Abstract

The present study examines the relationship between economic growth and the tax burden that is formed as a result of income taxes. The main goal is to verify whether there is a link between these research variables in the long run and if this is confirmed, to analyze the manner in which these processes interact. The research applies a range of econometric techniques, including stationary tests, pairwise Granger causality test, Johansen cointegration test, impulse functions, and variance decompositions in order to investigate causality in the short- and long-term. The study is based on 49 observations and covers four European Union (EU) member states (Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania, and Estonia), which continue to impose a proportional (flat) tax on personal and corporate income. The analysis relies on quarterly data for the period 2013Q1–2025Q1. The results obtained are quite heterogeneous, which can be explained by the significant differences in the tax policy pursued, as well as by a number of other features determining the growth of national economies.

1. Introduction

In the scientific literature, it is a common practice to analyze the relationship between taxation and economic development, including the achievement of economic growth, as a subject of research. A number of authors over the past two centuries have argued that taxes have specific effects on the ability to achieve higher growth, or to attain any growth at all. The topic is extremely relevant today. The analysis often focuses on the reverse effect, in particular—to examine the extent to which economic development and achieved economic growth can contribute to increasing tax efficiency, as well as to providing additional revenue from taxes that is applicable in national legislation. This is of fundamental importance, especially in recent years after the emergence of COVID-19, and above all in the search for mechanisms to increase fiscal sustainability (Cornevin et al., 2024). Undoubtedly, a wide range of research on these topics can be outlined, in both contemporary and earlier studies. Nevertheless, it is important to start from the beginning, to establish whether there is any connection and causality between these processes, and only then can real effects, their strength, and direction of action be identified.

The majority of contemporary research investigates the interaction of taxes and growth in a broader context. These studies usually take into account the total tax burden and analyze its effects on economic growth. The number of articles that emphasize the tax burden of individual components of the tax system is quite limited.

To summarize the above, the present study aims specifically to shift the main focus of interaction. The object of this research is, on the one hand, the tax burden generated by income taxes, and on the other hand, the growth of national economies. The subject of the study is an examination of the relationship and causality between the burden of income taxes and economic growth. The main purpose is to establish whether such a link exists between these individual components, including in the long- and short-term, and if this is confirmed, to be able to trace its direction, strength of impact, and expected effects. The scope of the study includes EU member states that apply proportional income taxation. The key reasons for this choice are related to determining the accuracy of the widespread assumption that proportional income taxation with a lower marginal tax rate can be beneficial, and that it is a tool through which the state can contribute to achieving not only fiscal, but also a number of other macroeconomic goals, such as the growth of its national economy (Cassou & Lansing, 1996; González-Torrabadella & Pijoan-Mas, 2006; Hlavac, 2008; Majcen et al., 2009; Adhikari & Alm, 2013; Vasilev, 2015, etc.). The main hypothesis underlying this study is that the tax burden arising from income taxation can serve as a significant tool to influence the opportunities for stimulating economic growth, but at the same time, the reverse effect is also possible.

The structure of the present study is as follows: Section 2 presents a literature review focused on an examination of the relationship between direct taxes and economic growth; Section 3 provides information on the main countries included in the analysis, the historical aspects of the reform of their income tax systems, and their transition to proportional income taxation; Section 4 introduces the methodological framework of the current research; Section 5 contains the results of the applied methods in assessing the link between the variables under investigation; Section 6 presents a discussion of the results, including the relationship between the findings obtained in the present study and the connections and dependencies established by previous authors; Section 7 is a conclusion.

2. Literature Review

A comprehensive analysis of the theoretical and empirical literature shows that it is difficult to establish a generally accepted opinion on the existence of a relationship between personal and corporate income taxes and the growth of national economies. Previous research on these topics can be distinguished by the following more specific aspects:

- The methodology applied—One group of studies uses a single method of assessment, while other papers conduct tests adopting multiple approaches, sometimes forming different conclusions within the same study. It is worth noting that the majority of the research under consideration evaluates the existence of a linear relationship between income taxes and economic growth, but at the same time, there are studies in which the presence of nonlinearity between the variables is also the subject of analysis. Occasionally, the assessment of the existence of a relationship between taxes and growth is complemented by an examination of the effect of one variable on the other, and conversely.

- The time period covered by the study—Some studies focus only on establishing the relationship in the short-term, in others, the analysis is on the long-term dependence, and in a third group, the evaluation is in both the short- and long-term.

- The territorial scope of the study—Most research covers the examination of the association between variables in the context of a single economy (national), but nevertheless, there are also articles that encompass a group of countries (e.g., Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, European Union (EU), Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), etc.).

- The data frequency—Possible approaches in this regard are the use of annual and quarterly data, where it is common practice to base the analysis on long time series exceeding 40 observations.

- Variables under analysis—Appropriate options from this perspective are, on the one hand, to place emphasis only on income taxes and growth, and on the other hand, to determine the relationship between them in light of a broader scope of analysis, such as considering the entire tax structure, assessing the effects of all direct taxes (not only income taxes), including other non-tax (macroeconomic) components, etc. Another significant feature is that there are differences in the type of factors used, including whether real or nominal variables are considered and whether the indicators are in the form of coefficients or ratios.

In the context of the first specific aspect mentioned above, in particular the methodology used, testing of the relationship between taxes and economic growth is usually carried out through the Søren Johansen (1991) test in the long run. In parallel, the search for causality most often relies on the application of Clive Granger’s (1969) test. Helhel and Demir (2012), for example, established, through the Johansen test, a long-term relationship between the tax burden of direct taxes and economic growth in Turkey for the period of 1975–2011. Furthermore, the authors applied the Granger test in order to determine whether there was a causal link between direct taxes and growth. The result of the Granger test did not confirm the existence of such a causal relationship, either between taxes and growth or vice versa. The established long-term dependence of the Turkish economy allows for an additional vector error correction model, combined with impulse response functions and variance decomposition to identify the impact of direct taxes on growth. As a result, the outcomes showed that a possible increase in direct taxes can provoke a decline in GDP in the short-term, followed by a partial recovery, but the effect nevertheless remains negative. Mucuk and Alptekin (2008) carried out an earlier study on this topic, again using the Johansen and Granger test in the context of the Turkish economy. The analyzed period was similar (1975–2006), and they once again confirmed a long-run relationship between direct taxes (% of GDP) and growth. Unlike the study by Helhel and Demir (2012), Mucuk and Alptekin (2008) succeeded in establishing a unidirectional causal link from direct taxes to growth through the Granger test. Moreover, the impact of direct taxes on growth was further examined and the results suggested that direct taxes had a negative influence on the development of the Turkish economy within the research period. Shanmugam and Arunima (2021) also determined, through the Johansen test, a long-run relationship between direct taxes and growth in Puducherry (India) for the period of 2007–2019, but when applying the Granger test, there was, again, no evidence of a causal link between the variables.

Tanchev (2021) also affirmed through the Johansen test that a long-run relationship between personal income tax and economic growth existed in Bulgaria for the period of 1999 Q1–2020 Q1. A characteristic feature of this research is that within the analyzed period, a change occurred in the type of income tax applied to individuals in Bulgaria, as until the end of 2007, the tax was progressive, and from the beginning of 2008 it was proportional. Regardless of the tax reform carried out in the country, a long-term link between PIT and economic growth was confirmed during the two separate sub-periods, and by using VECM it was proven that the impact of the tax on growth in the long run was negative, while in the short run no influence was found, as well as that “a progressive tax is more compatible with economic growth than a proportional tax”.

