Abstract

Background/Objectives: Epilepsy is characterized by recurrent, unprovoked, self-limiting seizures of genetic, acquired, or unknown origin. It affects more than 50 million people worldwide. The prevalence in Peru is 11.9–32.1 per 1000 people. Our objective was to describe the association between CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms and adverse reactions induced by antiseizure medications among Peruvian patients with epilepsy. Methods: A descriptive observational study was conducted on Peruvian patients with epilepsy. Non-probability, non-randomized, purposive sampling was carried out through consecutive inclusion. Genomic DNA was obtained from venous blood samples. Genotypes were determined by real-time PCR using specific TaqMan probes to identify the alleles of interest. Results: In total, 89 Peruvian patients with epilepsy were recruited at the Alberto Sabogal Sologuren National Hospital-ESSALUD: 45 were male (23.6 ± 10.0 years) and 44 were female (24.0 ± 12.4 years). The observed frequencies for CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, and CYP2C19*17 were 0.034 (T allele), 0.034 (C allele), 0.14 (A allele), 0.00 (A allele), and 0.03 (T allele), respectively. Patients with intermediate and poor metabolic phenotypes of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 had a significantly higher risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) (OR = 3.75; 95%CI: 1.32–10.69; p = 0.013), compared with normal metabolizers. Polytherapy was a predictor increasing the likelihood of ADRs (OR = 4.33; 95% CI: 1.46–12.80; p = 0.008). Conclusions: In this cohort of Peruvian patients with epilepsy, the reduced-function alleles CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP2C19*2, associated with decreased metabolic activity, were significantly linked to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions induced by antiseizure medications. Polytherapy further heightened this risk. Collectively, these findings highlight the clinical relevance of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genotyping to enhance the safety of antiseizure pharmacotherapy in Latin American settings, where pharmacogenomic evidence remains limited.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Epilepsy is one of the most prevalent chronic neurological disorders worldwide, characterized by recurrent unprovoked and self-limited seizures of genetic, acquired, or unknown origin [1,2,3]. It affects more than 50 million people globally, and 80% of these cases occur in developing countries [4,5]. The prevalence of epilepsy in Peru is estimated at 11.9–32.1 per 1000 people—a range that reflects regional heterogeneity in published Peruvian studies [6,7]. Antiseizure medications (ASMs) of the aromatic type [carbamazepine (CBZ), oxcarbazepine (OXC), phenytoin (PHT), phenobarbital (PHB), levetiracetam (LEV), lamotrigine (LTG), lacosamide, primidone, rufinamide, and zonisamide] and non-aromatic type [valproic acid (VPA) and pregabalin] are used to control seizures [8,9]. These medications develop adverse drug reactions in 22 to 31% of patients with epilepsy [10]. Aromatic ASMs are associated with life-threatening type B hypersensitivity reactions, such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), or drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) [9,11]; additionally, carbamazepine induces photosensitivity [12], and phenytoin causes gingival hyperplasia, hirsutism, and acne [12,13].

1.2. Genetic and Non-Genetic Factors Associated with Drug Resistance to Antiseizure Medication

It has been reported that approximately 30% of patients do not respond to treatment with ASMs [14,15]. This could be explained by drug resistance to ASMs, which may be attributed to both non-genetic factors (such as sex, age, ethnicity, seizure type, early onset of epilepsy, suboptimal dosage, lack of adherence to treatment, and alcohol abuse) and genetic factors [16]. Among the genetic factors with the most evidence for their role in drug resistance are polymorphisms in cytochrome p450 genes (CYP2C9 and CYP2C19), genes that encode for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes (UGT1A4, UGT2B7 and UGT2B15) [16], and ABC genes (ATP-binding cassette) such as ABCB1 (MDR1) which encodes P-glycoprotein transporter [17,18] that is overexpressed in epileptogenic tissues [19]. Likewise, the mutation of the SCN2A gene [c.56 G>A (rs17183814] is known to be associated with resistance to multiple ASMs [20].

1.3. Pharmacogenetics and Personalized Medicine in Epilepsy

Through personalized or precision medicine, the goal is to individualize the dose from the outset of pharmacological therapy, taking into account the pharmacogenetic profile according to ethnicity, mixed race, origin, sex, and lifestyle, with the aim of maintaining plasma concentrations within the therapeutic range [21,22]. Therefore, it is essential to apply pharmacogenomics and precision medicine in epilepsy, which will facilitate individualization of the dose to optimize efficacy and minimize adverse drug reactions (ADRs) [23]. In this context, it is important to analyze the two main pharmacogenes of ASMs, such as the CYP2C9 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 10, region 24 (10q24), which has more than 61 allelic variants and multiple suballeles. CYP2C9*1 is its wild allelic version, which, when combined, forms the CYP2C9*1/*1 genotype that predicts normal metabolism. The two most common variants with decreased enzyme activity are CYP2C9*2 (rs1799853) and CYP2C9*3 (rs1057910), while the genotypes CYP2C9*2/*3 and CYP2C9*3/*3 are predictors of poor metabolic phenotypes [24,25,26,27]. The frequency of CYP2C9*2 in Caucasians is 10–17%, in Africans 2–4%, and in Asians 6%; while the frequency of CYP2C9*3 in Caucasian populations is 6–7%, in Asians 2–11%, and it is less prevalent in African or African American ethnic groups (1%) [28]. Meanwhile, the CYP2C19 gene is mapped to the long arm of chromosome 10, region 24.1 (10q24.1), and is highly polymorphic, with more than 25 allelic variants. The wild allele CYP2C19*1 gives rise to CYP2C19*1/*1, responsible for predicting normal metabolizers by the CYP2C19 enzyme. The CYP2C19*2 (rs4244285; c.681G>A) and CYP2C19*3 (rs4986893; c.636G>A) alleles form homozygous CYP2C19*2/*2 and CYP2C19*3/*3 genotypes, respectively, and predict poor metabolizers. The frequencies of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers are estimated at 2% in Caucasian populations, 5% in Africans, and 15% in Asians [29,30]. The CYP2C19*17 allele (rs12248560) can account for the CYP2C19*17/*17 or CYP2C19*1/*17 genotypes, which predict rapid metabolizers [25,31,32].

Carriers with CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 SNPs predictive of rapid metabolism are associated with decreased drug efficacy [25,31,32]. In contrast, poor metabolizers exhibit a decrease in the safety of ASMs; for example, CYP2C9*3/*3 carriers show high plasma levels of PHT [27] and valproic acid which can induce ADRs [33]. In CYP2C19*2/*2 carriers, elevated plasma levels (69 mg/L) of PHT have been observed, leading to neurotoxicity (manifested as dizziness, nystagmus, ataxia, and excessive sedation) [34]. Therefore, it is recommended to reduce the PHT dose in intermediate and poor metabolizers [35].

