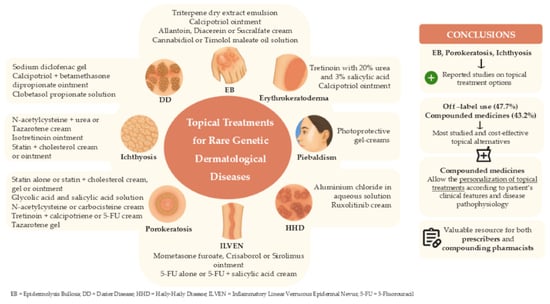

Topical Treatments for Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Epidermolysis Bullosa

1.2. Hailey–Hailey Disease

1.3. Darier Disease

1.4. Congenital Ichthyosis

1.5. Erythrokeratodermias

1.6. Porokeratosis

1.7. Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus

1.8. Piebaldism

1.9. Topical Treatment of Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases

2. Results

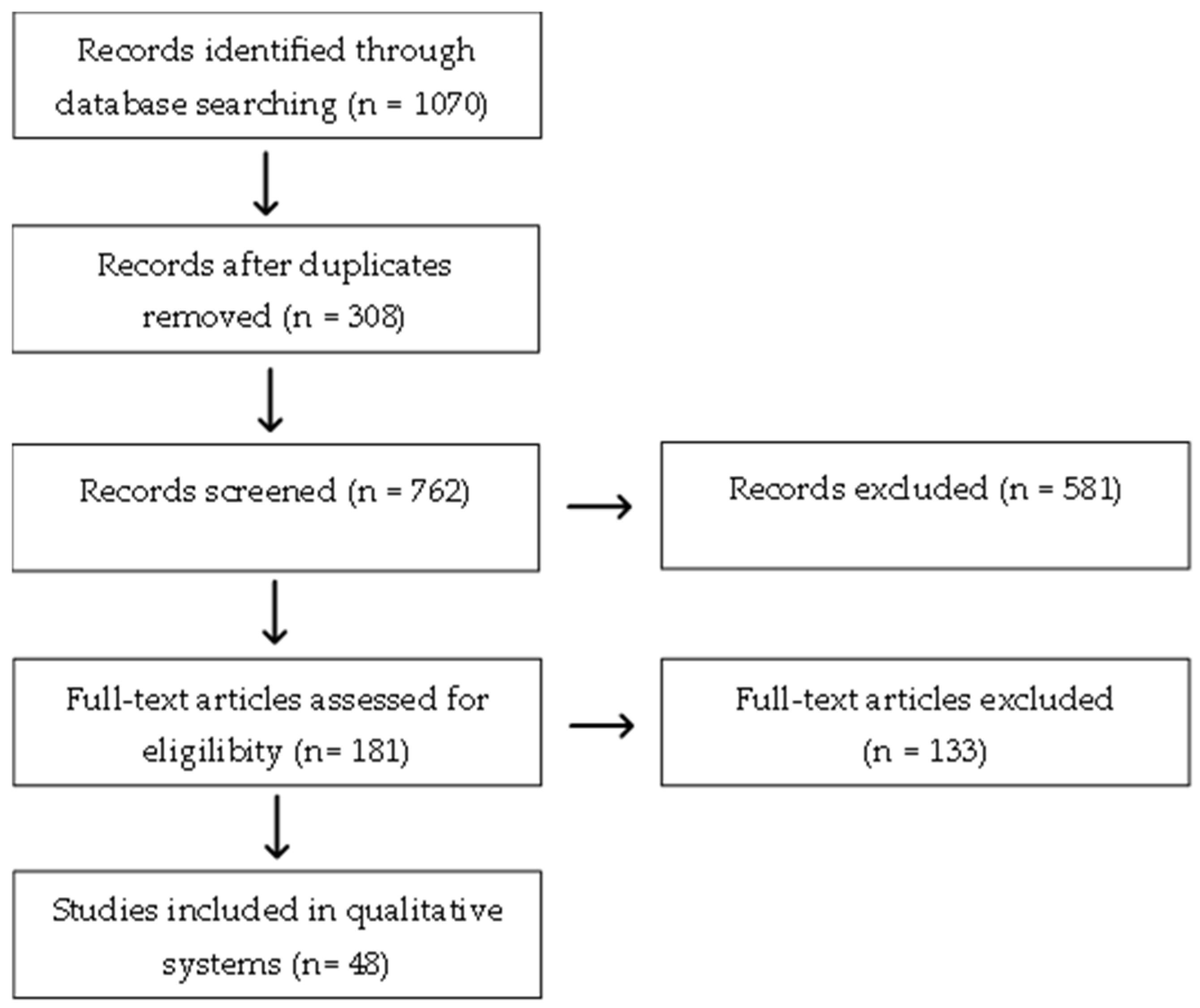

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Topical Treatment of Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB)

| Study | Treatment | Drug Concentration (w/w%) | Pharmaceutical Form | Posology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schwieger-Briel et al. [64] Kern et al. [65] Murell et al. [66] | Commercial medicine (Filsuvez®) | 10% of the triterpene dry extract from Betulae bark (birch bark) | Oleogel | The medicine was applied every 24 to 48 h for 14 days [64], applied once every 4 days for 45 days [65] or 24 months [66]. | Trend toward faster wound epithelialization with Oleogel-S10 versus the vehicle in DEB patients, with good tolerability and patient-reported efficacy * [64]; Significant improvement of wound closure rates by day 45 compared to control gel, mainly in patients with recessive dystrophic EB; AE’s: mostly mild/moderate; one serious AE Oleogel-S10 related [65]; Sustained statistically significant reduction in wound burden over 24 months [66] |

| Paller at al. [71] | Investigational medicine (SD-101) | 6% Allantoin | Cream | Cream was applied once a day for 3 months | No difference between SD-101 and vehicle for complete wound closure or time to closure; trend toward faster closure in children 2–< 12 years and wounds ≥ 5%; well tolerated [71]. |

| Guttmann-Gruber et al. [75] | Compounded medicine (Psorcutan® or Daivonex® dilution in Ultraphil® base) | 0.0005% Calcipotriol | Ointment | Daily topical application for 4 weeks | Significant wound area (day 14) and pruritus (day 14/28) reduction versus placebo; no drug-related AEs or serum calcium changes; Improved wound microbiome *. |

| Wally et al. [78] | Investigational medicine (AC-203) | 1% Diacerein | Cream | Once daily for 4 weeks | Statistically significant reduction in blister number versus placebo; significant absolute blister reduction after follow-up; no AEs. |

| Chelliah et al. [82] | Commercial medicine | Canabidiol | Oil solution | Two or three times per day | Fewer blisters and faster healing of active blisters; no self or family-reported AEs from topical CBD ** |

| Yasar et al. [87] | Compounded medicine | 10% Sucralfate | Cream | Once a day for 2 weeks | On day 10, improved lesions on the genitalia and lower extremities) ** |

| Chiaverini et al. [89] | Commercial medicine (Timoglau ®) | 0.5% Timolol maleate | Solution | One droplet, 2–3 times daily, for 3 weeks | After 3–8 weeks twice daily application of 0.5% timolol maleate eye drops led weeks 100% and 80% wound healing in patients 1 and 2, respectively ** |

