Genes and Gene Functions Associated with Morphological, Productive, Reproductive, and Carcass Quality Traits in Pigs: A Functional Bioinformatics Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Gene Selection and Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Gene Frequency, Functional Enrichment (GO), and Metabolic Pathways

2.4. Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks (STRING)

2.5. Code Availability

3. Results

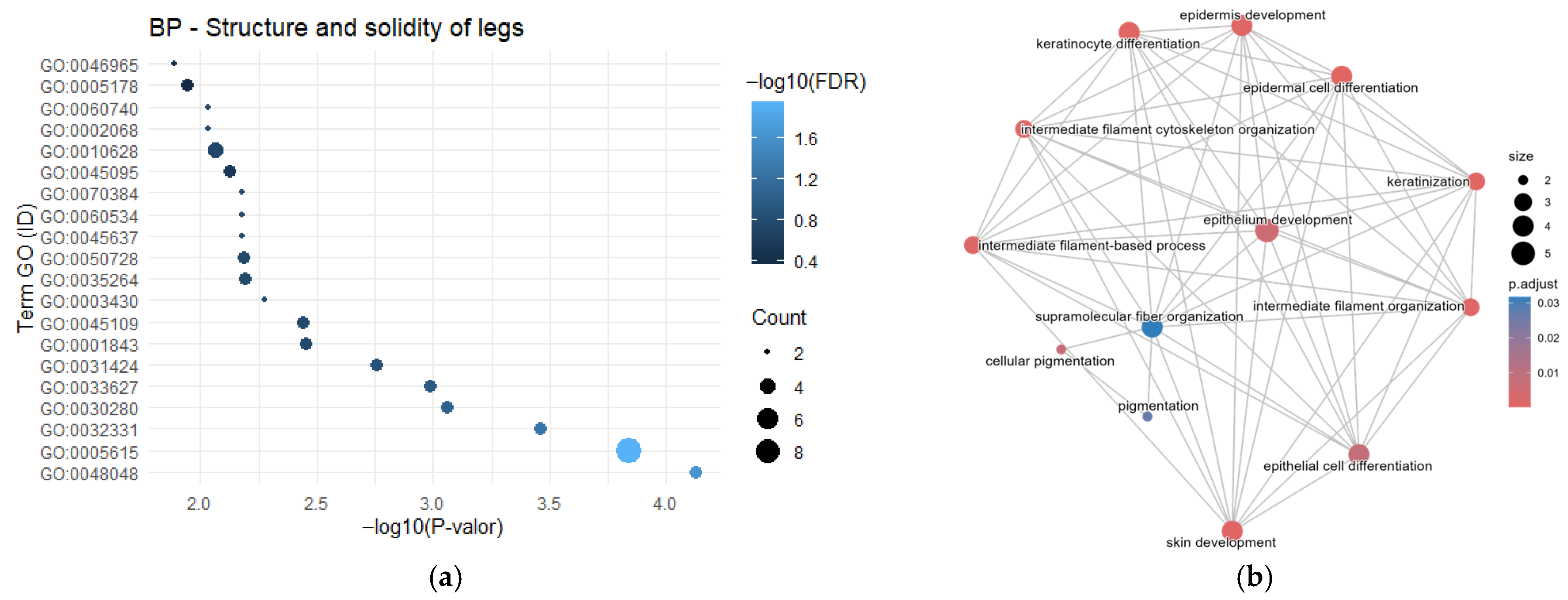

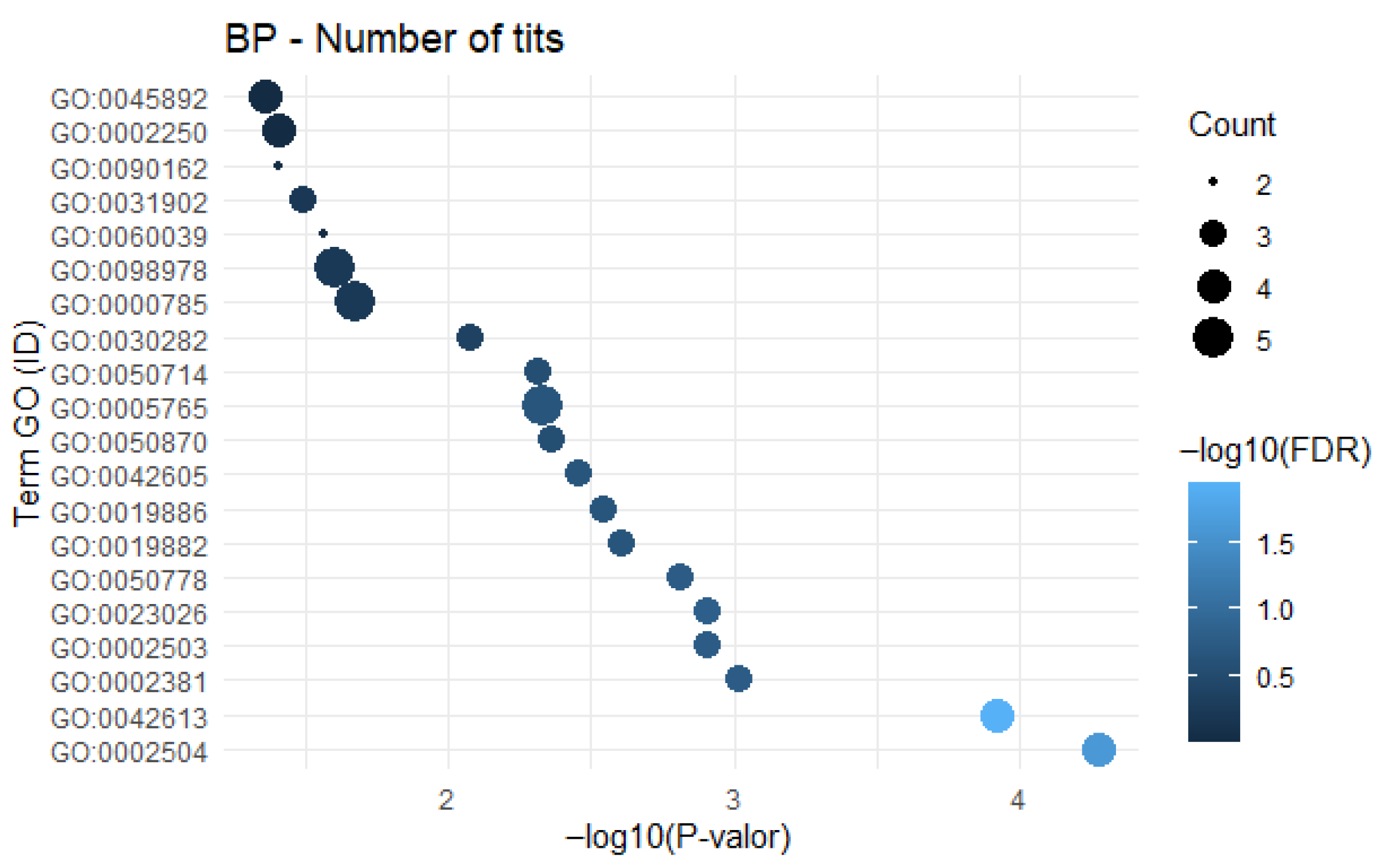

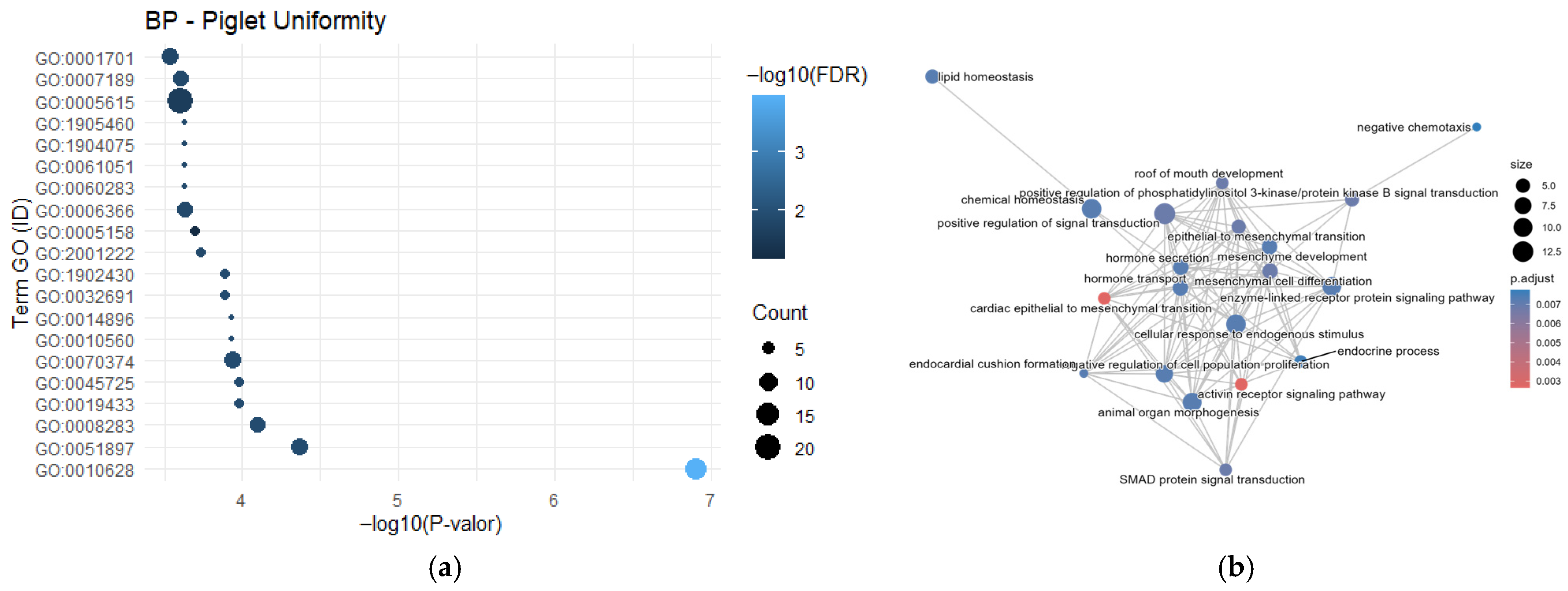

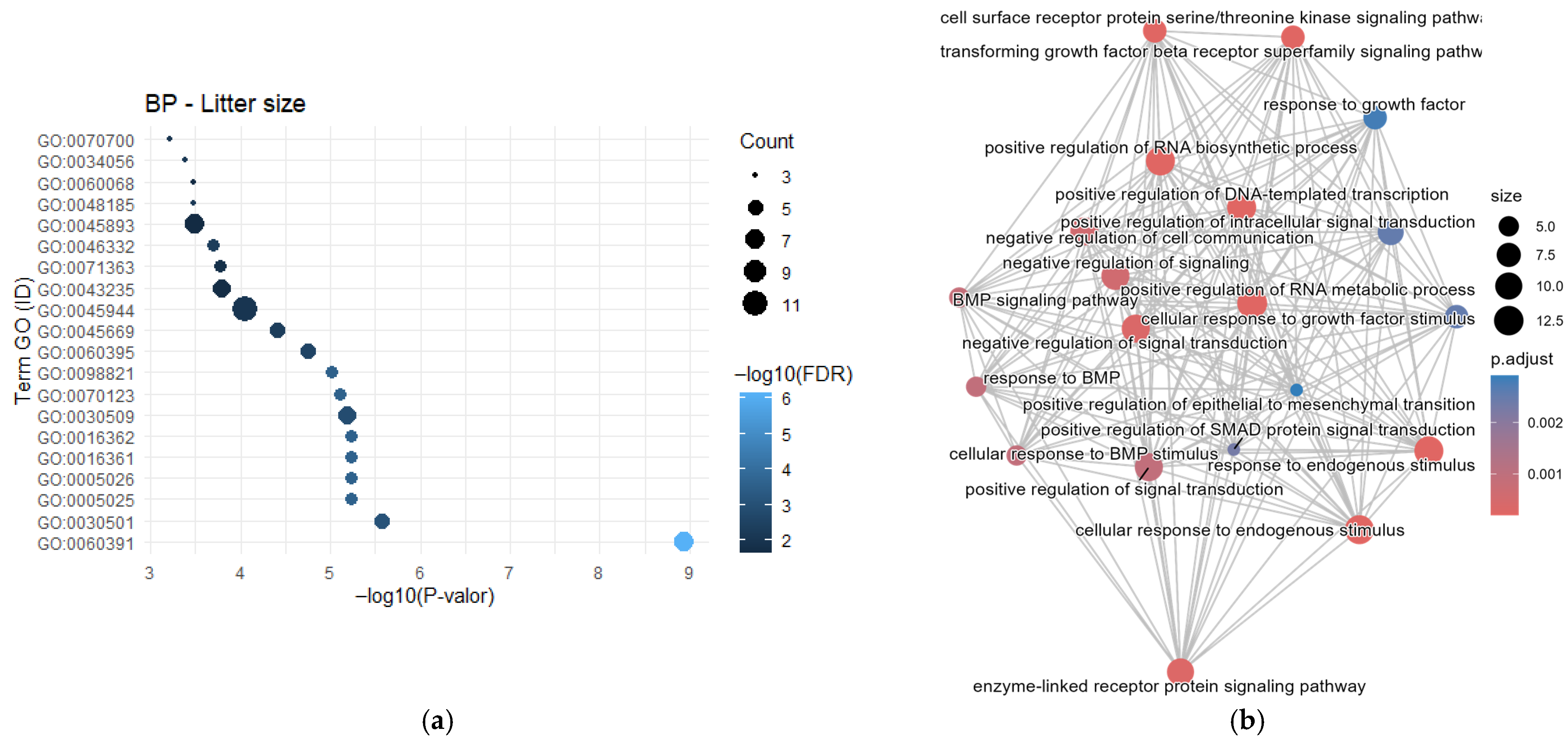

3.1. Gene Frequency, GO Enrichment Analysis, and Semantic Network

3.2. Protein–Protein Interaction Networks (STRING)

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Characteristics

4.2. Productive Performance

4.3. Reproductive

4.4. Carcass and Meat Quality

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vicente, F.; Pereira, P.C. Pork Meat Composition and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Foods 2024, 13, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J.C.M. Opportunities to Improve Environmental Sustainability of Pork Production through Genetics. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 103, skaf042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonkum, W.; Permthongchoochai, S.; Chankitisakul, V.; Duangjinda, M. Genetic Strategies for Enhancing Litter Size and Birth Weight Uniformity in Piglets. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1512701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parraguez, M. Effect of Different Culture Conditions on Gene Expression Associated with Cyst Production in Populations of Artemia Franciscana. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 768391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzib-Cauich, D.A.; Meza-villalvazo, V.M.; Osorio-Teran, A.I.; Abad-Zavaleta, J.; Cob-Calan, N.N.; Hernández-Montiel, W. Genes and Mutations in Morphological Characteristics, Productive and Reproductive Behavior, and Carcass and Meat Quality in Pig Breeds—Advances in Genetic Improvement. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst. 2025, 28, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, R.; Mahmoodi, M.; Tian, J.; Esmailizadeh Koshkoiyeh, S.; Zhao, M.; Saminzadeh, M.; Li, H.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Esmailizadeh, A. Leveraging Functional Genomics for Understanding Beef Quality Complexities and Breeding Beef Cattle for Improved Meat Quality. Genes 2024, 15, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chai, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, T.; Long, X.; Diao, S.; Chen, D.; Guo, Z.; Tang, G.; Wu, P. Enhancing Genomic Prediction Accuracy of Reproduction Traits in Rongchang Pigs Through Machine Learning. Animals 2025, 15, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triant, D.A.; Walsh, A.T.; Hartley, G.A.; Petry, B.; Stegemiller, M.R.; Nelson, B.M.; Mckendrick, M.M.; Fuller, E.P.; Cockett, N.E.; Koltes, J.E.; et al. AgAnimalGenomes: Browsers for Viewing and Manually Annotating Farm Animal Genomes. Mamm. Genome 2023, 34, 418–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Gupta, A.R.S.S.H.; Yalla, S.; Shreya; Patel, P.J.; Sharma, R.; V, A.A.; Donga, A. Integrating Marker-Assisted (MAS) and Genomic Selection (GS) for Plant Functional Trait Improvement. Plant Funct. Trait. Improv. Product. 2024, 1, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanHouten, J.; Dann, P.; McGeoch, G.; Brown, E.M.; Krapcho, K.; Neville, M.; Wysolmerski, J.J. The Calcium-Sensing Receptor Regulates Mammary Gland Parathyroid Hormone–Related Protein Production and Calcium Transport. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 113, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, J.C.M. Application of Genomics Tools to Animal Breeding. Curr. Genom. 2012, 13, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yin, H.; Cai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bai, L.; Kern, C.; Halstead, M.; Chanthavixay, G.; Trakooljul, N.; et al. Pig Genome Functional Annotation Enhances the Biological Interpretation of Complex Traits and Human Disease. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, K.M.; Bush, S.J.; Wu, C.; Su, A.I.; Muriuki, C.; Clark, E.L.; Finlayson, H.A.; Eory, L.; Waddell, L.A.; Talbot, R.; et al. Functional Annotation of the Transcriptome of the Pig, Sus Scrofa, Based Upon Network Analysis of an RNAseq Transcriptional Atlas. Front. Genet. 2020, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Katsevich, E.; Sabatti, C. Exploratory Gene Ontology Analysis with Interactive Visualization. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, T.; Peng, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, B.; Sun, J. Reconstruction and Application of Protein–Protein Interaction Network. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobrido Prieto, M.; Rumbo-Prieto, J.M. The Systematic Review: Plurality of Approaches and Methodologies. Enfermería Clínica 2018, 28, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A Universal Enrichment Tool for Interpreting Omics Data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Li, F.; Qin, Y.; Bo, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S. GOSemSim: An R Package for Measuring Semantic Similarity among GO Terms and Gene Products. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 976–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING Database in 2023: Protein-Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkilä, M.T.; Stalder, K.J.; Mote, B.E.; Rothschild, M.F.; Gunsett, F.C.; Johnson, A.K.; Karriker, L.A.; Boggess, M.V.; Serenius, T.V. Genetic Associations for Gilt Growth, Compositional, and Structural Soundness Traits with Sow Longevity and Lifetime Reproductive Performance. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 91, 1570–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivieri, J.; Smaldone, S.; Ramirez, F. Fibrillin Assemblies: Extracellular Determinants of Tissue Formation and Fibrosis. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair 2010, 3, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y. The Extracellular Matrix Glycoprotein Fibrillin-1 in Health and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1302285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga-Gil, W.; Lizcano-González, K.; Ramírez-Cheyne, J.A. Osteogénesis Imperfecta Tipo IV Originada En Una Rara Variante de Cambio de Sentido En COL1A2. CES Med. 2019, 33, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Gao, P.; Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, J. A Functional Mutation at Position -155 in Porcine APOE Promoter Affects Gene Expression. BMC Genet. 