1. Introduction

Islamic finance has grown rapidly in recent decades, and equity investors now have many Shariah-compliant indices to choose from. Studies comparing these indices with conventional market benchmarks have produced mixed results. Some research finds that Islamic portfolios earn similar returns in calm periods, while others report that they do better during crises (

Al-Khazali et al., 2014). Most of this earlier work, however, examines only one Islamic index at a time and treats Islamic indices as if they all use the same screening and filtering methodologies.

In reality, each index provider follows its own set of rules. For instance,

Akartepe (

2022) shows that Shariah boards sometimes disagree on companies whose business lies in a gray area, activities that may or may not be acceptable under Islamic law. Because of these variations, two indices can label the same company as halal or non-halal and end up with portfolios that share surprisingly few stocks.

Assuming all indices are Shariah-compliant, Islamic investors deciding whether to pick a single Shariah index or to mix several indices therefore face a classical question: which screening method produces the best return and risk-adjusted return? Studies report mixed findings.

Ashraf and Khawaja (

2016) conclude that “screening does not matter much” based on 25 synthetic S&P portfolios. On the other hand,

Raza and Ashraf (

2019) demonstrate that equal-weight and low-volatility smart beta schemes outperform cap-weight Shariah indices in eight regions, while

Boudt et al. (

2019) obtain the highest Sharpe ratio by rotating among styles according to macro-financial regimes. Studies comparing Islamic with conventional benchmarks also report mixed findings.

Ashraf (

2016) shows that, for 2000–2012, Islamic index alpha disappears once sector weight and beta are controlled for.

In our research, we take a single, well-known universe: the current S&P 500 index. We then apply the five main Shariah rulebooks (Dow Jones Islamic Market, KLSI, FTSE Shariah, MSCI Islamic, and STOXX Islamic) quarter by quarter from 2019 Q1 to 2023 Q4 and build both equally weighted and market-cap-weighted portfolios according to each rulebook by analyzing each stock in the index one by one to determine whether it aligns with these rulebooks. Because the stock set stays fixed, any difference we find comes solely from the screening criteria.

We test the hypothesis that stricter Shariah rulebooks provide better protection in downward-trending markets and higher risk-adjusted performance (Sharpe, Treynor, and Jensen’s alpha) over the financial quarters between 2019 Q1 and 2023 Q4 than looser screens.

The head-to-head comparison delivers a clear message. All Islamic portfolios show very similar return patterns, which is in line with the literature. However, once we adjust for risk, the picture changes as follows: portfolios based on the STOXX and Dow Jones rules provide the highest Sharpe, Treynor, and Jensen’s alpha values. Their advantage seems to come from the fact that they suffer smaller falls and follow a more stable path, not because they earn higher returns. For investors, this means that choosing an index with stricter or looser Shariah filters can significantly shift their risk–return balance. For the companies that build these indices, it shows that small changes in cash, debt, or revenue limits directly affect performance, suggesting that agreeing on one common set of Shariah rules would make the market clearer and fairer.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a detailed review of the literature on Islamic equity markets, with emphasis on comparative performance studies, screening methodologies, and the need for standardization.

Section 3 describes the data, methodology, and index construction procedures used to isolate the effects of Shariah screening across major indices.

Section 4 reports and analyzes the empirical results, including cumulative returns, risk-adjusted performance measures, and seasonal patterns, with a particular focus on the distinction between market-cap and equally weighted portfolios.

Section 5 discusses the implications of our findings and offers concluding remarks, including observations on screening design, index methodology, and practical considerations for Islamic investors.

2. Literature Review

Existing research on Islamic equity markets clusters around three interconnected questions: first, whether Shariah-screened portfolios differ from conventional benchmarks in terms of performance; second, how major index providers translate broad Shariah principles into concrete business activity and financial ratios; and third, to what extent those screening choices shape portfolio behavior across market cycles. The following review follows this sequence, beginning with performance studies, moving to methodological analyses of screening rules, and ending with work that links specific rulebooks to observed return and volatility patterns, so that overlapping findings are grouped together rather than repeated.

2.1. Literature on Comparison of Islamic and Conventional Portfolios

Research consistently indicates that Islamic indices often exhibit lower volatility and comparable or superior risk-adjusted performance, especially during market downturns. For instance, studies have shown that indices like the Dow Jones Islamic Market Index (DJIM) and FTSE Shariah Index demonstrated resilience during financial crises, attributed to the exclusion of highly leveraged companies (

Al-Khazali et al., 2014).