2.3. Topical Treatment of Hailey–Hailey Disease (HHD)

2.4. Topical Treatment of Darier Disease

| Study | Treatment | Drug Concentration (w/w%) | Pharmaceutical Form | Posology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campos et al. [98]; Santos-Alarcon et al. [99]; Millán-Parrilla et al. [100] | Commercial medicine (Solaraze®) | 3% sodium diclofenac and 2.5% hyaluronic acid | Gel | Twice daily for 8 weeks [98] Once daily for 6 months [99] Twice a day for 3 (patient 1) and 5 (patient 2) months, respectively [90] | After 4 months, lesion regression with residual macules and few keratotic papules was observed (photographic records), which maintained after discontinuation ** [98]; After six months, hyperkeratotic papules were flattened without local AEs ** [99]; After treatment’s duration, DD lesions were resolved, with only patient 2 reporting irritation on the neck after application ** [100]. |

| Hagino et al. [101] | Commercial medicine (Dovobet®) | 0.005% calcipotriol and 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate | Ointment | Once a day for 3 months | After three months, there was a reduction in redness and scalp scaling, with flattened papules on the neck and groin; only mild remaining pigmentation. |

| Michelle et al. [102] | Commercial medicine | 0.005% Clobetasol propionate; 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate; 1% metronidazole | Solution, ointment and gel, respectively | Once daily for 2 months | Topical metronidazole 1% gel was well tolerated and with no AEs reported. It resolved malodor within 2 months despite persistent lesions; malodor recurred if treatment was stopped **. |

2.5. Topical Treatment for Congenital Ichthyosis

| Study | Treatment | Drug Concentration (w/w%) | Pharmaceutical Form | Posology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paller et al. [105] | Investigational medicine (PAT-001) | 0.1% isotretinoin | Ointment | Twice a day for 8 weeks | 0.1% isotretinoin was more effective, than 0.2%, with mild and transient local AEs * |

| Craiglow et al. [106] | Commercial medicine (TazareneTM) | 0.1% tazarotene | Cream | Once a day for 2 weeks | Rapid improvement of ocular discomfort and the degree of ectropion, without reported AEs ** |

| Bajawi et al. [115] | Compounded medicine | 2% simvastatin | Ointment | Twice a day for 2 weeks After 6 weeks, one application per day | Improvement of skin lesions, hyperkeratosis, erythema and scaling reduction in neonate with CHILD syndrome, after 2 weeks and a complete resolution after 6 weeks ** |

| Yu et al. [116] | 2% simvastatin and 2% cholesterol | Cream | Twice a day for 2 months | Improvement of skin lesions, hyperkeratotic plaques disappearance, normalization of skin texture and local inflammation reduction ** | |

| Sandoval et al. [117] | 2% lovastatin –and 2% cholesterol | Cream | Three applications per week for 8 weeks. | Improvement of skin lesions, scaling, erythema and inflammation reduction, with skin texture normalization ** | |

| Khalil et al. [120] | Glycolic acid—10–20% 2% Lovastatin and 2% cholesterol | Creams | Twice a day for 3 months | Improvement of skin lesions, hyperkeratosis and erythema reduction. An average reduction of 57.5% in disease severity, after 3 months * | |

| Bergqvist et al. [121] | 2% cholesterol and 2% lovastatin; 12% glycolic acid | Creams | Twice a day for 4 weeks | Improvement of skin lesions, hyperkeratosis, erythema and scaling reduction ** | |

| Kaplan et al. [110] | 5 to 10% N-acetylcysteine | Cream | No data available | Improvement of hyperkeratotic lesions, with scaling and skin stiffness reduction. Mild irritation and local erythema appeared in some patients ** | |

| Davila-Seijo et al. [112] | 10% N-acetylcysteine and 10% urea | Cream | Twice a day for 6 weeks | Hyperkeratosis, scaling and skin thickening reduction, in a LI patient ** | |

| González-Freire et al. [113] | 10% Carbocisteine and 5% urea | Cream | No data available | Skin texture and hydration improvement, with good tolerability and no AEs reported ** |

2.6. Topical Treatment for Erythrokeratoderma

2.7. Topical Treatment for Porokeratosis

| Study | Treatment | Drug Concentration (w/w%) | Pharmaceutical Form | Posology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Lucia et al. [129] Chen et al. [131] Atzmony et al. [119] | Compounded medicines | 2% lovastatin and 2% cholesterol Cream | Cream | Once or twice a day for 3 months [129] Twice a day for 4 weeks [131] Twice a day for 3 months [119] | In DSAP reduced clinical severity and inflammation [129]; In linear and disseminated PK reduced the number and size of lesions [131]; In palmar and plantar PK decreased thickness [119] ** |

| Wozna et al. [51] Diep et al. [130] Ugwu et al. [133] | 2% lovastatin and 2% cholesterol | Ointment | 9 months [51] Twice a day for 3 months [130] Twice a day for 6 weeks [133] | Plaque size and scaling reduced [51,130,133]; Progressive reduction in diameter and esthetic improvement of refractory Mibelli-type lesions [51]; Complete resolution of lesions [133]. Effective and sustained response in linear PK, with no recurrence [130,133] ** | |

| Sultan et al. [132] | 2% lovastatin and 2% cholesterol | Gel | Once a day for 2 months | Reduction in hyperkeratosis, erythema and scaling in patients with linear Porokeratosis, DPSA and disseminated palmar and plantar PK. No local and systemic AEs were observed ** | |

| Raison-Peyron et al. [134] | 2% simvastatin and 2% cholesterol | Cream | Twice a day for 2 months | Reduction in skin lesion thickness, erythema and scaling, in a patient with linear PK ** | |

| Severson et al. [124] | Commercial medicine (Ketrel® and Daivonex®) | 0.05% tretinoin. 0.005% calcipotriene | Cream | Applications at night, once every 2 days, for 6 months | Reduction in number and size of DSAP lesions and enhancement of skin texture ** |

| Portelli et al. [127] | Commercial medicine (Efudix®) | 5% of 5-FU | Cream | 30 mg daily for 7 weeks | Total resolution and no lesions recurrence in patients with irregular PK plaque. Mild and transient AEs were reported ** |

| Yeh et al. [128] | Compounded medicine | 5% of 5-FU and 0.005% of calcipotriene | Cream | Twice a day for 5 days | Complete clearance of the lesions, with no recurrence observed for 28 months ** |

| Lang et al. [126] | Compounded medicine | 50% glycolic acid and 25% salicylic acid | Solution | Three peeling cycles repeated every 6 weeks | Reduction in the number and size of DSAP lesions in five patients, after 3 peeling sessions, with skin texture and pigmentation improvement and low AEs ** |

| Alomran & Kanitakis [125] | Commercial medicine (TazareneTM) | 0.1% tazarotene | Gel | Daily application for 1 month | Reduction in skin lesion thickness and scaling in a PK eccrine ostial and dermal duct nervus case, with mild local irritation ** |

