Abstract

Lung cancer patients suffer from numerous symptoms that impact their quality of life. This study aims to identify the symptom burden on quality of life in lung cancer patients. This survey used a structured questionnaire to collect data from 8 March 2021 to 12 May 2021. Patient demographic information was collected. The data on symptom burden and quality of life (QOL) of patients were obtained from the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-LC13. The stepwise multiple regression analysis was used to estimate lung cancer-related symptom burden in relation to quality of life. The study included 159 patients with lung cancer who completed the questionnaire. The mean age of the patients was 63.12 ± 11.4 years, and 64.8% of them were female. The Global Quality of Life score of the QLQ-C30 was 67.87 ± 22.24, and the top five lung cancer-related symptoms were insomnia, dyspnea, and fatigue from the QLQ-C30, and coughing and dyspnea from the QLQ-LC13. The multiple regression analysis showed that appetite loss was the most frequently associated factor for global QOL (β = −0.32; adjusted R2: 27%) and cognitive function (β = −0.15; adjusted R2: 11%), while fatigue was associated with role function (β = −0.35; adjusted R2: 43%), emotional function (β = −0.26; adjusted R2: 9%), and social function (β = −0.26; adjusted R2: 27%). Dyspnea was associated with physical function (β = −0.45; adjusted R2: 42%). Appetite loss, fatigue, and dyspnea were the main reasons causing symptom burdens on quality of life for lung cancer patients. Decreasing these symptoms can improve the quality of life and survival for patients with lung cancer.

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of death in the world [1,2]. Patients with lung cancer experience multiple symptoms that are highly disruptive to their physical and emotional functioning and quality of life [3,4]. These symptom clusters are caused by lung cancer itself and the side effects of treatments such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and interfere with patients’ daily life functions and affect their quality of life [5].

Confirming the phenomenon of symptom clusters among lung cancer patients may provide physicians with the ability to identify disease conditions during the treatment process [6,7] and provide a reasonable treatment goal to reduce the effect of symptoms while increasing the functioning and quality of life (QOL) for patients [8]. Furthermore, improving lung cancer-related symptoms and quality of life may affect survival [9,10,11]. The literature has found that fatigue, loss of appetite, cough, pain, and shortness of breath were significant predictors of the quality of life in patients with lung cancer [12,13,14,15,16].

To identify the symptom burden during the treatment process in patients with lung cancer, healthcare providers should encourage using multidimensional strategies to manage the main symptoms and improve quality of life [15,16]. Previous studies have only focused on the significant symptom predictors of the quality of life. Some studies found that overall symptom severity was the main negative predictor of quality of life [17,18]. Few studies have examined the explained amount of variance in single symptoms for quality of life among lung cancer patients to identify the main symptom that affected QOL.

Given the significance of treatment strategies and the limited outcomes observed in prior research, we pursued research to define and assess the main burden of lung cancer-related symptoms and quality of life in lung cancer patients. These findings may help identify the symptom burden conditions for physicians to develop effective healthcare interventions to improve healthcare quality and enhance the quality of life and survival of lung cancer patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

Patients were recruited at a thoracic oncology department at a medical center. The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with lung cancer, aged above 20 years, and fully conscious. Patients were introduced to the interviewer by a physician. After the study was explained and informed consent was obtained, a one-on-one, face-to-face survey was conducted from 8 March 2021 to 12 May 2021. A total of 159 completed questionnaires were collected.

2.2. Patient Demographics and Database

The questionnaire covered the following sections: patient demographic information (i.e., gender, age, marital status, education level, living with family, diagnosis year, smoking status, family history, secondhand smoking status, disease stage, income level, occupational status, and treatment history, including nil, chemotherapy [CT] or radiotherapy [RT], or CT and RT). The data on symptom burden and quality of life (QOL) were obtained from the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-LC13, which have good validity and reliability [19].

