Geometrical Optimal Navigation and Path Planning—Bridging Theory, Algorithms, and Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Navigation Methods

2.1. Classical Path Planning Methods

- Roadmap Methods: These methods create a graph representation of the environment, connecting obstacles and the target point. Examples include the following:

- Cell Decomposition: This approach divides the workspace into smaller cells, enabling the robot to navigate through collision-free regions. Notable examples include the following:

- –

- Lozano-Perez’s C-Space Decomposition (1983): Treats the robot as a C-shaped object and subdivides the environment into cells to identify feasible paths [10].

- –

- Grid-Based Methods: Popularized by Hachour (2008), this technique discretizes the environment into a grid, simplifying path planning through cell-by-cell exploration [11].

- Potential Field Method: Models the robot as a particle influenced by artificial potential fields. Attractive potentials guide the robot toward the goal, while repulsive potentials push it away from obstacles. This method ensures smooth navigation but can suffer from local minima issues [12].

- Mathematical Programming: Formulates path planning as an optimization problem, treating obstacle avoidance as a set of inequalities. The goal is to minimize a scalar quantity (e.g., path length or energy consumption) while finding a feasible curve between the start and target points [8].

2.2. Reactive Path Planning Methods

- Subsumption Architecture: Organizes robot behaviors into hierarchical layers, with higher-level actions overriding lower-level ones. This structure enables quick responses to environmental changes but may lack global optimization [13].

- Motor Schemas: Generates output vectors for distinct behaviors (e.g., obstacle avoidance, goal seeking), which are combined through vector summation to determine the robot’s overall response. This approach allows for flexible and adaptive navigation [14].

2.3. Hybrid Path Planning Methods

- Managerial Approaches: Use a high-level planner to generate global paths while employing reactive strategies for local obstacle avoidance [17].

- State Hierarchies: Organize navigation tasks into hierarchical states, enabling seamless transitions between global and local planning [18].

- Model-Oriented Styles: Incorporate environmental models to enhance decision-making, balancing long-term planning with real-time adjustments [19].

3. Optimization Criteria in Geometric Trajectory Planning

3.1. Key Optimization Criteria

- Trajectory Length: Minimizing the path length is often the primary objective, as it directly impacts the robot’s efficiency and resource utilization. Shorter trajectories reduce travel time and energy consumption, making them ideal for many applications [8].

- Trajectory Smoothness: Smooth trajectories are crucial for ensuring stable and efficient robot motion. Abrupt changes in direction or velocity can lead to mechanical stress, increased energy consumption, and reduced accuracy. Smoothness is often quantified using curvature and jerk metrics [28].

- Time Efficiency: Time-optimal trajectories are critical in applications where speed is a priority, such as in industrial automation or search-and-rescue operations. Time efficiency is closely tied to the robot’s velocity profile and acceleration limits [29].

- Energy Consumption: Energy-efficient trajectories are vital for battery-powered robots or systems operating in energy-constrained environments. Optimizing energy usage involves minimizing unnecessary acceleration, deceleration, and idling [30].

- Collision Avoidance: Ensuring collision-free trajectories is a fundamental requirement in any navigation task. This involves not only avoiding static obstacles but also dynamically adapting to moving obstacles in real-time [12].

- Environmental Factors: External conditions such as wind resistance, terrain roughness, or fluid dynamics (in underwater or aerial robots) can significantly impact trajectory planning. These factors must be modeled and accounted for to ensure robust performance [31].

3.2. Path Length as an Optimization Criterion

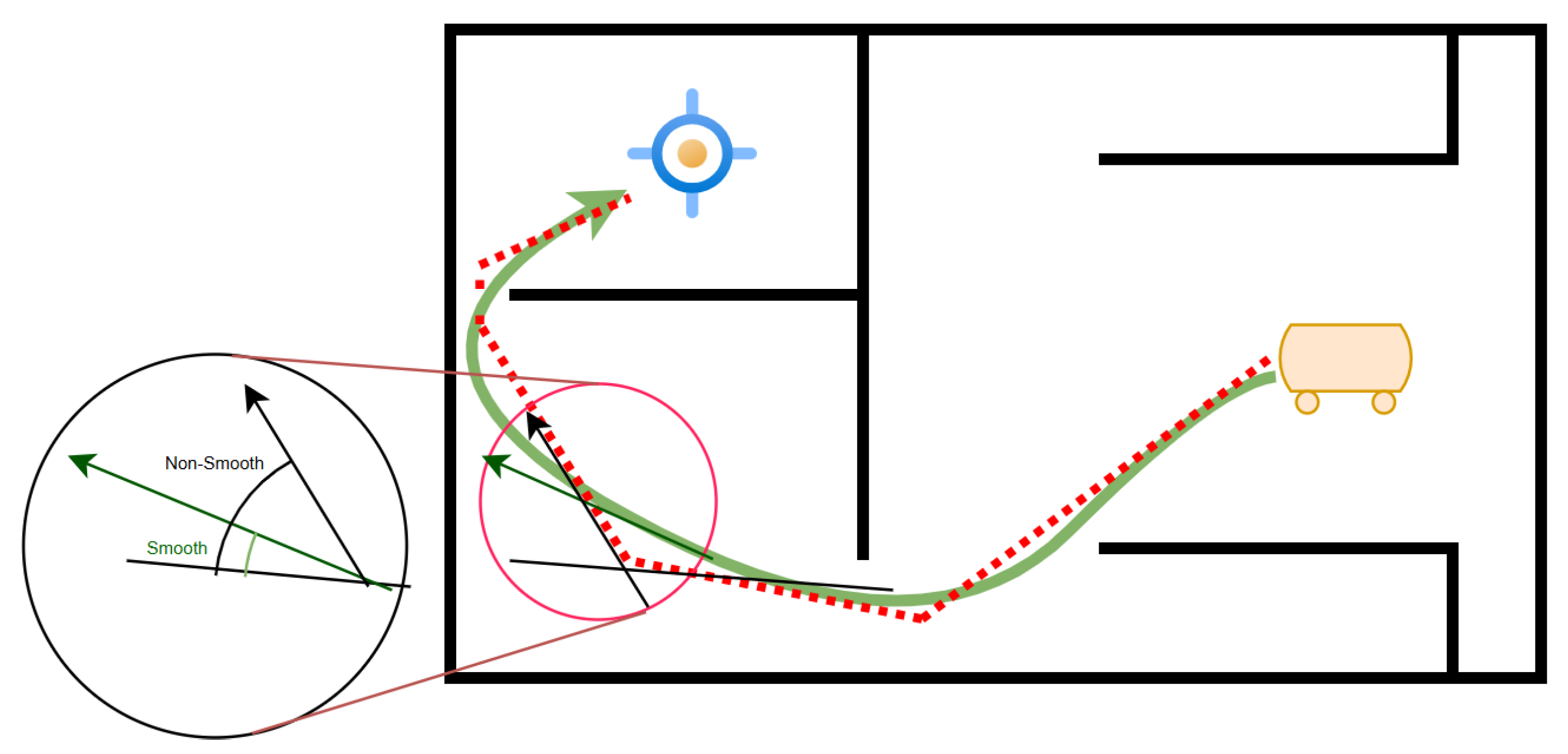

3.3. Path Smoothness in Robotic Navigation

- Curvature Continuity: Ensuring that the curvature of the path is continuous, which is critical for high-speed navigation and dynamic environments [42].

- Jerk Minimization: Minimizing the rate of change of acceleration (jerk) to ensure smoother motion and reduce wear on the robot’s actuators [43].

