Highlights

Public health relevance–How does this work relate to a public issue?

- Negative attitudes toward mental health hinder help-seeking in Nepal.

- Cultural factors such as shame and family honor influence public mental health perceptions.

Public health significance–Why is this work of significance to public health?

- Provides a validated tool to measure mental health attitudes in Nepal.

- Identifies culturally specific dimensions of stigma relevant to collectivist societies.

Public health implications–What are the key implications for practitioners, policy makers, and researchers?

- Can guide culturally tailored stigma-reduction programs and mental health interventions.

- Useful for monitoring public attitudes and evaluating mental health policies in Nepal.

Abstract

(1) Background: Negative attitudes toward mental health problems remain a barrier for help-seeking, especially in collectivist, lower-middle-income countries like Nepal. While the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (ATMHPS) has been used globally, it has not been formally validated for Nepalese populations. This study aimed to culturally adapt and psychometrically validate a concise Nepalese version of the scale. (2) Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional study and recruited participants through an opportunity sampling method. We developed the Nepalese Short Version of the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (N-SATMHPS) using Dataset 1 (n = 384) and validated it with Dataset 2 (n = 803). Items were selected based on internal consistency indices. Fourteen items showing the strongest reliability were retained from the original seven subscales. A confirmatory factor analysis and internal consistency testing were used to assess psychometric properties. (3) Results: The N-SATMHPS showed a strong internal consistency (α = 0.74–0.92) and excellent model fit (χ2/df = 1.92, CFI = 0.982, TLI = 0.970, RMSEA = 0.049, SRMR = 0.026). Correlations with the full version ranged from r = 0.79 to 0.96. Discriminant validity with Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire—Young Adults (MHLQ-YA) showed weak but significant correlations, confirming construct distinction. (4) Conclusions: The scale captured key Nepalese cultural constructs, such as shame and family honor. It also aligned with collectivist cultural expectations. The N-SATMHPS demonstrates strong psychometric performance and cultural relevance. It is suitable for research and intervention work aimed at reducing stigma and improving mental health in Nepal.

1. Introduction

Negative attitudes toward mental health problems (ATMHP), often referred to as mental health stigma, remain a major barrier to seeking psychological support. This challenge is especially notable in low- and middle-income countries [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Negative attitudes are common even among caregivers and emerging medical professionals [10,11,12,13,14]. Despite growing awareness, mental illness continues to be perceived through a lens of shame, fear, and social exclusion, often rooted in cultural beliefs [15,16]. Such negative attitudes are compounded by societal norms that associate mental health issues with personal weakness or spiritual failings, leading to the discrimination and marginalization of affected individuals [17,18,19,20]. Therefore, measuring ATMHP is crucial, as it significantly contributes to stigma reduction and supports better mental health care. This is especially important in Nepal, a lower-middle-income country where mental health-related shame remains pervasive [2,5,6,7,8,21,22,23].

1.1. Measuring ATMHP

There are well-developed measurement scales to measure the attitudes of community members towards mental health issues. “Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems (ATMHP)” developed by Gilbert et al. (2007) offers a comprehensive framework for assessing such attitudes, encompassing dimensions like internal and external shame and reflected shame [15]. In a Portuguese validation study of the ATMHP, the original model showed a poor fit in a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), but an alternative model with an added factor demonstrated a good model fit. A further analysis confirmed that the revised version had good psychometric properties, supporting its suitability for assessing attitudes toward mental illness in Portuguese-speaking populations [24].

Later studies developed a 14-item short version of the ATMHPS (SATMHPS). It showed good internal consistency and replicated the original seven-factor structure, making it a reliable tool for assessing attitudes and shame toward mental health problems among UK university students [25]. Similarly, the Japanese short version of the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (J-SATMHPS) demonstrated a reliable seven-factor structure and cultural applicability. It highlighted differences between the UK and Japan in external and internal mental health-related shame [26]. The scale has already been used for measuring attitudes of college students in Nepal; however, the applicability of this scale in the Nepalese context has not been thoroughly examined [6].

