Enhanced Reaction Time Measurement System Based on 3D Accelerometer in Athletics

Highlights

- A portable system for measuring reaction time at athletic starts was designed and developed using an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU).

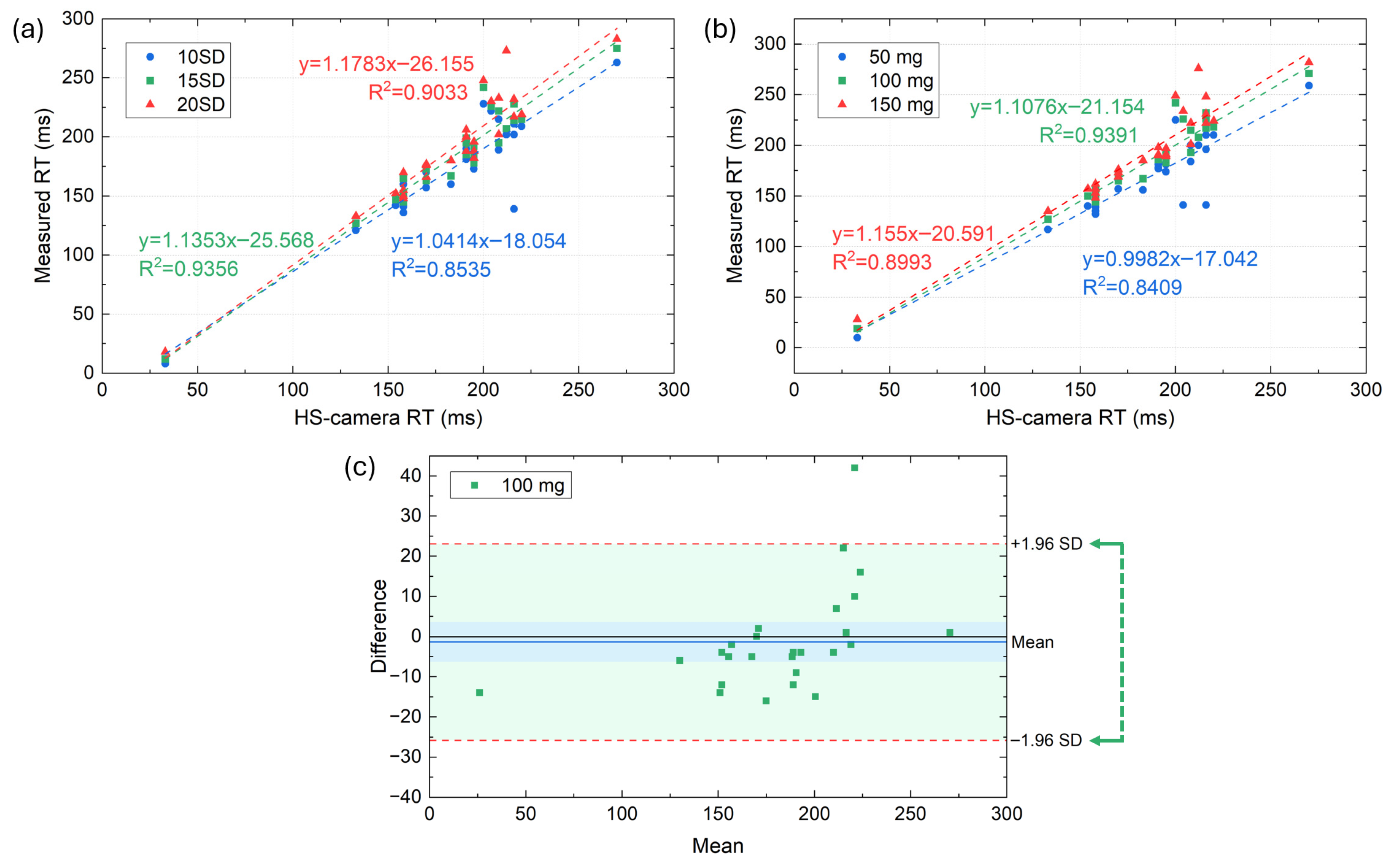

- Validation tests demonstrated good agreement with the high-speed camera, used as the gold-standard reference system.

- The proposed portable, low-cost system provides reliable reaction time measurements in athletics, offering valuable support for athletes and coaches.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i.

- To design and implement an IMU-based system for measuring reaction time in athletics.