A study by Arikan and Yalcin (2013), based on quarterly data for the period of 2004 Q1–2012 Q1 for the Turkish economy, also found a long-term association between direct taxes and economic growth. In particular, this was valid for personal income tax and real GDP, but it was not applicable to corporate income tax and real GDP. Similarly to the studies discussed above, there was no evidence of the existence of a causal link from direct taxes to economic growth, but on the other hand, there was a reverse Granger causality—from economic growth to direct taxes. It is worth noting that tests specifically for income taxes showed the reverse causality, specifically, from personal income tax to real GDP, while there was no such relationship in the opposite direction. Kimani (2021), applying the Granger test to Kenya for the period of 1989–2019, also reached a similar result for the causality between income taxes (including both the tax withheld from personal income—pay as you earn (PAYE)—and the tax withheld from corporate income (CIT)) and economic growth.

In the context of analyzing the link between tax structure and economic growth, Stoilova (2023) implemented the Granger causality test for twelve countries from Central and Eastern Europe (Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia) and also found no association between personal income tax (% of GDP) and real economic growth, nor between corporate income tax (% of GDP) and real economic growth. In another study, Stoilova (2024) tested this causality for all EU member states and again the results showed that no similar connection could be established between these two income taxes and the growth of national economies. In both studies, the author developed and presented findings from regression models, which demonstrated that there was a positive (but not strong) correlation between direct and corporate tax revenues, on the one hand, and economic growth, on the other. Tiwari (2012) also found a lack of causality between the tax burden of the two income taxes and growth in the US economy over the period of 1947 Q1–2009 Q3. Unlike most studies that seek causality through the classic Granger test, Tiwari (2012) adopted the approach of Breitung and Candelon (2006), which allowed that study to not only assess the presence of a causal relationship between the variables under study, but also to analyze this effect within the business cycle and, in particular, in the short-term (high frequencies), medium-term (medium frequencies), or long-term (low frequencies) period.

Eren et al. (2018) and Songur and Yüksel (2018) also applied the frequency domain causality test of Breitung and Candelon (2006) to the tax system of the Turkish economy. Eren et al. (2018) established only unidirectional causality from direct taxes to the country’s potential for economic development. In contrast, the causality identified by Songur & Yüksel was bidirectional, both in the short- and long-term, and furthermore, a bidirectional causality between GDP and personal income tax revenues was also found. Although part of Songur & Yüksel’s analysis also included an examination of the link between corporate income tax and growth, the Breitung and Candelon (2006) test was not applied, as the lack of a long-run association between the variables was previously established through the Johansen test. It is noteworthy that Songur and Yüksel (2018) used a wide range of methods to analyze causality and long-term dependencies. For example, the researchers applied not only the test by Breitung and Candelon (2006) but also the classical Granger test, which demonstrated that GDP influenced direct taxes and personal income tax, and that direct taxes affected economic growth, but at the same time they rejected the causality from direct and corporate income tax to growth, as well as from growth to corporate income tax. Another important point in the study is the use of the test of Toda and Yamamoto (1995), which is an extension of the classical Granger test but also an econometric procedure that allows the robust analysis of causal relationships in non-stationary data (unlike the Granger causality test and the frequency domain causality test by Breitung and Candelon (2006)) and cointegrated series without initial differentiation. The results of both tests are similar, with the difference that the Toda–Yamamoto test confirms a causal link from personal income tax to Turkey’s economic growth in the period of 1980–2015. Similar findings also appear in Terzi and Yurtkuran (2016), who use both the Toda–Yamamoto test and the Unrestricted Vector Autoregression (U-VAR) model (Sims, 1980), characterized by the fact that each variable functions as endogenous and depends on its own lags and the lags of the other variable. The authors establish a bidirectional causal relationship between the direct taxes applicable in Turkey and the growth of the national economy, determining that direct taxes negatively affect the prospects for national economic expansion, while growth has a rather positive effect on the revenues generated from direct taxes. A more recent study (Karabacak & Meçik, 2022) of the causality between direct taxes (% of total tax revenues) and GDP per capita as a measure of growth in Turkey, again based on the Toda–Yamamoto test, found no evidence of such a dependency in either direction. A further in-depth study, which also relied on a causality test between income taxes and economic growth using the Toda–Yamamoto model, was created by Saafi et al. (2017). The assessment covered 23 member countries of the Organization for economic cooperation and development, with a focus on the possibility of personal income tax and corporate tax having an impact on macroeconomic processes in the countries, as well as the growth of the economies as a factor that influences the level of revenue collected from the analyzed taxes. The results showed that only 3 out of 22 countries (no data available for Portugal) demonstrated a unidirectional causality established from personal income tax to GDP (Luxembourg, The Netherlands, and Ireland), and in 5 countries there was a unidirectional causality from GDP to personal income tax (Austria, Germany, Ireland, Japan, and the USA). A bidirectional causality between GDP and PIT existed only in Turkey. When testing the relationship between corporate income tax and growth, the analysis identified that only 2 out of 22 countries (Sweden and Switzerland) had a unidirectional causality from CIT to GDP, and 9 countries (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, and the United Kingdom) had a unidirectional causality from GDP to CIT. Bidirectional causality between corporate tax revenues and growth appeared in only five of the analyzed countries (The Netherlands, Denmark, Finland, Greece, and New Zealand).

Maganya (2020) used the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model to examine the short- and long-run relationships between GDP per capita as a measure of economic growth and a set of variables, including income tax revenue, for the Tanzanian economy. The study period was 1996–2019, and the results showed the existence of a long-term link in which income taxes suppressed growth. Muduli and Manik (2020) reached the same result by applying a panel autoregressive distributed lag (PARDL) model to fourteen Indian states over the period of 1980–2016, testing the long-term effects of state’s own direct tax revenue on nominal gross state domestic product and gross state domestic product per capita. It is important to highlight that in the study by Maganya (2020), the results of implementing the Granger test showed that there was no causality between income taxes and economic growth. Using an ARDL model, Nayak et al. (2022) found that there was a long-run relationship between direct taxes and economic growth in India over a period of about 50 years (1970–2021). Unlike the outcomes specific to the Tanzanian economy, the analysis by Nayak et al. (2022) suggested that direct taxes positively affect economic growth in the long run (with ARDL). The results are further supported by an additionally tested multiple regression model, which confirmed the strong positive impact of both personal and corporate income taxes. Once again, the Granger test showed that there was no causality from direct taxes to growth. At a significance level of 10%, it is assumed that there may be a causal relationship from economic growth to direct taxes. In their research, Mashkoor et al. (2010) also applied the ARDL model in order to check whether there was a long-run link between direct taxes (including personal income tax, corporate income tax, property tax, and gift tax) and economic growth in Pakistan during the period of 1973–2008. The analysis verified the existence of such a dependence and confirmed causality from direct taxes (as % of GDP and as a % of total tax revenues) to economic growth.

There are also studies, such as the one by Abdiyeva and Baygonuşova (2016), that have reached divergent conclusions, in particular that no relationship between direct taxes (including personal income tax, corporate income tax, and property tax) and growth emerges in the long run, although the Granger test showed causality. Actually, the results allow researchers to argue that there is such a causal relationship from direct taxes to economic growth. Due to the fact that the Johansen test rejected the existence of cointegration, the authors used a vector autoregression (VAR) model, the results of which suggest that direct taxes have a rather negative effect on the value of GDP, and therefore on growth. Applying the Johansen test to the Romanian economy in the study by Bâzgan (2018) also led to the conclusion that for the period of 2009 Q2–2017 Q2, no long-term relationship can be established between direct taxes (% of GDP) and the growth rate. The subsequently used VAR model shows that the tax structure is decisive, and direct taxes have a considerably weaker effect on growth compared to the effects generated by indirect taxes. Similar findings on the effects of direct and indirect taxes on growth also occurred in Petru-Ovidiu (2015) for the period of 1995–2012 for six Eastern European countries (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Romania, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia), as well as in Angelov and Nikolova (2021) for the Balkan region (including Bulgaria, Romania, Cyprus, Greece, Croatia, Slovenia, North Macedonia, Turkey, Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo and Montenegro) for the period 2005–2018. Both studies emphasized the significantly more negative effect of direct taxes on growth and more favourable influence characteristic of indirect taxes on growth. Anastassiou and Dritsaki (2005) examined the existence of a relationship between the rate of economic growth and tax revenues in another Balkan country—Greece—for the period of 1965–2002, with the outcomes of the Johansen test indicating that there was a long-run cointegration link between direct taxes and economic growth, although the integration at a later stage of the vector error correction model (VECM) challenged the stability of this long-run relationship. Based on the Granger test, the causality was unidirectional—from direct taxes to the growth rate of the Greek economy. Odum et al. (2018), also using the Granger and Johansen tests (combined with VECM), supported the presence of a long-run direct relationship and causality between direct taxes and growth in Nigeria for the period of 2007–2016, but it is essential to highlight that while a unidirectional causality was observed in Greece, in Nigeria there was a bidirectional association between tax revenues and GDP. Yildiz and Sandalci (2019) further concluded that there was a bidirectional causality between direct taxes (per capita) for 81 provinces in Turkey as a result of applying the Granger’s (1969) test and Dumitrescu and Hurlin (2012) test.

