Pilot Study on Risk Perception in Practices with Medical Cyclotrons in Radiopharmaceutical Centers in Latin American Countries: Diagnosis and Corrective Measures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology

2.2. Statistical Analysis of the Questionnaire

3. Results and Discussion of the Risk Perception Study

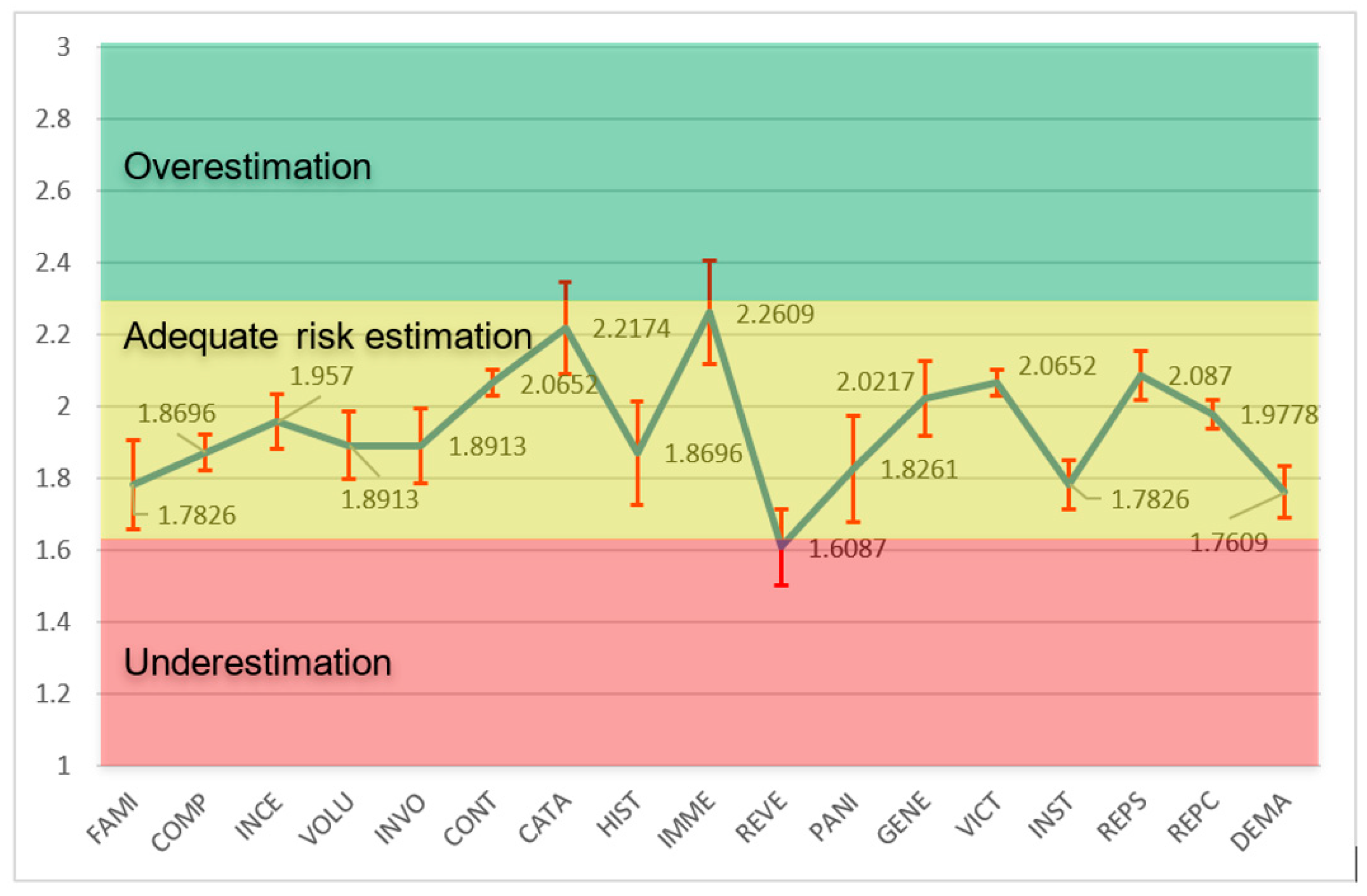

3.1. General Analysis of Variables Outside the Range of Adequate Perception

3.2. Familiarity (FAMI)

3.2.1. Descriptive Interpretation of the Average and Variability

- Average (1.7826): Clear tendency to underestimate, where perceived experience minimizes risks such as neutrons in a cyclotron or manipulation of PET isotopes.

- Standard deviation (SD = 0.8410): High variability (CV ≈ 47.2%), indicating diversity: novices might overestimate, and experts underestimate by habituation.

- Contextual implications: In PET, familiarity with routines (e.g., FDG dispensing) can generate complacency, increasing effective exposure.

3.2.2. Inferential Analysis: Accuracy and Generalization

- Standard error (SE = 0.124): Moderate accuracy.

- 95% confidence interval: (1.533, 2.032), focused on underestimation.

- Limitations: High SD suggests influenced subgroups.

