Abstract

Purpose: Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) is an uncommon astrocytoma that tends to occur in children and young adults and has a relatively favorable prognosis. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system (CNS WHO), 5th edition, rates PXAs as grade 2 and grade 3. The histological grading was based on mitotic activity (≥2.5 mitoses/mm2). This study specifically evaluates the clinical, morphological, and, especially, the molecular characteristics of grade 2 and 3 PXAs. Methods: Between 2003 and 2021, we characterized 53 tumors with histologically defined grade 2 PXA (n = 36, 68%) and grade 3 PXA (n = 17, 32%). Results: Compared with grade 2 PXA, grade 3 PXA has a deeper location and no superiority in the temporal lobe and is more likely to be accompanied by peritumoral edema. In histomorphology, epithelioid cells and necrosis were more likely to occur in grade 3 PXA. Molecular analysis found that the TERT promoter mutation was more prevalent in grade 3 PXA than in grade 2 PXA (35% vs. 3%; p = 0.0005) and all mutation sites were C228T. The cases without BRAF V600E mutation or with necrosis in grade 3 PXA had a poor prognosis (p = 0.01). Conclusion: These data define PXA as a heterogeneous astrocytoma. Grade 2 and grade 3 PXAs have different clinical and histological characteristics as well as distinct molecular profiles. TERT promoter mutations may be a significant genetic event associated with anaplastic progression. Necrosis and BRAF V600E mutation play an important role in the prognosis of grade 3 PXA.

1. Introduction

Categorized in circumscribed astrocytic gliomas in the 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system, 5th edition (CNS WHO), pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma (PXA) predominantly affects children and young adults [,]. PXA is usually located in the cerebral hemisphere, mostly in the temporal lobe, and tends to grossly appear as a superficial cystic and solid mass []. Grade 2 PXA has a relatively favorable prognosis [,,]. Grade 3 PXA is diagnosed solely on the basis of tumor histopathologic features and requires increased proliferative activity, the count of ≥5 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (corresponding to 4 mm2). Grade 3 PXA manifests both at initial diagnosis and at recurrence. In one series, anaplasia was present in 31% of the cases at first diagnosis []. The anaplastic progression of PXA may demonstrate less pleomorphism, more diffuse infiltration, and more necrosis, with higher mitotic activity, than typical classic grade 2 PXA in histological features and leads to a significantly worse survival [,,].

PXAs are characterized by a high frequency of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway alterations. The BRAF point mutation rates in PXA reported in the literature range from 60% to 78% [,], and most are the V600E type. Other MAPK alterations have been identified in a smaller fraction of PXA, including BRAF insertion/deletion mutations []. Homozygous 9p21.3 deletions involving the CDKN2A/B loci have been identified in grade 2 and 3 PXAs. Initial studies identified this gene homozygous deletion in approximately 60% of the cases [], while more recent reports have found a higher incidence (>85%) [,,].

In grade 3 PXA, recent studies detected telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) alteration promoter mutation in 7 of 15 cases (47%), with gene amplification (n = 2) or promoter hotspot mutation (n = 5). However, the cohort of grade 2 tumors was too small (n = 4) to compare grade 2 and grade 3 tumors []. TERT promoter mutations were identified in 2.0% (1/53) of grade 2 and 14.3% (2/14) of grade 3 PXAs []. Although we have more clarity regarding certain molecular events in PXA, whether there are molecular markers associated with anaplastic progression is yet to be confirmed. To better understand the biological characteristics of grade 2 and grade 3 PXAs, we detected and compared the expression of conventional genes and clinical and morphological features in 37 grade 2 PXAs and 20 grade 3 PXAs including the recurrence samples. Our results confirm that the majority of PXAs are characterized by MAPK activation. Necrosis and BRAF V600E mutation may be important prognostic factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Case Selection

In this retrospective study, a total of 57 tumors (37 grade 2 PXAs and 20 grade 3 PXAs) from 53 patients were received from the Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, from 2003 to 2021. In three of the patients, tumors had recurred. Two senior neuropathologists reviewed and confirmed all tissue samples from primary or recurrent tumors to represent the PXAs according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of the central nervous system. All samples were routinely formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded. A final diagnosis was made on the basis of histopathological examinations, immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses, and molecular tests.