Compared to the studies discussed above, which focus on establishing cointegration and linear relationships, the specific scientific literature also includes articles whose object of analysis is the investigation of nonlinear causality between taxes and economic growth. Following this, Karagianni et al. (2012) aimed to determine to what extent the tax burden of certain type of taxes in the United States, such as personal and corporate income taxes, can contribute to achieving a higher GDP per capita in the period of 1948 Q1–2008 Q4. For this purpose, the authors applied two causality tests—the modified Baek and Brock nonlinear causality test proposed by Hiemstra and Jones (1994) and the nonparametric test for Granger non-causality by Diks and Panchenko (2006)—both of which concluded that there was a nonlinear causal relationship between the tax burden of corporate income tax and GDP per capita. Simultaneously, the modified Baek and Brock nonlinear causality test further confirmed such a causality in terms of the tax burden of personal income tax on growth, while the Diks & Panchenko test did not establish this kind of dependency. Within a similar timeframe (1947 Q1–2009 Q3) Tiwari and Mutascu (2014) also managed to prove nonlinear causality from personal income tax to economic growth in the US, and meanwhile, based on classical linear causality tests, they concluded that such causality does not exist, either between personal income tax and growth or between corporate income tax and growth.

3. Data

The current study examines the relationship between economic growth and tax burden through two variables.

The representation of tax burden uses the taxes on the incomes of individuals, households, corporations, and NPIs—group D.51 taxes on income in accordance with the methodology of Eurostat (2013). Income taxes constitute the largest relative share of all direct taxes, and it is entirely reasonable to use them as a basis for analyzing interrelationships with other macroeconomic variables. This paper measures the tax burden (variable TAX) as the ratio of revenue collected from income taxes to GDP.

Due to the fact that the object of the study is to examine the existence of a relationship between the tax burden of direct taxes and economic growth in countries with proportional income taxation in the EU, it is of particular importance to analyze the tax systems in the EU and to outline the countries that apply proportional income taxation. The choice of such a type of taxation, which came into effect in the mid-1990s in most EU member states (positioned in Central and Eastern Europe), is usually justified by the pursuit of simplification of the tax system and increasing administrative efficiency, attempts to reduce the shadow economy and stimulate investment activity, including with a focus on attracting foreign investors, carrying out economic and political reforms, and other relevant aspects.

Estonia is the first EU member state to implement a proportional tax on personal and corporate income. This occurred in 1994, or ten years before the country’s accession to the EU. The previously applied progressive tax with a maximum marginal rate of 33% for personal income and 35% for corporate income was replaced with a flat marginal tax rate of 26%. After Estonia’s accession to the European Union (in 2004), the marginal income tax rate began to gradually decrease in 2005, reaching 20% by 2015. Since the beginning of 2025, a decision has been made by the legislative body of Estonia to increase the rate for both income taxes to 22% and as of 2026 the marginal tax rate will attain 24%.

Romania, following the example of Estonia, modified the way it taxed the income of individuals and corporations before joining the EU. The country became a member of the EU in 2007, and the changes date back to 2005, when Romania introduced a flat personal and corporate income tax at a rate of 16%. Previously, personal income had been subject to progressive taxation, with a maximum marginal tax rate of 40%, and corporate income had been subject to 25%. Following the reforms of the mid-1900s, corporate tax in Romania remains at 16% to this day, while since 2018, personal income tax has been reduced to 10%.

The third country that still applies proportional taxation today is Bulgaria. Since joining the EU in 2007, the country has applied a flat rate to the income of corporate entities. A year later, in 2008, the tax system adopted proportional personal income tax. The rate for both taxes is 10%. Bulgaria, along with Romania, are the two countries with the lowest marginal tax rate of countries using proportional income tax.

The last among the four EU member states, Hungary, introduced a proportional personal income tax in 2011, seven years after the country became an EU member. The tax rate is 16%, which is a significantly lower tax burden compared to the maximum marginal tax rate in the late 1980s, when it reached 60%. In pursuit of a mechanism to strengthen the competitiveness of the Hungarian tax system (Ministry for National Economy, 2015), in 2016, the personal income tax was reduced to 15%, and since 2017 Hungary has applied the lowest corporate income tax rate in the entire EU—9%. The Hungarian government implemented a flat marginal corporate tax rate until 2010, which declined from 40 to 19% between 1990 and 2010. During the period from mid-2010 to the end of 2012, the corporate tax was progressive. It is worth noting that Hungarian tax legislation also provides for the application of a local business tax of up to 2%, which is determined by local authorities and deducted from corporate income tax, bringing the effective tax burden to around 10.82% (European Commission, 2025).

Therefore, the present research focuses on an analysis of the relationship between income taxes and economic growth in the context of the economies of Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, and Estonia. All four countries belong to the Eastern Europe region. Most Eastern European countries share the characteristic of a lower fiscal significance of income taxes compared to consumption taxes. For the period since 2013, on an annual basis, income taxes in Estonia have formed between 20 and 25% of the revenue collected in the consolidated budget, and after the recovery from the global economic crisis, a gradual (albeit imperceptible) increase in their relative share has been observed. For the remaining three countries—Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary—the share of income tax is around, and no more than, 20%. Comparatively, the average value of this indicator for the EU-27 is around 30%, and in some countries, such as Denmark, it exceeds 60–65%. In terms of the ratio of accumulated income tax revenue to GDP, the four analyzed countries rank among the group of member states with the lowest indicator values. In Estonia, income taxes account for approximately 7.7% of GDP (according to the latest available annual data for 2024 it is 9%), in Hungary, this is about 6.5%, in Bulgaria, 5.4% and in Romania, 5.2% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used in this study. The graphs and descriptive statistics presented in this section are based on the use of quarterly unadjusted data (without seasonal or calendar adjustments). The analysis covers the period from the beginning of 2013 (2013 Q1) to the beginning of 2025 (2025 Q1), which includes a total of 49 observations. The reason for choosing this period is that since then, proportional income taxes of individuals and legal entities have been applied in the four selected EU member states.

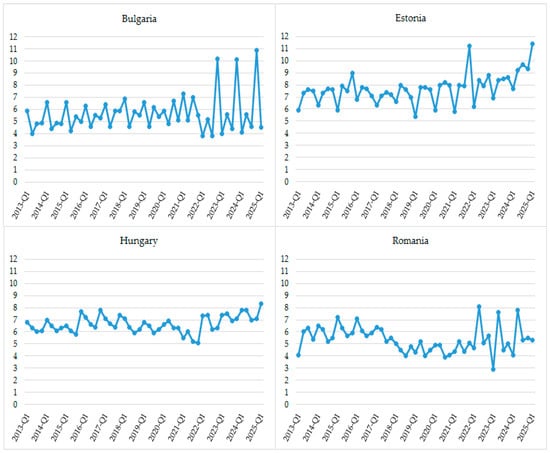

The study relies on income tax revenue data from Eurostat’s (2025c) quarterly non-financial accounts for the general government. It should be noted that the current research uses data that refer to the general government sector. Figure 1 presents the trend in the tax burden by quarter within the period under review.

