Abstract

Background: The aim of the present work is the elaboration of a systematic review of existing research on physical fitness, self-efficacy for physical exercise, and quality of life in adulthood. Method: Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines, and based on the findings in 493 articles, the final sample was composed of 37 articles, which were reviewed to show whether self-efficacy has previously been studied as a mediator in the relationship between physical fitness and quality of life in adulthood. Results: The results indicate that little research exists in relation to healthy, populations with the majority being people with pathology. Physical fitness should be considered as a fundamental aspect in determining the functional capacity of the person. Aerobic capacity was the most evaluated and the 6-min walk test was the most used. Only one article shows the joint relationship between the three variables. Conclusions: We discuss the need to investigate the mediation of self-efficacy in relation to the value of physical activity on quality of life and well-being in the healthy adult population in adult life.

1. Introduction

Today’s developed society is subject to great changes, not always of a positive nature, some of which seem to impact health, well-being, and especially the prolongation of life. Staying healthy is important and has an impact on healthy lifestyle [1].

1.1. Quality of Life in Adulthood

Adulthood is a period of the life cycle that differs widely due to socio-economic, labor, and cultural conditions. Although it can cover a wide range of ages, current scientific convention specifies an age span that begins between the ages of 40–45 and ends between the ages of 60–65, at which point we can speak of the beginning of old age [2,3]. During the process of adult maturity, important body changes take place or have already taken place, such as menopause and andropause, which involve diverse psychological impacts and, frequently, physiological changes. A loss of bone mass, for example, reduces the strength of the body, making it more vulnerable an injury or disease in daily life [4,5]. People are not always aware of these changes [6,7,8,9,10]. Recently, although there seems to be some interest among the population in understanding the keys to maintaining health and quality of life and to face the decline or deterioration that occurs in old age with better physical and mental health [11], the sedentary life continues to affect a wide range of the adult population [12].

1.2. Active Life as a Quality of Life Enhancer

A review study [13] indicated that moderate and systematic physical activity is one of the factors that most affects quality of life. During childhood and adolescence, physical activity is academically programmed, and the habit of physical activity is regulated by schooling, with varying degrees of effectiveness and quality. In old age, health systems and community medicine usually incorporate guidelines that recommend moderate physical activity, with advice on the value of walking, swimming, or going to gyms and social health centers. These efforts, sometimes, are not always successful. However, during the mature adult years [14] that precede old age, the adult population seems to be under pressure from work and family responsibilities, leaving little time for personal attention to preventive health and well-being needs. Some research [15] has revealed the challenge of practicing physical activity or sport in this period of the life cycle. The responsibilities of early adulthood are self-regulated by the experience and years of mature adulthood, and it is at this stage that the practice of physical activity and/or sport for optimal fitness becomes a challenge, because it is known to benefit the individual’s overall health [16,17].

1.3. Physical Fitness as an Indicator of Quality of Life

Related to active living and physical exercise is the concept of physical fitness, a well-known and powerful health marker [18,19,20] among middle-aged populations, it is even more powerful than physical activity [7] but we must understand physical fitness as a concept broader than one related exclusively to biological health; it can be defined as the ability to carry out daily tasks with vigor and liveliness, without excessive fatigue, and with enough energy remaining to enjoy leisure time or to cope with unexpected emergencies [21]. Therefore, in addition to being related to biological health, physical fitness is also closely related to psychosocial factors on the human spectrum and has been found to influence fitness parameters [22]. However, few studies present data associating physical fitness in adults with it is psychosocial benefits. It is known that, as a method of achieving general well-being, physical fitness has a large regulated role in the negative relationship between the sedentary life and quality of life [23]. Thus, knowing the levels of physical fitness can be an important tool in providing specific advice to the population in relation to their well-being [24].

However, although it is known that physical activity and improved physical fitness generate benefits and play a fundamental role in both biological and psychological well-being [8,10], it cannot be taken for granted that adults currently incorporate it into their daily routines [8,10].

1.4. The Role of Self-Efficacy in Maintaining an Active Life

The self-evaluation that is carried out on one’s own activities is called self-efficacy [25]. Expectations of self-efficacy refer to beliefs about personal abilities and the ability to satisfactorily carry out the necessary demands in different situations [26]. Losses inherent to the aging process, such as those related to physical functioning, can affect how one believes in one’s control, or loss of control of self-efficacy [2]. Fortunately, the practice of physical exercise can alleviate these consequences [19]. However, even though people understand the beneficial effects of healthy habits on their own bodies and on their overall well-being and health, we are not sure if there is reciprocity between this knowledge and the integration of physical exercise into their life routines [27].This may seem a paradox in relation to classical theories of motivation towards physical exercise, which emphasize the role of rationality in the decision-making process [28]. It is here that the concept of self-efficacy for physical exercise becomes important, since it determines in part one’s motivation to practice physical activity and is one of its most powerful predictors [29].

