Abstract

The use of plants as therapeutic agents is part of the traditional medicine that is practiced by many indigenous communities in Ecuador. The aim of this study was to update a review published in 2016 by including the studies that were carried out in the period 2016–July 2021 on about 120 Ecuadorian medicinal plants. Relevant data on raw extracts and isolated secondary metabolites were retrieved from different databases, resulting in 104 references. They included phytochemical and pharmacological studies on several non-volatile compounds, as well as the chemical composition of essential oils (EOs). The tested biological activities are also reported. The potential of Ecuadorian plants as sources of products for practical applications in different fields, as well the perspectives of future investigations, are discussed in the last part of the review.

1. Introduction

The geographic location of Ecuador, together with its geological features, makes the country’s biodiversity one of the richest in the world. Ecuador is, indeed, considered among the 17 megadiverse countries, accounting for about 10% of the entire world plant species, and every year new plants are discovered and added to the long list of the species already known. This fact makes Ecuador an invaluable source of potentially new natural products of biological and pharmaceutical interest, such as carnosol, tiliroside [1], and dehydroleucodine (DL) [2]. Moreover, most plants are considered to be medicinal, where they are a fundamental part of the health systems of several Ecuadorian ethnic groups [3]. The knowledge of traditional healer practitioners has been maintained over hundreds or even thousands of years [4]. Therefore, herbal remedies have gained acceptance thanks to the apparent efficacy and safety of plants over the centuries [5]. As a result, several doctors, especially in government intercultural health districts, practice integrated forms of modern and traditional medicine nowadays.

Scientific evidence of the therapeutic efficacy and absence of toxicity in Ecuadorian medicinal plants and their products has started to be collected only in the last few decades by the researchers of several groups in different Ecuadorian Universities. This scientific activity has increased dramatically in recent years, thanks to the support of the Ecuadorian people and government authorities, who consider the sustainable use of biodiversity resources a possible source of economic wealth.

This review gives a comprehensive analysis of recent phytochemical and biologically oriented studies that were carried out on Ecuadorian medicinal plants and is focused on the potential relationships between traditional uses and pharmacological effects, assessing the therapeutic potential of natural remedies. This review completes the information that was provided by our group in 2016 [3]. Since then, more than 100 scientific articles have been published concerning phytochemical and pharmacological studies of more than 120 plants belonging to 42 different botanical families. In addition, a few naturally derived products have been patented [6]. Moreover, traditional natural preparations, such as Colada morada, which is consumed on the Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) [7], and Horchata lojana, which is a typical beverage that is made of a mixture of medicinal and aromatic plants consumed by the people of southern Ecuador [8,9,10], have received great attention. Other typical preparations are an infusion of guaviduca from Piper carpunya Ruiz & Pav. [11], which is a traditional drink of the Amazonian people, and the infusion of Ilex guayusa Loes., which is an emblematic tree of the Amazon Region of Ecuador that is widely used in folk medicine, ritual ceremonies, and for making industrial beverages [12,13].

Many of the scientific articles mentioned in this review refer to studies that were carried out on plants and traditional preparations from southern Ecuador, especially from the province of Loja (Figure 1), which has a long tradition in exporting medicinal plants of great importance for human health, such as quina (Cinchona spp.) and condurango (Marsdenia condurango Rchb.f.).

Figure 1.

Provinces of Ecuador.

Possible future research directions are also discussed in this review. In addition, the therapeutic potential of some herbal products for the development of new drugs was indicated.

2. Literature Search Strategies and Sources

Relevant data on medicinal plants from Ecuador were retrieved using the keywords “medicinal plants from Ecuador,” “pharmacology,” “toxicity,” “phytochemistry,” and “biological studies” in different databases, including Pubmed, SciFinder, Springer, Elsevier, Wiley, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. The search range was 2016–July 2021. The plant names and authorities were checked with the database WFO (2021): World Flora Online, published on the Internet at http://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 25 September 2021). Data contained in Doctorate and Master’s theses were not considered. Articles on specific studies of Andean or Amazonian foods and fruits were not analyzed.

3. Phytochemical and Biological Activity Data

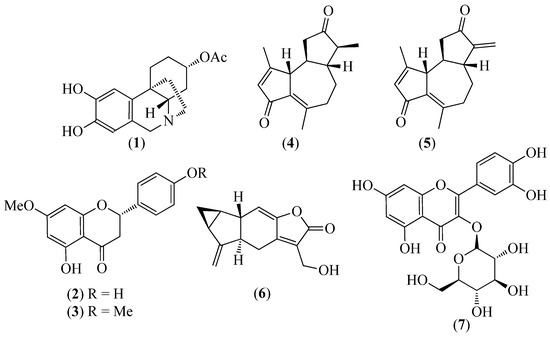

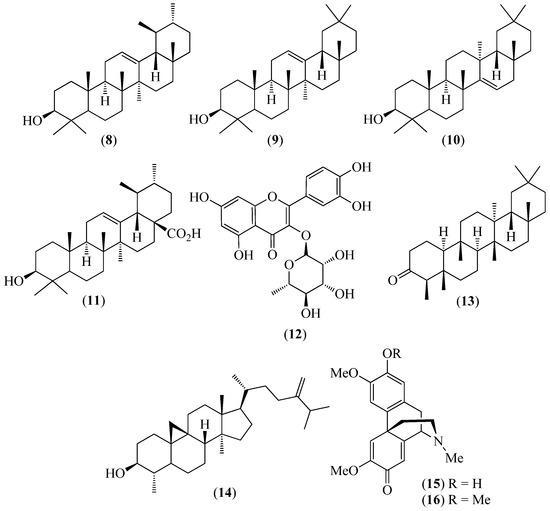

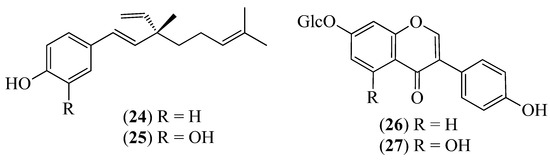

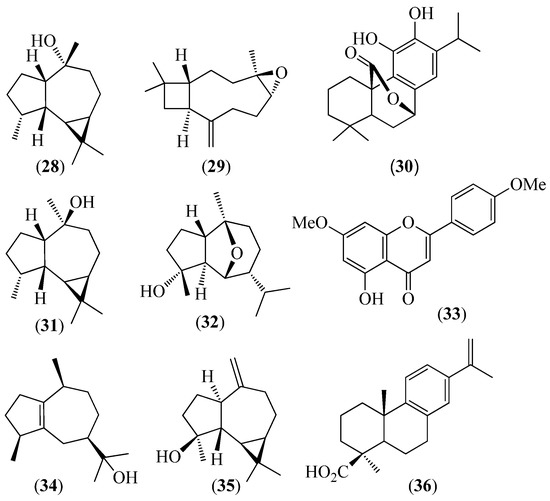

The literature information is summarized in Table 1, where the plants, in alphabetical order, were grouped in their corresponding botanical family. For each species, the vernacular name and some botanical information, when available, are indicated, together with the traditional use and the phytochemical and the biological activity data when available. The structures of some characteristic compounds are reported in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Table 1.

