Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Oral Safety Evaluation of PZ-2891

2.2. Behavioral Experiments of PZ-2891 In Vivo

2.3. Neuroprotective Effects of PZ-2891 In Vitro

2.4. AD Pathology Improvement by PZ-2891 via Upregulation of PANK2 Expression

2.4.1. Pathological Damage Improvement

Neuronal Morphology

Biochemical Pathology

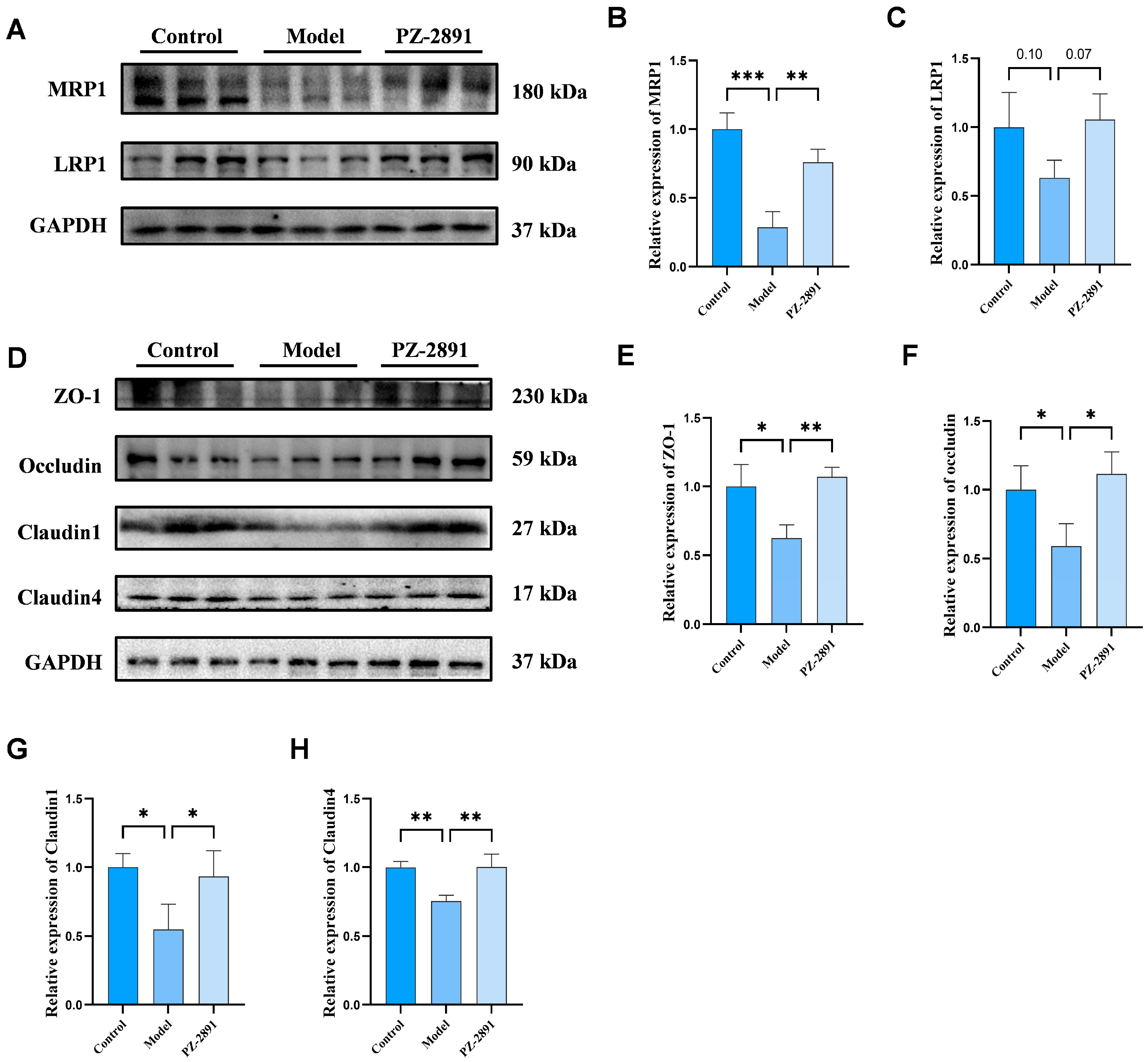

BBB Integrity and Transporter Expression

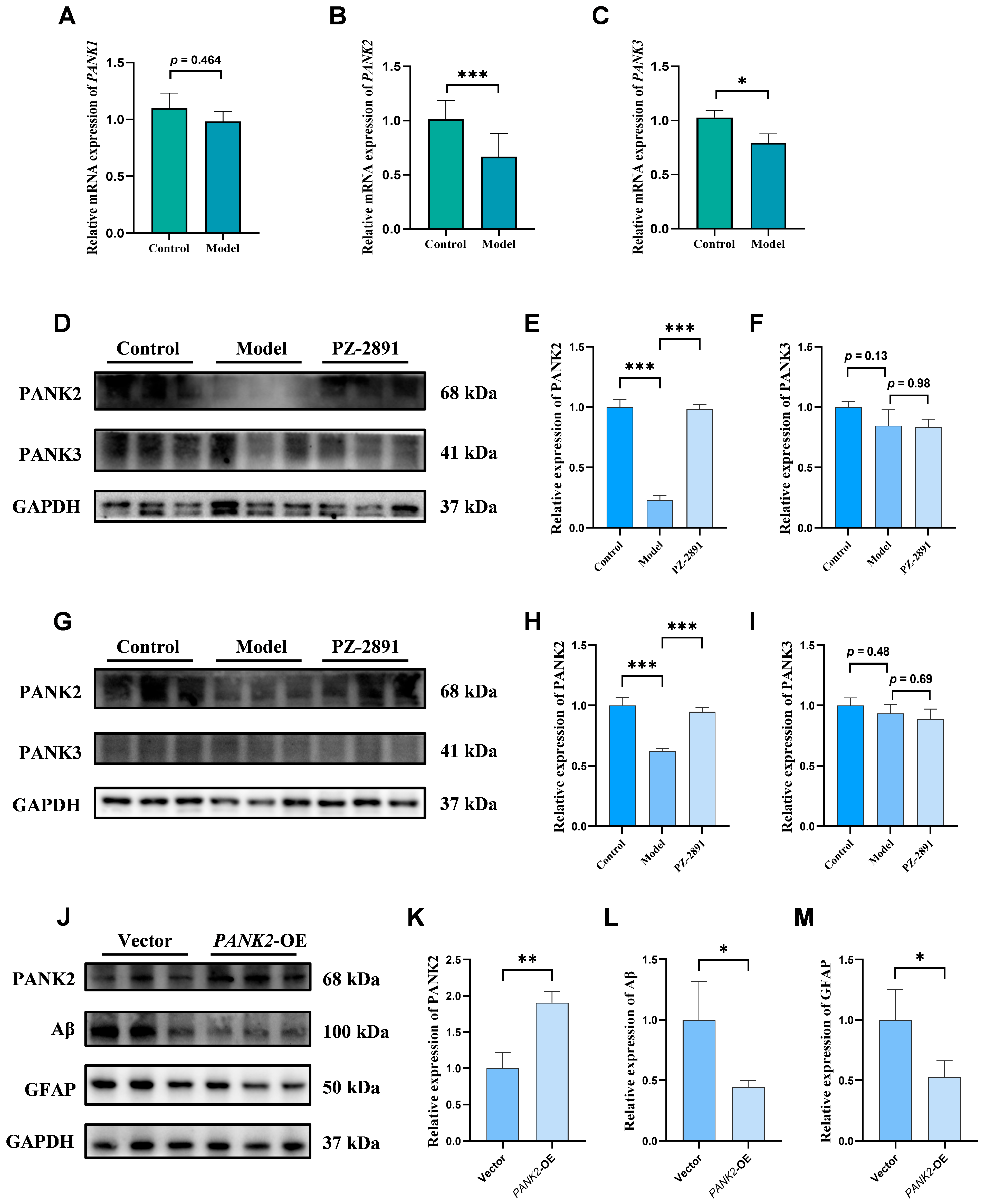

2.4.2. Positive Role of PANK2 in AD

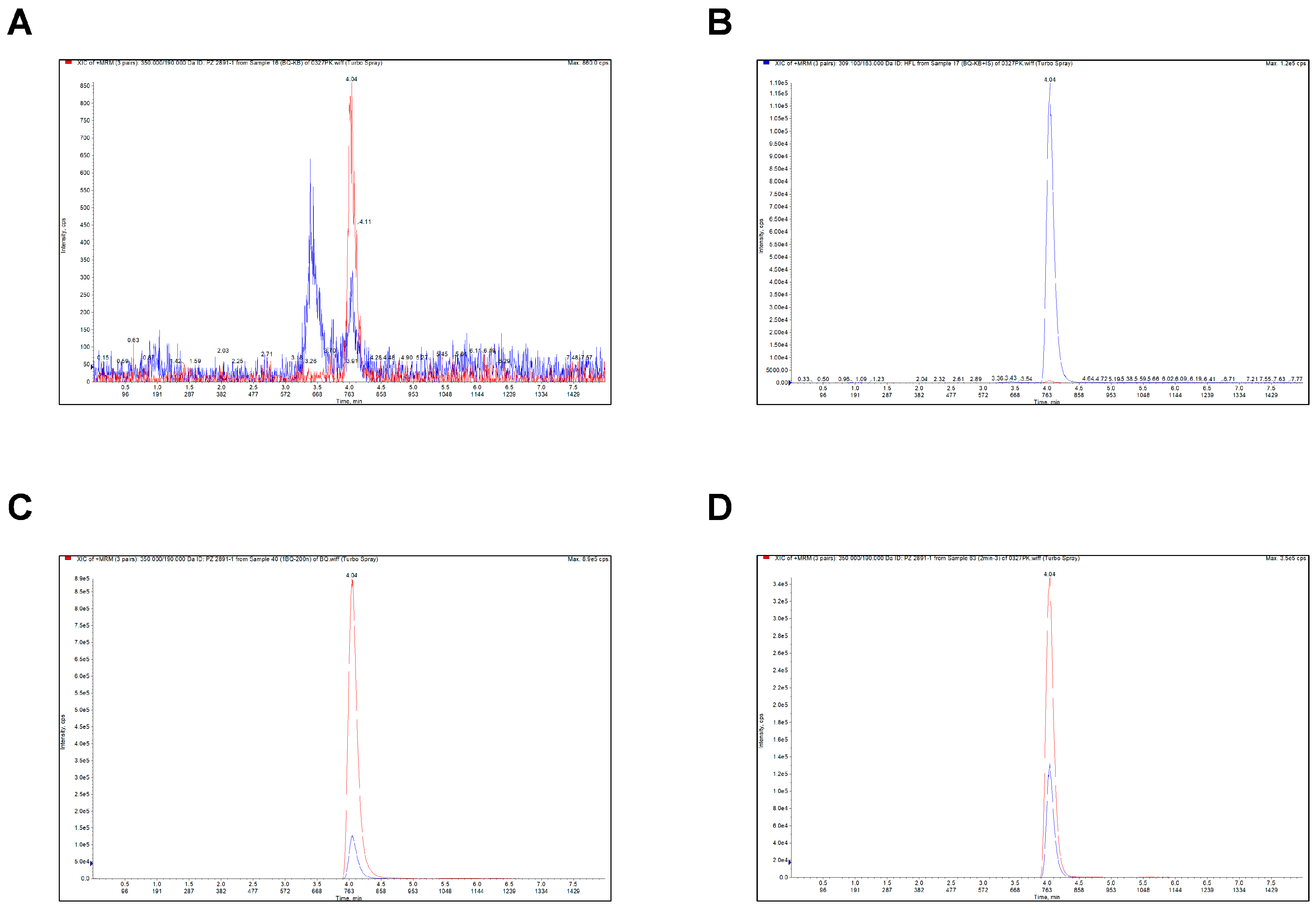

