Research on a Cooperative Grasping Method for Heterogeneous Objects in Unstructured Scenarios of Mine Conveyor Belts Based on an Improved MATD3

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Delayed update mechanism: Reduce the update frequency of the actor network to suppress the instability caused by strategy mutations.

- (2)

- Target strategy smoothing: Mitigate Q-value overestimation issues by injecting action noise.

- ①

- Design a reward function with multiple factors and constraints to accelerate the convergence of the robotic arm in the continuous motion space, thereby improving the real-time performance of the grasping trajectory for heterogeneous targets.

- ②

- Introduce a priority experience replay (PER) mechanism to accelerate strategy convergence to the optimal solution and enhance environmental dynamic adaptability through adaptive adjustment of sample priority weights and efficient reuse of experience data;

- ③

- For slender objects, a sequence cooperative optimization strategy is developed to improve grasp-and-place stability and reliability.

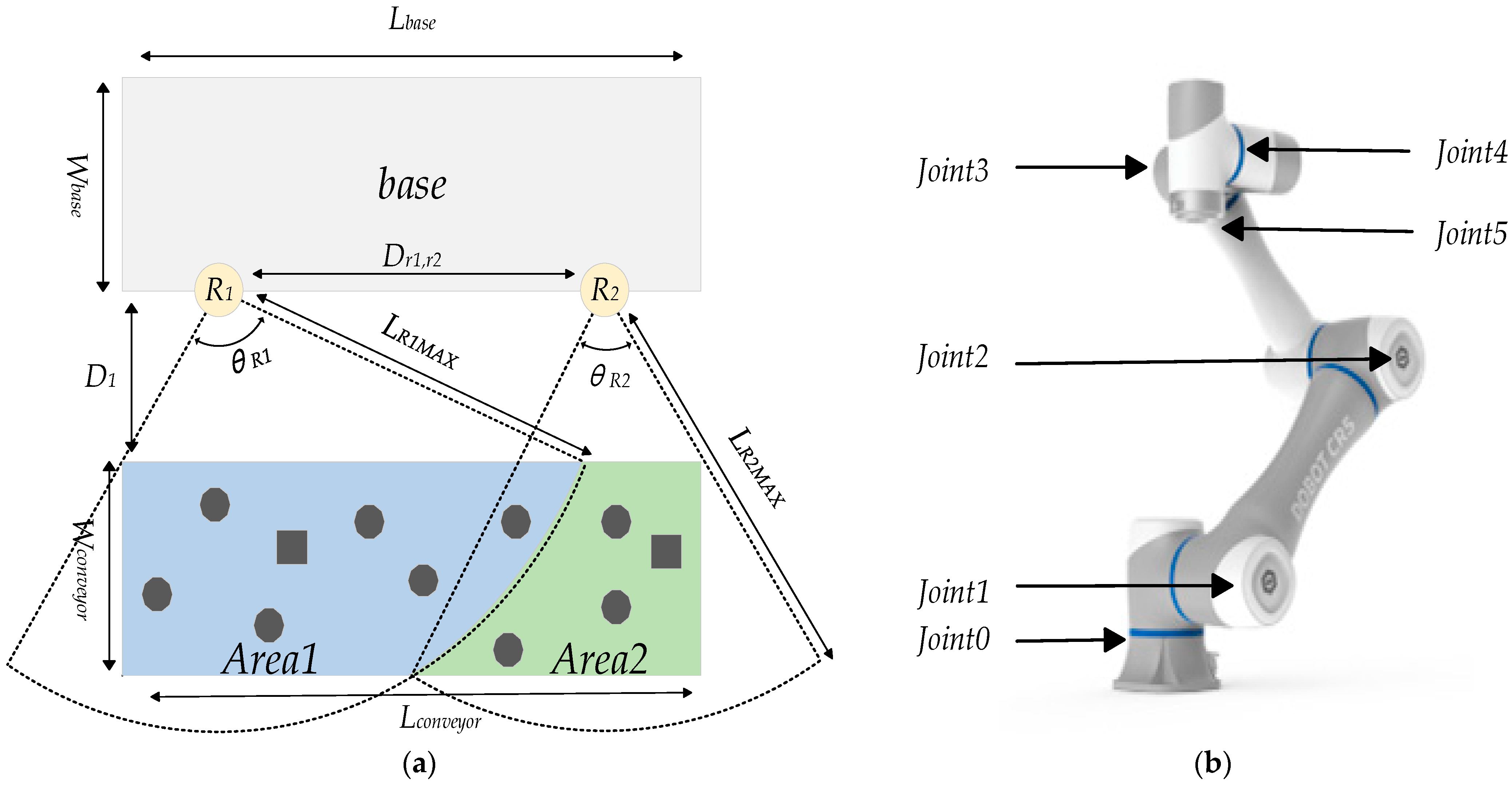

2. Problem Setting

2.1. Background and Setting

2.2. Dual-Arm System Constraint Settings

2.2.1. End-Effector Grasping Pose Constraints

2.2.2. Motion Amplitude Constraint

2.2.3. Cooperative Constraints in the Dual-Arm Cooperative Control Stage

2.3. Problem Statement

3. Method

3.1. Definition of State Space and Action Space

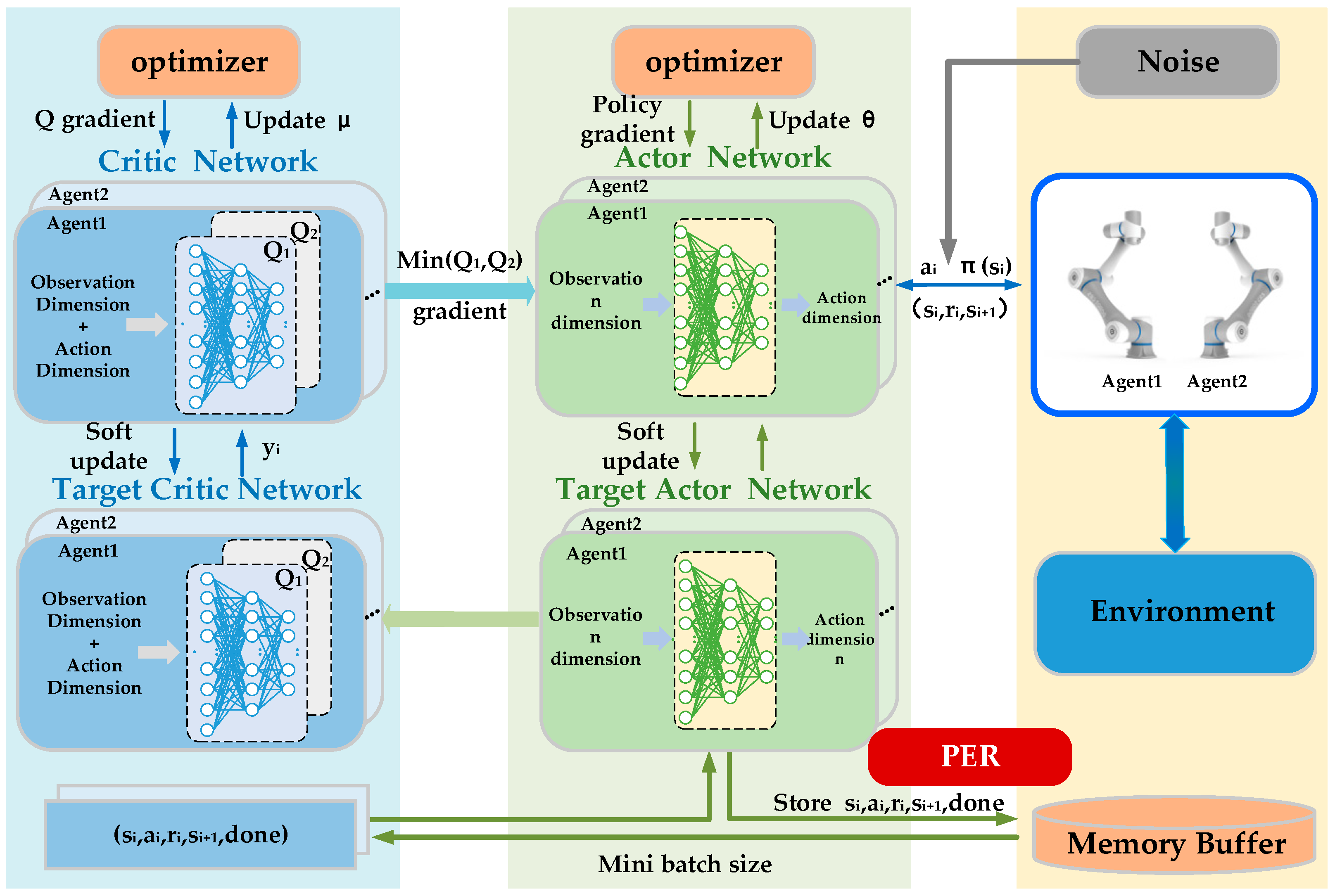

3.2. Control Strategies and Network Structures

3.2.1. Neural Network Structure

3.2.2. Reward Function Design

- (1)

- Distance component: . Assuming that the current position of the end effector of the robotic arm is , the target point position is , and represents the deviation vector between the current position and the target positions:

- (2)

- Collision part: In this study, collisions consist of three parts: self-collisions of the robotic arm, collisions between robotic arms, and collisions between the robotic arm and static obstacles. The reward function for this part is defined as shown in Equation (17):

- (3)

- Guidance reward component: In this study, a guidance reward mechanism was designed to enable the robotic arm to approach the target point quickly and efficiently. Assuming that the distance error at time t − 1 is and the distance error at the current time is :

- (4)

- Completion part: In this study, each training round is defined as having time steps, and the number of times the robotic arm completes the task is defined as N. When the end-effector distance error is , it is considered that the robotic arm has completed the task once, N + 1. When 50 consecutive completions are achieved within t time steps, it is considered that the task for this round is completed, and a reward is given to incentivize the robotic arm to perform the task better. In this study, is 10. The mathematical expression is shown in Equation (19):

