Abstract

Sexual health is compromised by the diagnosis and treatment of virtually all cancer types. Despite the prevalence and negative impact of sexual dysfunction, sexual health clinics are the exception in cancer centers. Consequently, there is a need for effective, efficient, and inclusive sexual health programming in oncology. This paper describes the development of the innovative Sexual Health Clinic (SHC) utilizing a hybrid model of integrated in-person and virtual care. The SHC evolved from a fusion of the in-person and virtual prostate cancer clinics at Princess Margaret. This hybrid care model was adapted to include six additional cancer sites (cervical, ovarian, testicular, bladder, kidney, and head and neck). The SHC is theoretically founded in a biopsychosocial framework and emphasizes interdisciplinary intervention teams, participation by the partner, and a medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach. Virtual visits are tailored to patients based on biological sex, cancer type, and treatment type. Highly trained sexual health counselors facilitate the virtual clinic and provide an additional layer of personalization and a “human touch”. The in-person visits complement virtual care by providing comprehensive sexual health assessment and sexual medicine prescription. The SHC is an innovative care model which has the potential to close the gap in sexual healthcare. The SHC is designed as a transferable, stand-alone clinic which can be shared with cancer centers.

1. Introduction

Sexual health is compromised by the diagnosis and treatment of virtually all cancer types [1]. The nature of sexual dysfunction (SD) can differ by type of cancer and treatment but invariably involves biological, psychological, and interpersonal factors that negatively affect the patient’s overall health-related quality of life [2]. Despite the gravity of SD and the associated psychosocial sequelae, sexual health clinics are the exception in cancer centers worldwide [3,4]. This considerable gap in cancer care forms the basis for the need for sexual healthcare that is accessible and affordable without compromising effective personalized care delivery.

1.1. Prevalence and Severity of Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life

1.1.1. Impact on Physical Wellbeing

Over 50% of cancers diagnosed in Canada are breast and pelvic cancers [5]. Of these cancers, 30% of colorectal, 73% of breast, and 90% of prostate/gynecological cancer survivors experience long-term SD. Additionally, 20% of non-breast/non-pelvic cancer survivors report SD that interferes with their overall quality of life. Ovarian and cervical cancer survivors report hot flashes, low desire, vaginal dryness, vaginal stenosis, atrophy, inflammation, discomfort, and pain during sex [6,7,8,9]. Patients undergoing treatment for prostate and testicular cancer can experience erectile dysfunction (ED), loss of desire, fatigue, hot flashes, and loss of satisfaction [2,9,10,11]. In non-genitourinary cancers, such as head and neck cancers, loss of saliva, disfigurement, and fatigue can all have an impact on sexual health and patient quality of life [12].

1.1.2. Impact on Psychological Wellbeing

Although selected sexual side-effect profiles are short-term, the majority of survivors experience long-term sexual health concerns. The chronicity of the physical impact leaves patients vulnerable to psychological morbidity, including distress, depression, anxiety, and loss of self-esteem [13]. During cancer treatment, changes in body shape, scars, and hair loss can cause patients to feel less attractive or desirable and consequently experience less sexual desire themselves [14,15]. For some prostate cancer survivors, ED has been described as stripping them of their identity, sex life, and relationship [16]. Additionally, patients suffering from ED can experience performance anxiety which can interfere with adherence to pro-erectile therapy [17].

1.1.3. Impact on Interpersonal Wellbeing

Patients with SD report reductions in overall relationship intimacy and satisfaction [17]. Physical changes in sexual functioning can cause both male and female cancer survivors to avoid sexual intimacy with their partners. This behavior can lead to decreased relationship satisfaction, which in turn can lead to further sexual dysfunction for the couple [17,18]. In a study of cervical cancer survivors and their partners, many partners described that changes in sexual health after treatment (e.g., vaginal dryness, pain during intercourse, sexual dysfunction) contributed to interpersonal problems and emotional distancing from their patient-partners [15].

