Abstract

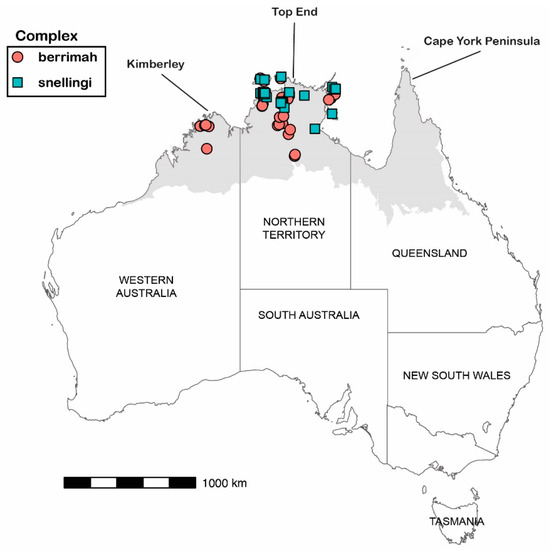

We integrate morphological variation, CO1 distance and clustering, and geographic distribution to document unrecognized diversity within Meranoplus ‘berrimah’ and M. ‘snellingi’, members of the M. diversus group of specialist seed harvesters from Australia’s monsoonal (seasonal) tropics. This follows similar analyses of two other monsoonal ‘species’ of the group, M. ajax and M. unicolor, showing that both represent highly diverse complexes comprising an estimated 100 species each. We recognize eleven species among the 34 sequenced specimens attributable to M. berrimah and ten species among the 29 sequenced specimens attributable to M. snellingi. Images of all these species are provided. The M. berrimah complex has a far broader geographic range than was apparent when M. berrimah was originally described, occurring in the Kimberley region of Western Australia in addition to the Top End of the Northern Territory, whereas the M. snellingi complex appears to be restricted to the Top End. The limited geographic representation of our sequenced specimens suggests that many additional species occur in both complexes. We estimate that the M. snellingi complex contains 15–20 species in total, and that this number is considerably higher in the M. berrimah complex because of its broader distributional range. Our study provides further evidence that monsoonal Australia is a global centre of ant diversity, but it is not formally recognized as such because the great majority of its species is undescribed.

1. Introduction

The Meranoplus diversus F. Smith group of specialist seed harvesters [1] is one of many ant taxa occurring in Australia’s 2 million km2 monsoonal (seasonal) tropics whose hyperdiversity is unrecognized because the great majority of its species is undescribed. Through integrated morphological, genetic (CO1) and geographical analysis we have shown that two described ‘species’ from the M. diversus group, M. ajax Forel and M. unicolor Forel, each represent hyperdiverse complexes that include more than 50 species occurring in monsoonal Australia [2,3]. Similar and even higher levels of undescribed hyperdiversity within the Australian monsoonal ant fauna have been documented in Melophorus, Monomorium and Tetramorium [4].

