Simple Summary

Radiotherapy is one of the most effective treatments for cancer, but its success is often limited by tumor radioresistance and the complex interactions within the tumor microenvironment. Patient-derived organoids are miniature, three-dimensional models grown from a patient’s own tumor that closely mimic the biology and treatment response of real tumors. These organoids provide a promising tool to study why some tumors resist radiation and to test strategies that make radiotherapy more effective. This review summarizes how organoids are used to explore the mechanisms of radioresistance—such as DNA repair, tumor metabolism, immune remodeling, and radiation-induced senescence—and discusses how integrating organoid models with immune and vascular components could accelerate the discovery of personalized radiosensitizers and improve cancer treatment outcomes.

Abstract

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) preserve patient genotypes and 3D architecture, offering a useful platform to investigate mechanisms of radioresistance and test radiosensitizers. We outline an end-to-end workflow—model establishment, multi-omics profiling, pharmacologic screening, and in vivo confirmation—and spotlight immune-competent, vascularized, and organ-on-chip formats. PDOs reveal actionable mechanisms across DNA damage response, hypoxia–metabolic and immune remodeling, and radiation-induced senescence, enabling rational radiosensitizer selection. Paired tumor–normal organoids concurrently gauge efficacy and normal tissue toxicity, refining the therapeutic index. Remaining gaps (incomplete microenvironment, fractionation modeling, and standardization) are being addressed via reporting standards and co-clinical studies, positioning PDOs to support precision radiotherapy.

1. Introduction

Radiotherapy (RT) treats roughly half of all cancer patients, yet durable control is often limited by radioresistance. Mechanisms span enhanced DNA damage repair, cancer stem cell plasticity, hypoxia-driven redox and metabolic reprogramming, and immune remodeling within the tumor microenvironment (TME) [1].

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs) preserve tumor histology, genomics, and intratumoral heterogeneity, offering a tractable platform to interrogate resistance biology and functionally test therapies in a patient-proximal manner [2,3]. Emerging evidence indicates that organoid responses can mirror clinical treatment sensitivity, including to radiation in specific settings. In parallel, advanced co-cultures and organ-on-a-chip systems enable incorporation of stromal, immune, and vascular components and support concurrent assessment of normal tissue toxicity—key for defining a therapeutic window in radiosensitizer development [4].

This review provides a concise synthesis of how PDO platforms are being applied to (i) map cellular and molecular determinants of radioresistance; (ii) anticipate RT response at the individual-patient level; and (iii) guide rational, mechanism-based radiosensitization strategies—including materials-enabled approaches—without pre-empting results or conclusions.

2. Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids: Establishment and Application

Organoid technology began in 2009, when Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells were used to generate self-organizing small-intestinal organoids with crypt–villus architecture, formally introducing the concept of the “organoid” [5]. Subsequent advances included human colon organoid cultures (2011) and the first colorectal cancer (CRC) organoid model reported, which preserved the mutational landscape of primary tumors [6]. In parallel, a living biobank of CRC organoids was established, bringing patient-specific drug sensitivity testing into practical use [7].

PDOs are established through a standardized process beginning with the acquisition of fresh patient-derived tumor tissue from surgical resections or biopsies. After removal of non-epithelial tissue, samples are mechanically and enzymatically dissociated to small clusters or single cells, cleared of debris, and embedded in a 3D extracellular matrix hydrogel (e.g., Matrigel, Geltrex, and tissue-specific or synthetic matrices). Over days to weeks, cells self-organize into 3D structures that retain key histologic and genetic features of the source tumor. Across PDO subtypes, growth factor formulations vary slightly. Organoids are expanded by mechanical or enzymatic passaging and re-embedding, and can be cryopreserved to create living biobanks that preserve intratumoral heterogeneity for disease modeling, drug screening, and patient-proximal therapy testing [8].

PDOs serve as powerful platforms for both mechanistic dissection of carcinogenesis and therapeutic biomarker discovery. In a Barrett’s esophagus mouse model, organoids derived from Cck2r+ cardia progenitor cells revealed that mutant p53 promotes direct progression to dysplasia, bypassing the typical metaplastic stage. These organoids exhibited enhanced self-renewal, increased resistance to DNA-damaging agents such as N-methyl-N-nitrosourea (MNU), and retained dysplastic features following orthotopic transplantation [9]. In parallel, another study using breast and lung cancer PDOs stratified by TP53 status demonstrated that combined treatment with talazoparib and temozolomide produced synergistic cytotoxicity exclusively in mutant p53 models. This combination induced sustained DNA double-strand breaks, independent of BRCA1/2 status, and correlated with high PARP1 and mutant p53 co-expression. These findings highlight PDOs as clinically relevant models for linking genotype-specific oncogenic mechanisms with predictive biomarkers for targeted therapy [10].

While PDOs offer a powerful patient-proximal platform, they represent only one component of the broader landscape of preclinical radiotherapy model systems. To contextualize the advantages and limitations of PDOs relative to commonly used 2D monolayer cultures, patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) are commonly employed. A simplified comparative overview is provided in Table 1. This comparison underscores the complementary nature of these systems and clarifies why PDOs occupy a unique intermediate position between reductionist in vitro assays and complex in vivo models.

Table 1.

Comparison of PDOs and common preclinical model systems.

3. Reconstructing the Tumor Microenvironment in Organoids

The tumor microenvironment (TME) refers to the dynamic ecosystem composed of cancer cells and non-malignant stromal, immune, vascular, and extracellular matrix components within and around the tumor mass [11,12,13]. Cancer cells continuously remodel this microenvironment by secreting soluble factors, inducing angiogenesis and establishing systemic immunosuppression, whereas stromal and immune elements in turn shape cancer cell proliferation, survival, and clonal evolution [14,15,16].

3.1. Biomimetic ECM and Decellularized Matrices

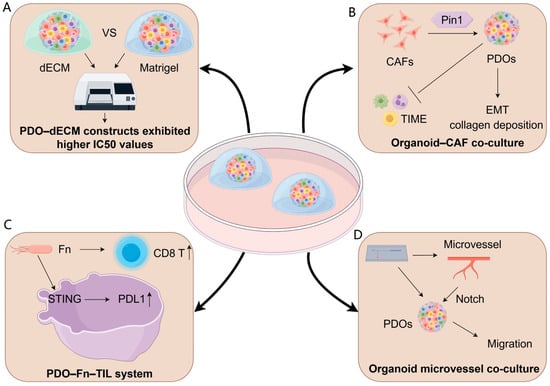

The extracellular matrix (ECM)—a network of structural proteins (e.g., collagens), adhesive glycoproteins (e.g., fibronectin), and glycosaminoglycans (e.g., hyaluronic acid)—regulates tissue morphogenesis and cell identity through biochemical, mechanical, and adhesive cues [17]. In organoid systems, ECM-based hydrogels provide indispensable spatial and mechanical guidance that supports stem cell lineage specification and improves fidelity to in vivo physiology [18,19]. Within the tumor microenvironment (TME), dynamic ECM remodeling promotes growth, invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance via altered stiffness and signaling [20,21], underscoring the need to recreate native ECM architecture for relevant tumor organoid models [22]. Although Matrigel and other basement membrane extracts (BMEs) are widely used, their murine origin, undefined composition, and batch-to-batch variability limit reproducibility and translation [23]. Decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds preserve native tissue-specific biochemical composition and ultrastructure, thereby providing organotypic cues that cannot be recapitulated by conventional basement membrane extracts such as Matrigel. Recently, Sensi et al. generated a fully patient-derived 3D model of high-grade serous ovarian cancer by combining dECM scaffolds from HGSOC specimens and matched PDOs. The detergent–enzymatic decellularization protocol efficiently removed nuclear material while preserving collagen networks, laminin, glycosaminoglycans, and a tissue-specific matrisome, as demonstrated by SHG imaging, Raman spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Importantly, PDOs seeded into HGSOC dECM maintained their histopathological and molecular features and remained viable over prolonged culture. When exposed to paclitaxel or paclitaxel plus carboplatin, PDO–dECM constructs exhibited substantially higher IC50 values than PDOs grown in Geltrex, indicating that patient-derived ECM can attenuate drug sensitivity and better recapitulate in vivo chemoresistance (Figure 1A) [24]. Although this study focused on chemotherapy rather than radiotherapy, it clearly illustrates how patient-derived dECM can modulate treatment response by providing a more realistic mechanical and biochemical microenvironment. Similar dECM–PDO platforms could therefore be leveraged to dissect ECM-driven radioresistance, for example by integrating clinically relevant radiation regimens and readouts of DNA damage repair, clonogenic survival, and inflammatory cell death.

Figure 1.