- Energy-Efficient Smoothing: Optimizing paths to minimize energy consumption, which is particularly important for battery-operated robots [44].

- Adaptive Smoothing: Dynamically adjusting the smoothness of the path based on environmental changes and obstacle movements [45].

3.4. Time Cost in Robotic Navigation

- is the state space of the robot dynamics;

- x is the state vector, consisting of position, velocity, and possibly acceleration;

- u is the control input that may depend on voltage; torque, or other functions of control manipulators;

- T is the total execution time.

- is the robot motion acceleration, which is a function of the control input at the k-th time sample;

- N is the final time step when the robot reaches the goal;

- is the k-th collision-free waypoint.

- is the velocity of the robot,

- is the control input,

- is a weighting factor that balances the trade-off between velocity and control effort.

- is a penalty function that increases the cost when the robot approaches obstacles or violates environmental constraints;

- is a weighting factor for the control effort.

- M is the number of robots;

- is a penalty function that ensures collision avoidance between robots j and k.

- Reward Function: Designed to penalize time consumption and deviations from the desired trajectory.

- State-Action Space: Encodes the robot’s dynamics and environmental constraints.

- Training Efficiency: Measured by the convergence rate and computational resources required.

- Horizon Length: Determines the number of future steps considered in the optimization.

- Constraint Handling: Ensures the feasibility of the trajectory under dynamic and environmental constraints.

- Computational Complexity: Measured by the time required to solve the optimization problem at each time step.

- Pareto Front: Represents the trade-off between competing objectives.

- Weighting Factors: Used to prioritize time-optimality over other objectives.

- Scalability: Evaluated based on the ability to handle high-dimensional state spaces.

- Empirical tuning: Values of are adjusted experimentally until the robot achieves satisfactory performance in representative environments.

- Optimization-based methods: is treated as a hyperparameter and optimized through grid search, Bayesian optimization, or reinforcement learning to minimize a performance metric such as tracking error or energy usage.

- Domain-specific constraints: For safety-critical or resource-limited systems, may be constrained by hardware limits (e.g., maximum actuator torque) or mission requirements (e.g., prioritizing faster response over energy saving).

- Replanning Frequency: Determines how often the trajectory is updated.

- Convergence Speed: Measures the time required to adapt to new environmental conditions.

- Robustness: Evaluated based on the ability to handle uncertainties and disturbances.

- Autonomous vehicles;

- Industrial robotics;

- Aerial drones.

3.5. Energy Cost in Robotic Navigation

- Kinetic Energy (Ek): Energy associated with the robot’s motion.

- Traction Resistance Energy (Ef): Energy dissipated in overcoming traction resistances.

- Motor Heating Energy (Ee): Energy lost as heat in the motors.

- Mechanical Friction Energy (Em): Energy dissipated in overcoming friction torque.

- Idle Energy (Eidle): Energy consumed by idling motors and onboard electric devices.

- is the total power consumption and loss at time t;

- T is the total execution time.

- is the power consumed during motion;

- is the power consumed during idle states.

- is the efficiency of the regenerative braking system,

- is the power generated during braking.

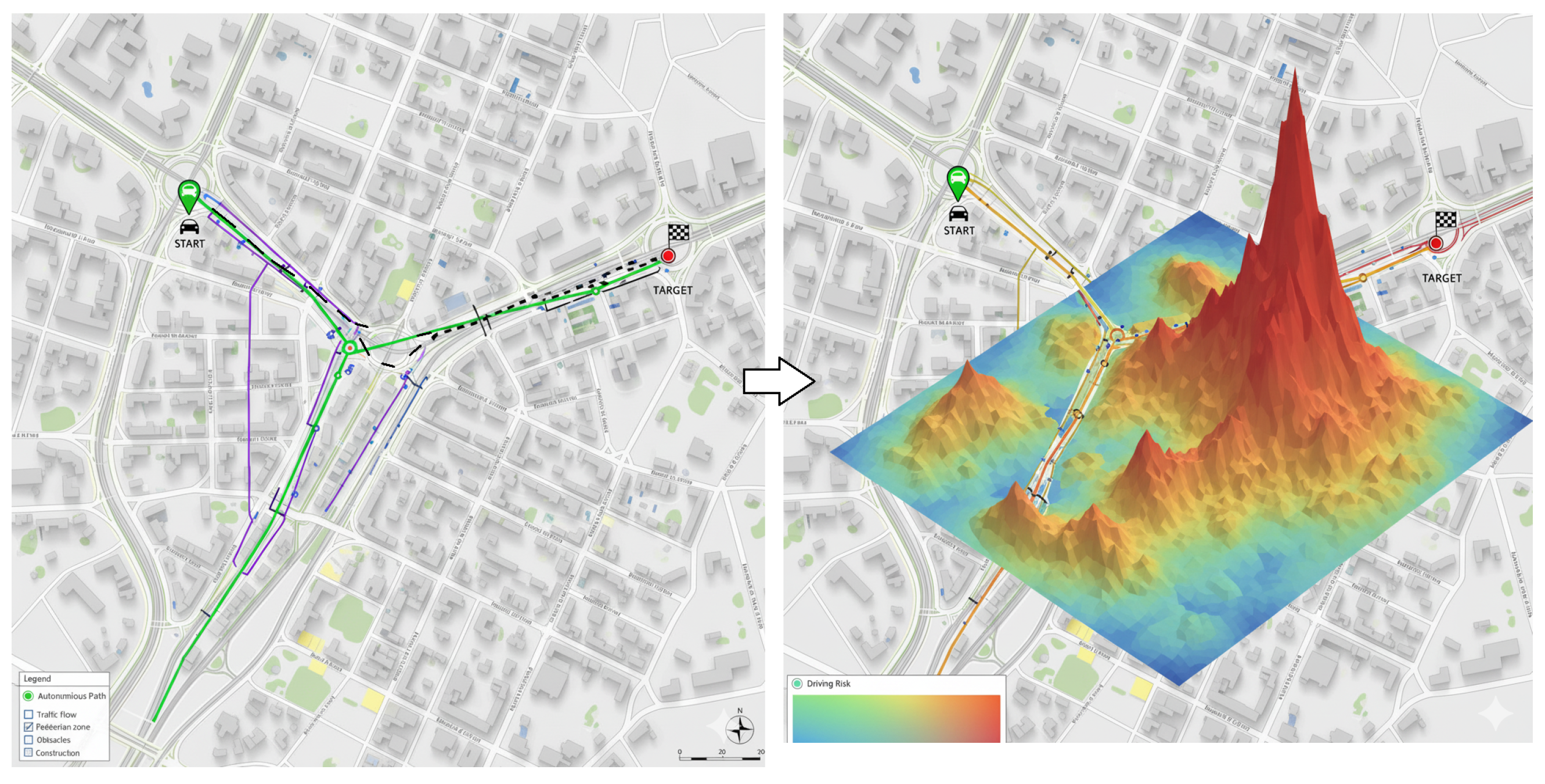

3.6. Risk Cost in Robotic Navigation

- Collision Risk: Probability of collisions with environmental elements or individuals.

- Robot Malfunction: Probability of robot failure or abrupt movements.

- Environmental Hazards: Probability of natural events such as rain or wind increasing the risk of slipping or crashing.

- is the probability of a risk event at time t,

- is the cost associated with the event.

- is the neural network function;

- represents the network parameters.

