Abstract

Outdoor play has been associated with children’s and adolescents’ healthy development and physical activity. Attributes of the neighbourhood built environment can influence play behaviours. This systematic review examined the relationship between attributes of the neighbourhood built environment and the time children and adolescents (0–18 years) spend in self-directed outdoor play. We identified and evaluated 18 relevant papers using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool and developed a narrative synthesis of study results. We found moderate evidence that lower traffic volumes (ages 6–11), yard access (ages 3–10), and increased neighbourhood greenness (ages 2–15) were positively associated with time spent in outdoor play, as well as limited evidence that specific traffic-calming street features such as fewer intersections, low traffic speeds, neighbourhood disorder, and low residential density were positively associated with time spent in outdoor play. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review on this topic. The limited number of “good quality” studies identified highlights the need for additional research on the topic.

1. Introduction

Play is a central activity in children’s lives around the world [1]. Adults reflecting on favourite play memories often recall outdoor play, particularly in natural settings, remembering opportunities for freedom, fun, creativity, and skill- and confidence-building [2,3,4]. Recent research has identified a myriad benefits for children’s development, health and well-being. One of the most robust findings links time spent in outdoor play to physical activity, indicating that children playing outside are more physically active and less sedentary than when indoors [5,6]. A study of 10–13-year-old children and adolescents found that outdoor play contributed 36 min/day to physical activity, versus 40 min/day for organized sports, 17 min/day for active travel and 26 min/day for curriculum based physical activity [7]. Outdoor play has further been associated with motor, visual, and cognitive development, socio-emotional learning and mental health [8,9,10,11]. The benefits of outdoor play have also been recognized by pediatricians and public health professionals, who have stressed the importance of daily opportunities for outdoor play [12,13].

A pertinent model to consider is Sallis et al.’s ecological model for active living [14]. This model proposes that physical activity behaviours are intimately influenced by characteristics of the environment including neighbourhood design (e.g., traffic, pedestrian facilities, aesthetics), as well as how these aspects of the environment are perceived. This model helps to explain why environmental factors and parenting trends have been identified as inhibitors to children’s outdoor play, especially increased amounts of traffic, anxiety about child abduction, and increased time dedicated to academic work and structured activities [15,16,17]. The increasing amount of motorized vehicles in residential areas is frequently identified as a barrier to outdoor play [18,19,20] as high traffic speeds and volumes make both children and parents apprehensive about children being out alone [20,21,22,23]. Several international studies have also identified parents’ and children’s anxiety about children’s safety in public spaces. Parents fear their children will be abducted or hurt by abusive adults, or that their adolescents will be influenced by unruly peers [15,20,23,24,25]. In the case of neighbourhood violence, a review by Burdette and Whitaker [26] highlights that parents’ perceived danger has a greater impact on children’s outdoor play than actual crime statistics. An intervention in a US inner-city neighbourhood indicated that increasing children’s access to a play space with attendants contributed to a sense of safety, thereby resulting in more children using the space and engaging in physically active play [27]. Finally, children’s leisure time is increasingly structured, with a Dutch study coining the term “backseat generation” for children who spend much of their leisure time being driven to extracurricular activities [18]. The parenting practices, use of leisure time, and traffic characteristics mentioned above are all influenced by the neighbourhood environment in that street design and amenities help determine whether the neighbourhood is conducive to free play, feels safe, and, in turn, whether children utilize the neighbourhood for outdoor play [28,29,30].

Children play in diverse areas, depending on their age, gender, socioeconomic status and the characteristics of their neighbourhood [24]. We reviewed the literature that examines the relationship between play and the outdoor neighbourhood environment: the streets, yards and public spaces close to children’s homes. The neighbourhood built environment is the setting for a large proportion of children’s and adolescents’ outdoor play [31] and is theoretically available to individuals of all ages, abilities and socioeconomic backgrounds. Improving access to safe play spaces may provide important opportunities for reducing disparities in child health and development, particularly in urban environments [32]. A growing body of research is uncovering the influence of the built environment on health. Frank and colleagues [33] describe a conceptual framework linking transportation infrastructure, land use and walkability, the pedestrian environment and greenspace on health outcomes, including physical activity and social interaction. This framework does not incorporate child-specific considerations, yet increasing research with children highlights specific influences on child development [34]. Neighbourhood characteristics, both subjectively perceived by families and objectively measured by researchers, have been shown to impact children’s and adolescents’ access to outdoor play [35,36,37]. Previous systematic reviews have examined the relationship between the neighbourhood environment and physical activity occurring outdoors among youth [38,39]; however, a synthesis looking at exclusively outdoor play is lacking. The objective of this systematic review is to examine the relationship between physical characteristics of the neighbourhood built environment and the time children and adolescents spend in outdoor play.

2. Methods

This review is registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO network (registration No. CRD42016046456).

2.1. Study Inclusion Criteria

We examined outdoor play from birth to 18 years of age. We reviewed all articles published up to 28 January 2019 (last search date). We included all study designs in the review, but only quantitative articles met our inclusion criteria. We included all articles translatable to English by Google Translate.

In this review, the independent variable is the “neighbourhood built environment attribute”, defined as a characteristic of the physical outdoor space near the residence of child or adolescent study participants, including yards, streets and public open space. We included front and back yards in the neighbourhood play environment because of their role as an intermediary between the street, the alley, and the home. Due to our interest in understanding the influence of neighbourhood planning and design, we focused on environmental characteristics, such as yard size and intersection density, as opposed to equipment such as slides and swings. We included pedestrian infrastructure such as benches, water fountains, and garbage cans because of their impact on street width. We included school grounds if they were examined outside of school hours, independently of programs such as after-school care. Because parent and child perceptions of the environment are important predictors of play-related behaviours such as child independent mobility and physical activity, we included both subjectively-perceived and objectively-measured attributes of the built environment.

Play is defined as “freely chosen, personally directed, intrinsically motivated behaviour that actively engages the child” [40]. We only included studies that examined “outdoor” play because of the numerous health and developmental benefits associated with outdoor play [16], as well as to investigate the relationship between play and the built environment. To ensure the inclusion of papers studying outdoor play behaviours in adolescents, we included the terms “hanging out”, “unstructured time” and “leisure” in our searches, the most frequent terms encountered in our survey of the literature. We decided that use of the term “play” was a sufficient descriptor of play behaviours in participants, even if the term is rarely defined in publications. Moreover, we did not include independent mobility as a type of play. Though studies have demonstrated a positive link between independent mobility and neighbourhood outdoor play [41,42], independent mobility behaviours can also include travel behaviours unrelated to play. Finally, we decided that the primary outcome of selected studies should be “time” spent in outdoor play. This criterion allowed us to identify environmental features with a measurable impact on play behaviour.

