Breath Isoprene Sensor Based on Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

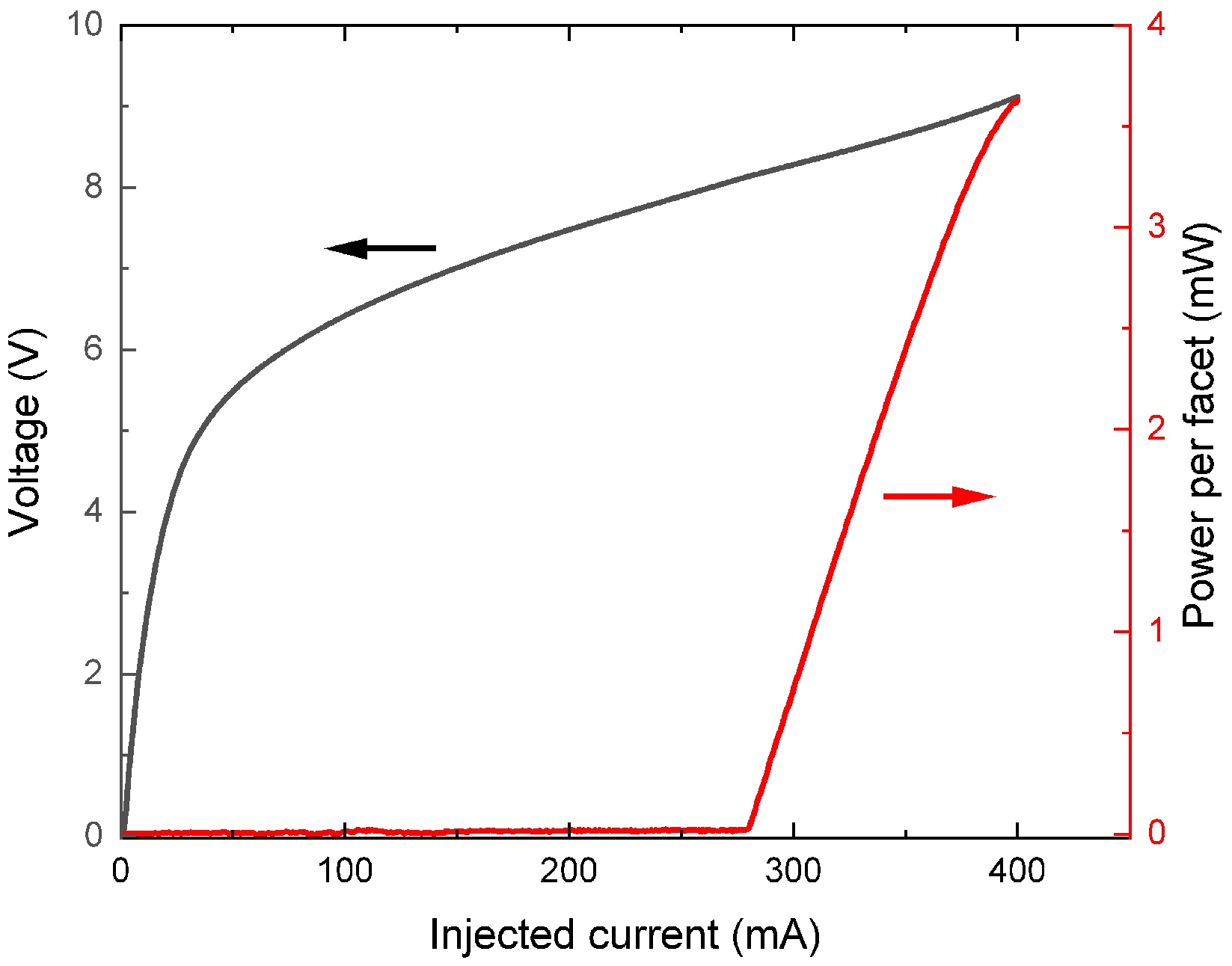

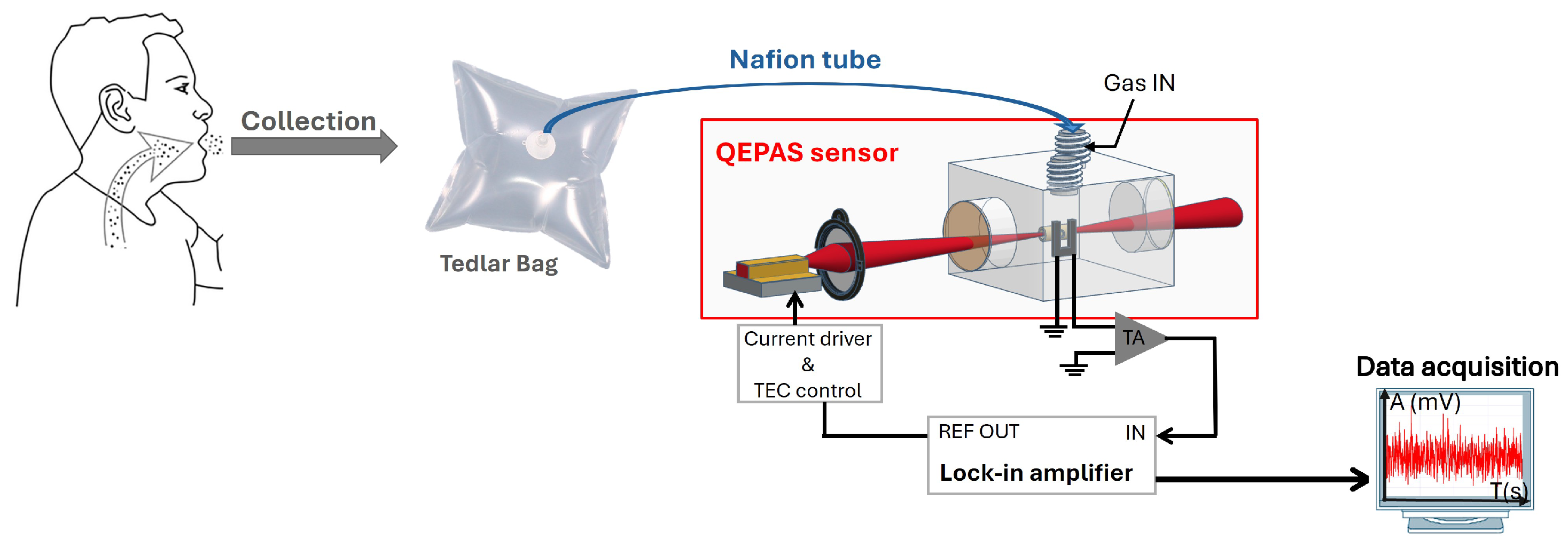

