Abstract

An N-acylated furazan-3-amine of a Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) project has shown activity against different strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Seventeen new derivatives were prepared and tested in vitro for their activities against blood stages of two strains of Plasmodium falciparum. Several structure–activity relationships were revealed. The activity strongly depended on the nature of the acyl moiety. Only benzamides showed promising activity. The substitution pattern of their phenyl ring affected the activity and the cytotoxicity of compounds. In addition, physicochemical parameters were calculated (log P, log D, ligand efficiency) or determined experimentally (permeability) via a PAMPA. The N-(4-(3,4-diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide possessed good physicochemical properties and showed high antiplasmodial activity against a chloroquine-sensitive strain (IC50(NF54) = 0.019 µM) and even higher antiplasmodial activity against a multiresistant strain (IC50(K1) = 0.007 µM). Compared to the MMV compound, the permeability and the activity against the multiresistant strain were improved.

1. Introduction

Malaria is, to this day, one of the most dangerous infectious diseases worldwide. It is caused by protozoa of the genus Plasmodium. An estimated number of 229 million cases occurred in 2019, resulting in more than 400,000 deaths. The burden of this infection is mostly carried by children under the age of five located in sub-Saharan Africa. Five Plasmodium species are human pathogenic: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale and P. knowlesi of which P. falciparum is the most predominant cause of death [,]. The discovery of chloroquine in the 1960s had an enormous impact on the fight against malaria. Increasing resistance development in P. falciparum, however, was reported more than fifty years ago, and the cost of it in human lives was severe [,]. The first-line treatment for malaria infections is an artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT). A rapid-acting artemisinin derivative is combined with an antimalarial drug with a long half-life period. However, artemisinin drug resistances are increasingly emerging in P. falciparum, especially within the Southeast Asian region, and are therefore jeopardizing the success of ACTs [,]. A new strategy to impede the increasing resistance development temporarily is the application of triple artemisinin-based combination therapy (TACT) [,]. Due to the threat of potentially untreatable P. falciparum malaria, the development of drugs with new modes of action is of utmost importance [,,].

Phenotypic screening or whole-cell screening represents a significant breakthrough in the discovery of new antimalarial lead structures. The majority of compounds currently in clinical trials were discovered by means of this screening method. The benefit of phenotypic screening is that the activity is not determined at isolated targets, but in the physiological environment. The implementation of this method led to a 100-fold reduction in the cost for screening compounds against P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes compared to other methods. Most commonly, the target search starts afterward [,].

In 2016, the organization Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) published the results of a major phenotypic screening project. The so-called Malaria Box contains 400 substances with activity against P. falciparum and serves as a starting point for the development of new lead structures. Alongside activity assays against different strains and life cycle stages of P. falciparum, their cytotoxicity against 73 human cell lines was determined as well [].

The furazan 1 (Scheme 1) from MMV’s Malaria Box project is a promising lead structure for the development of new antimalarials. It shows antiplasmodial activity against the multiresistant strains K1 and Dd2 of Plasmodium falciparum []. Furthermore, a P. berghei assay revealed activity against liver schizonts [,]. The potential of inhibiting the transmission from humans to mosquitoes by working against early gametocyte stages makes this compound even more promising [,,,,].

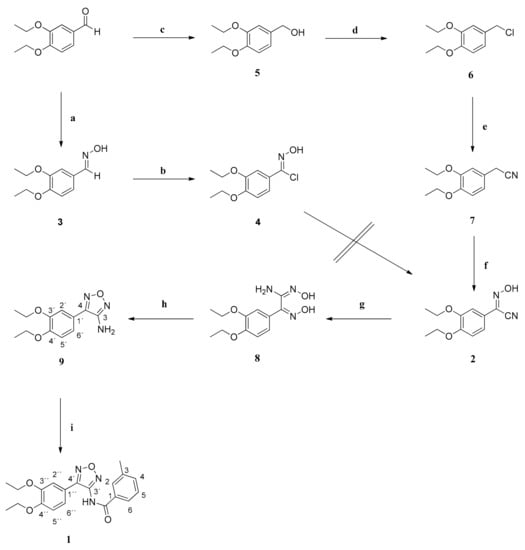

Scheme 1.

Preparation of compound 1. Reagents and conditions: (a) NH2OH x HCl, NaHCO3, MeOH, H2O, 100 °C, 2 h; (b) N-chlorosuccinimide, DMF, rt, 20 h; (c) NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 1 h; (d) thionyl chloride, CH2Cl2, rt, 20 h; (e) KCN, DMF, rt, 4 h; (f) (1) NaOEt, 0 °C, 30 min; (2) 3-methylbutyl nitrite, EtOH, rt, 20 h; (g) NH2OH x HCl, NaHCO3, MeOH, H2O, 100 °C, 20 h; (h) 2N NaOH, 100 °C, 20 h; (i) (1) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 20 min; (2) 3-methylbenzoyl chloride, DMF, 60 °C, 48 h.

Within two subsequent studies, the possible targets of furazan 1 could be identified. Firstly, it is likely to inhibit the Na+-efflux pump PfATP4, which is essential in maintaining the parasite’s ion homeostasis. PfATP4 is localized on the plasma membrane of P. falciparum and represents an attractive target for novel antimalarials. However, genetic PfATP4 mutations led to an increase in resistance development against several preclinical and clinical antimalarials. The furazan 1 also interacts with the enzyme deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (DOHH) which is part of the hypusine biosynthesis [,,,].

The aim of this study was to synthesize new derivatives of compound 1 in order to increase the antiplasmodial activity and reveal structure–activity relationships (SARs). All newly synthesized compounds were characterized and tested in vitro for their activities against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 and the multiresistant K1 strain of P. falciparum. The results were compared to those of drugs in use. Furthermore, the passive diffusion of the compounds was determined by a parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) to classify compounds according to their permeability. Especially in the development of new antimalarials, it is important to focus on substances that are orally bioavailable, because of the potential storage problems with other formulations in countries where malaria is prevalent and the simpler use. The PAMPA is an early screening assay to differentiate between compounds that have a good oral absorption potential and those that do not.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

The precursor of all derivatives, compound 1, was synthesized from 3,4-diethoxybenzaldehyde in a multistep procedure via the formation of a cyanide-substituted oxime 2. Since no synthetic route to generate compound 1 has been published yet, we used a retrosynthetic approach. Two different methods were applied for the synthesis of the oxime 2. Treatment of 3,4-diethoxybenzaldehyde with hydroxylamine hydrochloride gave the aldoxime 3 in high yields. Conversion of the benzaldoxime to the benzimidoyl chloride 4 succeeded with N-chloro succinimide. However, subsequent reaction with potassium cyanide to afford compound 2 failed. Therefore, an alternative method was used, and compound 1 was successfully prepared in a seven-step procedure.

At first, 3,4-diethoxybenzaldehyde was reduced to its corresponding alcohol 5 using sodium borohydride in methanol. The successful reduction was obvious by the disappearance of the signal of the formyl proton in the 1H NMR spectrum. A resonance at ca. 4.5 ppm appeared for the new methylene group. Treatment with thionyl chloride gave the benzyl chloride 6. Due to the replacement of the hydroxy group by a chlorine atom the 13C resonance of the methylene group was shifted 18 ppm upfield. It was then converted into the 2-phenylacetonitrile 7 by means of a Kolbe nitrile synthesis []. The replacement of the chlorine atom by a cyano group shifted the proton signal of the methylene group 1 ppm upfield. Its α-protons were replaced by a hydroximino group. After deprotonation with sodium ethylate, 3-methylbutyl nitrite was added, yielding the desired oxime 2 []. The oxime carbon gave a new signal at ca. 133 ppm in the 13C NMR spectrum, whereas the resonance of the methylene group was missing. It was treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride giving the amide oxime 8. The conversion of the cyano group to an amidoxime shifted the signal of the concerned carbon atom 35 ppm downfield in the 13C NMR spectrum. Refluxing of 8 with 2N NaOH led to ring closure, affording the 3-aminofurazan 9. Due to the formation of the furazan ring system, the signals of both hydroxy groups disappeared in the 1H NMR spectrum. The resonance of the amino protons was shifted 0.5 ppm downfield. The desired compound 1 was finally obtained by reaction of 9 with sodium hydride and 3-methylbenzoyl chloride in DMF (Scheme 1) []. The successful amide bond formation was detected by a significant change in the NMR spectrum. The signal of the aromatic amino protons was replaced by a broadened signal at high frequencies.

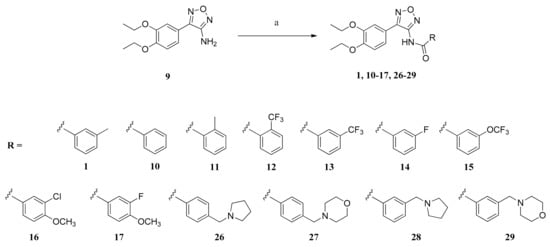

To obtain some insight considering structure–activity relationship, the amino furazan 9 was subsequently coupled with different carboxylic acids. Furthermore, the importance of the meta-methyl group was investigated. Compounds 10–17 and 26–29 were synthesized.

The amides 1, 10–14, 16, 17 and 26–29 were obtained by coupling the amino furazan 9 with the respective benzoyl chlorides that were commercially available or generated by the reaction of benzoic acids and oxalyl dichloride (Scheme 2) [,]. Reaction of the N-hydroxy succinimide ester of the 3-(trifluoromethoxy)benzoic acid with 9 yielded 15 [].

Scheme 2.

