. Following the authorisation of heads of SAIs in Ghana, Sierra Leone, and South Africa, three separate online focus groups were conducted in July through to August of 2022. These SAIs were chosen according to their usefulness, readiness to take part in the study, significant ranking position in the global project on SAI independence, and the authors’ convenience. The participants were leading managers with experience and proficiency in public sector accounting and auditing. A consultant and an authoritative psychologist led the focus groups to guard against researchers’ bias. System links were initially sent to the constituents via their email addresses, allowing them to sign up on the online platform. Commencing with the session, the constituents were asked to regulate their thoughts to a state of tranquillity and percipience (Northcutt & McCoy, 2004). They were then requested to reflect on their experiences regarding influences on effective auditing in the public sector, in silence. Towards the deconstruction and operationalisation of the research question, an issue statement on the phenomenon was initiated by the facilitator, as suggested by Mampane and Bouwer (2011), to initiate reflection. Thus, the constituents spent about 45 min quietly, following a brief discussion of the issue statement, reflecting on their experiences, and then typing their reflections on the notecards, with the aid of the Miro application whiteboard, to formulate the factors that influence effective auditing in the public sector. The number of notecards each constituent could place on the whiteboard had no limit; however, only one thought or experience per card was allowed—using words, phrases, and sentences. The task of the facilitator was strictly to guide the process and encourage the constituents to write without suppressing their thoughts, until they exhausted their ideas (Northcutt & McCoy, 2004, p. 69). Once every constituent was finished writing, notecards representing the factors were randomly displayed on the Miro application whiteboard. These individual ideas represented sub-factors. The cards were then grouped into comparable themes, and a discussion ensued to ensure that all participants agreed on the categorisation of the note cards. The participants then enhanced the sub-factor category and assigned a designation (factor). The purpose of recording the factor discussions was to document the participants’ interpretations of each factor. Data minimisation and retention were the outcomes of the first session, which is a good strategy for distilling meaning from vast volumes of data. The facilitators compiled a summary record of the factors for expanded analysis by the participants. The expanded analysis by the participants with the help of researchers resulted in reclassification and consolidation of identified factors (the expanded data analysis can be made available upon request). Represented in Figure 2 is the initial stage of formulating fundamental factors and sub-factors that influence government auditors or public sector auditing by focus group 2 participants. The participants of focus groups 1 and 3 also formulated several factors and sub-factors.

Figure 2.

Participants of focus group 2, formulating both fundamental factors and sub-factors.

4.4. Data Analysis

This phase offered convincing resolutions to the focus group question as well as the objective of the present study. As mentioned in the previous sections, the individual participant’s ideas represented the sub-factors. Thus, at the conclusion of the three distinct focus group sessions, the participants had established 153 sub-factors. At this phase of the focus group discussion, the participants categorised the sub-factors into comparable themes, and a discussion ensued to ensure that all participants agreed on the categorization of the sub-factors. The participants then enhanced the sub-factor category and assigned a designation, resulting in 33 factors as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Fundamental success factors and sub-factors developed by the participants.