3.2.3. Comparisons with the Literature and Influencing Factors

3.3. Panic (PANI)

3.3.1. Descriptive Interpretation of the Mean and Variability

- Average (1.8261): Indicates an almost adequate perception, but with a slight tendency to underestimate risk. Workers perceive the feelings of panic associated with ionizing exposure (e.g., fear of high doses during cyclotron failure) as less intense than real, possibly due to habituation or reliance on protections, minimizing emotional dread.

- Standard deviation (SD = 0.9956): High variability (CV ≈ 54.5%), suggesting heterogeneity: some strongly underestimate (about 1, low perceived panic), others see greater anxiety (about 2–3), possibly due to differences in personal experience or knowledge of risks.

- Contextual implications: In PET cyclotrons, underestimation of panic can lead to complacency in stressful situations, such as emergencies, affecting emotional response and adherence to safety protocols, although it reduces unnecessary chronic stress.

3.3.2. Inferential Analysis: Precision and Generalization

- Standard error (SE = 0.1468): Moderate accuracy, reflecting uncertainty due to high SD.

- 95% confidence interval: (1.530, 2.122), crossing 2 but centered down, confirming slight underestimation in similar groups.

- Limitations: n = 46; high SD indicates possible asymmetry or subgroups influenced by psychological factors.

3.3.3. Comparisons with the Literature and Influencing Factors

3.4. Reversibility of Consequences (REVE)

3.4.1. Descriptive Interpretation of the Average and Variability

- Average (1.6087): It indicates a clear trend towards underestimation of risk. Workers perceive the consequences of ionizing exposure (e.g., deterministic effects such as burns or stochastic effects such as cancer) as more reversible than real, possibly due to reliance on medical treatments or minimization of irreversible long-term damage.

- Standard deviation (SD = 0.7142): Moderate–high variability (CV ≈ 44.4%), suggesting heterogeneity: some strongly underestimate (about 1, high perceived reversibility), others see lower reversibility (around 2–3), possibly due to differences in knowledge of biological effects or personal experience.

- Contextual implications: In PET cyclotrons, underestimation of irreversibility can lead to complacency in the face of chronic exposures, ignoring permanent damage such as genetic mutations or cancer, affecting adherence to dose limits.

3.4.2. Inferential Analysis: Accuracy and Generalization

- Standard error (SE = 0.1053): Moderate precision, indicating reasonable estimation despite variability.

- 95% confidence interval: (1.396, 1.821), centered below 2, confirming dominant underestimation in similar populations.

- Limitations: n= 46; moderate SD suggests individual influences not captured.

3.4.3. Comparisons with the Literature and Influencing Factors

3.5. Immediacy of Consequences (INME)

3.5.1. Descriptive Interpretation of the Average and Variability

- Average (2.2609): Indicates an almost adequate perception, but with a slight tendency to overestimate risk. Workers perceive the consequences of ionizing exposure (e.g., immediate deterministic effects such as erythema or long-term stochastic effects) as more immediate than real, possibly because of the “fear” associated with radiation, amplifying the perceived urgency.

- Standard deviation (SD = 0.9760): High variability (CV ≈ 43.2%), suggesting heterogeneity: some strongly overestimate (about 3, very immediate consequences), others perceive higher latency (towards 1–2), possibly due to differences in knowledge of biological effects.

- Contextual implications: In PET cyclotrons, overestimation of immediacy may generate anxiety or excessive caution, although useful for acute risks; however, it could underestimate chronic effects such as cancer, affecting the management of cumulative exposures.

3.5.2. Inferential Analysis: Accuracy and Generalization

- Standard error (SE = 0.1439): Moderate accuracy, reflecting uncertainty due to high SD.

- 95% confidence interval: (1.971, 2.551), crossing 2 but centered above, confirming slight overestimation in similar groups.

- Limitations: n = 46; high SD indicates possible asymmetry or influenced subgroups.

3.5.3. Comparisons with the Literature and Influencing Factors

3.6. Radiopharmaceutical Production in Latin America: Actions and Policies to Address Risk Perception

- Mandatory annual refresher training on radiation biology: Establish comprehensive annual courses that focus on the long-term biological impacts of ionizing radiation, including practical modules to improve understanding of the outcomes of chronic exposure. This action addresses gaps in the recognition of persistent effects by providing evidence-based education, with guidance from the IAEA on curriculum design and ALFIM support for regional adaptation in Latin American medical physics programs.

- Real-time dosimetry and feedback systems: Implementation of automated dosimetry tools with immediate warning mechanisms in cyclotron facilities to provide continuous exposure data, helping workers recognize common risks without relying on retrospective assessments. ILO standards for occupational monitoring can ensure implementation, while FRALC can facilitate the regional exchange of best practices to overcome awareness gaps in routine operations.

