Motorized Two-Wheeled Vehicles Contribute Disproportionately to the Increase in Pandemic-Period Road Traffic Fatalities in New York State

Highlights

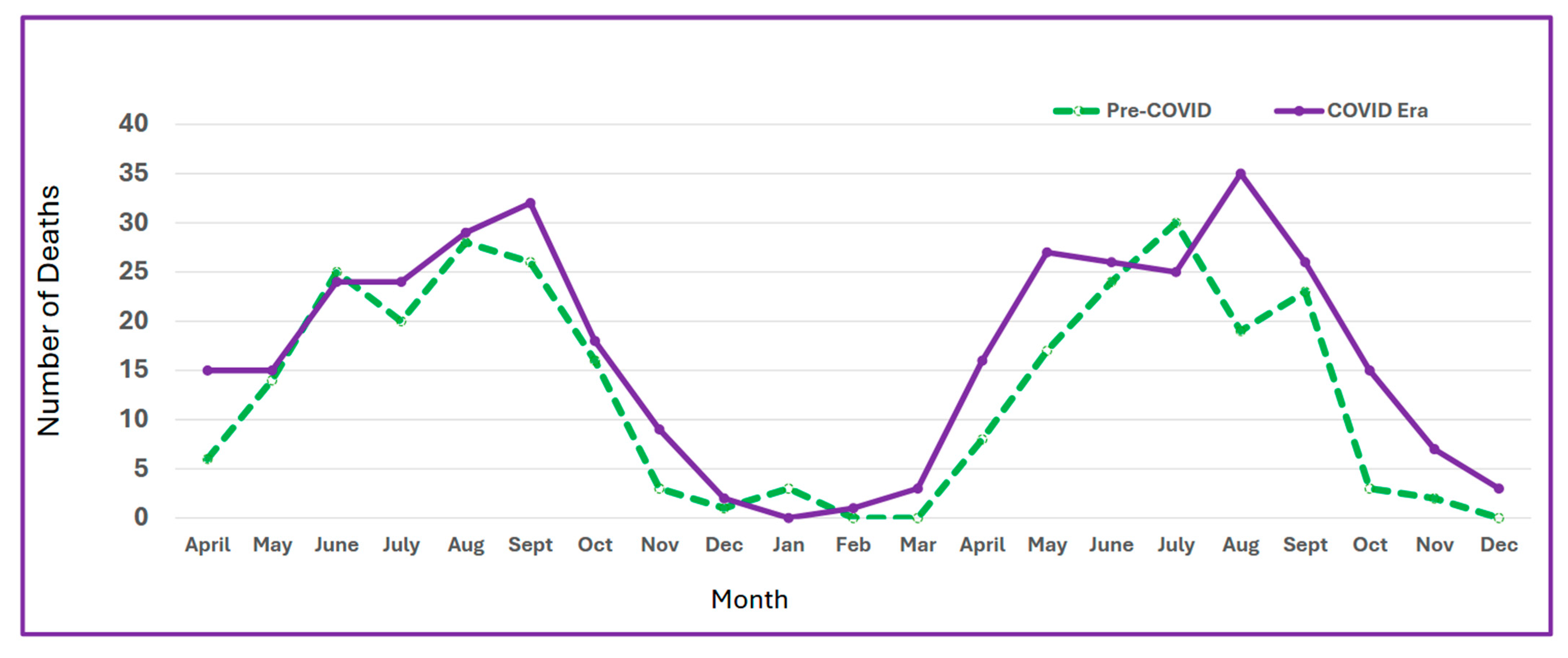

- Roadway mortality was declining in New York State before the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Since the pandemic, mortality increased and did not return to pre-pandemic levels as the pandemic receded.

- This work improves our scientific understanding of the factors contributing to the COVID-19 road mortality increase in New York State.

- Access to shared motorized two-wheeled vehicles, such as e-bikes, is proliferating ahead of injury prevention strategies to address the mortality increase.