1.2. Conceptual Framework of ATMHP Scale

The development of the ATMHP scale was grounded in a rich body of cross-cultural and psychosocial research examining how cultural norms shape perceptions of mental health, shame, and stigma. Culture acts as a framework through which individuals interpret their experiences, including attitudes toward mental illness [23,27,28]. Studies have emphasized obvious differences between Eastern and Western societies regarding the conceptualization of mental health, expectations of coping behaviors, and engagement with mental health services [29,30,31]. Research with British South Asian women underscored the role of shame—particularly tied to cultural values such as izzat (family honor)—in deterring help-seeking and promoting silence around psychological distress [32,33,34]. These findings informed the scale’s theoretical basis, incorporating dimensions of external shame (fear of social judgment), Internal Shame (self-criticism), and reflected shame (concern over bringing dishonor to one’s family) [35,36,37]. These constructs provide a culturally sensitive framework for assessing attitudes toward mental health.

1.3. Study Gap

While studies have utilized the ATMHP scale in various cultural settings without formal validation [6,38,39,40], formal validation has been performed in Portugal [24] and Japan [26]. Additionally, it has been used in cross-cultural studies, comparing Arabs, South Asians, and others living in the United Arab Emirates [41]; British Caucasians and Arabians [42]; and British Asians and non-Asians [15]. A shorter Japanese version of the ATMHPS (J-SATMHPS) has been developed and validated in a collectivistic culture [26]; however, there are no such validation studies in the South Asian sub-continent, including Nepal. Although Poudel et al. (2024) reported a high internal consistency (α = 0.94) and strong convergent validity (with Pearson correlations ranging from 0.66 to 0.86), the study was conducted without a proper validation of the tool, making the findings questionable [6]. Without such validation, the applicability and accuracy of the scale for capturing culturally embedded attitudes—such as those influenced by shame, family honor, and spiritual beliefs—remain uncertain. Though Nepal is a culturally collectivistic society similar to Japan, it also differs from the Japanese cultural context due to a complex interplay of cultural factors. Therefore, it is essential to develop and validate a shorter Nepalese version of the ATMHPS (N-SATMHPS).

1.4. Study Aim

This study aims to validate the ATMHP scale in the cross-cultural context of Nepal, ensuring its reliability and relevance for assessing attitudes toward mental health problems among Nepali populations. By doing so, it seeks to provide a culturally sensitive tool that can inform interventions aimed at reducing stigma and promoting mental well-being in Nepal.

This study can contribute to the Nepalese mental health field by validating the ATMHP scale for use in Nepal. It ensures the tool’s cultural relevance and reliability in assessing negative attitudes rooted in societal shame, stigma, and family honor, which are prominent in Nepalese culture. By offering a validated, context-sensitive instrument, this study lays the groundwork for more effective stigma reduction interventions and evidence-based mental health strategies tailored to the Nepalese population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

Two different cross-sectional survey designs were utilized simultaneously to develop the Nepalese Short Version of the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (N-SATMHPS) File S1; to evaluate the structural validity of the N-SATMHPS; and to assess the discriminant validity between the N-SATMHPS and Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire—Young Adult (MHLQ–YA; Dias et al., 2018) [43], including their respective dimensions. Dataset 1, from a previous study by Poudel et al. (2024) [6], was utilized to develop the scale, while Dataset 2 was used to evaluate the structure in a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA).

2.2. Participants and Procedures

For Dataset 1, the required sample size was determined using Cochran’s formula for a population with an unknown proportion: n0 = (Z2pq)/e2, where n0 is the sample size, Z is the z-score for the desired confidence level, p is the estimated proportion of the population, q is 1 − p, and e is the desired level of precision (i.e., marginal error) [44]. Assuming a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), a proportion estimate of 0.5 (p = 0.5, q = 0.5), and a 5% margin of error (e = 0.05), the minimum required sample size was calculated as ((1.96)2 (0.5) (0.5))/(0.05)2 = 385 [44]. Based on this, a total of 384 participants aged 18 to 24 years were included (1 was excluded due to sensitivity) from the Chitwan and Kathmandu districts (i.e., Dataset 1). This sample, also used in a previous study [6], was used to develop the tool in the current study. For Dataset 2, we included 803 participants from across Nepal, encompassing both students and individuals from the general population from very remote areas such as Karnali in the west and Jhapa in the east, including Kathmandu and Chitwan, which were used for CFA. The sample comprised diverse demographic characteristics, including various demographic components such as gender and religious and ethnic groups within the country.