2011, 12, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; An, E.K.; Hwang, J.; Jin, J.O.; Lee, P.C.W. Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme Uba6 Regulates Th1 and Tc1 Cell Differentiation. Cells 2022, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, B.; Onteru, S.K.; Mote, B.E.; Serenius, T.; Stalder, K.J.; Rothschild, M.F. Large-Scale Association Study for Structural Soundness and Leg Locomotion Traits in the Pig. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2009, 41, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, H.; Werner, D.N.; Baulain, U.; Brade, W.; Weissmann, F. Genotype-Environment Interactions for Growth and Carcass Traits in Different Pig Breeds Kept under Conventional and Organic Production Systems. Animal 2010, 4, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; He, J.N.; Yu, W.M.; Liu, K.D.; Cheng, M.; Liu, J.F.; He, Y.H.; Zhao, J.S.; Qu, X.X. Transcriptome Analysis of Skeletal Muscle at Prenatal Stages in Polled Dorset versus Small-Tailed Han Sheep. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.C.; Rudolph-Stringer, V.; Straszkowski, L.; Tjin, G.; Crimeen-Irwin, B.; Walia, M.; Martin, T.J.; Sims, N.A.; Purton, L.E. Retinoic Acid Receptor γ Activity in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regulates Endochondral Bone, Angiogenesis, and B Lymphopoiesis. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2018, 33, 2202–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Wei, S.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Gui, L.; Xiang, H.; Ma, Y.; Dan, X. A Novel Mechanism of Kisspeptin Regulating Ovarian Granulosa Cell Function via Down-Regulating Let-7b to Activate ERK/PI3K-Akt Pathway in Tan Sheep. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2025, 92, 106947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smaldone, S.; Ramirez, F. Fibrillin Microfibrils in Bone Physiology. Matrix Biol. 2015, 52–54, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asano, K.; Cantalupo, A.; Sedes, L.; Ramirez, F. The Multiple Functions of Fibrillin-1 Microfibrils in Organismal Physiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, L.Y.; Keene, D.R.; Renard, M.; De Backer, J. FBN1: The Disease-Causing Gene for Marfan Syndrome and Other Genetic Disorders. Gene 2016, 591, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törmä, H. Regulation of Keratin Expression by Retinoids. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011, 3, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C.A.; Shen, J.; Lu, A.; James, A.W. WNT16 Induces Proliferation and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Perivascular Stem Cells. J. Orthop. 2018, 15, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Fang, W.; Yuan, M.; Sun, H.; Wang, J. Transcriptome Analysis of Leg Muscles and the Effects of ALOX5 on Proliferation and Differentiation of Myoblasts in Haiyang Yellow Chickens. Genes 2023, 14, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mex, J.E.E.; Correa, J.C.S.; García, L.B.; López, A.A. Factores Ambientales Que Afectan Los Componentes de Producción y Productividad Durante La Vida de Las Cerdas. Trop. Subtrop. Agroecosyst 2014, 17, 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Alberto García-Munguía, C.; Ruíz-Flores, A.; López-Ordaz, R.; Margarito García-Munguía, A.; Arturo Ibarra-Juárez, L. Productive and Reproductive Performance at Farrowing and at Weaning of Sows of Seven Genetic Lines. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2014, 5, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; He, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Hao, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, X. Synergistic Effects of Overexpression of BMP-2 and TGF-Β3 on Osteogenic Differentiation of Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2016, 14, 5514–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, J.; Peng, S.; Zhong, L.; Zhou, L.; Yan, G.; Xiao, S.; Ma, J.; Huang, L. Identification and Validation of a Regulatory Mutation Upstream of the BMP2 Gene Associated with Carcass Length in Pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2021, 53, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Ye, J.; Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, L.; Cai, G.; Liu, D.; Tan, C.; Wu, Z. Genome-Wide Association Study for Body Length, Body Height, and Total Teat Number in Large White Pigs. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 650370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhuang, Z.; Yang, M.; Ding, R.; Quan, J.; Zhou, S.; Gu, T.; Xu, Z.; Zheng, E.; Cai, G.; et al. Genome-Wide Detection of Genetic Loci and Candidate Genes for Body Conformation Traits in Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire Crossbred Pigs. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 664343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackowska, M.; Kempisty, B.; Woźna, M.; Piotrowska, H.; Antosik, P.; Zawierucha, P.; Bukowska, D.; Nowicki, M.; Jaśkowski, J.; Brüssow, K.-P. Differential Expression of GDF9, TGFB1, TGFB2 and TGFB3 in Porcine Oocytes Isolated from Follicles of Different Size before and after Culture in Vitro. Acta Vet. Hung. 2013, 61, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lü, A.; Hu, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Pang, Y. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms of the Prolactin Receptor (PRLR) Gene and Its Association with Growth Traits in Chinese Cattle. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lü, A.; Hu, X.; Chen, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Novel SNPs of the Bovine PRLR Gene Associated with Milk Production Traits. Biochem. Genet. 2011, 49, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempfli, K.; Farkas, G.; Simon, Z.; Bali Papp, Á. Effects of Prolactin Receptor Genotype on the Litter Size of Mangalica. Acta Vet. Hung. 2011, 59, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.Z.; Xia, J.H.; Xin, L.L.; Wang, Z.G.; Qian, L.; Wu, S.G.; Yang, S.L.; Li, K. Swine Leukocyte Antigen Class II Genes (SLA-DRA, SLA-DRB1, SLA-DQA, SLA-DQB1) Polymorphism and Genotyping in Guizhou Minipigs. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 15256–15266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, T.K.; Chatterjee, R.N.; Dushyanth, K.; Paswan, C.; Shukla, R.; Shanmugam, M. Polymorphism and Expression of Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1) Gene and Its Association with Growth Traits in Chicken. Br. Poult. Sci. 2015, 56, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadag, O. The Polymorphism of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 Receptor (IGF-1R) Gene in Meat-Type Lambs in Turkey: I. Effect on Growth Traits and Body Measurements. Small Rumin. Res. 2022, 215, 106765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, Z.; Ren, G.