1. Introduction

An “elephant in the room”, the first step of greenwashing, tax evasion and avoidance have had a complex relationship with sustainable finance. Tax issues are often studied through their related disclosure, such as the compliance regarding GRI technical standard 207 (

GRI, 2019) or through tax-related controversies. Tax issues are then reduced to a governance criterion, to check the potential inclusion of a company in an investment universe, that would fit with the values of end investors. Such assessment and use of tax issues refers more to “product and marketing” (for clients expressing interest in the issue) rather than to “financial integration”, if we refer to the two uses of ESG data identified by Serafeim (

Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, 2018).

Amel-Zadeh and Serafeim (

2018) clarified that product and marketing was the historic use of ESG data whereas financial integration was the emerging and future use of ESG data. This paper aims at assessing tax-related issues in order to enable its financial integration by sustainable finance professionals in the decision process and therefore contribute to deterring tax avoidance. Therefore, it aims at identifying and consolidating the use of easy-to-use ratios and complementary indicators.

For more than ten years, tax avoidance has been considered as a business strategy (

Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010), not as a set of good or bad practices. In 2017, tax avoidance was described as a risk continuum (

Gebhardt, 2017).

Hanlon mentioned the “exciting” nature of research on tax as different research fields (accounting, economics, and finance) produced various perspectives and languages over tax-related issues (

Hanlon & Heitzman, 2010). In a recent survey, Shin and Park mention that tax avoidance has already been correlated to market dominance and firm size, as well as with poor governance and bankruptcy risk (

Shin & Park, 2023). Still, the impact on firm value is uncertain as stakeholders perceive the increase in net profit positively, whereas bondholders fear increased credit risk and credit cost (

Dhawan et al., 2020).

Given the regulations implemented in recent years and further research launched recently, it is time for sustainable finance to join this exciting flow of research on tax issues. Sustainable finance cannot “wait and see” the impact of regulations because recent regulations provide improvement in global social welfare, not in terms of individual corporate risk reductions (

Diller et al., 2025). It is time for practicians and researchers to develop their own specific understanding of an integrated measurement of tax avoidance strategies as a risk continuum and to find a link between the tax avoidance levels and the financial risk of a company.

Tax issue represents a wide scope of questions, from tax evasion, using tax havens, to tax avoidance, which is considered as a legal optimization. Different wordings are often used about tax management: tax avoidance and tax evasion. Tax avoidance encompasses the legal means to reduce tax, such as tax asymmetries between countries, tax credits, and deferred taxes. Tax evasion refers to illegal means, such as concealing profits in tax heavens and understating results to postpone payments. Still, the difference might not always be as obvious. Referring to OECD wording, EU Commission consultation on tax regulation improvement reminds the following two points:

- -

tax evasion is defined as illegal arrangements where the liability to tax is hidden or ignored. This implies that the taxpayer pays less tax than he or she is legally obligated to pay by hiding income or information from the tax authorities.

- -

tax avoidance is defined as the arrangement of a taxpayer’s affairs in a way that is intended to reduce his or her tax liability and that although the arrangement may be strictly legal is usually in contradiction with the intent of the law it purports to follow (

European Commission, 2015).

Indeed, tax avoidance alone represents more than EUR 400 billon of non-paid taxes for the four major economies in Europe in 2019 (

Hazra, 2020). “Tax avoidance significantly reduces government revenues and therefore affects the level of public expenditure. In an economy where human capital accumulation depends on public expenditure, it is clear that tax avoidance can also affect this process.” (

Freire-Serén & Panadés, 2013). Europe is particularly vulnerable to tax avoidance as the level of tax in total GDP is higher than in other countries. However, tax rates have been significantly reduced by governments themselves for the last 45 years. Since the start of the deregulation trend in the 1980s, statutory taxes have decreased globally from approximately 49% in 1985 to 23% in 2019 (

Clausing et al., 2021).

The topic has become utterly complex, with new regulations generating new tax optimization expertise among corporate lawyers (

Diller et al., 2025). In order to synthetize the different influences on tax avoidance, Martinez defined four types of determinants of tax avoidance behaviors: companies characteristics (e.g., business life cycles, internal control mechanisms, financial constraints), environmental attitudes (product market competition, customer concentration, capital market incentives and tax planning), restrictions of gatekeepers (corporate networks, activist and institutional investors) and internal firms’ incentives (strategy defined by executive committee, size of internal tax department).