2.2. DNA Extraction

Each tumor sample used for DNA extraction was histologically verified to contain vital PXA tissue with an estimated tumor cell content ≥80%. Samples were obtained as formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue (five sections, each 7 µm thick) from patients with PXA. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Amoy Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China). DNA purity and quantification were assessed using the NanoDrop 2000 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products, Wilmington, DE, USA).

2.3. BRAF V600E Analysis

BRAF V600E analysis was performed on an MX3000p real-time PCR system with BRAF V600E Diagnostic Kit (Amoy Diagnostics Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.4. TERT Promoter Mutation Analysis

Sanger sequencing was used to analyze the mutation hotspots in the TERT promoter. Mutations in the TERT promoter had previously been identified mainly as C228T and C250T. For the analysis, the TERT promoter mutation analysis kit (Sinomdgene Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.5. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

CDKN2A, EGFR, and PTEN statuses were identified via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), using the CDKN2A (9p21), the EGFR (7p11), and PTEN (10q23) probes (ABP Medicine Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China). An abnormal probe signal counted as at least 15% of the nucleus, and an abnormal signal counted a minimum of 20 consecutive non-overlapping tumor nuclei.

3. Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics between groups were compared using the chi-square test as appropriate. Cumulative survival probabilities were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The log rank test was used to compare survival across groups. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the duration from the date of initial surgery to that of either death or the last follow-up, with a censoring cutoff date of 30 November 2021 without accounting for eight patients who were lost to follow-up (cases 29 to 34 and cases 52 and 53). Patients alive at the last follow-up were considered censored during the survival analysis. In all analyses, p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Patient Demographics

Table 1 summarizes the clinical features of PXA. It occurs equally in male and female patients and typically develops in children and young adults. Children have no obvious superiority in incidence rate. The temporal lobe was the most common site of PXA. Grade 2 PXA more often involves the cerebral cortex; epilepsy symptoms are more common in patients. In all, eight patients were lost to follow-up, and our data do not contain the surgical status of the 8 patients at the time because some patients were considerably aged. In addition, 13 patients did not have enhanced cranial MRI at our medical center.

Table 1.

Clinical pathological features of PXA.

In our series, most of our grade 3 PXA cases were de novo. Only in three cases did the grade 3 tumor recur: in cases 19 and 22, the tumors recurred with anaplastic transformation after incomplete resection and following radiation therapy in 6 months and 18 months, respectively, and in case 33, the tumor recurred 30 months later, without any treatment, after total tumor resection.