- Improvement of data surveillance systems is needed to better characterize the growth of emerging two-wheeled electric vehicles and vehicle types.

- Identification of motorized two-wheeled vehicles as a significant contributor to the increase in pandemic-era roadway mortality can be used to inform the development of countermeasures related to this transportation mode.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Data Source(s)

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Variable Classifications

2.4.1. Pillar 1: Road User-Level Characteristics

2.4.2. Pillar 2: Vehicle and Vehicle Crash Level Characteristics

2.4.3. Pillar 3: Roadway Characteristics

2.4.4. Pillar 4: Speeding

2.4.5. Pillar 5: Post-Crash Care

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pillar 1: Road User Characteristics

3.2. Pillar 2: Vehicle Characteristics

3.3. Pillar 3: Roadway Characteristics

3.4. Pillar 4: Speeding

3.5. Pillar 5: Post Crash Care

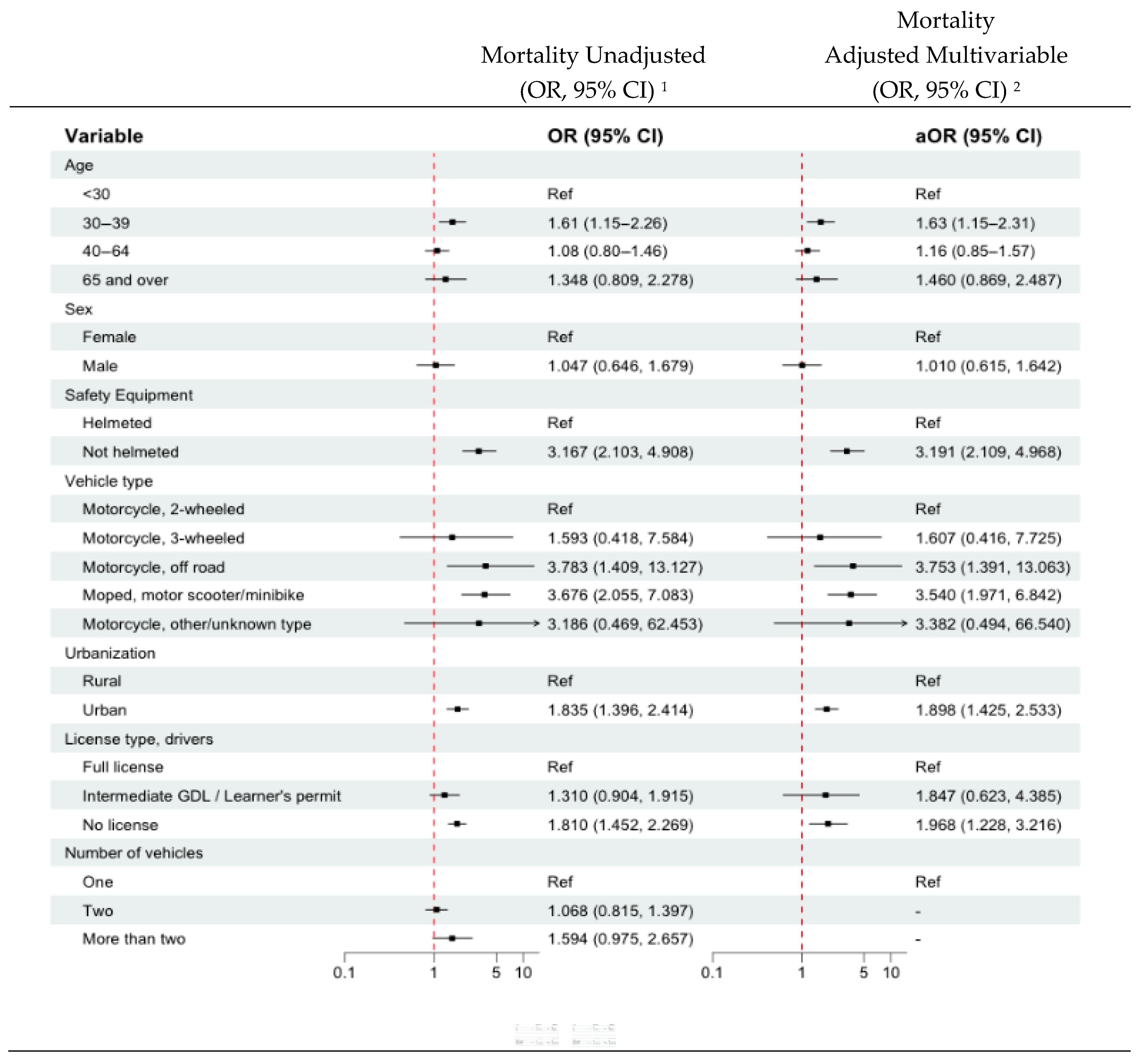

3.6. Independent Risk Factors for Mortality for Persons on Motorized Two- and Three-Wheeler Vehicles

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NYS | New York State |

| FARS | Fatality Analysis Reporting System |

| U.S. | United States |

| GDL | Graduated driver license |

References

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. 2020 Fatality Data Show Increased Traffic Fatalities During Pandemic. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/press-releases/2020-fatality-data-show-increased-traffic-fatalities-during-pandemic (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Office of Behavioral Safety Research. Update to Special Reports on Traffic Safety During the COVID-19 Public Health Emergency: Fourth Quarter Data; (Report No. DOT HS 813 135); National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis. Early Estimate of Motor Vehicle Traffic Fatalities for the First Half (January–June) of 2021; Report No.: DOT HS 813 199; NHTSA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Tefft, B.C. Traffic Safety Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Fatal Crashes in 2020–2022 (Research Brief); AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; Available online: https://aaafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/202407-AAAFTS-Impact-of-COVID.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Adanu, E.K.; Okafor, S.; Penmetsa, P.; Jones, S. Understanding the factors associated with the temporal variability in crash severity before, during, and after the COVID-19 shelter-in-place order. Safety 2022, 8, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.I.; Huang, W.; Khan, S.; Lobanova, I.; Siddiq, F.; Gomez, C.R.; Suri, M.F.K. Mandated societal lockdown and road traffic accidents. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 146, 105747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaufman, E.J.; Holena, D.; Koenig, G.; Martin, N.D.; Maish GO3rd Moran, B.J.; Ratnasekera, A.; Stawicki, S.P.; Timinski, M.; Brown, J. Increase in Motor Vehicle Crash Severity: An Unforeseen Consequence of COVID-19. Am. Surg. 2023, 89, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pressley, J.C.; Aziz, Z.; Bauer, M.J.; Pawlowski, E.; Hines, L.; Roberts, A.; Guzman, J.C. Using a Safe System approach to investigate and characterize factors associated with the increase in COVID-19 era road mortality compared to pre-pandemic mortality in New York State. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basky, G. Spike in e-scooter injuries linked to ride-share boom. CMAJ 2020, 192, E195–E196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shah, N.R.; Aryal, S.; Wen, Y.; Cherry, C.R. Comparison of motor vehicle-involved e-scooter and bicycle crashes using standardized crash typology. J. Saf. Res. 2021, 77, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traynor, M.D., Jr.; Lipsitz, S.; Schroeder, T.J.; Zielinski, M.D.; Rivera, M.; Hernandez, M.C.; Stephens, D.J. Association of scooter-related injury and hospitalization with electronic scooter sharing systems in the United States. Am. J. Surg. 2022, 223, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloom, M.B.; Noorzad, A.; Lin, C.; Little, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Margulies, D.R.; Torbati, S.S. Standing electric scooter injuries: Impact on a community. Am. J. Surg. 2021, 221, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Namiri, N.K.; Lui, H.; Tangney, T.; Allen, I.E.; Cohen, A.J.; Breyer, B.N. Electric Scooter Injuries and Hospital Admissions in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA Surg. 2020, 155, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/46275f9f-ef66-4892-8ddd-a496ef8c1b74/content (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Maag, C. New York Today, STREET WARS: It’s the Golden Age of Weird Vehicles. New York Time. 24 June 2024. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/24/nyregion/street-wars-bicycles-scooters.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Stewart, D. New York Today, STREET WARS: Have E-Bikes Made New York City a ‘Nightmare’? New York Times, 28 May 2024. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/nyregion/street-wars-e-bikes.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- İğrek, S.; Ulusoy, İ. E-scooter-related orthopedic injuries and the treatments applied: Are these scooters a new means of transportation or a new source of trauma? BMC Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- White, D.; Lang, J.; Russell, G.; Tetsworth, K.; Harvey, K.; Bellamy, N. A comparison of injuries to moped/scooter and motorcycle riders in Queensland, Australia. Injury 2013, 44, 855–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Department of Transportation. National Roadway Safety Strategy; Version 1.1; US DOT: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Dumbaugh, E.; Signor, K.; Kumfer, W.; LaJeunesse, S.; Carter, D.; Merlin, L. Implementing Safe Systems in the United States: Guiding Principles and Lessons from International Practice (Report No. CSCRS-R7). Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/62324 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Federal Highway Administration. The Safe System approach (Report No. FHWA-SA-20-015). 2020. Available online: https://safety.fhwa.dot.gov/zerodeaths/docs/FHWA_SafeSystem_Brochure_V9_508_200717.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024). [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis. Fatality Analysis Reporting System Analytical User’s Manual, 1975–2021 (Report No. DOT HS 813 417); National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS). Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/research-data/fatality-analysis-reporting-system-fars (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Jennifer, M. Midtown Lawyer Positive for Coronavirus Is NY’s 1st Case of Person-to-Person Spread; WNBC-4 New York: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pressley, J.C.; Hines, L.M.; Bauer, M.J.; Oh, S.A.; Kuhl, J.R.; Liu, C.; Cheng, B.; Garnett, M.F. Using Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCCS) to Examine Alcohol-Related Motor Vehicle Crash Injury and Enforcement in New York State. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed.; Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- The R Development Team. The R Manuals. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/manuals.html (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Office of the New York State Comptroller. Moving in the Wrong Direction Traffic Fatalities are Growing in New York State June. 2024. Available online: https://www.osc.ny.gov/files/reports/pdf/traffic-fatalities-are-growing-in-new-york-state.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Peng, Y.; Vaidya, N.; Finnie, R.; Reynolds, J.; Dumitru, C.; Njie, G.; Elder, R.; Ivers, R.; Sakashita, C.; Shults, R.A.; et al. Community Preventive Services Task Force. Universal Motorcycle Helmet Laws to Reduce Injuries: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- FHWA. Federal Highway Administration (FHWA)’s Federal Policy, Research, and Funding Opportunities for Shared Micromobility Projects. Available online: https://learn.sharedusemobilitycenter.org/casestudy/federal-highway-administration-fhwas-federal-policy-research-and-funding-opportunities-for-shared-micromobility-projects/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Regulating E-Bicycles and E-Scooters: Issues and Options: A Guide for New York Communities (Including Draft Ordinances). Available online: https://www.access-to-law.com/nyguide/NYGuide.