2.8. Topical Treatment of Inflammatory Linear Verrucous Epidermal Nevus

| Study | Treatment | Drug Concentrations (w/w%) | Pharmaceutical Form | Posology | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bien et al. [135] | Commercial medicine (Actikerall®) | 0.5% 5-FU 10% salicylic acid | Solution | Once a day for 8 weeks | Partial improvement of erythema and scaling, but less effective than cryosurgery in patients with severe ILVEN ** |

| Al Abadie et al. [143] | Commercial medicine (Efflurak®) | 5% 5-FU | Cream | Once daily for one week per month in pulsed cycles for 3 months | ILVEN lesions improved from 80% to 90%. Reduction in erythema, scaling and pruritus, with no recurrence ** |

| Wollina et al. [137] | Commercial medicine (Elocon®) | 0.1% mometasone furoate | Ointment | Once daily for 8 weeks | Under occlusion, resulted in erythema and scaling reduction, and almost complete lesion resolution, with no recurrence ** |

| Zemero et al. [139] | No data available | Hydrocortisone–Desonide– Clobetasol propionate; 3% salicylic acid; 5% dexpanthenol | No data available | No data available | Reduction in keratosis, inflammation and pruritus, in patients with ILVEN ** |

| Barney at al. [144] | Commercial medicine (Staquis®) | 2% crisaborol | Ointment | Twice a day for 2 months | Plaques progressively improved, erythema reduction, flattening, and pruritus resolution, without AEs reported ** |

| Patel et al. [145] | Commercial medicine (Hyftor®) | 0.2% sirolimus | Ointment | Twice a day for 3 weeks | Reduction in pruritus and skin lesion, with tolerability. ** |

2.9. Topical Treatment for Piebaldism

3. Discussion

4. Methods

4.1. Search Strategy

4.2. Eligibility Criteria

4.3. Quality Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| ARCI | Autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CHILD Syndrome | Congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects syndrome |

| DD | Darier disease |

| DSAP | Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis |

| EB | Epidermolysis bullosa |

| EKV | Erythrokeratoderma Variabilis |

| FDPS | Farnesyl diphosphate synthase |

| FLG | Filaggrin |

| HI | Harlequin ichthyosis |

| HHD | Hailey–Hailey disease |

| HMG CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A |

| IV | Ichthyosis vulgaris |

| ILVEN | Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus |

| LI | Lamellar ichthyosis |

| IL | Interleukin |

| MVD | Mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase |

| MVK | Mevalonate kinase |

| PMKV | Phosphomevalonate kinase |

| PSEK | Progressive Symmetrical Erythrokeratoderma |

| RCTs | Randomized controlled trials |

| SC | Stratum corneum |

| STS | Steroid sulfatase |

| TEWL | Transepidermal water loss |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| XLRI | Recessive X-Linked ichthyosis |

References

- Ministério da Saúde, Brasil. Portaria n. 199 de 30 de Janeiro de 2014: Institui a Política Nacional de Atenção Integral às Pessoas com Doenças Raras; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, DF, Brasil, 2014.

