Abstract

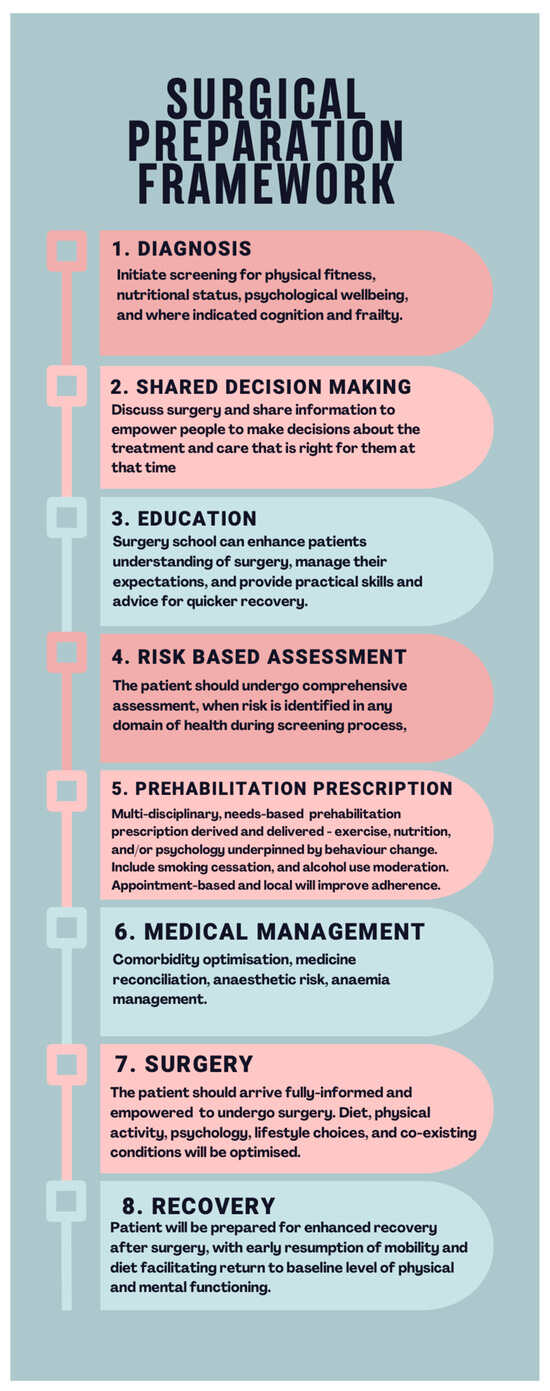

Cancer surgery is an essential treatment strategy but can disrupt patients’ physical and psychological health. With worldwide demand for surgery expected to increase, this review aims to raise awareness of this global public health concern, present a stepwise framework for preoperative risk evaluation, and propose the adoption of personalised prehabilitation to mitigate risk. Perioperative medicine is a growing speciality that aims to improve clinical outcome by preparing patients for the stress associated with surgery. Preparation should begin at contemplation of surgery, with universal screening for established risk factors, physical fitness, nutritional status, psychological health, and, where applicable, frailty and cognitive function. Patients at risk should undergo a formal assessment with a qualified healthcare professional which informs meaningful shared decision-making discussion and personalised prehabilitation prescription incorporating, where indicated, exercise, nutrition, psychological support, ‘surgery schools’, and referral to existing local services. The foundational principles of prehabilitation can be adapted to local context, culture, and population. Clinical services should be co-designed with all stakeholders, including patient representatives, and require careful mapping of patient pathways and use of multi-disciplinary professional input. Future research should optimise prehabilitation interventions, adopting standardised outcome measures and robust health economic evaluation.

1. Introduction

Cancer treatment heavily relies on surgery, encompassing preventative, diagnostic, curative, palliative, and reconstructive interventions [1]. However, these procedures, while essential, introduce considerable trauma and physiological disruption, posing substantial risks to patients’ physical and psychological well-being. Despite advancements such as enhanced recovery programs, minimally invasive surgical techniques, and robotic surgery, elective cancer surgery remains associated with a notable mortality risk [2]. The prevalent focus on traditional short-term reporting potentially obscures the full scale of the issue, given the consideration of ‘late mortality’ occurring between days 31 and 90, or even later [3]. Estimates of postoperative morbidity vary based on factors such as heterogenous outcome reporting, level of hospital infrastructure [4], surgical site, and complexity [5]; however, the considerable impacts on patients, families, and global healthcare systems are widely acknowledged [2,5,6]. Urgent and elective cancer surgeries exhibit similarly unfavourable outcomes [7]. Notably, over half of patients aged 60 and above who undergo major abdominal surgery fail to regain their preoperative functional capacity, quality of life, or physical fitness [8,9]. Perioperative risk is multi-factorial, a function of preoperative condition of the patient, surgical complexity, and anaesthetic administration. Cancer patients face particular burden due to the deconditioning nature of disease, and neoadjuvant treatment and potential for multiple exposures to anaesthetics during diagnostic and treatment phases [10]. The projected economic toll from 2015 to 2030, solely due to productivity loss, is estimated at USD 12.3 trillion, amplifying health inequalities and spiralling economic harm [4].

Global population estimates anticipate a doubling of individuals aged over 65 between 2025 and 2050, reaching 1.6 billion [11]. As a consequence of the striking association between old age and cancer incidence, the projected annual count of cancer surgeries worldwide is expected to rise from 30 million in 2015 to 45 million by 2030 [1].