3.2.3. Priority Experience Replay

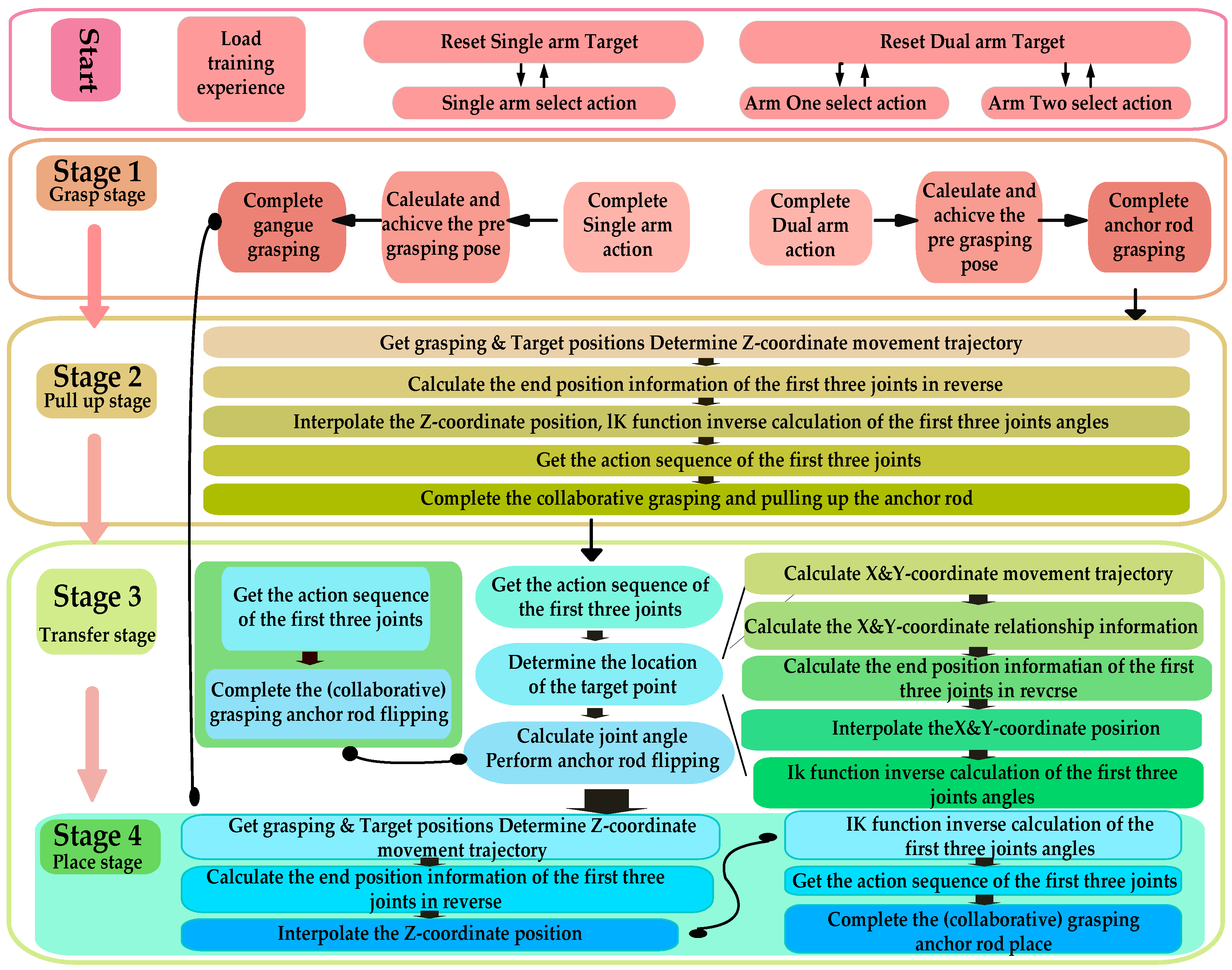

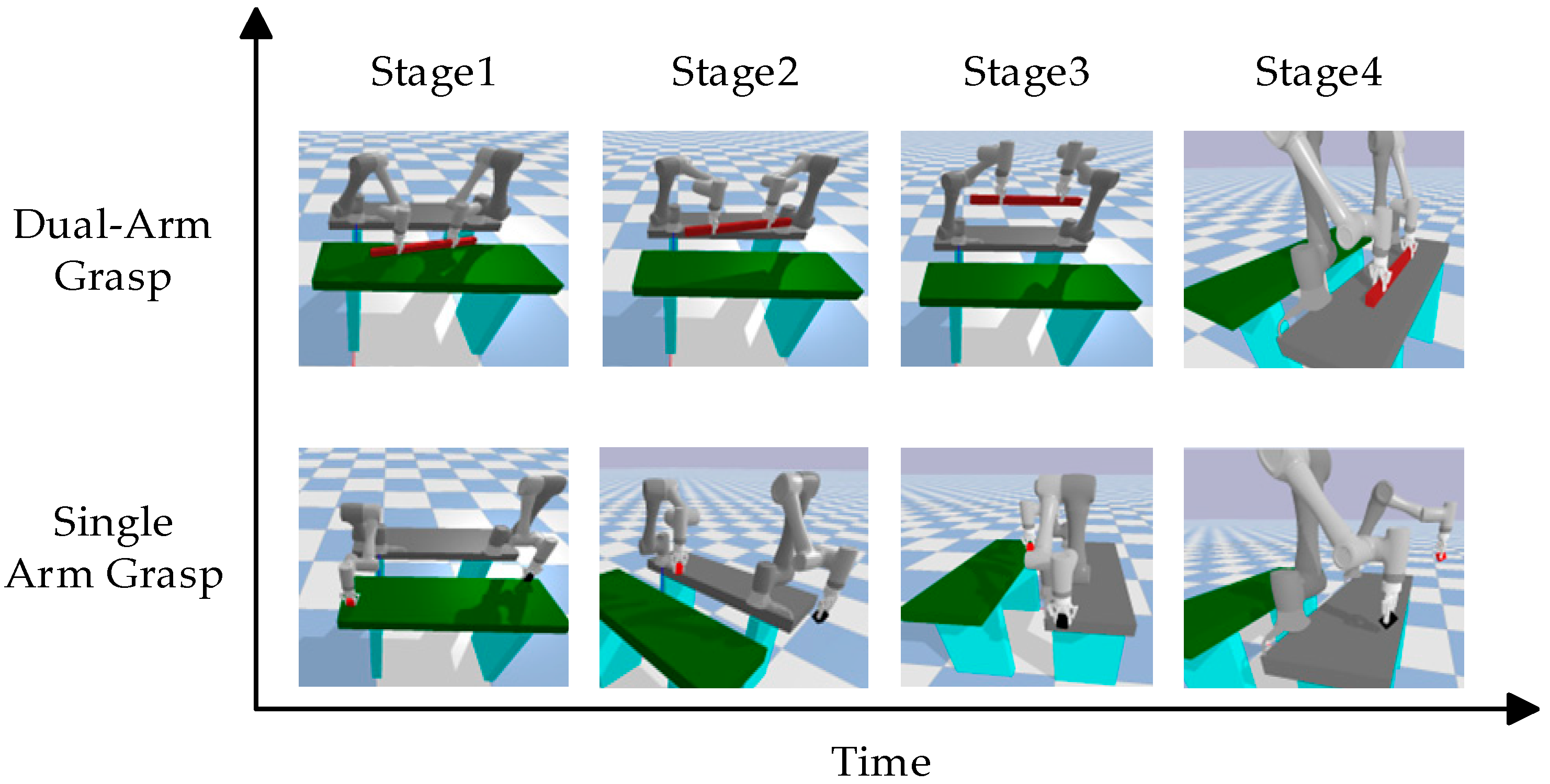

3.2.4. Research on Sequence Cooperative Optimization Strategy

- (1)

- Model Experience Accumulation Stage: Periodic strategy evaluations are conducted during training, with experimental models saved at each time step to monitor performance changes and facilitate future utilization. The evaluation cycle spans 5000 time steps.

- (2)

- Grasp Stage: The primary objectives are to drive the robotic arm based on the pre-trained model to reach the pre-grasping position; to obtain the position where the foreign object’s model is imported; and to calculate the robot arm’s pose for grasping the foreign objects based on the imported model position and execute the grasp.

- (3)