- Ministério da Saúde, Brasil. Doenças Raras. Conhecer, Acolher e Cuidar. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/composicao/saes/doencas-raras (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Diniz, M.F.F.M. Órfãs de medicamentos: Doenças raras. Rev. Apmed. 2023, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L.G.; da Silva, M.R.S.; Demontigny, F. Necessidades prioritárias referidas pelas famílias de pessoas com doenças raras. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2016, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, T.-C.; Wang, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-K.; Chang, C.-I.; Chang, C.-Y.; Tseng, Y.J. RSDB: A rare skin disease database to link drugs with potential drug targets for rare skin diseases. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournier, H.; Calcagni, N.; Morice-Picard, F.; Quintard, B. Psychosocial implications of rare genetic skin diseases affecting appearance on daily life experiences, emotional state, self-perception and quality of life in adults: A systematic review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2023, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danescu, S.; Negrutiu, M.; Has, C. Treatment of epidermolysis bullosa and future directions: A review. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 2059–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, L.G.; Giurcaneanu, C.; Zaharia, F.; Grigoras, A.; Oprea, A.D.; Beiu, C. Dupilumab, a potential novel treatment for hailey–hailey disease. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettinger, M.; Kimeswenger, S.; Deli, I.; Traxler, J.; Altrichter, S.; Noack, P.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Guenova, E.; Hoetzenecker, W. Darier disease: Current insights and challenges in pathogenesis and management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2025, 39, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Paller, A.S.; Dreyfus, I.; Sprecher, E.; O’Toole, E.; Bodemer, C.; Akiyama, M.; Diociaiuti, A.; El Hachem, M.; Fischer, J.; et al. Management of congenital ichthyoses: Guidelines of care. Part one: 2024 update. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 193, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- España, N.T.M.; Carranza, M.C.; Segura, C.B. Erythrokeratodermia variabilis et progressiva: Clinical features, molecular insights, and therapeutic perspectives. Int. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 2666–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos-Kanitakis, K.; Kanitakis, J. Porokeratoses: An update on pathogenesis and treatment. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, W.R. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: A paradigm of progress. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 90, 1159–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qiu, C.; Liu, X. Novel germline KIT variants in families with severe piebaldism: Case series and literature review. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2024, 38, e25073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner, A.L.; Losow, M.; Wisk, J.; Patel, N.; Reha, A.; Lagast, H.; Gault, J.; Gershkowitz, J.; Kopelan, B.; Hund, M.; et al. The challenges of living with and managing epidermolysis bullosa: Insights from patients and caregivers. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.C.; Paula, C.D.; Tauil, P.L.; Costa, I.M. Correlation between nutritional, hematological and infectious characteristics and classification of the type of epidermolysis bullosa of patients assisted at the Dermatology Clinic of the Hospital Universitário de Brasília. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2015, 90, 922–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulombe, P.A.; Kerns, M.L.; Fuchs, E. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex: A paradigm for disorders of tissue fragility. J. Clin. Investig. 2009, 119, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banky, J.P.; Robinson, A.J.; Burge, S.M. Successful treatment of epidermolysis bullosa pruriginosa with topical tacrolimus. Arch. Dermatol. 2004, 140, 794–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Järvikallio, A.; Pulkkinen, L.; Uitto, J. Molecular basis of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: Mutations in the type VII collagen gene (COL7A1). Hum. Mutat. 1997, 10, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardhan, A.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Chapple, I.L.; Fine, J.D.; Harper, N.; Has, C.; Magin, T.M.; Marinkovich, M.P.; Marshall, J.F.; McGrath, J.A.; et al. Epidermolysis bullosa. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritsi, D.; Garcia, M.; Brander, R.; Has, C.; Meijer, R.; Escámez, M.J.; Kohlhase, J.; Akker, P.C.v.D.; Scheffer, H.; Jonkman, M.F.; et al. Mechanisms of natural gene therapy in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 2097–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, A.; Nystrom, A.; Bruckner-Tuderman, L. Raising awareness among healthcare providers about epidermolysis bullosa and advancing toward a cure. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol. 2017, 10, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, M.; Paudel, S.; Bhattarai, N.; Karki, S.; Regmi, S. Hailey-Hailey Disease: An Updated Review with a Focus on Therapeutic Mechanisms. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e71061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maatouk, I.; Rekik, R.; Ghariani, N.; Masmoudi, A.; Bouassida, S.; Mebazaa, A. Hailey–Hailey disease: An update. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Curman, P.; Jebril, W.; Larsson, H.; Bachar-Wikstrom, E.; Cederlöf, M.; Wikstrom, J.D. Darier disease is associated with neurodegenerative disorders and epilepsy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oji, V.; Tadini, G.; Akiyama, M.; Bardon, C.B.; Bodemer, C.; Bourrat, E.; Coudiere, P.; DiGiovanna, J.J.; Elias, P.; Fischer, J.; et al. Revised nomenclature and classification of inherited ichthyoses: Results of the First Ichthyosis Consensus Conference in Sorèze 2009. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 63, 607–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuth, M.; Martinz, V.; Janecke, A.R.; Fauth, C.; Schossig, A.; Zschocke, J.; Gruber, R. Inherited ichthyoses/generalized Mendelian disorders of cornification. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeichi, T.; Akiyama, M. Inherited ichthyosis: Non-syndromic forms. J. Dermatol. 2016, 43, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyssen, J.; Godoy-Gijon, E.; Elias, P. Ichthyosis vulgaris: The filaggrin mutation disease. Br. J. Dermatol. 2013, 168, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengot-Carbo, M.; Hernández-Martín, Á.; Torrelo, A. The role of filaggrin in the skin barrier and disease development. Actas Dermo-Sifiliogr. 2015, 106, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, H.; Shakir, Z.; Kumar, G.; Ali, I.F. Ichthyosis vulgaris: An updated review. Ski. Health Dis. 2022, 3, e187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingordo, V.; D’aNdria, G.; Gentile, C.; Decuzzi, M.; Mascia, E.; Naldi, L. Frequency of X-linked ichthyosis in coastal southern Italy: A study on a representative sample of a young male population. Dermatology 2003, 207, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martín, A.; González-Sarmiento, R.; de Unamuno, P. X-linked ichthyosis: An update. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999, 141, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaca, A.L.; Valdes-Flores, M.; del Refugio Rivera-Vega, M.; González-Huerta, L.M.; Kofman-Alfaro, S.H.; Cuevas-Covarrubias, S.A. Deletion pattern of the STS gene in X-linked ichthyosis in a Mexican population. Mol. Med. 2001, 7, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martín, A.; Garcia-Doval, I.; Aranegui, B.; de Unamuno, P.; Rodríguez-Pazos, L.; González-Enseñat, M.-A.; Vicente, A.; Martín-Santiago, A.; Garcia-Bravo, B.; Feito, M.; et al. Prevalence of autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis: A population-based study using the capture-recapture method in Spain. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, J.; Samuelov, L.; Malchin, N.; Rabinowitz, T.; Assaf, S.; Malki, L.; Malovitski, K.; Israeli, S.; Grafi-Cohen, M.; Bitterman-Deutsch, O.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of non-syndromic autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis in a Middle-Eastern population. Exp. Dermatol. 2021, 30, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Corona, S.I.; Gutiérrez-Ruiz, S.C.; Echeverria, M.D.; Cortés, H.; González-Del Carmen, M.; Leyva-Gómez, G. Advances in the treatment of autosomal recessive congenital ichthyosis: A look towards the repositioning of drugs. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1274248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Martin, A.; Armengot-Carbó, M.; Torrelo, A. A systematic review of clinical trials of treatments for the congenital ichthyoses, excluding ichthyosis vulgaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 69, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, P.L.; Brito, M.C.; Pedrini, I.M.; Sousa, D.C.; Quintanilha, D.O.; Santino, M.F.F.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Villalba, R.C.; Sias, S.M.A. Ictiose lamelar: Relato de caso. Rev. Pediatr. SOPERJ 2016, 16, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Soufi, G.; Gaied, M.M.; Barbour, B. Severe bilateral ectropion. J. Fr. Ophtalmol. 2012, 36, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckert, R.L.; Sturniolo, M.T.; Broome, A.M.; Ruse, M.; Rorke, E.A. Transglutaminase function in epidermis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2005, 124, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotz, A.; Fölster-Holst, R.; Oji, V.; Bourrat, E.; Frank, J.; Marrakchi, S.; Ennouri, M.; Wankner, L.; Komlosi, K.; Alter, S.; et al. Erythrokeratodermia variabilis-like phenotype in patients carrying ABCA12 mutations. Genes 2024, 15, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida-Yamamoto, A.; McGrath, J.A.; Lam, H.; Iizuka, H.; Friedman, R.A.; Christiano, A.M. The molecular pathology of progressive symmetric erythrokeratoderma: A frameshift mutation in the loricrin gene and perturbations in the cornified cell envelope. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997, 61, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suga, Y.; Jarnik, M.; Attar, P.S.; Longley, M.A.; Bundman, D.; Steven, A.C.; Koch, P.J.; Roop, D.R. Transgenic mice expressing a mutant form of loricrin reveal the molecular basis of the skin diseases, vohwinkel syndrome and progressive symmetric erythrokeratoderma. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucaciu, S.A.; Laird, D.W. The genetic and molecular basis of a connexin-linked skin disease. Biochem. J. 2024, 481, 1639–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietkiewicz, P.; Korecka, K.; Salwowska, N.; Kohut, I.; Adhikari, A.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Pogorzelska-Antkowiak, A.; Navarrete-Dechent, C. Porokeratoses—A comprehensive review on the genetics and metabolomics, imaging methods and management of common clinical variants. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmony, L.; Khan, H.M.; Lim, Y.H.; Paller, A.S.; Levinsohn, J.L.; Holland, K.E.; Mirza, F.N.; Yin, E.; Ko, C.J.; Leventhal, J.S.; et al. Second-hit, postzygotic PMVK and MVD mutations in linear porokeratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2019, 155, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Tian, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, X.; Xia, K.; Hu, Z.; Xiong, Z.; Tan, J. Novel mutations in mevalonate kinase cause disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2019, 181, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Min, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, N.; Yang, Z.; Qian, Q. Effects of mevalonate kinase interference on cell differentiation, apoptosis, prenylation and geranylgeranylation of human keratinocytes are attenuated by farnesyl pyrophosphate or geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 2861–2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S.M.; Pontillo, A. The genetics behind inflammasome regulation. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 145, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźna, J.; Korecka, K.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Jałowska, M. Porokeratosis of Mibelli treated with topical 2% Lovastatin/2% cholesterol ointment. Cureus 2024, 16, e65871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazereeuw-Hautier, J.; Marty, C.; Bonafé, J.-L. Familial inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal naevus in a father and daughter. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 33, 679–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, F.; Ghosh, A.; Surana, T.V.; Biswas, S.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Chatterjee, G. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus in perineum and vulva: A report of two rare cases. Indian J. Dermatol. 2013, 58, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanita, K.; Fujimura, T.; Sato, Y.; Lyu, C.; Aiba, S. Widely spread unilateral inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus (ILVEN). Case Rep. Dermatol. 2018, 10, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushal, A.; Thakur, K.; Gautam, R.K. Generalized ILVEN or blaschkoid psoriasis: A persistent dilemma. Nepal J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2019, 17, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.D. Biology of human melanocyte development, piebaldism, and Waardenburg syndrome. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spritz, R.A. Molecular basis of human piebaldism. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1994, 103, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Diao, P.; Wan, R.Y.; Li, L. Piebaldism resulting from a novel deletion mutation of KIT gene in a five-generation Chinese family. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 47, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orphanet. O Portal para as Doenças Raras e os Medicamentos Órfãos. Available online: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Education_AboutRareDiseases.php?lng=PT (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Oliveira, T.; Andrade, L.G. Produção de medicamentos em farmácia de manipulação: Análise da qualidade dos fármacos e sua estabilidade. Rev. Iberoam. Humanid. Ciênc. Educ. 2021, 7, e2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariath, L.M.; Santin, J.T.; Schuler-Faccini, L.; Kiszewski, A.E. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: Update on the clinical and genetic aspects. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, S. Beremagene Geperpavec: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 1131–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, E.; Lara-Corrales, I.; Mellerio, J.; Martinez, A.; Schultz, G.; Burrell, R.; Goodman, L.; Coutts, P.; Wagner, J.; Allen, U.; et al. A consensus approach to wound care in epidermolysis bullosa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012, 67, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwieger-Briel, A.; Kiritsi, D.; Schempp, C.; Has, C.; Schumann, H. Betulin-based Oleogel to improve wound healing in dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A prospective controlled proof-of-concept study. Dermatol. Res. Pract. 2017, 2017, 5068969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, J.S.; Sprecher, E.; Fernandez, M.F.; Schauer, F.; Bodemer, C.; Cunningham, T.; Löwe, S.; Davis, C.; Sumeray, M.; Bruckner, A.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Oleogel-S10 (birch triterpenes) for epidermolysis bullosa: Results from the phase III randomized double-blind phase of the EASE study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2023, 188, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, D.F.; Bodemer, C.; Bruckner, A.L.; Cunningham, T.; Davis, C.; Fernández, M.F.; Kiritsi, D.; Maher, L.; Sprecher, E.; Torres-Pradilla, M.; et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of Oleogel-S10 (birch bark extract) in epidermolysis bullosa: 24-month results from the phase III EASE study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2025, 192, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbrenner, I.; Laszczyk, M.N.; Loew, D.; Schempp, C.M. Influence of the oil phase and topical formulation on the wound healing ability of a birch bark dry extract. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Woelfle, U.; Laszczyk, M.N.; Kraus, M.; Leuner, K.; Kersten, A.; Simon-Haarhaus, B.; Scheffler, A.; Martin, S.F.; Müller, W.E.; Nashan, D.; et al. Triterpenes promote keratinocyte differentiation in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo: A role for the transient receptor potential canonical (subtype) 6. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoia, M.; Oancea, S. Selected evidence-based health benefits of topically applied sunflower oil. Appl. Sci. Rep. 2015, 10, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drąg-Zalesińska, M.; Wysocka, T.; Borska, S.; Drąg, M.; Poręba, M.; Choromańska, A.; Kulbacka, J.; Saczko, J. The new esters derivatives of betulin and betulinic acid in epidermoid squamous carcinoma treatment—In vitro studies. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 72, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Browning, J.; Nikolic, M.; Bodemer, C.; Murrell, D.F.; Lenon, W.; Krusinska, E.; Reha, A.; Lagast, H.; Barth, J.A.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of the investigational topical cream SD-101 (6% allantoin) in patients with epidermolysis bullosa: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trial (ESSENCE study). Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, B.; Kartal, M.; Orhan, I. Cytotoxicity, antiviral and antimicrobial activities of alkaloids, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Pharm. Biol. 2011, 49, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, L.U.; Grabe-Guimarães, A.; Mosqueira, V.C.F.; Carneiro, C.M.; Silva-Barcellos, N.M. Profile of wound healing process induced by allantoin. Acta Cir. Bras. 2010, 25, 460–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Cross-Over Study to Assess the Efficacy of Topical Calcipotriol (Psorcutan® Ointment Containing 0.05 µg/g Calcipotriol) to Improve Wound Healing in Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa (DEB); EU Clinical Trials Register: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Guttmann-Gruber, C.; Hofbauer, J.P.; Tockner, B.; Reichl, V.; Klausegger, A.; Hofbauer, P.; Wolkersdorfer, M.; Tham, K.-C.; Lim, S.S.; Common, J.E.; et al. Impact of low-dose calcipotriol ointment on wound healing, pruritus and pain in patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Banda, F.C. Fototerapia com UVB. Psoríase 2012, 60, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Does, A.M.; Bergman, P.; Agerberth, B.; Lindbom, L. Induction of the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by vitamin D is dependent on the vitamin D receptor and is directly modulated by histone acetylation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wally, V.; Hovnanian, A.; Ly, J.; Buckova, H.; Brunner, V.; Lettner, T.; Ablinger, M.; Felder, T.K.; Hofbauer, P.; Wolkersdorfer, M.; et al. Diacerein orphan drug development for epidermolysis bullosa simplex: A phase 2/3 randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2018, 78, 892–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wally, V.; Kitzmueller, S.; Lagler, F.; Moder, A.; Hitzl, W.; Wolkersdorfer, M.; Hofbauer, P.; Felder, T.K.; Dornauer, M.; Diem, A.; et al. Topical diacerein for epidermolysis bullosa: A randomized controlled pilot study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.T.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, J.Y.; Chu, C.Y. Targeting antibody-mediated complement-independent mechanism in bullous pemphigoid with diacerein. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2024, 114, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawbake, G.R.; Shirolkar, S.V. Formulation, development and evaluation of nanostructured lipid carrier (NLC) based gel for topical delivery of diacerein. Syst. Rev. Pharm. 2020, 11, 794–802. [Google Scholar]