Reconstructing the tumor microenvironment in organoids. (A) ECM-derived models: Patient-derived decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) scaffolds preserve tumor-specific biochemical and mechanical cues, resulting in PDO–dECM constructs that display higher IC50 values than Matrigel-grown PDOs, indicating ECM-mediated treatment tolerance. (B) Organoid–CAF co-culture: Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) remodel the TME through Pin1-dependent activation, promoting EMT programs, collagen deposition, and broader immunosuppressive TIME modulation, collectively enhancing PDO invasiveness and treatment resistance. (C) PDO–Fn–TIL immune system: Co-culture with Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn) stimulates STING signaling and upregulates PD-L1 expression in PDOs, accompanied by elevated CD8+ T-cell responses, modeling microbe-driven immune modulation. (D) Organoid microvessel co-culture: Endothelialized microvessel-on-chip platforms support direct interactions between PDOs and perfusable vascular structures, enabling Notch-mediated migration and providing a physiologically relevant niche to study vascular–tumor crosstalk.

3.2. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are central architects of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and pivotal mediators of radioresistance (Table 2). Co-culturing CRC organoids with patient-matched CAFs reconstructs TME niches, restoring downregulated pro-tumorigenic transcripts (e.g., REG family, DUOX) and reactivating immune-related programs. This confers proliferative advantages, anti-apoptotic capacity, and chemoresistance—highlighting CAF-enriched niches as essential for CRC malignancy [25].

Mechanistically, organoid–CAF co-cultures identify Pin1 as a critical CAF regulator: Pin1-deficient CAFs fail to promote organoid growth/invasion in vitro and suppress collagen deposition/tumor progression in vivo, positioning stromal Pin1 as a therapeutic target (Figure 1B) [26]

Clinically, CAF-derived gene signatures predict radiotherapy outcomes in prostate cancer [27], while pancreatic CAF heterogeneity (myCAFs vs. iCAFs) dictates tumor behavior and treatment response [28].

Table 2.

Key CAF roles, pathways and interventions implicated in radioresistance.

Table 2.

Key CAF roles, pathways and interventions implicated in radioresistance.

| Study (Year) | Cancer Type | Core CAF Role | Key Pathway(s) | Intervention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang et al., 2023 [29] | ESCC | Collagen I deposition; epithelial–CAF CXCL1 positive feedback | Integrin/FAK–AKT–c-Myc/Chk1; CXCL1/CXCR2–STAT3 | Block collagen/FAK; inhibit CXCL1/CXCR2 |

| Meng et al., 2021 [30] | NSCLC | RT-induced senescent CAFs with SASP | SASP → JAK/STAT3 | Senolytics (e.g., FOXO4-DRI) |

| Xun et al., 2025 [31] | TNBC | CAF exosomal circRNA drives autophagy | circFOXO1–miR-27a-3p–BNIP3; autophagy | Block exosome release/uptake; target circFOXO1/miR-27a-3p |

| Zhang et al., 2025 [32] | NSCLC | CAF-derived FBLN5 impairs ferroptosis | Integrin αVβ5–Src–STAT3 → ACSL4 ↓ → ferroptosis ↓ | Target FBLN5/integrin αVβ5/Src/STAT3; restore ACSL4/ferroptosis |

| Guo et al., 2023 [33] | Breast | CAF-derived IL-6 activates tumor STAT3 | IL-6–JAK/STAT3 | Anti-IL-6/IL-6R; STAT3 inhibitors |

| Huang et al., 2021 [34] | NPC | Senescent CAF SASP with IL-8 promotes survival | IL-8–NF-κB | Block IL-8/CXCR; inhibit NF-κB |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [35] | NSCLC | CAF-driven glycolysis supports tumor DDR | Glycolysis (HK2) → ATM/BRCA1 (DDR) | Inhibit glycolysis + RT |

| Chen et al., 2020 [36] | CRC | CAF exosomal miR-590-3p suppresses CLCA4 | miR-590-3p–CLCA4–PI3K/AKT | Anti-miR-590-3p; restore CLCA4; block exosomes |

3.3. Immune Components: TIL–PDO Co-Cultures

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) critically shape solid tumor immunology, with their abundance, composition, and spatial organization correlating strongly with prognosis across cancer types [37,38,39,40,41]. Co-culture platforms integrating stromal/immune compartments with PDOs recapitulate TME crosstalk while retaining native morphology and immune constituents [42,43]. For instance, melanoma PDOs preserve tumor heterogeneity and diverse immune populations—including T cells and myeloid subsets—enabling immunotherapy screening [42]. Mechanistic studies using autologous TIL-PDO systems reveal that PD-1 blockade activates tumor innate lymphoid cells (TILCs) to sustain antitumor T-cell responses [44,45]. In CRC, Fusobacterium nucleatum enhances PD-L1 blockade efficacy by activating STING/NF-κB pathways, upregulating PD-L1, and recruiting IFN-γ+ CD8+ TILs—validated in PDO co-cultures via suppressed proliferation and induced apoptosis (Figure 1C) [46].

Collectively, TIL-PDO platforms decode mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB), identify microbiota–immune conditioning of therapeutic response, and provide clinically translatable insights.

3.4. Vascularization and Organoid-on-a-Chip(OoC) Platforms

Achieving perfusable, hierarchically organized, and long-term imageable vascular networks is pivotal for advancing tumor organoids from structural mimicry to functional readouts and translational evaluation. The vascular niche not only supplies oxygen and nutrients and establishes mechanical flow fields, but also delivers angiocrine signals that regulate tumor stemness, invasion, and therapeutic response [47]. Persistent limitations in conventional models—namely inadequate vascular network fidelity, incomplete biological realism, and constraints in chip architecture—have consequently catalyzed the rapid development of vascularized OoC systems and diverse vascularization strategies.

To more faithfully recapitulate the perivascular niche and its role in metastasis, Du et al. developed a personalized vascularized OoC. The platform integrates PDOs with self-assembled, perfusable, hierarchical microvascular networks in a multichannel device containing a microvascular channel, an open-top organoid chamber, and a nutrient channel, enabling parallel assays and long-term, high-resolution visualization of tumor–vascular dynamics [23]. In osteosarcoma PDOs, the extent of angiogenesis and directed organoid migration toward vessels aligned with patients’ metastatic outcomes, providing a patient-proximal readout of metastatic propensity. Mechanistically, microvessel co-culture activated Notch signaling to drive migration, while the VEGFR2 inhibitor apatinib selectively suppressed tumor-induced sprouting angiogenesis and reversed microvessel-induced transcriptional changes, with minimal effects on mature vessels (Figure 1D) Collectively, OoC offers a physiologically relevant, personalized testbed for dissecting metastasis biology, stratifying metastatic risk, and evaluating anti-angiogenic therapies.

4. Predicting Radiotherapy Response with PDOs

The clinical impact of targeted and immunotherapies is often limited by primary or acquired resistance, and conventional cell lines insufficiently capture the diversity of therapeutic targets—particularly for rare cancers lacking robust preclinical models [48]. In this context, PDOs show strong concordance with clinical outcomes and have been used to predict chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy efficacy across metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies [49,50], lung cancer [51], pancreatic cancer [52,53], and other tumor types (Table 3).

PDOs provide a powerful platform for predicting radiotherapy response. Hsu et al. showed that PDOs faithfully recapitulate intrinsic tumor radiosensitivity: clonogenic survival curves fitted by the single-hit multi-target (SHMT) model yield quantitative D0 values that track radiation response. Whereas normal colon and adenoma PDOs tend to be radioresistant, a subset of CRC PDOs is markedly radiosensitive, and is frequently associated with homologous recombination defects (mutational signature 3). In rectal cancer, PDO D0 values inversely correlated with clinical response to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT), with radiosensitive PDOs aligning with complete or major regression [54]. Complementing these findings, Mu et al. reported that radioresistant BRAF-mutant CRC organoids mirrored postoperative tumor persistence, while in vitro synergy between 5-FU and radiation paralleled clinical chemoradiation efficacy—together establishing PDOs as a predictive tool for tailoring radiation-based strategies in CRC [55].

Table 3.

Predicting radiotherapy response with PDOs.

Table 3.

