Factors Associated with Multimodal Care Practices for Cancer Cachexia among Pharmacists

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Questionnaire

- (a)

- Participant Characteristics

- (b)

- Knowledge and Application of International Definition and Clinical Practice Guidelines

- (c)

- Perception and Knowledge of Cancer Cachexia

- (d)

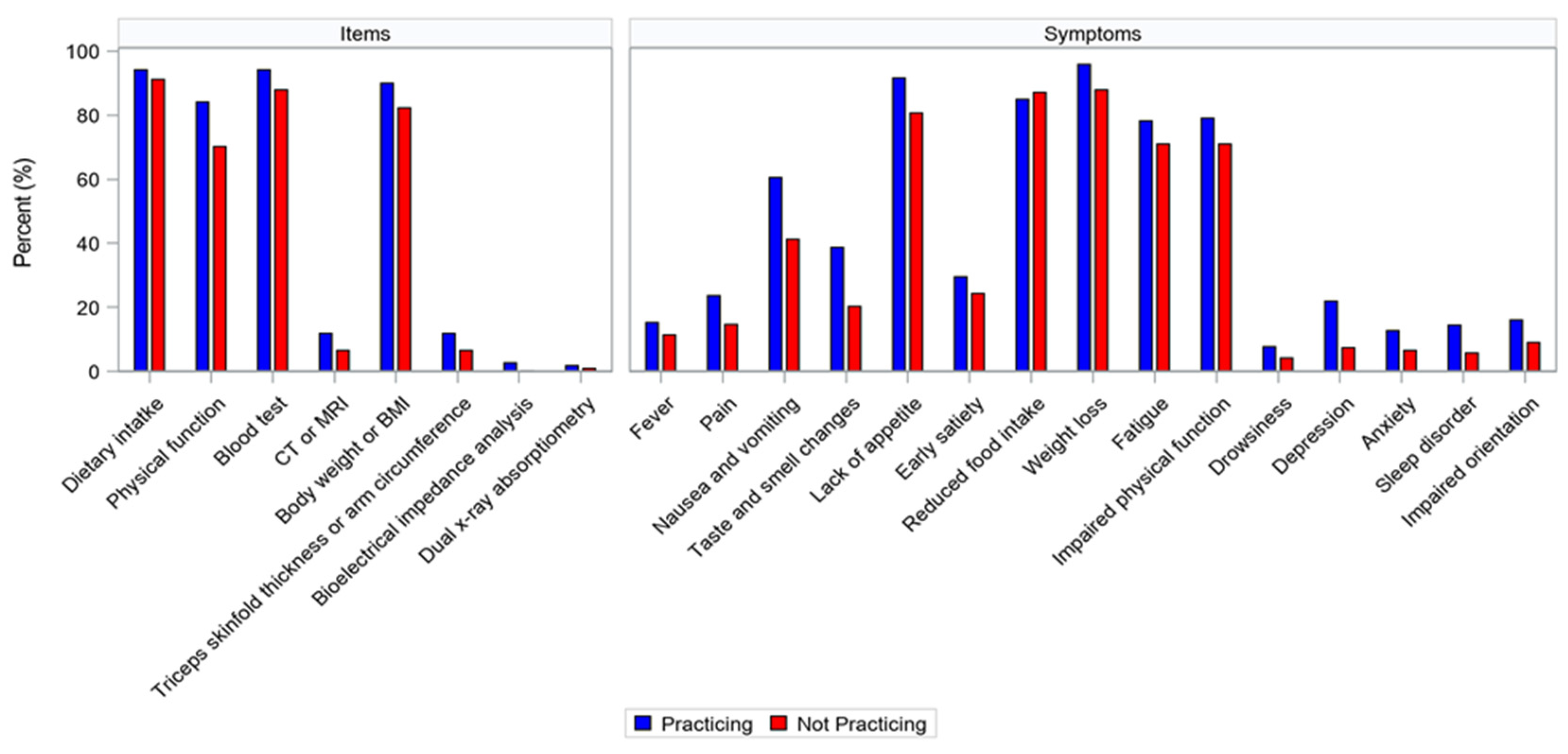

- Items and Symptoms Used in the Assessment of Cancer Cachexia

- (e)