Opportunity sampling, a non-probability method suitable for accessing readily available populations, was employed. College students were included because they are a key group for understanding and shaping societal attitudes toward mental health [45,46], and general individuals were included for broader representation.

2.3. Instruments

Two standardized self-report instruments were employed via online Google forms and paper-based questionnaires: the ATMHP scale [15] and MHLQ-YA [43]. The tools were translated into Nepali following rigorous cross-cultural adaptation procedures to minimize language-related bias. The forward translation was performed by a professional bilingual English language teacher, and the back translation was conducted by another bilingual language English teacher with translation experience. The translated version was then evaluated by five additional English language teachers to identify linguistic ambiguities. A psychology lecturer with expertise in mental health reviewed the translation for accuracy and cultural relevance, and a Nepali language expert checked the spelling, punctuation, and grammar. These steps ensured both linguistic and conceptual equivalence in the adapted tools.

Google forms were distributed via platforms such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram. For the paper-based method, participants were approached directly on campuses. The online survey was administered between 26 June and 24 October 2021, while the paper–pencil survey was conducted from 27 September to 4 October 2021.

2.4. Ethical Consideration

Ethical approval for the first study (Dataset 1, n = 384) was obtained from the Nepal Health Research Council under Ethics Review Board protocol registration no. 309/2021 (ref. no. 3543, approval date: 15 June 2021) [6], and for the second study (Dataset 2, n = 803), we obtained approval from college authorities according to their rules and regulations; college–1 (reference no. 151/2077/78; date: 20 June 2021), college–2 (reference no. 105/077/078; date: 22 June 2021); college–3 (reference no. 423; date: 1 October 2021); college–4 (reference no. 433; 4 October 2021), and college–5 (Dispatch no. 544; 4 October 2021). Informed consent was obtained after participants were briefed on confidentiality, data security, and their right to withdraw at any time. This study adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participant rights and autonomy throughout [47]. Licensed and free software tools (MS Office—16, Stata version 18, semdiag and Google Forms/Sheets) were used for data collection, analysis, the path diagram creation, and manuscript preparation [48]. Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

2.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata 18.0, following the methods of a similar UK study [25], and the path diagram was created using semdiag [48]. Dataset 1 (n = 384) was used for item reduction, and Dataset 2 (n = 803) was used for validation. Outliers in Dataset 1 were removed by visually inspecting Total Scores; perfect scores (105) were excluded to improve sensitivity. Descriptive statistics summarized demographic data. Pearson correlations identified two items with the highest inter-item correlations within each of the seven ATMHPS subscales, producing a 14-item N-SATMHPS. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, and item–total correlations evaluated the item performance. Convergent validity was tested by correlating subscale totals between the original and shortened scales. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess model fit using χ2/df, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR as fit indices. Dataset 2 was used to replicate the procedures and confirm the reliability and structural validity of the N-SATMHPS. Based on established guidelines for structural equation modeling, we considered a model acceptable if the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) were ≥0.90, and if the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were ≤0.08 [49].

The 14 items were selected from the initial item pool based on their high inter-item correlations, ensuring that retained items were strongly related to each other and represented the core construct. In addition to correlation values, the theoretical relevance and coverage of the construct dimensions guided the selection. Exploratory factor analysis or item response theory methods were not applied at this stage, as the aim was a preliminary selection of items based on both statistical strength and conceptual considerations.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset Overview

We developed the N-SATMHPS using Dataset 1 (n = 384) and validated it with Dataset 2 (n = 803). Each dataset contained the full ATMHPS items, labeled atmhp1 to atmhp35. One response in Dataset 1 with a perfect Total Score (105 points) was excluded, as it may reflect an extreme response style such as acquiescence bias or social desirability rather than genuine attitudes [50]. This exclusion followed best practices in psychometric research to improve the sensitivity and interpretability of scale performance. The analytical methods were based on prior work by Kotera et al. (2023) [25], and analyses were conducted using Stata 18.0. A path diagram was generated using the semdiag package [48].

3.2. Confirmation of Background Factors

Next, we examined the background factors of the participants in each dataset. Demographic characteristics differed between the two datasets. Participants in Dataset 1 were younger, predominantly female, and mostly students. In contrast, Dataset 2 included a broader age range with more occupational diversity (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of participants (Dataset 1, n = 384).

Table 2.

Background characteristics of participants (Dataset 2, n = 803).