Literature on Ecuadorian medicinal plants in the period 2016–July 2021.

Figure 2.

Structures of compounds 1 from Pseudodranassa spp., 2 and 3 from Baccharis obtusifolia, 4 and 5 from Gynoxis verrucosa, 6 from Hedyosmum racemosum, and 7 from Clusia latipes.

Figure 3.

Structures of compounds 8–12 from Bejaria resinosa and 13–16 from Croton ferrugineus.

Figure 4.

Structures of compounds 17–23 from Croton thurifer.

Figure 5.

Structures of compounds 24–27 from Otholobium mexicanum.

Figure 6.

Structures of compounds 28 and 29 from Lepechinia heteromorpha; 30–33 from L. mutica; 28–30 and 34 from L. paniculata; and 33, 35, and 36 from L. radula.

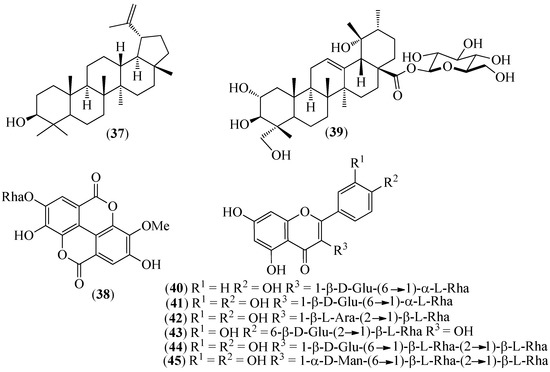

Figure 7.

Structures of compounds 37–39 from Grias neubertii and 40–45 from Gaiadendron punctatum.

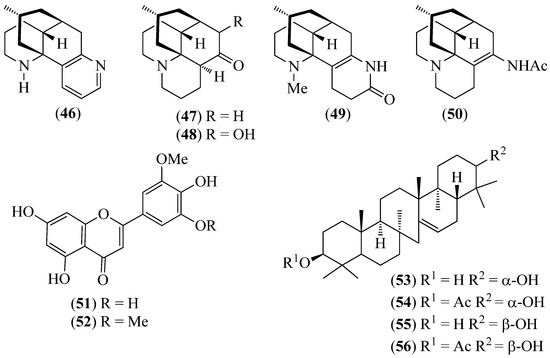

Figure 8.

Structures of compounds 46–50 from Huperzia compacta, H. columnaris, and H. tetragona; 51 and 52 from H. brevifolia and H. espinosana; and 53–56 from H. crassa.

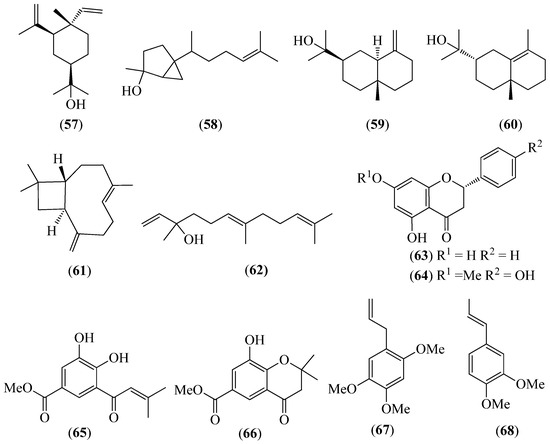

Figure 9.

Structures of compounds 57–60 from Piper barbatum; 61 and 62 from P. coruscans; 62 and 63 from P. ecuadorense; 64–66 from Piper lanceifolium; and 61, 62, 67 and 68 from P. pubinervulum.

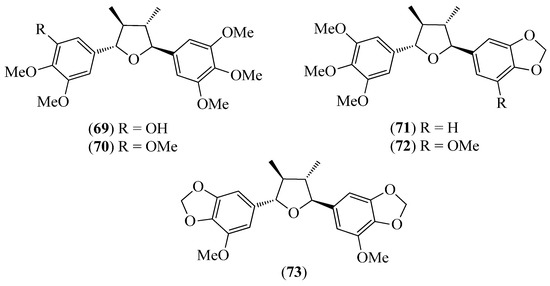

Figure 10.

Structures of compounds 69–73 from Piper subscutatum.

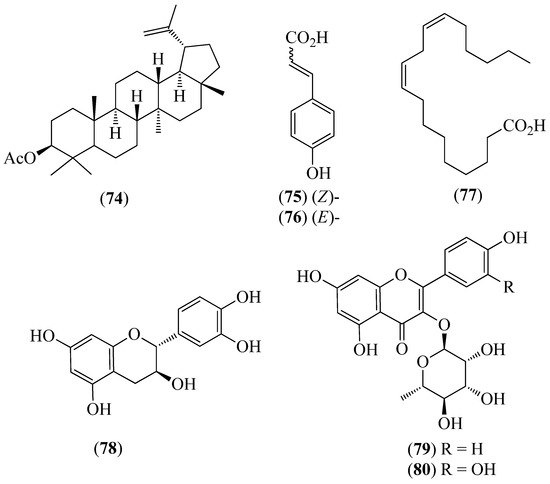

Figure 11.

Structures of compounds 74–80 from Muehlenbeckia tamnifolia.

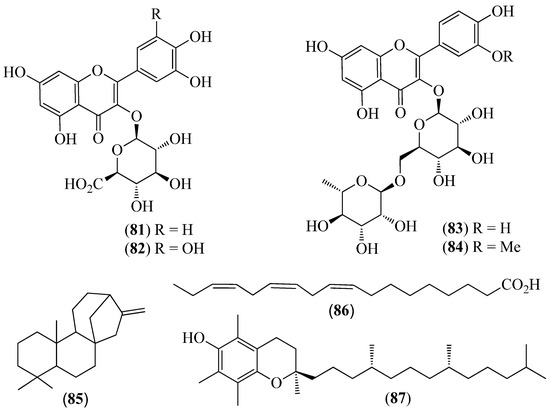

Figure 12.

