Abstract

In cabbage, epidermal wax plays a key role in adaptation to abiotic and biotic stresses. The glossy green cabbage variety, which has less wax, is becoming increasingly popular on the market. In this study, the highly inbred waxy cabbage HQ2-1 and the glossy green cabbage Y2-1 were sampled for fine mapping and transcriptomics analysis. In the glossy green leaf cabbage, inheritance follows a simple dominant pattern. BSA-seq and interval targeted sequencing technology identified BoCER1 as the candidate gene controlling the leaf wax trait in Brassica oleracea. Downregulated genes in the α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway and upregulated genes in the wax synthesis pathway in HQ2-1 collectively promote wax formation in HQ2-1 leaves. Cold stress induced the upregulation of α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway genes in HQ2-1, and we speculate that the upregulation of these genes may promote jasmonic acid accumulation. Our study lays a solid foundation for further understanding the regulatory mechanism of leaf wax formation in cabbage and for the translational application of breeding new glossy cabbage varieties.

1. Introduction

Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata) is an important staple biennial vegetable belonging to the Brassicaceae family, characterized by its leafy green, red, or white foliage. Having been widely cultivated for over 4000 years, it remains one of the most productive and economically valuable crops among Brassicaceae vegetables. Cabbage is rich in vitamin C, K, B6, dietary fiber, and glucosinolates, which possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer activities [1]. As one of the top ten vegetable crops worldwide, more than 70 million tons of cabbage is produced annually, supporting multiple industrial chains, including fresh consumption, processing (such as the production of kimchi and dehydrated vegetables), and livestock feed. Furthermore, crop rotation systems including cabbage positively contribute to improving soil structure and mitigating continuous cropping obstacles [2].

The epidermal wax on cabbage is an important component of its cuticle, playing a key role in the plant’s adaptation to abiotic and biotic stresses by reducing water evaporation, reflecting ultraviolet radiation, and resisting pathogen invasion [3]. The main components of epidermal wax are long-chain fatty acids, aldehydes, ketones, esters, alkanes, and other hydrophobic compounds [4]. The composition and content of epidermal wax are influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, such as light and temperature, with significant variation differences observed among different varieties [5].

Many genes important to the biosynthesis of cabbage wax have been identified. Aarts et al. [6] found that the cer1-1 mutant is characterized by a drastic decrease in products of the alkane-forming pathway (alkanes, secondary alcohols, and ketones) and a corresponding increase in aldehydes. Bourdenx et al. [7] reported that overexpression of CER1 promotes biosynthesis of very-long-chain alkanes. Pascal et al. [8] found that CER1 and CER3 can produce waxy alkanes through an aldehyde decarboxylation reaction, and their expression levels are significantly positively correlated with cuticular hydrophobicity. Wang et al. [9] identified that KCS1, KCS2, and KCS6 regulate the carbon chain elongation of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) and exhibit higher expression levels in wax alkane synthesis. Schnurr et al. [10] reported that LACS2 is the rate-limiting enzyme responsible for activating fatty acids in wax ester synthesis. Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, Cao et al. [11] successfully knocked out the KCS and CER genes, significantly reducing wax content and verifying their function. Yang et al. [12] discovered that overexpression of CER1 improves drought tolerance in kale by regulating cuticular wax biosynthesis. Song et al. [13] reported that reducing the wax content can enhance leaf tenderness, thereby satisfying the requirements of fresh consumption markets. Although many genes involved in leaf wax formation have been identified, the differentially expressed structural genes in the key metabolic pathway of leaf wax formation have not been systematically investigated.

A series of studies have reported that waxes support resistance to low-temperature stress in different types of plants. Ladaniya MS [14] reported that wax-coated mandarin fruit has a longer shelf life when stored at a chilling temperature with intermittent warming. Zhu et al. [15] reported that in tea plants, n-hexadecanoic acid is positively related to cold resistance. Darré et al. [16] found that wax treatment enhances tolerance to chilling injury in red bell pepper. Bourdenx et al. [7] reported that overexpression of CER1 enhances resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Our previous research also found that waxy cabbage seedlings are more tolerant to low temperatures [17]. However, how CER1 mediates the response of waxy cabbages to low temperatures via altering lipid metabolism remains unclear.

In this study, we analyzed the genetic characteristics of waxy leaf cabbages, identifying BoCER1 as the candidate gene for the waxy leaf phenotype in HQ2-1. We further examined the gene expression changes involved in wax formation on cabbage leaves and predicted the conversion of α-linolenic acid to jasmonic acid under cold stress. Our study lays a solid foundation for understanding the regulatory mechanism of leaf wax formation in cabbage.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

The highly inbred line of waxy leaf cabbage HQ2-1 and the glossy green cabbage Y2-1 were used as parents to generate F1-1, F1-2, BC1-1, BC1-2, and F2 populations for inheritance studies, genetic mapping, and transcriptomic analysis to identify differentially expressed genes. The F1-1 population was created by crossing HQ2-1 with Y2-1, and the BC1-1 population was generated by crossing individual F1-1 plants with HQ2-1. The F1-2 population was created by crossing Y2-1 with HQ2-1, and the BC1-2 population was generated by crossing individual F1-2 plants with Y2-1. The F1-1 and F1-2 populations were each used to generate F2 populations separately. Healthy seeds from all individuals were sown in 72-hole plates filled with seedling substrate, and the plates were placed in a sunlit greenhouse. When the seedlings reached the four-leaf-one-heart stage, they were transplanted into the field at Qinghai University, where they were managed using normal water and fertilizer until the cabbage heads became firm. All plant materials used in this study were provided by the Vegetable Breeding Team, Institute of Horticulture, Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Qinghai University.

2.2. Genetic Characteristics of Wax Traits of Cabbage Leaves

The wax phenotypes of F1-1, F1-2, BC1-1, BC1-2, and F2 individuals were investigated when the cabbage seedlings reached the three-leaf stage and rosette stage, separately. The numbers of waxy and wax-free plants in the F1 and F2 generations, respectively, were counted, and the segregation ratio was calculated.

2.3. Fine Mapping

Thirty individual plants with thick wax and thirty individual wax-free plants from the F2 population were selected to construct the waxy and wax-free pools, respectively. Samples from the HQ2-1, Y2-1, and waxy and wax-free pools were subjected to re-sequencing and BSA-sequencing by Beijing Biomarker Tech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China), following the instructions of Wang et al. [18].

Based on the initial positioning results, polymorphic SNP markers with PolyHighRes sequencing data were converted into KASP markers. The KASP primers were designed using the PolyMarker website (http://www.polymarker.info/, accessed on 29 December 2025), and all primers were synthesized by Baimaike Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). For each SNP locus, two forward primers and one reverse universal primer were designed and named Primer-A, Primer-B, and Primer-C, respectively. Primer-A and Primer-B represented the two alleles of the SNP, with FAM and HEX fluorescent labels added. Genotype analysis of the two parent samples was performed using Primer Mix to screen for polymorphic KASP primers. Subsequently, the genotype of the F2 population was analyzed using these polymorphic KASP markers. Fluorescence data from the PCR reaction were read using a microplate reader, and genotype data at different loci were analyzed using KlusterCaller software (version 4.1). Interval-targeted sequencing technology was then employed to further sequence the 904 kb candidate interval.

2.4. Candidate Gene Prediction and Cloning

The physical positions of flanking markers linked to leaf waxy traits were determined using the BLAST (version 2.17.0+) network online service, and candidate gene prediction was performed with the GBrowse tool from BRAD (http://brassicadb.cn/#/BLAST/, accessed on 29 December 2025). Specific primers for the candidate gene were designed based on the reference genome of B. oleracea [19]. The candidate gene sequences were cloned from HQ2-1. PCR products were purified using a TaKaRa MiniBEST agarose Gel DNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) and used for TA cloning. The purified PCR products were inserted into the pMD19-T Simple Vector (TaKaRa, Japan) and transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Recombinant plasmids were sequenced by Aoke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Yangling, China), and sequence alignment was conducted using DANMAN software (version 10.0.2.100). The function of the predicted gene was searched using the BLASTP tool (version 2.17.0+) from NCBI.