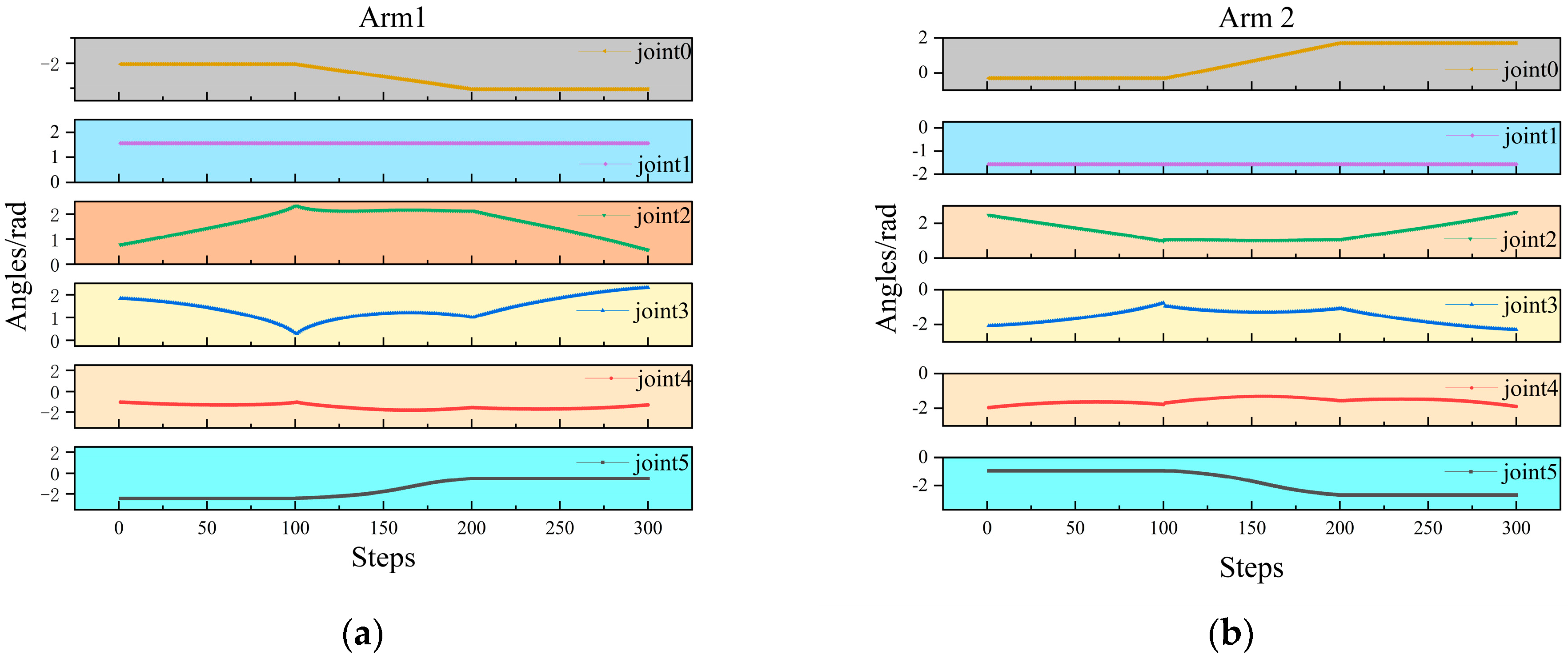

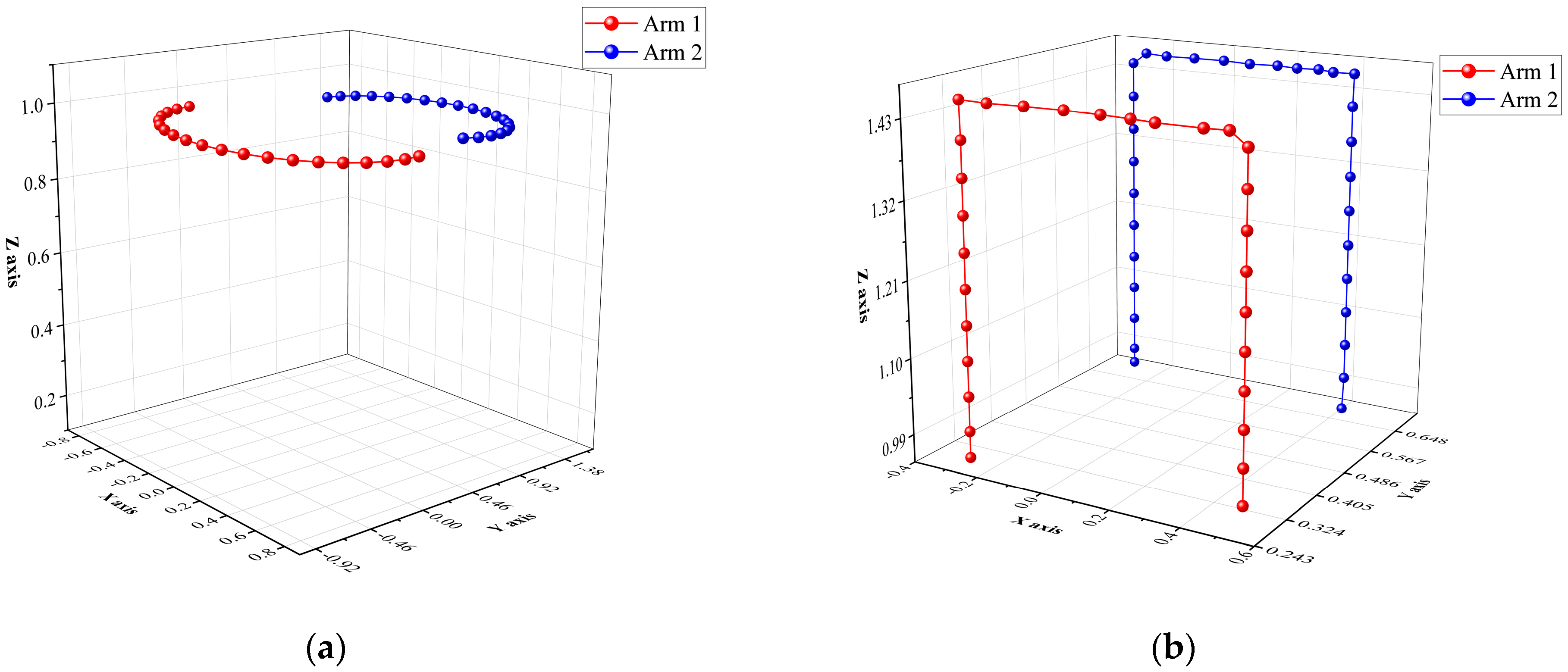

- Pull Up Stage: To prevent large foreign objects from damaging the conveyor belt during movement and causing safety incidents, foreign objects placement requires three stages: ascent, transfer, and placement. The primary objective of the lifting phase is to achieve the following: stable vertical ascent of the robotic arm while gripping the foreign objects. Since only the z-axis coordinate changes during this process, while the x, y-axis coordinates remain constant, the end-effector’s coordinates and the robotic arm’s elbow joint coordinates are relatively fixed. Therefore, defining the end-effector’s coordinate changes equates to defining the elbow joint’s x,y-coordinate changes. This enables the precise motion trajectory of the robotic arm during the lifting phase to be obtained through interpolation and inverse kinematics. The specific mathematical derivation and calculation process will be presented in the subsequent part of this subsection.

- (4)

- Transfer Stage: The objective of this phase is to transfer the foreign objects from the conveyor belt area (x > 0) to the safe placement area (x < 0). During this process, the x-coordinate decreases while the y- and z-coordinates remain constant. The end-of-arm coordinates can be derived mathematically from the end-of-arm coordinates. Similar to the ascent phase, the precise motion trajectory of the robotic arm can be obtained through interpolation and inverse kinematics calculations.

- (5)

- Place Stage: The objective of this phase is to safely place the foreign objects. The z-axis coordinate continuously decreases, and the process is similar to the ascent phase, so it will not be repeated here.

- (1)

- Single-arm Independent Grasping Experiment Design

| Algorithm 1: Single-arm grasp |

|

Load model experience Initialize model parameters For episodes in episodes_limit do Reset environment For step in step_limit do for agent_id in 2 do if done_flags[agent_id] == True then agent[agent_id] hold action else agent[agent_id] choose action End if End for obs_next_n, rewards, done_n = step(a_n) obs_n = obs_next_n If all agents done then While not grip_done grip step simulation and delay End while Set move_action Execute action Break End if End for End for |

- (2)

- Experimental Design for Dual-arm Cooperative Grasping

| Algorithm 2: Dual-arm coordinated grasp |

| Load model experience Initialize model parameters For episodes in episodes_limit do Reset environment For step in step_limit do for agent_id in 2 do if done_flags[agent_id] == True then agent[agent_id] hold action else agent[agent_id] choose action End if End for obs_next_n, rewards, done_n = step(a_n) obs_n = obs_next_n If all agents done then Calculate the grasping position Execute anchor grasping sequence while not gripper_anchor_done grip anchor step simulation and delay End while Calculate the upward sequence for agent_id in 2 do Execute anchor upward trajectory End for Step simulation and delay Calculate the turn sequence for agent_id in 2 do Execute anchor turn trajectory End for Step simulation and delay Calculate the down sequence for agent_id in 2 do Execute anchor down trajectory End for Break End if End for End for |