1.5. The Present Study

As a result of these considerations, empirical evidence suggests the important role that the relationship between self-efficacy and the practice of physical activity and exercise performance can play; however, the relationship and influence between self-efficacy and quality of life in terms of physical fitness during mid-life remains relatively limited and therefore does not provide clarifying results. Furthermore, this relationship appears to be very important if we consider that physical fitness is a factor intimately related to well-being and quality of life, as well as a quantitative aspect of each person’s physical functioning—functioning that declines as one ages, therefore, analysis of the relationship between these constructs appears to be an interesting hypothesis for a systematic review. To this end, the general objective of this study was to carry out an exhaustive review of the existing literature delve deeper into this topic. In particular, a specific objective that was established, review the measurement instruments for the specific variables.

2. Material and Methods

We selected articles in the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycINFO, database presenting research results on the relationship between quality of life, physical fitness, and exercise self-efficacy in the adult population. They were chosen because they are the largest and most recognized base of abstracts and bibliographic references in the scientific literature worldwide. This search and analysis was conducted from March to October to July 2020.

We used a pattern of argument follow-up based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol [30], which is recommended for the development of bibliographies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, where all works included in the journals in the Journal Citation Report (quartiles 1, 2, 3) and the SCImago Journal Rank (quartiles 1 and 2) were examined.

The exhaustive review of each of the articles was managed according to author, title of article, year of publication, language, URL and/or DOI of publication, indexation of the journal, publication location, city or region of the study, number and type of sample, average age of participants, objective(s), methodology, analyses performed, measuring instruments, and techniques used.

The search terms used were: “Exercise” and “Physical Fitness” and “Self Concept” and “Self Efficacy” and “Quality of Life”, and a combination of these with the Boolean operator “AND” under the guidelines of PubMed and with the filter belonging to the PubMed database itself, limiting the age stage to “middle-aged”. The following search combinations were used: “Exercise and Physical Fitness and Self Concept and Quality of Life”, “Exercise and Physical Fitness and Self Efficacy and Quality of Life”, “Exercise and Exercise Test and Self Concept and Quality of Life”, “Exercise and Exercise Test and Self Efficacy and Quality of Life”. Criteria for the inclusion of articles were: (a) the average age of participants was within the range of 40–70 years (in the case of articles that included this data, the criterion <70 years was accepted); (b) that they were empirical articles, or (c) they were articles from bibliographical reviews. The screening of articles was done manually, and the selected papers were included in a general table (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the item selection process.

3. Results

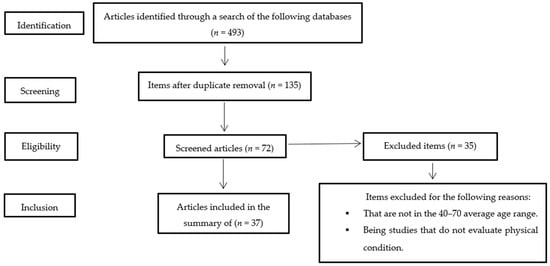

Figure 1 presents all the articles that were selected for this systematic review. Of the 37 articles reviewed focused on clarifying the relationship between fitness parameters and exercise self-efficacy, 32 articles were focused on populations with some type of pathology [6,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Five articles focused on the pathology-free middle-aged population [62,63,64,65,66]. The results obtained from the articles included in this review are shown in the Table 2 section below.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection for the systematic review.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the selected studies.

3.1. Results of Studies Assessing Overall Physical Fitness

Assessing physical fitness was the main objective for 12 articles, while it was secondary in 12 articles. In relation to the measurement of the instruments used, different tests have been found for the evaluation of physical fitness, of which some are general and others, specific. On 24 occasions, the test used was “The 6-Min Walk Test” (6MWT) that assesses aerobic endurance Self-perceived physical fitness was assessed on 14 occasions [6,34,37,39,40,43,47,53,56,58,59,61,65,66]. “The Foot Up and Go” test was used on six occasions [34,42,48,54,55,62]; “The Sit to Stand Test” [34,39,46,57,61,62]; “The Handgrip forced test” was used to evaluate the strength of the upper and lower body, agility in the face of possible falls, flexibility of the upper and lower body, and dynamic balance [39,42,46,57,61,63]. In five occasions “Treadmill Test” was used [6,45,60,63,64]. “The 10-Min Walk Test” (10MWT) assessing endurance was used on three occasions [40,48,50]. On two occasions the VO2 peak was evaluated with “The Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale” [45,54]; “The Naughton Protocol” [6,47]. the “Arm Curl Test” [39,62]. In two examples these tests were used: “The test “Sit and Reach” [62,63]; “The Grip Strength Test” [53,57]; The Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale” (ABC Scale) [42,50]. On one occasion, the VO2 peak was assessed with “the Balke Protocol” [65]; “The Bicycle Ramp Protocol” [54]; “The Discontinuous Arm Crank” [38]; “The Submaximal Bicycle Ergometer” [46]; “1-Repetition Maximum Free Weight Bench Press” [38]; “The Timed Stair Climbing” [43]; “Hip Flexibility” [63]; “Functional Aerobic Impairment” (FAI) [6]; “50 Foot Flat Surface Walking Test” [43]; “Berg Balance Scale” (BBS) [48]; “The 14-item Mini Balance Evaluation Systems Test” (Mini-BESTest) [42]; “Well bench” [61].