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Olsen, C.S.; Thomas, A.M.; Singleton, M.; Gaichas, A.M.; Smith, T.J.; Smith, G.A.; Peng, J.; Bauer, M.J.; Qu, M.; Yeager, D.; et al. Motorcycle helmet effectiveness in reducing head, face and brain injuries by state and helmet law. Inj. Epidemiol. 2016, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leijdesdorff, H.A.; Siegerink, B.; Sier, C.F.; Reurings, M.C.; Schipper, I.B. Injury pattern, injury severity, and mortality in 33,495 hospital-admitted victims of motorized two-wheeled vehicle crashes in The Netherlands. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New York Times. Traffic Enforcement Dwindled During COVID. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/07/29/upshot/traffic-enforcement-dwindled.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Yasin, Y.J.; Grivna, M.; Abu-Zidan, F.M. Global impact of COVID-19 pandemic on road traffic collisions. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2021, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Meyer, M.W. COVID lockdowns, social distancing, and fatal car crashes: More deaths on Hobbesian Highways? Camb. J. Evid. Based Policy 2020, 4, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY State DMV. Electric Scooters and Bicycles and Other Unregistered Vehicles. Available online: https://dmv.ny.gov/registration/electric-scooters-and-bicycles-and-other-unregistered-vehicles (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- East Bronx Shared E-Scooter Pilot Final Report. Available online: https://www.nyc.gov/html/dot/downloads/pdf/east-bronx-shared-e-scooter-pilot-report.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- NYC E-Vehicle Safety Alliance NYCEVSA. Available online: https://www.nycevsa.org/bills-demands (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- StreetsBlogNYC. Moped and E-Bike Safety Legislation Becomes State Law. Available online: https://nyc.streetsblog.org/2024/07/12/moped-and-e-bike-safety-legislation-becomes-state-law (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Helmet use among motorcyclists who died in crashes and economic cost savings associated with state motorcycle helmet laws--United States, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012, 61, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dua, A.; Wei, S.; Safarik, J.; Furlough, C.; Desai, S.S. National mandatory motorcycle helmet laws may save $2.2 billion annually: An inpatient and value of statistical life analysis. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2015, 78, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L. Concern Over Street Violence Caused by e-Bikes and Mopeds Rises at NYC Town Hall Meeting. 2024. Available online: https://abc7ny.com/post/concern-street-violence-caused-bikes-mopeds-rises-new-york-city-town-hall-meeting/15351445/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Berning, A.; Smither, D.D. Understanding the Limitations of Drug Test Information, Reporting, and Testing Practices in Fatal Crashes [Traffic Safety Facts]: Report Number: DOT HS 812 072 Series: NHTSA BSR Traffic Safety Fact. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/40777 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Cheng, W.; Gill, G.S.; Sakrani, T.; Dasu, M.; Zhou, J. Predicting motorcycle crash injury severity using weather data and alternative Bayesian multivariate crash frequency models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2017, 108, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Transportation. Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highways, 11th ed.; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/73253/dot_73253_DS1.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| Mortality Pre-COVID | Mortality COVID Era | Total Mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change | 1 April 2017–31 December 2019 | 1 April 2020–31 December 2022 | 1 April 2017–31 December 2022 | Chi-square | ||