2.5. Analytical Method Validation of PZ-2891

2.5.1. Selectivity

2.5.2. Linearity and Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ)

2.5.3. Precision and Accuracy

2.5.4. Recovery and Matrix Effect

2.5.5. Stability

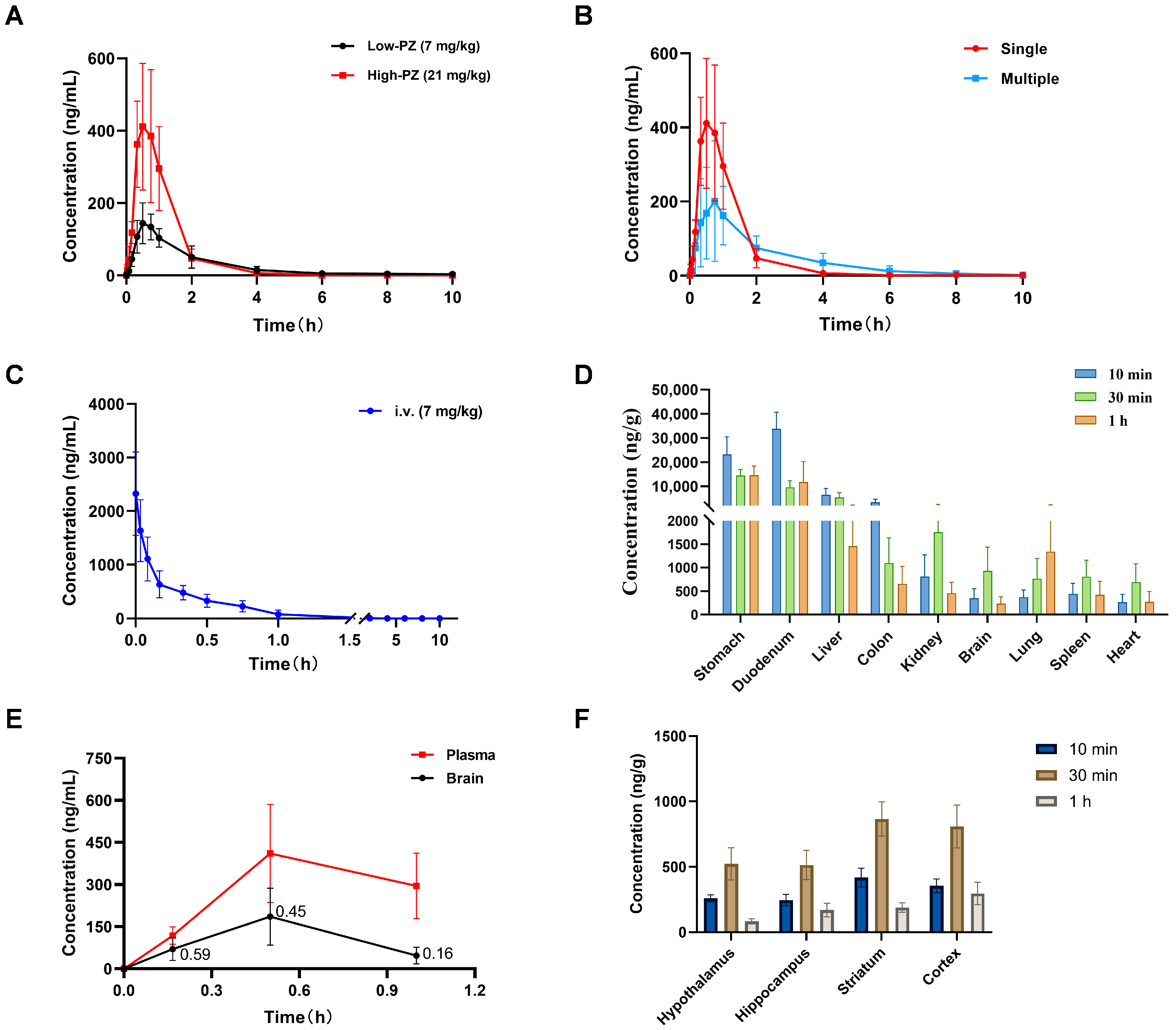

2.6. Blood Concentration–Time Curve of PZ-2891

2.7. Oral Bioavailability Assessment of PZ-2891

2.8. Tissue Distribution of PZ-2891

2.9. BBB Penetration Evaluation of PZ-2891

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

4.2. Animal Model Establishment

4.2.1. Animals

4.2.2. Aβ1-42 Injection

4.3. Behavioral Experiments

4.3.1. Morris Water Maze (MWM)

4.3.2. Open Field Test (OFT)

4.3.3. Novel Object Recognition (NOR)

4.3.4. Y Maze

4.4. Cell Culture and CCK-8 Assay

4.5. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Assay

4.6. Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

4.7. Western Blot (WB) Analysis

4.8. Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) Staining

4.9. Nissl Staining

4.10. Immunofluorescence (IF) Assay

4.11. Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Conditions

4.12. Preparation of Standard Samples

4.13. Method Validation

4.14. Pharmacokinetic (PK) Study

4.15. Preparation of Biological Samples

4.16. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ADI | Alzheimer’s Disease International |

| ARIA-E | amyloid-related imaging abnormalities—edema |

| ARIA-H | amyloid-related imaging abnormalities—hemorrhage |

| Aβ | amyloid-β |

| AUC | area under the concentration–time curve |

| BBB | blood–brain barrier |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| CCK8 | cell counting kit 8 |