3.2. Results of Studies Assessing Self-Efficacy

In 15 articles, self-efficacy was assessed as a secondary objective. On three occasions, the following instruments were used: “The Arthritis Self- Efficacy Scale” [34,43,53]; “The 16-items Cardiac Exercise Self-Efficacy” [6,54,55]; “ABC Scale” [42,50,66]. Furthermore, the following instruments were used one two occasions: “The Exercise Self-Efficacy Scale” [45,46]. On one occasion “The Self-Efficacy Questionnaire-Walking” (SEQ-W) [49] and “The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) Self-Efficacy Scale” [52] were used. On one occasion, the following instruments were used: “The New General Self-Efficacy Scale” [63]; “8-ítems measure of beliefs capabilities” [65]; “The Physical Activity Self-Efficacy” [64]; “Self-efficacy in Leisure-Time Physical Activity” (LIVAS) [39]; “Self-Rated Abilities for Health Practices Scale” (SRAHP) [38]; “Fear of Falling Efficacy Scale” (FFES) [48]; “Self-Monitor Exercise Behavior” (SMEB) [31]; Likert Scales [62]; “General Self Efficacy Scale” (GSES) [56]; 16-Item Heart Disease Self Efficacy Scale (HDSE) [60].

3.3. Results of Studies Assessing Quality of Life

Quality of life has been evaluated with different instruments, 13 articles used “The SF-36 Health Questionnaire” [6,31,32,35,36,38,41,43,44,45,53,60,61]; On three occasions, the following were used: The SF-12 Health Questionnaire” [42,51,55]; “The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form” (The MOS SF36) [44,47,52]. On two occasions “Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire” (The MLHFQ) [54,55]; “The EuroQol Five-Dimensions Questionnaire” (EQ-5D) [46,56]; “The St. George Respiratory Questionnaire” (SGRQ-TS) [39,44]; “Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire”(CRQ) [36,49]; “The European Organization for Research and Training, Quality of Life Questionnaire—Core 30” (The EORTC QLQ-C30) [57,64]; “The World Health Organization Quality of Life questionnaire” (WHOQOL-BREF) [40,59] were evaluated.

On one occasion we used: “Self-Administered Quality of-Well-Being Scale” (The QWB-SA) [44]; “Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System-Short Form” (CARES-SF) [62]; “The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire” (FIQ) [32]; “Stroke Impact Scale–16” (SIS-16) [50]; “The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-8” (PDQ-8) [48]; “The Kidney Disease Quality of Life” (KDQOL-36) [51]; “The Quality of Well-Being Scale” (QWB) [49]; “The Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire” [58].

4. Discussion

To find the relationship between physical fitness, the role of self-efficacy in physical exercise and physical exercise, and quality of life in the middle-aged population, the systematic review analyzed in detail works published on physical fitness, self-efficacy, and quality of life from 1997 to July 2020. The minimum age of the subjects was 30 years and the maximum age was 80, since there were studies whose age is between these values, even though the average age of the subjects studied was between 40 and 70 years old. A systematic search of the literature was carried out and 37 articles focusing on explaining these relationships were identified. Our results allow us to confirm that there is a relationship between the three explored constructs (physical fitness, quality of life, and self-efficacy in terms of improved health and healthy habits, although the relationship between the three variables in a related way is not entirely clear.

The results have shown that, although there is scientific production that attends to the relationship between the three variables, in most cases the population evaluated is a population with some pathology. Only in some cases was the evaluated population free of pathologies [62,63,64,65,66] that a variation of the levels of physical fitness affects to the behavior in relation to the barriers towards the physical exercise and of the style of life of the population in consonance as they indicate authors as [50,62]. This is especially relevant since identifying the pathology-free population that regularly exercises and tries to achieve and/or maintain good levels of physical fitness that is one of the main objectives of the current study [67]. All this, together with the novelty of the subject of analysis, means that this subject of study has yet to be clarified and delimited, hence its importance.

On a methodological level, the samples used for the studies was somewhat small: only one study [44] used a sample of 1631 participants, while the others had samples of fewer than 250 subjects. This is due mainly to the fact that these studies were interventions or programs development studies of populations with very specific characteristics; fewer descriptive studies analyze the relationships between the variables under study. This requires us to be cautious when considering the results of the reviewed studies.