- (3)

- Pull up stage

- (4)

- Transfer stage

- (5)

- Place stage

4. Experimental Verification

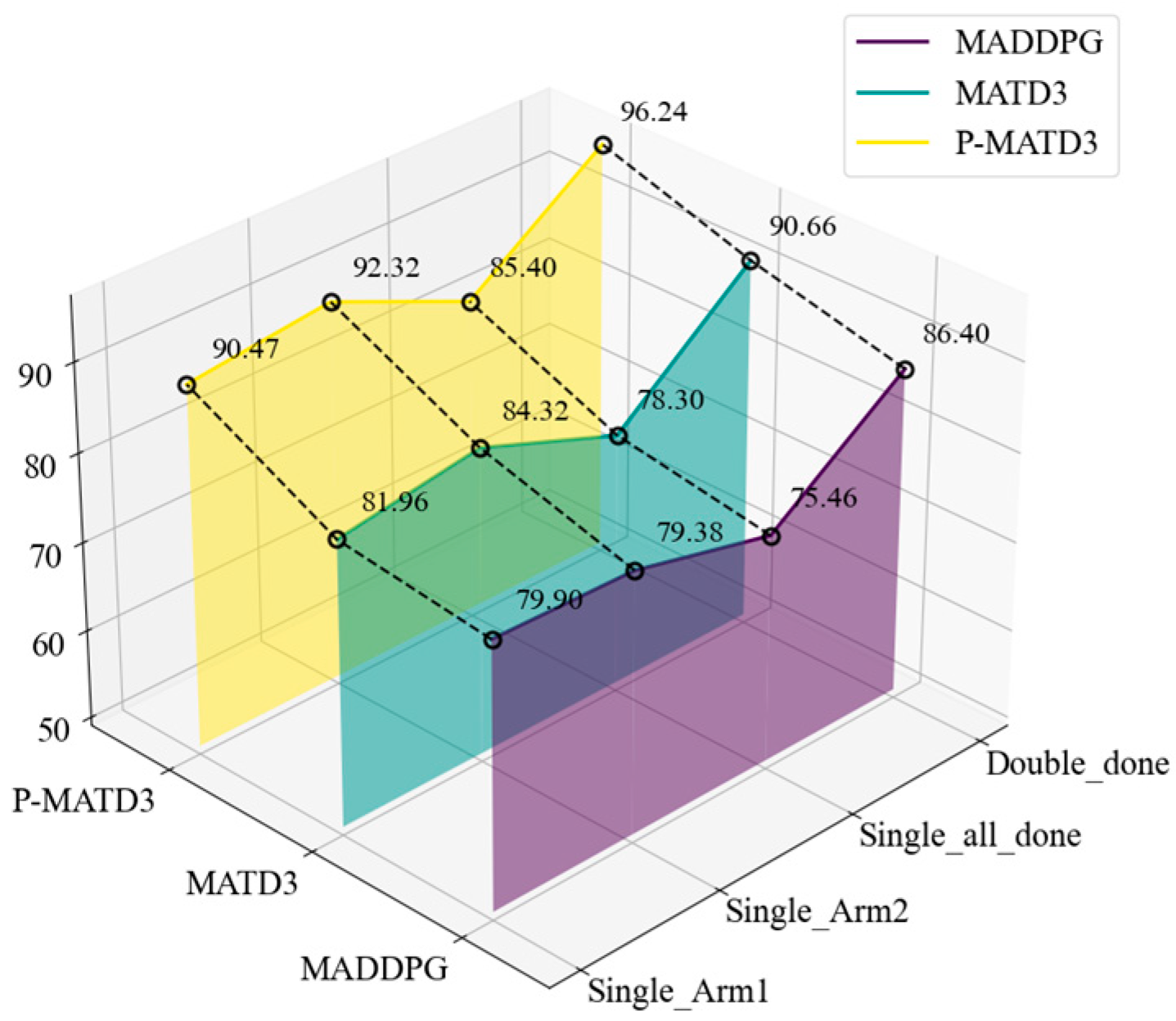

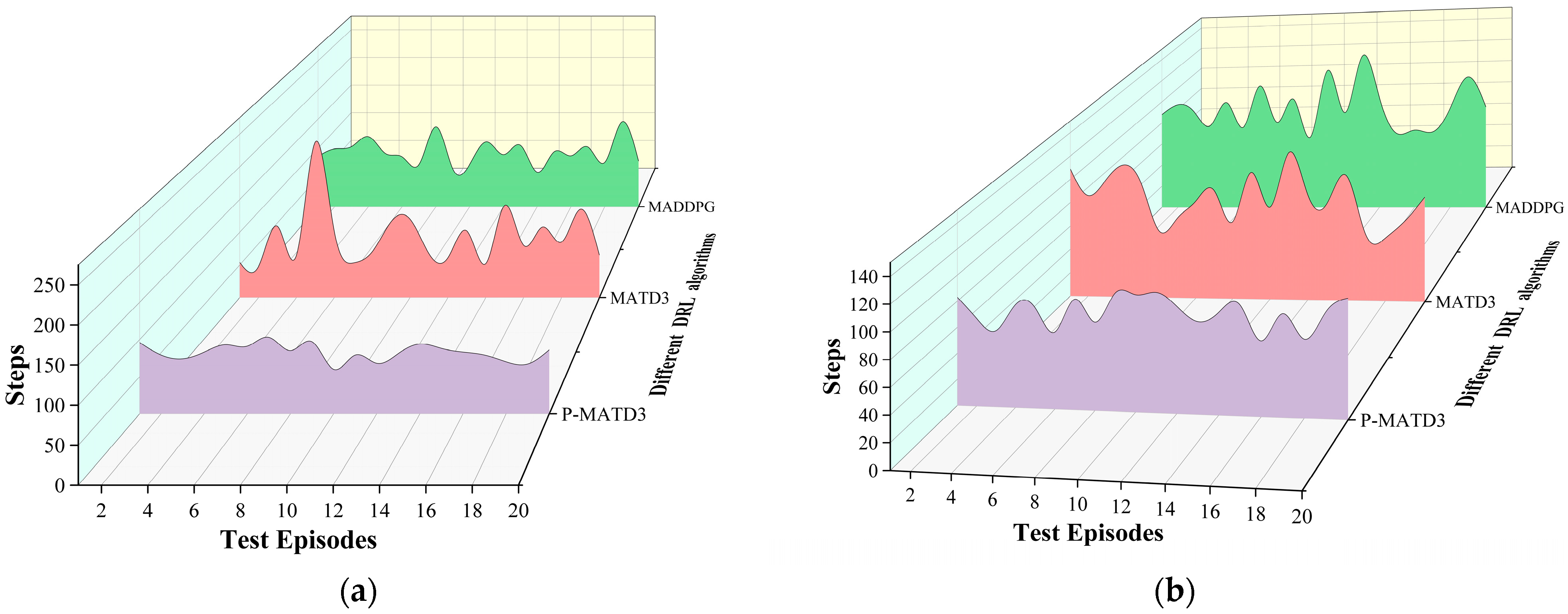

- (1)