1.4. Enzymes That Metabolize Antiseizure Medication

These genes encode their respective enzymes which metabolize various drugs in clinical use, including ASMs, such as VPA which is metabolized through phase I oxidation with the participation of CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2A6, and CYP2B6, forming 4-hydroxyvalproic acid and 4-ene-VPA. Additionally, it is biotransformed by UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 (UGT2B7) and other UGTs [36,37,38,39]. Phenytoin (PHT) is biotransformed into 3′,4′-phenytoin epoxide by the action of CYP2C9 (90%) and CYP2C19 (10%). The metabolite then undergoes two biotransformation processes: first, 3′,4′-dihydrodiol phenytoin is generated by the action of epoxide hydrolase; subsequently, the main metabolite 5-(p-hydroxyphenyl)-5-phenylhydantoin (p-HPPH) is formed with the participation of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 [40,41]. Likewise, PHB is metabolized through CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 into a p-hydroxyphenyl derivative [42].

1.5. Pharmacogenetic Studies on ASM in Peru

Despite their global clinical importance, pharmacogenomic studies on ASMs in Peru are limited compared to other countries in Latin America and around the world. Additionally, routine pharmacogenomic testing is not recommended in clinical practice, which presents a challenge for researchers to generate scientific evidence and validate results in order to propose the implementation of personalized medicine in Peru.

1.6. Objective

The objective of this study was to describe the association between CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 polymorphisms and ADRs induced by antiseizure medication in Peruvian patients with epilepsy.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Characteristics and Medication Data of Patients

The present study describes the allelic variants of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, evaluating their association with ADRs induced by ASMs in Peruvian patients with epilepsy. The patients in the study were diagnosed by electroencephalography (n = 75) and by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging (n = 14) with no structural alterations. They were classified according to the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) into generalized seizure (n = 34) and focal seizure (n = 55). All participants had been undergoing treatment with ASMs for more than 2 years. In total, 43 had a family history of seizures (28 male, 15 female), and 55 were well controlled (no recurrence) at the time of the study, while 34 patients were uncontrolled. Those considered poor responders during the 2–6-month treatment were prescribed polytherapy and scheduled for short periods of clinical and pharmacological evaluation. A total of 45 patients were included in monotherapy with VPA, PHT, or PHB, while 44 were in polytherapy. A descriptive analysis was performed to characterize the participants, with continuous variables described as the mean and standard deviation (SD). The clinical and pharmacological characteristics of patients with epilepsy were compared by sex. Female patients received polytherapy (VPA + LTG + LEV) more frequently than males (50.0% vs. 28.9%; p = 0.069). Generalized epilepsy was more prevalent in women (47.7% vs. 28.9%), whereas focal seizures predominated in men (71.1% vs. 52.3%), although this did not reach significance (p = 0.0755). A family history of epilepsy was more common in males (62.2% vs. 34.1%; p = 0.0109). No differences in clinical control of epilepsy were observed between groups (p = 0.6657); see Table 1.

Table 1.

Anthropometric, clinical, and medication characteristics of patients with epilepsy.

2.2. Genes, Allelic Variants, and Genotypes

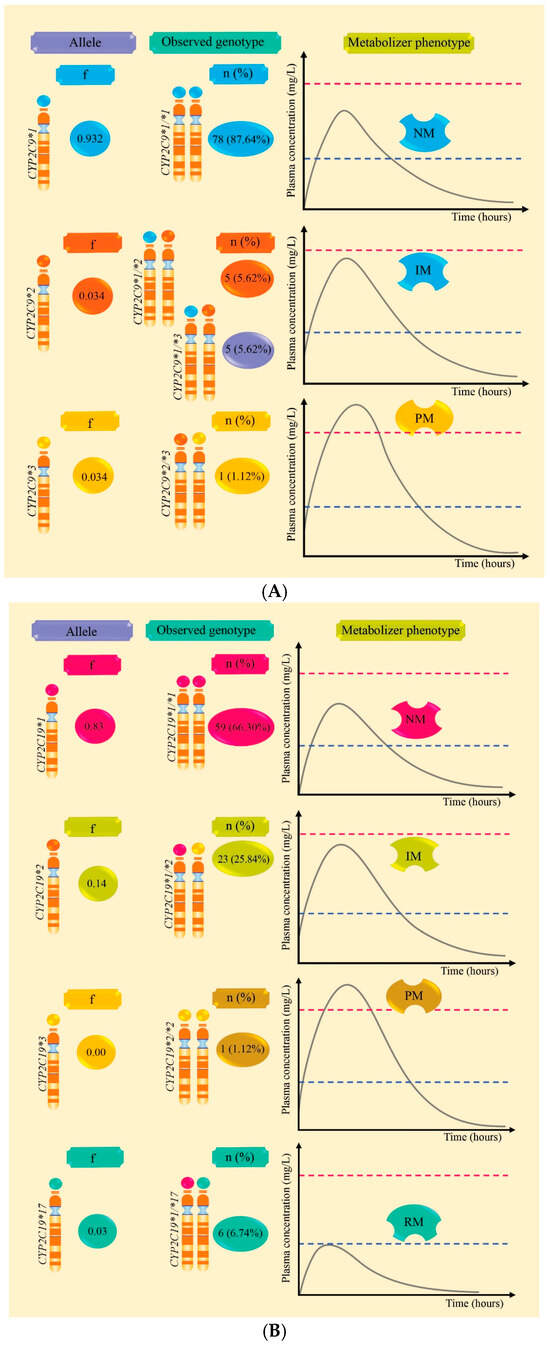

Table 2 and Figure 1A,B report the frequencies of alleles and genotypes, revealing a higher frequency of CYP2C19*2 (0.14) compared to CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 which both had a frequency of 0.034. CYP2C19*17 was identified with a frequency of 0.03, while CYP2C19*3 was not observed. These alleles constitute the genotypes CYP2C9*1/*2, CYP2C9*1/*3, and CYP2C19*1/*2, which predict intermediate metabolizers (IM). The CYP2C9*2/*3 and CYP2C19*2/*2 genotypes predict poor metabolizers (PM), whereas the CYP2C19*1/*17 genotype predicts rapid metabolizers (RM). Additionally, CYP2C9*1/*1 and CYP2C19*1/*1 predict normal metabolizers (NM).

Table 2.

Allele and genotype frequencies of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 in patients with epilepsy.

Figure 1.

