Disaster Risk Reduction Funding: Investment Cycle for Flood Protection in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

Evolving Mechanisms of Flood Protection in Japan

2. Methods

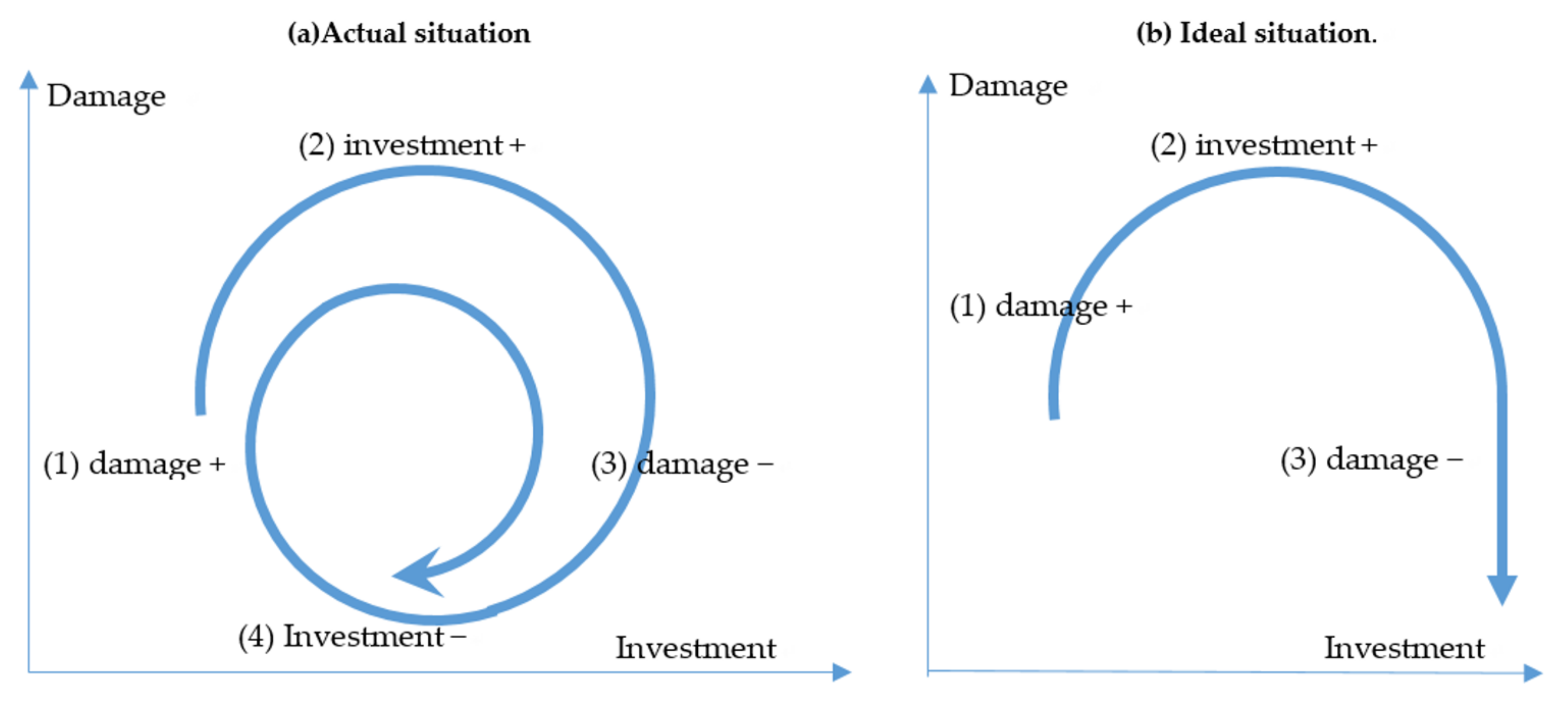

- Large disasters that triggered an increase in the budget for flood protection were identified, and periods of increasing damage were determined.

- The periods of increasing budgets following large disasters were determined.

- The periods of decreasing budgets and damage before the next large disaster were determined.