- Chelliah, M.P.; Zinn, Z.; Khuu, P.; Teng, J.M.C. Self-initiated use of topical cannabidiol oil for epidermolysis bullosa. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, e224–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E. Cannabinoids in the management of difficult to treat pain. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2008, 4, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.W. Cannabinoid-based drugs as anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 400–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacher, P.; Bátkai, S.; Kunos, G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 389–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, M.M.; Queiroz, R.H.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S. Safety and side effects of cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent. Curr. Drug Saf. 2011, 6, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaşar, Ş.; Yaşar, B.; Cebeci, F.; Bayoğlu, D.; Nuhoğlu, Ç. Topical sucralfate cream treatment for aplasia cutis congenita with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa: A case study. J. Wound Care 2018, 27, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuelli, L.; Tumino, G.; Turriziani, M.; Modesti, A.; Bei, R. Topical use of sucralfate in epithelial wound healing: Clinical evidence and molecular mechanisms of action. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov. 2010, 4, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiaverini, C.; Passeron, T.; Lacour, J.-P. Topical timolol for chronic wounds in patients with junctional epidermolysis bullosa. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016, 75, e223–e224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grando, S.A.; Pittelkow, M.R.; Schallreuter, K.U. Adrenergic and cholinergic control in the biology of epidermis: Physiological and clinical significance. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1948–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Püttgen, K.; Lucky, A.; Adams, D.; Pope, E.; McCuaig, C.; Powell, J.; Feigenbaum, D.; Savva, Y.; Baselga, E.; Holland, K.; et al. Topical timolol maleate treatment of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20160355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Yu, Q.; Huang, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, W. A self-controlled study of intralesional injection of diprospan combined with topical timolol cream for treatment of thick superficial infantile hemangiomas. Dermatol. Ther. 2018, 31, e12595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkittakandiyil, A.; Phillips, R.; Frieden, I.J.; Siegfried, E.; Lara-Corrales, I.; Lam, J.; Bergmann, J.; Bekhor, P.; Poorsattar, S.; Pope, E. Timolol maleate 0.5% or 0.1% gel-forming solution for infantile hemangiomas: A retrospective, multicenter, cohort study. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2012, 29, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, S.A.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Brodell, R.T. Treatment of Hailey-Hailey disease with tacrolimus ointment and clobetasol propionate foam. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2004, 3, 200–203. [Google Scholar]

