Abstract

Background: Knowledge about climate change may produce anxiety, but the concept of climate change anxiety is poorly understood. The primary aim of this study was to systematically review the qualitative literature regarding the scope of anxiety responses to climate change. The secondary aim was to investigate the sociodemographic and geographical factors which influence experiences of climate change anxiety. Methods: A systematic review of empirical qualitative studies was undertaken, examining the scope of climate change anxiety by searching five databases. Studies were critically appraised for quality. Content analysis was used to identify themes. Results: Fifteen studies met the inclusion criteria. The content analysis was organised into two overarching themes. The scope of anxiety included worry about threats to livelihood, worry for future generations, worry about apocalyptic futures, anxiety at the lack of response to climate change, and competing worries. Themes pertaining to responses to climate change anxiety included symptoms of anxiety, feeling helpless and disempowered, and ways of managing climate change anxiety. Relatively few studies were identified, with limited geographical diversity amongst the populations studied. Conclusions: The review furthers understanding of the concept of climate change anxiety and responses to it, highlighting the need for high-quality psychiatric research exploring its clinical significance and potential interventions.

1. Introduction

Climate change has been identified as one of the most pressing issues of our time, with major impacts on both physical and mental health [1]. Beyond the direct challenges that climate change poses to the determinants of mental health, such as threats to accessing basic needs (such as water, fresh air, food, and stable housing) and the trauma associated with extreme weather events, the broader psychological and emotional effects of climate change are increasingly being recognised [2,3,4]. This emerging field of study includes the interrelated phenomena of solastalgia, eco-anxiety, and ecological grief. Solastalgia, or the distress produced by the degradation of one’s home environment, was a concept first introduced by Albrecht [5], and it has been the subject of a growing body of literature since [6,7]. Ecological grief is a related concept, relating to grief experienced at ecological losses, i.e., to the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes [8,9]. Eco-anxiety has been defined by the American Psychological Association as “a chronic fear of environmental doom” [10].

Climate change anxiety has been proposed as the most recognised form of eco-anxiety [11]. It has been defined as “anxiety associated with perceptions about climate change”(p. 2) [12], which may involve cognitive, emotional, or functional impairment and somatic arousal (bodily symptoms) [13]. A related concept, climate change worry, involves negative or apprehensive thoughts about climate change that may be repetitive, difficult to control, or persistent [14]. Thus, worry may be a component of climate change anxiety. In recent years, climate change anxiety has become topical within mainstream media [15,16]. Climate change was the leading worry for Australians in a recent national media survey [17], and up to 80% of young people report being somewhat or very anxious about climate change [18]. Climate change anxiety has also been well recognised within the academic literature [11,12] and formal studies have found a similar prevalence of anxiety as the media surveys [19]. Despite increasing recognition, climate change anxiety remains an emerging concept that is in the early stages of being understood [12]. To date, we are not aware of any studies that have systematically examined the breadth of experiences comprising climate change anxiety, which is essential to furthering our understanding of this concept.

The aim of this systematic review is to explore the empirical qualitative literature examining the scope of climate change anxiety and the spectrum of responses to it. A secondary aim is to explore the factors influencing climate change anxiety. Qualitative methodologies are most appropriate to develop an in-depth understanding of a new phenomenon, as they explore subjective experiences and narratives in an open way [20]. Thus, this review focuses on studies using qualitative approaches in order to richly describe the nature and scope of anxiety in response to climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The review was conducted according to PRISMA reporting guidelines. A search of the published literature was performed using the databases Medline, PsychINFO, ProQuest, Web of Science, and Scopus. Search terms used were ‘climate change’ OR ‘global warming’ combined with ‘anxiety’ OR ‘worry’ OR ‘fear’ OR ‘eco-anxiety’. MESH Headings were utilised where possible. The search was limited to English-language papers utilising qualitative methodology to examine the psychological/emotional experiences of, and responses to, climate change that fell within the anxiety spectrum. Only empirical research published in peer-reviewed journals from January 2000 to August 22nd, 2020, was included. Duplicate citations were removed after the initial search.

The results of the database searches were initially screened by title and abstract by the first author. All articles potentially meeting the inclusion criteria (described below) were reviewed in full text. Where it was unclear whether an article met the inclusion criteria, it was discussed with the co-author until a consensus was reached.

To maximise the comprehensiveness of the search, citation chaining was performed on all papers that met the inclusion criteria to identify further relevant papers. In addition, three experts in the field of climate change and mental health were contacted for further recommendations.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Any studies that documented anxiety-related emotional or psychological experiences (e.g., anxiety, fear, worry) in relation to climate change using qualitative methodology (including mixed methods) were eligible for inclusion. Papers were included regardless of whether anxiety about climate change was the primary or secondary focus of the study, or an emergent finding. Studies of climate change worry, a component of climate change anxiety, were eligible for inclusion if they examined the nature and content of anxious cognitions about climate change.

Papers that examined anxiety responses to individual environmental phenomena (e.g., natural disasters, sea level rises, or environmental change within a specific landscape) were excluded. Although related, they are considered to be different phenomena to anxiety in response to the knowledge of climate change, which was the focus of this study. Papers studying perceptions of climate change that did not identify anxiety responses were also excluded, as were papers reporting only quantitative data. Opinion pieces, reviews, and grey literature were excluded from the review.