Preparation of compounds 1, 10–17 and 26–29. Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 20 min; (2) acyl chloride, DMF, 60 °C, 48 h (compounds 1 and 10–14); or (1) carboxylic acid, oxalyl dichloride, CH2Cl2, rt, 20 h; (2) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 20 min; (3) acid chloride, DMF, 60 °C, 48 h (compounds 16, 17 and 26–29); or (1) carboxylic acid, N-hydroxy succinimide, DCC, THF, rt, 24 h; (2) DMF, rt, 15 min; (3) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 20 min; (4) acid chloride, DMF, 60 °C, 48 h (compound 15).

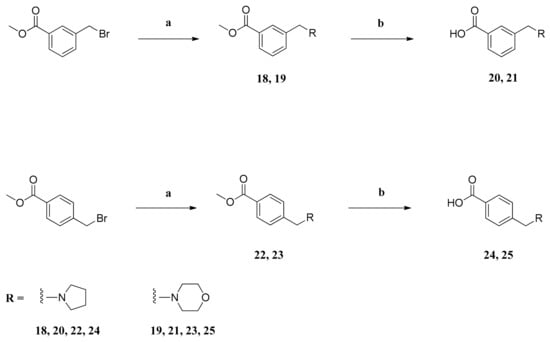

The carboxylic acids used for the synthesis of compounds 26–29 had to be synthesized from methyl 3-(bromomethyl)benzoate and methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate (Scheme 3). The benzyl bromides reacted with the respective heterocyclic amines, potassium carbonate and catalytic amounts of sodium iodide in acetonitrile to form the tertiary amines 18, 19, 22 and 23. Treatment of the methyl esters with 2N NaOH in methanol gave the desired carboxylic acids 20, 21, 24 and 25 [].

Scheme 3.

Preparation of compounds 20, 21, 24 and 25. Reagents and conditions: (a) amine, NaI, K2CO3, acetonitrile, 80 °C, 20 h; (b) 2N NaOH, MeOH, rt, 20 h.

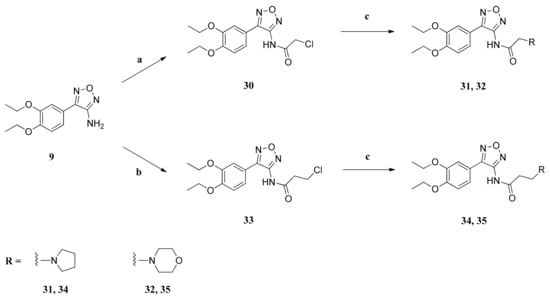

Within another series of derivatives, the planar aromatic system was replaced by different aliphatic heterocycles. Furthermore, we also modified the chain length between the amide carbonyl groups and the ω-(dialkylamino) groups. Aside from a methylene linker, the influence of an ethyl linker was investigated.

To obtain compounds 31, 32, 34 and 35, the amino furazan 9 was treated at first with the corresponding ω-chloroacyl chloride, yielding the ω-chloroalkanamides 30 and 33 []. These were treated with the corresponding amines, giving the pyrrolidine derivatives 31 and 34, as well as the morpholine derivatives 32 and 35 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Preparation of compounds 31, 32, 34 and 35. Reagents and conditions: (a) chloroacetyl chloride, pyridine, diethyl ether, benzene, 80 °C, 20 h; (b) 3-chloropropanoyl chloride, pyridine, diethyl ether, benzene, 80 °C, 20 h; (c) amine, NaI, K2CO3, acetonitrile, 80 °C, 20 h.

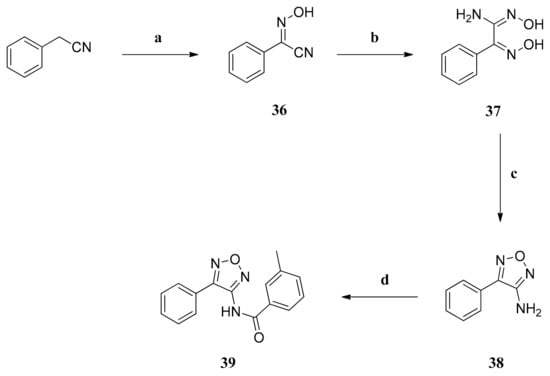

To gain further insight regarding SARs, we also synthesized compound 39. This compound possesses a 4-phenyl substituent instead of a 4-(3,4-diethoxyphenyl) substituent when compared to compound 1.

The synthesis was similar to the synthesis of compound 1 (Scheme 1). Starting from benzyl cyanide, the oxime 36 was obtained by treatment of the nitrile with 3-methylbutyl nitrite after deprotonation with sodium ethylate. The cyano group was further converted to the amidoxime 37 and further on to the aminofurazan 38 after a cyclization reaction. The final compound 39 was obtained by an amide reaction of the aminofurazan 38 with 3-methylbenzoyl chloride (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5.

Preparation of compound 39. Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) NaOEt, 0 °C, 30 min; (2) 3-methylbutyl nitrite, EtOH, rt, 20 h; (b) NH2OH x HCl, NaHCO3, MeOH, H2O, 100 °C, 20 h; (c) 2N NaOH, 100 °C, 20 h; (d) (1) NaH, DMF, 0 °C, 20 min; (2) 3-methylbenzoyl chloride, DMF, 60 °C, 48 h.

2.2. Antiplasmodial Activity and Cytotoxicity

All newly synthesized compounds were at first tested in vitro for their antiplasmodial activity against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 of P. falciparum. The most active compounds were further tested against the K1 strain of P. falciparum, which is resistant to chloroquine and pyrimethamine. Cytotoxicity was determined using rat skeletal myoblasts (L-6 cells). As standards served chloroquine, artemisinin and podophyllotoxin.

In order to evaluate the influence of a series of inserted acyl moieties, the 4-(3,4-diethoxyphenyl) substituent of the 3-aminofurazan was left unaltered. The substitution pattern of the aromatic system was diversified to evaluate the importance of the meta-methyl group of furazan 1. The methyl group was replaced by several other substituents, including (dialkylamino)methyl substitution in meta- and para-position. Furthermore, the benzoyl moiety was exchanged with ω-(dialkylamino)acyl residues in order to observe the importance of the aromatic system for activity. The variation of the linker length between the amide and the aliphatic heterocyclic amines might increase the flexibility of the substituents, resulting in a positive effect on cytotoxicity.

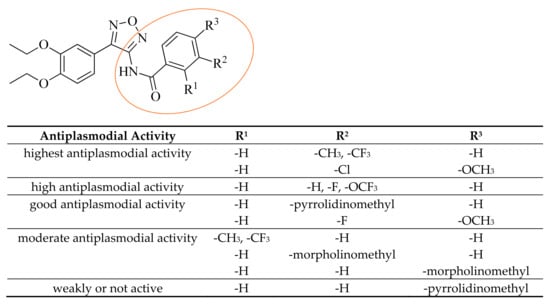

Compound 1 served as comparison for all newly synthesized compounds (Table 1). It shows no difference in activity against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.011 µM) and the multiresistant K1 strain (PfK1 IC50 = 0.011 µM) of Plasmodium falciparum. The low cytotoxicity (L-6 cells IC50 = 159.3 µM) combined with the high antiplasmodial activity results in an excellent selectivity index for both strains (SIPfNF54 = SIPfK1 = 14,483). Compound 10 is the 3-demethyl analog of 1. It shows still high antiplasmodial activity against PfNF54 (IC50 = 0.076 µM) and PfK1 (IC50 = 0.091 µM) but a 7–8-fold decrease in activity when compared to 1. The 2-substituted compounds 11 and 12 (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.343–0.831 µM) and the 4-substituted compounds 26 and 27 (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.674–4.055 µM) possess only moderate or very weak antiplasmodial activity. With the exception of the only moderately active 3-(morpholin-4-yl)methyl derivative 29 (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.712 µM), the series of 3-substituted analogs exhibited good to excellent activity (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.014–0.192 µM). Its 3-(pyrrolidin-4-yl)methyl analog 28 showed a 4-fold increase in activity (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.192 µM). The fluorinated analogs 13, 14 and 15 were among the most active of the new compounds (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.019–0.098 µM). Compared to its activity against PfNF54 (IC50 = 0.049 µM), the 3-fluoro derivative 14 showed the expected decrease in activity against the multiresistant strain PfK1 (IC50 = 0.108 µM). However, its 3-(trifluoromethyl) analog 13 was even more active against the multiresistant strain PfK1 (IC50 = 0.007 µM) than against PfNF54 (IC50 = 0.019 µM). Against this strain, it even surpassed the activity of compound 1 (PfK1 IC50 = 0.011 µM) and showed similar activity to artemisinin (PfK1 IC50 = 0.0064 µM). Likewise, the 3-substituted 4-methoxy compounds 16 and 17 exhibited promising activity against PfNF54 (IC50 = 0.014–0.167 µM). Against the sensitive strain, the 3-chloro-4-methoxybenzamide 16 possessed the highest activity (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.014 µM), which is similar to 1 (PfNF54 IC50 = 0.011 µM). Replacement of the benzamide by a ω-(dialkylamino)acetamide or a ω-(dialkylamino)propanamide moiety led to inactive compounds 31, 32, 34 and 35 (PfNF54 IC50 = 7.24–56.01 µM). In comparison to 1 (L-6 cells IC50 = 159.3 µM), all of the more active compounds showed increased cytotoxicity (L-6 cells IC50 = 9.24–111.2 µM). However, the selectivity indexes of the most promising compounds 10, 13, 14 and 16 were still very high (S.I. = 380–1463).

Table 1.

Activities of compounds 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39 against P. falciparum NF54, P. falciparum K1 and L-6 cells, expressed as IC50 (µM) a.