Asutay et al. (

2022) offers a comprehensive performance comparison between Islamic and conventional stock indices across four major markets—worldwide, the US, Europe, and Asia–Pacific—over the period 2007–2017. Using financial ratio comparisons and the CAPM-EGARCH model, the authors found that Islamic indices yielded higher average returns and lower risks during the 2007–2009 and 2013–2017 periods for all four markets, compared with their respective conventional markets. During the 2009–2013 period, the comparison was inconclusive, with Islamic indices demonstrating better performance in European and Asia–Pacific markets, while conventional indices performed better in the other markets.

Back-testing and asset allocation methods have also been applied to Islamic indices. For example, authors find that the underperformance in booming markets is often linked to constraints that limit diversification (

Derigs & Marzban, 2008). Asset allocation strategies incorporating tactical adjustments, such as momentum-based or mean–variance optimizations, have been adapted for Islamic portfolios (

Abdelsalam et al., 2014).

Another line of studies tries to see if different weighting or timing can decrease the loss of diversification that Shariah screening brings.

Raza and Ashraf (

2019) indicate that equal-weight and low-risk portfolios beat the usual cap-weighted Shariah index in both return and drawdown.

Boudt et al. (

2019) obtain higher Sharpe by a Markov-switching model that adjusts monthly toward the style the macro cycle likes. In our work, we keep only the plain cap-weight vs. equal-weight check, so any performance gap comes from the screen itself, not from portfolio manipulations.

2.2. Literature on Divergence and the Need for Standardization in Islamic Market Indices

The rise in Islamic market indices has introduced a variety of screening methodologies, leading to inconsistencies in Shariah compliance criteria across different indices. This divergence poses challenges for investors seeking uniformity and clarity in Shariah-compliant investments.

Alnamlah et al. (

2022) develop the WASC framework, which delivers a continuous measure of compliance intensity rather than a binary “in/out” label. Their empirical application to US equities demonstrates that firms can be ranked along an ethically sensitive gradient, thereby enabling investors to tailor portfolios to their own moral thresholds. Integrating WASC into index construction could thus bridge the gap between divergent rulebooks and respond to broader calls within business ethics scholarship for more transparent, stakeholder-oriented metrics of corporate conduct.

Further emphasizing the need for harmonization,

Azizi Abu Bakar et al. (

2023) examine the screening methodologies of various index institutions. Their study reveals that while the differences in screening methods are not fundamentally rooted in Shariah principles, they stem from institutional preferences and interpretations. The authors advocate for a standardized screening methodology that balances scholarly consensus and practical applicability, which would enhance investor confidence and facilitate broader participation in Islamic capital markets.

Ashraf et al. (

2017) document that the cost or benefit of leverage and cash filters depends on whether ratios use book assets (MSCI method) or market capitalization (AAOIFI method), and that betas drop sharply in crises, findings that motivate our own drawdown checks.

Akartepe (

2022) critically dissects the threshold ratios that Shariah boards apply when screening listed companies, showing that the prevailing “minority–majority” approach, which treats thresholds as purely quantitative cut-offs, and the “necessity-centered” approach, which sets thresholds according to presumed market hardship, both suffer from methodological inconsistencies. Using a detailed review of global fatwa committees and the Indian market as a case study, the paper argues that thresholds should instead be anchored in empirically observed, sector-specific necessity levels and updated periodically; liquidity screens, by contrast, should follow classical juristic rules distinguishing cash-dominant from asset-dominant firms. The author proposes a “sectoral necessity” model that simultaneously honors Shariah objectives, minimizes arbitrary leniency, and preserves a sufficiently large investable universe for portfolio construction, thereby improving the coherence and credibility of Islamic equity screening.

Essayem and Görmüş (

2023) further argue that without unified standards, Islamic indices may underperform not due to underlying asset quality but due to inefficiencies in index construction, affecting investors’ perception of Islamic finance’s viability.

2.3. Literature on Comparison of Islamic Indices

Evaluations of Islamic indices such as DJIM, FTSE’s, MSCI’s, and S&P’s reveal variations in performance, screening methodologies, and sectoral focus. Authors find that the FTSE Shariah Index allows broader sector exposure and has shown robust returns in emerging markets, particularly in Asia and MENA regions (

Hayat & Kraeussl, 2011).

In Turkey, the Borsa Istanbul Participation Index (Participation 30) has attracted regional investors due to strong compliance with Islamic finance standards and its reflection of Turkish market dynamics. Beyond returns, tracking error and Sharpe ratios provide key insights. Some Islamic indices also integrate ESG screens, narrowing the gap between Islamic and ethical investing.

Ashraf and Khawaja (

2016) give the closest earlier test of rulebook differences; they found that book asset standards edge out market value standards up to 2013, but the gap was economically small. We revisit that debate a decade later and show that STOXX’s “higher-of-assets-or-cap” rule now ranks first, implying that the best screen may change with market regime.