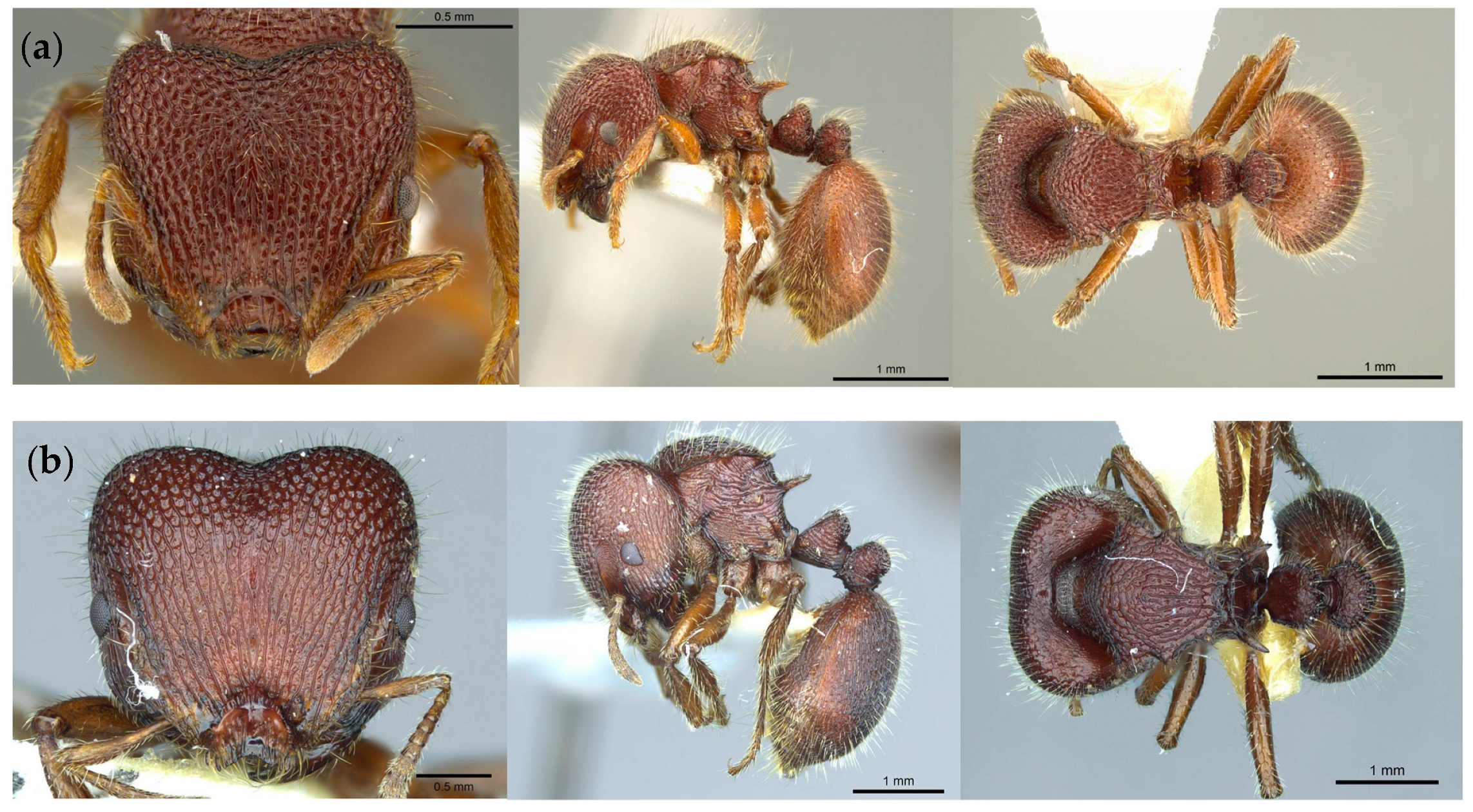

In this paper, we document extensive undescribed diversity in two more monsoonal taxa within the M. diversus group that are formally recognized as single species, M. berrimah Schödl and M. snellingi Schödl. As in M. ajax and M. unicolor, both M. berrimah and M. snellingi belong to the dominant sub-group in northern Australia in which the posterolateral projections of the promesonotal shield are short and stout [1,5]. Meranoplus berrimah (Figure 1a) is the smallest species (head width ≤ 1.80 mm) within this subgroup, and its clypeus has a dorsal plate that variously projects beyond its anterior margin, with the plate typically having a concave anterior margin [1]. Meranoplus snellingi (Figure 1b) is considerably larger (head width up to 2.4 mm); its clypeus lacks a dorsal plate, and its anterior margin has a lamellate upward flexion [1]. The first gastral tergite of M. snellingi is coarsely striate, whereas it is micro-reticulate in M. berrimah (as in most other members of the M. diversus group).

Figure 1.

Head, lateral and dorsal images of type specimens of Meranoplus berrimah (a) and M. snellingi (b). Images from AntWeb. (a) Specimen CASTENT0919717; (b) Specimen CASTENT0919723.

The M. ajax and M. unicolor complexes both have very broad distributions, occurring throughout central and northern Australia [2,3]. In contrast, both M. berrimah and M. snellingi have restricted distributions—when described they were known only from the Top End (northern third, >1000 mean annual rainfall) of the Northern Territory (NT). The types of the two species are from the same site in suburban Darwin. Given their restricted distribution, their diversity would be expected to be far lower than in the M. ajax and M. unicolor complexes.

Here we provide an assessment of diversity within M. ‘berrimah’ and M. ‘snellingi’, based on integrated morphological, genetic (CO1) and geographical analysis. We show that they both represent diverse species complexes.