- is the membership function for the i-th risk factor;

- is the cost associated with the i-th risk factor.

3.7. Integration of Optimization Criteria

4. Approaches to Solving Optimal Navigation Problems

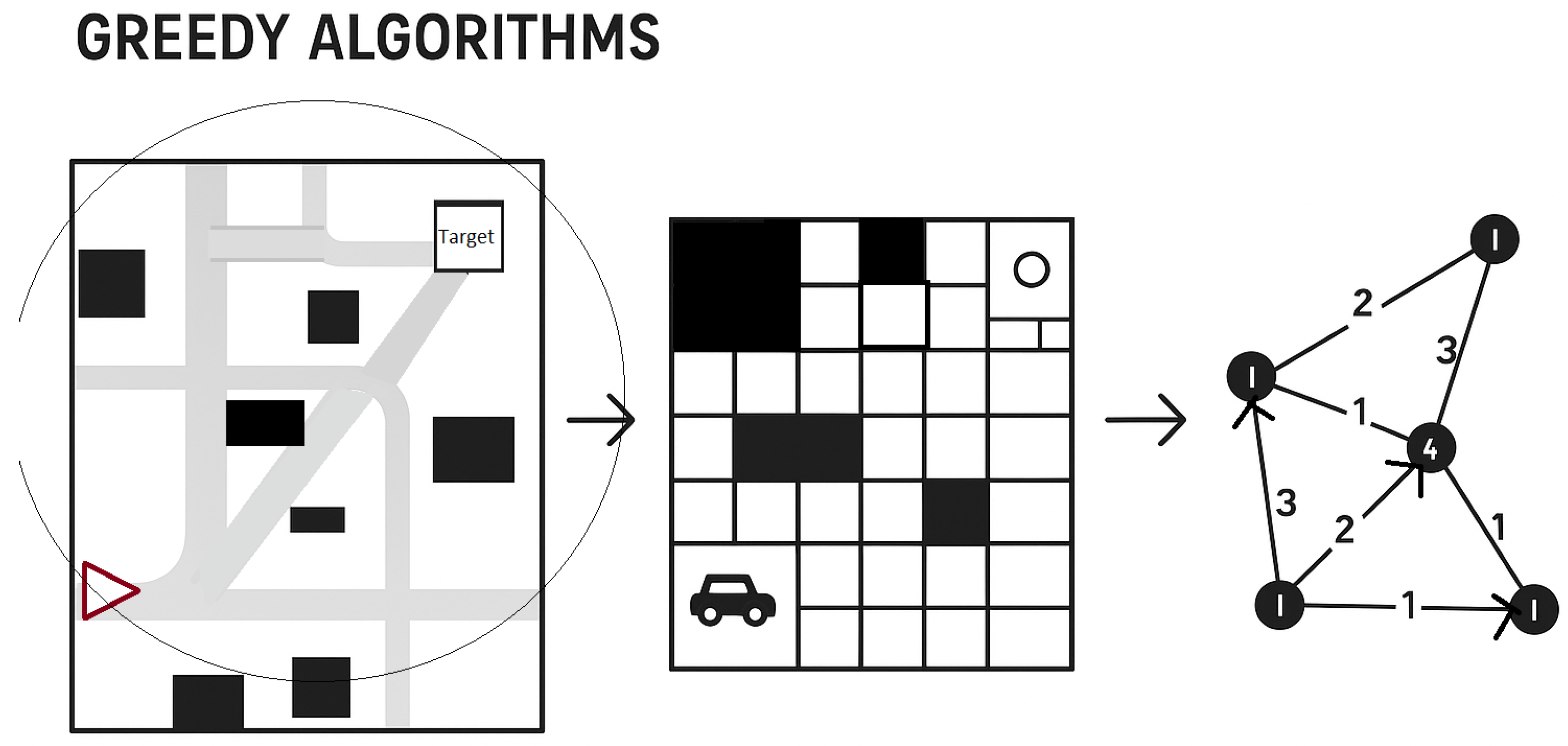

4.1. Greedy Algorithms

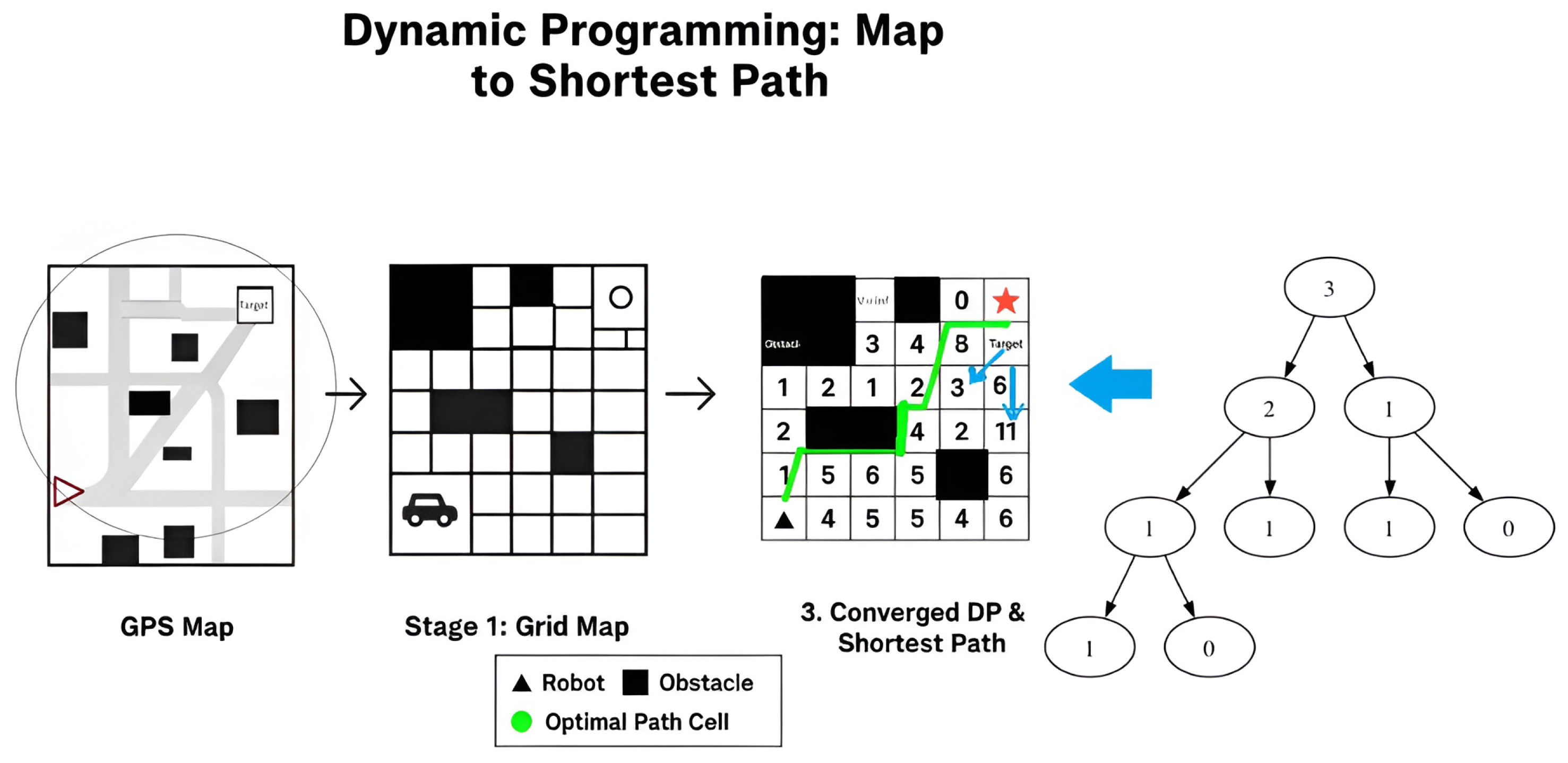

4.2. Dynamic Programming (DP)

4.3. Evolutionary Algorithms (EAs)

4.4. Sampling-Based Algorithms

- Key Advantages: These planners are scalable and flexible, making them suitable for high-dimensional spaces (e.g., robotic manipulators) where grid-based searches are computationally prohibitive. They do not require explicit environment discretization, enabling efficient path generation in complex, cluttered settings. Modern extensions, such as Adaptive RRT* and deep learning-guided planners, further enhance adaptability by dynamically adjusting sampling strategies in response to moving obstacles or semantic environmental cues.