In 2019, in the Davos Word Economic Forum, Richard Bregman clearly mentioned that tax avoidance was the “elephant in the room” of sustainability and sustainable finance. Indeed, sustainable finance is about reintegrating environmental and social externalities into financial calculation. Therefore, the payment of taxes should be a key issue, or at least an issue, of sustainable finance and therefore a part of ESG analysis. Since this intervention of Richard Bregman in Davos in 2019, some significant steps have been achieved by academic and SRI research and about tax avoidance.

For instance, Sinna Willkomm showed that the prevalence of institutional investors (more prone to integrating SRI and ESG conditions) in the shareholder structure of companies was correlated with a lower probability for these companies to use tax avoidance practices (

Willkomm, 2023). In 2024, Schneider-Maunoury and Joubrel proposed a research agenda on ESG analysis. Their aim was to work out ratios that could be used over a large scope of listed companies, using the available data from annual accounts. They proposed 3 ratios: effective tax rate, deferred tax/income tax, and net deferred tax assets/total assets. They proved statistically that these variables were statistically independent.

Still, 2024 was the first year of implementation of the OECD GLOBE Project. The GLOBE project, and its subsequent regulations, have set up principles, thresholds, and tools that are taken not into account in these two abovementioned SRI-minded academic studies. In addition, these tools, notably the country-by-country reporting, enable us to better understand the different leverages of tax avoidance and to complete the previous list of ratios.

The literature analysis is based on the seminal paper with this first proposal of ratios. The ratios will be briefly explained and reframed. Second, there is a need to provide an in-depth analysis of the research produced on the link between sustainable finance and tax avoidance (

Willkomm, 2023). Then, the OECD GLOBE Project is presented in detail, as it enables us to understand the new set of available corporate data. The methodology first describes the assumptions to be displayed. Next, the quantitative variables that could be added to the model are displayed. The results display the link between tax avoidance risk and market volatility, proving the capacity to measure this risk continuum.

2. Materials and Methods

Synthetizing previous research (notably coming from macroeconomics or the field of accountancy research),

Schneider-Maunoury and Joubrel (

2025) proposed a research agenda on ESG and taxation. Considering tax strategies as a risk continuum (

Gebhardt, 2017), rather than as a set of multiple good or bad discrete practices, they propose to use three complementary ratios: the effective tax rate, the ratio of deferred tax to income tax, and the ratio of net deferred tax assets to total assets. They have demonstrated over the Stoxx600 companies that these three ratios were statistically independent.

Since 2022, tax issues have been deeply modified by some advanced academic research on tax and ESG issues, and by international regulation and notably the implementation of the OECD GLOBE project. The aim of this literature analysis is to check which data or indicator could be added to this first set of indicators.

2.1. Materials: Academic Research on ESG and Tax Avoidance

Academic research has started to reply to the critique raised by Bregman, by addressing the lack of attention given to the link between corporate governance and tax avoidance. A 2022 survey has answered the burning question of Bregman, that could be rephrased as follows: Is there a link between corporate social responsibility and tax avoidance (

Overesch & Willkomm, 2025)? Using a measurement of tax avoidance at a sister company level, they prove that the CSR level, measured by ESG and G scores of Refinitiv, is positively correlated with lower levels of profits shifting in the sister companies. We could argue that this takes into account only profit shifting between countries, not profit shifting over time. This shows that the suspicion of greenwashing to cover up tax avoidance is not relevant. But it is one measurement of tax avoidance.

Furthermore, academic research strove to the answer the question of the link between two deepened research areas: the potential use of ESG data to better analyze tax-related issues and the influence of SRI-inspired or ESG-aware investors on the tax behavior of a company.

First, ESG controversies data have been used in a counter-intuitive survey on ESG reputation and tax avoidance (

Menicacci & Simoni, 2024). Using Reprisk as its main source of information to measure the level of negative media coverage facing the firms, this research shows that negative media coverage can cause reputational damage, influencing companies to reduce their tax avoidance practices. Moreover, using a sample of Stoxx600 companies, this paper highlights the proximity between the extent of negative media coverage and the lower levels of tax avoidance. It is also counter-intuitive. A company receiving attention due to tax-related controversy tends to use less tax avoidance, making this indicator a monitoring tool for tax avoidance; as it damages reputation, it influences companies to adopt less aggressive tax strategies. This paper provides evidence of a strong relationship between negative media coverage and the ratios of effective tax rates and GAAP tax measures.