2.5. Functional Marker Development

According to the re-sequencing results, a large fragment deletion occurred in the candidate gene region of HQ2-1 and Y2-1. Therefore, a specific primer pair was designed and synthesized to amplify a functional marker, BoCER1. PCR amplifications were performed to detect CER1 variations in the two parent cabbage plants and F2 individuals.

2.6. Transcriptome Analysis of HQ2-1 and Y2-1 Leaves

Healthy HQ2-1 and Y2-1 seeds were sown in 72-hole plates filled with seedling substrate, and the plates were placed in a sunlit greenhouse. When the seedlings reached the four-leaf-one-heart stage, their leaves were collected for transcriptome analysis. Three biological replicates were set for each sample, with each replicate consisting of eight individual plants. RNA extraction, library construction, library quality control, RNA sequencing, sequencing data quality control, and reference genome comparison were all performed by Wuhan Genoseq Technology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). An Illumina HiSeq Paired-end 150 bp platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was used for sequencing. Correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) were also conducted. DESeq2 v1.10.1 software was employed to identify differentially expressed genes using the following criteria: |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05.

2.7. Stress Treatment

Healthy waxy cabbage HQ2-1 seedlings with uniform growth at the four-leaf-one-heart stage were subjected to stress treatment. For PEG-simulated drought stress, the cabbage seedlings were immersed in a 25% PEG-6000 solution and placed in a light incubator at 22 °C/15 °C with 70% humidity [20,21]. For cold stress, the seedlings were transferred to a light incubator at 4 °C with 70% humidity [22]. For heat stress, they were moved to a light incubator at 35 °C with 70% humidity [23]. To simulate salt–alkali stress, the seedlings were immersed in a 150 mmol/L NaHCO3 solution and placed in a light incubator at 22 °C/15 °C with 70% humidity. The treatment durations were 48, 96, and 144 h.

2.8. Determination of Free Fatty Acids and Data Analysis

Cabbage leaf samples weighing 0.1 g were collected in a centrifuge tube, and a free fatty acid (FFA) content detection kit (Shanghai Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Detection Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to determine their free fatty acid content. There were three replicates for each sample, with each replicate containing 5 individual plants. Microsoft Excel 2019 was used for data organization, and Origin 2021 software was used to plot graphs.

2.9. Low-Temperature Treatment for Transcriptome Analysis

Healthy HQ2-1 and Y2-1 seeds were sown in 72-hole plates filled with seedling substrate, and the plates were placed in a sunlit greenhouse. When the seedlings reached the three-leaf-one-heart stage, they were transferred to an artificial climate chamber for low-temperature stress treatment. The treatment conditions were set as follows: day/night temperatures of 10 °C/5 °C, day/night photoperiods of 14 h/10 h with a light intensity of 12,000 Lx, 60% air relative humidity, and treatment maintained for 7 days. The control group had day/night temperatures of 20 °C/10 °C, with all other conditions being consistent. Three biological replicates were established for each sample, with each replicate containing 8 individual plants. Differentially expressed gene identification analysis was performed following the methods used in the transcriptome analysis of HQ2-1 and Y2-1 leaves.

3. Results

3.1. Genetic Characteristics of Waxy Leaf Cabbages

The highly inbred waxy leaf cabbage HQ2-1 (P1) and the glossy green cabbage Y2-1 (P2) (Figure 1) were used as parents to generate F1-1 and F1-2 cabbages. The wax phenotype of F1-1, F1-2, BC1-1, BC1-2 and F2 individuals was investigated when the cabbage seedlings reached the three-leaf stage and rosette stage, separately. Single plants with consistent wax phenotype identification were used for subsequent studies. All F1-1 (P1 × P2) and F1-2 (P2 × P1) individuals were found to be wax-free, indicating that the wax-free trait is dominant, without cytoplasmic effects. Due to the similarity in phenotype between F1-1 and F1-2 individuals, F2 populations derived from F1-1 and F1-2 cabbages were combined when calculating the separation ratio. In the F2 separation population, the ratio of wax-free to waxy plants was 1191:384, which is approximately 3.102:1. Chi-square testing confirmed that this ratio fits a 3:1 distribution (χ2 = 0.072, χ20.05 = 3.841), suggesting that the wax-free trait in the Y2-1 cabbage is controlled by a single dominant gene (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Genetic characteristics of wax deficiency trait in parental materials.

Table 1.

Genetic analysis of wax-free trait phenotype.

In the BC1-1 [(P1 × P2) × P1] separation population, an obvious segregation ratio of 1:1 was observed, indicating that the genotype of BC1-1 individuals was heterozygous dominant and homozygous recessive as Waxwax and waxwax. In the BC1-2 [(P1 × P2) × P2] population, all individuals were found to be wax-free, indicating that the genotype of BC1-2 individuals was homozygous dominant and heterozygous dominant as WaxWax and Waxwax (Table 1). All F1-1 (P1 × P2) and F1-2 (P2 × P1) individuals were heterozygous dominant (Waxwax). Thus, we inferred that the waxy phenotype in HQ2-1 (P1) was homozygous recessive (waxwax) and the wax-free phenotype in Y2-1 (P2) was homozygous dominant (WaxWax).

