Uncovering the Molecular Response of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) to 12C6+ Heavy-Ion Irradiation Through Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Assessment of Morphological Traits

2.3. Measurement of Soil and Plant Analyzer Development (SPAD)

2.4. GC-MS/MS Analysis of Volatile Compounds in Oregano Leaves

2.5. Transcriptome Sequencing and Analysis

2.6. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) Analysis for Gene Expression

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Generation of Heavy-Ion Irradiated Mutants and Phenotypic Characterization of NZ1 and NZ2 in Origanum vulgare L.

3.2. Metabolomics Profiling of Volatile Compounds in Heavy-Ion-Induced Oregano Mutants (NZ1, NZ2) and the Wild-Type

3.3. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Dynamic Changes in Gene Expression in Heavy-Ion Induced Oregano Mutants (NZ1, NZ2) and the Wild-Type (WT)

3.4. GO Annotation and KEGG Enrichment Analysis of DEGs

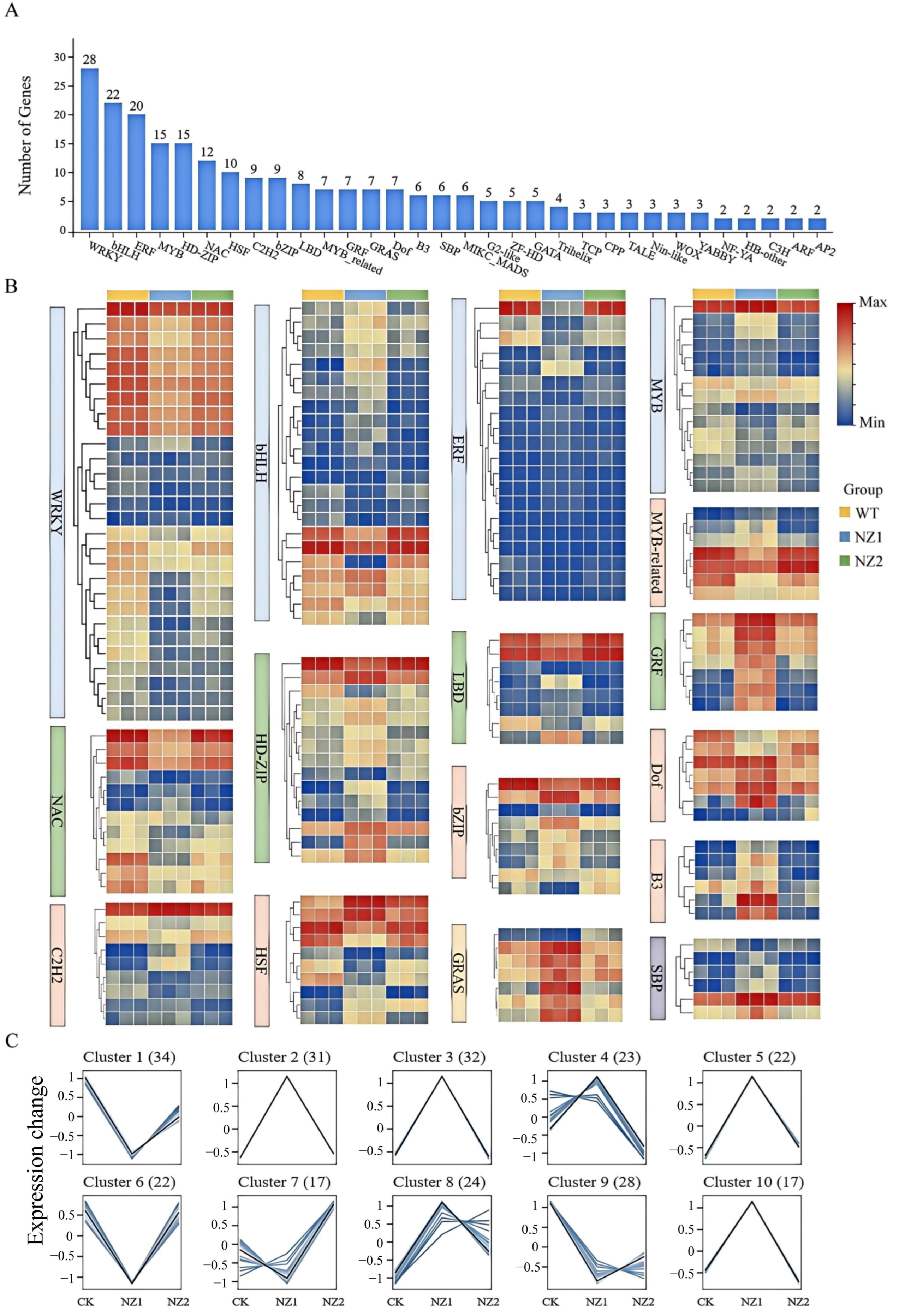

3.5. Analysis of Transcription Factors Among DEGs

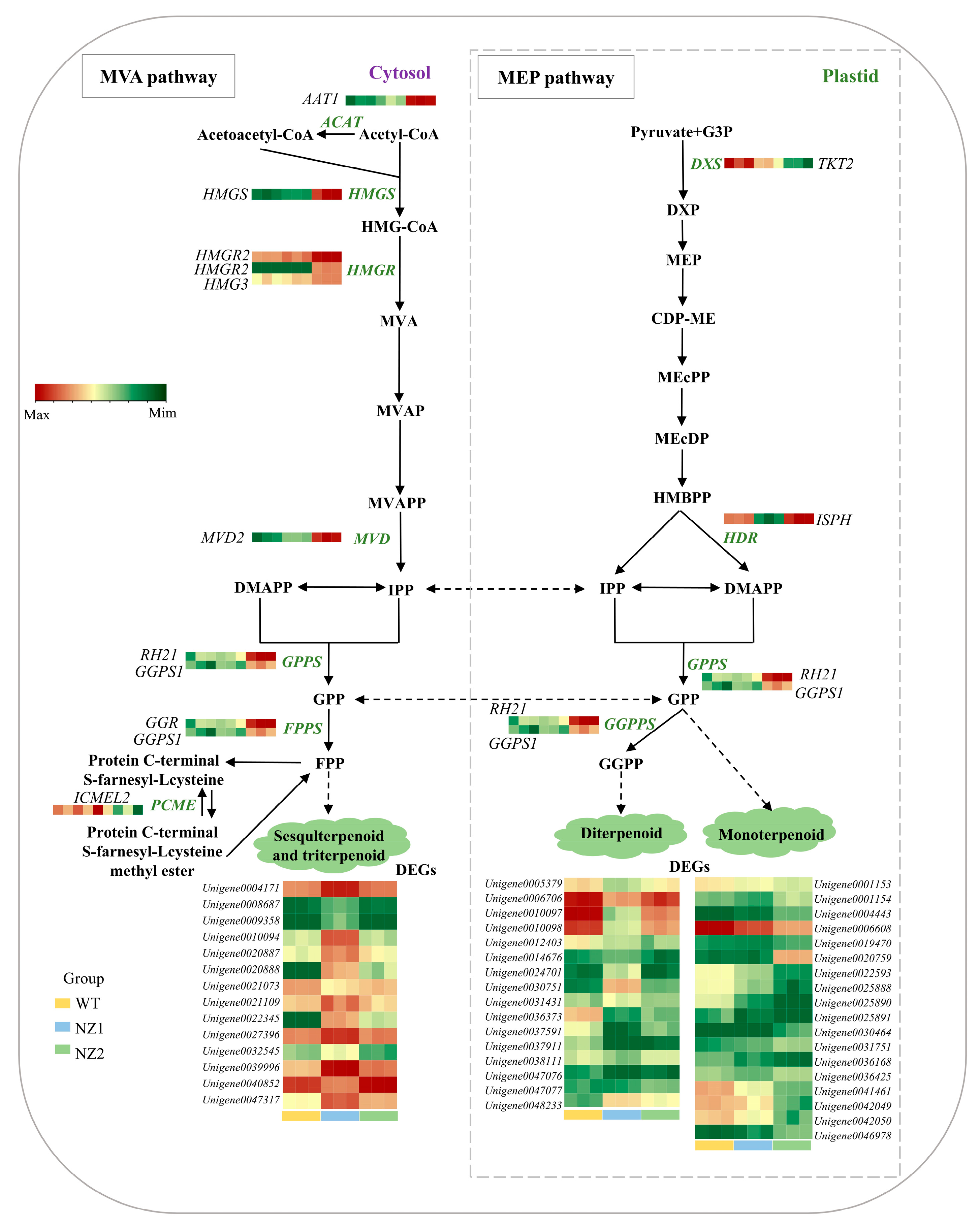

3.6. Analysis of DEGs Involved in the Terpenoids Biosynthesis Pathways in Origanum vulgare L.

3.7. Identification of OvTPSs and OvCYP71Ds in the Thymol and Carvacrol Biosynthesis Pathway in Origanum vulgare L.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vârban, D.; Zăhan, M.; Crișan, I.; Pop, C.R.; Gál, E.; Ștefan, R.; Rotar, A.M.; Muscă, A.S.; Meseșan, Ș.D.; Horga, V.; et al. Unraveling the Potential of Organic Oregano and Tarragon Essential Oils: Profiling Composition, FT-IR and Bioactivities. Plants 2023, 12, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, R.; Yan, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, H.; Bai, H.; Cui, H.; Li, J.; Shi, L. Unraveling the Biosynthesis of Carvacrol in Different Tissues of Origanum vulgare L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xia, F.; Bai, H.; Li, H.; Shi, L. Comparison of Origanum Essential Oil Chemical Compounds and Their Antibacterial Activity against Cronobacter sakazakii. Molecules 2022, 27, 6702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurinovic, B.; Popovic, M.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Trivic, S. Antioxidant Capacity of Ocimum basilicum L. and Origanum vulgare L. Extracts. Molecules 2011, 16, 7401–7414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Kang, J.; Yang, R.; Li, H.; Cui, H.; Bai, H.; Tsitsilin, A.; Li, J.; Shi, L. Multidimensional exploration of essential oils generated via eight oregano cultivars: Compositions, chemodiversities, and antibacterial capacities. Food Chem. 2022, 374, 131629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Li, J.; Shi, L. A Carvacrol-Rich Essential Oil Extracted from Oregano (Origanum vulgare “Hot & Spicy”) Exerts Potent Antibacterial Effects Against Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 741861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanam, S.; Mishra, P.; Faruqui, T.; Alam, P.; Albalawi, T.; Siddiqui, F.; Rafi, Z.; Khan, S. Plant-based secondary metabolites as natural remedies: A comprehensive review on terpenes and their therapeutic applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1587215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhary, N.; Bawari, S.; Burcher, J.T.; Sinha, D.; Tewari, D.; Bishayee, A. Targeting Cell Signaling Pathways in Lung Cancer by Bioactive Phytocompounds. Cancers 2023, 15, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, L.; Tang, K. New insights into artemisinin regulation. Plant Signal Behav. 