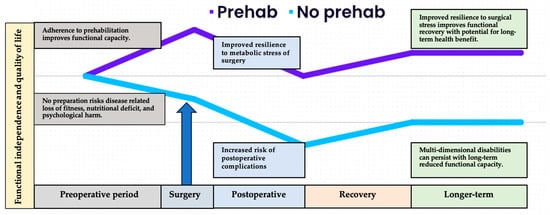

A patient’s preparedness for surgery’s physiological and psychological impact is not guaranteed. Historically, healthcare systems have prioritized the operation and disease itself. While historically healthcare prioritised the operation and disease, a compelling case supports postoperative outcomes being primarily influenced by patient resilience, i.e., their ability to counteract perioperative stressors [12]. This paradigm shift positions the surgical response as the primary ‘disease process,’ urging a recalibration of perioperative care to centre on optimising patient resilience at the time of contemplating surgery. Perioperative medicine now encompasses comprehensive support from initial suspicion of diagnosis to full recovery [13]. The interval between diagnosis and surgery presents an opportunity to tailor care for the changing patient demographic with intricate health requirements. Achieving this entails meticulous comorbidity management, arranging suitable enhanced care facilities, supporting health-enriching behaviours, and fostering informed discussions regarding the appropriateness of surgery, particularly when potential harm might outweigh the benefits. Regrettably, the prevalent care models rarely align with these risk-focused goals, often prioritizing siloed health system concerns such as treatment timeline, clinic availability, operating room capacity, and postoperative care resources. Reconfiguring surgical processes to facilitate patient-centric pathways, rooted in comprehensive risk assessment, can yield manifold advantages [14]. At this critical juncture, facing escalating cancer care demands and limited resources, adopting a business process re-engineering approach to perioperative medicine aligns with the widely-adopted “Quintuple Aim” of healthcare, i.e., enhancing care experiences, bolstering population health, reducing per capita healthcare, addressing clinician burnout, and advancing health equity [15,16,17].

This review has multiple objectives, specifically, raising awareness of the global public health concern, proposing a systematic framework for patient phenotyping and perioperative risk evaluation, and emphasizing the potential of personalized prehabilitation plans to mitigate risk based on international expert consensus guidelines. The manuscript, structured into two parts, initially focuses on established patient-level risk factors, broadly categorized under “functional capacity,” discussing their implications for perioperative outcomes and providing a concise overview of screening and assessment procedures. The subsequent section explores how prehabilitation can act as a risk-mitigating strategy, complementing interventions like managing comorbidities and facilitating smoking and alcohol cessation. It is crucial to note that while presented in a perioperative context, these actions hold promise for broader health benefits through longer-term behaviour change, making the perioperative period an ideal teachable moment for clinicians to positively impact multiple health domains.

3. Conclusions and Recommendations

The field of surgical cancer care has made remarkable gains in its mission to save lives. However, for the individuals in our care, the risk of postoperative complication looms large and can cause a significant and negative change to life trajectory for the entire family. We are facing a large, predicted increase in demand for cancer surgery and are further challenged by limited resources. It is imperative therefore that clinicians find scalable, effective, and economically viable methods to improve an individual’s postoperative outcome, improve the health of the population, and reduce per capita costs. The next challenge for healthcare providers is to embrace the opportunity provided by utilising the time between diagnosis and surgery to prepare the patient for the upcoming psychological and physiological stress. Comprehensive care should be offered within the entire cancer care continuum, from diagnosis to complete recovery.

This comprehensive review underscores the intricate relationship between multiple components of functional capacity and cancer care outcomes, particularly in the context of surgical interventions. It advocates for a refined risk evaluation approach that encompasses universal screening, followed by targeted assessment for patients at heightened risk. We have further highlighted the evidence-based foundational principles of prehabilitation. The detailed assessment can be used to guide individualised prehabilitation prescriptions to optimise patient condition prior to surgery and contribute to improved patient outcomes. Moreover, truly informed consent and meaningful shared decision-making discussions must be predicated upon accurate quantification of surgical risk.

Functional capacity is a widely recognised component of patient resilience, facilitating a proportionate response to the stress associated with cancer diagnosis and subsequent surgery. Traditional assessment approaches are empirically proven inaccurate predictors of risk [27]. This may in part be due to a narrow definition of functional capacity, overly reliant on assessment of purely physical ability. Evidence suggests that a true assessment of perioperative risk should encompass a broader definition, incorporating physical fitness, nutritional status, psychological health, and, where indicated, frailty and cognitive health.

Largely developed in the perioperative context, prehabilitation is now recognised as a key element of the wider cancer care continuum, empowering individuals to increase personal resilience in the face of challenges posed by preventative, restorative, supportive, and palliative phases.

To advance the field of prehabilitation research, several key recommendations emerge. Firstly, interventions should be tailored to individual patient needs and preferences and tested for effectiveness and impact. Secondly, the incorporation of implementation science methodologies is essential to bridge the gap between research and clinical practice, facilitating the integration of prehabilitation into routine patient care. Additionally, conducting health economics analyses can provide crucial insights into the cost-effectiveness and resource allocation aspects of prehabilitation programs, which can be instrumental in decision-making processes. Thirdly, a commitment to rigorous trial design, particularly randomised controlled trials, is fundamental to establishing the causal relationships and efficacy of prehabilitation interventions. Furthermore, the establishment of core outcome datasets will harmonise research efforts, enabling meaningful comparisons across studies and facilitate evidence synthesis.