3. Results and Discussion

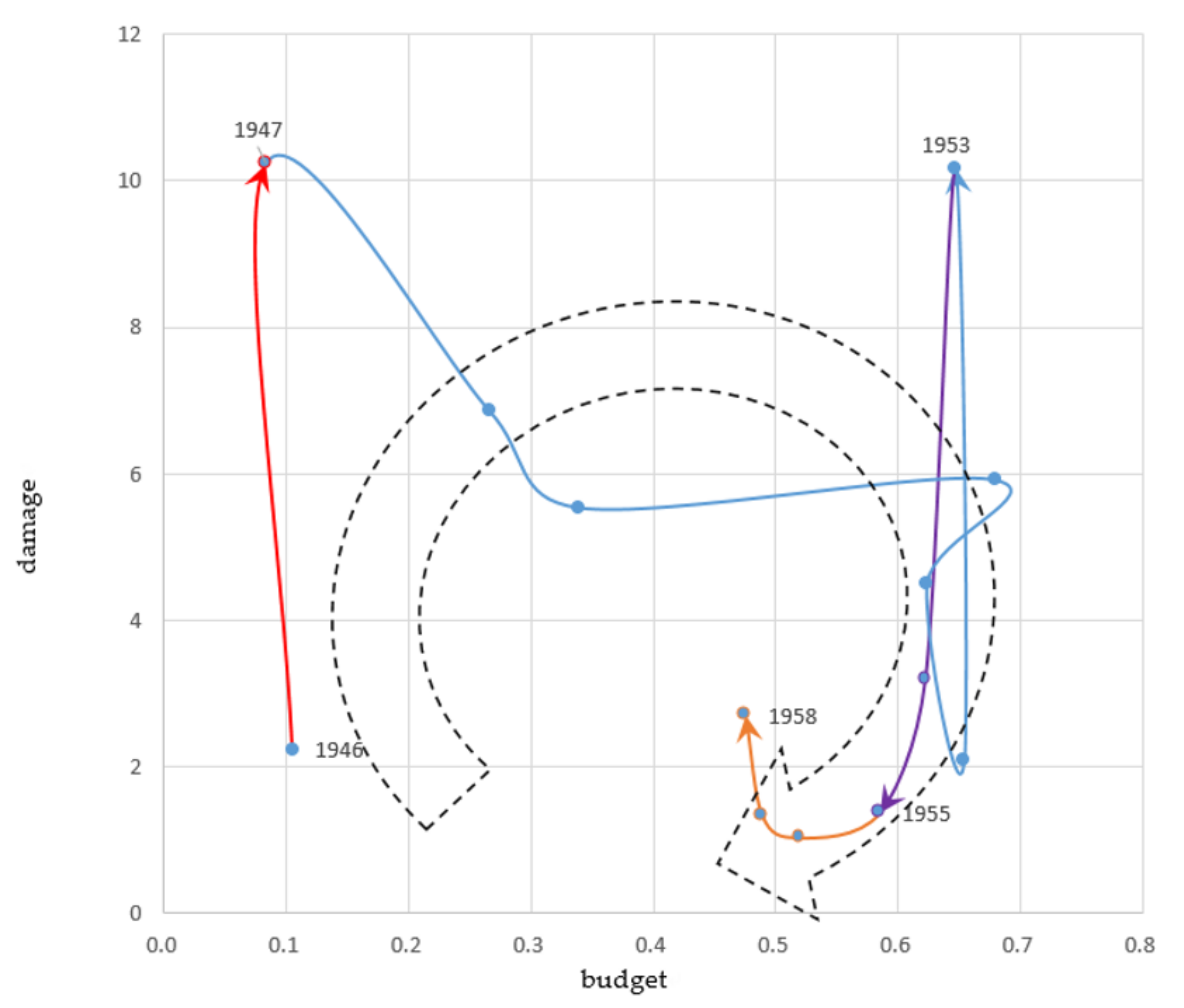

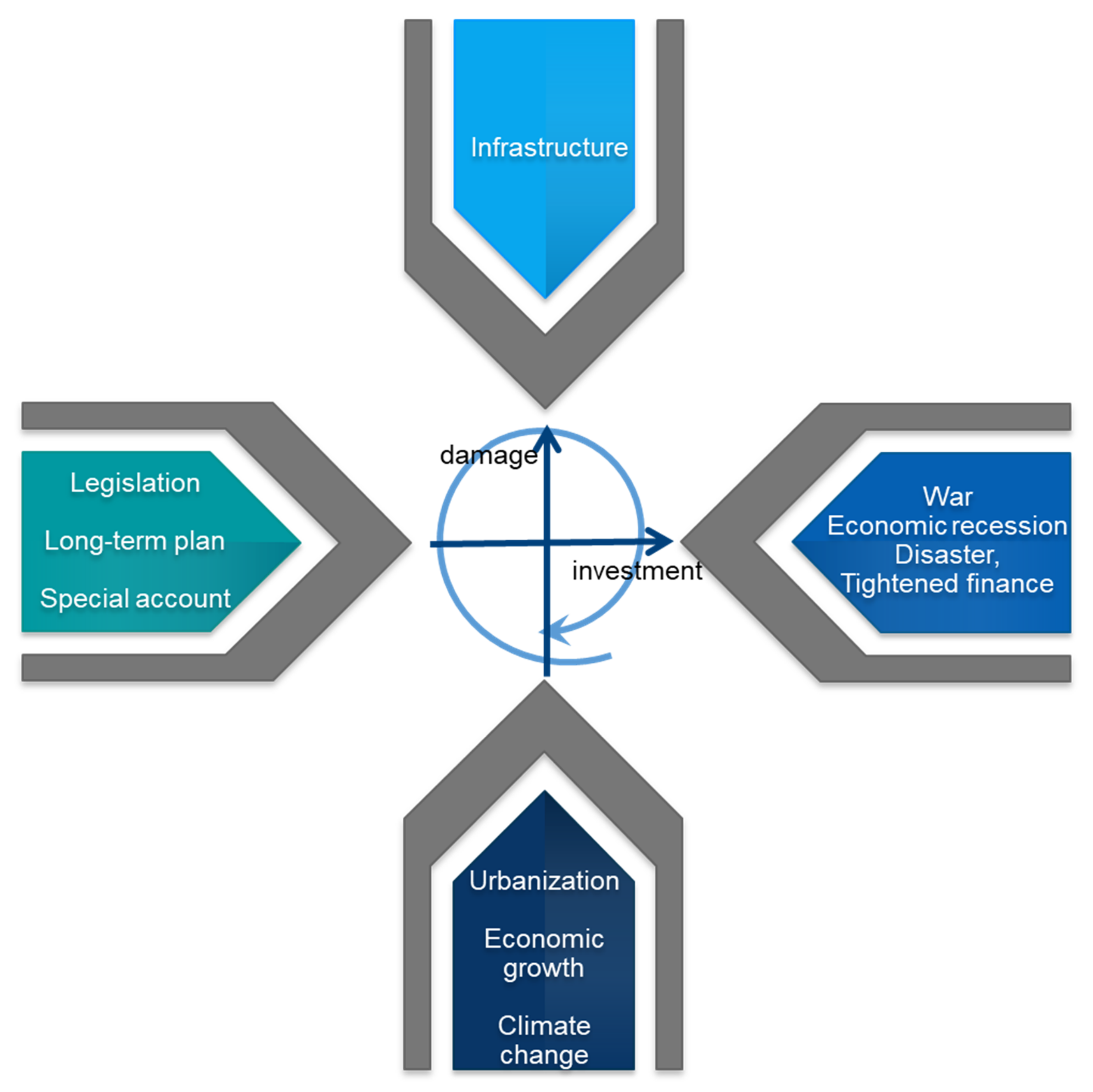

3.1. Five Investment Cycles for Flood Protection in Japan

- 1878–1906 Establishing the modernized mechanism of flood protection.

- 1906–1931 Constructing structural frameworks, such as channels and dikes, for major rivers.

- 1931–1945 National land devastation during the wartime regime.

- 1945–1958 Responding to a series of flood disasters.

- 1958–2014 Implementing flood protection during high growth and recession.