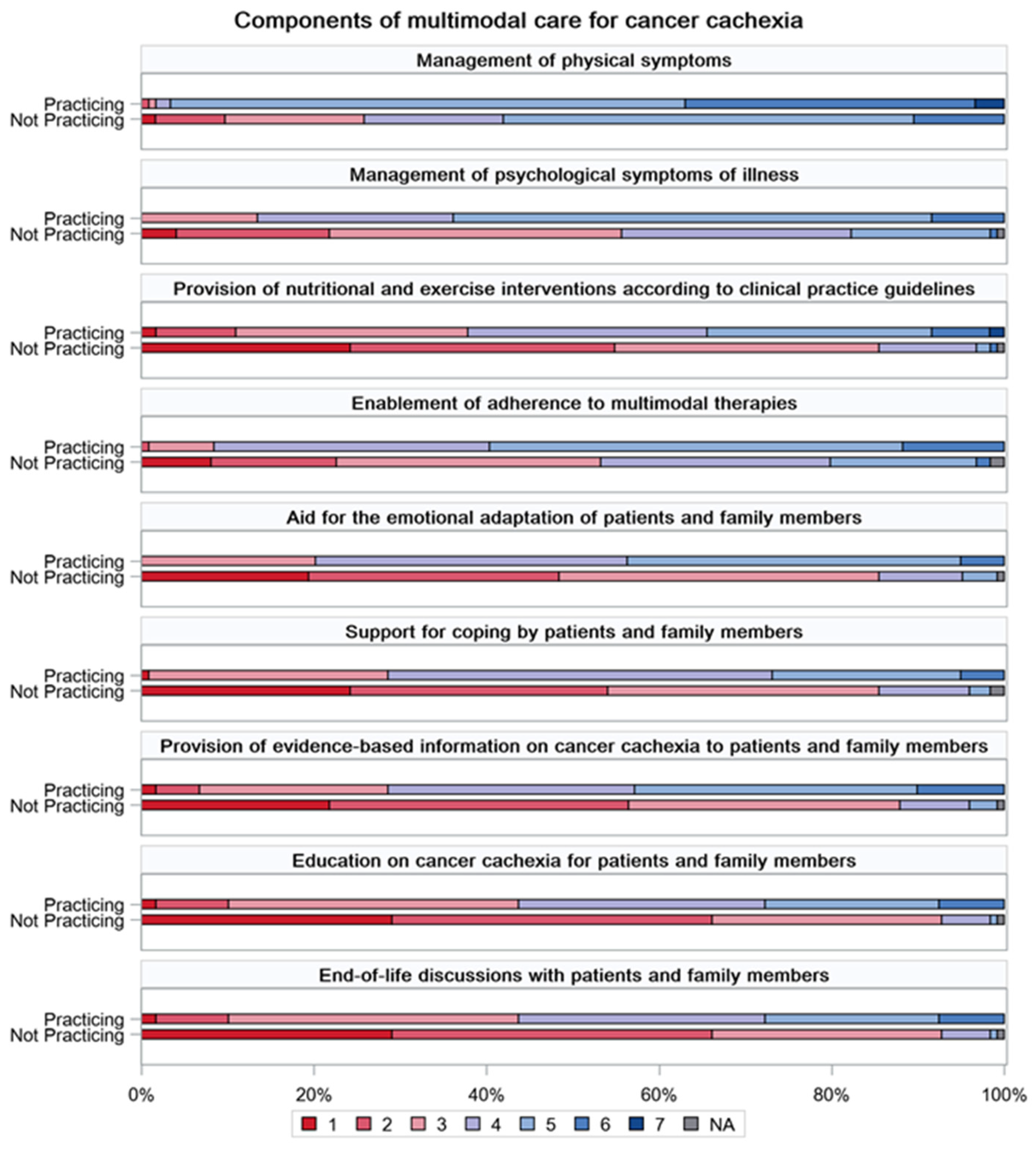

- Beliefs and Perceptions of Multimodal Care for Cancer Cachexia

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearon, K.; Strasser, F.; Anker, S.D.; Bosaeus, I.; Bruera, E.; Fainsinger, R.L.; Jatoi, A.; Loprinzi, C.; MacDonald, N.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011, 12, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baracos, V.E.; Martin, L.; Korc, M.; Guttridge, D.C.; Fearon, K.C.H. Cancer-associated cachexia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Anthony, T.G.; Ayres, J.S.; Biffi, G.; Brown, J.C.; Caan, B.J.; Cespedes Feliciano, E.M.; Coll, A.P.; Dunne, R.F.; Goncalves, M.D.; et al. Cachexia: A systemic consequence of progressive, unresolved disease. Cell 2023, 186, 1824–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, K.; Hopkinson, J.; Baracos, V. Psychological symptoms of illness and emotional distress in advanced cancer cachexia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2021, 25, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, P.; Buckle, P.; Dolan, R.; Feliu, J.; Hui, D.; Laird, B.J.A.; Maltoni, M.; Moine, S.; Morita, T.; Nabal, M.; et al. Management of Cancer Cachexia: AS-CO Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 2438–2453. [Google Scholar]

- Arends, J.; Strasser, F.; Gonella, S.; Solheim, T.; Madeddu, C.; Ravasco, P.; Buonaccorso, L.; de van der Schueren, M.; Baldwin, C.; Chasen, M.; et al. Cancer cachexia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines☆. ESMO Open 2021, 6, 100092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Hütterer, E.; Isenring, E.; Kaasa, S.; et al. ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in cancer. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2898–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Hopkinson, J.B.; Baracos, V.E.; Mori, N. Holistic multimodal care for patients with cancer cachexia and their family caregivers. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Yamada, Y.; Iihara, H.; Suzuki, A. The role of pharmacists in multimodal cancer cachexia care. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T. Blazing a trail in cancer cachexia care. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 10, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walko, C.; Kiel, P.J.; Kolesar, J. Precision medicine in oncology: New practice models and roles for oncology phar-macists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, 1935–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.J.; Yan, Y.D.; Wang, W.J.; Xu, T.; Gu, Z.C.; Bai, Y.R.; Lin, H.W. Preliminary exploration on the role of clinical pharma-cists in cancer pain pharmacotherapy. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 3070–3077. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shank, B.R.; Schwartz, R.N.; Fortner, C.; Finley, R.S. Advances in oncology pharmacy practice. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2015, 72, 2098–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, M.J.; Browne, C.; Nikitin, R.V.; Wooten, N.R.; Ball, S.; Adams, R.S.; Barth, K. Physicians report adopting safer opi-oid prescribing behaviors after academic detailing intervention. Subst. Abus. 2018, 39, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscaritoli, M.; Fanelli, F.R.; Molfino, A. Perspectives of health care professionals on cancer cachexia: Results from three global surveys. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 2230–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baracos, V.E.; Coats, A.J.; Anker, S.D.; Sherman, L.; Klompenhouwer, T. Identification and management of cancer cachexia in patients: Assessment of healthcare providers’ knowledge and practice gaps. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, T.; Wakabayashi, H.; Aso, S.; Konishi, M.; Saitoh, M.; Baracos, V.E.; Coats, A.J.; Anker, S.D.; Sherman, L.; Klompenhouwer, T.; et al. The barriers to interprofessional care for cancer cachexia among Japanese healthcare providers: A nationwide survey. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 15, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, K.; Koshimoto, S.; Hopkinson, J.B.; Baracos, V.E.; Mori, N.; Morita, T.; Oyamada, S.; Ishiki, H.; Satomi, E.; Takeuchi, T. Perspectives of health care professionals on multimodal interventions for cancer cachexia. Palliat. Med. Rep. 2022, 3, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eba, J.; Nakamura, K. Overview of the ethical guidelines for medical and biological research involving human subjects in Japan. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 2022, 52, 539–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oken, M.M.; Creech, R.H.; Tormey, D.C.; Horton, J.; Davis, T.E.; McFadden, E.T.; Carbone, P.P. Toxicity and response crite-ria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982, 5, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soumerai, S.B.; Avorn, J. Principles of educational outreach (‘academic detailing’) to improve clinical decision making. JAMA 1990, 263, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | Group Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | Group Not Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 243 | N = 119 | N = 124 | ||