Cancer surgery is a risky treatment, associated with high rates of mortality and morbidity, healthcare cost burden, and deleterious effects on quality of life for survivors. Addressing the associated risk has the potential to improve lives and save money. Addressing this risk in such a safety critical clinical environment provides both challenge and opportunity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and M.P.W.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B., M.A.W., S.J. and M.P.W.G.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, M.P.W.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.B. is funded by a National Institute for Health and Social Care Research Clinical Doctoral Fellowship (Funding award NIHR 302160).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sullivan, R.; Alatise, O.I.; Anderson, B.O.; Audisio, R.; Autier, P.; Aggarwal, A.; Sullivan, R.; Alatise, O.I.; Anderson, B.O.; Audisio, R.; et al. Global cancer surgery: Delivering safe, affordable, and timely cancer surgery. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 1193–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Surgical Outcomes Study Group TISOS. Global patient outcomes after elective surgery: Prospective cohort study in 27 low-, middle- and high-income countries. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resio, B.J.; Gonsalves, L.; Canavan, M.; Mueller, L.; Phillips, C.; Sathe, T.; Swett, K.; Boffa, D.J. Where the Other Half Dies: Analysis of Mortalities Occurring More Than 30 Days after Complex Cancer Surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 1278–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meara, J.G.; Greenberg, S.L. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery Global surgery 2030: Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery 2015, 157, 834–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearse, R.M.; Moreno, R.P.; Bauer, P.; Pelosi, P.; Metnitz, P.; Spies, C.; Vallet, B.; Vincent, J.L.; Hoeft, A.; Rhodes, A.; et al. Mortality after surgery in Europe: A 7 day cohort study. Lancet 2012, 380, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tevis, S.E.; Kennedy, G.D. Postoperative Complications: Looking Forward to a Safer Future. Clin. Colon. Rectal Surg. 2016, 29, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, M.G.; Michaels, A.D.; Mehaffey, J.H.; Guidry, C.A.; Turrentine, F.E.; Hedrick, T.L.; Friel, C.M. Risk Associated With Complications and Mortality after Urgent Surgery vs Elective and Emergency Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabenau, H.F.; Becher, R.D.; Gahbauer, E.A.; Leo-Summers, L.; Allore, H.G.; Gill, T.M. Functional Trajectories before and after Major Surgery in Older Adults. Ann. Surg. 2018, 268, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, V.A.; Hazuda, H.P.; Cornell, J.E.; Pederson, T.; Bradshaw, P.T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Page, C.P. Functional independence after major abdominal surgery in the elderly. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2004, 199, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, E.M.K.; Bell, M.; Cook, T.M.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Moonesinghe, S.R.; Central SNAP-1 Organisation; National Study Groups. Patient reported outcome of adult perioperative anaesthesia in the United Kingdom: A cross-sectional observational study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2016, 117, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, W.; Sanderson, W.; Scherbov, S. The coming acceleration of global population ageing. Nature 2008, 451, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Kooten, R.T.; Bahadoer, R.R.; Peeters, K.C.M.J.; Hoeksema, J.H.L.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Hartgrink, H.H.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; Wouters, M.W.J.M.; Tollenaar, R.A.E.M. Preoperative risk factors for major postoperative complications after complex gastrointestinal cancer surgery: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 3049–3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grocott, M.P.W.; Plumb, J.O.M.; Edwards, M.; Fecher-Jones, I.; Levett, D.Z.H. Re-designing the pathway to surgery: Better care and added value. Perioper. Med. 2017, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grocott, M.P. Pathway redesign: Putting patients ahead of professionals. Clin. Med. 2019, 19, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grocott, M.P.W.; Edwards, M.; Mythen, M.G.; Aronson, S. Peri-operative care pathways: Re-engineering care to achieve the ‘triple aim’. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, M.; Nolan, K. A Guide to Measuring the Triple Aim: Population Health, Experience of Care, and Per Capita Cost; IHI Innovation Series white paper; IHI—Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nundy, S.; Cooper, L.A.; Mate, K.S. The Quintuple Aim for Health Care Improvement. JAMA 2022, 327, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleisher, L.A.; Fleischmann, K.E.; Auerbach, A.D.; Barnason, S.A.; Beckman, J.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Davila-Roman, V.G.; Gerhard-Herman, M.D.; Holly, T.A.; Kane, G.C.; et al. 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, e77–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, C.M.; Ford, K.L.; Gonzalez, M.C.; Murnane, L.C.; Gillis, C.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Morrison, C.A.; Lobo, D.N. Nascent to novel methods to evaluate malnutrition and frailty in the surgical patient. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2023, 47, S54–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett, D.Z.H.; Grimmett, C. Psychological factors, prehabilitation and surgical outcomes: Evidence and future directions. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandini, M.; Pinotti, E.; Persico, I.; Picone, D.; Bellelli, G.; Gianotti, L. Systematic review and meta-analysis of frailty as a predictor of morbidity and mortality after major abdominal surgery. BJS Open 2017, 1, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.C.; Lee, I.M.; Weiderpass, E.; Campbell, P.T.; Sampson, J.N.; Kitahara, C.M.; Keadle, S.K.; Arem, H.; Berrington de Gonzalez, A.; Hartge, P.; et al. Association of Leisure-Time Physical Activity With Risk of 26 Types of Cancer in 1.44 Million Adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 2016, 176, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Colorectal Cancer; World Cancer Research Fund: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Older, P.; Hall, A.; Hader, R. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing as a Screening Test for Perioperative Management of Major Surgery in the Elderly. Chest 1999, 116, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argillander, T.E.; Heil, T.C.; Melis, R.J.F.; van Duijvendijk, P.; Klaase, J.M.; van Munster, B.C. Preoperative physical performance as predictor of postoperative outcomes in patients aged 65 and older scheduled for major abdominal cancer surgery: A systematic review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 48, 570–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.A.; Kong, J.C.; Ismail, H.; Riedel, B.; Heriot, A. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Objective Assessment of Physical Fitness in Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2018, 61, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijeysundera, D.N.; Pearse, R.M.; Shulman, M.A.; Abbott, T.E.F.; Torres, E.; Ambosta, A.; Croal, B.L.; Granton, J.T.; Thorpe, K.E.; Grocott, M.P.W.; et al. Assessment of functional capacity before major non-cardiac surgery: An international, prospective cohort study. Lancet 2018, 391, 2631–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, M.A.; Loughney, L.; Lythgoe, D.; Barben, C.P.; Adams, V.L.; Bimson, W.E.; Bimson, W.E.; Grocott, M.P.; Jack, S.; Kemp, G.J. The effect of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy on whole-body physical fitness and skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in vivo in locally advanced rectal cancer patients—An observational pilot study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, A.B.; Thomas, S.M.; Dittus, K.; Jones, L.W.; Lakoski, S.G. Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Breast Cancer Patients: A Call for Normative Values. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, E.; Cheek, F.; Chlan, L.; Gosselink, R.; Hart, N.; Herridge, M.S.; Hopkins, R.O.; Hough, C.L.; Kress, J.P.; Latronico, N.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis of Intensive Care Unit–acquired Weakness in Adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 190, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, R.C.F.; Turley, A.J.; Goodridge, V.; Danjoux, G.R. Does patient reported exercise capacity correlate with anaerobic threshold? Anaesthesia 2009, 64, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melon, C.C.; Eshtiaghi, P.; Luksun, W.J.; Wijeysundera, D.N. Validated Questionnaire vs Physicians’ Judgment to Estimate Preoperative Exercise Capacity. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Macmillan, Royal College of Anaesthetists, National Institute for Health and Social Care Research. Principles and Guidance for Prehabilitation within the Management and Support of People with Cancer In Partnership with Acknowledgements. November 2020. Macmillan, London, U.K. Available online: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/dfsmedia/1a6f23537f7f4519bb0cf14c45b2a629/13225-source/prehabilitation-for-people-with-cancer (accessed on 12 November 2023).