3.3. Extraction of Two Questions for Correlation Analysis for N-SATMHPS

A correlation analysis was conducted on the group in Dataset 1 (Table 3). We evaluated the correlations between the questions within each subscale and selected the two items with the highest correlation.

Table 3.

Correlation between items in each factor of the ATMHPS for Dataset 1.

3.4. The Performance Evaluation of the Developed N-SATMHPS

Next, we evaluated the correlation (item–total correlations) and p-values of the selected questions and each subscale. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Correlation coefficients and p-values of the N-SATMHPS.

Unlike the benchmark validation study [25], the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.59 to 0.83, showing low values for some items. Next, we calculated the average, standard deviation, and α for each item (scored 0–3) for each subscale (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of mean, SD, and correlation between full ATMHP and N-SATMHPS.

The alpha value (α) had a reliability of 0.79–0.92 in the ATMHPS and 0.71–0.89 in the N-SATMHPS, which was not as reliable as the reference paper. The table below shows the correlation of the sums of the subscales for the ATMHPS and N-SATMHPS (Table 6).

Table 6.

Correlation between full ATMHP and N-SATMHPS.

Except for the Family-Reflected Shame, a strong correlation was obtained.

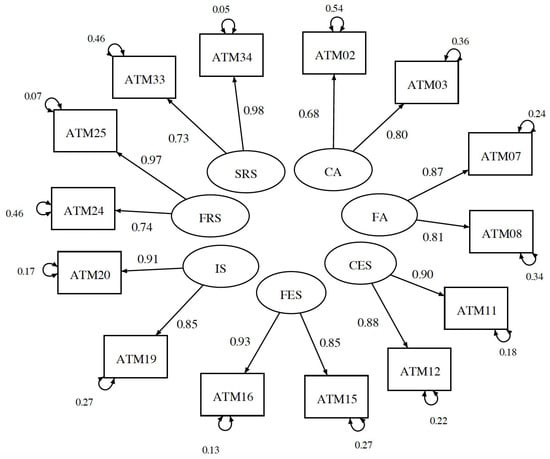

Finally, a path diagram was created, and the goodness of fit of the model was evaluated (Figure A1 in Appendix A).

The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) indicated a good model fit, with all fit indices falling within acceptable ranges. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) was 107.32/56 = 1.92, suggesting an adequate fit. The comparative fit index (CFI) was 0.98, and the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) was 0.97, both exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.90. Additionally, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.049, and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was 0.026, both indicating a good fit according to conventional guidelines.

3.5. Validation

We developed and validated the N-SATMHPS using Dataset 1 and Dataset 2, respectively. First, we confirmed the internal consistency. The results are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of reliability scores (α) between full ATMHP and N-SATMHPS.

The results showed that the alpha value for the ATMHPS was 0.84–0.94, and for the N-SATMHPS it was 0.74–0.92, indicating that the coefficients for the shortened versions were generally lower than those of the current versions. However, the alpha values themselves were within an acceptable range.

Finally, as in the development stage, the following table confirms the correlation of the sums of each subscale of the N-SATMHPS (Table 8).

Table 8.

Correlations of factors in N-SATMHPS.

The results showed that the correlation coefficients were generally higher than those from the development stage.

3.6. Discriminant Validity

Several significant but weak correlations were observed between the MHLQ-YA factors and N-SATMHPS subscales, supporting discriminant validity. Notably, MHLQ-YA’s Factor 1 was positively correlated with the N-SATMHPS’s Community Attitudes and Total Score. Factor 2 showed negative correlations with Family Attitudes, Family External Shame, Self-Reflected Shame, and the Total Score. Factor 3 was negatively associated with Family Attitudes, Family External Shame, Internal Shame, and the Total Score. No significant associations emerged for Factor 4 or the MHLQ-YA Total Score. The details are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Discriminant validity between N-SATMHPS and MHLQ-YA.

4. Discussion

The development and validation of the N-SATMHPS represent a significant advancement in culturally sensitive mental health assessment tools. We aimed to create a concise yet reliable instrument to measure attitudes towards mental health problems within the Nepali context, ensuring both psychometric robustness and practical applicability.