2.4. Research Gaps in the Literature

Despite the growing body of literature on Islamic finance, notable gaps remain. While many studies have compared Islamic and conventional indices using metrics like Sharpe ratios, volatility, and average returns, few integrate comprehensive portfolio performance frameworks that evaluate both risk and return simultaneously using multi-dimensional measures. Most existing analyses rely on univariate metrics or simple risk-adjusted performance indicators, which may obscure nuanced insights about performance dynamics. This creates a gap in evaluating Islamic indices from a rigorous efficiency- and utility-based portfolio perspective. In our research, in addition to the Sharpe ratio, we also use the Treynor ratio, which uses beta as the risk metric from the portfolio point of view instead of evaluating each index separately. We also use Jensen’s alpha to evaluate the performance of the portfolio compared with the market index. Moreover, we construct the portfolios each quarter for each index criteria and evaluate performance cumulatively. This dynamic portfolio approach allows us to compare the performances of different Islamic criteria portfolios over a relatively long period of time.

The literature also lacks studies exploring seasonality effects in Islamic index returns. Given the unique screening constraints and sectoral allocations of Islamic indices, seasonal trends may manifest differently and offer exploitable inefficiencies or optimization opportunities for investors. Research could investigate whether certain Islamic indices outperform during specific periods. Bridging these research gaps would enhance academic understanding and provide practical insights for investors and portfolio managers.

3. Data and Methodology

First, we retrieve price, long-term debt, market capitalization, total debt to total assets, short- and long-term debt, total assets, cash and cash equivalents, short-term investments, and accounts receivables data on a quarterly basis from 2019 to 2023, covering 20 quarters of S&P 500 companies. Since historical changes in the set of members of the S&P 500 index are not available, we gathered the members as of 7 January 2025. After taking data availability into account, we ended up covering 482 stocks out of the S&P 500 companies. We assume that these are the S&P 500 companies from 2019 to 2023. The choice of limiting the sample by 20 quarters comes from the continuity requirement of the S&P 500 constituents to allow consistent performance comparison throughout the sample period.

We then determined the most widely recognized Islamic indices in global practice. They are as follows:

The Dow Jones Islamic Market Indices (“DJIMI”);

The Kuala Lumpur Syariah Index (“KLSI”);

The FTSE Global Equity Shariah Index Series (“FTSE”);

The MSCI Islamic Index Series (“MSCI”);

The STOXX Europe Islamic 50 Index (“STOXX”).

Then, we specified the business activity-based and accounting-based screens of these Islamic indices. The business activity-based screens of the indices are given comparatively in

Table 1.

Table 1 illustrates the principal non-compliant activities for each index, in which each index applies specific tolerance thresholds to these non-permissible activities. For instance, for DJIMI, revenues from non-compliant activities are tolerated within

(

S&P Global, 2024). KLSI applies a

benchmark to all non-compliant activities, except for hotel and resort operations, share trading, stockbroking businesses, and rental received from Shariah non-compliant activities, where a

benchmark is applied instead (

Bursa Malaysia, 2024). Meanwhile, FTSE applies no tolerance for revenue derived from any prohibited activities (

FTSE Russell, 2024). MSCI excludes companies that derive more than

of their total revenue (cumulatively) from prohibited activities (

MSCI, 2024). Finally, STOXX excludes companies with significant involvement (more than

of their total revenue) in these non-compliant sectors (

STOXX, 2024).

Accounting-based screens of the indices are summarized in

Table 2. All five indices specify leverage, liquidity, and impure income levels, but their definitions vary. Recall that if providing banking services involves any riba-based transaction, then it is prohibited by Shariah (

AAOIFI, 2015). As

Ayedh et al. (

2019) point out, the riba-related activities of a company can be in the form of investment in conventional instruments and acquiring funds through interest-based facilities.

DJIMI measures interest-bearing debt against average market cap, while KLSI, FTSE, and MSCI divide conventional debt by total assets; STOXX uses the higher of assets or market cap, with a uniform 33% limit. For liquidity, KLSI restricts conventional cash to <33% of assets; FTSE and MSCI cap cash plus interest-bearing items at 33% of assets (FTSE also limits cash + receivables to 50%); STOXX again applies its 33% higher-of rule. Finally, every index adopts the classical purity test, requiring total interest and other non-compliant income to remain below 5% of revenue (

S&P Global, 2024;

Bursa Malaysia, 2024;

FTSE Russell, 2024;

MSCI, 2024;

STOXX, 2024).

For each quarter between 2019 and 2023, we computed the required leverage, liquidity, and receivables ratios from the relevant financials and applied each provider’s thresholds. Passing constituents formed equally weighted and market-cap-weighted portfolios that were updated quarterly; EW and MCW S&P 500 portfolios were used as benchmarks.