Figure 1.

Tax burden of income taxes (%), quarterly data for 2013 Q1 to 2025 Q1.

The available data clearly highlight the aforementioned more significant (increasing) burden that income taxes have in Estonia compared to the other three countries. A possible explanation lies in the income tax reforms launched in recent years, especially with the rise in the marginal tax rates of the main income tax. Another important feature in the presented dynamics of this indicator is the serious fluctuation that has been observed in Bulgaria within the recent two to three budget years, and particularly during the last quarters of each of these years. Romania shows similar trends, but with considerably smaller deviations with respect to the data for Bulgaria.

The analysis uses real gross domestic product per capita (RGDP), which represents economic growth and operates as a second explanatory variable. For the calculation of this indicator, Eurostat data on real GDP and also its data on population in the analyzed countries are applied (Eurostat, 2025a, 2025b). The inclusion of the GDP per capita indicator is persistently observed in econometric research and aims to emphasize the relationship between economic development and tax burden, eliminating the effect of differences in population size and allowing for a more comparable measurement of welfare and productivity across different economies or time periods (Tosun & Abizadeh, 2005; Morley & Abdullah, 2010; Arnold et al., 2011; Karagianni et al., 2012; Causa et al., 2014; Tiwari & Mutascu, 2014; Saafi et al., 2017; Yildiz & Sandalci, 2019; Maganya, 2020; Karabacak & Meçik, 2022; etc.).

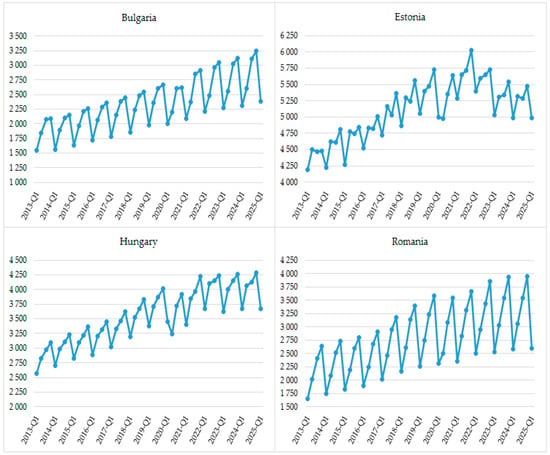

Figure 2, below, illustrates the dynamics of the real GDP per capita indicator for the four selected countries.

Figure 2.

Real GDP per capita (in Euros), quarterly data for 2013Q1 to 2025Q1.

The data presented in Figure 2 indicate that in three of the countries under consideration there is a sustained increase in real GDP per capita for the period from the first quarter of 2013 to the first quarter of 2025. Estonia is the only country where the indicator shows some variability, including a decline since the beginning of 2021. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that Estonia is distinguished by the highest value of the assessed indicator. Estonia also demonstrates inconsistent dynamics between quarters over the years, while in other analyzed countries, and especially in Romania, significant fluctuations occur between the first quarter of each year and the subsequent quarters.

4. Methodology

In order to examine the relationship between economic growth and tax burden, the study consistently applies a set of econometric tests and models widely accepted in the academic literature. In the context of the logical structure of this research, the analysis begins with a seasonal adjustment of the selected variables. This procedure is essential due to the inclusion of quarterly data, which most likely contain seasonal fluctuations, resulting in the inaccurate identification of short-term and long-term relationships. Then, the analysis uses the Census X-13 method. Subsequently, each seasonally adjusted variable is transformed into a logarithm, which aims to improve the precision of the comparative interpretation.

The next step involves conducting stationary tests on the seasonally adjusted and logarithmically transformed variables. The verification is carried out by employing two statistically independent tests, the test of Phillips and Perron (1988) and the Augmented test of Dickey and Fuller (1981), whereas the research implements the information criteria of Akaike and Schwarz separately. The choice of equation specification is consistent with the time dynamics of the variables. The test procedure evaluates the variables subsequently at levels and then at first difference. After conducting stationary tests, if the results indicate that the variables are stationary in first difference and non-stationary in levels, the analysis proceeds with the application of the Johansen test in order to determine whether there is a long-term relationship. Within the framework of the Johansen test, the methodology relies on two statistical procedures—the Trace test (Equation (3)) and Maximum Eigenvalue Test (Equation (6))—and the following hypotheses are defined (Equations (1), (2), (4) and (5)):

Johansen Trace Test

The test statistic is defined as follows:

where T refers to the number of observations, n to the number of variables in Yt (vector of endogenous variables), to the number of cointegrating relations under null hypothesis H0, and to the estimated i-th eigenvalue of the Π matrix.

For completeness, in the case of a bivariate system (such as between LNRGDPt and LNTAXt), the cointegration rank can only take values r0 = 0 (no cointegration) or r0 = 1 (one cointegrating vector).

Maximum Eigenvalue Test

The test statistic is defined as follows:

where T refers to the number of observations, to the number of cointegrating relations under null hypothesis H0, and to the (r0 + 1)-th largest estimated eigenvalue of the Π matrix.

The Maximum Eigenvalue test examines the null of r0 cointegrating vectors against the alternative of r0 + 1, focusing on the largest remaining eigenvalue rather than the sum of all subsequent ones as in the Trace test.

In addition to the analysis, the traditional (classical) Granger causality is applied, which aims to shed light on whether there is a causal relationship between the variables under study, what its direction is, and whether it is possible to make a forecast for the future values of one variable using the temporal dynamics of another (Equations (7) and (8)).

where α and η refer to intercept terms, i refers to the country (where i = 1, …, N); t refers to the time period (where t = 1, …, T); r and m refer, respectively, to the lags (where r = 1, …, z and m = 1, …, k); k and z refer, respectively, to the optimal lag for variables LNRGDP and LNTAX; β refers to the coefficient on lagged growth rates (captures the autoregressive dynamics of economic growth), γ to the coefficient on lagged tax burden (measures the effect of past tax burden on economic growth), μ to the coefficient on lagged tax burden (persistence of tax burden), θ to the coefficient on lagged growth rates (effect of growth on tax burden), and ε and υ are the residual components.

The application of the Granger test involves two hypotheses, as follows (Equations (9)–(12)):

(a) Testing whether tax burden Granger causes economic growth:

(b) Testing whether economic growth Granger causes tax burden:

Expanding the analytical framework of the study implies the formulation of reliable conclusions from the application of impulse functions and variance decomposition. This is reasonable, considering that it is essential to graphically illustrate how the variables under study respond to shocks in the system and, more specifically, how this affects the temporal dynamics.

From the methodological perspective, the research follows a standard procedure for selecting the optimal number of lags for each of the countries covered by the analysis. The determination of the optimal lag for a specific country is based on the results obtained from the procedure combined with additional considerations in light of the specification of the models, the number of observations, and the reliability of the results. More precisely, the lag order selection criteria (based on a sequential modified Likelihood Ratio test statistic (LR); final prediction error (FPE); Akaike information criterion (AIC); Schwarz information criterion (SC), and Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQ)) are applied and the lag length identified as optimal by the majority of the criteria is chosen.

5. Results

5.1. Results from Stationarity Tests

The stationarity test of the variables is based on the application of the Augmented test of Dickey and Fuller (1981) and the test of Phillips and Perron (1988). Through the use of two independent tests, the aim is to achieve greater reliability of the analysis. The implementation of stationarity tests follows a sequential procedure, starting with a test at levels and continuing with a test at first differences. Table 2 illustrates the results of testing the LNRGDP and LNTAX variables at levels for all countries included in the analysis.

Table 2.

Results from stationarity tests (at levels).