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D. Expression Patterns of Insulin-like Growth Factor System Members and Their Correlations with Growth and Carcass Traits in Landrace and Lantang Pigs during Postnatal Development. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013, 40, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierzchała, M.; Pareek, C.S.; Urbański, P.; Goluch, D.; Kamyczek, M.; Różycki, M.; Smoczynski, R.; Horbańczuk, J.O.; Kurył, J. Study of the Differential Transcription in Liver of Growth Hormone Receptor (GHR), Insulin-like Growth Factors (IGF1, IGF2) and Insulin-like Growth Factor Receptor (IGF1R) Genes at Different Postnatal Developmental Ages in Pig Breeds. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 3055–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welle, S.L. Myostatin and Muscle Fiber Size. Focus on “Smad2 and 3 Transcription Factors Control Muscle Mass in Adulthood” and “Myostatin Reduces Akt/TORC1/P70S6K Signaling, Inhibiting Myoblast Differentiation and Myotube Size”. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2009, 296, C1245–C1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Tan, Z.; Xing, K.; Yang, T.; Pan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Mi, S.; Sun, D.; Wang, C. Genome-Wide Association Study for Reproductive Traits in a Large White Pig Population. Anim. Genet. 2018, 49, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonneman, D.J.; Lents, C.A. Functional Genomics of Reproduction in Pigs: Are We There Yet? Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2023, 90, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, O.E.; Wader, K.F.; Hella, H.; Mylin, A.K.; Turesson, I.; Nesthus, I.; Waage, A.; Sundan, A.; Holien, T. Activin A Inhibits BMP-Signaling by Binding ACVR2A and ACVR2B. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, T.; Tsukamoto, S.; Kuratani, M. Accumulated Knowledge of Activin Receptor-Like Kinase 2 (ALK2)/Activin A Receptor, Type 1 (ACVR1) as a Target for Human Disorders. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ye, J.; Han, X.; Qiao, R.; Li, X.; Lv, G.; Wang, K. Whole-Genome Sequencing Identifies Potential Candidate Genes for Reproductive Traits in Pigs. Genomics 2020, 112, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; He, N.; Sun, R.; Deng, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, J. Expression and Polymorphisms of SMAD1, SMAD2 and SMAD3 Genes and Their Association with Litter Size in Tibetan Sheep (Ovis Aries). Genes 2022, 13, 2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Cao, G.; Chen, W.; Wang, C.; Khan, M.Z. The Role of TGF-β Signaling Pathway in Determining Small Ruminant Litter Size. Biology 2025, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, P.; Li, Z.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Sun, H.; Mei, S.; Li, F. Genetic Effect and Combined Genotype Effect of ESR, FSH β, CTNNAL1 and MiR-27a Loci on Litter Size in a Large White Population. Anim. Biotechnol. 2019, 30, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, G.; Ovilo, C.; Estellé, J.; Silió, L.; Fernández, A.; Rodriguez, C. Association with Litter Size of New Polymorphisms on ESR1 and ESR2 Genes in a Chinese-European Pig Line. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2007, 39, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cao, X. BMP Signaling and Skeletogenesis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1068, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lai, J.; Wang, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, C.; Chen, Q.; Lu, S. Genome-Wide Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) Data Reveal Potential Candidate Genes for Litter Traits in a Yorkshire Pig Population. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2023, 66, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirokawa, N.; Noda, Y. Intracellular Transport and Kinesin Superfamily Proteins, KIFs: Structure, Function, and Dynamics. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 1089–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicki, M.A.; Jaenisch, R. The MyoD Family of Transcription Factors and Skeletal Myogenesis. BioEssays 1995, 17, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Cao, H.; Mao, H.; Hong, Q.; Yin, Z. Association of MyoD1 Gene Polymorphisms with Meat Quality Traits in Domestic Pigeons (Columba Livia). J. Poult. Sci. 2019, 56, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, H.A.; Allouh, M.Z.; Said, R.S. Myogenic Regulatory Factors: The Orchestrators of Myogenesis after 30 Years of Discovery. Exp. Biol. Med. 2018, 243, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.A.; Kim, J.M.; Lim, K.S.; Ryu, Y.C.; Jeon, W.M.; Hong, K.C. Effects of Variation in Porcine MYOD1 Gene on Muscle Fiber Characteristics, Lean Meat Production, and Meat Quality Traits. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Kim, N.H.; Cui, X.S. Inhibition of Fatty Acid Synthase Reduces Blastocyst Hatching through Regulation of the AKT Pathway in Pigs. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dzib-Cauich, L.-F.; Bugarín-Prado, J.; Ayala-Valdovinos, M.; Moo-Huchin, V. Perfil de Ácidos Grasos en Músculo Longissimus Dorsi y Expresión de Genes Asociados con Metabolismo Lipídico en Cerdos Pelón Mexicanos y Cerdos Landrace-Yorkshire. Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2020, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ros-Freixedes, R.; Gol, S.; Pena, R.N.; Tor, M.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N.; Dekkers, J.C.M.; Estany, J. Genome-Wide Association Study Singles Out SCD and LEPR as the Two Main Loci Influencing Intramuscular Fat Content and Fatty Acid Composition in Duroc Pigs. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estany, J.; Ros-Freixedes, R.; Tor, M.; Pena, R.N. A Functional Variant in the Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase Gene Promoter Enhances Fatty Acid Desaturation in Pork. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Liang, X.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Tao, C.; Zhang, J.; Tian, J.; Zhao, J.; et al. Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase Is Essential for Porcine Adipocyte Differentiation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uemoto, Y.; Kikuchi, T.; Nakano, H.; Sato, S.; Shibata, T.; Kadowaki, H.; Katoh, K.; Kobayashi, E.; Suzuki, K. Effects of Porcine Leptin Receptor Gene Polymorphisms on Backfat Thickness, Fat Area Ratios by Image Analysis, and Serum Leptin Concentrations in a Duroc Purebred Population. Anim. Sci. J. 2012, 83, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Naseem, S.; Park, S.; Hur, S.; Choi, Y.; Lee, T.; Li, X.; Choi, S. FASN, SCD, and PLAG1 Gene Polymorphism and Association with Carcass Traits and Fatty Acid Profile in Hanwoo Cattle. Animals 2025, 15, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.R.; Ha, J.; Kwon, S.G.; Hwang, J.H.; Park, D.H.; Kim, T.W.; Lee, H.K.; Song, K.D.