2.3. Quality Rating

Each paper that met the inclusion criteria was assigned a quality rating as per the guideline checklist developed by Attree and Milton [21]. This guideline describes a systematic rating scale for qualitative research papers. Each study is rated on criteria that include research background, aims and objectives, context, appropriateness of design, sampling, data collection and analysis, reflexivity, value of the research, and ethics. A total score is assigned based on the grade for the majority of sections. Studies receiving ‘A’ scores have no or few flaws, ‘B’ have some flaws, ‘C’ have considerable flaws but are still of some value, and ‘D’ scores have significant flaws that threaten the validity of the study as a whole.

Each paper was analysed and scored independently by both authors. Where assigned scores differed, there was discussion of ratings until a consensus was reached. As per Attree and Milton’s recommendations, papers with a score of D were excluded from the analysis [21].

2.4. Data Extraction and Thematic Analysis

Data were extracted independently by both authors. The standardised form for data extraction included study details (author, year, country of study), aim, design and methodology, participants and setting, anxiety themes identified, other themes identified, factors influencing the emotional or psychological experience of climate change, and quality rating, with comments on methodological factors.

A thematic analysis was conducted by the lead author. The methodology followed the six phases described by Braun and Clarke [22], using a process of inductive analysis. Using this technique, data are coded and themes are derived directly from the data presented, without pre-conceived themes and with a broad research question [22]. The phases included familiarisation with the data by reading and re-reading the texts, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. Emergent themes were discussed with the co-author until a consensus was reached. Themes were revised iteratively in light of new data until the final themes and sub-themes were established.

3. Results

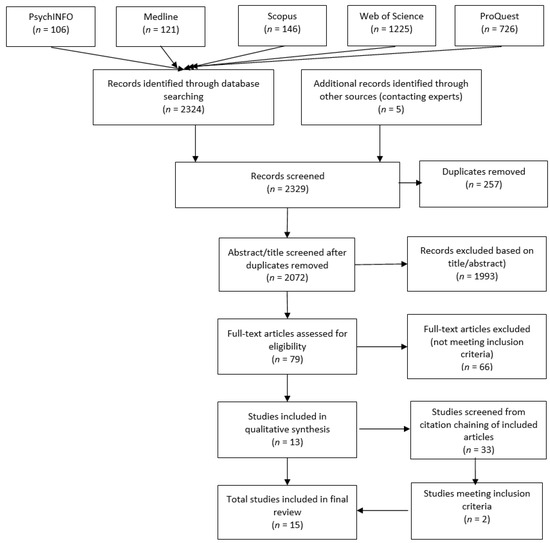

The PRISMA diagram outlines the search process and selection of papers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.1. Study Characteristics

A total of 15 studies met the inclusion criteria [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. The study information and detailed findings are presented in Table 1. Four studies were conducted in North America [24,26,29,30], three in Australia [25,33,35], two in Norway [31,34], and one each from South Korea [23], Sweden [37], Ghana [32], and Tuvalu [27]. One study was conducted across four nations (Fiji, Cyprus, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom) [36] and one study did not identify its origin [28]. The majority of studies (10/15) were published in the previous five years. All but one [37] focused on adults, though the two Norwegian studies included a small number of teenagers within groups of predominantly adult participants [31,34].

Table 1.

Description of included studies, thematic analysis, and quality ratings.

Six of the papers were purely qualitative and the other nine used mixed methods (see Table 1). The stated goals of the studies were variable; nine sought to study mental wellbeing and emotions in the context of climate change [24,27,28,29,30,31,35,36,37], and six explored broader perceptions of climate change [23,25,26,32,33,34]. Two studies included quantitative measures of distress and anxiety [27,29]. Five studies predominantly investigated for, or identified, climate change anxiety [23,27,28,29,35], whereas ten studies focused on responses more consistent with climate change worry [24,25,26,30,31,32,33,34,36,37].

Five studies scored the highest quality rating of A, five were rated B and four were rated C (see Table 1). A single study [31] was rated D and was thus excluded from the analysis.

3.2. Thematic Analysis

The results of the systematic review were divided into two broad areas of understanding about climate change anxiety; namely, (i) the “scope of climate change anxiety”, i.e., what was the specific reason for or focus of anxiety, and (ii) “responses to climate change anxiety”, which included emotional responses and ways of coping with anxiety (Table 1). Multiple themes emerged for each and are presented below. Results for the secondary aim, to explore the factors influencing climate change anxiety, are also provided in Table 1.

3.2.1. Themes Related to the Scope of Climate Change Anxiety

A number of key themes emerged regarding the focus of climate change anxiety, which included worry about threats to livelihood, worry for future generations, worry about apocalyptic futures, anxiety at the perceived lack of response to climate change, and competing worries.

Worry about Threats to Livelihood

Disruptions to livelihood were a source of anxiety in many studies [24,26,27,29,30,36]. Threats to daily life identified by participants included adverse economic changes, migration, extreme weather events, and lack of disaster preparedness. Many feared the loss of access to resources resulting in water scarcity, disruptions to food supplies and crop production, and impacts on local agriculture and the economy. Villagers in Fiji were concerned that:

“Maybe in the future our plants can’t grow and we have to go buy them from the market”[36] (p. 105)

Water scarcity was a concern in a lakeside community in Canada:

“You need water, like you can’t survive without that so I do worry about…access to clean water”[26] (p. 78)

Financial worries were the most prominent for the predominantly male farmers interviewed in America:

“as with most, my worries generally stem from financial stress”[29] (p. 91)

Several studies highlighted concern about climate change-related migration. This included people who anticipate being forced to migrate:

“I know I’ll be leaving soon, but when news comes that Tuvalu is affected or will sink, it makes me cry. Because I was born here, I’m Tuvaluan”[27] (p. 4)

In contrast, in countries less immediately threatened by climate change, such as the United Kingdom, the worry related to how to accommodate incoming climate refugees [36].