2017, 12, e1366398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Lan, F.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Tian, H.; Bu, X.; Chen, R.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. Paclitaxel anti-cancer therapeutics: From discovery to clinical use. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2025, 23, 769–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglarz, Z.; Kosakowska, O.; Przybył, J.; Pióro-Jabrucka, E.; Bączek, K. The Quality of Greek Oregano (O. vulgare L. Subsp. hirtum (Link) Ietswaart) and Common Oregano (O. vulgare L. Subsp. vulgare) Cultivated in the Temperate Climate of Central Europe. Foods 2020, 9, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharopov, F.; Braun, M.S.; Gulmurodov, I.; Khalifaev, D.; Isupov, S.; Wink, M. Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Essential Oils of Selected Aromatic Plants from Tajikistan. Foods 2015, 4, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Zha, W.; Li, W.; Wang, J.; You, A. Advances in the Biosynthesis of Terpenoids and Their Ecological Functions in Plant Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Wang, X. Biosynthesis of monoterpenoid and sesquiterpenoid as natural flavors and fragrances. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 65, 108151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, S.; Liao, P.; Crocoll, C.; Boachon, B.; Förster, C.; Leidecker, F.; Wises, N.; Zhao, D.; Wood, J.; Buell, C.; et al. The biosynthesis of thymol, carvacrol, and thymohydroquinone in Lamiaceae proceeds via cytochrome P450s and a short-chain dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2110092118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvi, S.; Anantika, S.; Tabasum, K.; Arun, K. A bZIP type transcription factor from Picrorhiza kurrooa modulates the expression of terpenoid biosynthesis genes in Nicotiana benthamiana. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 169, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shao, Y.; Mu, D.; Zhou, Y.; He, J.; Zhao, H.; Wilson, I.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Qiu, D.; et al. Genome-wide identification of TCP transcription factors and functional role of UrTCP4 in regulating terpenoid indole alkaloids biosynthesis in Uncaria rhynchophylla. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 40, 100406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Mu, X.; Wang, S.; Wei, Q.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Wen, B.; Li, M.; et al. Integrated metabolome and transcriptome analysis provides insights into the mechanisms of terpenoid biosynthesis in tea plants (Camellia sinensis). Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, F.; Xia, F.; Bai, H.; Li, H.; Shi, L. Exogenous application of methyl jasmonate affects the transcriptome of terpenoid biosynthesis genes in lavender and functional characterization of the candidate gene LabHLH74. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 227, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikegaya, T.; Shirasawa, K.; Fujino, K. Strategies to assess genetic diversity for crop breeding. Euphytica 2023, 219, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Raigar, O.; Chahota, R. Estimation of genetic diversity and its exploitation in plant breeding. Bot. Rev. 2022, 88, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ren, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, M.; Lei, C.; Chai, R.; Zhang, L.; Lu, D. Strategies to improve the efficiency and quality of mutant breeding using heavy-ion beam irradiation. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 735–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Kazama, Y.; Ishii, K.; Ohbu, S.; Shirakawa, Y.; Abe, T. Comprehensive identification of mutations induced by heavy-ion beam irradiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2015, 82, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, J.; Irshad, A.; Zhao, L.; Guo, H.; Xiong, H.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. Physiological and Differential Proteomic Analysis at Seedling Stage by Induction of Heavy-Ion Beam Radiation in Wheat Seeds. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 942806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, K.; Yuan, R.; Abdelahany, A.; Lamlom, S. Uncovering molecular mechanisms of soybean response to 12C6+ heavy ion irradiation through integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 289, 117689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Zheng, L.; Tian, H.; Li, W.; Wang, J. Transcriptome responses involved in artemisinin production in Artemisia annua L. under UV-B radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 140, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Shen, Q.; Lv, P.; Sun, C. Comparative metabolomic analyses of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo responding to UV-B radiation reveal variations in the metabolisms associated with its bioactive ingredients. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, N.; Watanabe, A.; Asakawa, T.; Sasaki, M.; Hoshi, N.; Naito, Z.; Furusawa, Y.; Shimokawa, T.; Nishihara, M. Biological effects of ion beam irradiation on perennial gentian and apple. Plant Biotechnol. 2018, 35, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.; Schmittgen, T. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C (T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, A.; Bhuj, B.; Srivastava, R.; Chand, S.; Singh, N.; Bisht, Y.; Dasila, H.; Bhatt, R.; Perveen, K.; Bukhari, N. Determination of lethal and mutation induction doses of gamma rays for gladiolus (Gladiolus grandifloras Hort.) genotypes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Wei, J. Research progress on radiation breeding of Chinese medicinal materials. Chin. Herb. Med. 2023, 54, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.; Abdullah, N.; Hussin, G.; Ramli, A.; Rahim, H.; Miah, G.; Usman, M. Principle and application of plant mutagenesis in crop improvement: A review. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2016, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Feng, H.; Du, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Feng, Z.; Cui, T.; Zhou, L. Genetic polymorphisms in mutagenesis progeny of Arabidopsis thaliana irradiated by carbon-ion beams and gamma-rays irradiations. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2020, 96, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Chen, G.; Liu, Q.; Luo, S.; Shu, Q.; Zhou, L. Mutagenic effects of carbon-ion irradiation on dry Arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2014, 759, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Luo, S.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Cui, T.; Li, W.; Yu, L.; Feng, H.; Chen, Y.; Mu, J.; et al. Identification of substitutions and small insertion-deletions induced by carbon-ion beam irradiation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.; Kim, S.; Hwang, J.; Kim, Y.; Kang, H.; Kwon, S.; Ryu, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, S. Construction of mutation populations by gamma-ray and carbon beam irradiation in chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 57, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Narasako, Y.; Abe, T.; Kunitake, H.; Hirano, T. Comprehensive effects of heavy-ion beam irradiation on sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.). Plant Biotechnol. 2022, 39, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, X.; Ren, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, L.; Li, W.; et al. Genome and transcriptome-based characterization of high energy carbon-ion beam irradiation induced delayed flower senescence mutant in Lotus japonicus. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Wei, W.; Jin, W.; Zhou, L. Comparative proteomics reveals energy and carbon metabolism changes in Scenedesmus quadricauda mutants induced by heavy-ion beam irradiation. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 406, 130965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zang, Y.; Sun, R.; Feng, R.; Zhu, H.; Li, X. Recent Advances of Terpenoids with Intriguing Chemical Skeletons and Biological Activities. Chin. J. Chem. 2025, 43, 443–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Hao, D.; Xiao, P. Research progress of Chinese herbal medicine compounds and their bioactivities: Fruitful 2020. Chin. Herb. Med. 2022, 14, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Li, P.; Ma, X.; Wang, F.; Li, L.; Xin, Z.; et al. Radiation-specific metabolic reprogramming drives yield-quality balance in Astragalus mongholicus: Comparative insights from gamma-ray and heavy-ion beam irradiation. Plant Stress 2025, 18, 101027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Kollie, L.; Dong, J.; Liang, Z. Molecular networks of secondary metabolism accumulation in plants: Current understanding and future challenges. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 201, 116901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, P.; Singh, S.K.; Patra, B.; Sui, X.; Pattanaik, S.; Yuan, L. A differentially regulated AP2/ERF transcription factor gene cluster acts downstream of a MAP kinase cascade to modulate terpenoid indole alkaloid biosynthesis in Catharanthus roseus. New Phytol. 