| n (%) | X2 (p-value) | |||||

| n (%) | 40.2 | n = 428 | n = 600 | n = 1028 1 | ||

| Pillar I: Rider characteristics | ||||||

| Type | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 0.436 (0.509) | ||

| Drivers | 41.8 | 404 (94.4) | 573 (95.5) | 977 (95.0) | ||

| Passengers | 12.5 | 24 (5.6) | 27 (4.5) | 51 (5.0) | ||

| Age, Drivers (years) | 404 | 571 | 975 | 13.442 (0.062) | ||

| ≤19 | 21.4 | 14 (3.5) | 17 (3.0) | 31 (3.2) | ||

| 20–29 | 14.3 | 140 (34.7) | 160 (28.0) | 300 (30.8) | ||

| 30–39 | 92.7 | 82 (20.3) | 158 (27.7) | 240 (24.6) | ||

| 40–64 | 33.6 | 143 (35.4) | 191 (33.5) | 334 (34.3) | ||

| 65 and over | 80.0 | 25 (6.2) | 45 (7.9) | 70 (7.2) | ||

| Sex | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 0.004 (0.947) | ||

| Male | 40.7 | 396 (92.5) | 557 (92.8) | 953 (92.7) | ||

| Drivers | 41.0 | 393 (91.8) | 554 (92.3) | 947 (92.1) | ||

| Passengers | 0.0 | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 6 (0.6) | ||