Second, Wilkomm identified a negative correlation between ownership by sustainable institutional investors and firms’ tax avoidance behavior (

Willkomm, 2023). Willkomm uses a specific indicator, rebuilt from data downloaded from Refinitiv: the difference between the amount of tax on pre-tax income computed at the statutory tax rate and the cash taxes paid, scaled by the pre-tax income (

Atwood et al., 2012). Sustainable investors (identified as signing the PRI) tend to reduce tax avoidance and have different preferences in terms of decision-making compared to institutional investors (

Full & Lorek, 2022;

European Commission, 2021). Moreover, while the PRI strengthened its efforts on tax responsibility with collaborative investor engagement between 2017 and 2019, the negative correlation between sustainable institutional investor ownership and the mitigation of tax avoidance became more pronounced and had a cumulative impact over time. Additionally, results indicated a difference in tax avoidance behavior according to the type of institutional investor (

Ferreira & Matos, 2008): “pressure-sensitive” institutions, which have strong business ties with investee firms tend to monitor less “pressure-resistant” institutions, which are more engaged in monitoring and with fewer business ties. A lower level of tax avoidance is observed in firms with greater ownership by independent institutions (pressure-resistant).

Willkomm’s results are consistent with recent results on the relation between governance and tax avoidance. Good governance practices, notably at the board and independent levels, as well as the separation of the CEO and Chairman, were related to levels of tax avoidance (

Tran et al., 2023;

Lungu et al., 2023). Tax avoidance is a long-term strategy, rather than a one-off practice, andit dimpacts the strategic deviation of a company versus its competitors (

Habib et al., 2024).

2.2. Materials Regulations and Notably the OECD GLOBE Project

Given the Diller contribution mentioned in the introduction (

Diller et al., 2025), we do not present the OECD as an exhaustive solution to tax avoidance issues. New regulations enable new ways to escape to it. It is important, however, to understand the regulatory framework and its ambition. OECD’s work on tax issues goes well beyond the definition of tax evasion and tax avoidance mentioned above. The Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) was established in June 2016 and brings together 142 countries and jurisdictions to collaborate on the implementation of the OECD/G20 BEPS package. It aims at reducing tax competition between countries. Tax avoidance is related to differences between countries and to different time periods. Given the differences in tax rates between countries, some companies play on the transfer price. The best example is to set up a license of use for the service and incorporate a company in a country where the tax rate on license fees is favorable. This squeezes the profit in the countries where the value is produced and it reduce the tax paid to the government in general. These differences between countries are now dealt with through OECD-inspired regulation, and notably the country-by-country report (BEPS action 13). Within the country-by-country reporting, companies are required to disclosed the location of revenues, assets, and employees and the tax paid in the different countries where the company and its group operate. Country-by-country reporting will be considered as mandatory for EU-listed companies, starting in 2026.

Pillar II is the second pillar of the new set of rules introduced by OECD and agreed by 135 parties (countries) on GLOBAL ANTI-BASE EROSION model rules (GLOBE) in 2021. The GLOBE aims at reducing the opportunity to locate profits in tax havens by eroding the base on which taxes are paid (reduce the use of transfer price and international management fee, to make it so that taxes are paid at a local level on relevant bases). Within the GLOBE rules, Pillar Two sets out global minimum tax rules designed to ensure that large multinational businesses pay a minimum effective rate of tax of 15% on profits in all countries.

In the EU, the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base (CCCTB) was a proposal for a common tax scheme for the European Union developed by the European Commission and first proposed in March 2011, that provides a single set of rules to calculate and consolidate EU taxes. The original proposal stalled, largely due to objections from countries such as Ireland and the UK. In June 2015, the commission announced they will submit a relaunched CCCTB proposal in 2016, featuring two key changes compared to the initial proposal: first, it would become mandatory (not voluntary) for corporations to apply the CCCTB regime, and second, the “consolidation part” will be postponed for a later follow-up proposal. The proposal was finally withdrawn in September of 2023 and replaced with a proposal for a council directive establishing a Framework for Income Taxation.

The tax issue in the EU is important, as companies have been drawing profit from asymmetries in tax systems. The topic has become utterly complex, with new regulations generating new tax optimization expertise among corporate lawyers and a relative disappointment and discouragement among academics. For instance, Martinez defined four types of determinants of tax avoidance behaviors: companies characteristics (e.g., business life cycles, internal control mechanisms, and financial constraints), environmental attitudes (product market competition, customer concentration, capital market incentives, and tax planning), restrictions of gatekeepers (corporate networks, activists, and institutional investors), and internal firms incentives (strategy defined by executive committee and size of internal tax department).