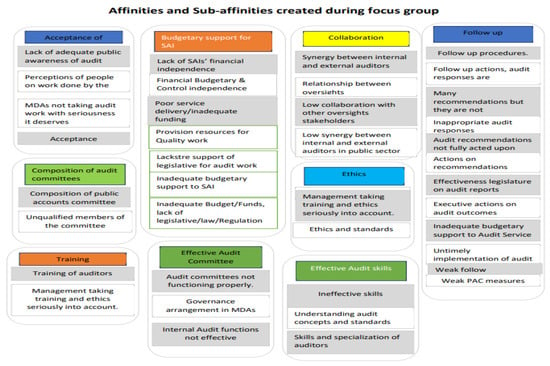

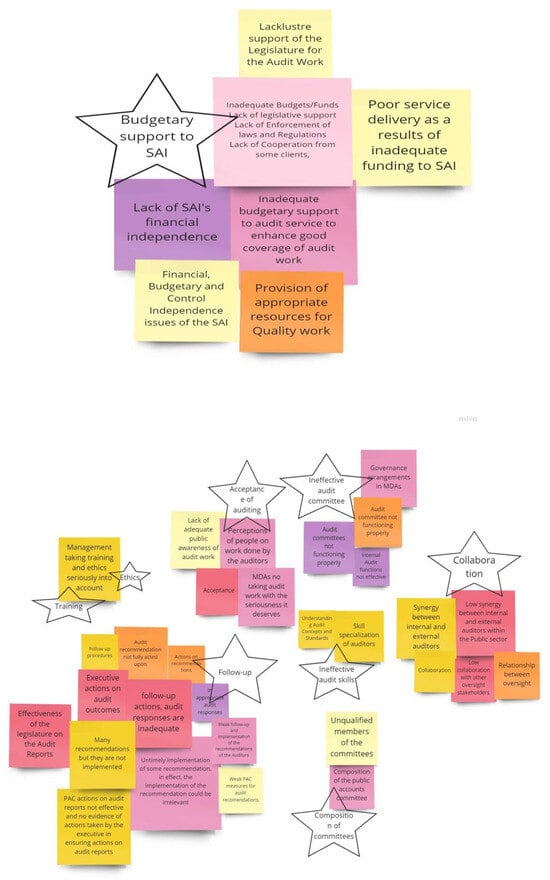

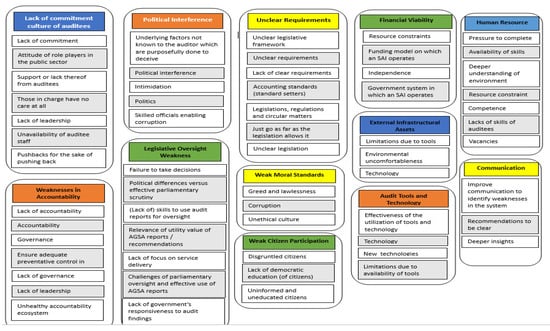

The participants also provided an interpretation of each factor in the form of descriptions, whilst the facilitator and researcher compiled a summary record of the factors for expanded analysis by the participants. The fundamental success factors and sub-factors of the various focus group participants were developed as illustrated in Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 3.

List of factors (affinities) and sub-factors (sub-affinities) developed by focus group 1.

Figure 4.

List of factors (affinities) and sub-factors (sub-affinities) developed by focus group 2.

Figure 5.

List of factors (affinities) and sub-factors (sub-affinities) developed by focus group 3.

4.5. Semi-Structured Validation Interviews

The second qualitative method selected for this study was semi-structured interviews. These interviews are primarily suitable for exploring individual respondents’ perceptions and opinions on delicate issues for further probing and clarification. Therefore, the semi-structured interviews were conducted after developing the framework from the literature review findings on the factors identified by the focus groups. The researchers deemed these interviews necessary to determine whether expert practitioners agreed with the framework derived from a more in-depth analysis of effective auditing influences identified by the focus groups. Twenty-five in-depth online interviews (Via MS Teams) were conducted to validate and refine a suggested policy framework. According to Guest et al. (2006), data saturation typically occurs within the first 12 interviews, after which only minimal new information is expected. Hennink and Kaiser (2022) also suggest that a sample size of 12 to 13 interviews is sufficient to achieve data saturation in qualitative studies. This sample size aligns with recommendations for qualitative research, which often suggests conducting between 10 and 50 semi-structured interviews (Ritchie et al., 2014; Mason, 2010). Additionally, Irani (2019) noted that face-to-face qualitative interviews are comparable to online interviews.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Findings

Following the analysis of data that was generated during the focus group discussions, 33 fundamental success factors with varying degrees of significance were developed out of 153 sub-factors by 35 participants (refer to Table 1). For participants from Ghana, 9 fundamental success factors out of 36 sub-factors with their respective significance or influence were identified (refer to Figure 2). Among the significant fundamental success factors identified by participants are acceptance of audit undertakings by stakeholders, composition of audit committee, continuous training of government auditors, budgetary support (financial capacity) for government auditors, effective audit committee, effective audit skills, and collaboration among oversight stakeholders as well as internal and external auditors.

For participants from Sierra Leone (focus group 2), 12 fundamental success factors out of 56 sub-factors with their respective significance or influence were identified (refer to Figure 3). Among the significant fundamental success factors identified by participants are logistical constraints, institutional experience of auditors, lack of independence, ethical requirements, capacity building of government auditors, corporate governance issues, authority of government auditors to prosecute those involved in inappropriate transactions with state institutions, and legislative requirements. The corporate governance issues include leadership, management, monitoring, structures, processes, and systems. For participants from South Africa (focus group 3), 12 fundamental success factors out of 61 sub-factors with their respective significance or influence were identified (refer to Figure 3). Among the significant fundamental success factors identified by participants are a lack of commitment, culture of auditees’ top management, weakness in accountability, political interference, weak moral standards among stakeholders, human resources, external infrastructure, and financial viability of government auditors.