Allele frequencies, CYP2C9/CYP2C19 genotypes, and plasma level curves according to metabolic phenotype in Peruvian patients with epilepsy are outlined. Part (A) presents the frequency of CYP2C9 alleles and the percentages of genotypes that predict normal (NM), intermediate (IM), and poor (PM) metabolizers. Part (B) presents the frequency of CYP2C19 alleles and the percentages of genotypes that predict normal (NM), intermediate (IM), poor (PM), and rapid metabolizers (RM).

2.3. Metabolic Phenotype Related to Adverse Drug Reactions Induced by Antiseizure Medication

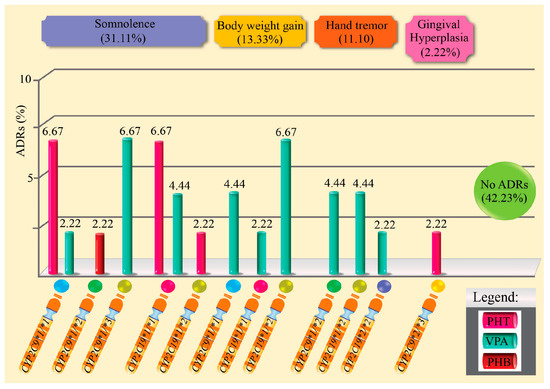

Table 3 and Figure 2 present the ADRs observed in patients with epilepsy treated with monotherapy, according to the CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genotypes. Of the 45 patients evaluated, 57.8% experienced at least one ADR, with the most frequent being drowsiness (31.1%), weight gain (13.3%), and hand tremor (13.3%). Gingival hyperplasia was uncommon (4.4%), and 42.2% did not experience any ADRs. No significant associations were found between the presence of ADRs and the CYP2C9 metabolizing phenotype (p = 0.156) or with the type of monotherapy drug (p = 0.417). However, relevant clinical trends were observed, such as a higher frequency of somnolence and weight gain in patients treated with VPA.

Table 3.

Genotypes and metabolic phenotypes related to adverse reactions induced by monotherapy with antiseizure medication.

Figure 2.

Percentage of adverse drug reactions induced by antiepileptic drugs in monotherapy and related to genotypes.

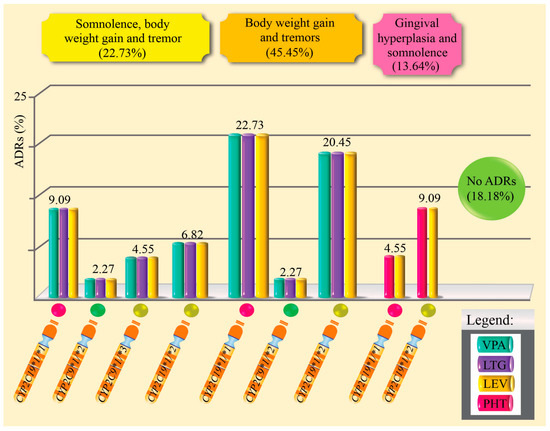

Table 4 and Figure 3 show the distribution of ADRs in patients with epilepsy treated with combination therapy, according to the CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 gene genotypes, their respective metabolic phenotypes, and the pharmacological regimen used. Of the total of 44 patients, 81.8% (n = 36) presented at least one ADR. The most frequent adverse reactions were weight gain and hand tremors (45.5%), followed by somnolence (22.7%), and to a lesser extent, gingival hyperplasia combined with somnolence (13.6%). Only 18.2% of patients (n = 8) did not experience any ADRs. When analyzing the metabolic phenotype of the CYP2C9 gene, it was observed that intermediate metabolizers (IM) had a higher proportion of ADRs compared to normal metabolizers (NM). Specifically, 97.0% of patients with the IM phenotype experienced at least one ADR, while in the NM group, the frequency was 73.7%. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.904; chi-square test). Regarding the type of polytherapy used, it was found that the VPA + LTG + LEV combination was associated with a higher number of adverse drug reactions compared to the PHT + LEV regimen. This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.0015; Fisher’s exact test), suggesting a possible influence of the type of pharmacological combination on the occurrence of adverse drug reactions.

Table 4.

Genotypes and metabolic phenotypes related to adverse reactions induced by polytherapy with antiseizure medication.

Figure 3.

Percentage of adverse drug reactions induced by antiepileptic drugs in polytherapy and related to genotypes.

In the multivariate analysis, two independent variables showed statistically significant associations with the presence of ADRs. Intermediate and PM patients for CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 were found to have a 3.75 times higher probability of experiencing ADRs compared to normal metabolizer patients (p = 0.013). Additionally, it was shown that the likelihood of presenting ADRs is 4.33 times greater in patients treated with polytherapy (p = 0.008). In contrast, the type of seizure (focal vs. generalized) was not significantly associated with the risk of ADRs (p = 0.379); see Table 5.

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis between adverse reactions and independent variables.

3. Discussion

3.1. Interpretation of Findings and Comparison with Literature

The dose of ASMs administered in male and female epilepsy patients influences absorption. Previous studies have shown that there are several factors that influence absorption. For instance, the study by Martinez and Amidon (2002) indicates that gastric emptying time, intestinal transit time, pH of the absorption medium, blood flow at the absorption site, presystemic metabolism, gastrointestinal content, and disease state influence the intestinal absorption of drugs [43]. In addition to patient factors, age and sex [44], the physicochemical properties (solubility and pKa) [43], drug polymorphism (crystalline form and amorphous), and the characteristics of the pharmaceutical form (excipients, formulation, and technological process) also influence the absorption and bioavailability of drugs [45]. These differences may affect pharmacotherapeutic efficacy and increase the risk of ADRs.

The allele frequencies of CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3, and CYP2C19*17 were 3.4%, 3.4%, 14%, 0%, and 3%, respectively, among patients with epilepsy in the present study. Meanwhile, the frequencies of the CYP2C9*1/*2, CYP2C9*1/*3, and CYP2C19*1/*2 genotypes were 5.62%, 5.62%, and 25.84%, respectively; these genotypes predict IM. The frequency of the CYP2C9 polymorphism, as well as that of CYP2C9*1/*2, is similar to previous studies conducted in the Peruvian population, which found an allelic frequency of 4.6% for CYP2C9*2 [25] and a genotype frequency of 4.3% for CYP2C9*1/*2 [46]. This confirms that these variants are present in the study population regardless of health condition, indicating that they express enzymes with lower activity compared to the wild-type CYP2C9*1/*1 allele. Additionally, a frequency for CYP2C9*3 of 6.2% [25] to 6.25% [47] was found, suggesting that some frequencies remain consistent while others vary within the Peruvian population.