- ii.

- To determine athletes’ reaction times to an auditory stimulus during a sprint start, using both a high-speed camera and the proposed IMU system.

- iii.

- To compare the reaction time results obtained from the high-speed camera with those from the IMU system.

2. System Description

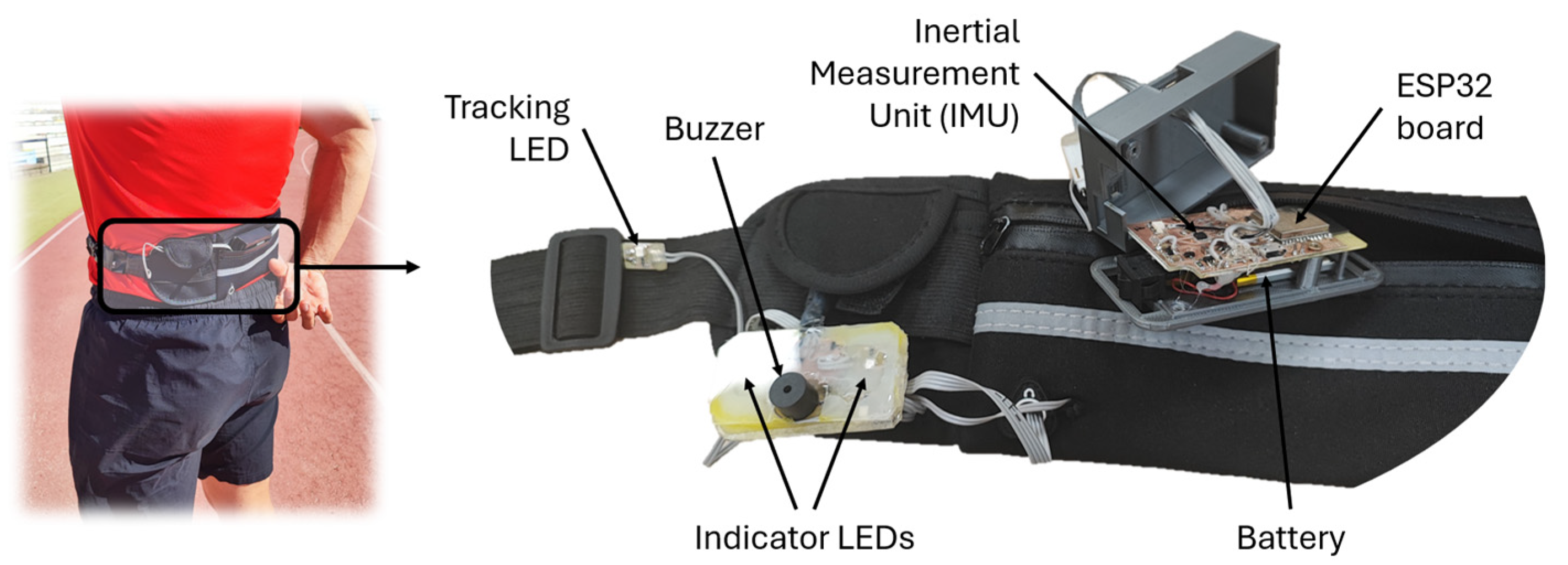

2.1. Hardware Development

- Custom PCB design: An ad hoc PCB was designed and fabricated using an LPKF ProtoMat S100 milling machine (LPKF Laser & Electronics, Garbsen, Germany), integrating all system components (ICM20948 IMU, ESP32 module, power management system, etc.) into a single compact layout. This eliminated the need for commercial development boards and external Bluetooth modules, significantly reducing both size and weight.

- Custom 3D-printed enclosure: A custom PLA case was designed and fabricated using a 3D printer Creality 3D CR-X (Shenzhen Creality 3D Technology Co, Ltd., Shenzhen, China) to precisely fit the custom PCB, replacing the standard commercial enclosure used previously. The device features a compact, wearable, battery-powered design (80 × 40 × 20 mm, 42 g). A 450 mAh battery was selected to maintain the compact form factor constrained by electronic board dimensions while ensuring adequate operational autonomy.