5.2. Advancement of Comparable Fundamental Success Factors and Themes

Based on Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, undivided themes materialised following further analysis of the factors impacting government auditors and other stakeholders as revealed by the participants. By applying conceptual/theoretical coding as alluded to by Northcutt and McCoy (2004), the participants were required to select one of the three potential correlations between identified factors A and B, thus A affects B (A→B), B affects A (B←A), or there is no influence at all (A< >B). In the end, each participant completed a table known as a detailed affinity relationship table (DART), resulting in the rearrangement of factors. Subsequently, the rearrangement and consolidation of the factors led to the emergence of six themes, one of which was auditor capacity, as illustrated in Table 2. The focus group participants discussed what emerged to be similar factors and sub-factors by articulating their experiences as specialists. To prevent recurrence, themes were developed by merging both factors and sub-factors because several of the factors overlapped. The other 5 themes are budgetary constraints (financial viability of government auditors), auditor ethics, auditee corporate governance, audit tools and technology support, and legislative requirements (legal capacity). Succeeding the participants’ discussions, these five themes represent various capacities required for government auditors and other stakeholders to be effective in enhancing sustainable corporate governance in emerging economies. These five themes are regarded by the International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institution’s Capacity Building Committee as critical capacities necessary for government auditors to function effectively (INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; AFROSAI-E, 2021). As confirmed by the participants during the focus group discussions, the three most important areas of capacity building that INTOSAI and other donor agencies have supported throughout the years for government auditors have been professional capacity, organisational capacity, and institutional capacity (OECD, 2012). Already, research on capacity-building strategies for government auditors and SAIs with theoretical underpinnings is uncommon (Bergeron et al., 2017). Simply put, “capacity building” is the practice of improving an organisation’s management and governance so that it can achieve its goals and carry out its mission successfully (Kacou et al., 2022, pp. 1–2). Therefore, to fulfil a capacity-building strategy, SAIs must have government auditors possessed of indispensable knowledge and skills, as well as acceptable technical and management systems, physical infrastructure, and sufficient financial resources (Wing, 2004). Furthermore, SAIs may concentrate on government auditors’ training (technical capacity) whilst ignoring other problems, such as outdated audit tools and technology, outmoded legislative mandate, or a physical infrastructure that prevents auditors from implementing new and innovative practices (Fixsen et al., 2008). In summary, there must be a burgeoning curiosity in strategies to augment research on capacity building for government auditors and SAIs in emerging economies.

Table 2.

Advancement of auditor capacity by participants from distinct focus group discussions.

5.3. Discussion

The impact of an auditor’s capacity has been discussed in this section. This exploratory study has evaluated the fundamental success factors that influenced the capacity of external auditors and relevant stakeholders to be proactive and efficacious in sustaining corporate governance practices as part of the ESG ecosystem. It presents an auditor capacity policy framework aimed at enhancing sustainable corporate governance, together with adequate legislation, to ensure effective operation and performance of SOEs in emerging countries, utilising an extensive approach based on agency and corporate risk management theories. As depicted in Table 2, these analogous fundamental success factors emphatically validate why auditor capacity building is critical to sustainable corporate governance practices in SOEs. For some scholars, auditors’ capacities or capabilities are substantial inputs to the audit procedures, influencing effective risk assessment and their impact on sustainable corporate governance (Francis, 2011; Knechel et al., 2013; Sulaiman et al., 2018). In this context, the agency and corporate management risk theories can be linked to the capacity of auditors (INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; Cordery & Hay, 2022).

The focus group participants and interviewees underscored the influence of auditor capacity on public sector audit activities and their subsequent impact on sustainable corporate governance. The participants’ perceptions of the capacities of public audit institutions and government auditors align with those of important stakeholders, such as the World Bank (OECD, 2015; INTOSAI Development Initiative, 2020; AFROSAI-E, 2021). This is because corporate risk identification and management—also known as agency and corporate risk management—are crucial to the integrity and practice of auditing and how they are empirically bonded to sustainable corporate governance practices across the globe. The focus group participants debated that auditor capacity is a critical driver impacting the entire audit execution or engagements. Participants mentioned skills and specialisations of auditors, expertise required for audit execution, understanding of auditees’ systems, and institutional experience of auditors as critical drivers that influence the capacity of external auditors. As a result, government auditors are required to guarantee that corporate governance practices are fully fulfilled through audit execution and recommIendations (Anandarajah, 2001; Hay & Cordery, 2018; Schelker, 2013). Participants contended that capacity building for auditors and continuous training in technology also hypothetically influence external auditor capacity and, in that way, impact accountable and transparent corporate governance in most emerging countries. They alluded that fundamental success factors such as synergy between internal and external auditors, human resources, and collaboration with stakeholders, including shareholders, managers (business stewards), independent board of directors, and oversight bodies, significantly influence the effectiveness of government auditors. It makes sense that most of the participants during the focus group discussions decried the issues of corporate governance, such as leadership, management, monitoring, structures, processes, and systems, as important fundamental factors that underpin sustainable corporate governance, which can potentially be strengthened by government auditors via effective risk assessment. Significantly, it is necessary for public audit institutions in emerging economies to strengthen not only their professional capabilities but also their organisational capability and their capacity to deal effectively with the external environment of SOEs (Dutzler, 2013; OECD, 2015). It is thus suggested that constant human resources challenges could be addressed via the effective capacity development framework of public audit institutions. In this regard, they should implement capacity-building measures or programmes to assist them in building professional audit and institutional capacities, enabling government auditors to execute their mandatory requirements more effectively and efficiently. The focus group highlighted how the efficacy of public auditors had been positively impacted by legislative/statutory requirements. The focus group mentioned relevant laws, regulations, and standards as important fundamental success factors influencing public auditors and their direct impact on sustainable corporate governance practices. They mentioned that acquaintance with knowledge of applicable laws and standards would enable auditors to conduct audits effectively. However, the focus group expressed concern relative to outdated legal and regulatory frameworks meant for public audits and how some SOEs obstruct audit execution.