2.3. EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire C-30 (EORTC-QLQ-C30)

The EORTC QLQ-C30, which comprises 30 items, is the most popular instrument applied to measure quality of life for all kinds of cancers [20]. It contains six primary QOL domains: global health status scale (2 items), physical function (5 items), role function (2 items), emotional function (2 items), cognitive function (2 items), and social function (2 items); eight cancer symptoms (i.e., fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, and diarrhea); and a financial difficulties scale. The subjects responded to each statement on a scale of 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘very much’). The global health status scale ranged from 0 (‘very poor’) to 7 (‘excellent’). The scores were calculated by first computing the raw scores as the means of item responses. The raw scores were then converted into scaled scores ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores for the scales indicate a better QOL. A higher average score equates to a greater symptom burden [21].

2.4. EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire in Lung Cancer (EORTC-QLQ-LC13)

The 13 items that the QLQ-LC13 questionnaire measures include 10 lung cancer-related symptoms and treatment-related adverse effects (i.e., dyspnea, coughing, hemoptysis, sore mouth, dysphagia, peripheral neuropathy, alopecia, chest pain, pain in the arm or shoulder, pain in other parts). The QLQ-LC13 items use a 1-to-4 verbal response scale. The scores were calculated by first finding the means of item responses to obtain the raw scores, which were then converted into scaled scores ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores for the scales indicate a greater burden for symptom scales [22].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented for sample characteristics. The frequency and percentage or mean and standard deviation were computed for categorical and continuous variables. Correlation analyses were performed to examine the associations between lung cancer-related symptoms and quality of life variables. The stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify the factors influencing the six primary QOL domains. The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used as an indicator for multicollinearity effects. In our study, the level of VIF of all variables was less than 4, which was the acceptable level [3,7,23]. The standardized betas (β) and explained variation (Adjusted R2 and R2 change) of significant variables were used to estimate the effects of lung cancer-related symptoms for QOL. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 25.

3. Results

Of the 159 patients, the mean age was 63.12 ± 11.4 years, and 64.8% of all patients were female. The majority of the patients were married (76.7%), had completed high school or higher education (61.6%), lived with family (85.5%), had been diagnosed within five years (68.6%), had never smoked (78.0%), had no family history of smoking (73.6%), had no secondhand smoke status (73.0%), had > US$645 monthly income level (59.8%), and were unemployed (79.2%). Most had been diagnosed with stage IV (68.5%) lung cancer and were receiving chemotherapy or radiotherapy (42.1%), with a proportion undergoing second-line treatment (34.6%) as their treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (n = 159).

Table 2 shows the quality of life and lung cancer-related symptoms data collected from the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-LC13. The Global QOL score was 67.87 ± 22.24. The mean ± SD of the five function scores was 82.14 ± 20.28 for physical function (PF), 82.29 ± 27.98 for role function (RF), 86.69 ± 21.26 for emotional function (EF), 84.28 ± 21.24 for cognitive function (CF), and 80.29 ± 27.55 for social function (SF). The top five highest scores of lung cancer-related symptoms were insomnia (32.08 ± 36.72), dyspnea (24.53 ± 31.48), and fatigue (23.27 ± 27.04) among the nine symptoms from the QLQ-C30 and coughing (23.06 ± 29.04) and dyspnea (19.92 ± 27.28) among the ten symptoms from the QLQ-LC13.

Table 2.

Patients’ Quality of Life Score and Lung Cancer Symptom Scales (n = 159).

Table 3 was the result of Pearson correlations between symptoms and quality of life variables. The global QOL had negative correlations with fatigue (r = −0.49, p < 0.01), nausea and vomiting (r = −0.029, p < 0.01), pain (r = −0.36, p <0.01), dyspnea (r = −0.34, p <0.01), appetite loss (r = −0.52, p < 0.01), constipation (r = −0.28, p < 0.01), diarrhea (r = −0.25, p < 0.01), financial difficulties (r = −0.35, p < 0.01), dyspnea (r = −0.44, p < 0.01), alopecia (r = −0.17, p < 0.05), chest pain (r = −0.37, p < 0.01), pain in the arm or shoulder (r = −0.17, p < 0.05), and pain in other body parts (r = −0.20, p < 0.05). In the other five function scores, the significant symptom variables were shown to be negatively correlated, and the symptoms with the highest r were fatigue, pain, dyspnea, appetite loss, dyspnea, and chest pain.

Table 3.