- Roland, M.; Guthrie, B. Quality and Outcomes Framework: What have we learnt? BMJ 2016, 354, i4060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyte, D.; Cockwell, P.; Lencioni, M.; Skrybant, M.; Hildebrand, M.V.; Price, G.; Squire, K.; Webb, S.; Brookes, O.; Fanning, H.; et al. Reflections on the national patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) programme: Where do we go from here? J. R. Soc. Med. 2016, 109, 441–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijeysundera, D.N.; Beattie, W.S.; Hillis, G.S.; Abbott, T.E.F.; Shulman, M.A.; Ackland, G.L.; Mazer, C.D.; Myles, P.S.; Pearse, R.M.; Cuthbertson, B.H.; et al. Integration of the Duke Activity Status Index into preoperative risk evaluation: A multicentre prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2020, 124, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurati Buse, G.A.; Mauermann, E.; Ionescu, D.; Szczeklik, W.; De Hert, S.; Filipovic, M.; Beck-Schimmer, B.; Spadaro, S.; Matute, P.; Bolliger, D.; et al. Risk assessment for major adverse cardiovascular events after noncardiac surgery using self-reported functional capacity: International prospective cohort study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2023, 130, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levett, D.Z.H.; Jack, S.; Swart, M.; Carlisle, J.; Wilson, J.; Snowden, C.; Riley, M.; Danjoux, G.; Ward, S.A.; Older, P.; et al. Perioperative cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET): Consensus clinical guidelines on indications, organization, conduct, and physiological interpretation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, E.; Egenvall, M.; Farahnak, P.; Bergenmar, M.; Nygren-Bonnier, M.; Franzén, E.; Rydwik, E. Better preoperative physical performance reduces the odds of complication severity and discharge to care facility after abdominal cancer resection in people over the age of 70—A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 44, 1760–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.H.-G.; Bolshinsky, V.; Ismail, H.; Ho, K.-M.; Heriot, A.; Riedel, B. Comparison of Duke Activity Status Index with cardiopulmonary exercise testing in cancer patients. J. Anesth. 2018, 32, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodseth, R.N.; Biccard, B.M.; Le Manach, Y.; Sessler, D.I.; Lurati Buse, G.A.; Thabane, L.; Schutt, R.C.; Bolliger, D.; Cagini, L.; Cardinale, D.; et al. The Prognostic Value of Pre-Operative and Post-Operative B-Type Natriuretic Peptides in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery: B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and N-Terminal Fragment of Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 170–180. [Google Scholar]