The focus group participants complained about poor governance arrangements with respect to SOEs, financial and logistical constraints, a lack of commitment culture of auditees’ leadership, and an unhealthy accountability ecosystem within the public sector. For instance, concerns regarding pushbacks and the risk of pushing back were also expressed by the focus group participants. The focus group indicated the need for independent government auditors (Auditors-General) to possess prosecution authority, questioning the impact this will have on public sector auditing, and how it will significantly improve public accountability and transparency in public corporations and SOEs. They mentioned the Auditor-General’s mandate, authority to prosecute, surcharge, and disallowance as significant influences on government auditors. The focus group reasoned that the Auditor-General fully implementing the surcharge and disallowance powers, as stipulated by the 1992 Constitution of Ghana, could impact accountability and transparency in public organisations. One issue they noted, though, was the absence of prosecutorial authority of government auditors, which left managers and the board of directors unaccountable and politically controlled over the operation of SOEs and publicly traded corporations. The construction of corporate governance frameworks or codes, as described at various forums and in several studies in the existing literature, is not the only solution to corporate governance failures in emerging countries, according to focus group discussions. Rather, much attention should be focused on fundamental success factors impacting the capacity of government auditors and SAIs.

For the economic advancement of emerging countries, launching suitable corporate governance frameworks and regulations for public institutions, especially SOEs, should be a top concern through the resource-based view of auditors’ capacity strategy. It is therefore obligatory to re-examine the legislation controlling government auditors and corporate governance practices in emerging economies. The World Bank assessment report on 118 countries revealed that public audit institutions need institutional capacity, human resources, and proficient audit skills in order to execute their key role of fostering not only sustainable corporate governance, but also public accountability and transparency (Anon, 2021), gaining the capacity of government auditors and SAIs to enhance sustainable corporate governance is a gradual process that demands funding in capacity building, professional training and the reinforcement of governmental or administrative capabilities (UNCTAD, 2019). In summary, a suggested auditor capacity is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The proposed auditor capacity policy framework.

6. Conclusions

The primary objective of this exploratory study was to evaluate the fundamental success factors that influence the capacity of external auditors and relevant stakeholders to be proactive and efficacious in sustaining corporate governance practices as part of the ESG ecosystem in emerging economies. The researchers further examined the relevance of legislation or regulations that ensure effective operations and performance of government auditors and state organisations, particularly SOEs. In doing so, the exploratory study evaluates how auditor capacity interfaces with legislation and stakeholders in public sector governance. The uncovered fundamental success factors are considered significant variables that strengthen auditors’ capacity and sustainable corporate governance practices in both advanced and emerging economies. In the end, an auditor capacity policy framework for effective auditing was developed, utilising an extensive approach based on agency and corporate risk management theories. In-depth data from focus group discussions and resource-based perspectives on ideas that influenced the study’s guidance were used to perform the exploratory study. The focus group participants’ perceptions were shaped by their different experiences, even though their roles and responsibilities as public sector auditing experts are comparable worldwide.

However, the comprehensive information (fundamental success factors) produced and the conclusions reached should be transferable to other comparable situations because the researchers employed an exploratory technique based on qualitative principles. Following the exploratory focus group discussions, 25 government auditing specialists participated in semi-structured interviews. These interviews helped to confirm and improve the substance of the proposed auditor capacity policy framework as illustrated in Table 3. It has been evident that auditors’ capacity building is interconnected to effective auditing and sustainable corporate governance practices and their implications on public accountability and transparency. The exploratory study filled considerable gaps in the research puzzle, resulting in important implications. To determine the fundamental factors influencing the capacity of external auditors in emerging economies, the researchers adopted an interpretive research methodology. As clarified in Section 5.2, despite the identification of six themes that impact effective auditing, this paper only focused on auditor capacity, which is directly and indirectly influenced by the other themes. Important ideas such as auditors’ capacity, stakeholders’ interests, and sustainable corporate governance, which require more research to promote the advancement of theories and their practical consequences in other emerging countries, were covered in detail by data analysis and focus group discussions.