- Falto-Aizpurua, L.; Arora, H.; Bray, F.N.; Cervantes, J. Management of familial benign chronic pemphigus. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, M.d.J.S.; Marinho, P.C.; Frade, T.C.; Amin, G.A.; de Carvalho, L.S.; Santos, L.E.C. Topical aluminum chloride as a treatment option for Hailey-Hailey disease: A remarkable therapeutic outcome case report. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2024, 99, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khang, J.; Yardman-Frank, J.M.; Chen, L.-C.; Chung, H.J. Recalcitrant Hailey-Hailey disease successfully treated with topical ruxolitinib cream and dupilumab. JAAD Case Rep. 2023, 42, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, M.O.M.Q.; Figueiredo, G.A.P.; Evangelista, A.C.; Bauk, A.R. Darier’s disease: Treatment with topical sodium diclofenac 3% gel. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2023, 98, 882–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Alarcon, S.; Sanchis-Sanchez, C.; Mateu-Puchades, A. Diclofenac sodium 3% gel for Darier’s disease treatment. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millán-Parrilla, F.; Rodrigo-Nicolás, B.; Molés-Poveda, P.; Armengot-Carbó, M.; Quecedo-Estébanez, E.; Gimeno-Carpio, E. Improvement of Darier disease with diclofenac sodium 3% gel. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, e89–e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hagino, T.; Nakano, H.; Saeki, H.; Kanda, N. A case of Darier’s disease with a novel missense mutation in ATP2A2 successfully treated with calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate two-compound ointment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 367–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle, L.; Foulad, D.P.; Rojek, N.W. Improvement in malodor with topical metronidazole gel in Darier disease. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 1027–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, T.B.; Schrage, N.F.; Reim, M. Congenital ectropion in ichthyosis congenita mitis and gravis. Ophthalmologe 2006, 103, 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, J.D.; Dantas, P.E.; Alves, M.R.; Freitas, D. Diseases, conditions, and drugs associated with cicatricial ectropion. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2019, 82, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Browning, J.; Parish, L.C.; Bunick, C.G.; Rome, Z.; Bhatia, N. Safety, tolerability, and efficacy of a novel topical isotretinoin formulation for the treatment of X-linked or lamellar congenital ichthyosis: Results from a phase 2a proof-of-concept study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craiglow, B.G.; Choate, K.A.; Milstone, L.M. Topical tazarotene for the treatment of ectropion in ichthyosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2013, 149, 598–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, E.; Ferraro, M.; Di Vincenzo, S.; Gerbino, S.; Bruno, A.; Lanata, L.; Gjomarkaj, M. Oxidative stress and innate immunity responses in cigarette smoke stimulated nasal epithelial cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2014, 28, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalker, D.K.; Lesher, J.L.; Smith, J.; Klauda, H.C.; Pochi, P.E.; Jacoby, W.S.; Yonkosky, D.M.; Voorhees, J.J.; Ellis, C.N.; Matsuda-John, S.; et al. Efficacy of topical isotretinoin 0.05% gel in acne vulgaris: Results of a multicenter, double-blind investigation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1987, 17, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, R.V.; Garg, A.; Worobec, S.M. Lamellar ichthyosis treated with tazarotene 0.1% gel. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55 (Suppl. 5), S94–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, L.; Castelo-Soccio, L. Topical N-acetylcysteine in ichthyosis: Experience in 18 patients. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2018, 35, 528–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, P.; Bauzá, A. Topical N-acetylcysteine for lamellar ichthyosis. Lancet 1999, 354, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila-Seijo, P.; Flórez, A.; Davila-Pousa, C.; No, N.; Ferreira, C.; De la Torre, C. Topical N-acetylcysteine for the treatment of lamellar ichthyosis: An improved formula. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Freire, L.; Dávila-Pousa, M.C.; Batalla-Cebey, A.; Crespo-Diz, C. Development of a carbocysteine 10% + urea 5% cream for the topical treatment of congenital ichthyosis. Farm. Hosp. 2022, 46, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bassotti, A.; Moreno, S.; Criado, E. Successful treatment with topical N-acetylcysteine in urea in five children with congenital lamellar ichthyosis. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2011, 28, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajawi, S.M.; Jafarri, S.A.; Buraik, M.A.; Al Attas, K.M.; Hannani, H.Y. Pathogenesis-based therapy: Cutaneous abnormalities of CHILD syndrome successfully treated with topical simvastatin monotherapy. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Y.; Deng, D.; Wu, Z.; Bao, L.; Li, M.; Yao, Z. CHILD syndrome mimicking verrucous nevus in a Chinese patient responded well to the topical therapy of compound of simvastatin and cholesterol. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 1209–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, K.R.; Machado, M.C.; Oliveira, Z.N.; Nico, M.M. CHILD syndrome: Successful treatment of skin lesions with topical lovastatin and cholesterol lotion. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2019, 94, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paller, A.S.; van Steensel, M.A.; Rodriguez-Martín, M.; Sorrell, J.; Heath, C.; Crumrine, D.; van Geel, M.; Cabrera, A.N.; Elias, P.M. Pathogenesis-based therapy reverses cutaneous abnormalities in an inherited disorder of distal cholesterol metabolism. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2011, 131, 2242–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzmony, L.; Lim, Y.H.; Hamilton, C.; Leventhal, J.S.; Wagner, A.; Paller, A.S.; Choate, K.A. Topical cholesterol/lovastatin for the treatment of porokeratosis: A pathogenesis-directed therapy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Bardawil, T.; Saade, S.; Chedraoui, A.; Ramadan, N.; Hasbani, D.J.; Abbas, O.; Nemer, G.; Rubeiz, N.; Kurban, M.; et al. Use of topical glycolic acid plus a lovastatin-cholesterol combination cream for the treatment of autosomal recessive congenital ichthyoses. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 1320–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, C.; Abdallah, B.; Hasbani, D.; Abbas, O.; Kibbi, A.G.; Hamie, L.; Kurban, M.; Rubeiz, N. CHILD syndrome: A modified pathogenesis-targeted therapeutic approach. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 2018, 176, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaraldi, B.M.; Jaime, T.J.; Guaraldi, R.M.; Melo, D.F.; Nogueira, O.M.; Rodrigues, N. Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratodermia—Case report. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 109–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarikci, N.; Göncü, E.K.; Yüksel, T.; Singer, R.; Topal, I.O.; Şahin, İ.M. Progressive symmetrical erythrokeratoderma on the face: A rare condition and successful treatment with calcipotriol. JAAD Case Rep. 2016, 2, 70–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severson, K.J.; Morken, C.M.; Nelson, S.A.; Mangold, A.R.; Pittelkow, M.R.; Swanson, D.L. Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis treated with tretinoin and calcipotriene. JAAD Case Rep. 2024, 53, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomran, H.; Kanitakis, J. Adult-onset porokeratotic eccrine ostial and dermal duct nevus:dermatoscopic findings and treatment with tazarotene. Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 26, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, B.M.; Peveling-Oberhag, A.; Zimmer, S.; Wegner, J.; Sohn, A.; Grabbe, S.; Staubach, P. Effective treatment of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis with chemical peels—Customary treatment for a rare disease. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2020, 31, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portelli, M.G.; Bălăceanu-Gurău, B.; Orzan, O.A.; Zurac, S.A.; Tudose, I. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of giant porokeratosis: A case report. Cureus 2024, 16, e55155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, J.E.; Nazarian, R.M.; Lorenzo, M.E. Treatment of porokeratosis of Mibelli with combined use of topical fluorouracil and calcipotriene. JAAD Case Rep. 2021, 9, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santa Lucia, G.; Snyder, A.; Lateef, A.; Drohan, A.; Gregoski, M.J.; Barton, V.; Elston, D.M. Safety and efficacy of topical lovastatin plus cholesterol cream vs topical lovastatin cream alone for the treatment of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, D.; Pyatetsky, I.A.; Barrett, K.L.; Kannan, K.S.; Wright, K.; Baker, W. Bilateral linear porokeratosis treated with topical lovastatin 2% monotherapy. Cureus 2023, 15, e43657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Hu, B.; Chen, Q.; Su, F.; Chen, L.-Q. CHILD syndrome combined linear porokeratosis in a patient with a good response to the topical lovastatin/cholesterol ointment. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2025, 36, 2478217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultan, Q.; Massey, B.; Cotter, D.G. A case of disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis successfully treated with topical lovastatin/cholesterol gel. Cureus 2023, 15, e40582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, N.; Choate, K.A.; Atzmony, L. Two percent lovastatin ointment as a pathogenesis-directed monotherapy for porokeratosis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020, 6, 1110–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison-Peyron, N.; Girard, C.; Girod, M.; Dereure, O. A new case of allergic contact dermatitis to topical simvastatin used for treatment of porokeratosis. Contact Dermat. 2025, 93, 73–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, B.; Ziętek, M.; Kowalewski, C. Giant inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: Difficulties in the management. Adv. Dermatol. Allergol. 2023, 40, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, D.; Saha, A. Genital/perigenital inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus: A case series. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Micali, G.; Lacarrubba, F.; Nasca, M.R.; Ferraro, S.; Schwartz, R.A. Topical pharmacotherapy for skin cancer: Part II. Clinical applications. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 979.e1–979.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollina, U.; Tchernev, G. ILVEN—Complete remission after administration of topical corticosteroid (case review). Georgian Med. News 2017, 263, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zemero, M.I.; Santos, M.A.; Mendes, M.A.; Pires, C.A. Nevo epidérmico verrucoso inflamatório linear e diagnóstico diferencial com a psoríase linear: A respeito de um caso. Medicina 2021, 54, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, S.K.; McEleney, M. Topical corticosteroids: Choice and application. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 337–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bashir, S.; Dreher, F.; Chew, A.; Zhai, H.; Levin, C.; Stern, R.; Maibach, H. Cutaneous bioassay of salicylic acid as a keratolytic. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 292, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.S.; Kim, H.O.; Woo, S.M.; Lee, D.H. Use of dexpanthenol for atopic dermatitis—Benefits and recommendations based on current evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abadie, M.; Salih, P.; Al-Rubaye, M. Effective treatment of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with pulsed 5-fluorouracil therapy. J. Dermatol. Dis. 2018, 5, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Barney, E.; Prose, N.S.; Ramirez, M. Inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus treated successfully with crisaborole ointment in a 5-year-old boy. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2019, 36, 404–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.; Padhiyar, J.; Patel, A.; Chhibber, A.; Patel, T.; Patel, B. Successful amelioration of inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus with topical sirolimus. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorigo, M.; Quintaneiro, C.; Breitenfeld, L.; Cairrao, E. Exposure to UV-B filter octylmethoxycinnamate and human health effects: Focus on endocrine disruptor actions. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welch, M.L.; Smith, K.J.; Skelton, H.G.; Frisman, D.M.; Yeager, J.; Angritt, P.; Wagner, K.F.; Military Medical Consortium for the Advancement of Retroviral Research. Immunohistochemical features in inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevi suggest a distinctive pattern of clonal dysregulation of growth. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993, 29, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallory, S.B.; Bree, A.; Chern, P. Dermatologie Pédiatrique; Elsevier Masson: Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, 2007; ISBN 9782842998325. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, C.M.; Máximo, L.N.C.; Fontanezi, B.B.; da Silva, R.S.; Gaspar, L.R. Diethylamino hydroxybenzoyl hexyl benzoate (DHHB) as additive to the UV filter avobenzone in cosmetic sunscreen formulations—Evaluation of the photochemical behavior and photostabilizing effect. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 99, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pniewska, A.; Kalinowska-Lis, U. A survey of UV filters used in sunscreen cosmetics. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.W.; Jaffe, M.P.; Li, W.W.; Haynes, H.A. Off-Label Dermatologic Therapies: Usage, Risks, and Mechanisms. Arch. Dermatol. 1998, 134, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarman, J.H.; Fleischer, A.B., Jr.; Feldman, S.R. Off-label prescribing in the treatment of dermatologic disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INFARMED. Relatório de Avaliação do Pedido de Comparticipação de Medicamento para Uso Humano—Diclofenac (Solaraze); INFARMED: Lisboa, Portugal, 2015; Available online: https://www.infarmed.pt/documents/15786/1437513/diclofenac_solaraze_parecer_net_20150126.pdf/e4a823bc-c5f9-41d8-98b3-788b853bfdfb?version=1.0 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Therapeutic Goods Administration. Extract from the Clinical Evaluation Report for Calcipotriol 50 µg/g and Betamethasone (as Dipropionate) 500 µg/g (Daivobet 50/500 Gel); Submission PM-2011-04144-3-5/PM-20; TGA: Woden, Australia, 2013. Available online: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-calcipotriol-betamethasone-130809-cer.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Ministério da Saúde (BR); Secretária de Atenção Especialização à Saúde; Secretária de Ciência, Tecnologia, Inovação e Insumos Estratégicos em Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas das Ictioses Hereditárias; Portaria Conjunta no 12, de 13 de julho de 2022; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, DF, Brasil, 2002. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/pcdt/i/ictioses-hereditarias.pdf/view (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Weidner, T.; Illing, T.; Miguel, D.; Elsner, P. Treatment of Porokeratosis: A Systematic Review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017, 18, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Resumo das Características do Medicamento—Filsuvez®; EMA: Parma, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/pt/documents/product-information/filsuvez-epar-product-information_pt.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Bermudez, N.M.; Warp, P.V.; Hargis, A.; Yaghi, M.; Schachner, L.; Frost, P. Epidermolysis Bullosa: A Review of Wound Care and Emerging Treatments. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2024, 13, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Vyjuvek, INN-Beremagene Geperpavec: Summary of Product Characteristics; European Comission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/2025/20250423165790/anx_165790_en.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Angelis, A.; Mellerio, J.E.; Kanavos, P. Understanding the socioeconomic costs of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in Europe: A costing and health-related quality of life study. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2022, 17, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Oji, V.; Sommer, R.; Augustin, M.; Ständer, S.; Salzmann, S.; Kiekbusch, K.; Bodes, J.; Danzer, M.F.; Traupe, H.; et al. Personal, financial and time burden in inherited ichthyoses: A survey of 144 patients in a university-based setting. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 1809–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saúde. Portaria no 36/2018, de 26 de Janeiro. Determina que as Medidas de Tratamento de Doentes com Ictiose Beneficiam de um Regime Excecional de Comparticipação. Diário de República no 19/2018, Série I, 26 de Janeiro de 2018; pp. 722–723. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/detalhe/portaria/36-2018-114585065 (accessed on 7 November 2025).