Structures of compounds 81–84 from Oreocallis grandiflora and 85–87 from Roupala montana.

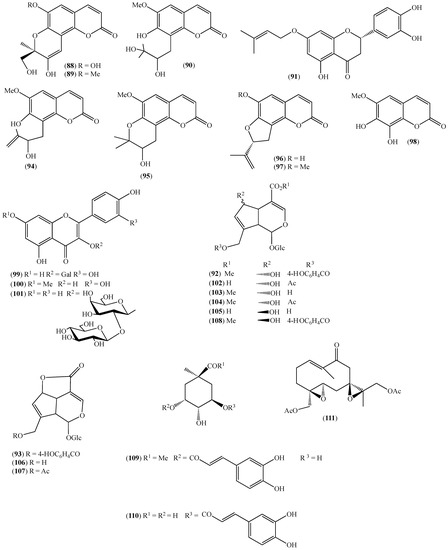

Figure 13.

Structures of compounds 88–110 from Arcytophyllum thymifolium and 111 from Siparuna echinata.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

The criteria for investigating most of the 120 species cited in this review appeared to be based mainly on an ethnobotanical and ethnopharmacological approach. Indeed, scientific evidence has often confirmed traditional uses; however, not rarely, tested biological activities were not strictly related to the traditional uses. On the other hand, plants were not collected with the aim of including extracts or products in high throughput screening programs. This strategy should, instead, be involved in future research projects since it is the only investigational system that is available for discovery programs that addresses the effects of natural products on selected enzymes and receptor targets emanating from molecular biology.

Essential oils (EOs) were the most frequently investigated products. In general, oil compositions were fully determined using GC/MS and GC/FID analyses; in addition, the oil enantiomer composition and odorant characteristics were often established. As regards the biological activities of the EOs, the activity of Renealmia thyrsoidea EO against Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [102], as well as the antifungal activity of Lepechinia radula [63], Ocimum campechianum [65], Piper ecuadorense [88], and Piper pubinervulum [90] EOs against Candida and Trichophyton strains, which are common causes of severe forms of candidiasis and dermatophytosis, are of great interest. Moreover, it is important to underline the strong acaricidal activity of a mixture of Bursera graveolens and Schinus molle EOs [44], the repellent effects of Dacryodes peruviana EO against mosquitoes [45], and the anti-termite properties of Ocotea quixos EO [70].

Thus, many EOs have the potential to be used not only as components of new perfumes due to the pleasing organoleptic properties but also as ingredients in the formulations of phytocosmetics, as well as antiseptic and insect repellent products. Moreover, essential oils should be screened in the future against clinically important bacteria and strains that are resistant to common antibiotics.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia affecting elderly people and it is associated with a loss of cholinergic neurons in parts of the brain. Cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) delay the breakdown of acylcholine that is released into synaptic clefts and so enhance cholinergic neurotransmission; thanks to these effects, ChEIs are considered efficacious at treating mild-to-moderate AD. In this context, the study of EO cholinesterase inhibitory activity is a relatively new area of research; in particular, the oil mechanisms of action have been poorly investigated so far. It is, therefore, of great interest that several EOs described in this review exhibited such inhibitory effects; in particular, the highly selective BuChE inhibitory activity exhibited by Clinopodium brownei [58], Coreopsis triloba [35], Myrcianthes myrsinoides [77], and Salvia leucantha [66] EOs is worthy of further studies. Equally interesting is the ChEI activity that was found for the flavonoid tiliroside, the diterpene carnosol (30) [1], and the alkaloids found in a few Phaedranassa species [17,18].

Concerning the non-volatile fractions and isolated compounds, the studies were less systematic and the compounds that are responsible for many plants’ activities are still unknown. Isolated compounds belonged to different biosynthetic families, including new ones, such as the high-molecular-weight alkaloids occurring in some Huperzia species, whose complete structures are, however, still unknown [4]. Extracts and isolated metabolites were subjected, almost routinely, to antiradical, e.g., DPPH, ABTS, and antioxidant (e.g., β-CLAMS and FRAP) assays. These tests are expected and, therefore, of little scientific significance for extracts containing phenolic compounds, unless high antioxidant products may be developed as phytotherapeutic agents or food supplements with health-promoting activities through the in vivo reduction of the oxidative stress. In this context, the high antioxidant activities of Baccharis obtusifolia [20], Oreocallis grandiflora [94], and Zingiber officinale [103] are worthy of note.

Oxidative stress induces the activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and subsequent inflammation; therefore, the in vitro antioxidant activity of a product is often considered good evidence of its anti-inflammatory property. However, a more scientifically sound approach should require the study of the molecular mechanisms that underline anti-inflammatory activities. In this context, the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) or the release of numerous pro-inflammatory mediators, such as COX-2, the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and interleukins IL-1β and IL-6, play a major role in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory disorders and, thus, serve as significant biomarkers for the assessment of the inflammatory process. The investigation of the anti-inflammatory effects of Salvia sagittata ethanolic extract [68] is a significant example of such an approach.

Several extracts and isolated compounds that were discussed in this review showed interesting inhibitory activity of the enzymes α-glucosidase and/or α-amylase. Indeed, pancreatic and intestinal glucosidases are the key enzymes of dietary carbohydrate digestion, and inhibitors of these enzymes may be effective in slowing glucose absorption to suppress postprandial hyperglycemia. In this context, it is significant to mention that the extracts and phenolic or flavonoid contents of Gaiadendron punctatum [73], Muehlenbeckia tamnifolia [93], Oreocallis grandiflora [19], and Otholobium mexicanum [56], as well as trans-tiliroside (22) [53], prenyloxy eriodictyol (92), and rhamnetin (101) [96], showed enzymatic inhibitory activity that was comparable or superior to acarbose, which is a drug that is currently used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Therefore, these results should promote studies on determining whether these hypoglycemic products can become sources of new antidiabetic drugs.