Regarding the objective of this research, this literature analysis has enabled us to confirm that there is no cover-up of tax avoidance by ESG disclosure and that companies react more directly to media coverage regarding tax avoidance, but so far, no complete measurement system of tax avoidance has been proposed, using regulated information of companies about tax avoidance. In order to summarize this literature analysis for academics and practicians, these are the data mentioned in the literature to seize the different leverages of tax avoidance, and the nature of the data.

Table 1 describes the quantitative and qualitative data used for the different leverages of tax avoidance. From a government perspective, a deferred tax asset is not illegal. It may appear reasonable if the company generates an external benefit for the community. For instance, if a company’s technological edge generates research programs for universities of the country, or activity and visibility for the ecosystem of start-ups working with the company, a deferred tax asset may be granted by the government a deferred tax asset, as it represents an intangible asset supported by the government. If such conditions are not met, it is more difficult to understand and admit. Then it may become a risk for the company and its investors.

2.3. Method: Assumptions, Data, and Variables

The major assumption of this survey is the following. Tax avoidance risk is correlated with market risk, measured by stock price volatility.

The scope of this survey is the Stoxx50 as selected in January 2023, January 2024, and January 2025. This focus on Europe is legitimate as regulations of European markets provide a safe and clear regulatory environment, prone to disclosure. It is also legitimate to focus on larger companies, as we can assume they have higher market positions and power than their smaller competitors. According to the previous literature, they are more prone to tax avoidance than their competitors.

A literature review highlighted the need to assess tax rate, deferred tax’s impact on income, and deferred tax’s impact on assets. Therefore,

Schneider-Maunoury and Joubrel (

2025) proposed three ratios, fit for the different targets:

- -

Effective tax rate (ETR): a first proxy of financial materiality, the level of tax rate paid by the company for continuing activities; it refers to financial materiality.

- -

Deferred taxes vs. income tax: a flow-based measurement (based on profit and loss account) of the use of deferred tax; it refers to impact materiality and more precisely to the trust we may have in governance.

- -

Deferred tax assets vs. total assets: a stock-based measurement (based on balance the sheet) of the use of deferred tax; it refers to financial materiality and more precisely to the risk it may represent for the financial stability of the company.

This set of basic ratios is consistent with the ones found in the earlier literature, as it includes one indicator on an effective tax rate and the other two are related to the book tax difference. Willkomm proposed the Atwood ratio: the difference between the amount of tax on pre-tax income computed at the statutory tax rate and the cash taxes paid, scaled by the pre-tax income.

Data have been collected manually for the first three ratios. This direct reference to corporate data is influenced by the results found on another issue of sustainable finance, climate data, that tends to question the quality of the vendor data. In that case, the same research led with corporate data has infirmed the results found with vendor data (

Aswani et al., 2024). For the Atwood ratio, we referred to the data provided by Refinitiv and we rebuilt the series of data. Over 50 companies, the data were available for 40 companies, which is a first availability constraint with these data.

Aside from these ratios, the country-by-country reporting (CbCr) provides data to check that there is no tax evasion towards tax havens and that there is no overuse of transfer pricing to significantly reduce the taxes in production countries. Regarding CbCr, a specialized website, EU Taxplorer, initiated by the academic expert Zucman, has centralized and provided a transparency assessment of CbCr reports based on two criteria: completeness and geographic scope. Completeness is assessed by the check of disclosure of the following ten variables (

Table 2):

Table 2 lists the variables expected to be disclosed in CbCr (revenue, income tax, tax paid …). However, the EU Taxplorer data are disclosed with only a 2-year time-lag. Therefore, we cannot use the results of EU Taxplorer in our research on 2024 data. We will only use the fact to publish CbCr as a way to verify that the low effective tax rate at a consolidated level does not hide the strong use of profit shifting between countries.

So far in annual reports published in 2024, only half of the Stoxxx50 disclosed country-by-country reporting or a set of data equivalent to the ones requested in the country-by-country reporting. In the future, CbCr could be used in a more detailed way, first through its completeness and scope and second through the inconsistencies it reveals, if, in a country, sales or employees are high and tax amounts very low.

Last, we downloaded the tax-related controversies of Moodys, ISS, and MSCI and we selected the four companies that were mentioned for active controversy in 2024. Four companies were then identified.

2.4. Method Related to the Different Categories (And Levels) of Tax Avoidance

Before potentially using the Atwood variable as a complementary ratio in the analysis, we needed to make sure, aside from its reduced availability, that it brings some extra information to the analysis.