The increased frequency of extreme weather events and their links to livelihoods was a concern in Wisconsin:

“I’m afraid we’re really gonna start getting hit with like massive tornadoes. That’s my biggest fear”[30] (p. 6)

There were divergent subthemes of “opportunity” and “already adapted”. Some perceived new livelihood opportunities related to the changing climate. A respondent in the fishing village of Kodiak, Alaska, was optimistic:

“A disaster for some may mean prosperity for others – as polar ice melts, we might benefit as more shipping traffic comes through this area”[24] (p. 292)

The business opportunities presented by the challenges of climate change were emphasised by sustainability consultants in corporations in Australia:

“Answering the challenge and being part of the climate change solution can have a multitude of immediate and long-term benefits for business”[35] (p. 1572)

Some people did not perceive threats to their way of life, as they had “already adapted”. For example, among farmers in Ghana, there was a degree of confidence about adapting to environmental change, which seemed to mitigate against anxiety:

“Let’s face it, people have already seen extreme weather events in the past. Very bad ones. So they keep finding innovative ways of dealing with the weather changes. That’s why we are aware but don’t generally worry about environmental changes”[32] (p. 52)

Worry for Future Generations

Worry about future generations was a prominent theme in more developed countries [24,26,29,34,36]. The uncertainty of what sort of world would be left for children and grandchildren was a source of distress. For example, a participant in Ontario, Canada, stated:

“We are actually taking our planet on a crash course and as a grandmother, I am deeply, deeply, deeply concerned about this. I have a one-year-old granddaughter now. You know we are leaving nothing for her”[26] (p. 80)

A divergent subtheme regarding worry for future generations was that of hope. Future generations were seen as a source of hope and potential solutions amongst young people in South Korea:

“Hope may come from education”[23] (p. 67)

Worry about Apocalyptic Futures

For some, climate change was a “frightening scenario” [34] (p. 784) that evoked anxiety. “Catastrophe” and “apocalypse” were amongst the single words chosen to describe how participants felt about climate change in an American study [30] (p. 4). Students in South Korea associated climate change with doomsday scenarios they had seen in the media:

“Something like this will happen to humans; we cannot prevent destroying the earth…we will die”[23] (p. 68)

Anxiety at the Perceived Lack of Response to Climate Change

The failure of others to take action was a source of anxiety. Participants felt that climate change could only be talked about in certain groups, which increased their anxiety [23,30,35], and not everyone shared the participants’ worries:

“The first thing I associate when I hear climate change is terrified, you know. People don’t think it exists, or it’s happening, or nobody is going to do anything about it”[30] (p. 5)

Gaining Perspective—Competing Worries

Some participants struggled to place climate change amongst multiple other more pressing concerns in their daily life [30,32,33,34]. This was true in Western cultures, such as Wisconsin, USA:

“There’s so much to be worried about, it’s diluted you know, what we have time to talk about”[30] (p. 5)

However, the awareness of competing worries was particularly true of participants in areas where resources were already scarce. Grape growers in Australia identified multiple financial and political stressors that they placed ahead of climate change:

“Climate change is the least of my worries”[25] (p. 6)

Amongst Yolgnu people in Arnhem Land, Australia, local social and ecological issues, such as mining and observed seasonal changes, were highlighted as more immediate concerns than anthropogenic climate change which, in fact, was barely mentioned [33]. Climate change was not viewed as a separate entity from other worries, but was perceived as interwoven and likely to exacerbate existing worries, which, as in Ghana [32], were deemed to be much more important than climate change.

3.2.2. Themes in Responses to Climate Change Anxiety

A spectrum of responses to climate change anxiety emerged, including symptoms of anxiety, the feelings of helplessness and disempowerment that climate change anxiety evoked, and finally a complex theme encompassing the ways of managing climate change anxiety. Distancing and avoidance, taking action, fostering support, adapting, and actively choosing optimism and hope were themes regarding strategies employed to manage climate change anxiety.

Symptoms of Anxiety

Participants described worry about climate change in ways that were consistent with symptoms of clinical anxiety. This included feelings of suffocation [23], panic amongst climate change activists [28], and rumination on negative emotions of guilt and worry [37]. In Tuvalu, residents described disturbed sleep, poor concentration, inability to relax, and other effects on function related to anxiety about climate change:

“Sometimes I want to sleep, but I can’t because those thoughts about climate change keep popping up…thoughts about this distract me from my study”[27] (p. 4)

Feeling Helpless and Disempowered

People across Europe [34,36], North America [24,30], Australia [25], and in Tuvalu [27] described a sense of powerlessness and feeling overwhelmed. They did not know what to do to tackle the problem of climate change, feeling individual measures were futile, which led to feelings of depression and anxiety:

“I feel that you resign a little, this is too big. This makes you feel like: Help, what can you do other than trouble yourself?”[34] (p. 785)

Disempowerment was a strong theme amongst South Australian grape growers, where there was distrust of climate change information because:

“some of the information is too extreme, so if those projections happen we’re finished anyway”[25] (p. 7)

Managing Climate Change Anxiety

Five themes emerged describing strategies to manage climate change anxiety.