| Age, years | 40.0 ± 7.6 | 40.1 ± 7.1 | 40.0 ± 8.2 | 0.945 |

| Sex, male | 136 (56.0%) | 68 (57.1%) | 68 (54.8%) | 0.710 |

| Practicing experience | 0.072 | |||

| 3–4 years | 11 (4.5%) | 5 (4.2%) | 6 (4.8%) | |

| 5–9 years | 60 (24.7%) | 24 (20.2%) | 36 (29.0%) | |

| 10–19 years | 106 (43.6%) | 62 (52.1%) | 44 (35.5%) | |

| 20 or more years | 64 (26.3%) | 27 (22.7%) | 37 (29.8%) | |

| Practicing experience in cancer care | 0.200 | |||

| 2 or fewer years | 18 (7.4%) | 9 (7.6%) | 9 (7.3%) | |

| 3–4 years | 26 (10.7%) | 8 (6.7%) | 18 (14.5%) | |

| 5–9 years | 76 (31.3%) | 35 (29.4%) | 41 (33.1%) | |

| 10–19 years | 108 (44.4%) | 58 (48.7%) | 50 (40.3%) | |

| 20 or more years | 14 (5.8%) | 9 (7.6%) | 5 (4.0%) | |

| Number of patients with advanced cancer/month | 0.004 | |||

| 1–9 | 36 (14.8%) | 10 (8.4%) | 26 (21.0%) | |

| 10–19 | 76 (31.3%) | 33 (27.7%) | 43 (34.7%) | |

| 20–49 | 88 (36.2%) | 48 (40.3%) | 40 (32.3%) | |

| 50–99 | 27 (11.1%) | 19 (16.0%) | 8 (6.5%) | |

| 100 or more | 10 (4.1%) | 7 (5.9%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| Primary area of practice | 0.497 | |||

| Palliative care | 96 (39.5%) | 45 (37.8%) | 51 (41.1%) | |

| Cancer treatment | 124 (51.0%) | 65 (54.6%) | 59 (47.6%) | |

| Others | 20 (8.2%) | 8 (6.7%) | 12 (9.7%) | |

| Frequency of caring for patients with advanced cancer | < 0.001 | |||

| Regularly | 145 (59.7%) | 88 (73.9%) | 57 (46.0%) | |

| Only the first time or when needed | 94 (38.7%) | 30 (25.2%) | 64 (51.6%) | |

| Receiving training programs on the management of cancer cachexia, yes | 18 (7.4%) | 14 (11.8%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.012 |

| Group Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | Group Not Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 119 | N = 124 | ||

| International definition of cancer cachexia | |||

| Knowledge, yes | 73 (61.3%) | 38 (30.6%) | <0.001 |

| Application, yes | 49 (41.2%) | 18 (14.5%) | <0.001 |

| ASCO guidelines | |||

| Knowledge, yes | 49 (41.2%) | 27 (21.8%) | 0.001 |

| Application, yes | 16 (13.4%) | 7 (5.6%) | 0.034 |

| ESMO guidelines | |||

| Knowledge, yes | 27 (22.7%) | 10 (8.1%) | 0.002 |

| Application, yes | 7 (5.9%) | 3 (2.4%) | 0.288 |

| ESPEN guidelines | |||

| Knowledge, yes | 33 (27.7%) | 11 (8.9%) | <0.001 |

| Application, yes | 16 (13.4%) | 2 (1.6%) | <0.001 |

| Group Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | Group Not Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 119 | N = 124 | ||

| Weight loss rate | |||

| Status considered as cancer cachexia | 0.104 | ||

| <2% | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| ≥2% | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| ≥5% | 90 (75.6%) | 81 (65.3%) | |

| ≥10% | 27 (22.7%) | 35 (28.2%) | |

| ≥15% | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| ≥20% | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (3.2%) | |

| Initiation of nutritional and physical interventions | 0.092 | ||

| <2% | 4 (3.4%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| ≥2% | 27 (22.7%) | 25 (20.2%) | |

| ≥5% | 72 (60.5%) | 63 (50.8%) | |

| ≥10% | 15 (12.6%) | 29 (23.4%) | |

| ≥15% | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| ≥20% | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | |

| ECOG PS | |||

| Status considered as cancer cachexia | 0.648 | ||

| PS 0 | 2 (1.7%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| PS 1 | 16 (13.4%) | 15 (12.1%) | |

| PS 2 | 70 (58.8%) | 64 (51.6%) | |

| PS 3 | 29 (24.4%) | 40 (32.3%) | |

| PS 4 | 2 (1.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| Initiation of nutritional and physical interventions | 0.817 | ||