In summary, we included studies in the review if (a) they included children and adolescents aged 0–18, if (b) they reported a subjective or objective outdoor neighbourhood built environment characteristic as an independent variable, and if (c) this variable was linked to time spent in self-directed outdoor play.

2.2. Study Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they studied the link between outdoor play and non-neighbourhood environments, such as indoor environments. Outcome behaviours were not considered outdoor play if the activities described were explicitly directed by adults, including organized sports, time spent in school, childcare, or an after-school program. Studies which examined the link between the neighbourhood built environment and outdoor play without including a measure of time or duration were also excluded.

2.3. Search Strategy

The neighbourhood play search strategy is described in Appendix A. Because of the interdisciplinary scope of the topic, we searched six electronic databases during the review process: the Avery Index, MEDLINE (Ovid), PsycInfo (EBSCO), SPORTDiscus (EBSCO), ERIC (EBSCO), CINAHL (EBSCO). Additionally, we manually searched the Journal of Children, Youth and Environments because it is a journal that has traditionally published research relevant to this topic. All databases were searched on 28 January 2019. Finally, a manual search of the reference list of identified studies was conducted to search for potential additional studies, as suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [43]. All studies identified in the manual search were found to be duplicates of studies identified by the database search.

Search terms included Boolean combinations of the following words: play, leisure, hanging out, unstructured time, built environment, physical environment, neighbourhood, street, yard, child, youth, adolescent, teen, time and duration (Appendix A). Two independent reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of all articles identified by the search strategy and read all selected full text articles. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion and consensus, including a third reviewer when necessary. Consensus was reached on all decisions of study eligibility.

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data extraction was completed by one researcher (AL) and checked by another (JV). The strength of association between dependent and independent variables was extracted for each selected study, and methodological quality of studies was assessed by one researcher (JV). Another researcher (MB) reviewed all extracted effect magnitudes and checked a subset of the methodological quality assessment. When data appeared to be incomplete or incorrect, corresponding authors were contacted by email for additional information. Data extraction identified all study methods and results related to the inclusion criteria, and transcribed these in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4, using each study’s exact wording. We selected the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies because it allowed for a reliable and efficient analysis of quantitative-descriptive research. The tool evaluated the following criteria: participant recruitment (if the study reports how representative the sample is of the population), outcome measurements (whether outcome measures have been standardized or validated), participant controls (if demographic characteristics are reported and if the most important factors are controlled for in analyses), and response rates (>80% complete data and >60% response rate). For each criterion, the study received one star if it was reported by the study and met (yes), and zero stars if it was not reported by the study (can’t tell) or was reported, but not met (no). Studies were graded according to the number of criteria met (* = 1 criterion met, with a maximum of **** = 4 criteria met). Details on MMAT methodology are described elsewhere [44].

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

Table 3.

Associations of built-environment measures with time spent in outdoor play.

Table 4.

Best evidence synthesis.

2.5. Analysis

Meta-analysis was planned for sufficiently homogeneous data with respect to statistical and methodological characteristics. Otherwise, narrative syntheses of research outcomes were conducted to highlight patterns in study methodologies and results. We chose to summarize study results as per Tompa, Trevithick and McLeod’s [58] best evidence synthesis guidelines, as per Appendix B. This method takes into account the number, the quality and the consistency of studies to evaluate the strength of the evidence on a topic [58]. According to the methodology, all medium and high quality studies are included in the narrative analysis, in order to highlight the most reliable results. Low quality studies were not included in the analysis. The results of the synthesis provide a general sense of which neighbourhood features are the most influential: often studies had different results for different age groups and genders. We used MMAT assessments for the quality component of the synthesis (one and two MMAT stars = “low quality study”, 3 stars = “medium quality study”, 4 stars = “high quality study”).

3. Results

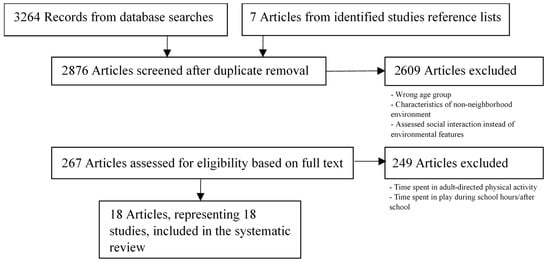

From an initial result of 2876 papers, we identified 18 articles that fit our criteria, from 18 different studies, published between 2004 and 2016 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study search strategy.

3.1. Study Participants

As shown in Table 1, studies were conducted in the United States (6), the Netherlands (5), Australia (2), Canada (1), Germany (1), Switzerland (1), England (1) and Mexico (1), with a cumulative sample of 29,426 participants (accounting for participants included in Remmers et al.’s [53,54] cross-sectional and longitudinal research). Fourteen studies examined children (1–12 years) representing approximately 27,219 participants. Four studies examined both children and adolescents (0–17 years), with approximately 2,207 participants. Studies recruited participants through primary schools (7) [35,41,45,51,52,56,57], hospitals (3) [37,53,54], daycare centres or reschools (2) [47,55], school health providers (2) [36,55], advertisements and posters (2) [49,54], commercial address providers (2) [28,50] or a government program (1) [48]. Two studies used a combination of these methods [54,55]. One study did not refer to any participant recruitment strategy [46].

3.2. Study Characteristics

A variety of instruments were used to measure time spent in outdoor play (see Table 2), with parent questionnaires being the most prevalent (15) [45,47,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57]. Other methods included parent diaries (1) [46] and child/adolescent questionnaires (2) [41,48]. The “Outdoor Playtime Checklist” [26] was employed by two studies [47,55], and ten studies used other validated methodologies [35,37,48,49,50,52,54,56,57]. Six studies used methodologies that have not yet been validated to evaluate outdoor play [28,36,41,45,46,53]. The neighbourhood built environment was evaluated by parent questionnaire (10) [28,35,36,49,50,52,53,54,56,57], research-team audits (6) [35,37,45,46,51,55], satellite image analysis (2) [36,47], database analysis (1) [37], child questionnaire (2) [41,48], census data (1) [37], with some studies using two of these methods [35,36,37]. Fifteen studies used validated methodologies to evaluate neighbourhood attributes [35,36,37,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Research designs were cross-sectional (14) [35,36,37,41,45,46,47,49,50,51,52,55,56,57], longitudinal (2) [48,53] or a combination of longitudinal and cross-sectional methods (2) [28,54].