No studies were found concerning Peruvian patients with epilepsy. In this regard, when compared with other previously published studies on other populations, notable differences are observed. Lakhan et al. (2011) reported frequencies CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP2C19*2 of 8%, 23.4%, and 49%, respectively, in Indian patients [48]. Makowska et al. (2021) found in Polish children with epilepsy two alleles, CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C19*2, accounting for 26.3% and 30.5%, respectively [49]. In another study by Fohner et al. (2020), which involved patients with epilepsy treated with phenytoin, the population comprised 21 patients (5%) who self-identified as Asian; 18 (5%) as Black; 29 (8%) as Hispanic Caucasian; and 308 (81%) as non-Hispanic Caucasian [50]. In this population, the frequencies of CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 were observed to be 12.0% and 4.7%, respectively, with 20% for CYP2C19*17, 17% for CYP2C19*2, and 1% for CYP2C19*3. Likewise, Song et al. (2022) reported in patients with epilepsy from Yunnan Province, China, that the frequencies of CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3 were 33.1% and 3%, respectively, among patients receiving VPA treatment [51]. These differences are likely influenced by the tricontinental and Latin American ancestry of Peruvians, as well as the internal migration that occurs from the Andes and jungle to the Peruvian coast. This highlights the need to conduct analytical observational studies (cases/controls and cohorts) and randomized clinical trials (RCTs) in pharmacogenetics with a larger number of patients [52,53,54].

This study also identified a carrier of CYP2C9*2/3 (1.12%) and another of CYP2C192/*2 (1.12%), both of which predict PM; these patients were treated with PHT and VPA, respectively. Due to the decreased metabolism of drugs in intermediate metabolizers or the lack of metabolism in PM, serum levels may exceed minimum toxic concentrations, leading to ADRs. Previous studies have established the minimum effective plasma concentrations and the minimum toxic plasma concentrations for ASMs as follows: VPA 50–100 mg/L [39,55], PHT 10–20 mg/L [56,57], and PHB 10–40 mg/L [58]. However, other factors that influence the increase in plasma levels must also be considered, such as diet type, drug–nutrient interaction, volume of distribution, plasma protein binding [59], enzyme inhibitors [60], drug interactions in polytherapy [61], liver and kidney dysfunction, advanced age, and other variables [62].

This study evaluated the relationship between pharmacogenomic and clinical factors with the occurrence of ADRs in patients with epilepsy, using an internally validated logistic regression model. In total, 1000 bootstrap resampling iterations were performed to generate data sets and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated, yielding an average of 0.722 (95% CI: 0.683–0.747) which supports the robustness and adaptability of the model in the available sample despite the moderate sample size. The area under the curve was 0.747, indicating the good discriminatory capacity of the model. McFadden’s Pseudo R2 was 0.13, suggesting the reasonable explanatory power of the model in contexts with multiple clinical factors. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value was 102.99, analyzed as a comparative metric for alternative models. The confusion matrix revealed an overall accuracy of 69.7%, with a sensitivity of 80.6% (the ability to correctly identify patients with ADRs) and a specificity of 44.4% (the ability to identify those who did not experience ADRs). Therefore, intermediate and poor metabolizers for CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 were found to be associated with ADRs. Additionally, it was revealed that polytherapy is a significant predictors of ADRs, this result aligns with previously published prospective studies indicating an association between ASM polytherapy and a higher risk of ADRs [63,64,65,66].

The ADRs observed in the intermediate and poor metabolizer patients in the present study were not severe, in contrast to those described in previous research. PHT is associated with gingival hyperplasia, epigastric pain, drowsiness, lethargy, headache, confusion [67], immune thrombocytopenia [68], and risk of liver injury [69]. Additionally, tremor, weight gain, hair loss [48], metabolic acidosis, hyperammonemia, hepatotoxicity, thrombocytopenia, and gastrointestinal disorders have been reported for VPA [70].

It is worth noting that several investigations have associated genotypes with ADRs. The study by Orsini et al. (2018) found an association between CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 with the onset of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and severe VPA-induced hyperammonemia [71]. Monostory et al. (2019) observed decreased metabolism and increased plasma levels and ADRs due to VPA in carriers of CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 [72]. Similarly, Song et al. (2022) reported high plasma levels of VPA in carriers of CYP2C19*2 and CYP2C19*3, associated with the risk of ADRs [51]. Shnayder et al. (2023) described that CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 are associated with decreased metabolism and increased plasma levels of VPA [73]. Iannaccone et al. (2021) observed that carriers of CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 have increased plasma levels of VPA compared to the wild-type CYP2C9*1 allele [33]. Garg et al. (2022) found a significant association between CYP2C9*3 and the risk of gingival hyperplasia and PHT-induced rash [74]. Recently, Milosavljevic et al. (2024) reviewed the significant association of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genes with increased plasma levels of PHT and VPA [75]. Six carriers of CYP2C19*17 (rs12248560, g.-806C>T) were also found, a genotype which increases the transcription of genes encoding enzymes with increased metabolic activity [76]. In patients carrying the CYP2C19*1/*17 genotypes, which predict rapid metabolizers, no adverse reactions were observed in the present study. In rapid metabolizers, the minimum effective plasma concentration is not achieved which may contribute to resistance or therapeutic failure.

3.2. Clinical Importance

These findings reinforce the clinical importance of pharmacogenetic testing as a tool for identifying patients with rapid, intermediate, and poor metabolic phenotypes and for proposing personalized doses. This approach prioritizes monotherapy when feasible or rational combinations based on the genetic profile, plasma drug levels, and the patient’s clinical characteristics. The Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) has recommended that in CYP2C9 intermediate and poor metabolizers, the daily dose of PHT should be titrated according to clinical effect and plasma levels after 7–10 days [35].

3.3. Strengths and Limitations

The limitations of this study include the sample size of patients with epilepsy (n = 89). No relevant genes associated with adverse reactions to ASMs were identified, such as ABCB1 which encodes the P-glycoprotein (also called the ABCB1 transporter); ABCC2, which encodes the MRP2 transporter; UGT2B7, which encodes the enzyme that conjugates VPA; and SCN2A, which encodes the alpha subunit of the sodium channel. Additionally, this study did not include carbamazepine and the genes encoding the enzymes CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 that metabolize this drug. Plasma levels of ASMs were not evaluated. All of these limitations will be addressed in future research by our research group.

Furthermore, we have not studied the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) alleles that are common in populations outside of the Peruvian mestizo population. HLA-B*15:02 is common in populations from East Asia (6.9%), Oceania (5.4%), and South/Central Asia (4.6%) [77,78,79], with a frequency of 2.5% in Koreans, less than 1% in Japanese, Caucasian, Hispanic/South American, and Middle Eastern populations; it has not been observed in Africans [80]. Meanwhile, HLA-A*31:01 is observed in Japanese (8%), Hispanic/South American (6%), South Korean (5%), and Caucasian (3%) populations, as well as in South and Central Asian (2%) populations [80]. HLA-B*15:02 is associated with Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), while HLA-A*31:01 is linked to an increased risk of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS), as well as SJS/TEN induced by aromatic antiepileptic drugs [11,80]. Despite the modest sample size, this cohort provides baseline pharmacogenomic data from Peruvian patients with epilepsy, supporting the design of larger multicentric studies.