The findings or results have important implications for policy and scholarly literature. This exploratory study was timely, given the concerning issues surrounding sustainable corporate governance in emerging countries and the paucity of research on the capacity of government auditors. As a result, the study provided a basis for further investigation and experimentation in the field of public sector auditing. In this study, the supply side of public sector auditing underscores the significant impact of auditors’ capacity, which legislators and other regulatory agencies in emerging countries should be aware of, given similar challenges. The viewpoint of emerging countries on the demand side of auditing in the public sector may provide more information for enhanced effective auditing, in addition to the study’s suggestions for future research. Consequently, the application of focus groups may be expanded upon in future comparative studies on the impact of effective auditing and auditors’ capacity in other contexts and economies, especially in emerging countries. In both advanced and emerging countries, stakeholders share a commitment to environmental security, auditors’ capacity building, and sustainable corporate governance. For important stakeholders, such as legislative bodies, executive governments, public audit institutions, and investors, the empirical segment of this exploratory study offers unique insights. To prevent unforeseen corporate governance failures in the administration of SOEs and other public organisations in emerging countries, these stakeholders might use the study’s advice when fashioning policies and implementation instructions. The preliminary and conceptual policy framework is yet to be empirically tested, although it was validated by experts in the field.

This study has limitations, which guide the recommendations for further research. The term “auditor capacity” in this context is broad enough to represent both the individual and the institution. Data gathered from focus groups in African countries was used in this study. For the exploratory phase, the research only focused on three countries, which may not be representative of all middle-income or African countries. However, since the researcher adopted an exploratory approach mainly founded on qualitative principles, the in-depth data collected and findings may be applicable to other similar settings (Krueger, 1998, pp. 69–70). Future research will be conducted to cover Asian and Latin American countries. Also, the researcher focused only on the SAIs in data collection (supply side) and did not include the other stakeholders (demand side). Although A. Cohen and Sayag (2010) and Alzeban and Gwilliam (2014) contended that the views of the supply side of services are less reliable than the demand side, when seeking to understand a specific phenomenon, it remains crucial to consider the opinion of the individuals that are part of the phenomenon, preceding the acquirement of other stakeholders’ views (Grix, 2004). Notwithstanding these contextual limitations, the research findings are expected to be of interest to an international audience, as public sector auditing has similar roles and objectives around the world, and the principles of public sector auditing effectiveness reflect these similarities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.K.A. and L.E.; methodology, B.K.A.; software, B.K.A.; validation, B.K.A., L.E.; formal analysis, B.K.A.; investigation, B.K.A.; resources, L.E.; data curation, B.K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.K.A.; writing—review and editing, B.K.A.; visualization, B.K.A.; supervision, L.E.; project administration, B.K.A.; funding acquisition, L.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research involved human participants. All procedures performed, including the request for participant selection, were in accordance with the standards of the institutional and/or Unisa College of Accounting Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee. The approved request letters to three Auditors-General in Africa and the Unisa Research Ethics Review Committee can be made available upon request.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study through their respective audit institutions.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the research findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the University of South Africa (Unisa) and the Unisa College of Accounting Sciences Research Ethics Review Committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adikara, H. K. (2014). New public financial management and its legitimacy. Asia-Pacific Management and Business Application, 3(1), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- African Organisation of English-Speaking Supreme Audit Institutions (AFROSAI-E). (2021). 2020 State of the region: ICBF self-assessment report. AFROSAI-E. Available online: https://afrosai-e.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2021-State-of-the-Region-%E2%80%93-ICBF-Self-Assessment-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Alabede, J. O. (2012). The role, compromise and problems of the external auditor in corporate governance. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 3(9), 114–126. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234629366.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Alzeban, A., & Gwilliam, D. (2014). Factors affecting the internal audit effectiveness: A survey of the Saudi public sector. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation, 23(2), 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandarajah, K. (2001). Corporate governance: A practical approach. Butterworths. ISBN 9812361561/9789812361561. [Google Scholar]