The relationship between symptom burden and quality of life (n = 159).

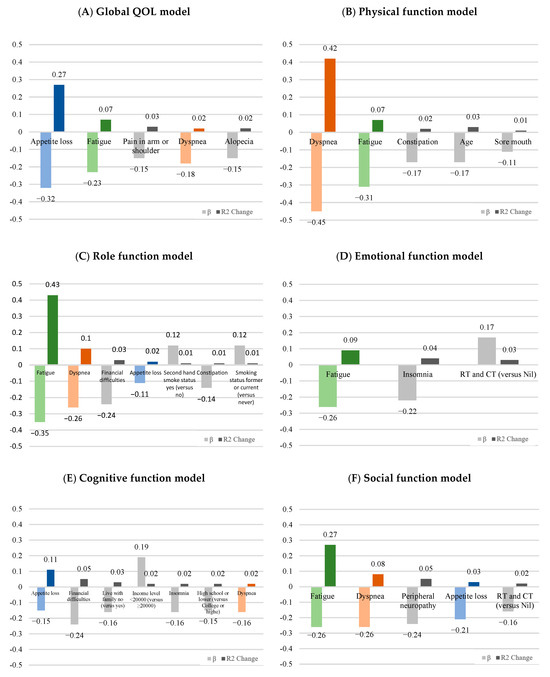

In Table 4, the stepwise multiple regression analysis revealed that the predictors of global QOL were appetite loss, fatigue, pain in arm or shoulder, dyspnea, and alopecia, which accounted for 40% of the variance and the β from −0.15 to −0.32 (F = 22.02, p < 0.001). Appetite loss was the most affected factor for 27% of the variance. The variables of dyspnea, fatigue, constipation, age, and sore mouth were the predictors of physical function, which accounted for 54% of the variance and the β from −0.11 to −0.45 (F = 37.82, p < 0.001). The predictors of role function were fatigue, dyspnea, financial difficulties, appetite loss, and constipation, which accounted for 60% of the variance and the β from −0.12 to −0.35 (F = 35.38, p < 0.001). Furthermore, smoking status (β = 8.08) and secondhand smoke status (β = 7.47) were positively associated with role functioning. The significant factors of emotional function were fatigue, insomnia, and RT and CT treatment, which accounted for just 13% of the variance and the β from −0.17 to −0.26 (F = 9.03, p < 0.001). The variables of appetite loss, financial difficulties, life with family, income level, insomnia, education level, and dyspnea were significant with the cognitive function, which accounted for 23% of the variance and the β from −0.15 to −0.24 (F = 7.90, p < 0.001). The predictors of social function were fatigue, dyspnea, peripheral neuropathy, appetite loss, and RT and CT treatment, which accounted for 45% of the variance and the β from −0.16 to −0.26 (F = 26.40, p < 0.001). In these five function models, the symptoms of dyspnea, fatigue, fatigue, appetite loss, and fatigue had accounted for the higher variance (R2 change) individually (Figure 1).

Table 4.

Results for multivariable regression analyses for quality of life (n = 159).

Figure 1.

The standardized betas (β) and explained variation (R2 change) of significant symptoms for (A) global health, (B) physical function, (C) role function, (D) emotional function, (E) cognitive function, and (F) social function according to the result of the stepwise multiple regression analysis. Appetite loss (blue), fatigue (green), and dyspnea (orange) were the main symptom burdens in lung cancer patients.

4. Discussion

The findings of our study demonstrate that lung cancer patients experience a lower perception of their global health status and social functioning compared to other aspects of functioning. The burden of symptoms reported by lung cancer patients, as assessed by the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13 questionnaires, primarily included insomnia, fatigue, coughing, and dyspnea. In our regression model, these lung cancer-related symptoms and factors accounted for significant variations of 40%, 54%, 60%, 13%, 23%, and 45% in global quality of life, physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning, and social functioning, respectively. Of particular importance among these predicted factors, appetite loss, dyspnea, and fatigue were found to exert the strongest impact on the quality of life experienced by lung cancer patients. Accordingly, prioritizing these symptoms is essential to enhance overall wellbeing and quality of life for individuals with lung cancer. These findings highlight the need for targeted interventions and personalized care strategies that address the specific challenges posed by these symptoms, ultimately leading to improved outcomes and enhanced quality of life for lung cancer patients.