1.1.4. Barriers to Sexual Healthcare in Oncology

Despite ongoing research and documentation of the physical, psychological, and interpersonal burden of sexual dysfunction, the provision of sexual healthcare in oncology is uniformly inadequate. Research demonstrates that this gap in care can be attributed to three main factors: (1) Poor Accessibility and Access Disparity—access to care is a challenge given that most cancer centers do not offer sufficient sexual healthcare [3,4]. Poor accessibility is further exacerbated by geographical disparity. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural oncology settings often receive less funding to support specialized services, such as sexual healthcare [19]; (2) Lack of Oncologist Training and Time to Provide Sexual Healthcare—lack of communication between clinician and patient has been consistently identified as a barrier to accessing sexual healthcare [20]. The main barriers to practitioner-initiated conversations about sexual healthcare include a lack of appropriate training, resources, and time [4]. Additionally, oncologists report feeling even less prepared for understanding sociocultural factors affecting sexual health and knowing the unique care needs of LGBTQ2+ cancer survivors [21]; and (3) Lack of Financial Resources—for many reasons, including an aging population, healthcare systems have experienced significant financial strain over the past two decades [22], and the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to even more fiscal pressure on hospitals worldwide [23,24]. As hospital budgets become increasingly inadequate for the provision of basic care, specialized sexual healthcare is less likely to receive initial and sustainable funding.

In summary, the severity of the impact of sexual dysfunction combined with the complexity of barriers to care within an already financially strained healthcare system underpins the lack of sexual health clinics in cancer centers worldwide. Consequently, there remains an exigent need for effective, efficient, and inclusive sexual health programming in oncology. This paper describes the newly developed Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (Toronto, Canada) Sexual Health Clinic (in collaboration with NexJ Health Inc.) that utilizes an innovative, hybrid model of integrated in-person and virtual care. The goal of the SHC is to assist patients and their partners in achieving optimal sexual function, satisfaction, and interpersonal intimacy post-cancer treatment. A core value of SHC is to provide equitable, inclusive care in an environment that fosters openness and sensitivity to racial, cultural, sexual, and gender diverse populations.

2. Materials and Methods

Previous Work

In 2009, our team developed the Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic (PCRC), which was made available to all men who consented to a radical prostatectomy at the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Toronto, Canada. The PCRC was a structured, manual-enhanced sexual rehabilitation clinic for prostate cancer survivors and their partners. In 2012, the PCRC was introduced into usual care with a patient “opt-out” option. A PCRC program evaluation revealed significant patient interest and uptake [25]. In comparison to patient experience before the implementation of the PCRC, PCRC patients reported improved biomedical and psychosocial outcomes, and exceptional satisfaction scores in care provision [10]. In 2019, the TrueNorth SHAReClinic was introduced as an alternative option to the PCRC. The TrueNorth SHAReClinic is a facilitated virtual clinic containing over 200 pages of expert-informed content, 22 videos (physician, patient, and partner), and several specialized, virtual self-management features. Evaluation of the TrueNorth SHAReClinic revealed 71% patient engagement at 1-year follow-up, substantial patient activity on the platform, and non-inferior sexual health outcomes compared to “best practice” and the scientific literature [26]. Combined, the PCRC and the TrueNorth SHAReClinic have provided treatment to over 2500 patients. Currently, the TrueNorth SHAReClinic is embedded as usual care in five leading Canadian cancer centers.

Overall, the results from the PCRC and the TrueNorth SHAReClinic emphasize the importance of sexual healthcare and support the expansion of innovative models of sexual healthcare to other oncology populations. Accordingly, the Princess Margaret Sexual Health Clinic (SHC) evolved from a fusion of the Prostate Cancer (Sexual) Rehabilitation Clinic at Princess Margaret (in-person) and the Movember TrueNorth Sexual Health and Rehabilitation e-Clinic (virtual) for prostate cancer patients. The resultant hybrid care model was adapted to include six additional cancer sites (cervical, ovarian, testicular, bladder, kidney, and head and neck) with plans to expand to all cancer sites. The SHC is theoretically founded on a biopsychosocial framework and emphasizes interdisciplinary intervention teams, active participation by the partner, and a broad-spectrum medical, psychological, and interpersonal approach. Clinical and patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures are serially collected via the SHC virtual portal to assess quality assurance and effectiveness. The launch of the SHC utilized a Hybrid Type 3 implementation methodology to ensure seamless integration into the patient workflow across the cancer sites of a high-volume cancer center.