Therefore, we proceeded to a multiple regression analysis, to see whether the Atwood could be explained by another three variables. In order to complete the analysis, we performed a principal components analysis in order to check the part of the total variance that is explained by the Atwood variable. The results in the following section show why we did not use the Atwood variable.

This identification of risk levels has been iterative. A first set of six groups has been tested, using complementary variables such as the disclosure of the impact of Pillar 2. However, this set of six groups appeared too messy, for two reasons. First, such an approach with six groups could be considered as splitting different sorts of practices, instead of identifying levels of risks. Second, the variable, such as the impact of Pillar 2, appeared as one-shot variable, that could be used only in 2024.

When looking at the data, and, more precisely, when reading the tax-related parts of annual reports, it appears that CbCr should not be considered as a simple disclosure, but as a way to make the information on tax avoidance verifiable. Under the assumption that the company does not have aggressive tax avoidance practices (checked by the quantitative variables), the CbCr is a condition of verifiability of a less risky tax avoidance strategy.

Last, we acknowledge the fact that being in a tax-related controversy is a source of risk and volatility in itself, whatever your quantitative tax avoidance strategy is.

The groups were built using three criteria, or three different tools or sets of tools, used as three successive filters of the population:

The first criterion used was the quantitative ratios. If the company achieves levels that could be considered as risky (ETR < 15%, DT/IT > 100%, DTA/TA > 5%) then the company is considered as risky. For ETR, the threshold of 15% refers to the GLOBE regulation threshold of 15%. For DT/IT, we had no benchmark and considered that a threshold over 100% is a sign of significant change in income tax through deferred tax. For DTA/TA, the threshold of 5% was chosen after a discussion with the High Council of Tax Issues in Greece, who informed us that all Greek banks were over 5% during the financial crisis of 2011. Ex post, we agree that it is relatively high and conservative. Indeed, audit rules consider that a topic over 2% of total assets is material.

The second criterion is the tax-related controversy. If the company is listed in the tax-related controversy list of the CSR rating agencies, it means a specific level of tax avoidance related risk.

The third criterion is to have country-by-country reporting. The variable is not used purely as a transparency tool as such, but as a way to verify the accuracy of the tax-related data at a country level.

These three layers of analysis enables us to define four groups, depicted as follows (

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5):