- Carli, F.; Silver, J.K.; Feldman, L.S.; McKee, A.; Gilman, S.; Gillis, C.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C.; Gamsa, A.; Stout, N.; Hirsch, B. Surgical Prehabilitation in Patients with Cancer: State-of-the-Science and Recommendations for Future Research from a Panel of Subject Matter Experts. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2017, 28, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Wischmeyer, P.E. Pre-operative nutrition and the elective surgical patient: Why, how and what? Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GlobalSurg Collaborative and NIHR Global Health Unit on Global Surgery. Impact of malnutrition on early outcomes after cancer surgery: An international, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob. Heal. 2023, 11, e341–e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Birdsell, L.; Macdonald, N.; Reiman, T.; Clandinin, M.T.; McCargar, L.J.; Murphy, R.; Ghosh, S.; Sawyer, M.B.; Baracos, V.E. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: Skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Haehling, S.; Anker, S.D. Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: Facts and numbers-update 2014. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014, 5, 261–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hübner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.G.; et al. ESPEN Guideline ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4745–4761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.N.; Kufeldt, J.; Kisser, U.; Hornung, H.M.; Hoffmann, J.; Andraschko, M.; Werner, J.; Rittler, P. Effects of malnutrition on complication rates, length of hospital stay, and revenue in elective surgical patients in the G-DRG-system. Nutrition 2016, 32, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozzetti, F.; Gianotti, L.; Braga, M.; Di Carlo, V.; Mariani, L. Postoperative complications in gastrointestinal cancer patients: The joint role of the nutritional status and the nutritional support. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 26, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einarsson, S.; Laurell, G.; Tiblom Ehrsson, Y. Mapping the frequency of malnutrition in patients with head and neck cancer using the GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 37, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Nguyen, T.H.; Liberman, A.S.; Carli, F. Nutrition Adequacy in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2015, 30, 414–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren, M.A.; Guaitoli, P.R.; Jansma, E.P.; de Vet, H.C. Nutrition screening tools: Does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 33, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A.; Wischmeyer, P.E.; Grocott, M.P.W. Prehabilitation and Nutritional Support to Improve Perioperative Outcomes. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2017, 7, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, M.; Kurmann, S.; Stanga, Z. Nutritional screening tools in daily clinical practice: The focus on cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2010, 18, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Senesse, P.; Gioulbasanis, I.; Antoun, S.; Bozzetti, F.; Deans, C.; Strasser, F.; Thoresen, L.; Jagoe, R.T.; Chasen, M.; et al. Diagnostic criteria for the classification of cancer-associated weight loss. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.; Capra, S.; Ferguson, M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 56, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prado, C.M.M.; Lieffers, J.R.; McCargar, L.J.; Reiman, T.; Sawyer, M.B.; Martin, L.; Baracos, V.E. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008, 9, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, M.L.; Bauer, J.; Gallagher, B.; Capra, S.; Christie, D.R.; Mason, B.R. Validation of a malnutrition screening tool for patients receiving radiotherapy. Australas. Radiol. 1999, 43, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Fleuret, C.; Pickard, J.M.; Mohammed, K.; Black, G.; Wedlake, L. Comparison of a novel, simple nutrition screening tool for adult oncology inpatients and the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) against the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA). Support. Care Cancer 2015, 23, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wischmeyer, P.E.; Carli, F.; Evans, D.C.; Guilbert, S.; Kozar, R.; Pryor, A.; Thiele, R.H.; Everett, S.; Grocott, M.; Gan, T.J.; et al. American Society for Enhanced Recovery and Perioperative Quality Initiative Joint Consensus Statement on Nutrition Screening and Therapy within a Surgical Enhanced Recovery Pathway. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1883–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinos Elia, P. The “MUST” Report Nutritional screening of adults: A multidisciplinary responsibility Development and use of the “Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool” (‘MUST’) for adults Chairman of MAG and Editor Advancing Clinical Nutrition. British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. November; 2003.