The assessment, through evidence, of the capacities that support the physical fitness should be considered as a fundamental aspect in determining the functional capacity of the person. The physical fitness represents a significant influence on the quality of life associated with health, this being a key component in the quality of life [18,19,20]. In relation to the physical fitness variables studied, 30 articles assessed aerobic endurance, and 24 of these used the resistance test called The 6 Min Walk Test. Cardiorespiratory capacity is the main indicator of the subject’s state of physical fitness, with maximum oxygen consumption (VO2peak) being the physiological variable that best defines it in terms of cardiovascular capacity. It has been shown that a low level of physical fitness constitutes a major cardiovascular risk factor [67,68] and is a strong and independent factor in all causes of death [69]. In relation to strength, the following were evaluated: general muscle strength; lower body strength; maximum muscle strength of the muscles that mobilize the hand, knee, and elbow; grip strength; maximum strength; maximum grip strength; knee strength; muscle power. It should be noted that various transversal and longitudinal studies have verified that strength decreases with age [70,71], and this decrease is significant starting in the 50s for women and in the 30s or 40s for men [72,73]. It would therefore be advisable to introduce strength exercises into physical activity programs to slow down the process of loss of muscle mass.

On the other hand, given that many of the gestures of daily life require extensive articular paths, this capacity facilitates the functional independence of the person. For this reason, flexibility should be included in recommendations for physical exercise in this phase of life. Flexibility has been evaluated in a small number of studies, although flexibility of the lower and upper body was also assessed [41,61,62,63]. General mobility, walking and leg mobility, and agility have also been evaluated [34,40,42,43,48,50,54,62]. Static and dynamic equilibrium, which are affected by the progressive loss of sensory-motor function caused by increasing age, were assessed in several studies [42,43,48,53,55,66].

In summary, several studies in this review focused their efforts on understanding what makes a person more consistent in their active exercise behaviors. Many of these, through different types of intervention programs, have shown how increased health perception is linked to increased awareness of personal health status and associated with improved levels of physical fitness [46,50], improved behavior and enhanced adherence [31,39,46,53], and tolerance of sports behavior [6]. Therefore, knowledge of fitness levels can be an important tool in providing specific advice to the population [45]. Being aerobic capacity the most valued capacity and the 6-Min Walk Test the most used.

4.1. Self-Efficacy, Fitness, and Quality of Life

Empirical evidence supports the link between exercise self-efficacy and predictions of a variety of health-related behaviors [74,75]. The importance of physical inactivity for public health in the adult population underscores the importance of identifying those physical activity mediators and moderators that can be targeted for interventions to increase physical activity levels [76], being self-efficacy a powerful mediator between physical abilities and physical activity performance [66]. In this review, four articles focused on showing the relationship between physical fitness and exercise self-efficacy, three of which showed a positive relationship between both variables [33,47,55], while on one occasion no relationship was shown between the two [35]. Showing therefore greater tendency that supports the assertions of Bandura [77] that the actual performance of a skill is partially dependent on the perceived ability of the individual to undertake and persist in the achievement of that skill. For example, by limiting the barriers to physical exercise that lead to abandonment or non-participation [50]. These results are consistent with the findings of other studies in which exercise self-efficacy is postulated as a powerful indicator of measures of functional and reflex change in an individual’s physical fitness. It is also a determinant in the relationship between physical activity and various aspects of quality of life, including physical and mental health status and life satisfaction [23,66,78,79]. It is therefore desirable to understand in greater depth how to improve self-efficacy towards physical exercise [55].

One’s general sense of well-being—being aware of and feeling healthy and adjusted to one’s environmental conditions—seems to be an important requirement for developing self-awareness and a satisfying quality of life. Three studies in this review corroborated the relationships between the physical fitness variable and the quality of life variable [33,35,50]. Only Cameron-Tucker’s [35] study showed an absence of association between physical fitness and quality of life. These relationships are important because physical condition is a powerful marker of health and quality of life [20] and well-being [24], so it would be very interesting to learn more about these relationships, which have been little studied in the literature. For example, in subjects with chronic stroke, the increase in the number of steps correlates with increases in perceived physical function as a measure of quality of life [50]. On the other hand, if we take into account the importance of the dimensions evaluated for quality of life in middle age and in relation to the other variables analyzed, it should be noted that middle-aged women present more work-family complications and less social support as their perceived benefits of physical fitness increase [80]. It was also found that, among men, low mobility was associated with a lower quality of life in the psychological health domain. This is very important because increased dependence on others and reduced work capacity can be a major challenge for many men [81].

In the studies analyzed, no results have been found that analyze the relationships between the three variables, only the relationships between them two to two, and simply in one [33], the relationships between a measure of exercise self-efficacy and quality of life are analyzed, finding relationships between the 6MWT physical condition test is positively and significantly correlated with walking self-efficacy and with SF-36 physical Subscale but not with mental subscale. But it has not been analyzed, for example, the mediating role that self-efficacy or physical condition can have in relation to quality of life.

4.2. Review of Instruments and Measures

In relation to the instruments used in this review, 18 articles evaluated self-efficacy for physical exercise; these focus primarily on evaluating pre-behavioral processes such as change of behavior towards exercise [33,39,49], confidence in designated change towards exercise behavior [6,45,47,54,55], self-perceived capacity to develop sports behavior [45,51], confidence in designated change towards exercise behavior [6,54,55], social support for exercise behavior [46], and self-perceived barriers to exercise behavior [62,65]. Specifically, all of these results are related to Pender contributions, which link healthy behavior to the likelihood of engaging in it and one’s sense of self-efficacy. He proposed that self-efficacy for physical exercise has a decisive influence on health behavior, perceived barriers, and commitment to a plan of action [82]. During adulthood there is a slight decline in levels of self-efficacy and mastery, and these influence the perception that there are obstacles to achieving new goals [83]. Therefore, it is essential to improve beliefs about the effectiveness of physical exercise and to promote healthy behavior in the long term.