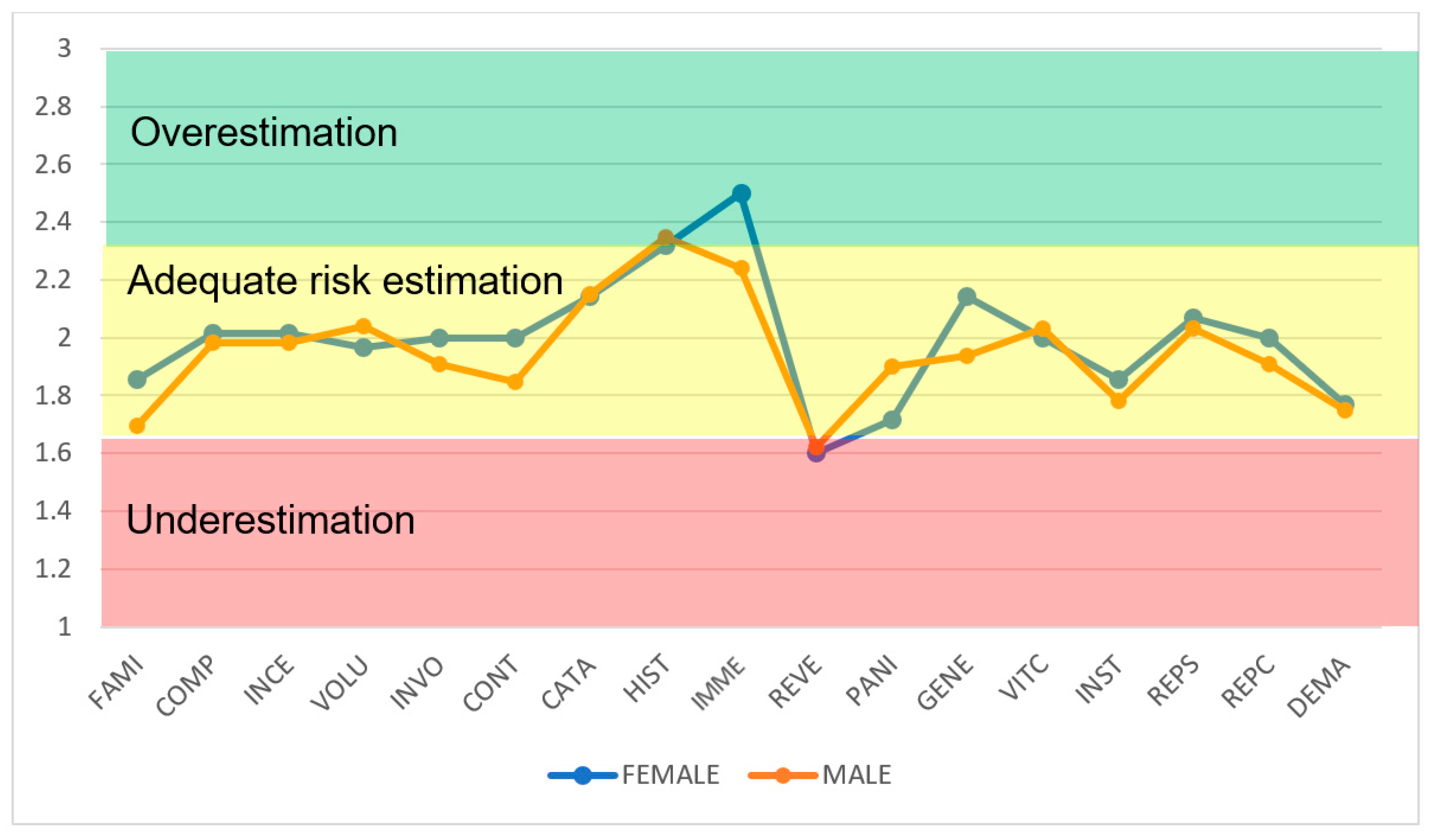

- Gender-sensitive risk communication workshops: Organizing workshops tailored to demographic differences, incorporating interactive sessions on emotional responses to radiation hazards to balance heightened concerns without inducing undue stress. The IAEA’s safety culture principles can guide the content, and the FORO Group coordinates delivery in all Latin American countries to address variations in perceptual biases.

- Age-stratified mentoring programs: pairing young and older workers in mentoring schemes to exchange experiences on radiation safety, foster a shared understanding of exposure dynamics, and reduce generational perceptual disparities. ALFIM’s educational frameworks can support program design, while ILO conventions on workplace equity ensure inclusive participation.

- Institutional transparency and auditing mechanisms: Conducting regular independent audits of security protocols with public reports to build credibility in regulatory bodies, filling gaps in perceived reliability through verifiable compliance data. The IAEA’s General Safety Requirements can provide the audit template, and FRALC advocates for regional standardization in Latin America.

- Virtual Reality Simulations for Temporary Risk Training: Utilization of virtual reality tools to simulate exposure scenarios, illustrating the timeline of radiation effects to correct misperceptions of urgency and promote accurate awareness of risk time. The methodologies of the AAPM working groups can inform the development of simulations, with the support of the FORO Group for their dissemination in Ibero-American networks.

- Task rotation policies for exposure management: Introduction of mandatory rotation programs for high-risk tasks to avoid normalization of mandatory exposures, ensuring that workers experience varied demands and maintain greater vigilance. ILO guidelines on occupational health can enforce these policies, and ALFIM helps to adapt them to the roles of medical physics in Latin America.