- Upgraded IMU sensor: The new design comprises a 9-degree-of-freedom IMU model ICM20948 (TDK InvenSense, San José, CA, USA), which integrates a three-axis 16-bit accelerometer, with acceleration range from ±2 g to ±16 g and a maximum sample rate of 4.5 kHz, and a three-axis 16-bit gyroscope with a range of ±250 to ±2000 degrees per second (dps). It also incorporates a three-axis 16-bit magnetometer AK09916 (AKM Semiconductor, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) with a range of ±4912 µT. This IMU is an upgraded version of the MPU-9250 9DoF used in the earlier prototype, offering improved performance and lower power consumption. The IMU also integrates a Digital Motion Processor (DMP), which processes the raw sensor data through filtering and sensor fusion to obtain rotation quaternions, later converted into Euler angles (yaw, pitch, and roll). However, even under optimal conditions, the DMP can achieve a maximum frequency of 225 Hz, which is insufficient for high-speed (HS) dynamic measurements [32]. In this work, only the accelerometer data are used, achieving a sampling frequency of 1 kHz for the three acceleration components.

- Enhanced processing capabilities: To enable higher processing power and a more compact implementation, a 32-bit ESP32-WROOM-32E-N16 microcontroller (Espressif Systems Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was employed. This MCU features a maximum clock frequency of 240 MHz, 520 kB of RAM, and 16 MB of internal flash memory (3 MB allocated for program storage) and wireless communication capabilities (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth Classic and Bluetooth Low Energy) within a single chip, enabling on-board data processing while significantly reducing both complexity and physical size of the electronic board. In practice, the microcontroller manages the Bluetooth connection with the smartphone or PC, processes the acquired sensor data, and triggers the auditory stimulus. It also stores both raw sensor data and computed results on the on-board microSD (µSD) card. In the previous design, the SAMD21G18A microcontroller operated at a maximum clock frequency of 96 MHz, with 32 kB of RAM and 256 kB of program memory. This upgrade provides greater real-time computing capability without compromising measurement timing and allows the storage of large data vectors in RAM. Consequently, the new design supports a high sampling frequency of 1 kHz, previously limited to 200 Hz in the earlier prototype.

- Buzzer and LEDs: To generate the auditive stimulus, a custom-designed external electronic board was equipped with a centrally mounted buzzer and two LEDs situated on each side of the buzzer (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). These indicator LEDs are used to trigger a 240-fps HS camera at the onset of the buzzer sound, allowing comparison of reaction times measured by both systems, with the HS camera serving as the gold standard. In addition, a third fixed LED (the tracking LED) was included to track the movement with the HS camera, enabling precise detection of the subject’s motion. More details about the experimental setup are given in Section 3.

- Reduced power consumption: Power consumption was experimentally measured using a DC Power Analyzer (N6705A, Keysight Tech., Santa Clara, CA, USA) setting the output voltage at 3.7 V to simulate the supply of the lithium battery. When the device was connected via Bluetooth to the smartphone and the tracking LED was on, but without taking measurements, the current consumption was 54 mA, corresponding to a battery life of 8.3 h. In full-speed measurement mode, the current consumption increased to 117 mA, reducing the battery life to 3.84 h. Since the system operates in full-speed measurement mode only during the sprint tests, the battery capacity is sufficient to support measurement sessions in study participants or during personal use.