| Descriptors or Keywords | PubMed | SciELO | Embase | Cochrane | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical treatment and inflammatory linear verrucous epidermal nevus | 3 | 0 | 27 | 1 | 31 |

| Topical treatment and epidermolysis bullosa | 32 | 1 | 309 | 55 | 397 |

| Topical treatment and Hailey–Hailey disease | 15 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 16 |

| Topical treatment and Darier disease | 2 | 0 | 61 | 0 | 63 |

| Topical treatment and ichthyosis | 28 | 2 | 406 | 17 | 453 |

| Topical treatment and erythrokeratodermias | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Topical treatment and porokeratosis | 26 | 0 | 58 | 4 | 88 |

| Topical treatment and piebaldism | 0 | 1 | 11 | 3 | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, B.d.A.; Torres, A.; Ricci-Júnior, E.; Almeida, I.F.; Monteiro, M.S.S.B. Topical Treatments for Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111762

Oliveira BdA, Torres A, Ricci-Júnior E, Almeida IF, Monteiro MSSB. Topical Treatments for Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111762

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Beatriz de Araujo, Ana Torres, Eduardo Ricci-Júnior, Isabel F. Almeida, and Mariana Sato S. B. Monteiro. 2025. "Topical Treatments for Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases: A Narrative Review" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111762

APA StyleOliveira, B. d. A., Torres, A., Ricci-Júnior, E., Almeida, I. F., & Monteiro, M. S. S. B. (2025). Topical Treatments for Rare Genetic Dermatological Diseases: A Narrative Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111762