The results of the stationarity tests at levels indicate that the variables are not stationary. In general, there is no variable for which, in all the stationarity tests used, the obtained probabilities are less than the 5% significance level. This applies in all cases except for the variable LNRGDP for Bulgaria (based on the Akaike info criterion), but these results are not confirmed in all tests used. In other words, the time series of the variables indicate the presence of unit roots, i.e., there is I(1). As a result, this provides grounds for conducting stationarity tests of the variables at first differences.

Table 3 presents the results of testing the variables LNRGDP and LNTAX at first differences.

Table 3.

Results from stationarity tests (at first differences).

The results indicate that there is no variable for which, in all stationarity tests, the obtained probabilities are greater than the 5% significance level. For this reason, the variables included in the study are stationary at first difference.

5.2. Results from Johansen Cointegration Test

After conducting stationarity tests, the results confirm that the variables are non-stationary at levels and, accordingly, stationary at first differences, which provides an adequate reason to proceed to a test for long-run relationships between economic growth and tax burden through the Johansen cointegration test. Table 4 summarizes the results of applying this test for all analyzed countries.

Table 4.

Results from Johansen cointegration test.

In accordance with the findings from the Johansen test, shown in Table 4, the study demonstrates that for Bulgaria and Romania, there is cointegration between the economic growth and the tax burden, i.e., there is a long-term statistically significant relationship. This is confirmed by the comparison between the values of the trace statistics and the critical value, in a manner similar to that of the Max-Eigen statistics and the critical value, and finally, the estimated p-values, all of which lead to the conclusion that there is one cointegration equation. The results of the Johansen test for Bulgaria and Romania give reason to assert that in the long run, the analyzed variables move together over time, which means that in the long-term, there is a sustainable interdependence. It is therefore reasonable to reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative, which postulates the existence of a cointegrating relationship. Furthermore, even if it is assumed that serious fluctuations in the dynamics of these variables are possible in the short-term, the outcomes of the cointegration test confirm the understanding that maintaining stability in the long run requires not underestimating the structural features of tax systems and their association with opportunities for development and growth.

In the case of Estonia and Hungary, it is noticeable that the output values for the trace statistics are lower than the critical value, and these conclusions are also valid when comparing Max-Eigen statistics with the critical value. In addition, the p-values are higher than the 5% significance level. This leads to the conclusion that there is no statistically significant long-run relationship between economic growth and the tax burden in Estonia and Hungary. Despite these findings, it is essential to consider the possibility of the existence of a short-term relationship between the analyzed variables.

Outcomes of the current research on the long-run relationship between economic growth and the tax burden of income taxes in the four countries under consideration can also be partially explained by the structure of tax revenues. In the last few years, Romania and Bulgaria have experienced a balance between the burden falling on individuals and corporate entities (with a slightly greater emphasis on the burden on individuals, and even, in 2022, a reverse trend becoming evident), while significant differences in the division of taxpayers are typical for Hungary and Estonia. The Hungarian and Estonian tax systems generate considerably more resources at the expense of individuals (the difference is almost threefold). The reasons for this are mainly due to the lower marginal tax rate for corporate income in Hungary and exemption from tax on retained earnings in Estonia. Such taxation mechanisms aim to stimulate investment activity in the corporate sector, but at the same time do not allow for a direct determination of the relationship between the tax burden and economic growth, especially in the long run.

5.3. Results from Pairwise Granger Causality Tests

Table 5 shows the results of the pairwise Granger causality test. Based on these, it is possible to conclude that there is causality (predictability) between economic growth and the tax burden, which applies only to Bulgaria and Hungary. This is further supported by the acceptance of the alternative hypothesis that there is a Granger causality from economic growth to the tax burden, as evidenced by the computed probability, which is lower than the 5% significance level. These results highlight that past values of economic growth help predict future values of the tax burden. In other words, favourable changes in the economic environment, which lead to strengthened opportunities for the country to achieve high growth rates, can beneficially impact the taxation system and establish prerequisites for implementing an optimal tax structure.

Table 5.

Results from pairwise Granger causality tests.

The existence of causality from the tax burden to economic growth is rejected for all countries included in the study, and in support of this, the null hypothesis is accepted, stating that past values of the tax burden cannot contribute to predicting future values of economic growth. The obtained probabilities, which are higher than the significance level, support these conclusions. A possible explanation for these causality results in estimating the predictive value of growth may be the sensitivity of the main sources of growth (consumption and investment) to potential changes in income taxation (with the exception of Bulgaria, the other three countries have experienced similar changes, including in the last few years, in the technique of income taxation). It is entirely possible that taxes have effects on both consumption and investment, but over a significantly longer period of time, which would lead to the Granger test demonstrating difficulty in detecting a causal relationship. Another potential contributing factor could be the global instability resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the subsequent inflationary shocks caused by the military actions in Ukraine. It is no coincidence that when reviewing the dynamics of the tax burden and growth (in the Data section), significant fluctuations were found over the last few years, which creates additional challenges in the search for clear dependencies and causal relationships between the analyzed processes.

Furthermore, the analysis does not confirm the existence of a bidirectional relationship between the examined variables for any of the countries included in the study. In summary, the results of the pairwise Granger causality test show evidence of a unidirectional causality of economic growth on tax burden, but this is affirmed only for Bulgaria and Hungary.

5.4. Results from Impulse Responses and Variance Decompositions

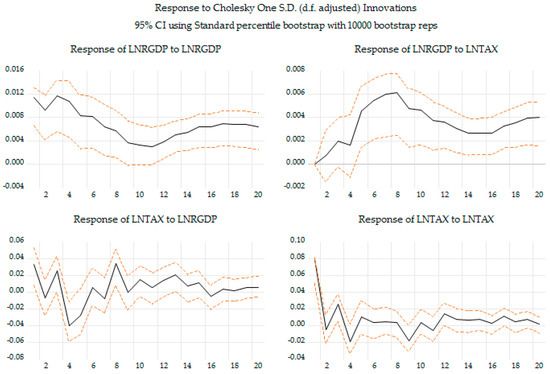

The subsequent analysis continues with a graphical representation of the impulse functions, combined with a variance decomposition, provided that this is applied to the countries for which a cointegration relationship has been established by the Johansen test (Bulgaria and Romania). The presentation of the impulse functions is preceded by the construction of VECMs for the specified countries with a confirmed cointegrating relationship. The present study gives priority to the graphical representation of the variables’ dynamics through impulse functions in order to achieve a better illustration and subsequent analysis of the way in which a given variable responds to a shock in the other variable. To mitigate potential biases from extraordinary macroeconomic disturbances, a dummy variable capturing the crisis period (2020 Q3–2025 Q1) is included in the VECM specification in order to control for unanticipated shocks arising from the joint dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic, the geopolitical conflict between Russia and Ukraine, and the subsequent inflationary pressure. This adjustment helps isolate the structural effects of crisis-related shocks from the long-run relationship between tax burden and economic growth. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the model does not explicitly account for institutional quality, fiscal governance, or confidence in political institutions, which may still affect both variables and contribute to potential endogeneity.

From a research perspective, it is of interest to trace, on the one hand, how economic growth reacts to a shock in the tax burden and, on the other hand, how the tax burden responds to a shock in economic growth. The impulse functions are constructed based on Cholesky one S.D. innovations, and, more specifically, the shock size is one standard deviation. In the Cholesky decomposition, real economic growth per capita is ordered before the tax burden, assuming that growth does not respond contemporaneously to fiscal changes while taxation may react to current economic developments. This recursive structure ensures an economically consistent orthogonalization of shocks and allows for a causal interpretation of the impulse responses. From a temporal perspective, the impulse functions cover a period of 20 quarters (5 years), which allows for the tracing of both short-term and long-term effects due to one-off shocks in economic growth and tax burden. In addition, when using a longer period of time, it is possible to identify effects that are difficult to detect in the short-term. To assess the statistical reliability of the impulse response functions, a bootstrap procedure with 10,000 replications is applied. Since the distribution of the impulse responses is not analytically known, the bootstrap method provides an empirical approximation by repeatedly resampling the residuals and re-estimating the model. Confidence intervals are constructed using the standard percentile approach, which yields stable and consistent estimates for large samples and in the absence of strong nonlinearities, while avoiding the computational burden associated with bias-corrected or studentized bootstrap variants.