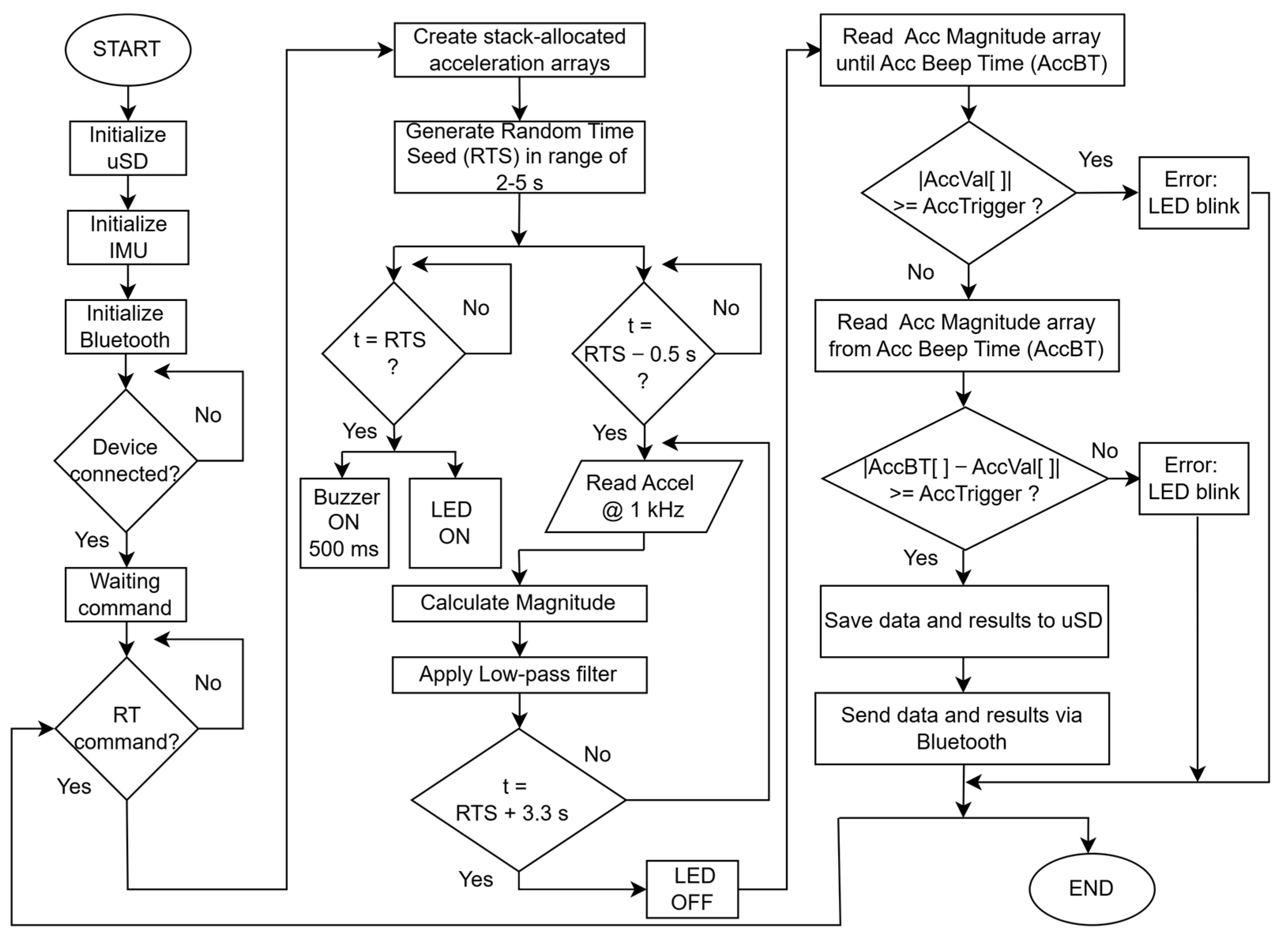

2.2. Firmware Description

- Upon system initialization, the tracking LED turns on, the Bluetooth device is paired, and the system enters a waiting state for the start command.

- Stack-allocated acceleration arrays are created, reserving space in the processor’s RAM (Random Access Memory) for high-frequency data recording. This memory is released once the main function execution is completed. A random time seed is also generated.