4.1. Model Fit

The N-SATMHPS demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency across subscales. While slightly lower than the reliability scores of the full ATMHPS and the short-form J-SATMHPS, the values remain within acceptable thresholds for psychological tools, supporting the scale’s reliability [15,26]. The CFA supported the seven-factor structure of the N-SATMHPS, with fit indices indicating a good model fit. These findings are consistent with the CFA results for the SATMHPS and J-SATMHPS, both of which demonstrated strong model fits [25,26].

4.2. Correlation Analyses

The N-SATMHPS subscales exhibited strong correlations with their corresponding subscales in the full ATMHPS, ranging from 0.79 to 0.96. This consistency underscores the N-SATMHPS’s capability to effectively capture the constructs measured by the full scale [15].

The discriminant validity of the N-SATMHPS was assessed through correlations with the MHLQ-YA [43]. Significant but weak correlations were observed between certain N-SATMHPS subscales and MHLQ-YA factors, suggesting that while related, the constructs measured by the two instruments are distinct. For instance, MHLQ-YA’s Factor 1 (Knowledge of Mental Health Problems) showed a positive correlation with the Community Attitudes subscale of the N-SATMHPS, suggesting that greater knowledge of mental health increases negative Community Attitudes, whereas Factor 2 (Erroneous Beliefs/Stereotypes) exhibited negative correlations with several N-SATMHPS subscales, indicating that higher awareness of Erroneous Beliefs/Stereotypes promotes positive attitudes. Studies have found that mental health literacy reduces mental health shame [51,52,53]. However, Poudel et al. (2024) have found no relation between mental health knowledge and mental health shame [6].

4.3. Cultural Considerations and Implications

The adaptation of the ATMHPS into the Nepali context required careful consideration of the cultural nuances related to mental health stigma and shame. The strong internal consistency and model fit indices suggest that the N-SATMHPS effectively captures culturally relevant attitudes towards mental health problems in Nepal.

The successful cultural adaptation of the ATMHPS into the Nepalese context underscores the scale’s utility in collectivist societies, where community and family perceptions deeply influence individual behavior [54]. Unlike Western cultures, which generally prioritize individual autonomy [55], Nepalese society often views mental health through a communal lens, where family honor (izzat) and societal expectations play a critical role [32]. Concepts such as reflected shame (i.e., feeling disgrace on behalf of the family) and external shame (i.e., fear of judgment by the community) are embedded in everyday attitudes. In our study, these constructs remained relevant and strongly endorsed, validating the theoretical structure of the N-SATMHPS. Moreover, despite some subcultural diversity in Nepal, our results showed consistency across gender, caste, and religious affiliations, suggesting that the scale captures common cultural attitudes rather than group-specific perspectives. The validation of the N-SATMHPS contributes not only to Nepalese mental health research but also offers a model for culturally contextualizing global tools in diverse settings.

Assessing mental health shame is particularly valuable because it can directly in-form interventions that encourage help-seeking and self-compassion [56]. High levels of shame often prevent individuals from accessing mental health services due to fear of judgment or loss of social standing [57]. By identifying these attitudes, targeted psychoeducation and compassion-focused approaches can be developed to reduce shame, normalize help-seeking, and promote a more accepting self-view. Evidence suggests that less shame and greater self-compassion are linked to a greater willingness to seek professional support and improved mental health outcomes [58]. Therefore, the N-SATMHPS not only measures attitudes but also offers practical insights for designing culturally appropriate mental health interventions in Nepal.

4.4. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, both datasets were obtained through opportunity sampling, with a predominance of college students. This may limit the generalizability of the findings to the wider Nepalese population, particularly rural residents and non-educated groups, who may hold different attitudes toward mental health [59]. Second, although the translation and cross-cultural adaptation process ensured linguistic and conceptual equivalence, this study did not collect qualitative feedback from participants or experts to examine how constructs such as reflected shame or izzat are locally interpreted. Third, this study did not assess the test–retest reliability or convergent validity with other stigma or shame measures, limiting insights into the scale’s stability and its relationship with related constructs [60,61]. Fourth, the reliance on self-report measures introduces potential response biases, especially given the sensitive nature of mental health stigma [26]. Fifth, no qualitative methods were used, which could have deepened the understanding of how shame and stigma are experienced in context. Finally, the clinical and applied utility of the N-SATMHPS was not evaluated. Future studies should address these remaining aspects to further establish the scale’s psychometric robustness and utility.