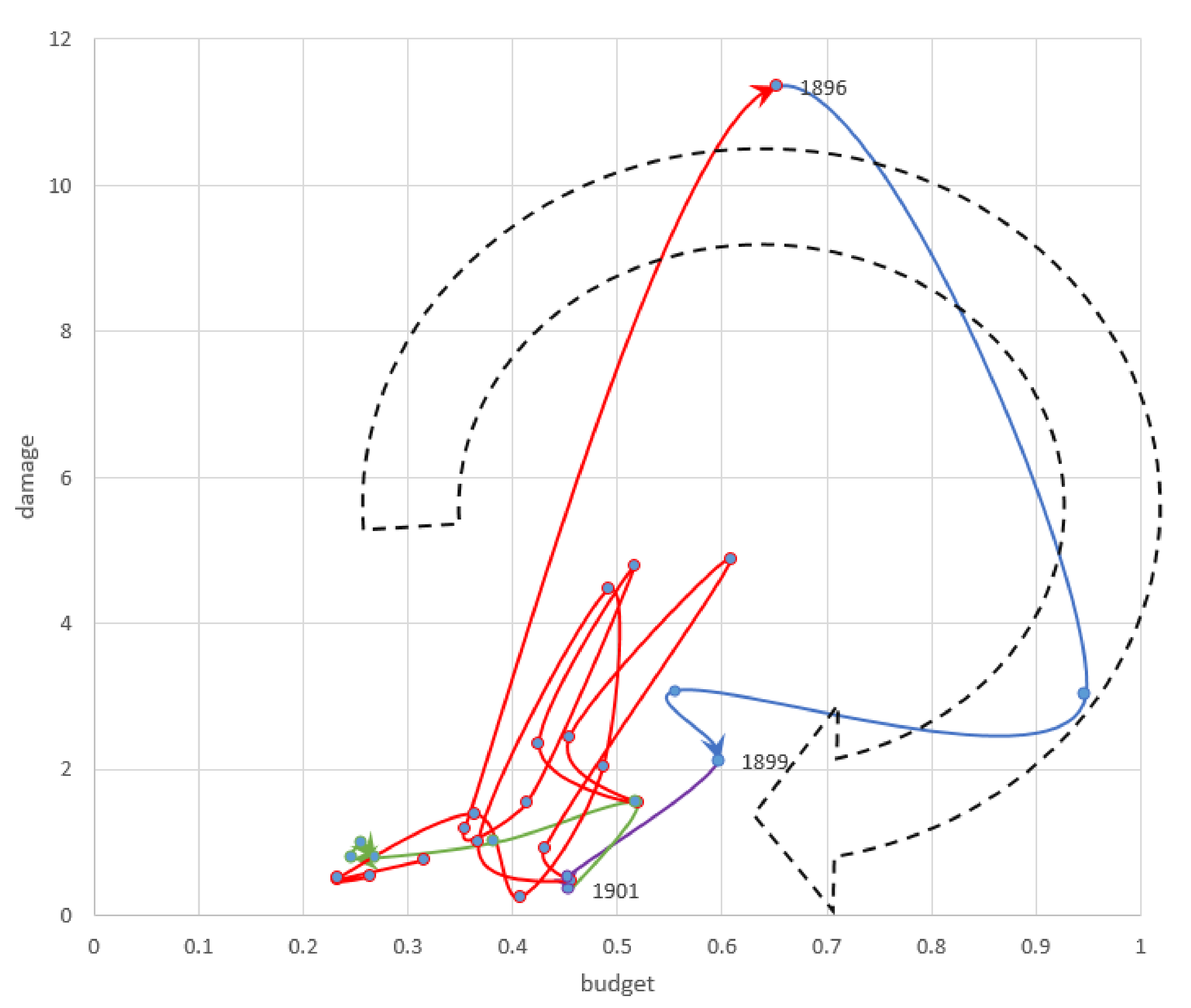

3.1.1. Establishing a Modernized Mechanism for Flood Protection (1878–1906)

Increasing Damage (1878–1896)

Increasing Budget (1896–1899)

Decreasing Damage (1899–1901)

Decreasing Budget (1901–1906)