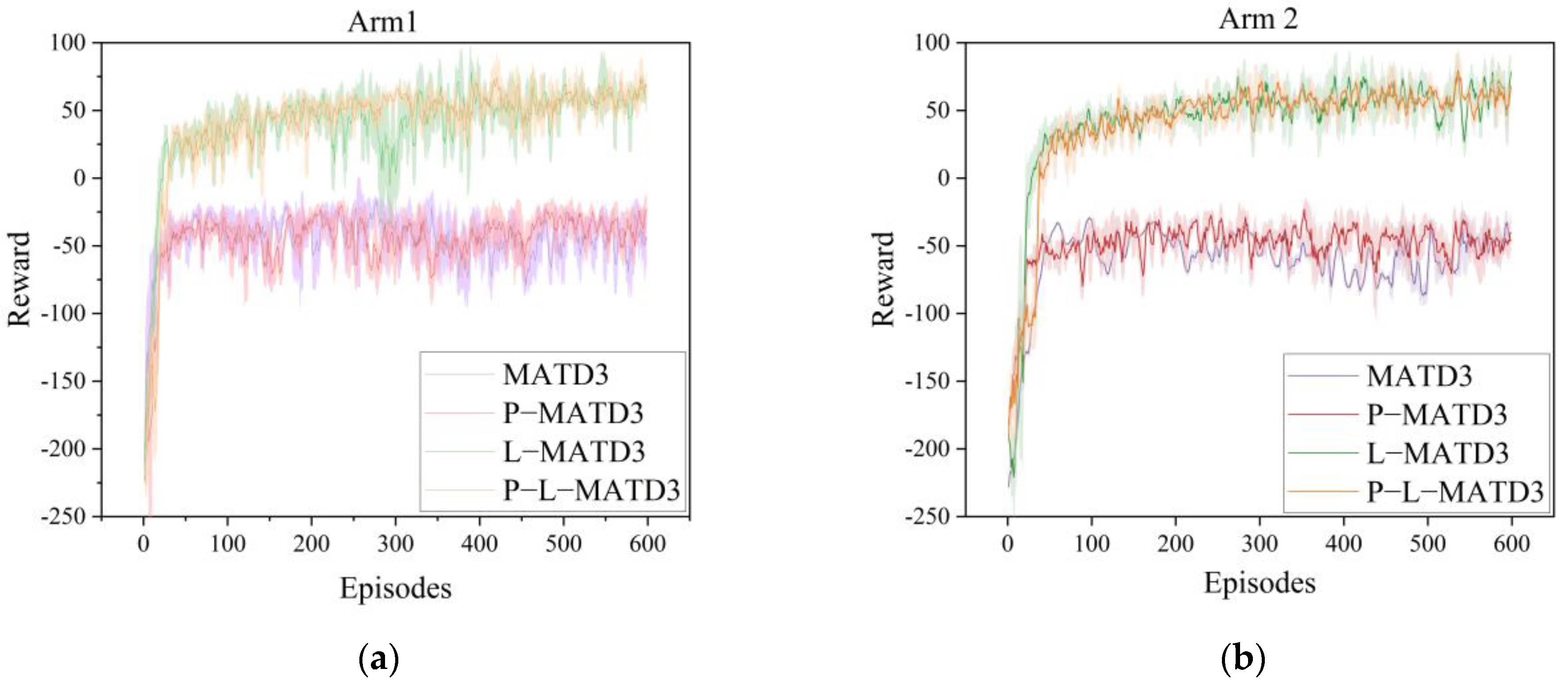

- Comparison of different DRL algorithms in terms of training and capture effectiveness.

- (2)

- Analysis of module contributions

5. Conclusions and Future Work

5.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Designing a reward function that integrates multiple factors and constraints to accelerate convergence and optimize grasping trajectories;

- (2)

- Introducing a priority experience replay mechanism into the algorithm, significantly enhancing sample utilization and policy learning efficiency;

- (3)

- Proposing a sequential cooperative optimization strategy for slender heterogeneous objects to enhance stability during grasping and placement.