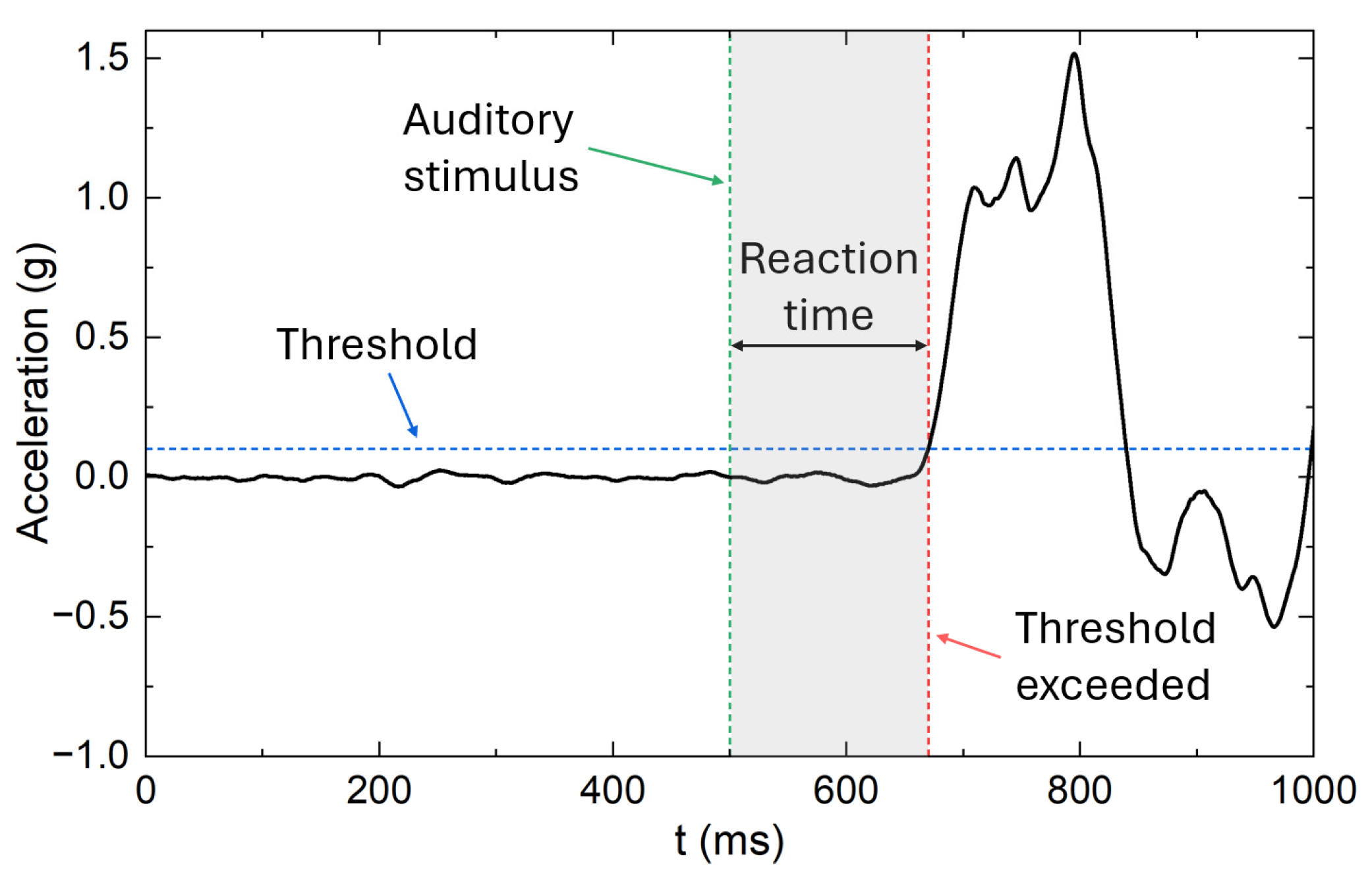

- 0.5 s before the random time, high-frequency recording (1 kHz) of the three acceleration components begins, while the acceleration magnitude is simultaneously calculated and stored in a separate array.

- When the random time is reached, the system turns on the indicator LEDs and triggers the buzzer for 500 ms to provide the auditory cue.

- 3.3 s after the random time, the system stops recording, turns off the indicator LEDs, and begins post-processing the data, ensuring that all measurements fit within the allocated acceleration arrays.

- The acceleration magnitude array is processed. If the acceleration exceeds the desired trigger before the buzzer sounds, or if the acceleration does not reach the trigger after the buzzer, an error is indicated by blinking the indicator LEDs. In such cases, the data are neither saved to the µSD card nor transmitted via Bluetooth.

- If the data are valid, both the raw data and the processed results are saved to the µSD card and transmitted via Bluetooth to the user’s smartphone.