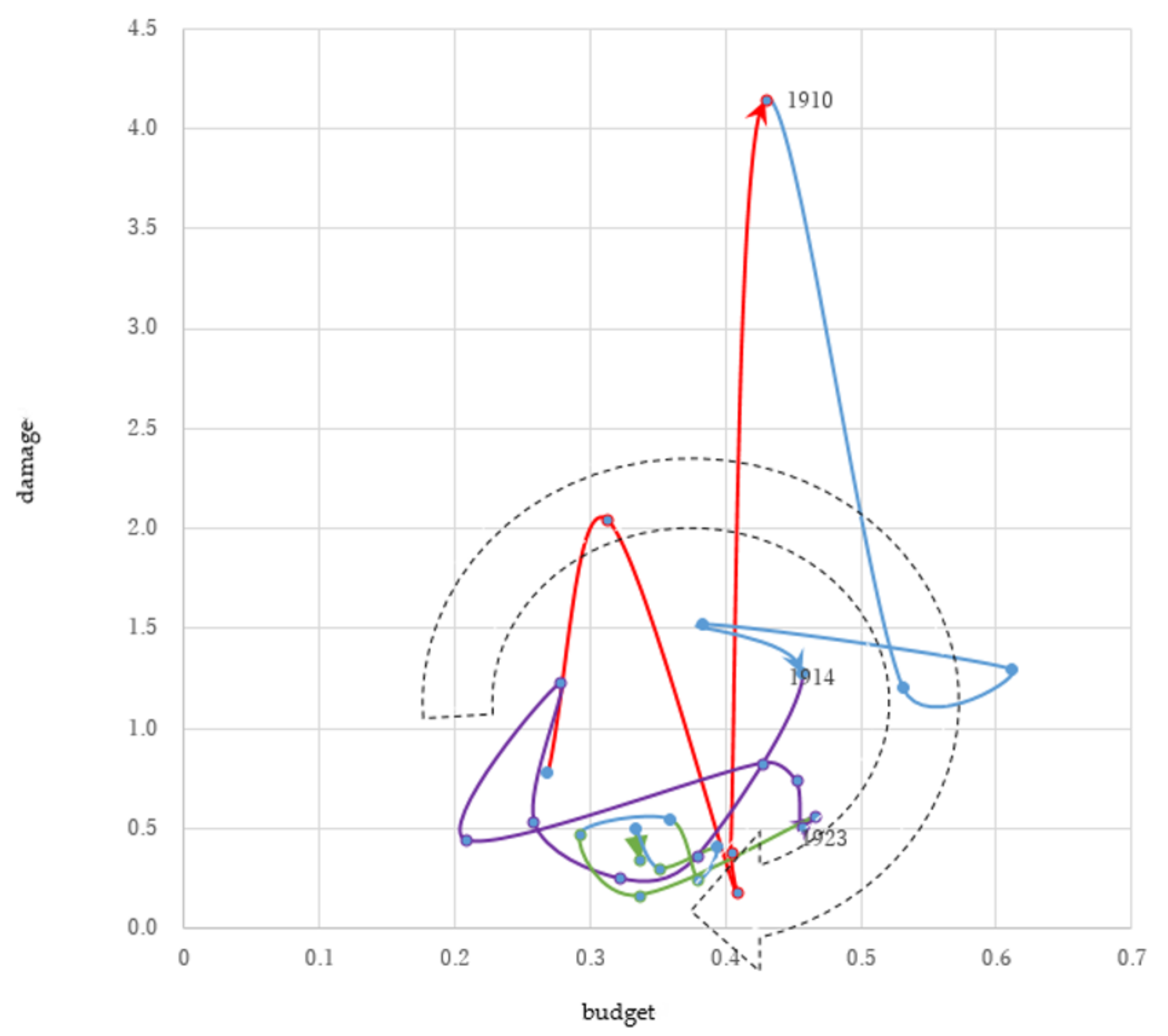

3.1.2. Constructing a Structural Framework in Major Rivers (1906–1931)

Increasing Damage (1906–1910)

Increasing Budget (1910–1914)

Decreasing Damage (1914–1923)

Decreasing Budget (1923–1931)