Predicting radiotherapy response with PDOs.

| Study (Year) | Cancer Type | PDO RT Assay/Readout | Linked Clinical Endpoint | Predictive Linkage (Concise) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yao et al. (2020) [56] | LARC | Ex vivo CRT exposure; viability/colony formation; DNA damage/apoptosis readouts | Tumor regression grade (TRG, Dworak), clinical complete response (cCR) after neoadjuvant CRT | PDO sensitivity stratified clinical responders vs. non-responders; organoid readouts mirrored TRG/cCR grouping. |

| Ganesh et al. (2019) [57] | CRC | Dose response to RT ± chemo; survival/repair metrics | Tumor downsizing/response to preoperative therapy (endoscopic diameter shrinkage; near/complete clinical response strata) | Concordant ranking between PDO radioresponse and clinical shrinkage strata; proof-of-concept for individualized CRT planning. |

| Issing et al. (2025) [58] | HNSCC | Clonogenic survival after RT; growth rate metrics (GR/GRinf) | Local control/recurrence from linked longitudinal data | GRinf-based stratification associated with recurrence risk; poor radiosensitivity linked to recurrence, favorable linked to ≥2-year non-recurrence. |

| Li et al. (2025) [59] | HNSCC | 0–8 Gy viability dose response (CellTiter-Glo); AUC/curve | Case-level RT response | Case-level concordance observed; small sample size—predictive utility requires larger validation. |

| Mu et al. (2025) [55] | CRC | PDO radioresponse stratified by genotype (e.g., BRAFV600E) | External rectal cohorts: TRG and survival after CRT | BRAFV600E linked to PDO radioresistance; RAF inhibitor + CRT improved PDO response; clinical cohorts confirmed worse TRG and survival in BRAFV600E. |

5. Mechanisms of Radioresistance Elucidated by PDOs

RT deploys high-energy ionizing radiation (IR) to kill tumor cells primarily by compromising DNA integrity and cellular homeostasis. Its cytotoxicity arises through convergent mechanisms: induction of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disruption of cell-cycle progression, and engagement of regulated cell-death pathways such as apoptosis, autophagy, and necrosis [1]. In parallel, IR can elicit immunogenic cell death (ICD), releasing danger-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs)—notably calreticulin, ATP, and HMGB1—to prime antitumor immunity [60].

Despite these effects, radioresistance remains a major barrier to durable control. Five biological programs consistently underpin resistance: (i) augmented DNA damage response (DDR) and repair capacity; (ii) enrichment and plasticity of CSCs; (iii) hypoxia-driven metabolic and redox adaptation; (iv) immune evasion with remodeling of the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME); and (v) radiation-induced senescence. Together, these processes enhance survival, enable recovery from radiation-induced stress, and foster relapse [60]. The following subsections synthesize PDO-based insights into DDR, CSC biology, hypoxia/oxidative stress, and immune remodeling, and outline opportunities for therapeutic intervention.

5.1. DNA Damage Response and Repair Pathways

The capacity of cancer cells to detect, signal, and repair such damage—the DNA damage response (DDR)—is a principal determinant of radiosensitivity. Hyperactivation of DDR pathways enables efficient repair of radiation-induced lesions, thereby promoting survival and fostering treatment resistance. Core DDR nodes include the kinases ATM/ATR and DNA-PKcs, together with effectors such as BRCA1/2 and RAD51 that coordinate non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) to resolve DSBs [61,62,63,64,65]. Pharmacologic inhibition of these pathways—using ATM, ATR, DNA-PK, or PARP inhibitors—can impede repair, increase vulnerability to DNA damage, and ultimately enhance cell death.

PDOs provide a physiologically relevant ex vivo system to interrogate DDR mechanisms and evaluate radiosensitization strategies in gastrointestinal cancers. In gastric cancer, PDO studies showed that targeting MCM6—an oncogenic transcriptional target of YAP—suppresses ATR–Chk1-mediated DDR signaling, thereby sensitizing tumors to 5-FU and irradiation [66]. In CRC, PDOs identified a radioresistant PROX1+ stem/progenitor subpopulation with elevated expression of DDR genes, including components of NHEJ and base excision repair (BER). Following irradiation, PROX1+ cells expand, whereas combining RT with the NHEJ inhibitor SCR7 curtails their survival; conversely, PROX1-deficient organoids display impaired viability after irradiation, underscoring DDR’s role in maintaining resilience [67]. Transcriptomic profiling of rectal cancer organoids (e.g., HUB005, HUB183) further revealed that radioresistant subtypes upregulate numerous DNA repair programs and antioxidant metabolism—particularly the glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC), the rate-limiting enzyme in glutathione synthesis—whereas radiosensitive organoids preferentially activate pro-apoptotic pathways. CRISPR–Cas9 knockout of GCLC markedly augments radiation response, validating GCLC as a radiosensitization target [68]. Other studies targeting DDR pathways have also been conducted using PDOs [69,70,71,72]. Collectively, these findings highlight PDOs as powerful platforms for dissecting DDR-dependent resistance and guiding the development of effective radiosensitizers.

5.2. Cancer Stem Cells

CSCs constitute a functionally distinct tumor subpopulation defined by self-renewal, differentiation plasticity, and strong tumor-initiating capacity [73]. They are key drivers of recurrence, metastasis, and resistance to chemo and radiotherapy [74,75]. PDOs offer a physiologically relevant, heterogeneous ex vivo platform for interrogating CSC-targeted strategies. Mechanistically, CSCs display augmented DNA repair—particularly via HR and NHEJ—together with efficient ROS scavenging, apoptosis resistance, and a quiescent cell cycle state that collectively confer radioresistance. Core developmental pathways (Wnt/β-catenin, Notch, Hedgehog, Hippo) are typically hyperactivated, sustaining stemness under genotoxic stress [76]. Notably, radiation can further exacerbate resistance by inducing dedifferentiation of non-CSCs into CSC-like cells through epigenetic reprogramming and inflammatory cytokine signaling, thereby amplifying intratumoral heterogeneity.

To counter CSC-driven radioresistance, multiple therapeutic avenues have been explored [77,78], including pharmacologic blockade of stemness pathways (e.g., PF-03084014 and MK-0752 for Notch [79]; vismodegib for Hedgehog [80]), metabolic reprogramming [81], and epigenetic modulation (HDAC and DNMT inhibitors). These approaches impair self-renewal, attenuate DNA repair capacity, and enhance radiosensitivity. In colorectal cancer, PDOs preserve stemness features and markers (CD44, CD133, LGR5, ALDH1A1), enabling functional evaluation of anti-CSC regimens. Radiosensitization strategies combining HDAC or Wnt inhibitors with RT reduce post-irradiation regrowth, in part by downregulating CSC markers and diminishing survival of stem-like subpopulations [82].

Organoid models also reveal stem cell-driven differences in radiosensitivity across tissues: small intestinal organoids are more radiation-vulnerable than colonic organoids, consistent with the clinical prevalence of radiation enteritis [83]. Furthermore, small-molecule or antibody inhibitors targeting Wnt, Notch, or the c-KIT/SLUG axis—such as bufalin—can suppress CSC traits, induce apoptosis, and curb organoid growth. Crucially, PDOs capture interpatient variability in drug response, supporting their use in developing personalized, CSC-directed radiosensitization strategies [84].

5.3. Hypoxia, Redox Homeostasis, and Metabolic Adaptation

Tumor hypoxia—a hallmark of many solid malignancies—is one driver of radioresistance [85]. According to the oxygen fixation hypothesis, sufficient molecular oxygen is required to “fix” radiation-induced DNA lesions via ROS. In hypoxic niches, limited oxygen availability dampens ROS generation and reduces DSBs, thereby attenuating radiation efficacy. Beyond limiting ROS-mediated injury, hypoxic tumors reinforce intrinsic defenses by upregulating antioxidant systems—including glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and catalase—which further neutralize ROS and protect against irradiation-induced oxidative stress [86].

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) exemplifies hypoxia-driven radioresistance [87]. Hubert et al. established a three-dimensional, patient-derived GBM organoid platform that spontaneously forms oxygen gradients closely mirroring the in vivo microenvironment. As organoids expand to 3–4 mm in diameter—exceeding the ~200 μm oxygen diffusion limit—they develop an oxygenated periphery and a hypoxic core. Spatial mapping using the hypoxia marker CA-IX delineated these regions, and the core was enriched for a quiescent CSC subpopulation (SOX2-positive, Ki-67-low), recapitulating the biphasic distribution of perivascular versus distal hypoxic niches observed in native tumors. Functionally, following 3 Gy irradiation, CSCs within the hypoxic core exhibited minimal apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3–negative), whereas non-stem cells in oxygenated areas underwent pronounced apoptosis. These findings validate hypoxia as a central determinant of CSC-mediated radioresistance and underscore the unique ability of organoids to preserve spatial heterogeneity (e.g., regional hypoxia, stem-cell hierarchy). Consequently, this platform provides a physiologically relevant setting for screening hypoxia-targeted radiosensitization strategies [88].

5.4. Immune Evasion and TIME Remodeling

Combining RT with immunotherapy (IT) can synergistically enhance antitumor effi-cacy by reshaping the TIME. RT exerts a dual influence: it can potentiate antitumor immunity yet also foster immunosuppressive niches that sustain radioresistance [89].