| CoA | coenzyme A |

| COX-2 | cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| CRE | creatinine |

| DCF | 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein |

| DCFH-DA | 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium |

| D-gal | D-galactose |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GFI | green fluorescence intensity |

| IFN-γ | interferon-γ |

| IL-1β | interleukin-1β |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IS | internal standard |

| LC–MS/MS | liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LLOQ | lower limit of quantitation |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| LRP1 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 |

| MRM | multiple reaction monitoring |

| MRP1 | multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 |

| MWM | Morris water maze |

| NCA | non-compartmental |

| NOR | novel object recognition |

| OFT | open field test |

| OA | okadaic acid |

| PD | pharmacodynamic |

| PK | pharmacokinetic |

| PKAN | pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration |

| PANK | pantothenate kinase |

| QC | quality control |

| RE | relative deviation |

| SD | Sprague Dawley |

| TJ | tight junction |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-α |

| ZO-1 | zonula occluden-1 |

References

- Heilman, K.M.; Nadeau, S.E. Emotional and Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2022, 19, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Self, W.K.; Holtzman, D.M. Emerging diagnostics and therapeutics for Alzheimer disease. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 2187–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Counts, N.; Chen, S.; Seligman, B.; Tortorice, D.; Vigo, D.; Bloom, D.E. Global and regional projections of the economic burden of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias from 2019 to 2050: A value of statistical life approach. eClinicalMedicine 2022, 51, 101580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, G.S. Amyloid-beta and tau: The trigger and bullet in Alzheimer disease pathogenesis. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 505–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobini, E.; Cuello, A.C.; Fisher, A. Reimagining cholinergic therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2022, 145, 2250–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yin, Y.L.; Liu, X.Z.; Shen, P.; Zheng, Y.G.; Lan, X.R.; Lu, C.B.; Wang, J.Z. Current understanding of metal ions in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanjee, S.; Chakraborty, P.; Bhattacharya, H.; Chacko, L.; Singh, B.; Chaudhary, A.; Javvaji, K.; Pradhan, S.R.; Vallamkondu, J.; Dey, A.; et al. Altered glucose metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease: Role of mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 193, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barritt, S.A.; DuBois-Coyne, S.E.; Dibble, C.C. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: Mechanisms of regulation, function and disease. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iankova, V.; Karin, I.; Klopstock, T.; Schneider, S.A. Emerging Disease-Modifying Therapies in Neurodegeneration With Brain Iron Accumulation (NBIA) Disorders. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 629414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.; Zhang, Y.M.; Rock, C.O.; Jackowski, S. Coenzyme A: Back in action. Prog. Lipid Res. 2005, 44, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.K.; Subramanian, C.; Yun, M.K.; Frank, M.W.; White, S.W.; Rock, C.O.; Lee, R.E.; Jackowski, S. A therapeutic approach to pantothenate kinase associated neurodegeneration. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogarth, P.; Kurian, M.A.; Gregory, A.; Csanyi, B.; Zagustin, T.; Kmiec, T.; Wood, P.; Klucken, A.; Scalise, N.; Sofia, F.; et al. Consensus clinical management guideline for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN). Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017, 120, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, C.; Yao, J.; Frank, M.W.; Rock, C.O.; Jackowski, S. A pantothenate kinase-deficient mouse model reveals a gene expression program associated with brain coenzyme a reduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Patassini, S.; Begley, P.; Church, S.; Waldvogel, H.J.; Faull, R.L.M.; Unwin, R.D.; Cooper, G.J.S. Cerebral deficiency of vitamin B5 (d-pantothenic acid; pantothenate) as a potentially-reversible cause of neurodegeneration and dementia in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 527, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezavar, D.; Bonnen, P.E. Incidence of PKAN determined by bioinformatic and population-based analysis of ~140,000 humans. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2019, 128, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayflick, S.J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Sibon, O.C.M. PKAN pathogenesis and treatment. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022, 137, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attems, J. Alzheimer’s disease pathology in synucleinopathies. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 22–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, C.; Lv, S.; Zhou, B. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration: Insights from a Drosophila model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 3659–3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daroi, P.A.; Dhage, S.N.; Juvekar, A.R. p-Coumaric acid protects against D-galactose induced neurotoxicity by attenuating neuroinflammation and apoptosis in mice brain. Metab. Brain Dis. 2022, 37, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamat, P.K.; Tota, S.; Rai, S.; Shukla, R.; Ali, S.; Najmi, A.K.; Nath, C. Okadaic acid induced neurotoxicity leads to central cholinergic dysfunction in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 690, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Xing, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Feng, F.; Sun, H. p62/SQSTM1, a Central but Unexploited Target: Advances in Its Physiological/Pathogenic Functions and Small Molecular Modulators. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 10135–10157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Benedetto, G.; Burgaletto, C.; Carta, A.R.; Saccone, S.; Lempereur, L.; Mulas, G.; Loreto, C.; Bernardini, R.; Cantarella, G. Beneficial effects of curtailing immune susceptibility in an Alzheimer’s disease model. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Winfree, R.L.; Seto, M.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Dumitrescu, L.C.; Hohman, T.J. Pathologic and clinical correlates of region-specific brain GFAP in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2024, 148, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gennip, A.C.E.; Satizabal, C.L.; Tracy, R.P.; Sigurdsson, S.; Gudnason, V.; Launer, L.J.; van Sloten, T.T. Associations of plasma NfL, GFAP, and t-tau with cerebral small vessel disease and incident dementia: Longitudinal data of the AGES-Reykjavik Study. Geroscience 2024, 46, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballabh, P.; Braun, A.; Nedergaard, M. The blood-brain barrier: An overview: Structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, S.M.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Shokr, M.M.; Kadasah, S.F.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; El-Saber Batiha, G. LRP1 at the crossroads of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s: Divergent roles in alpha-synuclein and amyloid pathology. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 1002, 177830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiese, M.; Stefan, S.M. The A-B-C of small-molecule ABC transport protein modulators: From inhibition to activation-a case study of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (ABCC1). Med. Res. Rev. 2019, 39, 2031–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.H.; Xiong, X.H.; Zhong, Y.M.; Cen, M.F.; Cheng, X.G.; Wang, G.X.; Zang, L.Q.; Wang, S.J. Pharmacokinetics of isochlorgenic acid C in rats by HPLC-MS: Absolute bioavailability and dose proportionality. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.T.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.F.; Xing, S.S.; Lu, X.; Lyu, W.; Xiong, B.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Qu, W.; et al. Discovery of 4-benzylpiperazinequinoline BChE inhibitor that suppresses neuroinflammation for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 272, 116463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loryan, I.; Reichel, A.; Feng, B.; Bundgaard, C.; Shaffer, C.; Kalvass, C.; Bednarczyk, D.; Morrison, D.; Lesuisse, D.; Hoppe, E.; et al. Friden, Unbound Brain-to-Plasma Partition Coefficient, K(p,uu,brain)-a Game Changing Parameter for CNS Drug Discovery and Development. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 1321–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, L.; Rong, H.; Feng, B. Demystifying brain penetration in central nervous system drug discovery: Miniperspective. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabathuler, R. Approaches to transport therapeutic drugs across the blood-brain barrier to treat brain diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xing, S.; Liao, Q.; Xiong, B.; Wang, Y.; Lu, W.; He, S.; Feng, F.; Liu, W.; et al. Highly Potent and Selective Butyrylcholinesterase Inhibitors for Cognitive Improvement and Neuroprotection. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6856–6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Yoon, C.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, E.; Yim, J.H.; Kim, T.K.; Oh, H.; Lee, D.S. The neuroprotective and anti-neuroinflammatory effects of ramalin synthetic derivatives in BV2 and HT22 cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 231, 116654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Regression Equation | R | Linear Range (ng/mL) | LLOQ (n = 5) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Concentration | RSD (%) | RE (%) | ||||

| PZ-2891 | y = 0.0264x + 0.0108 | 0.9987 | 2–1000 | 2.11 | 4.34 | 5.50 |

| Compound Spiked Concentration (ng/mL) | Intra-Day (n = 5) | Inter-Day (n = 5) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Precision (RSD, %) | Accuracy (RE, %) | Measured Concentration (ng/mL) | Precision (RSD, %) | Accuracy (RE, %) | |