3.3. Study Results

The selected articles identified several associations between the neighbourhood built environment and time spent in outdoor play, with significant results summarized in Table 3. Heterogeneity in measurement of time spent in outdoor play did not allow for meta-analysis. The results of the best evidence synthesis are summarized in Table 4. In order to synthesize findings, we grouped similar study results into eight themes and 17 attributes (subthemes) of the built environment. The themes and subthemes were developed inductively through consideration of the characteristics of the described features and labeled accordingly. For example, in subtheme “traffic volume”, we included Bringolf-Isler’s measure of parents’ perception of a “problem to play outdoors because of traffic” [36], Page’s measure of parents’ perception of “traffic safety”(a compound measure including the variable “heavy traffic”) [41], Aarts’ audits of the “presence of home zones” [45], and Lee’s measure of street segments with “low traffic volumes” [51]. This organization of results required certain theoretical assumptions, such as “home zones” being areas where traffic volumes would be low. Authors were contacted when terms were unclear. In Table 4, studies with an MMAT methodological rating below ***(“medium quality”) are in grey font. Their results are not included in the best evidence synthesis [see Appendix B for summary of guidelines].

3.3.1. Public Open Space Characteristics (9 Studies)

This theme summarizes the impact of open space that is distinct from the home (as opposed to the yard). The review found moderate evidence that public open spaces had no effect on play: five medium/high-quality studies found no relationship between public open space attributes and time spent in outdoor play. However, other studies did find associations: in one medium-quality study, a higher proportion of parks, woods, and agriculture per 2.5 hectares around the home predicted more time spent in outdoor play for children aged 6 to 10 [36]. Inversely, one high-quality study associated a higher number of formal outdoor play spaces (play grounds, school yards, paved play grounds, and half pipe or skating track) with less time spent in play in the 7–12 age range [45]. The authors suggest that this result may be linked to the “street play” culture of the Netherlands, as well as to the quality of surrounding play spaces: play spaces perceived as unsafe may impede outdoor play.

3.3.2. Street Characteristics (8 Studies)

This theme summarizes attributes related to street proportions and street infrastructure. The review found limited evidence that street characteristics have an influence on outdoor play: traffic calming features and pedestrian amenities appear to have a positive impact, while walkability and intersections seem to have a negative impact. Sidewalks, traffic lights, speed bumps, home zones (woonerven in the Netherlands: street configurations which often have speed limits of 15km/hr), roundabouts and “safe places to cross” were associated with more time spent in outdoor play in two high- and medium-quality studies [41,45]. Aarts et al. [45] found that pedestrian crossings had mixed results, while street lighting and safety islands were associated with less outdoor play. The presence of parallel parking spaces and parking lots had a positive association with outdoor play for older boys in Aarts et al. [45], who suggest that parallel parking spots can provide buffers between the street and the sidewalk/yard play area, while Lee et al. [51] found a negative association for both genders 6–11 for parking spaces, as part of a compound measure of “path obstructions”. In Lee et al. [51], pedestrian amenities such as benches and water fountains were associated with more outdoor play. Greater intersection density was associated with less time spent in outdoor play for children in one medium-quality study [51], and another high-quality study identified that the “presence of intersections” had the same association [45]. In one high-quality study, living in a “walkable neighbourhood” was linked to more outdoor play in a park, but to less outdoor play in a cul-de-sac or driveway [50]. Lee et al. [51] also found that walkability, defined as a combination of land use, street connectivity and residential density, was associated with less outdoor play.

3.3.3. Traffic Characteristics (7 Studies)

The review found moderate evidence that low traffic volumes have a positive impact on outdoor play. Three high- and medium-quality studies reported that low traffic volumes were associated with more time spent in outdoor play [41,45,51], and one study found that traffic was a barrier to outdoor play [36]. Other subgroups were not affected: Bringolf-Isler et al. [36] found that traffic volume had no effect on the outdoor play of 13–14 year olds, Page et al. [41] had the same result for boys 10–11, as did Aarts et al. [45] for girls 4–6 and 7–12 year olds of both genders. Aarts et al. [45] found that home zones were linked to increased outdoor play, while the presence of 30 km/hr zones were associated with less outdoor play, and found no effect on girls aged 4–12.

3.3.4. Housing Characteristics (7 Studies)

This theme summarizes the effects of living in a specific type of housing, living while surrounded by a certain type of housing, or living in a certain population density, a characteristic closely related to building type. The review found limited evidence linking housing and outdoor play: both higher density and detached homes were associated with less play, while duplexes had the opposite effect. Kimbro et al. [37] found that living in public housing was linked to more outdoor play in five year olds. Aarts et al. [35] found that girls 4–6 living in a detached residence spent less time in outdoor play, while boys 4–6 living in a rental property or a duplex spent more time in outdoor play. Kimbro et al. [37] and Aarts et al. [35] (girls 4–6, boys 10–12) found that living in an apartment was linked to less outdoor play. Greater neighbourhood population density was also linked to less time spent in outdoor play in two medium-quality studies for 6–11 year olds [36,51], though Lee et al. [51] examined residential density within a measure of neighbourhood walkability scores, wherein greater density is linked to greater walkability. Bringolf-Isler et al. [36] found that neither population or housing density had an effect on the outdoor play of 13–14 year olds.

3.3.5. Yard Characteristics (6 Studies)

This theme includes all private outdoor space surrounding the home. The review found moderate evidence that yard access was positively associated with more outdoor play. One high-quality and two medium-quality studies reported that access to a yard was associated with more time spent in outdoor play [52], or that the absence of yards was linked to less time spent in outdoor play [35,36]. Aarts et al. [35] reported that the absence of a yard predicted more outdoor play in girls 4 to 6, while two studies found no relationship between yard access and outdoor play [35,36], Bringolf-Isler et al. [36] finding no effect on 13–14 year olds. One medium quality study found that yard size had no effect [49].

3.3.6. Neighbourhood Greenness (4 Studies)

This theme includes measures that refer to general neighbourhood “greenness”, as opposed to a specific place such as a park. Studies identified greenness through satellite imagery [47], features such as street trees, flower beds and recreational areas [48] or governmental designation as a neighbourhood type with extensive greenery [35]. The review found moderate evidence that neighbourhood greenness was a predictor of more time spent in outdoor play, as identified in three high- and medium-quality studies [35,48,53]. One longitudinal study found that a perceived increase of “nature” in the neighbourhood was linked to less time spent in walking (for leisure) for boys 12–15 [48].