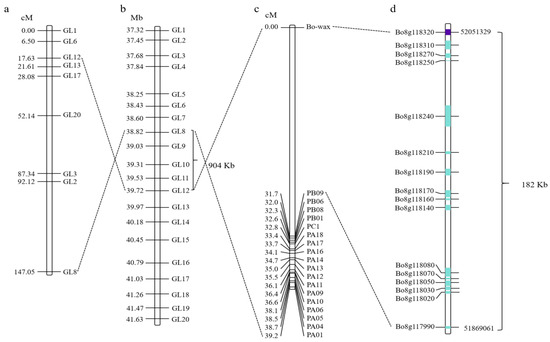

3.2. Fine Mapping of Candidate Genes for Wax Traits in Cabbage Leaves and Identification of Candidate Genes

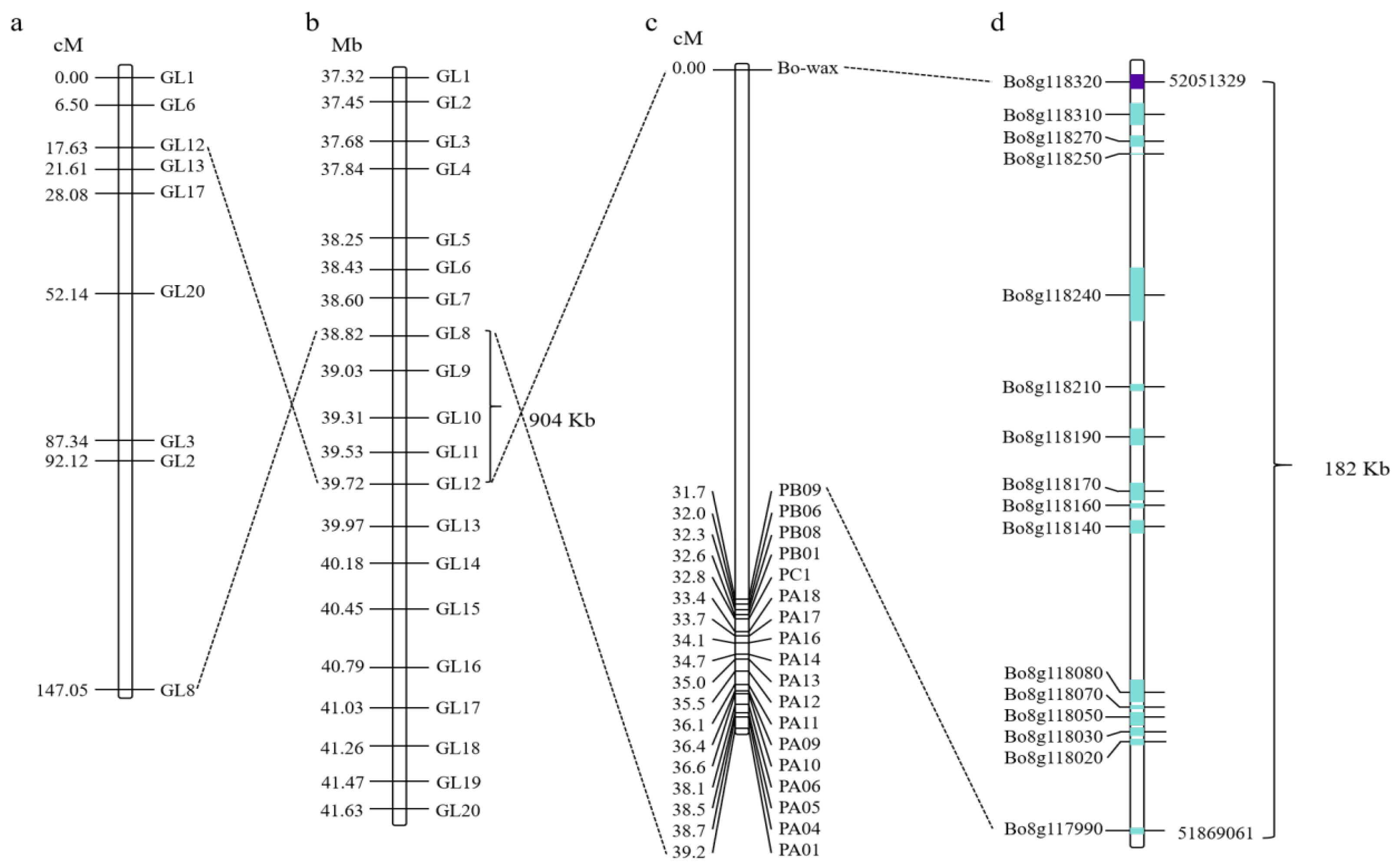

Based on re-sequencing of parental DNA and BSA pool sequencing, the gene responsible for wax formation on the surface of cabbage leaves was initially located within the GL8-GL12 interval on chromosome C08. Subsequently, Competitive Allele-Specific PCR (KASP) markers were used to further map the candidate gene for wax formation. Through collinearity analysis, the candidate gene region was narrowed to a 904 kb range (Figure 2a,b). Interval-targeted sequencing technology was used to further sequence the 904 kb candidate interval; finally, the candidate gene for wax formation was located in a 182 kb region (Figure 2c,d). A total of 16 annotated genes were identified in this 182 kb region (Supplementary Table S1). Based on the gene annotation of the B. oleracea reference genome, three of these sixteen genes may be candidates, including Bo8g117990 (Sec14p-like phosphatidylinositol transfer family protein gene), Bo8g118020 (Phosphatidylinositol N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase subunit P-like protein gene), and Bo8g118320 (CER1 gene associated with stem epicuticular wax production and pollen fertility). Furthermore, based on high-throughput targeted sequencing data, the read coverage of the target gene region in HQ2-1 and Y2-1 revealed that Bo8g118320 in Y2-1 had a deletion of the 3′ end DNA fragment. Therefore, we hypothesized that Bo8g118320 is the candidate gene controlling leaf wax formation. Gene function annotation indicated that Bo8g118320 encodes an aldehyde decarboxylase involved in cutin, suberin, and wax biosynthesis within the lipid metabolic pathway, which is also known as CER1.

Figure 2.

Fine mapping of candidate genes responsible for wax traits of cabbage leaves. (a,b) The wax formation gene was initially mapped within the GL8-GL12 interval on chromosome C08. (c,d) The candidate gene for wax formation was mapped to a region of 182 kb using interval targeted sequencing technology. The numbers on the left side of the bars in (a–c) represent genetic distances. The line connecting the two diagrams indicates that this is the same molecular marker. The length of the blue box indicates the gene length, while the purple box denotes the candidate gene.

3.3. Candidate Gene Clones and Molecular Marker Design

Based on the B. oleracea reference genome, the gDNA and CDS of Bo8g118320 from HQ2-1 were cloned, with the full-length gDNA being 3516 bp and the CDS being 2055 bp. Genetic structure analysis revealed that the gene contains 10 exons and 9 introns. Due to a large fragment deletion of Bo8g118320 in Y2-1, we were unable to obtain complete gDNA and CDS sequences for Bo8g118320 in Y2-1. An analysis of physicochemical properties indicated that Bo8g118320 encodes an aldehyde decarboxylase with 684 amino acids, which is a stable protein. Analysis of the signal peptide and transmembrane structure domain revealed that the aldehyde decarboxylase polypeptide chain lacks a signal peptide but contains five transmembrane helical structure regions.

Based on the sequence of HQ2-1 and the high-throughput targeted sequencing results for Y2-1, a functional dominant molecular marker, F-R2, was designed. When this marker was used to amplify bands in waxy parents and waxy individual plants, bands were detected, but no bands were found in wax-free parents and wax-free individual plants (Figure S1).

3.4. Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes Involved in Wax Synthesis in HQ2-1 and Y2-1

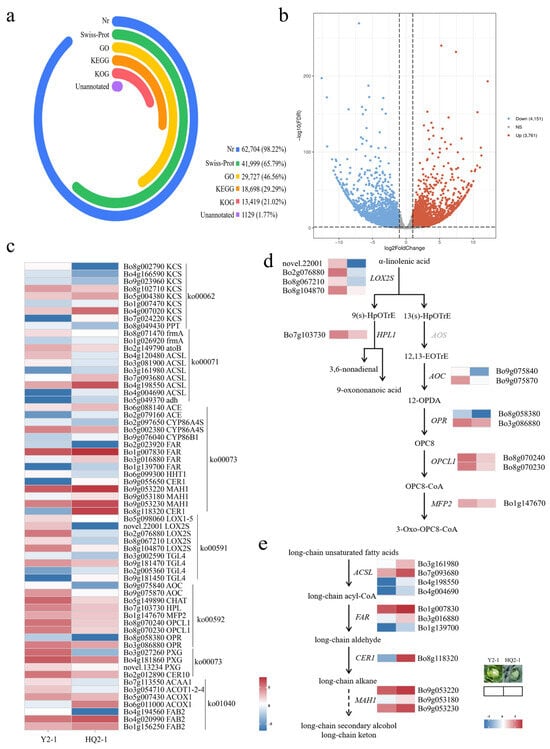

To further explore the molecular mechanism underlying changes in leaf wax formation-related genes in cabbage, transcriptome analysis was performed using leaves from the waxy cabbage HQ2-1 and the wax-free cabbage Y2-1. Based on six samples, with an average of 11.45 Gb per sample, a total of 68.73 Gb of clean data were obtained, for which the mean Q30 value was 93.30%. The reads obtained from sequencing were aligned to the Brassica oleracea reference genome (v2.1.25), with an average alignment rate of 88.40%, in which 84.30% of the reads could be uniquely mapped to the reference genome (Supplementary Table S2). Correlation analysis of biological replicates in RNA-Seq experiments revealed that three replicates under identical treatments clustered together, while materials treated at different temperatures showed significant dispersion, confirming the high reproducibility of the test samples and marked differences among treatments (Figure S2).