5. Conclusions

The N-SATMHPS emerges as a reliable and valid instrument for assessing attitudes towards mental health problems in Nepal [61]. Its brevity and cultural relevance make it a practical tool for both research and clinical settings. By facilitating the assessment of mental health attitudes, the N-SATMHPS can contribute to the development of targeted interventions aimed at reducing stigma and promoting mental well-being within the Nepali context.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph22121884/s1: File S1: N-SATMHPS Nepalese Shorter Version of Attitudes towards Mental Health Problems Scale.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.B.P.; methodology, T.Y.; software, T.Y.; validation, D.B.P., T.Y., R.C., and Y.K.; formal analysis, T.Y.; investigation, D.B.P.; resources, D.B.P. and Y.K.; data curation, D.B.P.; writing—original draft preparation, D.B.P.; writing—review and editing, D.B.P., T.Y., R.C., and Y.K.; visualization, D.B.P. and T.Y.; supervision, Y.K.; project administration, D.B.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) (ERB protocol no. 309/2021, ref. no. 3543, approval date: 15 June 2021) for Dataset 1 [6]; and Dataset 2 was approved by an internal board of different colleges: college–1 (reference no. 151/2077/78; date: 20 June 2021), college–2 (reference no. 105/077/078; date: 22 June 2021); college–3 (reference no. 423; date: 1 October 2021); college–4 (reference no. 433; 4 October 2021), and college–5 (Dispatch no. 544; 4 October 2021). It followed the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participants’ rights were protected throughout the research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Certain data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the colleges’ authorities and participants from the colleges involved in this study for their support and participation. We also acknowledge the Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC) for granting ethical approval for Dataset 1. We acknowledge all the authors cited in this article for their contributions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (GPT-5, OpenAI, 2025) for the purposes of language refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATMHP | Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| df | Degrees of Freedom |

| J-SATMHPS | Japanese Shorter Version of Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale |

| MHLQ–YA | Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire—Young Adult |

| N-SATMHPS | Nepalese Shorter Version of Attitudes towards Mental Health Problems Scale |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SATMHPS | Shorter Version of the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

N-SATMHPS items and their relation to factors.

References

- Corrigan, P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurung, D.; Poudyal, A.; Wang, Y.L.; Neupane, M.; Bhattarai, K.; Wahid, S.S.; Aryal, S.; Heim, E.; Gronholm, P.; Thornicroft, G.; et al. Stigma against mental health disorders in Nepal conceptualised with a “what matters most” framework: A scoping review. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, C.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Thornicroft, G. Mental illness stigma, help seeking, and public health programs. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acharya, S. Exploring Student’s Attitudes towards Mental Health Problems in Chitwan, Nepal. Int. Res. J. MMC 2025, 6, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, S.; Panthee, B. Prevalence of self-stigma and its association with self-esteem among psychiatric patients in a Nepalese teaching hospital: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, D.B.; Sharif, L.S.; Acharya, S.; Mahsoon, A.; Sharif, K.; Wright, R. Mental health literacy and attitudes towards mental health problems among college students, Nepal. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, D.B.; Dhakal, S.; Khatri, B.B. Review Articles Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems: A Scoping Review. Birat J. Helath Sci. 2025, 9, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, Y.; Gurung, D.; Gautam, K. Insight and challenges: Mental health services in Nepal. BJPsych Int. 2021, 18, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornicroft, G.; Kassam, A. Public attitudes, stigma and discrimination against people with mental illness. In Society and Psychosis; Morgan, C., McKenzie, K., Fearon, P., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Adewuya, A.O.; Oguntade, A.A. Doctors’ attitude towards people with mental illness in Western Nigeria. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2007, 42, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, R. Attitudes of Undergraduate Medical Students towards the Persons with Mental Illness in a Medical College of Western Region of Nepal. J. Nepalgunj Med. Coll. 2018, 16, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, D.; Dhakal, S.; Thapa, S.; Bhandari, P.M.; Mishra, S.R. Caregivers’ attitude towards people with mental illness and perceived stigma: A cross- sectional study in a tertiary hospital in Nepal. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahile, Y.; Yitayih, S.; Yeshanew, B.; Ayelegne, D.; Mihiretu, A. Primary health care nurses attitude towards people with severe mental disorders in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A cross sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2019, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tungchama, F.P.; Egbokhare, O.; Omigbodun, O.; Ani, C. Health workers’ attitude towards children and adolescents with mental illness in a teaching hospital in north-central Nigeria. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 31, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.; Bhundia, R.; Mitra, R.; McEwan, K.; Irons, C.; Sanghera, J. Cultural differences in shame-focused attitudes towards mental health problems in Asian and non-Asian student women. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2007, 10, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Sheffield, D.; Green, P.; Asano, K. Cross-cultural comparison of mental health shame: Negative attitudes, external, internal and reflected shame about mental health in Japanese and UK workers. In Shame 4.0; Mayer, C.H., Vanderheiden, E., Wong, P., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Ahad, A.A.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, M.; Junquera, P. Understanding and addressing mental health stigma acrosscCultures for improving psychiatric care: A narrative review. Cureus 2023, 15, e39549. [Google Scholar]