It is very well known that some of the most used drugs in cancer chemotherapy derive from natural products. In this context, the high antiproliferative effects shown by the extracts of some plants, such as Annona montana [15] and Grias neuberthii [72], against several human tumor cell lines are of great interest. Isolated compounds with potent in vitro cytotoxic properties include the flavonoid tricin (52) from Huperzia spp. [74], the triterpene ursolic acid (11) from Bejaria resinosa [51], and the sesquiterpene lactones onoseriolide (6) from Hedyosmum racemosus [48] and dehydroleucodine (5) from Gynoxis verrucosa [2]. The antileukemic properties of dehydroleucodine (5) and some derivatives were the objects of patents [6]. These findings should stimulate more systematic screening of the cytotoxic effects of Ecuadorian plants’ metabolites and the investigation of the mechanisms of the cell antiproliferative effects.

Considering the overall research activities that has been carried out so far in Ecuador on natural products, it can be concluded that little or scarce attention has been dedicated to the semi-synthesis of derivatives of isolated bioactive compounds with the aims to increase their activity, to study the structure–bioactivity relationships, and to explore the mechanisms of action and the signaling pathways that are involved in the biological activities. Even fewer efforts have been put into the synthesis of new chemical entities using computational approaches (in silico) to model the structures of natural products or to design completely new molecules. Indeed, research activities on these themes should be encouraged because they were demonstrated to be highly successful in the discovery of new bioactive compounds.

Finally, further studies, including those in vivo, are required to understand the relevance and selectivity of biological effects that have only been demonstrated in vitro so far. It is also important for practical applications to know potential acute and chronic toxicities, risks, and side effects of the plant-derived products. In fact, even raw extracts can be used as food additives and therapeutic remedies once the absence of toxicity has been demonstrated, the contents have been standardized, and the efficacy has been scientifically shown.

In conclusion, this review has clearly demonstrated the great potential of Ecuadorian plants as sources of products for different purposes and applications. Moreover, some guidelines for future research programs concerning possible sustainable uses of local therapeutic resources were indicated.