The removal of both ethoxy groups of the left-hand side ring, like in compound 39, resulted in a massive loss in activity against the chloroquine-sensitive strain PfNF54 (IC50 = 21.52 µM) and the multiresistant strain PfK1 (IC50 = 39.92 µM). This affirms the positive impact of the 3,4-diethoxyphenyl substitution pattern.

2.3. Physicochemical Properties and Permeability

In addition to antiplasmodial activity tests of compounds 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39, physicochemical parameters like log P and log D7.4 were calculated (using the ChemAxon software JChem for Excel). Furthermore, test compounds had to meet conditions of sufficient ligand efficiency (LE) [] and effective permeability (Pe). The latter was determined by a PAMPA (Table 2) []. The log P values of the compounds range between 1.50 and 5.11. The inactive ω-(dialkylamino)alkanamides 31, 32, 34 and 35 have by far the lowest log P values (log P = 1.50–2.36). The most active compounds have good log p values (log P = 3.66–4.56). All compounds with considerable antiplasmodial activity have log D7.4 values ranging from 3.09 to 5.11. The permeability of compounds was only detectable for selected compounds due to insufficient solubility or excessive mass retention in the PAMPA. All new compounds showed increased permeability (Pe = 3.90–10.80 × 10−6 cm/s) in comparison to 1 (Pe = 2.77 × 10−6 cm/s). The most promising compound 13 has only slightly higher permeability than 1 (Pe = 4.26 × 10−6 cm/s), whereas the inactive ω-aminoacetamides 31 and 32 show by far the best permeabilities (Pe = 10.25–10.80 × 10−6 cm/s). However, in general, substances with a permeability above 1.5 × 10−6 cm/s are considered as having good permeability.

Table 2.

Key physicochemical parameters and PAMPA values of compounds 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39.

Ligand efficiency has become an important concept in drug development, partly due to the realization that large ligands have a disadvantage in terms of the molecular properties necessary for bioavailability. It is defined as the binding free energy for a ligand divided by its number of heavy atoms (HA). Proposed acceptable values for drug candidates are ~0.3 kcal/mol/HA and higher. Out of all tested compounds, 1 has the highest ligand efficiency (LE = 0.404 kcal/mol/HA). The compounds 10, 13, 14 and 16 also exhibit promising ligand efficiencies (LE = 0.353–0.375 kcal/mol/HA).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Instrumentation and Chemicals

Melting points were obtained on an Electrothermal IA 9200 melting point apparatus. IR spectra: Bruker Alpha Platinum ATR FTIR spectrometer (KBr discs); frequencies are reported in cm−1. The structures of all newly synthesized compounds were determined by one- and two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. NMR spectra: Varian UnityInova 400 (298 K) 5 mm tubes, TMS as internal standard. Shifts in 1H NMR (400 MHz) and 13C NMR (100 MHz) spectra are reported in ppm; 1H- and 13C-resonances were assigned using 1H,1H- and 1H,13C-correlation spectra and are numbered as given in Scheme 1. Signal multiplicities are abbreviated as follows: br, broad; d, doublet; dd, doublet of doublets; ddd, doublet of doublet of doublets; m, multiplet; s, singlet; t, triplet; td, triplet of doublets; q, quartet. HRMS: Micromass Tofspec 3E spectrometer (MALDI) and GCT-Premier, Waters (EI, 70 eV). Materials: column chromatography (CC): silica gel 60 (Merck 70–230 mesh, pore diameter 60 Å), aluminium oxide (pH: 9.5, Fluka), thin-layer chromatography (TLC): TLC plates silica gel 60 F254 (Merck), aluminium oxide 60 F254 (neutral, Merck). Experiments to assess the purity of final compounds were carried out on an Agilent 1110 HPLC device (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) equipped with an auto sampler and a VWL detector. Ultraviolet detection was performed at 214 nm. The measurements were carried out under isocratic conditions at ambient temperature with a flowrate of 2 mL/min and an injection volume of 20 µL. Data were collected with Chemstation Rev. B. 0903 (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) software. A LiChrospher 100 RP-18e, 125 mm × 4 mm, 3 µm from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany) served as stationary phase. Mobile phase was prepared by mixing a 20 mM ammonium phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 2.4 and acetonitrile (2:1). Samples were prepared by dissolving 1 mg each in 1 mL methanol. Unless otherwise noted, all compounds were found to be >95% pure by this method. PAMPA: 96-well precoated Corning Gentest PAMPA plate (Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA), 96-well UV-Star Microplates (Greiner Bio-One, Kremsmünster, Austria), SpectraMax M3 UV plate reader (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA, USA). 1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra of new compounds are available in Supplementary Materials Section (Figures S1–S23).

3.2. Syntheses

(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)methanol (5): NaBH4 (0.57 g (15.00 mmol)) was added in portions to an ice-cooled solution of 3,4-diethoxybenzaldehyde (2.91 g (15.00 mmol)) in dry methanol (16 mL). After that, the ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 1 h. Then, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was mixed with water and extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phases were washed with water, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo giving compound 5 as colorless oil (2.80 g (95%)), which was used without further purification.

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

4-(Chloromethyl)-1,2-diethoxybenzene (6): Thionyl chloride (4.14 g (34.80 mmol)) was added dropwise via a dropping funnel to an ice-cooled solution of benzyl alcohol 5 (2.36 g (12.00 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (50 mL). The ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 20 h. Then, the reaction was quenched with 2N NaOH at 0 °C and the mixture was basified to a pH of 10–11. The aqueous and organic phases were separated and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phases were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo, giving compound 6 as brown oil (2.47 g (96%)), which was used without further purification. IR = 2977, 1604, 1510, 1476, 1428, 1392, 1256, 1232, 1135, 1038, 985, 805; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.42–1.47 (m, 6H, 2 CH3), 4.06–4.13 (m, 4H, 2 CH2), 4.55 (s, 2H,CH2Cl), 6.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 6.90 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.0 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 6.91 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.76 (2 CH3), 46.71 (CH2Cl), 64.56 (2 CH2), 113.08 (C-5), 113.86 (C-2), 121.21 (C-6), 129.96 (C-1), 148.81 (C-3), 148.93 (C-4); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C11H15ClO2: 214.0761; found: 214.0755.

2-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)acetonitrile (7): Benzyl chloride 6 (2.15 g (10.00 mmol)) was dissolved in dry DMF (20 mL). KCN (1.30 g (20.00 mmol)) was added and the suspension was stirred at 100 °C for 4 h. After that, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was mixed with water and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic phases were combined and washed with water and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, giving compound 7 as brown oil (1.95 g (95%)), which was used without further purification.

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)(hydroxyimino)acetonitrile (2): Sodium (0.37 g (12.00 mmol)) was dissolved in dry ethanol (15 mL) and then cooled to 0 °C with an ice bath. A solution of compound 7 (1.64 g (8.00 mmol)) in dry ethanol (10 mL) was added dropwise. Finally, isopentyl nitrite (1.41 g (12.00 mmol)) was added dropwise with a syringe through a septum. The ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture stirred at 25 °C for 20 h. The solution was diluted with ethyl acetate (80 mL) and washed with 2N HCl, 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo, giving compound 2 as white amorphous solid (1.86 g (99%)), which was used without further purification. IR = 3364, 1601, 1512, 1438, 1337, 1273, 1210, 1146, 1076, 1006, 845, 806; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.42 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.43 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 4.08 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.10 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.26 (dd, J = 8.5, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.33 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 15.16 (CH3), 15.19 (CH3), 65.75 (OCH2), 65.89 (OCH2), 110.68 (C-2), 111.04 (CN), 114.03 (C-5), 121.22 (C-6), 124.25 (C-1), 132.87 (C=NOH), 150.49 (C-3), 152.73 (C-4); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C12H14N2O3: 234.1004; found: 234.0996.

2-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-N’-hydroxy-2-(hydroxyimino)ethanimidamide (8): Oxime 2 (1.41 g (6.00 mmol)) was dissolved in methanol (18 mL) and a solution of NH2OH × HCl (0.50 g (7.20 mmol)) and NaHCO3 (0.61 g (7.20)) in water (9 mL) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 20 h and then the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was mixed with water (20 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic phases were combined dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, giving the raw amidoxime which was recrystallized in CH2Cl2 affording compound 8 as beige crystals (0.55 g (34%)). m.p. 148 °C. IR = 3370, 2981, 1661, 1598, 1516, 1444, 1393, 1270, 1201, 1144, 1040, 978, 810; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.33 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 6H, 2 CH3), 3.97–4.07 (m, 4H, 2 OCH2), 5.67 (s, 2H, NH2), 6.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.06 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.22 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 9.39 (s, 1H, NOH), 11.34 (s, 1H, NOH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.66 (CH3), 14.72 (CH3), 63.75 (OCH2), 63.81 (OCH2), 110.59 (C-2), 112.59 (C-5), 120.24 (C-6), 127.24 (C-1), 146.64 (C(=NOH)NH2), 147.66 (C-3), 149.20 (C-4), 149.22 (C=NOH); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C12H17N3O4: 267.1219; found: 267.1230.