However, this observational study is the first to describe the allelic variants of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 associated with adverse reactions in patients with epilepsy from a reference hospital in the coastal area of Callao, Peru. Additionally, these findings could serve as important scientific evidence to enhance the potential for prescribing medications at personalized doses that ensure efficacy while minimizing ADRs. Future studies integrating multi-gene panels and therapeutic-drug monitoring could further validate these associations in larger Latin American cohorts.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design, Population, and Type of Sampling

A descriptive, observational, prospective, and cross-sectional study was designed. The study population consisted of 89 Peruvian patients diagnosed with generalized and focal seizures who attended the Neurology Service of the Alberto Sabogal Sologuren National Hospital (HNASS) of the Social Health Security (ESSALUD), between November 2023 and October 2024. A total of 45 (50.56%) male patients (range = 18–85 years) and 44 (49.44%) female patients (range = 18–79 years) were included. After signing their informed consent, they were called volunteer patients.

Sampling was non-probabilistic, convenient, non-random, intentional, and involved consecutive inclusion of patients with epilepsy according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients attending the Neurology Service of HNASS for routine clinical monitoring were invited to participate in the study. A total of 115 patients were informed about the purpose and importance of the study, and only 89 were selected according to the following inclusion criteria: patients diagnosed with epilepsy who were receiving ASMs as monotherapy (VPA, PHT, and PHB) or polytherapy (VPA + LTG + LEV or PHT + LEV) for more than two years; controlled patients with a good response to treatment; patients on polytherapy who were considered poor responders; adherence to treatment (taking medication at the indicated times and with 250 mL of water); a commitment not to self-medicate and to communicate if they required any medication other than for their condition; being Peruvian by birth and residing in the Province of Callao; being over 18 years of age; and a commitment to donate 5 mL of blood for SNP screening in CYP2C9 and CYP2C19, as well as signing informed consent before starting the study.

Fifteen patients were excluded due to lack of therapeutic follow-up and non-adherence to treatment. Eleven were excluded for being treated with carbamazepine or other medications not classified as ASMs, as well as pregnant patients and anyone who did not meet the inclusion criteria.

4.3. Obtaining Genomic DNA

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was obtained from the buffy coat of blood samples using a standard manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequently, gDNA was quantified by spectrophotometry using the Denovix® equipment (model DS-11, FX, Spectrophotometer™ Series, Wilmington, DE, USA). Samples were analyzed at two absorbance wavelengths, 260/280 nm and 260/230 nm, and were considered suitable when the absorbance ratios were equal to or greater than 1.7. gDNA samples were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

4.4. Genotypic Analysis

CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genotypes were determined by real-time PCR (RT-PCR) with the identification of allelic variants using TaqMan probes for genotyping assays (Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), which are capable of discriminating the identified SNPs CYP2C9*2 (rs1799853), CYP2C9*3 (rs1057910), CYP2C19*2 (rs4244285), CYP2C19*3 (rs4986893), and CYP2C19*17 (rs12248560). According to the standard protocol, the reaction mix consisted of 30 ng of gDNA, Genotyping Master Mix™ (Cat. No. 4371355), TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay™ (with corresponding probes and primers from Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and nuclease-free molecular-biology-grade water (HyPure, HyClone™Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), sufficient for a final reaction volume of 10 μL. Context-specific sequences are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Sequence for identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genes.

For amplification, the Stratagene Mx3000P™ equipment (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used; the program included an initial cycle of enzyme activation (AmpliTaq Gold® Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of 15 s of denaturation at 95 °C and 90 s of annealing and extension at 60 °C.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

To analyze the association between the seizure type and sex, as well as to evaluate sex differences in valproic acid pharmacotherapy, Fisher’s exact test was applied considering a value of p < 0.05 as significant. Phenytoin and phenobarbital were evaluated using the Kruskal–Wallis test to identify significant differences in the doses administered associated with sex and the type of antiseizure medication. The multivariate model identified factors associated with adverse drug reactions, considering independent variables selected by expert judgment: CYP2C9 metabolic phenotype, CYP2C19 phenotype, type of pharmacotherapy, and seizure type. The results were expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs), with significance set at p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the Python language (version 3.9), with the pandas libraries for data processing, stats models for multivariate logistic regression models, and scikit-learn for results validation.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Research Ethics Committee of the Alberto Sabogal Sologuren National Hospital-ESSALUD in Callao approved the protocol and informed consent for the study as a minimal-risk investigation, using blood samples from routine clinical practice, through Memorandum No. 098-CIEI-OIyD-GRPS-ESSALUD-2023. The subjects signed informed consent before participating and were referred to as volunteer patients. Each volunteer was assigned a code to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

5. Conclusions

In this cohort of Peruvian patients with epilepsy, the reduced-function alleles CYP2C9*2, CYP2C9*3, and CYP2C19*2, associated with decreased metabolic activity, were significantly linked to an increased risk of adverse drug reactions induced by antiseizure medications. Polytherapy further heightened this risk.

Collectively, these findings highlight the clinical relevance of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 genotyping to enhance the safety of antiseizure pharmacotherapy in Latin American settings, where pharmacogenomic evidence remains limited.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, A.T.A., F.L.I.-C., J.C.E.-R., R.M.C.-M., N.M.V., L.A.Q., J.A.G., M.R.B., H.C., F.S.-L., D.L.-A., P.A.C.-G., E.J.M.-M., B.P.-O., M.B.-H., J.S.A.-G., J.K.-C., R.P.-L. and P.A.-R.; software, F.L.I.-C. and J.C.E.-R.; validation, F.L.I.-C. and R.M.C.-M.; formal analysis, M.B.-H., J.S.A.-G., J.K.-C., R.P.-L. and P.A.-R.; investigation, A.T.A., F.L.I.-C., J.C.E.-R., R.M.C.-M., N.M.V., L.A.Q., J.A.G., M.R.B., H.C., F.S.-L., D.L.-A., P.A.C.-G., E.J.M.-M., B.P.-O., M.B.-H., J.S.A.-G., J.K.-C., R.P.-L. and P.A.-R.; resources, A.T.A.; data curation, J.A.G., M.R.B., E.J.M.-M. and B.P.-O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.A., J.A.G., M.R.B., H.C. and F.S.-L.; writing—review and editing, N.M.V. and L.A.Q.; visualization, D.L.-A. and P.A.C.-G.; supervision, F.L.I.-C.; project administration, E.J.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Research Ethics Committee of the Alberto Sabogal Sologuren National Hospital-ESSALUD in Callao approved the protocol and informed consent for this study as a minimal-risk investigation, using blood samples from routine clinical practice, through Memorandum No. 098-CIEI-OIyD-GRPS-ESSALUD-2023 (Approval date: 13 April 2023). The subjects signed informed consent before participating and were referred to as volunteer patients. Each volunteer was assigned a code to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to the members of the Molecular Pharmacology Society of Peru for their fine contributions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| ADRs | Adverse drug reactions |