- Anon. (2021). Supreme audit institutions independence index. World Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmara, R. Y. (2016). Effect of competence and motivation of auditors of the quality of audit: Survey on the external auditor registered public accounting firm in Jakarta in Indonesia. European Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance Research, 4(1), 43–76. Available online: https://eajournals.org/ejaafr/vol-4-issue-1-january-2016/effect-of-competence-and-motivation-of-auditors-of-the-quality-of-audit-survey-on-the-external-auditor-registered-public-accounting-firm-in-jakarta-in-indonesia/ (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Audit Commission. (2011). The audit commission for local authorities and the national health service in England annual report and accounts 2011/12. The Stationary Office. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/247020/0249.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Audit Service Sierra Leone. (2020). Annual report on the account of Sierra Leone 2019. Audit Service Sierra Leone. Available online: https://www.thesierraleonetelegraph.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Annual-Report-on-the-Account-of-Sierra-Leone-2019.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Auditor-General South Africa (AGSA). (2019). Consolidated general report on the local government audit outcomes: MFMA 2018–19. AGSA. Available online: https://www.agsa.co.za/Portals/0/Reports/MFMA/201819/GR/MFMA%20GR%202018-19%20Final%20View.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Auditor-General South Africa (AGSA). (2024). AGSA Integrated Annual Report 2023–2024. Auditor General South Africa, 6(1), 16–171. [Google Scholar]

- Avci, M. A. (2015). Theoretical framework of the public audit. Review of Arts and Humanities, 4(2), 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ayandele, I. A., & Isichei, E. E. (2013). Corporate governance partices and chanllenges in Africa. European Journal of Business and Management, 5(4), 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, P. (2022). Managing risk for better performance—Not taking a risk can actually be a risk. Public Money and Management, 42(6), 408–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, W. (2018). Parliamentary control of public money [Ph.D. thesis, University of Cambridge]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, K., Abdi, S., Decorby, K., Mensah, G., Rempel, B., & Manson, H. (2017). Theories, models and frameworks used in capacity building interventions relevant to public health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 17, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevir, M. (2010). Democratic governance. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bédard, J., & Gendron, Y. (2010). Strengthening the financial reporting system: Can audit committees deliver? International Journal of Auditing, 14(2), 174–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakai, J. R., & Phon, S. (2020). The perceived need for audit and audit quality in the public sector: A study of public corporations in Liberia [Master’s dissertation, Högskolan Kristianstad]. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, M., Pilcher, R., & Gilchrist, D. (2018). Public sector audit history in Britain and Australia. Financial Accountability and Management in Governments, Public Services and Charities, 34(1), 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, S. P. (2025). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews, focus groups, observations, and document analysis. Advances in Educational Research and Evaluation, 6(1), 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigudu, D. (2018). Corporate governance in Africa’s public sector for sustainable development: The task ahead. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 14(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cienfuegos Spikin, I. (2013). Risk Management theory: The integrated perspective and its application in the public sector. Revista Estado, Gobierno y Gestión Pública, 11(21), 89–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A., & Sayag, G. (2010). The effectiveness of internal auditing: An empirical examination of its determinants in Israeli organisations. Australian Accounting Review, 20(3), 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2011). Research methods in education (7th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C. J., & Hay, D. (2017). Evidence about the value of public sector audit to stakeholders. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordery, C. J., & Hay, D. C. (2022). Public sector audit in uncertain times. Financial Accountability and Management, 38(3), 426–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- DeFond, M. L., & Francis, J. R. (2005). Audit research after Sarbanes-Oxley. AUDITING: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 24(s1), 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demek, K. C., Raschke, R. L., Janvrin, D. J., & Dilla, W. N. (2018). Do organizations use a formalized risk management process to address social media risk? International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 28, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A., Strydom, H., Fouche, C., & Delport, C. (2009). Research at grass roots for the social sciences and human service professions (3rd ed.). Van Shaik. ISBN 9780627030000/0627030009. [Google Scholar]