4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-amine (9): Amidoxime 8 (0.80 g (3.00 mmol)) was dissolved in 2N NaOH (30 mL) and refluxed for 20 h. The formed precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried. The beige precipitate was pure product 9 (0.67 g (83%)) and was used without further purification. m.p. 155 °C. IR = 3374, 3322, 3244, 2984, 1593, 1536, 1501, 1396, 1327, 1305, 1253, 1215, 1141, 1111, 1041, 941, 862, 848, 815; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.35 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H, 2 CH3), 4.10 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 4H, 2 OCH2), 6.12 (s, 2H, NH2), 7.09 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5’-H), 7.25 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2’-H), 7.29 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6’-H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.62 (CH3), 14.66 (CH3), 63.85 (2 OCH2), 112.20 (C-2’), 113.25 (C-5’), 117.65 (C-1’), 120.60 (C-6’), 146.69 (C-4), 148.35 (C-3’), 149.87 (C-4’), 155.21 (C-3); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C12H15N3O3: 249.1113; found: 249.1099.

The general procedure for the synthesis of tertiary amines (18, 19, 22 and 23) is as follows: The respective heterocyclic amine (8.00 mmol), K2CO3 (8.00 mmol) and a catalytical amount of NaI (3.20 mmol) were added to a solution of the corresponding benzyl bromide (4.00 mmol) in dry acetonitrile (40 mL). The mixture was refluxed for 20 h. The suspension was cooled and filtered. The filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to dryness. The residue was mixed with water and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic phases were washed with 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo, giving pure amines 18, 19, 22 and 23, which were used without further purification.

Methyl 3-((pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzoate (18): The reaction of methyl 3-(bromomethyl)benzoate (0.92 g (4.00 mmol)), pyrrolidine (0.57 g (8.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (1.11 g (8.00 mmol)) and NaI (0.48 g (3.20 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (40 mL) gave compound 18 as pale brown oil (0.87 g (99%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

Methyl 3-((morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzoate (19): The reaction of methyl 3-(bromomethyl)benzoate (0.92 g (4.00 mmol)), morpholine (0.70 g (8.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (1.11 g (8.00 mmol)) and NaI (0.48 g (3.20 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (40 mL) gave compound 19 as yellow oil (0.93 g (99%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

Methyl 4-((pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzoate (22): The reaction of methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate (0.92 g (4.00 mmol)), pyrrolidine (0.57 g (8.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (1.11 g (8.00 mmol)) and NaI (0.48 g (3.20 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (40 mL) gave compound 22 as pale brown oil (0.82 g (94%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

Methyl 4-((morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzoate (23): The reaction of methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate (0.92 g (4.00 mmol)), morpholine (0.70 g (8.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (1.11 g (8.00 mmol)) and NaI (0.48 g (3.20 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (40 mL) gave compound 23 as yellow oil (0.90 g (96%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

2-(Hydroxyimino)-2-phenylacetonitrile (36): Sodium (0.37 g (12.00 mmol)) was dissolved in dry ethanol (15 mL) and then cooled to 0 °C with an ice bath. A solution of benzyl cyanide (0.94 g (8.00 mmol)) in dry ethanol (10 mL) was added dropwise. Finally, isopentyl nitrite (1.41 g (12.00 mmol)) was added dropwise with a syringe through a septum. The ice bath was removed and the reaction mixture stirred at 25 °C for 20 h. The solution was diluted with ethyl acetate (80 mL) and washed with 2N HCl, 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine. The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered and the solvent was removed in vacuo, giving compound 36 as yellow amorphous solid (1.15 g (98%)), which was used without further purification.

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

N’-Hydroxy-2-(hydroxyimino)-2-phenylethanimidamide (37): Oxime 36 (0.88 g (6.00 mmol)) was dissolved in methanol (18 mL) and a solution of NH2OH × HCl (0.50 g (7.20 mmol)) and NaHCO3 (0.61 g (7.20)) in water (9 mL) was added. The mixture was refluxed for 20 h and then the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was mixed with water (20 mL) and extracted with ethyl acetate. The organic phases were combined, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo, giving the raw amidoxime which was recrystallized in CH2Cl2 affording compound 37 as white crystals (0.25 g (23%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

4-Phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-amine (38): Amidoxime 37 (0.54 g (3.00 mmol)) was dissolved in 2N NaOH (30 mL) and refluxed for 20 h. The formed precipitate was filtered, washed with water and dried. The white precipitate was pure product 38 (0.17 g (36%)) and was used without further purification.

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

The general procedure for the synthesis of carboxylic acids (20, 21, 24 and 25) is as follows: To a solution of the respective methyl ester (3.00 mmol) in methanol (10 mL), 2N NaOH (9.0 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred at 25 °C for 20 h and then the reaction mixture was acidified with conc HCl to a pH of 6. The solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the residue was mixed with CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and sonicated for 5 min. The suspension was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to dryness, giving pure carboxylic acids 20, 21, 24 and 25, which were used without further purification.

3-((Pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzoic acid (20): The reaction of methyl ester 18 (0.66 g (3.00 mmol)) and 2N NaOH (9 mL) in methanol (10 mL) gave compound 20 as white foam (0.17 g (27%)). IR = 2927, 2597, 1613, 1567, 1455, 1381, 1263; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 2.12 (br, s, 4H, (CH2)2), 3.26 (br, 4H, N(CH2)2), 4.20 (br, s, 2H, ArCH2), 7.40 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.55 (br, 1H, 4-H), 8.07 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 8.50 (br, s, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 23.19 ((CH2)2), 52.71 (N(CH2)2), 58.49 (ArCH2), 128.33 (C-5), 130.39 (C-6), 130.75 (C-1), 132.47 (C-2), 132.55 (C-4), 136.70 (C-3), 170.88 (COOH); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C12H15NO2: 205.1103; found: 205.1088.

3-((Morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzoic acid (21): The reaction of methyl ester 19 (0.71 g (3.00 mmol)) and 2N NaOH (9 mL) in methanol (10 mL) gave compound 21 as white amorphous solid (0.64 g (97%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

4-((Pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzoic acid (24): The reaction of methyl ester 22 (0.66 g (3.00 mmol)) and 2N NaOH (9 mL) in methanol (10 mL) gave compound 24 as white foam (0.55 g (90%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

4-((Morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzoic acid (25): The reaction of methyl ester 23 (0.71 g (3.00 mmol)) and 2N NaOH (9 mL) in methanol (10 mL) gave compound 25 as yellow oil (0.62 g (94%)).

NMR data were in accordance with literature data [].

The general procedure for the synthesis of carboxamides (1, 10–17, 26–29) is detailed in the following subsections.

3.2.1. Method A

An ice-cooled suspension of NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil; 2.00 mmol) in dry DMF (14 mL) was mixed with aminofurazan 9 (1.00 mmol) and stirred for 20 min. Then, a solution of acid chloride (1.30 mmol) in dry DMF (2 mL) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 20 h. Afterward, the mixture was quenched with water at 0 °C and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, yielding the raw carboxamides 1 and 10–14, which were further purified by crystallization.

3.2.2. Method B

To an ice-cooled solution of carboxylic acid (1.50 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL), oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (1.90 mmol) was added dropwise under stirring. After 1 h, the ice bath was removed and the reaction batch was stirred 20 h at 25 °C in an atmosphere of Ar. Subsequently, the solvent was evaporated in vacuo and the crude acyl chloride was dissolved in dry DMF (9 mL). An ice-cooled suspension of NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil; 2.00 mmol) in dry DMF (14 mL) was mixed with aminofurazan 9 (1.00 mmol) and stirred for 20 min. Then, the solution of acyl chloride in dry DMF was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 48 h. Afterward, the mixture was quenched with water at 0 °C and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, yielding the raw carboxamides 16, 17 and 26–29, which were further purified by column chromatography or crystallization.