For further investigation, we calculated additional performance metrics beyond simple cumulative returns. Specifically, to assess which Islamic index outperforms the other ones on a risk-adjusted basis, we use measures from modern portfolio theory. One such measure is the Sharpe ratio, which evaluates how well a portfolio’s returns compensate for the overall risk taken (

Sharpe, 1994). It is calculated by subtracting the risk-free rate from the portfolio’s average return and then dividing by the standard deviation of the portfolio’s returns, as follows:

where

is the portfolio’s average return at time

,

is the risk-free rate at time

, and

is the standard deviation of the portfolio’s return. A higher Sharpe ratio means the portfolio delivers more extra return compared with its total volatility.

On the other hand, the Treynor ratio looks at a portfolio’s extra return relative to its market risk, which is given by the portfolio’s beta as follows (

Treynor, 1965):

where

is the portfolio’s average return at time

,

is the risk-free rate at time

, and

is the portfolio beta. A higher Treynor Ratio shows the portfolio earns more excess return for each unit of systematic risk.

Lastly, Jensen’s alpha measures a portfolio’s performance versus the return that is expected from its own systematic risk (

Jensen, 1968). Specifically, it is rooted in the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), which predicts that a portfolio’s expected return should be as follows:

where

is the portfolio return,

s the risk-free rate,

is the market return, and

is the portfolio’s market (systematic) risk. Jensen’s alpha (

) is then calculated as follows:

A positive Jensen’s alpha indicates that the portfolio has outperformed its theoretical expected return given its market risk, while a negative Jensen’s alpha suggests underperformance relative to the market-based expectation.