Quality of life was evaluated with different instruments. Eleven articles used “the SF-36 Health Survey”, a questionnaire that provides a clear understanding of what is being measured, how it is used, and the implications for future use. It includes most of the essential concepts for the evaluation of the general health status. It has also proved to be suitable for cross-cultural applications but may be too long for clinical use. In addition, its scoring method is more complicated. The Chronic Respiratory Questionnaire (CRQ), which is one of the available instruments to measure the general health-related quality of life in patients with chronic respiratory condition, and which has been translated into different languages [84]. On 3 occasions the SF-12 Health Questionnaire was evaluated. The SF-12 represents a plausible alternative to the SF-36 for measuring health status, showing only a minimal loss in measurement accuracy in comparation with SF-36 [85]. Other questionnaires analyzed in the results have been used on fewer occasions [46,54,55,56].

A relevant and conclusive aspect of our review is that a large variety of articles included intervention processes, the results of which focused on checking the possible effects of such interventions on the variables of physical fitness, self-efficacy, and quality of life. These results allow us to assume that, in most cases, the interventions that encourage on physical exercise programs offer benefits for physical fitness, self-efficacy, and quality of life when compared with the control groups, even throughout the follow-up time.

5. Conclusions

One of the main conclusions of this work is that the important role played by physical fitness and self-efficacy for physical exercise in achieving levels of well-being and quality of life in middle-aged and senior adults. Although one article [33] showed a positive relationship between the three reviewed constructs, the relationships between them are not completely clear. While there is no unanimity on the effects of these variables, it has been found that they are clear predictors of health, they benefit behavioral change, and they have a close relationship that can be mutually influenced. Since current research should try to identify variables that measure and moderate the practice of physical activity in the adult population, these data provide us with vital information that will allow us to deal with the serious problem of physical inactivity in favor of public health [76].

With the objective of promoting integral health, we should raise awareness that prevention should begin before disease appears [86]. However, one of the difficulties among the middle-aged population is lack of time, which undermines this link between personal cultivation and healthy habits. As for the limitations of the study, we should highlight the large age range of the samples examined—a result of the scarcity of studies dealing with this vital period. Likewise, most of the studies we examined referred to subjects with some kind of pathology. Finally, we would add that physical fitness and self-efficacy show a positive relationship, which is important in well-being at this age.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.O.-R., and M.d.R.M.-U.; methodology, M.d.R.M.-U., J.d.D.B.-S., R.O.-R.; article search and screening, M.d.R.M.-U., validation, J.d.D.B.-S., R.O.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, M.d.R.M.-U., J.d.D.B.-S., R.O.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.d.D.B.-S., R.O.-R., M.d.R.M.-U.; visualization, J.d.D.B.-S.; supervision, R.O.-R.; funding acquisition, R.O.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interests.

References

- Caldas de Almeida, J.M.; Mateus, P.; Frasquilho, D.; Parkkonen, J. EU COMPASS for Action on Mental Health and Wellbeing; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, M.E.; Jette, A.; Tennstedt, S.; Howland, J.; Harris, B.A.; Peterson, E. A cognitive-behavioural model for promoting regular physical activity in older adults. Psychol. Health Med. 1997, 2, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Lewkowicz, C.; Marcus, A.; Peng, Y. Images of midlife development among young, middle-aged, and older adults. J. Adult Dev. 1994, 1, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Mecías, J.S.; Marín, F.; Vila, J.; Díez-Álvarez, A.; Abizanda, M.; Álvarez, R.O.; Gimeno, A.S.; Pegenaute, E. Prevalencia de factores de riesgo de osteoporosis y fracturas osteoporóticas en una serie de 5.195 mujeres mayores de 65 años. Med. Clín. 2004, 123, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tenover, J.L. Testosterone replacement therapy in older adult men. Int. J. Androl. 1999, 22, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, E.; Langbein, W.E.; Dilan-Koetje, J.; Bammert, C.; Hanson, K.; Reda, D.; Edwards, L. Effects of exercise training on aerobic capacity and quality of life in individuals with heart failure. Heart Lung J. Acute Crit. Care 2004, 33, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne, I.J.; Ades, P.A.; Poehlman, E.T. Impact of cardiovascular fitness and physical activity level on health outcomes in older persons. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2003, 124, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jürgens, I. Práctica deportiva y percepción de calidad de vida. Rev. Int. Med. Y Cienc. Act. Física Y Deporte 2006, 6, 62–74. [Google Scholar]