3.2.3. Method C

A solution of benzoic acid (1.50 mmol), N-hydroxysuccinimide (1.58 mmol) and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (1.50 mmol) was dissolved in dry THF (10 mL) and stirred at 25 °C for 20 h. The formed precipitate was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to dryness to obtain the crude NHS ester which was used without further purification. An ice-cooled suspension of NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil; 2.00 mmol) in dry DMF (14 mL) was mixed with aminofurazan 9 (1.00 mmol) and stirred for 20 min. Then, the solution of NHS ester in dry DMF (4 mL) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred at 60 °C for 20 h. Afterward, the mixture was quenched with water at 0 °C and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with 8% aq NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, yielding the raw carboxamide 15, which was further purified by crystallization.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-methylbenzamide (1): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-methylbenzoyl chloride (201 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 1 as white crystals (63 mg (17%)). m.p. 162 °C. IR = 3198, 2981, 1665, 1591, 1531, 1500, 1394, 1377, 1325, 1277, 1260, 1218, 1142, 1042, 940, 862, 810; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.20 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.32 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.40 (s, 3H, ArCH3), 3.90 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.05 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.32-7.37 (m, 2H, 2”-H, 6”-H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.6, 1H, 5-H), 7.49 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.79 (br, d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.82 (br, s, 1H, 2-H), 11.17 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.47 (CH3), 14.56 (CH3), 20.86 (ArCH3), 63.79 (2 OCH2), 111.68 (C-2”), 113.21 (C-5”), 116.92 (C-1”), 120.44 (C-6”), 125.17 (C-6), 128.52 (C-2), 128.61 (C-5), 132.22 (C-1), 133.41 (C-4), 138.13 (C-3), 148.10 (C-3”), 150.06 (C-3’), 150.33 (C-4”), 151.23 (C-4’), 166.78 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H21N3O4: 367.1532; found: 367.1526.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzamide (10): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), benzoyl chloride (183 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 10 as white crystals (81 mg (23%)). m.p. 199 °C. IR = 3212, 2980, 1660, 1591, 1530, 1501, 1468, 1395, 1378, 1324, 1275, 1258, 1216, 1141, 1040, 916, 852, 811; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.19 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.31 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.88 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.05 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.07 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.31 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 7.33 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.58 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, 3-H, 5-H), 7.68 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, 2-H, 6-H), 11.24 (br s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.45 (CH3), 14.57 (CH3), 63.78 (2 OCH2), 111.65 (C-2”), 113.19 (C-5”), 116.87 (C-1”), 120.43 (C-6”), 128.05 (C-2, C-6), 128.74 (C-3, C-5), 132.10 (C-1), 132.91 (C-4), 148.11 (C-3”), 149.95 (C-3’), 150.36 (C-4”), 151.24 (C-4’), 166.66 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C19H19N3O4: 353.1375; found: 353.1373.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-2-methylbenzamide (11): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 2-methylbenzoyl chloride (201 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 11 as white crystals (103 mg (28%)). m.p. 170 °C. IR = 3214, 2983, 1663, 1591, 1503, 1395, 1377, 1324, 1259, 1216, 1142, 1042, 918, 854, 803, 741, 687, 657, 618; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.28 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.34 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.34 (s, 3H, ArCH3), 3.99 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.08 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.11 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.33–7.37 (m, 4H, 2”-H, 3-H, 5-H, 6”-H), 7.45 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.65 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 6H), 11.12 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.61 (2 CH3), 19.56 (ArCH3), 63.84 (OCH2), 63.97 (OCH2), 112.06 (C-2”), 113.13 (C-5”), 116.96 (C-1”), 120.67 (C-6”), 125.79 (C-5), 127.89 (C-6), 130.92 (C-4), 131.10 (C-3), 133.97 (C-1), 136.63 (C-2), 148.21 (C-3”), 149.83 (C-3´), 150.34 (C-4”), 151.22 (C-4´), 168.70 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C19H21N3O4: 367.1532; found: 367.1526.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-2-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (12): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 2-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl chloride (271 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in methanol to yield compound 12 as white crystals (38 mg (9%)). m.p. 171 °C. IR = 3209, 2983, 1676, 1604, 1531, 1494, 1397, 1377, 1316, 1277, 1217, 1177, 1129, 1043, 921, 854, 811, 772, 651, 617; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.32 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.34 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 4.05 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.09 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.13 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.34 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 7.36 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.76-7.84 (m, 3H, 4-H, 5-H, 6-H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, 3-H), 11.46 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.61 (CH3), 14.64 (CH3), 63.84 (OCH2), 63.96 (OCH2), 112.37 (C-2”), 113.09 (C-5”), 116.52 (C-1”), 120.94 (C-6”), 123.52 (q, J = 274 Hz, CF3), 126.25 (q, J = 31.7 Hz, C-2), 126.71 (q, J = 4.9 Hz, C-3), 128.69 (C-6), 131.05 (C-4), 132.69 (C-5), 134.03 (m, C-1), 148.23 (C-3”), 149.00 (C-3’), 150.41 (C-4”), 150.72 (C-4’), 166.47 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H18F3N3O4: 421.1249; found: 421.1248.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethyl)benzamide (13): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl chloride (271 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 13 as white crystals (131 mg (31%)). m.p. 153 °C. IR = 3203, 1675, 1498, 1378, 1336, 1260, 1217, 1172, 1121, 1042, 815; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.19 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.32 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.90 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.06 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.08 (d, J =8.3 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.33 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 7.34 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.84 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 8.29 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 8.36 (s, 1H, 2-H), 11.53 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.40 (CH3), 14.56 (CH3), 63.77 (OCH2), 63.81 (OCH2), 111.72 (C-2”), 113.24 (C-5”), 116.83 (C-1”), 120.59 (C-6”), 123.82 (q, J = 272 Hz, CF3), 124.66 (q, J = 3.9 Hz, C-2), 129.33 (q, J = 4.4 Hz, C-4), 129.44 (q, J = 32.2 Hz, C-3), 130.18 (C-5), 132.27 (C-6), 133.21 (C-1), 148.11 (C-3”), 149.80 (C-3’), 150.36 (C-4”), 151.08 (C-4’), 165.25 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H18F3N3O4: 421.1249; found: 421.1242.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-fluorobenzamide (14): Method A: The reaction of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-fluorobenzoyl chloride (206 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 14 as beige crystals (186 mg (50%)). m.p. 250 °C. IR = 3216, 2983, 1663, 1591, 1505, 1364, 1275, 1215, 1142, 1039, 880, 857, 809; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.27 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.33 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.99 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.07 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.06 (d, J =8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.32 (td, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.48 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.6, 5.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.63 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.4 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.81-7.87 (m, 2H, 2-H, 2”-H), 7.93 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, 6-H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.60 (CH3), 14.66 (CH3), 63.76 (2 OCH2), 112.34 (C-2”), 113.08 (C-5”), 114.69 (d, J = 22.1 Hz, C-2), 117.25 (d, J = 21.2 Hz, C-4), 119.08 (C-1”), 120.60 (C-6”), 124.25 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, C-6), 129.87 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, C-5), 140.35 (C-1), 147.84 (C-3”), 149.66 (C-4”), 150.19 (C-4’), 155.35 (C-3’), 161.94 (d, J = 242 Hz, C-3), 166.84 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C19H18FN3O4: 371.1261; found: 371.1276.

3-Chloro-N-(4-(3,4-diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-4-methoxybenzamide (16): Method B: The reaction of 3-chloro-4-methoxybenzoic acid (280 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acid chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in toluene to yield compound 16 as white crystals (255 mg (61%)). m.p. 260 °C (decomp.). IR = 2978, 1663, 1600, 1501, 1470, 1395, 1360, 1271, 1215, 1142, 1057, 1040, 937, 855, 811; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.30 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.34 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.91 (s, 3H, OCH3), 4.02 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.07 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.06 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.92 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 8.05 (dd, J = 8.7, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 8.17 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, 2-H), 11.27 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.69 (2 CH3), 56.27 (OCH3), 63.72 (2 OCH2), 111.80 (C-5), 112.33 (C-2”), 112.99 (C-5”), 119.43 (C-1”), 120.18 (C-3), 120.55 (C-6”), 128.55 (C-6), 129.79 (C-2), 131.72 (C-1), 147.76 (C-3”), 149.48 (C-4”), 150.09 (C-4’), 153.07 (C-3’), 156.03 (C-4), 166.89 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H20ClN3O5: 417.1092; found: 417.1081.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-fluoro-4-methoxybenzamide (17): Method B: The reaction of 3-fluoro-4-methoxybenzoic acid (255 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acid chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in toluene to yield compound 17 as beige crystals (124 mg (31%)). m.p. 232 °C (decomp.). IR = 3199, 2982, 1663, 1615, 1500, 1469, 1396, 1377, 1327, 1286, 1217, 1140, 1040, 853, 802; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.25 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.33 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.92 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.96 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.07 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.06 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.27 (t, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.51 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.62 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.90 (s, 1H, 2-H), 11.29 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.55 (CH3), 14.63 (CH3), 56.23 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, OCH3), 63.74 (2 OCH2), 112.02 (C-2”), 113.06 (C-5, C-5”), 115.54 (d, J = 19.0 Hz, C-2), 118.23 (C-1”), 120.50 (C-6”), 125.30 (d, J = 3.1 Hz, C-6), 128.22 (C-1), 147.90 (C-3”), 149.86 (d, J = 23.6 Hz, C-4), 149.89 (C-4”), 150.61 (C-4’), 150.76 (d, J = 244 Hz, C-3), 153.19 (C-3’), 166.11 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H20FN3O5: 401.1387; found: 401.1380.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-4-((pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzamide (26): Method B: The reaction of carboxylic acid 20 (308 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acid chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in toluene to yield compound 26 as light yellow crystals (140 mg (32%)). m.p. 251 °C (decomp.). IR = 2973, 2788, 1584, 1471, 1365, 1271, 1246, 1201, 1141, 1091, 1038, 997, 937, 880, 854, 809; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.32 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.35 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.69 (br, s, 4H, (CH2)2), 2.43 (br, s, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.59 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 4.05 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.08 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.07 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 3-H, 5-H), 7.92 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 8.11 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2-H, 6-H), 8.24 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, 2”-H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.74 (CH3), 14.79 (CH3), 23.14 ((CH2)2), 53.54 (N(CH2)2), 59.54 (ArCH2), 63.68 (2 OCH2), 112.67 (C-2”), 112.86 (C-5”), 120.64 (C-1”), 120.72 (C-6”), 127.37 (C-3, C-5), 128.24 (C-2, C-6), 139.78 (C-1), 140.34 (C-4), 147.60 (C-3”), 149.12 (C-4”), 149.56 (C-4’), 158.93 (C-3’), 169.56 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C24H28N4O4: 436.2111; found: 436.2102.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-4-((morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (27): Method B: The reaction of carboxylic acid 25 (332 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acyl chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in toluene to yield compound 27 as pale yellow crystals (258 mg (57%)). m.p. 269 °C (decomp.). IR = 2977, 1585, 1499, 1472, 1360, 1271, 1202, 1141, 1109, 1035, 867; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.32 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.35 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.36 (br, s, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.49 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 3.58 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H, O(CH2)2), 4.05 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.08 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.07 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H, 3-H, 5-H), 7.92 (dd, J = 8.6, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 8.12 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, 2-H, 6-H), 8.23 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, 2”-H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.75 (CH3), 14.79 (CH3), 53.22 (N(CH2)2), 62.36 (ArCH2), 63.69 (2 OCH2), 66.24 (O(CH2)2), 112.66 (C-2”), 112.86 (C-5”), 120.64 (C-1”), 120.73 (C-6”), 127.86 (C-3, C-5), 128.28 (C-2, C-6), 138.60 (C-1), 140.08 (C-4), 147.61 (C-3”), 149.12 (C-4”), 149.56 (C-4’), 158.97 (C-3’), 169.47 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C24H28N4O5: 452.2060; found: 452.2043.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-((pyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)benzamide (28): Method B: The reaction of carboxylic acid 20 (308 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acid chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2/toluene/MeOH, 20:1:1) to yield compound 28 as yellow oil (262 mg (60%)). IR = 3212, 2974, 2799, 1661, 1591, 1500, 1473, 1395, 1377, 1259, 1217, 1140, 1041, 849, 800; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.40 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.46 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.78–1.81 (m, 4H, (CH2)2), 2.52–2.56 (m, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.69 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 4.04 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.11 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 6.91 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.9 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.25 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 7.42 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.57 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.75 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.87 (s, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.64 (CH3), 14.65 (CH3), 23.42 ((CH2)2), 54.20 (N(CH2)2), 60.09 (ArCH2), 64.44 (OCH2), 64.58 (OCH2), 112.36 (C-2”), 112.94 (C-5”), 117.28 (C-1”), 120.33 (C-6”), 126.40 (C-6), 127.82 (C-2), 128.92 (C-5), 132.39 (C-1), 133.45 (C-4), 140.34 (C-3), 148.88 (C-3’), 149.08 (C-3”), 149.83 (C-4’), 150.82 (C-4”), 165.69 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C24H28N4O4: 436.2111; found: 436.2086.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-((morpholin-4-yl)methyl)benzamide (29): Method B: The reaction of carboxylic acid 21 (332 mg (1.50 mmol)) and oxalyl dichloride 2 M in CH2Cl2 (0.95 mL (1.90 mmol)) in dry CH2Cl2 (14 mL) gave the raw acid chloride which was suspended in dry DMF (9 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in toluene to yield compound 29 as white crystals (113 mg (25%)). m.p. 199 °C. IR = 2978, 1605, 1502, 1468, 1361, 1271, 1209, 1141, 1114, 1036, 854; 1H NMR (CD3OD, 400 MHz) δ = 1.28 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.40 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 2.48 (br, s, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.58 (s, 2H, ArCH2), 3.70 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 4H, O(CH2)2), 3.94 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.09 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 6.98 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.43 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.64 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.6 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.72 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 8.00 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 8.03 (s, 1H, 2-H); 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) δ = 15.23 (2 CH3), 54.77 (N(CH2)2), 64.49 (ArCH2), 65.72 (OCH2), 65.76 (OCH2), 67.92 (O(CH2)2), 114.03 (C-2”), 114.47 (C-5”), 121.81 (C-1”), 122.20 (C-6”), 128.81 (C-6), 128.95 (C-5), 131.01 (C-2), 132.31 (C-4), 137.99 (C-3), 140.85 (C-1), 149.92 (C-3”), 151.48 (C-4”), 151.79 (C-4’), 160.84 (C-3’), 173.71 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C24H28N4O5: 452.2060; found: 452.2042.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-(trifluoromethoxy)benzamide (15): Method C: The reaction of 3-(trifluoromethoxy)benzoic acid (309 mg (1.50 mmol)), N-hydroxysuccinimide (182 mg (1.58 mmol)) and N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (310 mg (1.50 mmol)) in dry THF (10 mL) gave the raw NHS ester. It was suspended in dry DMF (4 mL) and added to a suspension of compound 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (14 mL), giving the raw carboxamide which was purified by recrystallization in CH2Cl2 to yield compound 15 as white crystals (136 mg (31%)). m.p. 145–147 °C. IR = 3209, 1675, 1590, 1501, 1378, 1260, 1216, 1170, 1042, 809, 633; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 400 MHz) δ = 1.19 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.32 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 3.90 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.05 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 7.06 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.39–7.44 (m, 2H, 2”-H, 6”-H), 7.63 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.68 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.96 (s, 1H, 2-H), 8.06 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 11.32 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6, 100 MHz) δ = 14.45, 14.62 (2 CH3), 63.72, 63.78 (2 OCH2), 111.79 (C-2”), 113.13 (C-5”), 117.50 (C-1”), 120.08 (q, J = 257 Hz, CF3), 120.50 (C-2), 120.56 (C-6”), 124.68 (C-4), 127.27 (C-6), 130.75 (C-5), 136.13 (C-1), 148.01 (C-3”), 148.34 (C-3’), 150.14 (C-4”), 150.84 (C-4’), 151.53 (C-3), 165.46 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C20H18F3N3O5: 437.1198; found: 437.1171.