- Limitations: Despite their strengths, standard sampling-based methods can produce sub-optimal, non-smooth paths, often requiring post-processing. They also struggle in dynamic environments without specific adaptations and are sensitive to parameter tuning (e.g., step size, sampling distributions). Additionally, learning-based enhancements, while improving adaptability, can introduce extra computational overhead from model training and real-time inference, potentially affecting performance.

4.5. Recent Advances in Optimal Navigation

- Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL): DRL-based approaches have been employed to learn optimal navigation policies in complex environments [85].

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): MPC frameworks have been extended to incorporate dynamic constraints, enabling real-time navigation optimization [86].

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Recent studies have combined navigation objectives, such as time-optimality and energy efficiency, using Pareto optimization techniques [87].

- Adaptive Navigation: Adaptive methods dynamically adjust navigation strategies based on environmental changes, ensuring robustness in dynamic settings [88].

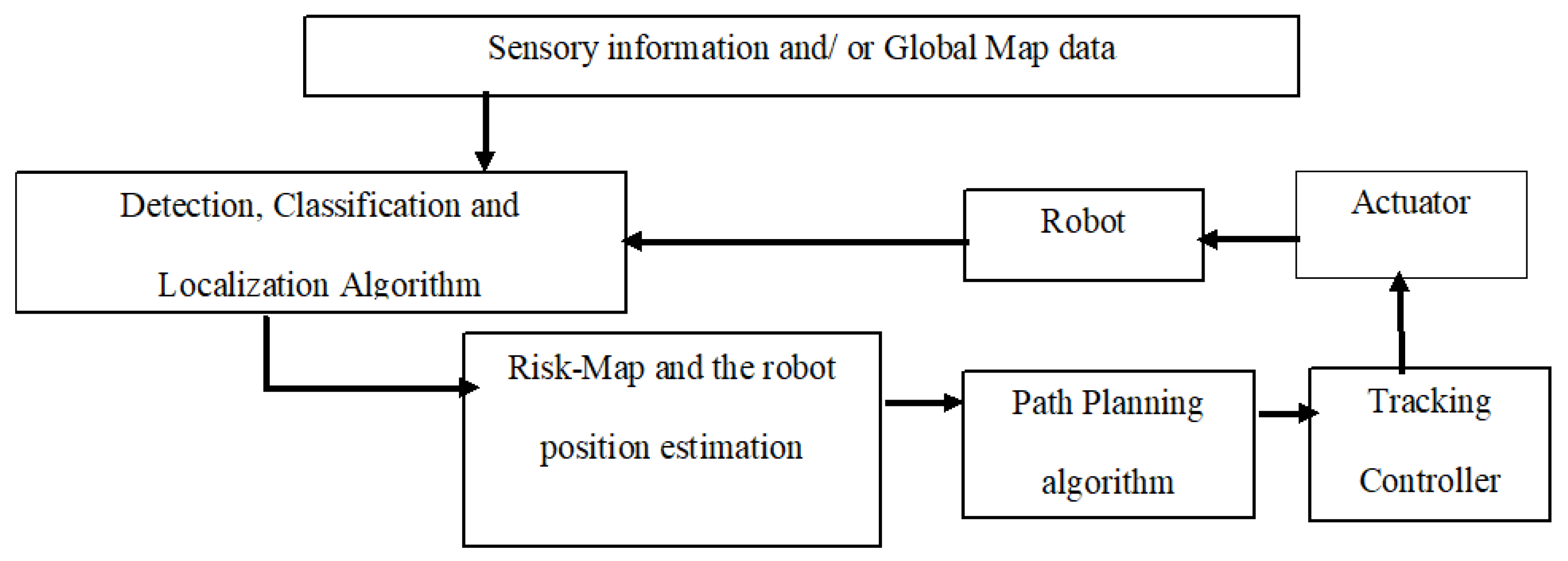

5. Overview of Collision-Free Path Planning Strategy

5.1. Hybrid Path Planning

- is the hybrid path;

- is the globally optimal path;

- is the locally adjusted path;

- is a weighting factor that balances global and local planning.

- Behavior-based methods: These approaches adjust depending on environmental cues such as obstacle density or the need for smoother local maneuvers. For instance, heuristic and bio-inspired algorithms like the Hybrid Improved Artificial Fish Swarm Algorithm (HIAFSA) dynamically regulate based on proximity to obstacles [90].

- Optimization-driven methods: Here, is updated online through explicit optimization frameworks. A notable example is the adaptive visibility graph combined with A*, which minimizes tracking error and energy consumption by recalibrating in response to evolving constraints [91].

- Learning-based approaches: More recent methods rely on reinforcement learning and evolutionary strategies to “learn” how should evolve across diverse scenarios. The Multi-strategy Hybrid Adaptive Dung Beetle Optimization (MSHADO) algorithm, for example, employs chaotic mapping and multi-strategy fusion to enhance population diversity, enabling robots to adaptively balance global exploration with local exploitation [92].

5.2. Real-Time Adaptation

- is the robot’s state at time t;

- is the reference trajectory;

- is the control input;

- T is the prediction horizon.

5.3. Recent Advancements in Collision-Free Path Planning

- Deep Reinforcement Learning (DRL): DRL-based approaches have been employed to learn collision-free navigation policies in complex environments [94].

- Multi-Agent Path Planning: Techniques for coordinating multiple robots to avoid collisions while achieving individual goals [95].

- Uncertainty-Aware Planning: Methods that account for uncertainties in sensor data and environmental dynamics [84].

- Energy-Efficient Path Planning: Energy-efficient path planning combines the optimization of energy consumption with collision avoidance, employing various algorithmic strategies tailored to different robotic systems and environments. These approaches address challenges like terrain roughness, multi-agent coordination, and dynamic obstacles while minimizing motion costs [82].

6. Challenges in Geometric Optimal Navigation

6.1. Scalability in High-Dimensional Spaces

6.1.1. Dimensionality Reduction Techniques

- is the high-dimensional data matrix;

- is the transformation matrix;

- is the low-dimensional representation.

6.1.2. Machine Learning Approaches

6.2. Real-Time Computation for Dynamic Environments

- Parallelizing computationally intensive steps (sampling, collision checking, graph search).

- Adaptive spatial and temporal resolution to reduce unnecessary computation.

- Decomposing the problem into hierarchical or modular sub-problems.

- Leveraging learned models to prune search space or estimate costs rapidly.