2. Experimental Setup

3. Spectral Simulations and Modulation Techniques

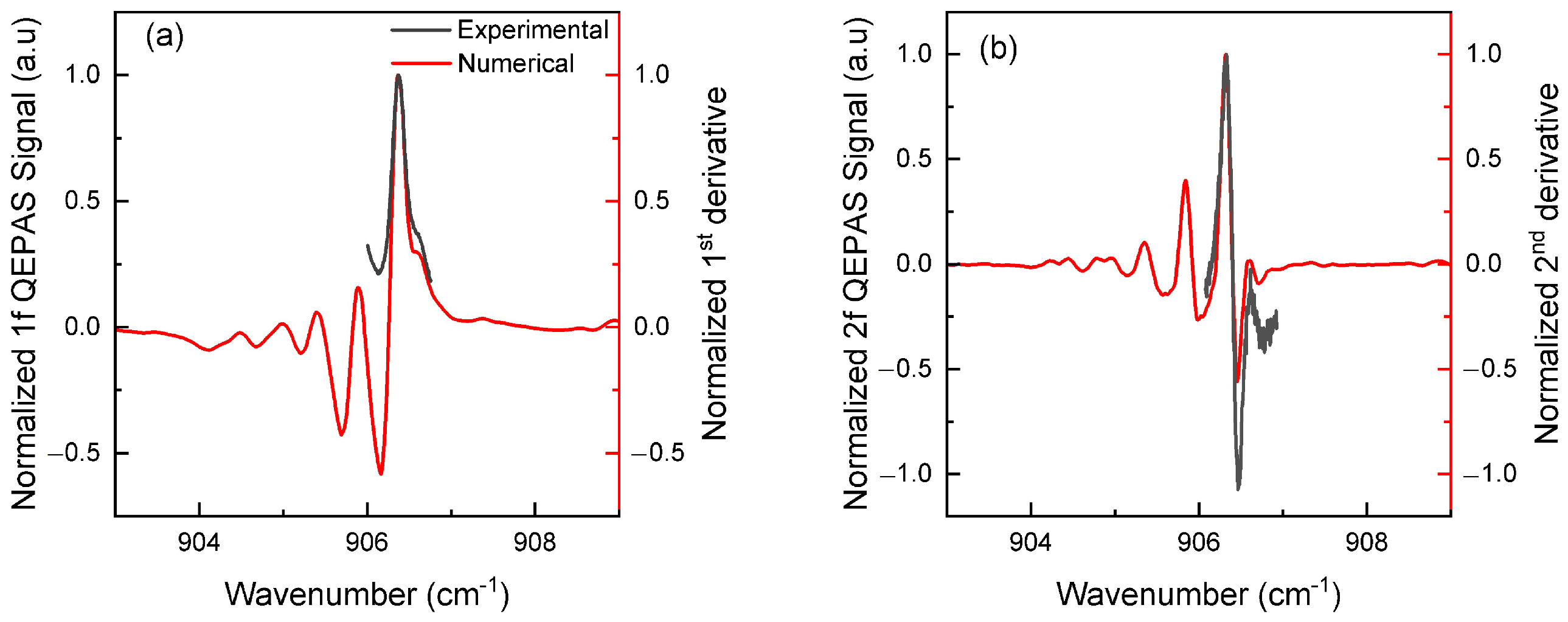

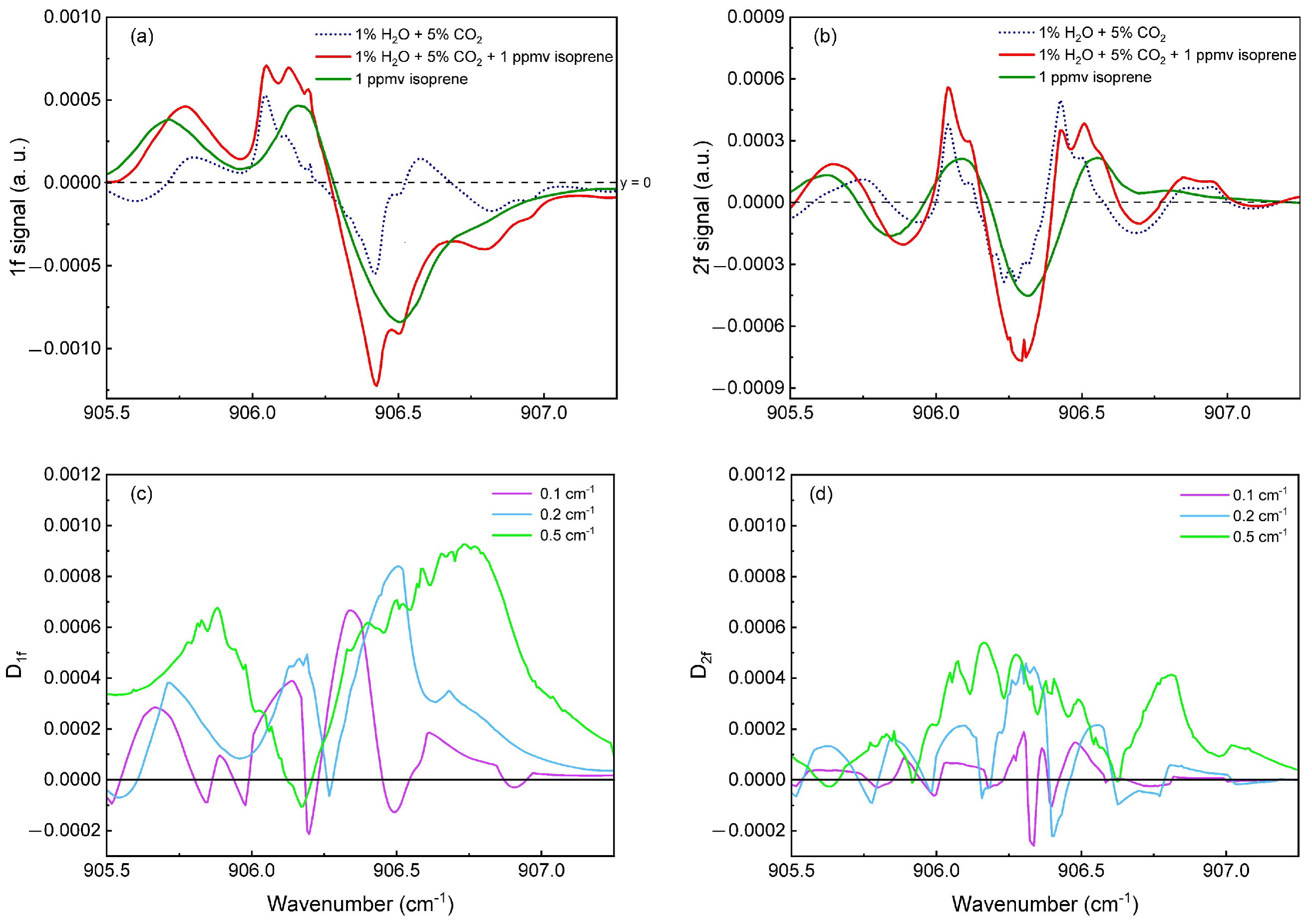