4. Results

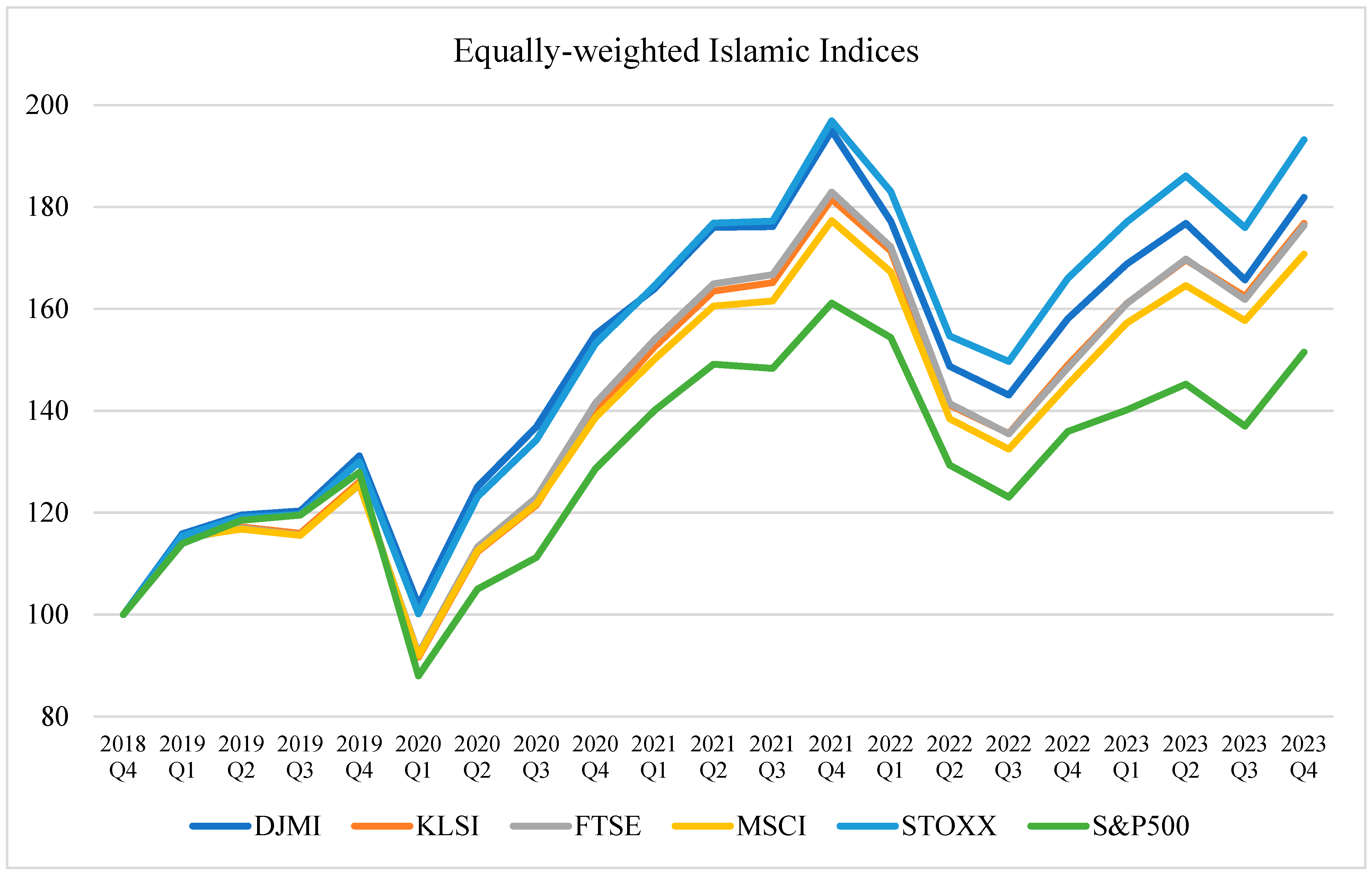

Under the equally weighted approach, all indices exhibit considerable growth from the baseline set at 2018 Q4. By 2023 Q4, STOXX stands out with the highest cumulative index level (193.21), followed by DJMI (181.88). In

Table 3, mean and standard deviation values of all these indices are given in addition to those of the S&P 500 and a portfolio named Tech, that contains only companies whose industry is technology according to the Bloomberg Industry Classification System, and a portfolio named Non-Tech, that contains only companies whose industry is not technology according to the Bloomberg Industry Classification. As can be seen from the figures provided, average returns are distributed around zero. The major decline in 2020-Q1 reflects the global market recession followed by strong recoveries in 2022-Q2 and 2022-Q4. Islamic indices display lower variability than conventional counterparts. The technology portfolio shows higher average returns but also greater volatility, while the Non-Tech portfolio mimics the broad market’s steady behavior.

Table 4 shows

p-values generated using

t-tests (unequal variances) applied to see if there are significant differences between the quarterly time series of Tech and Non-Tech portfolio daily returns. There is no single quarter in which a portfolio significantly differs from the other. This can be taken as evidence that the outperformance of the Islamic stock exchanges is not mainly caused by the involvement of Technology stocks in the Islamic portfolios.

Furthermore, the equally weighted S&P 500 reaches 151.52, indicating that it underperforms relative to all Islamic indices over the same period. These results suggest that, under certain market conditions, Shariah-compliant approaches may deliver higher compounded growth rates than the broader market, even when weighting each component equally rather than by market capitalization (

Figure 1). This dominance of STOXX contrasts with

Ashraf (

2016), where MSCI and FTSE, both book asset screens, had the edge.