6.3. Parallel Optimization for Real-Time Trajectory Planning

| Algorithm 1 Real-Time Parallel Trajectory Optimization |

|

6.4. Strategies for Real-Time Scalability

- GPU-Accelerated Evaluation: Modern GPUs allow hundreds to thousands of trajectory knot gradients to be evaluated simultaneously, enabling speed-ups by orders of magnitude compared to serial CPUs. This parallelism dramatically reduces iteration times for gradient computation and constraint checking, empowering planners to meet real-time deadlines even in high-dimensional state spaces [97,98,99].Recent work by Rastgar [98] proposes novel GPU-parallel optimization algorithms that adapt constraint formulations to fully leverage GPU architectures, markedly enhancing scalability and robustness in dynamic scenarios. Similarly, Yu et al. [99] introduce TOP, trajectory optimization via parallel consensus ADMM that achieves near-constant time complexity per iteration by decomposing long trajectories into parallelizable segments, enabling large-scale real-time path planning on GPUs.

- Warm Starting: Utilizing the previously computed optimal trajectory as an initial guess accelerates the convergence of iterative solvers. This approach is especially effective in dynamic environments where consecutive plans differ only slightly [98,100].By reusing prior solutions, planners reduce redundant computation while improving continuity and smoothness of resulting trajectories. This practical technique aligns with state-of-the-art GPU-accelerated approaches that integrate warm-starting for real-time feasibility.

- Receding Horizon Execution: Instead of optimizing over the entire trajectory horizon, planners focus on a shorter, fixed-duration segment. Only the initial portion of the plan is executed before replanning occurs, maintaining continual responsiveness to environmental changes and dynamic obstacles [98,101].This limited horizon approach bounds computational demands, facilitates faster replanning, and supports adaptive trajectory refinement, key for scalable navigation in cluttered or rapidly changing environments.

- Adaptive Termination and Step Sizing: Optimization algorithms dynamically adjust their step sizes and employ early stopping criteria once trajectories reach a suitable quality level within the operational time budget. This balances the trade-off between latency and solution optimality.For example, algorithms may terminate as soon as collision-free smooth paths are found, even if not perfectly optimal, ensuring timely availability of actionable plans without compromising safety [99].

- Integrated Recent Advances:Incorporating the above core principles, recent methods extend scalability and robustness in real-time planning:

- –

- Semantic-Aware Optimization: He et al. [102] develop a spatio-temporal semantic graph optimizer tailored for urban autonomous driving. Their approach handles dynamic obstacle semantics through sparse graph formulations, enabling real-time feasible trajectories that intelligently incorporate semantic understanding of traffic participants and road elements.

- –

- Hybrid Sampling and Rewiring: Silveira et al. [103] propose RT-FMT, a hybrid of Fast Marching Tree and RT-RRT*, that combines incremental rewiring and local-to-global tree reuse for faster execution and improved path quality in dynamic environments. By efficiently reusing prior tree structures and limiting expansion scope, RT-FMT exemplifies algorithmic decomposition, enabling scalability.

- –

- Piecewise Parallel Optimization: Yu et al. [99] introduce the TOP framework, which decomposes long trajectories into smaller segments solved in parallel while ensuring high-order continuity through consensus constraints. Deploying this method on GPUs supports extremely large-scale and long-horizon real-time trajectory optimization, pushing the frontier of computational performance in robotics.

- –

- Constraint Reformulation for Parallelism: Rastgar’s thesis [98] innovates by remodeling kinematic and collision constraints to be more amenable to parallel GPU computation, thereby enhancing planner scalability and resulting in more reliable real-time performance. GPU acceleration leverages parallel processing in graphics units to speed up computation-heavy tasks like sensor data processing and path planning, enabling real-time navigation in complex environments. Neural approximators, such as neural networks running on GPUs or neuromorphic chips, offer efficient models that reduce computation while preserving accuracy. These technologies are crucial for power-limited robots and edge devices, allowing them to perform advanced navigation tasks with manageable latency and energy usage [104,105,106].

6.5. Integration of Perception Systems

Deep Learning for Perception

6.6. Ethical and Safety Concerns in Human–Robot Interactions

- Transparency: Robots should clearly communicate intentions and behaviors to enhance human trust.

- Accountability: Developers and operators must be accountable for system behavior, particularly in high-stakes contexts.

- Fairness: Systems should actively mitigate bias and promote equitable treatment across user demographics.

- Collision Avoidance: Sensor fusion and predictive models allow robots to anticipate and avoid human contact.

- Emergency Stop Mechanisms: Systems must be capable of halting immediately under risk conditions.

- Human-in-the-Loop Control: Dynamic shared autonomy enables humans to intervene in uncertain or dangerous scenarios.

6.7. Toward Human-Centric Design and Learning

- Integration Complexity: Embedding ethical and safety modules into fast, real-time planners on resource-constrained platforms remains difficult.

- Standardization Gaps: Harmonization of international safety and ethics standards—such as ISO 12100 [120], which outlines general principles for machinery risk assessment and reduction, and ISO/TS 15066 [121], which defines collaborative robot safety requirements—with learning-based models is still ongoing [112]. These standards serve as global benchmarks for ensuring that autonomous and robotic systems meet essential safety and risk-reduction criteria while interacting with humans.

- Human Perception: Models often neglect psychological dimensions such as perceived safety and emotional response.

7. Enhancing Geometric Path Planning Through Optimization and Machine Learning

8. Conclusions

Key Takeaways for Future Research

- Transformer-Based Planning: Future systems should explore integrating spatial–temporal attention mechanisms into planning pipelines to improve generalization and context-aware navigation, especially in multi-agent and partially observable environments.

- Real-Time and Embedded Efficiency: Further innovation is needed to support GPU and neuromorphic execution on power-constrained platforms, ensuring autonomy is feasible for small-scale robots and edge devices.

- Scalable Multi-Agent Coordination: Scalability remains a bottleneck. Approaches that combine decentralized optimization, learning-based approximations, and adaptive communication protocols are promising.

- Safe and Ethical Optimization: New planning frameworks should incorporate constraints and verification layers that explicitly account for safety, fairness, and human preferences, particularly when operating alongside humans.