In our study, the global quality of life (QOL) score was the lowest (mean ± SD: 67.87 ± 22.24) compared to the six domains of the QLQ-C30 questionnaire. However, compared to previous studies [19,24,25], our study was slightly higher than the others. These variations may be attributed to differences in disease stage among the sample populations, as well as improvements or deteriorations in functioning and QOL depending on the treatment type and follow-up duration. This highlights the need for greater emphasis on enhancing the quality of life for patients undergoing treatment. Therefore, it is worth exploring the symptoms that significantly impact the QOL of lung cancer patients.

Consistent with prior literature [4,12,15,24,26,27,28], our study observed higher scores for lung cancer-related symptoms, including insomnia, dyspnea, fatigue, and coughing, as measured by the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13 questionnaires (Table 2). These symptoms were found to have a moderate to significantly low impact on various aspects of quality of life (i.e., global GOL, PF, RF, EF, CF, and SF, Table 3). Our study further found a higher explained variation of lung cancer-related symptoms in the regression model (Table 4). According to the adjusted R square, the highest-burden symptoms in patients with lung cancer were appetite loss for global QOL (27%) and cognitive function (11%); fatigue for role function (43%), emotional function (9%) and social function (27%); and dyspnea (42%) for physical function. These results provided a very important reference value for physicians in their treatment strategy of lung cancer patients. Appetite loss, dyspnea, and fatigue were the main burden symptoms. If these three symptoms can be improved, it will benefit patients’ quality of life and even affect their future survival rates. Various intervention programs, such as nutritional counseling, nutritional supplements, breathing exercises, and physical activity programs have been shown to positively influence these symptoms and quality of life in the treatment of lung cancer patients [28,29,30,31]. As previous studies have pointed out, patients with lung cancer suffer multiple symptoms caused by disease and treatment. The treatment-related symptoms increased over time, but disease-related symptoms tended to be palliated after treatment initiation [24]. When treating lung cancer patients, physicians can consider the symptom burden in treatment time to improve the patient’s QOL.

The patients undergoing active radiotherapy and chemotherapy for treatment (compared with no treatment) were better in emotional function (t = 2.23, p = 0.022) and worse in social function (t = −2.61, p = 0.010). This finding was similar to that of previous studies [24], and this may be because the patients felt reassured from receiving treatment and, thus, felt good for emotional function, but because of the side effects of the treatment, their social functioning was affected.

Previous studies have indicated the significant impact of lung cancer on patients’ health-related quality of life. Specifically, stage IV disease and line of treatment were found to substantially deteriorate utility [32]. Our analysis utilized a mixed sample approach, which underscores the complexity of these relationships. Future research should focus on examining how different subgroups of treatment lines affect symptoms and QOL. Investigating these relationships in greater detail could provide valuable insights into how various stages of treatment influence patient wellbeing and symptom management, potentially leading to more tailored and effective interventions.

A notable strength of our study is our focus on identifying the primary burden symptoms in lung cancer patients, which provides valuable insights into their specific challenges and experiences. We found that appetite loss affected global QOL and cognitive function, while fatigue impacted role, emotional, and social function. Dyspnea was a major burden for physical function, as indicated by the R square in our regression model. These findings provide healthcare professionals with critical, actionable insights that can guide targeted interventions to improve patient outcomes. Unlike previous studies that have primarily reported associations between symptoms and lung cancer, our research offers a more nuanced understanding of how these symptoms affect various dimensions of patient wellbeing.

Despite the significant findings in this study, there are some limitations in our study. Firstly, the data for our study were derived from a medical center in Taiwan, and the results cannot be generalized to all patients with lung cancer. Additionally, the population is predominantly female, nonsmoking, and with high education and income levels, which may affect the applicability of our findings to other demographic groups [33]. Secondly, the samples were from patients who agreed to accept the research, so the quality of life of the patients was overestimated. Finally, the acceptance period was three months, from 8 March 2021 to 12 May 2021, and was later suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A larger scale of data collection is required to conduct further analyses. We suggest that future research with larger and more diverse samples is necessary to validate and extend our findings.