- Distancing and avoidance

A key theme which emerged as a way to manage climate change anxiety was distancing and avoidance. Some saw climate change as something geographically and temporally distant, which was protective against anxiety [24]. Some downplayed the seriousness of climate change to alleviate worry, such as this university student in Norway:

“I do not think it [global warming] is as human-made…as it allegedly is, according to the tabloids…I do not think it is as bad as they want to describe it”[34] (p. 789)

Even those who engage with climate change on a daily basis in their work made conscious decisions to distance themselves from climate change anxiety. For activists, this was a key step in resolving feelings of crisis brought on by knowledge of climate change:

“I barely think about climate change now. It’s in the background of my life all the time, but I rarely sit and actually talk about climate change or read very much about it”[28] (p. 230)

Climate scientists and sustainability managers both emphasised rationality in their daily work, managing emotions by restricting or compartmentalising. However, this approach to coping related to emotions in general and not anxiety specifically:

“I think a lot of scientists convey the impression that they have no feelings at all about these issues”[28] (p. 236)

- b.

- Taking action

A move towards action was another strategy that was used to manage worry about climate change. Young people in Sweden took actions, such as researching solutions and modifying behaviour, to cope with climate change anxiety [37]. Amongst farmers in the USA, “taking action” was linked to a sense of resilience:

“Action, not worry, solves the problem”[29] (p. 91)

This sentiment was echoed by climate activists who developed a sense of agency that allowed them to move forward:

“Action is the antidote to despair”[28] (p. 229)

- c.

- Fostering support

Actively seeking support was an important theme that emerged in young people [37] and in the specific population of climate change activists who were dealing with overwhelming feelings about climate change [28]. The activists consciously held positive ideas about the future and identified the importance of a network of practice and culture of self-care:

“We build into it after the event, doing something where we talk about the emotions of how to deal with that”[28] (p. 234)

- d.

- Adapting

Developing confidence in the ability to adapt to climate change appeared to be linked to a sense of resilience. This was seen in general community members in America:

“There are so many things we don’t know. We adapt. We’ve always adapted”[24] (p. 291)

Confidence about adaptation was particularly found in groups of farmers in the USA [29] and in Ghana [32]. These farmers appeared to be accustomed to adaptation, and this flexibility allowed them to deal with depressed and anxious feelings:

“I see the changes and how they are affecting my farm but I am changing how I am farming in response to climate change rather than being depressed by it”[29] (p. 91)

- e.

- Optimism and hope

Actively choosing to be optimistic and hopeful were responses used to manage climate change anxiety [23,24,26,35,37]. Focus on positive emotions was notable amongst young people in Sweden [37]. Positive reappraisals of the problem, positive thinking, and fostering existential hope were subthemes identified in the Swedish youth:

“You have to feel hope to make things any better. If no one felt hope then you might as well give up”[37] (p. 547)

Focus on solutions and trust in science, policy, and environmental groups, amongst others, also helped young people cope with anxiety:

“Because a lot of people are working, planting new trees, dealing with the waste and exhaust fumes from cars”[37] (p. 549)

Hope was also harnessed by sustainability managers in their daily work in Australian corporate environments:

“I guess I’ve always been a bit of an optimist and you have to be in this game. I’ve got a hope in terms of human ingenuity that we all trade out of this somehow”[35] (p. 1569)

3.2.3. The Intersection of Anxiety, Sadness, and Solastalgia

Parallel to climate change anxiety, people described feelings of sadness and loss that were difficult to separate from their experiences of worry [23,24,27,30,36]. They repeatedly referred to local changes observed in their environment, which were seen as personal experiences of climate change. A loss of culture and community was a source of both anxiety and sadness in Fiji:

“Seeing the changes makes me feel sad because people are not engaged…in helping protect the village and community”[36] (p. 105)

Changes in landscapes and seasons were referred to with a sense of loss in Korea:

“Now I do not feel spring or fall weather as much now...I feel like I lost something”[23] (p. 68)

The emotional impact of local environmental change was strongly felt amongst Indigenous Yolgnu people in Arnhem Land, Australia, with their unique connection to the land:

“What we are doing to mother nature. Mother nature is now weeping”[33] (p. 686)

4. Discussion

The aims of this systematic review were to qualitatively explore the scope of climate change anxiety as a concept and to investigate the spectrum of anxiety responses to climate change. A secondary aim was to explore the factors influencing climate change anxiety. This systematic review of the qualitative literature contributes to our understanding of this important, understudied topic. A qualitative approach is best suited to develop an in-depth understanding of new concepts, such as climate change anxiety [20]).

The scope of anxiety about climate change was broad. The majority of studies explored aspects of climate change worry, a component of climate change anxiety. The review identified that “worry about threats to livelihood” was a major concern across all populations, with a breadth of focus from anxiety about access to food and water, to anxiety about finances, population movement, and natural disasters. It is surprising that no known previous study has explored the specific focus of climate change anxiety in a quantitative manner, despite numerous studies measuring the prevalence of climate change anxiety [19,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], and studies assessing the scope of environmental worries beyond climate change [13,47,48,49]. The theme of “worry about future generations” has been identified previously [50], as have correlations between parenthood and anxiety about climate change [41]. In this study, “worry about future generations” was more prominent amongst Western countries [24,26,29,34,36], where participants tended to perceive climate change as a future rather than current threat. Anxiety about “apocalyptic futures” is likely to be found in those with egalitarian beliefs, who have higher perceptions of catastrophe related to climate change [38].