- Psychological resilience training programs: Offering specialized training in emotional management techniques for radiation-related anxiety, including coping strategies to balance responses to perceived threats. IRPA’s principles on stakeholder engagement can underpin the program, while FRALC can facilitate regional workshops tailored to Latin American contexts.

- Sharing regional databases of historical incidents: Creating a shared database of past radiation incidents with anonymous case studies for ongoing review, enhancing the collective memory of hazards without inducing fear. The IAEA’s SAFRON system can serve as a model, with the support of the FORO Group for Ibero-American integration.

- Multidisciplinary team-building exercises: Conducting team exercises involving physicists, technicians, and supervisors to strengthen safe collaborative practices, addressing gaps in risk awareness at the group level. AAPM’s quality management reports can guide exercise design, and ALFIM promotes their use in Latin American medical facilities.

- Evidence-based campaigns on hereditary effects: Launch of information campaigns using verified data on long-term hereditary impacts, distributed through digital platforms to reach diverse groups of workers. IAEA safety reports can provide the evidence base, while FRALC can coordinate regional dissemination.

- Supervisor leadership development courses: Supervisor training in proactive safety communication and supervision, ensuring consistent manifestation of protective measures across all teams. IRPA’s guiding principles can inform course content, with Grupo FORO facilitating cross-border training in Latin America.

- Workload assessment policies: Implementation of periodic assessments of work demands with adjustments for exposure intensity, using standardized tools to highlight unavoidable risks. ILO conventions on workplace safety may require them, with ALFIM supporting specific assessments of physics.

- Integrated safety culture audits: Conducting holistic audits combining perception surveys with performance metrics to identify and correct imbalances, ensuring continuous modulation of awareness. The IAEA’s safety culture assessment guidelines can provide the framework, and FRALC advocates for regional benchmarking in Latin America.

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Variable | Average Value | Standard Deviation | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | FAMI | 1.7826 | 0.8410 | 0.124 |