3.3.7. Physical Disorder (4 Studies)

This theme includes measures of house maintenance, litter, graffiti, vandalism and dog feces. The review found mixed evidence of its effect on outdoor play. One medium-quality study linked greater physical disorder around the home with more outdoor play in five year-olds [37], while one high-quality study found that better house maintenance was associated with boys 10–12 spending less time in outdoor play [45]. Both studies suggest that increased physical disorder in a neighbourhood can support play. Two medium-quality studies found no association between disorder and time spent in outdoor play [54].

Other built environment attributes significantly associated with outdoor play in the 18 selected studies include the presence of water, access to a diversity of travel routes and living in a city centre [35]. Because these results were not mentioned in more than one selected study, they are not included here (see Table 3).

3.4. Summary of Results

The 18 studies that met our inclusion criteria examined a broad range of neighbourhood built environment features. In most studies, play behaviours were subjectively reported by parents, thus results depended on their individual interpretation of the term “play” (see Table 2). We did not identify any publications with objective measures of neighbourhood play. According to the MMAT methodological appraisal, six studies met the criteria for low methodological quality, eight studies met medium quality criteria and four studies met high quality criteria (see Table 3).

Overall, the review revealed that modifiable environmental neighbourhood features are associated with the time children and adolescents spend in outdoor play. According to the best evidence synthesis guidelines [58], no strong evidence was found in this review. However, we found moderate evidence that children and adolescents spent more time in outdoor play if they lived in neighbourhoods with low traffic volumes (ages 6–11), access to a yard (ages 3–10) and increased neighbourhood greenness (ages 2–15). Surprisingly, we found moderate evidence that access to public open space was not associated with time spent in outdoor play (ages 0–16). In this review, most studies described public open space as parks or playgrounds. Limited evidence linked time spent in outdoor play and: street features (ages 4–12), fewer intersections (ages 4–12), low walkability (ages 4–18), low traffic speeds (ages 5–12), living in rental housing (ages 4–6), living in public housing (age 5), living in a duplex (boys 4–6), low building/population density (ages 5–11) and physical disorder (ages 5–12).

Several studies identified gender-specific results: concerns about traffic safety seem more likely to constrain girls’ play, and pedestrian infrastructure was more often linked to increased play in girls. Inversely, certain traffic-related features, such as parking, were linked to more time spent in outdoor play for boys, aged 7 and up. This may be related to boys’ use of paved surfaces for team games or skateboarding. In this review, adolescents’ outdoor play was less likely to be associated with built environment features. Intersections, traffic volume and building/population density had no effect on participants aged 12 and up. We also identified regional trends: neighbourhood greenness, public open space, and housing density were more likely to be studied in Europe, whereas walkability was studied exclusively in North America.

4. Discussion

4.1. Play and Urban Design

At first glance, the features of a “playable” neighbourhood identified in this review describe a rural or suburban neighbourhood, with private yards, extensive greenery and limited traffic. Suburban typologies, developed in the post-WWII era, emphasize the “nuclear family” and private spaces for children’s play [74]. Recently, extensive research on low-density neighbourhoods has shown their negative impacts on adult health by reducing active travel behaviours [75] and requiring a high consumption of fossil fuels [76], highlighting that though suburban characteristics may support child and adolescent outdoor play, they are also associated with disadvantages for other age groups.

Most current trends in urban design (such as “smart growth” and new urbanism) promote dense typologies which emphasize active travel and public transit [76]. However, this review highlights evidence that density and certain accompanying features can have a negative impact on children’s outdoor play. One approach to this dilemma may be to identify denser neighbourhood typologies which include many, if not all the playable features synthesized in this review. For example, compact urban neighbourhoods with traffic calming features, such as cul-de-sacs that remain permeable to cyclists and pedestrians, 15 km/hr speed limits, and features, such as benches and trees, that encourage chance encounters and conversation. However, more research on small-scale street features is required to determine their impact. For example, garbage cans could be perceived as either a pedestrian amenity or a path obstruction, as in Lee et al. [51]. Ready access to parks may be less important to outdoor play: this review identified that proximate green spaces such as yards and general neighbourhood greenness have a greater impact on outdoor play than public open space. This review found that apartments and detached homes were negatively associated, while duplexes were positively associated with time spent in outdoor play: providing shared outdoor space, or other “doorstep” play spaces may be one strategy for capitalizing on the positive effects and mitigating the negative effects of housing density on children’s outdoor play.

4.2. Outdoor Play and Physical Activity

Several existing systematic reviews examine the relationship between the built environment and children’s physical activity. A 2006 review found that children’s physical activity was positively related to the proximity of recreational facilities and schools, as well as to the presence of sidewalks, controlled intersections, accessible destinations, and public transportation [77]. Physical activity was negatively associated with a high number of roads, high traffic density, high traffic speeds, area deprivation, and perceptions of local crime. The present review found similar results, though two studies in this review found that physical disorder had a positive association with play, especially for boys [37,45]. A 2015 review [39] found surprising results concerning objectively-measured built environment attributes and children and youth’s physical activity. Elements that attempt to promote play (play facilities, playgrounds, parks, beaches, sports venues, recreational facilities, gyms) were linked to less physical activity in young girls, and pedestrian infrastructure (sidewalks, walking tracks, path lighting, traffic lights, high connectivity streets, local destinations) was linked to less physical activity in children of both genders. Inversely, the combined effect of play infrastructure and walking infrastructure was positively correlated to adolescent girls’ and boys’ physical activity. We found similar results. Five high- and medium-quality studies in the present review examined links between access to public open space and time spent in outdoor play, with mixed results: four studies found no significant association between the two, and one study found that access to a formal outdoor play facility was negatively associated with outdoor play. We also found that pedestrian infrastructure was positively linked to girls’ outdoor play (ages 4–12).

4.3. Subjective and Objective Results

Four subcategories in the best evidence synthesis show trends related to their method of assessment of the built environment measurement. Four of the five medium/high quality studies that found no link between public open space and outdoor play measured access to public open space subjectively, i.e., by asking parents or children if parks are located near their home. This suggests that parents’ and children’s perceptions of public open space access do not influence outdoor play. More studies that objectively measure access to public open space would be an important counterpart to these findings. All three medium/high quality studies that found a link between yard access and outdoor play also used subjective methods. Different housing typologies likely have different yard types (e.g., townhouse courtyards), and parent and child perception of these yards could be important for outdoor play. Inversely, all medium/high quality studies measuring the impact of intersections and neighbourhood greenness used objective measures. This suggests that increasing neighbourhood greenness could lead directly to increased outdoor play, which may be useful for municipal planning strategies.