5.2. Future Work and Challenges Ahead

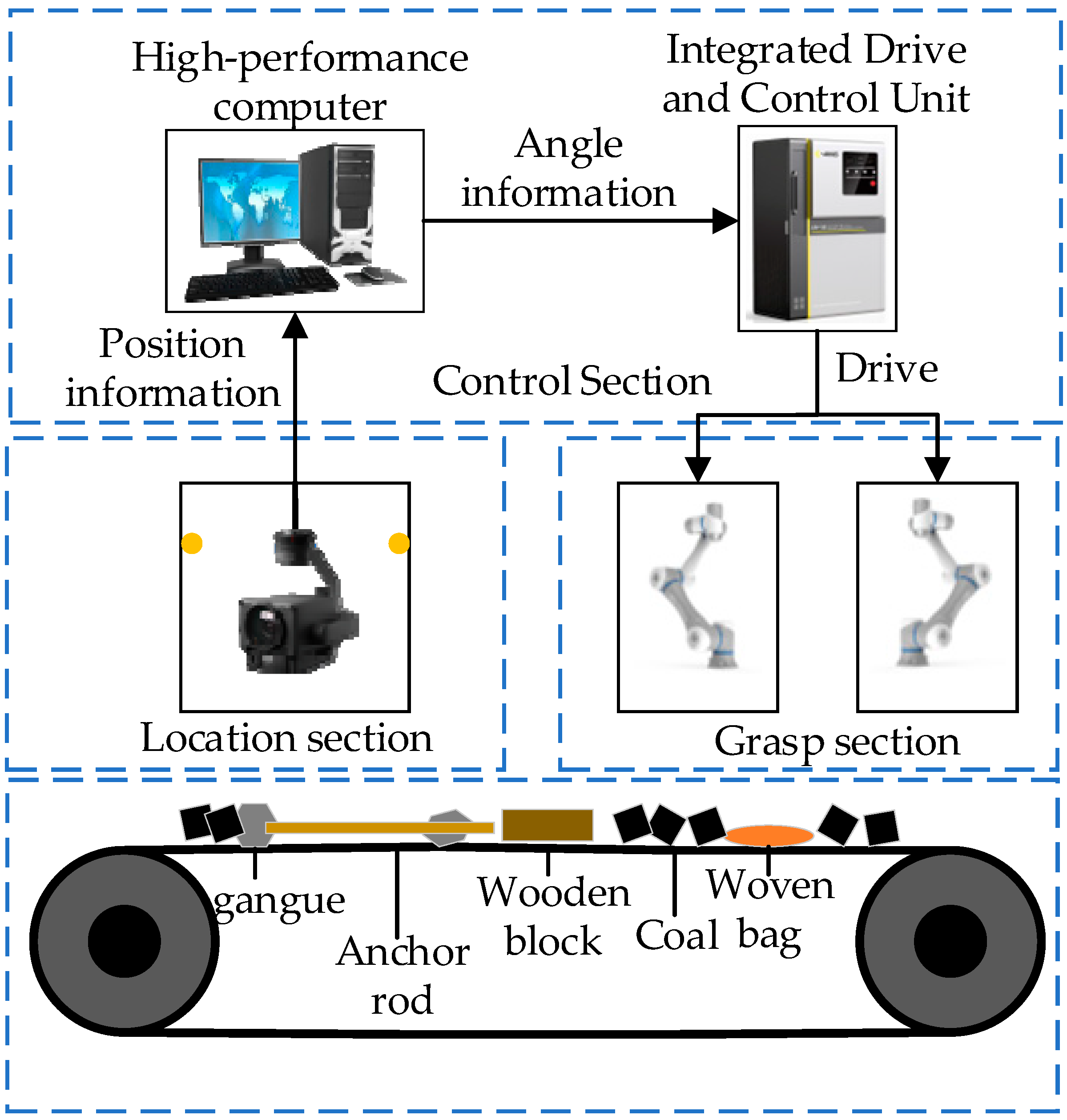

- (1)

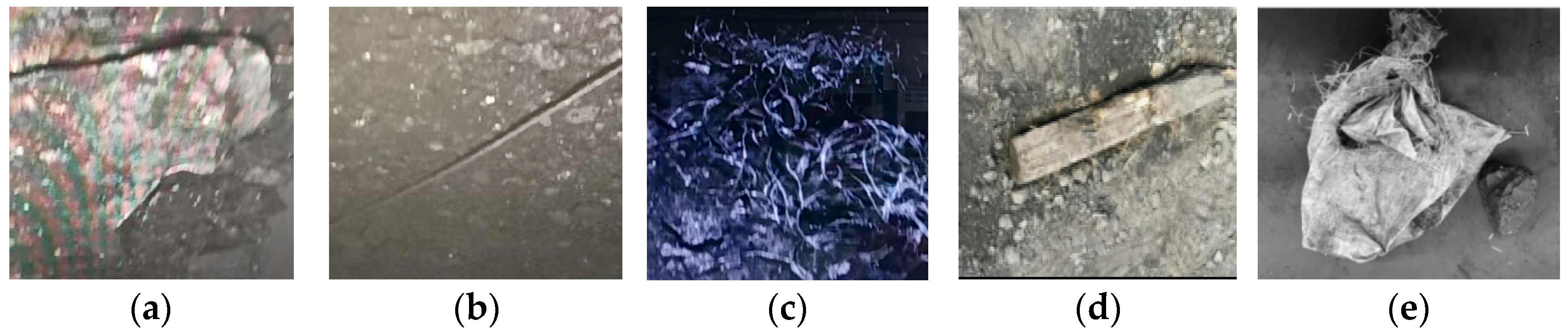

- Positioning Component: This component utilizes deep learning-based image recognition technology to capture coal foreign object information at predetermined intervals along the conveyor belt. It records foreign object labels in real-time and transmits them to the control component. During operation, an industrial camera is positioned at the top center of the frame, with optimal capture frequency calibrated to enhance foreign object location detection.

- (2)

- Control Module: This component encompasses model training, model loading, task strategy formulation, and trajectory planning. First, the enhanced deep reinforcement learning algorithm is trained and tested in a 1:1 simulation environment to achieve a specified accuracy threshold. During operation, the highest-performing model from training is loaded. It receives coal foreign object position queue information from the positioning module, then employs the trained model to formulate task strategies and plan trajectories, generating optimal grasping strategies in the simulation. Specifically, based on foreign object location and status data, it decides whether to deploy dual-arm grasping and assign tasks. Finally, it sends collision-free grasping trajectories to the control unit, directing the robotic arm to grasp foreign objects in coal like gangue, anchor rods, and wood blocks. Additionally, to comply with industrial standards and ensure experimental safety, an emergency stop button and a virtual fence will be installed on the robotic arm control unit.

- (3)