3. Results

3.1. The Sexual Health Clinic (SHC)

3.1.1. Patient Population

The SHC provides care to patients (and partners) with prostate, testicular, cervical, ovarian, bladder, kidney, and head and neck cancers. These cancer sites were chosen for their diversity in age, biological sex, type of sexual dysfunction, and pelvic and non-pelvic concerns. Successful treatment across these diverse presentations will allow for easy expansion to all cancers in the future.

3.1.2. Clinical Visiting Program

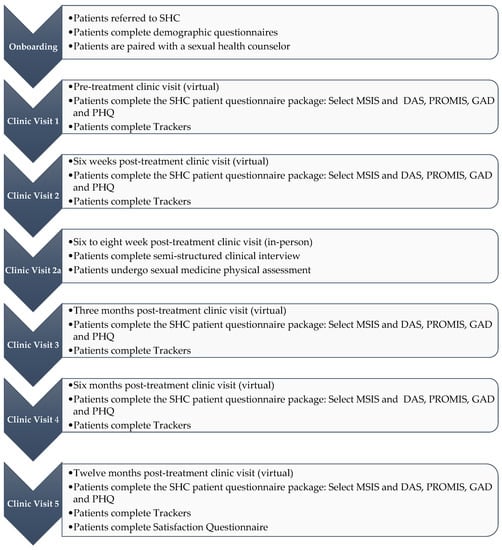

The SHC visit schedule includes a virtual clinic visit at pre-treatment (T1) and 6 weeks (T2), 3 months (T3), 6 months (T4), and 12 months (T5) post-cancer treatment. The virtual visits are facilitated by highly trained sexual health counselors (SCs) who provide education, support, and guidance via SHC platform-based asynchronous and synchronous chat, telephone, and/or videoconference. At 6–10 weeks post-cancer treatment (T2a), patients/couples also attend an in-person clinic where they are seen by an interdisciplinary team for sexual medicine assessment and prescription (note: additional in-person follow-up visits are provided as needed). The visit type and schedule are designed to maximize upfront patient education (T1), normalize treatment impact (T2), allow for early medical examination and prescription of sexual medicine (T2a), and provide long-term sexual rehabilitation (T3, T4, T5) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SHC Visit Schedule.

3.1.3. Assessment

The SHC patient sexual health assessment is a three-step process comprising of a semi-structured clinical interview, completion of a standardized questionnaire package, and a physical exam. The semi-structured interview is performed by SCs during the patient’s first in-person visit (T2a). The comprehensive clinical interview documents the patient’s (1) medical and psychiatric history, cancer type and treatment, gender, and sexual orientation; (2) previous and current use of sexual medicine or devices; (3) concerns regarding sexual desire, arousal, plateau, orgasm, body image, pain, and satisfaction; and (4) concerns regarding relationship satisfaction and intimacy. The SHC patient questionnaire package includes the Miller Social Intimacy Scale (MSIS)—only four items, the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (DAS)—only one item, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS)—Full Profile Sexual Function and Satisfaction, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire. Additionally, patients are prompted to regularly complete sexual functioning trackers (Likert scale 1-low to 10-high) including sexual desire/interest, erection firmness (male), lubrication (female), sexual activity in the last month, sexual satisfaction, intimacy (couple), and body image concerns. The questionnaires are completed by patients at the end of each virtual care visit, while the trackers are completed per patient preference, with a minimum of once per virtual care visit. Finally, during the first in-person visit, if applicable, the patient will undergo a sexual medicine physical assessment. Combined, the SHC assessment is used to guide the development of a personalized biopsychosocial treatment plan.

3.1.4. Intervention

The SHC intervention is theoretically founded on a biopsychosocial framework combined with an interdisciplinary provision of care. The intervention consists of three major components: virtual access to education modules; virtual care facilitation by a sexual health counselor; and in-person clinic visits with an interdisciplinary sexual health team.

3.1.5. Educational Modules

Patient/couple experience is tailored through the assignment of specific education modules based on the patient’s cancer type, treatment type, biological sex, and relationship status (single or coupled). A total of eighty-one multi-modal education modules, inclusive of figures, photos, videos, and animations, were created specific to the physical, psychological, and interpersonal impacts of cancer and its treatment on sexual health (Table 1: Education Module Menu). Additionally, patients can further customize their experience by adding “patient preference” modules to their virtual experience (e.g., Unique Needs of LGBTQ2+). All education modules are founded based on internationally recognized guidelines, empirical research, and expert opinion. Combined with the educational modules, the virtual platform offers access to symptom trackers and goal-setting strategies to empower participant self-management. Finally, the online clinic also features a professionally curated, digital health library including electronic books, relevant leading articles, and videos on sexual health and rehabilitation.