4.4. Limitations

This study is limited by its focus on the built environment: 11 studies out of 18 examined both social and environmental characteristics and found that social factors had a greater or equal effect on outdoor play [35,36,37,41,45,47,50,53,56]. These results emphasize the importance of employing an ecological framework that examines social environments, individual and family characteristics, built environments, and their interdependence when examining the modifiers of play [78]. For example, the results associated with housing type in this review may be associated with household socioeconomic status, which may independently influence outdoor play [79]. Furthermore, built environment interventions may have different effects in different social environments [14]. Increasing accessible green space may not be effective in a neighbourhood where residents do not feel safe allowing children to play outside. Likewise, the interdependence of environmental characteristics must also be considered. For example, increasing greenery without reducing traffic volumes in a neighbourhood may have little effect on outdoor play. Second, a large diversity of methods and measures may have contributed to our mixed results: each study measured neighbourhood environments differently, and many examined a variety of outdoor play behaviours. It is also likely that different countries and communities identify built environment features in disparate ways: a Dutch woonerf, a traffic-calmed residential street, is both similar to and radically different from a Canadian cul-de-sac. The third limitation of this study lies in its analysis of compound built environment measures which combine many variables, such as “attractiveness”, “walkability”, “poor quality of action-space”, “traffic safety”, “accessibility” and “pedestrian amenities”. Because these compound measures did not report the impact of individual variables, it can be misleading to analyze their association with outdoor play. For example, in Page et al.’s [41] measure of traffic safety, it is possible that only “heavy traffic” is significant, and that “perception of safe places to cross, roads, pollution” have no impact on outdoor play. The fourth limitation of this study is the low number of adolescent participants included. Despite our inclusion of adolescent-specific play terms, we found only four articles examining the built environment and adolescent play behaviours. Fifth, this review is limited by the small number of high quality studies identified. No strong evidence was identified in the evidence synthesis. Sixth, the unstructured outdoor play of adolescents (aged 13–18 years) may differ conceptually from younger children (0–12 years). Only one study that included adolescents divided the results in applicable age groups [48], thus we were unable to meaningfully examine potential differences. Finally, we acknowledge that most of the studies in this review were conducted in high income countries, and as such the results may not reflect realities in other economic or sociocultural contexts.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this systematic review suggest that the environments where children and adolescents live have some associations with the time they spend in self-directed outdoor play. In this review, we found moderate evidence that low traffic volumes (ages 6–11), yard access (ages 3–10), and increased neighbourhood greenness (ages 2–15) are associated with the time children spend in outdoor play. Interestingly, we found moderate evidence that public open spaces, such as parks and formal outdoor play facilities, have no association with outdoor play time. Evidence was limited about the impact of other features on outdoor play, but features such as fewer intersections, low residential density, low traffic speeds, living in rental housing, living in public housing and higher physical disorder appeared to support outdoor play. Moreover, limited evidence suggests that street features such as sidewalks, traffic lights, speed bumps, home zones and roundabouts have a significant association with girls’ play. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to examine the impact of the built environment on children’s outdoor play. Through a narrative synthesis, the review identifies common trends in international research: diminished “doorstep” play space, loss of vegetation and increased traffic have important impacts on children’s outdoor play in communities around the world. Future systematic reviews should consider the qualitative aspect of the relationship between the environment and children’s outdoor play, paying special consideration to the influence of child age and gender, and what characteristics are important to the children themselves. Future research should examine different settings, including rural communities and communities with low socioeconomic status. Possible urban design interventions to improve play opportunities could include having numerous accessible play spaces near the home, increased greenery, and trees on residential streets and traffic calming measures. Moreover, interest in designing healthier communities is growing, with several cities proposing major interventions to improve citizen health [80,81]. Cities appear to have enormous potential for reducing health inequalities when they prioritize the provision of safe places to live, work and play for all citizens [80]. Indeed, marginalized and low-income children often have lesser access to safe play spaces, as well as higher rates of illness and injury [32,82]. The results of this review suggest that providing amenities such as neighbourhood vegetation, numerous proximate play spaces and low-traffic zones are important tools for policy makers and designers to support children’s outdoor play, an essential component of child development and health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. and A.L.; formal analysis, M.B., A.L., and J.V.; methodology, M.B., S.H., A.L., and J.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.L.; writing—review and editing, M.B. and J.V. and M.B.; supervision, M.B.

Funding

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Grant #MOP-142262. M.B. is supported by salary award from the British Columbia Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Search strategies:

What is the Relationship between the Neighborhood Built Environment and Time spent in Outdoor Play? A Systematic Review

Avery Index (ProQuest)

Search date: 18 September 2016

(su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR “unstructured time”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration) AND PD(2000–2016) AND STYPE(“scholarly journals”)

Results: 67 articles

Notes: Search 18 September 2016–18 January 2017, zero results.

Search date: 17 February 2018

(su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR “unstructured time” OR “leisure”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration) AND PD(2000–2018) AND STYPE(“scholarly journals”)

Results: 0 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019

(su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR “unstructured time” OR “leisure”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration) AND STYPE(“scholarly journals”)

Limiter: all articles published up to 28 January 2019.

Results: 1 additional article.

ERIC

Search date: 18 September 2016 (ProQuest)

(su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR “unstructured time”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration) AND PD(2000–2016) AND STYPE(“scholarly journals”)

Results: 67 articles

Notes: Search 18 Sept 2016–18 January 2017, zero results.

Search date: 17 February 2018 (EBSCOhost) (su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR leisure OR “unstructured time”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration)

Limiters–Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals; Published Date: 20000101–20171231

Results: 261 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019 (EBSCOhost) (su(Play) OR “hanging out” OR leisure OR “unstructured time”) AND (“built environment” OR “physical environment” OR neighborhood OR neighbourhood OR park OR playground OR street OR yard) AND (child* OR youth OR adolescent OR teen) AND (time OR duration)

Limiters–Scholarly (Peer Reviewed) Journals; Published Date: -20190128

Results: 15 additional articles

MEDLINE (Ovid)

Search date: 18 September 2016

1. “Play and Playthings”/7901

2. (play or playing) 564430

3. (“hanging out” or “unstructured time”) 66

4. Environment Design/4784

5. Environment/54913

6. Parks, Recreational/156

7. Residence Characteristics/27105

8. (“built environment” or “physical environment” or neighbo?rhood or park* or playground* or street* or yard*) 164713

9. Time factors/1084616

10. (time or duration) 3591082

11. (child* or teen or adolescent or youth) 3037400

12. 1 or 2 or 3: 564485

13. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8: 242330

14. 12 and 13: 9037

15. 9 or 10: 3591082

16. 14 and 15: 1720

17. 11 and 16: 446

18. limit 17 to yr=“2000-Current”: 388

Results: 388 articles

Notes: Search 18 Sept 2016–18 January 2017, 69 results.