2. Materials and Methods

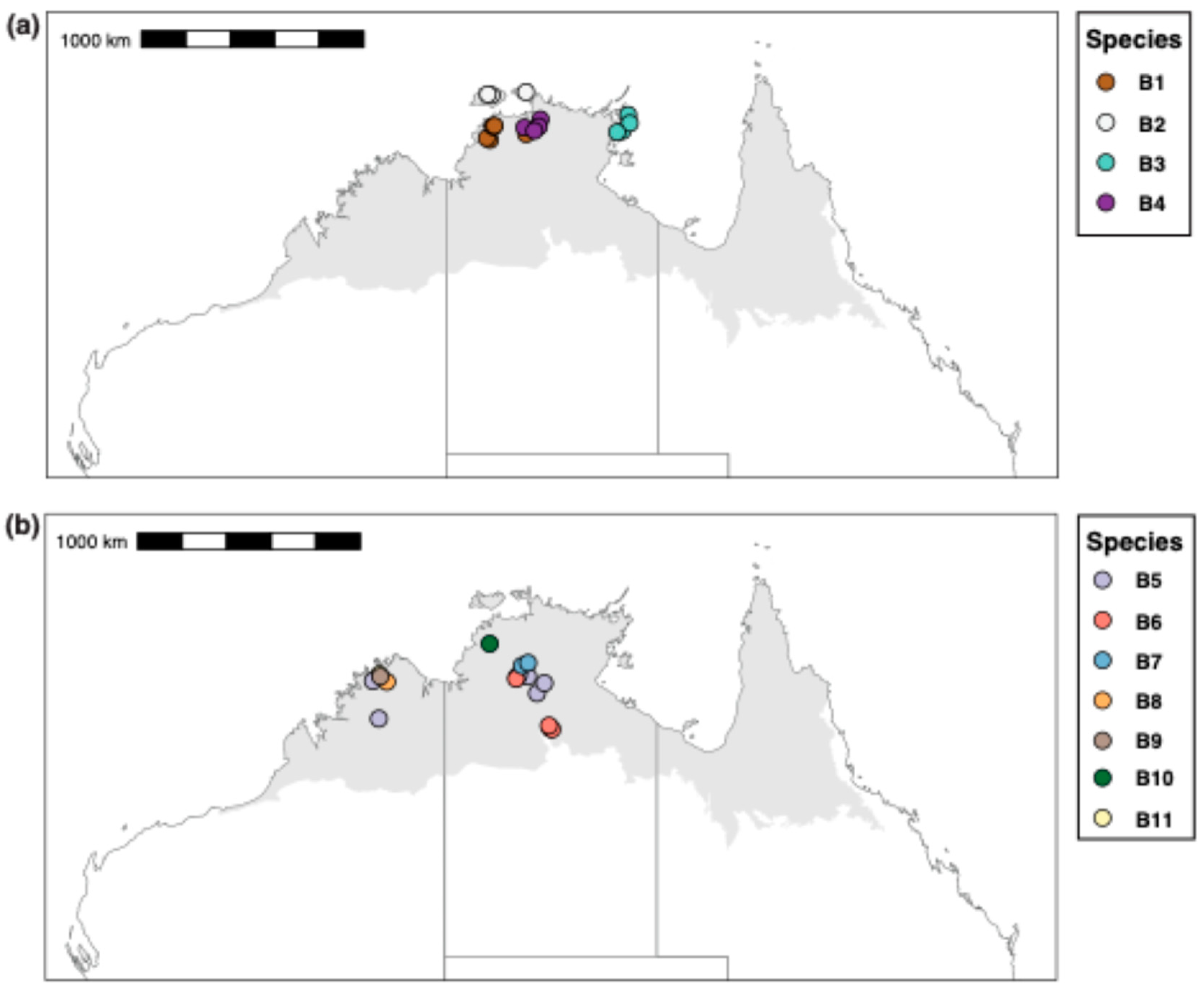

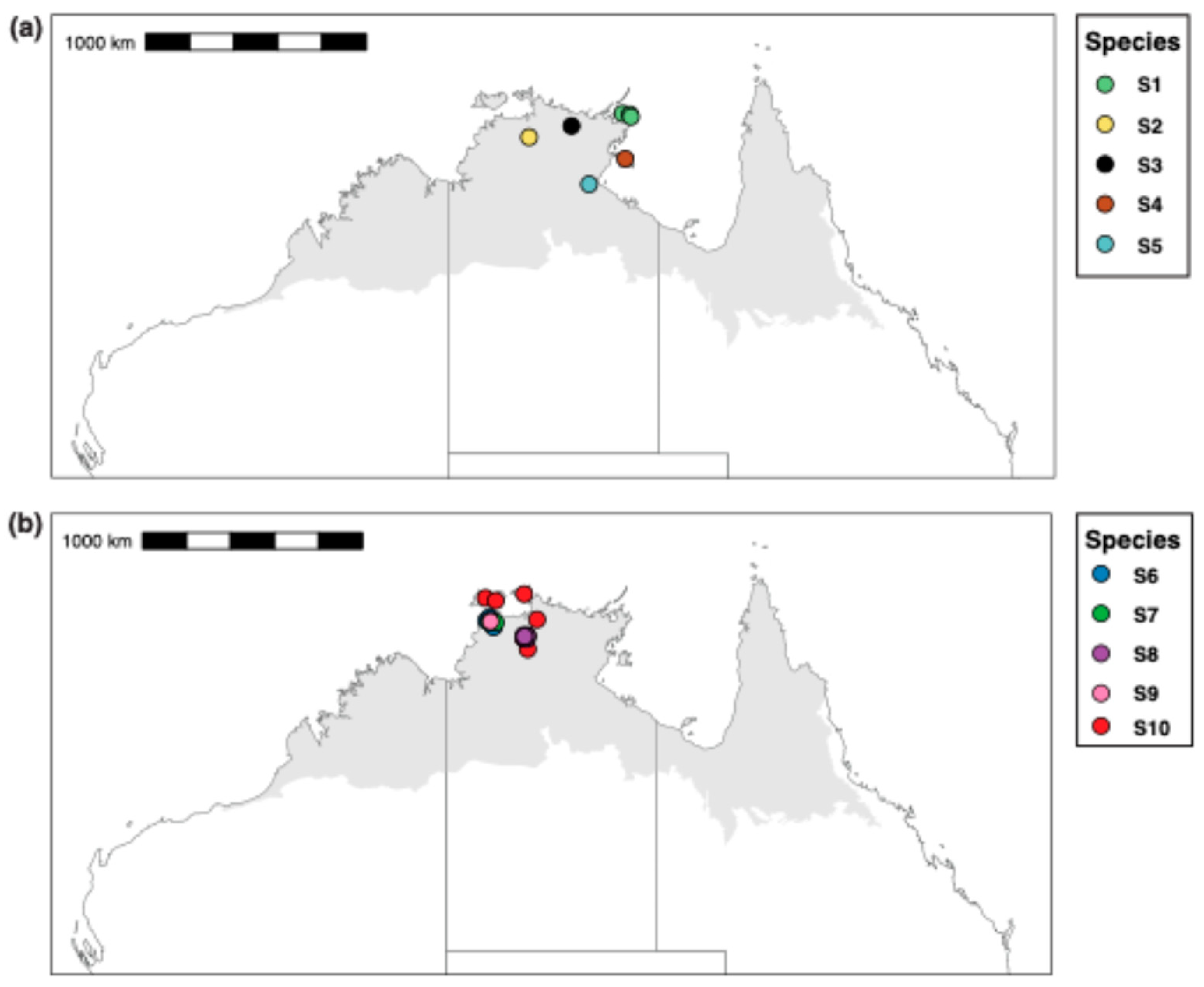

Our study is based on approximately 200 pinned specimens attributable to M. berrimah and 400 pinned specimens attributable to M. snellingi in the ant collection held at the Museum and Art Gallery of the NT (previously at the CSIRO laboratory) in Darwin, which represents most records of the taxa. We obtained CO1 sequences from 34 specimens attributable to M. berrimah and 29 specimens attributable to M. snellingi, collected from throughout their ranges as represented in the Darwin collection (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S1). Collections were made between 1986 and 2023. The Darwin collection contains no specimens from Queensland for either complex, and as far as we are aware none have ever been collected from there.

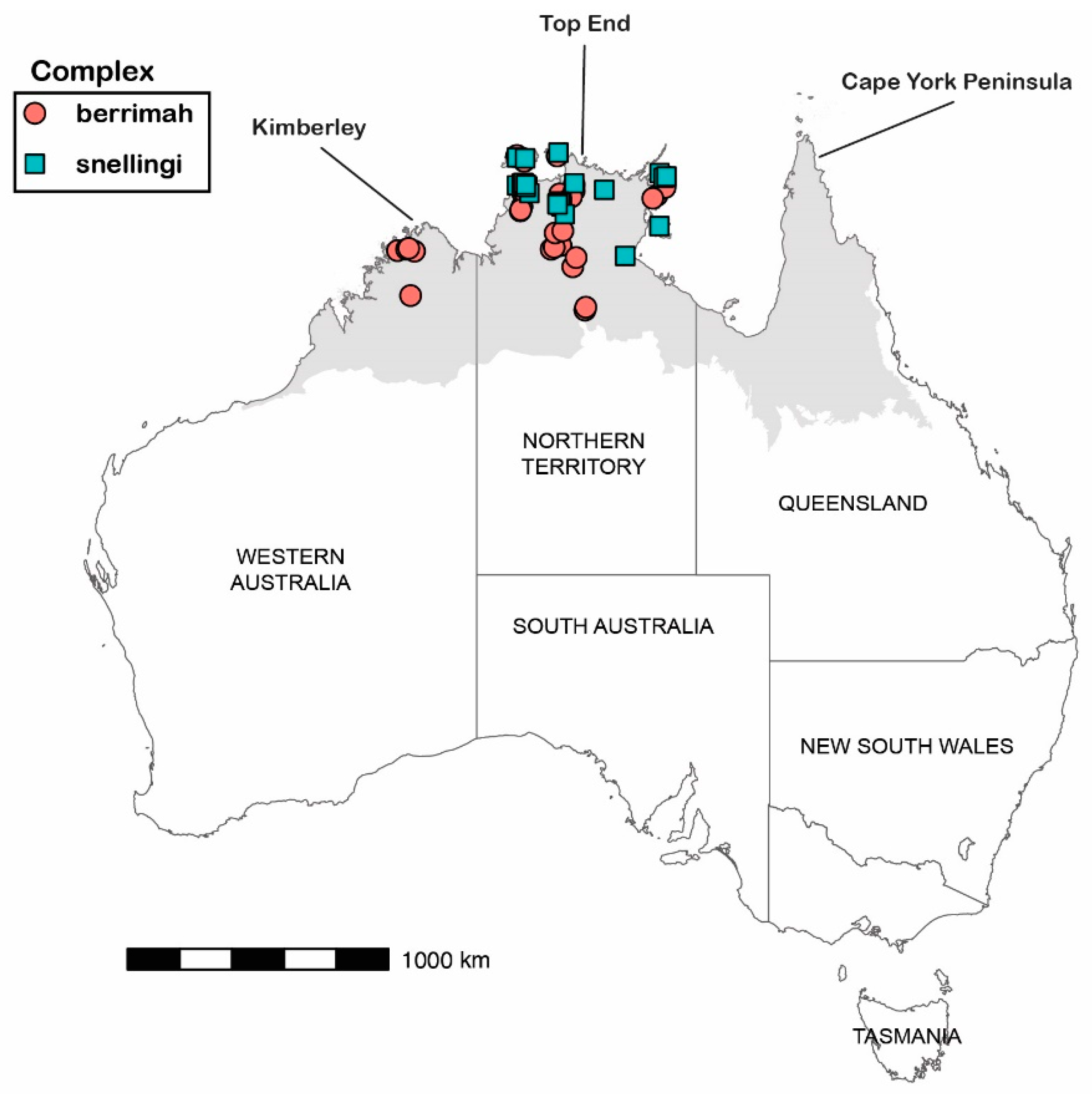

Figure 2.