The systematic review revealed patterns in the demographic characteristics of participants and climate change anxiety, addressing the secondary aim of this study. The key factors influencing emergent themes for the scope of climate change anxiety were vulnerability to climate change, socioeconomic factors, and occupation (Table 1). Four of the twelve studies included participants from either developing countries (Fiji, Ghana, Tuvalu) or disadvantaged socioeconomic groups (Arnhem Land, Australia). These participants are arguably amongst the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change [1]. Despite their high vulnerability, two of these studies identified a relative lack of anxiety or worry about climate change [32,33] when compared to more developed nations in North America and Europe [24,26,30,34]. There are several potential explanations for this finding. In Arnhem Land, it was noted that Western concepts of climate change were very poorly understood [33]. Further, more immediate concerns about day-to-day survival were prominent there and in Ghana, giving rise to the theme of “competing worries”. Amongst populations already struggling to survive on the land, climate change can be seen as “yet another stressor” [51] (p. 1). In Tuvalu, by contrast, knowledge of climate change is strong, exemplified by the commonly known trope that “Tuvalu is sinking” [27] (p. 2). Consistent with this, very high levels of climate change anxiety were found in Tuvaluan residents [27], reflecting the level of threat that climate change poses to this island nation [52].

Occupation emerged as a likely influence upon the scope of anxiety about climate change. In North America, farmers (in a predominantly white male participant group) identified financial concerns about the impact of climate change [29]. Grape growing farmers in Australia showed a comparative lack of worry about climate change, as they were more concerned with perceived immediate stressors, such as farming costs and viability, alongside scepticism about the existence or seriousness of climate change [25]. Other farming populations have been demonstrated to hold higher rates of scepticism, with associated lower rates of worry about climate change, than the general public [43,53]. The present review also found that farmers in Ghana have little anxiety about climate change, as they are confident in their ability to adapt [32].

A gender-related difference in the scope of anxiety might be expected, given that women often experience higher levels of climate change anxiety than men [54,55,56]. However, the impact of gender on the scope of anxiety was not well explored by the reviewed studies. Only one study noted that women were more likely to worry about future generations, while men worried more about finances [24]. It was not possible to identify any patterns relating to age and the scope of anxiety, as the only paper that specifically studied young people assessed only responses to climate change anxiety, not the scope of anxiety [50]. Given the disproportionate impact of climate change on young people, further study in this population is needed.

The second group of themes that emerged in this review were the responses to climate change anxiety, which ranged from “symptoms of anxiety”, to “feeling helpless and disempowered”, and “managing climate change anxiety: distancing and avoidance”, “taking action”, “fostering support”, “adapting”, and “optimism and hope”. The proximity to the effects of climate change corresponded with anxiety responses. “Symptoms of anxiety”, and the subsequent impact on daily function, were described by Tuvaluan citizens [27], who arguably face the most tangible threat from climate change. Similarly, the proximity of climate change activists to the realities of climate change threats precipitated feelings of panic [28], whereas such intense experiences of anxiety were less evident in other populations studied within this review. Feeling “helpless and disempowered”, however, in the face of anxiety about climate change, was a phenomenon commonly expressed across diverse geographical locations [24,25,27,28,30,34,36]. It is likely that this emotion is influenced by individual ontological belief systems, which have been shown to mediate feelings of helplessness in association with climate change anxiety [38].

This review did not reveal any clear factors influencing the particular ways of managing climate change anxiety. Compared to factors influencing the scope of climate change anxiety, it is likely that responses to anxiety (including worry specifically) are less influenced by characteristics, such as gender, location, or social group, but by individual psychological factors and ontological beliefs [39,40,57]. Further, the significant heterogeneity of climate change understanding, perception, and engagement in populations across the world is an ongoing challenge for research [54,57]. “Fostering support” and “distancing and avoidance” have small but significant effects on lessening the experience of psychological distress related to climate change [58]. Among 12-year-olds and adolescents, higher levels of worry were found in those who used “problem-focused coping”, where one focuses on ways to solve the problem, such as searching for information [50,59]. It was suggested that 12-year-olds who emphasised the positive affects of optimism and hope may be buffered against negative affects, including worry about climate change [59]. The importance of hope is increasingly recognised within the climate change literature as a part of psychological adaptation and as a way of overcoming difficult emotions associated with knowledge of climate change [60,61].

4.1. Solastalgia and Sadness

In this review, solastalgia and sadness emerged as key affects linked to climate change anxiety. Whilst quantitative results demonstrate that anxiety and sadness are frequently the two most common emotional responses to climate change [24,27], the qualitative approach of this paper highlights how closely these emotional states are interconnected, just as in clinical populations [62]. The experience of solastalgia and its relevance amongst Indigenous peoples is particularly recognised [7,63,64] and was also found in this study [33].