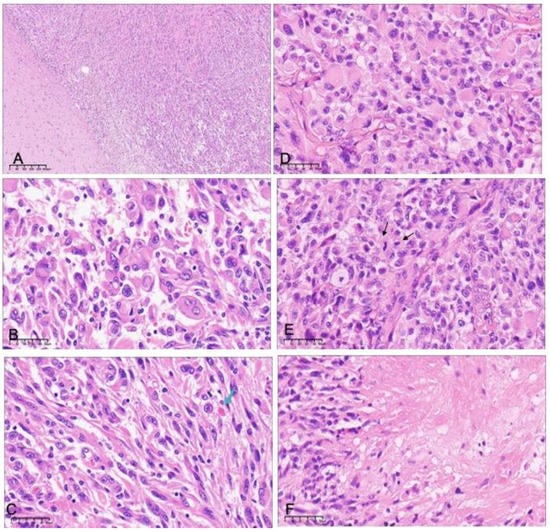

4.2. Morphologic Patterns of PXA

The histological findings are summarized in Table 2. In this study, most of the tumors had boundaries, and a few cases presented infiltrating growth patterns (Figure 1A). The neoplastic cells were pleomorphic and multinucleated (Figure 1B). Epithelial cells were more present in grade 3 PXA (p = 0.0003). Lymphoid cuffs and xanthomatous change could be seen in almost all cases. Some cases showed eosinophilic granular bodies (EGB) (Figure 1C). We found non-palisading (focal) necrosis in only four grade 3 PXA cases (Figure 1F). Microvascular proliferation and palisading necrosis were not seen in any of the cases. In some of the primary cases of grade 3 PXA, the typical morphology of grade 2 PXA could be seen around the tissue with anaplastic features. However, in grade 3 PXA, eosinophilic bodies (p = 0.01) and xanthomatous cells (p = 0.04) were reduced to varying degrees compared with grade 2 PXA.

Table 2.

Histological features of PXA.

Figure 1.

Histopathologic features of grade 2 (A–C) and grade 3 (D–F) pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. (A) There is a clear boundary between the tumor and the brain tissue in grade 2 PXA (H&E ×40). There is an admixture of spindle cells and neoplastic cells with bizarre nuclei or multinucleation (B) and eosinophilic granular bodies (C, arrows) (H&E ×400). Grade 3 pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma showing (D) a more pronounced epithelioid component, (E) high levels of mitotic activity (arrows), and (F) focal necrosis (H&E ×400).

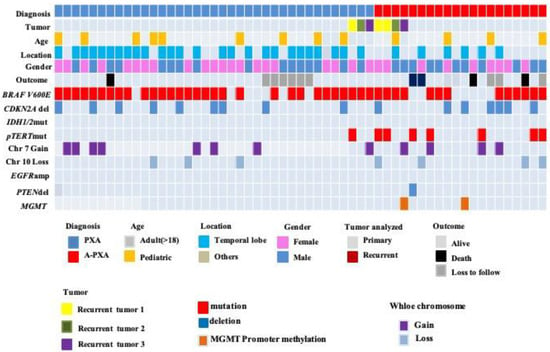

4.3. Molecular Results

Table 3 and Figure 2 summarize the molecular detection results. BRAF V600E mutation was the most frequent gene alteration in our series, not related to PXA histological grade (p = 0.18). The mutant status of BRAF V600E in our three relapse cases did not change with or without treatment. Most BRAF mutation-positive cases occurred in the temporal lobe (25/43, 58%).

Table 3.

Molecular characteristics of the cases of PXA.

Figure 2.

Clinical and molecular characteristics of the patient cohort. BRAF V600E mutations were identified by immunohistochemistry (IHC) or real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR). MGMT promoter methylation status was assessed by methylation-specific real-time PCR system with an MGMT methylation analysis kit. TERT promoter mutations were identified by Sanger sequencing, and all of the mutation sites were C228T. CDKN2A/B, EGFR, and PTEN statuses were identified via fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