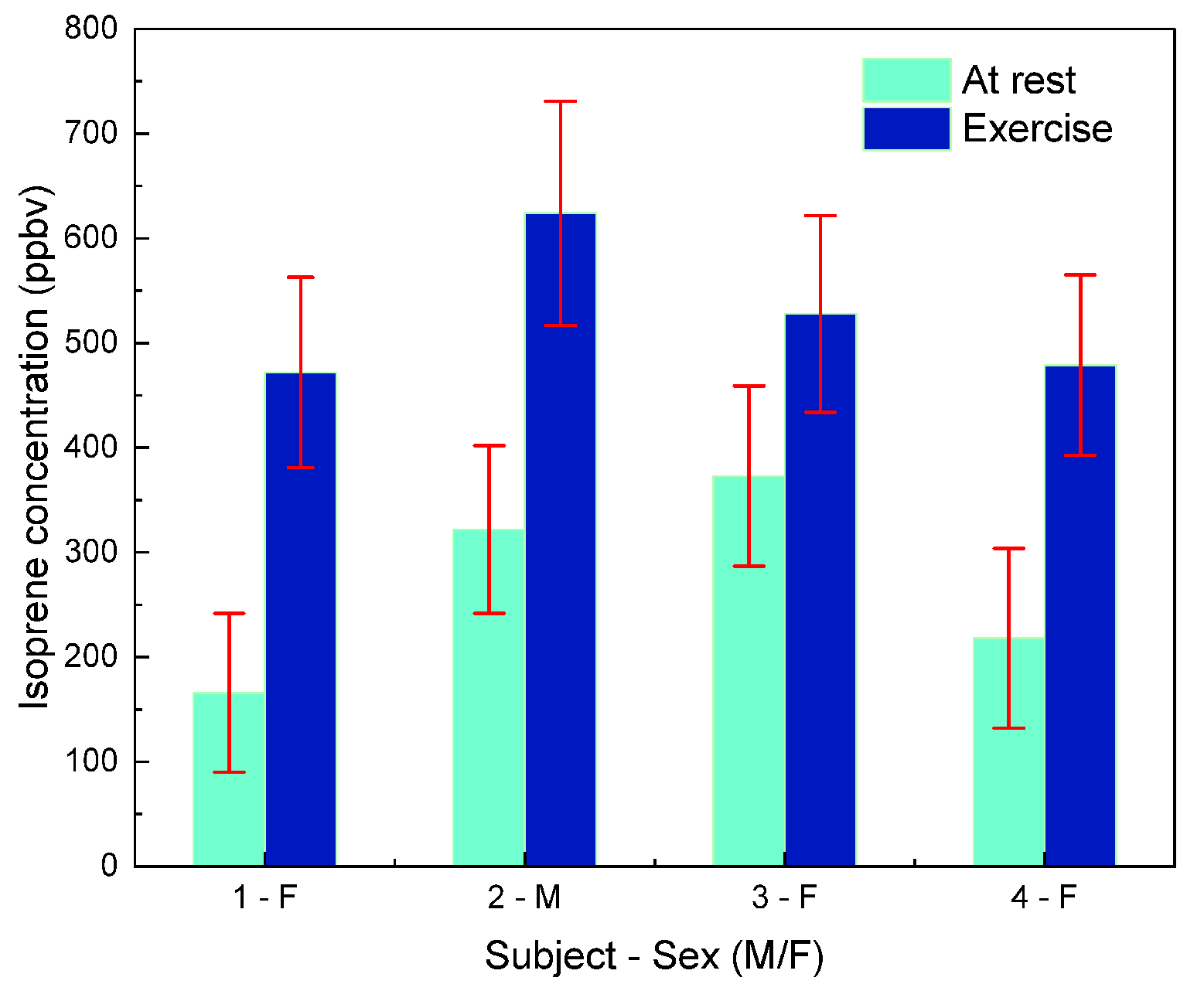

3.1. Spectral Simulations

3.2. Optimization and Experimental Conditions

3.3. Isoprene in Breath: Numerical Interpretations