| ASMs | Antiseizure medications |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| gDNA | Genomic DNA |

| ILAE | International League Against Epilepsy |

| HNASS | Alberto Sabogal Sologuren National Hospital |

| ESSALUD | Social Health Security |

| 95% CI | 95% confidence intervals |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| DRESS | Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms |

| SJS | Stevens–Johnson syndrome |

| TEN | Toxic epidermal necrolysis |

| IM | Intermediate metabolizers |

| NM | Normal metabolizers |

| PM | Poor metabolizers |

| RM | Rapid metabolizers |

| LEV | Levetiracetam |

| LTG | Lamotrigine |

| PHT | Phenytoin |

| PHB | Phenobarbital |

| VPA | Valproic acid |

References

- Stafstrom, C.E.; Carmant, L. Seizures and epilepsy: An overview for neuroscientists. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a022426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, R.S.; Cross, J.H.; French, J.A.; Higurashi, N.; Hirsch, E.; Jansen, F.E.; Lagae, L.; Moshé, S.L.; Peltola, J.; Roulet Perez, E.; et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazbeck, H.; Youssef, J.; Nasreddine, W.; El Kurdi, A.; Zgheib, N.; Beydoun, A. The role of candidate pharmacogenetic variants in determining valproic acid efficacy, toxicity and concentrations in patients with epilepsy. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1483723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Epilepsy. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/epilepsy (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- McGinn, R.J.; Von Stein, E.L.; Summers Stromberg, J.E.; Li, Y. Precision medicine in epilepsy. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 190, 147–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burneo, J.G.; Tellez-Zenteno, J.; Wiebe, S. Understanding the burden of epilepsy in Latin America: A systematic review of its prevalence and incidence. Epilepsy Res. 2005, 66, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burneo, J.G.; Steven, D.A.; Arango, M.; Zapata, W.; Vasquez, C.M.; Becerra, A. La cirugía de epilepsia y el establecimiento de programas quirúrgicos en el Perú: El proyecto de colaboración entre Perú y Canadá. Rev. Neuropsiquiatr. 2017, 80, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoko, K.B.; van Puijenbroek, E.P.; Bijl, A.H.; Hermens, W.A.; Zwart-van Rijkom, J.E.; Hekster, Y.A.; Egberts, T.C. Influence of chemical structure on hypersensitivity reactions induced by antiepileptic drugs: The role of the aromatic ring. Drug Saf. 2008, 31, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Kim, D.Y.; Bae, E.K.; Kim, D.W. Adverse Skin Reactions with Antiepileptic Drugs Using Korea Adverse Event Reporting System Database, 2008–2017. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, M.B.; Muche, E.A. Patient reported adverse events among epileptic patients taking antiepileptic drugs. SAGE Open Med. 2018, 6, 2050312118772471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Zavaleta, A.I.; Li-Amenero, C.; Bendezú, M.R.; Garcia, J.A.; Chávez, H.; Palomino-Jhong, J.J.; Surco-Laos, F.; Laos-Anchante, D.; Melgar-Merino, E.J.; et al. Role of pharmacogenomics for prevention of hypersensitivity reactions induced by aromatic antiseizure medications. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1640401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgolli, F.; Aouinti, I.; Charfi, O.; Kaabi, W.; Hamza, I.; Daghfous, R.; Kastalli, S.; Lakhoua, G.; Aidli, S.E. Cutaneous adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. Therapie 2024, 79, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asadi-Pooya, A.A.; Rostaminejad, M.; Zeraatpisheh, Z.; Mirzaei Damabi, N. Cosmetic adverse effects of antiseizure medications; A systematic review. Seizure 2021, 91, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moshé, S.L.; Perucca, E.; Ryvlin, P.; Tomson, T. Epilepsy: New advances. Lancet 2015, 385, 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.U.; Ullah, S.; Carr, D.F.; Khattak, M.I.K.; Asad, M.I.; Rehman, M.U.; Tipu, M.K. The association of ABCB1 gene polymorphism with clinical response to carbamazepine monotherapy in patients with epilepsy. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urzì Brancati, V.; Pinto Vraca, T.; Minutoli, L.; Pallio, G. Polymorphisms Affecting the Response to Novel Antiepileptic Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keangpraphun, T.; Towanabut, S.; Chinvarun, Y.; Kijsanayotin, P. Association of ABCB1 C3435T polymorphism with phenobarbital resistance in Thai patients with epilepsy. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2015, 40, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouchi, M.; Kaabachi, W.; Klaa, H.; Tizaoui, K.; Turki, I.B.; Hila, L. Relationship between ABCB1 3435TT genotype and antiepileptic drugs resistance in Epilepsy: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2017, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potschka, H.; Brodie, M.J. Pharmacoresistance. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2012, 108, 741–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, R.; Kumari, R.; Misra, U.K.; Kalita, J.; Pradhan, S.; Mittal, B. Differential role of sodium channels SCN1A and SCN2A gene polymorphisms with epilepsy and multiple drug resistance in the north Indian population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 68, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanzad, M.; Sarhangi, N.; Naghavi, A.; Ghavimehr, E.; Khatami, F.; Ehsani Chimeh, S.; Larijani, B.; Aghaei Meybodi, H.R. Genomic medicine on the frontier of precision medicine. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 2021, 21, 853–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, C.H. Equity in Genomic Medicine. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2022, 23, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisodiya, S.M. Precision medicine and therapies of the future. Epilepsia 2021, 62, S90–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaedigk, A.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Miller, N.A.; Leeder, J.S.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Klein, T.E.; PharmVar Steering Committee. The Pharmacogene Variation (PharmVar) Consortium: Incorporation of the Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Database. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 103, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, Á.T.; Muñoz, A.M.; Loja, B.; Miyasato, J.M.; García, J.A.; Cerro, R.A.; Quiñones, L.A.; Varela, N.M. Study of the allelic variants CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 in samples of the Peruvian mestizo population. [Estudio de las variantes alélicas CYP2C9*2 y CYP2C9*3 en muestras de población mestiza peruana]. Biomedica 2019, 39, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPIC. CPIC® Guideline for Phenytoin and CYP2C9 and HLA-B. 2020. Available online: https://cpicpgx.org/guidelines/guideline-for-phenytoin-and-cyp2c9-and-hla-b (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Karnes, J.H.; Rettie, A.E.; Somogyi, A.A.; Huddart, R.; Fohner, A.E.; Formea, C.M.; Ta Michael Lee, M.; Llerena, A.