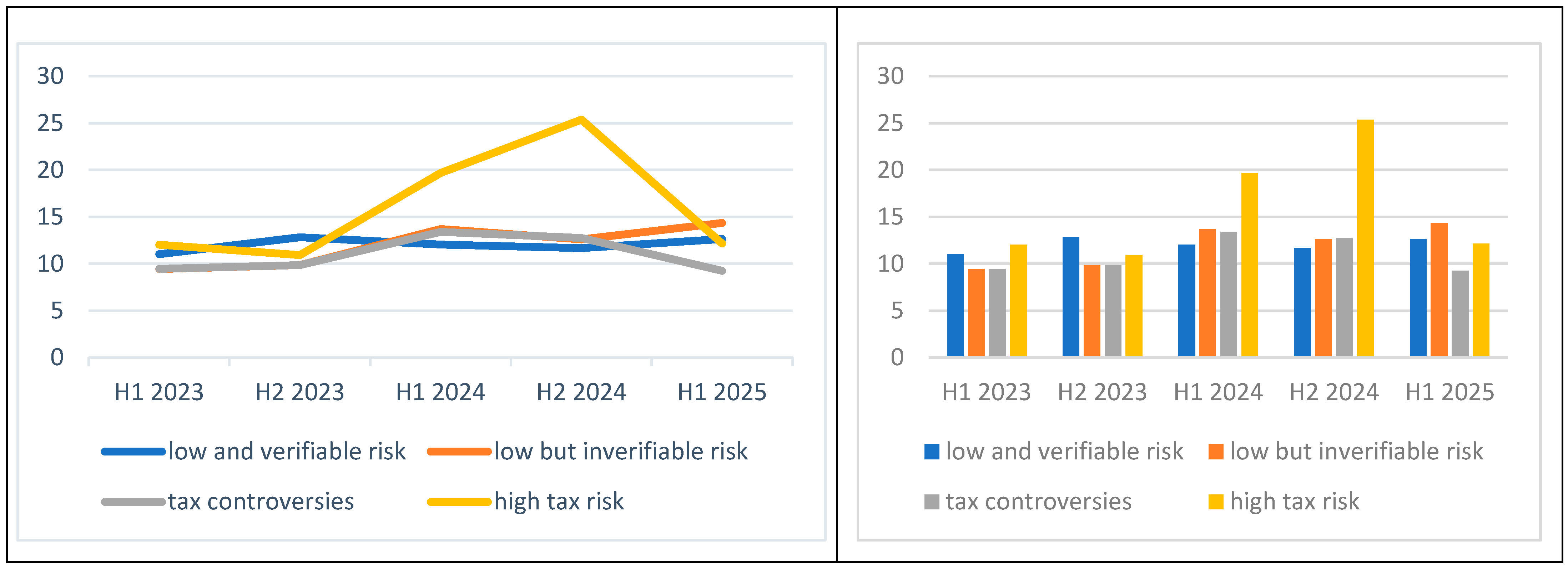

Table 3 describes the groups and their conditions. For example, Group 1 companies passed the quantaitive ratios test. The breakdown of the Stoxx50 companies in the different groups is provided below.

Table 4 displays the breakdown of companies in the different groups for the different time periods. In H1 2025, there are 13 companies in the high tax risk group. The breakdown of the tech and bank sectors that are excluded in further tests, and the results as their volatility is observed as very high and very low, respectively, are provided below.

Table 5 displays the breakdown of tech and banks companies in the different groups for the different time periods. In H1 2025, there are 3 banks and tech companies in the high tax risk group.