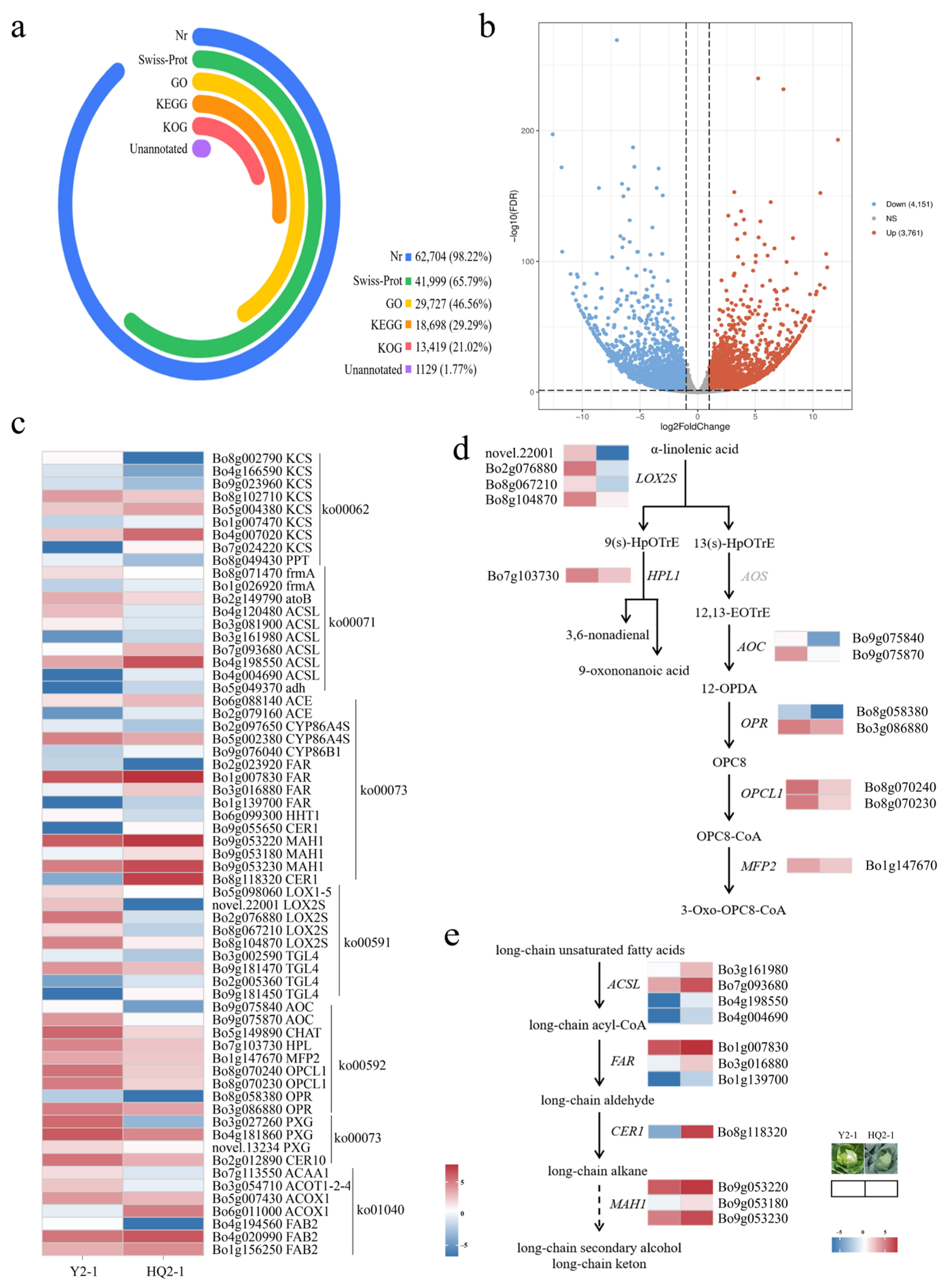

Gene sequences were compared with those in KEGG, NR, Swiss-Prot, GO, KOG, and other databases, with annotation rates of 35.27% (7103 genes), 94.49% (19,029 genes), 65.95% (13,281 genes), 43.56% (8772 genes), and 28.14% (5668 genes), respectively, while 5.49% (1105 genes) remained unannotated (Figure 3a). RNA-Seq results showed that a total of 7912 genes were identified as differentially expressed genes. Among these, 3761 genes were upregulated and 4151 genes were downregulated at HQ2-1 (Figure 3b, Supplementary Table S3). Using the KEGG database, six pathways related to wax formation were identified, including cutin, suberine and wax biosynthesis (ko00073), alpha-linolenic acid metabolism (ko00592), linoleic acid metabolism (ko00591), biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids (ko01040), fatty acid elongation (ko00062), and fatty acid degradation (ko00071). In a comparison of HCK and YCK, a total of 63 differentially expressed genes were found in these six pathways, among which 26 were significantly upregulated and 37 were significantly downregulated in HCK (Figure 3c, Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 3.

Identification of differentially expressed genes involved in wax synthesis in HQ2-1 and Y2-1. (a) Gene sequence annotation. (b) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes between HQ2-1 and Y2-1. (c) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes involved in wax synthesis. (d) Reconstructed linolenic acid metabolic pathway based on the differentially expressed genes. (e) Reconstructed wax biosynthesis pathway based on the differentially expressed genes. Note: The gene expression heatmaps in (d,e) were derived from (c). 9(s)-HpOTrE: 9-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid. 13(s)-HpOTrE: 13-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid. 12,13-EoTrE: 12,13-Epoxyoctadeca-9,11,15-trienoic acid. 12-OPDA: 12-Oxophyto-10,15-dienoate. OPC8: 8-[(1S,2S)-3-Oxo-2-[(Z)-pent-2-enyl]cyclopentyl] octanoic acid.

Based on the differentially expressed genes, the waxy formation pathway was reconstructed. In the linolenic acid metabolic pathway, α-linolenic acid enters two pathways under the catalysis of different enzymes. Four LOX2S genes (Bo2g076880, Bo8g067210, Bo8g104870, and novel.22001), which encode lipoxygenase and catalyze the conversion of α-linolenic acid into 9-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid (9(s)-HpOTrE) and 13-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid (13(s)-HpOTrE), were significantly downregulated in HCK. The HPL gene, which encodes linolenate hydroperoxidelyase and catalyzes the conversion of 9(s)-HpOTrE into 9-oxononanoic acid and 3,6-nonadienal, was also significantly downregulated in HCK. Meanwhile, the AOS gene, which encodes hydroperoxide dehydratase and catalyzes the conversion of 13(s)-HpOTrE into 12,13-Epoxyoctadeca-9,11,15-trienoic acid (12,13-EoTrE), showed no significance in the comparison between HCK and YCK. Two copies of AOC genes (Bo9g075840 and Bo9g075870) encoding allene oxide cyclase, two copies of OPR genes (Bo8g058380 and Bo3g086880) encoding 12-oxophytodienoic acid reductase, two copies of OPCL1 genes (Bo8g070240 and Bo8g070230) encoding OPC-8:0 CoA ligase 1, and the MFP2 gene (Bo1g147670) encoding enoyl-CoA hydratase were all significantly downregulated in HCK (Figure 3d).

In the wax biosynthesis pathway, long-chain unsaturated fatty acids are converted into long-chain acyl-CoA under the catalysis of long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases. In the comparison of HCK vs. YCK, four ACSL genes (Bo3g161980, Bo7g093680, Bo4g198550, and Bo4g004690), which encode long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases, were significantly upregulated in HCK. Under the catalysis of acyl-CoA reductase, long-chain acyl-CoA is converted into long-chain aldehyde. Three FAR genes (Bo1g007830, Bo3g016880, and Bo1g139700), which encode acyl-CoA reductase, were significantly upregulated in HCK. The long-chain aldehyde was converted into a long-chain alkane under the catalysis of aldehyde decarbonylase. The CER1 gene encoding aldehyde decarbonylase was significantly upregulated in HCK but nearly absent in YCK. The long-chain alkane was converted into a long-chain secondary alcohol and long-chain ketone under the catalysis of midchain alkane hydroxylase, and three copies of the MAH1 genes (Bo9g053220, Bo9g053180, and Bo9g053230) encoding midchain alkane hydroxylase were significantly upregulated in HCK (Figure 3e).

Expression of the CER1 gene, which encodes aldehyde decarbonylase, was directly blocked in YCK. We hypothesized that down-regulated expression of CER1 in YCK may inhibit the conversion of long-chain aldehydes to long-chain alkanes, thereby suppressing the formation of long-chain alkanes, long-chain secondary alcohols, long-chain ketones, and long-chain diketones.