Search date: 17 February 2018

1. “Play and Playthings”/8277

2. (play or playing).mp./631104

3. (“hanging out” or “unstructured time” or “leisure”).mp./17511

4. Environment Design/5596

5. Environment/59455

6. Parks, Recreational/569

7. Residence Characteristics/30091

8. (“built environment” or “physical environment” or neighbo?rhood or playground* or park* or street* or yard*).mp./187944

9. time factors/1126083

10. (time or duration).mp./3980654

11. (child* or teen or adolescent or youth).mp./3233296

12. 1 or 2 or 3/647710

13. 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8/271840

14. 12 and 13/11650

15. 9 or 10/3980654

16. 14 and 15/2631

17. 16 and 11/791

18. limit 17 to yr=“2000-Current”/717

* mp=title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms

Results: 278 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019 (Ovid)

Reran search without publication date limit, 67 additional results.

CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

Search date: 18 September 2016

1. Play or playing or “hanging out” or “unstructured time”

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. EM 200001-

6. S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 AND S5

7. MH “Play and Playthings+”

8. (MH “Home Environment”) OR (MH “Environment and Public Health+”)

9. (MH “Time Factors”)

10. S7 AND S8

11. S9 AND S10

12. S3 AND S11

13. S5 AND S12

14. S6 OR S13

Results: 178 articles

Notes: Search 18 September 2016–18 January 2017, 4 results

Search date: 17 February 2018

1. Play or playing or “hanging out” or “unstructured time” or leisure

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. EM 200001-

6. S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 AND S5

7. MH “Play and Playthings+”

8. (MH “Home Environment”) OR (MH “Environment and Public Health+”)

9. (MH “Time Factors”)

10. S7 AND S8

11. S9 AND S10

12. S3 AND S11

13. S5 AND S12

14. S6 OR S13

Results: 22 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019

Reran search without publication date limit, 23 additional results.

PsycInfo (EBSCOhost)

Search date: 18 September 2016

1. Play or playing or “hanging out” or “unstructured time”

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. DE “Childhood Play Behavior” OR DE “Pretend Play” OR DE “Childhood Play Development” OR DE “Childrens Recreational Games” OR DE “Doll Play” OR DE “Games” OR DE “Recreation” OR DE “Role Playing” OR DE “Toys”

6. S1 OR S5

7. DE “Community Facilities” OR DE “Built Environment” OR DE “Architecture” OR DE “Urban Planning”

8. DE “Environmental Planning” OR DE “Recreation Areas” OR DE “Playgrounds” OR DE “Active Living”

9. S2 OR S7 OR S8

10. S6 AND S9

11. S3 AND S10

12. S4 AND S11

13. Limiters–Published Date: 20000101-

Results: 546 articles

Notes: Search 18 September 2016–18 January 2017, 3 results

Search date: 17 February 2018

1. Play or playing or “hanging out” or “unstructured time” or leisure

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. DE “Childhood Play Behavior” OR DE “Pretend Play” OR DE “Childhood Play Development” OR DE “Childrens Recreational Games” OR DE “Doll Play” OR DE “Games” OR DE “Recreation” OR DE “Role Playing” OR DE “Toys”

6. S1 OR S5

7. DE “Community Facilities” OR DE “Built Environment” OR DE “Architecture” OR DE “Urban Planning”

8. DE “Environmental Planning” OR DE “Recreation Areas” OR DE “Playgrounds” OR DE “Active Living”

9. S2 OR S7 OR S8

10. S6 AND S9

11. S3 AND S10

12. S4 AND S11

13. Limiters–Published Date: 20000101-

Results: 194 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019

Reran search without publication date limit, 158 additional results.

SportDiscus (EBSCOhost)

Search date: 18 September 2016

1. Play or playing “hanging out” or “unstructured time”

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. S2 AND S3

6. S1 AND S5

7. S4 AND S6

8. Limiters–Published Date: 20000101-

Results: 129 articles

Notes: Search 18 September 2016–18 January 2017, 2 results

Search date: 17 February 2018

1. Play or playing “hanging out” or “unstructured time” or leisure

2. “built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or park or playground or street or yard

3. child* or youth or adolescent or teen

4. Time or duration

5. S2 AND S3

6. S1 AND S5

7. S4 AND S6

8. Limiters–Published Date: 20000101-

Results: 92 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019

Reran search without publication date limit, 36 additional results.

JSTOR

Search date: 18 September 2016

1. ((play or “hanging out” OR “unstructured time”) AND (“built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or street or yard) AND (child* or youth or adolescent or teen) AND (time or duration))

2. In journals “Children, Youth and Environments” and “Canadian Journal of Public Health”

3. Date: 1 January 2000–18 September 2016

Results: 298 articles

Notes: Search 18 September 2016–18 January 2017, zero results

Search date: 17 February 2018

1. ((play or “hanging out” OR “unstructured time” OR leisure) AND (“built environment” or “physical environment” or neighborhood or neighbourhood or street or yard) AND (child* or youth or adolescent or teen) AND (time or duration))

2. In journals “Children, Youth and Environments” and “Canadian Journal of Public Health”

3. Date: 1 January 2000–17 February 2018

Results: 201 additional articles

Search date: 28 January 2019

Reran search without publication date limit, 219 additional results.

Appendix B

Best evidence synthesis guidelines, from Tompa et al. [83].

Strong evidence

Minimum study quality: High

Minimum number of studies: 3

If there are only three high-quality studies, all of them must report consistent findings.

If there are four or more high-quality findings, all of them must report consistent results unless there is a specific methodological reason that could explain a divergent result.

The majority (>50%) of medium-quality studies must concur with the findings from the high-quality studies.

Moderate evidence

Minimum study quality: Medium or <3 high-quality studies

Minimum number of studies: 3; they can be a mixture of medium- and high-quality studies.

At least 3 studies must report consistent findings, and the majority (>2/3) of all the studies must report consistent findings.

Limited evidence

Minimum study quality: Medium

Minimum number of studies: 1

Fewer than three studies reporting consistent findings.

Majority (>50%) of the studies reporting consistent findings.

No evidence

No high- or medium-quality studies were available from which to draw conclusions.

Mixed evidence

The findings from medium- and high-quality studies were contradictory.