2017, 213, 1107–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.; Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, M.; Feng, Q.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, K.; Wei, L.; Han, Z.; et al. Low temperature inhibits anthocyanin accumulation in strawberry fruit by activating FvMAPK3-induced phosphorylation of FvMYB10 and degradation of chalcone synthase 1. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 1226–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi-Kaboshi, M.; Okada, K.; Kurimoto, L.; Murakami, S.; Umezawa, T.; Shibuya, N.; Yamane, H.; Miyao, A.; Takatsuji, H.; Takahashi, A.; et al. A rice fungal MAMP-responsive MAPK cascade regulates metabolic flow to antimicrobial metabolite synthesis. Plant J. 2010, 63, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yan, T.; Qian, S.; Lu, X.; Pan, Q.; Huang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, M.; Jiang, W.; et al. Glandular trichome-specific WRKY1 promotes artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua. New Phytol. 2017, 214, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.; Meng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, S. Phosphorylation of a WRKY transcription factor by two pathogen-responsive MAPKs drives phytoalexin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, T.; Li, K.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, W.; et al. A novel WRKY34-bZIP3 module regulates phenolic acid and tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Metab. Eng. 2022, 73, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, A.; Brockman, A.; Aguirre, L.; Campbell, A.; Bean, A.; Cantero, A.; Gonzalez, A. Advances in the MYB-bHLH-WD repeat (MBW) pigment regulatory model: Addition of a WRKY factor and co-option of an anthocyanin MYB for betalain regulation. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017, 58, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sun, W.; Chen, J.; Tan, H.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Q.; Ji, Q.; Gao, S.; Chen, L.; Chen, S.; et al. SmMYC2a and SmMYC2b played similar but irreplaceable roles in regulating the biosynthesis of tanshinones and phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22852, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7201.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Hu, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, X. The jasmonate-responsive AP2/ERF transcription factors AaERF1 and AaERF2 positively regulate artemisinin biosynthesis in Artemisia annua L. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Tan, H.; Ma, Z.; Huang, J. DELLA proteins promote anthocyanin biosynthesis via sequestering MYBL2 and JAZ suppressors of the MYB/bHLH/WD40 complex in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Jie, Z.; Cao, H.; Huang, J.; Xiu, H.; Luo, T.; Luo, Z. Molecular cloning and expression profile of an abiotic stress and hormone responsive MYB transcription factor gene from Panax ginseng. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Umemura, Y.; Ohmetakagi, M. AtMYBL2, a protein with a single MYB domain, acts as a negative regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008, 55, 954–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagegowda, D. Plant volatile terpenoid metabolism: Biosynthetic genes, transcriptional regulation and subcellular compartmentation. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2965–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranová, E.; Coman, D.; Gruissem, W. Network analysis of the MVA and MEP pathways for isoprenoid synthesis. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 665–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagegowda, D.; Gupta, P. Advances in biosynthesis, regulation, and metabolic engineering of plant specialized terpenoids. Plant Sci. 2020, 294, 110457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barja, M.; Rodriguez-Concepcion, M. Plant geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthases: Every (gene) family has a story. aBIOTECH 2021, 2, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tholl, D. Biosynthesis and biological functions of terpenoids in plants. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2015, 148, 63–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Tholl, D.; Bohlmann, J.; Pichersky, E. The family of terpene synthases in plants: A mid-size family of genes for specialized metabolism that is highly diversified throughout the kingdom. Plant J. 2011, 66, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, U.; Tissier, A. Cytochrome P450 enzymes: A driving force of plant diterpene diversity. Phytochemistry 2019, 161, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Li, P.; Lu, X. Research advances in cytochrome P450-catalysed pharmaceutical terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2019, 70, 4619–4630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tan, Z.; Li, L.; Liang, Y.; Li, C.; Su, X.; Lu, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, L.; Su, M.; Cao, Y.; et al. Uncovering the Molecular Response of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) to 12C6+ Heavy-Ion Irradiation Through Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2026, 48, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010007

Tan Z, Li L, Liang Y, Li C, Su X, Lu D, Sun Y, Wang L, Su M, Cao Y, et al. Uncovering the Molecular Response of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) to 12C6+ Heavy-Ion Irradiation Through Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2026; 48(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Zhengwei, Lei Li, Yan Liang, Chunming Li, Xiaoyu Su, Dandan Lu, Yao Sun, Lina Wang, Mengfan Su, Yiwen Cao, and et al. 2026. "Uncovering the Molecular Response of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) to 12C6+ Heavy-Ion Irradiation Through Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 48, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010007

APA StyleTan, Z., Li, L., Liang, Y., Li, C., Su, X., Lu, D., Sun, Y., Wang, L., Su, M., Cao, Y., & Liang, H. (2026). Uncovering the Molecular Response of Oregano (Origanum vulgare L.) to 12C6+ Heavy-Ion Irradiation Through Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 48(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb48010007