4.2. Clinical Implications

This review highlights the spectrum of anxiety people may experience in relation to climate change, and their responses to those anxieties. Worry, a cognitive component of climate change anxiety, was most commonly explored in these studies. Clinical presentations related to climate change anxiety have not been well elucidated, although they have been recognised in psychotherapeutic spaces [65] and at an obsessive compulsive disorder treatment clinic [66]. The treatment of eco-anxiety, a closely related concept, is an emerging area of research [67]. Evidence of clinical symptoms of anxiety emerged as a small but important theme in this review of the qualitative literature. Quantitative studies in this area report mixed results [19,46,68,69,70], but convincing evidence of a link between climate change anxiety and clinical anxiety is currently lacking. A survey of primary care patients in America identified a link between climate change concern and dysphoria, but no link to anxiety [70]. Another survey of Australian university students and community members found a small association between climate change distress and depression, and a moderate correlation between climate change distress and future worry [19]. Perceived ecological stress predicted depressive symptoms in a survey of parents in America [69]. None of these studies could demonstrate causation in either direction. Other studies have found no significant correlation between worry about climate change or ecology and psychiatric morbidity from anxiety [46,68].

An alternative view is that climate change anxiety is not a clinical entity, but rather an existential one [11]. The argument for understanding climate change anxiety as an existential worry, rather than a pathological worry of the kind recognised by psychiatry, is reflected by the fact that only two of the fifteen papers were published in medical or psychological journals [27,29]; the remainder appeared in environmental or sociological journals. Further, concern exists about pathologizing climate change anxiety, which has been described as a proportionate emotional response to the current environmental situation [12,60]. However, the descriptions of anxiety symptoms, associated distress, and impacts on behaviours and functioning that emerged from this qualitative review should not be ignored.

Further research is required to identify people who are vulnerable to experiencing climate change anxiety at a level of clinical significance and who may benefit from intervention. Validated screening tools, such as the Environmental Distress Scale [71] or the scale developed by Clayton and Karazsia [13], may be helpful. People who screen positive for climate change anxiety may benefit from intervention. However, there is a dearth of literature guiding approaches to its management [67]. A recent scoping review highlighted emerging approaches to treating eco-anxiety, including both individual and group work, predominantly underpinned by ecotherapy, psychoanalysis, and Jungian depth psychology [67]. Notably, only two of the reviewed studies empirically evaluated their psychotherapeutic approach, emphasizing the need for more study [67].

Not all studies of the perceptions of climate change have identified anxiety within the spectrum of responses [25,32,42]. Further study is required to determine the reasons behind this, be they methodological or cohort based. Other emotional responses to climate change, such as anger, guilt, and hope, are likely to have their own patterns and associations [72] and require further study to determine their clinical significance and how they intersect with climate change anxiety.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Included Papers

Few of the papers explored participants’ knowledge and understanding of climate change, which may affect the reliability of results—why worry about something that you do not believe exists? In the two papers that did measure belief in climate change, it was as low as 58% in one study population [25], and showed significant variation (55–88%) between subsets of participants in another [24]. Another study included expressions of scepticism about the seriousness of the climate change threat [34]. In the study by Petheram and colleagues, it became clear to researchers that there were significant misconceptions about notions of climate change, and participants’ worry increased as they were educated over the course of the study [33]. Multiple other studies have highlighted the poor knowledge and understanding of climate change concepts [44], particularly in the developing world [73,74,75,76]. Knowledge of climate change can also be mediated by factors, such as media exposure, which is positively related to the experience of climate change anxiety [77], though its influence was not captured in any of the papers in this review.

The quality of the included studies must be considered. One third of the studies were rated A (no or few flaws), one third were rated as B (containing some flaws), and four of the fifteen were rated C (considerable flaws but still of some value). More weight should be placed on the results from studies of higher quality. Reflexivity and ethics were particularly poorly addressed by the studies, perhaps because many were conducted within ethnographic rather than clinical research frameworks. Additionally, several studies were limited by inadequate sampling [23,28,30,34,35] and a limited application of techniques for validating results [23,24,26,30,34,35,36,37].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

Strengths of this review include a thorough literature search intended to capture any study that included qualitative data on climate change anxiety (including worry), even where this was not a goal of the original study. The heterogenous populations and varied aims and methodology of the included studies were well suited to an exploratory qualitative approach.

Regarding limitations, the findings of this review may not be generalisable given the relatively small number of studies and the importance of location and population to understanding concepts of climate change anxiety that emerged in the analysis. The exclusion of grey literature and other unpublished papers may have limited the results through publication bias [78]. The terms used to identify the spectrum of anxiety responses were not exhaustive; for example, the word “concern” was excluded from the literature search as it returned a prohibitive number of titles for review (over 25,000). Finally, the distinction between climate change anxiety and climate change worry was not always clearly delineated, both within the individual reviewed studies and consequently in the broader thematic analysis of the systematic review. This highlights the need for clarity and standardization of the concept of climate change anxiety.