Table 1.

SHC Educational Modules.

Accounting for the seven cancers, the biological sex of the patient, and the cancer treatment options, a total of 32 unique patient streams were determined (e.g., a male bladder cancer surgery patient stream, a female bladder cancer surgery patient stream, a male bladder cancer surgery plus chemotherapy patient stream, etc.). Using the Education Module Menu, education modules were embedded into each of the 32 unique patient streams based on known relevance to a patient’s experience in that particular stream. For example, see Table 2 comparing the stream of a male bladder cancer surgery patient and a testicular cancer surgery patient.

Table 2.

Example of Unique Patient Streams.

3.1.6. Virtual Sexual Health Counselors

In an effort to “humanize the technology” and promote patient engagement [26], the SHC virtual care platform is facilitated by sexual health counselors via chat, telephone, or videoconference. The SHC counselors provide an additional layer of personalization through the provision of psychosexual education/guidance, supportive counseling, and motivational strategies to foster self-management and SHC-treatment adherence. Training for our SHC counselors involves successful completion of the Sexual Health in Cancer Part I and Sex Counselling in Cancer Part II courses offered through the de Sousa Institute (https://www.desouzainstitute.com accessed on 13 January 2023). The SHC counselors must also complete specialized training in virtual-based communication and documentation, and platform-based features designed to enhance participant–counselor interaction (e.g., participant engagement and tracker monitoring). Additionally, the SHC counselors receive applied clinical training through SHC Case Rounds and direct supervisor–counselor shadowing during in-person clinic patient encounters.

3.1.7. Face-to-Face Clinical Visits

Patients/couples attend an in-person clinic where they are seen by an interdisciplinary team inclusive of urologists, psychologists, nurses, and SCs. During their clinic visit, patients undergo both a physical examination for presenting sexual dysfunction and a psychosexual assessment for related psychosocial concerns. Where appropriate, clinic visits can also be used for in-person training in sexual medicine prescription such as intracavernosal injection training or vaginal dilator therapy. As well, the SC can schedule additional in-person follow-ups for patients requiring changes to their sexual medicine regimen, medical examination, and sexual medicine prescription.

3.1.8. Quality Assurance and Research Program

Embedded in the SHC is a quality assurance, improvement, and research program. At the core of this program is the SHC database (SHC-DB), an active database in which PRO data is serially collected, scored, and uploaded directly from the SHC platform. The SHC-DB includes data fields specific to patient demographics, patient engagement (e.g., rates of enrolment, attrition, completion), and clinic evaluation (sexual health questionnaires/trackers). The research program is designed to measure patient engagement, evaluate the effectiveness of SHC, and provide a ‘real-world laboratory’ for conducting biomedical and psychosocial research in sexual medicine.

3.2. SHC Implementation

Implementation of SHC is guided by the Quality Implementation Framework and includes (1) identification of unique implementation factors within host sites, (2) creation of a systematic structure for implementation, (3) allowance for ongoing structure evolution, and (4) development of improvement strategies for future applications. In this regard, our team identified “site champions” for each of the seven cancer sites. The site champions participated in three brainstorming sessions designed to tailor integration of the SHC into patient workflow and clinic protocol. Additional key site group/clinic personnel were also interviewed to further explicate approaches to SHC integration into patient and practitioner experience. In total, 20 interviews were performed, and a pragmatic qualitative analysis of the interview transcripts is currently proceeding. To further enhance the interview data, a clinic-embedded research assistant is also documenting clinic-based enablers and barriers to successful implementation. The SHC will employ known patient-based engagement approaches for online healthcare services including establishing product legitimacy and security, usability testing and enhanced functionality, participant and SC platform training, SC facilitation, information tailoring and guided usage, patient and HCP feedback, and automated reminder features. Combined, this data collection process is helping to inform the evolution of successful SHC-integration strategies that serve to close gaps in sexual healthcare across cancer sites and within patient experience.