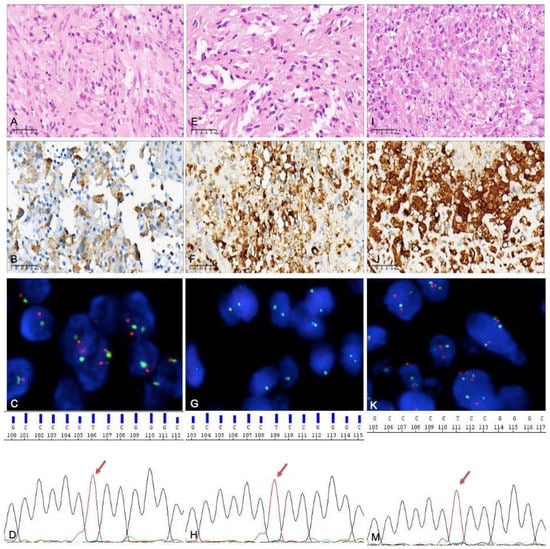

TERT promoter mutation has obvious advantages in grade 3 PXA; only one was detected in grade 2 PXA. All of the mutation sites were C228T. Cases 19, 46, and 53 were diagnosed as grade 2, grade 3 (the first recurrence), and grade 3 (the second recurrence) PXA, respectively (all three tumors from the same patient). The tumor was in the corpus callosum and underwent an incomplete resection. In the three cases, both TERT promoter C228T and BRAF V600E mutations were constantly present, while CDKN2A homozygous deletion was only seen in the first recurrence (case 46) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Histological molecular examination results for a tumor that recurred twice after incomplete excision: (A–D) case 19 (the primary tumor), (E–G) case 46 (the first relapse), and (I–K,M) case 53 (the second relapse). (A) An area composed of mostly spindle cells and some multinucleated cells. (B) BRAF V600E expressed by tumor cells (by immunohistochemistry). (C) CDKN2A identified via FISH, with no homozygous deletion. (D) TERT promoter mutation detected by PCR; the site was C228T. (E) Spindle cell areas can still be seen in the tumor with first recurrence. (F) BRAF V600E expressed by tumor cells. (G) CDKN2A homozygous deletion identified via FISH. (H) TERT promoter mutation; the site was C228T. (I) Epithelioid cells as the main component, accompanied by significant nuclear atypia. (J) BRAF V600E expressed by tumor cells. (K) There was no CDKN2A homozygous deletion. (M) TERT promoter mutation; the site was still C228T.

The proportion of CDKN2A homozygous deletion in our cases was 30.2% (n = 16), and there was no significant association between grade 2 and grade 3 PXA. None of the cases had IDH1/2 gene mutations. Methylation of the MGMT promoter occurred only in two cases of grade 3 PXA. The chromosome 7 gain was also detected in grade 2 PXA (n = 7) and grade 3 PXA (n = 5). The chromosome 10 loss was discovered in grade 2 PXA (n = 3) and grade 3 PXA (n = 4). The results were not associated with tumor grade or other molecules. No tumors demonstrated concurrent 7 gain/10 loss, characteristically found in IDH-wildtype glioblastoma.

In our results, there were more molecular change events in grade 3 than in grade 2 PXA. In our cohort, the simultaneous occurrence of ≥3 molecular changes in one case was considered a multimolecular change event. A comparison between the two groups of data shows that p = 0.07.