On the immunostimulatory side, RT induces immunogenic cell death (ICD), marked by calreticulin exposure and ATP/HMGB1 release, thereby promoting dendritic cell (DC) antigen presentation and adaptive immune activation [90,91]. Cytosolic DNA generated by RT activates cGAS–STING signaling, driving type I interferon (IFN) production and DC maturation [92,93]. At higher doses, however, RT can upregulate the exonuclease TREX1, which degrades cytosolic DNA, dampens STING signaling, and blunts immune cell recruitment—illustrating a dose- and context-dependent balance [94]. STING activity is further required for the induction of chemokines and effectors that recruit and sustain T-cell responses.

Organoid models are well suited to interrogate these pathways. In colorectal cancer organoids, pharmacologic inhibition of SIRT2 (AGK2) promotes MLH1 degradation, activates cGAS–STING, elevates type I IFNs and chemokines, and enhances anti–PD-1 efficacy, including in pMMR settings that are typically immunotherapy-refractory [95]. In patient-derived melanoma organoids, the TTK inhibitor OSU13 induces DNA damage and micronuclei formation, triggering robust secretion of CCL5 and CXCL10 and reducing tumor viability. Together, these studies illustrate how organoids can evaluate both direct antitumor effects and the capacity of agents to engage innate immune sensing and remodel the tumor–immune interface [96].

Conversely, RT can drive immunosuppressive remodeling. By inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) and elevating cytokines such as TGF-β and CCL2, RT recruits M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [97]. RT-modulated chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CXCL1, CSF1) further facilitate myeloid infiltration. These cells secrete IL-10, TGF-β, and Arg1, suppressing CD8+ T-cell function and promoting epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and progression [23]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are also recruited via CCL17/CCL22 and suppress effector T cells through IL-10, IL-35, and adenosine [98].

Organoid–immune co-culture systems enable individualized modeling of TIME dynamics under RT and checkpoint blockade. In melanoma, PDO–TIL co-cultures treated with anti-PD-1 show viability changes concordant with clinical responses [99]; in lung cancer organoids, PD-1 blockade reverses T-cell exhaustion and restores effector phenotypes, mirroring in vivo behavior [100]. Overall, organoid platforms bridge mechanistic inquiry and patient-tailored immunotherapy design, particularly for evaluating novel immunomodulators and rational RT–IT combinations.

5.5. Radiation-Induced Senescence in Cancers

RT also induces therapy-induced senescence (TIS), characterized by persistent SA-β-Gal activity and SASP. TIS rewires transcriptional/epigenetic programs and reprograms the tumor microenvironment, thereby seeding post-radiation recurrence and resistance [101,102]. In glioblastoma, an SA-β-Gal+ subpopulation emerging after irradiation upregulates tissue factor F3 (CD142); F3 supports clonal regrowth and, via coagulation and intracellular signaling, drives mesenchymal-like transdifferentiation, enhances chemokine secretion, activates tumor-associated macrophages, and remodels extracellular matrix—collectively fostering a pro-malignant senescence network and radioresistance [103]. Radioresistant states also couple to ferroptosis evasion: senescence-linked IFI16 is upregulated and, through transcription factors such as JUND, induces HMOX1 to reduce lipid peroxidation and ROS/Fe2+, suppressing ferroptosis. Genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of IFI16/HMOX1 reverses these effects and restores radiosensitivity, highlighting a tractable “senescence–ferroptosis” axis [104].

PDOs are pivotal for elucidating these mechanisms because they preserve native architecture and intratumoral heterogeneity, enabling near-physiologic observation of radiation-induced senescence and its upstream triggers. In glioblastoma studies, parallel validation across patient tissue slices and organoids confirms irradiation-induced increases in SA-β-Gal, with F3 induction reproduced in tumor spheres, organoids, and patient sections—providing cross-model evidence for the TIS–F3–microenvironment remodeling–resistance cascade [103]. PDOs also enable functional dissection of senescence–immunity crosstalk: in gastric cancer, AURK inhibitor-treated organoids exhibit canonical senescence (enhanced SA-β-Gal, multinucleation) and secrete high CCL2; in PDO–macrophage co-culture, the CCL2–CCR2 axis recruits and polarizes M2 macrophages, dampening innate tumor cell clearance. This experimentally tractable framework transfers to RT-induced senescence, allowing PDOs to both visualize TIS and reconstruct its immune consequences, while cross-validating with in vivo data [105]. Consequently, PDO platforms are well suited to screen and optimize rational radiosensitizing combinations—such as senolytics, anticoagulation targeting the F3 axis, myeloid reprogramming, and ferroptosis-enhancing strategies—under patient-proximal conditions [103].

5.6. Epigenetic Regulation of Radioresistance

Radioresistance is not solely a consequence of genetic alterations; it is increasingly understood as an epigenetically driven phenotype shaped by DNA methylation, histone modifications, and non-coding RNA–mediated transcriptional programs. Ionizing radiation itself induces broad chromatin remodeling, influencing DDR pathway choice, checkpoint activation, and cell-fate decisions. Recent work demonstrates that these epigenetic layers are essential determinants of whether irradiated cells undergo repair, senescence, or apoptosis [106]. A major advantage of PDOs is their ability to retain patient-specific epigenomic states faithfully. This makes them highly suitable for dissecting epigenetically encoded radioresponse programs. For example, in renal cancer organoid models, epigenetic silencing of KAT2B through promoter hypermethylation was shown to drive metabolic reprogramming and tumor progression; restoration of KAT2B or inhibition of its downstream target of FASN-suppressed organoid growth [107]. Although not a radiotherapy study, this work exemplifies how PDOs can reveal clinically actionable epigenetic vulnerabilities, an approach readily adaptable to radiosensitization research.

Epigenetic dysregulation also plays a role in RT-induced normal tissue toxicity. Human cerebral organoids irradiated in vitro recapitulate the widespread DNA hypomethylation and disruption of neurodevelopmental and inflammatory programs observed in irradiated brain tissue [108]. This demonstrates the value of organoid platforms not only for tumor radioresistance studies but also for understanding—and potentially mitigating—late radiation toxicities.

6. PDO-Enabled Discovery of Radiosensitizers

6.1. Dual-Organoid Strategy for Efficacy–Toxicity Profiling

PDOs have transformed preclinical modeling by preserving the three-dimensional architecture, molecular heterogeneity, and treatment responsiveness of primary tumors. Building on this foundation, paired organoid systems—comprising tumor-derived organoids (PDTOs) and matched normal organoids from the same patient—offer a more comprehensive and clinically relevant framework for therapeutic evaluation. By enabling side-by-side testing under identical conditions, this dual-organoid approach permits simultaneous assessment of tumor-selective radiosensitization and normal tissue toxicity, directly addressing a central challenge in radiotherapy development: optimizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing collateral damage.

In most dual-organoid studies, matched “normal” PDOs are derived from non-malignant epithelium of the same organ as the tumor. For example, Park et al. established paired CRC PDOs and normal colonic PDOs from surgical and endoscopic specimens of colorectal cancer patients. Normal PDOs were generated from adjacent non-tumor mucosa and expanded as epithelial crypt-derived organoids in Matrigel with Wnt agonists, whereas CRC PDOs were selectively maintained in Wnt-free medium, thereby enriching for malignant clones. Using this paired system, butyrate enhanced the effect of fractionated γ-irradiation in CRC PDOs, while sparing or even supporting the regenerative capacity of normal PDOs under the same treatment conditions [109].

Similarly, Nag et al. employed human colonic organoids derived from matched malignant and non-malignant tissues to interrogate auranofin as a combined radioprotector and radiosensitizer [110]. In this setting, auranofin pretreatment protected non-malignant intestinal organoids and mouse crypt epithelium from radiation-induced injury, yet concurrently sensitized malignant colonic organoids and tumors to irradiation. These platforms illustrate that most “normal” PDOs currently used for dual-organoid efficacy–toxicity profiling are purely epithelial cultures embedded in basement membrane extract, without routine co-culture of stromal fibroblasts, endothelial cells, or immune populations. While this design provides a controlled epithelial readout of normal tissue toxicity, it underestimates the contribution of stromal and immune compartments to organ-level toxicity, highlighting an opportunity to extend paired PDO systems towards more complex, TME-informed co-culture configurations in future radiotherapy studies.

6.2. PDO-Guided Design of Nanoradiosensitizers

Nanoparticles can potentiate radiotherapy by amplifying DDR and ROS generation, while also serving as vehicles for targeted drug delivery, oxygen modulation, and multimodal imaging [111,112,113,114]. PDOs have become indispensable for developing and optimizing nanoradiosensitizers because they preserve patient-specific architecture, molecular profiles, and therapeutic responses. Crucially, integrating paired PDTOs with matched normal organoids from the same patient enables concurrent readouts of tumor-selective efficacy and off-target toxicity [115], thereby sharpening estimates of the therapeutic index and accelerating translation.