5. Conclusions

Climate change anxiety is becoming recognised as one of the mental health effects of climate change. This review has identified a broad scope of worries about climate change, and a diversity of responses to this anxiety. Characteristics, such as occupation, socio-economic status, and proximity to climate change, appear to be important influences on climate change anxiety and related responses. The review furthers our understanding of the concept of climate change anxiety and highlights the need for future studies of this phenomenon to be conducted by clinical researchers. There is a pressing need to better understand the psychological and functional effects of climate change anxiety and to examine interventions to promote resilience and reduce clinically significant distress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S. and A.P.F.W.; methodology, C.S. and A.P.F.W.; validation, A.P.F.W.; formal analysis, C.S. and A.P.F.W.; investigation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S.; writing—review and editing, A.P.F.W.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, A.P.F.W.; project administration, C.S. and A.P.F.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Costello, A.; Abbas, M.; Allen, A.; Ball, S.; Bell, S.; Bellamy, R.; Friel, S.; Groce, N.; Johnson, A.; Kett, M. Managing the health effects of climate change: Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet 2009, 373, 1693–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Bowen, K.; Kjellstrom, T. Climate change and mental health: A causal pathways framework. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritze, J.G.; Blashki, G.A.; Burke, S.; Wiseman, J. Hope, despair and transformation: Climate change and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2008, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovich, N.; Migliorini, R.; Paulus, M.P.; Rahwan, I. Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10953–10958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, G.; Sartore, G.-M.; Connor, L.; Higginbotham, N.; Freeman, S.; Kelly, B.; Stain, H.; Tonna, A.; Pollard, G. Solastalgia: The distress caused by environmental change. Australas. Psychiatry 2007, 15, S95–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askland, H.H.; Bunn, M. Lived experiences of environmental change: Solastalgia, power and place. Emot. Space Soc. 2018, 27, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P.; Beery, T.; Jones-Casey, K.; Tasala, K. Mapping the solastalgia literature: A scoping review study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Harper, S.L.; Minor, K.; Hayes, K.; Williams, K.G.; Howard, C. Ecological grief and anxiety: The start of a healthy response to climate change? Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, e261–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S. Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 74, 102263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Karazsia, B.T. Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 69, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.E. Psychometric properties of the climate change worry scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.; Murray, J. ‘Overwhelming and Terrifying’: The Rise of Climate Anxiety. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/feb/10/overwhelming-and-terrifying-impact-of-climate-crisis-on-mental-health (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Ward, M. Climate Anxiety Is Real, and Young People Are Feeling It. Available online: https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/health-and-wellness/climate-anxiety-is-real-and-young-people-are-feeling-it-20190918-p52soj.html (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Crabb, A. Australia Talks National Survey Reveals What Australians Are Most Worried about. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-10-08/annabel-crabb-australia-talks-what-australians-worry-about/11579644 (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- ReachOut. New Survey by ReachOut and Student Edge Reveals Number of Students Anxious about Climate Change. Available online: https://about.au.reachout.com/blog/new-survey-by-reachout-and-student-edge-reveals-number-of-students-anxious-about-climate-change (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Searle, K.; Gow, K. Do concerns about climate change lead to distress? Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2010, 2, 362–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Attree, P.; Milton, B. Critically appraising qualitative research for systematic reviews: Defusing the methodological cluster bombs. Evid. Policy A J. Res. Debate Pract. 2006, 2, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelcev, G.; Chung, M.-Y.; Sar, S.; Duff, B.R. A ZMET-based analysis of perceptions of climate change among young South Koreans: Implications for social marketing communication. J. Soc. Mark. 2015, 5, 56–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bray, M.V.; Wutich, A.; Brewis, A. Hope and Worry: Gendered Emotional Geographies of Climate Change in Three Vulnerable US Communities. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2017, 9, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, A.; Dowd, A.-M.; Gaillard, E.; Park, S.; Howden, M. “Climate change is the least of my worries”: Stress limitations on adaptive capacity. Rural Soc. 2015, 24, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galway, L.P. Perceptions of climate change in Thunder Bay, Ontario: Towards a place-based understanding. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 68–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, K.; Barnett, J.; Haslam, N.; Kaplan, I. The mental health impacts of climate change: Findings from a Pacific Island atoll nation. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 73, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoggett, P.; Randall, R. Engaging with climate change: Comparing the cultures of science and activism. Environ. Values 2018, 27, 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Ahmed, S.; Lachapelle, P.; Schure, M.B. Farmer and rancher perceptions of climate change and their relationships with mental health. J. Rural. Ment. Health 2020, 44, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemkes, R.J.; Akerman, S. Contending with the nature of climate change: Phenomenological interpretations from northern Wisconsin. Emot. Space Soc. 2019, 33, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. “People want to protect themselves a little bit”: Emotions, denial, and social movement nonparticipation. Sociol. Inq. 2006, 76, 372–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H.; Bezner-Kerr, R. The relative importance of climate change in the context of multiple stressors in semi-arid Ghana. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 32, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petheram, L.; Zander, K.K.; Campbell, B.M.; High, C.; Stacey, N. ‘Strange changes’: Indigenous perspectives of climate change and adaptation in NE Arnhem Land (Australia). Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryghaug, M.; Holtan Sørensen, K.; Næss, R. Making sense of global warming: Norwegians appropriating knowledge of anthropogenic climate change. Public Underst. Sci. 2011, 20, 778–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C.; Nyberg, D. Working with passion: Emotionology, corporate environmentalism and climate change. Hum. Relat. 2012, 65, 1561–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bray, M.V.; Wutich, A.; Larson, K.L.; White, D.D.; Brewis, A. Emotion, coping, and climate change in island nations: Implications for environmental justice. Environ. Justice 2017, 10, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change? Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Bellamy, R.; Hulme, M. Beyond the tipping point: Understanding perceptions of abrupt climate change and their implications. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2011, 3, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T.; Verschoor, M.; Albers, C.J.; Böhm, G.; Fisher, S.D.; Poortinga, W.; Whitmarsh, L.; Steg, L. When worry about climate change leads to climate action: How values, worry and personal responsibility relate to various climate actions. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 62, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Yang, J.Z. Emotion and the psychological distance of climate change. Sci. Commun. 2019, 41, 761–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekholm, S.; Olofsson, A. Parenthood and worrying about climate change: The limitations of previous approaches. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fløttum, K.; Dahl, T.; Rivenes, V. Young Norwegians and their views on climate change and the future: Findings from a climate concerned and oil-rich nation. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 1128–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareau, B.J.; Huang, X.; Gareau, T.P. Social and ecological conditions of cranberry production and climate change attitudes in New England. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfautsch, S.; Gray, T. Low factual understanding and high anxiety about climate warming impedes university students to become sustainability stewards: An Australian case study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2017, 18, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reser, J.; Bradley, G.; Glendon, A.; Ellul, M.; Callaghan, R. Public Risk Perceptions, Understandings, and Responses to Climate Change and Natural Disasters in Australia and Great Britain; National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility: Gold Coast, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verplanken, B.; Roy, D. “My worries are rational, climate change is not”: Habitual ecological worrying is an adaptive response. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, A.; Balkaya, N. An assessment of the perspectives of university students on environmental issues in Turkey. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2017, 26, 5271–5282. [Google Scholar]