Collection localities for sequenced specimens of Meranoplus ‘berrimah’ (circles) and M. ‘snellingi’ (squares). The shaded area represents Australia’s monsoonal zone, where rainfall is very heavily concentrated in a summer wet season. Total annual rainfall ranges from >15,000 mm on the far northern coasts to 500 mm on the southern boundary with the northern arid zone.

The Barcode of Life Data (BOLD) System was used for DNA extraction (from foreleg tissue; for extraction details, see http://ccdb.ca/resources; accessed on 4 November 2025) and CO1 sequencing. Sequenced specimens were assigned unique identification codes that combine the project name under which it was processed, its number within the project and the year of sequencing (e.g., BOLOZ1993–24). All specimens are labelled as such in the Darwin collection.

MEGA [6] (version 12.0.01) was used to check and edit DNA sequences, which were then aligned using the UPGMB clustering method in MUSCLE [7] and translated into (invertebrate) proteins to check for stop codons and nuclear paralogues. The aligned sequences resulted in 657 base pairs. A maximum likelihood tree was constructed in IQ-TREE v3 [8], using a BOLD sequence (MTROP172-23) from another monsoonal species from the Meranoplus diversus group, M. orientalis Schödl from Selma Station in Queensland (Qld), as the outgroup. The best-fit nucleotide substitution model was identified using the built-in ModelFinder (-m TEST), and node support was assessed using 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (-B 1000). Our final figure was produced in FigTree v1.4.4.

There is no particular CO1 distance that defines a species, but intraspecific CO1 distance is typically 1–3% for ants [9]. Our species delimitations were based on the integration of morphological variation, CO1 clustering and distance, and geographic distribution [10]. Our species concept was based on reproductive isolation and evolutionary independence as evidenced by morphological differentiation between sister CO1 clades and sympatric distribution.

We used a Leica DMC5400 camera (Wetzlar, Germany) mounted on a Leica M205C dissecting microscope to image a bar-coded specimen of each recognized species. Image montages were taken using the Leica Application suite v. 4.13 and stacked in Zerene stacker (Walnut Creek, CA, USA).

Finally, we used two statistical methods for species delimitation using CO1 data alone: the Poisson tree processes (PTP) model and the Bayesian implementation of the PTP model (bPTP). PTP infers species boundaries using the number of substitutions within and between species in a maximum likelihood tree [11], and bPTP adds Bayesian values to delimited species on the input tree [11]. We constructed a second maximum likelihood tree in IQ-TREE for these analyses, after removing the outgroup. We used the web server (http://species.h-its.org/ptp/, accessed on 12 June 2025) for both the PTP and bPTP analyses using the settings of 500,000 MCMC generations, 100 thinning and 0.1 burn-in. In order to increase the rate of convergence for the MCMC chain, we increased the number of MCMC generations from 100,000 to 500,000.