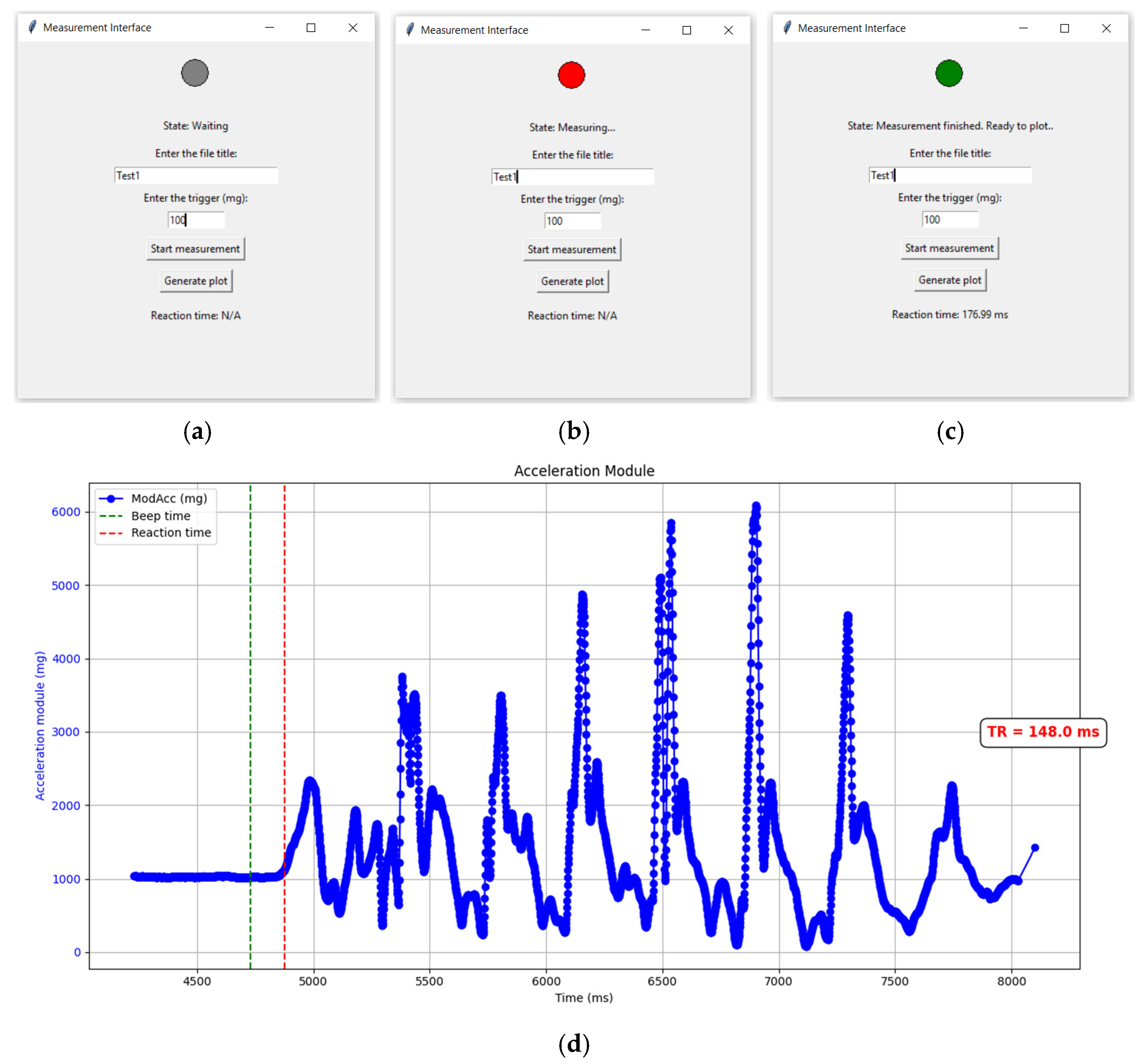

2.3. Desktop Application

2.4. Smartphone Application

3. Experimental Setup and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RT | Reaction Time |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| BT | Bluetooth |