| 2. | COMP | 1.8696 | 0.3405 | 0.050 |

| 3. | INCE | 1.957 | 0.5145 | 0.076 |

| 4. | VOLU | 1.8913 | 0.6404 | 0.0944 |

| 5. | INVO | 1.8913 | 0.7064 | 0.1042 |

| 6. | CONT | 2.0652 | 0.2496 | 0.0368 |

| 7. | CATA | 2.2174 | 0.8670 | 0.1278 |

| 8. | HIST | 1.8696 | 0.9800 | 0.1445 |

| 9. | INME | 2.2609 | 0.9760 | 0.1439 |

| 10. | REVE | 1.6087 | 0.7142 | 0.1053 |

| 11. | PANI | 1.8261 | 0.9956 | 0.1468 |

| 12. | GENE | 2.0217 | 0.7146 | 0.1054 |

| 13. | VICT | 2.0652 | 0.2496 | 0.0368 |

| 14. | INST | 1.7826 | 0.4673 | 0.0689 |

| 15. | REPS | 2.0870 | 0.4631 | 0.0683 |

| 16. | REPC | 1.9778 | 0.2601 | 0.0388 |

| 17. | DEMA | 1.7609 | 0.4800. | 0.0708 |

| Average | 1.9246 | |||

References

- Rockall, A.G.; Allen, B.; Brown, M.J.; El-Diasty, T.; Fletcher, J.; Gerson, R.F.; Goergen, S.; Marrero González, A.P.; Grist, T.M.; Hanneman, K. Sustainability in radiology: Position paper and call to action from ACR, AOSR, ASR, CAR, CIR, ESR, ESRNM, ISR, IS3R, RANZCR, and RSNA. Eur. Radiol. 2025, 35, 5427–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Occupational Radiation Protection General Safety Guide No. GSG-7; IAEA Safety Standards; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.; Coll, R.P.; Cohen, A.S.; Georgiou, D.K.; Manning, H.C. PET Oncological Radiopharmaceuticals: Current Status and Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 6790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter-Pogossian, M.M. The origins of positron emission tomography. Semin. Nucl. Med. 1992, 22, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, G.B. Production of radionuclides. In Fundamentals of Nuclear Pharmacy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ávila-Rodríguez, M.A.; Jalilian, A.R.; Korde, A.; Schlyer, D.; Haji-Saeid, M.; Paez, J.; Perez-Pijuan, S. Current status on cyclotron facilities and related infrastructure supporting PET applications in Latin America and the Caribbean. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2022, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Sources: International Basic Safety Standards; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IAEA. Radiation Protection and Safety in Medical Uses of Ionizing Radiation. Specific Safety Guide (Number no. SSG-46); IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, M.K.; DeGrado, T.R. Cyclotron Production of PET Radiometals in Liquid Targets: Aspects and Prospects. Curr. Radiopharm. 2021, 14, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Perception of risk. Science 1987, 236, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, C. Social Benefit versus Technological Risk. Science 1969, 165, 1232–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.D.; Sondak, H.; Diekmann, K.A. When fairness neither satisfies nor motivates: The role of risk aversion and uncertainty reduction in attenuating and reversing the fair process effect. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2011, 116, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, T.M. Risk perception and safety culture: Tools for improving the implementation of disaster risk reduction strategies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 47, 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate change risk perception and policy preferences: The role of affect, imagery, and values. Clim. Change 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Taylor, R.W. Assessing the role of risk perception in ensuring sustainable arsenic mitigation. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 9, 100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, L.S.; Beyer, T. Subjective perception of radiation risk. J. Nucl. Med. 2011, 52, 29S–35S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Díaz, F.; Torres-Valle, A.; Jauregui-Haza, U.J. A Systematic Review of Integrated Risk Indicators for PET Radiopharmaceutical Production: Methodologies and Applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perko, T. Radiation risk perception: A discrepancy between the experts and the general population. J. Environ. Radioact. 2014, 133, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shubayr, N.; Muawwadhah, M.; Shami, M.; Jassas, H.; Tawhari, R.; Oraybi, O.; Madkhali, A.; Aldosari, A.; Alashban, Y. Assessment of radiation safety culture among radiological technologists in medical imaging departments in Saudi Arabia. Radioprotection 2024, 59, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Jenkins, M. Gender Differences in Risk Assessment: Why do Women Take Fewer Risksthan Men? Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2006, 1, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, N.J.; Love, B.C.; Ramscar, M.; Otto, A.R.; Smayda, K.; Maddox, W.T. Exploratory decision-making as a function of lifelong experience, not cognitive decline. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016, 145, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, M.; Iwamoto, S.; Okahisa, R.; Kishida, S.; Sakama, M.; Honda, E. Knowledge and risk perception of radiation for Japanese nursing students after the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant disaster. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 94, 104552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, X. How does soil pollution risk perception affect farmers’ pro-environmental behavior? The role of income level. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ban, J.; Sun, K.; Han, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Bi, J. The influence of public perception on risk acceptance of the chemical industry and the assistance for risk communication. Saf. Sci. 2013, 51, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, O.O.; Adebayo, A.E.; Adebisi, T.F.; Ewegbemi, M.K.; Abidoye, A.T.; Popoola, B.F. Knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of occupational hazards and safety practices in Nigerian healthcare workers. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, M.; Das, T.; Garelick, H.; Priest, N. Public knowledge, sentiments, and perceptions of low dose radiation (LDR) and power production, with special reference to reactor accidents. Pure Appl. Chem. 2024, 96, 1013–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Choi, Y.Y.; Yang, M.; Jin, Y.W.; Seong, K.M. Risk perception of radiation emergency medical staff on low-dose radia tion exposure: Knowledge is a critical factor. J. Environ. Radioact. 2021, 227, 106502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Monaca, S.; Dini, V.; Grande, S.; Palma, A.; Tkaczyk, A.H.; Koch, R.; Murakas, R.; Perko, T.; Duranova, T.; Salomaa, S.; et al. Assessing radiation risk perception by means of a European stakeholder survey. J. Radiol. Prot. 2021, 41, 1145–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, S.; Auwer, C.D.; Pourcher, T.; Russo, S.; Drouot, C.; Beccia, M.R.; Creff, G.; Fiorelli, F.; Leriche, A.; Castagnola, F.; et al. Comparative analysis of the perception of nuclear risk in two populati ons (expert/non-expert) in France. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 2288–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacquin, A.-S.; Altay, S.; Aarøe, L.; Mercier, H. Disgust sensitivity and public opinion on nuclear energy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 80, 101749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, M.; Shasko, L.; Condor, J.; Landrie-Parker, D. Radiation Workers and Risk Perceptions: Low Dose Radiation, Nuclear Po wer Production, and Small Modular Nuclear Reactors. J. Nucl. Eng. 2023, 4, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, J.M. Some observations on perceptions of radiation risks in the context of nuclear power plant accidents. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2023, 199, 2169–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Kim, J.U.; Lee, D.; Jin, Y.W.; Jo, H.; Jun, J.K.; Park, S.; Seo, S. Radiation risk perception and its associated factors among residents l iving near nuclear power plants: A nationwide survey in Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crutchfield, N.; Roughton, J. Safety Culture: An Innovative Leadership Approach; Butterworth-Heinemann: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flin, R. “Danger—Men at work”: Management influence on safety. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2003, 13, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Chmiel, N.; Hershcovis, M.S.; Walls, M. Life on the line: Job demands, perceived co-worker support for safety, and hazardous work events. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugas, C.S.; Meliá, J.L.; Silva, S.A. The “is” and the “ought”: How do perceived social norms influence safe ty behaviors at work? J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, D.L. Sensitivity to social information, social referencing, and safety atti tudes in a hazardous occupation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2014, 19, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grocutt, A.; Granger, S.; Turner, N.; Fordham, M.; Chmiel, N. Relative influence of senior managers, direct supervisors, and coworkers on employee injuries and safety behaviors. Saf. Sci. 2023, 164, 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, K.L. The Social Psychology of Safety: Leadership, Compliance and Behavior i n High Risk Workplaces. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2025, 2, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschal Ikedi, A. Sociological perspectives on industrial waste management and worker we ll-being: Analyzing risk perception and policy implementation. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 27, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell Siam, A.T.; Torres Valle, A.; Nuñez Valdivie, Y.; Aranzola Acea, Á.M. Análisis de percepción de riesgos laborales de tipo biológico con la utilización de un sistema informático especializado. Rev. Cuba. Farm. 2013, 47, 324–338. [Google Scholar]