- Pressman, S.D.; Matthews, K.A.; Cohen, S.; Martire, L.M.; Scheier, M.; Baum, A.; Schulz, R. Association of enjoyable leisure activities with psychological and physical well-being. Psychosom. Med. 2009, 71, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejeski, W.J.; Brawley, L.R.; Shumaker, S.A. Physical activity and health-related quality of life. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 1996, 24, 71–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhee, J.S.; French, D.P.; Jackson, D.; Nazroo, J.; Pendleton, N.; Degens, H. Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology 2016, 17, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavie, C.J.; Ozemek, C.; Carbone, S.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Blair, S.N. Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 799–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramirez-Vélez, R. Actividad física y calidad de vida relacionada con la salud: Revisión sistemática de la evidencia actual. Rev. Andal. Med. Deporte 2010, 3, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cornachione Larrinaga, M.A.A. Psicología Del Desarrollo Adultez: Aspectos Biológicos, Psicológicos y Sociales, 1st ed.; Brujas: Córdoba, Argentina, 2006; p. 298. [Google Scholar]

- Cattanach, L.; Tebes, J.K. The nature of elder impairment and its impact on family caregivers’ health and psychosocial functioning. Gerontologist 1991, 31, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis, A.J. Determinants of a health-promoting lifestyle: An integrative review. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, A.M.; Wilson, D.K.; Lee Van Horn, M. Longitudinal relationships between self-concept for physical activity and neighbourhood social life as predictors of physical activity among older African American adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häuser, W.; Bernardy, K.; Arnold, B.; Offenbächer, M.; Schiltenwolf, M. Efficacy of multicomponent treatment in fibromyalgia syndrome: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Arthritis Care Res. 2009, 61, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Harmer, P.; McAuley, E.; John Fisher, K.; Duncan, T.E.; Duncan, S.C. Tai Chi, Self-Efficacy, and Physical Function in the Elderly. Prev. Sci. 2001, 2, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskemann, J.; Hummler, S.; Diepold, C.; Keil, M.; Abel, U.; Steindorf, K.; Beckhove, P.; Ulrich, C.M.; Steins, M.; Thomas, M. POSITIVE study: Physical exercise program in non-operable lung cancer patients undergoing palliative treatment. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.J.; Powell, K.E.; Christenson, G.M. Physical Activity, Exercise and Physical Fitness Definitions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.L.; Nichols, J.F.; Pakiz, B.; Bardwell, W.A.; Flatt, S.W.; Rock, C.L. Relationships between cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity, and psychosocial variables in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2010, 17, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Konopack, J.F.; Motl, R.W.; Morris, K.S.; Doerksen, S.E.; Rosengren, K.R. Physical activity and quality of life in older adults: Influence of health status and self-efficacy. Ann. Behav. Med. 2006, 31, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez-López, F.; Gray, C.M.; Segura-Jiménez, V.; Soriano-Maldonado, A.; Álvarez-Gallardo, I.C.; Arrayás-Grajera, M.J. Independent and combined association of overall physical fitness and subjective well-being with fibromyalgia severity: The al-Ándalus project. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy; Ramachaudran, V.S., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 1982, 37, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Krishnan, A. What Predicts Exercise Maintenance and Well-Being? Examining The Influence of Health-Related Psychographic Factors and Social Media Communication. Health Commun. 2019, 34, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekkekakis, P.; Dafermos, M. Exercise is a Many-Splendored Thing, but for Some It Does Not Feel So Splendid: Staging a Resurgence of Hedonistic Ideas in the Quest to Understand Exercise Behavior; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Everett, B.; Newton, P.J.; Salamonson, Y.; Davidson, P.M. Self-efficacy: A useful construct to promote physical activity in people with stable chronic heart failure. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. PRISMA declaration: A proposal to improve the publication of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Med. Clínica 2010, 135, 507–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, K.J.; Little, J.P.; Jung, M.E. Self-Monitoring Using Continuous Glucose Monitors with Real-Time Feedback Improves Exercise Adherence in Individuals with Impaired Blood Glucose: A Pilot Study. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2016, 18, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, A.S.; Villela, A.L.; Jones, A.; Natour, J. Effectiveness of dance in patients with fibromyalgia: A randomised, single-blind, controlled study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2012, 30 (Suppl. 74), 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Belza, B.; Steele, B.G.; Hunziker, J.; Lakshminaryan, S.; Holt, L.; Buchner, D.M. Correlates of Physical Activity in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Nurs. Res. 2001, 50, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, T.; Siersma, V.; Magnusson, S.P.; Kjaer, M.; Christensen, H.E.; Beyer, N. In hip osteoarthritis, Nordic Walking is superior to strength training and home-based exercise for improving function. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2017, 27, 873–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron-Tucker, H.L.; Wood-Baker, R.; Owen, C.; Joseph, L.; Walters, E.H. Chronic disease self-management and exercise in COPD as pulmonary rehabilitation: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Copd 2014, 9, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donesky-Cuenco, D.A.; Nguyen, H.Q.; Paul, S.; Carrieri-Kohlman, V. Yoga therapy decreases dyspnea-related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A pilot study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2009, 15, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstain, A.; Lebel, S.; Chasen, M.R. An interdisciplinary palliative rehabilitation intervention bolstering general self-efficacy to attenuate symptoms of depression in patients living with advanced cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2016, 24, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froehlich-Grobe, K.; Lee, J.; Aaronson, L.; Nary, D.E.; Washburn, R.A.; Little, T.D. Exercise for everyone: A randomized controlled trial of project workout on wheels in promoting exercise among wheelchair users. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2014, 95, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hospes, G.; Bossenbroek, L.; Ten Hacken, N.H.T.; Van Hengel, P.; de Greef, M.H.G. Enhancement of daily physical activity increases physical fitness of outclinic COPD patients: Results of an exercise counseling program. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 75, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, P.; McPherson, K.M.; Kayes, N.M.; Theadom, A.; McCambridge, A. Bridging the goal intention-action gap in rehabilitation: A study of if-then implementation intentions in neurorehabilitation. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y. Effects of a rehabilitation nursing program on muscle strength, flexibility, self-efficacy and health related quality of life in disabilities. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2006, 36, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.R.; Ng, G.Y.; Jones, A.Y.; Huang, M.Z.; Pang, M.Y. Whole-Body Vibration Intensities in Chronic Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1227–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, C.; Prapavessis, H.; Doherty, T. The Effect of a Prehabilitation Exercise Program on Quadriceps Strength for Patients Undergoing Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. PM&R 2012, 4, 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Moy, M.L.; Reilly, J.J.; Ries, A.L.; Mosenifar, Z.; Kaplan, R.M.; Lew, R.; Garshick, E. Multivariate models of determinants of health-related quality of life in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2009, 46, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.; Dobrosielski, D.A.; Stewart, K.J. Predictors of exercise intervention dropout in sedentary individuals with type 2 diabetes. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2012, 32, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordgren, B.; Fridén, C.; Demmelmaier, I.; Bergström, G.; Lundberg, I.E.; Dufour, A.B.; Opava, C.H.; the PARA Study Group. An outsourced health-enhancing physical activity programme for people with rheumatoid arthritis: Exploration of adherence and response. Rheumatology 2015, 54, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, R.K.; DeMarco, T.; Haskell, W.L. Perceptions of physical fitness in patients with heart failure. Prog. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 1999, 14, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pilleri, M.; Weis, L.; Zabeo, L.; Koutsikos, K.; Biundo, R.; Facchini, S.; Rossi, S.; Masiero, S.; Antonini, A. Overground robot assisted gait trainer for the treatment of drug-resistant freezing of gait in Parkinson disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 2015, 355, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, A.L.; Kaplan, R.M.; Myers, R.; Prewitt, L.M. Maintenance after pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic lung disease: A randomized trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003, 167, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, J.; Espe, L.; Kelly, A.; Veilbig, L.; Kwasny, M. Feasibility and outcomes of a community-based, pedometer-monitored walking program in chronic stroke: A pilot study. Top. Stroke Rehabil. 2014, 21, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Yang, B.; Fan, F.; Li, P.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y. Effects of individualized exercise program on physical function, psychological dimensions, and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled trial in China. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S.P.; McDonell, M.B.; Spertus, J.A.; Steele, B.G.; Fihn, S.D. A new self-administered questionnaire to monitor health-related quality of life in patients with COPD. Chest 1997, 112, 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Schmid, C.H.; Fielding, R.A.; Harvey, W.F.; Reid, K.F.; Price, L.L.; Driban, J.B.; Kalish, R.; Rones, R.; McAlindon, T. Effect of tai chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: Comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2018, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, G.Y.; McCarthy, E.P.; Wayne, P.M.; Stevenson, L.W.; Wood, M.J.; Davis, R.B.; Phillip, R.S. Tai chi exercise in patients with chronic heart failure: A randomized clinical trial. Arch. Intern. Med. 2011, 171, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, G.Y.; Mu, L.; Davis, R.B.; Wayne, P.M. Correlates of exercise self-efficacy in a randomized trial of mind-body exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabil. Prev. 2016, 36, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanaboni, P.; Hoaas, H.; Aarøen Lien, L.; Hjalmarsen, A.; Wootton, R. Long-term exercise maintenance in COPD via telerehabilitation: A two-year pilot study. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, I.Y.; An, S.Y.; Cha, W.C.; Rha, M.Y.; Kim, S.T.; Chang, D.K. Efficacy of Mobile Health Care Application and Wearable Device in Improvement of Physical Performance in Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 2018, 17, e353–e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, C.M.; Campos, L.A.; Pereira, F.O.; Cardoso, R.M.; Nascimento, L.M.; Oliveira, J.B.L. Objectively measured daily-life physical activity of moderate-to-severe Brazilian asthmatic women in comparison to healthy controls: A cross-sectional study. J. Asthma. 