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Klein, T.E.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for CYP2C9 and HLA-B Genotypes and Phenytoin Dosing: 2020 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, F.; Mangó, K.; Déri, M.; Incze, E.; Minus, A.; Monostory, K. Impact of genetic and non-genetic factors on hepatic CYP2C9 expression and activity in Hungarian subjects. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Stein, C.M.; Hulot, J.S.; Mega, J.L.; Roden, D.M.; Klein, T.E.; Sabatine, M.S.; Johnson, J.A.; Shuldiner, A.R.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 90, 328–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.R.; Luzum, J.A.; Sangkuhl, K.; Gammal, R.S.; Sabatine, M.S.; Stein, C.M.; Kisor, D.F.; Limdi, N.A.; Lee, Y.M.; Scott, S.A.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for CYP2C19 Genotype and Clopidogrel Therapy: 2022 Update. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 112, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruf, A.A.; Greenslade, A.; Arnold, P.D.; Bousman, C. Antidepressant pharmacogenetics in children and young adults: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 254, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skadrić, I.; Stojković, O. Defining screening panel of functional variants of CYP1A1, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4 genes in Serbian population. Int. J. Legal Med. 2020, 134, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannaccone, T.; Sellitto, C.; Manzo, V.; Colucci, F.; Giudice, V.; Stefanelli, B.; Iuliano, A.; Corrivetti, G.; Filippelli, A. Pharmacogenetics of Carbamazepine and Valproate: Focus on Polymorphisms of Drug Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, P.; López-Torres, E.; Peñas-Lledó, E.M.; Martínez-Antón, J.; Llerena, A. Neurological toxicity after phenytoin infusion in a pediatric patient with epilepsy: Influence of CYP2C9, CYP2C19 and ABCB1 genetic polymorphisms. Pharmacogenom. J. 2013, 13, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, L.E.N.; Nijenhuis, M.; Soree, B.; de Boer-Veger, N.J.; Buunk, A.M.; Houwink, E.J.F.; Risselada, A.; Rongen, G.A.P.J.M.; van Schaik, R.H.N.; Swen, J.J.; et al. Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) guideline for the gene-drug interaction of CYP2C9, HLA-A and HLA-B with anti-epileptic drugs. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2024, 32, 903–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staines, A.G.; Coughtrie, M.W.; Burchell, B. N-glucuronidation of carbamazepine in human tissues is mediated by UGT2B7. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 311, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghodke-Puranik, Y.; Thorn, C.F.; Lamba, J.K.; Leeder, J.S.; Song, W.; Birnbaum, A.K.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. Valproic acid pathway: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 2013, 23, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.L.; Haslemo, T.; Refsum, H.; Molden, E. Impact of age, gender and CYP2C9/2C19 genotypes on dose-adjusted steady-state serum concentrations of valproic acid-a large-scale study based on naturalistic therapeutic drug monitoring data. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 72, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Cotuá, J.; Delgado, M.; Morales, A.; Muñoz, A.M.; Li, C.; Bendezú, M.R.; García, J.A.; Laos-Anchante, D.; Surco-Laos, F.; et al. Serum concentrations of valproic acid in people with epilepsy: Clinical implication. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2022, 10, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, M.A.; Feria-Romero, I.A.; Fernando-Serrano, H.; Escalante-Santiago, D.; Grijalva, I.; Orozco-Suarez, S. Genetic polymorphisms associated with antiepileptic metabolism. Front. Biosci. 2014, 6, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, S.; Sisodiya, S.M. Pharmacogenomics in epilepsy. Neurosci. Lett. 2018, 667, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauser, T.A. Biomarkers for antiepileptic drug response. Biomark. Med. 2011, 5, 635–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.N.; Amidon, G.L. A mechanistic approach to understanding the factors affecting drug absorption: A review of fundamentals. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 620–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmer, S.; Rochon, P. Sex and Age Differences in Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. Public Policy Aging Rep. 2023, 33, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spleis, H.; Sandmeier, M.; Claus, V.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Surface design of nanocarriers: Key to more efficient oral drug delivery systems. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2023, 313, 102848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscanoa, T.J.; Guevara-Fujita, M.L.; Fujita, R.M.; Muñoz-Paredes, M.Y.; Oscar Acosta, O.; Romero-Ortuño, R. Association between polymorphisms of the VKORC1 and CYP2C9 genes and warfarin maintenance dose in Peruvian patients. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 90, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Ayala, E.; Chevarría Arriaga, M.; Barbosa Coelho, C.; Sandoval, J.; Salazar Granara, A. Metabolizer phenotype prediction in different Peruvian ethnic groups through CYP2C9 polymorphisms. Drug Metabol. Pers. Ther. 2021, 36, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhan, R.; Kumari, R.; Singh, K.; Kalita, J.; Misra, U.K.; Mittal, B. Possible role of CYP2C9 & CYP2C19 single nucleotide polymorphisms in drug refractory epilepsy. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Makowska, M.; Smolarz, B.; Bryś, M.; Forma, E.; Romanowicz, H. An association between the rs1799853 and rs1057910 polymorphisms of CYP2C9, the rs4244285 polymorphism of CYP2C19 and the prevalence rates of drug-resistant epilepsy in children. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 131, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fohner, A.E.; Rettie, A.E.; Thai, K.K.; Ranatunga, D.K.; Lawson, B.L.; Liu, V.X.; Schaefer, C.A. Associations of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 Pharmacogenetic Variation with Phenytoin-Induced Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2020, 13, 1004–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 51; Song, C.; Li, X.; Mao, P.; Song, W.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. Impact of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9 gene polymorphisms on sodium valproate plasma concentration in patients with epilepsy. Eur. J. Hosp. Pharm. 