5. Conclusions

Data were collected from lung cancer patients using the QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-LC13 to assess symptom burdens and quality of life. Our findings highlight key areas of symptom burden that affect patients significantly. Future research should focus on developing targeted interventions to address these symptom burdens, particularly appetite loss, fatigue, and dyspnea. Investigating how to effectively manage these symptoms could lead to improved quality of life and potentially enhance survival rates for lung cancer patients. Additional studies should explore the long-term effects of symptom management on overall outcomes in lung cancer patients and assess the effectiveness of various treatment strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-J.C. and H.-C.L.; Data curation, H.-C.L.; Formal analysis, L.-J.C.; Funding acquisition, H.-C.L.; Investigation, Y.-Y.L. and H.-C.L.; Methodology, L.-J.C. and H.-C.L.; Project administration, H.-C.L.; Resources, H.-C.L.; Validation, H.-C.L.; Writing—original draft, L.-J.C.; Writing—review & editing, L.-J.C. and H.-C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (MOST 108-2410-H-010-009-MY3).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the TPEVGH Institutional Review Board (IRB-TPEVGH No.: 2020-12-001AC#1), 23 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this article are not readily available because these data are part of an ongoing study, and participants did not consent to their information being publicly shared.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Michael Burton, who provided professional editing of the Asia University manuscript, and Pei-Tseng Kung for conducting a thorough review as a statistician.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer Fact Sheet. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/ (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Morrison, E.J.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.A.; Yang, P.; Patten, C.A.; Ruddy, K.J.; Clark, M.M. Emotional Problems, Quality of Life, and Symptom Burden in Patients With Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2017, 18, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.; Ryu, E. Effects of symptom clusters and depression on the quality of life in patients with advanced lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2018, 27, e12508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, S.; Taylor-Stokes, G.; Roughley, A. Symptom burden and quality of life in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients in France and Germany. Lung Cancer 2013, 81, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhou, J. Pain, fatigue, disturbed sleep and distress comprised a symptom cluster that related to quality of life and functional status of lung cancer surgery patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1281–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsevick, A.M. The elusive concept of the symptom cluster. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2007, 34, 971–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.Y.; Wu, L.M.; Chen, K.P. Determinants of Quality of Life in Lung Cancer Patients. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2018, 50, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingura, A.; Taye, M.; Musoro, J.; Ringash, J.; Pe, M.; Coens, C.; Martinelli, F.; Tu, D.; Basch, E.; Brandberg, Y.; et al. Clustering of EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life scales across several cancer types: Validation study. Eur. J. Cancer 2022, 170, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejo, M.J.; Bell, M.L.; Dhillon, H.M.; Vardy, J.L. Baseline quality of life is associated with survival among people with advanced lung cancer. J. Psychosoc. Oncol. 2020, 38, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, T.A.; Chrystal, K.F.; Harper, P.G. Quality of life and the treatment of advanced lung cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2003, 5, 28–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinten, C.; Martinelli, F.; Coens, C.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Ringash, J.; Gotay, C.; Bjordal, K.; Greimel, E.; Reeve, B.B.; Maringwa, J.; et al. A global analysis of multitrial data investigating quality of life and symptoms as prognostic factors for survival in different tumor sites. Cancer 2014, 120, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Roughley, A.; Rider, A.; Taylor-Stokes, G. The symptom burden of non-small cell lung cancer in the USA: A real-world cross-sectional study. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohan, A.; Singh, P.; Singh, S.; Goyal, A.; Pathak, A.; Mohan, C.; Guleria, R. Quality of life in lung cancer patients: Impact of baseline clinical profile and respiratory status. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2007, 16, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xará, S.; Amaral, T.F.; Parente, B. Undernutrition and quality of life in non small cell lung cancer patients. Rev. Port. De Pneumol. 2011, 17, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, L.D. Self-care strategies used by patients with lung cancer to promote quality of life. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2010, 37, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, M.J.; Cooper, B.; Paul, S.M.; Kober, K.M.; Cartwright, F.; Conley, Y.P.; Wright, F.