Figure 3 presents the impulse function for the economy of Bulgaria. A tax burden shock of one standard deviation does not lead to a slowdown in the rate of economic growth in the short-term, with the specific characteristic that the effect is statistically significant in the range from the fourth to the ninth quarter. However, as the time horizon increases, this stimulating statistically effect begins to weaken. Based on the results obtained in Figure 3, the analysis leads to the conclusion that, in both the short- and long-term, there is pronounced volatility in the tax burden induced by shocks in economic growth. In the short-term (particularly during the fourth quarter), the tax burden responds negatively to a growth shock, while in the long run, the intensity of this effect decreases; however, wide confidence intervals and a high uncertainty limit firm conclusions.

Figure 3.

Impulse response of economic growth and tax burden in Bulgaria.

Table 6 outlines the results for Bulgaria from the variance decomposition of economic growth in response to an identified tax burden shock and the variance decomposition of the tax burden after registering an economic growth shock. Assuming a period of 20 quarters, it is possible to trace the effects of variance decomposition, both in the short- and long-term. According to the results of the variance decomposition for Bulgaria, it can be concluded that in the short-term (e.g., the first ten quarters) a significantly larger percentage of the variance in economic growth is due to shocks within the country’s economy (approximately 20%), and these findings are not confirmed in the long run, when the variance tends to decrease. This is reasonable, given the possibility of other factors influencing growth, such as determining factors beyond the country’s structural components.

Table 6.

Variance decomposition of economic growth and tax burden in Bulgaria.

The systematized data in Table 6 show that, compared to the short-term, in the long-term, an increasing share of the variance in GDP is explained by shocks in the tax burden. Indicative in this regard is the expanding impact of tax structure, with a comparative increase of nearly 22 p.p. in the significance of tax shocks with regard to economic growth determination. This suggests the strengthening importance of fiscal policy in Bulgaria and its subsequent relationship with effects on the country’s economic development.

In comparison with the variance in economic growth, the analysis regarding the tax burden is explained to a much greater extent by the impact of shocks on economic growth. While in the short-term (the first four quarters), the variance in the tax burden is to a lesser extent determined by the effects of economic growth shocks, in the long-term, this influence rises, remaining steadily within the range of 36% to just over 44%. The results indicate that in the long-term, the significance of economic growth and its impact on the tax system, or tax revenues, should not be underestimated. In the long run, the share of variance arising from a shock in the tax burden itself gradually decreases, which quite logically enhances the importance of the contribution of other factors that help interpret the variable’s value

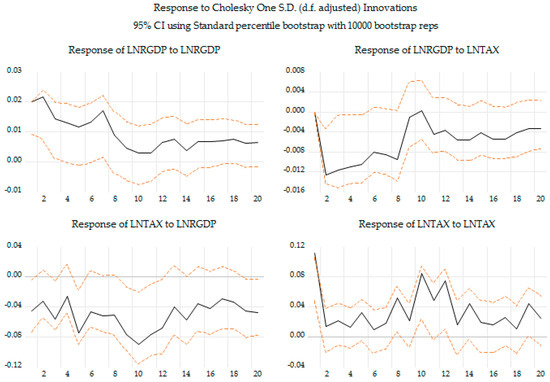

Figure 4 depicts the results of the impulse function for Romania. There are no positive effects on economic growth as a result of one standard deviation shock in the tax burden, either in the short run or in the long run. Such a conclusion can be drawn with a certain degree of confidence up to the fifth quarter, and after that the data show that the results are characterized by statistical uncertainty. The reaction of the tax burden to a shock in economic growth is characterized by pronounced alternating negative values over time. In the short-term (especially in the third quarter) and in the medium-term (notably in the fifth quarter and from the ninth to twelfth quarters), the findings indicate some reliability, but this does not extend to other periods. Obviously, in years of growth, the expansion of the Romanian economy outpaces the rate at which income tax revenues rise, thus reducing the relative size of the tax burden. To some extent, this stems from proportional taxation, taking into account that it does not impose a greater burden on considerably higher incomes, which usually tend to increase at a faster rate during periods of economic prosperity.

Figure 4.

Impulse response of economic growth and tax burden in Romania.

Table 7 shows variance decomposition outcomes for Romania. When examining the variance decomposition of economic growth, it is established that, in both the short and long run, a substantial part of the shocks in growth are due to the growth itself and this effect tends to gradually decrease over time but nevertheless continues to record quite high values. As the period length increases, shocks in the tax burden begin to exert a stronger impact on growth, with approximately 30% of the variance in growth being explained by tax burden shocks by the end of the period. Compared to Bulgaria, in Romania, shocks in the tax burden largely result from economic growth shocks. Specifically, while in Bulgaria, in the long-term, up to approximately 45% of the predictable changes in the tax burden are explained by previous shocks in economic growth, for Romania they reach just over 60%.

Table 7.

Variance decomposition of economic growth and tax burden in Romania.

In summary, the outcomes from the variance decomposition for both Romania and Bulgaria indicate that the tax burden is significantly more affected by growth shocks. This strengthens the role of the macroeconomic environment and its subsequent relationship with the tax system. In the context of proportional taxation of the incomes of individuals and legal entities, it can be concluded that in the analyzed countries, there is a strong sensitivity of the tax system to economic activity. This further emphasizes the importance of a more in-depth examination of the relationship between the phases of the economic cycle and the state of automatic budget stabilizers.

6. Discussion

One of the key findings of the present study is that the relationship between the tax burden of income taxes and economic growth in the long run is not always evident, but can be established. For two of the countries examined (Romania and Bulgaria), the presence of a similar dependence is demonstrated, which is consistent with the results obtained in the majority of earlier studies (Anastassiou & Dritsaki, 2005; Mucuk & Alptekin, 2008; Mashkoor et al., 2010; Helhel & Demir, 2012; Terzi & Yurtkuran, 2016; Odum et al., 2018; Yildiz & Sandalci, 2019; Maganya, 2020; Shanmugam & Arunima, 2021; Tanchev, 2021). On the other hand, for Hungary and Estonia, the existence of a relevant association in the long run cannot be confirmed, which is also recognized as a conclusion in a significant number of scientific research in the field of taxation and growth of the national economy (Abdiyeva & Baygonuşova, 2016; Eren et al., 2018; Karabacak & Meçik, 2022).

Based on the VECM and the corresponding impulse functions, differences emerge regarding the relationship between shocks and the income tax burden and economic growth in Romania and Bulgaria. In Romania the direction of influence in both cases (from growth to tax burden and from tax burden to growth) is such that growth shocks negatively affect both tax revenue collection and tax burden itself, and the shock in the income tax burden has a restraining (negative) effect on the possibility of achieving a higher level of national economic performance. In Bulgaria, the effect of economic growth on the tax burden of income taxes is quite volatile. Similarly in the case of Romania, in the short run (only in the fourth quarter), the negative effect of growth on the tax burden can be confirmed with statistical certainty. On the other hand, the results of the impulse function show that the low tax burden in Bulgaria has a rather positive effect on the growth opportunities of the national economy in the medium-term, which the analysis does not validate for Romania. Incidentally, the outcomes obtained for the Romanian economy largely coincide with the conclusions reached by Bâzgan (2018). Although both studies demonstrate that—with regard to the impact of tax burden from direct taxes (in case of income taxes) on economic growth—a negative impact is established, characterized by a much lower intensity in the long-term, a significant difference also emerges when examining the influence of the growth of the Romanian economy on the revenue collection from income taxes. The current study outlines a negative trend in this interaction, which applies to both the short- and medium-term, whereas in Bâzgan (2018) the negative shock in subsequent periods is insignificant. These results can, to some extent, be explained by differences in the approach used, as well as the time period of the analysis. It should be noted that the research period in this study covers recent years, which feature a number of social, economic, and health shocks, including the negative impact of COVID-19, the consequences of the war in Ukraine, inflationary shocks, etc. Furthermore, the fiscal policy pursued in Romania over the past few years raises a number of questions about the sustainability of its public finances, not only in the long-term, but also in the short-term. Romania was the only EU member state subject to an ongoing excessive deficit procedure before COVID-19, and this trend persists, with the budget deficit forming a substantially higher share of GDP.