| Female | 34.4 | 32 (7.5) | 43 (7.2) | 75 (7.3) | ||

| Drivers | 72.7 | 11 (2.6) | 19 (3.2) | 30 (2.9) | ||

| Passengers | 14.3 | 21 (4.9) | 24 (4.0) | 45 (4.4) | ||

| Helmet, wearing | ||||||

| Total study population (n) | 424 | 600 | 1024 | 23.478 (<0.0001) | ||

| No | 270.4 | 27 (6.4) | 100 (16.7) | 127 (12.4) | ||

| Yes | 25.3 | 384 (90.6) | 481 (80.2) | 865 (84.5) | ||

| Unknown | 46.2 | 13 (3.1) | 19 (3.2) | 32 (3.1) | ||

| Drivers (n) | 400 | 573 | 973 | 20.744 (<0.0001) | ||

| No | 268.0 | 25 (6.3) | 92 (16.1) | 117 (12.0) | ||

| Yes | 27.3 | 363 (90.8) | 462 (80.6) | 825 (84.8) | ||

| Unknown | 58.3 | 12 (3.0) | 19 (3.3) | 31 (3.2) | ||

| Alcohol-involved, Drivers | 404 | 573 | 977 | 1.845 (0.174) | ||

| No | 49.8 | 291 (72.0) | 436 (76.1) | 727 (74.4) | ||

| Yes | 21.2 | 113 (28.0) | 137 (23.9) | 250 (25.6) | ||

| License Type, Drivers | 404 | 573 | 977 | 21.719 (<0.0001) | ||

| Full license | 23.7 | 363 (89.9) | 449 (78.4) | 812 (83.1) | ||

| Intermediate GDL/Learner’s Permit 2 | 325.0 | 4 (1.0) | 17 (3.0) | 21 (2.1) | ||

| No License | 188.6 | 35 (8.7) | 101 (17.6) | 136 (13.9) | ||

| Other | 200.0 | 2 (0.5) | 6 (1.0) | 8 (0.8) | ||

| Pillar II: Vehicle Characteristics | ||||||

| Vehicle type | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 25.605 (<0.0001) | ||

| Motorcycle, 2-wheeler | 25.6 | 407 (95.1) | 511 (85.2) | 918 (89.3) | ||

| Motorcycle, 3-wheeler | 100.0 | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.0) | 9 (0.9) | ||

| Motorcycle, off-road | 375.0 | 4 (0.9) | 19 (3.2) | 23 (2.2) | ||

| Moped, motor scooter/minibikes | 361.5 | 13 (3.0) | 60 (10.0) | 73 (7.1) | ||

| Motorcycle, unknown type | 300.0 | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | ||

| Number of Vehicles | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 3.411 (0.182) | ||

| Single | 29.93 | 147 (34.3) | 191 (31.8) | 338 (32.9) | ||

| Two | 38.74 | 253 (59.1) | 351 (58.5) | 604 (58.8) | ||

| Multiple (2+) | 107.14 | 28 (6.5) | 58 (9.7) | 86 (8.4) | ||

| Collision type | 428 | 598 | 1026 | 1.947 (0.856) | ||

| Not a collision with MV in transport | 38.51 | 174 (40.7) | 241 (40.3) | 415 (40.4) | ||

| Angle | 25.58 | 43 (10.0) | 54 (9.0) | 97 (9.5) | ||

| Head-on | 38.00 | 50 (11.7) | 69 (11.5) | 119 (11.6) | ||

| Rear-end | 38.62 | 145 (33.9) | 201 (33.6) | 346 (33.7) | ||

| Sideswipe | 107.14 | 14 (3.3) | 29 (4.8) | 43 (4.2) | ||

| Other | 100.00 | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.7) | 6 (0.6) | ||