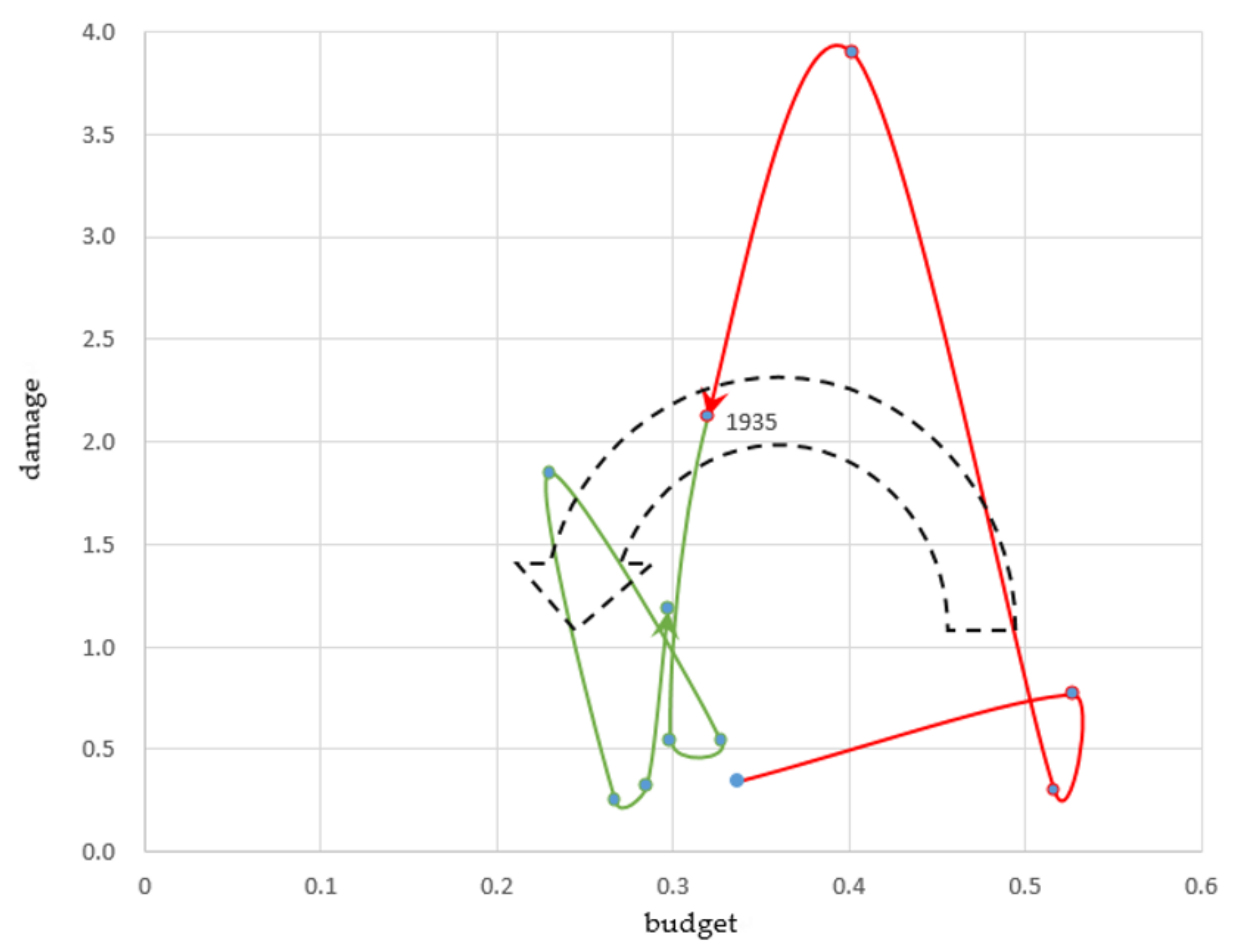

3.1.3. Wartime Regime (1931–1945)

Increasing Damage (1931–1935)

Decreasing Budget (1935–1945)

3.1.4. A Series of Flood Disasters (1945–1958)

Increasing Damage (1945–1947)

Increasing Budget (1947–1953)

Decreasing Damage (1953–1955)

Decreasing Budget (1955–1958)

3.1.5. Implementing Flood Protection during High Growth and Recession (1958–2014)

Increasing Damage (1958–1959)

Increasing Budget (1959–1982)

Decreasing Damage (1982–2000)

Decreasing Budget (2000–Present)