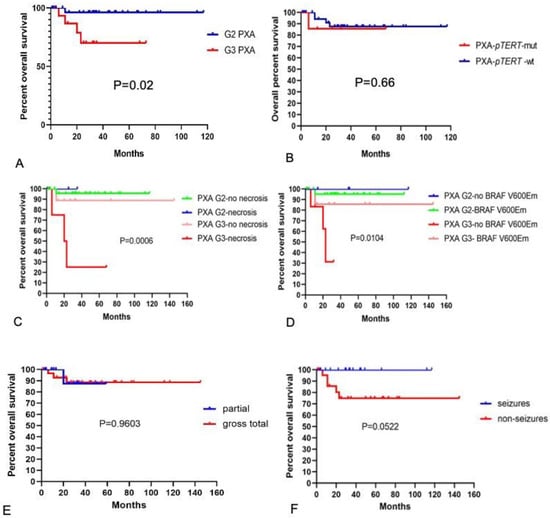

5. Survival

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of 45 PXA cases highlighted the differences in the survival curves of grade 2 and 3 tumors. The overall survival of grade 3 PXA cases was lower than that of grade 2 PXA cases (p = 0.02), demonstrating that the histologic grade was a robust predictor of overall tumor survival (Figure 4A). There was no statistical difference in the overall survival of the cases with TERT promoter mutations compared with those without mutations (Figure 4B). Cases with histological features of necrosis also showed poorer overall survival in grade 3 PXA (Figure 4C), and tumors without BRAF V600E mutation in grade 3 PXA showed a lower survival rate (Figure 4D). There was no statistical difference in overall survival of cases with different extension of resection (Figure 4E); the survival curves of PXA with seizures were slightly higher than those without seizures in our cohort (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Overall survival of PXA. (A) Overall survival for grade 2 and 3 PXA. The blue line shows grade 2 PXA, and the red line depicts grade 3 PXA. The differences between the two groups were statistically significant (p = 0.02). (B) Overall survival in the case of PXA with or without pTERT mutation. The blue line depicts PXA without pTERT mutation, and the red line depicts PXA with pTERT mutation. The differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (p = 0.66). (C) Overall survival of different grades of PXA with and without necrosis. (D) Overall survival of different grades of PXA with and without BRAF V600E mutation. (E) Overall survival of different extension of resection. (F) Overall survival of PXA with and without epileptic symptoms. M, mut, mutation; wt, wildtype.

6. Discussion

Grade 3 PXA may occur de novo at first resection or may evolve from PXA grade 2. Reports suggest that grade 3 PXAs are more likely to occur primarily or to recur mostly in adults [,]. In our cohort, most grade 3 cases were de novo. The temporal lobe was the most prevalent site of PXA [,,,,], and we found that grade 3 PXA bias involved white matter other than cortex in the brain and was more likely to occur beyond the temporal lobe than grade 2 PXA. Grade 3 PXAs were more likely to present imaging features of surrounding edema than grade 2 PXAs in MRI, which is one of the imaging features of high-grade glioma. Epilepsy was more common in grade 2 PXAs due to the superficial location. Studies revealed that epileptic seizures are an independent and positive prognostic factor for low-grade glioma [,]. In line with our data, the survival curve of PXA with seizures was slightly higher than that without seizures in our cohort. Extent of resection is the most significant prognostic factor associated with recurrence, but not of overall survival [,,], consistent with our results.

EGBs, perivascular lymphocytes, xanthic cells, and multinucleated cells are histological features of classic PXA [,] and mainly occur in grade 2 PXAs. Grade 3 PXAs may demonstrate less pleomorphism and a more diffusely infiltrative pattern than their grade 2 counterparts. Histological grade is an important prognostic indicator recognized by the WHO classification of CNS tumors. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis highlighted the differences in survival curves of grade 3 tumors with and without necrosis. However, necrosis in grade 2 tumors was not associated with different outcome. In this case, the low number of cases with outcome data may compromise this distribution. Some studies suggested that necrosis is also a significant predictor of overall survival, but it is still difficult to detect a difference in survival between patients whose tumors had high mitotic counts and necrosis versus those with only necrosis [].

BRAF V600E mutation can be found in 70% of typical PXAs; the frequency is lower in grade 3 PXA than in grade 2 PXA [,,]. The temporally located PXAs also tend to harbor BRAF mutations []. The presence of BRAF V600E mutation in grade 3 PXAs was associated with better prognosis in our cohort. Studies reported in the literature that patients with BRAF V600E mutant tumors had significantly longer overall survival when compared with those without BRAF V600E mutant tumors [,,]. BRAF V600E mutation and further MAPK activating molecular alterations are also frequent events in low-grade glial and glioneuronal tumors [,,,]. The prognostic impact of BRAF mutation is still a matter of debate and requires further studies on the frequency of all MAPK activating alterations in PXAs.