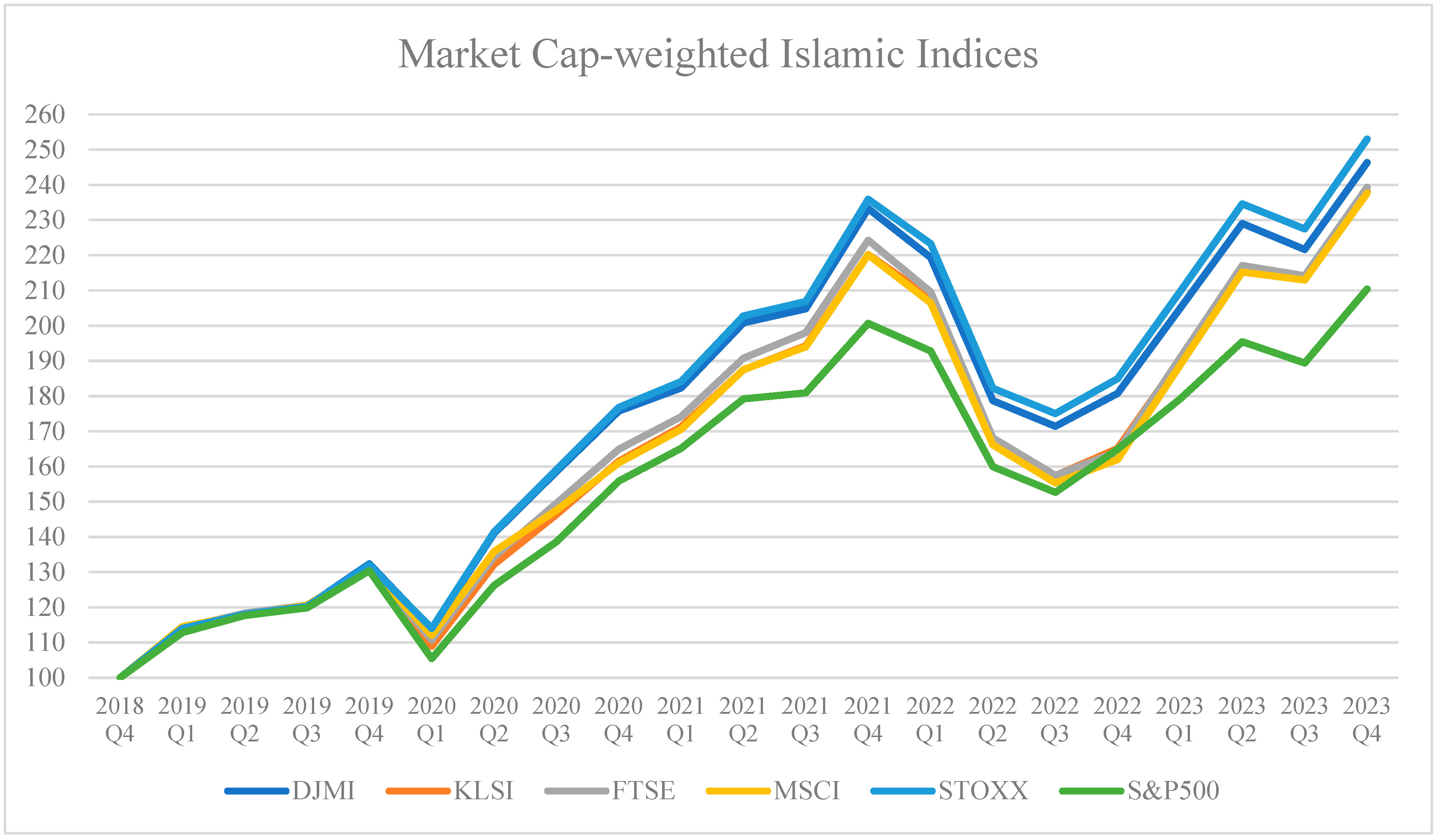

In

Figure 2, from the baseline set at 2018 Q4 to 2023 Q4, all five Shariah-compliant indices and the S&P 500 again show a substantial increase, indicating positive cumulative returns over the sample period. Among the Islamic indices, STOXX exhibits the highest ending value (253.01), suggesting it outperformed the other Shariah-compliant indices when measured on a market-cap-weighted basis. While the S&P 500 (210.46) also performed well, it did not reach the same level as STOXX or some of the other Islamic indices by the end of 2023 Q4, highlighting the potential for certain Shariah-screened portfolios to surpass conventional benchmarks under specific market conditions.

A deeper review of the back-testing figures reveals the consistent superiority of market-cap-weighted indices over equally weighted counterparts. While both weighting schemes show that STOXX and DJIMI outperform the S&P 500, the differences are more pronounced in the market-cap portfolios.

Figure 2 shows that STOXX’s market-cap-weighted portfolio ends the period with a cumulative value of 253.01, compared to 210.46 for the S&P 500. Meanwhile, in equally weighted form, STOXX achieves 193.21 and DJIMI 181.88, still leading but with narrower margins (

Figure 1).

Portfolio Performance Measures for Islamic Indices

Across 2019–2023, STOXX and DJIMI exhibit comparatively higher Sharpe ratios in many quarters (e.g., 2019 Q1, 2019 Q4, 2020 Q3–Q4, 2021 Q2). KLSI and FTSE often record moderate but less volatile Sharpe ratios; MSCI shows mixed results, occasionally matching peers (e.g., 2019 Q4, 2021 Q2). Negative spikes occur in 2023 Q3 for all indices, with FTSE showing the largest drop (−48.50), suggesting heightened risk relative to return during that quarter. STOXX leads to the highest quarterly peaks more frequently, while DJIMI remains competitive, indicating that these two indices typically outperform on a risk-adjusted basis among equally weighted portfolios (

Table 5).

The pattern matches

Raza and Ashraf (

2019), who report that equal-weight smart beta portfolios give the highest Sharpe ratios inside Shariah universes; here, the equal-weight STOXX variant posts the best five-year average (6.47).

STOXX and DJIMI often record stronger Sharpe ratios (e.g., 2019 Q4, 2020 Q2–Q3, 2020 Q4) relative to KLSI, FTSE, and MSCI. STOXX frequently posts higher values but also shows pronounced negative swings (e.g., 2023 Q3, −57.51). STOXX and DJIMI dominate average Sharpe ratios, indicating these two market-cap-weighted Shariah portfolios commonly deliver higher excess return per unit of total volatility (

Table 5).

DJIMI and STOXX show marginally higher Treynor ratios across many quarters (e.g., 2019 Q1, 2020 Q2, 2020 Q4), though differences among the five indices are narrower than in Sharpe ratios. All indices dip into negative territory during market downturns (e.g., 2020 Q1, 2022 Q1–Q3, 2023 Q3), but the magnitude of declines varies modestly. STOXX edges out DJIMI in more intervals with slightly higher Treynor values, suggesting it generally earns superior excess returns per unit of market (systematic) risk among the equally weighted set (

Table 6).