2018, 55, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, R.; Bastos, T.; Probst, M.; Seabra, A.; Vilhena, E.; Corredeira, R. Autonomous motivation and quality of life as predictors of physical activity in patients with schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2018, 22, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Suarez, I.; Liew, S.; Dembo, L.G.; Larbalestier, R.; Maiorana, A. Physical Activity Is Higher in Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Device Compared with Chronic Heart Failure. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2020, 52, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.S.d.C.; Nishimoto, D.Y.; Souza, G.D.E.; Ramirez, A.P.; Carletti, C.O.; Daibem, C.G.L. Effect of continuous progressive resistance training during hemodialysis on body composition, physical function and quality of life in end-stage renal disease patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damush, T.M.; Perkins, A.; Miller, K. The implementation of an oncologist referred, exercise self-management program for older breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncol. 2006, 15, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, M.J.; Bedard, A. Mission Impossible? Physical Activity Programming for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2016, 87, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligibel, J.A.; Meyerhardt, J.; Pierce, J.P.; Najita, J.; Shockro, L.; Campbell, N.; Newman, V.A.; Barbier, L.; Hacker, E.; Wood, M.; et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 132, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Elavsky, S.; Jerome, G.J.; Konopack, J.F.; Marquez, D.X. Physical activity-related well-being in older adults: Social cognitive influences. Psychol. Aging 2005, 20, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, L.; Reisman, D.; Binder-Macleod, S. Distance-Induced Changes in Walking Speed after Stroke: Relationship to Community Walking Activity. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2019, 43, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskell, W.L.; Lee, I.M.; Pate, R.R.; Powell, K.E.; Blair, S.N.; Franklin, B.A.; Macera, C.A.; Heath, G.W.; Thompson, P.D.; Bauman, A. Physical activity and public health: Updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation 2007, 116, 1081–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, M.; Pandey, D.K.; Arnsdorf, M.F.; Lauderdale, D.S.; Thisted, R.A.; Wicklund, R.H.; Al-Hani, A.J.; Black, H.R. Exercise capacity and the risk of death in women: The St. James Women Take Heart Project. Circulation 2003, 108, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, J.A.; Lakka, T.A.; Rauramaa, R.; Kuhanen, R.; Venäläinen, J.M.; Salonen, R.; Salonen, J.T. Cardiovascular fitness as a predictor of mortality in men. Arch. Intern. Med. 2001, 161, 825–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, K.Y.Z.; Zmuda, J.M.; Cauley, J.A. Patterns and determinants of muscle strength change with aging in older men. Aging Male 2005, 8, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, K.A.; Hunter, G.R.; Wetzstein, C.J.; Bamman, M.M.; Weinsier, R.L. The interrelationship among muscle mass, strength, and the ability to perform physical tasks of daily living in younger and older women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med Sci. 2001, 56, B443–B448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüssel, M.M.; dos Anjos, L.A.; de Vasconcellos, M.c.T.L.; Kac, G. Reference values of handgrip dynamometry of healthy adults: A population-based study. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianna, L.C.; Oliveira, R.B.; Araújo, C.G.S. Age-related decline in handgrip strength differs according to gender. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2007, 21, 1310–1314. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, A. Self-efficacy and health. Behav. Res. Ther. 1985, 23, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strecher, V.J.; McEvoy DeVellis, B.; Becker, M.H.; Rosenstock, I.M. The Role of Self-Efficacy in Achieving Health Behavior Change. Health Educ. Behav. 1986, 13, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, B.A.; Marcus, B.H.; Pate, R.R.; Dunn, A.L. Psychosocial mediators of physical activity behavior among adults and children. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 23 (Suppl. 1), 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.H.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999; Volume 13, pp. 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley, E.; Morris, K.S. State of the Art Review: Advances in Physical Activity and Mental Health: Quality of Life. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2007, 1, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Doerksen, S.E.; Morris, K.S.; Motl, R.W.; Hu, L.; Wójcicki, T.R.; White, S.M.; Rosengren, K.R. Pathways from physical activity to quality of life in older women. Ann. Behav. Med. 2008, 36, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyung, L.H.; Hee, S.E. The Influence Factors on Health-Related Quality of Life of Middle-Aged Working Women. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan-Olsen, S.L.; Pasco, J.A.; Hosking, S.M.; Dobbins, A.G.; Williams, L.J. Poor quality of life in Australian men: Cross-sectional associations with obesity, mobility, lifestyle and psychiatric symptoms. Maturitas 2017, 103, 32–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, R.; Powell, C.; Wilkes, E. Health Promotion in Nursing Practice. Nurs. Stand. 1991, 5, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachman, M.E.; Weaver, S.L. The Sense of Control as a Moderator of Social Class Differences in Health and Well-Being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijkstra, P.J.; Van Altena, R.; Otten, V.; Ten Vergert, E.M.; Postma, D.S.; Kraan, J.; Koeter, G.H. Reliability and validity of the chronic respiratory questionnaire (CRQ). Thorax 1994, 49, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.; Kosinski, M.; Keller, S.D. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med. Care 1996, 34, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, T.H.; Chavin, S.I. Preventive medicine and screening in older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1997, 45, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).