Recent work illustrates how PDOs inform the rational design of multifunctional nanoplatforms. Using colorectal cancer PDOs, Gu et al. showed that a vitamin K2-based nanobooster (VK-OVA@HMP) augments PDT-induced immunity by promoting immunogenic cell death and dendritic cell maturation, while matched normal organoids confirmed minimal toxicity [23]. Similarly, Ye et al. validated a near infrared-responsive platform (IT-4F NPs) that couples PDT with photothermal effects to trigger robust PANoptosis, a form of inflammatory regulated cell death that integrates pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis, and potent immune activation; the antitumor activity was confined to cancer organoids without impairing paired normal organoids, underscoring selective action [116]. Extending this paradigm to therapy resistance, Chen et al. leveraged paired PDOs from cisplatin-resistant colorectal tumors to evaluate a hypoxia-amplifying, DNA repair-inhibiting nanomedicine (HYDRI NM) [117]. The platform revealed enhanced intracellular hypoxia and selective DDR inhibition in drug-resistant cancer organoids, with negligible cytotoxicity in normal counterparts.

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that paired PDO systems provide a robust, clinically relevant framework to (i) identify patient-specific vulnerabilities (e.g., hypoxia, DDR dependencies), (ii) deconvolute mechanisms of action and selectivity, and (iii) prioritize nanoradiosensitizers with favorable therapeutic indices—thereby accelerating discovery, biomarker development, and personalized translation.

6.3. High-Throughput Organoid Screening for Radiosensitization

High-throughput screening using patient-derived organoids (PDOs) enables systematic identification of radiosensitizers in a clinically relevant context. A 384-well PDO assay was used to test large drug libraries under irradiated and non-irradiated conditions, with radiosensitization quantified by ΔAUC. Across multiple PDOs, RAS–MAPK inhibitors—particularly MEK inhibitors—emerged as consistent radiosensitizing candidates. Multi-dose matrix assays further revealed strong synergy between MEK inhibition, PARP inhibition, and radiation [118]. These findings, validated in PDOs, highlight how organoid-based high-throughput platforms can uncover pathway-level vulnerabilities and guide rational design of effective drug–radiotherapy combinations.

7. Conclusions

PDOs are emerging as a practical bridge between radiobiology and clinical decision-making. By preserving patient-specific genetics, 3D architecture, and key aspects of intratumoral heterogeneity, they can help interrogate drivers of radioresistance —including dysregulated DDR, CSC plasticity, hypoxia and redox imbalance, TIME remodeling, and radiation-induced senescence—and provide patient contexts for exploring rational radiosensitizer combinations. When paired with matched normal organoids, these platforms may also support side-by-side efficacy–toxicity assessment, which is helpful for optimizing therapeutic index and prioritizing candidates for translational testing.

Despite these strengths, important limitations remain. PDO establishment efficiency is highly tumor-type–dependent. While colorectal, gastric, and pancreatic cancers generally show high success rates, deriving stable PDOs from certain malignancies—such as primary prostate cancers, some sarcomas, and heavily pretreated or fibrotic tumors—remains technically challenging. These constraints may introduce selection bias toward more proliferative or treatment-resistant clones, limiting the representativeness of PDO cohorts. Therefore, rigorous validation of PDO fidelity is essential. Standard approaches typically include side-by-side comparisons of PDOs and their parental tumors at the histological level, immunophenotypic profiling to confirm lineage identity, genomic characterization to verify conservation of driver mutations and pathway alterations, and—where available—correlation with clinical radiotherapy responses. Such multilayered benchmarking is critical for establishing that PDOs faithfully model the tumor type from which they are derived.

Another key consideration is the impact of serial passaging. Although major driver mutations often remain stable across early passages, cumulative passaging can modify clonal composition, stem/progenitor fractions, proliferative kinetics, and ultimately radioresponse phenotypes. Inter-passage variability has been reported in both morphological features and treatment sensitivity, underscoring the importance of using early-passage PDOs for predictive modeling, documenting passage numbers in all experiments, and replicating key findings across several passage windows. Systematic future studies quantifying long-term genomic and functional drift will be essential for defining the “predictive window” during which PDOs retain maximal biological relevance.

Emerging standardization efforts—such as those led by the EORTC and NIH PDO consortia—are now establishing unified protocols and quality benchmarks, which will be essential for ensuring reproducibility and advancing PDO-based radiotherapy models toward clinical validation. Future work should prioritize the development of standardized PDO culture and irradiation workflows capable of modeling clinically relevant fractionation schemes. By integrating advanced irradiation platforms (including micro-field and ultra-high-precision dose delivery), longitudinal live imaging, and computational modeling, PDO systems may more faithfully recapitulate the classical “4R” radiobiological processes—repair, repopulation, reoxygenation, and redistribution—thereby greatly enhancing their value in predicting individualized radiotherapy responses and enabling the discovery of novel radiosensitizers.

Looking ahead, the convergence of PDOs with high-content imaging, single-cell and spatial omics, CRISPR functional genomics, biomimetic ECM engineering and advanced irradiation platforms—including FLASH, proton, and carbon-ion radiotherapy—will accelerate the discovery of actionable resistance mechanisms and clinically tractable radiosensitizers. The integration of machine learning-based response modeling and larger biobank-linked PDO cohorts will further support individualized radiotherapy stratification. Continued refinement of culture conditions, stromal co-culture systems, and passage-aware quality control frameworks will be essential for unlocking the full potential of PDOs as next-generation tools for mechanistic studies, therapeutic screening, and personalized clinical decision-making in radiation oncology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.Y. and Z.W.; methodology, D.Y., X.H., and X.W.; software, X.W. and W.D.; validation, D.Y., X.H., X.W., and W.D.; formal analysis, D.Y. and X.W.; investigation, D.Y., X.H., W.D., C.W., J.Q., and Y.Z.; resources, C.S. and Z.W.; data curation, W.D., X.W., C.W., J.Q., and Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.Y. and X.H.; writing—review and editing, D.Y., X.H., X.W., W.D., C.W., J.Q., Y.Z., C.S., and Z.W.; visualization, X.W. and D.Y.; supervision, Z.W. and C.S.; project administration, Z.W.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by “National Natural Science Foundation of China; grant number 82172679” and “The APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China; grant number 82172679”.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During manuscript preparation, DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp was used solely for language polishing. The authors reviewed all output and assume full responsibility for the published content. All figures were created by Figdraw and exported under the following IDs for copyright verification: YIOYP884fe and OYWRI0c53e. All tables included in the manuscript were created entirely by the authors and are original works. They were not reproduced, adapted, or modified from any previously published materials. Therefore, no copyright permission is required for the tables.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BED | Biologically effective dose |

| CAF | Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CIRT | Carbon-ion radiotherapy |

| CRT | Chemoradiotherapy |

| cCR | Clinical complete response |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ESCC | Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| FLASH | Ultra-high dose rate radiotherapy |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| GR | Growth rate |

| GRinf | Growth rate at infinite time |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| LARC | Local advanced rectal cancer |

| LET | Linear energy transfer |

| NPC | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| OoC | Organoid-on-a-chip |

| PBT | Proton beam therapy |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PDO | Patient-derived organoid |

| PDX | Patient-derived xenograft |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RT | Radiotherapy |

| SA-β-Gal | Senescence-associated β-galactosidase |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SF2 | Surviving fraction at 2 Gy |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TNBC | Triple-negative Breast Cancer |

| TIL | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte |

| TIS | Therapy-induced senescence |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TF | Tissue factor (gene F3) |