In many studies, CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion has been identified in PXA. However, the frequency at which it has been observed has varied across studies, from approximately 60% up to 100% [,,,]. This variability in detection sensitivity has important implications, as CDKN2A/B is increasingly used as a diagnostic and prognostic marker []. In IDH-mutant astrocytomas, CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion is an adverse prognostic factor. However, there was no difference in the expression between grade 2 and 3 PXAs, nor was there any prognostic implication. Our data showed CDKN2A deletion in grade 2 PXA (26%, n = 9) and grade 3 PXA (37%, n = 7). The CDKN2A deletion rate in our series was lower [,]. Next-generation sequencing of 295 cancer-related genes was used to investigate the molecular profiles of 13 cases of PXA in China. The results showed CDKN2A/B homozygous deletion only in one case []. There may be some differences in gene expression in patients with different ethnicities. In addition, FISH was used to detect the CDKN2A gene in our series. The NGS method used in the studies is more sensitive for gene detection, and the long storage time of blocks in some cases may be one of the factors affecting the quality and results of FISH detection. At present, there is no large case-series study in China on the homozygous deletion ratio of CDKN2A/B in PXA. More research data are needed for comprehensive and objective analysis.

The TERT gene plays an important role in the malignant progression of astrocytic gliomas [,,,,,]. According to the data reported in the literature, altered TERT gene status changes were present in approximately 47% of grade 3 PXA cases, including TERT promoter hotspot mutation and TERT gene amplification []. In our cohort, TERT promoter mutations were detected in seven grade 3 PXA (7/20, 35%) cases. Only one grade 2 PXA case was identified with a TERT promoter mutation, but the tumor recurred as grade 3 PXA within half a year. Our results suggest that compared with grade 2 PXA, grade 3 PXA is more prone to TERT gene alteration (p = 0.005). Grade 2 PXA with TERT gene alteration is more likely to undergo malignant transformation []. Our study was limited by the small number of patients with TERT promoter mutation and by the imperfect follow-up. It could only be confirmed that TERT promoter mutations are more common in grade 3 tumors; no effect of TERT promoter mutation on prognosis was observed. A recent article reported the presence of canonical TERT promoter mutations as a robust indicator for poor prognosis in methylation class PXA (mcPXA). Their results suggest that histologically, PXA and mcPXA may be different entities []. We suggest that alterations in the TERT promoter may be one of the molecular diagnostic criteria for grade 3 PXA.

We also found some cases with a chromosome gain +7 (n = 12) and a chromosome loss −10 (n = 7). None of the cases presented EGFR gene amplification, and only one case showed PTEN gene deletion. These results were not associated with tumor grade or other molecular features, and no tumors demonstrated a concurrent gain +7/loss −10, which is characteristically found in IDH-wild type glioblastoma. This also indicates, to some extent, that the molecular characteristics of grade 3 PXA are different from those of IDH-wildtype glioblastoma.

MGMT promoter methylation occurs in 40% of primary glioblastoma cases and is associated with increased survival after radiotherapy and chemotherapy with temozolomide []. In our series, MGMT promoter hypermethylation was found only in two cases of grade 3 PXAs (3.5%) and emphasized that MGMT promoter hypermethylation is a rare epigenetic event in PXA.

In summary, PXA is a heterogeneous entity. Our data demonstrate that TERT promoter mutations have the highest occurrence in grade 3 PXA and suggest that these mutations may contribute to anaplastic progression and that necrosis and absence of BRAF V600E mutation within grade 3 PXAs are associated with poor prognosis.