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, C.W. Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in Pig EPHX1 Gene Are Associated with Pork Quality Traits. Anim. Biotechnol. 2015, 26, 237–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ropka-Molik, K.; Podstawski, P.; Piórkowska, K.; Tyra, M. Association of Missense MTTP Gene Polymorphism with Carcass Characteristics and Meat Quality Traits in Pigs. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 62, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piórkowska, K.; Małopolska, M.; Ropka-Molik, K.; Szyndler-Nędza, M.; Wiechniak, A.; Żukowski, K.; Lambert, B.; Tyra, M. Evaluation of SCD, ACACA and FASN Mutations: Effects on Pork Quality and Other Production Traits in Pigs Selected Based on RNA-Seq Results. Animals 2020, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Z.; Ruan, D.; Wu, J.; Quan, J.; Zheng, E.; Yang, J.; Cai, G.; Wu, Z.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study for Somatic Skeletal Traits in Duroc × (Landrace × Yorkshire) Pigs. Animals 2024, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Yang, L.; Deng, Q.; Wei, T.; Zhao, H.; Peng, P.; Lin, X.; Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identifies Genomic Regions and Candidate Genes for Growth and Fatness Traits in Diannan Small-Ear (DSE) Pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Deng, Q.; Qi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, S.; Li, Y.; Tan, H.; Wu, M.; Yin, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Identified Variants Associated with Body Measurement and Reproduction Traits in Shaziling Pigs. Genes 2023, 14, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.H.; Christensen, O.F.; Nielsen, B.; Sahana, G. Genome-Wide Association Study for Conformation Traits in Three Danish Pig Breeds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2017, 49, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Onteru, S.K.; Nikkilä, M.T.; Stalder, K.J.; Rothschild, M.F. Identification of Genetic Markers Associated with Fatness and Leg Weakness Traits in the Pig. Anim. Genet. 2009, 40, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, X.; Plastow, G.; Zhang, C.; Xu, S.; Hu, Z.; Yang, T.; Wang, K.; Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Liu, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Candidate Genes for Piglet Splay Leg Syndrome in Different Populations. BMC Genet. 2017, 18, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, T.; Reyer, H.; Maak, S.; Röntgen, M. Homer 1 Genotype AA Variant Relates to Congenital Splay Leg Syndrome in Piglets by Repressing Pax7 in Myogenic Progenitors. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1028879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.; Hao, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, L.; Hu, L.; Zhang, S. Polymorphisms of HOMER1 Gene Are Associated with Piglet Splay Leg Syndrome and One Significant SNP Can Affect Its Intronic Promoter Activity in Vitro. BMC Genet. 2018, 19, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Wang, S.; Qin, H.; Zeng, H.; Ye, J.; Yang, J.; Cai, G.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z. Genome-Wide Association Analysis Unveils Candidate Genes and Loci Associated with Aplasia Cutis Congenita in Pigs. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijvesteijn, N.; Veltmaat, J.M.; Knol, E.F.; Harlizius, B. High-Resolution Association Mapping of Number of Teats in Pigs Reveals Regions Controlling Vertebral Development. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; Bastiaansen, J.W.M.; Harlizius, B.; Knol, E.F.; Bovenhuis, H. A Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals Dominance Effects on Number of Teats in Pigs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrer, G.A.; Nonneman, D.J. Genetic Analysis of Teat Number in Pigs Reveals Some Developmental Pathways Independent of Vertebra Number and Several Loci Which Only Affect a Specific Side. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2017, 49, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Sun, J.; Pan, Y.; Cao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, T.; Guo, A.; Han, R.; Ding, X.; Yang, G.; et al. Revealing Genes Related Teat Number Traits via Genetic Variation in Yorkshire Pigs Based on Whole-Genome Sequencing. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Gao, H.; Hou, X.; Zhao, F.; Yan, H.; et al. Identification of SNPs and Candidate Genes for Milk Production Ability in Yorkshire Pigs. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 724533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, C.; Prakapenka, D.; Tan, C.; Yang, R.; Zhu, D.; Guo, X.; Liu, D.; Cai, G.; Li, Y.; Liang, Z.; et al. Haplotype Genomic Prediction of Phenotypic Values Based on Chromosome Distance and Gene Boundaries Using Low-Coverage Sequencing in Duroc Pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2021, 53, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Lee, J.B.; Kang, K.; Yoo, C.K.; Kim, B.M.; Park, H.B.; Lim, H.T.; Cho, I.C.; Maharani, D.; Lee, J.H. The Possibility of TBC1D21 as a Candidate Gene for Teat Numbers in Pigs. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Wu, Z.; Ren, J.; Huang, Z.; Liu, D.; He, X.; Prakapenka, D.; Zhang, R.; Li, N.; Da, Y.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study and Accuracy of Genomic Prediction for Teat Number in Duroc Pigs Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2017, 49, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Zhong, Z.; Jiang, S. A Whole Genome Sequencing-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Reveals the Potential Associations of Teat Number in Qingping Pigs. Animals 2022, 12, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzaman, M.R.; Park, J.E.; Lee, K.T.; Cho, E.S.; Choi, B.H.; Kim, T.H. Whole-Genome Association and Genome Partitioning Revealed Variants and Explained Heritability for Total Number of Teats in a Yorkshire Pig Population. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 31, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verardo, L.L.; Silva, F.F.; Lopes, M.S.; Madsen, O.; Bastiaansen, J.W.M.; Knol, E.F.; Kelly, M.; Varona, L.; Lopes, P.S.; Guimarães, S.E.F. Revealing New Candidate Genes for Reproductive Traits in Pigs: Combining Bayesian GWAS and Functional Pathways. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2016, 48, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Ding, R.; Peng, L.; Wu, J.; Ye, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, X.; Quan, J.; Zheng, E.; Cai, G.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Analyses Identify Known and Novel Loci for Teat Number in Duroc Pigs Using Single-Locus and Multi-Locus Models. BMC Genom. 2020, 21, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Teng, J.; Diao, S.; Xu, Z.; Ye, S.; Qiu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Insights into the Architecture of Human-Induced Polygenic Selection in Duroc Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, L.; Yang, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, L.; Fang, S.; Deng, W.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Z.; Ai, H.; et al. Possible Introgression of the VRTN Mutation Increasing Vertebral Number, Carcass Length and Teat Number from Chinese Pigs into European Pigs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.T.; Thi, V.N.; Duy, P.P.; Duc, L.D.; Kim, D.P.; Phuong, G.N.T.; Minh, T.N.N.; Hoang, T.N. Polymorphism of Candidate Genes Related to the Number of Teat, Vertebrae and Ribs in Pigs. Adv. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2020, 8, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pu, L.; Shi, L.; Gao, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, L.; Zhao, F. Revealing New Candidate Genes for Teat Number Relevant Traits in Duroc Pigs Using Genome-Wide Association Studies. Animals 2021, 11, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, X.; Deng, S.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Cai, G.; Yang, J.; Wu, Z.; et al. Genome-Wide Detection of Multiple Variants Associated with Teat Number in French Yorkshire Pigs. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Giner, M.; Noguera, J.L.; Balcells, I.; Alves, E.; Varona, L.; Pena, R.N. Expression Study on the Porcine PTHLH Gene and Its Relationship with Sow Teat Number. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2011, 128, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosková, A.; Mehrotra, A.; Kadri, N.K.; Lloret-Villas, A.; Neuenschwander, S.; Hofer, A.; Pausch, H. Comparison of Two Multi-Trait Association Testing Methods and Sequence-Based Fine Mapping of Six Additive QTL in Swiss Large White Pigs. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Do, K.T.; Park, K.D.; Lee, H.K. Genome-Wide Association Study Using a Single-Step Approach for Teat Number in Duroc, Landrace and Yorkshire Pigs in Korea. Anim. Genet. 2023, 54, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetzlaff, S.; Chomdej, S.; Jonas, E.; Ponsuksili, S.; Murani, E.; Phatsara, C.; Schellander, K.; Wimmers, K. Association of Parathyroid Hormone-like Hormone (PTHLH) and Its Receptor (PTHR1) with the Number of Functional and Inverted Teats in Pigs. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2009, 126, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Son, M.; Lopes, M.S.; Martell, H.J.; Derks, M.F.L.; Gangsei, L.E.; Kongsro, J.; Wass, M.N.; Grindflek, E.H.; Harlizius, B. A QTL for Number of Teats Shows Breed Specific Effects on Number of Vertebrae in Pigs: Bridging the Gap between Molecular and Quantitative Genetics. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.X.; Wei, N.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.Q.; Yang, G.S.; Pang, W.J. Association of Novel Polymorphisms in Lymphoid Enhancer Binding Factor 1 (LEF-1) Gene with Number of Teats in Different Breeds of Pig. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2014, 27, 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, R.; Guo, X.; Zhu, D.; Tan, C.; Bian, C.; Ren, J.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, G.; Liu, D.; et al. Accelerated Deciphering of the Genetic Architecture of Agricultural Economic Traits in Pigs Using a Low-Coverage Whole-Genome Sequencing Strategy. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Li, X.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, C.; Ruan, D.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, E.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies the Crucial Candidate Genes for Teat Number in Crossbred Commercial Pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Tan, Z.; Ning, C.; Xing, K.; Yang, T.; Pan, Y.; Sun, D.; Wang, C. Genome-Wide Association Study of Piglet Uniformity and Farrowing Interval. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakoev, S.; Getmantseva, L.; Kolosova, M.; Bakoev, F.; Kolosov, A.; Romanets, E.; Shevtsova, V.; Romanets, T.; Kolosov, Y.; Usatov, A. Identifying Significant SNPs of the Total Number of Piglets Born and Their Relationship with Leg Bumps in Pigs. Biology 2024, 13, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumchoo, T.; Mekchay, S. Association of NR4A1 and GNB2L1 Genes with Reproductive Traits in Commercial Pig Breeds. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015, 14, 16276–16284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cao, M.; Wei, J.; Yu, T.; Ding, X.; Yang, G. Genome-Wide Association Study on Reproductive Traits Using Imputation-Based Whole-Genome Sequence Data in Yorkshire Pigs. Genes 2023, 14, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, X.; Michal, J.J.; Ding, B.; Li, R.; Jiang, Z. Genome Wide Screening of Candidate Genes for Improving Piglet Birth Weight Using High and Low Estimated Breeding Value Populations. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2014, 10, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Ye, S.; He, Y.; Huang, S.; Yuan, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, J. Genome-wide Association Study for Reproductive Traits in a Duroc Pig Population. Animals 2019, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.X.; Gao, G.X.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, C.X.; Li, B.; El-Ashram, S.; Li, Z.L. Genome-Wide Association Studies Uncover Genes Associated with Litter Traits in the Pig. Animal 2022, 16, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stange, K.; Miersch, C.; Sponder, G.; Röntgen, M. Low Birth Weight Influences the Postnatal Abundance and Characteristics of Satellite Cell Subpopulations in Pigs. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell-Kubiak, E.; Knol, E.F.; Lopes, M. Evaluation of the Phenotypic and Genomic Background of Variability Based on Litter Size of Large White Pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2022, 54, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Deng, D.; Yu, M.; Li, X. Genetic Determinants of Pig Birth Weight Variability. BMC Genet. 