References

- Hyun, E. Culture and development in children’s play. In Making Sense of Developmentally and Culturally Appropriate Practice (DCAP) in Early Childhood Education; P. Lang: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, D.G.; Singer, J.L.; D’Agostino, H.; DeLong, R. Children’s pastimes and play in sixteen nations: Is free-play declining? Am. J. Play 2009, 1, 283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Brunelle, S.; Herrington, S.; Coghlan, R.; Brussoni, M. Play worth remembering: Are playgrounds too safe? Child. Youth Environ. 2016, 26, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrel Raymund, J.; Ferrei Raymund, J. From barnyards to backyards: An exploration through adult memories and children’s narratives in search of an ideal playscape. Child. Environ. 1995, 12, 362–380. [Google Scholar]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C.; Daniels, S.R. Parental report of outdoor playtime as a measure of physical activity in preschool-aged children. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004, 158, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, I.; Van Der Horst, K.; Kremers, S.; Van Lenthe, F.J.; Brug, J. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth—A review and update. Obes. Rev. 2006, 8, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghese, M.M.; Janssen, I. Duration and intensity of different types of physical activity among children aged 10–13 years. Can. J. Public Health 2019, 110, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, J.L.; Cornell, M.; Gill, T. A systematic review of research into the impact of loose parts play on children’s cognitive, social and emotional development. School Ment. Health 2017, 9, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, I.G.; Rose, K.A. Myopia: Is the nature-nurture debate finally over? Clin. Exp. Optom. 2019, 102, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kennair, L.E.O. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yogman, M.; Garner, A.; Hutchinson, J.; Hirsh-Pasek, K.; Golinkoff, R.M. The power of play: A pediatric role in enhancing development in young children. Pediatrics 2018, 142, e20182058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health. Active Outdoor Play Statement from the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health. Available online: http://www.phn-rsp.ca/aop-position-jae/index-eng.php (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- Sallis, J.F.; Cervero, R.B.; Ascher, W.; Henderson, K.A.; Kraft, M.K.; Kerr, J. An ecological approach to creating active living communities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, L.G.; Johnson, J.L.; Henderson, A.; Dahinten, V.S.; Hertzman, C. Examining how contexts shape young children’s perspectives of health. Child. Care. Health Dev. 2006, 33, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Gray, C.; Babcock, S.; Barnes, J.; Bradstreet, C.C.; Carr, D.; Chabot, G.; Choquette, L.; Chorney, D.; Collyer, C.; et al. Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6475–6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D.A. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karsten, L. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G.; McKendrick, J. Children’s outdoor play: Exploring parental concerns about children’s safety and the changing nature of childhood. Geoforum 1997, 28, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jago, R.; Thompson, J.L.; Page, A.S.; Brockman, R.; Cartwright, K.; Fox, K.R. Licence to be active: Parental concerns and 10–11-year-old children’s ability to be independently physically active. J. Public Health. 2009, 31, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.; McCormack, G.R.; Timperio, A.; Middleton, N.; Beesley, B.; Trapp, G. How far do children travel from their homes? Exploring children’s activity spaces in their neighborhood. Health Place 2012, 18, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.S.; Thomson, H.; Petticrew, M. Evaluation of the health effects of a neighbourhood traffic calming scheme. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2004, 58, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Bagley, S.; Ball, K.; Salmon, J. Where do children usually play? A qualitative study of parents’ perceptions of influences on children’s active free-play. Health Place 2006, 12, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Tamminen, K.A.; Clark, A.M.; Slater, L.; Spence, J.C.J.; Holt, N.N.L.; Biddle, S.; Asare, M.; Lopes, V.; Rodrigues, L.; et al. A meta-study of qualitative research examining determinants of children’s independent active free play. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Lee, H.; Millar, C.A.; Spence, J.C. ‘Eyes on where children play’: A retrospective study of active free play. Child. Geogr. 2013, 13, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C. Resurrecting free play in young children: Looking beyond fitness and fatness to attention, affiliation, and affect. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, T.A.; Meriwether, R.A.; Baker, E.T.; Watkins, L.T.; Johnson, C.C.; Webber, L.S. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: Results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handy, S.; Mokhtarian, P. Neighborhood design and children’s outdoor play: Evidence from Northern California. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 160–179. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M.; Medrich, E.A. Children in four neighborhoods: The physical environment and its effect on play and play patterns. Environ. Behav. 1980, 12, 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T. Building Cities Fit for Children. Available online: https://www.wcmt.org.uk/sites/default/files/report-documents/Gill%20T%20Report%202017%20Final_0.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Loebach, J.E.; Gilliland, J.A. Free range kids? Using GPS-derived activity spaces to examine children’s neighborhood activity and mobility. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 421–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. Shaping Urbanization for Children: A Handbook on Child-Responsive Urban Planning; UNICEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.D.; Iroz-Elardo, N.; MacLeod, K.E.; Hong, A. Pathways from built environment to health: A conceptual framework linking behavior and exposure-based impacts. J. Transp. Health 2019, 12, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, K.; Badland, H.; Kvalsvig, A.; O’Connor, M.; Christian, H.; Woolcock, G.; Giles-Corti, B.; Goldfeld, S. Can the neighborhood built environment make a difference to children’s development? Building the research agenda to create evidence for place-based children’s policy. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 16, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, M.-J.; Wendel-Vos, W.; van Oers, H.A.M.; van de Goor, I.A.M.; Schuit, A.J. Environmental determinants of outdoor play in children: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bringolf-Isler, B.; Grize, L.; Mäder, U.; Ruch, N.; Sennhauser, F.H.; Braun-Fahrländer, C. Built environment, parents’ perception, and children’s vigorous outdoor play. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2010, 50, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimbro, R.T.; Brooks-Gunn, J.; McLanahan, S. Young children in urban areas: Links among neighborhood characteristics, weight status, outdoor play, and television watching. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 668–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, D.; Sallis, J.F.; Kerr, J.; Lee, S.; Rosenberg, D.E. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, L.J.; Hopkins, W.G.; Hinckson, E.A. Associations of objectively measured built-environment attributes with youth moderate-vigorous physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 841–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Playing Fields Association. Best Play–What Play Provision Should Do for Children; National Playing Fields Association: London, UK, 2000; p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.S.; Cooper, A.R.; Griew, P.; Jago, R. Independent mobility, perceptions of the built environment and children’s participation in play, active travel and structured exercise and sport: The PEACH Project. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.M.; Kite, J.; Merom, D.; Rissel, C. Time spent playing outdoors after school and its relationship with independent mobility: A cross-sectional survey of children aged 10–12 years in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, C.; Manheimer, E.; Glanville, J. Searching for studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; The Cochrane Collaboration and John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: West Sussex, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pluye, P.; Robert, E.; Cargo, M.; Bartlett, G. Proposal: A Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool for Systematic Mixed Studies Reviews; McGill University: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, M.