| TRG | Tumor Regression Grade |

| γH2AX | Phosphorylated H2AX (Ser139), a DSB marker |

| D0 | Mean lethal dose (single-hit model) |

References

- An, L.; Li, M.; Jia, Q. Mechanisms of radiotherapy resistance and radiosensitization strategies for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Yang, S.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiang, Z. Transcriptomic analysis of tumor tissues and organoids reveals the crucial genes regulating the proliferation of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklinska-Schirtz, B.J.; Venkateswaran, S.; Anbazhagan, M.; Kolachala, V.L.; Prince, J.; Dodd, A.; Chinnadurai, R.; Gibson, G.; Denson, L.A.; Cutler, D.J.; et al. Ileal Derived Organoids From Crohn’s Disease Patients Show Unique Transcriptomic and Secretomic Signatures. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 12, 1267–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Han, S. Application of Radiosensitizers in Cancer Radiotherapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021, 16, 1083–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; Van De Wetering, M.; Barker, N.; Stange, D.E.; Van Es, J.H.; Abo, A.; Kujala, P.; Peters, P.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 Stem Cells Build Crypt-Villus Structures in Vitro without a Mesenchymal Niche. Nature 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Stange, D.E.; Ferrante, M.; Vries, R.G.J.; Van Es, J.H.; Van Den Brink, S.; Van Houdt, W.J.; Pronk, A.; Van Gorp, J.; Siersema, P.D.; et al. Long-term Expansion of Epithelial Organoids From Human Colon, Adenoma, Adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s Epithelium. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1762–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van De Wetering, M.; Francies, H.E.; Francis, J.M.; Bounova, G.; Iorio, F.; Pronk, A.; Van Houdt, W.; Van Gorp, J.; Taylor-Weiner, A.; Kester, L.; et al. Prospective derivation of a living organoid biobank of colorectal cancer patients. Cell 2015, 161, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, M.; Hao, X.; Ning, J.; Zhou, X.; Gong, Y.; Lang, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhang, J.; Ding, S. Patient-derived organoid culture of gastric cancer for disease modeling and drug sensitivity testing. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, G.; Malagola, E.; Wei, C.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, J.; Hata, M.; Kobayashi, H.; Ochiai, Y.; Zheng, B.; Zhi, X.; et al. p53 mutation biases squamocolumnar junction progenitor cells towards dysplasia rather than metaplasia in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut 2024, 74, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madorsky Rowdo, F.P.; Xiao, G.; Khramtsova, G.F.; Nguyen, J.; Martini, R.; Stonaker, B.; Boateng, R.; Oppong, J.K.; Adjei, E.K.; Awuah, B.; et al. Patient-derived tumor organoids with p53 mutations, and not wild-type p53, are sensitive to synergistic combination PARP inhibitor treatment. Cancer Lett. 2024, 584, 216608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, K.T.P.M.; Adema, G.J.; Bussink, J.; Ansems, M. Cancer-associated fibroblasts, tumor and radiotherapy: Interactions in the tumor micro-environment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahai, E.; Astsaturov, I.; Cukierman, E.; DeNardo, D.G.; Egeblad, M.; Evans, R.M.; Fearon, D.; Greten, F.R.; Hingorani, S.R.; Hunter, T.; et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palucka, A.K.; Coussens, L.M. The basis of oncoimmunology. Cell 2016, 164, 1233–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fridman, W.H.; Zitvogel, L.; Sautès-Fridman, C.; Kroemer, G. The immune contexture in cancer prognosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, R.D.; Old, L.J.; Smyth, M.J. Cancer Immunoediting: Integrating Immunity’s Roles in Cancer Suppression and Promotion. Science 2011, 331, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreta, E.; Moya-Rull, D.; Marco, A.; Amato, G.; Ullate-Agote, A.; Tarantino, C.; Gallo, M.; Esporrín-Ubieto, D.; Centeno, A.; Vilas-Zornoza, A.; et al. Natural Hydrogels Support Kidney Organoid Generation and Promote In Vitro Angiogenesis. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, e2400306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosquera, M.J.; Kim, S.; Bareja, R.; Fang, Z.; Cai, S.; Pan, H.; Asad, M.; Martin, M.L.; Sigouros, M.; Rowdo, F.M.; et al. Extracellular Matrix in Synthetic Hydrogel-Based Prostate Cancer Organoids Regulate Therapeutic Response to EZH2 and DRD2 Inhibitors. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, e2100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Weaver, V.M.; Werb, Z. The extracellular matrix: A dynamic niche in cancer progression. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebersold, R.; Mann, M. Mass-spectrometric exploration of proteome structure and function. Nature 2016, 537, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondani, G.; Zeeberg, K.; Greco, M.R.; Cannone, S.; Dando, I.; Pozza, E.D.; Mastrodonato, M.; Forciniti, S.; Casavola, V.; Palmieri, M.; et al. Extracellular matrix composition modulates PDAC parenchymal and stem cell plasticity and behavior through the secretome. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 2104–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Zhou, X.; Wang, S.; Trinkle, C. Tumor organoid models in precision medicine and investigating cancer-stromal interactions. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 218, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bao, Q.; Xu, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, Q.; Liu, F.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Personalized Vascularized Tumor Organoid-on-a-Chip for Tumor Metastasis and Therapeutic Targeting Assessment. Adv. Mater. 2024, 37, e2412815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sensi, F.; Spagnol, G.; Repetto, O.; D’ANgelo, E.; Biccari, A.; Marangio, A.; Guerriero, A.; Castillo, A.A.M.; Vogliardi, A.; Zanrè, E.; et al. Patient-derived extracellular matrix from decellularized high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma tissues as a biocompatible support for organoid growth. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 61, 102523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naruse, M.; Ochiai, M.; Sekine, S.; Taniguchi, H.; Yoshida, T.; Ichikawa, H.; Sakamoto, H.; Kubo, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Ochiai, A.; et al. Re-expression of REG family and DUOXs genes in CRC organoids by co-culturing with CAFs. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koikawa, K.; Kibe, S.; Suizu, F.; Sekino, N.; Kim, N.; Manz, T.D.; Pinch, B.J.; Akshinthala, D.; Verma, A.; Gaglia, G.; et al. Targeting Pin1 renders pancreatic cancer eradicable by synergizing with immunochemotherapy. Cell 2021, 184, 4753–4771.e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, F. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived gene signatures predict radiotherapeutic survival in prostate cancer patients. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlund, D.; Handly-Santana, A.; Biffi, G.; Elyada, E.; Almeida, A.S.; Ponz-Sarvise, M.; Corbo, V.; Oni, T.E.; Hearn, S.A.; Lee, E.J.; et al. Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 579–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Fan, W.; Zhong, C.; Liu, T.; Cheng, G.; Zhu, L.; Liu, Q.; Xi, Y.; et al. Collagen 1-mediated CXCL1 secretion in tumor cells activates fibroblasts to promote radioresistance of esophageal cancer. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Li, Y.; Wan, C.; Sun, Y.; Dai, X.; Huang, J.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Targeting senescence-like fibroblasts radiosensitizes non–small cell lung cancer and reduces radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 6, e146334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xun, X.; Hu, H.; Liu, Q.; Su, R.; Ai, J. CAFs exosomal circFOXO1 promotes TNBC autophagy and radioresistance via miR-27a-3p/BNIP3 axis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 29273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Yan, W.; Yuan, J.; Ma, Y.; Ren, Z.; Chen, X.; Lv, J.; Wu, M.; Yu, J.; Chen, D. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived fibulin-5 promotes radioresistance in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Fu, Y.; Kuang, J.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Lin, J.; Lin, S.; Wu, D.; Xie, G. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce growth and radioresistance of breast cancer cells through paracrine IL-6. Cell Death Discov. 2023, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhang, L.; Yang, M.; Wu, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Yuan, L.; Pan, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote the survival of irradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via the NF-κB pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, L.; Yue, J.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Q.; Zhou, R.; Yin, Z.; Ma, S.; Ke, Y. Cancer-associated fibroblasts facilitate DNA damage repair by promoting the glycolysis in non-small cell lung cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, J. Exosomal miR-590-3p derived from cancer-associated fibroblasts confers radioresistance in colorectal cancer. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2021, 24, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimbeni, B.T.; Giudici, F.; Pescia, C.; Giachetti, P.P.M.B.; Scafetta, R.; Zagami, P.; Marra, A.; Trapani, D.; Esposito, A.; Scagnoli, S.; et al. Prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in HER2+ metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line treatment. npj Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, V.; Salazar, R.; Gruber, S. The prognostic value of TILs in stage III colon cancer must consider sidedness. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 33, 1094–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-L.; Yu, X.; Mao, X.; Jin, F. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in DCIS: A meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Li, S.; He, L.; Chen, N. Prognostic implications of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1476365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Zhang, P.; Han, Y.; Shen, H.; Zeng, S. Combined tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and microsatellite instability status as prognostic markers in colorectal cancer. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 787–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, L.