- De Widt, D., Llewelyn, I., & Thorogood, T. (2022). Stakeholder attitudes towards audit credibility in English local government: A post-audit commission analysis. Financial Accountability and Management, 38(1), 29–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggleby, W. (2005). What about focus group interaction data? Qualitative Health Research, 15, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Preez, H., & Stiglingh, M. (2018). Confirming the fundamental principles of taxation using interactive qualitative analysis. EJournal of Tax Research, 16(1), 139–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dutzler, B. (2013). Capacity development and supreme audit institutions: GIZ’s approach. In Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) & International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI) (Eds.), Supreme audit institutions: Accountability for development (pp. 51–68). Nomos. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, K. M., & Stapenhurst, R. (1998). Pillars of integrity: The importance of supreme audit institutions in curbing corruption. World Bank Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Rivera, D., Simon Villar, A., & Salzar Marrero, J. I. (2017). Auditors selection and audit team formation in integrated audits. Quality—Access to Success, 18(157), 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen, D. L., Blase, K. A., Horner, R., & Sugai, G. (2008, October 2–4). Taking EBPs to scale: Capacity building. The PBS Development Conference, San Antonio, TX, USA. Available online: https://fpg.unc.edu/sites/fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/reports-and-policy-briefs/SISEP-Brief1-ScalingUpEBPInEducation-02-2009.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Flynn, R., Albrecht, L., & Scott, S. D. (2018). Two approaches to focus group data collection for qualitative health research: Maximizing resources and data quality. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J. R. (2011). A Framework for understanding and researching audit quality. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 30(2), 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Funnell, W. (1994). Independence and the state auditor in Britain: A constitutional keystone or a case of reified imagery? Abacus, 30(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell, W. (2003). Enduring fundamentals: Constitutional accountability and auditors-general in the reluctant state. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 14(1–2), 107–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell, W., Wade, M., & Jupe, R. (2016). Stakeholder perceptions of performance audit credibility. Accounting and Business Research, 46(6), 601–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L. M., Wong-Wylie, G., Rempel, G. R., & Cook, K. (2020). Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. The Qualitative Report, 25(5), 1292–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grix, J. (2004). The foundation of research. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online: https://books.google.rs/books/about/The_Foundations_of_Research.html?id=E9q4dDVwsGkC&redir_esc=y (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavson, M. (2015). Does good auditing generate quality of government? The Quality of Government Institute. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/reader/43560370 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Guthrie, J., Parker, L., & English, L. M. (2003). A review of new public financial management change in Australia. Australian Accounting Review, 13(30), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakeem, A. A. (2010, May 26–27). Central elements of and prerequisites for independent SAIs in the light of the Lima declaration of guidelines on auditing precepts and the Mexico declaration on SAI independence. INTOSAI Conference on Strengthening External Public Auditing in INTOSAI Regions, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://sirc.idi.no/document-database/documents/intosai-publications/27-strengthening-external-public-auditing-in-intosai-regions/file (accessed on 14 August 2023).