References

- Whelan, R. Effective Analysis of Reaction Time Data. Psychol. Rec. 2017, 58, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, B.; Shiraishi, M.; Soangra, R. Reliability and Validity of Inertial Sensor Assisted Reaction Time Measurement Tools among Healthy Young Adults. Sensors 2022, 22, 8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lettink, A.; Altenburg, T.M.; Arts, J.; van Hees, V.T.; Chinapaw, M.J.M. Systematic Review of Accelerometer-Based Methods for 24-h Physical Behavior Assessment in Young Children (0–5 Years Old). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2022, 19, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazit, E.; Buchman, A.S.; Dawe, R.; Curran, T.A.; Mirelman, A.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M. What Happens before the First Step? A New Approach to Quantifying Gait Initiation Using a Wearable Sensor. Gait Posture 2020, 76, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, B.; Shiraishi, M.; Soangra, R. A Portable and Reliable Tool for On-Site Physical Reaction Time (RT) Measurement. Invent. Discl. 2023, 3, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, M.; Valk, H.; Eaton, J.; Kovaly, S.; Karnes, S.; Vu, T.; Stevenson, K.; Kowalczyk, M.; Gormley, W. On-Body Measure of Reaction Time Correlates with Intoxication Level. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Libero, T.; Carissimo, C.; Cerro, G.; Fattorini, L.; Ferrigno, L.; Rodio, A. Workers’ Motor Efficiency Assessment through an IMU-Based Standardized Test and an Automated and Error-Minimizing Measurement Procedure. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2023 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC/I&CPS Europe), Madrid, Spain, 6–9 June 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cinaz, B.; Vogt, C.; Arnrich, B.; Tröster, G. Implementation and Evaluation of Wearable Reaction Time Tests. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2012, 8, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philpott, L.K.; Weaver, S.; Gordon, D.; Conway, P.P.; West, A.A. Assessing Wireless Inertia Measurement Units for Monitoring Athletics Sprint Performance. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE SENSORS, Valencia, Spain, 2–5 November 2014; pp. 2199–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Carissimo, C.; Cerro, G.; Libero, T.D.; Ferrigno, L.; Marino, A.; Rodio, A. Objective Evaluation of Coordinative Abilities and Training Effectiveness in Sports Scenarios: An Automated Measurement Protocol. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 76996–77008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Lieres und Wilkau, H.C.; Irwin, G.; Bezodis, N.E.; Simpson, S.; Bezodis, I.N. Phase Analysis in Maximal Sprinting: An Investigation of Step-to-Step Technical Changes between the Initial Acceleration, Transition and Maximal Velocity Phases. Sports Biomech. 2020, 19, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.P.; Ryan, L.J.; Meng, C.R.; Stearne, D.J. Evaluation of Maximum Thigh Angular Acceleration during the Swing Phase of Steady-Speed Running. Sports Biomech. 2024, 23, 1963–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucarno, S.; Zago, M.; Buckthorpe, M.; Grassi, A.; Tosarelli, F.; Smith, R.; Della Villa, F. Systematic Video Analysis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Professional Female Soccer Players. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, S.; Mahdaviani, K.; Thaler, A.; Kording, K.; Cook, D.J.; Blohm, G.; Troje, N.F. MoVi: A Large Multi-Purpose Human Motion and Video Dataset. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peebles, A.T.; Carroll, M.M.; Socha, J.J.; Schmitt, D.; Queen, R.M. Validity of Using Automated Two-Dimensional Video Analysis to Measure Continuous Sagittal Plane Running Kinematics. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Nava, I.H.; Munoz-Melendez, A. Wearable Inertial Sensors for Human Motion Analysis: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2016, 16, 7821–7834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborri, J.; Keogh, J.; Kos, A.; Santuz, A.; Umek, A.; Urbanczyk, C.; Van Der Kruk, E.; Rossi, S. Sport Biomechanics Applications Using Inertial, Force, and EMG Sensors: A Literature Overview. Appl. Bionics Biomech. 2020, 2020, 2041549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Kesbi, R.; Memarzadeh-Tehran, H.; Deen, M.J. Technique to Estimate Human Reaction Time Based on Visual Perception. Healthc. Tech. Lett. 2017, 4, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, K.; Attal, F.; Mohammed, S.; Khalil, M.; Amirat, Y. Physical Activity Recognition Using Inertial Wearable Sensors—A Review of Supervised Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Advances in Biomedical Engineering (ICABME), Beirut, Lebanon, 16–18 September 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, K.; Smith, S.L.; Sands, W.A. Validation of an Accelerometer for Measuring Sport Performance. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.G.; Zhu, Z.W.; Shen, F. The Study of Wireless Measurement System for Neuro-Motor Reaction Time. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 472–475, 2850–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurchiek, R.D.; Rupasinghe Arachchige Don, H.S.; Pelawa Watagoda, L.C.R.; McGinnis, R.S.; Van Werkhoven, H.; Needle, A.R.; McBride, J.M.; Arnholt, A.T. Sprint Assessment Using Machine Learning and a Wearable Accelerometer. J. Appl. Biomech. 2019, 35, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, T.; Grazioso, S.; Panariello, D.; Di Gironimo, G.; Lanzotti, A. A Wearable Inertial Device Based on Biomechanical Parameters for Sports Performance Analysis in Race-Walking: Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 II Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 and IoT (MetroInd4.0&IoT), Naples, Italy, 4–6 June 2019; IEEE: Naples, Italy, 2019; pp. 259–262. [Google Scholar]