2.5. Measurement of Risk of the Samples Representing Different Levels of Tax Avoidance Risk

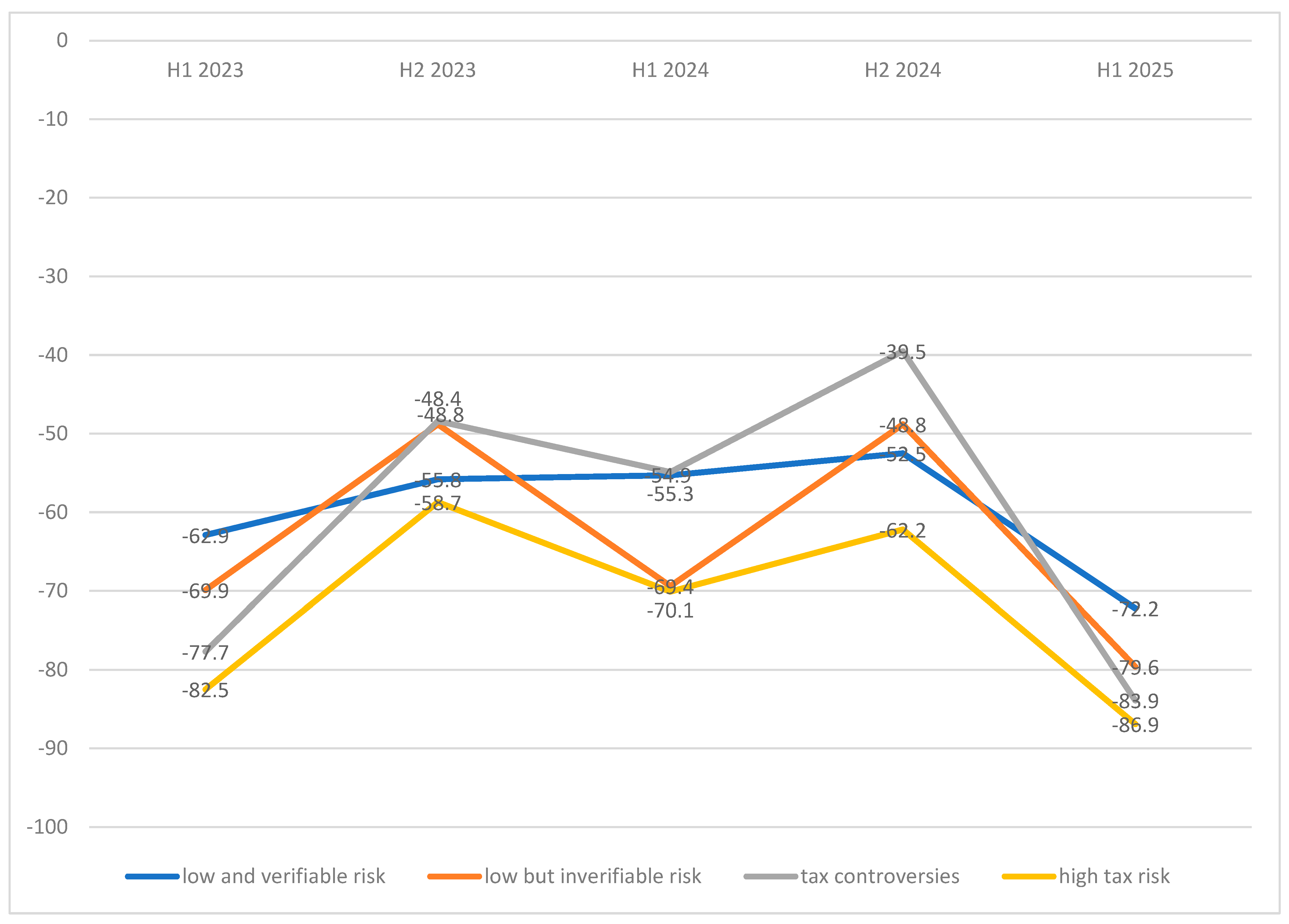

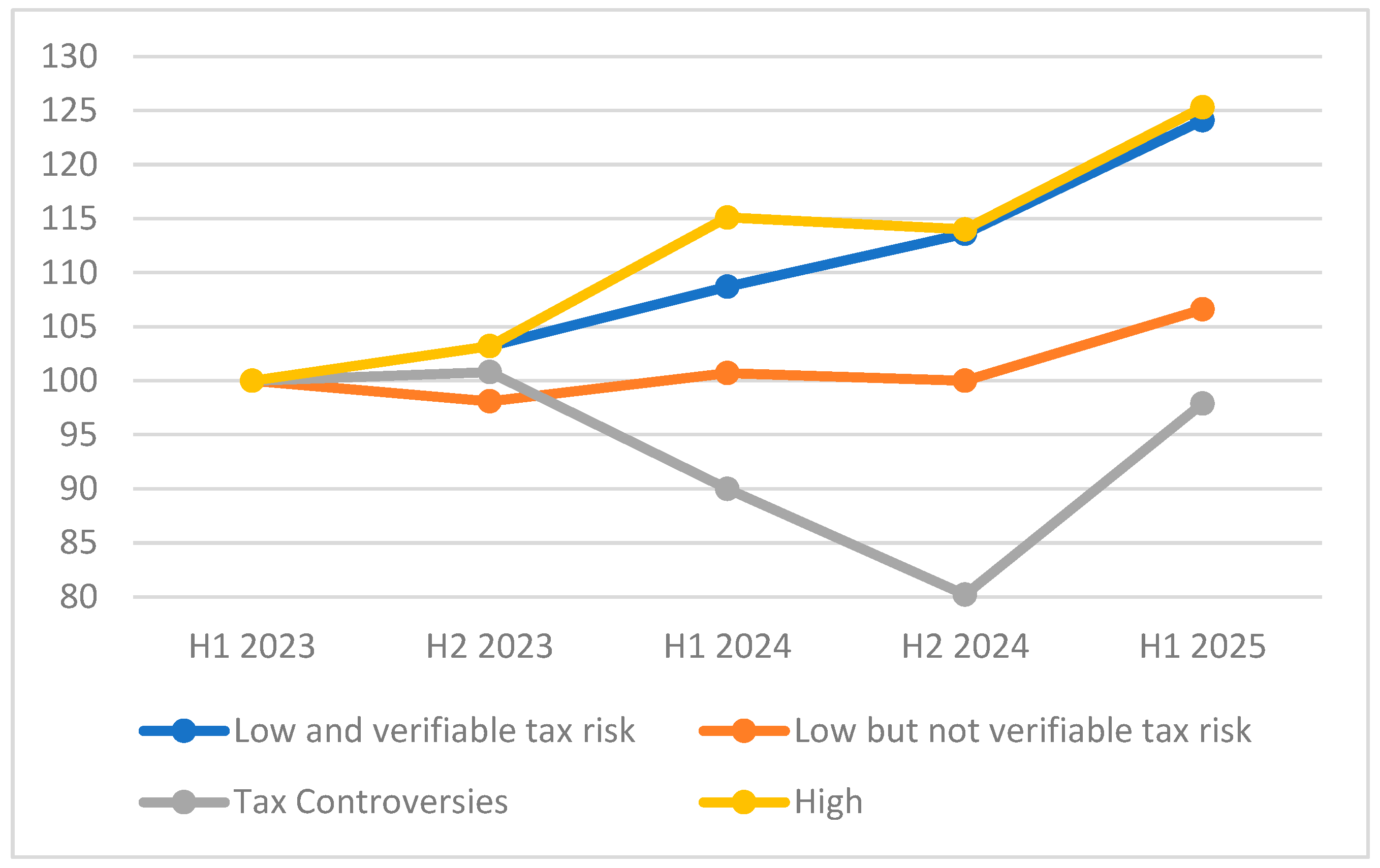

We have first looked at the correlation between tax optimization risk and stock price volatility, and then at the causality.