- Hannes, S. (2010). Compensating for executive compensation: The case for gatekeeper incentive pay. California Law Review, 98(2), 385–437. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, J. (1960). Sir Charles Trevelyan at the treasury. The English Historical Review, LXXV(294), 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, D., & Cordery, C. (2018). The value of public sector audit: Literature and history. Journal of Accounting Literature, 40(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Sample sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science & Medicine, 292, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hock, O. J. (2025). Challenges faced by Malaysian MSMEs to adopt ESG standards. Journal of Information Systems Engineering and Management, 10(3), 1419–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCOSAI. (2014). Special XXI INCOSAI issue. International Journal of Government Auditing, 41(1), 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI). (1998). The Lima declaration of guidelines on auditing precepts. International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions. Available online: https://internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/LimaDeclaration.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI). (2014). Professional development in INTOSAI—A white paper. International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions. Available online: http://www.intosaicbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/White-Paper-on-Professional-Development-FINAL-DRAFT-1-OCT.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) & United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2017). Global parliamentary report 2017—Parliamentary oversight: Parliament’s power to hold government to account. Inter-Parliamentary Union & United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.ipu.org/impact/democracy-and-strong-parliaments/global-parliamentary-report/global-parliamentary-report-2017-parliamentary-oversight-parliaments-power-hold (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- INTOSAI Capacity Building Committee (ICBC). (2018). Strengthening supreme audit institutions: A guide for improving performance. International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions. Available online: https://www.intosaicbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Strengthening_SAIs_ENG-5.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- INTOSAI Development Initiative (IDI). (2020). Audit of public debt management. Available online: https://www.idi.no/elibrary/professional-sais/audit-lending-and-borrowing-frameworks/1040-audit-of-public-debt-management-version-1/file (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Irani, E. (2019). The use of videoconferencing for qualitative interviewing: Opportunities, challenges, and considerations. Clinical Nursing Research, 28(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isshaq, Z., Bokpin, G. A., & Onumah, J. M. (2009). Corporate governance, ownership structure, cash holdings, and firm value on the Ghana Stock Exchange. The Journal of Risk Finance, 10(5), 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, Å. (2019). Public sector audit in contemporary society: A short review and introduction. Financial Accountability and Management, 35(2), 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacou, K. P., Ika, L. A., & Munro, L. T. (2022). Fifty years of capacity building: Taking stock and moving research forward. Public Administration and Development, 42(4), 215–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimczak, K. M. (2007). Risk management theory: A comprehensive empirical assessment (Kozminski Working Paper, No. 01-2007). Leon Kozminski Academy of Enterpreneurship and Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Knechel, W. R., Krishnan, G. V., Pevzner, M., Shefchik, L. B., & Velury, U. K. (2013). Audit quality: Insights from the academic literature. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 32(Supp. 1), 385–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R. A. (1998). Moderating focus groups. Sage. ISBN 076190760. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kulshreshtha, P. (2008). Public sector governance reform: The World Bank’s framework. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 21(5), 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathen, L., & Laestadius, L. (2021). Reflections on online focus group research with low socio-economic status African American adults during COVID-19. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C. Y., Woods, M., Humphrey, C., & Seow, J. L. (2017). The paradoxes of risk management in the banking sector. British Accounting Review, 49(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwetu, K. (2017, November 1–11). 1 November 2017 Auditor-general reports a slow, but noticeable four-year improvement in national and provincial government audit results A. National and provincial audit outcomes. Auditor General Website. Available online: https://www.agsa.co.za/Portals/0/Reports/PFMA/201617/MR/2017%20PFMA%20Media%20Release%20FINALISED.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mampane, R., & Bouwer, C. (2011). The influence of township schools on the resilience of their learners. South African Journal of Education, 31, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. (2010). Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 11(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlala, L. S., & Uwizeyimana, D. E. (2020). Factors influencing the implementation of the auditor general’s recommendations in South African municipalities. African Evaluation Journal, 8(1), a464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, R., Yao, D., & Kwakye, M. (2021). Corporate governance and performance of state-owned enterprises in ghana. International Academic Journal of Economics and Finance, 3(6), 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Mchavi, N. D. (2025). Evaluating the role of ABM in the financial performance of SOEs in South Africa. HOLISTICA–Journal of Business and Public Administration, 16(1), 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Finance Ghana. (2018). 2017 State ownership report. Available online: https://www.mofep.gov.gh/sites/default/files/news/2017-State-Ownership-Report.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of Investment. The American Economic Review, 48(3), 261–297. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1809766 (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Northcutt, N., & McCoy, D. (2004). Interactive qualitative analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavia, E., & Widodo, N. R. (2015). The effect of competence and independence of auditors on the audit quality. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 6(3), 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2012). Good practices in supporting supreme audit institutions (pp. 1–77). OECD Capacity Building. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2015). The concept of accountability in international development co-operation. In Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (Ed.), Development co-operation report 2015: Making partnerships effective coalitions for action (pp. 67–74). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owiredu, A., & Kwakye, M. (2020). The effect of corporate governance on financial performance of commercial banks in Ghana. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 11(5), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padovani, R. (2005). Enterprise risk management in non-financial companies. Qualitiamo. Available online: https://qualitiamo.com/articoli/Enterprise%20risk%20management%20nelle%20imprese%20non%20finanziarie.html (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Palermo, T. (2014). Accountability and expertise in public sector risk management: A case study. Financial Accountability and Management, 30(3), 322–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooe, K., & Stlhalogile, M. (2023). Unsustainable decision-making in advancing state-owned entities: Can policy sciences reverse this? Journal of Public Administration, 58(3–1), 776–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profile, S. E. E. (2025, August). Katılım Finans Sektörüne Yönelik “Sürdürülebilirlik” ve “Sosyal Sorumluluk, Çevre ve Yönetişim (ESG)” Konulu Standart ve Rehberler Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme* [An evaluation of standards and guidelines on ‘sustainability’ and ‘environmental, social, and governance (ESG)’ in the Islamic finance sector]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394810742_An_Evaluation_of_Standards_and_Guidelines_on_%27Sustainability%27_and_%27Environmental_Social_and_Governance_ESG%27_in_the_Islamic_Finance_Sector (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rahmatika, D. N. (2014). The impact of internal audit function effectiveness on quality of financial reporting and its implications on good government governance research on local government Indonesia. Research Journal of Finance Accounting, 5(18), 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Nicholls, C. M., & Ormston, R. (Eds.). (2014). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (2nd ed.). Sage. ISBN 9781446209110. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S. A. (1973). The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. American Economic Review, 63(2), 134–139. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/aer/top20/63.2.134-139.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Rule, P., & John, V. (2011). Your guide to case study research. Van Schaik. eISBN: 9780627030048. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, N., & Das, T. (2009). Role of auditors in corporate governance. Social Science Research Network (SSRN). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelker, M. (2013). Auditors and corporate governance: Evidence from the public sector. Kyklos, 66(2), 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, B. (2014). The Anatomy of corporate fraud: A comparative analysis of high profile American and European corporate scandals. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(2), 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, N. A., Yasin, F. M., & Muhamad, R. (2018). Perspectives of audit quality: An analysis perspectives on audit quality. Asian Journal of Accounting Perspectives, 11(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]