-J.; de Vries, S.I.; van Oers, H.A.; Schuit, A.J. Outdoor play among children in relation to neighborhood characteristics: A cross-sectional neighborhood observation study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinkert, B. Quality of the city for children: Chaos and prder. Child. Youth Environ. 2004, 14, 99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby-Toussaint, D.S.; Chi, S.-H.; Fiese, B.H. Where they live, how they play: Neighborhood greenness and outdoor physical activity among preschoolers. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2011, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels, J.S.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Droomers, M.; Hoefnagels, C.; Stronks, K.; Hosman, C.; de Vries, S. The impact of greenery on physical activity and mental health of adolescent and adult residents of deprived neighborhoods: A longitudinal study. Health Place 2016, 40, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, D.; Vaughn, A.E.; Mazzucca, S.; Bryant, M.J.; Tabak, R.G.; McWilliams, C.; Stevens, J.; Ward, D.S. Development of HomeSTEAD’s physical activity and screen time physical environment inventory. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kercood, S.; Conway, T.L.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Cain, K.L.; Sallis, J.F.; Conway, T.L.; Frank, L.D.; Cain, K.L. Parent rules, barriers, and places for youth physical activity vary by neighborhood walkability and income. Child. Youth Environ. 2015, 25, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.E.; Soltero, E.G.; Jáuregui, A.; Mama, S.K.; Barquera, S.; Jauregui, E.; Lopez y Taylor, J.; Ortiz-Hernández, L.; Lévesque, L. Disentangling associations of neighborhood street scale elements with physical activity in Mexican school children. Environ. Behav. 2016, 48, 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, A.J.; Fletcher, E.N.; Whitaker, R.C.; Anderson, S.E. Amount and environmental predictors of outdoor playtime at home and school: A cross-sectional analysis of a national sample of preschool-aged children attending Head Start. Health Place 2012, 18, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmers, T.; Broeren, S.M.; Renders, C.M.; Hirasing, R.A.; van Grieken, A.; Raat, H. A longitudinal study of children’s outside play using family environment and perceived physical environment as predictors. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmers, T.; Van Kann, D.; Gubbels, J.; Schmidt, S.; de Vries, S.; Ettema, D.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Thijs, C. Moderators of the longitudinal relationship between the perceived physical environment and outside play in children: The KOALA birth cohort study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spurrier, N.J.; Magarey, A.A.; Golley, R.; Curnow, F.; Sawyer, M.G. Relationships between the home environment and physical activity and dietary patterns of preschool children: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2008, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [Veitch, J.; Salmon, J.; Ball, K. Individual, social and physical environmental correlates of children’s active free-play: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, P.; Sithole, F.; Zhang, S.; Muhajarine, N. Neighborhood characteristics in relation to diet, physical activity and overweight of Canadian children. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2008, 3, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruizinga, A.; Bakker, I.; Stafleu, A.; De Vries, S. KOALA Deelproject “Leefstijl en Gewicht.” Ontwikkeling van de Vragenlijst “Uw Mening over eten en bewegen.” [KOALA Project “Life Style and Weight.” Development of the Questionnaire “Your Opinion about Food and Exercise.”]; TNO Quality of Life: Zeist, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Saelens, B.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Black, J.B.; Chen, D. Neighborhood-based differences in physical activity: An environment scale evaluation. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1552–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mašková, Z.; Zemek, F.; Květ, J. Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) in the management of mountain meadows. Boreal Environ. Res. 2008, 13, 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, N.; Gaston, A.; Gray, C.; Rush, E.; Maddison, R.; Prapavessis, H. The Short Questionnaire to ASsess Health-Enhancing (SQUASH) Physical Activity in Adolescents: A validation using doubly labeled water. J. Phys. Act. Health 2016, 13, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wendel-Vos, G.C.W.; Schuit, A.J.; Saris, W.H.M.; Kromhout, D. Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health-enhancing physical activity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2003, 56, 1163–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D.; Conway, T.L.; Slymen, D.J.; Cain, K.L.; Chapman, J.E.; Kerr, J. Neighborhood built environment and income: Examining multiple health outcomes. Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, K.J.; Livi Smith, A.D.; Rodriguez, D. The development and testing of an audit for the pedestrian environment. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, D.M.; Day, R.S.; Kelder, S.H.; Ward, J.L. Reproducibility and validity of the secondary level School-Based Nutrition Monitoring student questionnaire. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2003, 103, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Tarullo, L.; Aikens, N.; Sprachman, S.; Ross, C.; Carlson, B.L. FACES 2006 Study Design; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Raat, H.; Mangunkusumo, T.; Landgraf, M.; Kloek, G.; Brug, J. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of adolescent health status measurement by the Child Health Questionnaire Child Form (CHQ-CF): Internet administration compared with the standard paper version. Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, D.; Ding, D.; Sallis, J.F.; Kerr, J.; Norman, G.J.; Durant, N.; Harris, S.K.; Saelens, B.E. Neighborhood environment walkability scale for youth (NEWS-Y): Reliability and relationship with physical activity. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2009, 49, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdette, H.L.; Whitaker, R.C. A national study of neighborhood safety, outdoor play, television viewing, and obesity in preschool children. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J.; Raudenbush, S.W. Seeing disorder: Neighborhood stigma and the social construction of “broken windows. ” Soc. Psychol. Q. 2004, 67, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veitch, J.; Ball, K. The validity and reliability of an instrument to assess children’s outdoor play in various locations. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.M.; Randall, J.E.; Labonte, R.; Muhajarine, N.; Abonyi, S.; Klein, G.; Carr, T. Quality of life in Saskatoon: Achieving a healthy, sustainable community. Can. J. Urban Res. 2001, 10, 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth: Cycle 7 Survey Instruments, 2006/2007; Statistics Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006.

- Kruse, K.M.; Sugrue, T.J. The New Suburban History; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2006; p. 301. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L.D.; Engelke, P.O. The built environment and human activity patterns: Exploring the impacts of urban form on public health. J. Plan. Lit. 2001, 16, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, R.; Pendall, R.; Chen, D. Measuring sprawl and its transportation impacts. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2003, 1831, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, K.K.; Lawson, C.T. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2006, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Dev. Psychol. 1986, 22, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijtzes, A.I.; Jansen, W.; Bouthoorn, S.H.; Pot, N.; Hofman, A.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Raat, H. Social inequalities in young children’s sports participation and outdoor play. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Cities for Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. Child Friendly Cities. Available online: http://childfriendlycities.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

- Ibrahimova, A.; Wilson, D.; Pike, I. Play Spaces for Vulnerable Children and Youth: A Synthesis; BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tompa, E.; Trevithick, S.; McLeod, C. Systematic review of the prevention incentives of insurance and regulatory mechanisms for occupational health and safety. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2007, 33, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).