- Torres Valle, A.; Carbonell Siam, A.T.; Elías Hardy, L.L. Estudios de personalidad y de percepción de riesgo aplicados a los peligros ocupacionales durante empleo de fuentes de radiaciones ionizantes. Nucleus 2021, 69, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Benavides, F.; Gimeno, D.; Benach, J.; Martínez, J.; Jarque, S.; Berra, A.; Devesa, J. Descripción de los factores de riesgo psicosocial en cuatro empresas. Gac. Sanit. 2002, 16, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melià, J.L.; Sesé, A. La medida del clima de seguridad y salud laboral. An. Psicol./Ann. Psychol. 1999, 15, 269–289. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Jiménez, B. Factores y riesgos laborales psicosociales: Conceptualización, historia y cambios actuales. Med. Segur. Trab. 2011, 57, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portell Vidal, M. Riesgo Percibido, un Procedimiento de Evaluación; Normas de Trabajos Peligrosos, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, NTP: Barcelona, Spain, 2007; Volume 578. [Google Scholar]

- Teresa Carbonel-Siam, A.; Torres-Valle, A. Evaluación de percepción de riesgo ocupacional. Ing. Mecánica 2010, 13, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch. Psychol. 1932, 22, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, A. Delphi Method Variants In Information Systems Research: Taxonomy Development And Application. St. Petersburg Math. J. 2017, 15, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotian, H.; Varghese, A.L.; Rohith, M. An R Function for Cronbach’s Alpha Analysis: A Case-Based Approach. Natl. J. Community Med. 2022, 13, 571–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbo, A.A. Cronbach’s Alpha: Review of Limitations and Associated Recommendations. J. Psychol. Afr. 2010, 20, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chou, C.P.; Stacy, A.W.; Ma, H.; Unger, J.; Gallaher, P. SAS and SPSS macros to calculate standardized Cronbach’s alpha using the upper bound of the phi coefficient for dichotomous items. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Artino, A.R., Jr. Analyzing and Interpreting Data From Likert-Type Scales. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2013, 5, 541–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, J.R.; Lindner, N. Interpreting Likert type, summated, unidimensional, and attitudinal sc ales: I neither agree nor disagree, Likert or not. Adv. Ag Dev. 2024, 5, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescaroli, G.; Velazquez, O.; Alcántara-Ayala, I.; Galasso, C.; Kostkova, P.; Alexander, D. A Likert Scale-Based Model for Benchmarking Operational Capacity, Orga nizational Resilience, and Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, A.L.; Gidel, T.; Vezzetti, E. Toward a Common Procedure Using Likert and Likert-Type Scales in Small Groups Comparative Design Observations. In Proceedings of the DS 84: Proceedings of the DESIGN 2016 14th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–19 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Warmbrod, J.R. Reporting and interpreting scores derived from Likert-type scales. J. Agric. Educ. 2014, 55, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D. Likert Scale: Explored and Explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, G.M.; Thomas, J.J.; Austin, T.M.; Fanfan, J.; Yaster, M. Radiation Safety Perceptions and Practices Among Pediatric Anesthesiologists: A Survey of the Physician Membership of the Society for Pediatric Anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2019, 128, 1242–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Ji, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Z.; Sun, J. Investigation and analysis of the radiation protection status of radiation workers during the peri-pregnancy period. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1501027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobov, A.; Riad, A.; Koščík, M.; Peřina, A. Correlates of Perceived Nuclear Risk and Emergency Preparedness Near Czech Nuclear Power Plants: A Cross-Sectional Study. Bratisl. Med. J. 2025, 126, 2396–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younesi Heravi, M.A.; Keshtkar, M.; Khoshdel, E.; Pishgadam, M.; Poorbarat, S.; Jafarzadeh Hesari, M. Evaluation of the Status of Knowledge, Attitude, and Performance of Radiology Department Staff Regarding Radiation Safety Principles at Hospitals in the North and Northeast of Iran. Front. Biomed. Technol. 2024, 11, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, K.A.; Boateng Addo, H.; Daniels, J. Radiation safety: Knowledge, attitudes, practices and perceived socioeconomic impact in a limited-resource radiotherapy setting. Ecancer J. 2025, 19, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashiguchi, N.; Cao, J.; Lim, Y.; Kubota, Y.; Kitahara, S.; Ishida, S.; Kodama, K. The Effects of Psychological Factors on Perceptions of Productivity in Construction Sites in Japan by Worker Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Q.T.; Walker, D.; Frush, D.; Daniel, M.; Pavkov, T. Intrapersonal and Institutional Influences On Overall Perception of Radiation Safety Among Radiologic Technologists. Radiol. Technol. 2022, 93, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yashima, S.; Chida, K. Awareness of Medical Radiologic Technologists of Ionizing Radiation and Radiation Protection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seong, K.M.; Kwon, T.; Seo, S.; Lee, D.; Park, S.; Jin, Y.W.; Lee, S.-S. Perception of low dose radiation risks among radiation researchers in Korea. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, G.; González, Y.; Sánchez, C. Risk perception among workers exposed to ionizing radiation: A qualitative view. Radioprotection 2024, 59, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollough, C. WE-C-217A-01: Risk Estimation versus Risk Perception. Med. Phys. 2012, 39, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendee, W. Real and perceived risks of medical radiation exposure. West. J. Med. 1983, 138, 380–386. [Google Scholar]