3.2.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 31, 32, 34 and 35

Amino furazan 9 (1.00 mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of dry diethyl ether (4 mL) and dry benzene (16 mL). Dry pyridine (1.13 mmol) was added and then a solution of chloroacyl chloride (1.10 mmol) in dry diethyl ether (4 mL) was added dropwise. The mixture was refluxed for 20 h and then the solvent was evaporated in vacuo. The residue was mixed with water (35 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, yielding the raw carboxamide which was used without further purification. It was dissolved in dry acetonitrile (20 mL), and the respective amine (2.00 mmol), K2CO3 (2.00 mmol) and a catalytical amount of NaI (0.65 mmol) were added. The mixture was stirred at 70 °C for 20 h and then cooled to ambient temperature. The suspension was filtered and the filtrate was evaporated in vacuo to dryness. The residue was mixed with water (20 mL) and the aqueous phase was extracted with CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with 8% aqueous NaHCO3 and brine, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and filtered, and the solvent was evaporated in vacuo, yielding the carboxamide, which was purified by column chromatography.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-2-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)acetamide (31): The reaction of amino furazan 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), chloroacetyl chloride (124 mg (1.10 mmol)) and pyridine (89 g (1.13 mmol)) in a mixture of dry diethyl ether (8 mL) and dry benzene (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide. This was mixed with pyrrolidine (142 mg (2.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (276 mg (2.00 mmol)) and NaI (97 mg (0.65 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (20 mL), giving the tertiary amine which was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2/MeOH, 100:1) to yield compound 31 as pale yellow amorphous solid (87 mg (24%)). IR = 2983, 1726, 1593, 1545, 1519, 1461, 1256, 1216, 1149, 1042, 844, 811; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.48 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.50 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), 1.79–1.85 (m, 4H, (CH2)2), 2.68–2.73 (m, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.38 (s, 2H, CH2CO), 4.13 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 4.17 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H, OCH2), 6.97 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.12 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.22 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 9.73 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.63 (CH3), 14.70 (CH3), 24.04 ((CH2)2), 54.62 (N(CH2)2), 58.76 (CH2), 64.63, 64.88 (2 OCH2), 113.07 (C-5”), 113.13 (C-2”), 117.07 (C-1”), 120.06 (C-6”), 147.54 (C-3’), 148.36 (C-4’), 149.53 (C-3”), 151.07 (C-4”), 168.87 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C18H24N4O4: 360.1797; found: 360.1782.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-2-(morpholin-4-yl)acetamide (32): The reaction of amino furazan 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), chloroacetyl chloride (124 mg (1.10 mmol)) and pyridine (89 g (1.13 mmol)) in a mixture of dry diethyl ether (8 mL) and dry benzene (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide. It was mixed with morpholine (174 mg (2.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (276 mg (2.00 mmol)) and NaI (97 mg (0.65 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (20 mL), giving the tertiary amine which was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2/MeOH, 40:1) to yield compound 32 as white amorphous solid (233 mg (62%)). IR = 3326, 2982, 1731, 1595, 1542, 1520, 1462, 1328, 1254, 1216, 1146, 1112, 1041, 1009, 867, 809; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.46–1.53 (m, 6H, 2 CH3), 2.64 (t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H, N(CH2)2), 3.24 (s, 2H, 2-H), 3.68 (br, t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H, O(CH2)2), 4.12–4.20 (m, 4H, 2 OCH2), 7.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.23 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 9.75 (br, s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.62 (CH3), 14.71 (CH3), 53.79 (N(CH2)2), 61.76 (C-2), 64.69, 65.01 (2 OCH2), 66.85 (O(CH2)2), 113.05 (C-5”), 113.57 (C-2”), 116.84 (C-1”), 120.00 (C-6”), 147.42 (C-3’), 148.30 (C-4’), 149.65 (C-3”), 151.29 (C-4”), 167.80 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C18H24N4O5: 376.1747; found: 376.1743.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)propanamide (34): The reaction of amino furazan 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-chloropropanoyl chloride (140 mg (1.10 mmol)) and pyridine (89 g (1.13 mmol)) in a mixture of dry diethyl ether (8 mL) and dry benzene (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide. It was mixed with pyrrolidine (142 mg (2.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (276 mg (2.00 mmol)) and NaI (97 mg (0.65 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (20 mL), giving the tertiary amine which was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2/MeOH, 15:1) to yield compound 34 as yellow amorphous solid (300 mg (80%)). IR = 2977, 1719, 1551, 1476, 1434, 1396, 1323, 1274, 1250, 1217, 1149, 1043, 916, 845; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.46–1.51 (m, 6H, 2 CH3), 1.53–1.57 (m, 4H, (CH2)2), 2.51–2.56 (m, 4H, N(CH2)2), 2.63 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H, 2-H), 2.82 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 2H, 3-H), 4.10–4.18 (m, 4H, 2 OCH2), 6.96 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.11 (dd, J = 8.3, 1.8 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.19 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 12.02 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.68 (CH3), 14.72 (CH3), 23.35 ((CH2)2), 34.06 (C-2), 51.07 (C-3), 53.08 (N(CH2)2), 64.89, 64.65 (2 OCH2), 112.95 (C-5”), 113.50 (C-2”), 117.36 (C-1”), 120.46 (C-6”), 148.42 (C-3’), 148.71 (C-4’), 149.27 (C-3”), 150.88 (C-4”), 170.64 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C19H26N4O4: 374.1954; found: 374.1973.