- This section’s function is to execute the angular commands sent by the control unit. When a target foreign object can be grasped by a single robotic arm, the arm moves to the grasping position, performs the grasp, and safely deposits the object. When a target foreign object requires collaborative grasping, both robotic arms move to the pre-grasping positions. After grasping is completed, a sequential strategy is executed to ensure the foreign object is safely deposited.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Z.; Xue, R.; Yuan, L.; Yu, Y.; Ding, N.; Liu, M.; Gao, B.; Sun, J.; Zheng, X.; Wang, G. Multi-agent Embodied AI: Advances and Future Directions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.05108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Cao, X.; Nie, Z.; Wei, X.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, M. On the Academic Ideology of “Sorting the Gangue is Sorting the Images”. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 53, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Chu, X.; Liu, C.; Wu, W. A Novel Model Predictive Artificial Potential Field Based Ship Motion Planning Method Considering COLREGs for Complex Encounter Scenarios. ISA Trans. 2022, 134, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Zhou, H.; Xu, T. Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning of 6-DOF Robotic Arm Based on Improved A* Algorithm and Artificial Potential Field Method. Robotica 2024, 42, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhu, X.; Meng, D.; Wang, X.; Liang, B. An Overall Configuration Planning Method of Continuum Hyper-Redundant Manipulators Based on Improved Artificial Potential Field Method. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2021, 6, 2461–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Li, T.; Sang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, K. Path Planning for Obstacle Avoidance of Robot Arm Based on Improved Potential Field Method. Sensors 2023, 23, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-I.; Shodiq, M.A.F.; Hsieh, M.-F. Robot Path Planning Based on Three-Dimensional Artificial Potential Field. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 135, 109210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, S.; van Hoof, H.; Meger, D. Addressing Function Approximation Error in Actor-Critic Methods. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholmsmässan, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1587–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Völz, A.; Graichen, K. An Optimization-Based Approach to Dual-Arm Motion Planning with Closed Kinematics. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Madrid, Spain, 1–5 October 2018; pp. 7649–7654. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Zhu, X.; Li, T.; Sang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, K. An Improved Path Planning Algorithm Based on Artificial Potential Field and Primal-Dual Neural Network for Surgical Robot. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 226, 107132. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Jeong, E.; Oh, M.; Oh, C. Driving Aggressiveness Management Policy to Enhance the Performance of Mixed Traffic Conditions in Automated Driving Environments. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 121, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, X.; He, S.; He, J.; Xu, Z. An Improved Artificial Potential Field Method of Trajectory Planning and Obstacle Avoidance for Redundant Manipulators. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2018, 15, 1729881418799562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Welleck, S.; West, P.; Jiang, L.; Kasai, J.; Khashabi, D.; Le Bras, R.; Qin, L.; Yu, Y.; Zellers, R.; et al. NeuroLogic A*esque Decoding: Constrained Text Generation with Lookahead Heuristics. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA, 10–15 July 2022; pp. 780–799. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Chen, W.-N.; Gu, T.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. ACO-A*: Ant Colony Optimization Plus A* for 3-D Traveling in Environments With Dense Obstacles. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2019, 23, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Hou, X.; Yang, J. Surface Optimal Path Planning Using an Extended Dijkstra Algorithm. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 147827–147838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarahari, M.; Khanmirza, E.; Doostie, S. Multi-objective Multi-robot Path Planning in Continuous Environment Using an Enhanced Genetic Algorithm. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 115, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Chen, K.; Li, C. Robotic Arm Trajectory Optimization Based on Multiverse Algorithm. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 20, 2776–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekrem, O.; Aksoy, B. Trajectory Planning for a 6-Axis Robotic Arm with Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 122, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Wei, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, X.; Zhou, W. Multi-Arm Global Cooperative Coal Gangue Sorting Method Based on Improved Hungarian Algorithm. Sensors 2022, 22, 7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chi, W.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Meng, M.Q.-H. Neural RRT*: Learning-Based Optimal Path Planning. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2020, 17, 1748–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, J. BI-RRT*: An Improved Path Planning Algorithm for Secure and Trustworthy Mobile Robots Systems. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, I.-B.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, J.-H. Quick-RRT*: Triangular Inequality-Based Implementation of RRT* with Improved Initial Solution and Convergence Rate. Expert Syst. Appl. 2019, 123, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Yang, H.; Sun, H. MOD-RRT*: A Sampling-Based Algorithm for Robot Path Planning in Dynamic Environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 7244–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Wan, F.; Hua, Y.; Ma, R.; Zhu, S.; Qing, X. F-RRT*: An Improved Path Planning Algorithm with Improved Initial Solution and Convergence Rate. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 184, 115457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Cong, M.; Wang, M.; Du, Y.; Liu, D. HB-RRT: A Path Planning Algorithm for Mobile Robots Using Halton Sequence-Based Rapidly-Exploring Random Tree. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qi, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z. Dynamic Parallel Mapping and Trajectory Planning of Robot Arm in Unknown Environment. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 10970–10982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Xu, J. A Sampling-Based Unfixed Orientation Search Method for Dual Manipulator Cooperative Manufacturing. Sensors 2022, 22, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Xu, J. A Novel Non-Collision Path Planning Strategy for Multi-Manipulator Cooperative Manufacturing Systems. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 3299–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y.; LeCun, Y.; Sahani, M.; Precup, D.; Silver, D.; Sugiyama, M.; Uchibe, E.; Morimoto, J. Deep Learning, Reinforcement Learning, and World Models. Neural Netw. 2022, 152, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Ding, S. A Survey on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning: From the Perspective of Challenges and Applications. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2021, 54, 3215–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munikoti, S.; Agarwal, D.; Das, L.; Halappanavar, M.; Natarajan, B. Challenges and Opportunities in Deep Reinforcement Learning with Graph Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Algorithms and Applications. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 15051–15071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, L.; Xu, P.; Shen, Y.; Tang, Q. A Task-Adaptive Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Dual-Arm Robot Manipulation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 466–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Deng, H.; Pan, Z. MRCDRL: Multi-Robot Coordination with Deep Reinforcement Learning. Neurocomputing 2020, 406, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Prianto, E.; Kim, M.; Park, J.-H.; Bae, J.-H.; Kim, J.-S. Path Planning for Multi-Arm Manipulators Using Deep Reinforcement Learning: Soft Actor–Critic with Hindsight Experience Replay. Sensors 2020, 20, 5911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cheng, C.; Ai, H.; Chen, L. Dual-Arm Robot Trajectory Planning Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning under Complex Environment. Micromachines 2022, 13, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Cai, Z.; Peng, H.; Wu, Z. Coordinated Control Based on Reinforcement Learning for Dual-Arm Continuum Manipulators in Space Capture Missions. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2021, 34, 04021087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Wang, Q.; Tan, J. A Novel Robotic Grasping Method for Moving Objects Based on Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Cong, L.; Hendrich, N.; Li, S.; Sun, F.; Zhang, J. Multifingered Grasping Based on Multimodal Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Luo, B.; Yang, C.; Huang, T. MO-MIX: Multi-Objective Multi-Agent Cooperative Decision-Making with Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 12098–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficuciello, F.; Migliozzi, A.; Zaccara, D.; Villani, L.; Siciliano, B. Vision-based Grasp Learning of an Anthropomorphic Hand-arm System in a Synergy-based Control Framework. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaao4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Layer | Actor Network | Activation | Critic Network | Activation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input layer | 22 | Relu | 22 | Relu |

| Hidden laye r1 | 256 | Relu | 256 | Relu |

| Hidden layer 2 | 128 | Relu | 128 | Relu |

| Hidden layer 3 | 64 | Relu | 64 | Relu |

| Output layer | 6 | Tanh | 6 | Tanh |

| Hyper-Parameter | Value | Hyper-Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Episodes_limit | 600 | Replay buffer size | 2 × 104 |

| Step_limit | 256 | Exploration noise | 0.5–0.2 |

| Learning rate | 5 × 10−4 | Tau | 0.0005 |

| Batch size | 256 | Beta_start | 0.4 |

| Discount factor | 0.99 | Beta_frames | 1 × 105 |

| epsilon | 1 × 10−6 | alpha | 0.4 |

| The Value of Gaussian Noise | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control mode | Single arm | Dual arm | Single arm | Dual arm | Single arm | Dual arm |

| Success rate | 85.12% | 95.17% | 82.84% | 93.42% | 80.18% | 90.14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, R.; Liu, M.; Du, J.; Bao, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, J. Research on a Cooperative Grasping Method for Heterogeneous Objects in Unstructured Scenarios of Mine Conveyor Belts Based on an Improved MATD3. Sensors 2025, 25, 6824. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226824

Gao R, Liu M, Du J, Bao Y, Wu X, Liu J. Research on a Cooperative Grasping Method for Heterogeneous Objects in Unstructured Scenarios of Mine Conveyor Belts Based on an Improved MATD3. Sensors. 2025; 25(22):6824. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226824

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Rui, Mengcong Liu, Jingyi Du, Yifan Bao, Xudong Wu, and Jiahui Liu. 2025. "Research on a Cooperative Grasping Method for Heterogeneous Objects in Unstructured Scenarios of Mine Conveyor Belts Based on an Improved MATD3" Sensors 25, no. 22: 6824. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226824

APA StyleGao, R., Liu, M., Du, J., Bao, Y., Wu, X., & Liu, J. (2025). Research on a Cooperative Grasping Method for Heterogeneous Objects in Unstructured Scenarios of Mine Conveyor Belts Based on an Improved MATD3. Sensors, 25(22), 6824. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25226824