| Vehicle maneuver at crash | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 7.286 (0.506) | ||

| Going straight | 44.8 | 248 (57.9) | 359 (59.8) | 607 (59.0) | ||

| Negotiating a curve | 24.0 | 125 (29.2) | 155 (25.8) | 280 (27.2) | ||

| Turning/changing/merging lanes | 33.3 | 21 (4.9) | 28 (4.7) | 45 (4.4) | ||

| Passing or overtaking | 53.9 | 26 (6.1) | 40 (6.7) | 66 (6.4) | ||

| Other | 125.0 | 8 (1.9) | 18 (3.0) | 26 (2.5) | ||

| Pillar IV: Speed | ||||||

| Speed-related crash | 428 | 600 | 1028 | 0.016 (0.901) | ||

| No | 41.7 | 235 (54.9) | 333 (55.5) | 568 (55.3) | ||

| Yes | 38.3 | 193 (45.1) | 267 (44.5) | 460 (44.7) | ||

| Mortality Pre-COVID | Mortality COVID Era | Total Mortality 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change | 1 April 2017–31 December 2019 | 1 April 2020–31 December 2022 | 1 April 2017–31 December 2022 | Chi-square | ||

| n (%) | X2 (p-value) | |||||

| Pillar III: Roadway Characteristics | ||||||

| Urbanization | 18.502 (<0.0001) | |||||

| Rural | −8.50 | 153 (35.7) | 140 (23.3) | 293 (28.5) | ||

| Urban | 67.88 | 274 (64.0) | 460 (76.7) | 734 (71.4) | ||

| RUCC rankings | 8.878 (0.012) | |||||

| Metropolitan | 49.17 | 362 (84.6) | 540 (90.0) | 902 (87.7) | ||

| Non-metropolitan, adjacent | −1.72 | 58 (13.6) | 57 (9.5) | 115 (11.2) | ||

| Non-metropolitan, non-adjacent | −62.50 | 8 (1.9) | 3 (0.5) | 11 (1.1) | ||

| NY State geographical area | 2.248 (0.325) | |||||

| New York City | 63.83 | 94 (22.5) | 154 (26.1) | 248 (24.6) | ||

| Long Island | 21.13 | 71 (17.0) | 86 (14.6) | 157 (15.6) | ||

| Upstate | 38.89 | 252 (60.4) | 350 (59.3) | 602 (59.8) | ||

| Number of lanes | 1.528 (0.676) | |||||

| One | 86.67 | 15 (3.5) | 28 (4.8) | 43 (4.3) | ||

| Two or more, one-way traffic | 0.00 | 12 (2.8) | 12 (2.1) | 24 (2.4) | ||

| Two or more, two-way traffic, divided | 38.10 | 105 (24.8) | 145 (24.8) | 250 (24.8) | ||

| Two or more, two-way traffic, not divided | 37.46 | 291 (68.8) | 400 (68.4) | 691 (68.6) | ||

| Intersection type | 6.926 (0.074) | |||||

| Not an intersection | 51.94 | 258 (60.3) | 392 (65.3) | 650 (63.2) | ||

| Four-way intersection | 35.56 | 90 (21.0) | 122 (20.3) | 212 (20.6) | ||

| T and Y intersections | 3.75 | 80 (18.7) | 83 (13.8) | 163 (15.9) | ||

| Road surface | 5.589 (0.133) | |||||

| Non-trafficway area/driveway access | -- | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Dry | 42.22 | 405 (94.6) | 576 (96.0) | 981 (95.4) | ||