2016, 17, S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhuang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, X.; Ruan, D.; Xu, C.; Zheng, E.; Yang, M.; Cai, G.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Study of Body Conformation Traits in a Three-Way Crossbred Commercial Pig Population. Animals 2023, 13, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, S.M.; Lim, B.; Park, J.; Song, K.L.; Jeon, J.H.; Na, C.S.; Kim, J.M. Estimation of Variance Components and Genomic Prediction for Individual Birth Weight Using Three Different Genome-Wide Snp Platforms in Yorkshire Pigs. Animals 2020, 10, 2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ding, R.; Zhuang, Z.; Wu, J.; Yang, M.; Zhou, S.; Ye, Y.; Geng, Q.; Xu, Z.; Huang, S.; et al. Genome-Wide Detection of CNV Regions and Their Potential Association with Growth and Fatness Traits in Duroc Pigs. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-X.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, D.-J.; Yang, X.-D.; Liu, Y.-H.; Jiang, A.-A.; Shen, L.-Y.; Jin, L.; Xiao, W.-H.; et al. Identifying SNPs Associated with Birth Weight and Days to 100 Kg Traits in Yorkshire Pigs Based on Genotyping-by-Sequencing. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korwin-kossakowska, A.; Sender, G.; Kurył, J. Associations between the Microsatellite DnA Sequence in the IGF1 Gene, Polymorphism in the ESR Gene and Selected Reproduction Traits in F1 (Zlotnicka Spotted × Polish Large White) Sows. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2004, 22, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, F.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; Hua, J.; Fu, J. Association of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms of MDR1 and OPN Genes with Reproductive Traits in Different Breeds of Sows. Pak. J. Zool. 2021, 53, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, W.; Song, Q.-Q.; Li, H.-H.; Xu, M.-S.; Liu, G.-L.; Zhang, J.-Z. Association Analysis of Polymorphisms of G Protein-Coupled Receptor 54 Gene Exons with Reproductive Traits in Jiaxing Black Sows. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 32, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Peng, Y.; Zuo, B.; Xu, Z. Effects of KPNA7 Gene Polymorphisms on Reproductive Traits in France Large White Pigs. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2021, 49, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieleń, G.; Derks, M.F.L.; Knol, E.F.; Sell-Kubiak, E. The Impact of Box-Cox Transformation on Phenotypic and Genomic Characteristics of Litter Size Variability in Landrace Pigs. Animal 2023, 17, 100784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.H.; An, S.M.; Yu, G.E.; Park, D.H.; Kang, D.G.; Kim, T.W.; Park, H.C.; Ha, J.; Kim, C.W. Association of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in NAT9 and MAP3K3 Genes with Litter Size Traits in Berkshire Pigs. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2018, 61, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norseeda, W.; Liu, G.; Teltathum, T.; Supakankul, P.; Sringarm, K.; Naraballobh, W.; Khamlor, T.; Chomdej, S.; Nganvongpanit, K.; Krutmuang, P.; et al. Association of IL-4 and IL-4R Polymorphisms with Litter Size Traits in Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Mei, S.; Tao, H.; Wang, G.; Su, L.; Jiang, S.; Deng, C.; Xiong, Y.; Li, F. Microarray Profiling for Differential Gene Expression in PMSG-HCG Stimulated Preovulatory Ovarian Follicles of Chinese Taihu and Large White Sows. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Xiang, J.; Zhang, Y. Association Analysis of METTL23 Gene Polymorphisms with Reproductive Traits in Kele Pigs. Genes 2024, 15, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wang, K.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Q.; Yang, X.; Jiang, A.; Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhu, L.; Bai, L.; et al. A Genome Wide Association Study for the Number of Animals Born Dead in Domestic Pigs. BMC Genet. 2019, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, K.; Jiang, C.; Ren, D.; Xu, P.; He, X.; Liao, R.; Jiang, K.; Ma, J.; et al. Production of Transgenic Pigs with an Introduced Missense Mutation of the Bone Morphogenetic Protein Receptor Type IB Gene Related to Prolificacy. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Wu, K. A Unique 15-Bp InDel in the First Intron of BMPR1B Regulates Its Expression in Taihu Pigs. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mũoz, M.; Fernández, A.I.; Óvilo, C.; Mũoz, G.; Rodriguez, C.; Fernández, A.; Alves, E.; Silió, L. Non-Additive Effects of RBP4, ESR1 and IGF2 Polymorphisms on Litter Size at Different Parities in a Chinese-European Porcine Line. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2010, 42, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Li, F.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, X. Characterization and Association Analysis with Litter Size Traits of Porcine Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Gene (PMMP-9). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 171, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Kong, M.; Ning, C.; Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X. Cybrid Model Supports Mitochondrial Genetic Effect on Pig Litter Size. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 579382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; MacNeil, M.D.; Kemp, R.A.; Dyck, M.K.; Plastow, G.S. Putative Loci Causing Early Embryonic Mortality in Duroc Swine. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozalo-Marcilla, M.; Buntjer, J.; Johnsson, M.; Batista, L.; Diez, F.; Werner, C.R.; Chen, C.Y.; Gorjanc, G.; Mellanby, R.J.; Hickey, J.M.; et al. Genetic Architecture and Major Genes for Backfat Thickness in Pig Lines of Diverse Genetic Backgrounds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2021, 53, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Kwon, S.; Hwang, J.H.; Park, D.H.; Kim, T.W.; Kang, D.G.; Yu, G.E.; Park, H.C.; An, S.M.; Kim, C.W. Squalene Epoxidase Plays a Critical Role in Determining Pig Meat Quality by Regulating Adipogenesis, Myogenesis, and ROS Scavengers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, J.L.; Hwang, J.H.; Kwon, S.G.; Park, D.H.; Kim, T.W.; Kang, D.G.; Yu, G.E.; Kim, I.S.; Ha, J.G.; Kim, C.W. Association between a Non-Synonymous HSD17B4 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism and Meat-Quality Traits in Berkshire Pigs. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma-Granados, P.; Muñoz, M.; Delgado-Gutierrez, M.A.; Óvilo, C.; Nuñez, Y.; Fernández-Barroso, M.A.; Sánchez-Esquiliche, F.; Ramírez, L.; García-Casco, J.M. Candidate SNPs for Meat Quality and Carcass Composition in Free-Range Iberian Pigs. Meat Sci. 2024, 207, 109373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Thakali, K.; Morse, P.; Shelby, S.; Chen, J.; Apple, J.; Huang, Y. Comparison of Growth Performance and Meat Quality Traits of Commercial Cross-Bred Pigs versus the Large Black Pig Breed. Animals 2021, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Qin, J.; Yao, T.; Tang, X.; Cui, D.; Chen, L.; Rao, L.; Xiao, S.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, L. Genetic Dissection of 26 Meat Cut, Meat Quality and Carcass Traits in Four Pig Populations. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, W.; Wang, J.; Zhao, R.; Niu, N.; Su, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liu, X.; Hou, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; et al. Associations of Genome-Wide Structural Variations with Phenotypic Differences in Cross-Bred Eurasian Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, Z.; Wang, F.; Deng, C.Y.; Wei, L.M.; Sun, R.P.; Liu, H.L.; Liu, Q.W.; Zheng, X.L. Distribution and Linkage Disequilibrium Analysis of Polymorphisms of MC4R, LEP, H-FABP Genes in the Different Populations of Pigs, Associated with Economic Traits in DIV2 Line. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 6329–6335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.I.; Pérez-Montarelo, D.; Barragán, C.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Ibáñez-Escriche, N.; Castelló, A.; Noguera, J.L.; Silió, L.; Folch, J.M.; Rodríguez, M.C. Genome-Wide Linkage Analysis of QTL for Growth and Body Composition Employing the PorcineSNP60 BeadChip. BMC Genet. 2012, 13, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xue, M.; Wu, M.; Tan, H.; Peng, Y.; Wang, K.; Fang, M. Integrated Analysis Strategy of Genome-Wide Functional Gene Mining Reveals DKK2 Gene Underlying Meat Quality in Shaziling Synthesized Pigs. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Peng, J.; Xu, D.Q.; Zheng, R.; Li, F.E.; Li, J.L.; Zuo, B.; Lei, M.G.; Xiong, Y.Z.; Deng, C.Y.; et al. Association of MYF5 and MYOD1 Gene Polymorphisms and Meat Quality Traits in Large White x Meishan F2 Pig Populations. Biochem. Genet. 2008, 46, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Óvilo, C.; Trakooljul, N.; Núñez, Y.; Hadlich, F.; Murani, E.; Ayuso, M.; García-Contreras, C.; Vázquez-Gómez, M.; Rey, A.I.; Garcia, F.; et al. SNP Discovery and Association Study for Growth, Fatness and Meat Quality Traits in Iberian Crossbred Pigs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, G.; Fu, Y.; Zuo, B.; Ren, Z.; Xu, D.; Lei, M.; Zheng, R.; Xiong, Y.Z. Molecular Characterization, Expression Profile and Association Analysis with Fat Deposition Traits of the Porcine APOM Gene. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2010, 37, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, M.; Wu, H.Y.; Guo, L.; Mei, S.Q.; Zhang, P.P.; Li, F.E.; Zheng, R.; Deng, C.Y. Imprinting Analysis of Porcine DIO3 Gene in Two Fetal Stages and Association Analysis with Carcass and Meat Quality Traits. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 2329–2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyszyńska-Koko, J.; Pierzchała, M.; Flisikowski, K.; Kamyczek, M.; Rózycki, M.; Kurył, J. Polymorphisms in Coding and Regulatory Regions of the Porcine MYF6 and MYOG Genes and Expression of the MYF6 Gene in m. Longissimus Dorsi versus Productive Traits in Pigs. J. Appl. Genet. 2006, 47, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, K.R.; Velez-Irizarry, D.; Casiró, S.; Steibel, J.P.; Raney, N.E.; Bates, R.O.; Ernst, C.W. Integrated Genome-Wide Analysis of MicroRNA Expression Quantitative Trait Loci in Pig Longissimus Dorsi Muscle. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 644091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, L. Expression and Genetic Effects of GLI Pathogenesis-Related 1 Gene on Backfat Thickness in Pigs. Genes 2022, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinar, M.U.; Kayan, A.; Uddin, M.J.; Jonas, E.; Tesfaye, D.; Phatsara, C.; Ponsuksili, S.; Wimmers, K.; Tholen, E.; Looft, C.; et al. Association and Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (EQTL) Analysis of Porcine AMBP, GC and PPP1R3B Genes with Meat Quality Traits. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 4809–4821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Zhuang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, J.; Zhou, S.; Ruan, D.; Xu, C.; Hong, L.; Gu, T.; et al. A Composite Strategy of Genome-Wide Association Study and Copy Number Variation Analysis for Carcass Traits in a Duroc Pig Population. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Song, K.D.; Seo, M.; Caetano-Anollés, K.; Kim, J.; Kwak, W.; Oh, J.-d.; Kim, E.S.; Jeong, D.K.; Cho, S.; et al. Exploring Evidence of Positive Selection Reveals Genetic Basis of Meat Quality Traits in Berkshire Pigs through Whole Genome Sequencing. BMC Genet. 2015, 16, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngu, N.; Nhan, N. Analysis of Troponin I Gene Polymorphisms and Meat Quality in Mongcai Pigs. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 42, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Kim, S.-W.; Kim, W.-I.; Kim, K.-S. Association Analyses of DNA Polymorphisms in Immune-Related Candidate Genes GBP1, GBP2, CD163, and CD169 with Porcine Growth and Meat Quality Traits. J. Biomed. Res. 2015, 16, 040–046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.D.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, H.K.; Song, K.D. Effect of a C-MYC Gene Polymorphism (g.3350G>C) on Meat Quality Traits in Berkshire. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 28, 1545–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Yan, D.; Sun, H.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Pan, Y.; Lu, S. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifying Genetic Variants Associated with Carcass Backfat Thickness, Lean Percentage and Fat Percentage in a Four-Way Crossbred Pig Population Using SLAF-Seq Technology. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Xu, Z.Y.; Lei, M.G.; Li, F.E.; Deng, C.Y.; Xiong, Y.Z.; Zuo, B. Association of 3 Polymorphisms in Porcine Troponin I Genes (TNNI1 AndTNNI2) with Meat Quality Traits. J. Appl. Genet. 2010, 51, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hernández-Montiel, W.; Meza-Villalvazo, V.M.; Dzib-Cauich, D.A.; Zaldívar-Cruz, J.M.; Abad-Zavaleta, J.; Cob-Calan, N.N.; Valenzuela-Jiménez, N.; Zamora-Bustillos, R.; Osorio-Terán, A.I. Genes and Gene Functions Associated with Morphological, Productive, Reproductive, and Carcass Quality Traits in Pigs: A Functional Bioinformatics Approach. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020153