| PS 0 | 10 (8.4%) | 8 (6.5%) | |

| PS 1 | 47 (39.5%) | 51 (41.1%) | |

| PS 2 | 55 (46.2%) | 61 (49.2%) | |

| PS 3 | 6 (5.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | |

| PS 4 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Life expectancy | |||

| Status considered as cancer cachexia | 0.849 | ||

| <1 week | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| <2 weeks | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | |

| <1 month | 10 (8.4%) | 12 (9.7%) | |

| <3 months | 25 (21.0%) | 24 (19.4%) | |

| <6 months | 15 (12.6%) | 20 (16.1%) | |

| Unrelated | 69 (58.0%) | 67 (54.0%) | |

| Initiation of nutritional and physical interventions | 0.286 | ||

| <1 week | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| <2 weeks | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| <1 month | 1 (0.8%) | 6 (4.8%) | |

| <3 months | 6 (5.0%) | 6 (4.8%) | |

| <6 months | 14 (11.8%) | 11 (8.9%) | |

| Unrelated | 98 (82.4%) | 100 (80.6%) | |

| Group Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | Group Not Practicing Multimodal Cachexia Care | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 119 | N = 124 | ||

| Guidelines | |||

| Number of guidelines used | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.75 (0.94) | 0.24 (0.60) | |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | |

| Range | 0.0–4.0 | 0.0–4.0 | |

| Items | |||

| Number of items used | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.91 (0.82) | 3.49 (1.02) | |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (4.0–4.0) | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | |

| Range | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–6.0 | |

| Symptoms | |||

| Number of symptoms used | < 0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.69 (2.88) | 5.41 (2.85) | |

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | |

| Range | 0.0–15.0 | 0.0–15.0 |

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | ||

| Number of patients with advanced cancer/month (ref = 1–9) | ||

| 10–19 | 1.31 (0.49–3.47) | 0.587 |

| 20–49 | 1.65 (0.62–4.35) | 0.315 |

| 50–99 | 3.31 (0.92–11.93) | 0.068 |

| 100 or more | 2.93 (0.56–15.42) | 0.205 |

| Frequency of caring for patients with advanced cancer (ref = only the first time or when needed) | ||

| Regularly | 2.07 (1.10–3.92) | 0.025 |

| Participation in training programs on the management of cancer cachexia (ref = no) | ||

| Yes | 2.76 (0.78–9.83) | 0.116 |

| International definition used in the assessment of cancer cachexia | ||

| Application of the international definition of cancer cachexia (ref = no) | ||

| Yes | 1.81 (0.64–5.10) | 0.265 |

| Guidelines, items, and symptoms used in the assessment of cancer cachexia | ||

| Number of guidelines used | 1.55 (0.83–2.92) | 0.172 |

| Number of items used | 1.17 (0.80–1.72) | 0.421 |

| Number of symptoms used | 1.12 (0.99–1.26) | 0.078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okamura, S.; Amano, K.; Koshimoto, S.; Arakawa, S.; Ishiki, H.; Satomi, E.; Morita, T.; Takeuchi, T.; Mori, N.; Yamada, T. Factors Associated with Multimodal Care Practices for Cancer Cachexia among Pharmacists. Curr. Oncol. 2024, 31, 6133-6143. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100457

Okamura S, Amano K, Koshimoto S, Arakawa S, Ishiki H, Satomi E, Morita T, Takeuchi T, Mori N, Yamada T. Factors Associated with Multimodal Care Practices for Cancer Cachexia among Pharmacists. Current Oncology. 2024; 31(10):6133-6143. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100457

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkamura, Satomi, Koji Amano, Saori Koshimoto, Sayaka Arakawa, Hiroto Ishiki, Eriko Satomi, Tatsuya Morita, Takashi Takeuchi, Naoharu Mori, and Tomomi Yamada. 2024. "Factors Associated with Multimodal Care Practices for Cancer Cachexia among Pharmacists" Current Oncology 31, no. 10: 6133-6143. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100457

APA StyleOkamura, S., Amano, K., Koshimoto, S., Arakawa, S., Ishiki, H., Satomi, E., Morita, T., Takeuchi, T., Mori, N., & Yamada, T. (2024). Factors Associated with Multimodal Care Practices for Cancer Cachexia among Pharmacists. Current Oncology, 31(10), 6133-6143. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol31100457