- Standardization and Benchmarking: To assess progress meaningfully, standardized evaluation frameworks and real-world benchmarks—particularly those involving uncertainty, real-time constraints, and ethical dilemmas—must be developed.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Licardo, J.T.; Domjan, M.; Orehovački, T. Intelligent robotics—A systematic review of emerging technologies and trends. Electronics 2024, 13, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamuni, N.; Dodda, S.; Vuppalapati, V.S.M.; Arlagadda, J.S.; Vemasani, P. Advancements in Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Robotics. J. Basic Sci. Eng. 2025, 19, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, Y. Recent progress, challenges and future prospects of applied deep reinforcement learning: A practical perspective in path planning. Neurocomputing 2024, 608, 128423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakis, G.S.; Rovithakis, G.A. Motion Planning in Topologically Complex Environments Via Hybrid Feedback. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2024, 70, 3742–3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqobali, R.; Alshmrani, M.; Alnasser, R.; Rashidi, A.; Alhmiedat, T.; Alia, O.M. A survey on robot semantic navigation systems for indoor environments. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Cheng, S.; Ding, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xu, D.; Zhao, Y. A survey of optimization-based task and motion planning: From classical to learning approaches. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 30, 2799–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutikno, T. The future of artificial intelligence-driven robotics: Applications and implications. IAES Int. J. Robot. Autom. 2024, 13, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaValle, S.M. Planning Algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Choset, H.; Lynch, K.M.; Hutchinson, S.; Kantor, G.; Burgard, W.; Kavraki, L.E.; Thrun, S. Principles of Robot Motion: Theory, Algorithms, and Implementations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Perez, T. Spatial Planning: A Configuration Space Approach. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1983, 32, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ibáñez, J.R.; Pérez-del Pulgar, C.J.; García-Cerezo, A. Path planning for autonomous mobile robots: A review. Sensors 2021, 21, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-Time Obstacle Avoidance for Manipulators and Mobile Robots. Int. J. Robot. Res. 1986, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.A. A Robust Layered Control System for a Mobile Robot. IEEE J. Robot. Autom. 1986, 2, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess-Limerick, B.; Haviland, J.; Lehnert, C.; Corke, P. Reactive base control for on-the-move mobile manipulation in dynamic environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 9, 2048–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J. Hybrid sampling-based path planning for mobile manipulators performing pick and place tasks in narrow spaces. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J. An Improved RRT* Path Planning Algorithm in Dynamic Environment. In Methods and Applications for Modeling and Simulation of Complex Systems; Fan, W., Zhang, L., Li, N., Song, X., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2022; pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Amar, L.B.; Jasim, W.M. Hybrid metaheuristic approach for robot path planning in dynamic environment. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2021, 10, 2152–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Shi, P.; Zhao, Y. Adaptive connected hierarchical optimization algorithm for minimum energy spacecraft attitude maneuver path planning. Astrodynamics 2023, 7, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Jin, Z.; Wang, T.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, H. Hybrid path planning methods for complete coverage in harvesting operation scenarios. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, M.; Haddad, M. Hybrid Control Architecture for Mobile Robots Navigation in Partially Known Environments. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics (ICINCO), Vienna, Austria, 2–4 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patle, B.; Ganesh, B.L.; Pandey, A.; Parhi, D.R.K.; Jagadeesh, A. A review: On path planning strategies for navigation of mobile robot. Def. Technol. 2019, 15, 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiesdana, S. A Hybrid Method for Industrial Robot Navigation. J. Optim. Ind. Eng. 2021, 14, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanan, M.; Salgoankar, A. A survey of robotic motion planning in dynamic environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2018, 100, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegle. Real-Time Robotics Control. 2025. Available online: https://www.meegle.com/en_us/topics/robotics/real-time-robotics-control (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Chen, W.; Chi, W. A survey of autonomous robots and multi-robot navigation: Perception, planning and collaboration. Biomim. Intell. Robot. 2025, 5, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedinia, S.A.; Tale Masouleh, M. The synergy of the multi-modal MPC and Q-learning approach for the navigation of a three-wheeled omnidirectional robot based on the dynamic model with obstacle collision avoidance purposes. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2022, 236, 9716–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaghegh, M.; Saeedinia, S.; Roozbehi, Z. Optimal predictive neuro-navigator design for mobile robot navigation with moving obstacles. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1226028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Messaoud, W.; Basset, M.; Lauffenburger, J.P.; Orjuela, R. Smooth obstacle avoidance path planning for autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety (ICVES), Madrid, Spain, 12–14 September 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Betts, J.T. Practical Methods for Optimal Control and Estimation Using Nonlinear Programming; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, T. A survey of energy-efficient motion planning for wheeled mobile robots. Ind. Robot Int. J. Robot. Res. Appl. 2020, 47, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J. An improved artificial potential field UAV path planning algorithm guided by RRT under environment-aware modeling: Theory and simulation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 12080–12097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karur, K.; Sharma, N.; Dharmatti, C.; Siegel, J.E. A survey of path planning algorithms for mobile robots. Vehicles 2021, 3, 448–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yu, D.; Wang, C.; Xie, C. A smooth tool path generation and real-time interpolation algorithm based on B-spline curves. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2018, 10, 1687814017750281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simba, K.R.; Uchiyama, N.; Sano, S. Real-time smooth trajectory generation for nonholonomic mobile robots using Bézier curves. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2016, 41, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.N.; Mohanta, J. Methodology for path planning and optimization of mobile robots: A review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 133, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Lu, Y.; Savvaris, A.; Tsourdos, A. An energy-efficient path planning algorithm for unmanned surface vehicles. Ocean Eng. 2018, 161, 308–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, N. External fake constraints interpolation: The end of Runge phenomenon with high degree polynomials relying on equispaced nodes Application to aerial robotics motion planning. Indicator 2017, 2, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Villagra, J.; Milanés, V.; Rastelli, J.P.; Godoy, J.; Onieva, E. Path and speed planning for smooth autonomous navigation. In Proceedings of the IV 2012-IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, Alcalá de Henares, Spain, 3–7 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Ren, G.; Chen, J.; Ding, G.; Yang, Y. Unmanned aerial vehicle-aided communications: Joint transmit power and trajectory optimization. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2018, 7, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Anavatti, S.; Garratt, M.; Abbass, H.A. Modified continuous ant colony optimisation for multiple unmanned ground vehicle path planning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 196, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y. Vehicle navigation path optimization based on complex networks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2025, 665, 130509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, P.; Li, D.; Sun, T. Curvature continuous and bounded path planning for fixed-wing UAVs. Sensors 2017, 17, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Lefebvre, S.; Yu, K.M.; Geraedts, J.M.; Wang, C.C. Planning jerk-optimized trajectory with discrete time constraints for redundant robots. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datouo, R.; Motto, F.B.; Zobo, B.E.; Melingui, A.; Bensekrane, I.; Merzouki, R. Optimal motion planning for minimizing energy consumption of wheeled mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Macau, Macao, 5–8 December 2017; pp. 2179–2184. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, J.; Yang, C. Self-adaptive dynamic obstacle avoidance and path planning for USV under complex maritime environment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 114945–114954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reclik, D.; Kost, G. The comparison of elastic band and B-Spline polynomials methods in smoothing process of collision-free robot trajectory. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2008, 29, 187–190. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, P.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Y. Complete and time-optimal path-constrained trajectory planning with torque and velocity constraints: Theory and applications. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Han, X.; Shen, H.; Jin, H.; Shimada, K. Navrl: Learning safe flight in dynamic environments. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 3668–3675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Gupta, J.K.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Sadigh, D.; Bohg, J. Dynamic multi-robot task allocation under uncertainty and temporal constraints. Auton. Robot. 2022, 46, 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Huang, X.; Huang, R.N. Efficient deep reinforcement learning for optimal path planning. Electronics 2022, 11, 3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, P.; He, L. Time-optimal trajectory planning of serial manipulator based on adaptive cuckoo search algorithm. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2021, 35, 3171–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, R.; Kershaw, K.; Pagala, P.; Ferre, M. Model based on-line energy prediction system for semi-autonomous mobile robots. In Proceedings of the 2014 5th International Conference on Intelligent Systems, Modelling and Simulation, Langkawi, Malaysia, 27–29 January 2014; pp. 411–416. [Google Scholar]