Hernández-Montiel W, Meza-Villalvazo VM, Dzib-Cauich DA, Zaldívar-Cruz JM, Abad-Zavaleta J, Cob-Calan NN, Valenzuela-Jiménez N, Zamora-Bustillos R, Osorio-Terán AI. Genes and Gene Functions Associated with Morphological, Productive, Reproductive, and Carcass Quality Traits in Pigs: A Functional Bioinformatics Approach. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(2):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020153

Chicago/Turabian StyleHernández-Montiel, Wilber, Víctor M. Meza-Villalvazo, Dany A. Dzib-Cauich, Juan M. Zaldívar-Cruz, José Abad-Zavaleta, Nubia Noemi Cob-Calan, Nicolás Valenzuela-Jiménez, Roberto Zamora-Bustillos, and Amada I. Osorio-Terán. 2026. "Genes and Gene Functions Associated with Morphological, Productive, Reproductive, and Carcass Quality Traits in Pigs: A Functional Bioinformatics Approach" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 2: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020153

APA StyleHernández-Montiel, W., Meza-Villalvazo, V. M., Dzib-Cauich, D. A., Zaldívar-Cruz, J. M., Abad-Zavaleta, J., Cob-Calan, N. N., Valenzuela-Jiménez, N., Zamora-Bustillos, R., & Osorio-Terán, A. I. (2026). Genes and Gene Functions Associated with Morphological, Productive, Reproductive, and Carcass Quality Traits in Pigs: A Functional Bioinformatics Approach. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(2), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48020153