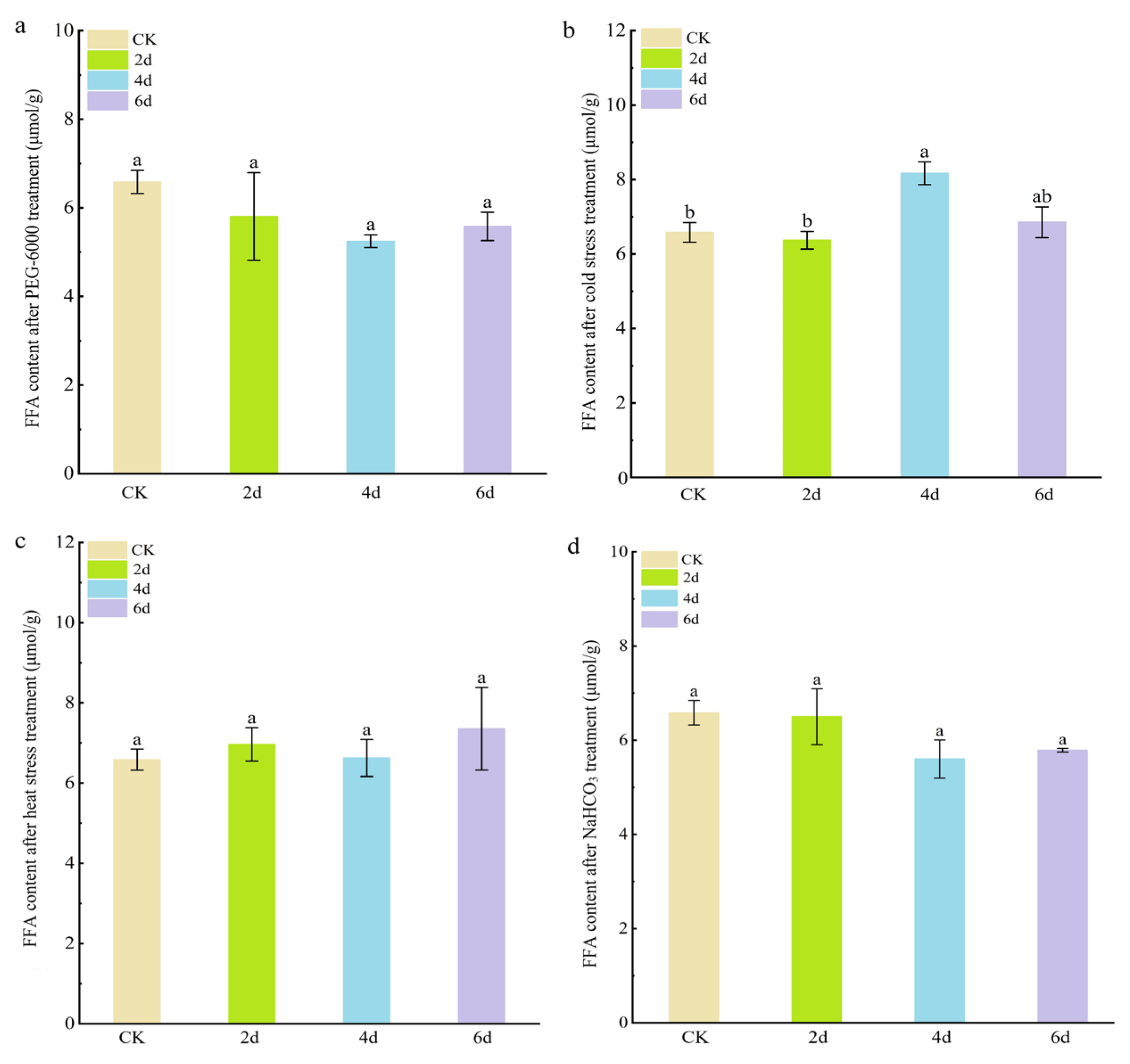

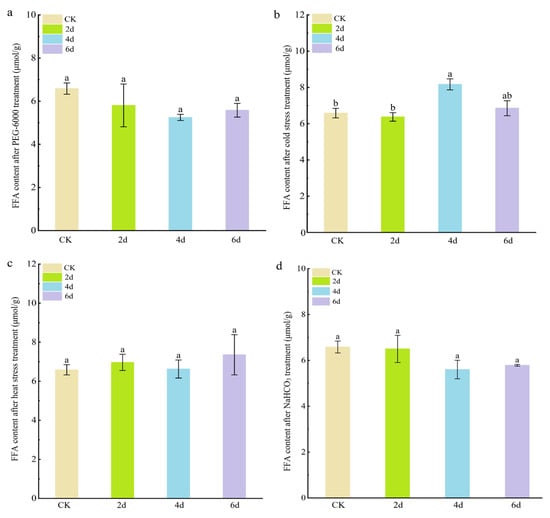

3.5. Leaf FFA Response to Stress in the Waxy Cabbage HQ2-1

Free fatty acids (FFAs) are the main components of leaf wax, so we investigated changes in FFA content to measure changes in leaf wax. The results showed that the FFA content in cabbage leaves did not change significantly after PEG-6000 simulated drought stress, heat stress, or NaHCO3 stress (Figure 4). However, under cold stress treatment, the FFA content in cabbage leaves was significantly higher after 4 and 6 days (8.17 ± 0.30 μmol g−1 FW and 6.85 ± 0.42 μmol g−1 FW) compared to the control (6.58 ± 0.45 μmol g−1 FW). These results suggest that cold stress can significantly promote the biosynthesis of free fatty acids.

Figure 4.

Free fatty acid content of cabbage seedlings after adverse stress treatment. (a) PEG-6000 simulated drought stress treatment. (b) Cold stress treatment. (c) Heat stress treatment. (d) NaHCO3 stress treatment. The letters above the columns indicate significance at p < 0.05.