- Palomba, I.; Wehrle, E.; Carabin, G.; Vidoni, R. Minimization of the energy consumption in industrial robots through regenerative drives and optimally designed compliant elements. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsfakhr, F.; Bigham, B.S. A neural network approach to navigation of a mobile robot and obstacle avoidance in dynamic and unknown environments. Turk. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2017, 25, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, I.J. Fuzzy Logic Decision Model for Robust Risk Management in ubiquitous environment—A Review. J. Ubiquitous Comput. Commun. Technol. 2024, 5, 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, G. Multi-objective optimal trajectory planning for manipulators in the presence of obstacles. Robotica 2022, 40, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellouk, A.; Benmachiche, A. A survey on navigation systems in dynamic environments. In Proceedings of the ICIST ’20: 10th International Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Lecce, Italy, 4–5 June 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, S. TSP-based depth-first search algorithms for enhanced path planning in laser-based directed energy. Precis. Eng. 2025, 93, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarraj, S.; Reddy, R.V.K.; Basam, M.B.; Lokesh, G.H.; Flammini, F.; Natarajan, R. Route planning for an autonomous robotic vehicle employing a weight-controlled particle swarm-optimized Dijkstra algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 92433–92442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.; Durdu, A. Comparison of optimal path planning algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Conference on Advanced Trends in Radioelecrtronics, Telecommunications and Computer Engineering (TCSET), Lviv-Slavske, Ukraine, 20–24 February 2018; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Halder, U.; Das, S.; Maity, D. A cluster-based differential evolution algorithm with external archive for optimization in dynamic environments. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2013, 43, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, S.; Bodin, B.; Wagstaff, H.; Nisbet, A.; Nardi, L.; Mawer, J.; Melot, N.; Palomar, O.; Vespa, E.; Spink, T.; et al. Navigating the landscape for real-time localization and mapping for robotics and virtual and augmented reality. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 2020–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohaghegh, M.; Jafarpourdavatgar, H.; Saeedinia, S.A. New design of smooth PSO-IPF navigator with kinematic constraints. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 175108–175121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Chen, G.; Yan, C.; Wu, Y. Path planning optimization of indoor mobile robot based on adaptive ant colony algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 156, 107230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, C.; Gao, D.; Gu, W.; Xu, L.; Goodman, E.D. A new adaptive decomposition-based evolutionary algorithm for multi-and many-objective optimization. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 213, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H. Enhancing Robot Path Planning through a Twin-Reinforced Chimp Optimization Algorithm and Evolutionary Programming Algorithm. IEEE Access 2023, 12, 170057–170078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Xiang, K.; Pang, M.; Zhanxia, Z. Multi-robot Path Planning Using an Improved Self-adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 1729881420936154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J.; Li, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, R. Many-objective evolutionary algorithm based agricultural mobile robot route planning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Qiu, S. A decomposition-based constrained multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with a local infeasibility utilization mechanism for UAV path planning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 118, 108495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T. A Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithm Based on Dimension Exploration and Discrepancy Evolution for UAV Path Planning Problem. Inf. Sci. 2024, 657, 119977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammachantuek, I.; Ketcham, M. Path planning for autonomous mobile robots using multi-objective evolutionary particle swarm optimization. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Du, Y.; Xi, X.; Zhang, K.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; Ren, C. Improved genetic algorithm based on bi-level co-evolution for coverage path planning in irregular region. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Domínguez, M.A.; García-Rojas, N.A.; Zapotecas-Martínez, S.; Hemández, R.D.; Altamirano-Robles, L. Exploring Multi-Objective Evolutionary Approaches for Path Planning of Autonomous Mobile Robots. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Yokohama, Japan, 30 June–5 July 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smierzchalski, R.; Kuczkowski, L.; Kolendo, P.; Jaworski, B. Distributed Evolutionary Algorithm for Path Planning in Navigation Situation. Transn. Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2013, 7, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, K.; Liu, Q.; Ding, K.; Gao, H.; Zhu, P.; Liu, C. SwarmPRM: Probabilistic Roadmap Motion Planning for Large-Scale Swarm Robotic Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 14–18 October 2024; pp. 10222–10228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Qiao, B.; Zhao, W.; Chen, X. A predictive path planning algorithm for mobile robot in dynamic environments based on rapidly exploring random tree. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2021, 46, 8223–8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chi, W.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Meng, M.Q.H. Neural RRT*: Learning-based optimal path planning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xia, B.; Xie, P.; Li, X.; Wang, J. NAMR-RRT: Neural Adaptive Motion Planning for Mobile Robots in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 13087–13100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jia, X.; Zhang, T.; Ma, N.; Meng, M.Q.H. Deep neural network enhanced sampling-based path planning in 3D space. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 3434–3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilullah, K.I.; Jindai, M.; Ota, S.; Yasuda, T. Fast road detection methods on a large scale dataset for assisting robot navigation using kernel principal component analysis and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 57th Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers of Japan (SICE), Nara, Japan, 11–14 September 2018; pp. 798–803. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; O’Connor, P. Learning a representation map for robot navigation using deep variational autoencoder. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.02401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, K.C.; Thakur, R. Energy-efficient clustering and path planning for UAV-assisted D2D cellular networks. Ad Hoc Netw. 2025, 170, 103757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Lu, W.; Han, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhang, M. Heterogeneous dimensionality reduction for efficient motion planning in high-dimensional spaces. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 42619–42632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, L.; Stachniss, C. Uncertainty-aware path planning for navigation on road networks using augmented MDPs. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 5780–5786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Zhang, T. Deep reinforcement learning based mobile robot navigation: A review. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2021, 26, 674–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.R.; Thomas, H.; Zhang, J.; Rhinehart, N.; Barfoot, T.D. DR-MPC: Deep Residual Model Predictive Control for Real-World Social Navigation. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2025, 10, 4029–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, T.; Lei, T.; Jan, G.E.; Wang, Y.; Luo, C. Multi-objective optimization robot navigation through a graph-driven PSO mechanism. In Advances in Swarm Intelligence; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, J.; Qin, L.; Hu, Y.; Yin, Q.; Hu, C. Integrating a path planner and an adaptive motion controller for navigation in dynamic environments. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, H.Y.; Toma, A.I.; Ali Jaafar, H.; Stow, E.; Murai, R.; Kelly, P.H.; Saeedi, S. Systematic comparison of path planning algorithms using PathBench. Adv. Robot. 2022, 36, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hua, Y. Path planning of mobile robot based on hybrid improved artificial fish swarm algorithm. Vibroengineering Procedia 2018, 17, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ou, J.; Hong, S.H.; Song, G.; Wang, Y. Hybrid path planning based on adaptive visibility graph initialization and edge computing for mobile robots. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2023, 126, 107110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Li, G.; Liao, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Yan, X.; Yang, M.; Li, S. Multi-strategy hybrid adaptive dung beetle optimization for path planning. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Swartz, C.L.; Huang, K. Deep learning-based model predictive control for real-time supply chain optimization. J. Process. Control 2023, 129, 103049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Qiu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Shi, Q.; Huang, H.W.; Huang, Q.; Fukuda, T. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Collision-Free Navigation for Magnetic Helical Microrobots in Dynamic Environments. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 7810–7820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murano, A.; Perelli, G.; Rubin, S. Multi-agent path planning in known dynamic environments. In PRIMA 2015: Principles and Practice of Multi-Agent Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 218–231. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S.; Indelman, V.; Kaess, M.; Roberts, R.; Leonard, J.J.; Dellaert, F. Concurrent filtering and smoothing: A parallel architecture for real-time navigation and full smoothing. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2014, 33, 1544–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhoun, R.; Taha, T.; Seneviratne, L.; Dias, J.; Cai, G. GPU Accelerated Coverage Path Planning Optimized for Accuracy in Robotic Inspection Applications. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 59th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 16–19 October 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastgar, F. Towards Reliable Real-Time Trajectory Optimization. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Chen, N.; Liu, G.; Xu, C.; Gao, F.; Cao, Y. TOP: Trajectory Optimization via Parallel Optimization towards Constant Time Complexity. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastider, A.; Ray, A. Retro-trajectory optimization: A memory-efficient warm-start approach. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 1105–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.; Andrew, A.; Evangelos A, T. Model predictive path integral control: From theory to parallel computation. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICRA, Singapore, 29 May–3 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Ma, Y.; Song, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, X. A Real-Time Spatio-Temporal Trajectory Planner for Autonomous Vehicles with Semantic Graph Optimization. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2024, 10, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, J.; Cabral, K.; Givigi, S.; Marshall, J. Real-Time Fast Marching Tree for Mobile Robot Motion Planning in Dynamic Environments. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.09556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegle. GPU Acceleration in Autonomous Navigation. 2025. Available online: https://www.meegle.com/en_us/topics/gpu-acceleration/gpu-acceleration-in-autonomous-navigation (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Einfochips. GPU-Accelerated Real-Time SLAM Optimization for Autonomous Robots; Einfochips: San Jose, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y. GPU-Enabled Genetic Algorithm Optimization and Path Planning for Robotic Manipulators. Master’s Thesis, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Jiang, F.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Sha, K.; Chen, J. Deep learning-enhanced environment perception for autonomous driving: MDNet with CSP-DarkNet53. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 160, 111174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, C.; Mascarich, F.; Khattak, S.; Dang, T.; Alexis, K. Localization uncertainty-aware autonomous exploration and mapping with aerial robots using receding horizon path-planning. Auton. Robot. 2019, 43, 2131–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosenzo, K.A.; Barnes, M.J. Human–robot interaction research for current and future military applications: From the laboratory to the field. In Unmanned Systems Technology XII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7692, pp. 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, K.; Harper, R.; Leonards, U. Towards ethical robots: A survey of existing paradigms. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Advanced Robotics, Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martinetti, A.; van Wingerden, J.W.; Nizamis, K.; Fosch-Villaronga, E. Redefining safety in human-robot interaction: From physical protection to social understanding. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 666237. [Google Scholar]