- Çimen, O.; Yılmaz, M. Environmental worries of teacher trainees. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 15, 2214–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Karatekin, K. Perception of environmental problem in elementary students’ mind maps. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Coping with climate change among adolescents: Implications for subjective well-being and environmental engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furberg, M.; Evengård, B.; Nilsson, M. Facing the limit of resilience: Perceptions of climate change among reindeer herding Sami in Sweden. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 8417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, J.; Adger, W.N. Climate dangers and atoll countries. Clim. Change 2003, 61, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; O’Neill, M.A. Climate change from the perspective of Spanish wine growers: A three-region study. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.B.; Palm, R.; Feng, B. Cross-national variation in determinants of climate change concern. Environ. Politics 2019, 28, 793–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muttarak, R.; Chankrajang, T. Who is concerned about and takes action on climate change? Gender and education divides among Thais. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 2015, 13, 193–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundblad, E.-L.; Biel, A.; Gärling, T. Cognitive and affective risk judgements related to climate change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Moser, S.C. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2011, 2, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P.; Glendon, A.I.; Ellul, M.C. Distress and coping in response to climate change. In Stress and Anxiety: Applications to Social and Environmental Threats, Psychological Well-Being, Occupational Challenges, and Developmental Psychology Climate Change; Logos Verlag Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, K.; Blashki, G.; Wiseman, J.; Burke, S.; Reifels, L. Climate change and mental health: Risks, impacts and priority actions. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2018, 12, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Monroe, M.C. Exploring the essential psychological factors in fostering hope concerning climate change. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineka, S.; Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 377–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, K.E.; Westoby, R. Solastalgia and the gendered nature of climate change: An example from Erub Island, Torres Strait. EcoHealth 2011, 8, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willox, A.C.; Harper, S.L.; Edge, V.L.; Landman, K.; Houle, K.; Ford, J.D. The land enriches the soul: On climatic and environmental change, affect, and emotional health and well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada. Emot. Space Soc. 2013, 6, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseley, D. Climate change: Clinical considerations. Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Stud. 2019, 16, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.K.; Wootton, B.M.; Vaccaro, L.D.; Menzies, R.G. The impact of climate change on obsessive compulsive checking concerns. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2012, 46, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudon, P.; Jachens, L. A scoping review of interventions for the treatment of eco-anxiety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, H.L.; Peel, D. Worrying about climate change: Is it responsible to promote public debate? BJPsych Int. 2015, 12, 31–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, S.V.; Pollitt, A.; Barnett, M.A.; Curran, M.A.; Craig, Z.R. Differentiating environmental concern in the context of psychological adaption to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 48, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temte, J.L.; Holzhauer, J.R.; Kushner, K.P. Correlation between climate change and dysphoria in primary care. WMJ 2019, 118, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham, N.; Connor, L.; Albrecht, G.; Freeman, S.; Agho, K. Validation of an environmental distress scale. EcoHealth 2006, 3, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Bray, M.; Wutich, A.; Larson, K.L.; White, D.D.; Brewis, A. Anger and sadness: Gendered emotional responses to climate threats in four island nations. Cross-Cult. Res. 2019, 53, 58–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Lama, A.K.; Espiner, S. The cultural context of climate change impacts: Perceptions among community members in the Annapurna Conservation Area, Nepal. Environ. Dev. 2013, 8, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iniguez-Gallardo, V.; Bride, I.; Tzanopoulos, J. Between concepts and experiences: Understandings of climate change in southern Ecuador. Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 29, 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kittipongvises, S.; Mino, T. The influence of psychological factors on global climate change perceptions held by the rural citizens of Thailand. Ecopsychology 2013, 5, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghariya, D.P.; Smardon, R.C. Rural perspectives of climate change: A study from Saurastra and Kutch of Western India. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 23, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D.A.; Begotti, T. Media Exposure to Climate Change, Anxiety, and Efficacy Beliefs in a Sample of Italian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterbrook, P.J.; Gopalan, R.; Berlin, J.; Matthews, D.R. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991, 337, 867–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).