4. Discussion

The SHC offers care innovation that has the potential to overcome pervasive barriers in sexual healthcare (such as poor accessibility, financial restraint, and lack of oncologist time and specialized training) without compromising treatment adherence and effectiveness. The SHC employs a virtual dominant in-person less-dominant model of care. This design strategically combines the accessibility and efficiency benefits of digital healthcare with the personalization of face-to-face contact during in-clinic visits. Additionally, SHC utilizes virtual-counsellor facilitation and treatment tailored to maintain engagement and enhance effectiveness.

4.1. SHC and Accessibility

Residents in rural areas face more difficulties accessing health care compared to their urban counterparts [27]. In general, rural residents have direct access to a much smaller number and scope of health services and providers than urban residents [28,29,30]. As a result, patients in rural locations can experience geographical inequities in accessing specialized care. Digital health interventions offer solutions to geographical health disparity via efficient, accessible, and scalable care pathways. Internet penetration in North America is believed to be over 90% [31]. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic stimulated technology expansion and patient acceptability of digital health intervention. The SHC virtual care-dominant approach serves to alleviate geographic disparity concerns through enhanced patient access and reductions in the need for patients to physically attend regular follow-up clinic appointments. Additionally, the scalability of digital health solutions makes SHC particularly well suited for reducing health disparities both within and across countries.

4.2. SHC and Affordability

Digital health interventions are generally considered to be time and cost efficient in comparison to traditional care pathways [32]. In Canada, between 2005 and 2015, innovations in digital health produced approximately CAD 16 billion in efficiencies [33] In 2017, the US FDA published the Digital Health Innovation Action Plan to encourage technology innovation in digital health [34]. Traditional survivorship care, inclusive of sexual health care, relies on in-person, structured visit schedules. In-person clinic visits incur costs to the host institution in the form of space, clinic staff wages, and incidental costs. The SHC utilizes a targeted approach to in-person care such that only patients requiring medical examination or initiation of sexual health medicine are seen in clinic while the majority of follow-up care is virtual. The cost effectiveness of a 1 to 5 ratio of in-person to virtual visits helps to ensure sustainability during times of significant fiscal restraint.

4.3. SHC and Oncologist Training and Time

Although oncologists recognize sexual health as an important part of their patients’ quality of life, they report feeling restricted by lack of training and lack of in-clinic time to adequately treat their patients’ sexual health concerns [31,35,36]. Unfortunately, this can lead to decreased physician–patient communication about the sexual implications of cancer treatment [37]. Given these limitations, it is likely necessary to provide care external to oncology clinics in order to optimally treat patient sexual health concerns. By providing a patient resource for specialized sexual healthcare external to busy oncology clinics, the SHC relieves oncologists from the pressure to provide sexual healthcare during busy clinic periods. Additionally, having the SHC resource available may also serve to increase the likelihood that physicians will inquire about their patients’ sexual health knowing that they can make an appropriate referral.

4.4. SHC and Digital Health Engagement and Effectiveness

Although there are clear accessibility and affordability benefits associated with digital health, high dropout rates and/or poor patient adherence to digital interventions for health-related behaviors can compromise intervention effectiveness [38,39]. Core considerations for successful digital healthcare must include strategies to encourage initial and ongoing patient engagement. The SHC relies on engagement strategies that were determined to be successful in the TrueNorth SHAReClinic [25]. Specifically, the SHC relies on digital health facilitation, via virtual sexual health counselors, as a key feature in achieving engagement. By enhancing engagement, the SHC-care model allows for increased treatment “dose” and improved effectiveness. Similarly, the SHC provides for treatment tailoring [27,30] through obtaining relevant patient-specific variables that are entered into digital algorithms to organize information and management strategies specific to patient experience. Tailoring is further augmented by guiding patient experience using structured visits and care pathways [40]. Finally, regular and ongoing patient-reported symptom trackers are used to support self-management as an integral part of the SHC-intervention protocol. By targeting patients’ physical, psychological, and relational sexual health concerns, the SHC avoids the pitfall of a one-size-fits-all approach that is unlikely to be effective given the breadth and complexity of sexual dysfunction in oncology.