- Valori, A.; Mendes, A. Validating robot safety protocols with international ISO standards: Challenges and best practices. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Boulder, CO, USA, 8–11 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Yan, S.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.V.; Wang, L. Safety-Aware Human-Centric Collaborative Assembly. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 60, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geißlinger, M.; Poszler, F.; Lienkamp, M. An ethical trajectory planning algorithm for autonomous vehicles. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.; Dsouza, S.; Kim, R.; Schulz, J.; Henrich, J.; Shariff, A.; Bonnefon, J.; Rahwan, I. The moral machine experiment. Nature 2018, 563, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, H. CCPF-RRT*: An improved path planning algorithm with potential function-based sampling heuristic considering congestion. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 162, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Application of Machine Learning in Ethical Design of Autonomous Driving Crash Algorithms. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 2938011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Held, D.; Tian, A.; Abbeel, P. Constrained policy optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P.; Parasuraman, R.; Doshi, P. Integrating Perceptions: A Human-Centered Physical Safety Model for Human–Robot Interaction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.06700. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12100; Safety of Machinery—General Principles for Design—Risk Assessment and Risk Reduction. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- ISO/TS 15066; Robots and Robotic Devices—Collaborative Robots. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Hess, R.; Jerg, R.; Lindeholz, T.; Eck, D.; Schilling, K. SRRT*—A Probabilistic Optimal Trajectory Planner for Problematic Area Structures. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Da, C. Global and local path planning of robots combining ACO and dynamic window algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Mathematical Definition | Parameters and Description | Computational Complexity | Applicability & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bézier Curve [32,34] | (control points), n (degree). Smooth curve defined by control points. | Low | Easy to implement; good for offline planning; limited flexibility for complex dynamic obstacles. | |

| Elastic Stretching [46] | (curvature), s (arc length). Minimizes total squared curvature. | Medium | Produces very smooth paths; may be computationally heavy for long paths; sensitive to obstacle density. | |

| Minimum Angle Difference [32] | (angle at waypoint i). Minimizes angular difference. | Low | Simple and fast; may not fully smooth paths in complex environments. | |

| Curvature Continuity [42] | (derivative of curvature). Ensures continuous curvature. | Medium–High | Smooth trajectories with continuity; requires more computation; may struggle with dense obstacles. | |

| Jerk Minimization [43] | (jerk at time t). Minimizes jerk. | Medium | Improves robot stability and comfort; may be computationally intensive in real-time control. | |

| Energy-Efficient Smoothing [44] | (force or energy as a function of velocity). Optimizes energy usage. | Medium–High | Useful for battery-constrained robots; trade-off with path length or time efficiency. | |

| Adaptive Smoothing [45] | (curvature at arc length s and time t). Adjusts smoothness dynamically. | High | Suitable for dynamic environments; computationally demanding; requires real-time updates. |

| Approach/Algorithm | Application Area | Main Advantages/Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Twin-Reinforced Chimp Optimization + Evolutionary Programming | Robot path planning | Outperforms other meta-heuristics in path length, consistency, time complexity, and success rate | [66] |

| Improved PSO with Evolutionary Operators (IPSO-EOPs) | Multi-robot navigation | Superior to DE and standard PSO in arrival time, safety, and energy use | [67] |

| Many-Objective EAs (HypE, GrEA, KnEA, NSGA-III) | Agricultural robot route planning | HypE delivers best performance for minimizing navigation cost and turning angle | [68] |

| Decomposition-based Multi-Objective EA (M2M-DW) | UAV path planning | Effectively handles constraints and infeasible solutions, reliable in complex scenarios | [69,70] |

| Multi-Objective Evolutionary PSO (MOEPSO) | Mobile robot path planning | Finds shortest, smoothest, and safest paths in static and dynamic environments | [71] |

| Bi-level Co-evolutionary Genetic Algorithm (IGA-CPP) | Coverage path planning | Efficient for irregular regions, fast convergence, optimized path length | [72] |

| NSGA-II and Multi-Objective EAs | Mobile robot navigation | NSGA-II excels in balancing path time and smoothness across diverse environments | [73] |

| Distributed Multi-Population EA | Maritime navigation | Multi-population approach improves solution quality over single-population EAs | [74] |

| Method | Formula | Parameter Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptive RRT* [80] |

| |

| Deep Sampling-Based Planner [81] |

| |

| Reward-Adaptive Sampling (extension of [82,83]) |

| |

| NAMR-RRT (Neural Adaptive and Multi-Risk RRT) [80,81,84] | Integrates neural guidance and risk-awareness into RRT*, adapts sampling with dynamic obstacle metrics, and manages uncertainty. | Adapts neural risk-weighted sampling for complex and dynamic regions. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jafarpourdavatgar, H.; Saeedinia, S.A.; Mohaghegh, M. Geometrical Optimal Navigation and Path Planning—Bridging Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226874

Jafarpourdavatgar H, Saeedinia SA, Mohaghegh M. Geometrical Optimal Navigation and Path Planning—Bridging Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226874

Chicago/Turabian StyleJafarpourdavatgar, Hedieh, Samaneh Alsadat Saeedinia, and Mahsa Mohaghegh. 2025. "Geometrical Optimal Navigation and Path Planning—Bridging Theory, Algorithms, and Applications" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226874

APA StyleJafarpourdavatgar, H., Saeedinia, S. A., & Mohaghegh, M. (2025). Geometrical Optimal Navigation and Path Planning—Bridging Theory, Algorithms, and Applications. Sensors, 25(22), 6874. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226874