Author Contributions

H.Z. and X.-J.M. contributed equally to this work. H.Z. and J.-L.T. drafted the manuscript. X.-J.M. performed the molecular detection. X.-Y.Y. performed the immunohistochemical detection. Q.-Y.W. performed the imaging analysis. H.Z., X.-J.M., X.-P.X. and J.-H.X. collected and analyzed data. H.Z. and J.-H.X. supervised the data collection and revised this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The preparation of this review received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Dec- laration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Medical College of Zhejiang University (protocol code I2022193 and date of approval 7 February 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Louis, D.N.; Perry, A.; Wesseling, P.; Brat, D.J.; Cree, I.A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Hawkins, C.; Ng, H.K.; Pfister, S.M.; Reifenberger, G.; et al. Anaplastic Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma. In WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System; Louis, D.N., Ohgaki, H., Wiestler, O.D., Cavenee, W.K., Eds.; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2021; pp. 330–363. [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrescu, S.; Korshunov, A.; Lai, S.H.; Dabiri, S.; Patil, S.; Li, R.; Shih, C.-S.; Bonnin, J.M.; Baker, J.A.; Du, E.; et al. Epithelioid glioblastomas and anaplastic epithelioid pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma—Same entity or first cousins? Brain Pathol. 2016, 26, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, N.; Brahmbhatt, N.; Kruser, T.J.; Kam, K.L.; Appin, C.L.; Wadhwani, N.; Chandler, J.; Kumthekar, P.; Lukas, R.V. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: A brief review. CNS Oncol. 2019, 8, CNS39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, T.; Miyoshi, H.; Komaki, S.; Arakawa, F.; Morioka, M.; Ohshima, K.; Nakada, M.; Sugita, Y. Clinicopathological and genetic association between epithelioid glioblastoma and pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Neuropathology 2018, 38, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ida, C.M.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Burger, P.C.; Caron, A.A.; Jenkins, S.M.; Spears, G.M.; Aranguren, D.L.; Lachance, D.H.; Giannini, C. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: Natural History and long-term follow-up. Brain Pathol. 2015, 25, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelsche, C.; Sahm, F.; Wöhrer, A.; Jeibmann, A.; Schittenhelm, J.; Kohlhof, P.; Preusser, M.; Romeike, B.; Dohmen-Scheufler, H.; Hartmann, C.; et al. BRAF-mutated pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma is associated with temporal location, reticulin fiber deposition and CD34 expression. Brain Pathol. 2014, 24, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, Y.; Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Aisner, D.L.; Lillehei, K.O.; Damek, D. Anaplastic PXA in adults: Case series with clinicopathologic and molecular features. J. Neurooncol. 2013, 111, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaubel, R.A.; Caron, A.A.; Yamada, S.; Decker, P.A.; Passow, J.E.E.; Rodriguez, F.J.; Rao, A.A.N.; Lachance, D.; Parney, I.; Jenkins, R.; et al. Recurrent copy number alterations in low-grade and anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with and without BRAF V600E mutation. Brain Pathol. 2018, 28, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaubel, R.; Zschernack, V.; Tran, Q.T.; Jenkins, S.; Caron, A.; Milosevic, D.; Smadbeck, J.; Vasmatzis, G.; Kandels, D.; Gnekow, A.; et al. Biology and grading of Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma-what have we learned about it? Brain Pathol. 2021, 31, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.G.; Hoischen, A.; Ehrler, M.; Zipper, P.; Kaulich, K.; Blaschke, B.; Becker, A.J.; Weber-Mangal, S.; Jauch, A.; Radlwimmer, B.; et al. Frequent loss of chromosome 9, homozygous CDKN2A/p 14 ARF/CDKN2B deletion and low TSC1 mRNA expression in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas. Oncogene 2007, 26, 1008–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.J.; Gong, H.; Chen, K.; Joseph, N.M.; van Ziffle, J.; Bastian, B.C.; Grenert, J.P.; Kline, C.N.; Mueller, S.; Banerjee, A.; et al. The genetic landscape of anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Brain Pathol. 2019, 29, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohkamp, L.-N.; Schinz, M.; Gehlhaar, C.; Guse, K.; Thomale, U.-W.; Vajkoczy, P.; Heppner, F.L.; Koch, A. MGMT Promoter Methylation and BRAF V600E Mutations Are Helpful Markers to Discriminate Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma from Giant Cell Glioblastoma. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, C.; Scheithauer, B.W.; Burger, P.C.; Brat, D.B.; Wollan, P.C.; Lach, B.; O’Neill, B.P. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: What do we really know about it? Cancer 1999, 85, 2033–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanksha, S.; Jerome, J.G. Overview of prognostic factors in adult gliomas. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2021, 10, 863–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallud, J.; Audureau, E.; Blonski, M.; Sanai, N.; Bauchet, L.; Fontaine, D.; Mandonnet, E.; Dezamis, E.; Psimaras, D.; Guyotat, J.; et al. Epileptic seizures in diffuse low-grade gliomas in adults. Brain 2014, 137 Pt 2, 449–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, S.M.; Mitra, N.; Fei, W.; Shinohara, E.T. Patterns of care and outcomes of patients with pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: A SEER analysis. J. Neurooncol. 2012, 110, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Feng, R.; Chen, H.; Hameed, N.F.; Aibaidula, A.; Song, Y.; Wu, J. BRAF V600E, TERT, and IDH2 mutations in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: Observations from a large case-series study. World Neurosurg. 2018, 120, e1225–e1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Korshunov, A.; Reifenberger, G.; Capper, D.; Felsberg, J.; Trisolini, E.; Pollo, B.; Calatozzolo, C.; Prinz, M.; Staszewski, O.; et al. Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma is a heterogeneous entity with pTERT mutations prognosticating shorter survival. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2022, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabouret, E.; Bequet, C.; Denicolai, E.; Barrié, M.; Nanni, I.; Metellus, P.; Dufour, H.; Chinot, O.; Figarella-Branger, D. BRAF mutation and anaplasia may be predictive factors of progression-free survival in adult pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 41, 1685–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumura, N.; Nakajima, N.; Yamazaki, T.; Nagano, T.; Kagoshima, K.; Nobusawa, S.; Ikota, H.; Yokoo, H. Concurrent TERT promoter and BRAF V600E mutation in epithelioid glioblastoma and concomitant low-grade astrocytoma. Neuropathology 2017, 37, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, G.; Xing, M. Regulation of mutant TERT by BRAF V600E/MAP kinase pathway through FOS/GABP in human cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Duan, Y.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, J.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Z.; Jin, Z.; et al. Molecular features of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. Hum. Pathol. 2019, 86, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Aisner, D.L.; Foreman, N. BRAF VE1 immunoreactivity patterns in epithelioid glioblastomas positive for BRAF V600E mutation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2015, 39, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stichel, D.; Ebrahimi, A.; Reuss, D.; Schrimpf, D.; Ono, T.; Shirahata, M.; Reifenberger, G.; Weller, M.; Hänggi, D.; Wick, W.; et al. Distribution of EGFR amplification, combined chromosome 7 gain and chromosome 10 loss, and TERT promoter mutation in brain tumors and their potential for the reclassification of IDHwt astrocytoma to glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2018, 136, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters, B.K.; Alassiri, A.H.; Birks, D.K.; Newell, K.L.; Moore, W.; Lillehei, K.O. Epithelioid versus rhabdoid glioblastomas are distinguished by monosomy 22 and immunohistochemical expression of INI-1 but not Gaudin 6. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010, 34, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckel-Passow, J.E.; Lachance, D.H.; Molinaro, A.M.; Walsh, K.M.; Decker, P.A.; Sicotte, H.; Pekmezci, M.; Rice, T.W.; Kosel, M.L.; Smirnov, I.V.; et al. Glioma groups based on 1p/19q, IDH, and TERT promoter mutations in tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2499–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diplas, B.H.; He, X.; Brosnan-Cashman, J.A.; Liu, H.; Chen, L.H.; Wang, Z.; Moure, C.J.; Killela, P.J.; Loriaux, D.B.; Lipp, E.S.; et al. The genomic landscape of TERT promoter wildtype-IDH wildtype glioblastoma. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosono, J.; Nitta, M.; Masui, K.; Maruyama, T.; Komori, T.; Yokoo, H.; Saito, T.; Muragaki, T.; Kawamata, T. Role of a promoter mutation in TERT in Malignant Transformation of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma. World Neurosurg. 2019, 126, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Murugan, A.K.; Zhu, G.; Zeiger, M.A.; Pai, S.; Bishop, J. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with the highest recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2718–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).