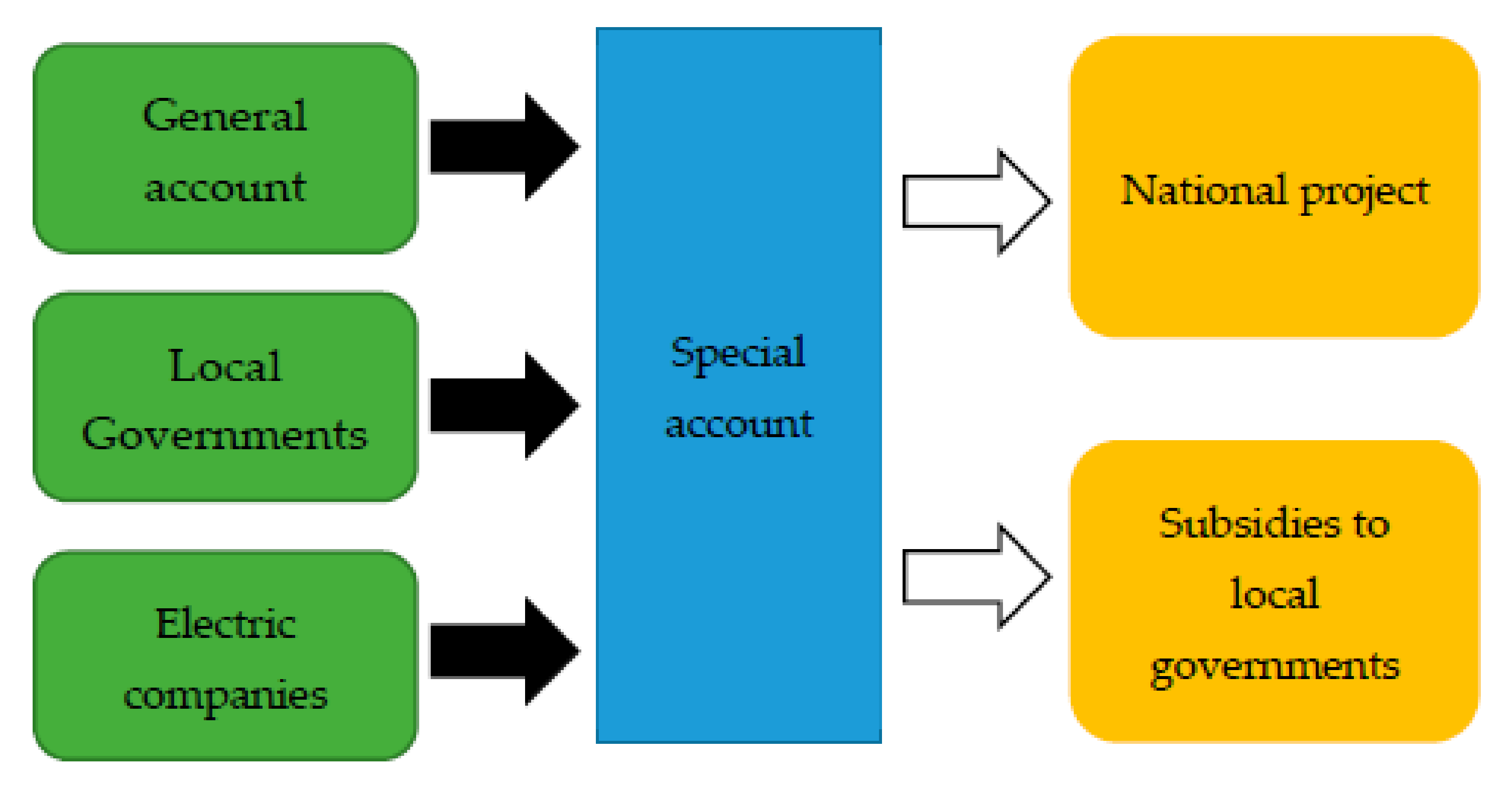

3.2. Mechanisms for Securing Budgets for Flood Protection

3.3. Implications of Fulfilling SFDRR Targets for Japan

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, R.; Shiwaku, K.; Gupta, R.D.; Nakano, G.; Shaw, R. Bangkok to Sendai and beyond: Implications for disaster risk reduction in Asia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2015, 6, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Surjan, A. Good enough today is not enough tomorrow: Challenges of increasing investments in disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2019, 1, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Sasaki, D. Investing in flood protection in Asia: An empirical study focusing on the relationship between investment and damage. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2021, 12, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Government of Japan. Voluntary National Review 2021 Report on the Implementation of 2030 Agenda: Toward Achieving the SDGs in the Post-COVID19 Era. 2021. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/28957210714_VNR_2021_Japan.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- UNISDR. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; UNSIDR: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Adeniyi, O.; Perera, S.; Collins, A. Review of finance and investment in disaster resilience in the built environment. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2016, 20, 224–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstra, D.; Thistlethwaite, J. Overcoming Barriers to Meeting the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction; Center for International Governance Innovation: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mizutori, M. Reflections on the Sendai Framework for disaster risk reduction: Five years since its adoption. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotayev, A.V.; Tsirel, S.V. A spectral analysis of world GDP dynamics: Kondratieff waves, Kuznets swings, Juglar and Kitchin cycles in global economic development, and the 2008–2009 economic crisis. Struct. Dyn. 2010, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Sasaki, D. Investments in Flood Protection: Trends in Flood Damage and Protection in Growing Asian Economies; JICA Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- Ishiwatari, M. Government Roles in Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction. In Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction; Shaw, R., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; pp. 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Takahasi, Y. History of water management in Japan from the end of world war II. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2009, 25, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takei, A. Research on Relationship between Technology and Institution in Flood Control in Japan; Kishimoto Syuppan: Kobe, Japan, 2017. (Original Work Published 1961); (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Takahasi, Y.; Uitto, J.I. Evolution of river management in Japan: From focus on economic benefits to a comprehensive view. Glob. Environ. Change 2004, 14, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajiwara, K. River Administration in Modern Japan: Deployment Policy and Legislation from 1868 until 2019; Horitsubunkasha: Kyoto, Japan, 2021. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, S.; Oki, T. Paradigm shifts on flood risk management in Japan: Detecting triggers of design flood revisions in the modern era. Water Resour. Res. 2018, 54, 5504–5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. Floods and Probability: Modern History of Technology and Society for Designed Flood Volumes; The University of Tokyo Publication: Tokyo, Japan, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, T. Evolution of Japan’s flood control planning and policy in response to climate change risks and social changes. Water Policy 2021, 23, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranghieri, F.; Ishiwatari, M. Learning from Megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake; World Bank Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, S.; Fujii, M. A study on the progress of the river administration from the consideration of Embankment Law in 1875 to the institution of River Law of 1896. Res. Civ. Eng. Hist. 1994, 14, 61–76. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari, M.; Sasaki, D. Bridging the Gaps in Infrastructure Investment for Flood Protection in Asia; JICA Research Institute: Tokyo, Japan, 2020.

- Shinohara, O. What Do Three Generations of River Engineers Have Seen? Koichi Ando, Yutaka Takahashi, Takashi Okuma, and Modern River Administration for 150 Years; Nobunkyo Production: Tokyo, Japan, 2018.

- Institute for International Cooperation. Disaster Management and Development: Improving Disaster Management Capacity of Society; JICA: Tokyo, Japan, 2003. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S.; Matsuura, S. Establishing the former River Law and River Administration (2). Suiri Kagaku 1996, 40, 51–78. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Editing Office of 100-Year History of Ministry of Finance. 100-Year History of Ministry of Finance; Ministry of Finance: Tokyo, Japan, 1969.