- Ottery, F.D. Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition 1996, 12, S15–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesari, A.; Noel, J.Y. Nutritional Assessment; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, L.; Bates, A.; Wootton, S.A.; Levett, D. The use of bioelectrical impedance analysis to predict post-operative complications in adult patients having surgery for cancer: A systematic review. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2914–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achamrah, N.; Colange, G.; Delay, J.; Rimbert, A.; Folope, V.; Petit, A.; Grigioni, S.; Déchelotte, P.; Coëffier, M. Comparison of body composition assessment by DXA and BIA according to the body mass index: A retrospective study on 3655 measures. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipek, L.Z.; Baptista, C.G.; Nascimento, R.F.V.; Taba, J.V.; Suzuki, M.O.; do Nascimento, F.S.; Martines, D.R.; Nii, F.; Iuamoto, L.R.; Carneiro-D’Albuquerque, L.A.; et al. The impact of properly diagnosed sarcopenia on postoperative outcomes after gastrointestinal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truijen, S.P.M.; Hayhoe, R.P.G.; Hooper, L.; Schoenmakers, I.; Forbes, A.; Welch, A.A. Predicting Malnutrition Risk with Data from Routinely Measured Clinical Biochemical Diagnostic Tests in Free-Living Older Populations. Nutrients 2021, 31, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehnert, A.; Hartung, T.J.; Friedrich, M.; Vehling, S.; Brähler, E.; Härter, M.; Keller, M.; Schulz, H.; Wegscheider, K.; Weis, J. One in two cancer patients is significantly distressed: Prevalence and indicators of distress. Psychooncology 2018, 27, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Chan, M.; Bhatti, H.; Halton, M.; Grassi, L.; Johansen, C.; Meader, N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: A meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, G.D.; Russ, T.C.; Stamatakis, E.; Kivimäki, M. Psychological distress in relation to site specific cancer mortality: Pooling of unpublished data from 16 prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2017, 356, j108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, K.N.; Cooper, D.; Armstrong, T.S.; King, A.L. The link between psychological distress and survival in solid tumor patients: A systematic review. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 3343–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, H.Y.V.; Abrishami, A.; Peng, P.W.H.; Wong, J.; Chung, F. Predictors of Postoperative Pain and Analgesic Consumption. Anesthesiology 2009, 111, 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavros, M.N.; Athanasiou, S.; Gkegkes, I.D.; Polyzos, K.A.; Peppas, G.; Falagas, M.E. Do Psychological Variables Affect Early Surgical Recovery? PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, N.; Dwyer, M.; Stankovich, J.; Peterson, G.; Greenfield, D.; Si, L.; Kinsman, L. Hospital length of stay variation and comorbidity of mental illness: A retrospective study of five common chronic medical conditions. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C.; Haviland, J.; Winter, J.; Grimmett, C.; Chivers Seymour, K.; Batehup, L.; Calman, L.; Corner, J.; Din, A.; Fenlon, D.; et al. Pre-Surgery Depression and Confidence to Manage Problems Predict Recovery Trajectories of Health and Wellbeing in the First Two Years following Colorectal Cancer: Results from the CREW Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nipp, R.D.; El-Jawahri, A.; Fishbein, J.N.; Eusebio, J.; Stagl, J.M.; Gallagher, E.R.; Park, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Pirl, W.F.; Greer, J.A.; et al. The relationship between coping strategies, quality of life, and mood in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer 2016, 122, 2110–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberger, P.H.; Jokl, P.; Ickovics, J. Psychosocial factors and surgical outcomes: An evidence-based literature review. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2006, 14, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K.; Robles, T.F.; Heffner, K.L.; Loving, T.J.; Glaser, R. Psycho-oncology and cancer: Psychoneuroimmunology and cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2002, 13, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, D.; Giese-Davis, J. Depression and cancer: Mechanisms and disease progression. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, B.F.; Hasin, D.S.; Chou, S.P.; Stinson, F.S.; Dawson, D.A. Nicotine dependence and psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2004, 61, 1107–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puddephatt, J.; Irizar, P.; Jones, A.; Gage, S.H.; Goodwin, L. Associations of common mental disorder with alcohol use in the adult general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction 2022, 117, 1543–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, T.; Kay-Lambkin, F.; Pursey, K.; Skinner, J.; Dayas, C. Food addiction and associations with mental health symptoms: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 31, 544–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bultz, B.D.; Carlson, L.E. Emotional distress: The sixth vital sign—Future directions in cancer care. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.; Watson, M.; Dunn, J. The IPOS new International Standard of Quality Cancer Care: Integrating the psychosocial domain into routine care. Psychooncology 2011, 20, 677–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirl, W.F.; Fann, J.R.; Greer, J.A.; Braun, I.; Deshields, T.; Fulcher, C.; Harvey, E.; Holland, J.; Kennedy, V.; Lazenby, M.; et al. Recommendations for the implementation of distress screening programs in cancer centers: Report from the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (APOS), Association of Oncology Social Work (AOSW), and Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) joint task force. Cancer 2014, 120, 2946–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.L.; DeRubeis, R.J.; Berman, B.S.; Gruman, J.; Champion, V.L.; Massie, M.J.; Holland, J.C.; Partridge, A.H.; Bak, K.; Somerfield, M.R.; et al. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.E.; Waller, A.; Groff, S.L.; Zhong, L.; Bultz, B.D. Online screening for distress, the 6th vital sign, in newly diagnosed oncology outpatients: Randomised controlled trial of computerised vs personalised triage. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimmett, C.; Heneka, N.; Chambers, S. Psychological Interventions Prior to Cancer Surgery: A Review of Reviews. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2022, 12, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordova, M.J.; Riba, M.B.; Spiegel, D. Post-traumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med. Care 2003, 41, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J. Pooled Results From 38 Analyses of the Accuracy of Distress Thermometer and Other Ultra-Short Methods of Detecting Cancer-Related Mood Disorders. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 4670–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, B.T.; Kathol, R.G.; Noyes, R.; Wald, T.G.; Clamon, G.H. Screening for depression and anxiety in cancer patients using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 1993, 15, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J. Short Screening Tools for Cancer-Related Distress: A Review and Diagnostic Validity Meta-Analysis. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2010, 8, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B.; Unützer, J.; Callahan, C.M.; Perkins, A.J.; Kroenke, K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med. Care 2004, 42, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Butow, P.; Price, M.A.; Shaw, J.M.; Turner, J.; Clayton, J.M.; Grimison, P.; Rankin, N.; Kirsten, L. Clinical pathway for the screening, assessment and management of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: Australian guidelines. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schenker, R.A.; Schenker, M.; Stovicek, P.O.; Mazilu, L.; Negru Șerban, M.; Burov, G.; Ciurea, M.E. Comprehensive preoperative psychological assessment of breast cancer patients. Psychol. Health Med. 2023, 28, 359–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.W.; Löwe, B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L. The PHQ-9: A New Depression Diagnostic and Severity Measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, S.D.; Steginga, S.K.; Dunn, J. The tiered model of psychosocial intervention in cancer: A community based approach. Psychooncology 2006, 15, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morley, J.E.; Vellas, B.; Abellan van Kan, G.; Anker, S.D.; Bauer, J.M.; Bernabei, R.; Cesari, M.; Chumlea, W.C.; Doehner, W.; Evans, J.; et al. Frailty Consensus: A Call to Action. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Kowal, P.; Hoogendijk, E.O. Frailty measurement in research and clinical practice: A review. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, N.M.; Qadan, M.; Silver, J.K. Implications of Preoperative Patient Frailty on Stratified Postoperative Mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, D.A.; Liu, J.H.; O’connell, J.B.; Maggard, M.A.; Ko, C.Y. Elderly Patients in Surgical Workloads: A Population-Based Analysis. Am. Surg. 2003, 69, 961–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.F.; Budiansky, D.; Sharif, F.; McIsaac, D.I. The Association of Frailty with Outcomes after Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4690–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.-S.; Watts, J.N.; Peel, N.M.; Hubbard, R.E. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinn, R.; Agung, Y.; Grudzinski, A.L.; Talarico, R.; Hallet, J.; McIsaac, D.I. Attributable perioperative cost of frailty after major, elective non-cardiac surgery: A population-based cohort study. Anesthesiology 2023, 139, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinall, M.C.; Arya, S.; Youk, A.; Varley, P.; Shah, R.; Massarweh, N.N.; Shireman, P.K.; Johanning, J.M.; Brown, A.J.; Christie, N.A.; et al. Association of Preoperative Patient Frailty and Operative Stress With Postoperative Mortality. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, e194620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centre for Perioperative Care. Preoperative Assessment and Optimisation for Adult Surgery including Consideration of COVID-19 and Its Implications; Centre for Perioperative Care: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sturgess, J.; Clapp, J.T.; Fleisher, L.A. Shared decision-making in peri-operative medicine: A narrative review. Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overview|Shared Decision Making|Guidance|NICE. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-guidelines/shared-decision-making (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolfson, D.B.; Majumdar, S.R.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Tahir, A.; Rockwood, K. Validity and reliability of the Edmonton Frail Scale. Age Ageing 2006, 35, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Miller, D.K. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2012, 16, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, G.; Gardner, M.; Tsiachristas, A.; Langhorne, P.; Burke, O.; Harwood, R.H.; Conroy, S.P.; Kircher, T.; Somme, D.; Saltvedt, I.; et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD006211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eamer, G.; Saravana-Bawan, B.; van der Westhuizen, B.; Chambers, T.; Ohinmaa, A.; Khadaroo, R.G. Economic evaluations of comprehensive geriatric assessment in surgical patients: A systematic review. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 218, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Buckley, R.F.; van der Flier, W.M.; Han, Y.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Rabin, L.; Rentz, D.M.; Rodriguez-Gomez, O.; Saykin, A.J.; et al. The characterisation of subjective cognitive decline. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Beaumont, H.; Ferguson, D.; Yadegarfar, M.; Stubbs, B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: Meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014, 130, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jongsiriyanyong, S.; Limpawattana, P. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Clinical Practice: A Review Article. Am. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. Other Dement. 2018, 33, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, S.; Reisberg, B.; Zaudig, M.; Petersen, R.C.; Ritchie, K.; Broich, K.; Belleville, S.; Brodaty, H.; Bennett, D.; Chertkow, H.; et al. Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet 2006, 367, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerstens, C.; Wildiers, H.P.M.W.; Schroyen, G.; Almela, M.; Mark, R.E.; Lambrecht, M.; Deprez, S.; Sleurs, C. A Systematic Review on the Potential Acceleration of Neurocognitive Aging in Older Cancer Survivors. Cancers 2023, 15, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Au, E.; Saripella, A.; Kapoor, P.; Yan, E.; Wong, J.; Tang-Wai, D.F.; Gold, D.; Riazi, S.; Suen, C.; et al. Postoperative outcomes in older surgical patients with preoperative cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Anesth. 2022, 80, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.; Lunn, A.D.; Smith, A.D.; Lehmann, D.J.; Dorrington, K.L. Cognitive decline in the elderly after surgery and anaesthesia: Results from the Oxford Project to Investigate Memory and Ageing (OPTIMA) cohort. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanna-Gabrielli, E.; Schenning, K.J.; Eriksson, L.I.; Browndyke, J.N.; Wright, C.B.; Evered, L.; Scott, D.A.; Wang, N.Y.; Brown, C.H., 4th; Oh, E.; et al. State of the clinical science of perioperative brain health: Report from the American Society of Anesthesiologists Brain Health Initiative Summit 2018. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, W.B.; Rosenthal, R.A.; Merkow, R.P.; Ko, C.Y.; Esnaola, N.F. Optimal Preoperative Assessment of the Geriatric Surgical Patient: A Best Practices Guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2012, 215, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasreddine, Z.S.; Phillips, N.A.; Bédirian, V.; Charbonneau, S.; Whitehead, V.; Collin, I.; Cummings, J.L.; Chertkow, H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool For Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005, 53, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borson, S.; Scanlan, J.; Brush, M.; Vitaliano, P.; Dokmak, A. The Mini-Cog: A cognitive ?vital signs? measure for dementia screening in multi-lingual elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2000, 15, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, S.K.; van Dyck, C.H.; Alessi, C.A.; Balkin, S.; Siegal, A.P.; Horwitz, R.I. Clarifying confusion: The confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann. Intern. Med. 1990, 113, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipps, C.M.; Hodges, J.R. Cognitive assessment for clinicians. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76 (Suppl. S1), i22–i30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mioshi, E.; Dawson, K.; Mitchell, J.; Arnold, R.; Hodges, J.R. The Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination Revised (ACE-R): A brief cognitive test battery for dementia screening. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2006, 21, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, A.; West, M.A.; Jack, S. Framework for prehabilitation services. Br. J. Surg. 2020, 107, e11–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Varadhan, K.K.; Neal, K.R.; Dejong, C.H.C.; Fearon, K.C.H.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for patients undergoing major elective open colorectal surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 29, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet-Dion, G.; Awasthi, R.; Loiselle, S.È.; Minnella, E.M.; Agnihotram, R.V.; Bergdahl, A.; Carli, F.; Scheede-Bergdahl, C. Evaluation of supervised multimodal prehabilitation programme in cancer patients undergoing colorectal resection: A randomized control trial. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterland, J.L.; McCourt, O.; Edbrooke, L.; Granger, C.L.; Ismail, H.; Riedel, B.; Denehy, L. Efficacy of Prehabilitation Including Exercise on Postoperative Outcomes Following Abdominal Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Surg. 2021, 8, 628848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, S.M.; Nucci, L.B.; da Silva, M.M.; Campacci, T.C. Pulmonary function and physical performance outcomes with preoperative physical therapy in upper abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2013, 27, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barberan-Garcia, A.; Ubré, M.; Roca, J.; Lacy, A.; Burgos, F. Personalised prehabilitation in high-risk patients undergoing elective major abdominal surgery: A randomized blinded controlled trial. Ann. Surg. 2018, 267, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, M.A.; Loughney, L.; Lythgoe, D.; Barben, C.P.; Sripadam, R.; Kemp, G.J.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Jack, S. Effect of prehabilitation on objectively measured physical fitness after neoadjuvant treatment in preoperative rectal cancer patients: A blinded interventional pilot study. Br. J. Anaesth. 2015, 114, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, M.A.; Astin, R.; Moyses, H.E.; Cave, J.; White, D.; Levett, D.Z.H.; Bates, A.; Brown, G.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Jack, S. Exercise prehabilitation may lead to augmented tumor regression following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2019, 58, 588–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschke, R.K.; Lampit, A.; Schenk, A.; Javelle, F.; Steindorf, K.; Diel, P.; Bloch, W.; Zimmer, P. Impact of Physical Exercise on Growth and Progression of Cancer in Rodents—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treanor, C.; Kyaw, T.; Donnelly, M. An international review and meta-analysis of prehabilitation compared to usual care for cancer patients. J. Cancer Surviv. 2018, 12, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraux, E.; Caty, G.; Reychler, G. Effects of preoperative combined aerobic and resistance exercise training in cancer patients undergoing tumour resection surgery: A systematic review of randomised trials. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 27, 584–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, C.; Buhler, K.; Bresee, L.; Carli, F.; Gramlich, L.; Culos-Reed, N.; Sajobi, T.T.; Fenton, T.R. Effects of Nutritional Prehabilitation, With and Without Exercise, on Outcomes of Patients Who Undergo Colorectal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijazi, Y.; Gondal, U.; Aziz, O. A systematic review of prehabilitation programs in abdominal cancer surgery. Int. J. Surg. 2017, 39, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.E.; Hayes, L.D.; Keegan, T.J.; Subar, D.A.; Gaffney, C.J. The Impact of Prehabilitation on Patient Outcomes in Hepatobiliary, Colorectal, and Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Surgery. Ann. Surg. 2021, 274, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, G.; Tahir, M.R.; Bongers, B.C.; Kallen, V.L.; Slooter, G.D.; van Meeteren, N.L. Prehabilitation before major intra-abdominal cancer surgery: A systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2019, 36, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheede-Bergdahl, C.; Minnella, E.M.; Carli, F. Multi-modal prehabilitation: Addressing the why, when, what, how, who and where next? Anaesthesia 2019, 74, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.F.; van Rooijen, S.J.; Grimmett, C.; West, M.A.; Campbell, A.M.; Awasthi, R.; Slooter, G.D.; Grocott, M.P.; Carli, F.; Jack, S. From Theory to Practice: An International Approach to Establishing Prehabilitation Programmes. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2022, 12, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, C.; Colombo, R. Making the Business Case for Implementing Prehabilitation Services. Available online: https://www.accc-cancer.org/docs/documents/management-operations/business-cases/prehab-tool.pdf?sfvrsn=bbfb2fa4_2 (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Santa Mina, D.; van Rooijen, S.J.; Minnella, E.M.; Alibhai, S.M.H.; Brahmbhatt, P.; Dalton, S.O.; Gillis, C.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Howell, D.; Randall, I.M.; et al. Multiphasic Prehabilitation Across the Cancer Continuum: A Narrative Review and Conceptual Framework. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 598425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, J.K.; Santa Mina, D.; Bates, A.; Gillis, C.; Silver, E.M.; Hunter, T.L.; Jack, S. Physical and Psychological Health Behavior Changes During the COVID-19 Pandemic that May Inform Surgical Prehabilitation: A Narrative Review. Curr. Anesthesiol. Rep. 2022, 12, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, M.; Weston, K.L.; Prentis, J.M.; Snowden, C.P. High-intensity interval training (HIT) for effective and time-efficient pre-surgical exercise interventions. Perioper. Med. 2016, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kidd, T.; Mold, F.; Jones, C.; Ream, E.; Grosvenor, W.; Sund-Levander, M.; Tingström, P.; Carey, N. What are the most effective interventions to improve physical performance in pre-frail and frail adults? A systematic review of randomised control trials. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weimann, A.; Braga, M.; Carli, F.; Higashiguchi, T.; Hübner, M.; Klek, S.; Laviano, A.; Ljungqvist, O.; Lobo, D.N.; Martindale, R.; et al. ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 623–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawood, A.L.; Elia, M.; Stratton, R.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of high protein oral nutritional supplements. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimopoulou, I.; Pasquali, S.; Howard, R.; Desai, A.; Gourevitch, D.; Tolosa, I.; Tolosa, I.; Vohra, R. Psychological Prehabilitation Before Cancer Surgery: A Systematic Review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 4117–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecher-Jones, I.; Grimmett, C.; Carter, F.J.; Conway, D.H.; Levett, D.Z.H.; Moore, J.A. Surgery school—Who, what, when, and how: Results of a national survey of multidisciplinary teams delivering group preoperative education. Perioper. Med. 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).