| Wet, water | −28.57 | 21 (4.9) | 15 (2.5) | 36 (3.5) | ||

| Other/not reported/unknown | 250.00 | 2 (0.5) | 8 (1.3) | 10 (1.0) | ||

| Weather | 5.492 (0.139) | |||||

| Clear conditions | 46.36 | 330 (77.1) | 483 (80.5) | 813 (79.1) | ||

| Rain | −40.00 | 10 (2.3) | 6 (1.0) | 16 (1.6) | ||

| Cloudy | 27.38 | 84 (19.6) | 107 (17.8) | 191 (18.6) | ||

| Fog/smog/smoke/crosswinds, other | −66.67 | 4 (0.1) | 4 (0.07) | 8 (0.07) | ||

| Traffic control devices | 7.708 (0.103) | |||||

| No controls | 31.45 | 337 (78.7) | 443 (73.8) | 780 (75.9) | ||

| Traffic control signal | 59.38 | 64 (15.0) | 102 (17.0) | 166 (16.1) | ||

| Stop sign | −50.00 | 12 (2.8) | 6 (1.0) | 18 (1.8) | ||

| Yield sign | -- | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Other signs/signals | -- | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 206.67 | 15 (3.5) | 46 (7.7) | 61 (5.9) | ||

| Lighting conditions | 3.067 (0.216) | |||||

| Daylight | 43.21 | 243 (56.8) | 348 (58.0) | 591 (57.5) | ||

| Dark, not lighted | 26.00 | 50 (11.7) | 63 (10.5) | 113 (11.0) | ||

| Dark, lighted | 52.94 | 102 (23.8) | 156 (26.0) | 258 (25.1) | ||

| Dawn | 25.00 | 4 (0.9) | 5 (0.8) | 9 (0.9) | ||

| Dusk | −14.29 | 28 (6.5) | 24 (4.0) | 52 (5.1) | ||

| Unknown/not reported | 300.00 | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | ||

| Pillar V: Post Crash Care | ||||||

| DOA 2 | 1028 | 1.733 (0.188) | ||||

| Not dead at scene or en route | 31.6 | 291 (68.0) | 383 (63.8) | 674 (65.6) | ||

| Yes, DOA | 58.4 | 137 (32.0) | 217 (36.2) | 354 (34.4) | ||

| Dead at scene | 60.4 | 134 (97.8) | 215 (99.1) | 349 (98.6) | ||

| Dead en route | −33.3 | 3 (2.2) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (1.4) | ||

| Mode of transport | 4.863 (0.088) | |||||

| Not transported | 62.22 | 135 (24.0) | 219 (36.5) | 354 (30.4) | ||

| Ambulance, ground | 26.83 | 287 (51.0) | 364 (60.7) | 651 (56.0) | ||

| Ambulance, air | 150.00 | 6 (1.1) | 15 (2.5) | 21 (1.8) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pressley, J.C.; Aziz, Z.; Hines, L.; Guzman, J.; Pawlowski, E.; Bauer, M. Motorized Two-Wheeled Vehicles Contribute Disproportionately to the Increase in Pandemic-Period Road Traffic Fatalities in New York State. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121883

Pressley JC, Aziz Z, Hines L, Guzman J, Pawlowski E, Bauer M. Motorized Two-Wheeled Vehicles Contribute Disproportionately to the Increase in Pandemic-Period Road Traffic Fatalities in New York State. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121883

Chicago/Turabian StylePressley, Joyce C., Zarah Aziz, Leah Hines, Jancarlos Guzman, Emilia Pawlowski, and Michael Bauer. 2025. "Motorized Two-Wheeled Vehicles Contribute Disproportionately to the Increase in Pandemic-Period Road Traffic Fatalities in New York State" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121883

APA StylePressley, J. C., Aziz, Z., Hines, L., Guzman, J., Pawlowski, E., & Bauer, M. (2025). Motorized Two-Wheeled Vehicles Contribute Disproportionately to the Increase in Pandemic-Period Road Traffic Fatalities in New York State. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121883