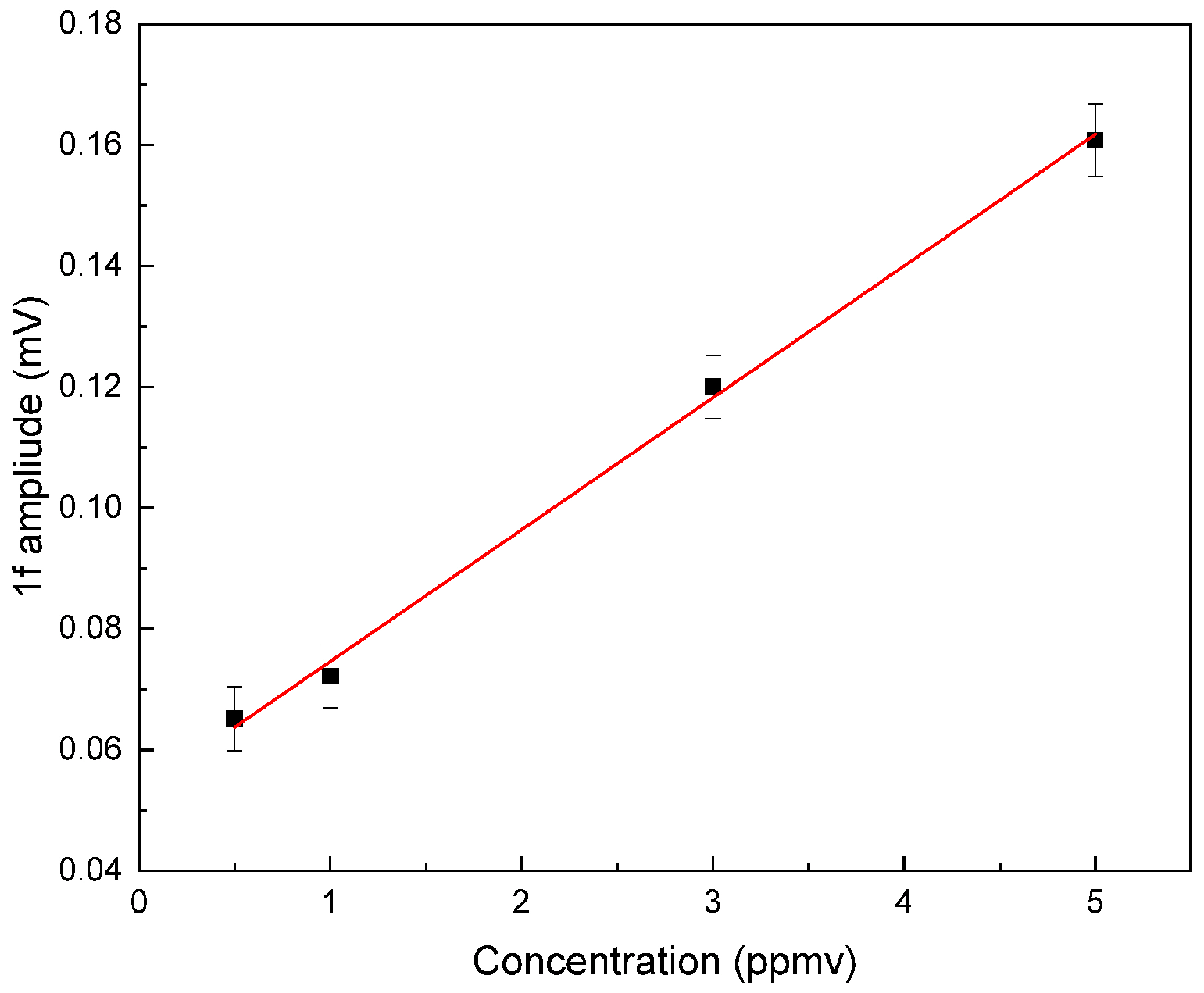

4. Sensor Calibration

5. Breath Measurements

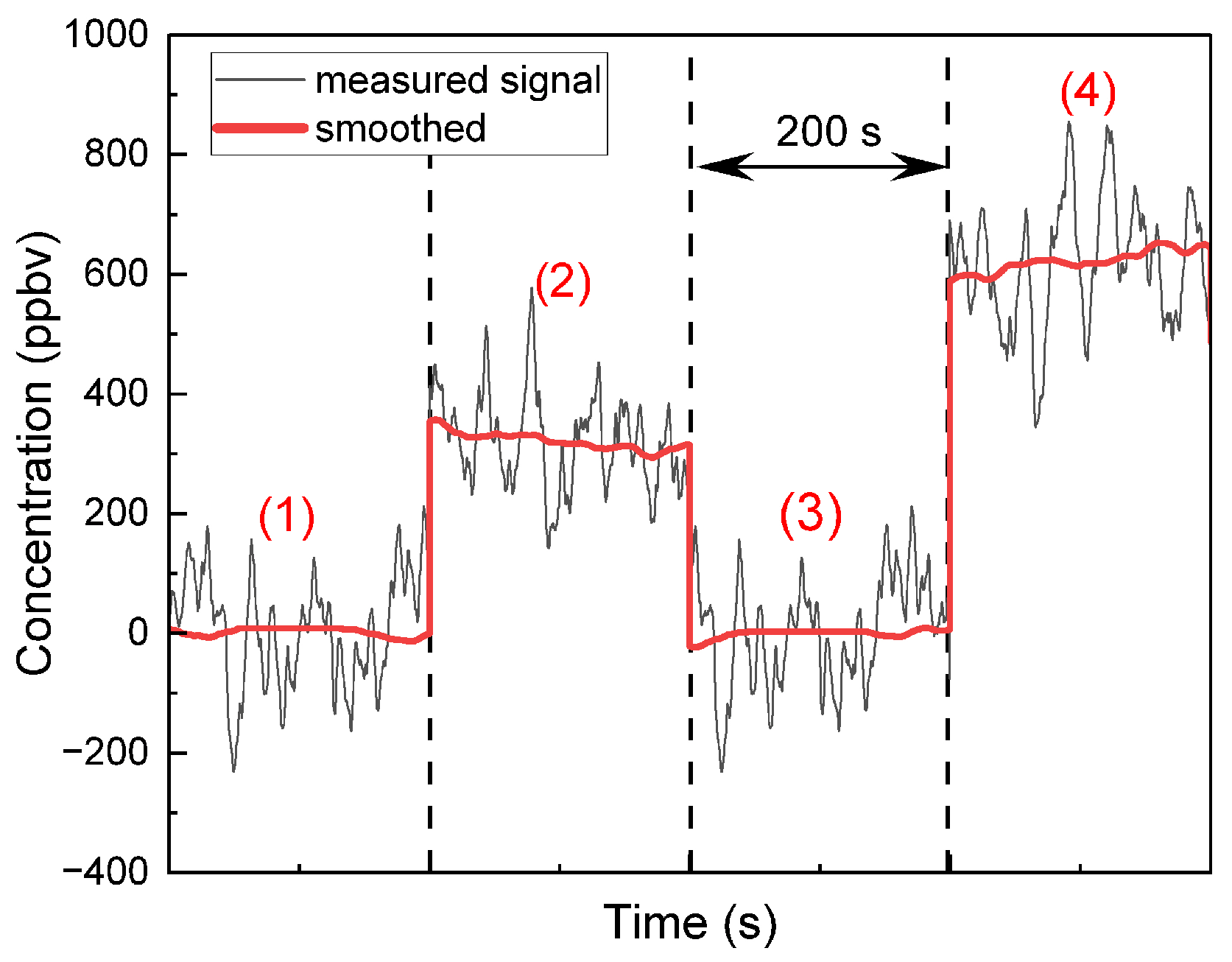

- Phase 1—Nitrogen flush.

- Phase 2—Resting breath sample: After the volunteer remained seated and relaxed for several minutes to stabilize metabolic activity and allow the exhaled isoprene concentration to reach a steady state, a breath sample was collected in a Tedlar bag at atmospheric pressure and analyzed using the QEPAS setup.