- Rehani, M.M. Radiation effects and risks: Overview and a new risk perception index. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2015, 165, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portell, M.; Gil, R.M.; Losilla, J.M.; Vives, J. Characterizing Occupational Risk Perception: The Case of Biological, E rgonomic and Organizational Hazards in Spanish Healthcare Workers. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renn, O. Health impacts of large releases of radionuclides. Mental health, stre ss and risk perception: Insights from psychological research. Ciba Found. Symp. 1997, 203, 205–226; discussion 226–231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perko, T.; Adam, B.; Stassen, K.R. The differences in perception of radiological risks: Lay people versus new and experienced employees in the nuclear sector. J. Risk Res. 2014, 18, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A. Physical and biological dosimetry for risk perception in radioprotection. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2005, 48, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeford, R. Radiation in the workplace—A review of studies of the risks of occupat ional exposure to ionising radiation. J. Radiol. Prot. 2009, 29, A61–A79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wondergem, J.; Rosenblatt, E. IAEA activities related to radiation biology and health effects of radiation. J. Radiol. Prot. 2012, 32, N123–N127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagergren Lindberg, M.; Hedman, C.; Lindberg, K.; Valentin, J.; Stenke, L. Mental health and psychosocial consequences linked to radiation emergencies—Increasingly recognised concerns. J. Radiol. Prot. 2022, 42, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IAEA. Communication and Consultation with Interested Parties by the Regulatory Body; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Shi, S.; Yang, Z.; Lan, Y.; Han, J.; Liu, Y. Awareness and preparedness level of medical workers for radiation and nuclear emergency response. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1410722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, A.L.; Conca, J.; Glines, W.M.; Waltar, A.E. How the science of radiation biology can help reduce the crippling fear of low-level radiation. Health Phys. 2023, 124, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, R.C. Radiation, Fear, and Common Sense Adaptations in Patient Care. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 51, 675–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinendegen, L.E.; Cuttler, J.M. Biological effects from low doses and dose rates of ionizing radiation: Science in the service of protecting humans, a synopsis. Health Phys. 2018, 114, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagby, M.; Goldberg, A.; Becker, S.; Schwartz, D.; Bar-Dayan, Y. Health implications of radiological terrorism: Perspectives from Israel. J. Emergencies Trauma Shock. 2009, 2, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Variable (Code) 1 [Quiz Questions 2] | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Individual Variables | ||

| 1 | Familiarity (FAMI) [1] | Degree of experience of the worker in the production of radiopharmaceuticals. |

| 2 | Understanding Risk (COMP) [2,3,4,5,6] | Degree of knowledge of the individual about the radiological risk. |

| 3 | Uncertainty (INCE) [7] | The subject’s perception of the degree of knowledge that science has about radiological risk. |

| 4 | Voluntarism (VOLU) [8,9] | Degree of decision by the subject as to whether to expose himself to radiological risk. |

| 5 | Personal involvement (INVO) [10,11] | The degree to which occupational exposure directly affects him or his family (target of risk). |

| 6 | Ability to control (CONT) [12] | Degree to which the subject can perform an effective conduct to modify the situation of radiological risk. |

| 7 | Employment (VINC) [13] | The degree to which the individual depends for his or her subsistence on the performance of the work related to the radiological risk. |

| Variables of a physical nature | ||

| 8 | Catastrophic potential (CATA) [14,15] | Degree of the fatality of the consequences of radiological exposure and its concurrence in space and time. |

| 9 | History of accidents (HIST) [16,17] | Degree to which the production of radiopharmaceuticals has a prior history of catastrophes or hazards |

| 10 | Immediacy of consequences (INME) [18] | The degree to which the consequences of occupational radiological exposure are immediate. |

| 11 | Reversibility of consequences (REVE) [19,20] | Extent to which the consequences of occupational radiological exposure are reversible |

| 12 | Panic (PANI) [21] | The degree to which radiological risk produces sensations such as fear, terror or anxiety. |

| 13 | Effect on generations (GENE) [22,23,24] | The degree to which occupational radiological exposure can affect future generations. |

| 14 | Identity of the victims (VICT) [25] | The degree to which occupational exposure has affected people close to them or is only measured in the form of statistics. |

| Variables related to risk management | ||

| 15 | Trust in Institutions (INST) [26,27] | The degree to which the worker trusts or gives credibility to the institutions responsible for radiation safety. |