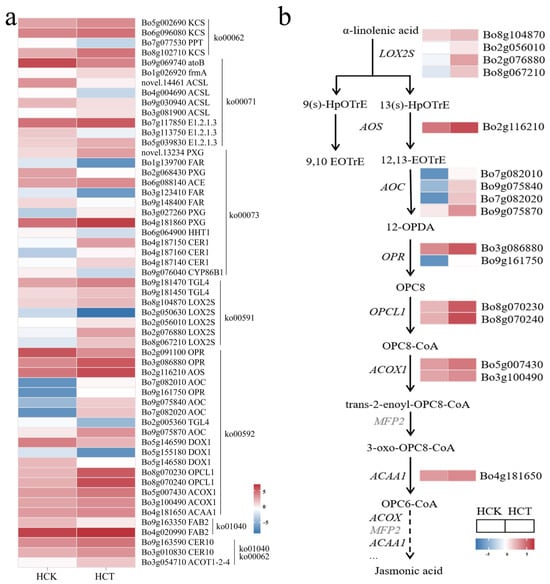

3.6. Cold Stress Induced Upregulated Expression of α-Linolenic Acid Metabolic Pathway

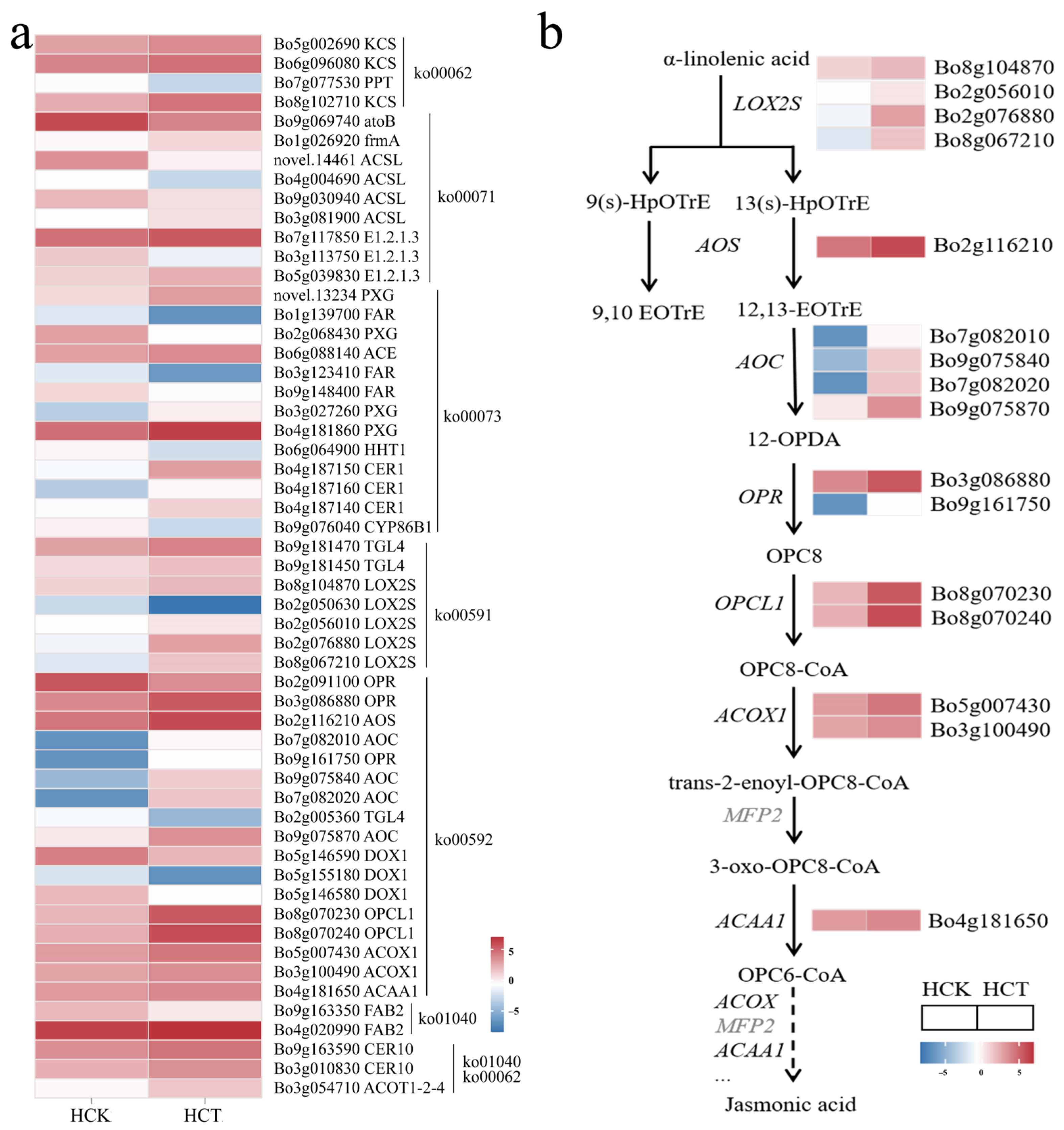

To clarify the regulatory network of genes related to wax synthesis in response to cold stress, we used transcriptome sequencing to analyze differentially expressed genes in the waxy cabbage HQ2-1 under cold stress (HCT). A total of 8173 differentially expressed genes were identified, with 4129 upregulated and 4044 downregulated at HCT (Supplementary Table S5). Based on the six pathways related to wax formation, a total of 55 differentially expressed genes involved in wax synthesis were identified under cold stress, including 35 significantly upregulated genes and 20 significantly downregulated genes (Figure 5a, Supplementary Table S6).

Figure 5.

Differentially expressed gene analysis of HQ2-1 under cold stress. (a) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in HCT vs. HCK. (b) Reconstructed linolenic acid metabolic pathway based on differentially expressed genes. Note: Heatmaps of gene expression in (b) were derived from (a). 9(s)-HpOTrE: 9-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid. 13(s)-HpOTrE: 13-hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid. 12-OPDA: 12-Oxophytodienoate. 12,13-EoTrE: 12,13-Epoxyoctadeca-9,11,15-trienoic acid. OPC8: [(1S,2S)-3-Oxo-2-[(Z)-pent-2-enyl]cyclopentyl] octanoic acid.

Among these 55 differentially expressed genes, 17 were enriched in the linolenic acid metabolic pathway. Thus, we reconstructed the linolenic acid metabolic pathway under cold stress in HQ2-1 leaves. Four LOX2S genes (Bo8g104870, Bo2g056010, Bo8g067210 and Bo2g076880), one AOS gene (Bo2g116210), four AOC genes (Bo7g082010, Bo9g075840, Bo7g082020 and Bo9g075870), two OPR genes (Bo3g086880 and Bo9g161750), and two OPCL1 genes (Bo8g070230 and Bo8g070240) were all significantly upregulated in HCT. The synergistic action of these genes converts α-linolenic acid into OPC8-CoA. Upregulated expression of these genes in HCT might promote the accumulation of OPC8-CoA. OPC8-CoA was then converted into isojasmonic acid CoA through the catalytic action of a series of enzymes, including acyl-CoA oxidase, enoyl-CoA hydratase, and acetyl-CoA acyltransferase. Two ACOOX1 genes (Bo3g100490 and Bo5g007430), encoding acyl-CoA oxidase, and the ACAA1 gene (Bo4g181650), encoding acetyl-CoA acyltransferase, were all significantly upregulated in HCT. In contrast, the MFP2 gene, which encodes enoyl-CoA hydratase, showed no significant difference when comparing HCT and HCK (Figure 5b).

Based on the gene expression level and the reconstructed linolenic acid metabolic pathway, we suspected that the upregulated genes in HCT promote the metabolic pathways of α-linolenic acid, thereby promoting the accumulation of jasmonic acid on the surface of HQ2-1 leaves under cold stress. The upregulated expression of genes in the α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway of HQ2-1 under cold stress also indirectly confirms that cold stress can significantly promote fatty acid biosynthesis.

4. Discussion

4.1. Wax Biosynthesis Candidate Genes in Brassica Crops

Many genes controlling wax synthesis in Brassica crops have been identified. In cabbage, Liu et al. [24] and Dong et al. [25] identified one candidate gene, Bol018504, which confers the glossy trait and is a homolog of CER1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Liu et al. [26] found that a 2722 bp insertion in the first intron of Bol018504 occurs in the glossy mutant. However, Dong et al. [25] found no difference in the Bol018504 sequence between CGL-3 and the wild type (WT). Liu et al. [26] reported that a single recessive locus, BoWax1, controls the glossy green trait. Using genetic mapping, Han et al. [27] identified a candidate gene, BoGL5, that is homologous to Arabidopsis CER2, which is essential for epicuticular wax biosynthesis in broccoli. Wang et al. [28] identified a single recessive gene, Bol026949, that controls the glossy green trait in cabbage and found that Bol026949 may participate in cuticular wax production by regulating the transcript levels of genes involved in post-translational cellular processes and phytohormone signaling.

In this study, we identified a dominant single gene, Bo8g118320, that confers the glossy green trait in cabbage. This gene is a homolog of CER1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Interval targeted sequencing of the candidate region revealed a large fragment deletion in Bo8g118320 in the glossy green cabbage Y2-1. In B. napus, Liu et al. [29] identified a lipid transfer protein gene, BraLTP1, that is involved in epicuticular wax deposition; overexpression of this gene in B. napus reduced wax deposition on leaves, with detailed wax analysis showing a 17–80% reduction in various major wax components. Liu et al. [30] identified that BnA1.CER4 and BnC1.CER4 cDNA are fatty acyl-coenzyme A reductase genes with a preference for branched substrates, which induce the accumulation of primary alcohols with chain lengths of 26 carbons. Wen et al. [31] identified a dominant GL and confirmed a drastic reduction in total wax content. Wax compositional analysis showed increased aldehydes but significant decreases in alkanes, ketones, and secondary alcohols. Ni et al. [32] reported that BnUC1 is a key regulator of epidermal wax biosynthesis and lipid transport. Overexpression of BnUC1mut in ZS11 (Zhongshuang11) significantly reduced leaf epidermal wax content, resulting in curled-up and glossy leaves. In Chinese cabbage, Yang et al. [33] identified the BrWAX2 gene, which is involved in epicuticular wax biosynthesis, through map-based cloning. They found that BrWAX2, in addition to reduced expression of other genes in the alkane-forming pathway, causes the glossy phenotype. Huo et al. [34] identified an AP2 transcription factor called BrSHINE3, which regulates wax accumulation in non-heading Chinese cabbage. Li et al. [35] discovered that an A BrLINE1-RUP insertion in BrCER2 alters epicuticular wax biosynthesis. Song et al. [36] reported that a BrKCS6 mutation confers leaf brightness.

Together, these results suggest a series of genes involved in wax biosynthesis, including structural genes and transcription factors. Different genes may influence leaf wax formation through distinct metabolic pathways.