2022, 29, 198–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Ybañez-Julca, R.; Muñoz, A.M.; Tejada-Bechi, C.; Cerro, R.; Quiñones, L.A.; Varela, N.; Alvarado, C.A.; Alvarado, E.; Bendezú, M.R.; et al. Frequency of CYP2D6*3 and *4 and metabolizer phenotypes in three mestizo Peruvian populations. Pharmacia 2021, 68, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Muñoz, A.M.; Varela, N.; Sullón-Dextre, L.; Pineda, M.; Bolarte-Arteaga, M.; Bendezú, M.R.; García, J.A.; Chávez, H.; Surco-Laos, F.; et al. Pharmacogenetic variants of CYP2C9 and CYP2C19 associated with adverse reactions induced by antiepileptic drugs used in Peru. Pharmacia 2023, 70, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Saravia, M.; Losno, R.; Pariona, R.; María Muñoz, A.; Ybañez-Julca, R.O.; Loja, B.; Bendezú, M.R.; García, J.A.; Surco-Laos, F.; et al. CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 Genes Associated with Tricontinental and Latin American Ancestry of Peruvians. Drug Metab. Bioanal. Lett. 2023, 16, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doré, M.; San Juan, A.E.; Frenette, A.J.; Williamson, D. Clinical Importance of Monitoring Unbound Valproic Acid Concentration in Patients with Hypoalbuminemia. Pharmacotherapy 2017, 37, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaker, S.J.; Gandhe, P.P.; Godbole, C.J.; Bendkhale, S.R.; Mali, N.B.; Thatte, U.M.; Gogtay, N.J. A prospective study to assess the association between genotype, phenotype and Prakriti in individuals on phenytoin monotherapy. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2017, 8, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, A.T.; Muñoz, A.M.; Miyasato, J.M.; Alvarado, E.A.; Loja, B.; Villanueva, L.; Pineda, M.; Bendezú, M.; Palomino-Jhong, J.J.; García, J.A. In Vitro Therapeutic Equivalence of Two Multisource (Generic) Formulations of Sodium Phenytoin (100 mg) Available in Peru. Dissolution Technol. 2020, 27, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijkman, S.C.; Rauwé, W.M.; Danhof, M.; Della Pasqua, O. Pharmacokinetic interactions and dosing rationale for antiepileptic drugs in adults and children. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 84, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosheska, D.; Roškar, R. Simple HPLC-UV Method for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of 12 Antiepileptic Drugs and Their Main Metabolites in Human Plasma. Molecules 2023, 28, 7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.S. Enzyme induction and inhibition by new antiepileptic drugs: A review of human studies. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 14, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratoni, A.J.; Colmerauer, J.L.; Linder, K.E.; Nicolau, D.P.; Kuti, J.L. A Retrospective Case Series of Concomitant Carbapenem and Valproic Acid Use: Are Best Practice Advisories Working? J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 36, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Louis, E.K. Monitoring antiepileptic drugs: A level-headed approach. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009, 7, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perucca, P.; Gilliam, F.G. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Tripathi, M.; Gupta, P.; Gulati, S.; Gupta, Y.K. Adverse effects & drug load of antiepileptic drugs in patients with epilepsy: Monotherapy versus polytherapy. Indian. J. Med. Res. 2017, 145, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, Y.L.; Foster, E.; Lloyd, M.; Rayner, G.; Rychkova, M.; Ali, R.; Carney, P.W.; Velakoulis, D.; Winton-Brown, T.T.; Kalincik, T.; et al. Adverse events related to antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 115, 107657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekele, F.; Mamo, T.; Fekadu, G. Prevalence and associated factors of medication-related problems among epileptic patients at ambulatory clinic of Mettu Karl Comprehensive Specialized Hospital: A cross-sectional study. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayane, Y.B.; Jifar, W.W.; Berhanu, R.D.; Rikitu, D.H. Antiseizure adverse drug reaction and associated factors among epileptic patients at Jimma Medical Center: A prospective observational study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneerot, T.; Saelue, P.; Sangiemchoey, A. Phenytoin-Induced Severe Thrombocytopenia: A Case Report. Cureus 2024, 16, e60669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitaki, B.K.; Minacapelli, C.D.; Zhang, P.; Wachuku, C.; Gupta, K.; Catalano, C.; Rustgi, V. Drug-induced liver injury associated with antiseizure medications from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 117, 107832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakunje, A.; Prabhu, A.; Sindhu Priya, E.S.; Karkal, R.; Kumar, P.; Gupta, N.; Rahyanath, P.K. Valproate: It’s Effects on Hair. Int. J. Trichology 2018, 10, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsini, A.; Esposito, M.; Perna, D.; Bonuccelli, A.; Peroni, D.; Striano, P. Personalized medicine in epilepsy patients. J. Transl. Genet. Genom. 2018, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostory, K.; Nagy, A.; Tóth, K.; Bűdi, T.; Kiss, Á.; Déri, M.; Csukly, G. Relevance of CYP2C9 Function in Valproate Therapy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shnayder, N.A.; Grechkina, V.V.; Khasanova, A.K.; Bochanova, E.N.; Dontceva, E.A.; Petrova, M.M.; Asadullin, A.R.; Shipulin, G.A.; Altynbekov, K.S.; Al-Zamil, M.; et al. Therapeutic and Toxic Effects of Valproic Acid Metabolites. Metabolites 2023, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, V.K.; Supriya; Shree, R.; Prakash, A.; Takkar, A.; Khullar, M.; Saikia, B.; Medhi, B.; Modi, M. Genetic abnormality of cytochrome-P2C9*3 allele predisposes to epilepsy and phenytoin-induced adverse drug reactions: Genotyping findings of cytochrome-alleles in the North Indian population. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 8, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, F.; Manojlovic, M.; Matkovic, L.; Molden, E.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Leucht, S.; Jukic, M.M. Pharmacogenetic Variants and Plasma Concentrations of Antiseizure Drugs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2425593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudio-Campos, K.; Labastida, A.; Ramos, A.; Gaedigk, A.; Renta-Torres, J.; Padilla, D.; Rivera-Miranda, G.; Scott, S.A.; Ruaño, G.; Cadilla, C.L.; et al. Warfarin Anticoagulation Therapy in Caribbean Hispanics of Puerto Rico: A Candidate Gene Association Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.H.; Hung, S.I.; Hong, H.S.; Hsih, M.S.; Yang, L.C.; Ho, H.C.; Wu, J.Y.; Chen, Y.T. Medical genetics: A marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Nature 2004, 428, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, J.Q.; Zhou, L.M.; Chen, Z.Y.; Fang, Z.Y.; Chen, S.D.; Yang, L.B.; Cai, X.D.; Dai, Q.L.; Hong, H.; et al. Association between HLA-B*1502 allele and carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous adverse reactions in Han people of southern China mainland. Seizure 2011, 20, 446–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, V.; Jackson, C.; Cooper, A. Review of Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, E.J.; Sukasem, C.; Whirl-Carrillo, M.; Müller, D.J.; Dunnenberger, H.M.; Chantratita, W.; Goldspiel, B.; Chen, Y.T.; Carleton, B.C.; George, A.L.; et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium Guideline for HLA Genotype and Use of Carbamazepine and Oxcarbazepine: 2017 Update. Clin. Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 103, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).