The stock price risk is measured for each company of each of these four groups for five consecutive periods (H1 2023 to H1 2025), from 1 January 2023 to 30 June 2025. We also add full year 2023 and full year 2024. The initial intuition was that the half year 2 result could enable us to catch the lagged effect of the tax-related risk.

It is calculated based on daily stock price. It is calculated for every group representing each level of tax optimization risk. It is calculated without rebalancing per period. Two results are presented, equally weighted and using market capitalizations of the first day of the period.

Given the high level of volatility, we also calculated the volatility of samples excluding banks (due to the low volatility of the sector) and tech (due to the high volatility of the sector).

We also used another measure of risk for 2024, such as Value at Risk. For the risk factor analysis following the Fama French model, for our analysis we used the tool Scientific Portfolio (

https://scientificportfolio.com/, 11 November 2025) In order to avoid any effect of portfolio construction and specific weighing, the components are taken individually.

The Fama French model is often used in market finance to assess whether the correlation found is due to the studied factor or is in fact determined by external factors, such as its sector, its specific performance (explained by fundamental analysis) or by wider market phenomena. The method does not pretend to demonstrate causality of this specific factor, in this case tax avoidance, on stock price volatility. Rather, it shows the link between tax avoidance and a larger variable (unexplained) which could be assessed later as the management quality.

Last, we reframed our results in the risk–return arbitrage and we calculated the average return for our different categories.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

These results confirm and clarify previous results:

- -

Link with market uncertainty risk: the results of this small sample show that there is a correlation between the tax avoidance risk, measured by the 4-level scale, and stock price volatility. This correlation is improved if two sectors are not taken into account.

- -

Added value of the ESG analysis (and notably the addition of qualitative data): the distinction between categories due to the use of qualitative data (country-by-country reports or controversies) enables us to find a better link with financial performance, i.e., risk–return arbitrage.

- -

A link with financial performance: the link between risk–return arbitrage and tax avoidance may explain why tax avoidance may be appreciated by shareholders (if not risk-averse) and simultaneously could be related to strategic deviation (explaining a 3-year overperformance of low tax avoidance practices).

The aim of the last results on causality is not to determine tax avoidance as the next best ESG criterion but rather to use these criteria as a proxy of quality of management (confirming the results on tax avoidance and strategic deviation) or of quality of governance, or, in an even more reduced perspective, the quality of audit (confirming again the previous results). In the case of quality of governance or audit, these data and related analyses could be added to usual ESG data related to governance analysis.

In a pragmatic perspective for sustainable finance practitioners, this analysis enables us to integrate tax avoidance into the financial analysis and investment decision process, and not only as a binary variable aimed at reducing the investment universe. Furthermore, if advanced ESG analysis can be used for financial integration, not for a marketing purpose, it could be used in the construction of a portfolio of funds aiming at deterring tax avoidance, or simply contributing to this aim (among other targets) by improving risk–return arbitrage.

Four main limitations may be discussed:

- -

This research has been led by a small sample, the Stoxx50. Aside from the logic of focusing on larger companies, more prone to tax avoidance, this choice has been made due to difficulties with data. Other samples in Europe as well as in other countries may display different situations. Some countries, for instance, are very skeptical of deferred tax assets, notably in Asia, making the results specific to a European context.

- -

Some data thresholds have been chosen by practical experience, rather than cross reference (DT/IT and DTA/TA, for instance). A more nuanced approach could improve the understanding of this risk continuum.

- -

This research has been focused on 2023 to 2025 data. A time scope from 2020 to 2025 would enable us to use data such as EU Taxplorer and provide longer time series.

- -

In this research, CbCr has been used as a binary variable that could be compared to a disclosure binary variable. However, the CbCr will enable a variety of levels in the future, according to the geographic scope of the CbCr a company can publish (by continent or by country, encompassing all countries or not, including tax heavens or not) as well as the thematic scope the companies can disclose (up to 10 variables to be broken down, from staff, to assets, not forgetting revenues and tax). In the future, the use of CbCr will not be reduced to a binary variable.