5. Conclusions

Hybrid digital-inperson healthcare models of care can provide increased access/reach, affordability, tailoring of care, cost-effectiveness, and scalability. The SHC is specifically designed to be a transferable, stand-alone clinic which can be efficiently and effectively shared with cancer centres and other institutions providing care to cancer patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., S.P., G.Y., L.J. and D.E.; design, A.M. and S.G.; methodology, A.M. and S.G.; software, G.Y.; investigation, A.M., S.G., T.I., E.S., S.P., G.Y., L.J. and D.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.; writing—review and editing, S.G., T.I., E.S., S.P., L.J. and D.E.; visualization, A.M. and S.G.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, S.G.; funding acquisition, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The SHC is funded exclusively by The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation. PMHF#886359001213.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. Please note that Gideon Yang is an employee of NexJ Health, the platform provider for the SHC. He has no relevant financial conflict of interest given that the SHC is fully owned by The Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and funded by The Princess Margaret Cancer Foundation.

References

- Barbera, L.; Zwaal, C.; Elterman, D.; McPherson, K.; Wolfman, W.; Katz, A.; Matthew, A. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer guideline development group. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bober, S.L.; Varela, V.S. Sexuality in Adult Cancer Survivors: Challenges and Intervention. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 3712–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, A.; Agrawal, L.S.; Sirohi, B. Sexuality After Cancer as an Unmet Need: Addressing Disparities, Achieving Equality. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2022, 42, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krouwel, E.M.; Albers, L.F.; Nicolai, M.P.J.; Putter, H.; Osanto, S.; Pelger, R.C.M.; Elzevier, H.W. Discussing Sexual Health in the Medical Oncologist’s Practice: Exploring Current Practice and Challenges. J. Cancer Educ. 2019, 35, 1072–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory in collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society, Statistics Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Cancer Statistics: A 2022 Special Report on Cancer Prevalence. Canadian Cancer Society. 2022. Available online: https://cancer.ca/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2022-EN (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Bessa, A.; Martin, R.; Häggström, C.; Enting, D.; Amery, S.; Khan, M.S.; Cahill, F.; Wylie, H.; Broadhead, S.; Chatterton, K.; et al. Unmet needs in sexual health in bladder cancer patients: A systematic review of the evidence. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Pup, L. Management of vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in estrogen sensitive cancer patients. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2012, 28, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavraka, C.; Ford, A.; Ghaem-Maghami, S.; Crook, T.; Agarwal, R.; Gabra, H.; Blagden, S. A study of symptoms described by ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 125, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goossens-Laan, C.A.; Kil, P.J.M.; Bosch, J.L.H.R.; De Vries, J. Pre-diagnosis quality of life (QoL) in patients with hematuria: Comparison of bladder cancer with other causes. Qual. Life Res. 2012, 22, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, A.; Lutzky-Cohen, N.; Jamnicky, L.; Currie, K.; Gentile, A.; Mina, D.S.; Fleshner, N.; Finelli, A.; Hamilton, R.; Kulkarni, G.; et al. The Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation Clinic: A Biopsychosocial Clinic for Sexual Dysfunction after Radical Prostatectomy. Curr. Oncol. 2018, 25, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, I.D.; Wilson, J.; Aslet, P.; Baxter, A.B.; Birtle, A.; Challacombe, B.; Coe, J.; Grover, L.; Payne, H.; Russell, S.; et al. Development of UK guidance on the management of erectile dysfunction resulting from radical radiotherapy and androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2014, 69, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, C.; Fullarton, M.; Parkinson, E.; O’Brien, K.; Jackson, S.; Lowe, D.; Rogers, S. Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schover, L.R.; van der Kaaij, M.; van Dorst, E.; Creutzberg, C.; Huyghe, E.; Kiserud, C.E. Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. Eur. J. Cancer Suppl. 2014, 12, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katz, A.; Dizon, D.S. Sexuality After Cancer: A Model for Male Survivors. J. Sex. Med. 2016, 13, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeer, W.M.; Bakker, R.M.; Kenter, G.G.; Stiggelbout, A.; Ter Kuile, M.M. Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support. Care Cancer 2015, 24, 1679–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhour, B.G.; Clark, J.A.; Inui, T.S.; Silliman, R.A.; Talcott, J.A. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, S.; Mulhall, J.; Nelson, C.; Kelvin, J.; Dickler, M.; Carter, J. Sexual and Reproductive Health in Cancer Survivors. Semin. Oncol. 2013, 40, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmann, D. Emotional and sexual health in cancer. Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2016, 10, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanow, R. Building on Values: Report of the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada. 2002. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.686360/publication.html (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Flynn, K.E.; Reese, J.B.; Jeffery, D.D.; Abernethy, A.P.; Lin, L.; Shelby, R.A.; Porter, L.S.; Dombeck, C.B.; Weinfurt, K.P. Patient experiences with communication about sex during and after treatment for cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2011, 21, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.; Handy, A.B.; Kwan, W.; Oliffe, J.L.; Brotto, L.A.; Wassersug, R.J.; Dowsett, G.W. Impact of Prostate Cancer Treatment on the Sexual Quality of Life for Men-Who-Have-Sex-with-Men. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2378–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaropoulos, L.; Goranitis, I. Health care financing and the sustainability of health systems. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. The financial strain placed on America’s hospitals in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2021, 45, 530–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, L.B.; Mehrotra, A.; Landon, B.E. COVID-19 and the Upcoming Financial Crisis in Health Care. NEJM Catal. 2020, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, A.; Jamnicky, L.; Currie, K.; Gentile, A.; Trachtenberg, J.; Alibhai, S.; Finelli, A.; Fleshner, N.; Yang, G.; Osqui, L.; et al. 320 Prostate Cancer Rehabilitation: Outcomes of a Sexual Health Clinic. J. Sex. Med. 2018, 15, S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, A.G.; Trachtenberg, L.J.; Yang, Z.G.; Robinson, J.; Petrella, A.; McLeod, D.; Walker, L.; Wassersug, R.; Elliott, S.; Ellis, J.; et al. An online Sexual Health and Rehabilitation eClinic (TrueNTH SHAReClinic) for prostate cancer patients: A feasibility study. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 30, 1253–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulley, G.E.; Leroy, T.; Bernetière, C.; Paquienseguy, F.; Desfriches-Doria, O.; Préau, M. Digital health interventions to help living with cancer: A systematic review of participants’ engagement and psychosocial effects. Psycho-Oncol. 2018, 27, 2677–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Peña-Purcell, N.C.; Ory, M.G. Outcomes of online support and resources for cancer survivors: A systematic literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2012, 86, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, C.C.; Finlay, A.; McIntosh, M.; Siddiquee, S.; Short, C.E. A systematic review of the feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy of online supportive care interventions targeting men with a history of prostate cancer. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykin, Y.; Thekdi, S.M.; Shumay, D.M.; Muñoz, R.F.; Riba, M.; Dunn, L.B. Internet interventions for improving psychological well-being in psycho-oncology: Review and recommendations. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 21, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miniwatts Marketing Group. Internet World Stats. 2022. Available online: https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats14.htm (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Iribarren, S.J.; Cato, K.; Falzon, L.; Stone, P.W. What is the economic evidence for mHealth? A systematic review of economic evaluations of mHealth solutions. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghiu, B.; Hagens, S. Cumulative Benefits of Digital Health Investments in Canada. eTELEMED 2017, 9, 69–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Health Innovation Action Plan. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/106331/download (accessed on 9 February 2023).

- Ananth, H.; Jones, L.; King, M.; Tookman, A. The impact of cancer on sexual function: A controlled study. Palliat. Med. 2003, 17, 202–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Yardley, L.; West, R.; Patrick, K.; Greaves, F. Developing and Evaluating Digital Interventions to Promote Behavior Change in Health and Health Care: Recommendations Resulting From an International Workshop. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althof, S.E.; Rosen, R.C.; Perelman, M.A.; Rubio-Aurioles, E. Standard Operating Procedures for Taking a Sexual History. J. Sex. Med. 2013, 10, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.S.; Kim, H.-K.; Park, S.M.; Kim, J.-H. Online-based interventions for sexual health among individuals with cancer: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelders, S.M.; Kok, R.; Ossebaard, H.C.; Van Gemert-Pijnen, J.E. Persuasive System Design Does Matter: A Systematic Review of Adherence to Web-based Interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012, 14, e152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y.H.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, Y.-W.; Park, S.Y.; Lee, E.S.; Noh, D.-Y.; Kim, S.; Oh, J.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Chung, K.-W.; et al. Web-Based Tailored Education Program for Disease-Free Cancer Survivors With Cancer-Related Fatigue: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1296–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).