- Brohan, E.; Thornicroft, G. Stigma and discrimination of mental health problems: Workplace implications. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girma, E.; Tesfaye, M.; Froeschl, G.; Möller-Leimkühler, A.M.; Müller, N.; Dehning, S. Public stigma against people with mental illness in the Gilgel Gibe Field Research Center (GGFRC) in Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.H.; Kleinman, A. ‘Face’ and the embodiment of stigma in China: The cases of schizophrenia and AIDS. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal Health Research Counsil (NHRC). Report of National Mental Health Survey 2020. Vol. 5, Goverment of Nepal, Nepal Health Research Council. 2021. Available online: https://nhrc.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Mental-Health-Survey-Report2020.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Worldbank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. 2025. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Lindisfarne, N. Gender, shame, and culture: An anthropological perspective. In Shame: Interpersonal Behavior, Psychopathology, and Culture; Gilbert, P., Andrews, B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 246–260. [Google Scholar]

- Cabral Master, J.M.; Carvalho, C.M.d.O.B.; Motta, C.D.; Sousa, M.C.; Gilbert, P. Attitudes towards mental health problems scale: Confirmatory factor analysis and validation in the Portuguese population. Am. J. Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2016, 19, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Taylor, E.; Wilkes, J.; Veasey, C.; Maybury, S.; Jackson, J.; Lieu, J.; Asano, K. Construction and factorial validation of a short version of the Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (SATMHPS). Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2023, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Asano, K.; Jones, J.; Colman, R.; Taylor, E.; Aledeh, M.; Barnes, K.; Golbourn, L.-M.; Kishimoto, K. The development of the Japanese version of the full and short form of Attitudes Towards Mental Health Problems Scale (J-(S) ATMHPS). Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, G.; Gaag, S.; Thanki, M.; Bondi, L.; Munro, M. A Suitable Space: Improving Counselling Services for Asian People, 1st ed.; Islam Zeitschrift Für Geschichte Und Kultur Des Islamischen Orients; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2001; p. 48. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/suitable-space-Improving-counselling-services/dp/1861343175 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Hsiao, F.H.; Klimidis, S.; Minas, H.; Tan, E.S. Cultural attribution of mental health suffering in Chinese societies: The views of Chinese patients with mental illness and their caregivers. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, D.S.; Keating, F. (Eds.) Mental Health in a Multi-Ethnic Society: A Multidisciplinary Handbook, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; p. 320p. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, A.V. Indian and Western Psychiatry: A Comparison. In Transcultural Psychiatry, 1st ed.; Cox, J.L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986; p. 15. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429447464-17/indian-western-psychiatry-comparison-venkoba-rao (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Stanhope, V. Culture, control, and family involvement: A comparison of psychosocial rehabilitation in India and the United States. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2002, 25, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilbert, P.; Gilbert, J.; Sanghera, J. A focus group exploration of the impact of izzat, shame, subordination and entrapment on mental health and service use in South Asian women living in Derby. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2004, 7, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassam, N. (Ed.) Telling it Like it is: Young Asian Women Talk (Livewire). In Livewire Books for Teenagers; Womens Pr Ltd.: London, UK, 1997; pp. 192p. Available online: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Telling-Like-Young-Asian-Livewire/dp/0704349418 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Chew-Graham, C.; Bashir, C.; Chantier, K.; Burman, E.; Batsleer, J. South Asian women, psychological distress and self-harm: Lessons for primary care trusts. Health Soc. Care Community 2002, 10, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Andrews, B. Shame: Interpersonal Behavior, Psychopathology, and Culture; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, P.; Miles, J. (Eds.) Body Shame: Conceptualisation, Research and Treatment; Routledge: London, UK, 2002; p. 320p. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9781315820255/body-shame-paul-gilbert-jeremy-miles (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Nathanson, D.L. (Ed.) Knowing Feeling: Affect, Script, and Psychotherapy, 1st ed.; W. W. Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 1996; p. 425. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Knowing-Feeling-Psychotherapy-Professional-Hardcover/dp/0393702146 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Babu, B.; Sinha, A. Attitude towards mental health problems and seeking professional help. Int. J. Indian. Psychol. 2023, 11, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar]