3. Results

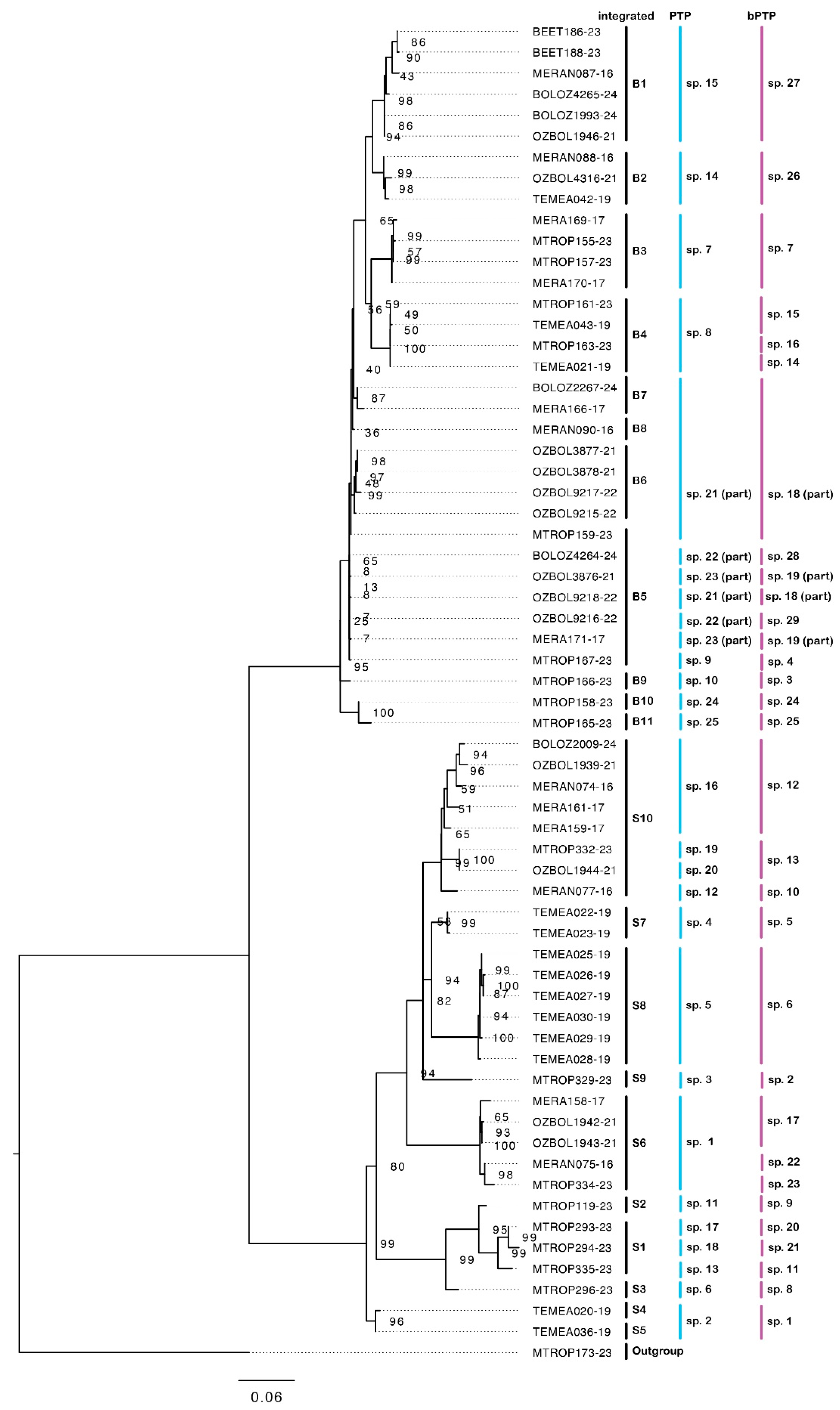

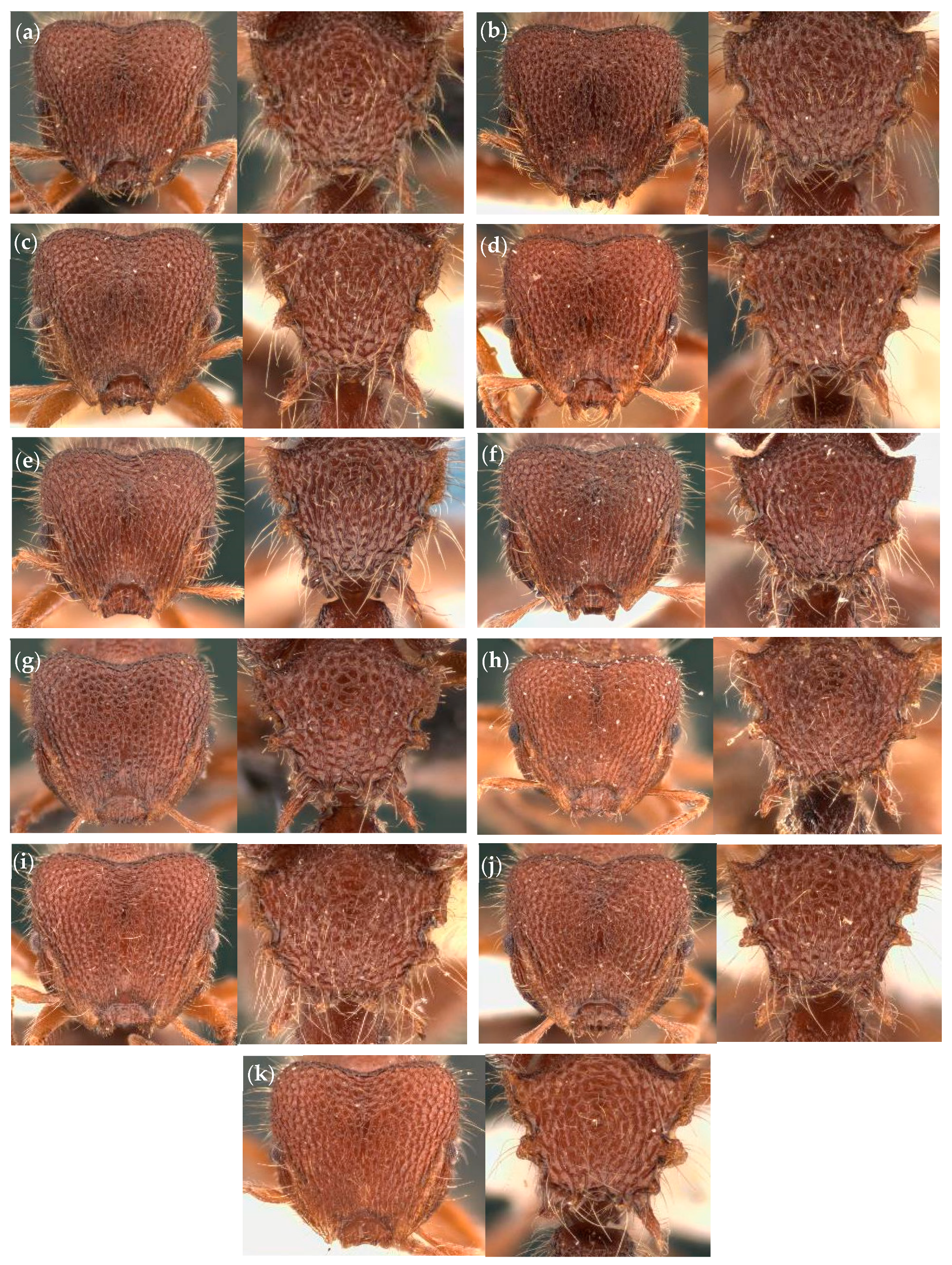

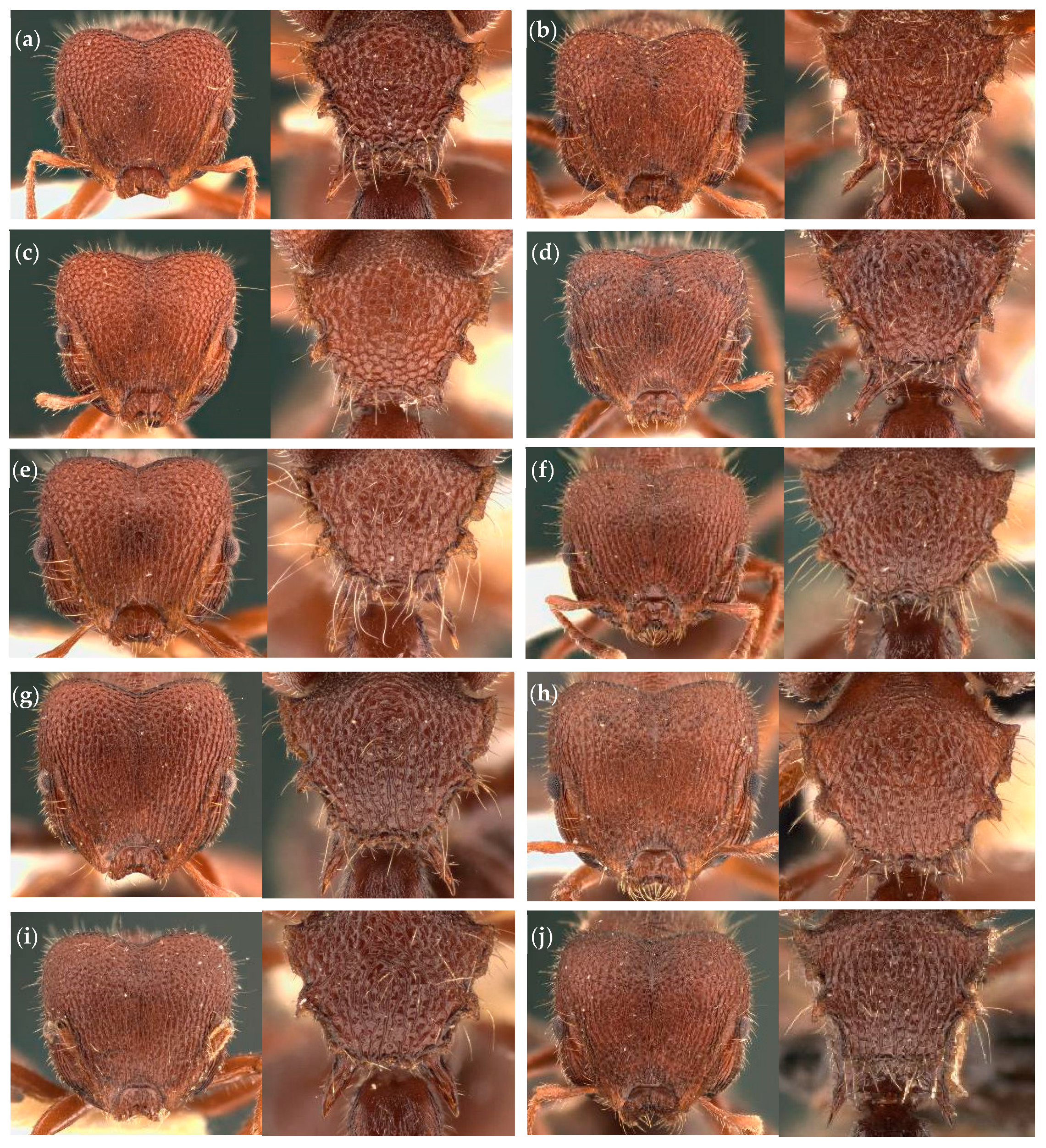

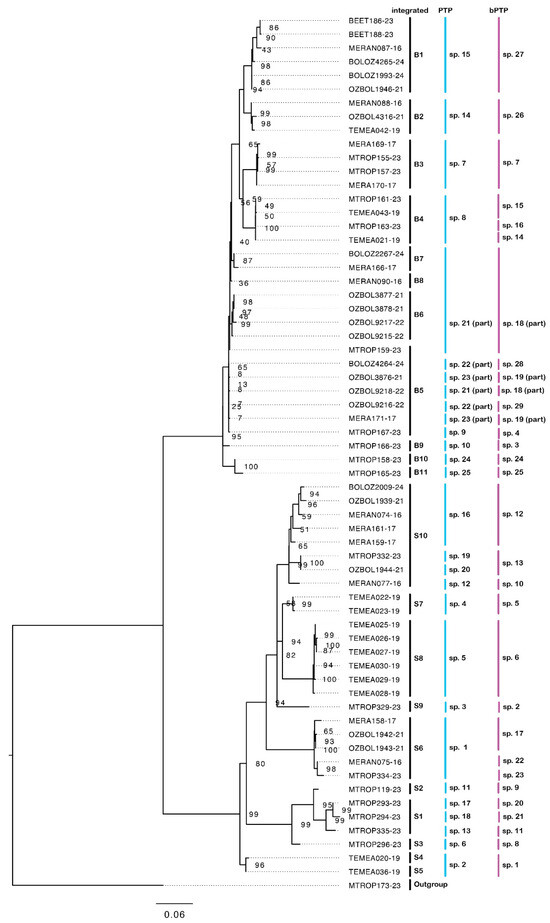

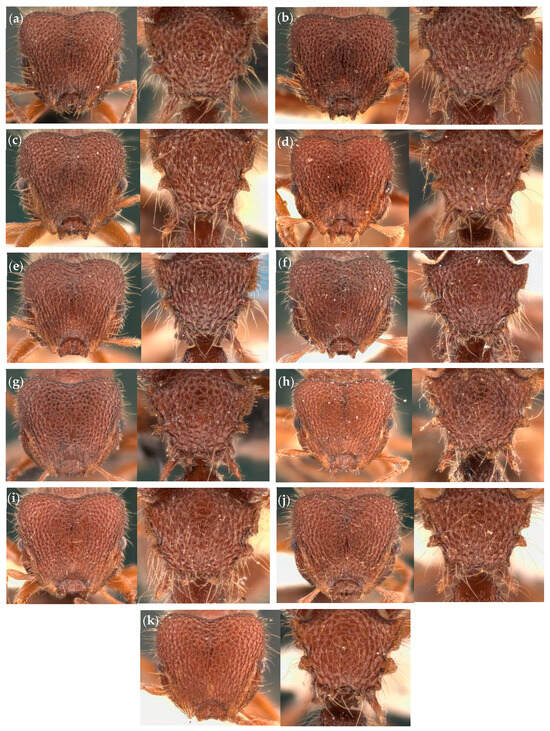

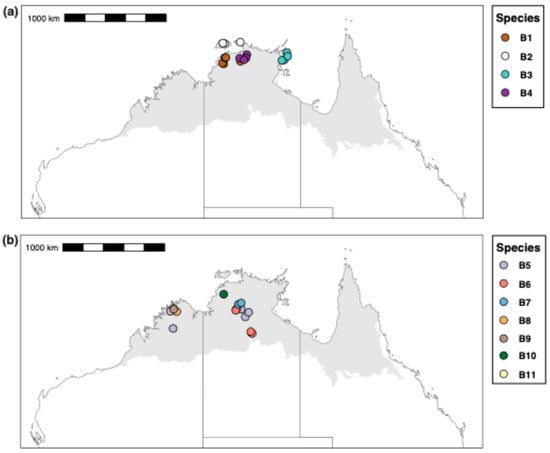

Our results show that sequenced specimens attributable to M. berrimah represent many species, and that this is also the case for species attributable to M. snellingi. Our integrated assessment recognizes eleven species (B1–11) among the 34 sequenced specimens in the M. berrimah complex and ten species (S1–10) among the 29 sequenced specimens in the M. snellingi complex (Figure 3). CO1 distance is substantially higher among species within the M. snellingi complex (up to >10%) than among those in the M. berrimah complex (up to ~6%). Species B1–4 are clearly differentiated from each other and from the other M. ‘berrimah’ species in the CO1 tree (Figure 3). In spp. B2–4, the clypeus has a conspicuously projecting dorsal plate (Figure 4b–d), but this is not the case in sp. B1 (Figure 4a). In sp. B2 the anterolateral angles of the dorsal shield are square, and in B3 nearly so, rather than acute as in all other species of the complex (Figure 4). In spp. B2 and B4 the posterior margin of the dorsal shield is conspicuously concave medially, compared with only weakly so in spp. B1 and B4 (Figure 4). Posterior head sculpture varies from foveolate (sp. B1; Figure 4a) to coarsely reticulate-rugose (sp. B3; Figure 4c). Three of the species have highly restricted distributions (Figure 5a): sp. B2 is known only from the Tiwi Islands north of Darwin and from north-western Arnhem Land, sp. B3 is known only from north-eastern Arnhem Land, and sp. B4 is known only from Kakadu National Park. Species B1 has been recorded from both the Berry Springs–Litchfield region south of Darwin and Kakadu National Park approximately 250 km to the east (Figure 5a).