N-(4-(3,4-Diethoxyphenyl)-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)-3-(morpholin-4-yl)propanamide (35): The reaction of amino furazan 9 (249 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-chloropropanoyl chloride (140 mg (1.10 mmol)) and pyridine (89 g (1.13 mmol)) in a mixture of dry diethyl ether (8 mL) and dry benzene (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide. It was mixed with morpholine (174 mg (2.00 mmol)), K2CO3 (276 mg (2.00 mmol)) and NaI (97 mg (0.65 mmol)) in dry acetonitrile (20 mL), giving the tertiary amine which was purified by column chromatography (silica gel, CH2Cl2/MeOH, 40:1) to yield compound 35 as white amorphous solid (223 mg (57%)). IR = 3205, 2978, 1677, 1537, 1472, 1375, 1274, 1215, 1142, 1119, 1042, 870, 814; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 1.48 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 6H, 2 CH3), 2.49 (br, t, J = 4.6 Hz, 4H, N(CH2)2), 2.64 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, 2-H), 2.72 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, 3-H), 3.36–3.41 (m, 4H, O(CH2)2), 4.10–4.17 (m, 4H, 2 OCH2), 6.96 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H, 5”-H), 7.15 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.1 Hz, 1H, 6”-H), 7.19 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, 2”-H), 11.28 (br, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 14.62 (CH3), 14.70 (CH3), 31.56 (C-2), 52.70 (N(CH2)2), 53.56 (C-3), 64.63 (OCH2), 64.98 (OCH2), 66.17 (O(CH2)2), 113.09 (C-5”), 113.56 (C-2”), 117.09 (C-1”), 120.83 (C-6”), 148.22 (C-3’), 148.95 (C-4’), 149.28 (C-3”), 151.14 (C-4”), 170.19 (C=O); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C19H26N4O5: 390.1903; found: 390.1892.

3-Methyl-N-(4-phenyl-1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-yl)benzamide (39): Method A: The reaction of compound 38 (161 mg (1.00 mmol)), 3-methylbenzoyl chloride (201 mg (1.30 mmol)) and NaH (60% dispersion in mineral oil) (80 mg (2.00 mmol)) in dry DMF (16 mL) gave the raw carboxamide which was purified by column chromatography (aluminium oxide basic, cyclohexane/ethyl acetate, 3:1) to yield compound 39 as white amorphous solid (75 mg (27%)). IR = 3288, 1663, 1588, 1566, 1521, 1481, 1383, 1284, 885, 807; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ = 2.41 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.38 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 5-H), 7.42 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 4-H), 7.45–7.53 (m, 3H, 3”-H, 4”-H, 5”-H), 7.63 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, 6-H), 7.69 (s, 1H, 2-H), 7.70 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H, 2”-H, 6”-H), 8.29 (s, 1H, NH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ = 21.32 (CH3), 124.45 (C-6), 125.29 (C-1”), 127.57 (C-2”, C-6”), 128.39 (C-2), 128.88 (C-5), 129.32 (C-3”, C-5”), 130.81 (C-4”), 131.99 (C-1), 133.95 (C-4), 139.13 (C-3), 148.73 (C-3’), 149.94 (C-4’), 165.38 (CO); HRMS (EI+) calcd for C16H13N3O2: 279.1008; found: 279.0997.

3.3. Biological Tests

3.3.1. In Vitro Microplate Assay against P. falciparum

In vitro activity against erythrocytic stages of P. falciparum was determined using a 3H-hypoxanthine incorporation assay [,], using the drug-sensitive NF54 strain [] or the chloroquine- and pyrimethamine-resistant K1 strain []. Chloroquine (Sigma C6628) was used as standard. Compounds were dissolved in DMSO at 10 mg/mL and added to parasite cultures incubated in RPMI 1640 medium without hypoxanthine, supplemented with HEPES (5.94 g/L), NaHCO3 (2.1 g/L), neomycin (100 U/mL), Albumax (5 g/L) and washed human red cells A+ at 2.5% hematocrit (0.3% parasitemia). Serial drug dilutions of 11 3-fold dilution steps covering a range from 100 to 0.002 μg/mL were prepared. The 96-well plates were incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37 °C; 4% CO2, 3% O2, 93% N2. After 48 h, 0.05 mL of 3H-hypoxanthine (=0.5 μCi) was added to each well of the plate. The plates were incubated for a further 24 h under the same conditions. The plates were then harvested with a Betaplate cell harvester (Wallac, Zurich, Switzerland). The red blood cells were transferred onto a glass fiber filter and washed with distilled water. The dried filters were inserted into a plastic foil with 10 mL of scintillation fluid and counted in a Betaplate liquid scintillation counter (Wallac, Zurich, Switzerland). IC50 values were calculated from sigmoidal inhibition curves by linear regression [] using Microsoft Excel. Artemisinin and chloroquine were used as control. Dose-response curves of measured compounds and activities with standard deviation values are available in Supplementary Materials Section (Figures S24–S41 and Table S1).

3.3.2. In Vitro Cytotoxicity with L-6 Cells

Assays were performed in 96-well microtiter plates, each well containing 0.1 mL of RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% L-glutamine (200 mM) and 10% fetal bovine serum and 4000 L-6 cells (a primary cell line derived from rat skeletal myoblasts) [,]. Serial drug dilutions of 11 3-fold dilution steps covering a range from 100 to 0.002 μg/mL were prepared. After 70 h of incubation, the plates were inspected under an inverted microscope to assure the growth of the controls and sterile conditions. Then, 0.01 mL of Alamar Blue was then added to each well and the plates incubated for another 2 h. Then, the plates were read with a Spectramax Gemini XS microplate fluorometer (Molecular Devices Cooperation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using an excitation wavelength of 536 nm and an emission wavelength of 588 nm. The IC50 values were calculated by linear regression [] from the sigmoidal dose inhibition curves using SoftmaxPro software (Molecular Devices Cooperation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Podophyllotoxin (Sigma P4405) was used as control.

3.3.3. Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay (PAMPA)

The PAMPA was performed using a 96-well precoated Corning Gentest PAMPA plate at a pH of 7.4. The PAMPA plate system consists of a donor plate and an acceptor plate. When both plates are coupled, each well is divided into two chambers that are separated by a lipid–oil–lipid trilayer constructed in a porous filter. Stock solutions (10 mM) of each compound were prepared in DMSO and then further diluted to a concentration of 200 µM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4. The compound dissolved in PBS was then added to the donor plate and pure PBS was added to the acceptor plate. Four replicates of each compound and negative control (PBS) were transferred into different wells of the donor plate. Both plates were coupled and left at room temperature for 5 h. Then, the plates were separated, and the solutions of each donor well and acceptor well were transferred to 96-well UV-Star Microplates (Greiner Bio-One). The UV absorbance of compounds in donor wells and acceptor wells were analyzed by a SpectraMax M3 UV plate reader (Molecular Devices). The concentrations were received from a calibration curve for each substance. The plates were analyzed at a wavelength where the R2 value of the calibration curve was higher than 0.99 []. The effective permeability (Pe) was calculated as shown in the following Equations (1)–(3):

where:

Pe—effective permeability;

S—filter area (0.3 cm2);

VD—donor well volume;

VA—acceptor well volume;

t—incubation time (14,400 s);

cA(t)—concentration of compound in acceptor well at time t;

cequ—equilibrium concentration.

where:

cD(t) —concentration of compound in donor well at time t.

Recovery of compounds from donor and acceptor wells (mass retention) was calculated as shown in the equation below. Data were only accepted when recovery exceeded 70%.

where:

R—mass retention (%);

cD(t)—concentration of compound in donor well at time t;

cA(t)—concentration of compound in acceptor well at time t;

c0—initial concentration of compound in donor well;

VD—donor well volume;

VA—acceptor well volume.

3.3.4. Ligand Efficiency (LE)

Ligand efficiency was calculated as shown in the following Equation (4) []:

where:

LE—ligand efficiency;

HA—number of heavy atoms;

pIC50—negative logarithm of IC50.

4. Conclusions

This paper deals with the synthesis and antiplasmodial activities of a series of new 4-substituted N-acyl derivatives of 1,2,5-oxadiazol-3-amines. The substitution of the phenyl ring in ring position 4 of the furazan ring has a remarkable impact on the antiplasmodial activity. A compound with an unsubstituted ring was practically ineffective against both strains of P. falciparum, whereas its 3,4-diethoxy analog was active in low nanomolar concentration. Moreover, the activity strongly depended on the nature of the acyl moiety. Benzoyl derivatives were much more active than their alkanoyl analogs. Substitution of the phenyl ring strongly influenced the activity depending on the substituent and its ring position (Scheme 6). The most promising derivative 13 with a 3-(trifluoromethyl) group was highly active against the chloroquine-sensitive strain NF54 but even more active against the multiresistant K1 strain of P. falciparum. Like artemisinin, it possessed activity against this strain in low nanomolar concentration. Compared to the parent compound, it showed improved permeability. Further investigations should reveal if the (3,4-dimethoxyphenyl) substitution is already the optimum in ring position 4 of the furazan ring.

Scheme 6.

Summary of SARs of benzoyl derivatives.