4.2. Wax Biosynthesis Pathway

Wax biosynthesis occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum [37]. First, C16 and C18 fatty acyl–acyl carrier proteins are hydrolyzed by acyl-ACP thioesterases and then converted into coenzyme A derivatives by long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases [10,38,39,40]. Second, the saturated C16 and C18 fatty acyl-CoA is subsequently transformed into very long-chain fatty acids by FA elongase complexes. This transformation is catalyzed by a series of enzymes: 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase (KCS) mediates the formation of 3-ketoacyl-CoA, 3-ketoacyl-CoA reductase (KCR) reduces this intermediate to 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydratase (HCD) dehydrates it to trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA, and trans-2,3-enoyl-CoA reductase (ECR) reduces the enoyl-CoA to a longer-chain fatty acyl-CoA [41,42,43,44,45,46]. Subsequently, very-long-chain fatty acids are converted into very-long-chain fatty acid-acyl-CoAs longer than C28 through the catalysis of CER2, with CER2-like proteins functioning together with CER6 [47,48,49]. Finally, the synthesized very-long-chain fatty acid-acyl-CoAs are transformed into aldehydes, alkanes, secondary alcohols, and ketones by CER1, CER3, and the CYTOCHROME B5 (CYTB5) complex [50,51,52,53]. In this study, the downregulated expressed genes in the α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway and the upregulated expressed genes (ACSL, FAR, CER1 and MAH1) in the wax synthesis pathway in HQ2-1 jointly promote wax formation in HQ2-1 leaves.

In B. napus, Jin et al. [54] classified differentially expressed genes involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis according to their function in plant acyl lipid metabolism, including fatty acid-related pathways, wax and cutin biosynthesis pathways, and wax secretion. Wang et al. [18] identified a negatively regulated gene, BnaC9.DEWAX1, which is involved in wax biosynthesis via the transcriptional suppression of BnCER1-2 expression. In cabbage, Laila et al. [55] reported that the higher levels of expression of LTP2 genes observed in a less waxy cabbage line and the higher level expression of the CER3 gene in a more waxy line were likely associated with the lower and higher wax contents, respectively, in those two lines. These results suggest that both structural genes and transcription factors can regulate wax synthesis, although the regulatory mechanism of transcription factors involved in wax synthesis requires further exploration.

4.3. Regulation of Wax Biosynthesis in Response to Temperature

Environmental conditions such as drought, humidity, UV-B irradiation, extended darkness, and extreme salinity and temperature alter total wax accumulation and composition [56]. There is sufficient evidence linking cuticular wax biosynthesis to plant adaptability to temperature stress. Shephered and Griffths [56] reported that low temperatures (15–17 °C) or cold treatment (4 °C) significantly increased the total wax content in the leaves of B. napus and Arabidopsis. He et al. [57] found that KCR1, LACS2, and ACC1 upregulation significantly increased very-long-chain fatty acids in T. salsuginea after 4 °C treatment. We also found that cold stress could significantly promote the biosynthesis of free fatty acids. Additionally, upregulation of genes in HQ2-1 under cold stress promoted α-linolenic acid metabolism pathway, indicating that more jasmonic acid may accumulate on the surface of HQ2-1 leaves under cold stress. These results suggest that cold-induced changes in the cuticle help protect plants from winter drought, although alterations in total wax accumulation and composition vary depending on the cold-treated plant species.

Our findings indicated that BoCER1 controls leaf wax traits in B. oleracea and that upregulation of genes in HQ2-1 under cold stress promotes α-linolenic acid metabolism, thus promoting the accumulation of jasmonic acid on the surface of HQ2-1 leaves under cold stress and the accumulation of free fatty acids.

5. Conclusions

BoCER1 was identified as a candidate gene for wax biosynthesis in the waxy cabbage HQ2-1. High levels of BoCER1 expression promoted the downregulation of genes in the α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway and the upregulation of genes in the wax synthesis pathway in HQ2-1. Together, these changes contribute to wax formation in HQ2-1 leaves. Because the genes upregulated in HQ2-1 under cold stress promoted α-linolenic acid metabolic pathways, it is suspected that cold stress promotes the accumulation of jasmonic acid on the surface of HQ2-1 leaves. This study analyzed the gene expression changes involved in the formation of wax on cabbage leaves and confirmed that cold stress can induce the upregulation of α-linolenic acid metabolic pathway genes in cabbage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb48020152/s1.