Figure 3.

CO1 tree constructed by maximum likelihood. Showing the eleven recognized species attributable to M. berrimah (spp. B1–11) and the ten recognized species attributable to M. snellingi (spp. S1–10). Species recognized by PTP and bPTP analyses are also shown. Ultrafast bootstrap values are shown for node support.

Figure 4.

Species of the Meranplus berrimah complex. (a) sp. B1 (BOLD ID: BEET186-23); (b) sp. B2 (OZBOL4316-21); (c) sp. B3 (MTROP155-23); (d) sp. B4 (MTROP161-23); (e) sp. B5 (OZBOL3876-21); (f) sp. B6 (OZBOL3877-21); (g) sp. B7 (BOLOZ2267-24); (h) sp. B8 (MERAN090-16); (i) sp. B9 (MTROP166-23); (j) sp. B10 (MTROP158-23); (k) sp. B11 (MTROP165-23).

Figure 5.

Collection localities for sequenced specimens of the Meranplus berrimah complex. (a) spp. S1–4; (b) spp. S5–11.

Species B5–11 vary in clypeal structure and in the sculpture of the head and dorsal shield (Figure 4). Species B7 is particularly distinctive in that the head is coarsely reticulate-rugose throughout (Figure 4g). The dorsal clypeal plate is conspicuously projecting in sp. B6 (Figure 4f), slightly so in sp. B11 (Figure 4k) and not evidently so in the others. Notably, four of these species (spp. B5, B8, B9 and B11) occur in the northern Kimberley region of Western Australia (WA; Figure 5b). Species B9 and B11 have been recorded from the same site near the King Edward River crossing. In contrast to most other species of the M. berrimah complex, sp. B5 is rather widely distributed, occurring from the Katherine region of the NT to the Mitchell Plateau in the northern Kimberly (Figure 5), with very little (<0.5%) CO1 divergence across this range (Figure 3). Species B5 and B6 occur at the same site on Manbulloo Station in the NT (Supplementary Table S1). Species B6 extends substantially south of the Top End, to near the southern border of the monsoonal zone in the NT.

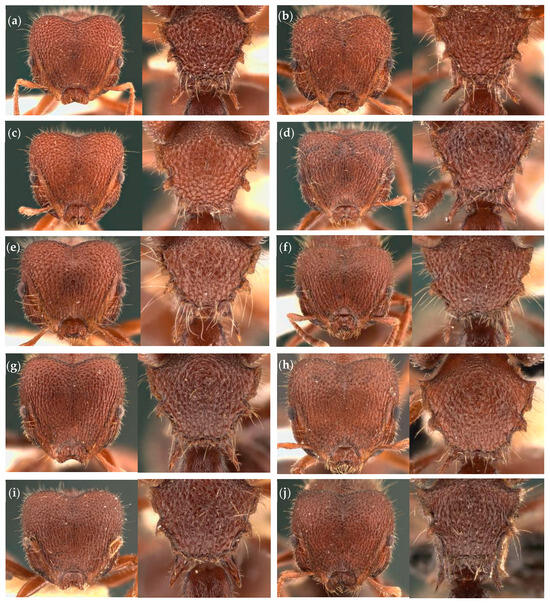

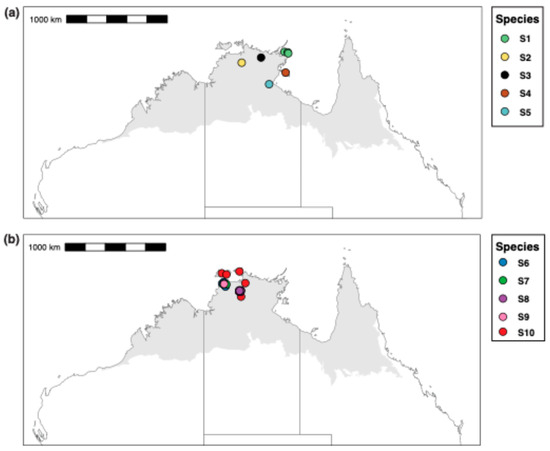

Our CO1 tree shows four major clades within the M. snellingi complex, the first containing spp. S1–3, the second spp. S4 and S5, the third sp. S6 and the fourth sp. S7–10 (Figure 3). Clypeal structure is not as variable as it is among species of the M. berrimah complex, but there is marked variation among species in the sculpture of the head, the shape and sculpture of the dorsal shield, and in the degree of divergence of the propodeal spines (Figure 6). All the species are known only from the Top End of the NT, and with one exception all have very restricted distributions (Figure 7): three are known only from the Darwin region (sp. S6, S7 and S9), two each from Kakadu National Park (sp. S2 and S8) and the NT Gulf region (spp. S4 and S5), and one each from northeastern (sp. S1) and central (sp. S3) Arnhem Land. The exception is sp. S10, which has been recorded from the Tiwi Islands to Kakadu National Park (Figure 7b); however, CO1 distance and structure suggest that it very possibly represents multiple species. Remarkably, both sp. S7 and sp. S9 (>4% CO1 distance from each other) occur on the grounds of the CSIRO Laboratory in Darwin, the type locality of M. snellingi.

Figure 6.

Species of the Meranoplus snellingi complex. (a) sp. S1 (BOLD ID: MTROP293-23); (b) sp. S2 (MTROP119-23); (c) sp. S3 (MTROP296-23); (d) sp. S4 (TEMEA020-19); (e) sp. S5 (TEMEA036-19); (f) sp. S6 (OZBOL1942-21); (g) sp. S7 (TEMEA022-19); (h) sp. S8 (TEMEA029-19); (i) sp. S9 (MTROP329-23); (j) sp. S10 (BOLOZ2009-24).

Figure 7.

Collection localities for sequenced specimens of the Meranplus snellingi complex. (a) spp. S1–5; (b) spp. S5–10.