- Phase 3—Nitrogen flush: This was performed to eliminate any residual gases from previous measurements.

- Phase 4—Exercise breath sample: A second breath sample was collected one minute after moderate physical activity (cycling on a stationary bicycle).

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Williams, C.G.H. On isoprene and caoutchine. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1860, 150, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, A.R.C.; Dworakowska, S.; Reis, A.; Gouveia, L.; Matos, C.T.; Bogdał, D.; Bogel-Łukasik, R. Chemical and biological-based isoprene production: Green metrics. Catal. Today 2015, 239, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.A. Worker and Community Right to Know: Basis and Background with Environmental Hazardous Substance List, Glossary, References; New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, Office of Science and Research: Trenton, NJ, USA, 1984; 300+p. [CrossRef]

- Seco, R.; Holst, T.; Davie-Martin, C.L.; Simin, T.; Guenther, A.; Pirk, N.; Rinne, J.; Rinnan, R. Strong isoprene emission response to temperature in tundra vegetation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118014119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Koc, H.; Unterkofler, K.; Mochalski, P.; Kupferthaler, A.; Teschl, G.; Teschl, S.; Hinterhuber, H.; Amann, A. Physiological modeling of isoprene dynamics in exhaled breath. J. Theor. Biol. 2010, 267, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukul, P.; Richter, A.; Junghanss, C.; Schubert, J.K.; Miekisch, W. Origin of breath isoprene in humans is revealed via multi-omic investigations. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendis, S.; Sobotka, P.A.; Euler, D.E. Pentane and isoprene in expired air from humans: Gas-chromatographic analysis of single breath. Clin. Chem. 1994, 40, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Broek, J.; Mochalski, P.; Königstein, K.; Ting, W.C.; Unterkofler, K.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A.; Mayhew, C.A.; Güntner, A.T.; Pratsinis, S.E. Selective monitoring of breath isoprene by a portable detector during exercise and at rest. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 357, 131444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.; Kupferthaler, A.; Unterkofler, K.; Koc, H.; Teschl, S.; Teschl, G.; Miekisch, W.; Schubert, J.; Hinterhuber, H.; Amann, A. Isoprene and acetone concentration profiles during exercise on an ergometer. J. Breath Res. 2009, 3, 027006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendis, S.; Sobotka, P.A.; Euler, D.E. Expired Hydrocarbons in Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Free Radic. Res. 1995, 23, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mametov, R.; Ratiu, I.-A.; Monedeiro, F.; Ligor, T.; Buszewski, B. Evolution and evaluation of GC columns. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 51, 150–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, I.; Domingo, G.; Bracale, M.; Loreto, F.; Pollastri, S. Isoprene emission influences the proteomic profile of Arabidopsis plants under well-watered and drought-stress conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, B.O.; Larsson, B.T. Analysis of organic compounds in human breath by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1969, 74, 961–966. [Google Scholar]