- Joji, S. Attitude Towards Mental Health Problems: A Survey Among College Students. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2020, 10, 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.S.; Pathak, A. Gender-based shame-focused attitude of general public toward mental illness: Evidence from Jharkhand, India. J. Ment. Health Hum. Behav. 2021, 26, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, G.; Bedewy, D.; Elamin, A.B.A.; Abdelmonem, K.Y.A.; Teir, H.J.; Alqaderi, N. Attitudes towards mental health problems in a sample of United Arab Emirates’ residents. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Furnham, A. Factors affecting attitude towards seeking professional help for mental illness: A UK Arab perspective. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2013, 16, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Campos, L.; Almeida, H.; Palha, F. Mental health literacy in young adults: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the mental health literacy questionnaire. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1963; p. 413p. Available online: https://books.google.com.np/books/about/Sampling_techniques_2nd_edition.html?id=Y-SxXwAACAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Lange, R.S.; Pascarella, T.; Terenzin, P. How College Affects Students, A Third decade of Research (2nd ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. J. Stud. Aff. Afr. 2014, 2, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.A.; Merunka, D.R. Convenience samples of college students and research reproducibility. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association, W.M. World medical association declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, K.H. An open-source WYSIWYG web application for drawing path diagrams of structural equation models. Struct. Equ. Model. 2023, 30, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M.; Hu, L. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2009, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, A.W.; Craig, S.B. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol. Methods 2012, 17, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Hwang, J.; Ball, J.G.; Lee, J.; Yu, Y.; Albright, D.L. Mental health literacy affects mental health attitude: Is there a gender difference? Am. J. Health Behav. 2020, 44, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riffel, T.; Chen, S.P. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioural responses of healthcare students towards mental illnesses—A qualitative study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 17, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, R.; Hamer, T.; Suhr, R.; König, L. Attitudes toward Psychotherapeutic treatment and health literacy in a large sample of the general population in germany: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2025, 11, e67078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Lieu, J.; Kirkman, A.; Barnes, K.; Liu, G.H.T.; Jackson, J.; Wilkes, J.; Riswani, R. Mental wellbeing of Indonesian students: Mean comparison with UK students and relationships with self-compassion and academic engagement. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Ronaldson, A.; Takhi, S.; Felix, S.; Namasaba, M.; Lawrence, S.; Kellermann, V.; Kapka, A.; Hayes, D.; Dunnett, D.; et al. Cultural influences on fidelity components in recovery colleges: A study across 28 countries and territories. Gen. Psychiatry 2025, 38, e102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y. De-stigmatising self-care: Impact of self-care webinar during COVID-19. Int. J. Spa Wellness 2021, 4, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Tsuchiya, M.; Ishimura, I.; Lin, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Miyata, H.; Kotera, Y.; Shimizu, E.; Gilbert, P. The development of fears of compassion scale Japanese version. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Tsuda-Mccaie, F.; Edwards, A.M.; Bhandari, D.; Williams, D.; Neary, S. Mental Health Shame, Caregiver Identity, and Self-Compassion in UK Education Students. Healthcare 2022, 10, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Jager, J.; Putnick, D.L. Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Dev. Rev. 2013, 33, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotera, Y.; Hara, A.; Newby, C.; Miyamoto, Y.; Ozaki, A.; Ali, Y.; Clinton, P.; Felix, S.; John, C.; Inta, N.; et al. Development and evaluation of a mental health recovery priority measure for cross-cultural research: Global INSPIRE. Chest 2025, 60, 2695–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N-SATMHPS. Available online: https://reach-global.org/our-developed-scales (accessed on 15 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).