The conclusions drawn regarding the positive impact of the income tax burden on growth in Bulgaria in the medium- and long-term were anticipated to a certain degree. The country has an extremely low tax burden on income, and the changes that occurred at the end of the first decade of the XXI century, including EU accession, aimed to simplify the tax system, reduce the shadow economy, attract foreign investment, and most importantly, contribute to higher economic growth. These findings on the positive impact of income taxes on growth are also observed in the research by Stoilova (2023) for Central and Eastern European countries, as well as in a study by the same author for EU member states (Stoilova, 2024)—including Bulgaria. On the other hand, Tanchev (2021) manages to prove that in Bulgaria, the proportional personal income tax negatively affects economic growth. Nevertheless, this study examines the aggregate burden of all income taxes, not just personal income tax. The corporate income tax in Bulgaria is among the lowest in the entire EU and this can be interpreted as an important fiscal mechanism for stimulating growth, further supporting the difference between our outcomes and those presented by Tanchev (2021). In the context of the four analyzed countries with proportional income taxation, Bulgaria stands out as a country in which personal and corporate income are levied at the same tax rate, with a substantially lower tax rate. Estonia also imposes the same tax rates on corporate and personal income, but its marginal tax rates are twice as high as those in Bulgaria. In Hungary and Romania, there is a difference between the applicable marginal tax rates of the two main income taxes, and this may be among the main reasons for the negative shock of the tax burden on growth in Romania compared to the results in Bulgaria. In addition, the burden of corporate tax is greater (measured by the marginal tax rate).

7. Conclusions

The present study focuses on examining the relationship between, and potential effects of income tax policy and the achievement of economic growth in four Eastern European countries. The choice of these countries is not incidental, as these are currently the only member states of the EU that continue to apply proportional taxation to personal and corporate income. The findings of the research demonstrate that despite the implementation of a similar type of tax policy concerning the taxation of income in the period 2013 Q1–2025 Q1, it is not always possible to establish that the difference in the tax burden of these taxes contributes to generating higher levels of well-being. For Bulgaria and Romania, the analysis identifies a long-term cointegration link between the tax burden and economic growth, whereas Hungary and Estonia do not exhibit such a relationship. The subsequent analysis of the impact of the tax burden on growth in Bulgaria and Romania also leads to variations in the results obtained. While in Bulgaria, the increased shocks in the tax burden have a positive effect on the level of gross domestic product per capita, in Romania, this influence is negative. On the other hand, in Romania, shocks related to the growth of the national economy appear to have negative impact on tax revenue from income taxation, while no distinct effect is defined in Bulgaria, but evidence of an asymmetric response is observed. Such conclusions are frequently associated with growth in the national economy due to economic sectors characterized by reduced (preferential) tax rates, and cases where estimates of the level of the informal economy are significant. Bulgaria and Romania continue to remain among the leading positions in the ranking for the highest level of informal economy in the entire European Union (Schneider & Asllani, 2022).

On the other hand, the Granger test does not find a statistically significant predictive causality from the tax burden to growth in any of the four countries, including Bulgaria and Romania, which means that past values of the tax burden do not contain additional information for predicting growth. These results are not mutually exclusive, as the Granger test examines forecasting, not structural causality, so it is entirely possible to have a long-run relationship and a positive response to shocks without significant predictive power in the tax burden lags. The findings of the Granger test show that it is possible to establish causality when forecasting the tax burden based on economic growth in Bulgaria and Hungary.

Future research on the relationship between income taxes and economic growth can focus on several directions, including tracing the impact of income taxes on specific components of the expenditure structure of GDP (e.g., household consumption spending and investment in strategic sectors for economies), examining the link or dependence between income taxes and the opportunities for achieving environmentally sustainable growth, as well as analyzing the challenges associated with taxing new sources of income (e.g., income from the use of cryptocurrencies) and the subsequent effects of this on consumer behaviour and the conditions for promoting economic development. It is important to consider that the tax policies implemented in the four analyzed countries related to income taxes face future challenges in terms of increasing fiscal instability (especially in Romania and Hungary), harmonization of national and European policies (including the introduction of a higher tax burden in the area of corporate income taxation—this mainly applies to Bulgaria and Hungary), and the growing interest in a fairer model of personal income taxation through implementation of progressive taxation. These challenges should also be the subject of further research, which should include their effects on the examined relationships.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and V.N.; Methodology, A.A. and V.N.; Software, A.A. and V.N.; Validation, A.A. and V.N.; Formal analysis, A.A. and V.N.; Investigation, A.A. and V.N.; Resources, A.A. and V.N.; Data curation, A.A. and V.N.; Writing—original draft, A.A. and V.N.; Visualization, A.A. and V.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the University of National and World Economy Research Programme (Research Grant No. 13/2024/A).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike information criterion |

| ARDL | Autoregressive distributed lag model |

| CEE | Central and Eastern Europe |

| CIT | Corporate income tax |

| EU | European Union |

| FPE | Final prediction error |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| HQ | Hannan-Quinn information criterion |

| LR | Sequential modified Likelihood Ratio test statistic |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PAYE | Pay As You Earn |

| PIT | Personal income tax |

| SC | Schwarz information criterion |

| S. D. | Standard deviation |

| S. E. | Standard error |

| U-VAR | Unrestricted Vector Autoregression |

| VAR | Vector Autoregression |

| VECM | Vector Error Correction Model |

References

- Abdiyeva, R., & Baygonuşova, D. (2016). Geçiş ekonomilerinde vergi gelirleri ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi: Kirgizistan örneği. Akademik Bakış Uluslararası Hakemli Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, ((53)), 59–71. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/pub/abuhsbd/issue/32947/366131 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Adhikari, B., & Alm, J. (2013, January). Did Latvia’s flat tax reform improve growth? In Proceedings of the annual conference on taxation and minutes of the annual meeting of the national tax association (Vol. 106, pp. 1–9). National Tax Association. [Google Scholar]