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; Guan, L.; Shen, L.; Luo, R.; Elder, D.E.; Huang, A.C.; Karakousis, G.; et al. Patient-derived melanoma organoid models facilitate the assessment of immunotherapies. EBioMedicine 2023, 92, 104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magré, L.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; Buschow, S.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; Peppelenbosch, M.; Desai, J. Emerging organoid-immune co-culture models for cancer research: From oncoimmunology to personalized immunotherapies. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moral, J.A.; Leung, J.; Rojas, L.A.; Ruan, J.; Zhao, J.; Sethna, Z.; Ramnarain, A.; Gasmi, B.; Gururajan, M.; Redmond, D.; et al. ILC2s amplify PD-1 blockade by activating tissue-specific cancer immunity. Nature 2020, 579, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, O.; Vivier, E. Immuno-Oncology beyond TILs: Unleashing TILCs. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Bi, D.; Xie, R.; Li, M.; Guo, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Fang, J.; Ding, T.; Zhu, H.; et al. Fusobacterium nucleatum enhances the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.-I.; Jang, S.I.; Hong, J.; Kim, C.H.; Kwon, S.S.; Park, J.S.; Lim, J.-B. Cancer-initiating cells in human pancreatic cancer organoids are maintained by interactions with endothelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2021, 498, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, D.; He, A.; Zhou, R.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Gong, T.; Kang, W.; Lin, X.; Wang, X.; Consortium, P.D.O.D.S.T.; et al. Building consensus on the application of organoid-based drug sensitivity testing in cancer precision medicine and drug development. Theranostics 2024, 14, 3300–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogiannis, G.; Hedayat, S.; Vatsiou, A.; Jamin, Y.; Fernández-Mateos, J.; Khan, K.; Lampis, A.; Eason, K.; Huntingford, I.; Burke, R.; et al. Patient-derived organoids model treatment response of metastatic gastrointestinal cancers. Science 2018, 359, 920–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogenson, T.L.; Xie, H.; Phillips, W.J.; Toruner, M.D.; Li, J.J.; Horn, I.P.; Kennedy, D.J.; Almada, L.L.; Marks, D.L.; Carr, R.M.; et al. Culture media composition influences patient-derived organoid ability to predict therapeutic responses in gastrointestinal cancers. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 7, e158060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-M.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Peng, K.-C.; Chen, Z.-X.; Su, J.-W.; Li, Y.-F.; Li, W.-F.; Gao, Q.-Y.; Zhang, S.-L.; Chen, Y.-Q.; et al. Using patient-derived organoids to predict locally advanced or metastatic lung cancer tumor response: A real-world study. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 100911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Tang, S.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, X.; Han, M.; Liu, Z.; et al. Integrated profiling of human pancreatic cancer organoids reveals chromatin accessibility features associated with drug sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, A.K.; Schütte, L.; Scheible, J.; Roger, E.; Müller, M.; Perkhofer, L.; Kestler, A.M.T.U.; Kraus, J.M.; Kestler, H.A.; Barth, T.F.E.; et al. A Prospective Feasibility Trial to Challenge Patient–Derived Pancreatic Cancer Organoids in Predicting Treatment Response. Cancers 2021, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.-S.; Adileh, M.; Martin, M.L.; Makarov, V.; Chen, J.; Wu, C.; Bodo, S.; Klingler, S.; Sauvé, C.-E.G.; Szeglin, B.C.; et al. Colorectal Cancer Develops Inherent Radiosensitivity That Can Be Predicted Using Patient-Derived Organoids. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 2298–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, P.; Mo, S.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Lv, T.; Xu, R.; He, L.; Xia, F.; Zhou, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Unveiling radiobiological traits and therapeutic responses of BRAFV600E-mutant colorectal cancer via patient-derived organoids. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhu, J.; Wan, J.; Shen, L.; Xia, F.; Fu, G.; Deng, Y.; Pan, M.; et al. Patient-Derived Organoids Predict Chemoradiation Responses of Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 17–26.E16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, K.; Wu, C.; O’rOurke, K.P.; Szeglin, B.C.; Zheng, Y.; Sauvé, C.-E.G.; Adileh, M.; Wasserman, I.; Marco, M.R.; Kim, A.S.; et al. A rectal cancer organoid platform to study individual responses to chemoradiation. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1607–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issing, C.; Menche, C.; Richter, M.R.; Mosa, M.H.; von der Grün, J.; Fleischmann, M.; Thoenissen, P.; Winkelmann, R.; Darvishi, T.; Loth, A.G.; et al. Head and neck tumor organoid biobank for modelling individual responses to radiation therapy according to the TP53/HPV status. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Nishino, M.; Reed, E.; Akshinthala, D.; Pasha, H.A.; Anderson, E.S.; Huang, L.; Hebestreit, H.; Monti, S.; Gomez, E.D.; et al. Head and neck tumor organoid grown under simplified media conditions model tumor biology and chemoradiation responses. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Yin, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yin, J.; Tang, Q.; Xu, M.; Wu, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, H.; et al. STC2 activates PRMT5 to induce radioresistance through DNA damage repair and ferroptosis pathways in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Redox Biol. 2023, 60, 102626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.L.; Southgate, H.; Tweddle, D.A.; Curtin, N.J. DNA damage checkpoint kinases in cancer. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2020, 22, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Dai, Y.; Han, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, J.; Zhou, Z. Structural insight into BRCA1-BARD1 complex recruitment to damaged chromatin. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 2765–2777.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, R.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, W.; Jasin, M. Homologous Recombination and Human Health: The Roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and Associated Proteins. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a016600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazayeri, A.; Falck, J.; Lukas, C.; Bartek, J.; Smith, G.C.M.; Lukas, J.; Jackson, S.P. ATM- and cell cycle-dependent regulation of ATR in response to DNA double-strand breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006, 8, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, R.A. Recognition of DNA double strand breaks by the BRCA1 tumor suppressor network. Chromosoma 2008, 117, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, W.; Yan, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cheung, A.H.K.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B.; Liang, L.; Zhou, Z.; et al. MCM6 is a critical transcriptional target of YAP to promote gastric tumorigenesis and serves as a therapeutic target. Theranostics 2022, 12, 6509–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, P.; Bessone, C.; Seyednasrollah, F.; Brodkin, J.; Lassila, M.; Högström, J.; González-Loyola, A.; Petrova, T.V.; Haglund, C.; Alitalo, K. A Multipotent PROX1+ Tumor Stem/Progenitor Cell Population Emerges During Intestinal Tumorigenesis and Mediates Radioresistance in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andel, D.; Nouwens, A.J.; Klaassen, S.; Laoukili, J.; Viergever, B.; Verheem, A.; Intven, M.P.W.; Zandvliet, M.; Hagendoorn, J.; Rinkes, I.H.M.B.; et al. Rational design of alternative treatment options for radioresistant rectal cancer using patient-derived organoids. Br. J. Cancer 2025, 132, 973–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martincuks, A.; Zhang, C.; Austria, T.; Li, Y.-J.; Huang, R.; Santiago, N.L.; Kohut, A.; Zhao, Q.; Borrero, R.M.; Shen, B.; et al. Targeting PARG induces tumor cell growth inhibition and antitumor immune response by reducing phosphorylated STAT3 in ovarian cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e007716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awasthi, S.; Dobrolecki, L.E.; Sallas, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Khazaei, S.; Ghosh, S.; Jeter, C.R.; Liu, J.; Mills, G.B.; et al. UBA1 inhibition sensitizes cancer cells to PARP inhibitors. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caggiano, C.; Petrera, V.; Ferri, M.; Pieraccioli, M.; Cesari, E.; Di Leone, A.; Sanchez, M.A.; Fabi, A.; Masetti, R.; Naro, C.; et al. Transient splicing inhibition causes persistent DNA damage and chemotherapy vulnerability in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, S.B.; Upstill-Goddard, R.; Paulus-Hock, V.; Paris, C.; Lampraki, E.-M.; Dray, E.; Serrels, B.; Caligiuri, G.; Rebus, S.; Plenker, D.; et al. Targeting DNA Damage Response and Replication Stress in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 362–377.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visvader, J.E.; Lindeman, G.J. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: Accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, M.S.; Ward, C.M.; Davies, C.C. DNA Repair and Therapeutic Strategies in Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Urbano, M.A.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; Marchal, J.A.; Núñez, M.I. CSC Radioresistance: A Therapeutic Challenge to Improve Radiotherapy Effectiveness in Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, J.A.; Monge, C.; Yang, Y.; Takebe, N. Targeting signalling pathways and the immune microenvironment of cancer stem cells—A clinical update. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 17, 204–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Gao, F.; Gao, W.; Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Zhou, H.; Luo, A.; et al. Bismuth Sulfide Nanoflowers Facilitated miR339 Delivery to Overcome Stemness and Radioresistance through Ubiquitin-Specific Peptidase 8 in Esophageal Cancer. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 19232–19246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Fan, H.; Deng, J.; Jiang, K.; Liao, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, M.; Peng, Z. BMI1 Silencing Liposomes Suppress Postradiotherapy Cancer Stemness against Radioresistant Hepatocellular Carcinoma. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 23405–23421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.X.; Xu, A.; Zhang, C.C.; Olson, P.; Chen, L.; Lee, T.K.; Cheung, T.T.; Lo, C.M.; Wang, X.Q. Notch Inhibitor PF-03084014 Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Growth and Metastasis via Suppression of Cancer Stemness due to Reduced Activation of Notch1–Stat3. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1531–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Fang, H.; Hong, L.; Shao, L.; Wang, L.; Wu, J. Deciphering colorectal cancer radioresistance and immune microenvironment: Unraveling the role of EIF5A through single-cell RNA sequencing and machine learning. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1466226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Ji, X.; Xie, H.; Ma, J.; Xu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, N.; Wang, H.; Fan, C.; Song, H. Targeted Reprogramming of Vitamin B3 Metabolism as a Nanotherapeutic Strategy towards Chemoresistant Cancers. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, e2301257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, H.; Kondo, J.; Onuma, K.; Ohue, M.; Inoue, M. Small subset of Wnt-activated cells is an initiator of regrowth in colorectal cancer organoids after irradiation. Cancer Sci. 2020, 111, 4429–4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.L.; Adileh, M.; Hsu, K.-S.; Hua, G.; Lee, S.G.; Li, C.; Fuller, J.D.; Rotolo, J.A.; Bodo, S.; Klingler, S.; et al. Organoids Reveal That Inherent Radiosensitivity of Small and Large Intestinal Stem Cells Determines Organ Sensitivity. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Q.; Qu, D.; Chandrakesan, P.; Feng, H.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Liao, Z.; Du, J.; et al. Bufalin Inhibits Tumorigenesis, Stemness, and Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Colorectal Cancer through a C-Kit/Slug Signaling Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.M.; Fok, M.; Grundy, G.; Parsons, J.L.; Rocha, S. The role of autophagy in hypoxia-induced radioresistance. Radiother. Oncol. 2023, 189, 109951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Hu, C.; Zheng, X.; Sun, C.; Li, Q. Feedback loop between hypoxia and energy metabolic reprogramming aggravates the radioresistance of cancer cells. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhu, K.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Xia, Z.; Ren, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, C. Hypoxia-Induced Autophagy Is Involved in Radioresistance via HIF1A-Associated Beclin-1 in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Heliyon 2023, 9, e12820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, C.G.; Rivera, M.; Spangler, L.C.; Wu, Q.; Mack, S.C.; Prager, B.C.; Couce, M.; McLendon, R.E.; Sloan, A.E.; Rich, J.N. A Three-Dimensional Organoid Culture System Derived from Human Glioblastomas Recapitulates the Hypoxic Gradients and Cancer Stem Cell Heterogeneity of Tumors Found In Vivo. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2465–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharabi, A.B.; Lim, M.; DeWeese, T.L.; Drake, C.G. Radiation and checkpoint blockade immunotherapy: Radiosensitisation and potential mechanisms of synergy. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, e498–e509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Shao, Z.; Wen, X.; Qu, D.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X.; Zhang, L. HMGB1/TREM2 positive feedback loop drives the development of radioresistance and immune escape of glioblastoma by regulating TLR4/Akt signaling. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Ye, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, B.; Tang, J.; Feng, G.; Li, Z.; et al. Susceptibility of Mitophagy-Deficient Tumors to Ferroptosis Induction by Relieving the Suppression of Lipid Peroxidation. Adv. Sci. 2024, 12, e2412593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselbaum, R.R.; Liang, H.; Deng, L.; Fu, Y.-X. Radiotherapy and immunotherapy: A beneficial liaison? Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.M.; Vanpouille-Box, C.; Spada, S.; Rudqvist, N.-P.; Chapman, J.R.; Ueberheide, B.M.; Pilones, K.A.; Sarfraz, Y.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. Exosomes Shuttle TREX1-Sensitive IFN-Stimulatory dsDNA from Irradiated Cancer Cells to DCs. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2018, 6, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Alard, A.; Aryankalayil, M.J.; Sarfraz, Y.; Diamond, J.M.; Schneider, R.J.; Inghirami, G.; Coleman, C.N.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yang, L.; Ye, S.; Mai, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Feng, X.; Yang, Z. Targeting SIRT2 induces MLH1 deficiency and boosts antitumor immunity in preclinical colorectal cancer models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2025, 17, eadv0766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, V.; Kumar, A.; Wang, Y.; Roychowdhury, N.; Bellan, D.d.L.; Kassaye, B.B.; Watkins, R.; Capece, M.; Chung, C.G.; Hilinski, G.; et al. TTK inhibitor OSU13 promotes immunotherapy responses by activating tumor STING. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 9, e177523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xin, Z.; Wu, D.; Ni, C.; Huang, J.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, T. Radiation-induced tumor immune microenvironments and potential targets for combination therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, D.; Yu, J. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: The dawn of cancer treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votanopoulos, K.I.; Forsythe, S.; Sivakumar, H.; Mazzocchi, A.; Aleman, J.; Miller, L.; Levine, E.; Triozzi, P.; Skardal, A. Model of Patient-Specific Immune-Enhanced Organoids for Immunotherapy Screening: Feasibility Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2019, 27, 1956–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, N.; Hoshi, H.; Higa, A.; Hiyama, G.; Tamura, H.; Ogawa, M.; Takagi, K.; Goda, K.; Okabe, N.; Muto, S.; et al. An In Vitro System for Evaluating Molecular Targeted Drugs Using Lung Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids. Cells 2019, 8, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoetz, U.; Klein, D.; Hess, J.; Shnayien, S.; Spoerl, S.; Orth, M.; Mutlu, S.; Hennel, R.; Sieber, A.; Ganswindt, U.; et al. Early senescence and production of senescence-associated cytokines are major determinants of radioresistance in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Kohli, J.; Demaria, M. Senescent Cells in Cancer Therapy: Friends or Foes? Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 838–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.-M.; Kim, J.-Y.; Cho, H.J.; Lee, W.J.; Nguyen, D.; Kim, S.S.; Oh, Y.T.; Kim, H.-J.; Jung, C.-W.; Pinero, G.; et al. Tissue factor is a critical regulator of radiation therapy-induced glioblastoma remodeling. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1480–1497.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Cai, L.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Jin, X.; Bai, Y.; Lai, M.; Li, H.; et al. Cellular senescence-associated gene IFI16 promotes HMOX1-dependent evasion of ferroptosis and radioresistance in glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Kwan, W.; Du, Y.; Yan, R.; Zang, L.; Li, C.; Zhu, Z.; Cheong, I.H.; Kozlakidis, Z.; Yu, Y. Drug-induced senescence by aurora kinase inhibitors attenuates innate immune response of macrophages on gastric cancer organoids. Cancer Lett. 2024, 598, 217106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishido, K.; Reinders, A.; Asuthkar, S. Epigenetic regulation of radioresistance: Insights from preclinical and clinical studies. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2022, 31, 1359–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Miao, D.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Dong, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, H.; Wang, K.; Xiong, Z.; et al. Epigenetically silenced KAT2B suppresses de novo lipogenesis through destroying HDAC5/LSD1 complex assembly in renal cell carcinoma. J. Adv. Res. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millner, T.O.; Panday, P.; Xiao, Y.; Nicholson, J.G.; Boot, J.R.; Arpe, Z.; Stevens, P.A.; Rahman, N.N.; Zhang, X.; Mein, C.; et al. Disruption of DNA methylation underpins the neuroinflammation induced by targeted CNS radiotherapy. Brain 2025, 148, 3137–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Kwon, J.; Shin, H.J.; Moon, S.M.; Kim, S.B.; Shin, U.S.; Han, Y.H.; Kim, Y. Butyrate enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy via FOXO3A in colorectal cancer patient-derived organoids. Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, D.; Bhanja, P.; Riha, R.; Sanchez-Guerrero, G.; Kimler, B.F.; Tsue, T.T.; Lominska, C.; Saha, S. Auranofin Protects Intestine against Radiation Injury by Modulating p53/p21 Pathway and Radiosensitizes Human Colon Tumor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 4791–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Meng, F.; Luo, L.; Tian, S.; Liu, B. Carbon–Iodine Polydiacetylene Nanofibers for Image-Guided Radiotherapy and Tumor-Microenvironment-Enhanced Radiosensitization. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 8325–8336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Gao, L. The Refined Application and Evolution of Nanotechnology in Enhancing Radiosensitivity During Radiotherapy: Transitioning from Gold Nanoparticles to Multifunctional Nanomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 6233–6256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Shao, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Qiu, H.; Ding, X.; Qu, D.; Wang, H.; Wang, A.Z.; Zhang, L. A multifunctional targeted nano-delivery system with radiosensitization and immune activation in glioblastoma. Radiat. Oncol. 2024, 19, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, A.; Arora, V.; Kumari, S.; Sarkar, A.; Kumaran, S.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Jain, T.K.; Agrawal, G. Imaging application and radiosensitivity enhancement of pectin decorated multifunctional magnetic nanoparticles in cancer therapy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 189, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J.; Zhu, R.; Liang, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Zhao, S.; Wu, Y.; Cao, J.; Yang, S.; Sun, Y. Molecular simulation-aided self-adjuvanting nanoamplifier for cancer photoimmunotherapy. Theranostics 2025, 15, 2451–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, S.; Pang, E.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, P.; Gao, W.; Diao, Q.; Yu, J.; Zeng, J.; Lan, M.; et al. Indacenodithienothiophene-based A-D-A-type phototheranostics for immuno-phototherapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2025, 23, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]