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Identification of Distinct Symptom Profiles in Cancer Patients Using a Pre-Specified Symptom Cluster. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2022, 64, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.H.; Yu, S.; Lin, K.C.; Wu, Y.C.; Wang, T.J.; Wang, K.Y. The determinants of health-related quality of life among patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer in Taiwan: A cross-sectional study. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2023, 86, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedadi, A.; Shakik, S.; Brown, M.C.; Lok, B.H.; Shepherd, F.A.; Leighl, N.B.; Sacher, A.; Bradbury, P.A.; Xu, W.; Liu, G.; et al. The impact of symptoms and comorbidity on health utility scores and health-related quality of life in small cell lung cancer using real world data. Qual Life Res. 2021, 30, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chie, W.C.; Yang, C.H.; Hsu, C.; Yang, P.C. Quality of life of lung cancer patients: Validation of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-LC13. Qual Life Res. 2004, 13, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mols, F.; Husson, O.; Oudejans, M.; Vlooswijk, C.; Horevoorts, N.; van de Poll-Franse, L.V. Reference data of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire: Five consecutive annual assessments of approximately 2000 representative Dutch men and women. Acta Oncol. 2018, 57, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miret, C.; Orive, M.; Sala, M.; García-Gutiérrez, S.; Sarasqueta, C.; Legarreta, M.J.; Redondo, M.; Rivero, A.; Castells, X.; Quintana, J.M.; et al. Reference values of EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-BR23, and EQ-5D-5L for women with non-metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis and 2 years after. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, C.D.; Schlichting, M.; Zhang, X. Interpreting Within-Patient Changes on the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC13. Patient 2022, 15, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, J.; Gupta, V.; Amirazodi, E.; Allen-Ayodabo, C.; Jivraj, N.; Jeong, Y.; Davis, L.E.; Mahar, A.L.; De Mestral, C.; Saarela, O.; et al. Textbook Outcome and Survival in Patients With Gastric Cancer: An Analysis of the Population Registry of Esophageal and Stomach Tumours in Ontario (PRESTO). Ann. Surg. 2022, 275, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.C.; Shun, S.C.; Liao, W.Y.; Yu, C.J.; Yang, P.C.; Lai, Y.H. Quality of life and related factors in patients with newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer: A longitudinal study. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, E44–E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montazeri, A.; Milroy, R.; Hole, D.; McEwen, J.; Gillis, C.R. How quality of life data contribute to our understanding of cancer patients’ experiences? A study of patients with lung cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.K.; Cooley, M.E.; Chernecky, C.; Sarna, L. A symptom cluster and sentinel symptom experienced by women with lung cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2011, 38, E425–E435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, M.; Ljung, L.; Johansson, B.B. Health-related quality of life in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Correlates and comparisons to normative data. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2012, 21, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, S.; Naito, T.; Mitsunaga, S.; Omae, K.; Mori, K.; Inano, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Tatematsu, N.; Okayama, T.; Morikawa, A.; et al. A randomized phase II study of nutritional and exercise treatment for elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung or pancreatic cancer: The NEXTAC-TWO study protocol. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H.M.; van der Ploeg, H.P.; Bell, M.L.; Boyer, M.; Clarke, S.; Vardy, J. The impact of physical activity on fatigue and quality of life in lung cancer patients: A randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowntree, R.A.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Lung Cancer and Self-Management Interventions: A Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.Q.; Xie, J. Effects of Breathing Exercises on Patients With Lung Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2019, 46, 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Chouaid, C.; Agulnik, J.; Goker, E.; Herder, G.J.; Lester, J.F.; Vansteenkiste, J.; Finnern, H.W.; Lungershausen, J.; Eriksson, J.; Kim, K.; et al. Health-related quality of life and utility in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A prospective cross-sectional patient survey in a real-world setting. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2013, 8, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, G.-C.; Chiu, C.-H.; Yu, C.-J.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-H.; Hsu, K.-H.; Wu, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsu, H.-H.; Wu, M.-T.; et al. Low-dose CT screening among never-smokers with or without a family history of lung cancer in Taiwan: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2024, 12, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).