- Matsuura, S. The History of Making Long Term Flood Control Program and The Transition of its Basic Concept. Civ. Eng. Hist. Jpn. 1986, 6, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, S. Severe Flood Damage in 1910 and Settle Process of the First Long-Term Flood Control Program. J. Reg. Dev. Stud. 2008, 11, 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Umeda, M. The Background to Japan’s Overcoming Deflation in the Early 1930s: Exchange Rate Policy, Monetary Policy, and Fiscal Policy; Institute for Monetary and Economic Studies; Bank of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2005. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Forestry Agency. White Paper on Forest and Forestry; Forestry Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2014.

- Nishikawa, T. The History of Long-term plans for flood protection 4. Water Sci. 1965, 44, 128–151. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa, T. The long-term plans of river administration. Water Sci. 1961, 4, 122–138. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2016.

- Nakayasu, Y. Long-term plan for flood protection project. River 1962, 197, 2–3. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Takemura, K. The historical process of river administration during the period of modernization in Japan: Dam construction and environmental improvement. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 2007, 73, 103–107. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsuura, S. The River Policy for the Age of Rapid Economic Growth in Japan. Int. Reg. Study 2010, 13, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Okamura, J. History and importance of the river improvement and management long-term plan. River 2002, 673, 7–10. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari, M. What are crucial issues in promoting an integrated approach for flood risk management in urban areas? Jpn. Soc. Innov. J. 2016, 6, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nakamura, K. Nature-based solutions for river restoration in Japan. In Financing Investment in Disaster Risk Reduction and Climate Change Adaptation: Asian Perspective; Ishiwatari, M., Sasaki, D., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ishiwatari, M. Disaster Risk Reduction. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation; Lackner, M., Sajjadi, B., Chen, W.Y., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Commission on Large Dams. Dams in Japan: Past, Present and Future; CRC Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, E.J. Japan in 2001: A depressing year. Asian Surv. 2002, 42, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MLIT. White Paper on Land, Infrastructure and Transport; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2003.

- Prime Minister’s Office. Structural Reform and the Medium-Term Economic and Fiscal Perspectives. 2002. Available online: http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/kakugikettei/2002/0125tenbou.html (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Hasumi, R.; Iiboshi, H.; Nakamura, D. Trends, cycles and lost decades: Decomposition from a DSGE model with endogenous growth. Jpn. World Econ. 2018, 46, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDRR. Measuring Implementation of the Sendai Framework, Undated. Available online: https://sendaimonitor.undrr.org/ (accessed on 20 February 2022).

| (1) Damage Increase | (2) Budget Increase | (3) Damage Decrease | (4) Budget Decrease | Background | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disasters of Trigger (Share-of-NI) | Instruments to Increase (Share-of-NI) | Causes of Decrease | |||

| I Establishing a modernized mechanism of flood protection | |||||

| 1878–1906 | 1878–1896 | 1896–1899 | 1899–1901 | 1901–1906 | |

| 1896 flood (11) | River Law (0.9) | Russo-JPN War | Modernization & Industrialization | ||

| II Constructing structural framework in major rivers | |||||

| 1906–1931 | 1906–1910 | 1910–1914 | 1914–1923 | 1923–1931 | |

| 1907 & 1910 floods (4) | Long-term plan Special account (0.6) | Kanto Earthquake, Great Depression | Economic growth | ||

| III National land devastation in wartime regime | |||||

| 1931–1945 | 1931–1935 | 1935–1945 | |||

| 1934 Muroto Typhoon 1935 floods (4) | NA | NA | Sino-JPN War, WWII | Wartime regime | |

| IV Responding to a series of flood disasters | |||||

| 1945–1958 | 1945–1947 | 1947–1953 | 1953–1955 | 1955–1958 | |

| 1947, Kathleen typhoon (10) | Responding to major disasters (0.6) | Shift to transport & other sectors | a series of severe floods | ||

| V Implementing flood protection during high growth and recession | |||||

| 1958–2014 | 1958–1959 | 1959–1982 | 1982–2000 | 2000–2014 | |

| 1959 Isewan Typhoon (5) | Long-term plan Revising river law (0.9) | Economic Recession & Tight national budget | High growth & lost decades | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ishiwatari, M.; Sasaki, D. Disaster Risk Reduction Funding: Investment Cycle for Flood Protection in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063346

Ishiwatari M, Sasaki D. Disaster Risk Reduction Funding: Investment Cycle for Flood Protection in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(6):3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063346

Chicago/Turabian StyleIshiwatari, Mikio, and Daisuke Sasaki. 2022. "Disaster Risk Reduction Funding: Investment Cycle for Flood Protection in Japan" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 6: 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063346

APA StyleIshiwatari, M., & Sasaki, D. (2022). Disaster Risk Reduction Funding: Investment Cycle for Flood Protection in Japan. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3346. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063346