Author Contributions

D.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft, and Funding acquisition; Y.R.: Methodology, Software, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. C.D.: Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, and Investigation. J.W.: Conceptualization, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing; Q.L.: Investigation, Formal Analysis, and Data Curation; B.L.: Methodology, Software, and Writing—original draft; L.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by a Project of Laboratory of Research and Utilization of Germplasm Resources in Qinghai–Tibet Plateau (2025).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available from the NCBI Short Read Archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA1370458.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Beijing Biomarker Tech Co., Ltd., and Wuhan Genoseq Technology Co., Ltd. for their technological support and all those who participated in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gelaye, Y.A. Systematic Review on Effects of Nitrogen Fertilizer Levels on Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) Production in Ethiopia. Sci. World J. 2024, 2024, 6086730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayegamiye, A.N.; Nyiraneza, J.; Grenier, M.; Bipfubusa, M.; Drapeau, A. The benefits of crop rotation including cereals and green manures on potato yield and nitrogen nutrition and soil properties. Adv. Crop Sci. Technol. 2017, 5, 1000279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, D.; Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Z.H. Molecular and Evolutionary Mechanisms of Cuticular Wax for Plant Drought Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacson, T.; Kosma, D.K.; Matas, A.J.; Buda, G.J.; He, Y.; Yu, B.; Pravitasari, A.; Batteas, J.D.; Stark, R.E.; Jenks, M.A.; et al. Cutin deficiency in the tomato fruit cuticle consistently affects resistance to microbial infection and biomechanical properties, but not transpirational water loss. Plant J. 2009, 60, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrzad, F.; Jowkar, A. Gene expression analysis of drought tolerance and cuticular wax biosynthesis in diploid and tetraploid induced wallflowers. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aarts, M.G.; Keijzer, C.J.; Stiekema, W.J.; Pereira, A. Molecular characterization of the CER1 gene of Arabidopsis involved in epicuticular wax biosynthesis and pollen fertility. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 2115–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdenx, B.; Bernard, A.; Domergue, F.; Pascal, S.; Leger, A.; Roby, D.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; et al. Overexpression of Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM1 promotes wax very-long-chain alkane biosynthesis and influences plant response to biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, S.; Bernard, A.; Deslous, P.; Gronnier, J.; Fournier-Goss, A.; Domergue, F.; Rowland, O.; Joubès, J. Arabidopsis CER1-LIKE1 Functions in a Cuticular Very-Long-Chain Alkane-Forming Complex. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Si, K.; Xu, R.; He, Y.; Zhu, F.; Cheng, Y. Function and transcriptional regulation of CsKCS20 in the elongation of very-long-chain fatty acids and wax biosynthesis in Citrus sinensis flavedo. Hortic. Res. 2022, 9, uhab027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, J.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. The acyl-CoA synthetase encoded by LACS2 is essential for normal cuticle development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2004, 16, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Sun, H.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhuang, M.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Ji, J. Genome-wide identification of the ECERIFERUM (CER) gene family in cabbage and critical role of BoCER4.1 in wax biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.U.; Kim, H.; Kim, R.J.; Kim, J.; Suh, M.C. AP2/DREB Transcription Factor RAP2.4 Activates Cuticular Wax Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis Leaves Under Drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Liu, C.; Fang, B.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. Identification of an epicuticular wax crystal deficiency gene Brwdm1 in Chinese cabbage (Brassica campestris L. ssp. pekinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1161181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladaniya, M.S. Physico-chemical, respiratory and fungicide residue changes in wax coated mandarin fruit stored at chilling temperature with intermittent warming. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 48, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Huang, K.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, R.; Liu, F.; Wen, H.; Tao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Characterization of Cuticular Wax in Tea Plant and Its Modification in Response to Low Temperature. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 13849–13861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darré, M.; Zaro, M.J.; Guijarro-Fuertes, M.; Careri, L.; Concellón, A. Melatonin Combined with Wax Treatment Enhances Tolerance to Chilling Injury in Red Bell Pepper. Metabolites 2024, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Deng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, D. Effects of Low Temperature Stress on the Seedling of Cabbage Under Different Leaf Wax Covering Degree. Qinghai Agric. For. Sci. Technol. 2022, 1, 6–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Cheng, M.; Chen, X.; Wang, A.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X. Fine Mapping and Identification of a Candidate Gene for the Glossy Green Trait in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Plants 2023, 12, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tong, C.; Zhang, X.; Song, A.; Hu, M.; Dong, W.; Chen, F.; Wang, Y.; Tu, J.; Liu, S.; et al. A high-quality Brassica napus genome reveals expansion of transposable elements, subgenome evolution and disease resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhu, H.; Huang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhong, Q. Transcriptome-wide and expression analysis of the NAC gene family in pepino (Solanum muricatum) during drought stress. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ren, Y.; Wei, W.; Yang, J.; Zhong, Q.; Li, Z. Metabolite Analysis of Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus L.) Seedlings in Response to Polyethylene Glycol-Simulated Drought Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y. Differentially Expressed Genes Identification of Kohlrabi Seedlings (Brassica oleracea var. caulorapa L.) Under Polyethylene Glycol Osmotic Stress and AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family Analysis. Plants 2024, 13, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, V.M.; Soengas, P.; Alonso-Villaverde, V.; Sotelo, T.; Cartea, M.E.; Velasco, P. Effect of temperature stress on the early vegetative development of Brassica oleracea L. BMC Plant Biol. 2015, 15, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Sun, P.; Tang, J.; Liu, D.; et al. Fine-Mapping and Analysis of Cgl1, a Gene Conferring Glossy Trait in Cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dong, X.; Ji, J.; Yang, Z.; Fang, Z.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; Sun, P.; Tang, J.; et al. Fine-mapping and transcriptome analysis of BoGL-3, a wax-less gene in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata). Mol. Genet. Genom. 2019, 294, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Dong, X.; Liu, Z.; Tang, J.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fang, Z.; et al. Fine Mapping and Candidate Gene Identification for Wax Biosynthesis Locus, BoWax1 in Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Huang, J.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Wang, Y.; et al. Genetic mapping and candidate gene identification of BoGL5, a gene essential for cuticular wax biosynthesis in broccoli. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Bai, C.; Luo, N.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Gan, Q.; Jin, S.; et al. Brassica napus BnaC9.DEWAX1 Negatively Regulates Wax Biosynthesis via Transcriptional Suppression of BnCER1-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Xiong, X.; Wu, L.; Fu, D.; Hayward, A.; Zeng, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wu, G. BraLTP1, a lipid transfer protein gene involved in epicuticular wax deposition, cell proliferation and flower development in Brassica napus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Khan, I.; Zhang, S.; Wen, J.; Ma, C.; Dai, C.; Tu, J.; et al. BnA1.CER4 and BnC1.CER4 are redundantly involved in branched primary alcohols in the cuticle wax of Brassica napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2021, 134, 3051–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Jetter, R. Composition of secondary alcohols, ketones, alkanediols, and ketols in Arabidopsis thaliana cuticular waxes. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1811–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, F.; Yang, M.; Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Wan, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, S.; Kong, L.; Chu, P.; Guan, R. BnUC1 Is a Key Regulator of Epidermal Wax Biosynthesis and Lipid Transport in Brassica napus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Su, H.; Zhao, X.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X.W.; Yuan, Y. BrWAX2 plays an essential role in cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2022, 135, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Z.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Chang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H.; Xu, R.; Zhong, F. The AP2 Transcription Factor BrSHINE3 Regulates Wax Accumulation in Nonheading Chinese Cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yue, Z.; Ding, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, J.; Zang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Tao, P. A BrLINE1-RUP insertion in BrCER2 alters cuticular wax biosynthesis in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa L. ssp. pekinensis). Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1212528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Dong, S.; Liu, C.; Zou, J.; Ren, J.; Feng, H. BrKCS6 mutation conferred a bright glossy phenotype to Chinese cabbage. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Suh, M.C. Regulatory mechanisms underlying cuticular wax biosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2799–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventure, G.; Salas, J.J.; Pollard, M.R.; Ohlrogge, J.B. Disruption of the FATB gene in Arabidopsis demonstrates an essential role of saturated fatty acids in plant growth. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1020–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, H.; Molina, I.; Shockey, J.; Browse, J. Organ fusion and defective cuticle function in a lacs1 lacs2 double mutant of Arabidopsis. Planta 2010, 231, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; He, C.; Qin, Y.; Lin, G.; Park, W.D.; Sun, M.; Li, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, C.; Yeh, C.T.; et al. Co-expression analysis aids in the identification of genes in the cuticular wax pathway in maize. Plant J. 2019, 97, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Dietrich, C.R.; Delledonne, M.; Xia, Y.; Wen, T.J.; Robertson, D.S.; Nikolau, B.J.; Schnable, P.S. Sequence analysis of the cloned glossy8 gene of maize suggests that it may code for a beta-ketoacyl reductase required for the biosynthesis of cuticular waxes. Plant Physiol. 1997, 115, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, T.S.; Millar, A.A.; Kunst, L. Significance of the expression of the CER6 condensing enzyme for cuticular wax production in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Ranathunge, K.; Huang, H.; Pei, Z.; Franke, R.; Schreiber, L.; He, C. Wax Crystal-Sparse Leaf1 encodes a beta-ketoacyl CoA synthase involved in biosynthesis of cuticular waxes on rice leaf. Planta 2008, 228, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenbach, D.; Jansen, M.; Franke, R.B.; Hensel, G.; Weissgerber, W.; Ulferts, S.; Jansen, I.; Schreiber, L.; Korzun, V.; Pontzen, R.; et al. Evolutionary conserved function of barley and Arabidopsis 3-KETOACYL-CoA SYNTHASES in providing wax signals for germination of powdery mildew fungi. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Haslam, T.M.; Krüger, A.; Schneider, L.M.; Mishina, K.; Samuels, L.; Yang, H.; Kunst, L.; Schaffrath, U.; Nawrath, C.; et al. The β-Ketoacyl-CoA Synthase HvKCS1, Encoded by Cer-zh, Plays a Key Role in Synthesis of Barley Leaf Wax and Germination of Barley Powdery Mildew. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 806–822, Correction in Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bourgault, R.; Galli, M.; Strable, J.; Chen, Z.; Feng, F.; Dong, J.; Molina, I.; Gallavotti, A. The FUSED LEAVES1-ADHERENT1 regulatory module is required for maize cuticle development and organ separation. N. Phytol. 2021, 229, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacke, E.; Korfhage, C.; Michel, D.; Maddaloni, M.; Motto, M.; Lanzini, S.; Salamini, F.; Döring, H.P. Transposon tagging of the maize Glossy2 locus with the transposable element En/Spm. Plant J. 1995, 8, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, S.; Bernard, A.; Sorel, M.; Pervent, M.; Vile, D.; Haslam, R.P.; Napier, J.A.; Lessire, R.; Domergue, F.; Joubès, J. The Arabidopsis cer26 mutant, like the cer2 mutant, is specifically affected in the very long chain fatty acid elongation process. Plant J. 2013, 73, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, T.M.; Kunst, L. Arabidopsis ECERIFERUM2-LIKEs Are Mediators of Condensing Enzyme Function. Plant Cell Physiol. 2021, 61, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Goodwin, S.M.; Boroff, V.L.; Liu, X.; Jenks, M.A. Cloning and characterization of the WAX2 gene of Arabidopsis involved in cuticle membrane and wax production. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1170–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Du, H.; Ning, J.; Ye, H.; Xiong, L. Characterization of Glossy1-homologous genes in rice involved in leaf wax accumulation and drought resistance. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009, 70, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, L.; Xiang, J.; Gao, G.; Xu, F.; Liu, A.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Y.; Chen, X.; Wan, X. OsGL1-3 is involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis and tolerance to water deficit in rice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e116676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Sun, Y.; Liu, T.; Wu, H.; An, P.; Shui, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; et al. TaCER1-1A is involved in cuticular wax alkane biosynthesis in hexaploid wheat and responds to plant abiotic stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 3077–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Ni, Y. A combination of genome-wide association study and transcriptome analysis in leaf epidermis identifies candidate genes involved in cuticular wax biosynthesis in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laila, R.; Robin, A.H.; Yang, K.; Park, J.I.; Suh, M.C.; Kim, J.; Nou, I.S. Developmental and Genotypic Variation in Leaf Wax Content and Composition, and in Expression of Wax Biosynthetic Genes in Brassica oleracea var. capitata. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, T.; Wynne Griffiths, D. The effects of stress on plant cuticular waxes. N. Phytol. 2006, 171, 469–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Tang, S.; Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Ling, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, M.; Xu, X. Chemical and Transcriptomic Analysis of Cuticle Lipids under Cold Stress in Thellungiella salsuginea. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.