- Gashimova, E.; Osipova, A.; Temerdashev, A.; Porkhanov, V.; Polyakov, I.; Perunov, D.; Dmitrieva, E. Exhaled breath analysis using GC-MS and an electronic nose for lung cancer diagnostics. Anal. Methods 2021, 13, 4793–4804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, E.; Woollam, M.; Vashistha, S.; Agarwal, M. Quantifying exhaled acetone and isoprene through solid phase microextraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1301, 342468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, C.; Španél, P.; Smith, D. A longitudinal study of breath isoprene in healthy volunteers using selected ion flow tube mass spectrometry (SIFT-MS). Physiol. Meas. 2006, 27, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, J.; Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, M. An exploratory study on online quantification of isoprene in human breath using cavity ringdown spectroscopy in the ultraviolet. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1131, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.T.; Beloin, J.; Fournier, M.; Kovic, G. Sensitive infrared spectroscopy of isoprene at the part per billion level using a quantum cascade laser spectrometer. Appl. Phys. B 2020, 126, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhnemann, F.; Wolfertz, M.; Arnold, S.; Lagemann, M.; Popp, A.; Schuler, G.; Jux, A.; Boland, W. Simultaneous online detection of isoprene and isoprene-d2 using infrared photoacoustic spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. B 2002, 75, 397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Pangerl, J.; Sukul, P.; Rück, T.; Escher, L.; Miekisch, W.; Bierl, R.; Matysik, F.-M. Photoacoustic trace-analysis of breath isoprene and acetone via interband- and Quantum Cascade Lasers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 424, 136886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, R.; Loghmari, Z.; Bahriz, M.; Chamassi, K.; Teissier, R.; Baranov, A.N.; Vicet, A. Off-beam QEPAS sensor using an 11-μm DFB-QCL with an optimized acoustic resonator. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 7435–7446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loghmari, Z.; Bahriz, M.; Thomas, D.D.; Meguekam, A.; Van, H.N.; Teissier, R.; Baranov, A.N. Room temperature continuous wave operation of InAs/AlSb-based quantum cascade laser at λ∼11μm. Electron. Lett. 2018, 54, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayache, D.; Trzpil, W.; Rousseau, R.; Kinjalk, K.; Teissier, R.; Baranov, A.N.; Bahriz, M.; Vicet, A. Benzene sensing by quartz enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy at 14.85 μm. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 5531–5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, I.E.; Rothman, L.S.; Hill, C.; Kochanov, R.V.; Tan, Y.; Bernath, P.F.; Birk, M.; Boudon, V.; Campargue, A.; Chance, K.V. The HITRAN2016 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 203, 3–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagler, J.; Krauss, B. Capnography: A valuable tool for airway management. Emerg. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2008, 26, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, T.; Sukul, P.; Davis, C.E.; Di Francesco, F.; Miekisch, W. Breath analysis for health monitoring and clinical applications. In Respiratory Physiology: New Knowledge, Better Diagnosis; European Respiratory Society: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 154–171. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, R. Analytical Line Shapes for Lorentzian Signals Broadened by Modulation. J. Appl. Phys. 1965, 36, 2522–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petra, N.; Zweck, J.; Kosterev, A.A.; Minkoff, S.E.; Thomazy, D. Theoretical analysis of a quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy sensor. Appl. Phys. B 2009, 94, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzpil, W.; Maurin, N.; Rousseau, R.; Ayache, D.; Vicet, A.; Bahriz, M. Analytic optimization of cantilevers for photoacoustic gas sensor with capacitive transduction. Sensors 2021, 21, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilt, S.; Th’evenaz, L.; Robert, P. Wavelength modulation spectroscopy: Combined frequency and intensity laser modulation. Appl. Opt. 2003, 42, 6728–6738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilt, S. Mesure de Traces de gaz à l’Aide de Lasers à Semi-Conducteur. Ph.D. Thesis, EPFL, Lausanne, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, D.W. Statistics of atomic frequency standards. Proc. IEEE 1966, 54, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurin, N.; Rousseau, R.; Trzpil, W.; Aoust, G.; Hayot, M.; Mercier, J.; Bahriz, M.; Gouzi, F.; Vicet, A. First clinical evaluation of a quartz enhanced photo-acoustic CO sensor for human breath analysis. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 319, 128247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abou Naoum, F.; Ayache, D.; Seoudi, T.; Diaz-Thomas, D.A.; Baranov, A.; Pages, F.; Charensol, J.; Rosenkrantz, E.; Aouadi, M.; Bahriz, M.; et al. Breath Isoprene Sensor Based on Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Sensors 2025, 25, 6732. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216732

Abou Naoum F, Ayache D, Seoudi T, Diaz-Thomas DA, Baranov A, Pages F, Charensol J, Rosenkrantz E, Aouadi M, Bahriz M, et al. Breath Isoprene Sensor Based on Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Sensors. 2025; 25(21):6732. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216732

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbou Naoum, Fadia, Diba Ayache, Tarek Seoudi, Daniel Andres Diaz-Thomas, Alexei Baranov, Fanny Pages, Julien Charensol, Eric Rosenkrantz, Meryem Aouadi, Michael Bahriz, and et al. 2025. "Breath Isoprene Sensor Based on Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy" Sensors 25, no. 21: 6732. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216732

APA StyleAbou Naoum, F., Ayache, D., Seoudi, T., Diaz-Thomas, D. A., Baranov, A., Pages, F., Charensol, J., Rosenkrantz, E., Aouadi, M., Bahriz, M., Gouzi, F., & Vicet, A. (2025). Breath Isoprene Sensor Based on Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Sensors, 25(21), 6732. https://doi.org/10.3390/s25216732