DJIMI and STOXX again appear at or near the top in positive quarters (e.g., 2020 Q2, 2020 Q3). Negative values occur uniformly during downturns, but STOXX exhibits some of the largest negative swings (e.g., 2023 Q3), consistent with its higher beta exposure in certain periods. Although KLSI and FTSE post comparable Treynor ratios to DJIMI in certain quarters (e.g., 2023 Q2), STOXX still shows the best overall excess returns against systematic risk in the majority of positive-return quarters (

Table 7).

DJIMI and STOXX exhibit slightly more positive alphas (e.g., 2020 Q2–Q4, 2022 Q4), though the differences among indices remain modest. Overall, alpha values across DJIMI, KLSI, FTSE, MSCI, and STOXX remain close, suggesting none strongly outperforms or underperforms CAPM-based predictions on an equally weighted basis (

Table 8).

DJIMI and STOXX occasionally achieve positive alphas (e.g., 2020 Q1–Q2, 2023 Q1–Q2). KLSI, FTSE, and MSCI frequently record near-zero or slightly negative alphas (e.g., 2019 Q1–Q2, 2020 Q4, 2021 Q1–Q2, 2022 Q4), reflecting returns close to their CAPM expectations. STOXX and DJIMI generate marginally higher alphas more consistently than others, but overall alpha levels remain subdued, indicating only modest deviations from expected CAPM returns among all Shariah indices (

Table 9). Such muted alphas echo the “no-free-lunch” result in

Ashraf and Khawaja (

2016) and confirm that Shariah screens alone, without additional factor tilts, seldom generate persistent excess return.

Furthermore, as can be seen in

Table 10, Jensen’s alpha ratios for the market-cap-weighted indices are small and tightly clustered around zero, with five-year average daily alphas ranging from 0.00021 (KLSI) to 0.00028 (STOXX). STOXX attains the highest alpha in many quarters (notably 2020 Q1–Q4, 2021 Q2, 2021 Q4, 2022 Q2–Q4) and rarely ranks last. Overall, the pattern suggests that abnormal performance is modest for all five indices, with STOXX showing the most persistent advantage.

Overall, STOXX and DJIMI most frequently show higher Sharpe and Treynor ratios, suggesting stronger excess returns relative to both total and systematic risk. All indices exhibit relatively small alpha magnitudes, but DJIMI and STOXX are slightly more likely to post positive values. STOXX demonstrates a marginal edge in many quarters, with DJIMI closely trailing, signaling that these two indices tend to outperform the others on a risk-adjusted basis across the sample period.

Sharpe ratios in

Table 5 and

Table 6 confirm that market-cap portfolios of STOXX and DJIMI consistently post stronger average values—12.12 for STOXX—compared to 6.47 in the equally weighted set. This pattern persists across Treynor and Jensen’s alpha ratios as well, with market-cap-weighted STOXX outperforming more frequently and with higher magnitude. These results suggest that investors may capture more consistent excess returns by aligning with market-cap-weighted structures, particularly those using strict Shariah filters like STOXX.

These comprehensive results underscore the effectiveness of conservative Shariah screening methodologies in reducing downside risk while preserving upside potential.

5. Discussion

In this research, we compared the performances of five portfolios constructed according to the Shariah rulebooks of five major Islamic indexes by covering a single dataset of the S&P 500. This approach allowed us to compare the differences between various criteria of the Islamic indexes. We constructed our portfolios dynamically for 20 quarters and evaluated their cumulative return performance. In addition, we applied portfolio performance measures, Sharpe, Treynor, and Jensen’s alpha, to each portfolio for each quarter. Our results confirm that there are important differences between the Shariah criteria of major Islamic indexes, which cause differing performances from cumulative return and risk–return perspectives. We suggest that Shariah screening criteria should be unified around the world for Islamic investors.

Consistent with prior research, our results confirm that Shariah-compliant indices generally match or outperform conventional benchmarks on a risk-adjusted basis (

Al-Khazali et al., 2014;

Asutay et al., 2022). Many studies report that major Islamic indices tend to have lower volatility and comparable or superior Sharpe-type performance, especially during crises. For example,

Al-Khazali et al. (

2014) document that indices like DJIM and FTSE Shariah held up well in downturns, and

Asutay et al. (

2022) similarly find higher average returns with lower risk for Islamic indices across multiple markets. In short, the literature supports the view that applying Shariah screens need not sacrifice efficiency and may even enhance resilience in turbulent markets.