| 2 | 2.05 ± 0.16 | 7.99 | 2.50 | 2.04 ± 0.11 | 5.51 | 1.77 |

| 5 | 5.13 ± 0.11 | 2.08 | 2.56 | 5.28 ± 0.17 | 3.31 | 5.51 |

| 500 | 524.40 ± 15.47 | 2.95 | 4.88 | 534.07 ± 18.07 | 3.38 | 6.81 |

| 800 | 809.60 ± 7.80 | 0.96 | 1.20 | 823.13 ± 15.31 | 1.86 | 2.89 |

| Dose (mg/kg) | T1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0–t (ng∙h/mL) | AUC0–∞ (ng∙h/mL) | V/F (L/kg) | CL/F (L/h/kg) | MRT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 1.56 ± 0.23 | 0.63 ± 0.14 | 149.43 ± 53.29 | 284.41 ± 107.98 | 288.24 ± 109.16 | 61.96 ± 25.27 | 27.45 ± 10.35 | 2.00 ± 0.26 |

| 21 | 0.94 ± 0.23 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 454.50 ± 151.35 | 536.10 ± 184.01 | 536.60 ± 184.02 | 55.10 ± 29.04 | 44.24 ± 19.32 | 1.05 ± 0.23 |

| i.g. (Days) | T1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0–t (ng∙h/mL) | AUC0–∞ (ng∙h/mL) | V/F (L/kg) | CL/F (L/h/kg) | MRT (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.94 ± 0.23 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 454.50 ± 151.35 | 536.10 ± 184.01 | 536.60 ± 184.02 | 55.10 ± 29.04 | 44.24 ± 19.32 | 1.05 ± 0.23 |

| 7 | 1.05 ± 0.34 | 0.80 ± 0.21 | 208.58 ± 160.05 | 437.60 ± 167.23 | 439.99 ± 168.25 | 409.48 ± 323.92 | 218.04 ± 128.00 | 2.17 ± 0.91 |

| Route | Dose (mg/kg) | T1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng/mL) | AUC0–t (ng∙h/mL) | V/F (L/kg) | CL/F (L/h/kg) | Oral Bioavailability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i.g. | 21 | 0.94 ± 0.23 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 454.50 ± 151.35 | 536.10 ± 184.01 | 55.10 ± 29.04 | 44.24 ± 19.32 | 19.74 ± 6.78 |

| i.v. | 7 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 0.03 ± 0.00 | 2323.33 ± 777.81 | 905.32 ± 222.80 | 4.19 ± 3.51 | 5.77 ± 5.07 |

| Reagents | Catalog Numbers | Purity | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin | 13566 | >98% | Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA |

| Acetonitrile | 34888 | >99.9% | Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany |

| Methanol | 34860 | >99.9% | Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany |

| Formic acid | 28905 | >99% | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA |

| PZ-2891 | HY-124634 | 99.68% | Med Chem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA |

| DMEM | D0822 | - | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| FBS | 12103C | - | Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA |

| Amyloid β Peptide | P9001 | >95% | Beyotime, Shanghai, China |

| RIPA lysis buffer | P0013E | - | Beyotime, Shanghai, China |

| Cell Counting Kit-8 | C0039 | - | Beyotime, Shanghai, China |

| ALT | C009-2-1 | - | Jiancheng, Nanjing, China |

| AST | C010-2-1 | - | Jiancheng, Nanjing, China |

| BUN | C013-1-1 | - | Jiancheng, Nanjing, China |

| CRE | C011-2-1 | - | Jiancheng, Nanjing, China |

| Instrument Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| LC | Chromatographic column | ZORBAX Eclipse PlusC18 (2.1 × 50 mm 3.5-Micron) |

| Injection volume | 5 μL | |

| Column temperature | 40 °C | |

| Flow rate | 0.15 mL/min | |

| Mobile phase | (A) 0.1% formic acid in water + 5 mM ammonium formate; (B) Acetonitrile | |

| MS/MS | MRM transition, m/z | 350 → 190 |

| Declustering potential, V | 16 | |

| Entrance potential, V | 10 | |

| Collision energy, V | 25 | |

| Collision cell exit potential, V | 10 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; Jin, M.; Zhang, S.; Qu, S.; Wang, G.; Aa, J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121871

Chen Y, Ma H, Jin M, Zhang S, Qu S, Wang G, Aa J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121871

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Ying, Huimin Ma, Mengyao Jin, Shize Zhang, Shimeng Qu, Guangji Wang, and Jiye Aa. 2025. "Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121871

APA StyleChen, Y., Ma, H., Jin, M., Zhang, S., Qu, S., Wang, G., & Aa, J. (2025). Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of PZ-2891, an Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agonist of PANK2. Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1871. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121871