| 16 | Supervisors’ response (REPS) [28] | Degree to which supervisors express themselves regarding the radiological protection of personnel. |

| 17 | Response from colleagues (REPC) [29] | Degree to which the conduct of the work group supports safe attitudes of practice with ionizing radiation |

| 18 | Labor Demand (DEMA) [30] | Degree to which working conditions demand exposure to radiological hazards. |

| Reliability Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s alpha | Cronbach’s alpha based on standardized items | Number of questions passed |

| 0.718 | 0.760 | 29 |

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum of Squares | df | Middle Square | F | Sig | ||

| Between people | 41.301 | 45 | 0.918 | |||

| Inside people | Between elements | 82.186 | 28 | 2.935 | 11.342 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 326.090 | 1260 | 0.259 | |||

| Total | 408.276 | 1288 | 0.317 | |||

| Total | 449.577 | 1333 | 0.337 | |||

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Load Extraction Sums Squared | ||||

| Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 2.416 | 21.964 | 21.964 | 2.416 | 21.964 | 21.964 |

| 2 | 1.730 | 15.724 | 37.688 | 1.730 | 15.724 | 37.688 |

| 3 | 1.317 | 11.971 | 49.659 | 1.317 | 11.971 | 49.659 |

| 4 | 1.123 | 10.211 | 59.871 | 1.123 | 10.211 | 59.871 |

| 5 | 0.994 | 9.032 | 68.903 | |||

| 6 | 0.920 | 8.364 | 77.267 | |||

| 7 | 0.751 | 6.827 | 84.094 | |||

| 8 | 0.697 | 6.332 | 90.427 | |||

| 9 | 0.443 | 4.031 | 94.458 | |||

| 10 | 0.311 | 2.827 | 97.284 | |||

| 11 | 0.299 | 2.716 | 100.000 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | ||||||

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Load Extraction Sums Squared | ||||

| Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 2.287 | 19.059 | 19.059 | 2.287 | 19.059 | 19.059 |

| 2 | 2.031 | 16.922 | 35.981 | 2.031 | 16.922 | 35.981 |

| 3 | 1.431 | 11.921 | 47.902 | 1.431 | 11.921 | 47.902 |

| 4 | 1.220 | 10.165 | 58.067 | 1.220 | 10.165 | 58.067 |

| 5 | 1.144 | 9.533 | 67.600 | 1.144 | 9.533 | 67.600 |

| 6 | 1.022 | 8.516 | 76.116 | 1.022 | 8.516 | 76.116 |

| 7 | 0.854 | 7.117 | 83.233 | |||

| 8 | 0.744 | 6.197 | 89.431 | |||

| 9 | 0.501 | 4.174 | 93.605 | |||

| 10 | 0.347 | 2.895 | 96.500 | |||

| 11 | 0.281 | 2.345 | 98.845 | |||

| 12 | 0.139 | 1.155 | 100.000 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis (PCA). | ||||||

| ANOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Initial Eigenvalues | Load Extraction Sums Squared | ||||

| Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 1.415 | 35.385 | 35.385 | 1.415 | 35.385 | 35.385 |

| 2 | 1.101 | 27.536 | 62.921 | 1.101 | 27.536 | 62.921 |

| 3 | 0.828 | 20.698 | 83.619 | |||

| 4 | 0.655 | 16.381 | 100.000 | |||

| Extraction method: principal component analysis (PCA) | ||||||

| Variable | Classification | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 14 | 30.4% |

| Male | 32 | 69.6% | |

| Age | 26–45 years | 31 | 67.4% |

| >45 years old | 15 | 32.6% | |

| Level of Education | Technician | 5 | 10.9% |

| University | 17 | 37.0% | |

| With postgraduate degrees | 24 | 52.1% | |

| Income from salary | Lower than the national average | 14 | 30.5% |

| Adequate | 21 | 45.6% | |

| Higher than the national average | 11 | 23.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montero-Díaz, F.; Torres-Valle, A.; Jauregui-Haza, U. Pilot Study on Risk Perception in Practices with Medical Cyclotrons in Radiopharmaceutical Centers in Latin American Countries: Diagnosis and Corrective Measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121885

Montero-Díaz F, Torres-Valle A, Jauregui-Haza U. Pilot Study on Risk Perception in Practices with Medical Cyclotrons in Radiopharmaceutical Centers in Latin American Countries: Diagnosis and Corrective Measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2025; 22(12):1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121885

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontero-Díaz, Frank, Antonio Torres-Valle, and Ulises Jauregui-Haza. 2025. "Pilot Study on Risk Perception in Practices with Medical Cyclotrons in Radiopharmaceutical Centers in Latin American Countries: Diagnosis and Corrective Measures" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 22, no. 12: 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121885

APA StyleMontero-Díaz, F., Torres-Valle, A., & Jauregui-Haza, U. (2025). Pilot Study on Risk Perception in Practices with Medical Cyclotrons in Radiopharmaceutical Centers in Latin American Countries: Diagnosis and Corrective Measures. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 22(12), 1885. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph22121885