In our fixed S&P 500 universe, the STOXX Europe Islamic 50 Index emerges as the top performer on every risk-adjusted metric, which reverses the findings of

Ashraf et al. (

2017), who found a return penalty for similarly strict book asset screens before 2013. STOXX posted the highest Sharpe, Treynor, and Jensen’s alpha among the evaluated indices. Importantly, STOXX’s edge came from its steadier returns—it “suffered fewer big drops and gathered lots of small positive days”—rather than from unusually large raw gains. This reflects STOXX’s stringent screening rules: for instance, it applies a uniform 33% cap on leverage (using the larger of market cap or asset base) and similarly tight cash/liquidity limits. By contrast, DJIMI, KLSI, FTSE, and MSCI use alternative filters (e.g., DJIMI measures debt against average market cap, while the others use debt-to-asset ratios). Those looser criteria yield a less conservative portfolio mix. In our backtests, the STOXX portfolio’s conservative construction translated into superior excess returns per unit of risk. The main reason of the difference from

Ashraf et al. (

2017) is that we use the rulebook of the STOXX Europe Islamic 50 Index to choose a portfolio from S&P 500 stocks, whereas

Ashraf et al. (

2017) evaluate the performance of European Islamic stocks.

Seasonal patterns also stand out in the comparative results. During severe market sell-offs (e.g., 2020 Q1 and parts of 2022), all indices dropped, but STOXX limited its losses more effectively than its peers. In contrast, DJIMI tended to capture the bulk of the rebound that followed. In other words, DJIMI’s portfolio often earned higher excess returns in strong recovery phases, whereas STOXX’s conservative screens preserved capital when volatility spiked. In short, STOXX leads in high-risk periods while DJIMI shines in rebound periods. The stricter criteria for choosing the STOXX portfolio makes it a defensive one with lower volatility and better diversification. On the other hand, the looser criteria for choosing the DJIMI portfolio makes it a high-risk, high-return portfolio. This suggests an “index timing” insight: blending multiple Islamic indices could allow investors to harness DJIMI’s upside in rallies and STOXX’s stability in downturns. Additionally, across almost all measures, market-cap-weighted portfolios—particularly those based on STOXX and DJIMI—outperformed their equally weighted versions, offering more favorable risk-adjusted returns. This finding implies that weighting methodology interacts significantly with Shariah screening and should be an active consideration for practitioners and product designers.

Our findings also highlight a critical issue: screening inconsistencies across Islamic indices. Existing studies (

Azizi Abu Bakar et al., 2023;

Akartepe, 2022) document that indices employ divergent Shariah rules, leading to inconsistent constituents.

Azizi Abu Bakar et al. (

2023) emphasize that such differences arise from index providers’ conventions rather than core Islamic principles, and they call for a harmonized, standardized rule set. Similarly,

Akartepe (

2022) criticizes fixed-percentage screens as arbitrary, advocating data-driven, context-specific thresholds. In sum, without a unified, transparent Shariah compliance framework, investors face confusion and indices risk appearing as a fragmented patchwork. While

Raza and Ashraf (

2019) and

Boudt et al. (

2019) rely on smart weights or style rotation to improve performance, our evidence shows that simply choosing the STOXX screen achieves a comparable Sharpe uplift with a low-turnover, vanilla weighting scheme.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. We constructed all indices with quarterly updates over 2019–2023 using a fixed list of S&P500 members (as of January 2025). This creates unavoidable survivorship bias (excluding delisted or newly listed firms) and ignores changes in index composition over time. It is also the reason for not having a longer timeframe. Our use of quarterly data also smooths intraperiod fluctuations, so the results primarily reflect medium-term trends rather than short-term volatility. We also applied five major Shariah indexes’ rulebooks in our portfolio selection from S&P500 stocks. Thus, our conclusions are conditional on these choices of frequency and universe.

Looking ahead, future research could extend this work in various directions. One obvious extension is to experiment with alternative weighting schemes. For instance, applying time-decay weights or logarithmic weighting to index constituents would emphasize recent performance or de-emphasize large-cap bias, potentially yielding different risk–return dynamics. Although most local Islamic indexes are derived from the rules of these major indexes, adding the criteria of Islamic indexes from other stock exchanges into the comparison could be another further research topic. Moreover, checking the relationship between various factors, such as Sharia debt/market value and the performance of Islamic portfolios, could be a topic for further study. Another avenue is to analyze investor portfolio choice among Islamic indices. Using a Markowitz mean–variance optimization (or similar framework), one could investigate how rational investors would allocate across STOXX, DJIMI, and other indices, and whether a combined strategy outperforms any single index. Such analyses would offer deeper insight into the practical implications of index selection and portfolio construction in Islamic equity markets.