- Anastassiou, T., & Dritsaki, C. (2005). Tax revenues and economic growth: An empirical investigation for Greece using causality analysis. Journal of Social Sciences, 1(2), 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, A., & Nikolova, V. (2021). The impact of tax burden and tax structure on the economic growth of the Balkan region. Finance, Accounting and Business Analysis (FABA), 3(1), 31–40. Available online: https://faba.bg/index.php/faba/article/view/69 (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Arikan, C., & Yalcin, Y. (2013). Determining the exogeneity of tax components with respect to GDP. International Journal of Academic Research in Accounting, Finance and Management Sciences, 3(3), 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, J. M., Brys, B., Heady, C., Johansson, Å., Schwellnus, C., & Vartia, L. (2011). Tax policy for economic recovery and growth. The Economic Journal, 121(550), F59–F80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bâzgan, R. M. (2018). The impact of direct and indirect taxes on economic growth: An empirical analysis related to Romania. Proceedings of the International Conference on Business Excellence, 12(1), 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitung, J., & Candelon, B. (2006). Testing for short- and long-run causality: A frequency-domain approach. Journal of Econometrics, 132, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassou, S. P., & Lansing, K. (1996). Growth effects of a flat tax. (Working Paper 9615). Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. Available online: https://www.clevelandfed.org/-/media/project/clevelandfedtenant/clevelandfedsite/publications/working-papers/1996/wp-9615-growth-effects-of-a-flat-tax-pdf.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Causa, O., Araujo, S., Cavaciuti, A., Ruiz, N., & Smidova, Z. (2014). Economic growth from the household perspective: GDP and income distribution developments across OECD countries. (OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1111). OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornevin, A., Corrales, J. S., & Mojica, J. P. A. (2024). Do tax revenues track economic growth? Comparing panel data estimators. Economic Modelling, 140, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, A. D., & Fuller, W. A. (1981). Likelihood ratio statistics for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Econometrica, 49(4), 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diks, C., & Panchenko, V. (2006). A new statistic and practical guidelines for nonparametric Granger causality testing. Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control, 30(9–10), 1647–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.-I., & Hurlin, C. (2012). Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Economic Modelling, 29(4), 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, M. V., Ergin, A., & Aydın, H. İ. (2018). Türkiye’de vergi gelirleri ile ekonomik kalkinma arasindaki ilişki: Frekans alani nedensellik analizi. Doğuş Üniversitesi Dergisi, 19(1), 1–18. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2152122 (accessed on 22 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2025). Data on taxation trends. Statutory tax rates. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/document/download/6e2a5960-f13c-4aef-b115-60e3ba232966_en?filename=statutory_rates_2022.xlsx (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Eurostat. (2013). European system of accounts: ESA 2010. Publications Office. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. (2025a). Gross domestic product (GDP) and main components (output, expenditure and income). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/namq_10_gdp/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Eurostat. (2025b). Population on 1 January by age and sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_pjan/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Eurostat. (2025c). Quarterly non-financial accounts for general government. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/gov_10q_ggnfa/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- González-Torrabadella, M., & Pijoan-Mas, J. (2006). Flat tax reforms: A general equilibrium evaluation for Spain. Investigaciones Económicas, 30(2), 317–351. Available online: https://www.fundacionsepi.es/investigacion/revistas/paperArchive/May2006/v30i2a5.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Granger, C. W. J. (1969). Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica, 37(3), 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helhel, Y., & Demir, Y. (2012, May 31–June 1). The relationship between tax revenue and economic growth in Turkey: The Period of 1975–2011. 3rd International Symposium on Sustainable Development, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Available online: https://omeka.ibu.edu.ba/items/show/2341 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Hiemstra, C., & Jones, J. D. (1994). Testing for linear and nonlinear granger causality in the stock price-volume relation. Journal of Finance, American Finance Association, 49(5), 1639–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlavac, M. (2008). Fundamental tax reform: The growth and utility effects of a revenue-neutral flat tax. MPRA paper No. 24241. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/24241/1/MPRA_paper_24241.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica, 59(6), 1551–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabacak, M., & Meçik, M. (2022). Analysing the tax structure of turkish economy: A time-varying causality analysis. Sosyoekonomi, 30(51), 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagianni, S., Pempetzoglou, M., & Saraidaris, A. (2012). Tax burden distribution and GDP growth: Non-linear causality considerations in the USA. International Review of Economics & Finance, 21(1), 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani, F. K. (2021). The causal effect between tax revenue and economic growth in Kenya [MOI UNIVERSITY]. Available online: https://ikesra.kra.go.ke/server/api/core/bitstreams/a7aabd7f-45da-48e6-961c-e0c3768bfcea/content (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Maganya, M. H. (2020). Tax revenue and economic growth in developing country: An autoregressive distribution lags approach. Central European Economic Journal, 7(54), 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majcen, B., Verbič, M., Bayar, A., & Čok, M. (2009). The income tax reform in Slovenia: Should the flat tax have prevailed? Eastern European Economics, 47(5), 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashkoor, M., Yahya, S., & Ali, A. (2010). Tax revenue and economic growth: An empirical analysis for Pakistan. World Applied Sciences Journal, 10(11), 1283–1289. Available online: http://www.idosi.org/wasj/wasj10%2811%2910/3.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Ministry for National Economy. (2015). Major changes expected to increase tax competitiveness in Hungary. Available online: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/download/1/61/a0000/Hungarian%20Outlook_Major%20changes%20expected%20to%20increase%20tax%20competitiveness%20in%20Hungary.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Morley, B., & Abdullah, S. (2010). Environmental taxes and economic growth: Evidence from panel causality tests’ bath economics research working papers, no. 4/10. Department of Economics, University of Bath. Available online: https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/301474/0410.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Mucuk, M., & Alptekin, V. (2008). Türkiye’de vergi ve ekonomik büyüme ilişkisi: VAR analizi (1975–2006). Maliye Dergisi, (155), 159–174. Available online: https://ms.hmb.gov.tr/uploads/2019/09/10.Mehmet.MUCUK_Volkan.ALPTEKIN.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Muduli, D. K., & Manik, N. (2020). Tax structure and economic growth in general category states in India: A panel auto regressive distributed lag approach. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 2(623), 225–240. Available online: https://store.ectap.ro/articole/1464.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Nayak, P. P., Palai, P., Khatei, L., & Mallick, R. K. (2022). Tax revenue and economic growth nexus in India: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Orissa Journal of Commerce, 43(3), 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, A. N., Odum, C. G., & Egbunike, F. C. (2018). Effect of direct income tax on gross domestic product: Evidence from the Nigeria fiscal policy framework. Indonesian Journal of Applied Business and Economic Research, 1(1), 59–66. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328207120_Effect_of_Direct_Income_Tax_on_Gross_Domestic_Product_Evidence_from_the_Nigeria_Fiscal_Policy_Framework (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Petru-Ovidiu, M. (2015). Tax composition and economic growth. A panel-model approach for Eastern Europe. Annals of the “Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu Jiu, Economy Series, 1, 89–101. Available online: https://www.utgjiu.ro/revista/ec/pdf/2015-01.Volumul%202/14_Mura.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Phillips, P. C. B., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 72(2), 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafi, S., Mohamen, M. B. H., & Farhat, A. (2017). Untangling the causal relationship between tax burden distribution and economic growth in 23 OECD countries: Fresh evidence from linear and non-linear Granger causality. The European Journal of Comparative Economics, 14(2), 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, F., & Asllani, A. (2022). Taxation of the informal economy in the EU. Policy department for economic, scientific and quality of life policies directorate-general for internal policies. Study requested by the FISC committee. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2022/734007/IPOL_STU(2022)734007_EN.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Shanmugam, V. P., & Arunima, P. (2021). Impact of direct and indirect tax revenue on economic growth of puducherry. Dogo Rangsang Research Journal UGC Care Group I Journal, 11(2), 92–101. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3797439 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Sims, C. A. (1980). Macroeconomics and reality. Econometrica, 48(1), 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songur, M., & Yüksel, C. (2018). Vergi yapisi ile ekonomik büyüme arasindaki nedensellik ilişkisi: Türkiye örneği. Finans Politik Ve Ekonomik Yorumlar, (643), 47–70. Available online: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/fpeyd/issue/47979/607023 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Stoilova, D. (2023). The impact of tax structure on economic growth: New empirical evidence from central and eastern Europe. Journal of Tax Reform, 9(2), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilova, D. (2024). Tax structure and economic growth: New empirical evidence from the European Union. Journal of Tax Reform, 10(2), 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanchev, S. (2021). Long-run equilibrium between personal income tax and economic growth in Bulgaria. Journal of Tax Reform, 7(1), 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzi, H., & Yurtkuran, S. (2016). Türkiye’de dolayli/dolaysiz vergi gelirleri ve Gsyh ilişkisi. Maliye Dergisi, 171, 19–33. Available online: https://ms.hmb.gov.tr/uploads/2019/09/171-02.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Tiwari, A. K. (2012). Tax burden and GDP: Evidence from frequency domain approach for the USA. Economics Bulletin, 32(1), 147–159. Available online: http://www.accessecon.com/Pubs/EB/2012/Volume32/EB-12-V32-I1-P15.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2025).