Ultimately, an important purpose of this paper is to stimulate more extensive studies on the rich medicinal flora of Ecuador.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A., A.I.S. and J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R., A.I.S., M.S. and C.A.; literature retrieval, A.I.S., M.S., J.R. and C.A.; review supervision and editing, G.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funding by Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja (UTPL) for open access publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ramírez, J.; Suarez, A.I.; Bec, N.; Armijos, C.; Gilardoni, G.; Larroque, C.; Vidari, G. Carnosol from Lepechinia mutica and tiliroside from Vallea stipularis: Two promising inhibitors of BuChE. Rev. Bras. Farm. 2018, 28, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, P.E.; Quave, C.L.; Reynolds, W.F.; Varughese, K.I.; Berry, B.; Breen, P.J.; Malagón, O.; Vidari, G.; Smeltzer, M.S.; Compadre, C.M. Corrigendum to Sesquiterpene lactones from Gynoxys verrucosa and their anti-MRSA activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 186, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malagón, O.; Ramírez, J.; Andrade, J.M.; Morocho, V.; Armijos, C.; Gilardoni, G. Phytochemistry and ethnopharmacology of the ecuadorian flora. A review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armijos, C.; Gilardoni, G.; Amay, L.; Lozano, A.; Bracco, F.; Ramírez, J.; Bec, N.; Larroque, C.; Finzi, P.V.; Vidari, G. Phytochemical and ethnomedicinal study of Huperzia species used in the traditional medicine of Saraguros in Southern Ecuador; AChE and MAO inhibitory activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 193, 546–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Traditional medicine. In Proceedings of the Fifty-Sixth World Health Assembly, Geneva, Switzerland, 31 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Compadre, C.M.; Ordonez, P.E.; Guzman, M.L.; Jones, D.E.; Malagon, O.; Vidari, G.; Crooks, P. Dehydroleucodine Derivatives and Uses Thereof. U.S. Patent Application No. 16/283, 20 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Armijos, C.; Valarezo, E.; Cartuche, L.; Zaragoza, T.; Finzi, P.V.; Mellerio, G.G.; Vidari, G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of Myrcianthes fragrans essential oil, a natural aromatizer of the traditional Ecuadorian beverage colada morada. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailon-Moscoso, N.; Tinitana, F.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.; Jaramillo-Velez, A.; Palacio-Arpi, A.; Aguilar-Hernandez, J.; Romero-Benavides, J.C. Cytotoxic, antioxidative, genotoxic and antigenotoxic effects of horchata, beverage of South Ecuador. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guevara, M.; Tejera, E.; Iturralde, G.A.; Jaramillo-Vivanco, T.; Granda-Albuja, M.G.; Granja-Albuja, S.; Santos-Buelga, C.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Álvarez-Suarez, J.M. Anti-inflammatory effect of the medicinal herbal mixture infusion, horchata, from southern Ecuador against LPS-induced cytotoxic damage in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 131, 110594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armijos, C.; Matailo, A.; Bec, N.; Salinas, M.; Aguilar, G.; Solano, N.; Calva, J.; Ludeña, C.; Larroque, C.; Vidari, G. Chemical composition and selective BuChE inhibitory activity of the essential oils from aromatic plants used to prepare the traditional Ecuadorian beverage horchata lojana. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 263, 113162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Rivera, J.; Coronel, E.; Barzallo, M.; Calva, J.; Cartuche, L.; Meneses, M. Study of volatile secondary metabolites present in Piper carpunya leaves and in the traditional ecuadorian beverage Guaviduca. Plants 2021, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Ruiz, A.; Baenas, N.; González, A.M.B.; Stinco, C.M.; Melendez-Martinez, A.J.; Moreno, D.A.; Ruales, J. Guayusa (Ilex guayusa L.) new tea: Phenolic and carotenoid composition and antioxidant capacity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3929–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radice, M.; Cossio, N.; Scalvenzi, L. Ilex guayusa: A systematic review of its traditional uses, chemical constituents, biological activities and biotrade opportunities. In Proceedings of the MOL2NET 2016, International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences, Basel, Switzerland, 15 January–15 December 2016, 2nd ed.; MDPI SciForum: Basel, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rey-Valeirón, C.; Pérez, K.; Guzmán, L.; López-Vargas, J.; Valarezo, E. Acaricidal effect of Schinus molle (Anacardiaceae) essential oil on unengorged larvae and engorged adult females of Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2018, 76, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailon-Moscoso, N.; Benavides, J.C.R.; Orellana, M.I.R.; Ojeda, K.; Granda, G.; Ratoviski, E.A.; Ostrosky-Wegman, P. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of extracts from Annona montana M. fruit. Food Agric. Immunol. 2016, 27, 559–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinueza, D.; Portero, S.; Pilco, G.; García, M.; Acosta, K.; Abdo, S. In vitro anti-inflammatory and cytotoxicity of Crinum x amabile grown in Ecuador. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, R.; Tallini, L.R.; Salazar, C.; Osorio, E.H.; Montero, E.; Bastida, J.; Oleas, N.H.; León, K.A. Chemical profiling and cholinesterase inhibitory activity of five Phaedranassa herb. (Amaryllidaceae) species from Ecuador. Molecules 2020, 25, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-León, K.; Inca, K.; Tallini, L.R.; Osorio, E.H.; Robles, J.; Bastidas, J.; Oleas, N. Alkaloids of Phaedranassa dubia (Kunth) J.K. Macbr and Phaedranassa brevifolia Meerow (Amaryllidaceae) from Ecuador and its cholinesterase inhibitory activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 136, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo-Fierro, X.; Riascos, S.O. In vitro hypoglycemic and antioxidant activities of some medicinal plants used in treatment of diabetes in Southern Ecuador. Axioma 2018, 1, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijos, C.P.; Meneses, M.A.; Guamán-Balcázar, M.C.; Cuenca, M.; Suárez, A.I. Antioxidant properties of medicinal plants used in the Southern Ecuador. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7, 2803–2812. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Flores, V.; Chiriboga-Pazmiño, X.; Miño-Cisneros, P.; Luzuriaga- Quichimbo, C. Phytochemistry and toxicologic study of native plants of the Ecuadorian rain forest. CU 2021, 14, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, R.-Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Corke, H. Health benefits of bioactive compounds from the genus ilex, a source of traditional caffeinated beverages. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, J.F.; Jarrett, C.; Cummins, I.; Logan–Hines, E. Amazonian guayusa (Ilex guayusa Loes.): A historical and ethnobotanical overview. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Crespo, Y.; Radice, M.; Bravo-Sanchez, L.R.; García-Quintana, Y.; Scalvenzi, L. Optimisation of ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic antioxidants from Ilex guayusa Loes. leaves using response surface methodology. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacís-Chiriboga, J.; García-Ruiz, A.; Baenas, N.; Moreno, D.A.; Melendez-Martinez, A.J.; Stinco, C.M.; Jerves-Andrade, L.; León-Tamariz, F.; Ortiz-Ulloa, J.; Ruales, J. Changes in phytochemical composition, bioactivity andin vitrodigestibility of guayusa leaves (Ilex guayusa Loes.) in different ripening stages. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1927–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contero, F.; Abdo, S.; Vinueza, D.; Moreno, J.; Tuquinga, M.; Paca, N. Estrogenic activity of ethanolic extracts from leaves of Ilex guayusa Loes. and Medicago sativa in Rattus norvegicus. PhOL 2015, 2, 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, P.; Vergara, B.; Carillo, C.; Mosquera, T. Chemical constituents and antifungal activity of leaf essential oil from Oreopanax ecuadorensis seem. (Pumamaki), endemic plant of Ecuador. Pharmacogn. J. 2019, 11, 1544–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, H.; Carpio, C.; Ledezma-Carrizalez, A.C.; Sánchez, J.; Ramos, L.; Shugulí, C.M.; Andino, M.; Chiurato, M. Effects of aqueous extracts from amazon plants on Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) and Brevicoryne brassicae (Homoptera: Aphididae) in laboratory, semifield, and field trials. J. Insect Sci. 2019, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu-Naranjo, R.; Paredes-Moreta, J.G.; Granda-Albuja, G.; Iturralde, G.; González-Paramás, A.M.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M. Bioactive compounds, phenolic profile, antioxidant capacity and effectiveness against lipid peroxidation of cell membranes of Mauritia flexuosa L. fruit extracts from three biomes in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Heliyon 2020, 6, 05211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarezo, E.; Aguilera-Sarmiento, R.; Meneses, M.A.; Morocho, V. Study of essential oils from leaves of asteraceae family species Ageratina dendroides and Gynoxys verrucosa. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2021, 24, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Benavides, J.C.; Ortega-Torres, G.C.; Villacis, J.; Vivanco-Jaramillo, S.L.; Galarza-Urgilés, K.I.; Bailon-Moscoso, N. Phytochemical study and evaluation of the cytotoxic properties of methanolic extract from Baccharis obtusifolia. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 2018, 8908435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarezo, E.; Arias, A.; Cartuche, L.; Meneses, M.; Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Morocho, V. Biological activity and chemical composition of the essential oil from Chromolaena laevigata (Lam.) R.M. King & H. Rob. (Asteraceae) from Loja, Ecuador. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2016, 19, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, D.A.G.; Granda-Albuja, M.G.; Guevara, M.; Iturralde, G.A.; Jaramillo-Vivanco, T.; Giampieri, F.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of Chuquiraga jussieui J.F.Gmel from the highlands of Ecuador. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 2652–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteri-Espinoza, R.; Peñarreta, J.; Quijano-Avilés, M.; Barragán-Lucas, A.; Chóez-Guaranda, I.; Manzano-Santana, P. Antioxidant activity and GC-MS profile of Conyza bonariensis L. leaves extract and fractions. Rev. Fac. Nac. Agron. Medellín 2020, 73, 9305–9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, S.; Bec, N.; Larroque, C.; Ramírez, J.; Sgorbini, B.; Bicchi, C.; Gilardoni, G. Chemical, enantioselective, and sensory analysis of a cholinesterase inhibitor essential oil from Coreopsis triloba S.F. Blake (Asteraceae). Plants 2019, 8, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarezo, E.; Guamán, M.D.C.; Paguay, M.; Meneses, M.A. Chemical composition and biological activity of the essential oil from Gnaphalium elegans Kunth from Loja, Ecuador. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2019, 22, 1372–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo-Baptista, L.; Vimos-Sisa, K.; Cruz-Tenempaguay, R.; Falconí-Ontaneida, F.; Rojas-Fermín, L.; González-Romero, A.C. Chemical components and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Lasiocephalus ovatus (Asteraceae) that grows in Ecuador. Acta Biol. Colomb. 2020, 25, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata-Maldonado, C.I.; Serrato-Cruz, M.A.; Ibarra, E.; Naranjo-Puente, B. Chemical compounds of essential oil of Tagetes species of Ecuador. Ecorfan J. Repub. Nicar. 2015, 1, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- López-Barrera, A.J.; Gutiérrez-Gaitén, Y.I.; Miranda-Martínez, M.; Choez Guaranda, I.A.; Ruíz-Reyes, S.G.; Scull-Lizama, R. Pharmacognostic, phytochemical, and anti-inflammatory effects of Corynaea crassa: A comparative study of plants from Ecuador and Peru. Pharmacogn. Res. 2020, 12, 395–402. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, A.T.; Scalvenzi, L.; Piedra-Lescano, A.S.; Radice, M. Ethnopharmacology, biological activity and chemical characterization of Mansoa alliacea. A review about a promising plant from Amazonian region. MOL2NET 2017, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Valarezo, E.; Vidal, V.; Calva, J.; Jaramillo, S.P.; Febres, J.D.; Benítez, A. Essential oil constituents of mosses species from Ecuador. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Tandazo, O.; Galán, K.; Rosales, J.; Benítez, Á. Volatile metabolites in Liverworts of Ecuador. Metabolites 2020, 10, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fon-Fay, F.M.; Pino, J.A.; Hernández, I.; Rodeiro, I.; Fernández, M.D. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana et Planch essential oil from Manabí, Ecuador. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2019, 31, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Valeirón, C.; Guzmán, L.; Saa, L.R.; López-Vargas, J.; Valarezo, E. Acaricidal activity of essential oils of Bursera graveolens (Kunth) Triana & Planch and Schinus molle L. on unengorged larvae of cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus (Acari:Ixodidae). J. Essent. Oil Res. 2017, 29, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Cartuche, L.; Andrade-González, N.; González-Sánchez, I.; Meneses, M.A. Extraction and study of the essential oil of copal (Dacryodes peruviana), an Amazonian fruit with the highest yield worldwide. Plants 2020, 9, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuna, J.L.; Silva, M.; Álvarez, M.; Quinteros, M.F.; Morales, D.; Carrillo, W. Yellow pitahaya (Hylocereus megalanthus) fatty acid composition from Ecuadorian Amazonas. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2018, 11, 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, S.H.T.; Torres, M.C.T.; García, V.J.; Lucena, M.E.; Baptista, L.A. Composición química del aceite esencial de las hojas de Hedyosmum luteynii Todzia (Chloranthaceae). Rev. Peru. De Biol. 2018, 25, 173–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Guamán-Ortiz, L.M.; Bailon-Moscoso, N.; Morocho, V.; Vega-Ojeda, D.; Gordillo, F.; Suárez, A.I. Onoseriolide, from Hedyosmum racemosum, induces cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3151–3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.; Morocho, V.; Vidari, G.; Bicchi, C.; Gilardoni, G. Phytochemical investigation of male and female Hedyosmum scabrum (Ruiz & Pav.) Solms Leaves from Ecuador. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1700423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Rivas, R.; Bailon-Moscoso, N.; Cartuche, L.; Romero-Benavides, J.C. The antioxidant and hypoglycemic properties and phytochemical profile of Clusia latipes extracts. Pharmacogn. J. 2020, 12, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, A.I.; Armijos, C.; Quisatagsi, E.V.; Cuenca, M.; Cuenca-Camacho, S.; Bailón-Moscoso, N. The cytotoxic principle of Bejaria resinosa from Ecuador. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2015, 4, 268–272. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, C.; Pérez, Y.; Morocho, V.; Armijos, C.; Malagón, O.; Brito, B.; Tacán, M.; Cartuche, L.; Gilardoni, G. Preliminary phytochemical study of the ecuadorian plant Croton elegans kunth (euphorbiaceae). J. Chil. Chem. Soc. 2018, 63, 3875–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morocho, V.; Sarango, D.; Cruz-Erazo, C.; Cumbicus, N.; Cartuche, L.; Suárez, A.I. Chemical constituents of Croton thurifer Kunth as α-Glucosidase inhibitors. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2019, 14, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Terán-Portelles, E.C.; Hernández, I.; Rodeiro, I.; Fernández, M.D. Chemical composition of the essential oil from Croton wagneri Müll. Arg. (Euphorbiaceae) grown in Ecuador. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2018, 30, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardoni, G.; Montalván, M.; Ortiz, M.; Vinueza, D.; Montesinos, J.V. The flower essential oil of Dalea mutisii Kunth (Fabaceae) from Ecuador: Chemical, enantioselective, and olfactometric analyses. Plants 2020, 9, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez, A.I.; Thu, Z.M.; Ramírez, J.; León, D.; Cartuche, L.; Armijos, C.; Vidari, G. Main constituents and antidiabetic properties of Otholobium mexicanum. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2017, 12, 533–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Puma, C.; Fajardo-Carmona, S.; Ortíz-Ulloa, J.; Tobar, V.; Quito-Ávila, D.; Santos-Ordoñez, E.; Jerves-Andrade, L.; Cuzco, N.; Wilches, I.; León-Tamaríz, F. Evaluation of the variables altitude, soil composition and development of a predictive model of the antibacterial activity for the genus Hypericum by chromatographic fingerprint. Phytochem. Lett. 2019, 31, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matailo, A.; Bec, N.; Calva, J.; Ramírez, J.; Andrade, J.M.; Larroque, C.; Vidari, G.; Armijos, C. Selective BuChE inhibitory activity, chemical composition, and enantiomer content of the volatile oil from the Ecuadorian plant Clinopodium brownei. Rev. Bras. De Farm. 2019, 29, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardoni, G.; Ramírez, J.; Montalván, M.; Quinche, W.; León, J.; Benítez, L.; Morocho, V.; Cumbicus, N.; Bicchi, C. Phytochemistry of three Ecuadorian Lamiaceae: Lepechinia heteromorpha (Briq.) Epling, Lepechinia radula (Benth.) Epling and Lepechinia paniculata (Kunth) Epling. Plants 2018, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.; Gilardoni, G.; Jácome, M.; Montesinos, J.; Rodolfi, M.; Guglielminetti, M.L.; Cagliero, C.; Bicchi, C.; Vidari, G. Chemical composition, enantiomeric analysis, AEDA sensorial evaluation and antifungal activity of the essential oil from the Ecuadorian plant Lepechinia mutica Benth (Lamiaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2017, 14, e1700292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, J.; Gilardoni, G.; Ramón, E.; Tosi, S.; Picco, A.M.; Bicchi, C.; Vidari, G. Phytochemical study of the Ecuadorian species Lepechinia mutica (Benth.) Epling and high antifungal activity of carnosol against Pyricularia oryzae. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panamito, M.; Bec, N.; Valdivieso, V.; Salinas, M.; Calva, J.; Ramírez, J.; Larroque, C.; Armijos, C. Chemical composition and anticholinesterase activity of the essential oil of leaves and flowers from the Ecuadorian plant Lepechinia paniculata (Kunth) Epling. Molecules 2021, 26, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morocho, V.; Toro, M.L.; Cartuche, L.; Guaya, D.; Valarezo, E.; Malagón, O.; Ramírez, J. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of Lepechinia radula Benth Epling. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2017, 11, 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Echavarría, A.P.; D’Armas, H.; Matute, N.; Cano, J.A. Phytochemical analyses of eight plants from two provinces of Ecuador by GC-MS. Int. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 8, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Tacchini, M.; Guevara, M.P.E.; Grandini, A.; Maresca, I.; Radice, M.; Angiolella, L.; Guerrini, A. Ocimum campechianum mill. from Amazonian Ecuador: Chemical composition and biological activities of extracts and their main constituents (Eugenol and Rosmarinic Acid). Molecules 2020, 26, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, G.; Salinas, M.; Calva, J.; Bec, N.; Larroque, C.; Vidari, G.; Armijos, C. Selective BuChE inhibitory activity, chemical composition, and enantiomeric content of the essential oil from Salvia leucantha Cav. Collected in Ecuador. Plants 2021, 10, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, M.; Bec, N.; Calva, J.; Ramirez, J.; Andrade, J.M.; Larroque, C.; Vidari, G.; Armijos, C. Chemical composition and anticholinesterase activity of the essential oil from the Ecuadorian plant Salvia pichinchensis Benth. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2020, 14, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubon, I.; Zannoni, A.; Bernardini, C.; Salaroli, R.; Bertocchi, M.; Mandrioli, R.; Vinueza, D.; Antognoni, F.; Forni, M. In vitro anti-inflammatory effect of Salvia sagittata ethanolic extract on primary cultures of porcine aortic endothelial cells. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6829173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pino, J.A.; Fon-Fay, F.M.; Falco, A.S.; Pérez, J.C.; Hernández, I.; Rodeiro, I.; Fernández, M. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil from Ocotea quixos (Lam.) Kosterm. leaves grown wild in Ecuador. Am. J. Essent. Oil Nat. Prod. 2018, 6, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Valarezo, E.; Vullien, A.; Conde-Rojas, D. Variability of the chemical composition of the essential oil from the Amazonian ishpingo species (Ocotea quixos). Molecules 2021, 26, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteaga-Crespo, Y.; Ureta-Leones, D.; García-Quintana, Y.; Montalván, M.; Gilardoni, G.; Malagón, O. Preliminary predictive model of termiticidal and repellent activities of essential oil extracted from Ocotea quixos leaves against Nasutitermes corniger (Isoptera: Termitidae) using one-factor response surface methodology design. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guamán-Ortiz, L.M.; Romero-Benavides, J.C.; Suarez, A.I.; Torres-Aguilar, S.; Castillo-Veintimilla, P.; Samaniego-Romero, J.; Ortiz-Diaz, K.; Bailon-Moscoso, N. Cytotoxic property of Grias neuberthii extract on human colon cancer cells: A crucial role of autophagy. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 1565306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño, H.; Espinosa, S.; Andrade, J.M.; Cartuche, L.; Malagón, O. Novel flavonoid glycosides of quercetin from leaves and flowers of Gaiadendron punctatum G. Don. (Violeta de Campo), used by the Saraguro community in Southern Ecuador, inhibit α-Glucosidase enzyme. Molecules 2019, 24, 4267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijos, C.; Ponce, J.; Ramírez, J.; Gozzini, D.; Finzi, P.V.; Vidari, G. An unprecedented high content of the bioactive flavone tricin in Huperzia medicinal species used by the Saraguro in Ecuador. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 273–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda-Martínez, M.; Sarmiento-Tomalá, G.M.; Chóez-Guaranda, I.A.; Gutiérrez-Gaitén, Y.I.; Delgado-Hernández, R.; Carrillo-Lavid, G. Pharmacognostic, chemical and mucolytic activity study of Malva pseudolavatera webb & berthel. and Malva sylvestris L. (Malvaceae) leaf extracts, grown in Ecuador. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21, 4755–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Moncayo-Molina, L.; Spengler, I.; Pérez, J.C. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of the leaf essential oil of Eucalyptus globulus Labill. from two highs of the canton Cañar, Ecuador. Rev. CENIC Cienc. Quím. 2021, 52, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Montalván, M.; Peñafiel, M.A.; Ramírez, J.; Cumbicus, N.; Bec, N.; Larroque, C.; Bicchi, C.; Gilardoni, G. Chemical composition, enantiomeric distribution, and sensory evaluation of the essential oils distilled from the Ecuadorian species Myrcianthes myrsinoides (Kunth) Grifo and Myrcia mollis (Kunth) dc. (Myrtaceae). Plants 2019, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalvenzi, L.; Grandini, A.; Spagnoletti, A.; Tacchini, M.; Neill, D.; Ballesteros, J.L.; Sacchetti, G.; Guerrini, A. Myrcia splendens (Sw.) DC. (syn. M. fallax (Rich.) DC.) (Myrtaceae) essential oil from Amazonian Ecuador: A chemical characterization and bioactivity profile. Molecules 2017, 22, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvajal, P.C.; Coppo, E.; Di Lorenzo, A.; Gozzini, D.; Bracco, F.; Zanoni, G.; Nabavi, S.M.; Marchese, A.; Arciola, C.R.; Daglia, M. Chemical characterization and in vitro antibacterial activity of Myrcianthes hallii (O. Berg) mcvaugh (Myrtaceae), a traditional plant growing in Ecuador. Materials 2016, 9, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calva, J.; Castillo, J.M.; Bec, N.; Ramirez, J.; Andrade, J.M.; Larroque, C.; Armijos, C. Chemical composition, enantiomeric distribution and AChE-BChE activities of the essential oil of Myrteola phylicoides (Benth) Landrum from Ecuador. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2019, 13, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radice, M.; Scalvenzi, L.; Gutiérrez, D. Ethnopharmacology, bioactivity and phytochemistry of Maxillaria densa Lindl. Scientific review and biotrading in the neotropics. Colomb. For. 2020, 23, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chóez, I.; Herrera, D.; Miranda, M.; Manzano, P.I.; Chóez-Guaranda, I. Chemical composition of essential oils of shells, juice and seeds of Passiflora ligularis Juss from Ecuador. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2015, 27, 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega-Rivera, P.; Mosquera, T.; Baldisserotto, A.; Abad, J.; Aillon, C.; Cabezas, D.; Piedra, J.; Coronel, I.; Manfredini, S. Chemical composition and in-vitro biological activities of the essential oil from leaves of Peperomia inaequalifolia Ruiz & Pav. Am. J. Essent. Oil Nat. Prod. 2015, 2, 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, P.; Ballesteros, J.; De La Cruz, A.; Veloz, T. Chemical composition and preliminary antimicrobial activity of the hydroxylated sesquiterpenes in the essential oil from Piper barbatum Kunth leaves. Plants 2020, 9, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oacute, N.M.; Velasco, J.; Cornejo, X.; Aacute, N.J.; Morocho, V. Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of Piper lenticellosum C. DC essential oil collected in Ecuador. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gilardoni, G.; Matute, Y.; Ramírez, J. Chemical and enantioselective analysis of the leaf essential oil from Piper coruscans Kunth (Piperaceae), a costal and Amazonian native species of Ecuador. Plants 2020, 9, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Flores-Maza, P.; Cartuche, L.; Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Ramírez, J. Phytochemical profile, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil extracted from Ecuadorian species Piper ecuadorense sodiro. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Valdivieso, M.; Gilardoni, G.; Calva, J.; Morocho, V.; Valarezo, E.; Malagon, O. Development and validation of a high-performance liquid chromatographic method for the determination of pinocembrin in leaves of piper ecuadorense sodiro. Axioma 2019, 1, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valarezo, E.; Benítez, L.; Palacio, C.; Aguilar, S.; Armijos, C.; Calva, J.; Ramírez, J. Volatile and non-volatile metabolite study of endemic ecuadorian specie Piper lanceifolium Kunth. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2021, 33, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriega, P.F.; Mosquera, T.; Abad, J.; Cabezas, D.; Piedra, S.; Coronel, I.; Maldonado, M.E.; Bardiserotto, A.; Vertuani, S.; Manfredini, S. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil from leaves of Piper pubinervulum D. DC Piperaceae. La Granja Rev. Cienc. Vida 2016, 24, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, J.; Andrade, M.; Vidari, G.; Gilardoni, G. Essential oil and major non-volatile secondary metabolites from the leaves of Amazonian Piper subscutatum. Plants 2021, 10, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valarezo, E.; Rosales-Acevedo, V.; Ojeda-Riascos, S.; Meneses, M.A. Phytochemical profile, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of essential oil from the leaves of native Amazonian species of Ecuador Sarcorhachis sydowii Trel. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2021, 24, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Naranjo, M.; Suárez, A.; Gilardoni, G.; Cartuche, L.; Flores, P.; Morocho, V. Chemical constituents of Muehlenbeckia tamnifolia (Kunth) Meisn (Polygonaceae) and its in vitro α-Amilase and α-Glucosidase inhibitory activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinueza, D.; Yanza, K.; Tacchini, M.; Grandini, A.; Sacchetti, G.; Chiurato, M.A.; Guerrini, A. Flavonoids in Ecuadorian Oreocallis grandiflora (Lam.) R. Br.: Perspectives of use of this species as a food supplement. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2018, 2018, 1353129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.C.; Suárez, A.I.; Cumbicus, N.; Morocho, V. Estudio fitoquímico de roupala montana aubl. De la provincia de loja. Axioma 2018, 2, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milella, L.; Milazzo, S.; De Leo, M.; Saltos, M.B.V.; Faraone, I.; Tuccinardi, T.; Lapillo, M.; De Tommasi, N.; Braca, A. α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase inhibitors from Arcytophyllum thymifolium. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 2104–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bustamante-Pesantes, K.E.; Gutiérrez-Gaitén, Y.I.; Chóez-Guaranda, I.A.; Miranda-Martínez, M. Chemical composition, antioxidant capacity and anti-inflammatory activity of the fruits of Mimusops coriacea (A.DC) Mig (Sapotaceae) that grows in Ecuador. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res. 2021, 9, 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.; Gilardoni, G.; Cumbicus, N.; Morocho, V. Chemical analysis of the essential oil from Siparuna echinata (Kunth) A. DC. (Siparunaceae) of Ecuador and isolation of the rare terpenoid sipaucin A. Plants 2020, 9, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burneo, J.I.; Benítez, Á.; Calva, J.; Velastegui, P.; Morocho, V. Soil and leaf nutrients drivers on the chemical composition of the essential oil of Siparuna muricata (Ruiz & Pav.) A. DC. from Ecuador. Molecules 2021, 26, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vélez, E.; D’Armas, H.; Jaramillo-Jaramillo, C.; Echavarría-Vélez, A.P.; Isitua, C.C. Phytochemistry of Lippia citriodora K. grown in Ecuador and its biological activity. Cienc. Unemi 2019, 12, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.A.; Fon-Fay, F.M.; Pérez, J.C.; Falco, A.S.; Hernández, I.; Rodeiro, I.; Fernández, M.D. Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil from turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) rhizomes grown in Amazonian Ecuador. Rev. CENIC Cienc. Quím. 2018, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Noriega, P.F.; Paredes, E.A.; Mosquera, T.D.; Días, E.E.; Lueckhoff, A.; Basantes, J.E.; Trujillo, A.L. Chemical composition antimicrobial and free radical scavenging activity of essential oil from leaves of Renealmia thyrsoidea (Ruis & Pav.) Poepp & Endl. J. Med. Plant Res. 2016, 10, 553–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höferl, M.; Stoilova, I.; Wanner, J.; Schmidt, E.; Jirovetz, L.; Trifonova, D.; Stanchev, V.; Krastanov, A. Composition and comprehensive antioxidant activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) essential oil from Ecuador. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2015, 10, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).