Supplementary Materials

The following materials are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ph14050412/s1. Figures S1–S23. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra for compounds 6, 2, 8, 9, 20, 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39. Figures S24–S41. Dose-response curves of compounds 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39 against P.f. NF54, P.f. K1 and L-6 cells. Table S1. Activities with standard deviation values of compounds 1, 10–17, 26–29, 31, 32, 34, 35 and 39 against P. falciparum NF54, P. falciparum K1 and L-6 cells, expressed as IC50 (µM).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.H. and R.W.; investigation, T.H., P.H., J.D., W.S., R.S., M.K., P.M. and R.W.; methodology T.H. and P.H; data curation, T.H., P.H., J.D., W.S., R.S., M.K., P.M. and R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H., P.H. and R.W.; writing—review and editing, T.H., P.H. and R.W.; supervision, R.W.; project administration, P.H. and R.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Open Access Funding by the University of Graz.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- WHO. World Malaria Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Talapko, J.; Škrelc, I.; Alebić, T.; Jukić, M.; Včev, A. Malaria: The Past and the Present. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsrichanalai, C.; Pickard, A.L.; Wernsdorfer, W.H.; Meshnick, S.R. Epidemiology of drug resistant malaria. Lancet Infect. Des. 2002, 2, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanboonkunupakarn, B.; White, N.J. The threat of antimalarial drug resistance. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2016, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashley, E.A.; Dhorda, M.; Fairhurst, R.M.; Amaratunga, C.; Lim, P.; Suon, S.; Sreng, S.; Anderson, J.M.; Mao, S.; Sam, B.; et al. Spread of Artemisinin Resistance in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Manna, S.; Saha, B.; Hati, A.K.; Roy, S. Novel pfkelch13 Gene Polymorphism Associates with Artemisinin Resistance in Eastern India. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Pluijm, R.W.; Tripura, R.; Hoglund, R.M.; Phyo, A.P.; Lek, D.; ul Islam, A.; Anvikar, A.R.; Satpathi, P.; Behera, P.K.; Tripura, A.; et al. Triple artemisinin-based combination therapies versus artemisinin-based combination therapies for uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria: A multicentre, open-label, randomized clinical trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pluijm, R.W.; Amaratunga, C.; Dhorda, M.; Dondorp, A.M. Triple Artemisinin-Based Combination Therapies for Malaria—A New Paradigm? Trends Parasitol. 2021, 37, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, E.G.; Korsik, M.; Todd, M.H. The past, present and future of anti-malarial medicines. Malar. J. 2019, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, P.J. Are three drugs for malaria better than two? Lancet 2020, 395, 1213–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Wells, T.N.C. The antimalarial pipeline. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2018, 42, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiguemde, W.A.; Shelat, A.A.; Garcia-Bustos, J.F.; Diagana, T.T.; Garno, F.-J.; Guy, R.K. Global Phenotypic Screening for Antimalarials. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, T.N.C.; van Huijsduijnen, R.H.; Van Voorhis, W.C. Malaria medicines: A glass half full? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 424–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Voorhis, W.C.; Adams, J.H.; Adelfio, R.; Ahyong, V.; Akabas, M.H.; Alano, P.; Alday, A.; Alemán Resto, Y.; Alsibaee, A.; Alzualde, A.; et al. Open Source Drug Discovery with the Malaria Box Compound Collection for Neglected Diseases and Beyond. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, J.; Corey, V.; Scherer, C.A.; Kato, N.; Comer, E.; Maetani, M.; Antonova-Koch, Y.; Reimer, C.; Gagaring, K.; Ibanez, M.; et al. A high-throughput luciferase-based assay for the discovery of therapeutics that prevent malaria. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 2, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janse, C.J.; Franke-Fayard, B.; Mair, G.R.; Ramesar, J.; Thiel, C.; Engelmann, S.; Matuschewski, K.; Van Gemert, G.J.; Sauerwein, R.W.; Waters, A.P. High efficiency transfection of Plasmodium berghei facilitates novel selection procedures. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006, 145, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucantoni, L.; Duffy, S.; Adjalley, S.H.; Fidock, D.A.; Avery, V.M. Identification of MMV Malaria Box Inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum Early-Stage Gametocytes Using a Luciferase-Based High-Throughput Assay. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 6050–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucantoni, L.; Avery, V. Whole-cell In Vitro screening for gametocytocidal compounds. Future Med. Chem. 2012, 4, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucantoni, L.; Fidock, D.A.; Avery, V.M. Luciferase-Based, High-Throughput Assay for Screening and Profiling Transmission-Blocking Compounds against Plasmodium falciparum Gametocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouffe, D.M.; Wree, M.; Du, A.Y.; Meister, S.; Li, F.; Patra, K.; Lubar, A.; Okitsu, S.L.; Flannery, E.L.; Kato, N.; et al. High-Throughput Assay and Discovery of Small Molecules that Interrupt Malaria Transmission. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fivelman, Q.L.; McRobert, L.; Sharp, S.; Taylor, C.J.; Saeed, M.; Swales, C.A.; Sutherland, C.J.; Baker, D.A. Improved synchronous production of Plasmodium falciparum gametocytes in vitro. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007, 154, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehane, A.M.; Ridgway, M.C.; Baker, E.; Kirk, K. Diverse chemotypes disrupt ion homeostasis in the malaria parasite. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 94, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, F.C.; Meyer-Fernandes, J.R.; Vieyra, A. The Functioning of Na+-ATPases from Protozoan Parasites: Are These Pumps Targets for Antiparasitic Drugs? Cells 2020, 9, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerscher, B.; Nzukou, E.; Kaiser, A. Assessment of deoxyhypusine hydroxylase as a putative, novel drug target. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Koschitzky, I.; Gerhardt, H.; Lämmerhofer, M.; Kohout, M.; Gehringer, M.; Laufer, S.; Pink, M.; Schmitz-Spanke, S.; Strube, C.; Kaiser, A. New insights into novel inhibitors against deoxyhypusine hydroxylase from Plasmodium falciparum: Compounds with an iron chelating potential. Amino Acids 2015, 47, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detterbeck, R.; Hesse, M. An Improved and Versatile Method for the Rapid Synthesis of Aryldihydrobenzofuran Systems by a Boron Tribromide-Mediated Cyclization Reaction. Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoto, H.; Imamiya, E.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kimura, H.; Sohda, T. Studies on Non-Thiazolidinedione Antidiabetic Agents. 1. Discovery of Novel Oxyiminoacetic Acid Derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull 2002, 50, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, E.; Porta, F.; Facchetti, G.; Galli, C.; Gelain, A.; Meneghetti, F.; Rimoldi, I.; Romeo, S.; Villa, S.; Ricci, C.; et al. Synthesis of new dithiolethione and methanethiosulfonate systems endowed with pharmaceutical interest. Arkivoc 2017, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, J.; Gui, C.; Zhang, L.; Qin, Y.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Shen, X.; Jiang, H. Discovering novel chemical inhibitors of human cyclophilin A: Virtual screening, synthesis, and bioassay. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 2209–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, L.J.; Farrell, K.D.; Akol, M.T.; Jones, G.H.; Tierny, M.M.; Kramer, H.B.; Pukala, T.L.; Bernardes, G.J.L.; Perkins, M.V.; Chalker, J.M. Norbornene probes for the study of cysteine oxidation. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 1220–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ahmad, Y.; Laurent, E.; Maillet, P.; Talab, A.; Teste, J.F.; Dokhan, R.; Tran, G.; Ollivier, R. New Benzocycloalkylpiperazines, Potent and Selective 5-HT1A Receptor Ligands. J. Med. Chem. 1997, 40, 952–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defilippi, A.; Sorba, G.; Calvino, R.; Garrone, A.; Gasco, A.; Orsetti, M. Potential Histamine H2-Receptor Antagonists: Analogues of Classical Antagonists Containing 4-Substituted-3-Aminofurazan Moieties. Arch. Pharm. 1988, 321, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Keserü, G.M.; Leeson, P.D.; Rees, D.C.; Reynolds, C.H. The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Murawski, A.; Patel, K.; Crespi, C.L.; Balimane, P.V. A Novel Design of Artificial Membrane for Improving the PAMPA Model. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Bao, H.; Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y. Highly chemoselective hydrogenation of active benzaldehydes to benzyl alcohols catalyzed by bimetallic nanoparticles. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 6460–6462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provencher, L.; Wynn, H.; Jones, J.B.; Krawczyk, A.R. Enzymes in organic synthesis 51. Probing the dimensions of the large hydrophobic pocket of the active site of pig liver esterase. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 1993, 4, 2025–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, R.; Xu, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; He, Q.; Hu, Y. Design, synthesis and AChE inhibitory activity of indanone and aurone derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Kanai, T.; Imai, S. Novel Five-Membered Ring Compound. European Patent EP2272835 A1, 1 December 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Berne, S.; Kovačič, L.; Sova, M.; Kraševec, N.; Gobec, S.; Križaj, I.; Komel, R. Benzoic acid derivatives with improved antifungal activity: Design, synthesis, structure–activity relationship (SAR) and CYP53 docking studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 4264–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, S.-J.; Zhang, S.; Mao, S.; Xie, X.-X.; Xiao, X.; Xin, M.-H.; Xuan, W.; He, Y.-Y.; Cao, Y.-X.; Zhang, S.-Q. Combination of 4-anilinoquinazoline, arylurea and tertiary amine moiety to discover novel anticancer agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohle, S.D.; Perepichka, I. A New Synthetic Route to 3-Oxo-4-amino-1,2,3-oxadiazole from the Diazeniumdiolation of Benzyl Cyanide: Stable Sydnone Iminium N-Oxides. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 1621–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneux, A.R.; Meier, R. Aminofuroxane. 1. Synthese und Struktur. Helv. Chim. Acta 1970, 53, 1883–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]