PTP analysis recognized the same number of species (11) in the M. berrimah complex as our integrated analysis, and the constituent specimens were the same for seven of these (Figure 3). bPTP analysis recognized 14 species in the M. berrimah complex, six of which contained the same constituent specimens as our integrated species. PTP analysis recognized 14 species within the M. snellingi complex compared with our 10 from integrated analysis, with the difference largely due to the splitting of sp. S10 into four species (Figure 3). bPTP analysis recognized 15 species within the M. snellingi complex, splitting sp. S10 into three species (Figure 3).

4. Discussion

We have shown that both M. berrimah and M. snellingi represent large species complexes, and that M. ‘berrimah’ has a far broader geographic range than was apparent when it was originally described, occurring in the Kimberley region of WA in addition to the Top End of the NT, and also considerably further south in the NT. We recognize 11 species among our sequenced specimens from the M. berrimah complex, four of them occurring in the Kimberley region. We cannot be sure which if any of our recognized species is M. berrimah sensu stricto given that none were collected from the type locality in suburban Darwin or elsewhere in the broader Darwin area. The most likely candidate is sp. B1, which was collected from Berry Springs approximately 50 km south of Darwin, and, as in the type specimen (Figure 1a), it lacks a projecting clypeal plate (Figure 4a). Most of the species in the M. berrimah complex have very restricted known ranges. Given that just a small proportion of the Top End and Kimberley have been surveyed for ants, it is likely that many additional species remain to be collected, especially in the Kimberley. We estimate that the total number of species in the complex is at least 20 and possibly far higher.

We recognize ten species among our sequenced specimens from the M. snellingi complex, although one of these (sp. S10) is very possibly multiple species. Two of the species (spp. S7 and S9) were collected from the type locality of M. snellingi in suburban Darwin and a third (sp. S6) was collected just 2 km away. One of these is almost certainly M. snellingi ss, but it is not possible to determine which from available type images. As for the M. berrimah complex, the restricted distributions of species within the M. snellingi complex combined with limited sampling mean that additional species almost certainly occur. However, these are likely to be fewer than in the M. berrimah complex because the M. snellingi complex appears to occur only in the Top End. We estimate that the M. snellingi complex contains 15–20 species in total.

As we expected, the M. berrimah and M. snellingi complexes are far smaller in size than are the M. ajax and M. unicolor complexes (both estimated to be of the order of 100 species), as reflected in the differences in their distributional ranges. However, they provide further evidence of the remarkable diversity of undescribed species in monsoonal Australia, likely numbering several thousand [4]. Such undescribed diversity contradicts the widely accepted global pattern of ant diversity, which considers peak diversity to occur in tropical rainforest and especially in the Amazon [12]. The Amazonian ant fauna is estimated to comprise approximately 2000 species [13], whereas the available evidence indicates that at least twice this many occur in the tropical savanna landscapes of monsoonal Australia [4].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d18010005/s1, Supplementary Table S1: List of specimens of the Meranoplus berrimah and M. snellingi complexes sequenced in this study and their collection locations and years of collection. Specimens are identified by their BOLD ID codes and arranged according to species.

Author Contributions

A.N.A. conceived the study, led the development of the Darwin ant collection, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. F.B. prepared Figure 3, Figure 5 and Figure 7 and contributed to the writing of the paper. B.D.H. helped develop the Darwin ant collection and contributed to the writing of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The CO1 data presented in this study are available under their project names on BOLDSYSTEMS (https://v3.boldsystems.org; accessed on 4 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank our many collaborators who collected the specimens analyzed in this study, especially Magen Pettit, Tony Hertog and Jodie Hayward from CSIRO, as well as staff from the Flora and Fauna Division of the NT Department of Environment and Natural Resources who have included ant sampling at hundreds of sites in the NT as part of ongoing biodiversity assessment. We are most grateful to Tanvikumari Patel for preparing the ant images. We also thank Magen Pettit, Jodie Hayward, Ben Aidoo, Sarah Bonney and Prakash Gaudel for preparing samples for CO1 analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

Author B.D.H. was employed by the company Myrmex. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Schödl, S. Revision of Australian Meranoplus: The Meranoplus diversus group. In Advances in Ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Systematics: Homage to E. O. Wilson—50 Years of Contributions; Snelling, R.R., Fisher, B.L., Ward, P.S., Eds.; The American Entomological Institute: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2007; Volume 80, pp. 370–424. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A.N.; Brassard, F.; Hoffmann, B.D. Unrecognised ant megadiversity in the Australian monsoonal tropics III: The Meranoplus ajax Forel complex. Diversity 2024, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N.; Brassard, F.; Hoffmann, B.D. Unrecognised ant megadiversity in the Australian monsoonal tropics: The Meranoplus unicolor Forel complex. Entomol. Res. 2025, 55, e70074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.N.; Brassard, F.; Hoffmann, B.D. The ant fauna of Australian tropical savannas: Biogeography, diversity, functional composition and conservation. In The Fauna of Australia’s Tropical Savanna Biome: Biodiversity, Biogeography and Conservation; Andersen, A.N., Woinarski, J.C.Z., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, A.N. A systematic overview of Australian species of the myrmicine ant genus Meranoplus F. Smith, 1893 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecol. Nachrichten 2006, 8, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, T.K.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.J.; Susko, E.; Bielow, C.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Hahn, M.W.; et al. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic Inference Software Using Complex Evolutionary Models. 2025. Available online: https://ecoevorxiv.org/repository/view/8916/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Smith, M.A.; Fisher, B.L.; Hebert, P.D.N. DNA barcoding for effective biodiversity assessment of a hyperdiverse arthropod group: The ants of Madagascar. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 1825–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlick-Steiner, B.C.; Steiner, F.M.; Moder, K.; Seifert, B.; Sanetra, M.; Dyreson, E.; Stauffer, C.; Christian, E. A multidisciplinary approach reveals cryptic diversity in Western Palearctic Tetramorium ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2006, 40, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Kapli, P.; Pavlidis, P.; Stamatakis, A. A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformztics 2013, 29, 2869–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kass, J.M.; Guénard, B.; Dudley, K.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Azuma, F.; Fisher, B.L.; Parr, C.L.; Gibb, H.; Longino, J.Y.; Ward, P.S.; et al. The global distribution of known and undiscovered ant biodiversity. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabp9908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feitosa, R.M.; Camacho, G.P.; Silva, T.S.R.; Ulysséa, M.A.; Ladino, N.; Oliveira, A.M.; Albuquerque, E.Z.; Schmidt, F.A.; Ribas, C.R.; Nogueira, A.; et al. Ants of Brazil: An overview based on 50 years of diversity studies. Syst. Biodivers. 2020, 20, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.