- Kianifar, R.; Joukov, V.; Lee, A.; Raina, S.; Kulić, D. Inertial Measurement Unit-Based Pose Estimation: Analyzing and Reducing Sensitivity to Sensor Placement and Body Measures. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 2019, 6, 2055668318813455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.L.; Neiva, H.P.; Pires, I.M.; Marinho, D.A.; Marques, M.C. Accelerometer Data from the Performance of Sit-to-Stand Test by Elderly People. Data Brief 2020, 33, 106328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, A.; Price, M.; Jenkins, D. Predicting Temporal Gait Kinematics from Running Velocity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2021, 35, 2379–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, P.Y.M.; Ng, G.Y.F. Comparison between an Accelerometer and a Three-Dimensional Motion Analysis System for the Detection of Movement. Physiotherapy 2012, 98, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, I.M.; Marques, D.; Pombo, N.; Garcia, N.M.; Marques, M.C.; Flórez-Revuelta, F. Measurement of the Reaction Time in the 30-S Chair Stand Test Using the Accelerometer Sensor Available in off-the-Shelf Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and e-Health, Funchal, Portugal, 22–23 March 2018; SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2018; pp. 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Stenum, J.; Rossi, C.; Roemmich, R.T. Two-Dimensional Video-Based Analysis of Human Gait Using Pose Estimation. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polechonski, J.; Langer, A.; Stastny, P.; Zak, M.; Zajac-Gawlak, I.; Maszczyk, A. Does Virtual Reality Allow for a Reliable Assessment of Reaction Speed in Mixed Martial Arts Athletes? Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2024, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Hannan Bin Azhar, M.A.; Greace, A. Optimal Locations and Computational Frameworks of FSR and IMU Sensors for Measuring Gait Abnormalities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Zhang, L.; Cai, S.; Du, M.; Liu, T.; Li, Q.; Shull, P. Influence of Sampling Rate on Wearable IMU Orientation Estimation Accuracy for Human Movement Analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Pérez, J.A.; Ruiz-García, I.; Navarro-Marchal, I.; López-Ruiz, N.; Gómez-López, P.J.; Palma, A.J.; Carvajal, M.A. System Based on an Inertial Measurement Unit for Accurate Flight Time Determination in Vertical Jumps. Sensors 2023, 23, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Olmedo, J.M.; Penichet-Tomás, A.; Villalón-Gasch, L.; Pueo, B. Validity and Reliability of Smartphone High-Speed Camera and Kinovea for Velocity-Based Training Measurement. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 16, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Fernández, C.; Tejero-González, C.M.; Del Campo-Vecino, J.; Bavaresco, N. The Concurrent Validity and Reliability of a Low-Cost, High-Speed Camera-Based Method for Measuring the Flight Time of Vertical Jumps. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2014, 28, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milloz, M.; Hayes, K.; Harrison, A.J. Sprint Start Regulation in Athletics: A Critical Review. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pousibet-Garrido, A.; Moreno-Pérez, J.A.; Escobedo, P.; Caraballo, I.; Gutiérrez-Manzanedo, J.V.; González-Montesinos, J.L.; Carvajal, M.A. Enhanced Reaction Time Measurement System Based on 3D Accelerometer in Athletics. Sensors 2025, 25, 6730. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216730

Pousibet-Garrido A, Moreno-Pérez JA, Escobedo P, Caraballo I, Gutiérrez-Manzanedo JV, González-Montesinos JL, Carvajal MA. Enhanced Reaction Time Measurement System Based on 3D Accelerometer in Athletics. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6730. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216730

Chicago/Turabian StylePousibet-Garrido, Antonio, Juan A. Moreno-Pérez, Pablo Escobedo, Israel Caraballo, José V. Gutiérrez-Manzanedo, José L. González-Montesinos, and Miguel A. Carvajal. 2025. "Enhanced Reaction Time Measurement System Based on 3D Accelerometer in Athletics" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6730. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216730

APA StylePousibet-Garrido, A., Moreno-Pérez, J. A., Escobedo, P., Caraballo, I., Gutiérrez-Manzanedo, J. V., González-Montesinos, J. L., & Carvajal, M. A. (2025). Enhanced Reaction Time Measurement System Based on 3D Accelerometer in Athletics. Sensors, 25(21), 6730. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216730